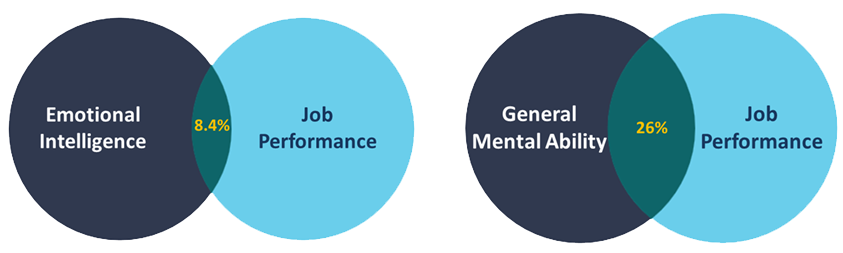

Research shows that having strong emotional intelligence enhances

Why emotional intelligence makes you more successful – Nest

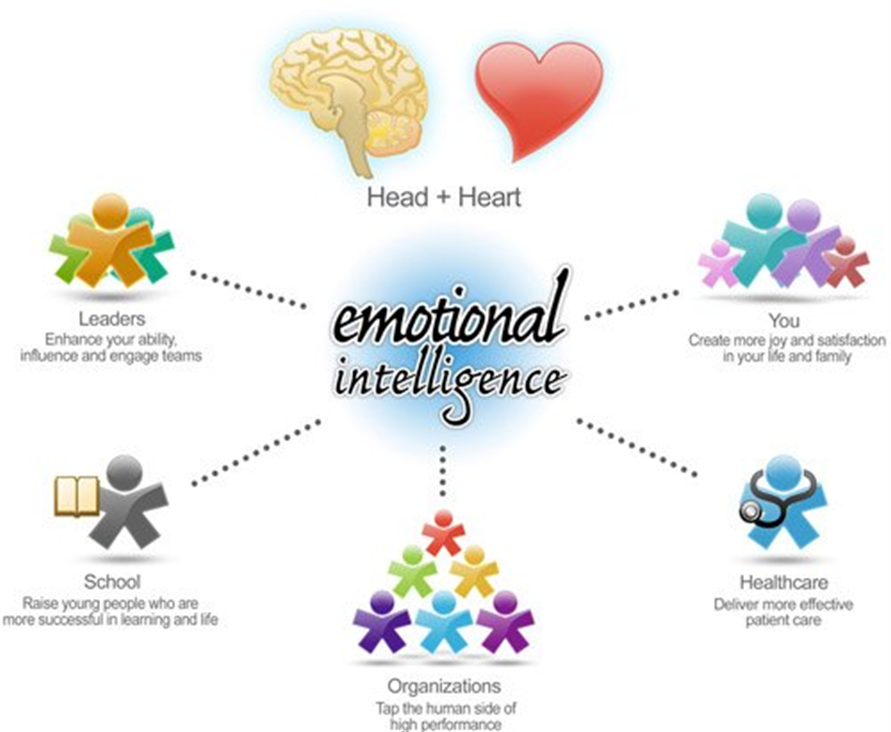

If you’ve recently read anything about getting ahead at work, you might have read that people with high emotional intelligence (EI) are more likely to get hired, promoted and earn better salaries. But what is EI and why is it so important?

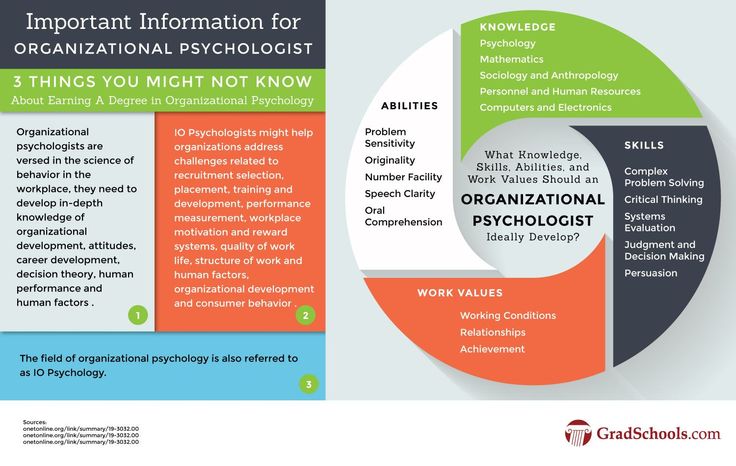

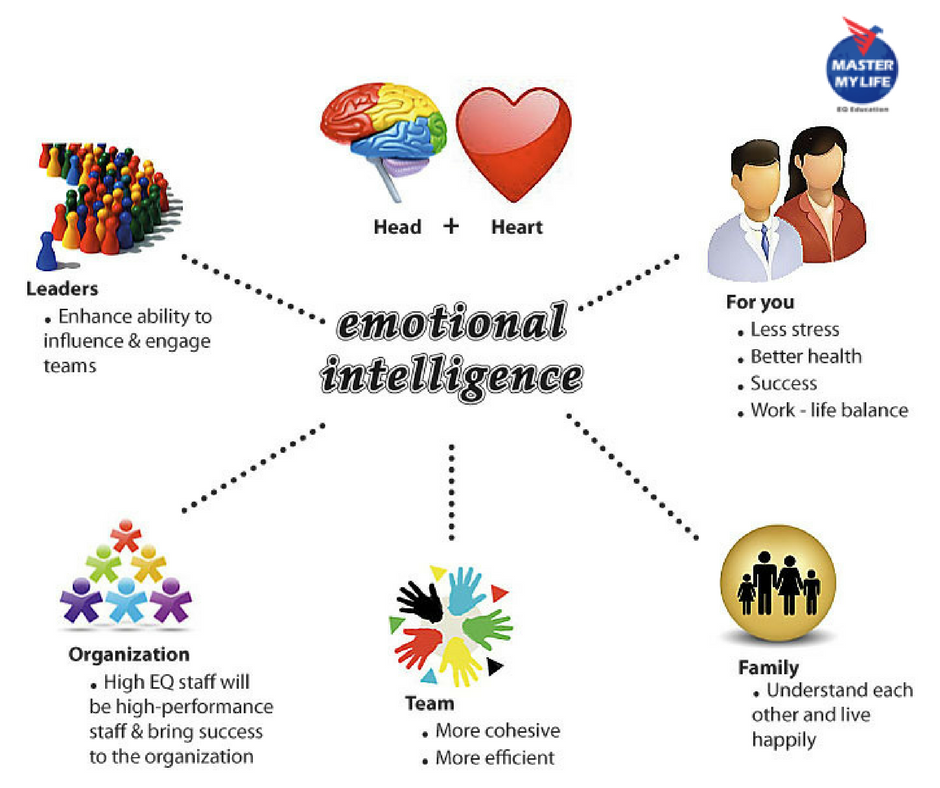

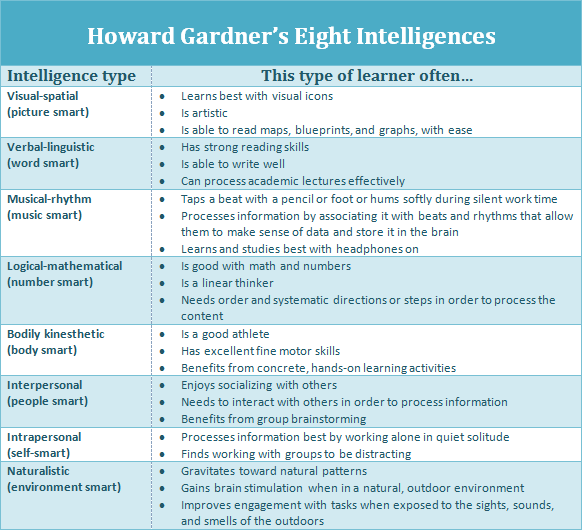

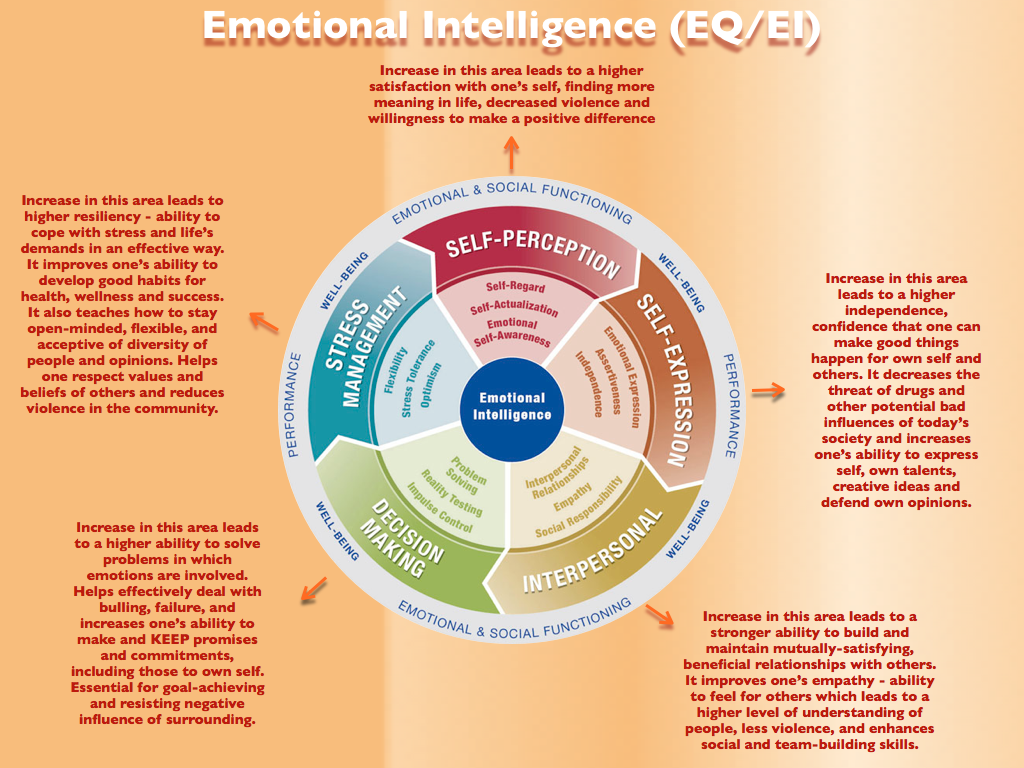

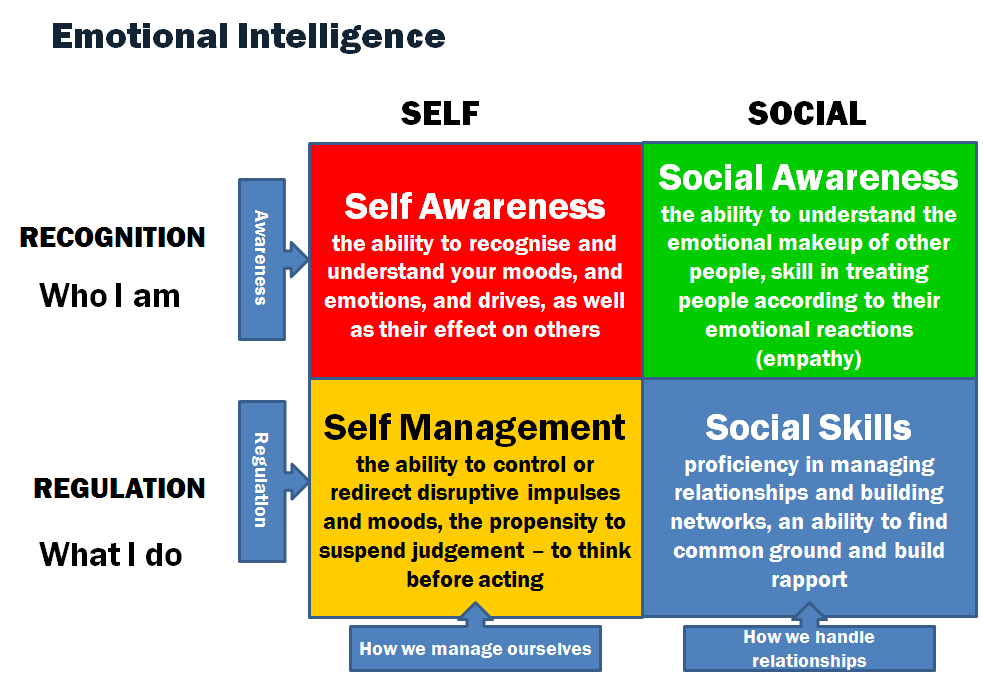

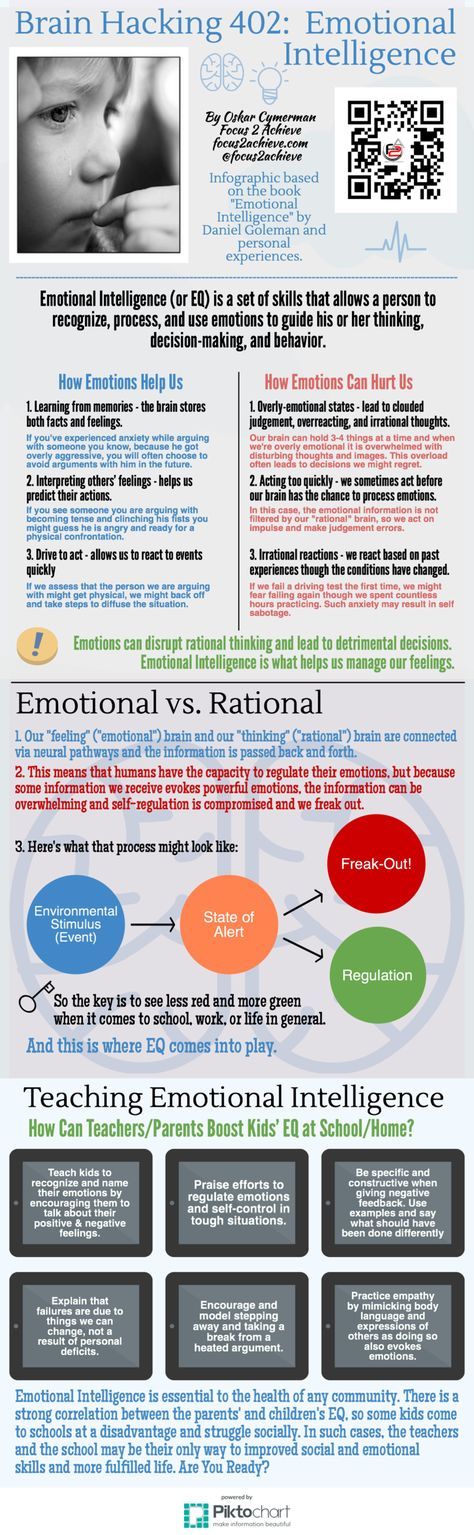

Emotional intelligence is the ability to identify and regulate one’s emotions and understand the emotions the others. A high EQ helps you to build relationships, reduce team stress, defuse conflict and improve job satisfaction. Ultimately, a high EI means having the potential to increase team productivity and staff retention. That’s why when it comes to recruiting management roles, employers look to hire and promote candidates with a high ‘EQ’ (emotional quotient) – rather than IQ (intelligence quotient).

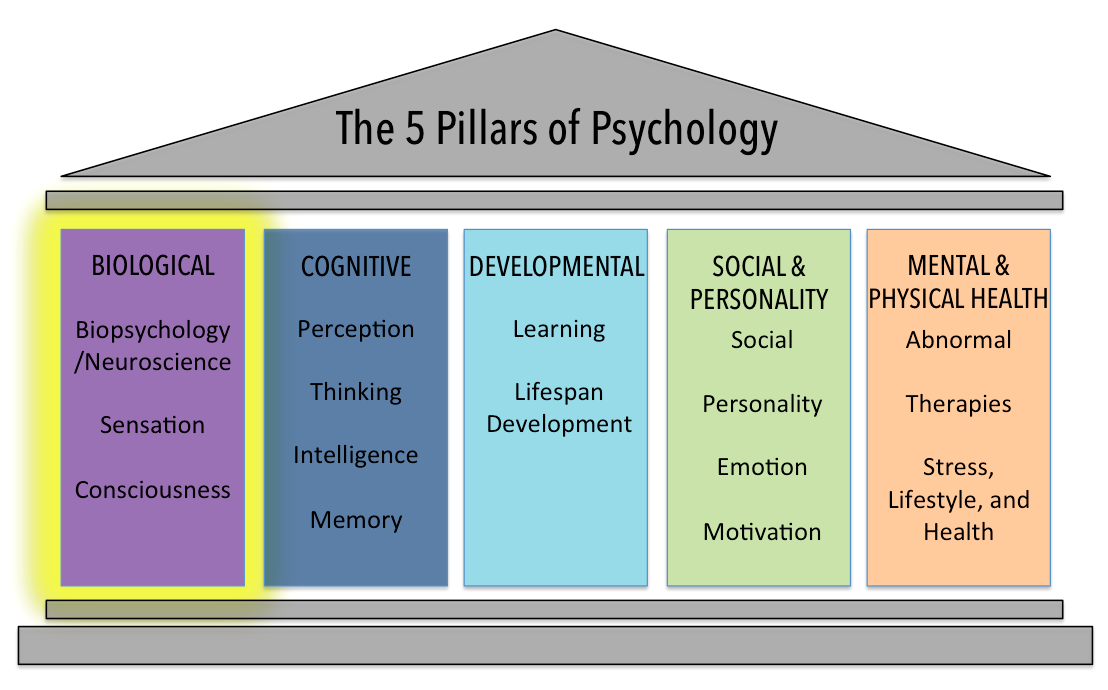

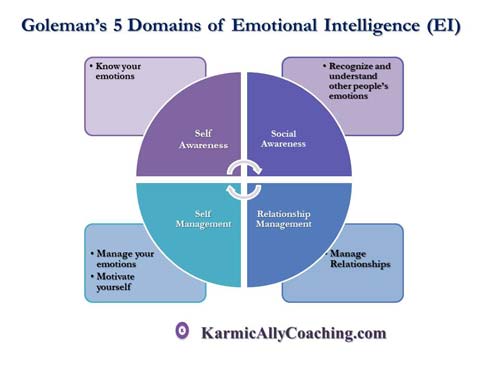

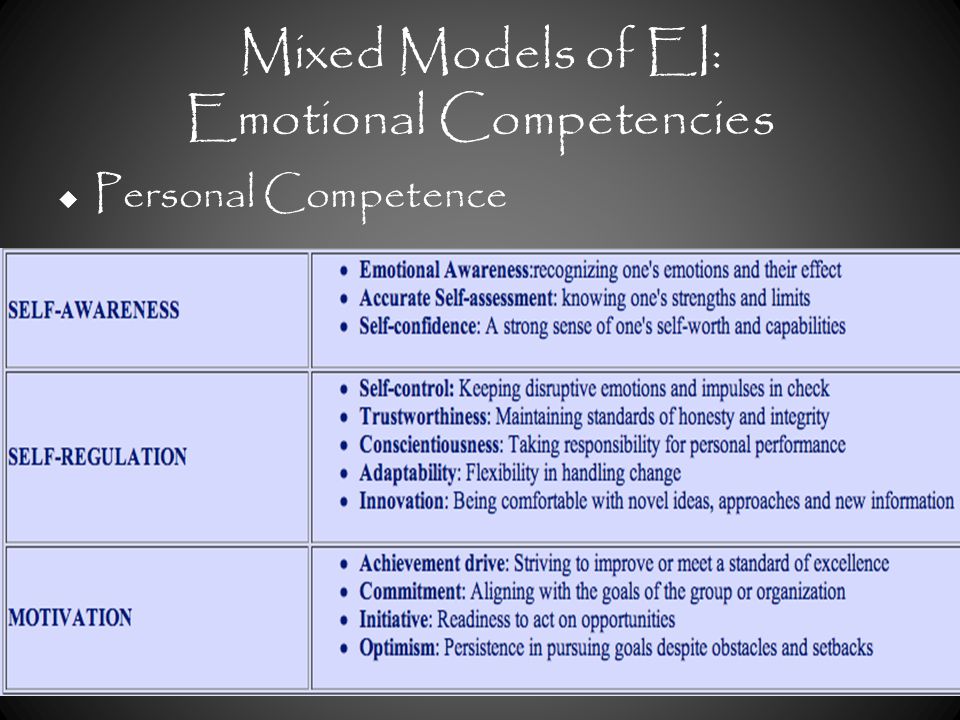

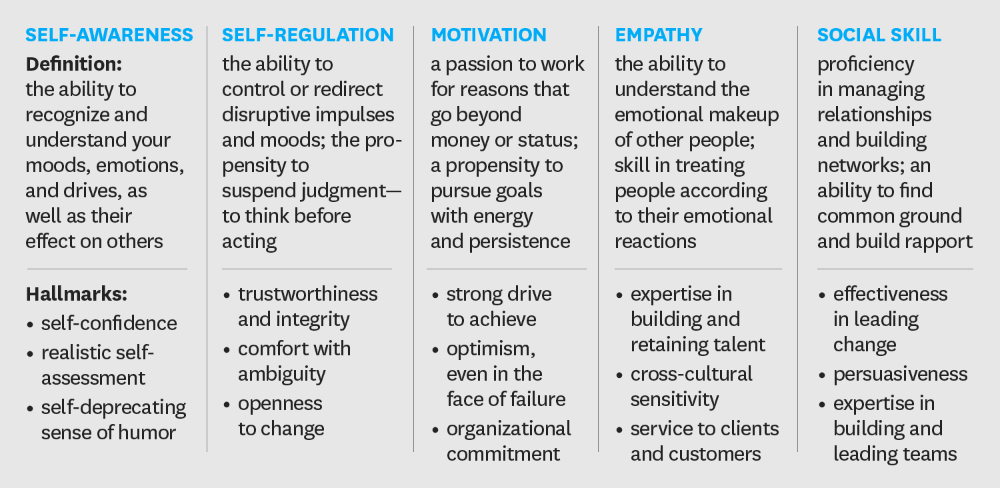

EI is important for everyone who wants to be career ready. Drawing on the work of Daniel Goleman, below are five pillars of emotional intelligence and how they give you an advantage in the workforce.

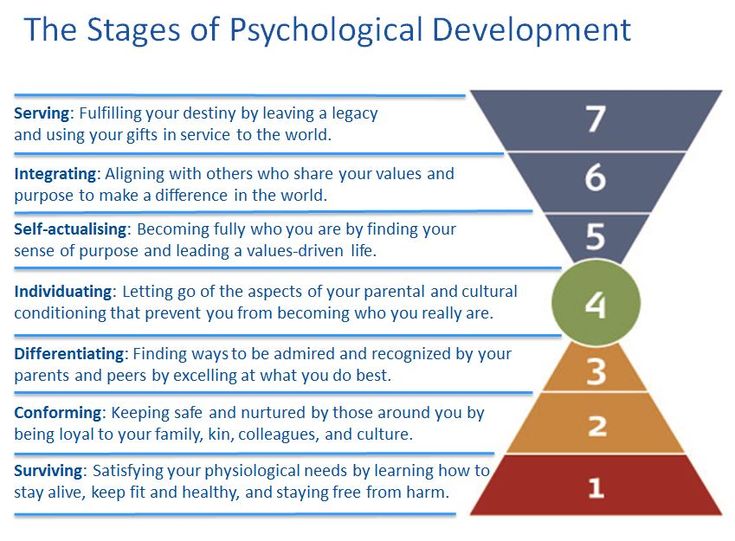

Self-awareness is the ability to recognise one’s emotions, emotional triggers, strengths, weaknesses, motivations, values and goals and understand how these affect one’s thoughts and behaviour.

If you’re feeling stressed, annoyed, uninspired or deflated in your role, for example, it’s important to take the time to check-in with yourself and investigate why you might be feeling this way. When you’re able to label the emotion and understand its cause, you’re in a much better place to address the issue with appropriate action, such as putting your hand-up to take on additional work that might inspire you or finding productive ways to deal with a difficult colleague.

Self-managementDrawing on one’s self-awareness, self-management is the ability to regulate one’s emotions. Everyone – including those with a high EQ – experiences bad moods, impulses and negative emotions like anger and stress, but self-management is the ability to control these emotions rather than having them control you.

This could mean delaying response to highly stressful or aggressive situations. Deciding to sleep on that angry email or phone call means you can react thoughtfully and with a clear-head, rather than impulsively. Negative emotions and impulsive behaviour not only negatively affects those around you, but can take a toll on your wellbeing too.

MotivationMotivation is essentially what moves us to take action. When we face setbacks and obstacles, checking in with our motives is what inspires us to keep pushing forward.

Those with low motivation are more likely to be risk-averse (rather than problem-solvers), anxious and quick to throw in the towel. Their lack of motivation may also lead them to express negative feelings about project goals and duties, which can impact team morale.

Those motived by ‘achievement’ and doing work they’re proud of, on the other hand, are more likely to ask for feedback, monitor their progress, push themselves and strive to continually improve their skills, knowledge and output. It’s easy to see why people with high motivation are an asset to any team.

It’s easy to see why people with high motivation are an asset to any team.

Empathy is the ability to connect emotionally with others and take into consideration their feelings, concerns and points of view. It’s an important skill to have when negotiating with internal and external stakeholders and customers, as it enables one to anticipate the other’s needs and reaction.

In today’s workforce, emotionally savvy and intelligent managers assemble diverse teams whose unique perspectives and strengths they can leverage. Empathy is a key part of welcoming and appreciating different points of view to solve problems and come up with innovative ways forward.

Empathy is also essential for team harmony. Noticing and responding to the emotional needs of the people you work with makes for a happy work culture.

Relationship managementRelationship management is all about interpersonal skills – one’s ability to build genuine trust, rapport and respect from colleagues. This is about more than the cliché of a trust fall during a team building exercise – it’s about trusting and being trusted in a team.

This is about more than the cliché of a trust fall during a team building exercise – it’s about trusting and being trusted in a team.

A manager with outstanding relationship management skills is able to inspire, guide and develop their team members, greatly affecting team performance and productivity.

Final thoughts: although emotional intelligence seems to come naturally to some, our brain’s plasticity means we can increase our emotional intelligence if we’re willing to put in the work.

Realise your career potential with an MBA from La Trobe University.

Emotional Intelligence: What the Research Says

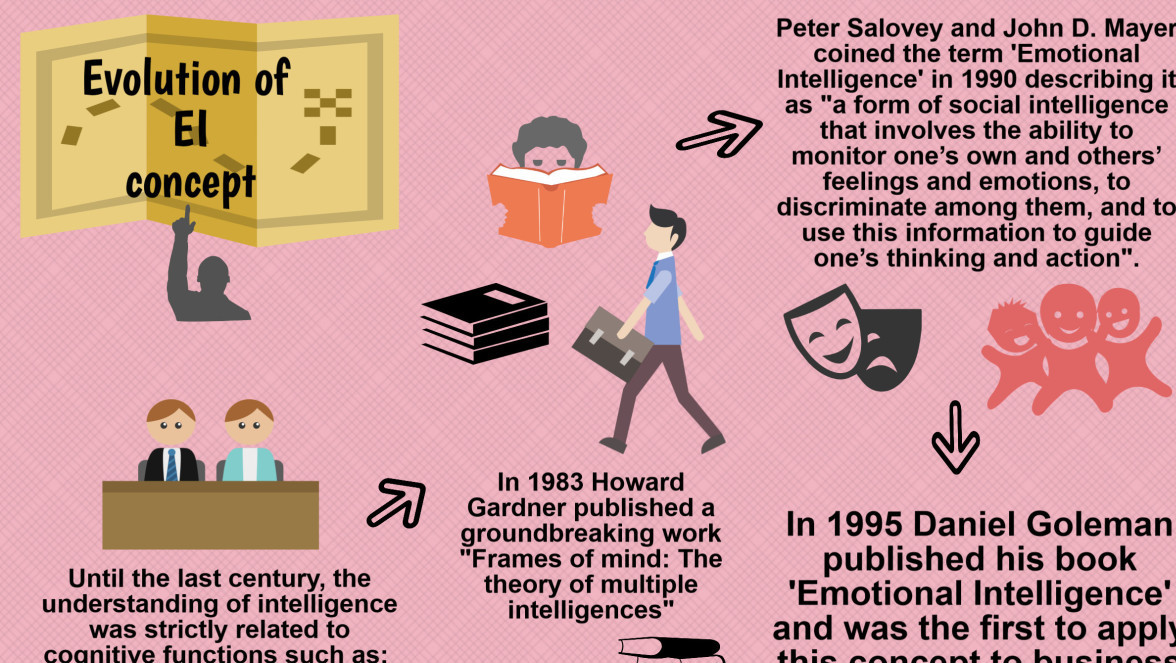

Emotional intelligence was popularized by Daniel Goleman's 1995 best-selling book, Emotional Intelligence. The book described emotional intelligence as a mix of skills, such as awareness of emotions; traits, such as persistence and zeal; and good behavior. Goleman (1995) summarized the collection of emotional intelligence qualities as "character. "

"

The public received the idea of emotional intelligence enthusiastically. To some, it de-emphasized the importance of general IQ and promised to level the playing field for those whose cognitive abilities might be wanting. To others, it offered the potential to integrate the reasoning of a person's head and heart. Goleman made strong claims: Emotional intelligence was "as powerful," "at times more powerful," and even "twice as powerful" as IQ (Goleman, 1995, p. 34; Goleman, 1998, p. 94). On its cover, Time magazine declared that emotional IQ "may be the best predictor of success in life, redefining what it means to be smart" (Gibbs, 1995). Goleman's book became a New York Times—and international—best-seller.

The claims of this science journalism extended easily to the schools. Emotional Intelligence concluded that developing students' emotional competencies would result in a "'caring community,' a place where students feel respected, cared about, and bonded to classmates" (Goleman, 1995, p. 280). A leader of the social and emotional learning movement referred to emotional intelligence as "the integrative concept" underlying a curriculum for emotional intelligence (Elias et al., 1997, pp. 27, 29). And the May 1997 issue of Educational Leadership extensively covered the topic of emotional intelligence.

280). A leader of the social and emotional learning movement referred to emotional intelligence as "the integrative concept" underlying a curriculum for emotional intelligence (Elias et al., 1997, pp. 27, 29). And the May 1997 issue of Educational Leadership extensively covered the topic of emotional intelligence.

Two Models

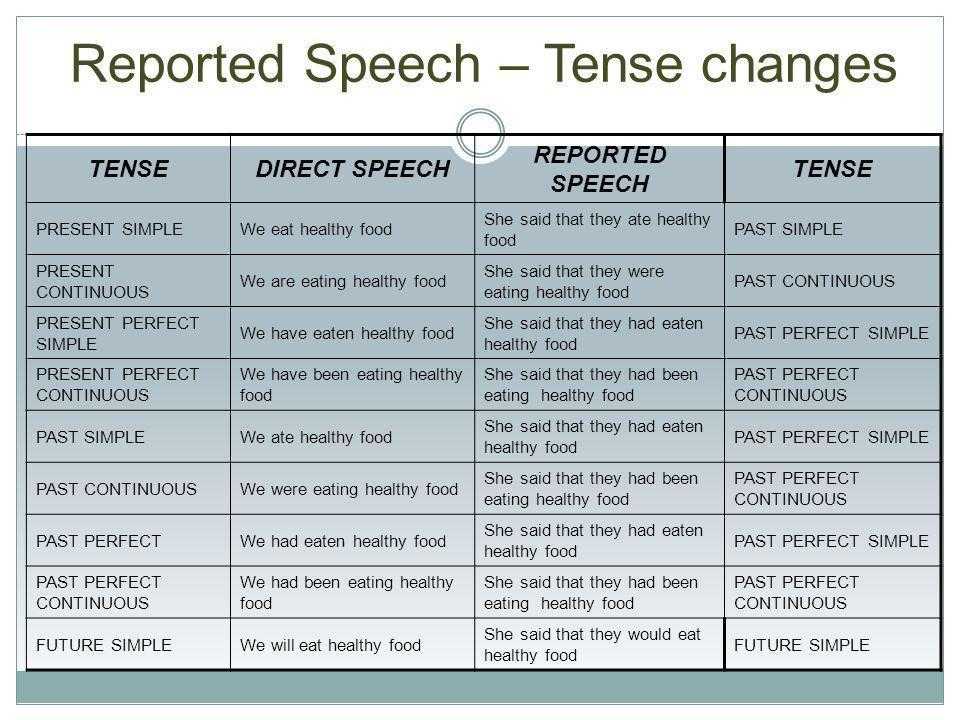

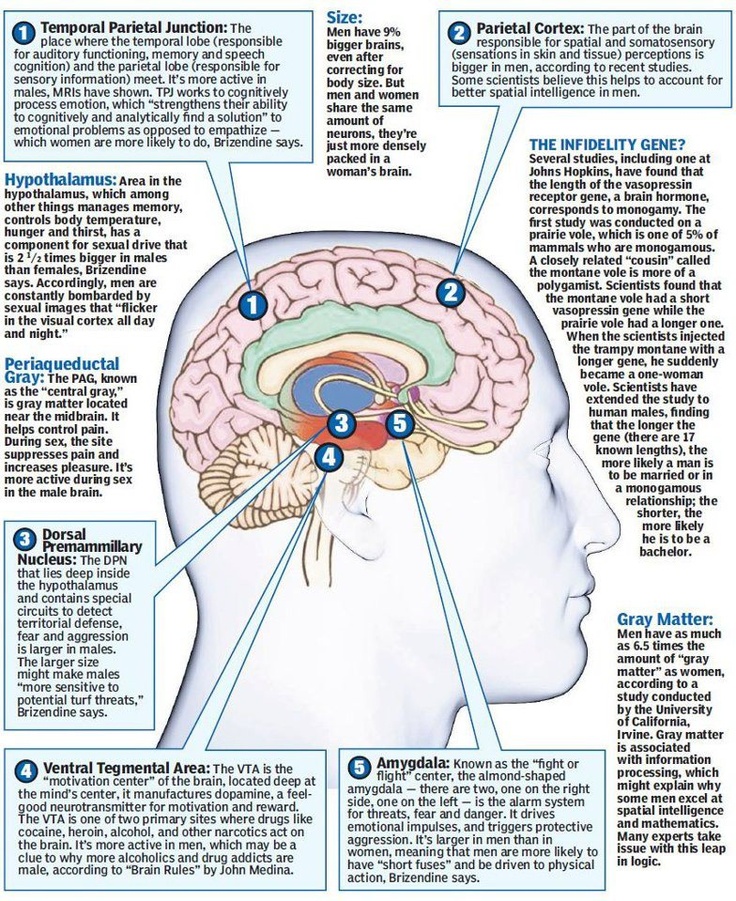

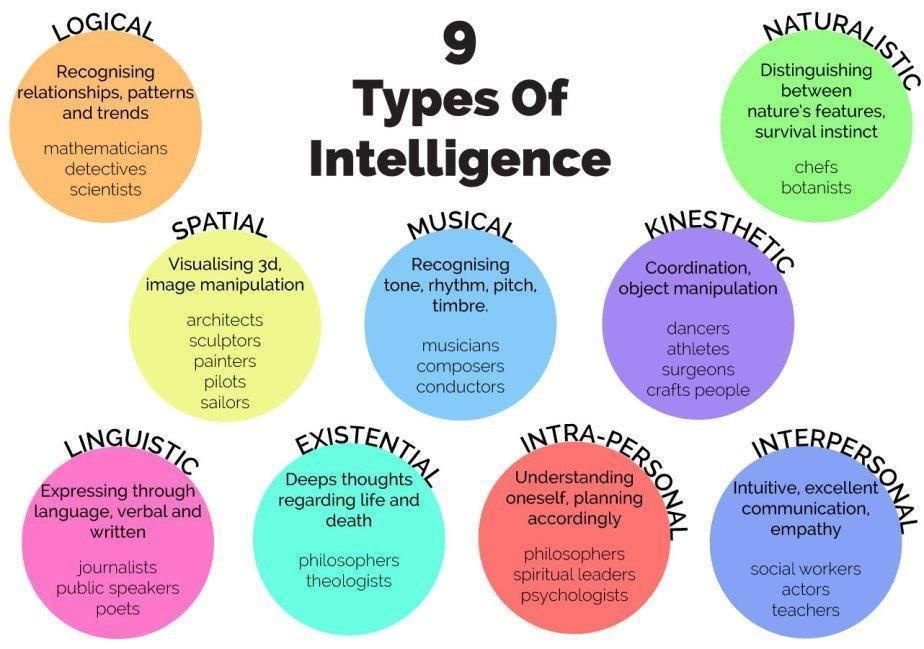

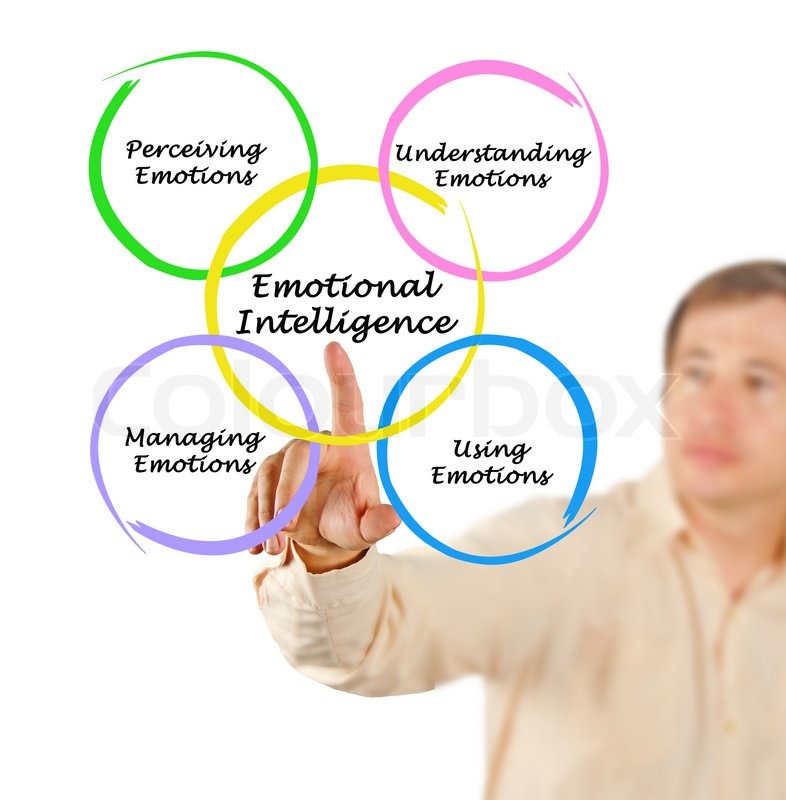

This popular model of emotional intelligence was based on, and added to, a 1990 academic theory and subsequent publications now referred to as the ability approach to emotional intelligence. The logic behind the ability model was that emotions are signals about relationships. For example, sadness signals loss. We must process emotion—perceive, understand, manage, and use it—to benefit from it; thus, emotional processing—or emotional intelligence—has great importance (Mayer & Salovey, 1997; Salovey & Mayer, 1990).

The ability model argued for an emotional intelligence that involves perceiving and reasoning abstractly with information that emerges from feelings. This argument drew on research findings from areas of nonverbal perception, empathy, artificial intelligence, and brain research. Recent empirical demonstrations have further bolstered the case (Mayer, Caruso, & Salovey, 1999; Mayer, DiPaolo, & Salovey, 1990; Mayer & Salovey, 1993; Salovey & Mayer, 1990).

This argument drew on research findings from areas of nonverbal perception, empathy, artificial intelligence, and brain research. Recent empirical demonstrations have further bolstered the case (Mayer, Caruso, & Salovey, 1999; Mayer, DiPaolo, & Salovey, 1990; Mayer & Salovey, 1993; Salovey & Mayer, 1990).

The ability model made no particular claims about the potential predictive value of emotional intelligence. In fact, even several years after the publication of Goleman's book, psychologists view the popular claims about predicting success as ill-defined, unsupported, and implausible (Davies, Stankov, & Roberts, 1998; Epstein, 1998). Rather, the ability version emphasizes that emotional intelligence exists. If emotional intelligence exists and qualifies as a traditional or standard intelligence (like general IQ), people who are labeled bleeding hearts or hopeless romantics might be actually engaged in sophisticated information processing. Moreover, the concept of emotional intelligence legitimates the discussion of emotions in schools and other organizations because emotions reflect crucial information about relationships.

Moreover, the concept of emotional intelligence legitimates the discussion of emotions in schools and other organizations because emotions reflect crucial information about relationships.

Two models of emotional intelligence thus developed. The first, the ability model, defines emotional intelligence as a set of abilities and makes claims about the importance of emotional information and the potential uses of reasoning well with that information. The second, which we will refer to as the mixed model, is more popularly oriented. It mixes emotional intelligence as an ability with social competencies, traits, and behaviors, and makes wondrous claims about the success this intelligence leads to.

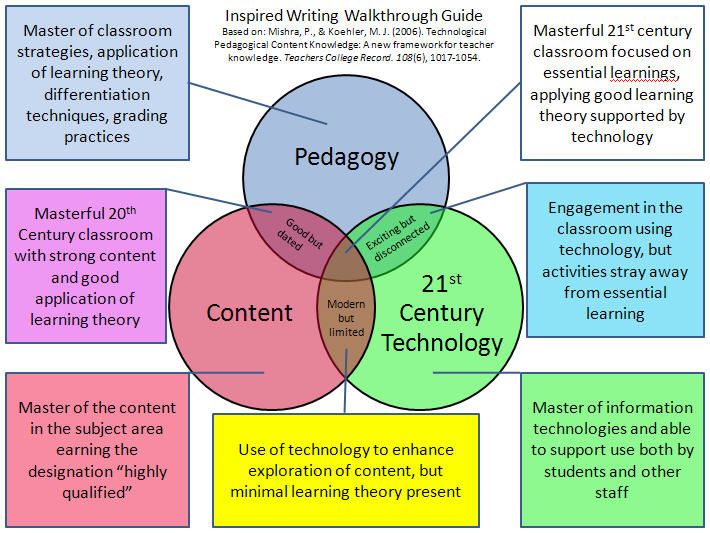

Educational leaders have experimented with incorporating emotional learning in schools. For the most part, emotional intelligence is finding its way into schools in small doses, through socioemotional learning and character education programs. But examples of grander plans are evolving, with a few schools organizing their entire curriculums around emotional intelligence. One state even attempted to integrate emotional learning into all its social, health, and education programs (Elias et al., 1997; Rhode Island Emotional Competency Partnership, 1998).

One state even attempted to integrate emotional learning into all its social, health, and education programs (Elias et al., 1997; Rhode Island Emotional Competency Partnership, 1998).

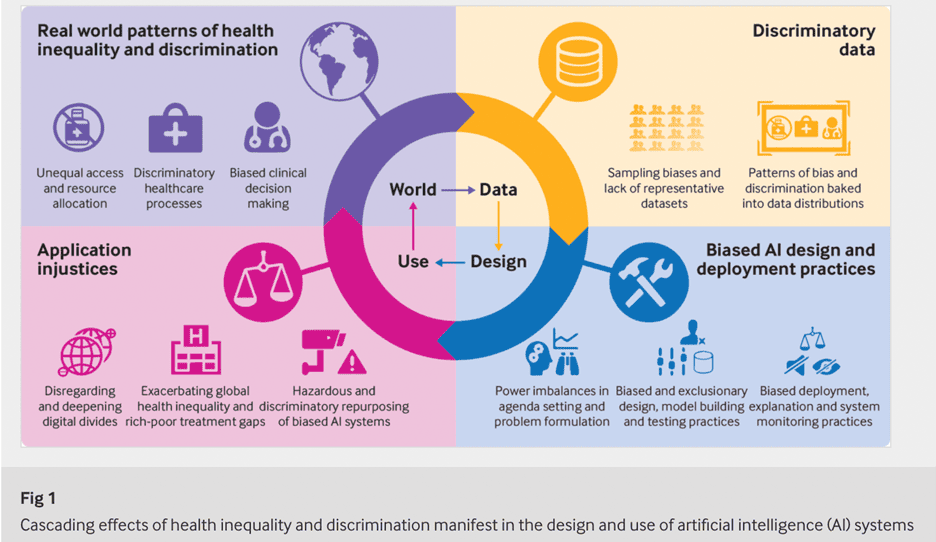

The problem is that some educators have implemented emotional intelligence programs and policies without much sensitivity to the idea that there is more than one emotional intelligence model. We have expressed concern that school practices and policies on emotional intelligence relied on popularizations that were, in some instances, far ahead of the science on which they were presumably based (Mayer & Cobb, 2000). The early claims of the benefits of emotional intelligence to students, schools, and beyond were made without much empirical justification.

We hope that emotional intelligence is predictive of life success or that it leads to good behavior, but we recognize that it is fairly early in the game. We are also wary of the sometimes faddish nature of school reform and the grave fate of other hastily implemented curricular innovations. Consider the rush by California to implement self-esteem programs into its schools in the late 1980s (Joachim, 1996). Substantial resources were exhausted for years before that movement was deemed a failure. The construct of emotional intelligence comes at a time when educators are eager to find answers to problems of poor conduct, interpersonal conflict, and violence plaguing schools; however, educational practices involving emotional intelligence should be based on solid research, not on sensationalistic claims. So, what does the research say?

Consider the rush by California to implement self-esteem programs into its schools in the late 1980s (Joachim, 1996). Substantial resources were exhausted for years before that movement was deemed a failure. The construct of emotional intelligence comes at a time when educators are eager to find answers to problems of poor conduct, interpersonal conflict, and violence plaguing schools; however, educational practices involving emotional intelligence should be based on solid research, not on sensationalistic claims. So, what does the research say?

Measuring Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence, whether academically or popularly conceived, must meet certain criteria before it can be labeled a psychological entity. One criterion for an intelligence is that it can be operationalized as a set of abilities. Ability measures—measures that ask people to solve problems with an eye to whether their answers are right or wrong—are the sine qua non of assessing an intelligence. If you measure intelligence with actual problems (such as, What does the word season mean?), you can assess how well a person can think. If you simply ask a student how smart she is (for example, How well do you solve problems?)—a so-called self-report—you cannot be certain that you are getting an authentic or genuine answer. In fact, the correlation between a person's score on an intelligence test and self-reported intelligence is almost negligible. Early evidence suggests that self-reported emotional intelligence is fairly unrelated to actual ability (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2000).

If you measure intelligence with actual problems (such as, What does the word season mean?), you can assess how well a person can think. If you simply ask a student how smart she is (for example, How well do you solve problems?)—a so-called self-report—you cannot be certain that you are getting an authentic or genuine answer. In fact, the correlation between a person's score on an intelligence test and self-reported intelligence is almost negligible. Early evidence suggests that self-reported emotional intelligence is fairly unrelated to actual ability (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2000).

Ability-based testing of emotional intelligence has centered on the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) and its precursor, the Multifactor Emotional Intelligence Scale (MEIS). Both tests measure the four areas of emotional intelligence: perception, facilitation of thought, understanding, and management (Mayer, Caruso, & Salovey, 1999). For example, look at the pictures of the faces on this page. Is the person happy? Sad? Are other emotions expressed? Identifying emotions in faces, pictorial designs, music, and stories are typical tasks for assessing the area of emotional intelligence called emotional perception.

Is the person happy? Sad? Are other emotions expressed? Identifying emotions in faces, pictorial designs, music, and stories are typical tasks for assessing the area of emotional intelligence called emotional perception.

Another type of MSCEIT question asks, When you are feeling slow and sour, which of the following emotions does this most closely resemble: (A) frustration, (B) jealousy, (C) happiness, or (D) joy? Most people would probably choose frustration because people become frustrated when they move too slowly and are disappointed (or sour) that things aren't going as planned. This kind of question measures the second area of emotional intelligence: emotional facilitation of thought.

A third type of MSCEIT question tests individuals' knowledge about emotions: Contempt is closer to which combination of emotions: anger and fear or disgust and anger? Such a question assesses emotional understanding.

The final type of MSCEIT questions measures emotional management. These questions describe a hypothetical situation that stirs the emotions (such as the unexpected break-up of a long-term relationship) and then ask how a person should respond to obtain a given outcome (for example, staying calm).

These questions describe a hypothetical situation that stirs the emotions (such as the unexpected break-up of a long-term relationship) and then ask how a person should respond to obtain a given outcome (for example, staying calm).

One crucial aspect of assessing emotional intelligence lies in the method by which answers are scored. Scoring a standard IQ test is fairly straightforward, with clear-cut, defensible answers for every item. The responses on a test of emotional intelligence are better thought of as fuzzy sets —certain answers are more right or plausible than others, and only some answers are absolutely wrong all the time. To assess the relative correctness of an answer, we can use consensus, expertise, or target criteria (or some combination). A correct response by way of the consensus approach is simply the answer most frequently selected by test-takers. Answers can also be deemed correct by such experts as psychologists or other trained professionals. Finally, correct responses can be validated using a target criterion. For instance, the actual emotional reaction of an anonymously depicted spouse facing a difficult decision could serve as the targeted response in a test item that described his or her situation.

For instance, the actual emotional reaction of an anonymously depicted spouse facing a difficult decision could serve as the targeted response in a test item that described his or her situation.

The MSCEIT and MEIS are undergoing considerable scrutiny from the scientific community. Although not everyone is convinced yet of their validity, the tests do provide the most dramatic evidence thus far for the existence of an emotional intelligence. Early findings provide strong evidence that emotional intelligence looks and behaves like other intelligences, such as verbal intelligence, but remains distinct enough to stand alone as a separate mental ability. Like other intelligences, emotional intelligence appears to develop with age (Mayer, Caruso, & Salovey, 1999).

Predictive Value

The first emotional intelligence tests were used two years after the popular claims of 1995, so the actual findings lag behind the popular perception of a well-established area of research. One important pattern is emerging, however. Preliminary research (primarily from unpublished studies and dissertations) from the MEIS suggests a modest relationship between emotional intelligence and lower levels of "bad" behaviors.

One important pattern is emerging, however. Preliminary research (primarily from unpublished studies and dissertations) from the MEIS suggests a modest relationship between emotional intelligence and lower levels of "bad" behaviors.

In one study, high scores in emotional intelligence moderately predicted the absence of adult bad behavior, such as getting into fights and arguments, drinking, smoking, and owning firearms (Mayer, Caruso, Salovey, Formica, & Woolery, 2000). In a dissertation study, the MEIS-A measured the emotional intelligence of fifty-two 7th and 8th graders in an urban school district (Rubin, 1999). Analyses indicated that higher emotional intelligence was inversely related to teacher and peer ratings of aggression among students. In another study, researchers reported that higher MEIS-A scores among 200 high school students were associated with lower admissions of smoking, intentions to smoke, and alcohol consumption (Trinidad & Johnson, 2000). The conclusion suggested by such research is that higher emotional intelligence predicts lower incidences of "bad" behavior. As for the claims about success in life—those studies have yet to be done.

As for the claims about success in life—those studies have yet to be done.

What Can Schools Do?

Educators interested in emotional intelligence of either the ability or mixed type are typically directed to programs in social and emotional learning (Goleman, 1995; Goleman, 1996; Mayer & Salovey, 1997). These programs had been around for years before the introduction of the emotional intelligence concept. Some aspects of the programs overlap with the ability approach to emotional intelligence. This overlap occurs when programs ask early elementary children to "appropriately express and manage" various emotions and "differentiate and label negative and positive emotions in self and others," or call for students to integrate "feeling and thinking with language" and learn "strategies for coping with, communicating about, and managing strong feelings" (Elias et al., 1997, p. 133–134). Other aspects of these programs are specifically more consistent with the mixed (or popular) models than the ability approach in that they include distinct behavioral objectives, such as "becoming assertive, self-calming, cooperative," and "understanding responsible behavior at social events" (p. 135). There is also an emphasis on such values as honesty, consideration, and caring.

135). There is also an emphasis on such values as honesty, consideration, and caring.

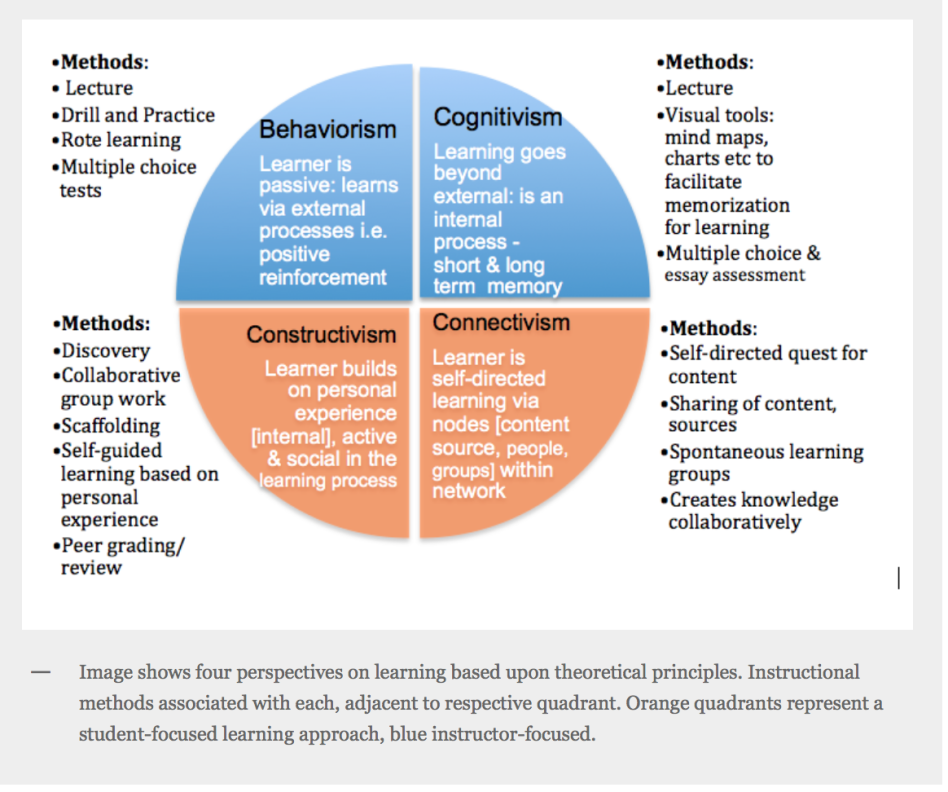

What would a curriculum based on an ability model look like? Basically, it would drop the behavioral objectives and values and focus on emotional reasoning.

Choosing Approaches

The emotional intelligence curriculum (or ability model) and the social and emotional learning curriculum (or mixed model) both overlap and diverge. The emotional ability approach focuses only on teaching emotional reasoning. The social and emotional learning curriculum mixes emotional skills, social values, and behaviors. In the case of these two approaches, less—that is, the pure ability model—may be better. What troubles us about the broader social and emotional learning approach is that the emphasis on students getting along with one another could stifle creativity, healthy skepticism, or spontaneity—all valued outcomes in their own right. Teaching people to be tactful or compassionate as full-time general virtues runs counter to the "smart" part of emotional intelligence, which requires knowing when to be tactful or compassionate and when to be blunt or even cold and hard.

Moreover, a social and emotional approach that emphasizes positive behavior and attitudes can be a real turn-off for a negative thinker—often the very student that the teacher is trying to reach. Research supports this concern: Positive messages appear less believable and less sensible to unhappy people than sad messages do (Forgas, 1995). We suspect that troubled students will be alienated by insistent positivity. There may be nothing wrong with trying such approaches, but they may not work.

What may work better, at least for some students, is helping them develop the capacity to make decisions on their own in their own contexts. This type of education is knowledge-based and is more aligned with an ability model of emotional intelligence. It involves teaching students emotional knowledge and emotional reasoning, with the hope that this combination would lead children to find their own way toward making good decisions.

Most children will require gentle guidance toward the good. We wonder, however, whether we can achieve this goal better by example and indirect teaching than by the direct, uniform endorsement of selected values in the curriculum.

We wonder, however, whether we can achieve this goal better by example and indirect teaching than by the direct, uniform endorsement of selected values in the curriculum.

How Might the Ability Curriculum Work?

The teaching of emotional knowledge has been a facet of some curriculums for years. For example, educators can help children perceive emotions in several ways. Elementary teachers could ask the class to name the feelings that they are aware of and then show what they look or feel like (for example, Show me sad). Similarly, teachers could ask students to identify the emotions depicted by various pictures of faces. Children can also learn to read more subtle cues, such as the speed and intonation of voice, body posture, and physical gestures.

Correctly perceiving emotional information is one way children make sense of things. The ability to perceive emotions can be further fine-tuned as a student ages. Consider the level of sophistication required for an actor to put on a convincing expression of fear—and for the audience to recognize it as such.

Students can also learn to use emotions to create new ideas. For instance, asking students in English class to write about trees as if they were angry or delighted facilitates a deeper understanding of these emotions.

Understanding emotions should also be a goal of the curriculum. For example, social studies expert Fred Newmann (1987) has suggested that higher-order thinking can be enhanced through empathic teaching. A social studies teacher could show images of the Trail of Tears, the forced exodus of the Cherokee from their homeland, and have students discuss the feelings involved. This could help students vicariously experience what those perilous conditions were like. In literature courses, teachers who point out the feelings of a story character, such as a triumphant figure skater or a despairing widow, can teach a great deal about what emotions tell us about relationships. Because the ability version of emotional intelligence legitimizes discussing emotions by considering them to convey information, it also supports emotionally evocative activities—such as theater, art, and interscholastic events—that help kids understand and learn from personal performance.

Emotional Intelligence in Schools

Educators looking to incorporate emotional intelligence into their schools should be aware that the two different models of emotional intelligence suggest two somewhat different curricular approaches. The model of emotional intelligence that makes its way into schools should be empirically defensible, measurable, and clear enough to serve as a basis for curriculum development. We believe that an ability-based curriculum, which emphasizes emotional knowledge and reasoning, may have advantages because it reaches more students.

90,000 "Emotional Intelligence" in 12 minutes. Summary of Goleman's bookEmotions help us learn new things, understand other people and push us to action

Do emotions hold us back? Maybe it's better to be insensitive, logically thinking beings?

Emotions are vital - they allow you to live a full life and learn from your experience.

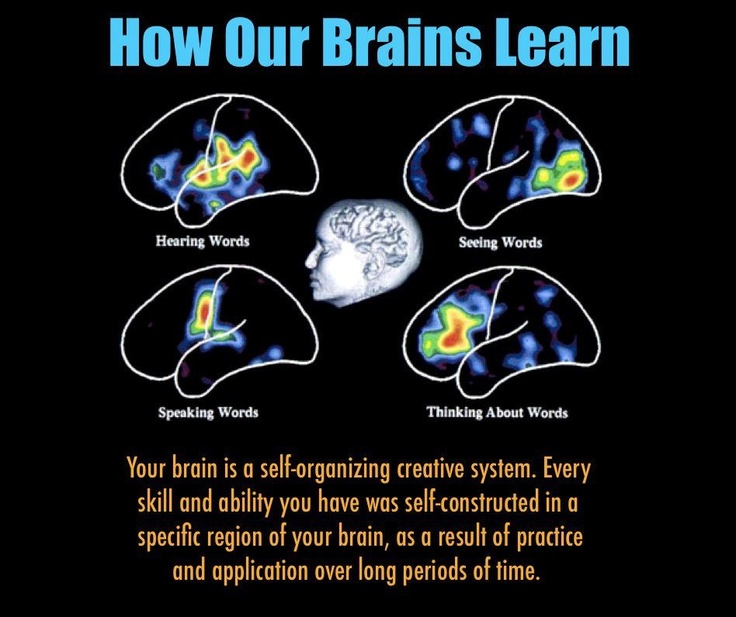

Example. The brain not only accumulates facts, but also remembers feelings. If you touch a hot stove, it will hurt. In the future, such an idea will revive the feeling of pain in memory. So emotions will not let you make the same mistake.

If you touch a hot stove, it will hurt. In the future, such an idea will revive the feeling of pain in memory. So emotions will not let you make the same mistake.

Advertising:

Emotions help interpret other people's feelings and predict their actions.

Example. Imagine that you are standing face to face with an angry person. Body language (clenched fists or loud voice) tells you about his emotional state, and you can predict his next actions.

Emotions help you quickly respond to a situation.

Example. In the case of an angry person, emotions will make us feel threatened or angry, allowing us to react quickly to the attack.

People without emotions are unable to act.

Example. In past centuries, many mentally ill patients have been treated with "lobotomy", which separates two areas of the brain vital for emotional processes. As a result, patients lost their initiative and drive to act, as well as much of their emotional potential.

Sometimes emotions get in the way of making a decision or make you act unwisely

Although emotions are an important tool for interacting with the environment, they are imperfect and can lead to erroneous actions.

This happens when we get overly emotional. Our mind is able to "juggle" many elements at the same time, but in a state of excitement it is overcome by disturbing thoughts and images. There is no room for rational thinking, and judgment becomes clouded.

Advertising:

Example. When you are frightened, you overreact to the situation (“fear has big eyes”) and you can even mistake a sheet on a clothesline for a ghost.

Under the influence of emotions, we rush to act instead of assessing the situation soberly. When information enters the brain, part of it enters the “new cortex” area responsible for rational thinking and passes to the emotional brain. If the latter considers that the information is a threat, he can force us to act without thinking, without resorting to the thinking brain.

Example. You shudder if you see a strange figure out of the corner of your eye in a dark forest.

Under the influence of outdated emotional reactions, we can behave unreasonably. The emotional mind reacts to the current situation based on experience, even if its conditions have changed.

Example. A boy who was beaten by his peers at school may grow up to be a strong man, but still feel threatened by others.

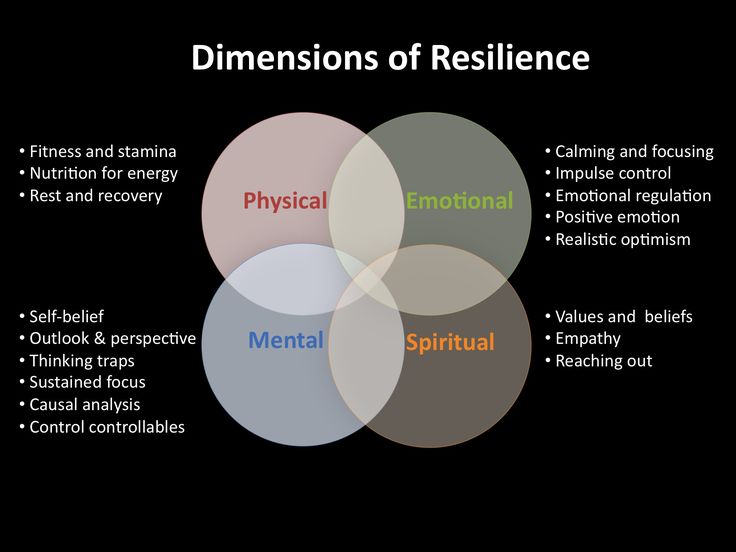

Emotions are very important, but they can block rational thinking. To prevent this from happening, you need to learn how to effectively manage emotions.

Advertising:

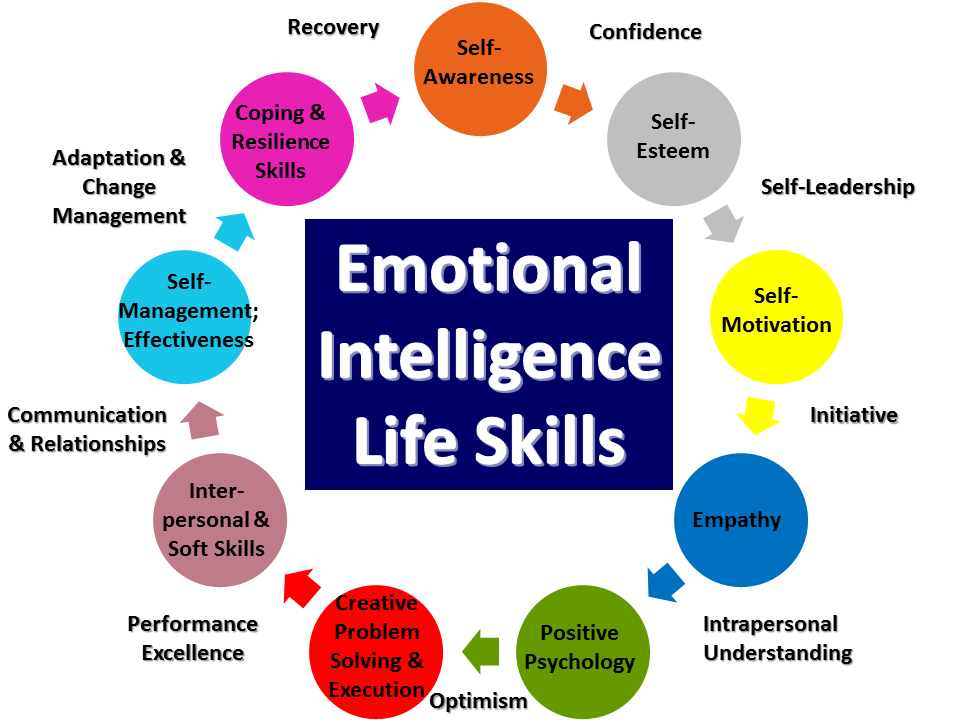

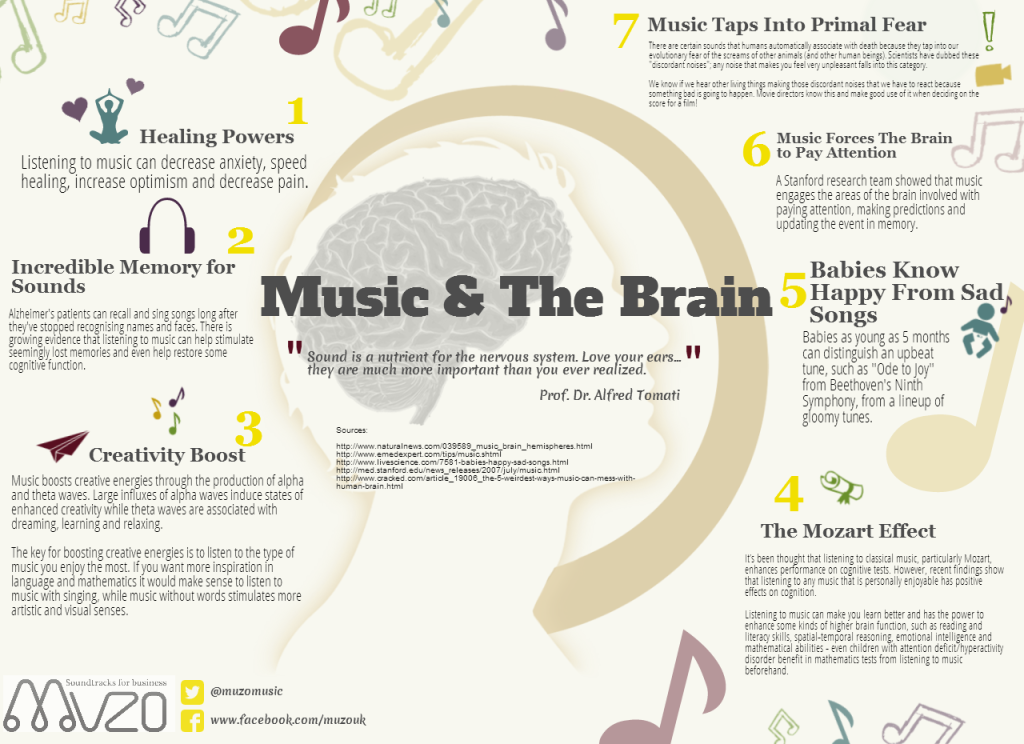

Emotional intelligence allows you to manage emotions and use them to achieve goals

How to use the power of emotions, eradicating their all-consuming influence?

Emotional intelligence will help you recognize and manage feelings without falling under their total control.

The first aspect of emotional intelligence is the ability to recognize and name your feelings. This skill is vital. People who are unable to recognize their own feelings are more prone to fits of rage. Understand your emotions, and you will immediately understand the reasons for their occurrence.

This skill is vital. People who are unable to recognize their own feelings are more prone to fits of rage. Understand your emotions, and you will immediately understand the reasons for their occurrence.

Often how you feel about a situation depends on how you feel about it.

Example. If a friend passes by on the street without recognizing you, you will immediately assume that he is doing it on purpose. This may upset or even anger you. But a friend might just not notice you.

When you can recognize and manage your feelings, emotional intelligence will help you focus on achieving certain goals.

Example. Let's say you need to write an article. You don't like the given topic and would rather go to the movies instead. Emotional intelligence will help you manage these different feelings. You can try to look at the topic from a different point of view. Perhaps some aspect of it will interest you. And knowing what feelings going to the cinema will cause, you can postpone this pleasure for a while, anticipating it.

Advertising:

Students who manage their workload tend to do well, even if they have an average IQ.

Emotional intelligence helps you navigate the social world

The people around you play a big role in your life. Only by managing social interaction can one hope for a fulfilling happy life. Emotional intelligence contributes to the development of social interactions, allowing you to put yourself in the place of other people. You can understand the emotions of other people by analyzing non-verbal signs. To judge a person's mood, it is enough to pay attention to the clues (facial expression or body language). We usually detect such signals automatically.

Example. If a person turns pale and opens his mouth in amazement, it means that he is in shock.

Since emotional intelligence allows you to empathize with people, you will behave in a way that will elicit a favorable reaction from others.

Example. Imagine that you are a manager and one of the team members constantly makes the same mistakes. You have to tell him about it and help him change, but do it right. If you hurt a person's feelings, he may become defensive and unlikely to do what you want. But by showing compassion and putting yourself in his place, you will definitely achieve your goal.

You have to tell him about it and help him change, but do it right. If you hurt a person's feelings, he may become defensive and unlikely to do what you want. But by showing compassion and putting yourself in his place, you will definitely achieve your goal.

Advertising:

Emotionally intelligent people can develop social skills: teach others, resolve conflicts, or manage staff. And these abilities help to maintain relationships in a social environment.

Emotional intelligence needs a balance between the emotional "feeling brain" and the rational "thinking brain"

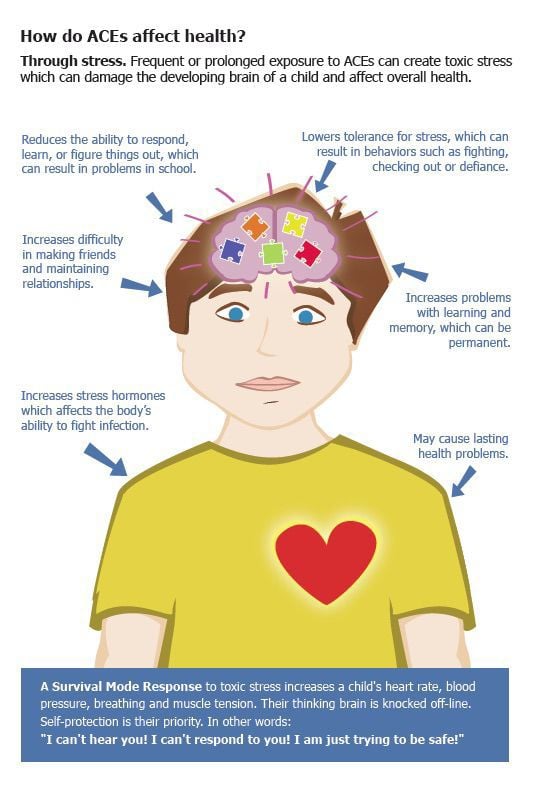

Our thoughts and feelings are intertwined. The brain of thinking (the stronghold of rational thought) and the brain of feeling (the birthplace of our emotions) are inextricably linked with the help of neural pathways. Emotional intelligence depends on the connectors between the brains of thinking and feeling, and any damage to these pathways can lead to a deficiency in emotional intelligence.

Example. A person whose emotional brain is separated from the thinking one ceases to experience feelings and loses emotional self-awareness. Lobotomized patients exhibit this affliction: after the connections between the two brains are interrupted, they lose their emotional potential.

The thinking brain must correct the functioning of the feeling brain. It is a process of emotional self-regulation.

Advertising:

How does emotional self-regulation work?

Stimuli such as sudden loud bangs often overwhelm the emotional brain. The sensory brain automatically perceives the stimulus as a threat and puts the body on alert. To regulate this process, we use the brain of thinking.

Hearing a loud bang, the emotional brain sends a signal to the body, the thinking brain checks the stimulus for a potential threat. In the absence of danger, it calms both the sensory brain and the body, allowing us to think clearly again. Therefore, we are not too afraid of every sudden noise. If you break the connection between the two brains, such a process is impossible.

If you break the connection between the two brains, such a process is impossible.

Example. Patients with severe thinking brain damage have difficulty managing their feelings.

Emotional intelligence helps to be healthy and successful

What is the secret of a successful and fulfilling life? Many people think that with a high IQ, people have a better chance of a happy life. Experience shows that people with developed emotional intelligence are often more successful.

Advertising:

Students with a high level of empathy are more successful than their less empathetic peers with a similar IQ. In general, students who are able to control their feelings get high marks.

Example. One Stanford University study looked at the ability of a group of four-year-olds to resist a treat. Years later, those who controlled their impulses at age four were found to be doing well in school and socially. Success accompanied them into adulthood.

Emotional intelligence also helps you lead a healthier lifestyle.

Example. During periods of stress, the heart experiences tremendous strain as blood pressure rises. Hence the risk of a heart attack. Stress also weakens the immune system - in a stressful state, the chances of catching a cold are high. Emotional intelligence will help you avoid such dangers. By learning to mitigate stressful feelings such as anxiety and anger, you will reduce their harmful effects. So, if people who have suffered a heart attack are taught to manage anger, then the risk of attacks in the future will be significantly reduced.

Advertising:

The influence of emotional intelligence on success and health is huge, but in the school curriculum almost no attention is paid to emotional skills.

The image of society depends on the emotional intelligence of children

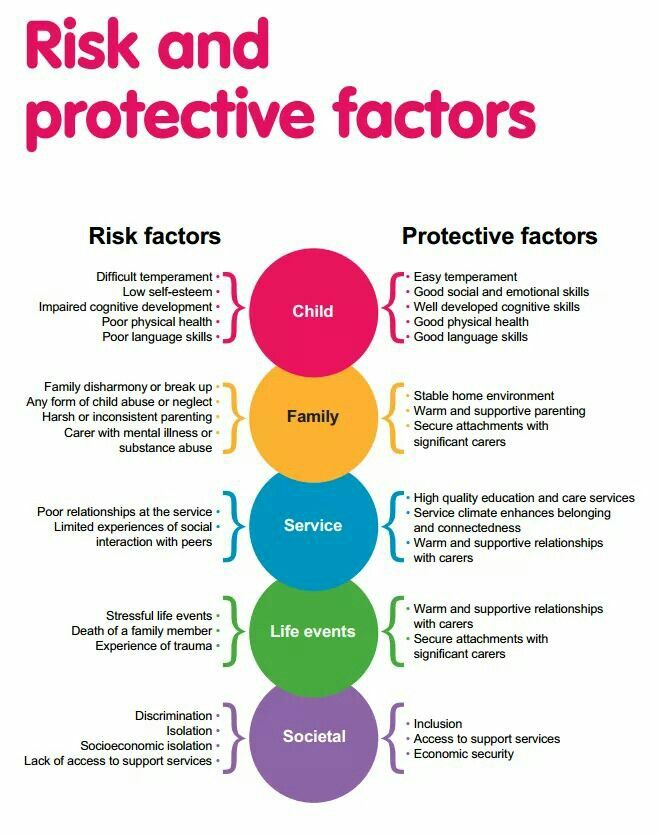

Weak emotional intelligence can lead to negative consequences throughout society.

Example. Threefold increase in teen homicides between 1965 and 1990 may be associated with a weakening of emotional intelligence.

A lack of emotional intelligence can lead to an increase in crime.

Example. Studies show that juvenile delinquents find it difficult to control their feelings and "read" other people's facial expressions - just like sex maniacs. And heroin addicts had difficulty managing anger even before their addiction began.

A child's well-being is also determined by emotional competence. Children growing up surrounded by emotionally intelligent people have a high level of EI. Children of emotionally intelligent parents find it easier to control their own emotions. They are less prone to stress, are more favored by their peers, and are more socially adjusted according to their teachers. Children with deficits in self-awareness, empathy, or impulse control are at risk of mental health problems and are more likely to experience difficulties in school.

Advertising:

Modern children are future parents, managers and politicians. Many of them will have a great impact on society and it is better that they are not indifferent, able to resolve conflicts and not be inclined to blindly follow the feelings.

Ways to improve your emotional intelligence

Emotional intelligence ensures a fulfilling life. How to increase its level?

1. To increase your level of self-awareness and self-control, practice self-talk. This will help you recognize your own feelings.

Example. If your friend tells everyone except you about his marital problems, you may get upset. An internal dialogue will help solve this problem. Ask yourself, "Why am I hurting?" and answer the question: "Because my best friend shared his family problems with everyone but me." Once you have identified the feeling and its cause, weaken its influence. Tell yourself, "I may feel like an outcast, but maybe he didn't want to bother me because I was busy doing my annual accounts. " This way you will be less upset.

" This way you will be less upset.

2. To develop empathy, try copying the other person's body language. This is useful because body language not only expresses emotions, but also evokes them.

Example. By copying the tense posture of another person, you can cause tension in yourself.

3. To increase self-motivation and think more positively, think like this: people who are convinced that they can change the reasons for failure do not give up easily. They do not stop trying because they are sure that success depends on their own actions.

How you explain your successes and failures greatly affects your self-motivation. And vice versa: those who associate failures with personality flaws will give up in the near future. Such people are convinced that they will not be able to achieve success. If you want to become successful, drive such thoughts away from yourself.

Advertising:

The most important thing

Emotions play a much larger role in thinking, decision-making and personal success than is commonly thought. IQ is not your destiny. Emotionally intelligent people succeed more often: their relationships thrive, they are stars at work. Remember that emotional intelligence can be "nurtured" in each of us.

IQ is not your destiny. Emotionally intelligent people succeed more often: their relationships thrive, they are stars at work. Remember that emotional intelligence can be "nurtured" in each of us.

- Use emotional intelligence to understand your emotions.

- Once you understand your emotions, you will understand the reasons for their occurrence and will be able to manage them or reduce their negative impact.

- Emotional intelligence will help you focus on achieving certain goals.

- A balance is needed between the emotional "feeling brain" and the rational "thinking brain". At the same time, the "brain of thinking" is able to correct the functioning of the "brain of feelings" with the help of emotional self-regulation, preventing emotions from gaining total control.

How bosses should react to troubles

Varvara Grankova / Vedomosti

At work, we experience various emotions (frustration, anger, fear, excitement), and this is normal. How well leaders deal with these feelings determines how creative or disruptive the work environment is, how motivated or frustrated employees are. The leader's ability to manage his feelings determines the morale and motivation of the team. Mark Bracket, director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, explains that emotion regulation may be the single most important feature of emotional intelligence.

How well leaders deal with these feelings determines how creative or disruptive the work environment is, how motivated or frustrated employees are. The leader's ability to manage his feelings determines the morale and motivation of the team. Mark Bracket, director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, explains that emotion regulation may be the single most important feature of emotional intelligence.

Example: A football team concedes one goal in a decisive match. At the very end of the first half after the violation, the team gets the right to shoot a penalty - a great opportunity to equalize. The leading player of the team is ready to hit the ball. First, the ball rushes to the corner of the net, but suddenly bounces back. The player grabs his head and leaves the field for a break.

The team is upset, and so is the coach. His goal is to help the team overcome the setback during the break so that the players take the field in high spirits and motivated to win. Should he deal with his disappointment, put on a smile on his face and act like nothing happened? Or should he, without restraint, express his feelings? Which option will help you achieve your goal?

Should he deal with his disappointment, put on a smile on his face and act like nothing happened? Or should he, without restraint, express his feelings? Which option will help you achieve your goal?

According to research, people tend to control their emotions, either by suppressing or overestimating them. Suppression is the most common way: we hide our feelings and pretend that everything is fine. Despite its popularity, this strategy leads to a whole range of negative consequences for the individual: fewer friends and relatives, an increase in the share of negative emotions, dissatisfaction with life, memory impairment and high blood pressure. If the coach hides his anger, it can lead to similar consequences for all players. Even if they are not aware of the anger he is hiding, on a psychological level they feel it and feel it as an alarm signal.

Full expression of emotions might seem like a more effective strategy. But it also has its devastating consequences. If the coach expresses disappointment at this critical moment, he may shake the confidence of the players. And instead of motivation and inspiration, he will leave his players oppressed and full of fear.

And instead of motivation and inspiration, he will leave his players oppressed and full of fear.

Reassessment, or revision of the emotional situation, may be the most effective strategy. For example, a coach might remind himself that this is not the end, but that it is only one game of the season and the team still has an opportunity to win. Reassessment helps to calm down and realize that the players are already experiencing frustration and they need to be supported rather than oppressed. The coach might start the conversation by acknowledging the general frustration and then emphasize that the final results will depend on how they all handle this challenge and bounce back in the second half.

We recently conducted a study of 15 university coaches and their athletes. Coaches who followed the reappraisal strategy experienced fewer negative experiences than those who sought to suppress them. In addition, coaches who overestimated emotions created a more positive atmosphere in the team, built trusting relationships, communicated easily and motivated.

Another study shows that emotion regulation is a core competency not only for sports coaches, but also for generally successful leaders. After all, one of the distinguishing features of a strong leader is the ability to influence the emotional state of subordinates. Leaders must be able to inspire and instill confidence in employees so that they stay motivated and cope with difficulties. And for this, the leader must be able to manage his own feelings.

One study found that leaders who received bad news by reviewing their emotional situation rather than suppressing their emotions were better at managing employees' reactions to the bad news. And the first reaction of the employees was anger at the authorities and dissatisfaction with his actions.

It is difficult to overestimate emotions in a critical situation. But there is a useful way: try to perceive the problem as a challenge, not as a threat. This will help people focus on the task and think about the next steps.