Celiacs and anxiety

Psychological Impacts of Celiac Disease

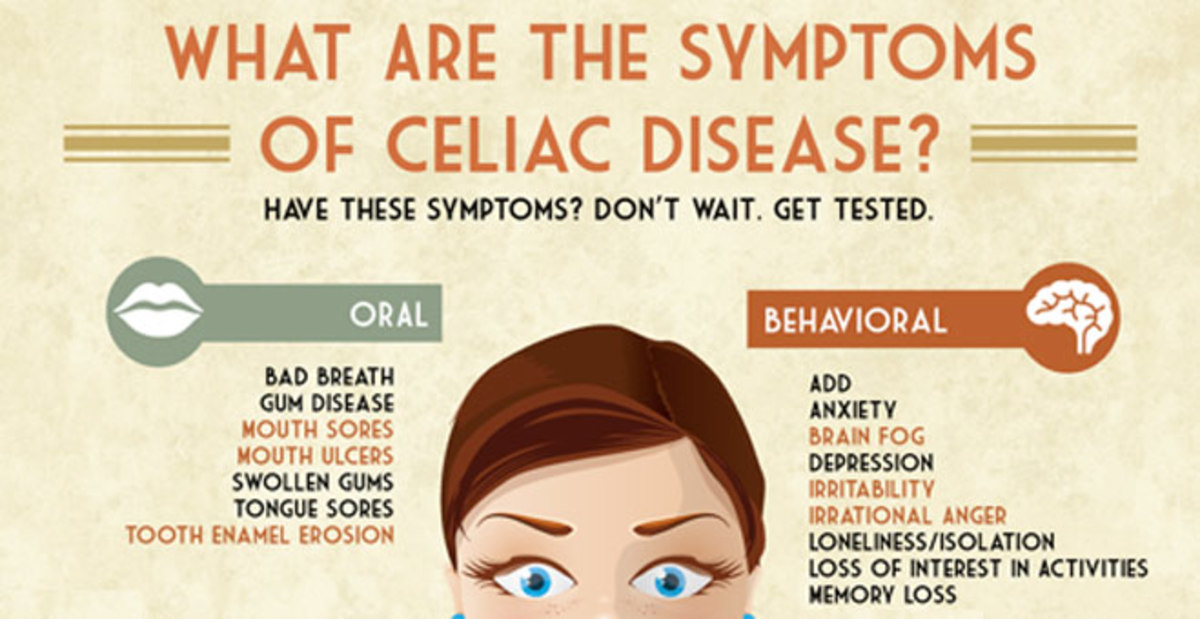

How can a problem in the gut impact psychological functioning? What is the gut-brain connection and which areas of psychological functioning are most affected by celiac disease?

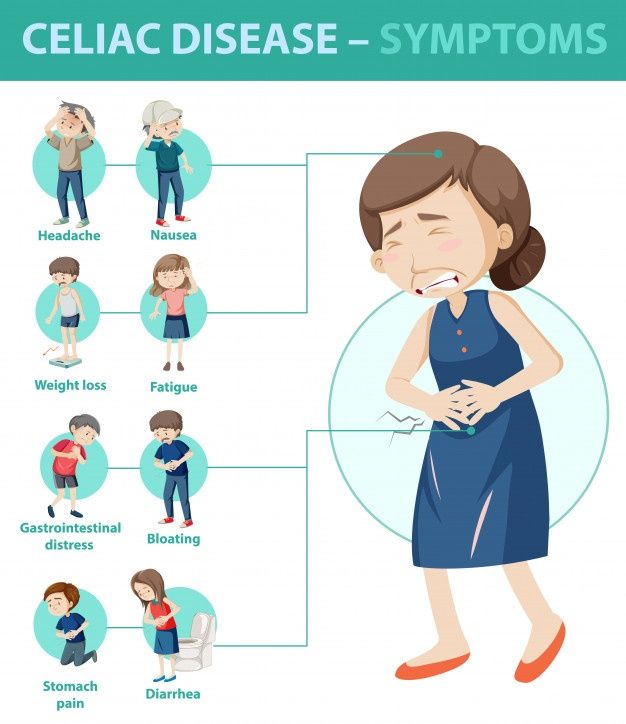

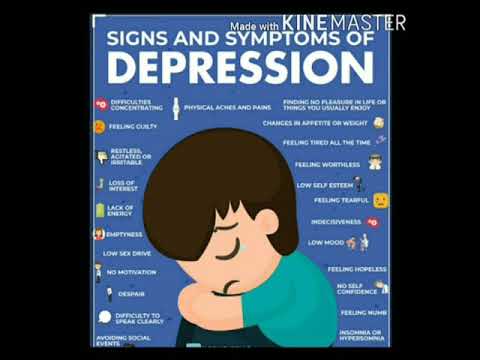

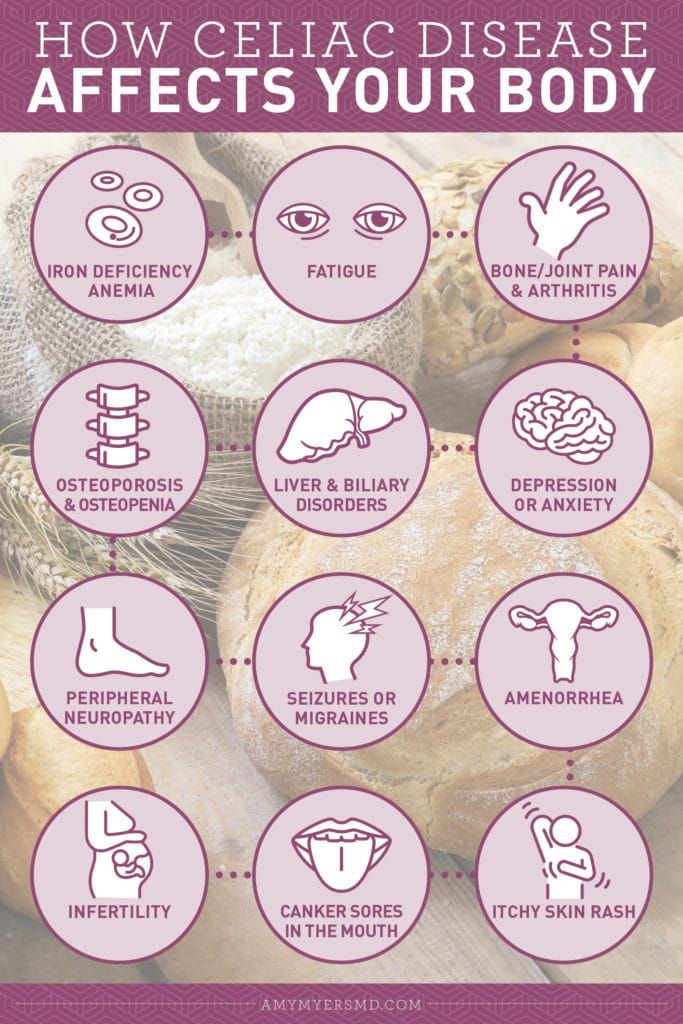

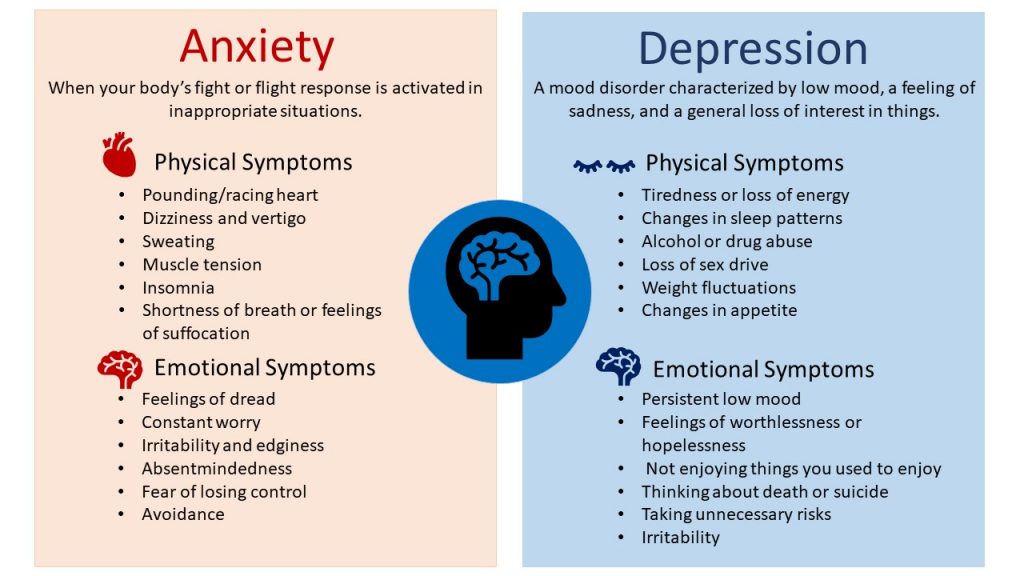

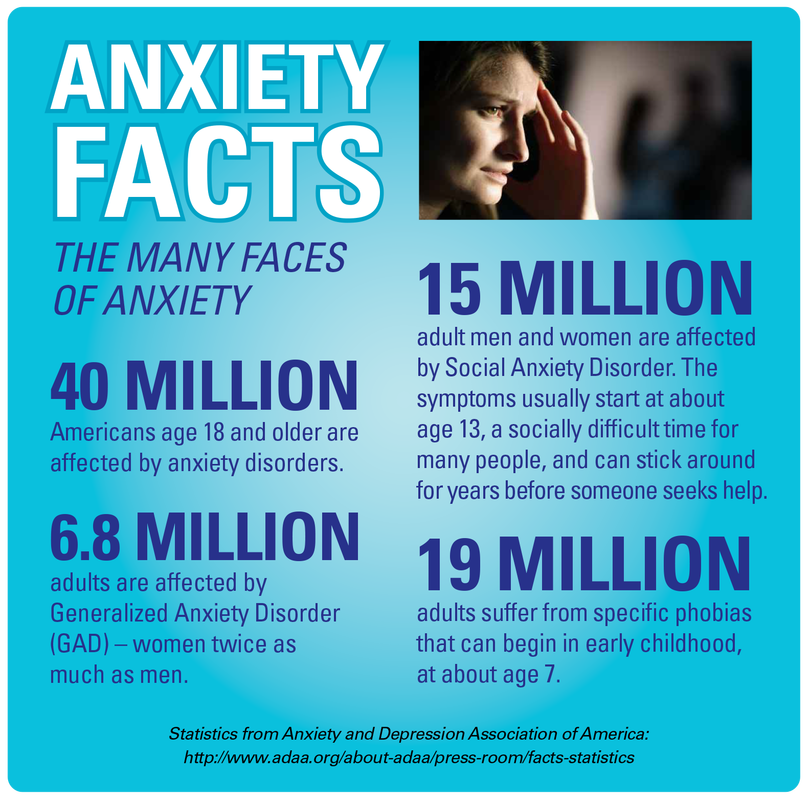

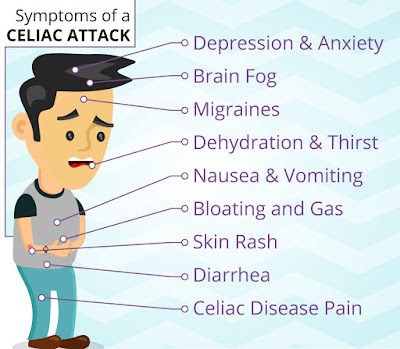

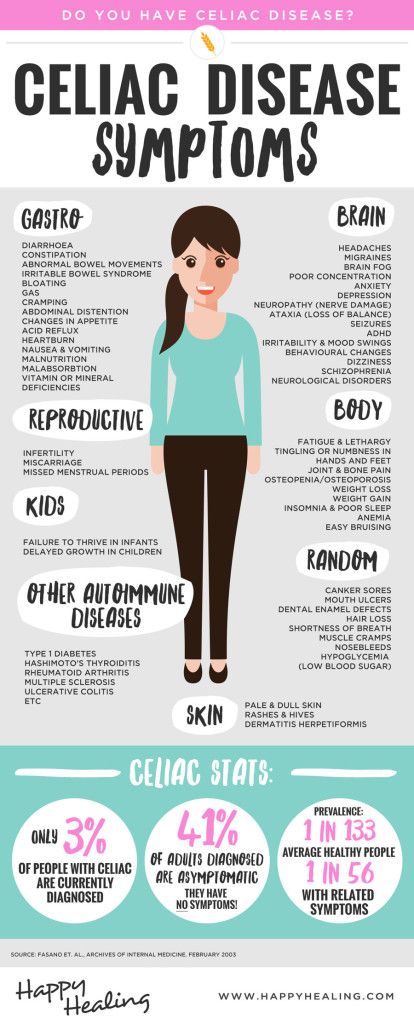

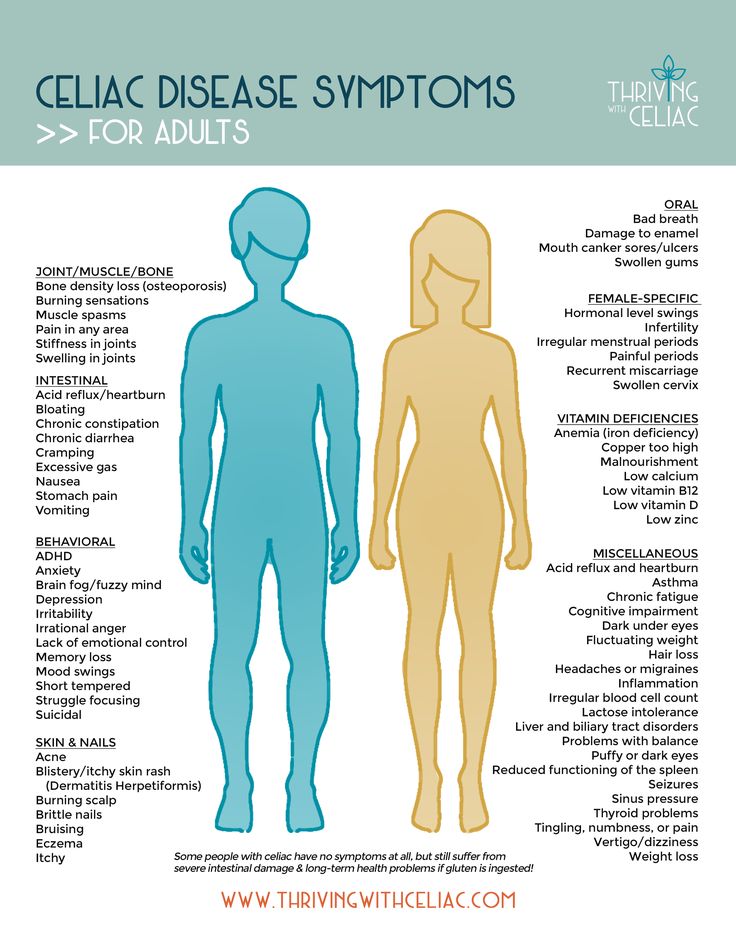

Research shows that untreated celiac disease can impact emotions, cognitive ability, behaviors, and more. Anxiety, depression and fatigue are common issues reported in celiac disease patients prior to diagnosis. Side effects of celiac disease can affect the brain in various ways, leading to a lower quality of life for those suffering from untreated celiac disease, and sometimes even after diagnosis, too.

Psychological Issues Associated with Celiac Disease

- Depression

- Moodiness, overwhelmed, non-restful sleep

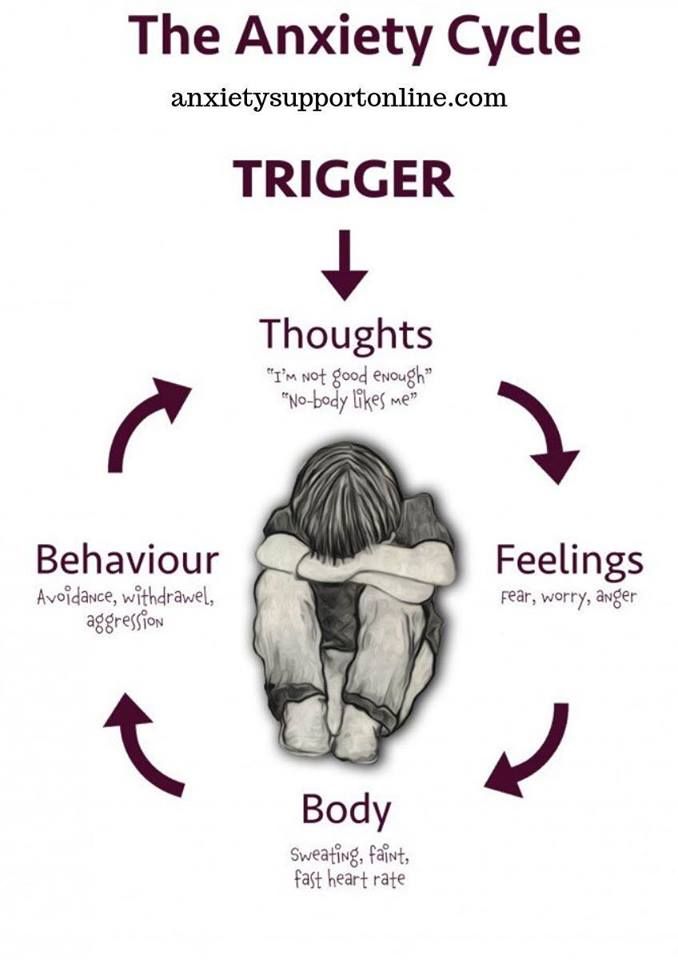

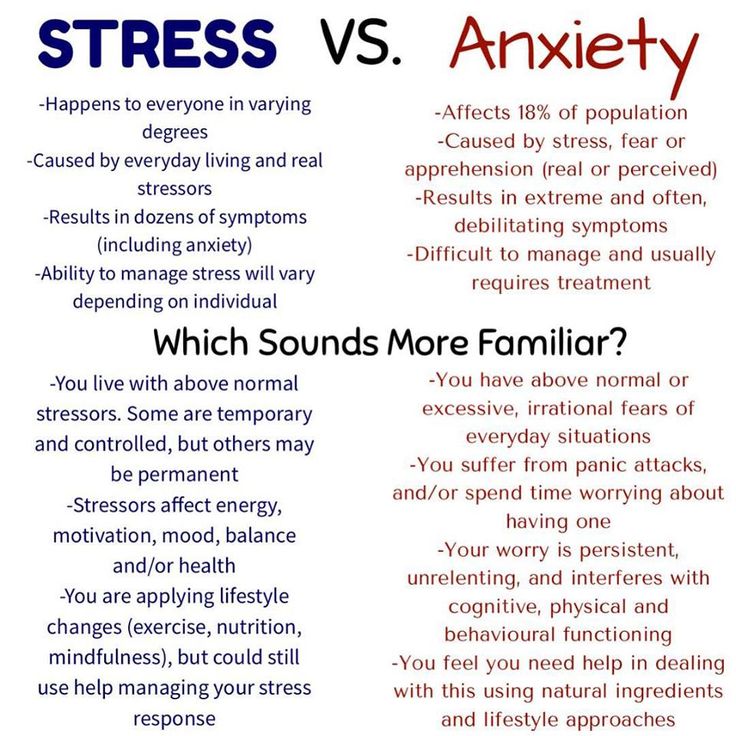

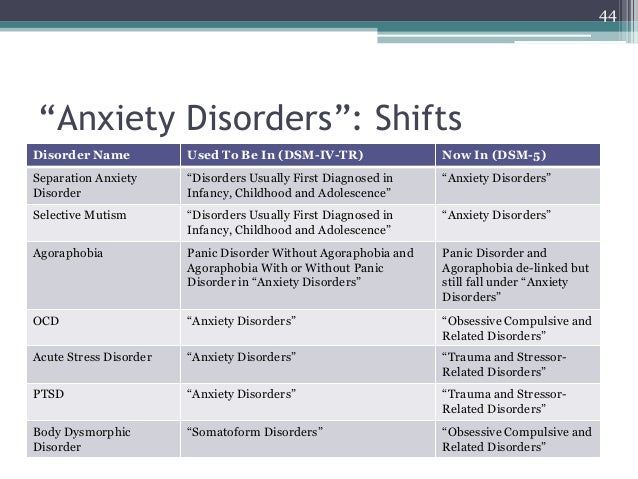

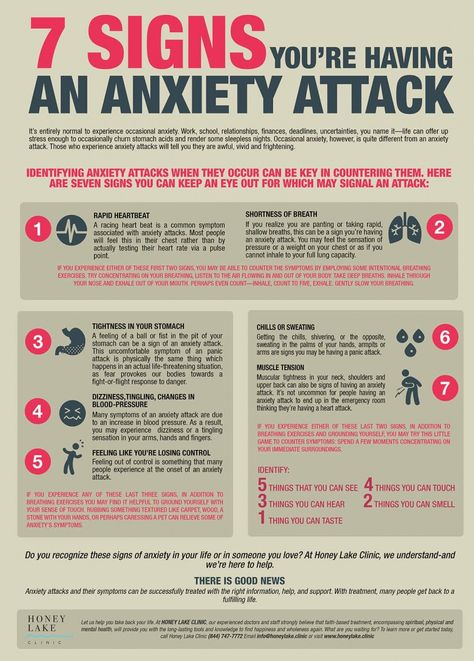

- Anxiety

- Phobias, separation anxiety, obsessive-compulsive tendencies, panic attacks

- Irritability

- Impatient and grumpiness in adults, outbursts of anger or temper tantrums in children

- ADHD

- Eating disorders

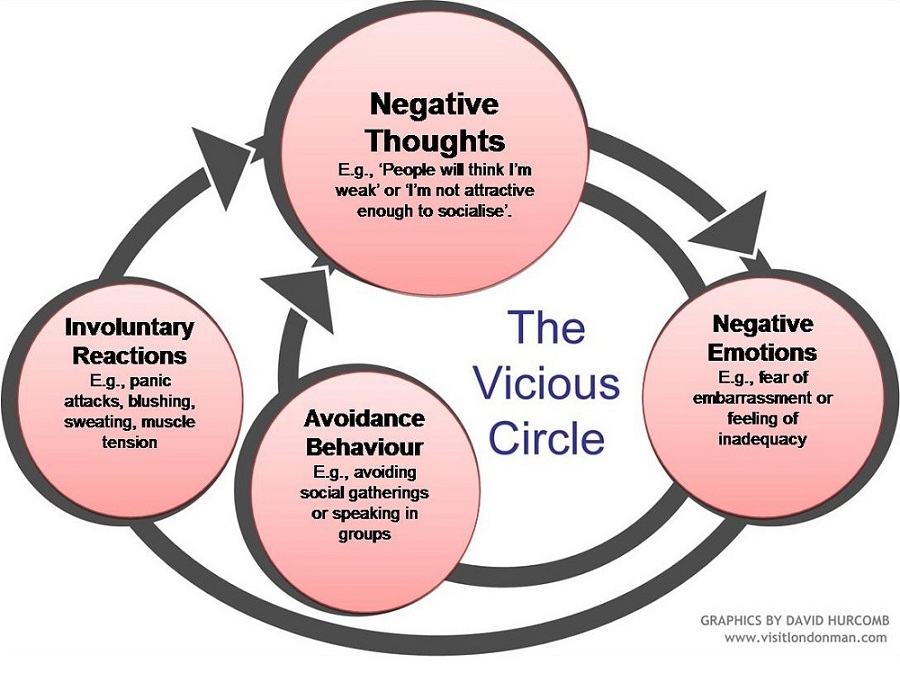

- Social anxiety

- Withdrawn, uncomfortable, and afraid of people

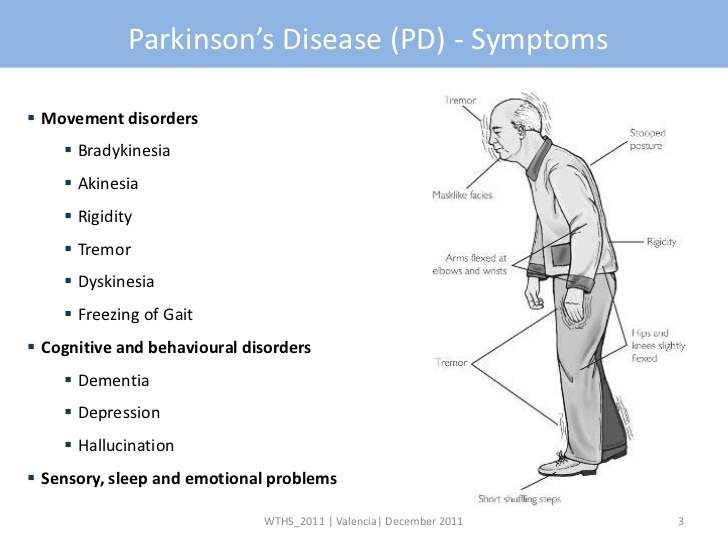

Neurological and Cognitive Issues Associated with Celiac Disease

- Brain fog

- Ataxia

- Memory lapse

- Headaches

- Migraines

- Difficulty paying attention

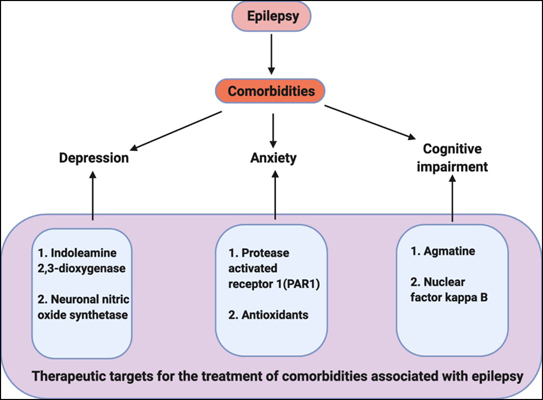

Latest Research on Celiac Disease and Brain Disorders and Mental Health

- 7/27/2021: Beyond Celiac Partners with University of Sheffield to Research Neuropathology of Celiac Disease and Gluten-Related Disorders – Researchers continue to investigate the sometimes debilitating neuropsychological impairment in those with celiac disease and NCGS.

- 6/11/2021: Brain fog survey reveals details about the symptom – Brain fog is a symptom that gets a lot of attention in the celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity communities, but not as much attention from researchers.

- 6/2/2021: The burden of celiac disease includes ongoing symptoms, missed workdays and disordered eating – Young adults with celiac disease may have more anxiety, disordered eating attitudes and beliefs, and a lower quality of life, a study suggests.

- 3/22/2021 – Neurological and psychological symptoms of celiac disease exposed by Go Beyond Celiac – data from the Go Beyond Celiac Gluten Exposure Survey highlights a number of neurological and psychological symptoms that celiac disease patients report experiencing after exposure to gluten

- 6/11/2020: Children with celiac disease at greater risk of mental health disorders – About one-third of children with celiac disease have mental health disorders, primarily anxiety disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), according to a new study.

- 3/25/2020: Brain images show celiac disease-related damage – Brain injury, cognitive deficiency and mental health issues tied to gluten exposure, study finds.

Understanding the Link between Celiac Disease and Psychological Disorders

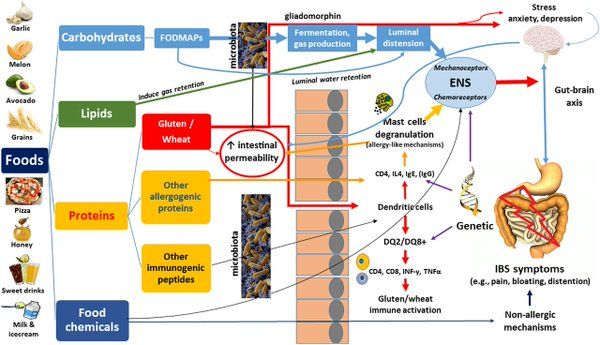

The gut and brain are intimately connected. Just thinking about food can cause the stomach to release fluids and prepare to eat. Some people make decisions based on a “gut feeling,” or experience “butterflies in their stomach” when they are excited or nervous. Others may experience diarrhea whenever they are particularly anxious (called “anxiety poops” or “stress poops” colloquially). These are all examples of how things that happen in the gut can affect the mind and vice versa. So it makes sense that when the gut is suffering because of celiac disease, the mind might suffer, too.

The exact reasons why those with celiac disease can experience negative psychological symptoms are varied, but include:

- Malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies

- Damaged villi, the distinguishing effect of celiac disease, make it difficult for the gut to assimilate nutrients essential for proper functioning of a number of organs.

- Notable nutritional deficiencies common in those with celiac disease include vitamin B (B6, B12, and Folate), iron, vitamin D, vitamin K, and calcium.

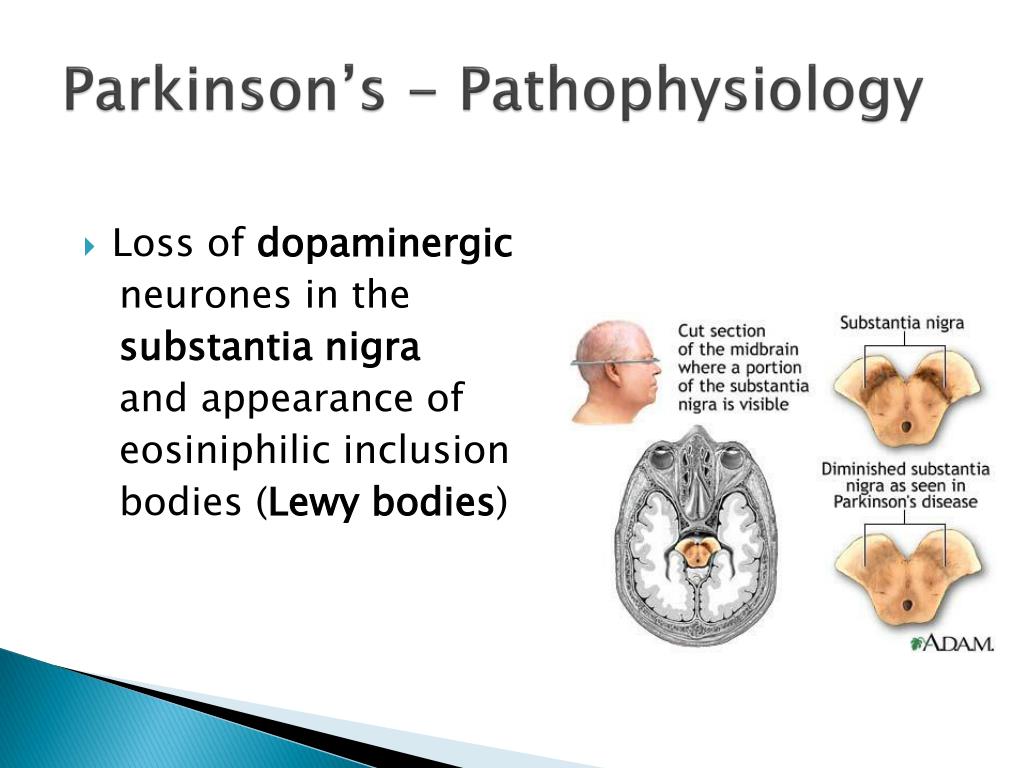

- The malnourished body may be unable to produce enough tryptophan and other monoamine precursors needed for the production of key neurotransmitters in the brain, such as serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine.

- This biochemical imbalance in the brain is associated with emotional problems.

- Damaged villi, the distinguishing effect of celiac disease, make it difficult for the gut to assimilate nutrients essential for proper functioning of a number of organs.

- Toxins

- Celiac disease is also associated with “leaky gut” syndrome.

- Poorly digested food overtax filtering organs such as the liver, leading to buildup.

- Some toxins affect opioid receptors of the brain.

- Immune response

- Inflammation is the body’s natural response to assault.

- In the case of autoimmune illnesses, such as celiac disease, the body produces antibodies against the body’s own tissue.

- This manifests with symptoms like swelling, abdominal, joint pain, headaches, and hypoperfusion (low blood flow) in the brain.

- The immune response may also cause the production of stress hormones.

- Byproducts of digestion end up in the bloodstream and affect different parts of the body.

- Secondary diseases

- After many years of this autoimmune reactions, organs can become chronically affected and develop primary diseases.

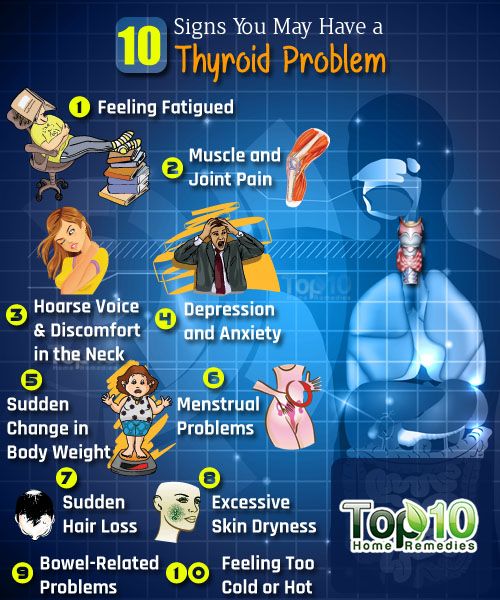

- A common example is thyroid disease: studies show that in people who have celiac disease and depression, up to 80% of them have a comorbid thyroid disease.

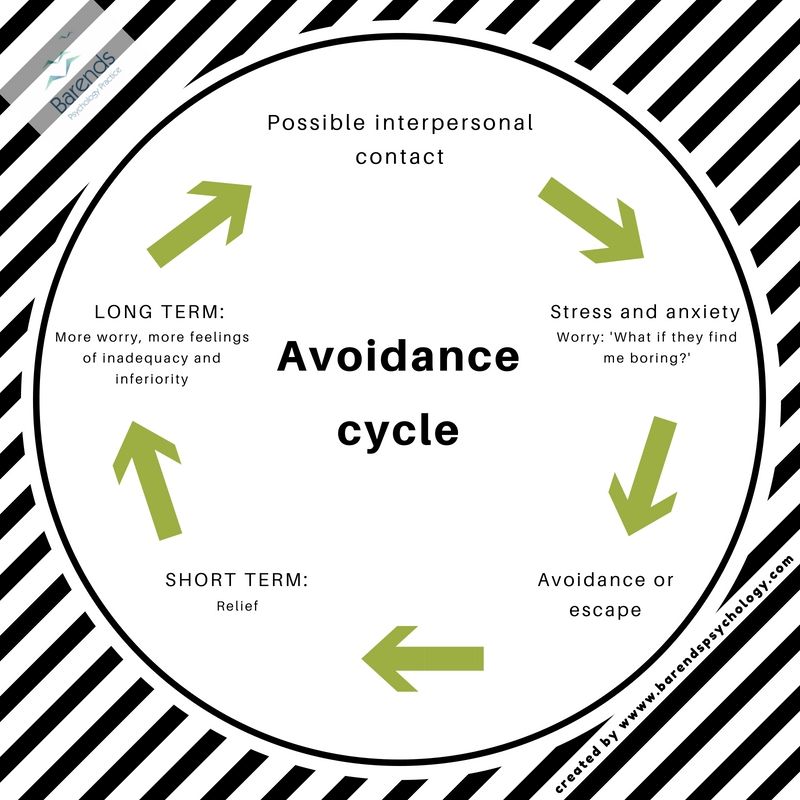

- Social Isolation

- Some people dread social events or frequently decline to go at all because of their symptoms, such as fatigue, migraines, joint pain, itchy rashes, or a constant need to go to the bathroom. This can create feelings of social isolation, depression, and anxiety.

Mental Health Recovery Post-Celiac Disease Diagnosis

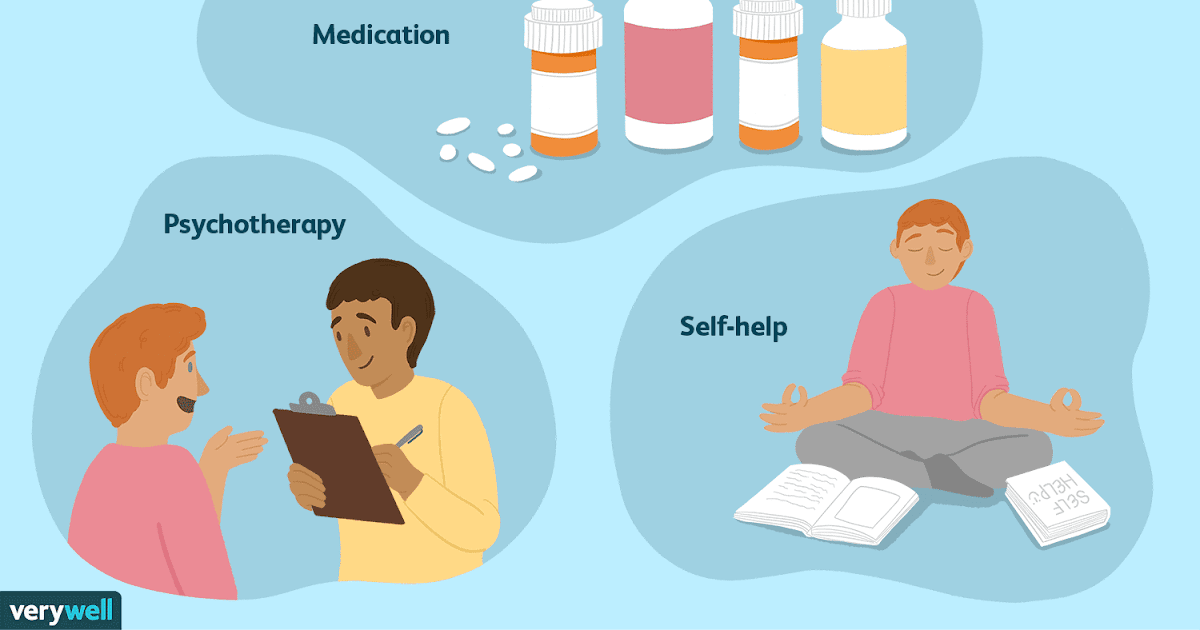

Some studies reveal complete remission of depression, anxiety and irritability with gluten-free diet, especially with younger populations. Other studies, especially on depression, are associated with mixed results.

Other studies, especially on depression, are associated with mixed results.

Here are a few things you can do after your diagnosis to help your brain recover:

- Stay gluten-free. No cheat days!

- Consider taking supplements until your gut heals.

- Exercise for about 30 minutes every day.

- Other organs may be damaged and require care, so talk to a doctor about getting additional tests to evaluate organ health and nutritional deficiencies.

- Try to become aware of your thinking habits and reframe overly negative or catastrophizing thoughts.

Let’s dive into that last bullet point. Did you know that the way we think creates neural connections in our brains? Humans develop habitual ways of thinking about situations and interpreting the world—they get used to using certain neural pathways. If you’re continually grumpy or sad for years, it becomes easier to feel grumpy or sad rather than happy. It make take effort to seek out and enjoy happiness.

It make take effort to seek out and enjoy happiness.

After many years of living in a bubble of discomfort, many forget to really live moments of well-being, satisfaction or joy. An official diagnosis can bring relief to many; however, others can feel emotionally secluded, socially isolated, or anxious and frustrated because of the gluten-free diet.

Some people reconnect with well-being through mindfulness exercises where they learn to “inhabit” happy and peaceful. Soaking up the good vibes, if you will. Meditation has also been found to increase cortical thickness.

Finally, studies show that connecting with others also enhances people’s ability to handle the gluten-free diet. Support groups and online forums can allow you to meet others who have experienced or are experiencing the same things, and counseling or therapy can provide personalized education around coping mechanisms for feelings of isolation and anxiety.

Possible Reasons for Continued Psychological Issues After Going Gluten-Free

Some possible reasons for continued celiac disease-related mental health problems after starting the gluten-free diet:

- Non-adherence to the gluten-free diet

- Unidentified food intolerances

- Thyroid problems

- Nutritional deficiencies

- Lengthy recovery period

- Difficulties accepting dietary change and its social implications

- Habitual ways of experiencing life

- Pre-existing conditions

It’s important to note that while many people see most of their ailments clear up after starting the gluten-free diet, there are also those that simply have a pre-existing psychological condition, not caused by or related to celiac disease. The gluten-free diet will not affect pre-existing conditions.

The gluten-free diet will not affect pre-existing conditions.

Treatments for pre-existing conditions include lifestyle changes and medications. If you take medication regularly, review the ingredients to ensure it is gluten-free. You should avoid medications with wheat starch when possible.

Infographic on the Psychosocial Impacts of Celiac Disease

(Click to enlarge image )

Neurologic and Psychiatric Manifestations of Celiac Disease and Gluten Sensitivity

1. Fasano A, Catassi C. Current approaches to diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease: An evolving spectrum. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:636–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Bizzaro N, Tozzoli R, Villalta D, Fabris M, Tonutti E. Cutting-edge issues in celiac disease and in gluten intolerance. Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s12016-010-8223-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Hadjivassiliou M, Grunewald RA, Davies-Jones GA. Gluten sensitivity as a neurological illness. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2002;72:560–563. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2002;72:560–563. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Hadjivassiliou M, Williamson CA, Woodroofe N. The immunology of gluten sensitivity: Beyond the gut. Trends in Immunology. 2004;25:578–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Sapone A, Lammers KM, Mazzarella G, Mikhailenko I, Carteni M, Casolaro V, et al. Differential mucosal IL-17 expression in two gliadin-induced disorders: Gluten sensitivity and the autoimmune enteropathy celiac disease. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 2010;152:75–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Kaukinen K, Turjanmaa K, Maki M, Partanen J, Venalainen R, Reunala T, et al. Intolerance to cereals is not specific for coeliac disease. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2000;35:942–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Bender L. Childhood schizophrenia. Psychiatric Quarterly. 1953;27:663–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Dohan FC. Wheat “consumption” and hospital admissions for schizophrenia during World War II. A preliminary report. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1966;18:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

A preliminary report. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1966;18:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Briani C, Zara G, Alaedini A, Grassivaro F, Ruggero S, Toffanin E, et al. Neurological complications of celiac disease and autoimmune mechanisms: A prospective study. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2008;195:171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Hadjivassiliou M, Grunewald RA, Chattopadhyay AK, Davies-Jones GA, Gibson A, Jarratt JA, et al. Clinical, radiological, neurophysiological, and neuropathological characteristics of gluten ataxia. Lancet. 1998;352:1582–1585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Hadjivassiliou M, Grunewald R, Sharrack B, Sanders D, Lobo A, Williamson C, et al. Gluten ataxia in perspective: Epidemiology, genetic susceptibility and clinical characteristics. Brain. 2003;126:685–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Bhatia KP, Brown P, Gregory R, Lennox GG, Manji H, Thompson PD, et al. Progressive myoclonic ataxia associated with coeliac disease. The myoclonus is of cortical origin, but the pathology is in the cerebellum. Brain. 1995;118 (Pt 5):1087–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brain. 1995;118 (Pt 5):1087–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Hadjivassiliou M, Boscolo S, Davies-Jones GA, Grunewald RA, Not T, Sanders DS, et al. The humoral response in the pathogenesis of gluten ataxia. Neurology. 2002;58:1221–1226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Hadjivassiliou M, Kandler RH, Chattopadhyay AK, Davies-Jones AG, Jarratt JA, Sanders DS, et al. Dietary treatment of gluten neuropathy. Muscle and Nerve. 2006;34:762–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Pellecchia MT, Scala R, Filla A, De Michele G, Ciacci C, Barone P. Idiopathic cerebellar ataxia associated with celiac disease: Lack of distinctive neurological features. Journal of Neurology, Neu-rosurgery and Psychiatry. 1999;66:32–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Chin RL, Sander HW, Brannagan TH, Green PH, Hays AP, Alaedini A, et al. Celiac neuropathy. Neurology. 2003;60:1581–1585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Chin RL, Latov N, Green PH, Brannagan TH, 3rd, Alaedini A, Sander HW. Neurologic complications of celiac disease. Journal of Clinical Neuromuscular Disease. 2004;5:129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Neurologic complications of celiac disease. Journal of Clinical Neuromuscular Disease. 2004;5:129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Morris JS, Ajdukiewicz AB, Read AE. Neurological disorders and adult coeliac disease. Gut. 1970;11:549–554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Pfaender M, D’Souza WJ, Trost N, Litewka L, Paine M, Cook M. Visual disturbances representing occipital lobe epilepsy in patients with cerebral calcifications and coeliac disease: A case series. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2004;75:1623–1625. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Arroyo HA, De Rosa S, Ruggieri V, de Davila MT, Fejerman N. Epilepsy, occipital calcifications, and oligosymptomatic celiac disease in childhood. Journal of Child Neurology. 2002;17:800–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Hernandez MA, Colina G, Ortigosa L. Epilepsy, cerebral calcifications and clinical or subclinical coeliac disease. Course and follow up with gluten-free diet. Seizure. 1998;7:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Seizure. 1998;7:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Canales P, Mery VP, Larrondo FJ, Bravo FL, Godoy J. Epilepsy and celiac disease: Favorable outcome with a gluten-free diet in a patient refractory to antiepileptic drugs. Neurologist. 2006;12:318–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Cernibori A, Gobbi G. Partial seizures, cerebral calcifications and celiac disease. Italian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 1995;16:187–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Fois A, Vascotto M, Di Bartolo RM, Di Marco V. Celiac disease and epilepsy in pediatric patients. Child’s Nervous System. 1994;10:450–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Peltola M, Kaukinen K, Dastidar P, Haimila K, Partanen J, Haapala AM, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis in refractory temporal lobe epilepsy is associated with gluten sensitivity. Journal of Neurology, Neu-rosurgery and Psychiatry. 2009;80:626–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Hadjivassiliou M, Rao DG, Wharton SB, Sanders DS, Grunewald RA, Davies-Jones AG. Sensory ganglionopathy due to gluten sensitivity. Neurology. 2010;75:1003–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sensory ganglionopathy due to gluten sensitivity. Neurology. 2010;75:1003–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Hadjivassiliou M, Chattopadhyay AK, Grunewald RA, Jarratt JA, Kandler RH, Rao DG, et al. Myopathy associated with gluten sensitivity. Muscle and Nerve. 2007;35:443–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Gabrielli M, Cremonini F, Fiore G, Addolorato G, Padalino C, Candelli M, et al. Association between migraine and Celiac disease: Results from a preliminary case-control and therapeutic study. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2003;98:625–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Poloni N, Vender S, Bolla E, Bortolaso P, Costantini C, Callegari C. Gluten encephalopathy with psychiatric onset: Case report. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2009;5:16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Kieslich M, Errazuriz G, Posselt HG, Moeller-Hartmann W, Zanella F, Boehles H. Brain white-matter lesions in celiac disease: A prospective study of 75 diet-treated patients. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pediatrics. 2001;108:E21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Addolorato G, Capristo E, Ghittoni G, Valeri C, Masciana R, Ancona C, et al. Anxiety but not depression decreases in coeliac patients after one-year gluten-free diet: A longitudinal study. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2001;36:502–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Cicarelli G, Della Rocca G, Amboni M, Ciacci C, Mazzacca G, Filla A, et al. Clinical and neurological abnormalities in adult celiac disease. Neurological Sciences. 2003;24:311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Carta MG, Hardoy MC, Boi MF, Mariotti S, Carpiniello B, Usai P. Association between panic disorder, major depressive disorder and celiac disease: A possible role of thyroid autoimmunity. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:789–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Niederhofer H, Pittschieler K. A preliminary investigation of ADHD symptoms in persons with celiac disease. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2006;10:200–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Genuis SJ, Bouchard TP. Celiac disease presenting as autism. Journal of Child Neurology. 2010;25:114–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Genuis SJ, Bouchard TP. Celiac disease presenting as autism. Journal of Child Neurology. 2010;25:114–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. De Santis A, Addolorato G, Romito A, Caputo S, Giordano A, Gambassi G, et al. Schizophrenic symptoms and SPECT abnormalities in a coeliac patient: Regression after a gluten-free diet. Journal of Internal Medicine. 1997;242:421–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Samaroo D, Dickerson F, Kasarda DD, Green PH, Briani C, Yolken RH, et al. Novel immune response to gluten in individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;118:248–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Cascella NG, Kryszak D, Bhatti B, Gregory P, Kelly DL, Mc Evoy JP, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease and gluten sensitivity in the United States clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness study population. Schizophrenia Research. 2011;37:94–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Addolorato G, Mirijello A, D’Angelo C, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Vonghia L, et al. Social phobia in coeliac disease. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;43:410–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Social phobia in coeliac disease. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;43:410–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Hauser W, Janke KH, Klump B, Gregor M, Hinz A. Anxiety and depression in adult patients with celiac disease on a gluten-free diet. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;16:2780–2787. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Ludvigsson JF, Reutfors J, Osby U, Ekbom A, Montgomery SM. Coeliac disease and risk of mood disorders—a general population-based cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;99:117–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Ruuskanen A, Kaukinen K, Collin P, Huhtala H, Valve R, Maki M, et al. Positive serum antigliadin antibodies without celiac disease in the elderly population: Does it matter? Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;45:1197–1202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Corvaglia L, Catamo R, Pepe G, Lazzari R, Corvaglia E. Depression in adult untreated celiac subjects: Diagnosis by the pediatrician. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1999;94:839–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1999;94:839–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Atladottir HO, Pedersen MG, Thorsen P, Mortensen PB, Deleuran B, Eaton WW, et al. Association of family history of autoimmune diseases and autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2009;124:687–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Valicenti-McDermott MD, McVicar K, Cohen HJ, Wershil BK, Shinnar S. Gastrointestinal symptoms in children with an autism spectrum disorder and language regression. Pediatric Neurology. 2008;39:392–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. de Magistris L, Familiari V, Pascotto A, Sapone A, Frolli A, Iardino P, et al. Alterations of the intestinal barrier in patients with autism spectrum disorders and in their first-degree relatives. Journal of Pediatric and Gastroenterology Nutrition. 2010;51:418–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Knivsberg AM, Reichelt KL, Hoien T, Nodland M. A randomised, controlled study of dietary intervention in autistic syndromes. Nutritional Neuroscience. 2002;5:251–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2002;5:251–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Whiteley P, Haracopos D, Knivsberg AM, Reichelt KL, Parlar S, Jacobsen J, et al. The ScanBrit randomised, controlled, single-blind study of a gluten- and casein-free dietary intervention for children with autism spectrum disorders. Nutritional Neuroscience. 2010;13:87–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Hsu CL, Lin CY, Chen CL, Wang CM, Wong MK. The effects of a gluten and casein-free diet in children with autism: A case report. Chang Gung Medical Journal. 2009;32:459–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Vojdani A, O’Bryan T, Green JA, McCandless J, Woeller KN, Vojdani E, et al. Immune response to dietary proteins, gliadin and cerebellar peptides in children with autism. Nutritional Neuroscience. 2004;7:151–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Kalaydjian AE, Eaton W, Cascella N, Fasano A. The gluten connection: The association between schizophrenia and celiac disease. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;113:82–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Graff H, Handford A. Celiac syndrome in the case histories of five schizophrenics. Psychiatric Quarterly. 1961;35:306–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Graff H, Handford A. Celiac syndrome in the case histories of five schizophrenics. Psychiatric Quarterly. 1961;35:306–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Dohan FC, Grasberger JC, Lowell FM, Johnston HT, Jr, Arbegast AW. Relapsed schizophrenics: More rapid improvement on a milk- and cereal-free diet. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1969;115:595–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Dohan FC, Grasberger JC. Relapsed schizophrenics: Earlier discharge from the hospital after cereal-free, milk-free diet. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1973;130:685–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Singh MM, Kay SR. Wheat gluten as a pathogenic factor in schizophrenia. Science. 1976;191:401–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Dohan FC, Levitt DR, Kushnir LD. Abnormal behavior after intracerebral injection of polypeptides from wheat gliadin: Possible relevance to schizophrenia. Pavlovian Journal of Biological Science. 1978;13:73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Rice JR, Ham CH, Gore WE. Another look at gluten in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1978;135:1417–1418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Another look at gluten in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1978;135:1417–1418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Vlissides DN, Venulet A, Jenner FA. A double-blind gluten-free/gluten-load controlled trial in a secure ward population. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;148:447–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Potkin SG, Weinberger D, Kleinman J, Nasrallah H, Luchins D, Bigelow L, et al. Wheat gluten challenge in schizophrenic patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1981;138:1208–1211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Cascella NG, Kryszak D, Bhatti B, Gregory P, Kelly DL, Mc Evoy JP, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease and gluten sensitivity in the United States clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness study population. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2011;37:94–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Dickerson F, Stallings C, Origoni A, Vaughan C, Khushalani S, Leister F, et al. Markers of gluten sensitivity and celiac disease in recent-onset psychosis and multi-episode schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:100–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:100–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Jin SZ, Wu N, Xu Q, Zhang X, Ju GZ, Law MH, et al. A study of circulating gliadin antibodies in schizophrenia among a Chinese population. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

63. Reichelt KL, Landmark J. Specific IgA antibody increases in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 1995;37:410–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Boscolo S, Sarich A, Lorenzon A, Passoni M, Rui V, Stebel M, et al. Gluten ataxia: Passive transfer in a mouse model. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1107:319–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Sander HW, Magda P, Chin RL, Wu A, Brannagan TH, 3rd, Green PH, et al. Cerebellar ataxia and coeliac disease. Lancet. 2003;362:1548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Burk K, Melms A, Schulz JB, Dichgans J. Effectiveness of intravenous immunoglobin therapy in cerebellar ataxia associated with gluten sensitivity. Annals of Neurology. 2001;50:827–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Annals of Neurology. 2001;50:827–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Hadjivassiliou M, Aeschlimann P, Strigun A, Sanders DS, Woodroofe N, Aeschlimann D. Autoanti-bodies in gluten ataxia recognize a novel neuronal transglutaminase. Annals of Neurology. 2008;64:332–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Alaedini A, Okamoto H, Briani C, Wollenberg K, Shill HA, Bushara KO, et al. Immune cross-reactivity in celiac disease: Anti-gliadin antibodies bind to neuronal synapsin I. Journal of Immunology. 2007;178:6590–6595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Palova-Jelinkova L, Rozkova D, Pecharova B, Bartova J, Sediva A, Tlaskalova-Hogenova H, et al. Gliadin fragments induce phenotypic and functional maturation of human dendritic cells. Journal of Immunology. 2005;175:7038–7045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Thomas KE, Sapone A, Fasano A, Vogel SN. Gliadin stimulation of murine macrophage inflammatory gene expression and intestinal permeability are MyD88-dependent: Role of the innate immune response in Celiac disease. Journal of Immunology. 2006;176:2512–2521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Journal of Immunology. 2006;176:2512–2521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Ashkenazi A, Krasilowsky D, Levin S, Idar D, Kalian M, Or A, et al. Immunologic reaction of psychotic patients to fractions of gluten. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1979;136:1306–1309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Pavol MA, Meyers CA, Rexer JL, Valentine AD, Mattis PJ, Talpaz M. Pattern of neurobehavioral deficits associated with interferon alfa therapy for leukemia. Neurology. 1995;45:947–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Denicoff KD, Rubinow DR, Papa MZ, Simpson C, Seipp CA, Lotze MT, et al. The neuropsychiatric effects of treatment with interleukin-2 and lymphokine-activated killer cells. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1987;107:293–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Hadjivassiliou M. Glutamic acid decarboxylase as a target antigen in gluten sensitivity: The link to neurological manifestations? Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Celiac Disease. Belfast. 2004 [Google Scholar]

75. Williamson S, Faulkner-Jones BE, Cram DS, Furness JB, Harrison LC. Transcription and translation of two glutamate decarboxylase genes in the ileum of rat, mouse and guinea pig. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1995;55:18–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Williamson S, Faulkner-Jones BE, Cram DS, Furness JB, Harrison LC. Transcription and translation of two glutamate decarboxylase genes in the ileum of rat, mouse and guinea pig. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1995;55:18–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Volta U, De Giorgio R, Granito A, Stanghellini V, Barbara G, Avoni P, et al. Anti-ganglioside antibodies in coeliac disease with neurological disorders. Digestive and Liver Diseases. 2006;38:183–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Santoro M, Thomas FP, Fink ME, Lange DJ, Uncini A, Wadia NH, et al. IgM deposits at nodes of Ranvier in a patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, anti-GM1 antibodies, and multifocal motor conduction block. Annals of Neurology. 1990;28:373–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Molander M, Berthold CH, Persson H, Andersson K, Fredman P. Monosialoganglioside (GM1) immunofluorescence in rat spinal roots studied with a monoclonal antibody. Journal of Neurocytology. 1997;26:101–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Hadjivassiliou M, Maki M, Sanders DS, Williamson CA, Grunewald RA, Woodroofe NM, et al. Autoantibody targeting of brain and intestinal transglutaminase in gluten ataxia. Neurology. 2006;66:373–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hadjivassiliou M, Maki M, Sanders DS, Williamson CA, Grunewald RA, Woodroofe NM, et al. Autoantibody targeting of brain and intestinal transglutaminase in gluten ataxia. Neurology. 2006;66:373–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Pynnonen PA, Isometsa ET, Veradale MA, Chaconne SA, Sipila I, Savilahti E, et al. Gluten-free diet may alleviate depressive and behavioural symptoms in adolescents with coeliac disease: A prospective follow-up case-series study. BMC Psychiatry. 2005;5:14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Hallert C, Sedvall G. Improvement in central monoamine metabolism in adult coeliac patients starting a gluten-free diet. Psychological Medicine. 1983;13:267–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gluten and anxiety: what's the connection?

The term gluten refers to a group of proteins found in various grains, including wheat, rye and barley.

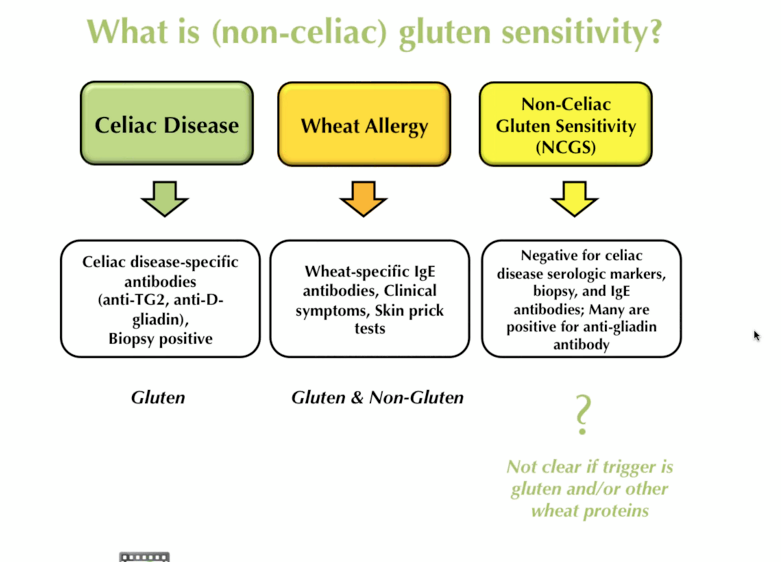

Although most people can tolerate gluten, it can cause a number of adverse side effects in people with celiac disease or gluten sensitivity.

Some report that gluten not only causes indigestion, headaches, and skin problems, but can also contribute to psychological symptoms such as anxiety. nine0003

This article takes a closer look at research to determine if gluten may be a concern.

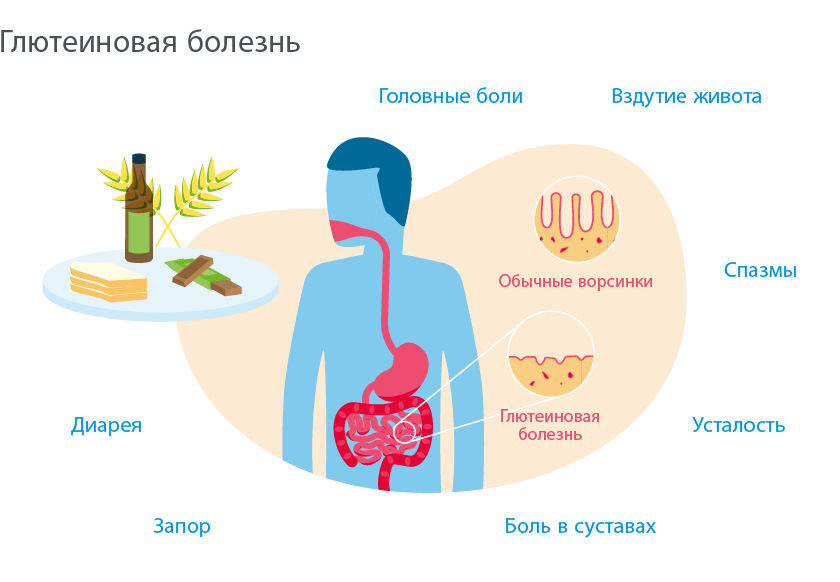

Celiac disease

In people with celiac disease, eating gluten causes inflammation in the intestines, causing symptoms such as bloating, gas, diarrhea, and fatigue.

Some research suggests that celiac disease may also be associated with an increased risk of certain psychiatric disorders, including anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. nine0003

A gluten-free diet can not only improve symptoms in people with celiac disease, but also reduce anxiety.

In fact, a 2001 study found that following a gluten-free diet for 1 year reduced anxiety in 35 people with celiac disease.

Another small study in 20 people with celiac disease found that participants had higher levels of anxiety before starting a gluten-free diet than after 1 year of it. nine0003

nine0003

However, conflicting results have been noted in other studies.

For example, one study found that women with celiac disease were more likely to experience anxiety compared to the general population, even after following a gluten-free diet.

Notably, homestay was also associated with an increased risk of anxiety disorders in the study, which may be related to the stress of shopping and food preparation for family members with and without celiac disease. nine0003

Moreover, a 2020 study of 283 people with celiac disease reported a high incidence of anxiety in people with celiac disease and found that following a gluten-free diet did not lead to a significant improvement in anxiety symptoms.

Thus, while a gluten-free diet may reduce anxiety in some people with celiac disease, it may not affect or even contribute to stress and anxiety in others. nine0003

More research is needed to evaluate the effect of a gluten-free diet on anxiety in people with celiac disease.

SUMMARY

Celiac disease is associated with an increased risk of anxiety disorders. While studies have shown inconclusive results, some research suggests that following a gluten-free diet may reduce anxiety in people with celiac disease.

Sensitized al gluten

People with gluten sensitivity without celiac disease may also experience adverse side effects from consuming gluten, including symptoms such as fatigue, headaches, and muscle pain. nine0003

In some cases, people with gluten sensitivity without celiac disease may also experience psychological symptoms such as depression or anxiety.

While more high-quality research is needed, some research suggests that removing gluten from the diet may be beneficial in these conditions.

In a study of 23 people, 13 percent of participants reported that following a gluten-free diet helped reduce subjective feelings of anxiety. nine0003

Another study in 22 people with gluten sensitivity without celiac disease found that eating gluten for 3 days resulted in increased feelings of depression compared to controls.

Although the cause of these symptoms remains unclear, some research suggests that the effect may be due to changes in the gut microbiome, a community of beneficial bacteria in the digestive tract that are involved in various aspects of health.

Unlike celiac disease or wheat allergy, there is no specific test to diagnose gluten sensitivity. nine0003

However, if you experience anxiety, depression, or any other negative symptoms after eating gluten, consult your doctor to determine if a gluten-free diet is right for you.

SUMMARY

Eating a gluten-free diet may reduce the subjective feelings of anxiety and depression in those who are sensitive to gluten.

Conclusion

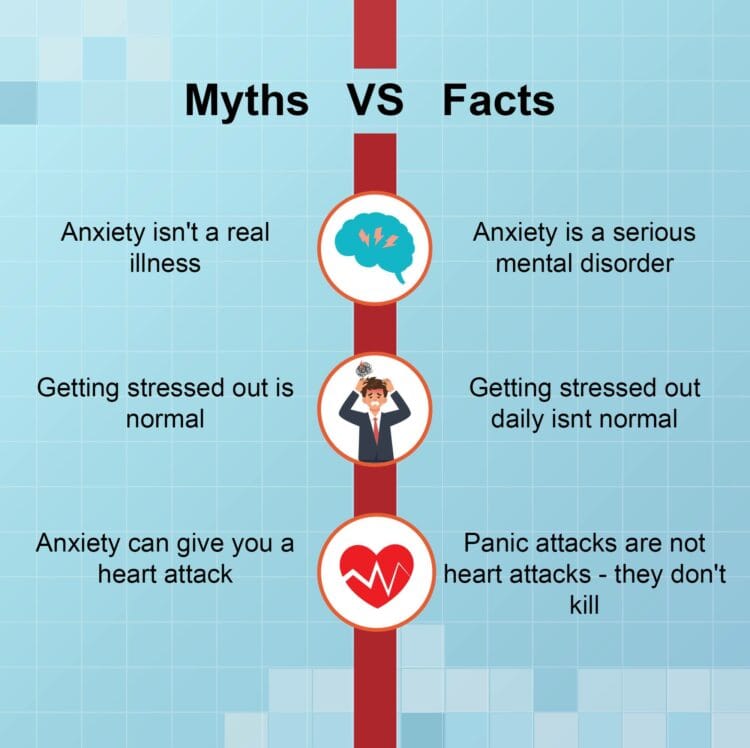

Anxiety is often associated with celiac disease and gluten sensitivity. nine0003

Although studies have shown mixed results, several studies suggest that following a gluten-free diet may help reduce anxiety symptoms in people with celiac disease or gluten sensitivity.

If you find that gluten is causing you anxiety or other adverse symptoms, consider consulting with your doctor to determine if a gluten-free diet might be helpful.

Li el Artículo en Inglés.

Gluten and anxiety: is there a link?

The term gluten refers to a group of proteins found in various grains, including wheat, rye and barley.

Although most people can tolerate gluten, it can cause a number of harmful side effects in people with celiac disease or gluten sensitivity.

Some say that gluten not only causes indigestion, headaches, and skin problems, but it can also contribute to psychological symptoms such as anxiety (1). nine0003

This article discusses research in more detail to determine if gluten may be a concern.

Share on Pinterest

content

Celiac disease

In patients with celiac disease, eating gluten causes inflammation in the intestines, causing symptoms such as bloating, gas, diarrhea, and fatigue. 2).

2).

Some research suggests that celiac disease may be associated with a higher risk of certain psychiatric disorders, including anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.3). nine0003

A gluten-free diet can not only relieve symptoms of celiac disease, but also reduce anxiety.

In fact, a 2001 study showed that after a gluten-free diet for 1 year, anxiety decreased in 35 people with celiac disease.4).

Another small study of 20 people with celiac disease reported that participants experienced higher levels of anxiety before starting a gluten-free diet than after following it for 1 year.5). nine0003

However, conflicting results have been noted in other studies.

For example, one study found that women with celiac disease were more likely to have anxiety compared to the general population, even after completing a gluten-free diet.6).

Notably, homestay was also associated with a higher risk of anxiety disorders in the study, which may be related to the stress of buying and preparing meals for family members with and without celiac disease. 6). nine0003

6). nine0003

Moreover, a 2020 study of 283 people with celiac disease reported a high frequency of anxiety in people with celiac disease and found that following a gluten-free diet did not lead to a significant improvement in anxiety symptoms.

So while a gluten-free diet may reduce anxiety in some people with celiac disease, it may not reduce anxiety or even contribute to stress and anxiety in others.

More research is needed to evaluate the effect of a gluten-free diet on anxiety in people with celiac disease.

Gluten Sensitivity

People with gluten sensitivity to gluten may also experience harmful side effects from eating gluten, including symptoms such as fatigue, headaches, and muscle pain.7).

In some cases, people who are not sensitive to celiac disease may also experience psychological symptoms such as depression or anxiety.7). nine0003

While more qualitative research is needed, some studies suggest that removing gluten from the diet may be beneficial in these conditions.

In one study of 23 people, 13% of participants reported that their subjective anxiety decreased after a gluten-free diet (8).

Another study in 22 people with gluten sensitivity without celiac disease showed that eating gluten for 3 days resulted in increased feelings of depression compared to controls.9).

Although the cause of these symptoms is still unclear, some research suggests that the effect may be due to changes in the gut microbiome, a community of beneficial bacteria in the digestive tract that are involved in several aspects of health.10,11).

Unlike celiac disease or wheat allergy, there is no specific test used to diagnose gluten sensitivity.

However, if you experience anxiety, depression, or any other negative symptoms after eating gluten, consult your doctor to determine if a gluten-free diet is right for you. nine0003

Essence

Anxiety is often associated with celiac disease and gluten sensitivity.

Although studies have shown mixed results, several studies show that monitoring a gluten-free diet can help reduce anxiety symptoms in people with celiac disease or gluten sensitivity.