Dsm criteria for bipolar 1

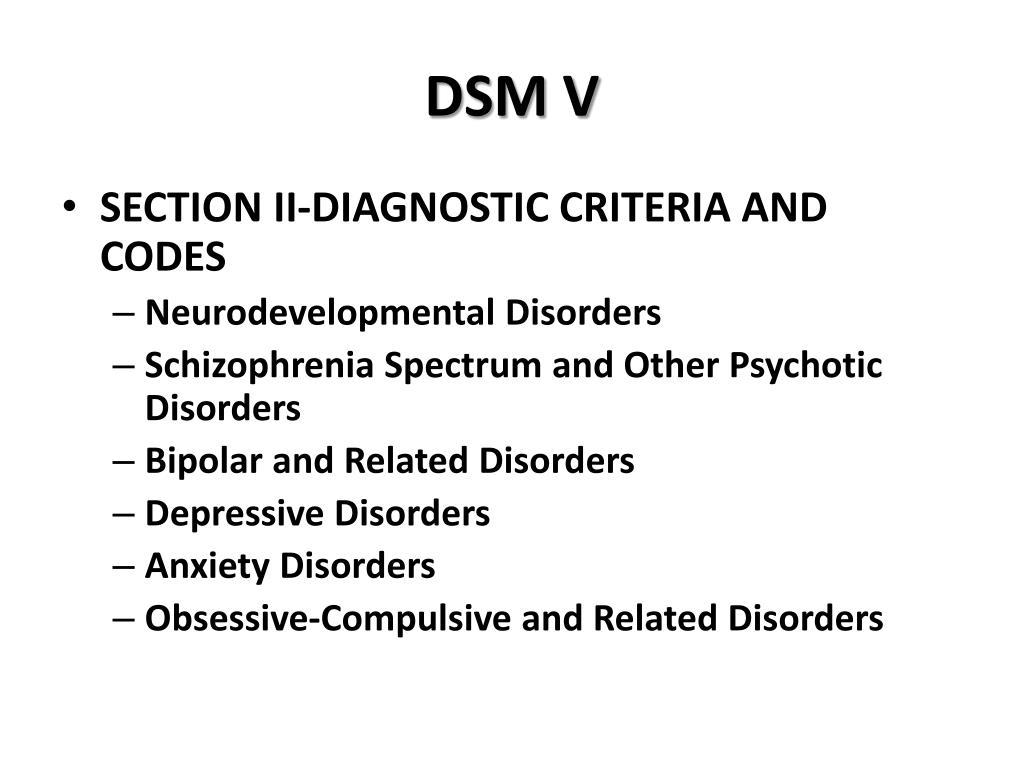

Bipolar Definition and DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

What is Bipolar Disorder?

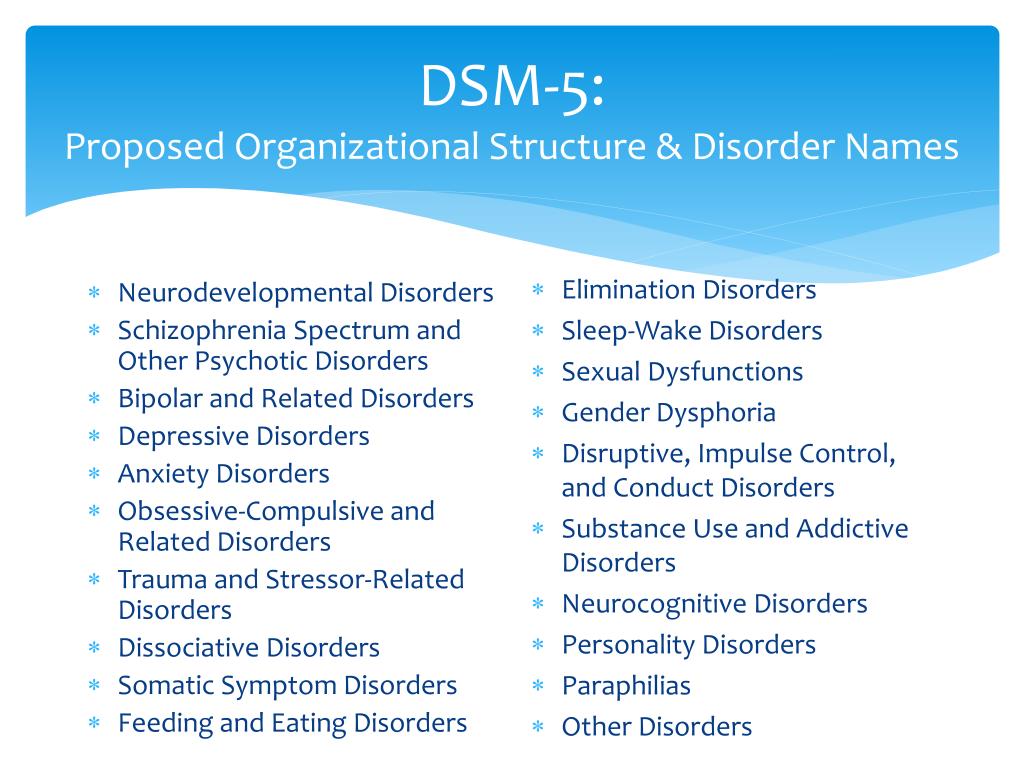

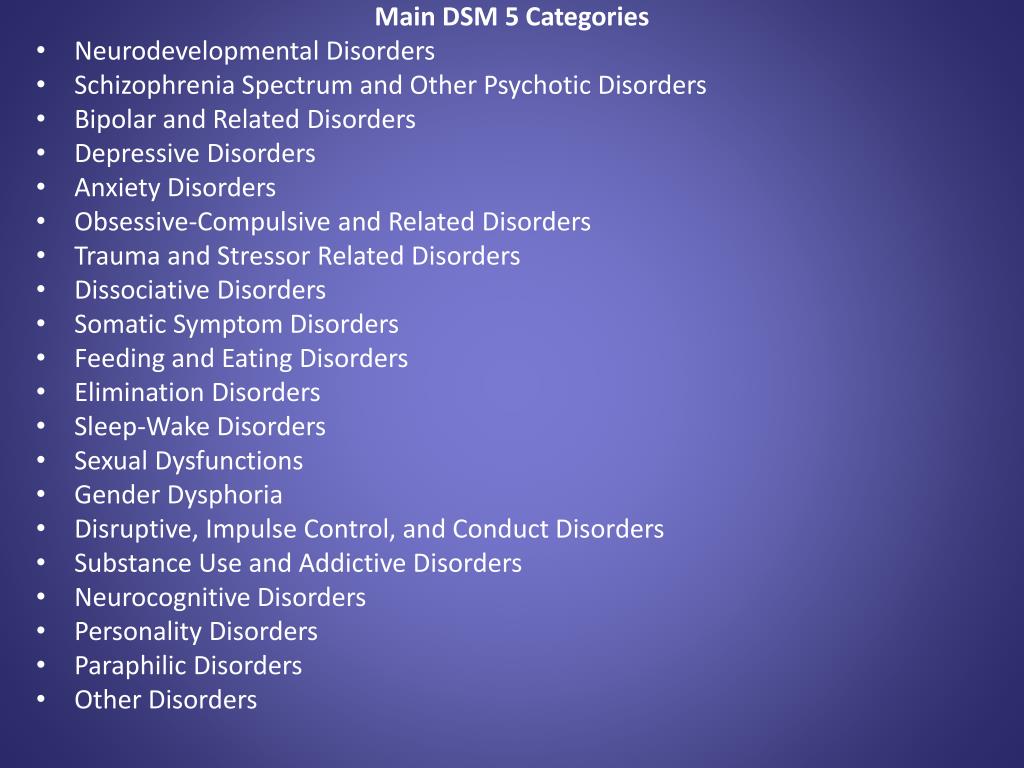

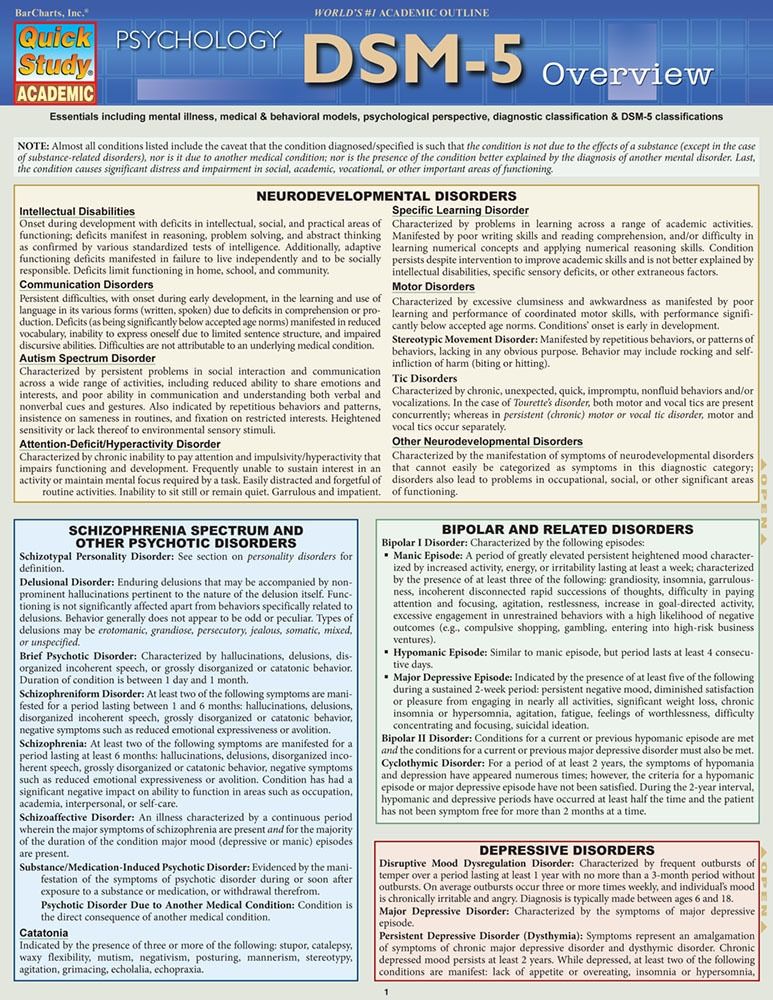

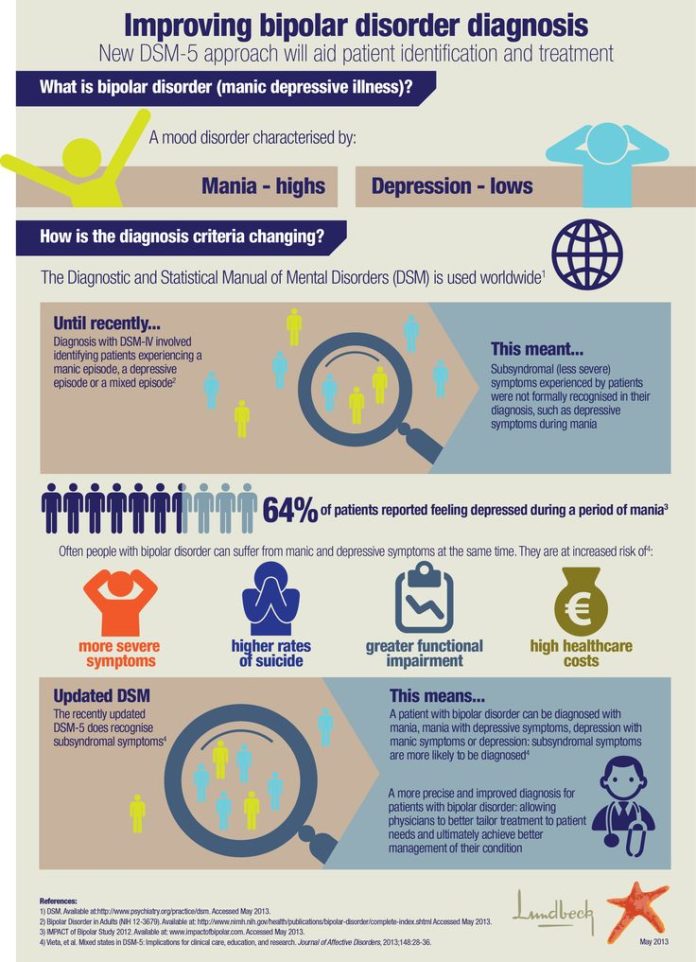

Bipolar disorders are described by the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) as a group of brain disorders that cause extreme fluctuation in a person’s mood, energy, and ability to function.

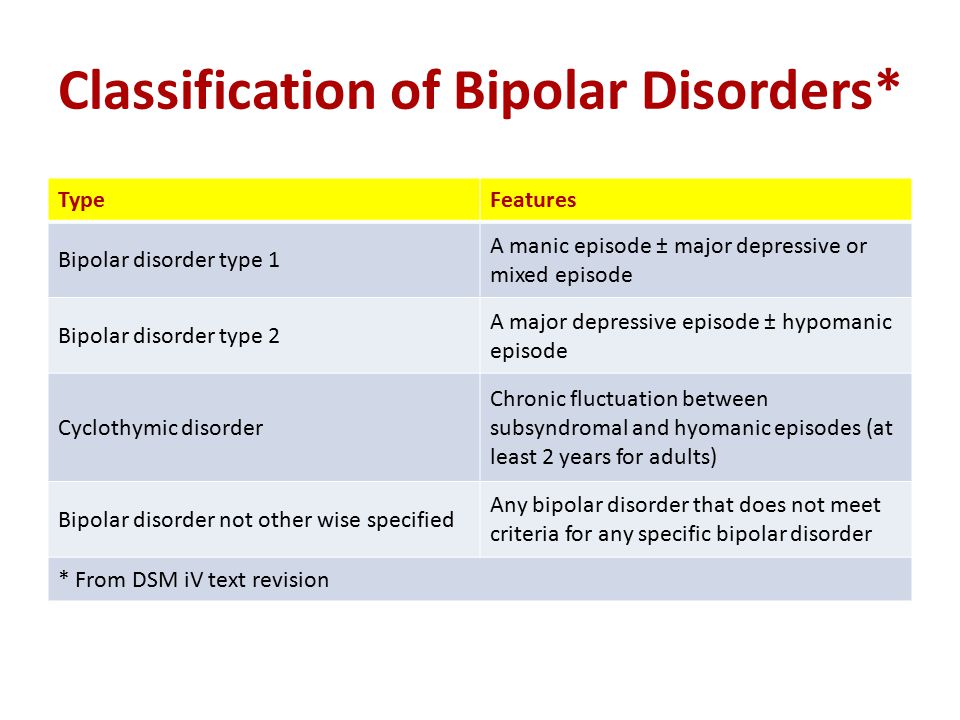

Bipolar disorder is a category that includes three different condition--bipolar I, bipolar II, and cyclothymic disorder.

Bipolar I disorder is a manic-depressive disorder that can exist both with and without psychotic episodes

Bipolar II disorder consists of depressive and manic episodes which alternate and are typically less severe and do not inhibit function

Cyclothymic disorder is a cyclic disorder that causes brief episodes of hypomania and depression

Bipolar and related disorders are given a chapter of their own in the DSM-5, between depressive disorders and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. People who live with bipolar disorder experience periods of great excitement, overactivity, delusions, and euphoria (known as mania) and other periods of feeling sad and hopeless (known as depression). As such, the use of the word bipolar reflects this fluctuation between extreme highs and extreme lows. The diagnosis is frequently assigned to young patients presenting with a (first) major depressive episode. In these cases, diagnosis is exclusively based on psychiatric history provided by family and caregivers, not on the current psychopathological assessment by the psychiatrist.

Bipolar disorder occurs in up to 2.5% of the population, but the prevalence is much higher among first-degree relatives of individuals with bipolar or schizophrenia disorder. Individuals with bipolar disorder experience mood swings that are less severe in intensity. During what is known as a hypomanic episode, a person may experience elevated mood, increased self-esteem, and a decreased need for sleep. Unlike a manic episode, these symptoms are not so severe as to impact daily functioning or cause psychotic symptoms.

Unlike a manic episode, these symptoms are not so severe as to impact daily functioning or cause psychotic symptoms.

What’s more, in some cases, a bipolar episode can include symptoms of both mania and depression; this is what’s known as an episode with mixed features. People experiencing an episode with mixed features may feel extreme sadness, guilt, and worthlessness, while at the same experiencing high energy, racing thoughts and speech, and overactivity. It is not uncommon during a mixed episode for a person to go from being exuberantly happy to be expressing suicidal thoughts in a matter of moments.

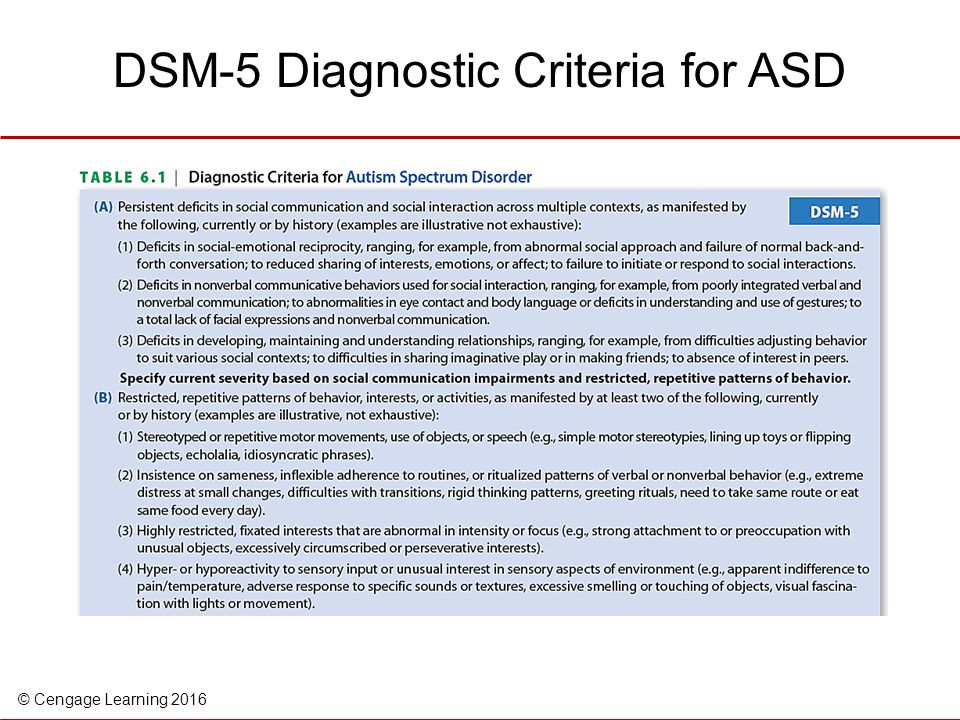

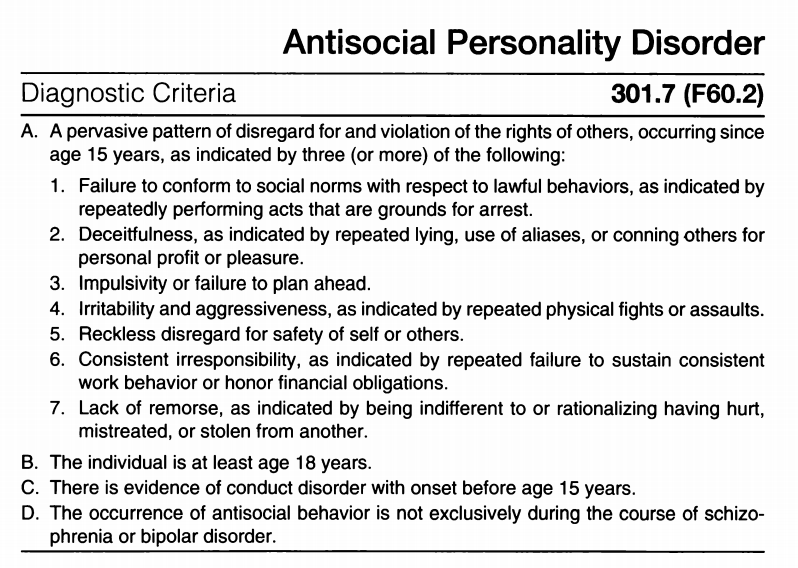

Bipolar Disorder DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

Talking with a doctor or mental health professional is the first step in identifying bipolar disorder. Firstly, a doctor may perform a physical evaluation to rule out any other conditions that may be causing symptoms. If no other illnesses are present, the doctor will conduct a comprehensive mental health evaluation to assess the patient’s symptoms in accordance with the specific criteria from the American Psychiatric Association’s

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). To be diagnosed with bipolar disorder, a person must have experienced at least one episode of mania or hypomania.

To be diagnosed with bipolar disorder, a person must have experienced at least one episode of mania or hypomania.

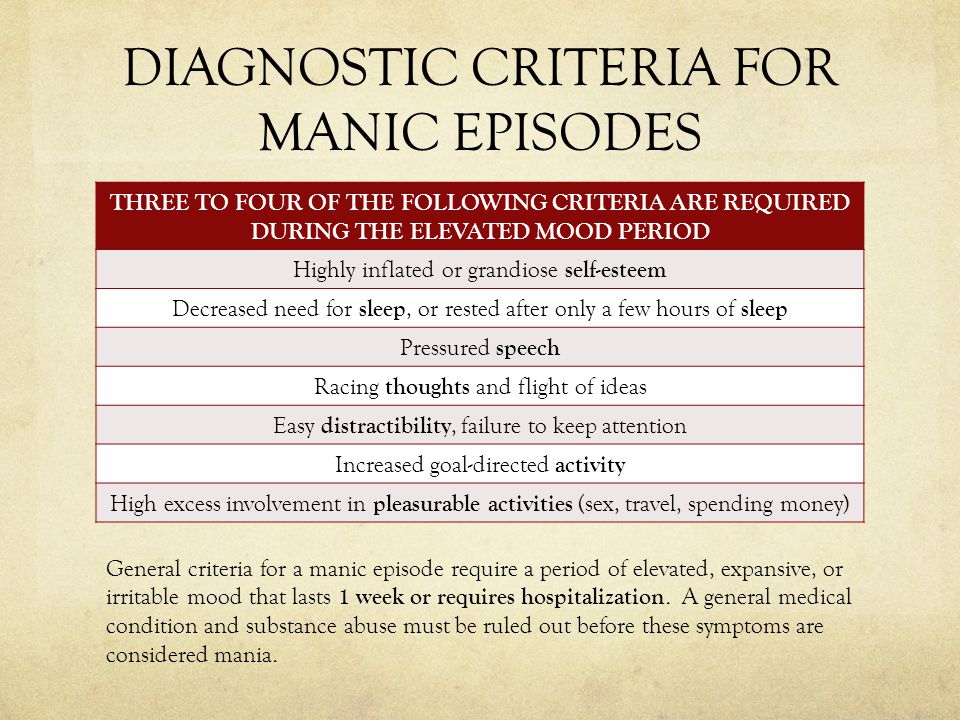

To be considered mania, the elevated, expansive, or irritable mood must last for at least one week and be present most of the day, nearly every day. To be considered hypomania, the mood must last at least four consecutive days and be present most of the day, almost every day.

During this period, three or more of the following symptoms must be present and represent a significant change from usual behavior:

Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

Decreased need for sleep

Increased talkativeness

Racing thoughts

Distracted easily

Increase in goal-directed activity or psychomotor agitation

Engaging in activities that hold the potential for painful consequences, e.g., unrestrained buying sprees

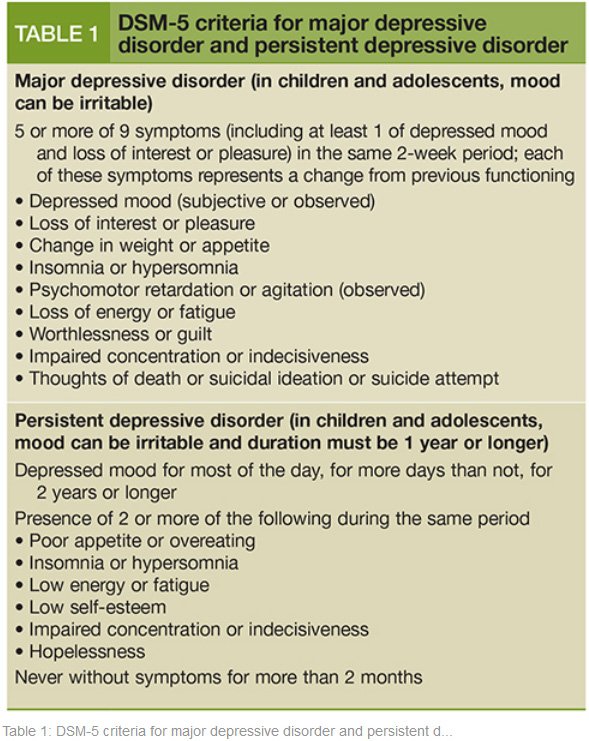

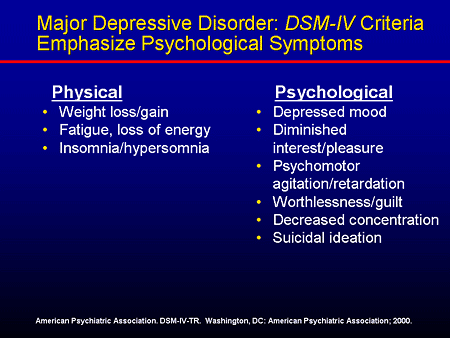

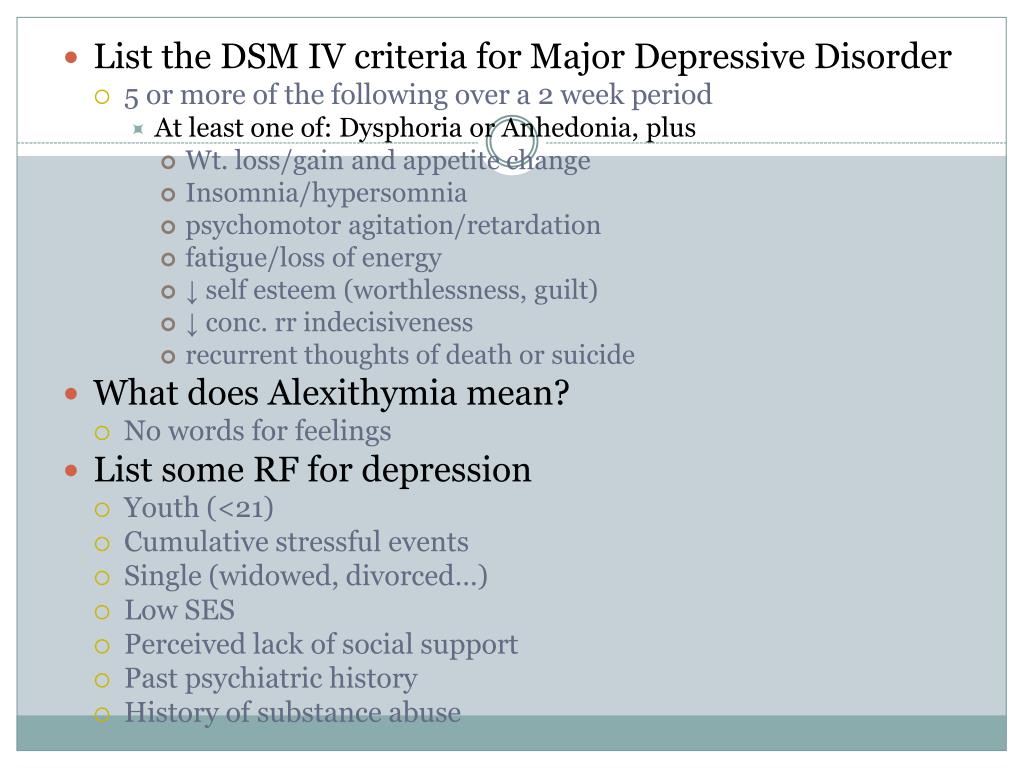

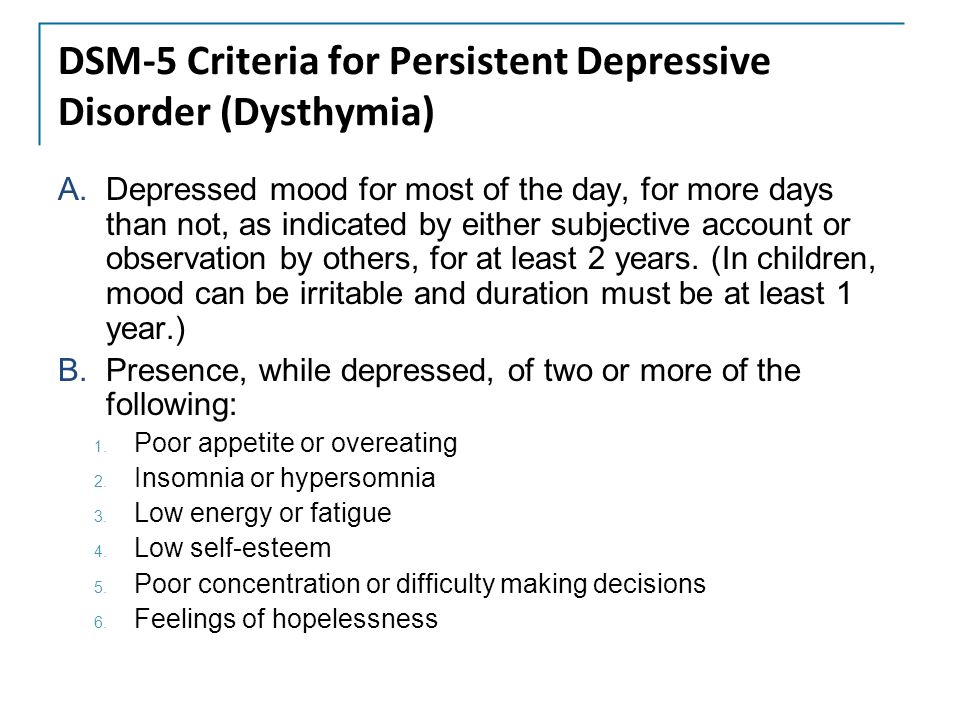

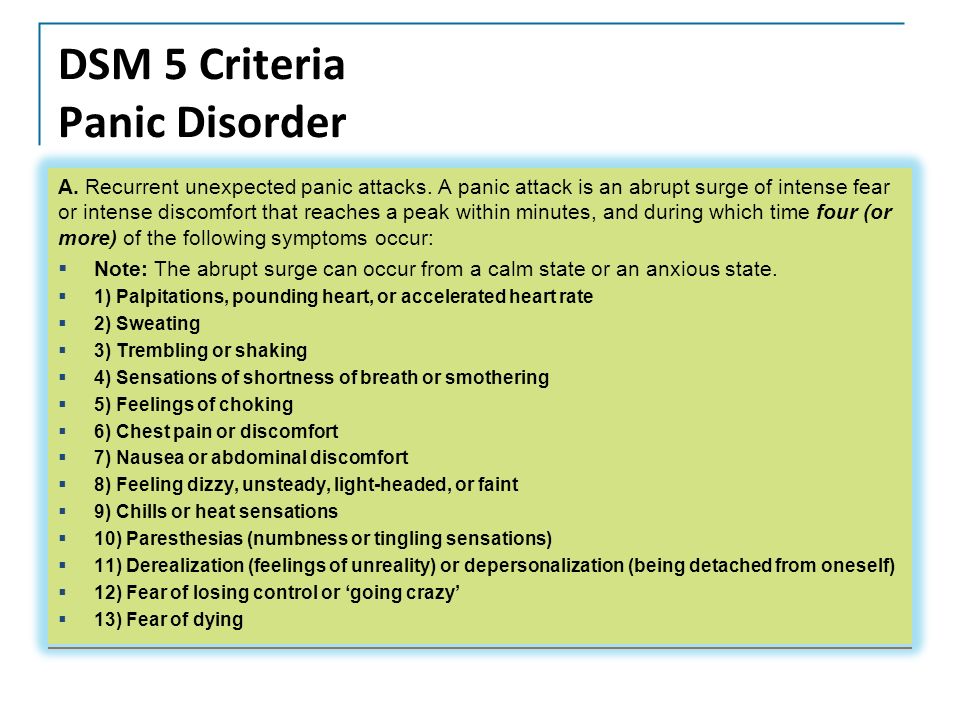

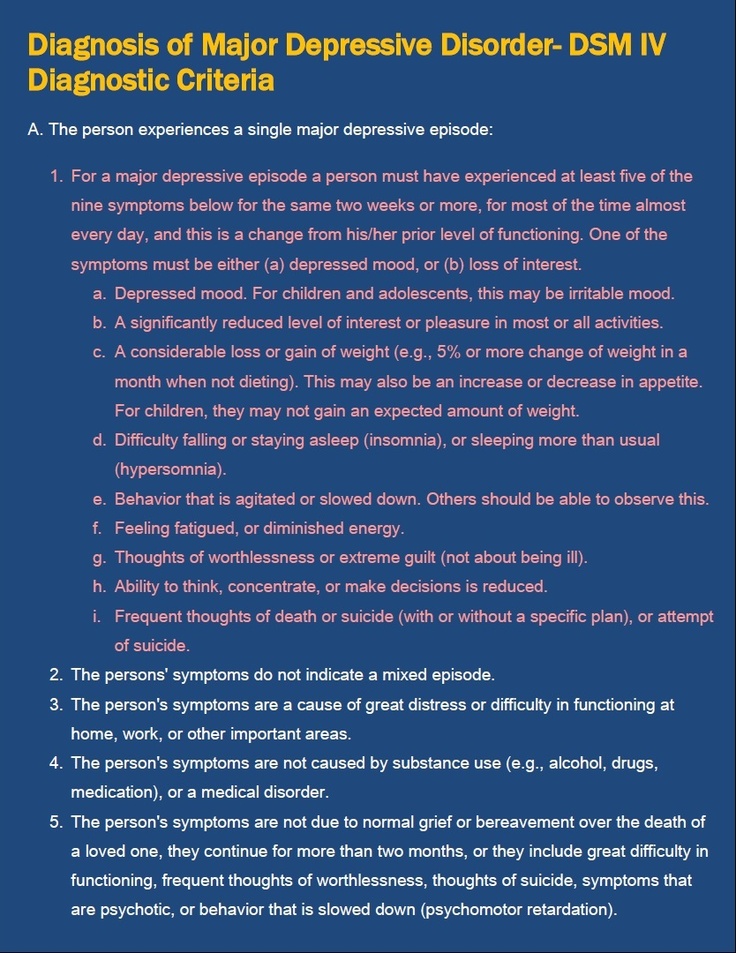

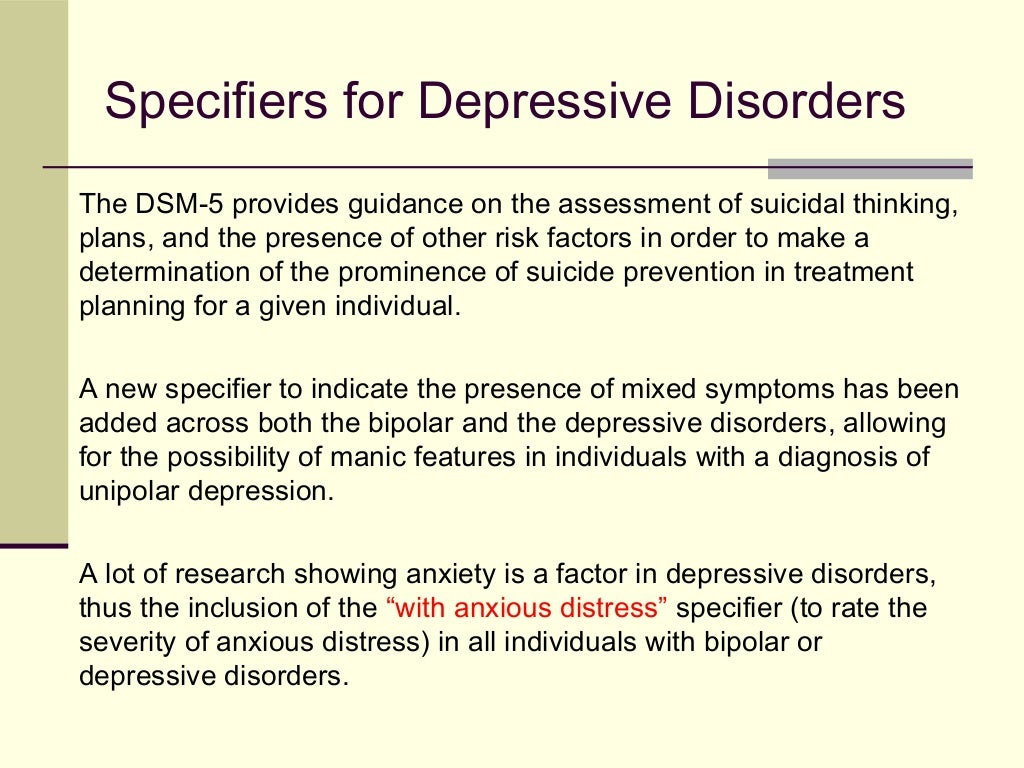

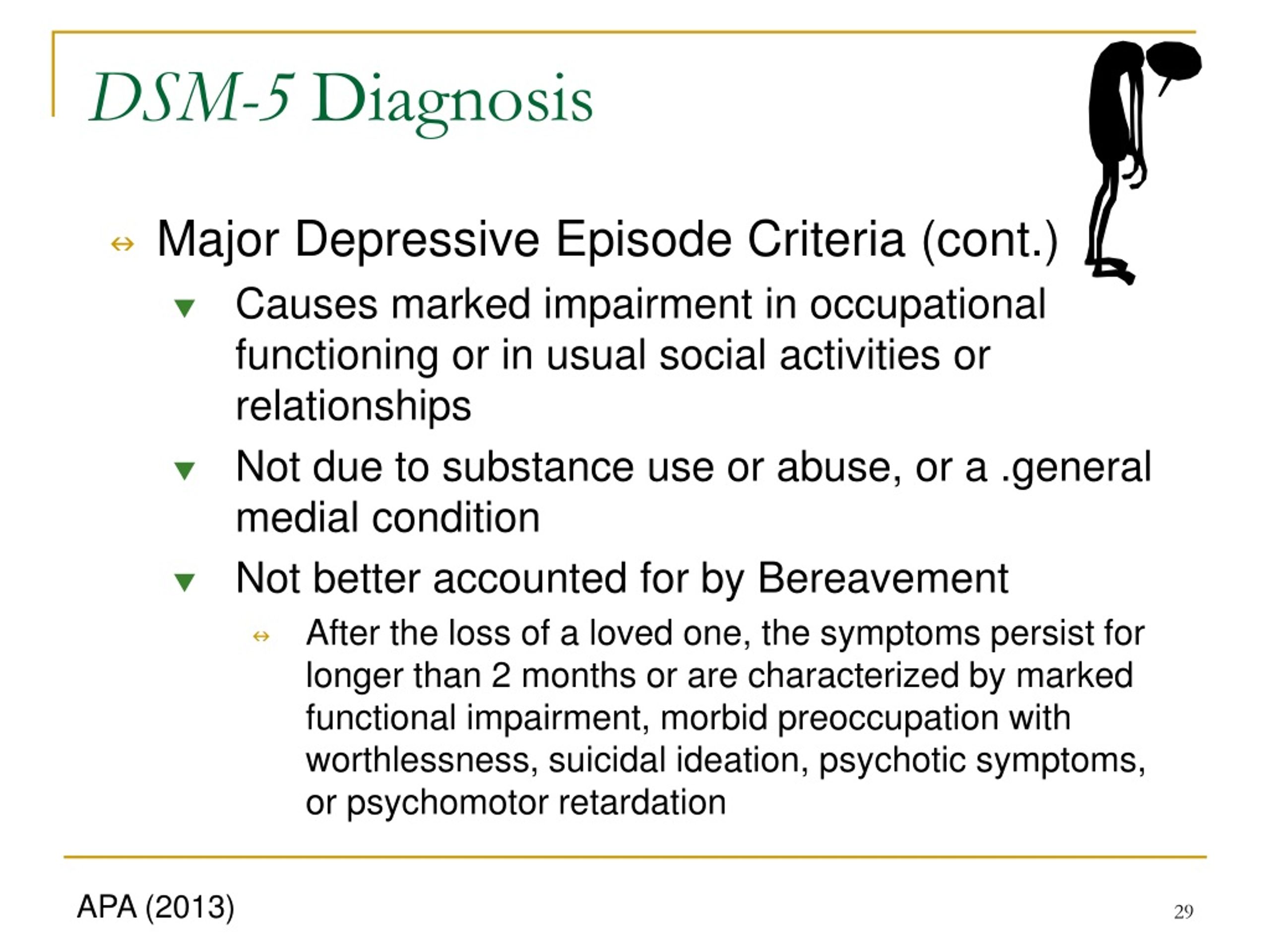

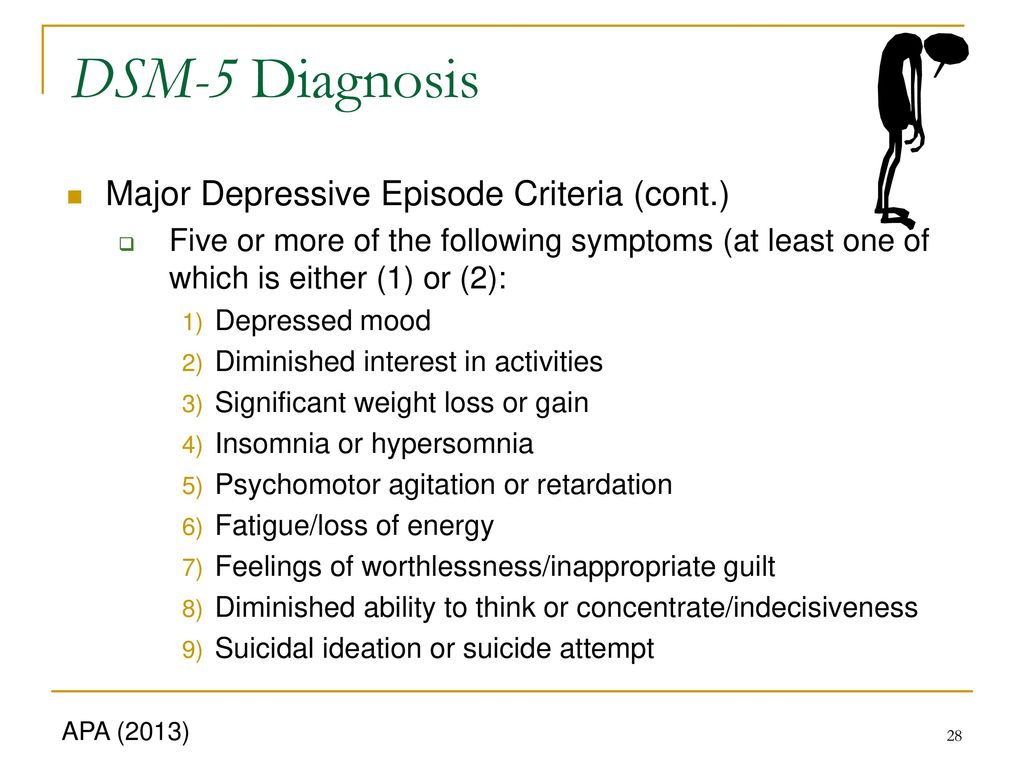

The depressive side of bipolar disorder is characterized by a major depressive episode resulting in depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure in life. The DSM-5 states that a person must experience five or more of the following symptoms in two weeks to be diagnosed with a major depressive episode:

The DSM-5 states that a person must experience five or more of the following symptoms in two weeks to be diagnosed with a major depressive episode:

Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day

Loss of interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities

Significant weight loss or decrease or increase in appetite

Engaging in purposeless movements, such as pacing the room

Fatigue or loss of energy

Feelings of worthlessness or guilt

Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness

Recurrent thoughts of death, recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt

Could My Mood Swings Be Bipolar Disorder?

We all have good and bad days –sometimes we feel on top of the world and other days, if we lose a job, go through a bad break-up, or fall out with a friend, we may be down in the dumps. But have you ever gone to bed one night feeling euphoric and woken up the next morning to find you feel empty and hopeless? Have you ever noticed your high-energy levels and racing thoughts suddenly turn to feelings of worthlessness and an inability to experience pleasure doing the same things you once enjoyed? If not, it’s unlikely that you have bipolar disorder.

Several important features of bipolar disorder allow us to distinguish between the severe mental condition and the occasional mood swing. The first feature is whether the fluctuations in mood are caused by a situation, person, or event, or appear without cause. While the moods of people with bipolar disorder can be affected by situational variables, people with bipolar disorder also frequently become manic or depressed for no apparent reason. In comparison, for most people, moodiness is tied to a situational event, particularly stressful period, or even hormonal changes in the body.

The duration and intensity of high and low moods are also factors to consider when making a judgment on whether you should be concerned about bipolar disorder. Individuals with bipolar experience an elevated or irritable mood for at least four consecutive days, while their depressive episodes last for at least two weeks at a time. If you’re struggling with moodiness, the intensity of the moods you are experiencing is likely significantly higher on the intensity scale than those of people with bipolar disorder.

If you’re unsure about whether your mood swings are normal or could be symptomatic of bipolar disorder. You may want to start a mood diary using an app such as "Daylio" to help keep track and monitor your mood fluctuations. Psychologists and therapists suggest that this can be a therapeutic activity. It can also help you to determine whether events or situations in your life cause your mood swings or if they appear seemingly without cause.

If you are concerned about bipolar disorder, we encourage you to make an appointment with your doctor or mental health professional to discuss the specific details of your fluctuating mood.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Notes: This article was originally published October 13, 2019 and most recently updated September 29, 2020.

The Difference Between Bipolar Disorder I and II

Bipolar Disorder

Kathleen Smith, PhD, LPC

Medical ReviewerJuli Fraga, PsyD

Many people think of rapid mood changes when they think of Bipolar Disorder. But there are several different categories of mood disorders depending on a person’s symptoms, and not all of these categories include the highs of mania and lows of depression. Only a doctor or mental health professional can provide a diagnosis for a mood disorder, and it may take years of observation to get an accurate diagnosis.

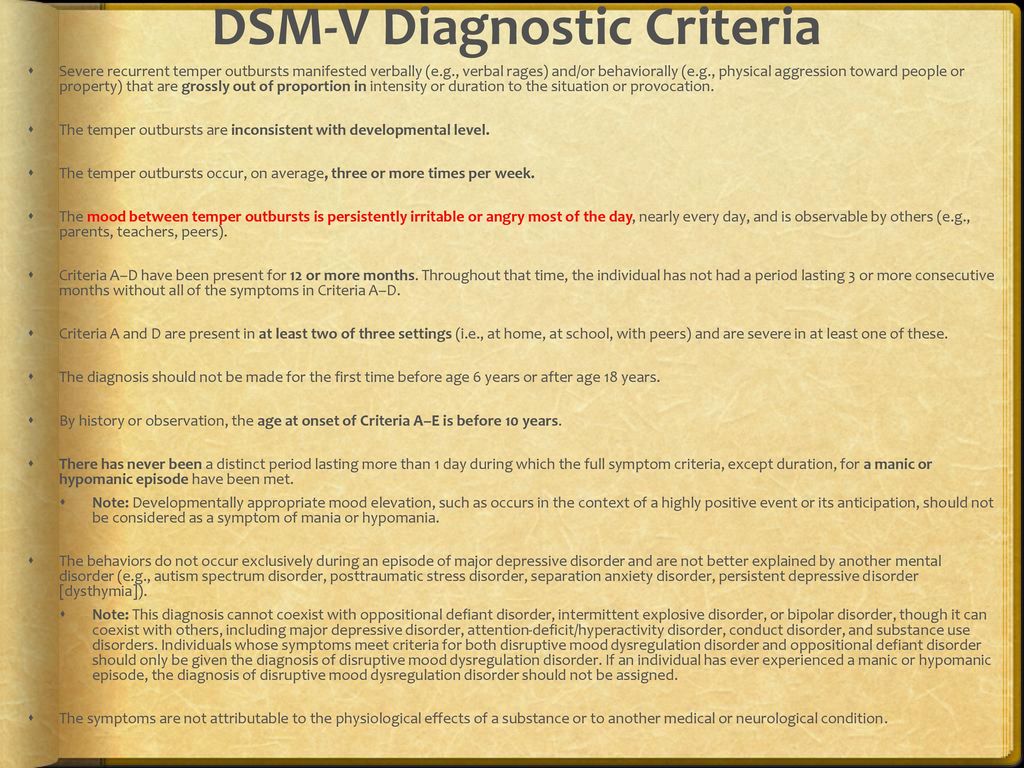

Bipolar I disorder requires symptoms to meet the full criteria for what is known as a manic episode. You do not have to experience depression to be diagnosed with Bipolar I, but many people with the diagnosis experience both kinds of mood episodes.¹

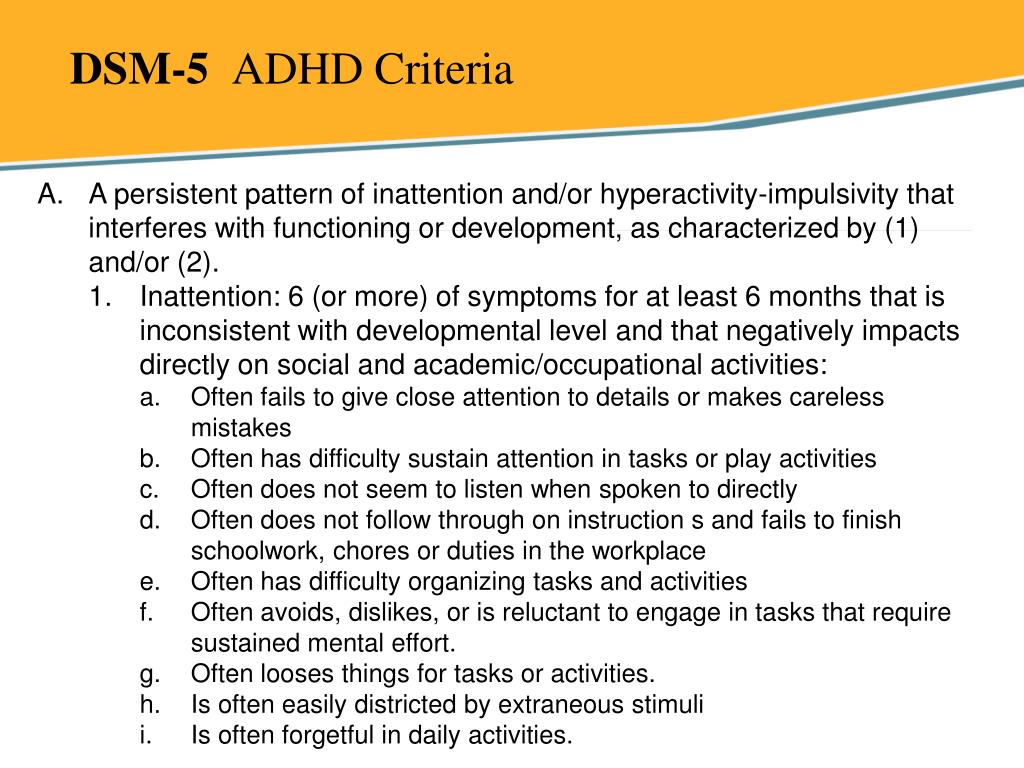

A manic episode must include at least three of the following symptoms:

increased talkativeness

increased self-esteem or grandiosity

decreased need for sleep

increase in goal-direct activity, energy level, or irritability

racing thoughts

poor attention

increased risk-taking (spending money, risky sexual behaviors, etc.

)

)

Mania is much more extreme than a sudden burst in energy or motivation or a happy mood. It often results in problems in work, school, and relationships, and it some cases it may require hospitalization. A manic episode is also just as frequently characterized by an irritable mood as an elevated one for people with Bipolar I, so never assume a manic episode is not present because a person doesn’t not appear happy or enthusiastic.²

To qualify for a diagnosis of Bipolar II Disorder, a person has to have experienced a depressive episode and a less severe form of mania which is known as hypomania. A person experiencing mania will exhibit manic symptoms but is able to continue with day-to-day responsibilities and may even see an increase in job performance or other goal-directed activity. The elevated mood, however, is not so severe that the person requires hospitalization or experiences significant disruption at home or work.³

To meet the criteria for a depressive episode, a person must experience 5 or more of the following symptoms:

depressed mood

changes in sleep

changes in eating

fatigue or lack of energy

loss of pleasure in activities once enjoyed

restlessness or slowing down

feelings of guilt or worthlessness

indecision or difficulty concentrating

thoughts of suicide

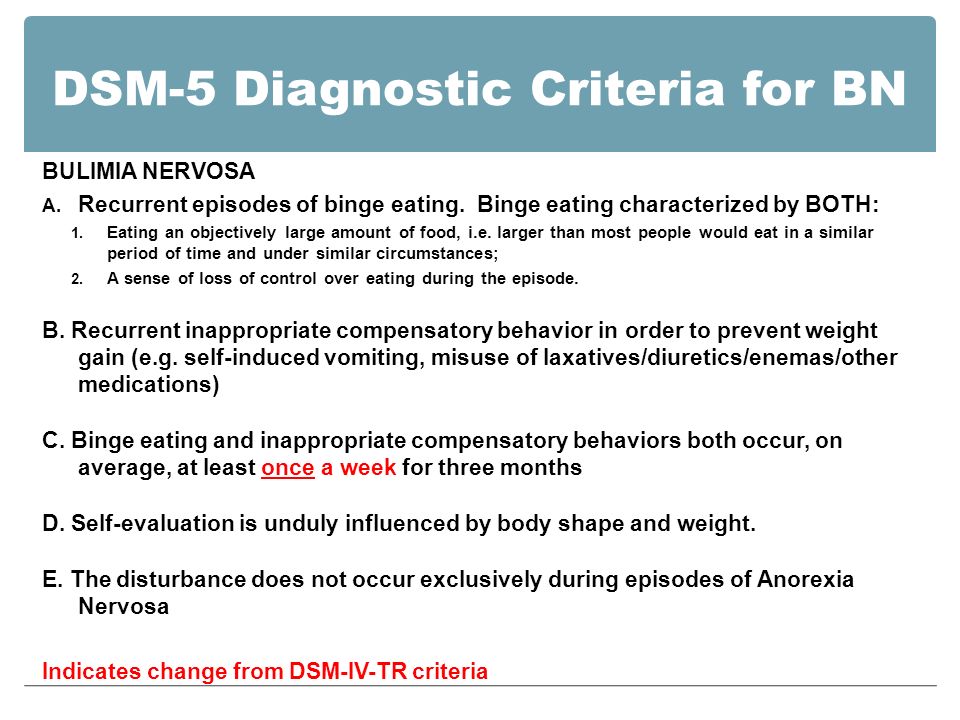

Many people with Bipolar II Disorder are diagnosed with depression because they fail to report the elevated mood symptoms of hypomania to their doctor. People with Bipolar II also may be at higher risk for substance use and eating disorders. They are also more likely to have a relative in their immediate family with a psychiatric illness. ⁴ To summarize, a Bipolar I diagnosis requires a manic episode but also can include depression. A Bipolar II diagnosis requires both a depressive episode and a hypomanic episode.

People with Bipolar II also may be at higher risk for substance use and eating disorders. They are also more likely to have a relative in their immediate family with a psychiatric illness. ⁴ To summarize, a Bipolar I diagnosis requires a manic episode but also can include depression. A Bipolar II diagnosis requires both a depressive episode and a hypomanic episode.

If you’ve experienced manic and depressive symptoms for several years without meeting the requirements for a full manic or depressive episode, then your doctor may diagnose you with what is known as Cyclothymic Disorder. Some people with Bipolar Disorder also meet the criteria for rapid cycling, which requires ⁴ mood episodes of depression, mania, or hypomania in a twelve-month period. Rapid cycling can occur with both types of Bipolar Disorder.⁵

Your Bipolar diagnosis can affect the course of treatment and medication recommended by your doctor, so it’s important to report all mood symptoms to your doctor. Treating depression and not mania could increase risk of mania episode or of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, so it’s imperative to keep track of both highs and lows. ⁶ Because drugs and alcohol can trigger episodes of mania or depression, you may have to complete detoxification from substances before you are given a diagnosis.

⁶ Because drugs and alcohol can trigger episodes of mania or depression, you may have to complete detoxification from substances before you are given a diagnosis.

Keeping track of your mood, energy level, attention span, and behaviors every day can help you receive the most accurate diagnosis. Staying informed and staying patient with the diagnostic process also gives you the best chance for managing symptoms and reducing the frequency and intensity of mood changes. With the right team of support and the right tools for keeping track of your symptoms, it is possible to manage mental illness and live a full and goal-directed life. What steps can you take today to plug into the best resources for your mind and body?

- https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 (Last accessed May 13th, 2019)

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165032710007172 (Last accessed May 13th, 2019)

- https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.

1176/appi.books.9780890425596 (Last accessed May 13th, 2019)

1176/appi.books.9780890425596 (Last accessed May 13th, 2019) - https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165032710007172 (Last accessed May 13th, 2019)

- https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 (Last accessed May 13th, 2019)

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2922360/ (Last accessed May 13th, 2019)

Notes: This article was originally published May 22, 2017 and most recently updated December 20, 2022.

gender characteristics of the course and therapy

For the first time about circular psychosis, or "insanity in two forms", two French psychiatrists J. Falret and J. Baillarger reported in the middle of the 19th century. E. Kraepelin in 1896 proposed to combine a group of affective psychoses with polar clinical manifestations (depressive and manic) into a single manic-depressive psychosis based on the phase course of the disease with alternating exacerbations and remissions and a favorable prognosis, in contrast to dementia praecox. At the same time, he pointed out the difficulty of drawing clear boundaries between these polar affective disorders, since they can quickly replace each other and mix. For example, one may encounter depression with agitation or mania with lethargy [1]. Later, E. Bleuler noted that “the more it is possible to trace the patient's life, the less often it is possible to make the correct series of one homogeneous attacks” [2]. This was confirmed in later studies, which showed that during the life of the patient the polarity of attacks, their frequency, duration and severity may change. Approximately 40% of patients who were initially diagnosed with recurrent depression were subsequently diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder (BAD). In other words, a "drift" from a pseudo-monopolar flow to a BAR is possible [3].

At the same time, he pointed out the difficulty of drawing clear boundaries between these polar affective disorders, since they can quickly replace each other and mix. For example, one may encounter depression with agitation or mania with lethargy [1]. Later, E. Bleuler noted that “the more it is possible to trace the patient's life, the less often it is possible to make the correct series of one homogeneous attacks” [2]. This was confirmed in later studies, which showed that during the life of the patient the polarity of attacks, their frequency, duration and severity may change. Approximately 40% of patients who were initially diagnosed with recurrent depression were subsequently diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder (BAD). In other words, a "drift" from a pseudo-monopolar flow to a BAR is possible [3].

In 1957, K. Leonhard [4] proposed the division of affective psychoses into monopolar and bipolar ones, which was confirmed in a number of subsequent studies [5, 6].

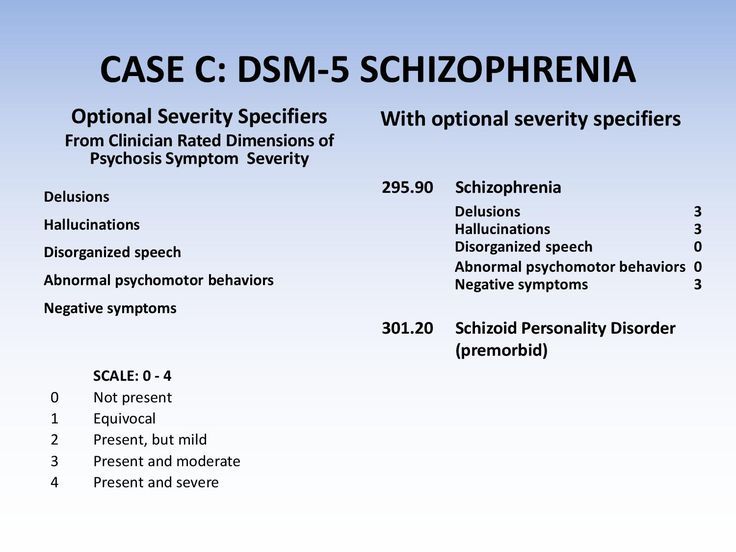

In 1976, the American psychiatrist D. Dunner proposed to divide bipolar disorder into two types, depending on the manifestations of manic syndrome [7]. In DSM-5, in addition to BAD type I, which occurs with mania, and BAD type II, which occurs with hypomania, which, as a rule, does not require hospitalization [8], cyclothymia is distinguished, which is considered by a number of authors as BAD type III. The position of the latter remained controversial for a long time. E. Kraepelin considered it as a "cyclothymic temperament" - a predictor of manic-depressive psychosis [6]. Yu.V. Kannabich considered cyclothymia to be a non-psychotic form of phasic diseases, and P.B. Gannushkin attributed cyclothymia to a number of psychopathy [9]. A subsequent study showed that in 1/3 of the personalities of the cyclothymic circle, affective symptoms worsen over time - the appearance of more pronounced hypomania, accompanied by the abuse of psychoactive substances and alcohol, violations of the law, and more severe and prolonged depressions [10, 11].

Dunner proposed to divide bipolar disorder into two types, depending on the manifestations of manic syndrome [7]. In DSM-5, in addition to BAD type I, which occurs with mania, and BAD type II, which occurs with hypomania, which, as a rule, does not require hospitalization [8], cyclothymia is distinguished, which is considered by a number of authors as BAD type III. The position of the latter remained controversial for a long time. E. Kraepelin considered it as a "cyclothymic temperament" - a predictor of manic-depressive psychosis [6]. Yu.V. Kannabich considered cyclothymia to be a non-psychotic form of phasic diseases, and P.B. Gannushkin attributed cyclothymia to a number of psychopathy [9]. A subsequent study showed that in 1/3 of the personalities of the cyclothymic circle, affective symptoms worsen over time - the appearance of more pronounced hypomania, accompanied by the abuse of psychoactive substances and alcohol, violations of the law, and more severe and prolonged depressions [10, 11]. J. Klerman (1987) included cyclothymia in the bipolar spectrum of disorders, and also proposed his own variants of the bipolar disorder classification, including 6 types of the course of the disease. The classification has been expanded to include antidepressant-induced manias; unipolar, or recurrent, mania without depression; depressions associated with hyperthymic temperament; recurrent depression in patients whose relatives suffer from bipolar disorder; late depression with mixed features progressing to a syndrome similar to dementia. The latter are more often diagnosed in the elderly due to the burden of somatic and neurological diseases [12].

J. Klerman (1987) included cyclothymia in the bipolar spectrum of disorders, and also proposed his own variants of the bipolar disorder classification, including 6 types of the course of the disease. The classification has been expanded to include antidepressant-induced manias; unipolar, or recurrent, mania without depression; depressions associated with hyperthymic temperament; recurrent depression in patients whose relatives suffer from bipolar disorder; late depression with mixed features progressing to a syndrome similar to dementia. The latter are more often diagnosed in the elderly due to the burden of somatic and neurological diseases [12].

The ICD-10 does not distinguish between individual types of bipolar disorder, using a predominantly syndromic approach to diagnosis, which allows the most accurate characterization of the patient's status and the stage of his disease at the present time, taking into account the severity and accompanying symptoms [13].

Difficulties in diagnosing BAD

If at present the definition of bipolar disorder as an independent nosology has been resolved, then the issues of differential diagnosis of recurrent affective disorder (RDD) and bipolar disorder, as well as establishing differences in the depressive syndrome within these disorders, constitute a certain diagnostic difficulty and many studies are devoted to them [14].

The key differential criterion for the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, as mentioned above, is the presence of hypomanic or manic phases in the anamnesis of the disease. However, the frequent misdiagnosis of recurrent depressive disorder in patients with bipolar disorder is due to the fact that patients do not assess the hypomanic or manic state as painful, therefore they do not go to the doctor and do not report the past "mood lift" when collecting anamnestic information. In the French study EPIDEP [15], using a specially designed questionnaire to objectify the history data obtained from patients, the prevalence of bipolar disorder among depressed patients increased almost 2-fold, from 22 to 40%.

Factors complicating the process of diagnosis include frequent comorbidity of bipolar disorder with other disorders, especially with anxiety and addictive disorders [16, 17], as well as delayed onset of manic or hypomanic symptoms in patients with recurrent depressive phases [18].

Epidemiology and medical and social significance of BAD

Due to the difficulty of correctly and timely diagnosing bipolar disorder, information on the prevalence of this disorder in the population varies widely. Incidence rates in the general population range from 1.5-6.5%. The ratio of incidence among men and women is 1:1. At the same time, there is evidence of a higher incidence of women with BAD type II [19]. According to the results of a number of studies, the frequency of BAD I is from 0.4 to 1.6%, and BAD II is from 0.5 to 1.9% [20]. In Russia, there is no separate record of cases of BAD I and BAD II due to the absence of separate codes for them in the ICD-10 [19].

Despite the fact that the specific contribution of bipolar disorder to the total number of depressive states is not so large, the disorder itself is associated with a high risk of social maladaptation. R. Joffe et al. [21] showed that 50% of the time per year, patients with bipolar disorder are in a euthymic state, 41% are in a state of depression, and only 9% - in a state of mania. However, the quality of their life, social and family functioning, the possibility of self-realization are violated even in the euthymic period, which a number of authors [16, 22] associate with “strange”, defiant and impulsive behavior both during affective upsurges and in the period between attacks. Among patients with bipolar disorder, the unemployment rate is 2 times higher than in the general population. Also, the frequency of divorces in families in which the husband or wife suffers from bipolar disorder is 3 times higher than in the control group of mentally healthy people.

However, the quality of their life, social and family functioning, the possibility of self-realization are violated even in the euthymic period, which a number of authors [16, 22] associate with “strange”, defiant and impulsive behavior both during affective upsurges and in the period between attacks. Among patients with bipolar disorder, the unemployment rate is 2 times higher than in the general population. Also, the frequency of divorces in families in which the husband or wife suffers from bipolar disorder is 3 times higher than in the control group of mentally healthy people.

The risk of developing alcoholism in bipolar disorder is 6-7 times higher than in the general population [17], while in men it is 3 times higher, and in women it is 7 times higher [23]. The views of individual researchers on the relationship between BAD and alcoholism are different: some believe that BAD can be a risk factor for the formation of dependence on psychoactive substances (alcohol and drugs), others allow the provoking effect of the latter on the development of affective disorders, and others believe that there are common links in the pathogenesis these diseases.

A decrease in the quality of life of patients with bipolar disorder is associated not only with a mental health problem, but also with concomitant somatic diseases, such as overweight and obesity, hyperlipidemia, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, pathology of the osteoarticular system, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [24] . These data can presumably be explained by a decrease in adherence to treatment due to a decrease in motivation in such patients [25], especially considering that patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder are much more likely to have comorbid addictive disorders [26].

BAD is also associated with a high suicidal risk - more than ¼ of patients make a suicide attempt during their lifetime [27]. According to the WHO (2001), BAD ranks 6th among the causes of disability [28]. A number of studies have found that, on average, patients with bipolar disorder lose about 9 years of life expectancy, 14 years of working capacity, and 12 years of normal health [29–31].

BAR course and forecast

BAD is a disease with a complex psychopathological structure, in which there are affective phases of different polarity and severity. The intermission following the completion of the phase is characterized by an euthymic mood and the formation of criticality towards the painful episode. In some cases, the hypomanic state is assessed by patients not as painful, but, on the contrary, as a period of increased efficiency and productivity. Depending on the combination of phases and the presence of intermissions between them, several types of BAR flow are distinguished.

The relapsing "classic" type of flow, described by E. Kraepelin, is characterized by phase alternation with euthymic intervals between them. At the same time, the duration of interictal intervals shortens with age, and residual affective symptoms often persist in the interictal period [32, 33]. Intermission after the first affective attack is usually the longest and averages 4. 5 years, subsequently reduced to 1 year [34].

5 years, subsequently reduced to 1 year [34].

Dual phases of different polarity with the subsequent onset of intermission constitute an alternating type of flow. As with the relapsing course, there is a tendency to lengthen the phases and shorten the euthymic intervals up to the transition to a continual course, characterized by the absence of remissions between episodes.

A special type of continual flow is the fast cyclic type. In accordance with the DSM-IV criteria, it is determined by the development of at least four affective phases within 1 year, which can be separated by short-term remissions up to 2 months. Each depressive episode should last at least 2 weeks, each manic or mixed episode should last at least 1 week, and each hypomanic episode should last at least 4 days [35]. This type of course is more common in women with type II bipolar disorder who suffer from hypothyroidism and are constantly taking antidepressants. Such patients have an early onset of the disease and a more severe course of depressive phases associated with a high suicidal risk [36, 37]. The fast cyclic flow tends to transition to ultrafast forms with phase change over the course of a month or even a day and are actually represented by mixed states [38].

The fast cyclic flow tends to transition to ultrafast forms with phase change over the course of a month or even a day and are actually represented by mixed states [38].

Mixed states are longer compared to manic and depressive phases, characterized by a more severe course, resistance to therapy, and unexpected suicidal attempts [39].

The disease has very pronounced gender characteristics. In men, bipolar disorder begins earlier than in women [40], while the first phase is more often manic in men, and depressive in women [41, 42]. During the course of the disease, this dependence persists: the proportion of manic episodes in men is greater than in women. In women, the manifestation of the disease is often associated with menstrual-generative function and periods of hormonal changes (pubertal, postpartum, menopausal) [43]. In 20–30% of women with bipolar disorder, within 1 month after delivery, another attack of the disease develops, more often depressive [44, 45]. A postpartum episode of bipolar disorder (mania or depression in general) occurs in 40–67% of cases [46]. Although manic (hypomanic) phases are a key phenomenon in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, patients spend most of their time depressed [47, 48]. This may be related to the fact that BAD type II is diagnosed more often in women, and BAD type I is equally common in women and men [49]. Consequently, the longer clinically expressed mania does not fall into the field of vision of a psychiatrist, the longer patients (more often women) will receive inadequate treatment.

A postpartum episode of bipolar disorder (mania or depression in general) occurs in 40–67% of cases [46]. Although manic (hypomanic) phases are a key phenomenon in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, patients spend most of their time depressed [47, 48]. This may be related to the fact that BAD type II is diagnosed more often in women, and BAD type I is equally common in women and men [49]. Consequently, the longer clinically expressed mania does not fall into the field of vision of a psychiatrist, the longer patients (more often women) will receive inadequate treatment.

Features of depressive syndrome in bipolar disorder

Determining the nosological status of depression, i.e., within the framework of which disease an affective disorder arose, is still a debatable issue in psychiatry. This is due to the fact that until now the etiology of depression is not completely clear. A depressive state is considered as multifactorial, i. e. dependent on biological, psychological and social causes.

e. dependent on biological, psychological and social causes.

Despite the development of biological research (neurochemistry, genetics, neuroendocrinology), most specialists, when diagnosing RDR or BAD and prescribing therapy in practice, still focus on the clinical features of depressive states and the course of the disease.

Bipolar spectrum disorders are characterized by an earlier age of onset (19.5 ± 0.7 years) compared to RDR (37.9 ± 1.6 years), a higher frequency of exacerbations, with a shorter duration of episodes, deterioration in the autumn winter time versus classic spring-autumn exacerbations in RDR, more pronounced diurnal fluctuations with deterioration in the morning hours. Hyperthymic premorbid predominates in the group of patients with bipolar disorder, while anxiety premorbid predominates in patients with RDR, and affective disorders, schizophrenia, and alcoholism are less common in immediate relatives than in patients with phase change [50]. A weak response to antidepressant monotherapy may also be indicative of a bipolar course [51].

Despite the importance of identifying hypomania or mania for inclusion in section F31 "Bipolar affective disorder" of the ICD-10 [13], depressive episodes are of much greater clinical and socioeconomic importance in the structure of the disease.

There are significant differences in the ratio of the total duration of depressive and manic phases and between different types of bipolar disorder. One study by the US National Institute of Mental Health [43] found that patients with BAD type I and BAD type II spend a total of 30% and 52% of the observation time in the depressive phase, respectively.

Along with the differences in the duration of the depressive phase, according to many domestic and foreign authors, there are also clinical features of depression in BAD type I and BAD type II. In patients with type II bipolar disorder, anxiety affect predominates, while in patients with type I bipolar disorder, complaints of apathy are more common. Despite a higher level of psychomotor retardation, the risk of suicidal activity is significantly higher in the type I bipolar group. Patients with BAD type II are more likely to have somatic complaints and the development of panic attacks [10].

Patients with BAD type II are more likely to have somatic complaints and the development of panic attacks [10].

Depression in the structure of bipolar disorder does not always meet the criteria for a typical depressive episode (F32) according to ICD-10. In recent decades, special attention has been paid to the study of atypical depressions, the symptoms of which do not fit into the classical triad. With psychopathological differentiation of the disorders dominant in the clinical picture, A.S. Avedisova and M.P. Marachev [52] identified three variants of atypical depression with a predominance of 1) mood reactivity, 2) inversion of autonomic symptoms (hyperphagia, hypersomnia, "lead paralysis"), 3) sensitivity to rejection. According to these authors, in patients with bipolar disorder more often (33.3%) than in patients with RDR (5.5%), atypical depression occurs with a predominance of inverted autonomic symptoms. The psychopathological picture of this variant suggests the presence of hypersomnia (up to 16 hours/day, including daytime sleep), hyperphagia with an increase in body weight and sensations of heaviness in the limbs ("lead paralysis").

Patients with bipolar disorder are characterized by comorbid somatic, mental disorders and addiction diseases. Moreover, certain differences were found in women and men. In a large-scale retrospective study conducted in 45 US states from 2010 to 2014 [53], it was found that the most common comorbid somatic diseases in patients with bipolar disorder were hypertension (20.5%), asthma (12.5%) and hypothyroidism. (8.1%). At the same time, they were 3 times more common in women. Also, women with bipolar disorder had a higher risk of developing cardiometabolic disorders (obesity, diabetes mellitus).

Of the comorbid psychiatric disorders, men diagnosed with bipolar disorder are more prone to addiction disorders, while anxiety and personality disorders are more common in women. There is a clear relationship between anxiety symptoms and depression in bipolar disorder [54, 55].

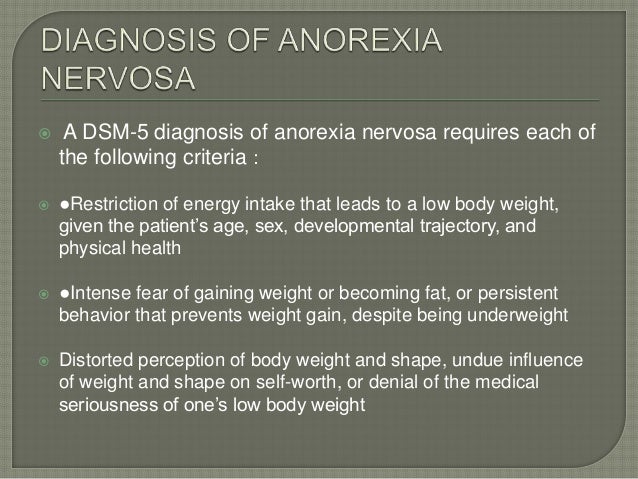

The rarest comorbid mental disorder in patients with bipolar disorder is eating disorder (0. 1% of men and 0.6% of women), but women are 11 times more likely to develop it [53].

1% of men and 0.6% of women), but women are 11 times more likely to develop it [53].

Domestic and foreign authors agree that gender features exist not only within disorders in general, but are also determined when considering individual syndromes.

It has been found that depressive syndrome in women is more characteristic of diurnal mood swings, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, fatigue and lack of sleep, increased appetite and weight gain; in men, sad affect, motor retardation, somatic symptoms, concomitant diseases of the cardiovascular, respiratory and genitourinary systems, alcohol and psychoactive substance abuse are more often detected [51, 56]. Some researchers single out the concept of "male depressive syndrome", which is characterized by sudden and recurrent bouts of anger, irritability, aggression, which can be explained by the reluctance to share experiences and seek help [57].

There are a number of gender differences in depression in terms of socio-psychological functioning. In women, depression often leads to a pronounced decrease in volitional self-regulation, which is expressed in a decrease in performance at work, an untidy appearance, and problems in the sexual sphere [58].

In women, depression often leads to a pronounced decrease in volitional self-regulation, which is expressed in a decrease in performance at work, an untidy appearance, and problems in the sexual sphere [58].

It should be noted that the results obtained reflect the gender characteristics of predominantly unipolar depression, but do not give an idea of the features of the depressive syndrome within the framework of bipolar disorder, which may be important for prognosis and treatment.

Treatment of depression in bipolar disorder

The presence of two polar phases in the structure of one disease is important for determining the tactics of treating patients with bipolar disorder. Approaches to the treatment of bipolar depression differ significantly from the treatment of depressive syndrome in other diseases. If in the case of recurrent depression the need for the use of antidepressants is not in doubt, then the use of antidepressants in patients with bipolar disorder is one of the most discussed issues.

There are several typical approaches to the treatment of bipolar depression. Thus, experts of the American Psychiatric Association consider lithium and lamotrigine to be the first-line drugs for the treatment of non-psychotic bipolar depression. Additional prescription of antidepressants is recommended only for very severe depression [59, 60]. The recommendations of the British Association of Psychopharmacologists state the need for a combination of drugs from the group of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and antimanic drugs (lithium, valproates, atypical antipsychotics) for depression of any severity from the very beginning of therapy [61]. The Canadian guidelines for the treatment of bipolar depression in BAD type I follow similar approaches. Quetiapine is considered the first-line treatment for depression in type II bipolar disorder and has been shown to be effective in many studies. If it is ineffective, combined therapy with mood stabilizers and antidepressants is recommended [62, 63].

Most researchers agree that the appointment of antidepressants "bipolar" patients significantly increases the risk of phase inversion and the development of unfavorable forms of the course of BAD (continuous, fast-cyclic). According to some authors, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) provoke phase inversion in bipolar disorder in more than 30% of cases [64]. The frequency of inversion is directly proportional to the dosages of antidepressants used.

Modern studies have shown that the inclusion of an antidepressant in the regimen of relief therapy accelerates the process of recovery from an attack and significantly increases the effectiveness of treatment without provoking the development of an inversion of the depressive phase in patients with bipolar disorder [65].

One of the first studies was conducted to study the effectiveness of paroxetine in the treatment of bipolar depression. The frequency of antidepressant-induced manias was 2–3%, which is several tens of times less than with TCAs [66].

Factors associated with a high risk of phase reversal include young age, type I bipolar disorder, rapid phase change bipolar disorder, substance abuse, mixed state, and a history of similar response to antidepressant therapy.

When using antidepressant monotherapy, a full remission is observed only in 15-20% of patients, and 20-25% of patients relapse within a few months, regardless of whether the antidepressant was continued or discontinued [67].

In accordance with the clinical guidelines for the treatment of depression in bipolar disorder, it is recommended to limit the prescription of antidepressants to a minimum period and, already at the first stage of treatment, use them in combination with an antipsychotic and / or mood stabilizer in order to prevent phase inversion.

Monotherapy with mood stabilizers seems appropriate for mild or moderate symptoms in patients who do not have a suicidal risk [68]. A number of studies have shown good efficacy of lithium carbonate, carbamazepine and lamotrigine in the treatment of depressive conditions in the context of bipolar disorder, however, the development of a thymoanaleptic effect usually takes more than 6 weeks. One double-blind, placebo-controlled study [69] of 195 patients with type I bipolar disorder showed a positive antidepressant effect after 7 weeks of lamotrigine therapy. In another study [70], the addition of the anticonvulsant topiramate or the antidepressant bupropion to normothymic therapy with valproate or lithium in 36 outpatients with bipolar depression found a reduction in depressive symptoms after 2 weeks of treatment. There is also a work [71], in which it was found that the combination of the mood stabilizer and the antidepressant paroxetine leads to an earlier manifestation of the antidepressant effect without phase inversion.

One double-blind, placebo-controlled study [69] of 195 patients with type I bipolar disorder showed a positive antidepressant effect after 7 weeks of lamotrigine therapy. In another study [70], the addition of the anticonvulsant topiramate or the antidepressant bupropion to normothymic therapy with valproate or lithium in 36 outpatients with bipolar depression found a reduction in depressive symptoms after 2 weeks of treatment. There is also a work [71], in which it was found that the combination of the mood stabilizer and the antidepressant paroxetine leads to an earlier manifestation of the antidepressant effect without phase inversion.

J. Doree et al. [72] found that in cases of failure of antidepressant monotherapy, the combination of an antidepressant with quetiapine is statistically significantly more effective than the combination of an antidepressant with lithium, both in terms of the number of responders (88 and 50%, respectively) and the number of patients who achieved remission (88 and 50%, respectively). 38% respectively).

38% respectively).

In the proposed treatment algorithms for bipolar depression, quetiapine at a dose of 600 mg/day or more is the first-line drug for type I bipolar disorder, while it is recommended to start with lamotrigine 50-200 mg/day for type II bipolar depression, and quetiapine is an alternative option in lower doses [73].

Therapy of bipolar depression with atypical antipsychotics is usually recommended for bipolar depression type 1, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, delusions of self-blame, self-deprecation. Thus, olanzapine monotherapy proved to be effective for patients with bipolar depression and comorbid anxiety [27].

Some modern authors [74] insist on the abolition of antidepressant therapy on the 2nd week after the establishment of clinical remission with a gradual dose reduction, but allow the return of thymoanaleptic therapy in case of deterioration of the patient's condition.

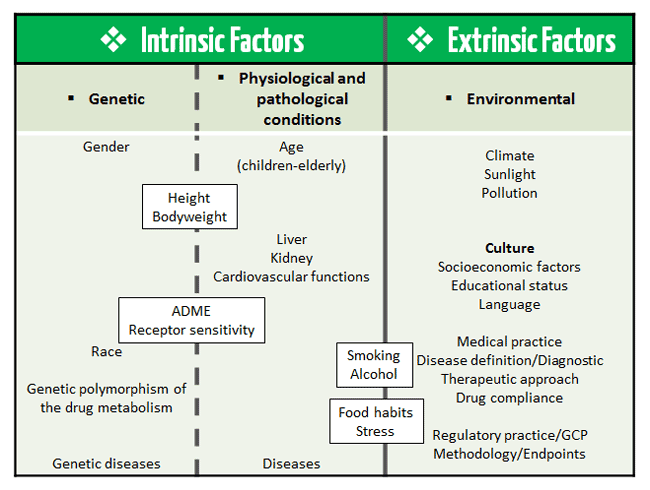

Since the end of the last century, scientists and physicians have been increasingly interested in the study of gender specifics in the treatment of depression.

The lower rate of renal filtration and hepatic metabolism in women, the higher percentage of adipose tissue compared to men and, at the same time, lower body weight lead to a higher level of concentration and a longer half-life of therapeutic drugs. These pharmacokinetic features may explain the better efficacy of antidepressant therapy in women and the possibility of using lower dosages [75].

However, a number of studies have found differences in therapeutic response to different groups of antidepressants. A slower response in women compared to men was obtained with TCAs, while women achieved faster clinical improvement with SSRIs [76].

In a study by J. Davidson et al. [77] showed that monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) were more effective than TCAs in women, while men improved more quickly when treated with the latter.

The researchers explain the observed differences by a number of factors. S. Kornstein et al. [76] noted a difference in therapeutic response to sertraline (SSRI) and imipramine (TCA) only in premenopausal women; no differences were found in postmenopausal women. Separate studies have also shown that estrogens can increase serotonergic activity [78]. An assumption was made about the effect of female sex hormones on the pharmacodynamics of antidepressants in terms of stimulating the action of SSRIs and inhibiting the activity of TCAs [76]. It is necessary to take into account the clinical features of depression. In women, depression more often includes atypical symptoms, which may explain the better response to SSRIs and MAO inhibitors [76, 77].

Separate studies have also shown that estrogens can increase serotonergic activity [78]. An assumption was made about the effect of female sex hormones on the pharmacodynamics of antidepressants in terms of stimulating the action of SSRIs and inhibiting the activity of TCAs [76]. It is necessary to take into account the clinical features of depression. In women, depression more often includes atypical symptoms, which may explain the better response to SSRIs and MAO inhibitors [76, 77].

In one of the comparative placebo-controlled studies of venlafaxine (selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor SNRI) and drugs from the SSRI group (fluoxetine, paroxetine, fluvoxamine) in groups of men and women, it was found that in men there were no clinically significant differences in response to drugs, while women treated with venlafaxine had a faster response (at week 2) compared to SSRIs (at week 4) and achieved sustained clinical improvement [79].

A number of studies have noted gender differences not only in the efficacy but also in the tolerability of antidepressants: when using TCAs, men are more likely to experience side effects such as difficulty urinating, sexual dysfunctions, and nausea in women. Adverse events with the use of SSRIs: in men - dyspepsia, sexual dysfunction, frequent urination; in women - nausea, dizziness.

Adverse events with the use of SSRIs: in men - dyspepsia, sexual dysfunction, frequent urination; in women - nausea, dizziness.

In recent years, the antidepressant Valdoxan (Agomelatine), an agonist of melatonin MT1- and MT2- and an antagonist of serotonin 5-HT2C receptors, has positively proven itself in the treatment of depression, which, due to its unique mechanism of action, has high antidepressant efficacy in depression of various genesis and varying severity, including severe endogenous depressive states [80]. Disorders of circadian rhythms in endogenous depression, manifested by sleep disturbances, diurnal fluctuations in the state with the corresponding dynamics of therapy, are an additional indication for the appointment of agomelatine. The results of one of the meta-analyzes [81] showed that the efficacy of agomelatine is comparable to other antidepressants (SSRIs, SNRIs), and also has a better tolerability profile, leading to a lower risk of discontinuing treatment due to the development of adverse events. Another meta-analysis [82], which summarized the results of 76 clinical trials (16,389patients) in a study of the efficacy and tolerability of the 10 most common antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder, it was shown that agomelatine was in first place in the number of patients in remission, and also differed in the maximum indicators of good tolerance.

Another meta-analysis [82], which summarized the results of 76 clinical trials (16,389patients) in a study of the efficacy and tolerability of the 10 most common antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder, it was shown that agomelatine was in first place in the number of patients in remission, and also differed in the maximum indicators of good tolerance.

The efficacy of agomelatine was equally high compared with placebo in both women and men [83]. A comparative evaluation of the effectiveness of agomelatine in recurrent depression and bipolar affective disorder showed that responders in both groups appeared already at the 2nd week of therapy, especially in the group of patients with bipolar disorder (34.8% vs. 9,1%). The initial response was faster in men with bipolar depression, especially in patients with bipolar I type who received an additional anticonvulsant (depakin or lamotrigine). By the end of therapy (week 8), the response rate was 90.9% in the RDR group and 91. 3% in the BAD group. According to the corresponding study of agomelatine conducted by domestic authors, 65.2% of patients with bipolar disorder and 54.5% with RDR achieved complete remission [3].

3% in the BAD group. According to the corresponding study of agomelatine conducted by domestic authors, 65.2% of patients with bipolar disorder and 54.5% with RDR achieved complete remission [3].

The absence of side effects such as weight gain, excessive daytime sedation, and sexual dysfunction make agomelatine an attractive treatment for depression in women, especially during menopause and postmenopause [78].

The results of studies of the efficacy and tolerability of agomelatine allow it to be considered as a first-line drug in the treatment of depression [80].

The literature data presented in this review indicate that there are still a number of issues that require clarification related to the diagnosis and determination of the boundaries of bipolar disorder, the study of gender characteristics of the course of the disease, its clinical manifestations, in particular depression, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of psychotropic drugs, efficacy and tolerability. Further study is needed to optimize care for patients with bipolar disorder.

Further study is needed to optimize care for patients with bipolar disorder.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Credits

Tyuvina N.A. — https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5202-1407; e-mail: [email protected]

Stolyarova A.E. — https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9611-0762; e-mail: [email protected]

Smirnova V.N. — https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5254-6652; e-mail: [email protected]

How to quote:

Tyuvina N.A., Stolyarova A.E., Smirnova V.N. Bipolar affective disorder: gender features of the course and therapy. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakov. 2019;119(12):162-169. https://doi.org/10.17116/jnevro2019119121162

Corresponding author: Tyuvina Nina Arkadievna — e-mail: [email protected]

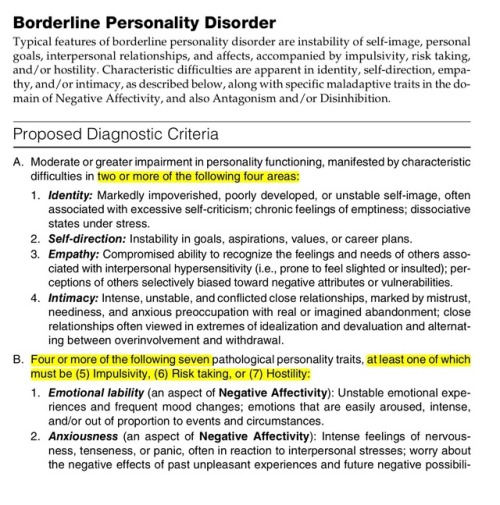

Differential diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder and borderline personality disorder (Joel Paris; 2011)

Recent proposals to expand the boundaries of bipolar disorder to a broad spectrum [5, 6] have led to a fundamentally different concept of bipolarity. The assumption that there are overt mood swings, including cases where irritability is more pronounced than euphoria, has led to the fact that justification for a bipolar diagnosis requires consideration of the construct of "mild bipolarity" (i.e., the type or subclinical form of classical bipolar disorder) [7] . However, the extended spectrum is defined solely on the basis of phenomenological similarities, not etiology or pathogenesis.

The assumption that there are overt mood swings, including cases where irritability is more pronounced than euphoria, has led to the fact that justification for a bipolar diagnosis requires consideration of the construct of "mild bipolarity" (i.e., the type or subclinical form of classical bipolar disorder) [7] . However, the extended spectrum is defined solely on the basis of phenomenological similarities, not etiology or pathogenesis.

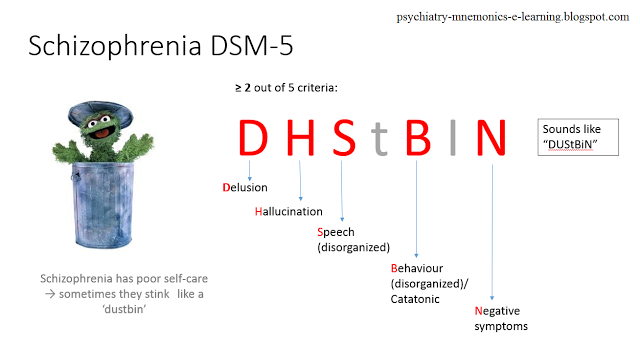

Emil Kraepelin introduced the definition of manic-depressive illness, later renamed bipolar disorder [8]. Since then, manic episodes have always included the classic triad of symptoms: elevated mood, psychomotor agitation, and accelerated thinking. Classically, psychiatrists would not diagnose mania or hypomania in the absence of euphoria.

However, after administration of lithium, it was observed that some patients who were susceptible to the drug developed atypical features, such as irritability. This observation led to questions about whether the state of arousal, irritability and aggression observed in other categories of disorders are symptoms of mania, and whether the classic triad is a necessary condition for diagnosis [5, 6].

The concept of the bipolar spectrum is analogous to the schizophrenic spectrum [9], in which psychopathology can range from severe, traumatic illness to symptoms that appear to be "characteristic". The first to suggest that the bipolar spectrum exists was Kraepelin [8], he described subclinical cases according to the first degree of relatedness of the diseased patients. And Kraepelin's concept has been significantly expanded by some studies confirming that up to 30% of all psychiatric patients have a form of mild bipolarity [10].

The most commonly accepted variant of the classic picture is bipolar II disorder [11]. This diagnosis is described by mood swings from depression to hypomania, not severe mania. This sample of patients is heterogeneous as only a few have a family history of bipolar disorder and not all cases respond to mood stabilizers [12].

In some cases, type II bipolar disorder also meets the criteria for a personality disorder [13]. However, this coincidence may not reflect the true comorbidity and distorts the diagnosis. The criteria for bipolarity can be quite broad, and epidemiological studies sometimes consider all cases where mood swings are observed in both type II bipolar disorder and bipolar spectrum disorder [14].

The criteria for bipolarity can be quite broad, and epidemiological studies sometimes consider all cases where mood swings are observed in both type II bipolar disorder and bipolar spectrum disorder [14].

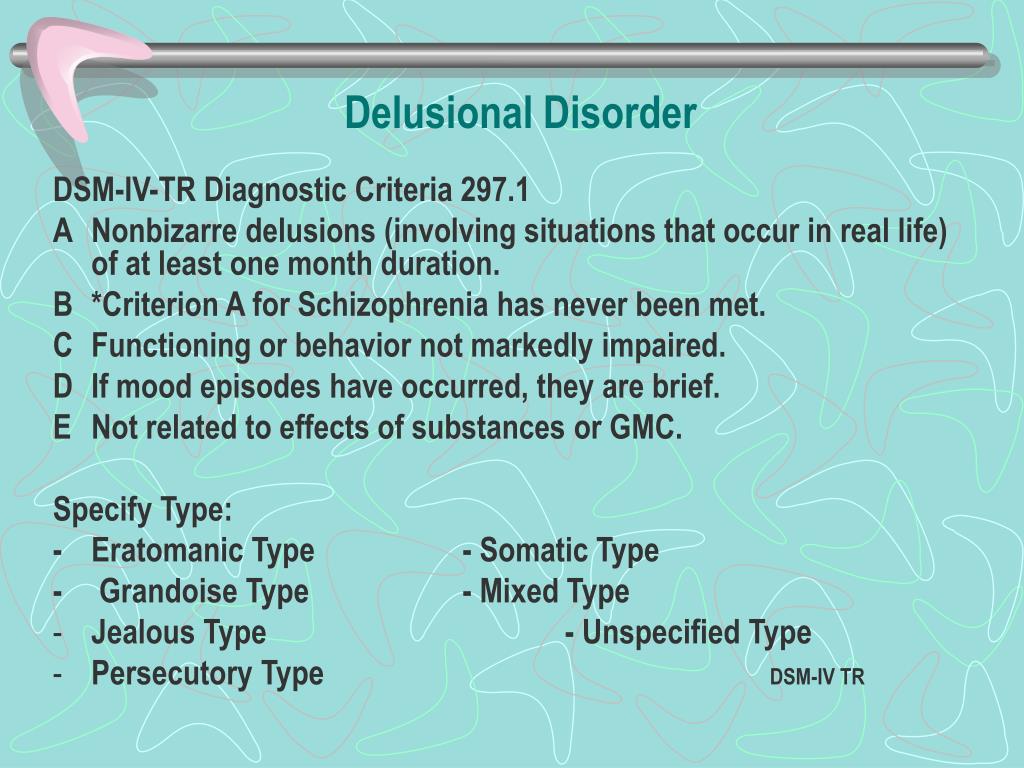

The key is to assess hypomania. The DSM-IV-TR [15] defines this syndrome as "a well-defined period of persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood lasting at least 4 days and distinctly different from normal, non-depressive mood."

Patients must present as at least three of the following symptoms (four if the mood is irritable or not euphoric): heightened self-esteem or grandiosity, reduced need for sleep, the patient is more talkative than usual or insists on continuing to talk, flight of ideas, or a subjective feeling that thinking is speeded up , distractibility, increased activity (in activities or social interactions, at work or school, or in the sexual sphere) or psychomotor agitation, excessive participation in activities that are pleasurable for the patient that have potentially harmful consequences Finally, and this is important, the hypomanic episode must be associated with a clear change in non-symptomatic functioning that is uncharacteristic for a person and should be noticeable to other people. Unlike severe mania, hypomania is not severe enough to cause noticeable impairment in social or occupational functioning, rarely requires hospitalization, and is not associated with psychotic symptoms.

Unlike severe mania, hypomania is not severe enough to cause noticeable impairment in social or occupational functioning, rarely requires hospitalization, and is not associated with psychotic symptoms.

Briefly, hypomanic episodes have requirements based on severity, time scale, and persistence of manifestation. If DSM criteria were strictly followed, no one would be able to diagnose bipolar II disorder in patients whose mood swings last less than 4 days, or in those whose mood returns to normal periodically. It has been suggested that the 4-day rule is conditional [16]. This is true, but then any other rule would be equally arbitrary. In 2013, the DSM-5 [17] adopted the 2-day rule, but this change will not affect the diagnosis of patients who experience mood swings on a daily or hourly basis.

Another variant of bipolar disorder in the DSM-IV-TR is "mixed states" observed for at least a week, during which the patient meets the criteria for major depression and mania. Research in this category is rather weak, and although some cases may be classified as bipolar [18], the category can be used to describe a heterogeneous group of embittered and/or agitated patients.

The DSM-IV-TR also allows for the diagnosis of BAD as "no further specification". Like the other coverage groups in the guideline, the "not further specified" category describes patients with some of the features of the disorder, but not all. In practice, it can be used to diagnose almost any patient with mood swings.

In a formal proposal to describe the spectrum [19], it was suggested that bipolarity could take four main forms:

- bipolar I disorder, Kraepelin's classic manic-depressive disorder;

- bipolar II disorder, depression with unpredictable hypomanic episodes;

- bipolar III disorder, in which hypomanic episodes occur only after taking antidepressants;

- bipolar IV disorder, hyper-rapid cycling (many personality disorders, including childhood mood instability, are included in this category).

Another sentence describes even more forms of bipolar disorder [20]:

- Bipolar I disorder, severe mania;

- bipolar disorder type I½, depression with prolonged hypomania;

- bipolar II disorder, depression with hypomanic episodes;

- bipolar disorder type II½, cyclothymic disorder;

- bipolar III disorder, hypomania due to antidepressants;

- type III½ bipolar disorder, hypomania and/or depression associated with substance use;

- Bipolar IV disorder, depression associated with hyperthymia (i.