Post traumatic growth definition

Growth after trauma

As Kay Wilson struggled to make her way through a Jerusalem forest after being repeatedly stabbed by a Palestinian terrorist, she distracted herself from her agony by playing the song "Somewhere Over the Rainbow" in her mind, composing a new piano arrangement while she fought for breath and forced herself to put one bare foot in front of the other.

Wilson, then 46, had been working as a tour guide when, on Dec. 18, 2010, she and a friend were ambushed by terrorists. Wilson witnessed her friend's murder and was herself viciously stabbed with a machete, ultimately playing dead as her attacker plunged his knife into her chest a final time.

She eventually recovered from her severe physical wounds and is healing from her psychological trauma. She now speaks to global audiences about her survival, hoping to "dispel hatred, whether toward Arabs or Jews."

The work "helps me make meaning out of something so senseless," says Wilson, who is also writing a book about her experiences.

After the attack, Wilson had flashbacks and deep survivor's guilt. But like many people who have survived trauma, she has found positive change as well—a new appreciation for life, a newfound sense of personal strength and a new focus on helping others.

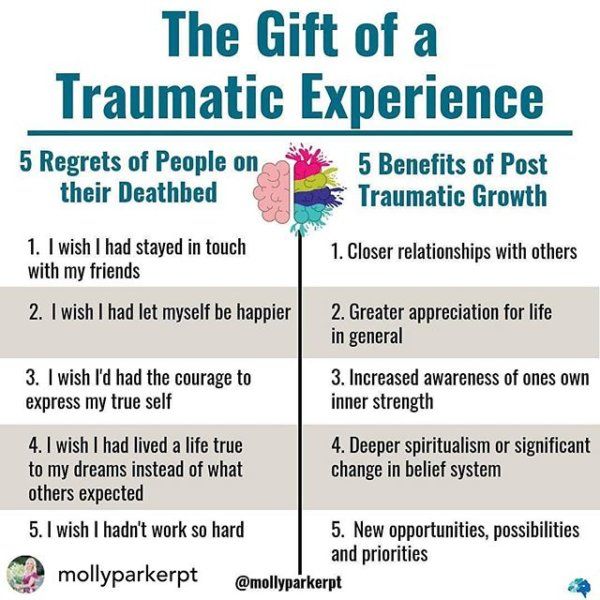

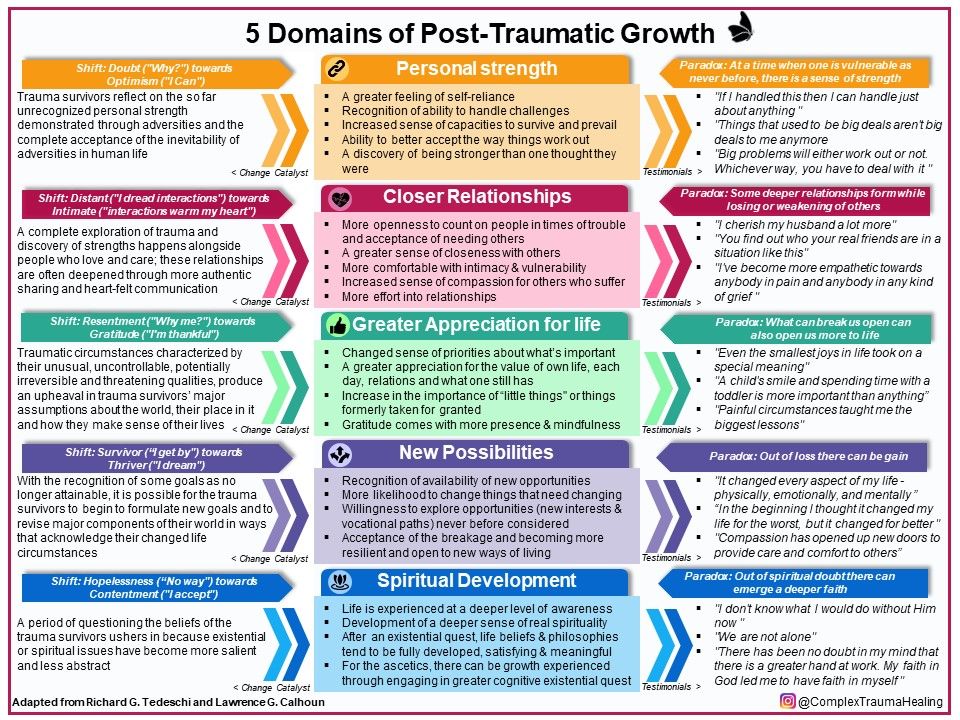

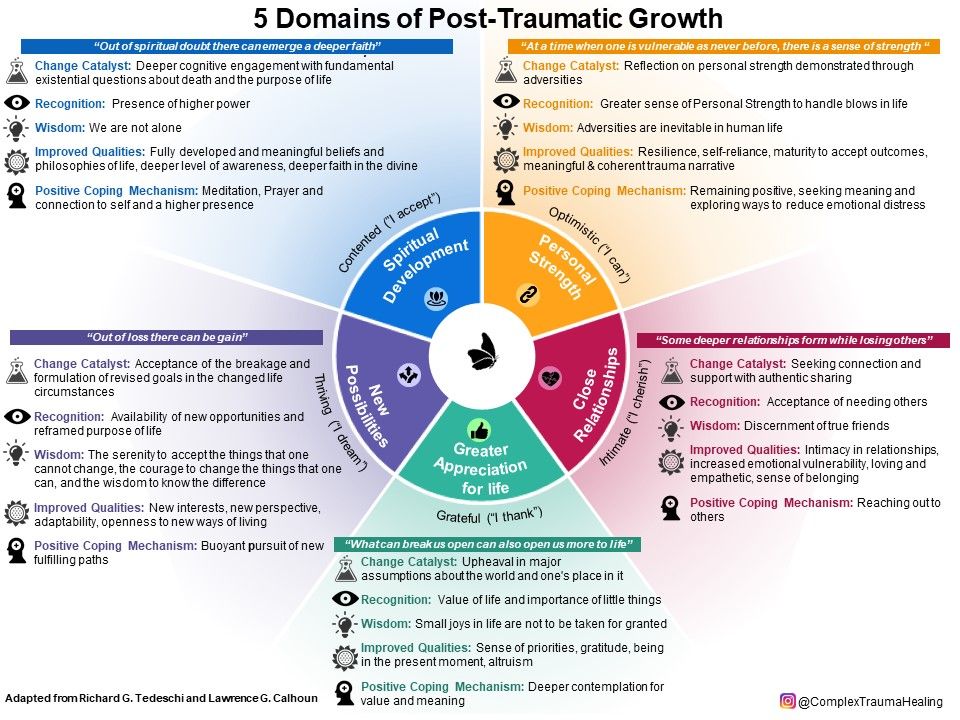

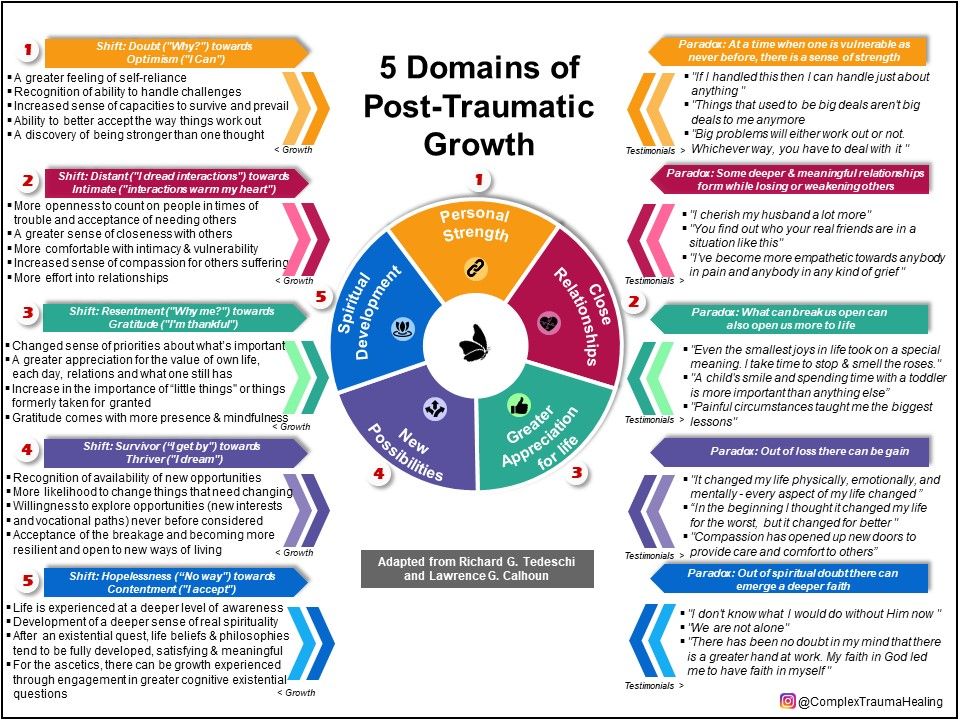

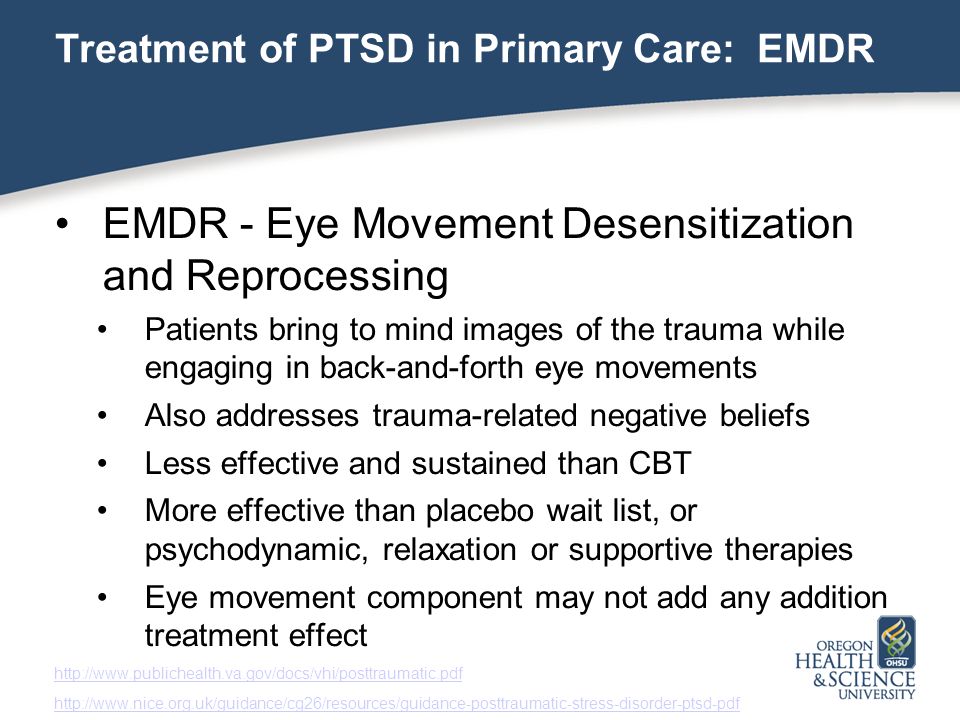

Post-traumatic growth (PTG) is a theory that explains this kind of transformation following trauma. It was developed by psychologists Richard Tedeschi, PhD, and Lawrence Calhoun, PhD, in the mid-1990s, and holds that people who endure psychological struggle following adversity can often see positive growth afterward.

"People develop new understandings of themselves, the world they live in, how to relate to other people, the kind of future they might have and a better understanding of how to live life," says Tedeschi.

How can clinicians use PTG theory to help patients? How has new research helped refine understanding of it? Here's a look at developments in the field.

Signs of post-traumatic growth

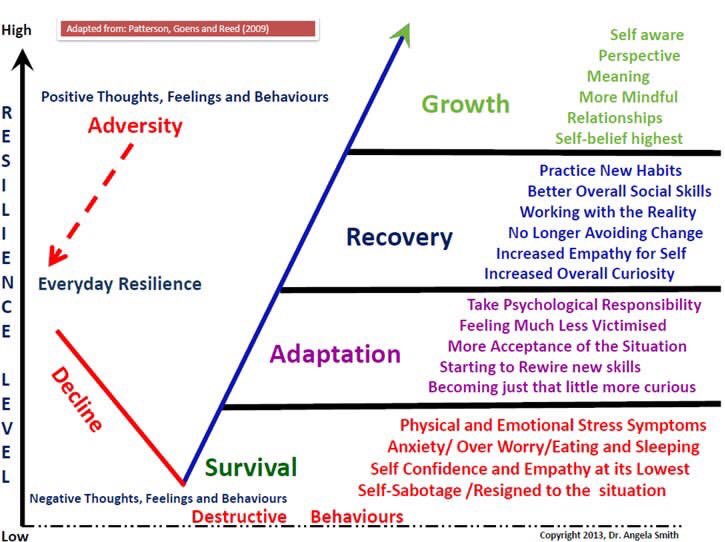

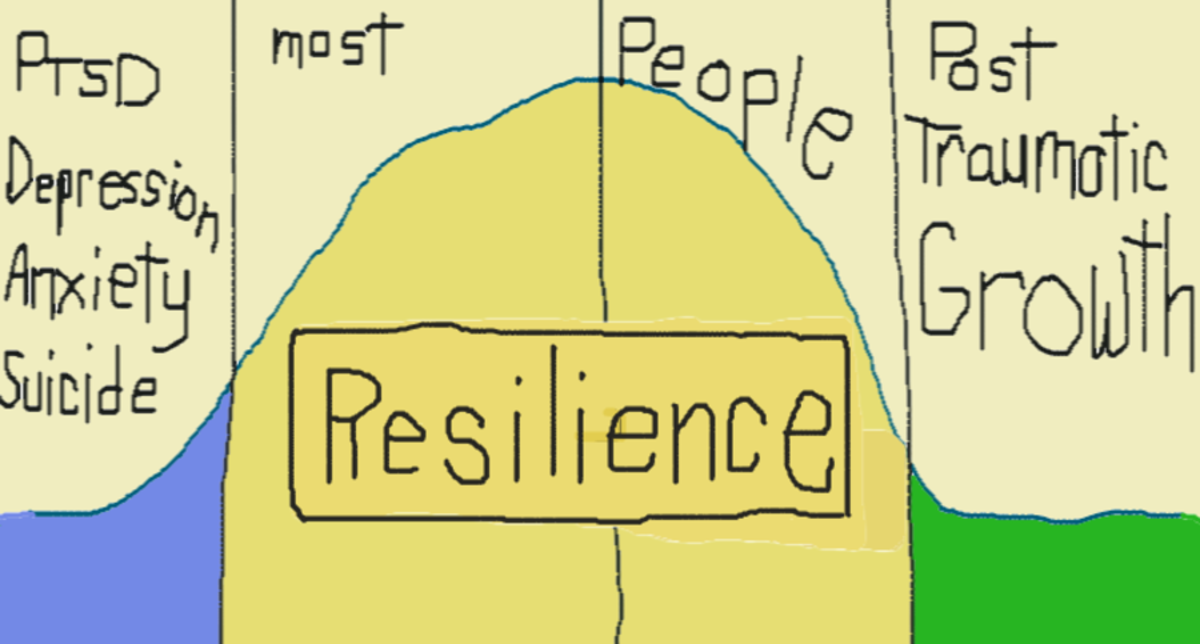

PTG can be confused with resilience, but the two are different constructs (see "The post-traumatic growth inventory" below).

"PTG is sometimes considered synonymous with resilience because becoming more resilient as a result of struggle with trauma can be an example of PTG—but PTG is different from resilience, says Kanako Taku, PhD, associate professor of psychology at Oakland University, who has both researched PTG and experienced it as a survivor of the 1995 Kobe earthquake in Japan.

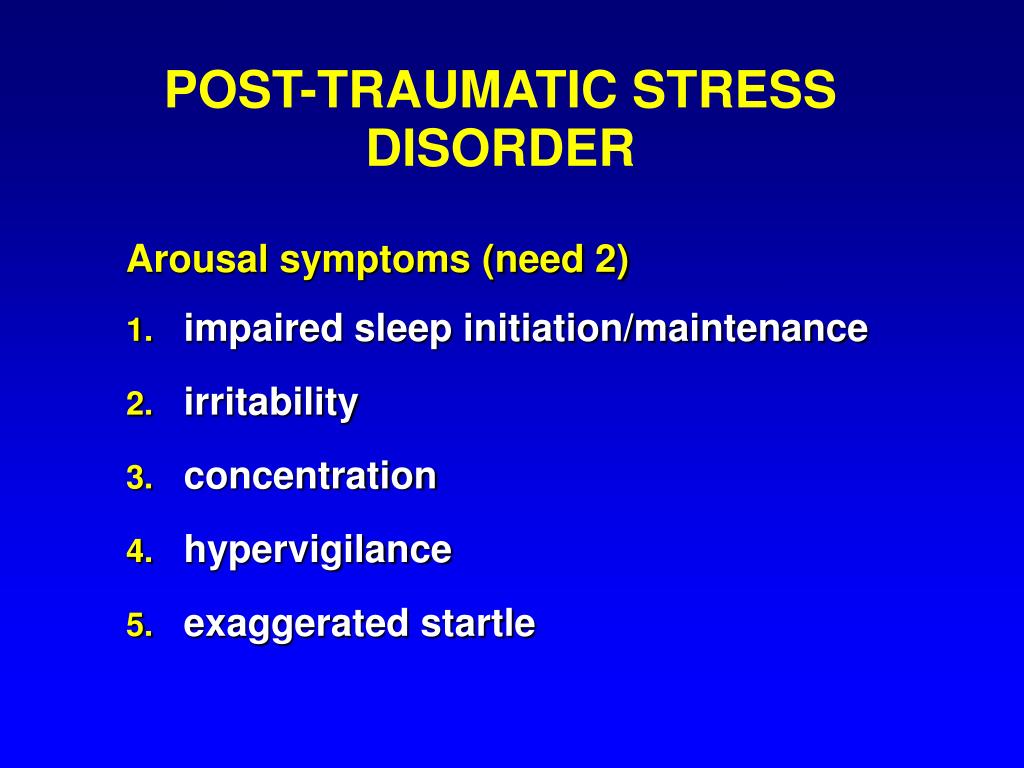

"Resiliency is the personal attribute or ability to bounce back," says Taku. PTG, on the other hand, refers to what can happen when someone who has difficulty bouncing back experiences a traumatic event that challenges his or her core beliefs, endures psychological struggle (even a mental illness such as post-traumatic stress disorder), and then ultimately finds a sense of personal growth. It's a process that "takes a lot of time, energy and struggle," Taku says.

Someone who is already resilient when trauma occurs won't experience PTG because a resilient person isn't rocked to the core by an event and doesn't have to seek a new belief system, explains Tedeschi. Less resilient people, on the other hand, may go through distress and confusion as they try to understand why this terrible thing happened to them and what it means for their world view.

Less resilient people, on the other hand, may go through distress and confusion as they try to understand why this terrible thing happened to them and what it means for their world view.

To evaluate whether and to what extent someone has achieved growth after a trauma, psychologists use a variety of self-report scales. One that was developed by Tedeschi and Calhoun is the Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) (Journal of Traumatic Stress, 1996). It looks for positive responses in five areas:

- Appreciation of life.

- Relationships with others.

- New possibilities in life.

- Personal strength.

- Spiritual change.

The scale is being revised to add new items that will expand the "spiritual change" domain, says Tedeschi. This is being done "to incorporate more existential themes that should resonate with those who are more secular" as well as reflect cross-cultural differences in perceptions of spirituality.

A predisposition for growth?

How many people experience PTG? Tedeschi prefers not to put a hard number on it.

"It all depends on the trauma, the circumstances, the timing of the measurement … [and] on how you define growth using the PTGI, looking at total score, means, factors or individual items," he says. However, he estimates that about one-half to two-thirds of people show PTG.

Some PTG researchers have tried to corroborate self-reported growth by questioning friends and family members about whether growth "sticks."

"We are getting more studies that show that PTG is generally stable over time, with a few people showing increases and a few showing decreases," Tedeschi says. "It is now up to us to learn what is going on with those who change over time, but the evidence is for stability in general, and also corroboration by others."

There appear to be two traits that make some more likely to experience PTG, says Tedeschi: openness to experience and extraversion. That's because people who are more open are more likely to reconsider their belief systems, says Tedeschi, and extroverts are more likely to be more active in response to trauma and seek out connections with others.

Women also tend to report more growth than men, says Tedeschi, but the difference is relatively small.

Age also can be a factor, with children under 8 less likely to have the cognitive capacity to experience PTG, while those in late adolescence and early adulthood—who may already be trying to determine their world view—are more open to the type of change that such growth reflects, says Tedeschi.

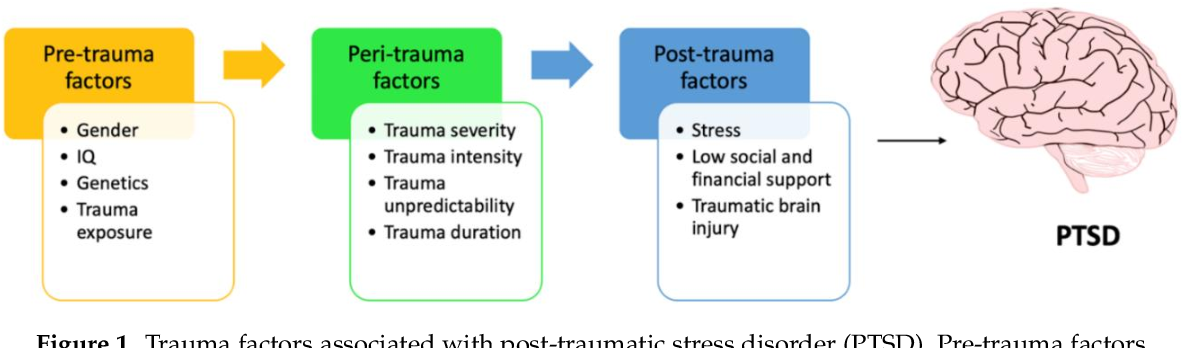

There also may be genetic underpinnings for PTG, but researchers are just beginning to tease this out. In a 2014 study in the Journal of Affective Disorders, for example, Harvard social and psychiatric epidemiologist Erin Dunn, ScD, and a team of researchers examined data previously collected from over 200 Hurricane Katrina survivors and found that variants in the gene RGS2 significantly interacted with levels of exposure to the hurricane to predict PTG. RGS2 is linked to fear-related disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, panic disorder and anxiety.

Dunn calls the results "very interesting" but notes that "we have to be somewhat cautious in interpreting it because we were unable to find a similar sample to replicate that finding. "

"

Sarah Lowe, PhD, of Montclair State University, who worked with Dunn on the research, says one difficulty with gene studies for PTG is the concept's complexity. "If you look at what predicts PTG, it is often psychological stress and dysfunction—but also more positive personality traits like optimism and future orientation, which you'd expect would have a very different genetic basis," she says.

Theory into practice

Is it possible to prepare people for PTG, to pave the way should tragedy or trauma strike? Yes, says Tedeschi, noting that psychologists can "allow people to understand that this may be a possibility for themselves" and is a "fairly normal process" if and when trauma occurs.

More often, though, therapists will become involved not before adversity has occurred, but afterward. In this context, they can introduce PTG concepts but need to take care doing so.

H'Sien Hayward, PhD, cautions that therapists should not "jump right into the possibility of growth," which she says can "often be construed as minimizing someone's pain and suffering and minimizing the impact of the loss. "

"

Hayward, who works with veterans at VA Long Beach Medical Center in Long Beach, California, knows about such growth firsthand: She was paralyzed in a car accident when she was 16, ending a competitive athletic career. She overcame that trauma through the help of supportive family and friends, went on to study social psychology at Harvard and has traveled to more than 42 countries, often on humanitarian missions providing counseling and other support to trauma victims. Today, she credits the accident for increasing her strength of character "exponentially" by forcing her to overcome challenges. She also appreciates life and relationships with others—including the near-daily support in the small tasks of daily living that she gets from friends and strangers alike: "those interactions warm my heart."

Yet Hayward is careful not to preach the potential for upside to her patients before they are ready. Instead, she waits for them to express "some positive reaction to the event."

She also helps patients discover what's meaningful in their lives and then helps them schedule activities involving these interests, such as spending more time with family members or doing volunteer work.

Tedeschi says sometimes traditional therapy for trauma patients gives people short-fix solutions to help them resume daily functions, such as sleep or work, but may not provide them with a way of living "beyond just getting by .... We've got to attend to their experience of life and how meaningful, satisfied and fulfilling it is."

One veterans' care facility that takes a nontraditional, PTG approach to trauma treatment is Boulder Crest Retreat in Bluemont, Virginia. The private, donor-supported institute provides free, weeklong nonclinical exercises and activities for vets seeking recovery from combat stress. The treatment is led primarily by veterans who have themselves gone through trauma and achieved growth. Vets are encouraged to deal with past traumas while also discovering their underlying strengths, as well as forging connections with others and ultimately finding ways to give back.

After the intensive program, vets are followed for 18 months with regular Skype check-ins.

Kevin Sakaki, a former Marine and intelligence/special operations veteran, entered Boulder Crest's Warrior program last September and found it transformative. He's noticed such changes in himself as better communication with his family, less anger ("Things don't get to me as much"), a deeper appreciation of "the little things," more generosity and a stronger connection to other people.

Tedeschi is among the psychologists studying the Boulder Crest program's efficacy as part of a research grant funded by the Marcus Foundation.

He hopes that as vets go through the process at Boulder Crest, they "develop new principles for living that involve altruistic behavior, having a mission in life and purpose that goes beyond oneself, so that trauma is transformed into something that's useful not only for oneself but for others."

Post-Traumatic Growth: Finding Meaning and Creativity in Adversity

"In some ways suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning. " —Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning

" —Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning

Kintsugi is a centuries-old Japanese art of fixing cracked pottery. Rather than hide the cracks, the technique involves rejoining the broken pieces with lacquer mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum. When put back together, the whole piece of pottery looks beautiful as ever, even while owning its broken history.

Many people are wondering at this time in history whether we will have a second life. When put back together, will we recover with dignity and grace? The science suggests that not only will we recover, but we will demonstrate the immense human capacity for resiliency and growth.

From Resiliency to Growth

In his seminal 2004 paper, clinical psychologist George Bonanno argued for a broader conceptualization of stress responding. Defining resilience as the ability of people who have experienced a highly life-threatening or traumatic event to maintain relatively stable, healthy levels of psychological and physical functioning, Bonanno reviewed a wealth of studies showing that resilience is actually common, that it is not the same as the simple absence of psychopathology, and that it can be attained through multiple, sometimes unexpected, routes. Considering that approximately 61 percent of men and 51 percent of women in the United States report at least one traumatic event in their lifetime, the human capacity for resilience is quite remarkable.

Considering that approximately 61 percent of men and 51 percent of women in the United States report at least one traumatic event in their lifetime, the human capacity for resilience is quite remarkable.

In fact, many who experience trauma—such as being diagnosed with a chronic or terminal illness, losing a loved one, or experiencing sexual assault—not only show incredible resilience but actually thrive in the aftermath of the traumatic event. Studies show that the majority of trauma survivors do not develop PTSD, and a large number even report growth from their experience. Richard Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun coined the term “posttraumatic growth” to capture this phenomenon, defining it as the positive psychological change that is experienced as a result of the struggle with highly challenging life circumstances.

These seven areas of growth have been reported to spring from adversity:

-

Greater appreciation of life

-

Greater appreciation and strengthening of close relationships

-

Increased compassion and altruism

-

The identification of new possibilities or a purpose in life

-

Greater awareness and utilization of personal strengths

-

Enhanced spiritual development

-

Creative growth

To be sure, most people who experience posttraumatic growth would certainly prefer to have not had the trauma, and very few of these domains show more growth after trauma compared to encountering positive life experiences. Nevertheless, most people who experience posttraumatic growth are often surprised by the growth that does occur, which often comes unexpectedly, as the result of an attempt at making sense of an unfathomable event.

Nevertheless, most people who experience posttraumatic growth are often surprised by the growth that does occur, which often comes unexpectedly, as the result of an attempt at making sense of an unfathomable event.

Rabbi Harold Kushner put it well as he reflected on the death of his son:

I am a more sensitive person, a more effective pastor, a more sympathetic counselor because of Aaron’s life and death than I would ever have been without it. And I would give up all of those gains in a second if I could have my son back. If I could choose, I would forgo all of the spiritual growth and depth which has come my way because of our experiences. . . . But I cannot choose.

Make no doubt: trauma shakes up our world and forces us to take an- other look at our cherished goals and dreams. Tedeschi and Calhoun use the metaphor of the seismic earthquake: we tend to rely on a particular set of beliefs and assumptions about the benevolence and controllability of the world, and traumatic events typically shatter that worldview as we become shaken from our ordinary perceptions and are left to rebuild ourselves and our worlds.

But what choice do we have? As Austrian psychiatrist Viktor Frankl put it, “When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.” In recent years, psychologists have begun to understand the psychological processes that turn adversity into advantage, and what is becoming clear is that this “psychologically seismic” restructuring is actually necessary for growth to occur. It is precisely when the foundational structure of the self is shaken that we are in the best position to pursue new opportunities in our lives.

Similarly, the Polish psychiatrist Kazimierz Dabrowski argued that “positive disintegration” can be a growth-fostering experience. After studying a number of people with high psychological development, Dabrowski concluded that healthy personality development often requires the disintegration of the personality structure, which can temporarily lead to psychological tension, self-doubt, anxiety, and depression. However, Dabrowski believed this process can lead to a deeper examination of what one could be and ultimately higher levels of personality development.

A key factor that allows us to turn adversity into advantage is the extent to which we fully explore our thoughts and feelings surrounding the event. Cognitive exploration—which can be defined as a general curiosity about information and a tendency toward complexity and flexibility in information processing—enables us to be curious about confusing situations, increasing the likelihood that we will find new meaning in the seemingly incomprehensible.

To be sure, many of the steps that lead to growth after trauma go against our natural inclinations to avoid extremely uncomfortable emotions and thoughts. However, it’s only through shedding our natural defense mechanisms and approaching the discomfort head on, viewing everything as fodder for growth, that we can start to embrace the inevitable paradoxes of life and come to a more nuanced view of reality.

After a traumatic event, whether a serious illness or the loss of a loved one, it’s natural to stew over the event, constantly thinking about what happened, replaying the thoughts and feelings over and over. Rumination is often a sign that you are working hard to make sense of what happened and are actively tearing down old belief systems and creating new structures of meaning and identity.

Rumination is often a sign that you are working hard to make sense of what happened and are actively tearing down old belief systems and creating new structures of meaning and identity.

While rumination typically begins as automatic, intrusive, and repetitive, over time such thinking becomes more organized, controlled, and deliberate. This process of transformation can certainly be excruciating, but rumination, in conjunction with a strong social support system and other outlets for expression, can be very beneficial to growth and enable us to tap into deep reservoirs of strength and compassion we never knew existed within us.

Likewise, emotions such as sadness, grief, anger, and anxiety are common responses to trauma. Instead of trying everything we can to inhibit or “self-regulate” those emotions, experiential avoidance—avoiding feared thoughts, feelings, and sensations—paradoxically makes things worse, reinforcing our belief that the world is not safe and making it more difficult to pursue valued long-term goals. Through experiential avoidance, we shut down our exploratory capacities, thereby missing out on many opportunities for generating positive experiences and meaning. This is a core theme of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which helps people increase their “psychological flexibility.” By embracing psychological flexibility, we face the world with exploration and openness and are better able to react to events in the service of our chosen values.

Through experiential avoidance, we shut down our exploratory capacities, thereby missing out on many opportunities for generating positive experiences and meaning. This is a core theme of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which helps people increase their “psychological flexibility.” By embracing psychological flexibility, we face the world with exploration and openness and are better able to react to events in the service of our chosen values.

Consider a study conducted by Todd Kashdan and Jennifer Kane, in which they assessed the role of experiential avoidance in posttraumatic growth in a sample of college students. In this sample, the most frequently reported traumas included the sudden death of a loved one, motor vehicle accidents, witnessing violence in the home, and natural disaster. Kashdan and Kane found that the greater the distress, the greater the post- traumatic growth—but only in those with low levels of experiential avoidance. Those reporting greater distress and little reliance on experiential avoidance reported the highest levels of growth and meaning in life.

The finding flipped for those resorting to experiential avoidance, and greater distress was associated with lower levels of posttraumatic growth and meaning in life. The study adds to a growing literature showing that people with low levels of anxiety coupled with low levels of experiential avoidance (i.e., high levels of psychological flexibility) report an enhanced quality of life. But this study also suggests that there is increased meaning in life too.

The increased meaning can be great fodder for creative expression.

Creating from Trauma

The link between disadvantage and creativity has a long and distinguished history, but now scientists are starting to unravel the mysteries behind this link. Clinical psychologist Marie Forgeard asked people to report on the most stressful experiences of their lives and to indicate which ones had the biggest impact. The list of adverse events included natural disaster, illness, accidents, and assault.

Forgeard found that the form of cognitive processing was critical in explaining growth after trauma. Intrusive forms of rumination caused a decline in multiple areas of growth, whereas deliberate rumination led to an increase in five domains of posttraumatic growth. Two of those domains—positive changes in relationships and increases in perceptions of new possibilities in one’s life—were associated with increased perceptions of creative growth.

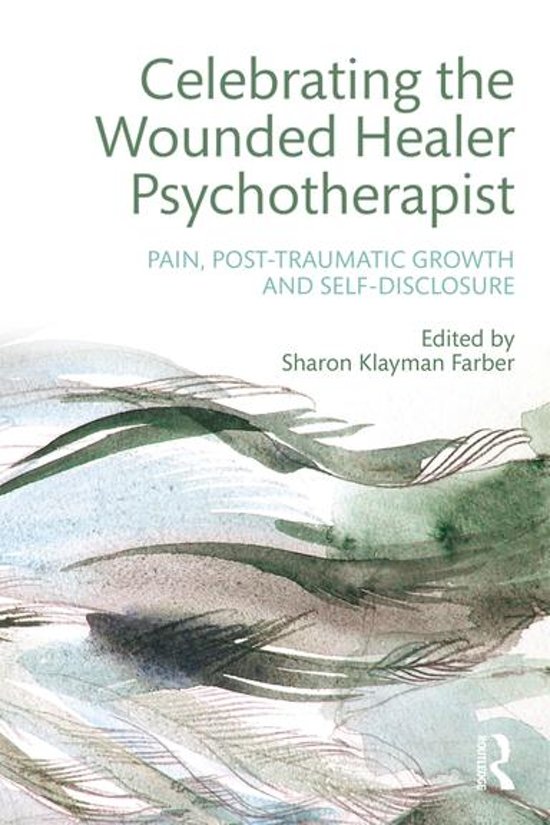

In her book When Walls Become Doorways: Creativity and the Transforming Illness, Tobi Zausner presented her analysis of the biographies of eminent painters who suffered from physical illnesses. Zausner concluded that such illnesses led to the creation of new possibilities for their art by breaking old habits, provoking disequilibrium, and forcing the artists to generate alternative strategies to reach their creative goals.

Taken together, the research and anecdotes support the potentially immense benefit of engaging in art therapy or expressive writing to help facilitate the rebuilding process after trauma. Writing about a topic that triggers strong emotions ("expressive writing") for just fifteen to twenty minutes a day has been shown to help people create meaning from their stressful experiences and better express both their positive and negative emotions.

Writing about a topic that triggers strong emotions ("expressive writing") for just fifteen to twenty minutes a day has been shown to help people create meaning from their stressful experiences and better express both their positive and negative emotions.

I know times are difficult right now, and it may seem so far away before we can become whole again. Nevertheless, the latest research on postraumatic growth can offer you some hope that we will most likely come out stronger, more creative, and with a deeper sense of meaning that we ever had before.

--

From TRANSCEND by Scott Barry Kaufman, Ph.D. published by TarcherPerigee, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House. LLC Copyright (c) 2020 by Scott Barry Kaufman

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

Scott Barry Kaufman, Ph.D., is a humanistic psychologist exploring the depths of human potential. He has taught courses on intelligence, creativity, and well-being at Columbia University, NYU, the University of Pennsylvania, and elsewhere. He hosts The Psychology Podcast, and is author and/or editor of 9 books, including Transcend: The New Science of Self-Actualization, Wired to Create: Unravelling the Mysteries of the Creative Mind (with Carolyn Gregoire), and Ungifted: Intelligence Redefined. In 2015, he was named one of "50 Groundbreaking Scientists who are changing the way we see the world" by Business Insider. Find out more at http://ScottBarryKaufman.com. He wrote the extremely popular Beautiful Minds blog for Scientific American for close to a decade. Follow Scott Barry Kaufman on Twitter Credit: Andrew French

He has taught courses on intelligence, creativity, and well-being at Columbia University, NYU, the University of Pennsylvania, and elsewhere. He hosts The Psychology Podcast, and is author and/or editor of 9 books, including Transcend: The New Science of Self-Actualization, Wired to Create: Unravelling the Mysteries of the Creative Mind (with Carolyn Gregoire), and Ungifted: Intelligence Redefined. In 2015, he was named one of "50 Groundbreaking Scientists who are changing the way we see the world" by Business Insider. Find out more at http://ScottBarryKaufman.com. He wrote the extremely popular Beautiful Minds blog for Scientific American for close to a decade. Follow Scott Barry Kaufman on Twitter Credit: Andrew French

Post-traumatic growth | On Narrative Practice, Therapy, and Community Work

book review Tedeshi, R.G., & Calhoun, L.G. (2004). Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundation and Empirical Evidence. Philadelphia, PA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Philadelphia, PA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

prepared by Daria Kutuzova

Traumatic events bring a lot of suffering and pain to a person. However, we should not forget that as a result of overcoming traumatic circumstances, a person's life can change for the better. Such changes in psychology are called "post-traumatic growth." Post-traumatic growth describes the experiences and experiences of people whose development, at least in some areas, after trauma has surpassed what it was before the trauma. The person not only survived, but in his life there were significant positive changes from his point of view that went beyond the existing state of affairs. This is not a return to the old life, to the way everything was before the injury, this is a deeply meaningful transformation of life.

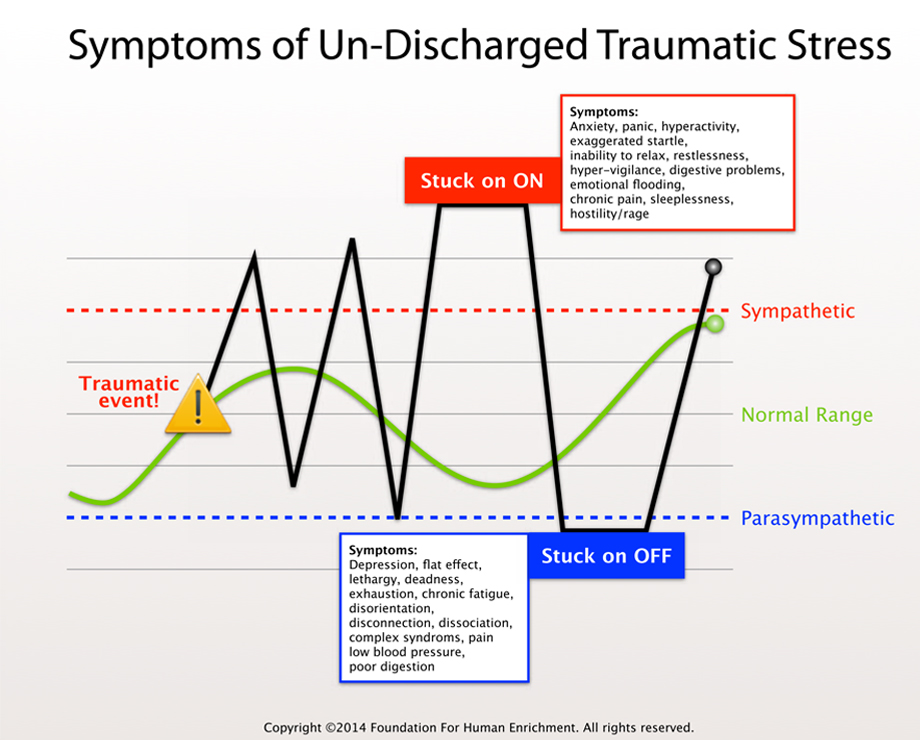

Revision of the worldview and distress

Most often, post-traumatic growth occurs when a traumatic event causes a person to significantly reconsider their worldview. The more an event threatens a person's worldview, the greater the likelihood of post-traumatic growth. Each of the areas of post-traumatic growth includes a paradoxical element: “losing something, gaining something”. Post-traumatic growth does not occur without experiencing the shock, the collapse of the foundations of the world; however, the extremely high intensity of the traumatic experience may be more than the person can bear, and the result is not development, but insanity or suicide. In order for post-traumatic growth to take place, a person must have certain skills to successfully cope with negative emotions and mental tension from the very beginning, otherwise the person is broken by events.

The more an event threatens a person's worldview, the greater the likelihood of post-traumatic growth. Each of the areas of post-traumatic growth includes a paradoxical element: “losing something, gaining something”. Post-traumatic growth does not occur without experiencing the shock, the collapse of the foundations of the world; however, the extremely high intensity of the traumatic experience may be more than the person can bear, and the result is not development, but insanity or suicide. In order for post-traumatic growth to take place, a person must have certain skills to successfully cope with negative emotions and mental tension from the very beginning, otherwise the person is broken by events.

Post-traumatic growth occurs in parallel with attempts to adapt to difficult life circumstances and high levels of psychological distress. Previously, it was believed that mental health disorders were the main and almost inevitable reactions to difficult life circumstances, but later it turned out that such conclusions were drawn on the basis of studies conducted on samples of people who sought help in a psychiatric clinic. Those who survived the trauma, but did not consult a psychiatrist, were not examined. The number of people who survive trauma and experience post-traumatic growth is significantly greater than the number of people with psychiatric disorders resulting from trauma.

Those who survived the trauma, but did not consult a psychiatrist, were not examined. The number of people who survive trauma and experience post-traumatic growth is significantly greater than the number of people with psychiatric disorders resulting from trauma.

Trauma as a mental "earthquake"

"Seismic" psychological circumstances - shocks - pose a serious challenge, contradict or even nullify the way a person understood various phenomena, causes and consequences of events, the general meaning and purpose of human existence. The metaphor of "earthquake" allows us to imagine the consequences of a traumatic event as: clearing debris after the collapse of buildings; rescue of survivors; funerals of the dead; an assessment of what survived the earthquake and what did not; what is left intact; what needs to be repaired; what needs to be demolished at all, and the ground is specially strengthened so that it would be possible to build something on this place, and in what places it is better not to build anything at all, because it will definitely shake again.

The task of coping that a trauma survivor faces is enormous. It is required not only to continue to perform daily activities in a world that now seems alien and threatening, but it is required to rebuild the inner world, create it anew, make it viable and convenient. The new beliefs must acknowledge the reality of the victim's experience, yet give them the basis for living without being completely overwhelmed by feelings of anxiety and vulnerability. Some people can't handle it. But for most, the direct experience of horror, randomness, out of control, meaninglessness, malevolence, and threat from the world eventually give way to less absolutist, more complex belief systems.

In the process of creating a new inner world, a person moves, as it were, between Scylla and Charybdis. Scylla is a temptation to try to recreate that worldview, that attitude that was before the traumatic experience. Charybdis is the temptation to believe that the world is completely evil, unfriendly and out of control. The task of the embroiderer is to create such an inner world that is believable and comfortable to live in.

The task of the embroiderer is to create such an inner world that is believable and comfortable to live in.

Shortly after the trauma, the dominant story of a person's life is the story of the hostility and uncontrollability of the world. The success of coping, the success of restructuring and survival depends on how much a person is able to recognize those experiences that are not included in this dominant story, and build alternative stories that are wider than the history of trauma.

Manifestations of post-traumatic growth

Post-traumatic growth is manifested in the fact that a person's attitude towards himself, towards other people changes, the general philosophy of life changes. As a result of overcoming a traumatic situation and its consequences, a person begins to feel both more vulnerable and stronger than before. Sometimes he opens up new opportunities in life that he had not previously suspected. The attitude to life is changing - it is not perceived as a given , something taken for granted, but like a gift , something that should be used sensibly. Facing a major life crisis can also be experienced as a test, a "test of strength." “The worst thing I could imagine, the thing I feared the most, has already happened to me; Whatever fate has in store for me next, I know that I can handle it. People who have experienced extreme, emergency situations often compare subsequent life difficulties with them. "Ha! I have seen such problems, in comparison with which these are mere trifles!

Facing a major life crisis can also be experienced as a test, a "test of strength." “The worst thing I could imagine, the thing I feared the most, has already happened to me; Whatever fate has in store for me next, I know that I can handle it. People who have experienced extreme, emergency situations often compare subsequent life difficulties with them. "Ha! I have seen such problems, in comparison with which these are mere trifles!

Obviously, during serious life tests, relationships between people can suffer or even completely collapse. However, sometimes there are positive changes. Having experienced tragedy or loss and having received support and help from loved ones, and sometimes even strangers, a person can feel a greater connection with others, trust, closeness, belonging, freedom to be themselves and compassion. Compassion leads to acts of helping and altruistic deeds.

As a result of serious life tests, people's values and priorities often change, while the so-called “simple things” begin to occupy a more privileged position - what is not fashionable, does not cost a lot of money, is not prestigious, but gives a person real pleasure and feeling meaningfulness of life: the colors of the sunset or the smile of a child. One of the changes within post-traumatic growth is a change in the experience of everyday life. Survivors feel very "lucky". Usually we appreciate not the ordinary, but the extraordinary. In order to appreciate something, we must construct it as something special, outstanding. But for a person who no longer takes life for granted, life becomes special, not ordinary, simply in large part because it may no longer be available. We value what we fear to lose.

One of the changes within post-traumatic growth is a change in the experience of everyday life. Survivors feel very "lucky". Usually we appreciate not the ordinary, but the extraordinary. In order to appreciate something, we must construct it as something special, outstanding. But for a person who no longer takes life for granted, life becomes special, not ordinary, simply in large part because it may no longer be available. We value what we fear to lose.

A traumatic event shakes up people's lives, knocks them out of the well-fed contemplation of everyday life, and as a result, people become extremely sensitive to the life process itself. They begin to realize what is important to them, to prioritize differently, to make conscious choices about how they should live the life they have so recently come to appreciate. People know that they have no control over some major life events, such as traumatic life events, but they do have control over the choices they make every day. People become committed to life, make voluntary commitments, take responsibility for their lives. The fragility and transience of life gives it more value. As a result, a person begins to be more creative and responsible in setting goals and making choices.

The fragility and transience of life gives it more value. As a result, a person begins to be more creative and responsible in setting goals and making choices.

Trauma survivors choose activities that they truly value and consider worthy of their time and effort. Research on personal projects has shown that the kinds of activities that people as a whole (“humanity”) find most meaningful are some kind of interpersonal and spiritual projects that involve achieving the goal of intimacy or community, and altruistic activities, such as working for the benefit of the community and etc. After traumatic life events, when survivors carefully choose what they are willing to give their free life to, it is not surprising that they also place special emphasis on these important areas of life - communication with friends, communication with family, building and maintaining community, local culture, and spirituality. practice. These activities not only provide structure and sources of identity, but also give a sense of direction and meaning to life. In this way, trauma survivors create their own values.

In this way, trauma survivors create their own values.

Reassessment of values leads people to experience meaning and purpose in life, it becomes clear to them what they really love and what advertising and consumer culture in general are trying to impose on them, who they would like to communicate with and who they should not waste their time on. life. As a result, people become generally happier, live life to the fullest, despite the fact that the suffering caused by the traumatic event and its consequences does not completely disappear and is also present in their lives.

Willingness to meet the challenges ahead

R. Janoff-Bulman argues that post-traumatic growth can create a specific "readiness for action" ("preparedness"), allowing survivors of trauma to overcome subsequent difficult events more calmly and confidently. If a person has experienced a serious traumatic situation and rebuilt his life world in such a way as to include this experience and the potential possibility of grief, loss, tragedy, etc. , then the difficulties that he faces in the future no longer act as a significant gap in life history and do not require all the work of reflection that was necessary in the first case. Subsequent sorrows and hardships will have negative consequences, but the person already knows how to cope with them and will not perceive these circumstances as a “trauma”. They will not lead to a transformation in the perception of oneself, relationships with other people and philosophy of life. This "readiness" is somewhat similar to "hardiness" - a psychological concept that describes the ability to return to the previous form after traumatic circumstances or resist their influence. To achieve post-traumatic growth, people must give up certain goals and basic life beliefs, and at the same time, intentionally and persistently build other life principles, goals and meanings. Changing ideas about life, changing goals create such a combination that makes it possible for a person to feel that he is moving towards his own goals, as far as possible.

, then the difficulties that he faces in the future no longer act as a significant gap in life history and do not require all the work of reflection that was necessary in the first case. Subsequent sorrows and hardships will have negative consequences, but the person already knows how to cope with them and will not perceive these circumstances as a “trauma”. They will not lead to a transformation in the perception of oneself, relationships with other people and philosophy of life. This "readiness" is somewhat similar to "hardiness" - a psychological concept that describes the ability to return to the previous form after traumatic circumstances or resist their influence. To achieve post-traumatic growth, people must give up certain goals and basic life beliefs, and at the same time, intentionally and persistently build other life principles, goals and meanings. Changing ideas about life, changing goals create such a combination that makes it possible for a person to feel that he is moving towards his own goals, as far as possible. A sense of progress towards one's own goals is key to life satisfaction.

A sense of progress towards one's own goals is key to life satisfaction.

It is important to say that although many people are positive about the achievements associated with post-traumatic growth, they also state that if they could, they would not hesitate for a second to trade all these achievements for the restoration of life in that the way it was before the tragedy.

Negative obsessive thoughts and reflective thinking

Post-traumatic growth occurs as a result of arbitrary reflective thinking about what happened. Such reflections are very different from the negative intrusive thoughts about the event that take place shortly after the tragedy itself. Types of thinking that lead to worse outcomes are focusing on the past, regretting goals that weren't achieved and now can't be achieved, and thinking about what should have been done but didn't work out to avoid injury. Negative obsessive thoughts a person tries to avoid; he moves to arbitrary reflective reflection when he has a safe context, a kind of protected territory, standing on which a person can consider what he has experienced.

A very important factor that makes post-traumatic growth possible is self-disclosure, the ability to tell - orally or in writing - about the experience, to share it with sympathetic listeners or readers. Trauma survivors are more likely to open up and talk about what happened to them to those who have “been there too” because these people are more trustworthy.

Listeners' response to the victim's story

The response of the so-called "primary reference group" to the person's story is very important. The primary reference group is understood as the circle of those who have a direct influence on a person. This group may include family, friends, a religious congregation, a sports team, neighbors, a criminal gang, work colleagues. A person constantly interacts with them, with them he shares certain worldview positions, assumptions and beliefs. In the literature, one can often find the expression that a person with this group is “identified” or “identified”. The response of the members of the primary reference group is highly likely to influence the individual's behavior and himself. It is important that these close people think about whether a traumatic experience can lead to development, and if so, under what conditions, and if not, why not, and whether their ideas correlate with the ideas of the person who experienced the trauma. It should be noted that if a person does not experience growth as a result of an injury, and in his immediate environment there are expectations that he should rise to , the person may experience a higher degree of distress.

The response of the members of the primary reference group is highly likely to influence the individual's behavior and himself. It is important that these close people think about whether a traumatic experience can lead to development, and if so, under what conditions, and if not, why not, and whether their ideas correlate with the ideas of the person who experienced the trauma. It should be noted that if a person does not experience growth as a result of an injury, and in his immediate environment there are expectations that he should rise to , the person may experience a higher degree of distress.

Belonging to one or another wider culture also influences whether and in what form a person will experience post-traumatic growth. In culture, there are stories, parables, proverbs, sayings, traditions, etc., which can set the possible trajectories of post-traumatic growth. For example, changing priorities, finding new paths in life may imply a level of flexibility and independence specific to modern Western society, which emphasizes the primacy of individualism over collectivism.

When people tell similar stories to others, the emotional aspects of the person's experience of events are revealed, resulting in a sometimes amazing feeling of closeness with the listeners. In trauma support groups, members of the group often say that the group is their family because there they can talk more about themselves and feel more accepted than in other interpersonal relationships. Trauma and growth stories can have the effect of propagating so-called “secondary post-traumatic growth,” where people change not because they themselves have experienced trauma, but because they have confided in someone who has experienced trauma. Stories of trauma and growth can transcend individual lives and change society as a whole, triggering positive change.

Skills that promote post-traumatic growth

Those who are able to voluntarily concentrate their attention, and even in the most catastrophic situation, note moments that can be glad some spheres and areas of life that are not affected by the problem. “My body may hurt, I may not have money, I may lose loved ones, etc., but at the same time I may not lose the ability to enjoy a beautiful sunset.” When there are enough such exceptions, this makes it possible to strengthen the position for understanding the traumatic experience. It is also important to be able to single out the essential in a situation and assess what is currently under the control of a person and what is not, what he should direct his efforts to, and what should be endured for the time being. The better a person copes immediately after an injury, the more active and competent he feels, the more likely that he will experience post-traumatic growth in the future. The willingness to perceive the traumatic situation as, in a sense, learning from which to learn, and reminding yourself of what you learned in the situation, is an important factor in post-traumatic growth.

“My body may hurt, I may not have money, I may lose loved ones, etc., but at the same time I may not lose the ability to enjoy a beautiful sunset.” When there are enough such exceptions, this makes it possible to strengthen the position for understanding the traumatic experience. It is also important to be able to single out the essential in a situation and assess what is currently under the control of a person and what is not, what he should direct his efforts to, and what should be endured for the time being. The better a person copes immediately after an injury, the more active and competent he feels, the more likely that he will experience post-traumatic growth in the future. The willingness to perceive the traumatic situation as, in a sense, learning from which to learn, and reminding yourself of what you learned in the situation, is an important factor in post-traumatic growth.

Post-traumatic growth: how stress hardens

We often forget that as a result of overcoming traumatic circumstances, a person's life can change and for the better. Such changes in psychology are called post-traumatic growth . The man not only survived, but significant events arose in his life. his point of view positive changes that went beyond the status quo of things. This is not a return to the old life, to how everything was before the injury, this profound life transformation. It is currently known for certain that traumatic events can lead to personal growth and positive changes.

Such changes in psychology are called post-traumatic growth . The man not only survived, but significant events arose in his life. his point of view positive changes that went beyond the status quo of things. This is not a return to the old life, to how everything was before the injury, this profound life transformation. It is currently known for certain that traumatic events can lead to personal growth and positive changes.

| Post-traumatic growth: how problems make you stronger |

that post-traumatic growth is not an end in itself for people struggling with difficult life circumstances, and is often an unexpected result even for themselves. However, people experiencing post-traumatic growth learned to appreciate life more, changed the scale of values, became more attentive to relatives and friends, believed in their strength and saw in front of them new opportunities, life prospects and ways of spiritual growth.

Rutter identifies four potential protective processes that may contribute to sustainability:

1) reducing the risk of impact,

2) reducing the likelihood of negative reactions after an encounter with a risk factor,

3) maintaining the feeling self-esteem and self-efficacy,

4) discovery of new opportunities

Surprisingly, post-traumatic growth has a systemic impact on all human health. Thus, it is scientifically established that men who survived Holocaust, live longer than other Jewish men of the same age who do not went through the hell of fascist death camps. Results studies are very encouraging - they show strength of mind and resilience a person who finds himself in terrible and almost unbearable conditions

Revision and distress

Most common post-traumatic growth occurs when a traumatic event causes a person to reconsider your worldview. The more the event threatens the worldview person, the greater the likelihood of post-traumatic growth. Each of the areas post-traumatic growth includes a paradoxical element: “losing you get something." Previously, it was believed that the main and practically inevitable reactions to difficult life circumstances are violations mental health, but later it turned out that similar conclusions were made on based on studies conducted on samples of people who applied for help in a psychiatric clinic. Those who have experienced trauma but do not see a psychiatrist applied, were not examined. Surprisingly, the number of people who have experienced trauma and experienced post-traumatic growth, significantly more than the number of people with psychiatric disorders resulting from trauma.

Each of the areas post-traumatic growth includes a paradoxical element: “losing you get something." Previously, it was believed that the main and practically inevitable reactions to difficult life circumstances are violations mental health, but later it turned out that similar conclusions were made on based on studies conducted on samples of people who applied for help in a psychiatric clinic. Those who have experienced trauma but do not see a psychiatrist applied, were not examined. Surprisingly, the number of people who have experienced trauma and experienced post-traumatic growth, significantly more than the number of people with psychiatric disorders resulting from trauma.

Literary sources allow us to identify three areas of positive change, that occur as a result of life crises, and these directions are more likely can be described as the direction of growth, and not in the traditional for the crisis psychology in terms of self-efficacy and internal locus of control. First direction describes the mobilization of the latent capabilities of the individual, which change self-perception and make a person more resistant in the face of present and future life dramas. The second direction of change points to that trauma strengthens meaningful relationships. The third direction can called existential, as it affects changes in life philosophy of man, his priorities regarding the present, future, etc.

The second direction of change points to that trauma strengthens meaningful relationships. The third direction can called existential, as it affects changes in life philosophy of man, his priorities regarding the present, future, etc.

Trauma as mental "earthquake"

"Seismic" psychological circumstances - upheavals - pose a serious challenge, contradict or even nullify how a person understood this or that, what are the causes and consequences of events, the general meaning and purpose of existence person. The earthquake metaphor allows us to imagine the consequences of a traumatic event such as: removal of rubble after the collapse of buildings; rescue of survivors; funerals of the dead; assessment of what has survived earthquakes and what not; what is left intact; what needs to be repaired; what needs to be demolished at all, and the soil is specially strengthened so that in this place in general, it would be possible to build something, and in what places it is better not to build at all nothing, because there will definitely shake again.

The task of coping with which faced by a survivor of trauma, is simply enormous. Requires not only carry on with daily activities in a world that now seems alien and threatening, but it is required to rebuild, create a new, viable and comfortable inner world. New Beliefs Must Recognize the Reality of Experience victim, but at the same time give him a basis in order to live without being completely overwhelmed by feelings of anxiety and vulnerability. Some people don't deal with it. But for most, the direct experience of horror, randomness, lack of control, senselessness, malice and threats from world over time give way to less absolutist, more complex systems representations.

In the process of creating a new of the inner world, a person moves between Scylla and Charybdis. Scylla is temptation to try to recreate that worldview, that attitude that before the traumatic experience. Charybdis is the temptation to believe that the world is completely vicious, unfriendly and out of control. And the task of the embroiderer is to create such an inner world that is believable and comfortable to live in.

And the task of the embroiderer is to create such an inner world that is believable and comfortable to live in.

Shortly after a dominant injury the story of a person's life turns out to be a story of hostility and lack of control peace. And the success of coping, the success of restructuring and survival depends on the extent to which a person is able to be aware of the experience that is not included in given dominant story, and build alternative histories that are more broad compared to history of injury.

Manifestations of post-traumatic growth

Post-traumatic growth manifests itself in the fact that the attitude of a person to himself, to other people is changing, changing general philosophy of life. As a result of overcoming the traumatic situation and its consequences, a person begins to feel both more vulnerable and stronger than before. Sometimes he gets new opportunities in life, oh which he did not suspect before. The attitude to life is changing - it is perceived not as a given, something taken for granted, but as a gift, something that follows make good use of it. Facing a major life crisis can be experienced also as a test, a "strength test". The worst that I could to imagine that what I most feared had already happened to me; what would no matter what fate has in store for me, I know that I can handle it.

The attitude to life is changing - it is perceived not as a given, something taken for granted, but as a gift, something that follows make good use of it. Facing a major life crisis can be experienced also as a test, a "strength test". The worst that I could to imagine that what I most feared had already happened to me; what would no matter what fate has in store for me, I know that I can handle it.

Survivors extreme, emergency situations are often compared with them subsequent life difficulties. "Ha! I have seen such problems, in comparison with which these are mere trifles!" It is obvious that during the serious trials of life relationships between people can suffer or even break down altogether. However sometimes there are positive changes. Having experienced tragedy or loss and received support and help from loved ones, and sometimes even strangers, a person can feel a greater connection with others, trust, intimacy, belonging, freedom to be yourself and compassion. Compassion leads to acts of help and altruistic actions.

Appreciate “simple” things

As a result of serious life trials, people often change values and priorities, while more a privileged position begins to occupy the so-called "simple things" - what is not fashionable, does not cost a lot of money, is not prestigious, but delivers to a person true pleasure and a sense of meaning in life: sunset colors or a smile child. One of the changes within post-traumatic growth is changing the experience of everyday life. Survivors feel very "lucky". Usually we appreciate not the ordinary, but the extraordinary. To appreciate something we have to construct it as something special, outstanding. But for a man who no longer takes life for granted, life becomes special, not ordinary, simply in many ways because it can be no longer available. We value what we fear to lose.

Post-traumatic growth is the growth of awareness

Traumatic event shakes life of people knocks them out of the well-fed contemplation of everyday life and in As a result, people become extremely sensitive to the very vital process. They begin to realize what is important to them, otherwise arrange priorities, make conscious choices about how they live their lives, which they have just begun to appreciate. People know that they have no control over some major life events, such as traumatic life events, but In this they are really in control of the choices they make every day. People become committed to life, make voluntary commitments, take responsibility for their lives. The fragility and transience of life gives it more value. As a result, a person begins to be more creative and responsibly begins to relate to setting goals and making choices. Trauma survivors choose activities that they really appreciate and consider worthy of the investment of time and effort.

They begin to realize what is important to them, otherwise arrange priorities, make conscious choices about how they live their lives, which they have just begun to appreciate. People know that they have no control over some major life events, such as traumatic life events, but In this they are really in control of the choices they make every day. People become committed to life, make voluntary commitments, take responsibility for their lives. The fragility and transience of life gives it more value. As a result, a person begins to be more creative and responsibly begins to relate to setting goals and making choices. Trauma survivors choose activities that they really appreciate and consider worthy of the investment of time and effort.

Personal project research showed that the occupations that people in the population as a whole consider the most meaningful are some interpersonal and spiritual projects, implying the achievement of the goal of closeness or community, and altruistic activities, such as community service, and so on. After traumatic life events, when survivors carefully choose what they are willing to give their free lives, it is not surprising that they also put special emphasis on these important areas of life – communication with friends, communication with family, community and spiritual practice. These classes not only provide structure and sources identity, but also give a sense of direction and meaning to life. In this way, trauma survivors create their own values.

After traumatic life events, when survivors carefully choose what they are willing to give their free lives, it is not surprising that they also put special emphasis on these important areas of life – communication with friends, communication with family, community and spiritual practice. These classes not only provide structure and sources identity, but also give a sense of direction and meaning to life. In this way, trauma survivors create their own values.

Revaluation values leads people to experience meaning and purpose in life, it becomes it is clear what they really love, and what advertising is trying to impose on them and consumer culture in general, with whom they would like to communicate, and with whom they should not waste time of your life. As a result, people are generally happier live life to the fullest, despite the fact that the suffering caused traumatic event and its consequences, does not disappear completely and also present in their lives.

Strengthen Vitality

Pass the Vitality Test! Vitality Test: Are You Ready for the Stress?

R. Janoff-Bulman states that post-traumatic growth can create a specific "readiness for action" ("preparedness"), which allows survivors of trauma to overcome subsequent difficult events more calmly and confidently. If a person has experienced a serious traumatic situation and rearranged his life world so as to include in him this experience and the potential for grief, loss, tragedy, etc., then the difficulties with which he encounters in the future, no longer act as an essential gap in life history and do not require all the work of understanding that was necessary in the first case. Subsequent sorrows and tribulations will negative consequences, but a person already knows how to cope with them and will not perceive these circumstances as "trauma". They won't lead to transformation perception of oneself, relationships with other people and life philosophy.

Janoff-Bulman states that post-traumatic growth can create a specific "readiness for action" ("preparedness"), which allows survivors of trauma to overcome subsequent difficult events more calmly and confidently. If a person has experienced a serious traumatic situation and rearranged his life world so as to include in him this experience and the potential for grief, loss, tragedy, etc., then the difficulties with which he encounters in the future, no longer act as an essential gap in life history and do not require all the work of understanding that was necessary in the first case. Subsequent sorrows and tribulations will negative consequences, but a person already knows how to cope with them and will not perceive these circumstances as "trauma". They won't lead to transformation perception of oneself, relationships with other people and life philosophy.

Similar "readiness" in something similar to "hardiness" psychological concept, which describes the ability to return to the previous form after traumatic circumstances or resist their influence.