Psychological term projection

projection | Definition, Theories, & Facts

Sigmund Freud

See all media

- Related Topics:

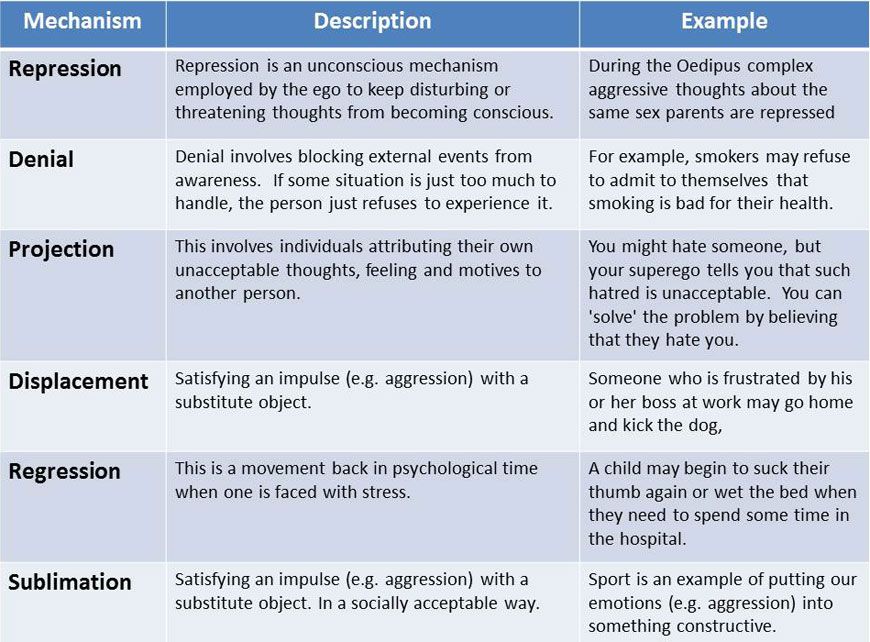

- defense mechanism

See all related content →

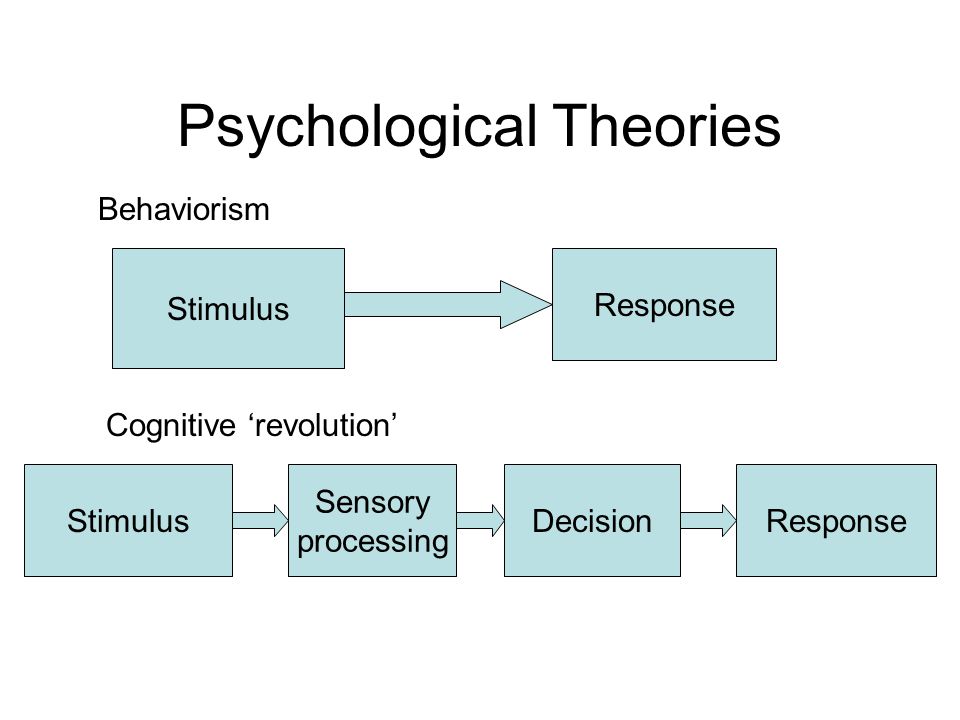

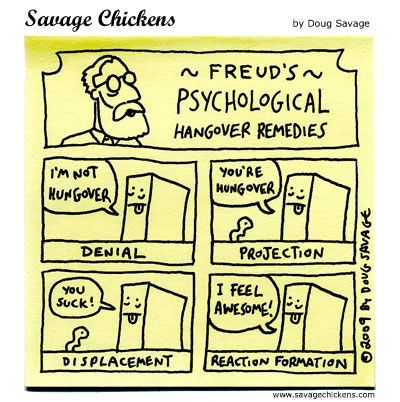

projection, the mental process by which people attribute to others what is in their own minds. For example, individuals who are in a self-critical state, consciously or unconsciously, may think that other people are critical of them. The concept was introduced to psychology by the Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), who borrowed the word projection from neurology, where it referred to the inherent capacity of neurons to transmit stimuli from one level of the nervous system to another (e.g., the retina “projects” to the occipital cortex, where raw sensory input is rendered into visual images). In contemporary psychological science the term continues to have the meaning of seeing the self in the other.

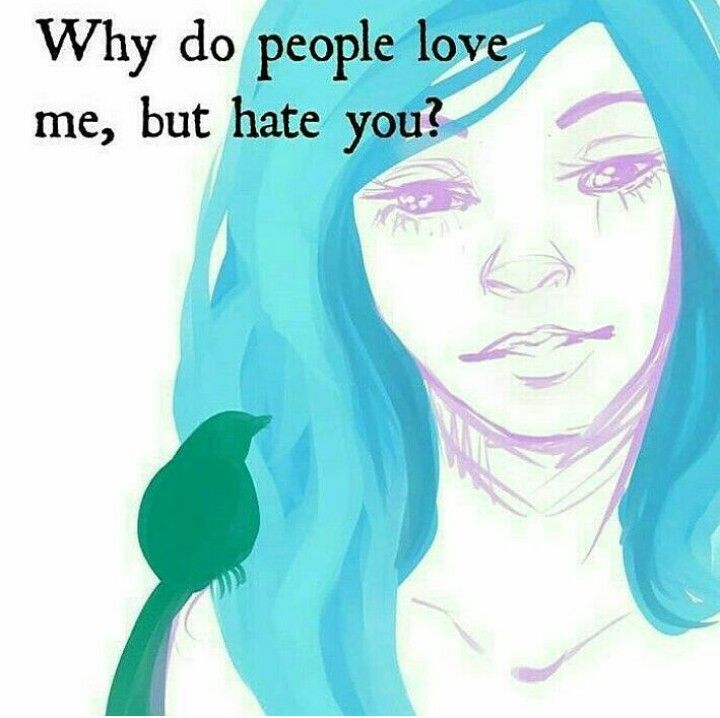

This presumably universal tendency of the human social animal has both positive and negative effects. Depending on what qualities are projected and whether or not they are denied in the self, projection can be the basis of both warm empathy and cold hatred.

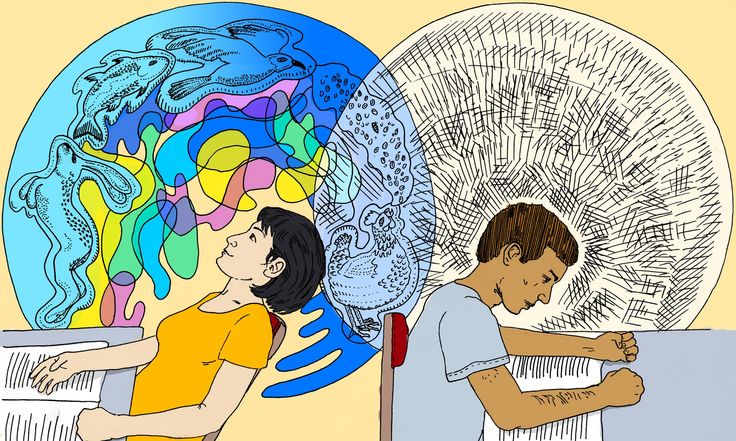

In projection, what is internal is seen as external. People cannot get inside the minds of others; to understand someone else’s mental life, one must project one’s own experience. When someone projects what is consciously true of the self and when the projection “fits,” the person who is the object of projection may feel deeply understood. Thus, a sensitive father infers from his daughter’s facial expression that she is feeling sad; he knows that when he himself is sad, his face is similar. If he names the child’s assumed emotion, she may feel recognized and comforted. Intuition, leaps of nonverbal synchronicity (as when two persons in a relationship suddenly find themselves making similar gestures or thinking of the same image simultaneously), and peak experiences of mystical union (as when one feels perfectly attuned with an idealized other person, such as a romantic partner) involve a projection of the self into the other, often with powerful emotional rewards. Neuroscientific discoveries regarding mirror neurons and right-brain-to-right-brain communication processes (in which intuitive, emotional, nonverbal, and analogical thinking is shared between caregivers and children via intonation, facial affect, and body language) are establishing the neurological bases of such long-noted projective phenomena.

Neuroscientific discoveries regarding mirror neurons and right-brain-to-right-brain communication processes (in which intuitive, emotional, nonverbal, and analogical thinking is shared between caregivers and children via intonation, facial affect, and body language) are establishing the neurological bases of such long-noted projective phenomena.

On the other hand, projection frequently functions as a psychological defense against painful internal states (“I am not the person feeling this; you are!”). When people project aspects of the self that are denied, unconscious, and hated and when they distort the object of projection in the process, projection can be felt as invalidating and destructive. At a social level, racism, sexism, xenophobia, homophobia, and other malignant “othering” mindsets have been attributed at least partly to projection. There is research evidence, for example, that men with notably homophobic attitudes have higher-than-average same-sex arousal, of which they are unaware. Projection of disowned states of mind is also a central dynamic in paranoia as traditionally conceptualized. Paranoid states such as fears of persecution, irrational hatred of an individual or group, consuming jealousy in the absence of evidence of betrayal, and the conviction that a desired person desires oneself (i.e., erotomania, the psychology behind stalking) result from the projection of unconscious negative states of mind (e.g., hostility, envy, hatred, contempt, vanity, sadism, lust, greed, weakness, etc.). In other words, paranoia involves both the disowning of a personal tendency and the conviction that this tendency is “coming at” oneself from external sources.

Projection of disowned states of mind is also a central dynamic in paranoia as traditionally conceptualized. Paranoid states such as fears of persecution, irrational hatred of an individual or group, consuming jealousy in the absence of evidence of betrayal, and the conviction that a desired person desires oneself (i.e., erotomania, the psychology behind stalking) result from the projection of unconscious negative states of mind (e.g., hostility, envy, hatred, contempt, vanity, sadism, lust, greed, weakness, etc.). In other words, paranoia involves both the disowning of a personal tendency and the conviction that this tendency is “coming at” oneself from external sources.

The Austrian-born British psychoanalyst Melanie Klein (1882–1960) wrote about a primal form of projection, “projective identification,” that she assumed to derive from the earliest mental life of children, before they feel psychologically separate from caregivers. Via this process, which has become an important concept in contemporary psychoanalytic thinking, a person tries to expel a state of mind by projecting it but remains identified with what is projected, is convinced of the accuracy of the attribution, and induces in the object of projection the feelings or impulses that have been projected. For example, a man in a rage projects his anger onto his wife, whom he now sees as the angry one. He insists it is her hostility that stimulated his rage, and almost immediately his wife becomes angry. Projective identification exerts emotional pressure that evokes in the other whatever has been projected. Another example: A woman in psychotherapy experiences her therapist’s ending a session on time as a sadistic attack. She loudly berates him for abusing her, accusing him of enjoying hurting her. In response to this denunciation and its misrepresentation of his motives, the normally compassionate therapist notices that he is having sadistic thoughts. The projection has become a self-fulfilling fantasy. Because projective identification is a particularly challenging defense to deal with in psychotherapy, it has spawned an extensive psychoanalytic literature.

For example, a man in a rage projects his anger onto his wife, whom he now sees as the angry one. He insists it is her hostility that stimulated his rage, and almost immediately his wife becomes angry. Projective identification exerts emotional pressure that evokes in the other whatever has been projected. Another example: A woman in psychotherapy experiences her therapist’s ending a session on time as a sadistic attack. She loudly berates him for abusing her, accusing him of enjoying hurting her. In response to this denunciation and its misrepresentation of his motives, the normally compassionate therapist notices that he is having sadistic thoughts. The projection has become a self-fulfilling fantasy. Because projective identification is a particularly challenging defense to deal with in psychotherapy, it has spawned an extensive psychoanalytic literature.

Contrary to widespread professional opinion, however, projective identification is not simply a defense used by people with disorders of development and personality (

see also mental disorders: Personality disorders). It operates in everyday life in numerous subtle ways, many of which are not pathological. For example, when what is projected and identified with involves loving, joyful affects, a group can experience a rush of good feeling. People in love can sometimes read one another’s minds in ways that cannot be accounted for logically. Because such emotional contagion occurs ubiquitously, many contemporary psychoanalysts have reframed as “intersubjective” what was once seen as the patient’s one-way projection onto the therapist. That is, both parties in a therapeutic relationship (or any relationship) inevitably share a mutually determined emotional atmosphere.

It operates in everyday life in numerous subtle ways, many of which are not pathological. For example, when what is projected and identified with involves loving, joyful affects, a group can experience a rush of good feeling. People in love can sometimes read one another’s minds in ways that cannot be accounted for logically. Because such emotional contagion occurs ubiquitously, many contemporary psychoanalysts have reframed as “intersubjective” what was once seen as the patient’s one-way projection onto the therapist. That is, both parties in a therapeutic relationship (or any relationship) inevitably share a mutually determined emotional atmosphere.

Klein’s writing led to a general professional acknowledgment that projection has more primitive and more mature forms. In its earliest expressions, self and other are not well differentiated. In mature projection, the other is understood to have a separate subjective life, with motives that may differ from one’s own. Before age three, children tend to assume that the emotional effect of an action was its intention. When caregivers set unwelcome limits, very young children react with normal, temporary hatred and accuse the parents of hating them. A slightly older child understands that when his mother’s limit-setting angers him, her act does not necessarily mean she is angry with him. Philosophers use the term “theory of mind” to denote this capacity to see others as having independent subjectivities. Contemporary psychoanalytic theorists and researchers refer to it as “mentalization.” Although a benign use of projection is the basis for understanding others’ psychologies, in mentalization there is little distortion of the other person’s mind because there is no automatic equation of it with the mind of the observer.

When caregivers set unwelcome limits, very young children react with normal, temporary hatred and accuse the parents of hating them. A slightly older child understands that when his mother’s limit-setting angers him, her act does not necessarily mean she is angry with him. Philosophers use the term “theory of mind” to denote this capacity to see others as having independent subjectivities. Contemporary psychoanalytic theorists and researchers refer to it as “mentalization.” Although a benign use of projection is the basis for understanding others’ psychologies, in mentalization there is little distortion of the other person’s mind because there is no automatic equation of it with the mind of the observer.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content. Subscribe Now

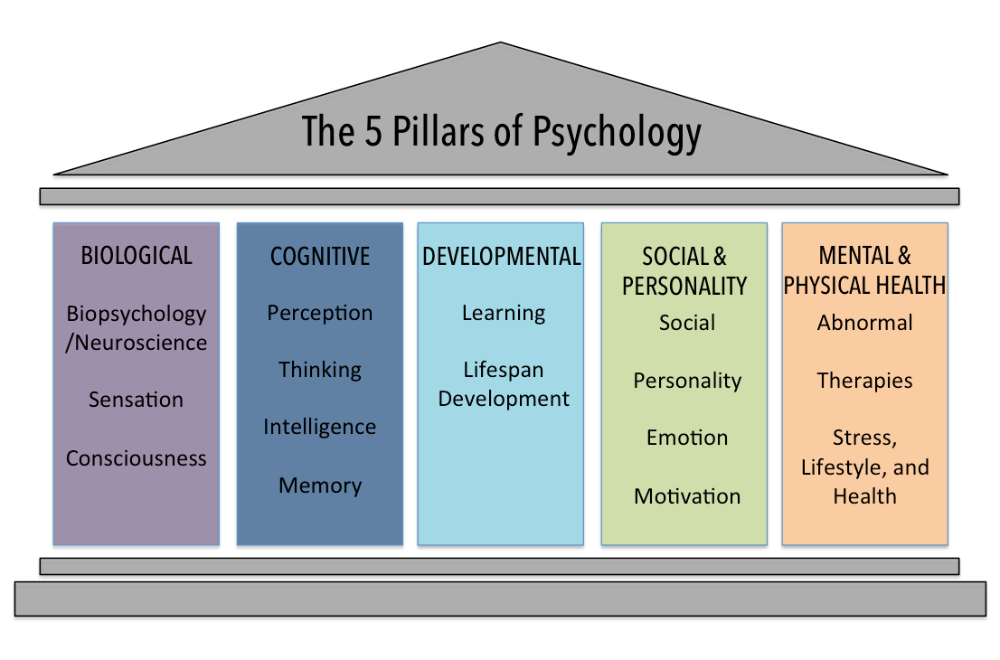

Empirical studies of defense mechanisms have supported clinical observations about projection, including the idea that it is one of many universal psychological defenses that evolve and mature in normal development. Understanding projection has been critically important to psychiatry, clinical psychology, counseling, and the mental health professions generally. It has also been cited as an explanatory principle in political science, sociology, anthropology, and other social sciences.

Understanding projection has been critically important to psychiatry, clinical psychology, counseling, and the mental health professions generally. It has also been cited as an explanatory principle in political science, sociology, anthropology, and other social sciences.

Nancy McWilliams

Projection | Psychology Today

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

Projection is the process of displacing one’s feelings onto a different person, animal, or object. The term is most commonly used to describe defensive projection—attributing one’s own unacceptable urges to another. For example, if someone continuously bullies and ridicules a peer about his insecurities, the bully might be projecting his own struggle with self-esteem onto the other person.

The concept emerged from Sigmund Freud’s work on defense mechanisms and was further refined by his daughter, Anna Freud, and other prominent figures in psychology.

Contents

- What Is Projection?

- Projection in Everyday Life

- Projection in Therapy

What Is Projection?

Unconscious discomfort can lead people to attribute unacceptable feelings or impulses to someone else to avoid confronting them. Projection allows the difficult trait to be addressed without the individual fully recognizing it in themselves.

Who developed the concept of projection?

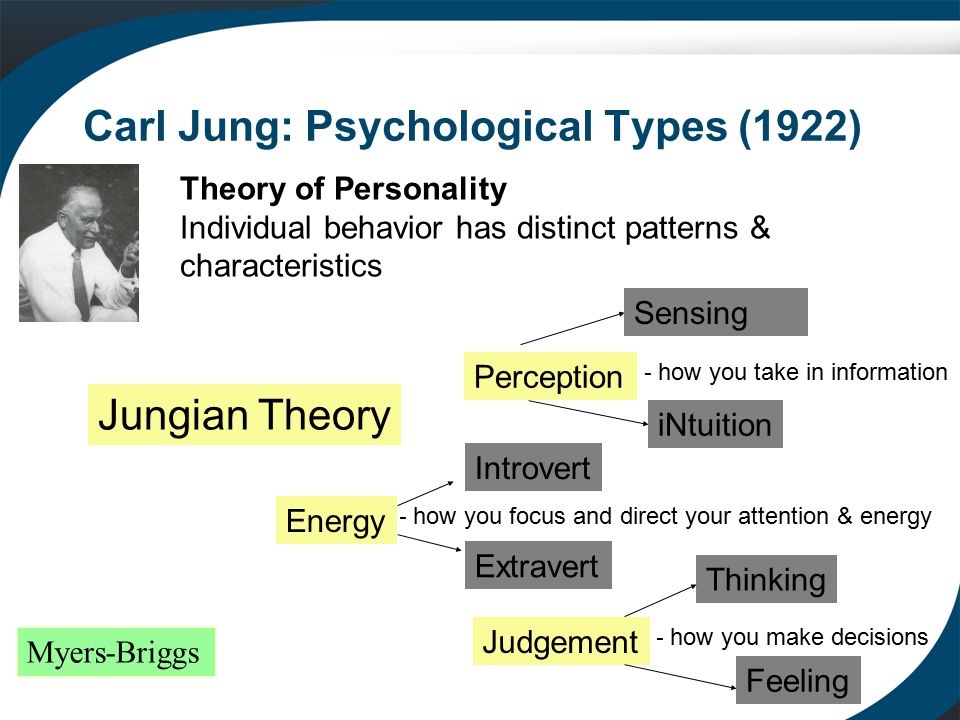

Freud first reported on projection in an 1895 letter, in which he described a patient who tried to avoid confronting her feelings of shame by imagining that her neighbors were gossiping about her instead. Psychologists Carl Jung and Marie-Louise von Franz later argued that projection is also used to protect against the fear of the unknown, sometimes to the projector’s detriment. Within their framework, people project archetypal ideas onto things they don’t understand as part of a natural response to the desire for a more predictable and clearly-patterned world.

Psychologists Carl Jung and Marie-Louise von Franz later argued that projection is also used to protect against the fear of the unknown, sometimes to the projector’s detriment. Within their framework, people project archetypal ideas onto things they don’t understand as part of a natural response to the desire for a more predictable and clearly-patterned world.

More recent research has challenged Freud’s hypothesis that people project to defend their egos. Projecting a threatening trait onto others may be a byproduct of the mechanism that defends the ego, rather than a part of the defense itself. Trying to suppress a thought pushes it to the mental foreground, psychologists have argued, and turns it into a chronically accessible filter through which one views the world.

What’s an example of projection?

An example of projection would be the following: A married man who is attracted to a female coworker, but rather than admit this to himself, he might accuse her of flirting with him. Another would be a woman wrestling with the urge to steal, who comes to believe that her neighbors are trying to break into her home.

Another would be a woman wrestling with the urge to steal, who comes to believe that her neighbors are trying to break into her home.

Why do people project?

People tend to project because they have a trait or desire that is too difficult to acknowledge. Rather than confronting it, they cast it away and onto someone else. This functions to preserve their self-esteem, making difficult emotions more tolerable. It’s easier to attack or witness wrongdoing in another person than confront that possibility in one's own behavior. How a person acts toward the target of projection might reflect how they really feel about themselves.

Is projection conscious or unconscious?

Projection is thought to be an unconscious process that protects the ego from unacceptable thoughts and impulses. Attributing those tendencies to others allows the person to place themselves above and beyond those urges, while still being able to observe them from afar. Although this occurs unconsciously, these patterns can be brought to conscious awareness, especially with the help of a therapist.

Although this occurs unconsciously, these patterns can be brought to conscious awareness, especially with the help of a therapist.

What is projective identification?

Projective identification occurs when the target of projection identifies with and expresses the feelings projected onto them. This represents a deeper stage of the distortions raised by projection, one that often occurs in relationships. For instance, a man could displace his own feelings of frustration towards a distant parent onto a romantic partner, who then withdraws emotionally after an argument.

Projection in Everyday Life

Projection can occur in a variety of contexts, from an isolated incident with a casual acquaintance to a regular pattern in a romantic relationship. But learning to recognize and respond to projection can help people understand and navigate social conflict.

How can you tell if you’re projecting?

When your fears or insecurities are provoked, it’s natural to occasionally begin projecting. If you think you might be projecting, the first step is to step away from the conflict. Time away will allow your defensiveness to fade so that you can think about the situation rationally. Then you can 1) Describe the conflict in objective terms 2) Describe the actions that you took and the assumptions you made and 3) Describe the actions the other person took and the assumptions they made in order. These questions can help you explore whether and why you may have been projecting.

If you think you might be projecting, the first step is to step away from the conflict. Time away will allow your defensiveness to fade so that you can think about the situation rationally. Then you can 1) Describe the conflict in objective terms 2) Describe the actions that you took and the assumptions you made and 3) Describe the actions the other person took and the assumptions they made in order. These questions can help you explore whether and why you may have been projecting.

How can you tell if someone is projecting on you?

If someone has an unusually strong reaction to something you say, or there doesn’t seem to be a reasonable explanation for their reaction, they might be projecting their insecurities onto you. Taking a step back, and determining that their response doesn’t align with your actions, may be a signal projection.

A harmful consequence of continual projection is when the trait becomes incorporated into one’s identity. For example, a father who never built a successful career might tell his son, “You won’t amount to anything” or, “Don’t even bother trying.” He is projecting his own insecurities onto his son, yet his son might internalize that message, believing that he will never be successful.

For example, a father who never built a successful career might tell his son, “You won’t amount to anything” or, “Don’t even bother trying.” He is projecting his own insecurities onto his son, yet his son might internalize that message, believing that he will never be successful.

Although it’s difficult to do so, individuals who experience this can try to remember that the criques are about the other person, and to be confident in who they are outside of that relationship.

How does projection affect romantic relationships?

A common source of projection in romantic relationships emerges when unconscious feelings toward a parent are projected onto the person’s partner. If the partner then identifies with and expresses the feelings projected onto them, projective identification is at play.

Signs of projective identification in a relationship include having the same fight over and over again, feeling upset with your partner but not knowing why, and confusion about your reaction or your partner’s reaction to a situation. Couples can overcome projective identification by recognizing it, slowing down in conflicts, checking to make sure that they understand each other correctly, and considering couples therapy if needed.

Couples can overcome projective identification by recognizing it, slowing down in conflicts, checking to make sure that they understand each other correctly, and considering couples therapy if needed.

How do narcissists use projection?

Narcissistic people often resort to projection to protect their self-image. Complaining about how someone else is so “showy” or “always needs attention” is one example of how a narcissist might project. They may also blame others for things that have gone wrong, rather than taking responsibility themselves. As the narcissist projects more shame and criticism onto another person, that individual’s self-doubt often grows, leading to a self-reinforcing cycle.

How do you respond to projection?

Setting boundaries can help you respond to projection. Responding with clear statements such as “I disagree” or “I don’t see it that way” can deflect the projection and may prompt the person to reflect or take responsibility. It can also prevent you from internalizing unfair criticism or blame. But if the person continues to project, and seems unable to move forward, it may be necessary to remove yourself from the conversation.

It can also prevent you from internalizing unfair criticism or blame. But if the person continues to project, and seems unable to move forward, it may be necessary to remove yourself from the conversation.

Projection in Therapy

Projection can reveal hidden insecurities or beliefs that are valuable to explore in therapy. It also relates to the phenomenon of transference, in which a patient transfers feelings he or she has toward another important figure in their life onto a therapist. While projection can occur in different contexts, transference is primarily understood through a therapeutic lens. (For more, see Transference.)

While psychodynamic and psychoanalytic therapists are more likely than others to invoke projection as a behavior of note, therapists trained in all modalities are familiar with the construct. Some may discuss a person misattributing or misunderstanding their own biases, without labeling such behavior "projection. "

"

How does projection work in therapy?

Through their conversations, a therapist may observe that a patient seems to be projecting, either onto the therapist or toward other people in the patient’s life. For example, a therapist might realize that a patient continuously posits that their partner is having an affair, with no evidence. The therapist might explore whether the patient is secure in the relationship or is perhaps the one struggling to remain faithful. Projection can be an opportunity to identify difficult emotions that need to be processed.

How do therapists respond to projection?

If a therapist suspects that a patient is projecting—either onto the therapist or onto other people in the patient’s life—they will likely explore the patient’s reaction. Understanding why the patient is reacting to the therapist with such a strong emotion, or misinterpreting a therapist’s statements, can help reveal underlying relationship challenges that should be discussed and resolved.

Essential Reads

Recent Posts

Projection - Psychologos

Projection - (from Latin projectio - throwing forward) - a psychological mechanism, first considered by Z. Freud.

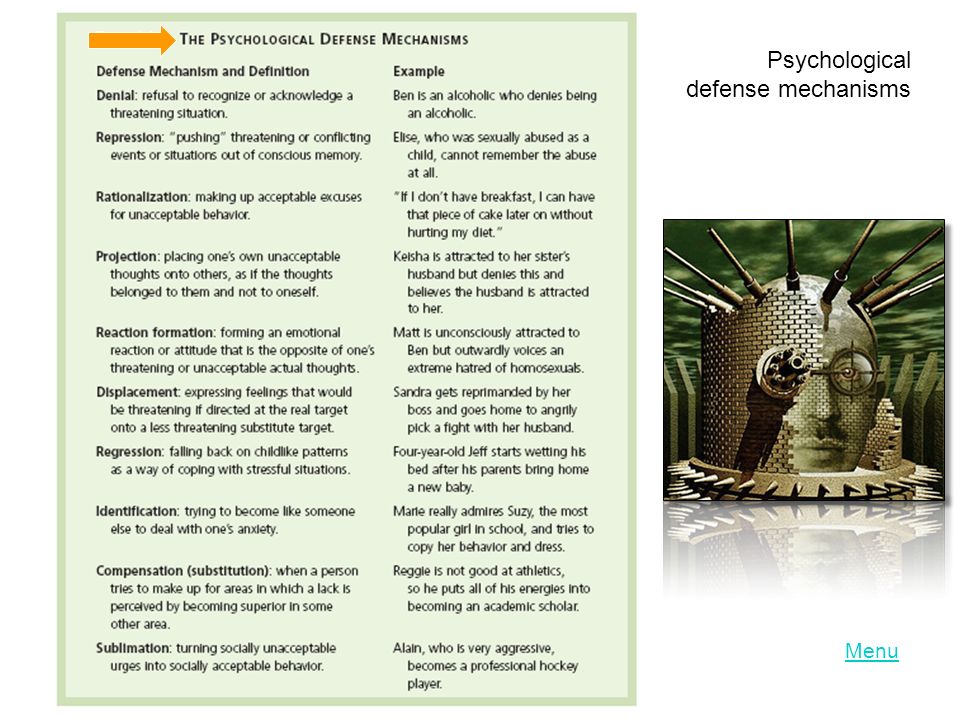

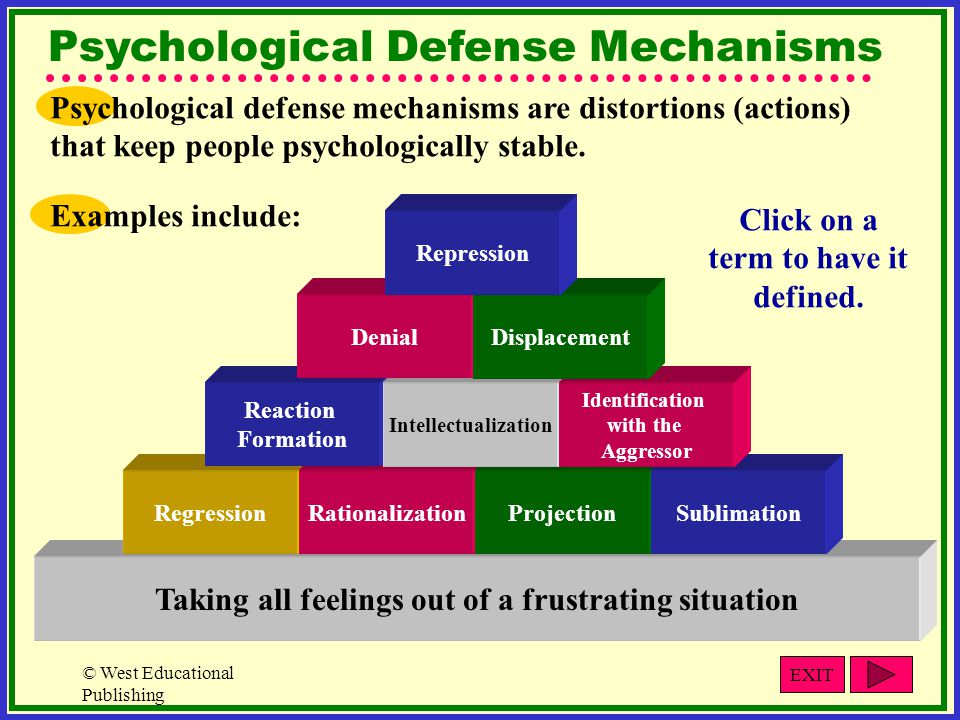

- In classical psychoanalysis, the process by which an individual's own traits, emotions, attitudes, etc., are attributed to someone else. Interruption of contact with the environment. This is accompanied by a denial that he himself has these feelings or tendencies. In speech, it looks like replacing the pronoun “I” with the pronoun “you” (or “they”, if we are talking about a whole group of people). “They don't like me,” thinks the speaker, nervous before a public speech, “You're mad at me,” complains the one who is unable to recognize and accept his own aggression. The projection performs the functions of a defense mechanism, protecting the individual from anxiety, indicates the presence of some suppressed basic conflict;

- In other psychodynamic theories, the process of involuntary attribution of the subjective processes of one person to others.

This process is regarded as a normal process of mental development, not necessarily reflecting neurotic tendencies;

This process is regarded as a normal process of mental development, not necessarily reflecting neurotic tendencies; - Perception of environmental events and stimuli (especially ambiguous ones) in terms of one's own expectations, needs, desires, etc. This value is completely neutral with respect to the pathological aspect of the projection and forms the basis for the use of projective techniques.

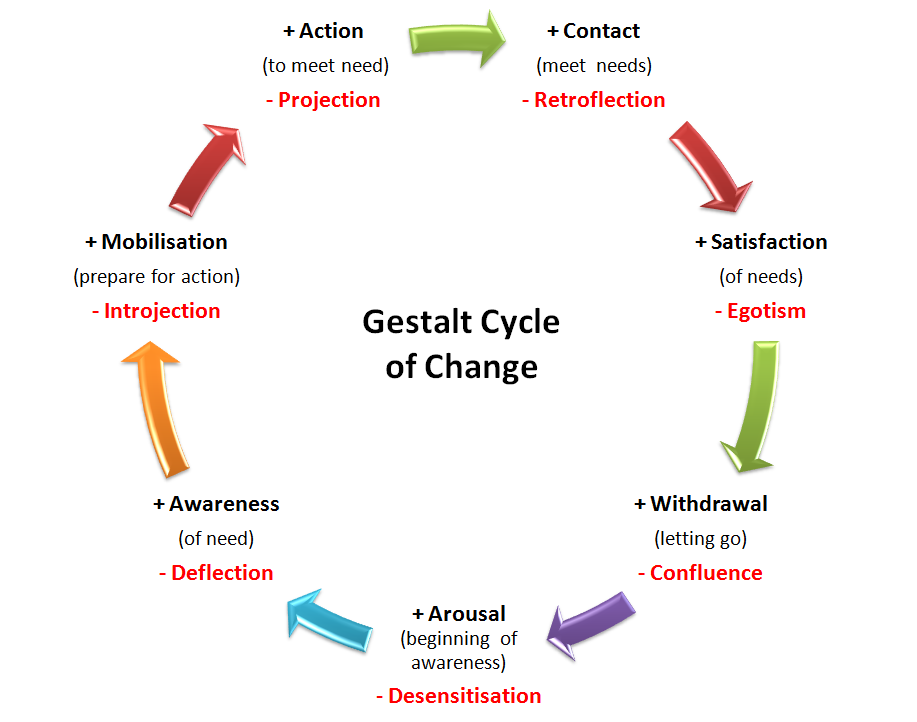

Projection (from Frederick Perls' Witness to Therapy)

The opposite of introjection is projection. If introjection is the tendency to take responsibility for what is really part of the environment, then projection is the tendency to make the environment responsible for what comes from the person himself. An example of an extreme case of projection would be paranoia, clinically characterized by the presence of a well-organized delusional system in the patient. The paranoid usually turns out to be a highly aggressive person; unable to take responsibility for his own illusions, desires and feelings, the paranoid ascribes them to objects or people in his environment. His conviction that he is being persecuted is in fact a statement that he would like to be persecuted by others. But projection does not exist in such extreme forms; it is necessary to carefully distinguish between projection as a pathological process, and thinking through assumptions, which can be normal and healthy. Planning and anticipation, searching and maneuvering in chess and many other activities involve observing and making assumptions about the outside world. But these assumptions are understood as assumptions. When a chess player thinks several moves ahead, he makes a series of assumptions about his opponent's mental processes, as if to say, "If I were him, I would do such-and-such." But he realizes that he is making assumptions that will not necessarily be consistent with what guides his opponent's behavior, and he knows that these are his own assumptions.

His conviction that he is being persecuted is in fact a statement that he would like to be persecuted by others. But projection does not exist in such extreme forms; it is necessary to carefully distinguish between projection as a pathological process, and thinking through assumptions, which can be normal and healthy. Planning and anticipation, searching and maneuvering in chess and many other activities involve observing and making assumptions about the outside world. But these assumptions are understood as assumptions. When a chess player thinks several moves ahead, he makes a series of assumptions about his opponent's mental processes, as if to say, "If I were him, I would do such-and-such." But he realizes that he is making assumptions that will not necessarily be consistent with what guides his opponent's behavior, and he knows that these are his own assumptions.

In contrast, a sexually inhibited woman who complains about being hit on by everyone, or a cold, aloof, arrogant man who accuses people of being hostile to him are examples of neurotic projection. In these cases, people make assumptions based on their own fantasy, not realizing that these are only assumptions. Moreover, they are unaware of the origin of their own assumptions.

In these cases, people make assumptions based on their own fantasy, not realizing that these are only assumptions. Moreover, they are unaware of the origin of their own assumptions.

Artistic creativity also requires some assumptions and projections. The writer often literally projects himself into his characters, becomes them while he writes about them. But, unlike the projecting neurotic, he does not lose ideas about himself. He knows where he himself ends and his characters begin, even if in the process of creation itself he loses his sense of boundaries and becomes someone else.

The neurotic uses the mechanism of projection not only in relation to the external world; he also uses it in relation to himself. He alienates from himself not only his own impulses, but also the parts of himself in which these impulses arise. He endows them with an objective, so to speak, existence, which can make them responsible for his difficulties and help him ignore the fact that they are parts of himself. Instead of an active attitude to the events of his own life, the projecting subject becomes a passive object, a victim of circumstances.

Instead of an active attitude to the events of his own life, the projecting subject becomes a passive object, a victim of circumstances.

When a chorister complains about his bladder causing him trouble, this is a perfect example of projection. Here the ugly “it” raises its head, and our hero is almost a victim of his own bladder. “It just happens to me; I have to endure it,” he says. We are witnessing the emergence of a small fragment of paranoia. Just as an introjector might be asked who is speaking and the answer is "they," so the projector should be reminded, "It's your own bladder, it's you who needs to urinate." - When a projector says "it" or "they", he usually means "I".

Thus, in the projection, we shift the boundary between ourselves and the rest of the world a little “in our favor”, which gives us the opportunity to relieve ourselves of responsibility, denying that we own those aspects of the personality that we find it difficult to reconcile with, which seem unattractive or offensive to us .

Also, projection is usually the result of our introjects causing us to feel alienated and self-contemptuous. Because our chorister has introjected the notion that good manners are more important than the satisfaction of pressing personal needs, since he has introjected the conviction that one should "bear it all smiling," he is forced to project or even expel from himself those impulses that are contrary to his external activities. It is not he who feels the need to urinate; he's a good boy, he wants to stay with the band and keep singing. Urination is demanded by this nasty, naughty bladder, which, as luck would have it, ended up in him, which he considers to be an "introject" - an alien element, forcibly introduced into him against his will.

The projecting neurotic, like the introjector, is unable to distinguish between the facets of his own integral personality that really belong to him and that which is imposed on him from outside. He regards his introjects as himself, and he regards those parts of himself that he would like to get rid of as undigested and inedible introjects. Through projection, he hopes to free himself from imaginary "introjects" that are in reality not introjects at all, but aspects of himself. The introjecting personality, which is a battlefield between warring unassimilated ideas, gets a parallel in the form of a projecting personality, which makes the world the arena of the battle of its personal conflicts. An overly cautious, suspicious person who tells you that he would like to have friends, would like to be loved, but at the same time adds that "no one can be trusted, everyone is just waiting to grab something from you" - a typical example of a projection.

Through projection, he hopes to free himself from imaginary "introjects" that are in reality not introjects at all, but aspects of himself. The introjecting personality, which is a battlefield between warring unassimilated ideas, gets a parallel in the form of a projecting personality, which makes the world the arena of the battle of its personal conflicts. An overly cautious, suspicious person who tells you that he would like to have friends, would like to be loved, but at the same time adds that "no one can be trusted, everyone is just waiting to grab something from you" - a typical example of a projection.

Projection in psychology: examples, principles, mechanism

The world of human relations is complex and, unfortunately, does not always bring us joy. There are often moments that cause resentment and bitterness, irritation or disappointment. These are heavy feelings that I would like to get rid of, and a person has unconsciously learned to protect his psyche from excessive overload and negativity. Z. Freud was the first to study and describe psychological defense mechanisms, having determined that projection is one of the most ancient and primitive mechanisms.

Z. Freud was the first to study and describe psychological defense mechanisms, having determined that projection is one of the most ancient and primitive mechanisms.

CONTENTS

- 1 What is projection

- 1.1 How it works

- 1.2 Projection and empathy

- 2 Types of projection

- 6

- 3 Projection pros and cons

What is projection

Do you know how a projector works? It transfers the image from the film to the screen. Also, a person often transfers, projects his feelings, thoughts, desires onto others. Most often these are unpleasant thoughts and desires. Shame and guilt are difficult experiences, and a person seeks to get rid of them so as not to injure his psyche. Moreover, he does not just take his sins and dark thoughts out of his consciousness, but gives them to other people. So it’s easier for him - no need to blame yourself, because others are no better, and even worse.

Thus, the most jealous are always husbands who themselves are not averse to cheating on their wife.

But since they have such thoughts and desires, should a woman have them too? And this has its own, albeit perverted, logic. And the wife who accuses her husband of spending extra on “his whims and toys” is not very economical herself. She really wants these shoes or a blouse, but her husband is no better than her. And when we condemn our neighbors or colleagues, we remember, first of all, those unpleasant qualities that are inherent in ourselves.

But since they have such thoughts and desires, should a woman have them too? And this has its own, albeit perverted, logic. And the wife who accuses her husband of spending extra on “his whims and toys” is not very economical herself. She really wants these shoes or a blouse, but her husband is no better than her. And when we condemn our neighbors or colleagues, we remember, first of all, those unpleasant qualities that are inherent in ourselves. You say this is bad and I never do that. No, don't be fooled, everyone does it, and so do you.

How it works

The protective mechanism of projection is inherent in all people and is formed in early childhood. It is born from the prohibitions that society dictates to us. In the process of upbringing, ideas about good and bad, about what is permitted and unacceptable, are formed and fixed in the mind. The child very early begins to understand that it is bad to show aggression, offend the weak, insult other people, and take away toys.

The older a person becomes, the more prohibitions society dictates to him. They create conditions for negative experiences, because even wishing for the forbidden is bad, unacceptable. And a person seeks to protect himself from these unpleasant emotions, to get out of the internal conflict between the desired and the permissible. So the well-known reaction arises: “You yourself (a), to blame (a)!”

The older a person becomes, the more prohibitions society dictates to him. They create conditions for negative experiences, because even wishing for the forbidden is bad, unacceptable. And a person seeks to protect himself from these unpleasant emotions, to get out of the internal conflict between the desired and the permissible. So the well-known reaction arises: “You yourself (a), to blame (a)!” Projection is one of the oldest types of psychological defense, and its mechanism is simple. It always works according to the following scheme:

- The individual feels discomfort, shame, irritation, which are caused by forbidden desires and his behavior, which is wrong from the point of view of social norms.

- In an effort to get rid of negative emotions, a person takes unacceptable desires and urges beyond the limits of his consciousness.

- Attributes these motives to other people so that he himself would not be so ashamed, because "everyone is like that, everyone does it.

"

"

Therefore, the "old maids", preoccupied with their "wrong" thoughts and desires, are so energetically fighting the "debauchery" of the youth. And a drunkard in moments of sobriety with anger stigmatizes an alcoholic neighbor.

The projection mechanism adds fuel to the fire of inter-ethnic conflicts, because most often representatives of one nation accuse their enemies of sins inherent in themselves. And the more these sins, the more aggressive people become. Most often, we blame those whom we ourselves have offended. Why? To not be ashamed and not to feel guilty.

The people who most loudly accuse officials of stealing are those who themselves would not mind warming their hands, but do not have this opportunity. And rejecting their own desires, these accusers project them onto those who have such an opportunity.

Projection and empathy

Projection is connected not only with shameful thoughts and antisocial desires. The process of transferring emotional states underlies such an important socio-psychological phenomenon as empathy.

Empathy in psychology refers to the ability of a person to experience the same feelings as his partner. This is compassion, empathy, which is based on personal emotional experience. It is this experience that the individual transfers to other people, imagining how they should feel in a familiar situation. Therefore, the suffering or joy of another can only be understood by one who himself suffered and rejoiced.

Empathy in psychology refers to the ability of a person to experience the same feelings as his partner. This is compassion, empathy, which is based on personal emotional experience. It is this experience that the individual transfers to other people, imagining how they should feel in a familiar situation. Therefore, the suffering or joy of another can only be understood by one who himself suffered and rejoiced. Without the ability to project one's own emotional experience, mutual understanding is impossible. Although the projection does not always reflect the objective state of affairs. We can empathize with a person, think how bad he is, because in a similar situation it was very difficult for us. But this does not mean that the person is really suffering. People are different, and the circumstances in which they find themselves are also different. But the more emotionally close individuals are, the more accurately they understand each other's state.

Views

The manifestations of projection in our lives and in our relationships with other people are varied.

Usually, there are 4 main types of it:

Usually, there are 4 main types of it: - Attributive projection is based on attributing by an individual the motives of his behavior to other people. Usually these are urges condemned by society or unacceptable by the person himself. (“Greedy!” the child shouts to a peer who does not want to treat him with candy).

- The complementary projection is somewhat opposite to the attributive one and manifests itself in ascribing to oneself qualities that are opposite to those that are rejected. (“I am strong and brave, and you are just a coward and a weakling!”).

- Rational - this is an excuse for one's mistakes and failures by blaming others for some shortcomings, weaknesses, unprofessionalism. (“The project would have been successful if such mediocrity and lazy people did not work with me in the team.” “We would have an ideal marriage if my husband cared more about the family”).

- Autistic projection is the projection of one's needs into the outside world.

It is well illustrated by the saying: "A fisherman sees a fisherman from afar." A hungry man first of all pays attention to food, and a woman who has survived her husband's betrayal sees only traitors and traitors among the surrounding men. She simply does not notice others.

It is well illustrated by the saying: "A fisherman sees a fisherman from afar." A hungry man first of all pays attention to food, and a woman who has survived her husband's betrayal sees only traitors and traitors among the surrounding men. She simply does not notice others.

Quite often different types of projection interact in human behavior and his perception of the surrounding world. This is especially true for people who are insecure, weighed down by complexes and feelings of guilt.

Minuses and pluses of projection

Although this psychological defense refers to the natural reactions of our psyche to difficult social situations, its minuses are obvious and visible, one might say, to the naked eye. These include the following consequences of using projection:

- distortion of reality – we see not what is actually there, but what we would like to see;

- inadequate assessment of other people's behavior;

- interpersonal conflicts due to attributing our own sins to partners;

- Hiding his shortcomings behind the projection, a person does not seek to get rid of them.

However, the projection is not in vain attributed to the mechanisms of psychological defense. Removal from the consciousness of those thoughts and motives that the person himself considers harmful, bad, helps him to cope with the internal conflict. Otherwise, this conflict could lead to the development of such diseases as neurosis, psychosis, and depression. After all, you see, it’s hard to constantly blame only yourself. The fact that the projection protects a person from destructive feelings of guilt is a definite plus.

The second advantage is the role of projection in empathy, as discussed above. Thanks to this mechanism, the mother understands how the child feels, who was not bought the desired toy, and the teacher knows what the student who received a deuce is going through. Without projection, the world would turn into a bunch of callous, insensitive and self-absorbed egoists.

Projection, like other psychological protection, is necessary for us, as it protects the psyche from traumatic experiences and helps to build relationships with others.

Learn more

- 3 Projection pros and cons