Ptsd stories abuse

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Sexual Abuse: A Survivor's Story - Symptoms

by Anne Windermere Patient Advocate

My palms are sweating, my heart is beginning to pound, and I am already near tears.

I have just written my first sentence and I am already having an emotionally difficult time in writing this post.

I feel the subject is so important that I am willing to do this in hopes that I will help someone else who has been through this.

This isn't some academic research article.

I am writing this as a survivor of childhood sexual abuse.

Caution:

This post may contain content which is an emotional trigger for others who suffer from

PTSD and who have endured sexual abuse.

So do proceed with caution and it may be good to have someone on hand you can talk to if you find yourself dealing with overwhelming emotions.

I am fourty-four years old and my abuse took place when I was five years old.

Although it has been more than several decades since this abuse took place, I still re-live the fear and terror of that time.

I can remember details surrounding the abuse and my abuser with sparkling clarity.

But I still cannot remember the actual traumatic events after all this time.

I am finding that this gap in memory is not so uncommon and actually is part of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

My father had just died when I was four.

Shortly after my father's death a friend of my father came to visit my mother and me on a frequent basis.

This man would bring me expensive presents including a huge dollhouse with real lights.

He always had gum and candy to give to me as well.

He never came to our house without something to give to me.

My mother in her grief and distraction allowed this "friend" to babysit me.

I have a memory of sitting on this man's lap and him chiding me that I wasn't my mother's little girl anymore, but his.

And that is as far as the vision unfolds before my fear kicks in and my memories go no further.

My memories pick up when I am talking to my mother and I am repeating words I have no understanding of their meaning.

My mother looks at me in disgust and then panic.

She wants to know where I have heard such words before.

I tell her that our friend has told them to me.

It is then that I am whisked away to the doctor.

I remember feeling confused and frightened during the examination.

An overwhelming sense of shame comes over me as the doctor speaks privately to my mother.

I don't understand why at the time but I feel dirty and bad as though I have done something terribly wrong.

The next memory I have is my mother bringing me to a courtroom. In my disjointed memory, I see him.

He is sitting with this back to me.

Somehow aware of my presence, he slowly turns his head towards me.

He smiles.

And I feel pure fear.

Although it was the last time I physically saw this man, I continued to see him in flashbacks and nightmares many years later.

As a matter of fact, I can still see him now.

My mother's reaction was extreme over protectiveness based in fear and paranoia.

Whenever there was a knock at the door she would hide me in a closet because it could be the "bad man."

Over time I began to startle whenever someone came to the door or even when the phone rang.

In my short lived life the bogeyman was kept real and alive.

I developed phobias, had nightmares, and felt anxiety and fear every day of my young life.

I hate this man for what he did to me and for what he took from me. He robbed me of my innocence and a childhood free

from fear.

The human spirit is capable of unfathomable resilience.

My childhood was filled with both physical and emotional trauma and yet here I am today to tell my tale.

If I give anything to you today my fondest wish is to impart hope.

People and especially children live through all sorts of unimaginable things.

And many survive.

Survival and suffering seem to go hand in hand.

Are we stronger for it?

Perhaps.

But I would gladly give up this strength for memories which don't involve fear.

Even today, peace of mind is difficult to achieve.

But it is not impossible.

Life goes on and we must roll along with it.

**How many people experience sexual abuse?

**

In an article by J. Douglas Bremner, M.D. entitled, "The Invisible Epidemic:

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Memory, and the Brain"

the author cites a statistic of

sexual abuse as a cause for PTSD:

"....a prime cause of PTSD is childhood sexual abuse. About 16% of American women (about 40 million) are sexually abused (including rape, attempted rape, or other form of molestation) before they reach their 18th birthday."

And I have a feeling that this estimate is a low one.

Many cases of sexual abuse go unreported.

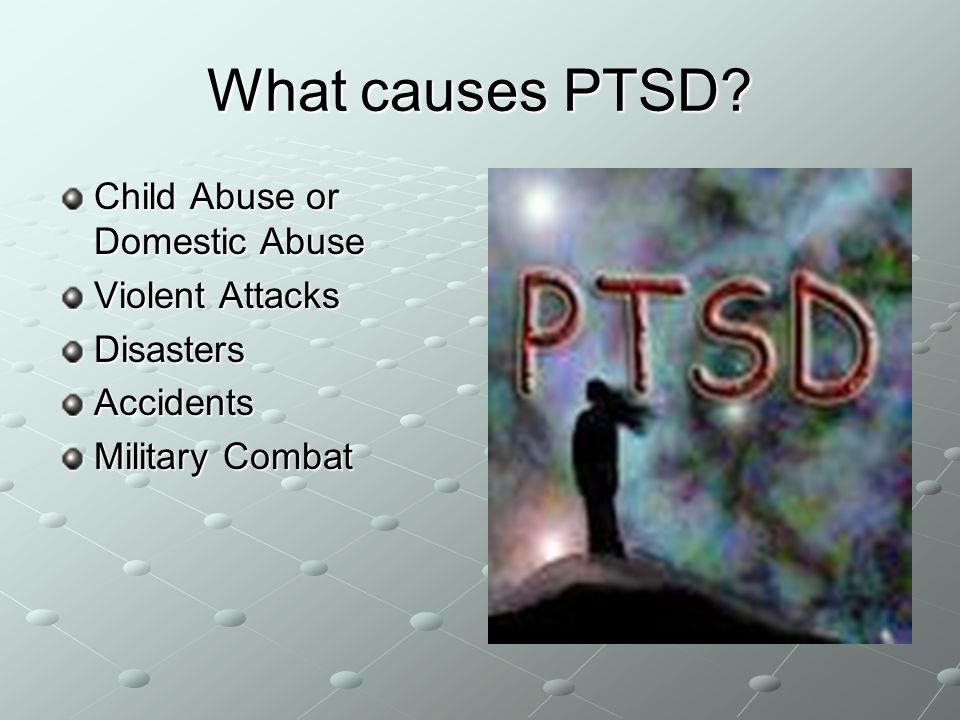

How can sexual abuse lead to Post-traumatic Stress Disorder?

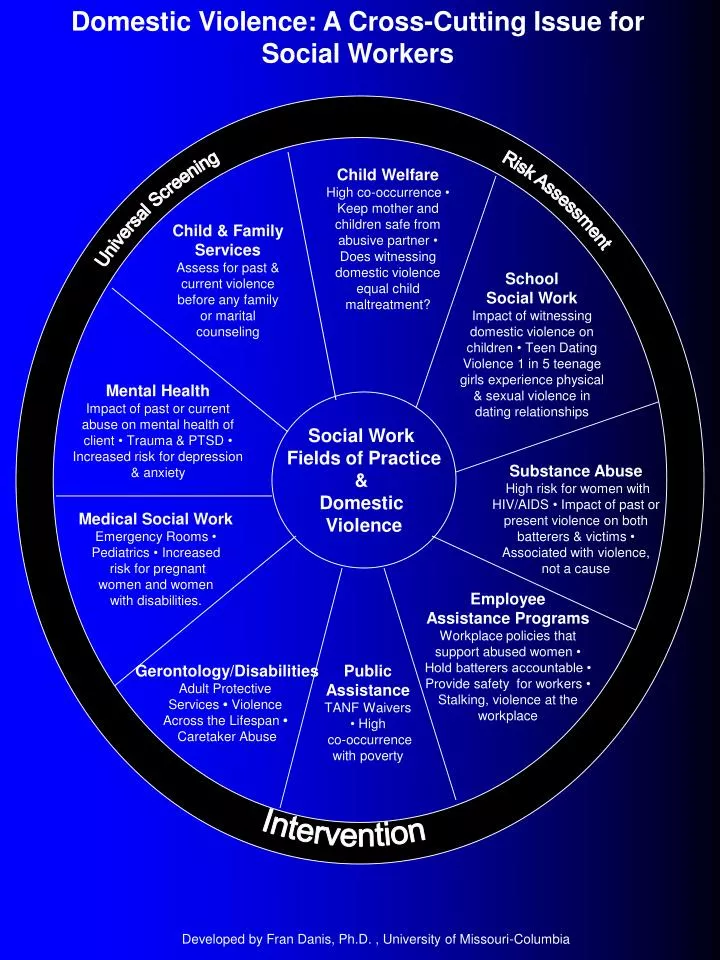

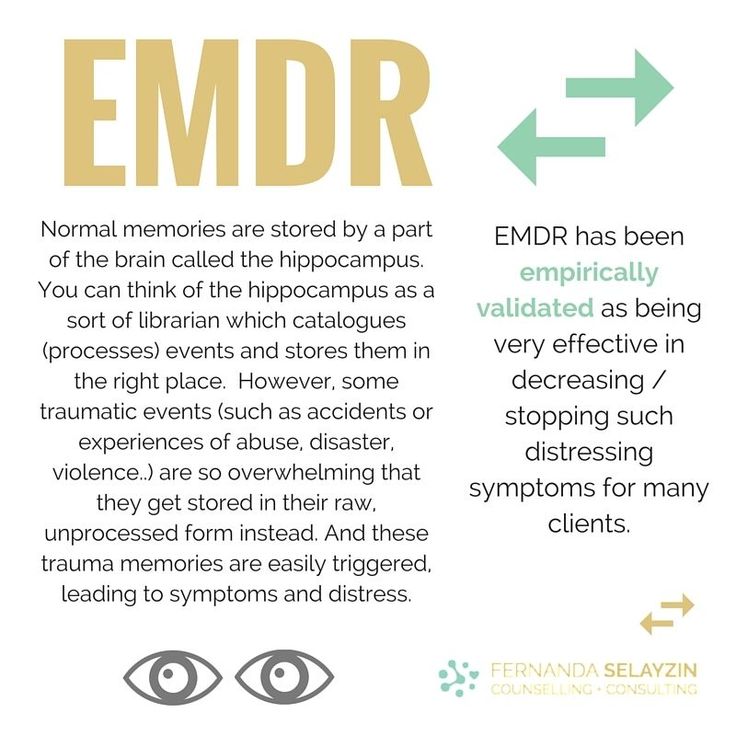

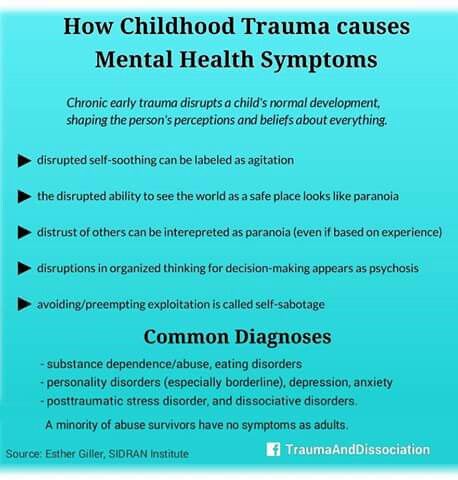

Sometimes we experience things which are so traumatic and stressful that physical changes to our brain can take place.

According to the literature, PTSD sufferers can also suffer from impairments to the hippocampus which is important for learning and memory.

It can also affect the medial prefrontal cortex which regulates our emotional reaction to both fear and stress.

PTSD is not just a psychological thing.

It also has a physical basis.

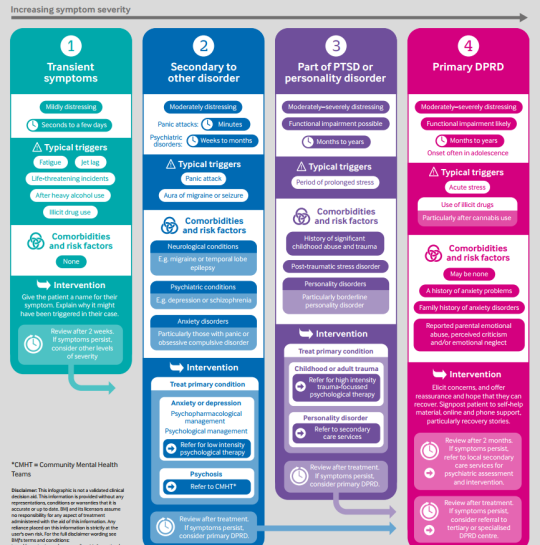

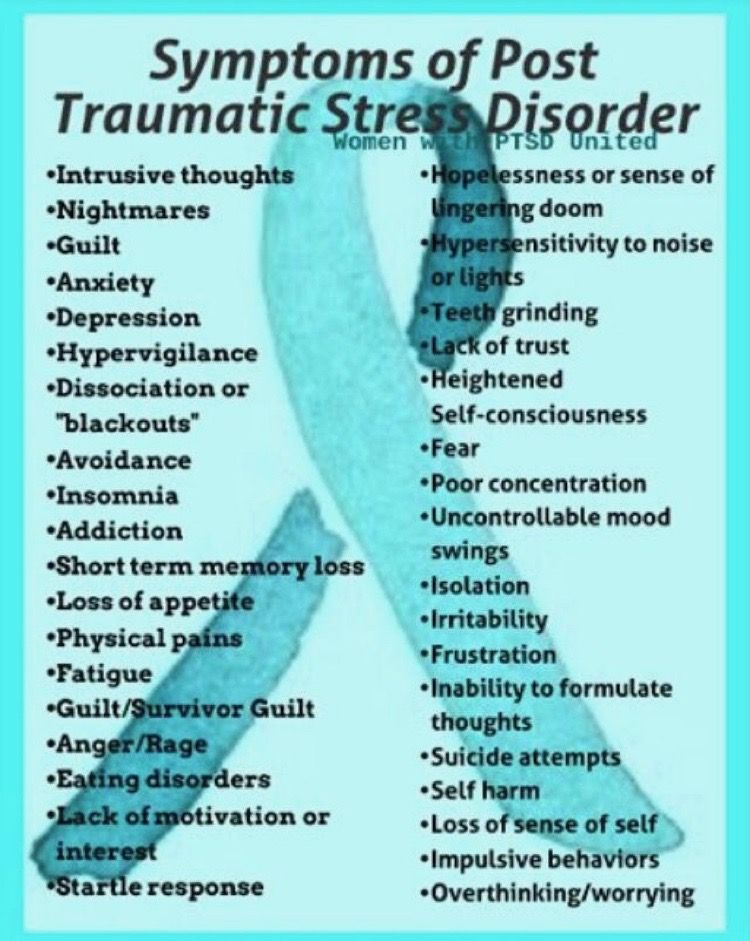

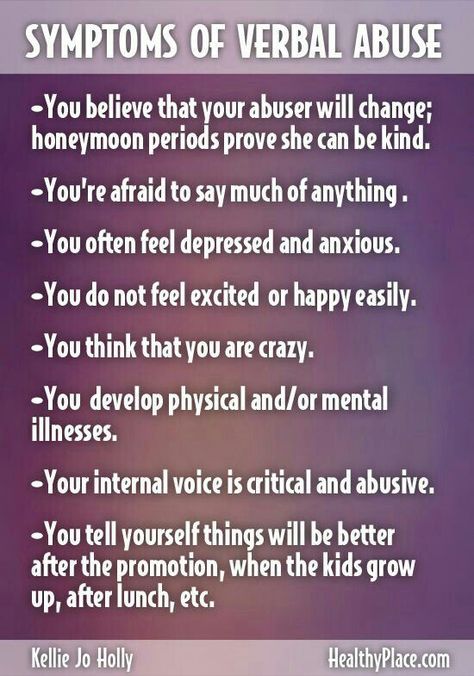

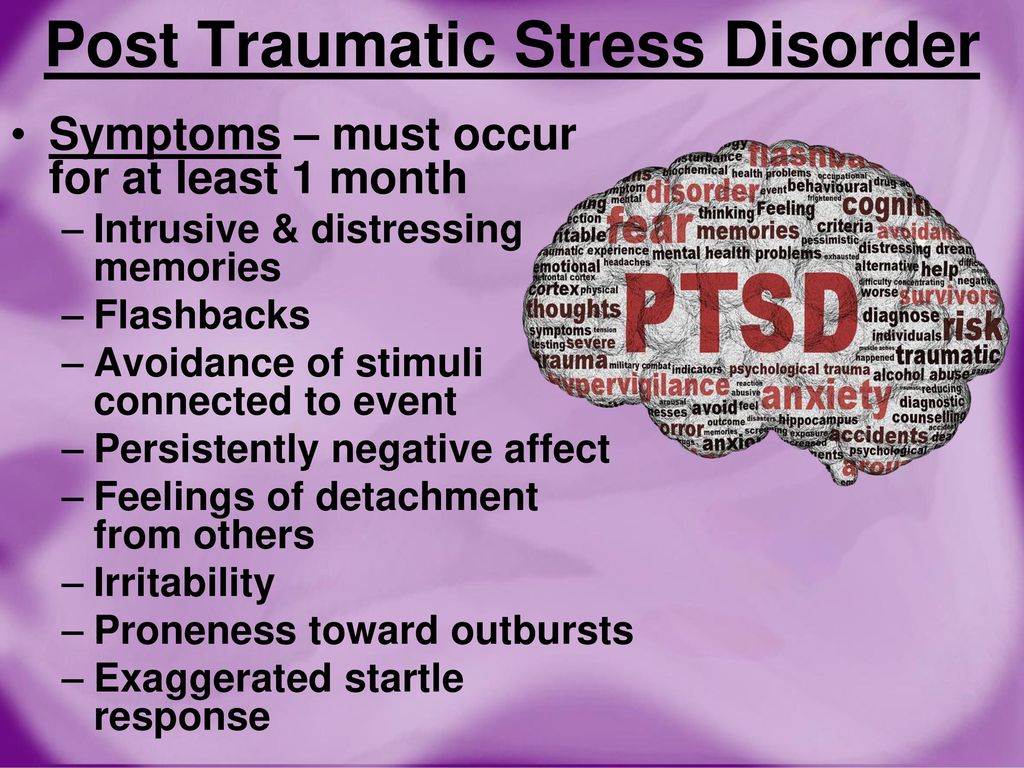

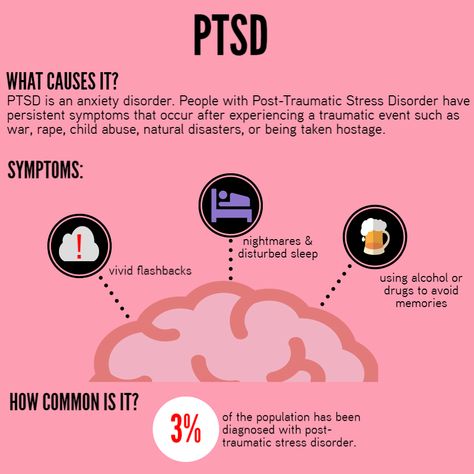

What are some of the signs and symptoms of PTSD?

According to Help Guide.org

some of the symptoms may include:

Nightmares

Flashbacks of the event or the times surrounding the event as though one were re-living it.

Physical manifestations of the flight/fright response such as sweating, increased heart rate, hyperventilation, or nausea in reaction to any reminder of the event.

Feelings of great distress and depression.

Intrusive memories which you seemingly cannot control.

Failure to recall important details of the traumatic event.

Heightened startle responses.

Great anxiety and fear when discussing the traumatic event.

Sleep problems

A feeling of emotional numbness or inappropriate affect to talking about the trauma.

Difficulties with memory and concentration.

What can be done to help you get through this?

I cannot stress this enough but finding a skilled therapist or counselor is one of the best things you can do.

You don't need to go through this alone.

I found a wonderful therapist in my early twenties to help me.

It was a difficult and painful process but I can honestly say that therapy does help with this.

There are also support groups for PTSD as well as sexual abuse where you can talk with others who have been through similar experiences. You are far from alone in this. There are many others who share your pain and have survived.

Here are some further resources :** The National Institute of Mental Health has an index of articles about Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder that you may find here.

** If you need to find a therapist you can use the National Mental Health Services Locator The Anxiety Disorders Association omerica **may also be a way to find a therapist skilled in handling both sexual abuse and PTSD

ou may also find information and assistance from the

Sidran Institute: Traumatic Stress Education and Advocacy

**

Meet Our Writer

Anne Windermere

These articles were written by a longtime HealthCentral community member who shared valuable insights from her experience living with multiple chronic health conditions. She used the pen name "Merely Me."

My Story: Sexual Abuse & PTSD. Content warning: sex, rape, mental… | by V Wegman | The Particle

Content warning: sex, rape, mental health crises

On August 23, 2017, I saw a gynecologist for the first time. I was having pain with sex, and it was taking a toll on my long-term relationship. It had been like this for two years but I decided it was finally time to get answers.

I wasn’t nervous walking into the examination room. I wasn’t even nervous as I laid on the table, awaiting the cold touch of the speculum. I knew pain was coming. I knew what that burn felt like. I no longer feared it. As my vagina screamed in agony, I felt numb.

The doctor asked if I recalled any sexual trauma — well, once I fell on top of a ledge in a playpen, but that wouldn’t have caused this lasting damage. She asked if I had a history of anxiety or panic attacks — yes, I did. I felt nothing as she gently told me something I had never considered: my symptoms were a textbook-case of repeated childhood sexual trauma.

I don’t remember how I got back to my dorm. Nor do I remember my girlfriend coming over to talk about the appointment. What I do remember is sitting on my bed, girlfriend standing next to me, and calling my mom to tell her what I had just been told. Mom asked me the same thing the gynecologist had — did I have any memories of sexual abuse? No, I didn’t. Regardless, this was the most-likely cause of the pain I had always known. From bicycle seats to tampons, I always had unbearable pain with contact. Mom said she knew of only one man who had repeated access to me and the disregard for others to be capable of such abuse. I agreed, he was the only suspect.

Regardless, this was the most-likely cause of the pain I had always known. From bicycle seats to tampons, I always had unbearable pain with contact. Mom said she knew of only one man who had repeated access to me and the disregard for others to be capable of such abuse. I agreed, he was the only suspect.

I have debated for several months whether to out the rapist publicly. As you will see in the aftermath following August 23, 2017, there is currently no doubt that he is guilty.

I will simply name him The Rapist in this story, not to protect him but to protect myself. I have not seen or spoken to The Rapist since 2010. He does not know where I live, I do not know where he is. Regardless, I am afraid of him and the backlash that would ensue if I were to name The Rapist. I am publishing this account in order to relieve myself of its burden and assure survivors of rape that they are not alone, we will heal.

Photo by Joel Naren on UnsplashI spiraled into a suicidal hellhole over the weeks that followed. I was too toxic for those around me, and lost several friends including my girlfriend. There was no light left in me. I completely withdrew from society and had to drop a class I would have loved. I spent weeks in my dorm alone, hardly eating as anxiety overcame me. I committed self-harm. I sat on the high-rise window ledge night after night, trying to muster the courage to end it. I could not live with myself — a broken husk of a person; a former sex doll for The Rapist’s sick pleasure.

I was too toxic for those around me, and lost several friends including my girlfriend. There was no light left in me. I completely withdrew from society and had to drop a class I would have loved. I spent weeks in my dorm alone, hardly eating as anxiety overcame me. I committed self-harm. I sat on the high-rise window ledge night after night, trying to muster the courage to end it. I could not live with myself — a broken husk of a person; a former sex doll for The Rapist’s sick pleasure.

I made it through that semester with enough help to keep my enrollment in-tact. During Winter Break 2017, the first memories came flooding back.

The question of whether events can be consciously forgotten and then remembered later in life is a hotly-contested issue in psychology. It is wholly unethical to attempt such a phenomenon in a controlled setting, and thus is practically impossible to prove. The American Psychological Association, however, currently supports the validity of dissociative amnesia. It is rare, but real. I am baffled by it happening in my own mind. In fact most people who claim to have flashbacks of events they had not previously been aware of are recalling childhood abuse. It is far more common to remember all or some of the abuse, though I am one of the survivors who dissociated during the trauma and has since recovered memories.

It is rare, but real. I am baffled by it happening in my own mind. In fact most people who claim to have flashbacks of events they had not previously been aware of are recalling childhood abuse. It is far more common to remember all or some of the abuse, though I am one of the survivors who dissociated during the trauma and has since recovered memories.

I have recovered countless memories since December 2017. I desperately do not want to believe in the truth of what these memories portray. Of course, I still have a touch of disbelief in my own flashbacks, but the evidence is undeniable. I sought examinations from three other gynecologists, including EMGs. I have been evaluated over and again by four mental health professionals of varying expertise. All concurred with the reality of the trauma.

Each time I recover a memory, it is devastating. I feel so disgusting in my own skin — a penetrating shame and repulsion that no shower can scrub off. I remembered one just last week that wrecked my psyche. The memory comes from a trigger. This time it was a stuffed cow The Rapist had gifted to me. One time it was the smell of seaweed. Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearing was particularly difficult. From small things to national events, anything could shock my conscious into a flashback.

The memory comes from a trigger. This time it was a stuffed cow The Rapist had gifted to me. One time it was the smell of seaweed. Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearing was particularly difficult. From small things to national events, anything could shock my conscious into a flashback.

Flashbacks hit me like I have suddenly entered a dream. They are inescapable, oddly hazy in detail but the sensations are clear. The pain is palpable. New ones send me into a fog that lasts for days. I have to talk them out or they haunt me for hours. I imagine it feels somewhat like a bad trip from hallucinogenic drugs.

Repeated sexual abuse accounts for most of my mental health issues. While I have a family history of depression and panic attacks, my attacks have different triggers than my relatives’. I have more severe generalized anxiety, and acute phobias that have limited my functionality throughout my life. I even had to quit my third NASA internship because the burden of PTSD got so intense.

I resent The Rapist and his enablers with varying ferocity. Some days I truly want to kill him. Others, I hardly think about him. I have lost so many friends and some family because of what he did to me and how I reacted to it. I lost my dream job because of him. I lost my first healthy relationship. I lost my autonomy.

But I have gained immeasurable strength. I gained a new understanding of trauma, my own mind, and the ramifications of rape. I gained a community of survivors who listen to my gripes and validate my shifting moods. I gained the knowledge that my parents and sisters will love and support me through my lowest moments. I gained the confidence to write about something so personal and intimate. I gained a new sense of self.

I used to blame myself for the disruption this has caused. I thought if I had chosen not to come forward, no one else would have to get hurt. The Rapist was out of our lives anyway, so I could take one for the team and swallow this torture whole. It was only through years of therapy and extensive support from my remaining loved ones that I learned these beliefs are absolutely false. I did the right thing, continuing to talk about the trauma in no uncertain terms. The pain we all feel is not my fault, but The Rapist’s.

It was only through years of therapy and extensive support from my remaining loved ones that I learned these beliefs are absolutely false. I did the right thing, continuing to talk about the trauma in no uncertain terms. The pain we all feel is not my fault, but The Rapist’s.

Sexual abuse is life-altering but we find ways to come back stronger than ever before. Trauma changed my life in unexpected ways, not all of them bad. I hope at least one person can take my testimony and feel empowered by it. You do not have to do this alone.

The USA hotline for sexual assault victims is 1–800–656–4673; some mental health crises options can be found here. The Trevor Project helped me in some of my toughest moments.

90,000 Life after traumatic events. Post-traumatic growth // Psychological newspaper People do grow after traumatic events, but they do not always accurately remember and describe the process and nature of the change.

Stephen Joseph

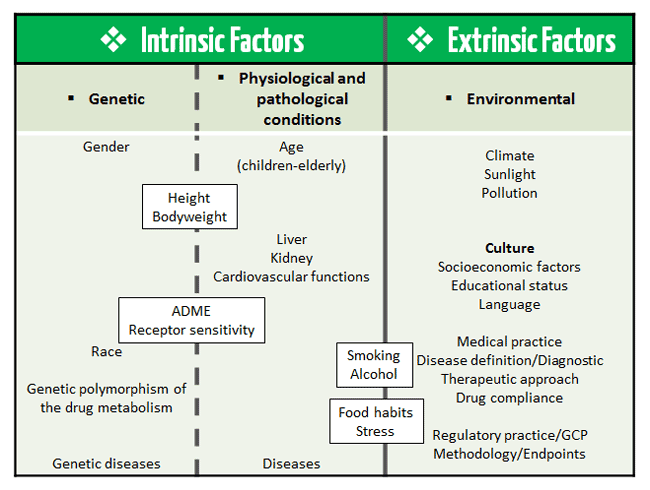

Modern man often faces difficulties in interpersonal relationships, social and economic crises in society, regional conflicts, natural disasters. Such events can be quite traumatic for people. The degree of impact of trauma on a person depends on the subjective assessment of the event, on the perception of the event as a threat to life and health. Psychic trauma never passes without a trace, but it can not only destroy a person.

People who talk about their “transformation” usually talk about how their outlook on life and their priorities have changed, that they began to evaluate themselves and their capabilities differently, that closeness and love for others has increased. and relationships with other people have reached a new, deeper level. To describe such changes, the phrase “post-traumatic growth” is most suitable [1c, p.103].

Trauma prompts us to reflect on our values, motives, priorities. As a result, we often abandon the old views on life and create new values, motives and priorities. In this sense, the idea of growth as a result of trauma is close to the Buddhist idea that those who have experienced adversity stand stronger on their feet in the face of new hardships, and suffering teaches useful lessons for life [1, p.165]. Experiencing a traumatic event often makes people stronger and wiser. A vivid example of this is the psychologist from the concentration camp - Viktor Frankl.

In this sense, the idea of growth as a result of trauma is close to the Buddhist idea that those who have experienced adversity stand stronger on their feet in the face of new hardships, and suffering teaches useful lessons for life [1, p.165]. Experiencing a traumatic event often makes people stronger and wiser. A vivid example of this is the psychologist from the concentration camp - Viktor Frankl.

Viktor Frankl, one of the whole family, managed to survive in inhuman circumstances and cope with extreme distress [1, p.33]. Frankl believed that those who could find the meaning of life, despite all the hell that was going on around, were more likely to survive. The famous writer and psychotherapist Irvin Yalom wrote about how the meaning of life grows out of the suffering caused by life-threatening illnesses [1, p.35]. Life is filled with meaning and people have a goal for which it is worth living. The meaning of life in difficult times can also be found in everyday things, for example, the meaning can be seen in the beautiful sky, in the densely green grass, in the trees, the meaning is in natural beauty and contemplation, the meaning is that you can rejoice and admire nature at least for a minute.

After trauma, people change their worldview. Values change - small everyday joys become more important than expensive things or high-profile victories [1, p. 107-108].

Some bow in the face of adversity but recover quickly (Smith, Dalen, Wiggins et al, 2008) [op. according to 1, p. 104] and this resembles a viable tree branch, which, under the influence of a strong wind, bends, but does not break. Then it resumes its growth and development again.

Researcher S. Joseph drew attention to the fact that post-traumatic stress often becomes the engine of post-traumatic changes [1, p.103]. A certain degree of post-traumatic stress, apparently, contributes to post-traumatic stress growth, however, if the level of post-traumatic stress goes off scale, the likelihood of growth drops [1, p.128], then we can talk about symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

However, people may suffer, but their self-esteem, outlook on life, priorities, plans for the future and lifestyle change under the influence of the experience for the better (Lepore, Revenson, 2006) [cit. according to 1, p.105].

according to 1, p.105].

People look at life differently, setting priorities. They begin to spend more time with loved ones, appreciate life, every moment, sometimes they live every day as if it were their last, and this makes one feel the fullness of life.

According to Waite: "suffering becomes a creative and positive force" [1, p.186]. Many begin to write poetry or draw pictures, describe their experiences in works of art.

Everyone experiences and overcomes trauma differently. Someone resorts to destructive methods (alcohol abuse, gambling, unreasonable spending of money, driving around the city in a car racing at high speed). The methods may be different and do not always lead to growth and benefits for life.

Scientists have identified strategies for coping with trauma that lead to post-traumatic growth:

- By telling stories, a person gets the opportunity to grow. Stories are the way to overcome [1, p. 189-190].

- Turning to others for support is an important strategy for overcoming trauma [1, p.

175]. Speaking through the experience in the company of a person who is ready to provide support, we transform a severe traumatic experience into a post-traumatic development [1, p. 174].

175]. Speaking through the experience in the company of a person who is ready to provide support, we transform a severe traumatic experience into a post-traumatic development [1, p. 174]. - Religion can often help a person. Religious people after trauma may feel that their faith has grown stronger. Religion gives people a sense of meaningfulness [1, c.176 -177].

- An active role in the process of creating one's own life contributes to post-traumatic growth [1, p.197].

- Taking responsibility for your life helps you overcome adversity. It is important to take responsibility for your life (for the competent use of coping strategies).

It is worth noting that for survivors of adversity, the American Psychological Association has developed educational materials on the best ways to overcome the incident:

- build relationships with others,

- do not assume that the crisis is insurmountable,

- accept the fact that change is part of life,

- go to your goal,

- make decisions and implement them,

- strive to learn new things about yourself,

- develop positive self-esteem,

- learn from past experience,

- keep hope,

- take care of yourself [1, c.

204-205].

204-205].

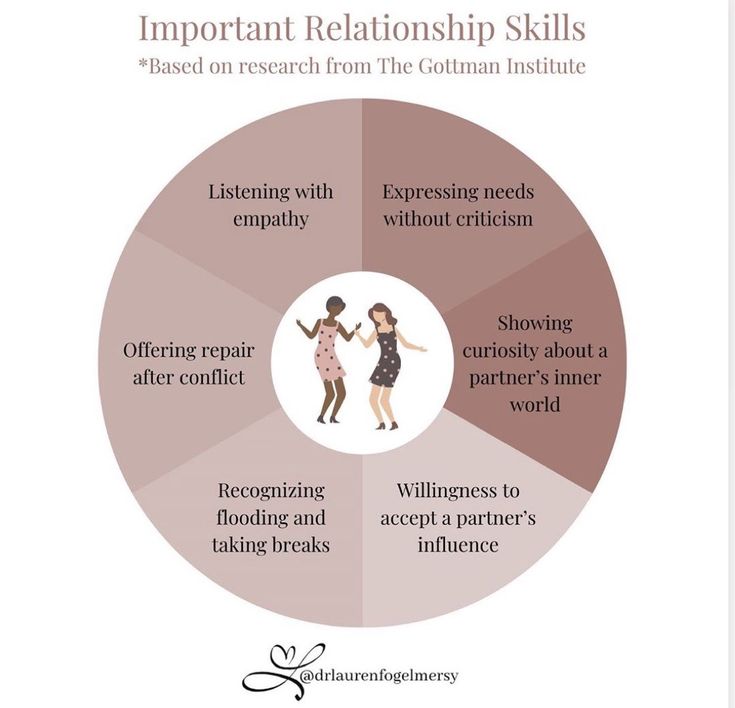

In addition, the role of human relationships has a healing effect on the trauma survivor.

In matters of post-traumatic growth, the relationship itself is already an important means of healing [1c. 205]. A traumatized person always has a need for care and belonging with someone. Protective relationships contribute to human vitality.

It is worth noting that self-compassion can surprisingly increase well-being [1, p.217].

Research shows that when a person is struggling, they need to:

- face reality, not deny it,

- to accept the fact that trouble has occurred, rather than happily succumb to it,

- take responsibility for your future life, and not blame yourself for your unfortunate fate [1, c.282].

Thus, in addition to destructive ways of coping with trauma, there are ways that have a beneficial effect on a person, leading to post-traumatic growth and development in life. You can always use the proposed strategies in everyday life. They help to cope not only with global catastrophes, but also with everyday troubles.

You can always use the proposed strategies in everyday life. They help to cope not only with global catastrophes, but also with everyday troubles.

Post-traumatic growth contributes to a change in life in a positive direction, but not all people are "given to grow and transform." The choice of strategies of behavior in a crisis for each person depends on his values, meanings, upbringing, level of intelligence. Already now we can say that post-traumatic growth is what a person should strive for, being in adverse environmental conditions. The very fact that people can remember post-traumatic growth, that it takes place in situations of trauma, can lead to a significant positive change in life. Yes, it’s not always possible to think about growth and development during a period of adversity, but empathic listening, a caring attitude from a psychologist, as well as a reminder of the existence of post-traumatic growth can improve a person’s condition during a period of psychological trauma.

1. Joseph S. What doesn't kill us. The New Psychology of Post-Traumatic Growth / Steven Joseph (translated from English by I. Yushchenko). - M.: Career Press, 2015. - 352 p.

2. Lawrence G. Calhoun, Richard G. Tedeschi The Handbook of Posttraumatic Growth: Research and Practice, 2006.

Post-traumatic stress disorder at the center of international research: a review of the article

partners Keywords / keywords: Antidepressants, Velaxin, Virtual reality, Depression, Cognitive-behavioral therapy, Psychiatry, Neuropsychiatry, PTSR, Stress, Anxiety , Anxiety disorders

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been the focus of attention of doctors and scientists for more than a century. In a review of the article by Anna Vladimirovna Vasilyeva, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Chief Researcher of the Department for the Treatment of Borderline Mental Disorders and Psychotherapy, Head of the International Department of the Federal State Budgetary Institution “N. N. V.M. Bekhterev” of the Ministry of Health of Russia, Professor of the Department of Psychotherapy, Medical Psychology and Sexology, FSBEI HE “North-Western State Medical University named after I.I. I.I. Mechnikov” of the Ministry of Health of Russia, in the context of the history of the study of PTSD, demographic, pathophysiological and neurophysiological features of this disorder are presented.

N. V.M. Bekhterev” of the Ministry of Health of Russia, Professor of the Department of Psychotherapy, Medical Psychology and Sexology, FSBEI HE “North-Western State Medical University named after I.I. I.I. Mechnikov” of the Ministry of Health of Russia, in the context of the history of the study of PTSD, demographic, pathophysiological and neurophysiological features of this disorder are presented.

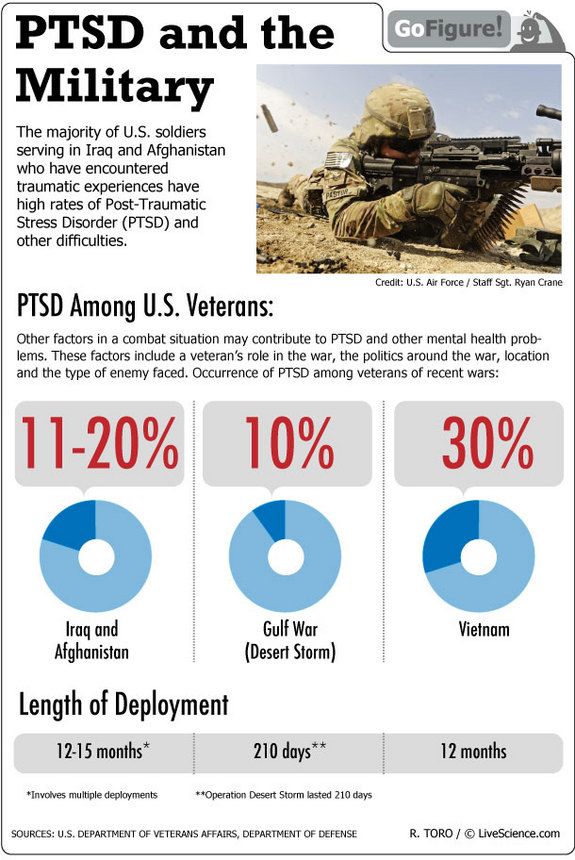

The first description of PTSD symptoms can be found in studies of American soldiers during the American Civil War. It was believed that the observed somatovegetative disorders (including disorders of cardiac activity) are functional in nature and are a consequence of the reaction of recruits to stress. Subsequently, similar cardiovascular symptoms ("irritable heart", "Da Costa's syndrome", "soldier's heart", "old sergeant's heart", "cardiovascular neurosis", "combat fatigue", "combat exhaustion") were repeatedly described in combatants. In domestic science, the assumption about the psychogenic nature of cardiac pathology (cardialgia and palpitations) in combatants was put forward by psychiatrist A. I. Ozeretskovsky. Later, during the Vietnam War, such somatic symptoms were identified as somatovegetative manifestations of a mental disorder, the so-called "Vietnamese" or "post-Vietnamese" syndrome. At 19In the 1970s, DSM-III introduced the term PTSD in the category of anxiety disorders, which was defined as an exogenous mental disorder that occurs after exposure to a powerful stressor, in most cases threatening a person's life or well-being.

I. Ozeretskovsky. Later, during the Vietnam War, such somatic symptoms were identified as somatovegetative manifestations of a mental disorder, the so-called "Vietnamese" or "post-Vietnamese" syndrome. At 19In the 1970s, DSM-III introduced the term PTSD in the category of anxiety disorders, which was defined as an exogenous mental disorder that occurs after exposure to a powerful stressor, in most cases threatening a person's life or well-being.

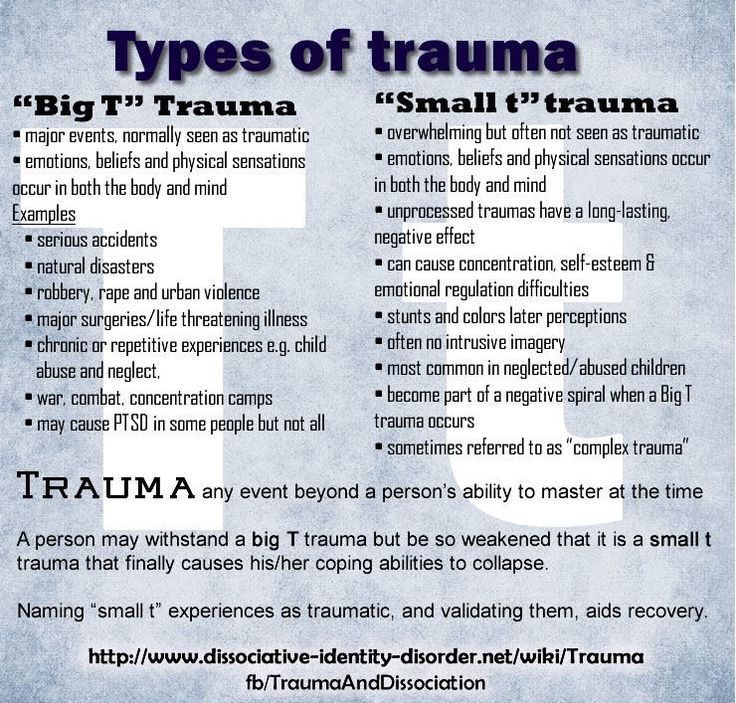

A traumatic event is understood as death, serious injury or threat of death, as well as the range of experiences of an individual in response to an event of pronounced negative affect. The degree of trauma of a stressful event is determined by its suddenness, threat to identity and the global nature of the impact, and the patterns of development and manifestations of PTSD do not depend on what specific events caused mental and somatovegetative disorders. The latent period of PTSD manifestation can take up to 6 months from the moment of exposure to the stressor.

Demography and physiology of PTSD

Depending on individual vulnerability and the nature of the stress impact, in 13-50% of people, the reaction to a traumatic impact manifests itself in the form of PTSD. The wide variability of incidence rates is largely determined by the social context: in favorable periods of society, the morbidity of PTSD is 0.5% among men and 1.2% among women. In the pediatric population, on the contrary, boys are more prone to PTSD manifestations.

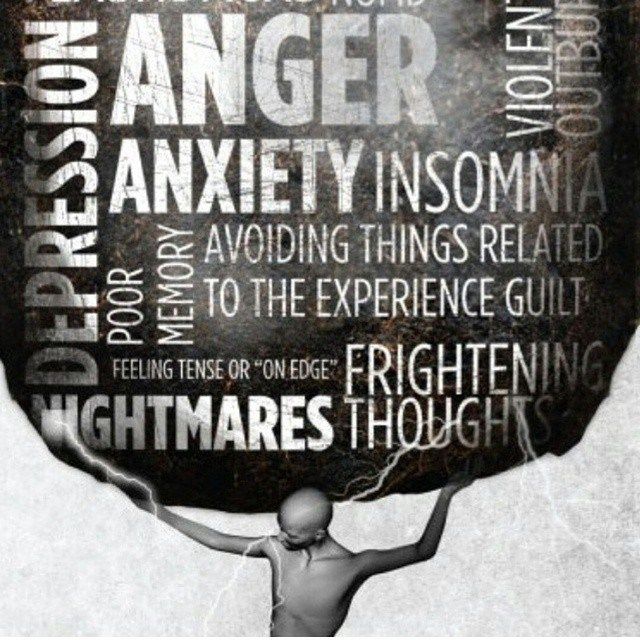

Behavioral manifestations of PTSD demonstrate pronounced gender differences. So, for men, extrapunitive (including with the manifestation of aggression) reactions, irritability and dysphoria are characteristic, while for women - intrapunitive reactions. The latter, in the case of chronicity, often progress in the form of comorbid depressive and other mental disorders (fatalism, pessimism, hypervigilance).

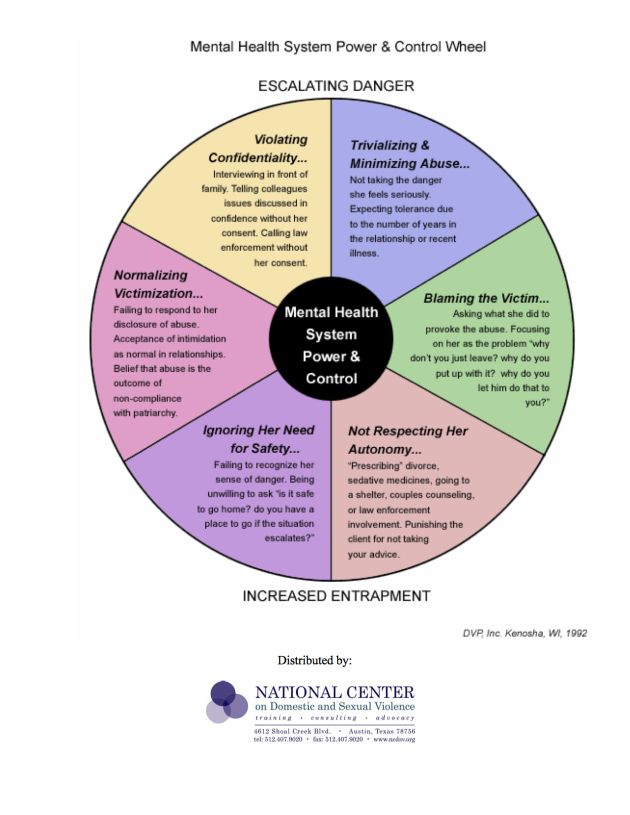

The higher prevalence of PTSD among women can be explained, in particular, by personality traits, such as emotional instability or increased anxiety, and in clinical practice it is critical to correctly assess whether personality changes are a consequence of experiencing severe mental trauma or they preceded the development of the disorder. In some cases, the diagnosis may be consciously or unconsciously used by the patient as a factor in determining their own identity. Trauma-related aggression can become the basis of hypervigilance or be part of a defensive reaction.

PTSD comorbidity

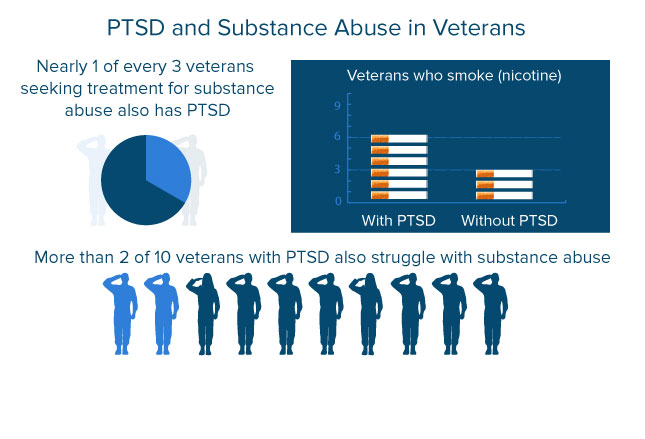

The long course of PTSD is often accompanied by the development or progression of comorbid mental disorders (anxiety and depressive disorders, suicidal behavior, addictions, eating disorders, psychosis and emotional regulation disorders) and somatovegetative disorders (chronic pain, cardiovascular pathology, etc.). Often the result of insufficient awareness of the disease is self-medication, often developing into the abuse of psychoactive substances or taking drugs for other purposes.

Most of the domestic research is devoted to the study of PTSD in cancer patients. Thus, in a 2015 meta-analysis, it was shown that 1-6 months after discharge from the intensive care unit, a quarter of patients reported symptoms of PTSD. For this category of patients, a separate term was introduced - "flashforward", denoting a spontaneous realistic representation of future negative events (for example, one's own death or funeral). Similarly, PTSD has been identified as one of the most commonly reported disorders in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and COVID-19., as well as every fifth patient who survived after hospitalization in the intensive care unit in a life-threatening condition. Among the latter, the manifestation of PTSD varied from 5.8 to 31%. It is noteworthy that, in contrast to the focus on autonomic disorders of the cardiovascular system, which is more characteristic of patients with PTSD, patients who underwent coronavirus infection were focused on the functioning of the respiratory system with the fear of dying from lack of air. The intensity of symptoms in this group of patients correlated with the severity of COVID-19, and the main risk factors were young age, female sex, stay in the intensive care unit, the presence of chronic somatic diseases and metabolic syndrome.

Psychophysiology of PTSD

From the point of view of constructivism, information about trauma exists in active working memory until it is comprehended in accordance with the beliefs and model of the world of the individual. According to Francine Shapiro's neurophysiological model of accelerated processing of information, the cause of PTSD is insufficiently processed information stored in memory during a traumatic event. Influencing the work of the information processing system, emotional trauma is preserved in the form due to traumatic experience, contributing to the formation of intrusive symptoms of post-traumatic syndrome.

In the process of cognitive processing of traumatic experiences, traumatic experiences may alternate with periods of avoidance. The likelihood of a subsequent manifestation of comorbid depressive disorders increases against the background of the progression of emotional dysregulation (eg, emotional numbness) as a form of psychological defense - any strong emotion is perceived as a danger of a return of traumatic experience. In addition, patients may develop anticipatory anhedonia, depersonalization or derealization, excessive physiological arousal, startle reactions, and difficulty concentrating. The impact of a psychotraumatic factor can lead to impaired cognitive processing: the individual's ability to think critically, plan and control the negative effect is impaired.

In addition, patients may develop anticipatory anhedonia, depersonalization or derealization, excessive physiological arousal, startle reactions, and difficulty concentrating. The impact of a psychotraumatic factor can lead to impaired cognitive processing: the individual's ability to think critically, plan and control the negative effect is impaired.

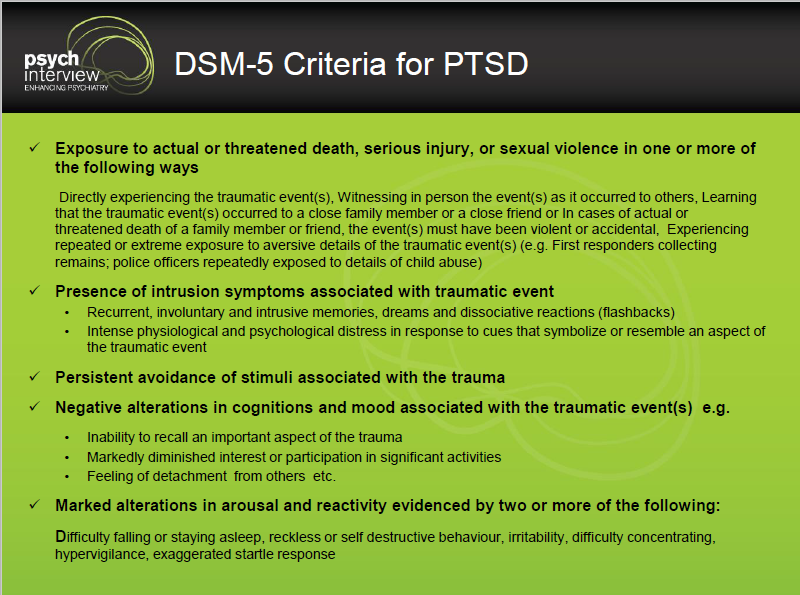

Classification and diagnostic criteria for PTSD

In the ICD-10, PTSD is classified under category F43.1 under Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders (sections F40-F48) and “occurs as a delayed and prolonged reaction to a stressful event or situation of an exceptionally threatening or catastrophic nature, which may cause distress to almost everyone."

From a practical point of view, the symptomatic criteria for PTSD are traditionally divided into three main categories :

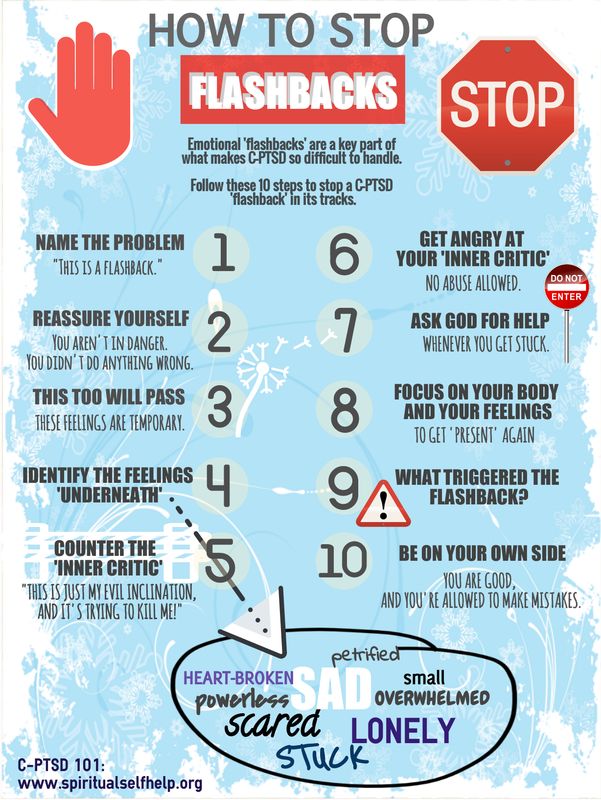

- Intrusions - repetitive experience of a traumatic event in the form of illusions, hallucinations, flashbacks or nightmares, developing through unconscious associative links in response to circumstances that symbolize or resemble traumatic events and cause severe psychological distress.

- Flashbacks - experiencing feelings, emotions, sensations of a situation from the past; in psychiatry, dissociative reverse vision, spontaneous realistic recollection of traumatic events. A variant of the symptom may be invading fearful representations, mental images of an expected future event. In situations that are directly similar or associatively reminiscent of a traumatic one, somatovegetative manifestations of emotional discomfort may progress.

- Recurring nightmares reflecting traumatic experiences.

In the ICD-11, PTSD is included in a separate section "Disorders directly related to stress." An acute reaction to stress is defined as a normal form of response of the human psyche to a strong stressful effect and refers to the section "Factors affecting the state of public health and health care visits." In addition to "adjustment disorders" and "PTSD", additional nosologies are identified, such as "complex PTSD" and "prolonged grief reaction", and specific attachment disorders in children are also included.

According to ICD-11, the diagnosis of PTSD requires the presence of specific trauma-associated symptoms, incl. re-experiencing traumatic experience in the present in the form of intrusions accompanied by intense emotional experiences (panic, fear, anger) and somatovegetative manifestations of affect involving various sensory modalities that persist for several weeks and reduce the quality of life of the patient. In addition, there may be various manifestations of reactions to avoid the possible actualization of traumatic experiences, causing additional anxiety, hypervigilance, increased vigilance, hypervigilance and hyperacusis.

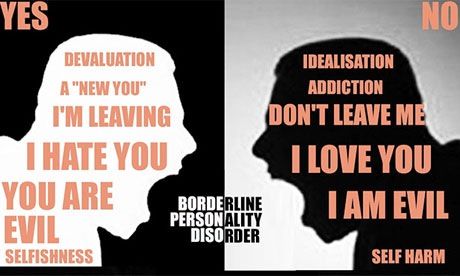

Despite the presence of common symptoms with borderline personality disorder, in particular problems with affective regulation, it is critically important in differential diagnosis to distinguish between these two conditions. So, patients with borderline personality disorder are characterized by an unstable, blurred sense of their own identity, a changeable pattern of interpersonal relationships, as well as obsessive self-harmful and suicidal behavior. Individuals with complex PTSD, in turn, have a negative but stable self-image, followed by affective dysregulation and PTSD symptoms themselves, with consistent avoidance or disconnection, and low levels of impulsivity.

Individuals with complex PTSD, in turn, have a negative but stable self-image, followed by affective dysregulation and PTSD symptoms themselves, with consistent avoidance or disconnection, and low levels of impulsivity.

PTSD and complex PTSD

Complex PTSD replaces the 1992 diagnosis of "chronic personality change due to catastrophe experience", which was previously in the section that coded for acquired personality changes due to a mental or somatic illness or long-term traumatic life circumstances, without taking into account the circumstances of domestic violence and sexual activities in regarding children.

The results of the studies convincingly demonstrate significant differences between complex PTSD and PTSD, both in terms of the qualitative set of symptoms and the characteristics of traumatized patients. Complex PTSD occurs after a long stay in a severe traumatic situation, the consequences of which are extremely difficult or impossible to get rid of, such as captivity, slavery, prolonged stay in the territory of hostilities, domestic physical or sexual violence. In addition, PTSD therapy is not always suitable for patients with complex PTSD. In particular, exposure, as the primary technique for increasing the tolerance of unpleasant images associated with trauma, should be used with caution in complex PTSD due to a pronounced deficit in self-regulatory skills.

In addition, PTSD therapy is not always suitable for patients with complex PTSD. In particular, exposure, as the primary technique for increasing the tolerance of unpleasant images associated with trauma, should be used with caution in complex PTSD due to a pronounced deficit in self-regulatory skills.

Diagnosis requires the presence of the main symptoms of PTSD (continued feeling of threat, re-experiencing the traumatic event in the present, avoidance), as well as disturbances in three main personality domains (affect, identity and relationship system):

- persistent affective regulation problems;

- negative self-attitude;

- difficulties in establishing interpersonal relationships and experiencing feelings of emotional closeness in relation to other people.

Therapy for PTSD

Pharmacotherapy

The results of large reviews demonstrate the low effect of not only psychotherapy, but also pharmacotherapy in the treatment of mental disorders, which indicates the need for a better understanding of their pathophysiology and the development of new approaches to classification and diagnosis. For PTSD, however, moderate effect sizes have been shown for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and pharmacotherapy using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), with the former having a longer and more sustained effect. Effect.

For PTSD, however, moderate effect sizes have been shown for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and pharmacotherapy using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), with the former having a longer and more sustained effect. Effect.

In 2022, the third version of the World Federation of Biological Psychiatry Societies (WFSBP) clinical guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder and PTSD was published. Based on data from randomized clinical trials, experts recommend the SSRI antidepressants paroxetine, sertraline, and fluoxetine, as well as the dual-acting SNRI antidepressant venlafaxine, as first-line drugs for the pharmacotherapy of PTSD. The tricyclic antidepressants amitriptyline and imipramine were identified as second-line drugs due to their higher incidence of side effects, risk of overdose, and lower compliance. The antipsychotics risperidone and quetiapine are suggested as third-line agents due to the high risk of adverse reactions even at low doses.

The α2-noradrenergic agonist clonidine, which is used to relieve withdrawal symptoms from opiate use, is also effective in treating a number of PTSD symptoms, which confirms the hypothesis that they develop as a result of a decrease in the level of endogenous opiates involved in the body's stress-limiting system. For the treatment of nightmares, the administration of the α1-blocker prazosin is recommended.

In the chronic course of the pathology, as first-line drugs, patients are prescribed SSRI antidepressants fluoxetine and sertraline or an SNRI drug venlafaxine in standard therapeutic doses with a course duration of at least a year to prevent relapses.

According to clinical and epidemiological studies and meta-analyses, one of the most effective drugs to date for the treatment of anxiety-depressive spectrum disorders, both in outpatient practice and in hospital, is the antidepressant from the SNRI group venlafaxine.

Venlafaxine belongs to the third generation of thymoanaleptics with a dual mechanism of action. Acting on the three main neurotransmitter systems responsible for affective regulation, the drug has an anti-anxiety and antidepressant effect: when administered at a dose of 150 mg / day. serotonergic predominates, and when the dose is increased to 150-300 mg / day. - noradrenergic and dopaminergic effects, which is an additional advantage in the development of comorbid depressive disorders.

Acting on the three main neurotransmitter systems responsible for affective regulation, the drug has an anti-anxiety and antidepressant effect: when administered at a dose of 150 mg / day. serotonergic predominates, and when the dose is increased to 150-300 mg / day. - noradrenergic and dopaminergic effects, which is an additional advantage in the development of comorbid depressive disorders.

Possessing a pronounced and balanced anxiolytic effect, venlafaxine contributes to the relief of somatovegetative manifestations of anxiety, hypervigilance and anxious experiences. Thymoleptic and stimulant effects reduce the severity of symptoms associated with avoidance reactions, depressive affect, anticipatory anhedonia and fatalism. High selectivity of action ensures good tolerability of the drug.

For the treatment of PTSD, depending on the individual characteristics of the patient and the course of the pathology, venlafaxine is prescribed at a dose of 75-225 mg / day. To avoid withdrawal syndrome, dose reduction is recommended to be done gradually. In order to increase adherence and tolerability of therapy in comorbid patients, monitoring of comorbidities and correction of the dosage regimen and schedule of taking the drug (prescribing prolonged encapsulated forms of 75 mg and 150 mg 1 time / day) are required.

In order to increase adherence and tolerability of therapy in comorbid patients, monitoring of comorbidities and correction of the dosage regimen and schedule of taking the drug (prescribing prolonged encapsulated forms of 75 mg and 150 mg 1 time / day) are required.

The possibilities of secondary prevention of PTSD in individuals with and without symptoms of psychological distress after experiencing a serious traumatic event are unfortunately limited today.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Of the 90,126 non-pharmacological approaches, 90,127 the authors of the recommendations suggest the use of CBT. In particular, one of the most popular CBT techniques is virtual reality exposure therapy ( virtual reality exposure therapy , VRET) or VR therapy, which is also successfully used to treat anxiety, phobic disorders, depression and insomnia.

The method is based on teaching the patient how to work with internal tension through relaxation or cognitive restructuring in conditions of simulating a real environment using computer graphics. "Reconstruction" of a frightening object or situation, i.e. the use of aversive stimuli contributes to desensitization and a change in attitude to the situation.

"Reconstruction" of a frightening object or situation, i.e. the use of aversive stimuli contributes to desensitization and a change in attitude to the situation.

In addition to trauma-focused CBT (TF-CBT), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing ( EMDR ) is gaining popularity. This approach consists in a "confrontation" with a traumatic experience against the background of directed bilateral stimulation (rhythmic eye movements) with a simultaneous figurative representation of a traumatic event.

The EMCG method, although promising, currently has a limited evidence base. It is hypothesized that eye movements or other alternative stimuli activate the information-processing system and restore its balance, probably through the destruction of the stereotypical response, distraction, hypnosis, changes in synaptic potentials, relaxation response, as well as activation of both hemispheres of the brain, causing integrative processing.

Clinical case

A 35-year-old patient complained of severe anxiety, involuntary flashes of vivid memories, in which she relived scenes of a helicopter accident accompanied by panic attacks, dizziness, hot and cold flashes, involuntary muscle twitches, palpitations, feeling short of breath, sleep disturbances with frequent awakenings, superficial, interrupted sleep, decreased performance, difficulty concentrating, loss of former interests, anhedonia. Flashbacks occurred spontaneously or were provoked by the sound of patrol helicopters flying past over the patient's house. Because of the inability to control the intrusions, there was a fear of losing control over one's mental functions; the patient believed that, despite the conclusion of doctors that she had no brain damage, irreversible changes had occurred in her brain.

Flashbacks occurred spontaneously or were provoked by the sound of patrol helicopters flying past over the patient's house. Because of the inability to control the intrusions, there was a fear of losing control over one's mental functions; the patient believed that, despite the conclusion of doctors that she had no brain damage, irreversible changes had occurred in her brain.

The described complaints were formed within 2 months. helicopter accident during the expedition. The patient's common-law husband was seriously injured and was in rehabilitation at the time of the appeal; At the time of referral, the patient was living alone.

Heredity is not burdened with neuropsychiatric diseases, he denies chronic diseases, does not smoke, does not abuse alcohol.

Mental status. Consciousness is clear, correctly oriented in place, time, self. Delusions and hallucinations were not revealed, intrusions of the type of flashbacks were noted, in which the re-experiencing of a helicopter accident was reproduced. She experienced severe anxiety, fear of losing control over her mental state. The mood is lowered, with a predominance of anhedonia, emotional detachment, without pronounced daily fluctuations in affect. Distracted attention, difficulty concentrating and remembering due to anxiety. Sleep with disturbed falling asleep, superficial, restless, without feeling of rest in the morning. Appetite is slightly reduced, the taste of food is blunted. Dangerous and suicidal tendencies are denied.

She experienced severe anxiety, fear of losing control over her mental state. The mood is lowered, with a predominance of anhedonia, emotional detachment, without pronounced daily fluctuations in affect. Distracted attention, difficulty concentrating and remembering due to anxiety. Sleep with disturbed falling asleep, superficial, restless, without feeling of rest in the morning. Appetite is slightly reduced, the taste of food is blunted. Dangerous and suicidal tendencies are denied.

Diagnosis: Post-traumatic stress disorder F43.1; Moderate depressive episode F32.1.

Treatment

Venlafaxine 150 mg once daily (encapsulated form), tofisopam 100 mg for 4 weeks, trauma-focused CBT, aimed at psychoeducation, teaching emotional regulation skills, working through traumatic memories, finding new landmarks.

After 2 weeks the patient noted an improvement in well-being, a decrease in anxiety and autonomic disorders, and normalization of sleep.