What you have to say

WHAT DO YOU HAVE TO SAY FOR YOURSELF? definition

Translations of what do you have to say for yourself?

in Chinese (Traditional)

你還有甚麽好說的? 你如何解釋?…

See more

in Chinese (Simplified)

你还有什么好说的?你如何解释?…

See more

Need a translator?

Get a quick, free translation!

Browse

what are friends for? idiom

what are you going to do? idiom

what are you like? idiom

what do you bet? idiom

what do you have to say for yourself? idiom

what do you know idiom

what do you mean? idiom

what do you say idiom

what good is . .. idiom

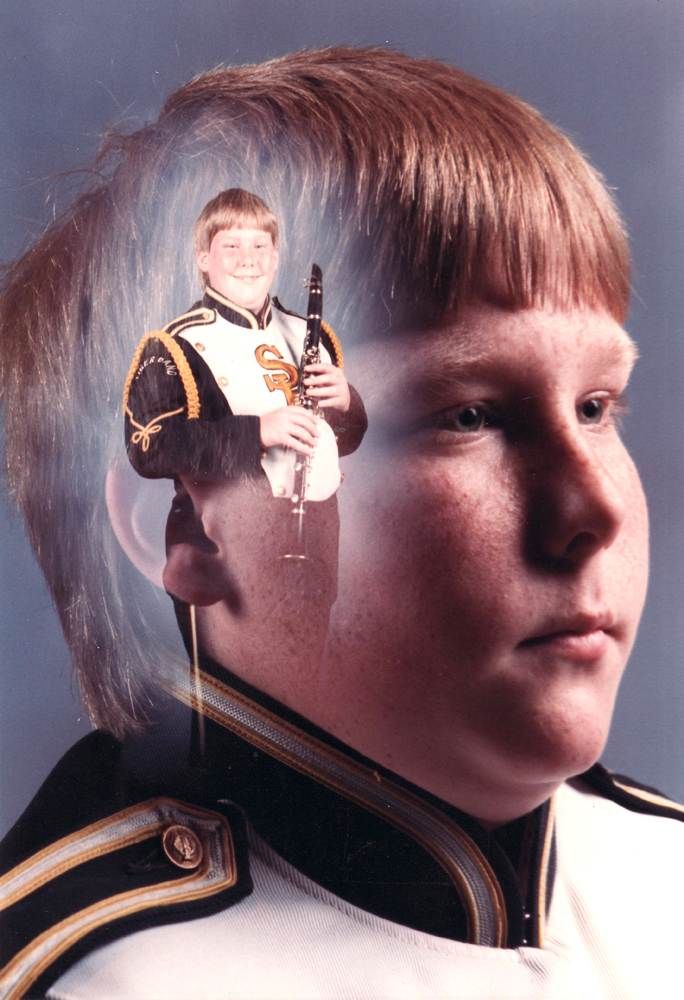

Test your vocabulary with our fun image quizzes

- {{randomImageQuizHook.copyright1}}

- {{randomImageQuizHook.copyright2}}

Image credits

Try a quiz now

Word of the Day

hiya

UK

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

/ˈhaɪ.jə/

US

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

/ˈhaɪ. jə/

jə/

an expression said when people who know each other well meet

About this

Blog

Hot air and bad blood (Idioms found in newspapers)

Read More

New Words

Great Wealth Transfer

More new words

has been added to list

To top

Contents

EnglishTranslations

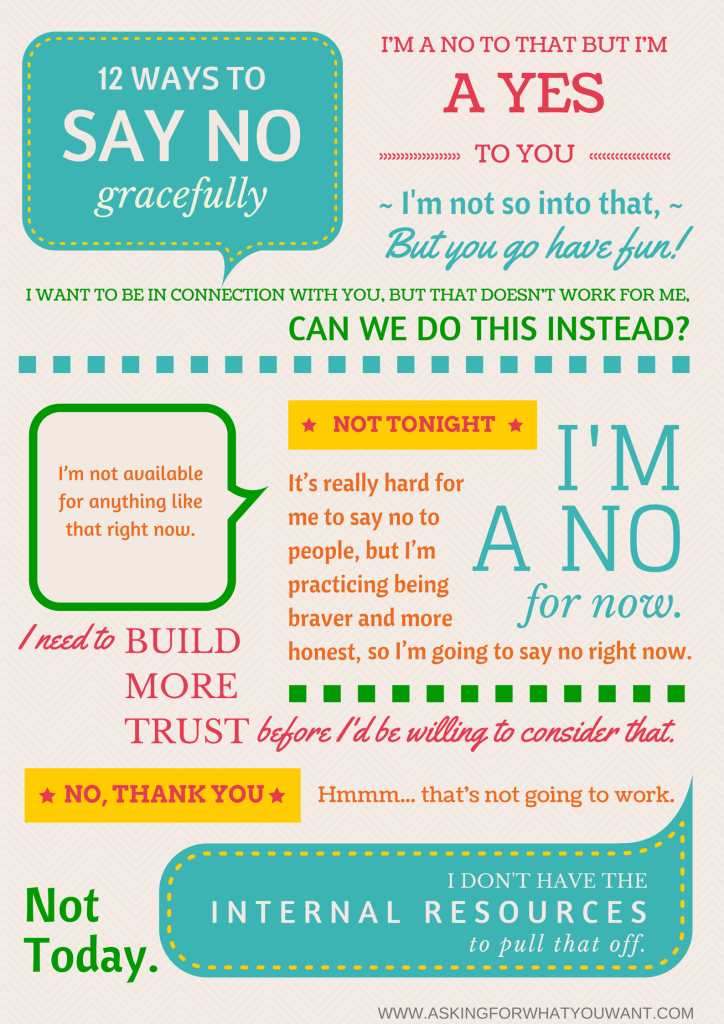

The Guilt-Free Guide to Saying No

Many of us hesitate to say no to others. With mindful tips like these, saying no is an emotionally intelligent skill anyone can master — really!

It’s just two letters, and yet saying no can feel really hard — even complicated. For many of us, saying no doesn’t just feel awkward. It feels wrong.

For many of us, saying no doesn’t just feel awkward. It feels wrong.

So, whenever anyone asks you to do almost anything, you might blurt out, “Yes! Sure! Of course! Happy to!”

But in reality, you may feel the opposite. Maybe you’d rather be doing about a thousand other things. Or maybe you’re OK with saying yes, but it’s not the best thing for your daily bandwidth or mental health.

Here’s the good news: Saying no is a skill you can sharpen. The more you say no, the more natural it’ll feel.

Here are several ways to build the skill of saying no in different situations — even if it feels like you’re doing it from the ground up.

For starters, it’s important to realize that if saying no is challenging for you, you’re not alone.

As social psychologist Dr. Vanessa K. Bohns writes in a 2016 research review examining people’s influence over others, “Many people agree to things — even things they would prefer not to do — simply to avoid the considerable discomfort of saying ‘no. ’”

’”

For example, a series of small studies, published in 2014, found that when asked, many people would acquiesce and commit unethical acts, such as telling a white lie or vandalizing a book — even when they felt these acts were perceived as wrong.

As social creatures who want to be part of the herd, we also want to preserve our relationships. So, we might blurt out yes because we don’t want to be seen as difficult, says Dr. Emily Anhalt, a clinical psychologist and co-founder of Coa, an online mental fitness club.

Or, we don’t want to disappoint a good friend or hurt someone’s feelings, notes Dr. Nicole Washington, a board-certified psychiatrist and the chief medical officer of Elocin Psychiatric Services.

Another reason yes pours out of us? Our past.

According to Anhalt, while growing up, you might’ve not learned to advocate for yourself.

“It’s also possible that you say yes because you deeply want to help. But you forget that your ability to accommodate others isn’t an endless well,” Anhalt says.

In other cases — like a work situation — we might worry that saying no says something about our ability to accomplish a certain task, adds Washington. Put another way, we think declining makes us look incompetent.

When you struggle with saying no in personal or professional situations, it helps to remember the self-preservation in passing things up.

“Saying no is one of the best forms of self-care we can engage in,” Washington says. She notes that saying no supports us in:

- creating space in our schedules to rest and recharge

- engaging in activities that actually align with our current goals

- setting boundaries with loved ones and colleagues

Ultimately, saying no gives us greater navigation over our lives, says Anhalt. This grants us the opportunity to build a fulfilling, meaningful life on our own terms.

After all, we can only have power over ourselves — so, let’s exercise that power.

Sometimes, we say yes because we don’t know what we want. Other times, we simply need to gather ourselves enough to speak up.

Other times, we simply need to gather ourselves enough to speak up.

Either way, here’s your permission slip to start thinking about when it’s best for you to decline. To kick-start the discovery process, ask yourself these questions anytime you’re not positive about how to proceed:

- Will saying yes prevent me from focusing on something that’s more important?

- Does this potential project, opportunity, or activity align with my values, beliefs, and goals?

- What are my core values, beliefs, and current goals?

- Will saying yes make me even more tired or burnt out?

- Will saying yes be good for my mental health? Or will it worsen my symptoms?

- In the past, when have I said yes and then ended up regretting it?

- When am I more likely to accept a request I’d rather decline? How can I reduce these challenges?

Besides exploring the above questions, it can help to work with a therapist, if that’s available to you. According to Anhalt, “A therapist can help you identify both what you need and what blocks you from advocating for what you need. ”

”

Here’s what to do if you can’t afford therapy.

Here’s the other great thing about saying no: You can decline a request while still being kind, appreciative, and respectful. Below, you’ll find a simple, no-fuss framework for saying no, along with real-life examples.

Be crystal clear

A wishy-washy answer can make the conversation awkward and confuse the person making the request. They might think, “Do they want me to make other suggestions or accommodations?” or “Are they interested in the promotion but prefer to negotiate?”

Or, a flimsy no opens the door to difficult people bombarding you with their demands.

In short, “Be clear with your no, so that nobody is left wondering what you are trying to say,” encourages Washington.

Clear, kind ways to decline

- “Unfortunately, I’ll need to pass on this.”

- “I’m sorry, my friend, but I’m not able to.”

- “Sadly, I can’t.”

- “Thanks, but that’s not going to work for me.

”

” - “No, I’m not able to do that.”

Phrases to avoid

- “Umm, I don’t know.”

- “I’m not sure.”

- “It’s tough to say.”

- “Well, maybe I could do it. But…”

Extend genuine gratitude for the ask

You might have a hard time saying no because the request or person making the request means a lot to you. You’re sincerely grateful for being asked. So, naturally, you feel bad for saying no.

By all means, shower the other person with your appreciation, but still stand firm.

Expressing your gratitude

- “Thank you for thinking of me!”

- “I’m honored!”

- “I greatly appreciate you asking.”

- “You coming to me really means a lot.”

- “I’m immensely grateful.”

- “Rain check? Please don’t stop inviting me! I might be able to connect another time.”

Give a brief explanation — if you want to

“No” can be a complete sentence. Let that sink in.

But if you’d like to offer an explanation, keep it short and sweet, recommends Washington.

Everyday scenarios

- “Thanks so much for the party invite! I won’t be able to make it because I’m taking the weekend to regroup after this hectic week. It looks like it’ll be a great event. Have an amazing time!”

- “I greatly appreciate this opportunity! Unfortunately, I’m booked all month long. Thanks, again, for asking.”

Offer an alternative

Sometimes, you’d like to say yes but the timing is off. Or there’s some other reason you can’t accept. But you’d like to in the future.

If that’s the case, Washington suggests offering an alternative that you’re comfortable with (and one that honors your needs).

Everyday scenarios

- “I really appreciate you asking me to be on your podcast. I’m going to have to pass because I’m not doing any interviews while I write my book. However, please reach out to me in September.”

- “I’m honored you’d want me to be part of your project.

Unfortunately, my schedule is currently full. If we can push back the due date a few weeks, I’d be happy to participate.”

Unfortunately, my schedule is currently full. If we can push back the due date a few weeks, I’d be happy to participate.”

- “Unfortunately, I won’t be able to bake my famous lasagna. But I’m happy to grab takeout!”

- “I’m really sorry you’re having such a hard time. I can’t stay over all weekend, but I’m free at the moment. How can I support you now?”

Offer another resource

“If you have the time, desire, and [connections], offer another person or resource that they might look into,” Anhalt says.

Sharing other recommendations means you’re still being helpful — which, for many people, is a core value.

Everyday scenarios

- “Thank you so much for the invitation to speak at your event, it looks awesome! I’m not in a position to take on pro bono speaking engagements right now, so I’ll need to decline. Here are a few colleagues who might be interested.”

- “Hey, thanks for trusting me to help you move! Unfortunately, my knee is acting up again, but I personally know some college kids who’ve been asking for small jobs.

I can put you in touch and contribute to the fund!”

I can put you in touch and contribute to the fund!”

In some cases, you’re just not sure what you’d like to do. Maybe it’s an amazing opportunity and you want to try to rework your schedule. Perhaps you’d like to help out a friend, but it’s a big ask.

Before you say no, figure out what you actually want. As Washington remarks, is it a true-blue, full-blown no? Or is it a not now?

For example, you don’t have the bandwidth for a fun work project right now, but you think you will next month.

Either way, you need time to think it through. So, take it.

Washington suggests considering the negative and positive consequences of accepting or declining a request.

As she notes, “taking a breath and a few minutes can allow you to be more thoughtful in your no and possibly prevent you from a knee-jerk yes”— or even a hasty no.

Saying no is hard for many people. So, we blurt out yes to requests we’d rather decline — and frequently end up regretting it.

“We often believe that we are protecting other people by saying yes when we want to say no,” Anhalt says. But being transparent about our feelings, needs, and limits leads to healthier, more authentic relationships, she says.

And saying no and honoring your feelings, needs, and limits also leads to a healthier you.

Thankfully, saying no is a skill anyone can build. The key is to keep practicing.

What I have to say is Vertinsky. Full text of the poem - What I have to say

Literature

Catalog of poems

Alexander Vertinsky - poems

Alexander Vertinsky

What I have to say

I don't know why and to whom it is needed, who sent it

them to death with an unshaking hand,

Only so mercilessly, so evil and unnecessary

Lowered them into Eternal Peace!

Cautious spectators silently wrapped themselves in fur coats,

And some woman with a distorted face

Kissed the deceased on blue lips

And threw a wedding ring at the priest.

They pelted them with Christmas trees, kneaded them with mud

And went home - talking on the sly,

That it's time to put an end to the disgrace,

That already soon, they say, we will begin to starve.

And no one thought of just kneeling down

And telling these boys that in a mediocre country

Even bright deeds are only steps

Into endless abysses - to inaccessible Spring!

1917

About the war

Poems by Alexander Vertinsky - About the war

Other poems by this author

Kokainetka

About a woman

Purple Negro

V. ColdWhere are you now? Who kisses your fingers?

Where did your Chinese Li go?..

About a woman0003

Wound up in broad daylight!

About children

Magnolia tango

In banana-lemon Singapore, in the storm

When the ocean sings and cries blue pajamas

About a woman

Your fingers

Your fingers smell of incense,

And sadness sleeps in your eyelashes.

About woman

How to read

Publication

How to read the “Crime and Punishment” of Dostoevsky

We talk about a large -scale psychological study of the Russian classic

Publication

How to read the White Guard Bulgakov

Literary tradition, Christian images and reflections on the end of the world

Publication

How to read how "The Enchanted Wanderer" by Leskov

Why Ivan Flyagin turns out to be a righteous man, despite his far from sinless life

Publication

How to read poetry: the basics of versification for beginners

What is rhythm, how to distinguish iambic from chorea, and can poetry be without rhyme

Publication

How to read Shmelev’s “Summer of the Lord”

religious images

Publication

How to read Blok's "The Twelve"

What details should be paid attention to in order not to miss the hidden meanings in the poem

Publication

How to read Bunin's "Dark Alleys"

What to pay attention to in order to understand Ivan Bunin's famous story

Publication

How to read Kuprin's "Garnet Bracelet"

What a modern reader should know in order to truly understand the tragedy of an official in love

Publication

How to read Pasternak's Doctor Zhivago

We talk about the key themes, images and conflicts of Pasternak's novel

Publication

How to read Nabokov

Motherland, chess, butterflies and color in his novels

Kultura. RF is a humanitarian educational project dedicated to Russian culture. We talk about interesting and significant events and people in the history of literature, architecture, music, cinema, theater, as well as folk traditions and monuments of our nature in the format of educational articles, notes, interviews, tests, news and in any modern Internet formats.

RF is a humanitarian educational project dedicated to Russian culture. We talk about interesting and significant events and people in the history of literature, architecture, music, cinema, theater, as well as folk traditions and monuments of our nature in the format of educational articles, notes, interviews, tests, news and in any modern Internet formats.

- About the project

- Open data

© 2013–2022, Russian Ministry of Culture. All rights reserved

Contacts

- E-mail: [email protected]

- Found a typo? CTRL+Enter

Materials

When quoting and copying materials from the portal Active hyperlink is required

90,000 Festival Lyubimovka - “If you need to say something, you have to say”IMAN IMAN

Ismail Iman from Baku made his debut this year at Lyubimovka, but could not come due to the cancellation of flights between Azerbaijan and Russia.

We got in touch with Ismail and talked about his play, about theater and cinema in modern Azerbaijan, about the pandemic and the creative impulses that Lyubimovka is broadcasting online this year.

We got in touch with Ismail and talked about his play, about theater and cinema in modern Azerbaijan, about the pandemic and the creative impulses that Lyubimovka is broadcasting online this year.

Ismail, you are a writer, playwright and screenwriter, since 2017 you have been taking places in the longs and shorts of international competitions. You are a member of the jury of the German Badenweiler drama competition, but judging by my Google searches, Pavel Rudnev discovered you in the Russian theater community only this year. Do you have any ideas why this happened?

I have been writing plays for ten years now, but there is a big break, so I set 2017 as a starting point for myself. In 2018, I participated in the “First Reading” with the play “Gardens of Astara”, that is, this is not the first time my play has been in Russia at Lyubimovka. Then I was at Badenweiler with the same play, took third place and got into different longs. Then there was another break, connected with the fact that I wanted to write something more successful, or at least repeat the first success. For about a year, I definitely didn’t have any plays: I kept thinking about what to write, and the topic didn’t come up. And this year it so happened that I wrote two plays in a row, and one of them shot. I myself was surprised when I found myself on the Rudnev list, and I already thought that okay, then you can get to Lyubimovka.

Then there was another break, connected with the fact that I wanted to write something more successful, or at least repeat the first success. For about a year, I definitely didn’t have any plays: I kept thinking about what to write, and the topic didn’t come up. And this year it so happened that I wrote two plays in a row, and one of them shot. I myself was surprised when I found myself on the Rudnev list, and I already thought that okay, then you can get to Lyubimovka.

How acute and taboo is the topic of drugs in Azerbaijan?

The idea of this play is artificial. One of our theaters approached me, they asked me to write a play “about the problems of youth”, and preferably let it be drugs. I began to study the material, talked a lot with friends, learned some stories, and began to write. But the more I studied it, the more I became convinced that I didn't want to write about it. Because the topic of drugs in general will not surprise anyone anywhere. And in principle, drugs are a fairly everyday thing. Young people throw themselves, go to clubs, dance until the morning. Managers on Friday evening can drink wine, smoke grass. Naturally, all this is accompanied by some kind of drama, some inadequate actions of people who are too hooked on this matter. But writing a play and building a banal idea into a cube that this is bad and you can’t do this is somehow boring. The topic began to seem petty and uninteresting to me. So I just walked away from it in the process. But the initial artificiality of the play's conception disturbed me, and at some point, exactly in the middle, I simply stopped and put it on the shelf. I returned to it only six months later and completed it in two nights.

And in principle, drugs are a fairly everyday thing. Young people throw themselves, go to clubs, dance until the morning. Managers on Friday evening can drink wine, smoke grass. Naturally, all this is accompanied by some kind of drama, some inadequate actions of people who are too hooked on this matter. But writing a play and building a banal idea into a cube that this is bad and you can’t do this is somehow boring. The topic began to seem petty and uninteresting to me. So I just walked away from it in the process. But the initial artificiality of the play's conception disturbed me, and at some point, exactly in the middle, I simply stopped and put it on the shelf. I returned to it only six months later and completed it in two nights.

Did you find any engine that helped rethink everything?

I would like to say that yes, but in fact, that theater arose that said: “What is there with this play?” I replied that it was not ready yet, they said that they would like to see it. And I like to arrange such torment for myself, so I decided to finish it in two nights. True, nothing happened with the theater anyway. But I did get a play.

And I like to arrange such torment for myself, so I decided to finish it in two nights. True, nothing happened with the theater anyway. But I did get a play.

Did you also have plays in Russian before?

I write in Russian, 95% of my texts are in Russian.

However, little is known about you in the Russian-speaking space. Tell us about yourself, why did you decide to study drama? Do you do it professionally? What were you doing before?

I am a professional writer of plays, scripts and prose. For a long time I worked in the banking sector, then in the private sector, selling oil and gas equipment - in general, I had everything you wanted. For the past two years, I've been free-flying and don't want to go back to office life.

How was the transition from office stability to creative freelance uncertainty?

It was a difficult moment in terms of my own discipline, because this is a completely incomprehensible regime: pauses, then rush jobs, deadlines and round-the-clock work. Even if you don’t write, the brain works, you think about some images, and at five in the morning you can exchange voices with the director, because you don’t sleep, and, it turns out, he doesn’t sleep either.

Even if you don’t write, the brain works, you think about some images, and at five in the morning you can exchange voices with the director, because you don’t sleep, and, it turns out, he doesn’t sleep either.

What didn't suit you in the profitable oil and gas industry so much that you switched to literature?

It always went somehow in parallel. But when there is a main work, it naturally eats up a lot of time, and all the same, literature turns out to be a side activity. But all these years I have been working on myself, and I like it, I want to do it, and I think I can do it. Therefore, exchanging for something parallel seems to be wrong. If you are doing something, you have to do it fully. And when they ask me if this is a hobby for me or what, no, it is a job, often dreary and exhausting.

What did your experience as an author in the Badenweiler jury give you?

Good question, because any author should read a lot of modern plays, but in the turmoil we skip a lot of things or read only our friends and acquaintances. And while working on the jury, I read about 50 plays, and it was interesting. They are all different in format, presentation, and subject matter. Both play readings and play readings always provide material to try something new for yourself. There are no borders, and even today's fringe program confirms this once again. Anything can serve as dramatic material, and reading other people's plays is energizing, so it was a good experience.

And while working on the jury, I read about 50 plays, and it was interesting. They are all different in format, presentation, and subject matter. Both play readings and play readings always provide material to try something new for yourself. There are no borders, and even today's fringe program confirms this once again. Anything can serve as dramatic material, and reading other people's plays is energizing, so it was a good experience.

Would you like to jury more?

There is also a lot of responsibility here, because everything is subjective, and there are plays that you paid attention to, but in the end they do not qualify for shorts, but qualify for shorts in some other competition. Or something passes that you didn’t like at all, didn’t touch - but it is quite considered successful and hurts someone emotionally. There is always a danger here that you will miss something, not pay attention - you need to be painstaking and reverent about this, because every author is waiting for some results. Everyone wants their text to attract attention, find a response in the souls of readers, so it seems to me that readers and the jury should still be more theater scholars and theater critics.

Everyone wants their text to attract attention, find a response in the souls of readers, so it seems to me that readers and the jury should still be more theater scholars and theater critics.

Ismail, maybe this is a distorted view, but from Moscow it seems that Azerbaijan is not the most theatrical country, and Baku is not the most theatrical city. What is it like for you as a modern playwright to live in these conditions? Is the Muslim tradition superimposed or is everything the same as, for example, in Moscow, Minsk, Kyiv?

Muslim tradition does not impose anything, because, firstly, Azerbaijan is a secular state. Secondly, we have a long theatrical tradition, and there is a theater, it exists, but there are few modern plays in it. There are few plays that speak to young people and middle-aged people in modern language, reflecting what is happening now. I miss that as a viewer. I don't want to hang labels, because I don't follow all productions. Of course, there are interesting ones, but this problem is actually for everyone. Both in Russia and I once spoke with a playwright from Britain, they also worry that they have Shakespeare everywhere. You have Ostrovsky and Chekhov. It's great that there are classics, but I also want something new. Because even the classics must be staged, probably with some new approach.

Of course, there are interesting ones, but this problem is actually for everyone. Both in Russia and I once spoke with a playwright from Britain, they also worry that they have Shakespeare everywhere. You have Ostrovsky and Chekhov. It's great that there are classics, but I also want something new. Because even the classics must be staged, probably with some new approach.

Do you see yourself as a playwright who is more staged on Russian or Azerbaijani stages?

In an ideal world, I am both there and there. Because I write in Russian, but my plays are being translated into Azerbaijani. Now the translation of "Big in Japan" is being done, and these texts sound quite normal in Azerbaijani as well.

I watched how Russian readers reacted to this play, it was in the press, I read and analyzed it. It seemed to me that Azerbaijan is still a little exotic country for Russia in terms of dramaturgy. Because we don't write many plays here, in any language. And it seemed to me that perhaps this exoticism plays a role, because any festival wants to cover a wide geography and include new countries. But analyzing the press, analyzing how my play got into some selections inside the shortlist, I relaxed a little and decided that no, apparently, this is really a good play.

And it seemed to me that perhaps this exoticism plays a role, because any festival wants to cover a wide geography and include new countries. But analyzing the press, analyzing how my play got into some selections inside the shortlist, I relaxed a little and decided that no, apparently, this is really a good play.

You also work as a film screenwriter. How dynamically is the Azerbaijani cinema developing now and how high is the demand for scripts there?

There is not much demand because we have a film industry in its infancy, perhaps it doesn't even exist. But we are now on a good rise - in the spring, in the summer, several films of our directors went to Cannes, to Venice. Films have an active festival life. And many films were made by directors with little or no budgetary support, on their own enthusiasm. It seems to me that this is a good trend, because if you want to say something, you have to shoot without waiting for financial injections. If you need to say something, you must say it. It's the same with dramaturgy. Often you write plays because you have to write them. The plot sits in you, it twists you, and it needs to be written in order to get some kind of deliverance. There is a therapeutic effect in writing plays, because by revealing the characters, you somehow shift everything onto their shoulders. I suddenly realized that in this play, "Big in Japan", my entire 2019year. At the same time, in all the heroes there is a little bit of me, even if I categorically do not like it.

If you need to say something, you must say it. It's the same with dramaturgy. Often you write plays because you have to write them. The plot sits in you, it twists you, and it needs to be written in order to get some kind of deliverance. There is a therapeutic effect in writing plays, because by revealing the characters, you somehow shift everything onto their shoulders. I suddenly realized that in this play, "Big in Japan", my entire 2019year. At the same time, in all the heroes there is a little bit of me, even if I categorically do not like it.

What do you expect from reading at Lyubimovka, what would you ideally want to get from this event?

I would like to stage in Russia, because there are many cities with theatrical traditions. Any author wants the play to move from the stage of competitions and readings to the stage of a performance. This is what I would like. I feel like I'm writing universal stories. Yes, they happen in Baku, but they are understandable. When I read the reviews in the press about "Big in Japan", I saw that readers felt exactly what was put into it. And this year has shown that all our dramas and sufferings are not unique. The whole world this year was united in its common grief, we all wore these masks and did not wear them the same way. The uniqueness of our grief, our experiences - it does not exist, all people are essentially the same, just someone keeps a distance, and someone likes to hug when they meet.

When I read the reviews in the press about "Big in Japan", I saw that readers felt exactly what was put into it. And this year has shown that all our dramas and sufferings are not unique. The whole world this year was united in its common grief, we all wore these masks and did not wear them the same way. The uniqueness of our grief, our experiences - it does not exist, all people are essentially the same, just someone keeps a distance, and someone likes to hug when they meet.

Has this year fueled your creativity? Would you like to comment on this?

You're talking about the pandemic, right? I would not like to devote a whole text to this, although I wrote a small play, but I do not like it. And I don’t want to procrastinate, analyze it all under a microscope, because we are too much into it now, and some time must pass. But this is already a part of life, and at least it can be a background.

And you know, this year has been and continues to be productive and productive for me and gives me the desire to write something. I wrote the whole quarantine and am writing now, it didn’t affect me in any way, I didn’t have any downtime. Although at the same time many plans collapsed, many projects were frozen, spread over. It's hard and embarrassing, but what to do now.

I wrote the whole quarantine and am writing now, it didn’t affect me in any way, I didn’t have any downtime. Although at the same time many plans collapsed, many projects were frozen, spread over. It's hard and embarrassing, but what to do now.

Yes, and I didn’t manage to come to Lyubimovka. How do you evaluate your experience of remote participation in the festival?

I missed something, but I try to follow the broadcasts. Again, this gives some impetus. I had an idea for one play, and now it has been replaced by another idea, and, listening to the discussions, I was convinced that yes, this is the direction we need to work. That is, I watch, I watch readings and discussions - sometimes they are even more interesting than the plays themselves. All this feeds me as an author. I’m sorry I couldn’t come, but we really tried and discussed with the guys - it’s just that the borders are still closed. I have heard a lot about the atmosphere that reigns at Lyubimovka, and, of course, I want to be a part of it, because Lyubimovka gives the feeling that everything makes sense, and Japan still exists.

Ismail, share your impressions of reading your play.

I liked it, everything was good. Of the artists, I especially liked Ksenia Chigina, she read organically. Once again I was convinced that this is a universal story and relevant for the entire post-Soviet space. As for the conversations that took place after the reading about national stereotypes, I think this should be avoided. This topic has been raised in other discussions as well. It seems to me that there are such stereotypes in Russia itself, since it is a multinational country, and life in different regions is not always the same. Probably, it is better to move away from national stereotypes and not to perceive the heroes exclusively as representatives of some people or ethnic group. It is not interesting for me as an author to reduce everything to mentality. I will have a Russian hero in my next play, if I give him a balalaika and a tame bear, it will be ridiculous. In fact, all of us living in the space of the "Soviet Union" experiment continue to reap the benefits, even those generations that did not catch it.