Personality disorder screening questionnaire

IPDE online - international personality disorder examination screening.

The International personality disorder examination or IPDE is a user-friendly and clinically meaningful tool for clinicians to assess personality disorders. The following is a screening tool, required to assess the need for further testing. The test has a total of 59 questions and will take around 15-20 minutes to complete.

DirectionsThe purpose of this questionnaire is to learn what type of person you have been during the past five years. Please answer the following questions based on how you would mostly feel, not how you would sometimes feel. The purpose of his test is to identify problematic personality traits if any. Ratings should be based on life-long patterns and the typical functioning of an individual.

Please do not skip any items.

If you are not sure of an answer, select the one- TRUE or FALSE-which is more likely to be correct.

There is no time limit, but do not spend too much time thinking about the answer to any single statement.

Gender (optional)

Age (optional)

Name (optional)

1.I usually get fun and enjoyment out of life. *

False

True

2.I don’t react well when someone offends me *

False

True

3.I’m not fussy about little details. *

False

True

4.I can’t decide what kind of person I want to be. *

False

True

5.I show my feelings for everyone to see. *

False

True

6.I let others make my big decisions for me. *

False

True

7.I usually feel tense or nervous. *

False

True

8.I almost never get angry about anything. *

False

True

9.I go to extremes to try to keep people from leaving me. *

False

True

10.I’m a very cautious person. *

False

True

11.I’ve never been arrested. *

False

True

12.People think I’m cold and detached. *

*

False

True

13.I get into very intense relationships that don’t last. *

False

True

14.Most people are fair and honest with me. *

False

True

15.I find it hard to disagree with people if I depend on them a lot. *

False

True

16.I feel awkward or out of place in social situations. *

False

True

17.I’m too easily influenced by what goes on around me. *

False

True

18.I usually feel bad when I hurt or mistreat someone. *

False

True

19.I argue or fightwhen people try to stop me from doing what I want. *

False

True

20.At times I’ve refused to hold a job, even when I was expected to. *

False

True

21.When I’m praised or criticized I don’t show others my reaction. *

False

True

22.I’ve held grudges against people for years. *

False

True

23.I spend too much time trying to do things perfectly. *

False

True

24. People often make fun of me behind my back. *

People often make fun of me behind my back. *

False

True

25.I’ve never threatened suicide or injured myself on purpose. *

False

True

26.My feelings are like the weather; they’realways changing. *

False

True

27.I fight for my rights even when it annoys people. *

False

True

28.I like to dress to stand out in a crowd. *

False

True

29.I will lie or con someone if it serves my purpose. *

False

True

30.I don’t stick wlth a plan if I don’t get results right away. *

False

True

31.I have little or no desire to have sex with anyone. *

False

True

32.People think I’m too strict about rules and regulations. *

False

True

33.I usually feel uncomfortable or helpless when I’m alone. *

False

True

34.I won’t get involved with people until I’m certain they like me. *

False

True

35.I would rather not be the centre of attention. *

*

False

True

36.I think my spouse (or lover) may be unfaithful to me. *

False

True

37.Sometimes I get m angry I break or smash things. *

False

True

38.I’ve had close friendships that lasted a long time. *

False

True

39.I worry a lot that people may not like me. *

False

True

40.I often feel “empty” inside. *

False

True

41.I work hard I don’t have time left for anything else. *

False

True

42.I worry about being left alone and having to care for myself. *

False

True

43.A lot of things seem dangerous to me that don’t bother most people. *

False

True

44.I have a reputation for being a flirt. *

False

True

45.I don’t ask favors from people I depend on a lot. *

False

True

46.I prefer activities that I can do by myself. *

False

True

47.I Lose my temper and get into fights *

False

True

48. People think I’m too stiff or formal. *

People think I’m too stiff or formal. *

False

True

49.I often seek advice or reassurance about everyday decisions. *

False

True

50.I keep to myself even when there are other people around. *

False

True

51.It’s hard for me to stay out of trouble. *

False

True

52.I’m convinced there’s a conspiracy behind many things in the world. *

False

True

53.I’m very moody. *

False

True

54.it is hard for me to get used to a new way of doing things. *

False

True

55.Most people think I’m a strange person. *

False

True

56.I take chances and do reckless things. *

False

True

57.Everyone needs a friend or two to be happy. *

False

True

58.I’m more interested in my own thoughts than what goes on around me. *

False

True

59.I usually try to get people to do things my way. *

False

True

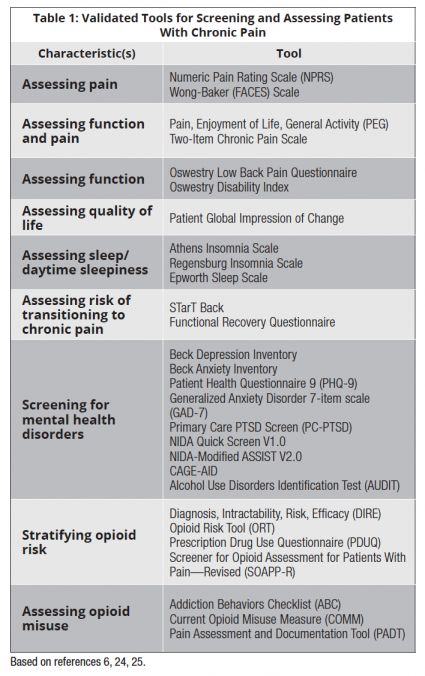

Personality Disorders: Screening & Assessment

CAMH logo- Personality Disorders

- Screening

- Diagnosis

- Treatment

- Resources & References

Back to top

Text adapted from: "The adult patient with a personality disorder," in Psychiatry in primary care by Michael Rosenbluth, Matthew Boyle & Lucille Schiffman (CAMH, 2019).

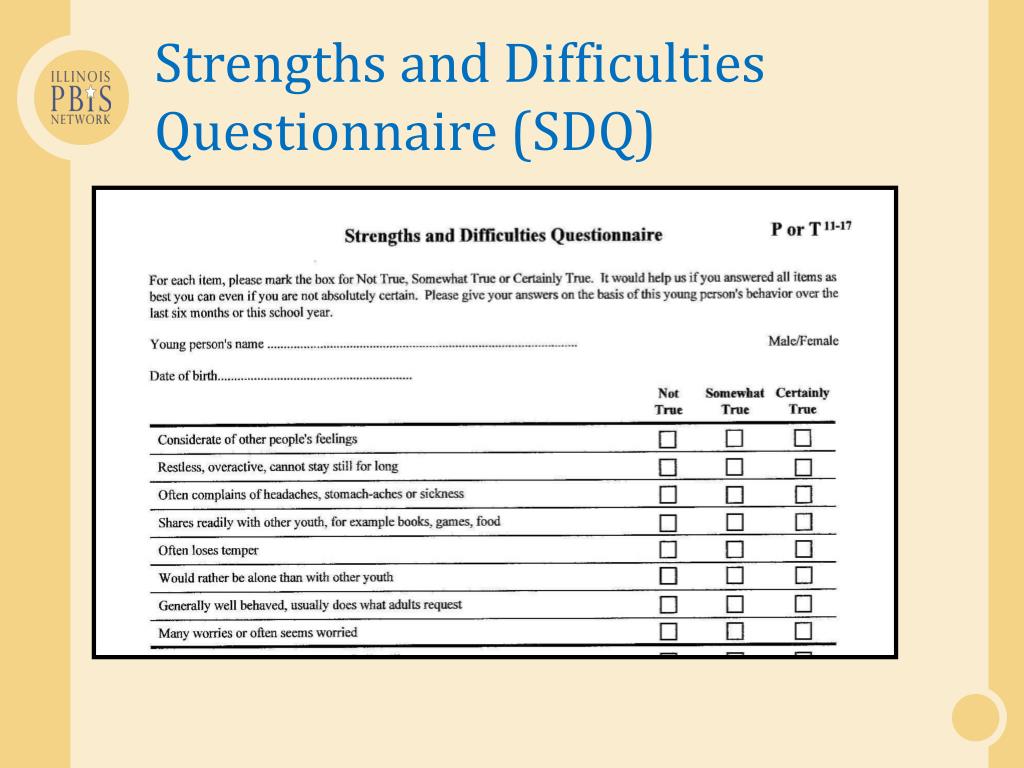

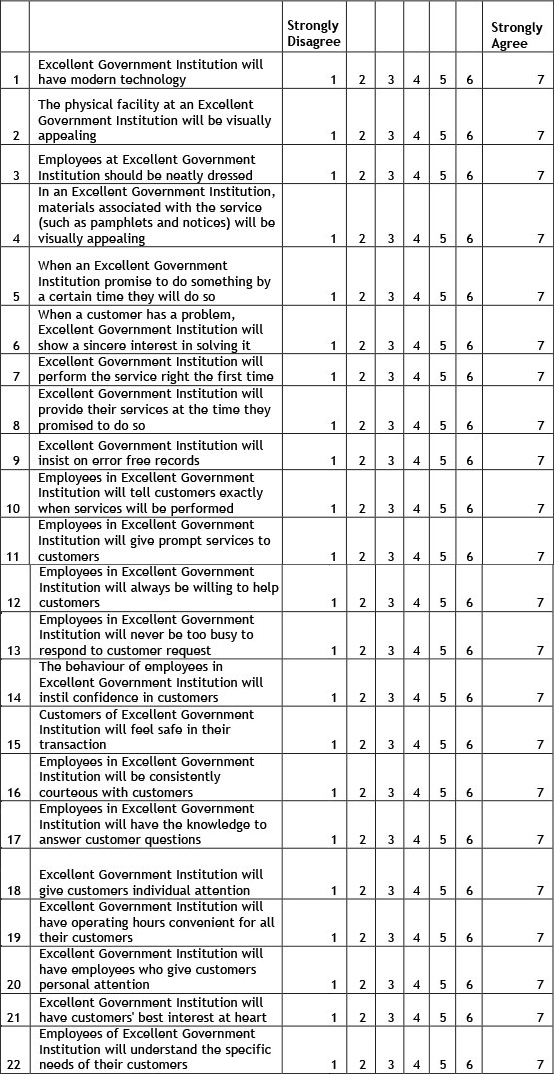

Screening for Personality Disorders

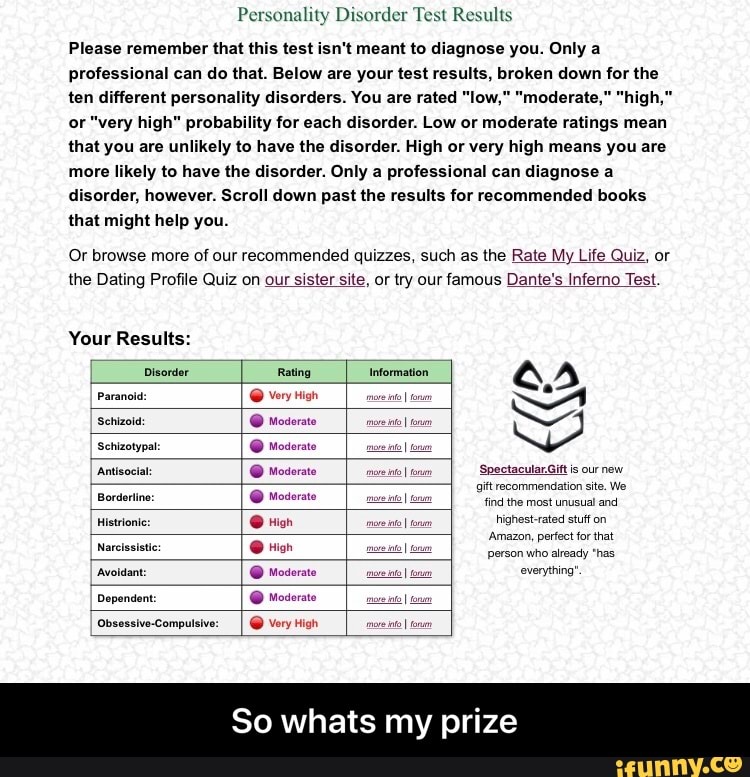

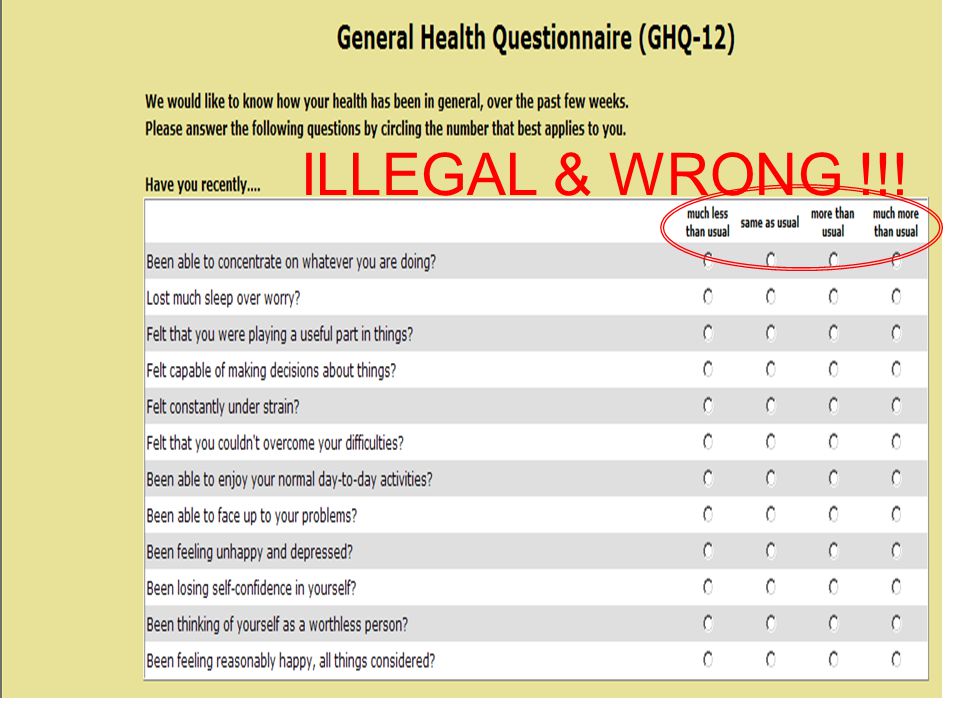

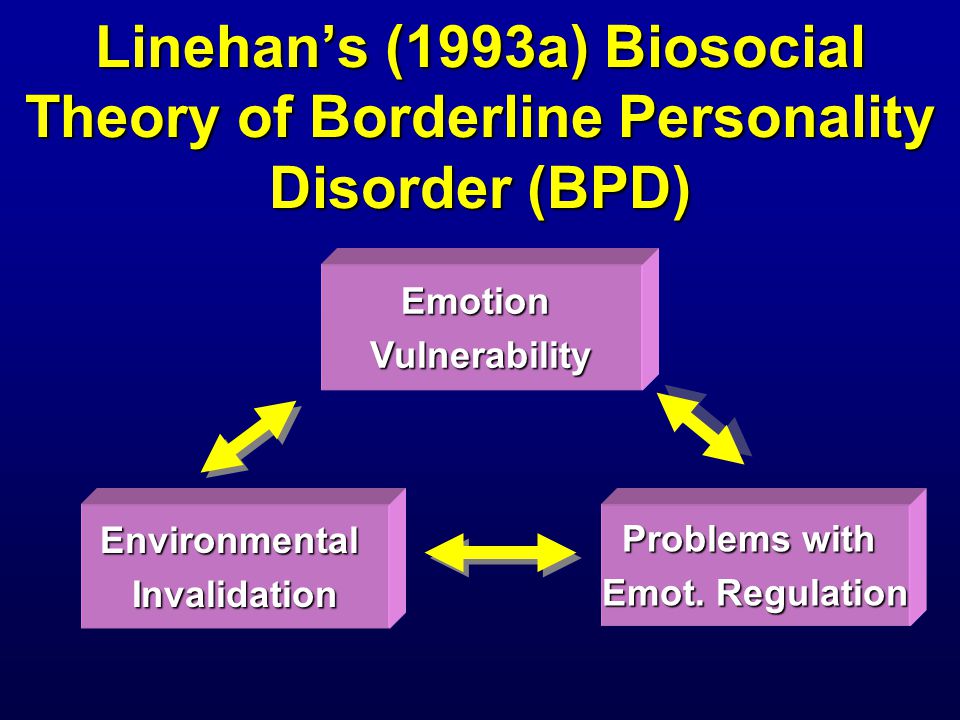

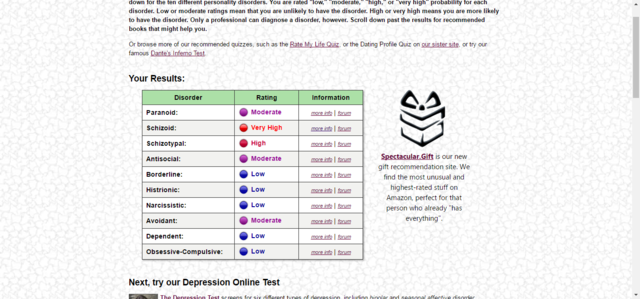

While primary care doctors may use screening tools for Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), such as the McLean Screening Instrument for BPD (MSI-BPD), the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire 4th edition—BPD Scale, and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders -Patient Questionnaire—BPD Scale (SCID-II-PQ BPD) to help diagnose BPD and personality disorders), a single, definitive personality disorder test does not exist. Instead, clinicians diagnose BPD and personality disorders through a thorough assessment that emphasizes longitudinal difficulties, and not simply the cross sectional presentation.

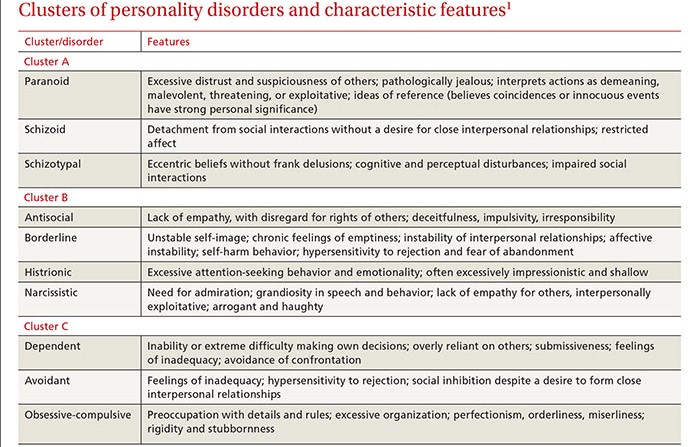

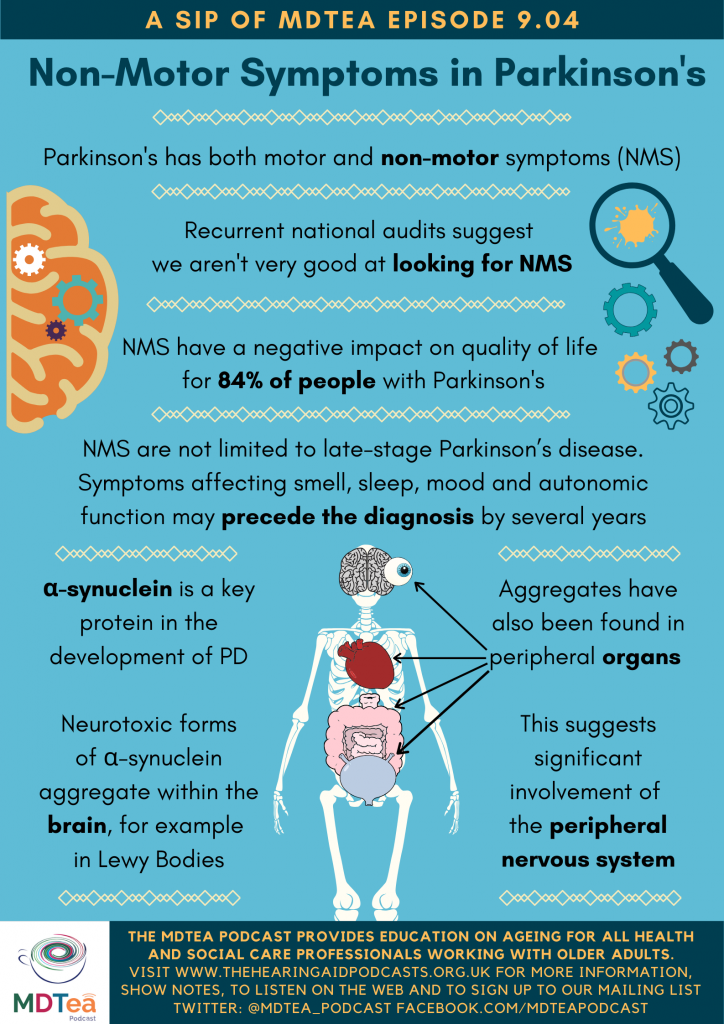

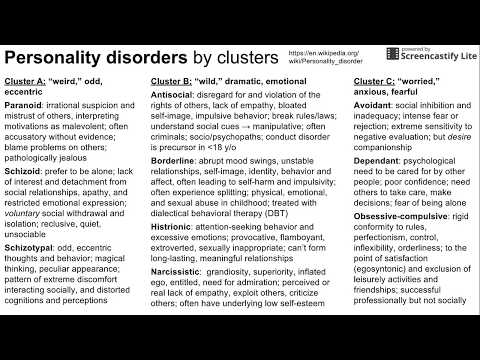

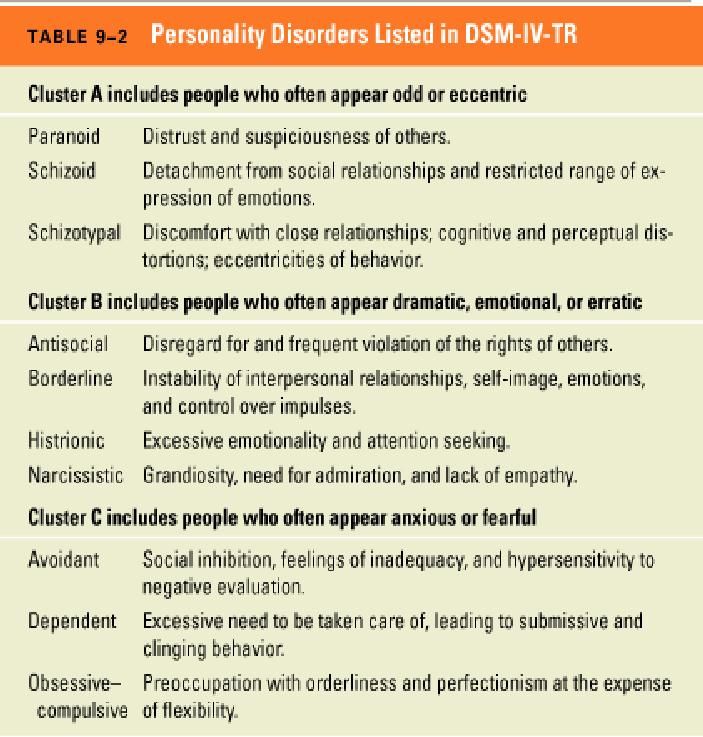

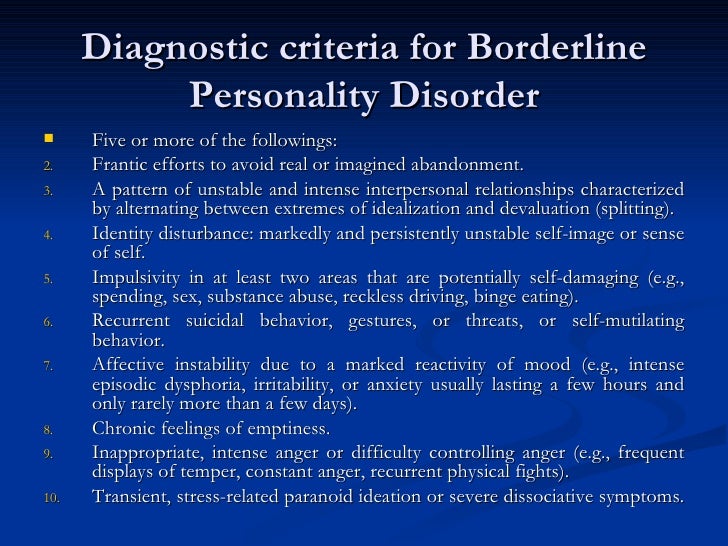

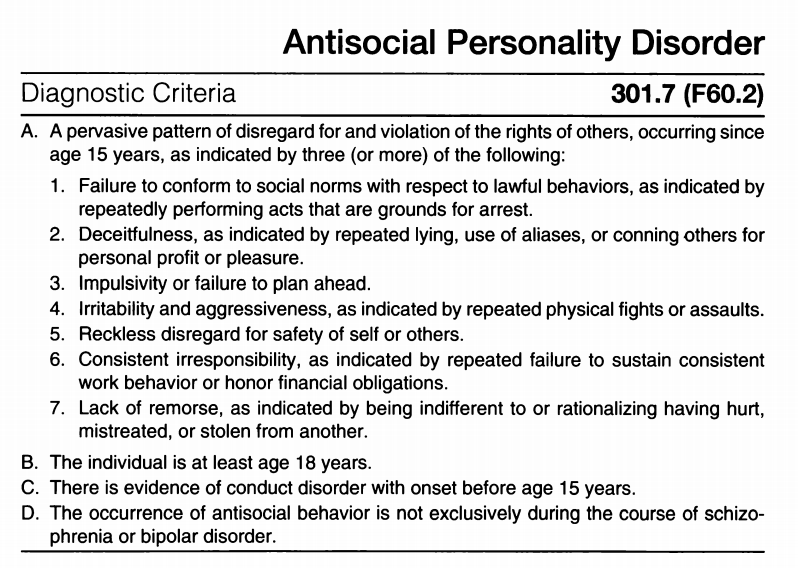

Types of Personality Disorders

Currently, there are 10 personality disorders recognized in psychiatry. Borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder are the most frequently diagnosed personality disorders (the others are listed below). The 10 personality disorders are grouped into three clusters according to shared characteristics. Each personality disorder has its own signs and symptoms, but there are similarities within each of the three clusters:

Each personality disorder has its own signs and symptoms, but there are similarities within each of the three clusters:

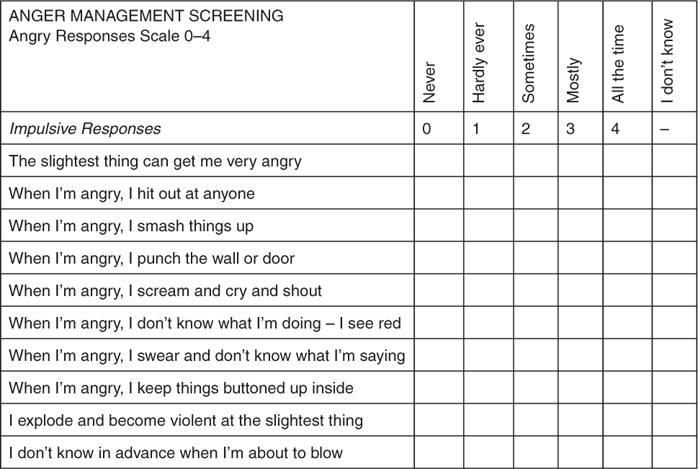

- Cluster A: paranoid, schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders. These are characterized by feeling paranoid, distrustful and suspicious.

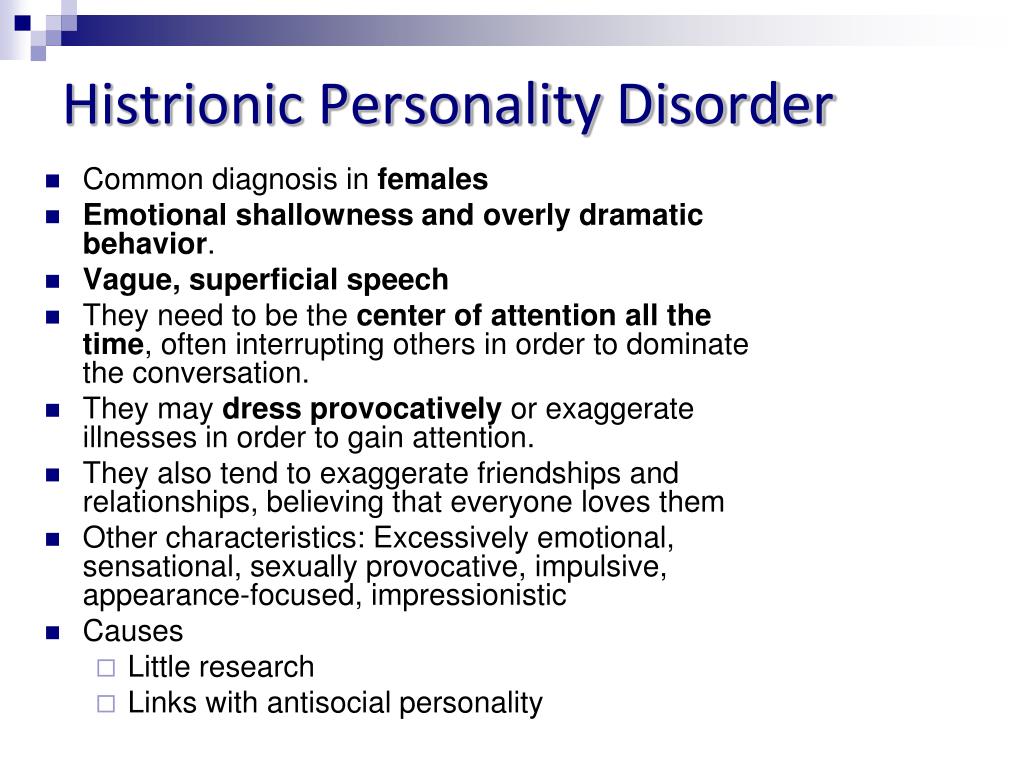

- Cluster B: impulsive personality disorders, such as borderline, narcissistic, histrionic and antisocial personality disorders. These are characterized by having difficulty controlling emotions, fears, desires and anger.

- Cluster C: anxious personality disorders, such as obsessive-compulsive, dependent and avoidant personality disorders. These are characterized by experiencing compulsions and anxiety.

People with personality disorders are at increased risk for self-harming behaviours and suicide. They may also have more difficulty getting along with others than do people without personality disorders.

In Personality Disorders

- The Primary Care Practitioner Role

- Screening & Assessment

- Diagnosis

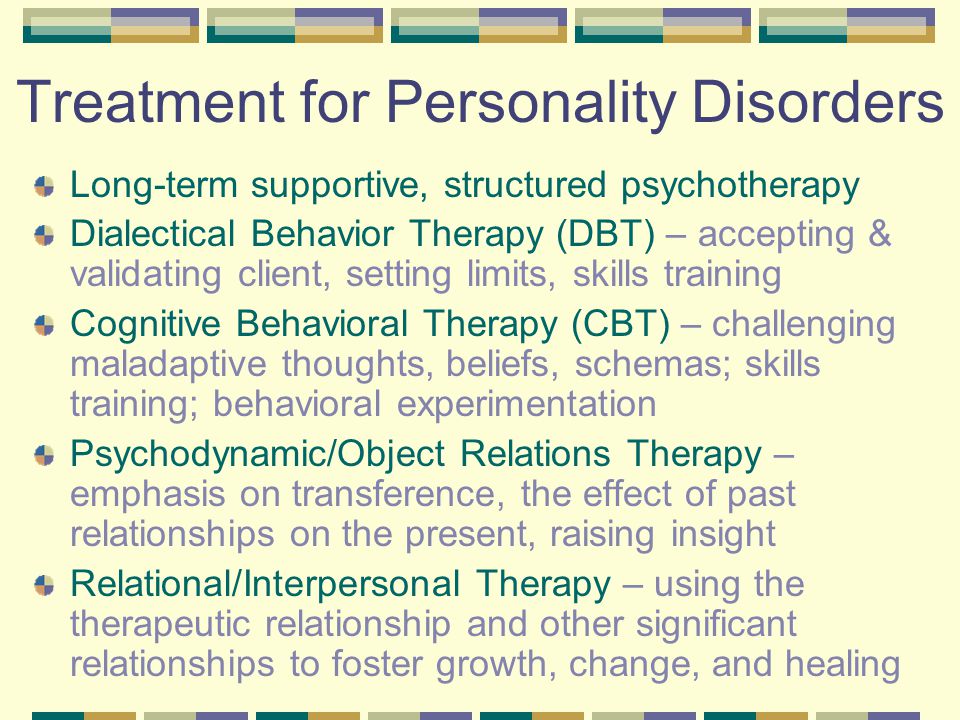

- Treatment

- Treatment When There is an Axis-1 Disorder

- Psychotherapy

- Coordinating care

- Managing reactions to the patient

- Self-harm and suicide

- Resources & References

Overview

Diagnosis

Schema therapy as treatment for adults with autism spectrum disorder and comorbid personality disorder: Protocol of a multiple- baseline case series study testing cognitive-behavioral and experiential interventions

(2017)

Authors: Richard Vuijk, Arnoud Arntz

Multi-database case series protocol testing cognitive-behavioral and experiential interventions—examining the efficacy of schema therapy in PD psychopathology in adult patients with both ASD and PD.

Methods/Project: Twelve adults (age >18 years) with ASD and at least one PD are assigned a treatment protocol consisting of 30 weekly suggested sessions. A parallel project with multiple baselines is used, the baseline varies from 4 to 9 weeks, after which the weekly support sessions range from 1 to 6 weeks and begin with sessions with a therapist. Baseline and 1-6 maintenance sessions are followed by a 5-week study phase and 10-month follow-up. SCID-II is administered during the screening procedure, at 5- and 10-month follow-up.

1.Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder. A disorder with early childhood onset and symptoms that persist throughout life. The DSM-IV and DSM-V describe ASD only at the behavioral level. In DSM-IV [1], the main symptoms are qualitative impairments in social interaction, qualitative impairments in communication, and limited repetitive and stereotypical behavior patterns. In DSM-V [2], the main symptoms are persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction in various contexts and limited, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. Social disability is multifaceted and is characterized by deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, social non-verbal communication, and the development, understanding, and maintenance of relationships.

In DSM-V [2], the main symptoms are persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction in various contexts and limited, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. Social disability is multifaceted and is characterized by deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, social non-verbal communication, and the development, understanding, and maintenance of relationships.

Both clinical practice and epidemiological studies show that more than 70% of people with ASD have developmental, medical, or psychiatric comorbid conditions (eg, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and personality disorders) [3-6]. As people with ASD become more aware of their limitations, the risk of developing these comorbidities increases. The prevalence of these disorders is significantly higher in highly functioning people with ASD than in neurotypical adults [7-9]. In a study by Lugnegard, Hallerback, and Gillberg [10], approximately 50% of adults with ASD met the criteria for a personality disorder. Four studies [11-14] revealed low scores on the characteristics "self-directedness" and "willingness to cooperate", which indicates a personality pathology [15]. The high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity and the negative impact of comorbidity on outcome and overall functioning in society make treatment necessary [16].

Four studies [11-14] revealed low scores on the characteristics "self-directedness" and "willingness to cooperate", which indicates a personality pathology [15]. The high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity and the negative impact of comorbidity on outcome and overall functioning in society make treatment necessary [16].

The field of research in the treatment of adults with ASD is still in its infancy and autism and psychotherapy are rarely combined in the literature, but this does not seem like an impossible combination [17].

The focus of therapy should be on the specific need of the ASD patient, where ASD can be seen as a major persistent and pervasive disorder with secondary comorbid psychiatric disorders.

There are currently few treatment options for adults with ASD without comorbidities, and the effectiveness of existing treatment interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and pharmacological therapy remains very limited, and will be demonstrated with little, albeit promising results [18−26].

Therefore, we have developed a special regimen therapy program for adult patients with ASD and comorbid PD. We settled on schema therapy for several reasons.

First, there is more and more evidence-based support for this therapy as a valuable treatment for BPD [27].

Second, the therapeutic relationship is active, coherent, supportive, and guiding in both content and process, which we find beneficial for people with ASD who are characterized by low self-direction [11−14, 28].

Third, schema therapy is a structured and goal-oriented psychotherapy that we find suitable for people with ASD who benefit from structure and focus.

The program consists of both cognitive behavioral and experiential interventions. Cognitive-behavioral interventions are targeted, structured, and targeted and are therefore appropriate given the nature of the disorders in ASD and the associated need for clarity and structure. We take the same approach to our experiential interventions: gradual, topic-focused, structured by explanation and psycho-education, purposeful.

2. Ongoing study

The aim of the study is to investigate whether schema therapy with cognitive behavioral and experiential interventions would be effective for adult patients with ASD and at least one personality disorder (PD). The research question is: “ Can patients with comorbid ASD-PD benefit from schema therapy, more specifically its cognitive-behavioral and experiential interventions? ".

The first objective is to study in detail the effect of major groups of schema therapy techniques, i.e. cognitive-behavioral techniques and experiential techniques, on the belief strength of negative core beliefs in patients with comorbid ASD-PD. We hypothesize that schema therapy leads to a decrease in the strength of belief in negative core beliefs. In addition, the short-term effects of both groups of methods will be compared.

The secondary goal is to reduce the frequency of dysfunctional schema modes (i. e. personality pathology in schema therapy terms). We hypothesize that schema therapy leads to a decrease in dysfunctional modes and an increase in functional modes.

e. personality pathology in schema therapy terms). We hypothesize that schema therapy leads to a decrease in dysfunctional modes and an increase in functional modes.

The third goal is to reduce the frequency of diagnostic criteria for personality disorders. We hypothesize that schema therapy leads to a reduction in the incidence of traits of personality disorders.

The fourth goal is to change the severity of psychopathological symptoms associated with syndromic disorders such as depression and anxiety disorders. We hypothesize that this treatment will reduce psychopathological symptoms.

Finally, we hypothesize that schema therapy will lead to improved social interaction and communication. Our hypothesis is that a greater understanding of one's own functioning through this treatment will lead to improved social interaction and communication.

3. Methods

3.1 Study design and procedureweeks. In this study, there are two treatment conditions (cognitive-behavioral and empirical methods) and two control conditions (baseline and research) within the subject project, without a control group.

This treatment regimen excludes randomization by groups and blind treatment. We randomize the baseline phase between participants to increase the internal validity of the case series design by varying the baseline duration from 4 to 9 weeks for different participants. We also randomize the order of onset to either cognitive behavioral or experiential interventions. Changes in baseline length and order make it possible to distinguish between temporal effects and cognitive-behavioral and experiential effects of the intervention. During the base phase, "treat as usual" (TAU) continues until 6 support sessions for participants 1 and 2 begin in week 5; 5 support sessions will start in week 6 for participants 3 and 4; 4 support sessions will start for members 5 and 6 on week 7; 3 support sessions will start for members 7 and 8 in week 8; 2 support sessions start for 9 membersand 10 at week 9; and one support session is held at week 10 for participants 11 and 12. In this way, we can check whether the meetings with the therapist and the attendance of the sessions have an effect.

This treatment regimen excludes randomization by groups and blind treatment. We randomize the baseline phase between participants to increase the internal validity of the case series design by varying the baseline duration from 4 to 9 weeks for different participants. We also randomize the order of onset to either cognitive behavioral or experiential interventions. Changes in baseline length and order make it possible to distinguish between temporal effects and cognitive-behavioral and experiential effects of the intervention. During the base phase, "treat as usual" (TAU) continues until 6 support sessions for participants 1 and 2 begin in week 5; 5 support sessions will start in week 6 for participants 3 and 4; 4 support sessions will start for members 5 and 6 on week 7; 3 support sessions will start for members 7 and 8 in week 8; 2 support sessions start for 9 membersand 10 at week 9; and one support session is held at week 10 for participants 11 and 12. In this way, we can check whether the meetings with the therapist and the attendance of the sessions have an effect. Table 1 shows a 10-week period from 4-9 weeks of TAU-baseline and 6 to 1 week with weekly Investigative Therapist maintenance sessions.

Table 1 shows a 10-week period from 4-9 weeks of TAU-baseline and 6 to 1 week with weekly Investigative Therapist maintenance sessions. Baseline and maintenance sessions, which cover a total of 10 weeks for each patient, are followed by a 5-week exploration phase with weekly sessions in which current and past functioning, psychological symptoms and schemas are examined, and negative core beliefs, as well as information about treatment. The exploratory phase is also used as a control for the consequences of paying attention to the participants' disabling problems associated with PD. There are then 15 weekly sessions of cognitive behavioral interventions followed by 15 weekly sessions of experiential interventions (or vice versa). As a result, there will be a 10-month follow-up with monthly sessions of schema therapy.

Table 1

3.2 Ethical issues

The study procedure was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Amsterdam (approved February 2, 2016).

A study brochure was prepared for participants. Participants will be asked for written consent.

The anonymity of participants will be guaranteed by removing identification information during data analysis. After 2 years, all data with names and identification data will be destroyed.

As a test of treatment integrity, all therapists in this study are highly trained and certified in cognitive behavioral therapy and schema therapy and are registered clinical psychologists. To optimize the integrity of the treatment, the therapists underwent a four-day training during which they learned and practiced therapeutic intervention schemes.

During the study, therapists will be monitored for two weeks by a clinical psychologist who is a board-certified schema therapist.

All sessions will be audiotaped and the judge will score a random sample (at least 1 tape per patient depending on condition (baseline, study, CBT, experience, follow-up) in a blinded fashion to determine conditions depending on the type of options used

3.

3 Participants

3 Participants Participants are 12 patients from the Autism Competence Center of the Sarr Institute for Psychiatric Care in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, which specializes in the psychodiagnostic evaluation and psychotherapeutic treatment of children, adolescents and adults with ASD.0003

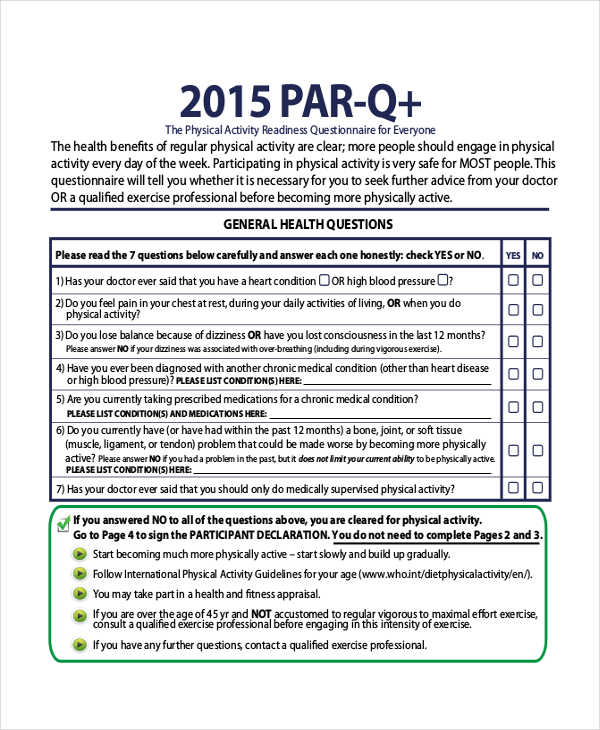

Inclusion criteria are a primary DSM-IV and/or DSM-5 diagnosis with ASD and PD, age 18 to 65 years, with an IQ indicating at least normal intelligence (IQ > 80), at least with completed primary and secondary education, having a reasonable degree of understanding of their own personality and recognition of their (psychological) functioning, as well as a willingness to participate in training for 2 years, confirmed by a signed informed consent.

Exclusion criteria are schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders, antisocial personality disorders, eating disorders, psychiatric disorders secondary to illness, mental retardation (IQ < 80), addiction (requiring clinical detoxification), and current suicidal ideation. Participants are not allowed to undergo simultaneous psychological treatment at the same time. Pharmacotherapy may be used as a concomitant intervention during treatment if it has already been initiated prior to the intervention being studied. This is not grounds for exclusion from the study. In a longitudinal study of psychoactive and drug use among adolescents and adults with ASD, Esbensen, Greenberg, Seltzer and Aman [29] found that 88% of adults were taking at least one medication, and 40% were taking three or more different types of medication. If participants need to start with pharmacotherapy or another form of (supportive) therapy during an intervention during a study, such as in the event of an acute crisis, this will not lead to exclusion from the study if that therapy and results are well documented.

Participants are not allowed to undergo simultaneous psychological treatment at the same time. Pharmacotherapy may be used as a concomitant intervention during treatment if it has already been initiated prior to the intervention being studied. This is not grounds for exclusion from the study. In a longitudinal study of psychoactive and drug use among adolescents and adults with ASD, Esbensen, Greenberg, Seltzer and Aman [29] found that 88% of adults were taking at least one medication, and 40% were taking three or more different types of medication. If participants need to start with pharmacotherapy or another form of (supportive) therapy during an intervention during a study, such as in the event of an acute crisis, this will not lead to exclusion from the study if that therapy and results are well documented.

Participants may terminate the study at any time for any reason if they wish to do so without repercussions. The investigator may decide to withdraw a subject from the study for medical reasons.

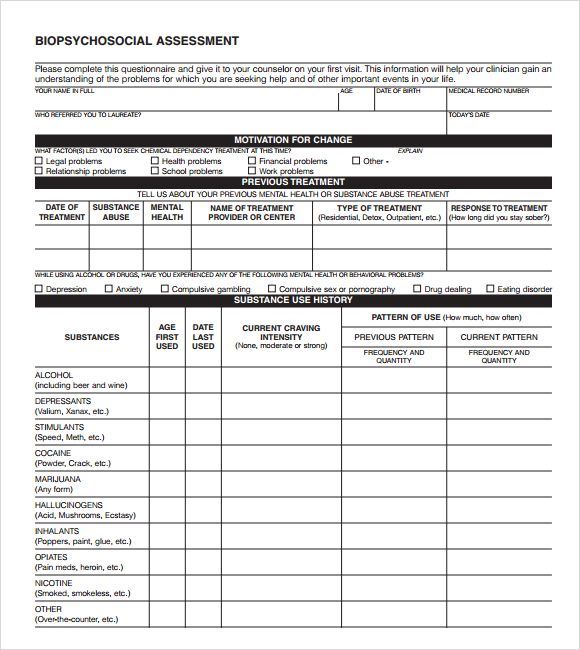

3.4 Screening procedure

The screening procedure consists of 2 sessions in which patients are screened for eligibility based on inclusion and exclusion criteria and in which negative core beliefs are formulated. This screening is performed by a registered clinical psychologist who is qualified and experienced in performing diagnostic evaluations.

The diagnosis of ASD will be confirmed by examining a diagnostic report that includes a diagnosis of ASD based on a clinical evaluation of autistic behaviors by direct examination.

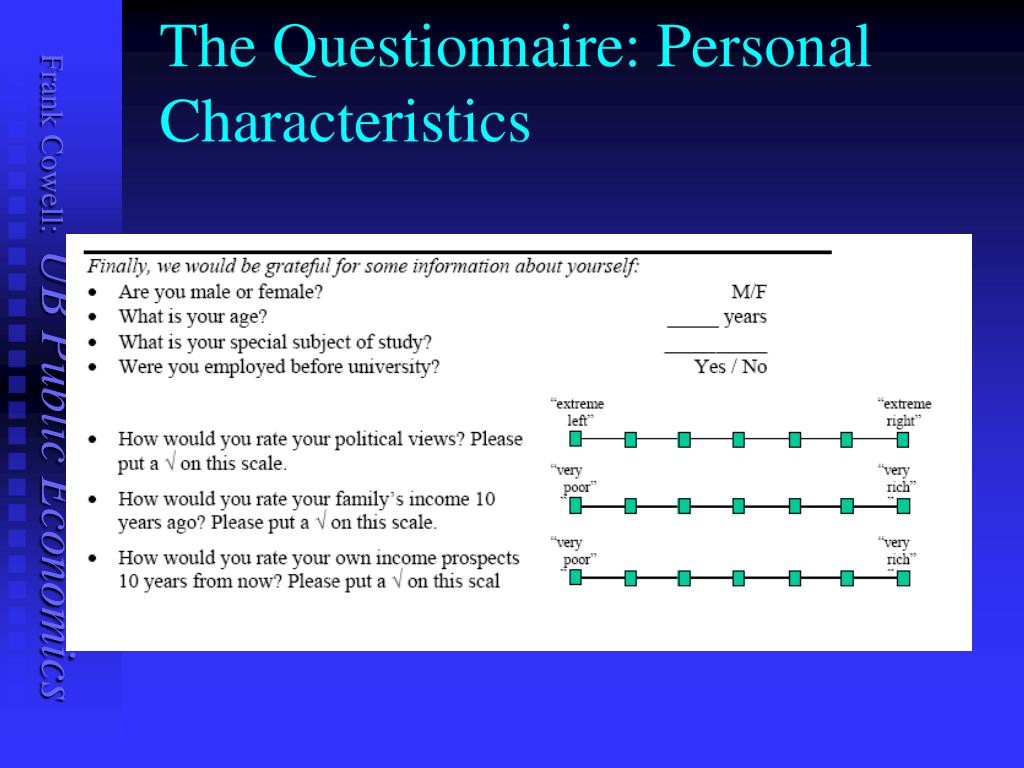

3.6 Instruments and Outcomes

3.6.1 Instruments and Outcomes

Characteristic Belief Power: In direct discussion with each participant, three to five specific beliefs are articulated that are central to the participant's concerns. Participants will rate the degree to which they believe each statement on 100 mm visual analog scales (VAS [33]) weekly during treatment and monthly at follow-up. The average score is the main result. VAS is a simple and commonly used scale and can be used to assess differences in core belief intensity. When answering the VAS question, patients indicate their level of agreement with a core belief by indicating position along a continuous line between the two endpoints from 0 to 100. Core beliefs are formulated during the screening session by a certified clinical psychologist and by the participant prior to the main phase. All participants assess VAS Core Beliefs weekly during the TAU core and maintenance sessions, Exploration Phase, CBT Phase, Experience Phase, and monthly during the Observation Phase.

The average score is the main result. VAS is a simple and commonly used scale and can be used to assess differences in core belief intensity. When answering the VAS question, patients indicate their level of agreement with a core belief by indicating position along a continuous line between the two endpoints from 0 to 100. Core beliefs are formulated during the screening session by a certified clinical psychologist and by the participant prior to the main phase. All participants assess VAS Core Beliefs weekly during the TAU core and maintenance sessions, Exploration Phase, CBT Phase, Experience Phase, and monthly during the Observation Phase.

3.6.2. Secondary Outcomes

Secondary outcomes include maladaptive modes assessed using the Mode Inventory (SMI; [34]), and PD criteria assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for Axis Personality Disorders (SCID-II; [32]). SMI contains 118 elements corresponding to 14 circuit modes, each of which is rated by frequency on a scale of 1-6 points. The Dutch version of SMI will be used. All participants complete SMI during the screening procedure (i.e., before baseline), after the baseline phase, after the study phase, after the cognitive behavioral intervention phase, after the experience phase, during and after the observation phase. SCID-II is a structured clinical interview assessing ten DSM-IV PDSs [1]. Each SCID II criterion has a score range of 1-3. All participants are assessed for SCID-II at screening (i.e., to baseline), at 5-month follow-up, and at 10-month follow-up.

The Dutch version of SMI will be used. All participants complete SMI during the screening procedure (i.e., before baseline), after the baseline phase, after the study phase, after the cognitive behavioral intervention phase, after the experience phase, during and after the observation phase. SCID-II is a structured clinical interview assessing ten DSM-IV PDSs [1]. Each SCID II criterion has a score range of 1-3. All participants are assessed for SCID-II at screening (i.e., to baseline), at 5-month follow-up, and at 10-month follow-up.

Another secondary outcome is the severity of psychological symptoms on the Symptom Checklist (SCL-90; [35]). The SCL-90 is a 90-item self-report questionnaire assessing psychological symptoms over the last week. Each item consists of five statements, rated on a severity scale of 1-4, resulting in a total score of 90-450. The Dutch version of SCL-90 will be used. All participants undergo SCL-90 during the screening procedure (i.e., before the start of the study), after the maintenance sessions phase, after the study phase, after the cognitive-behavioral intervention phase, after the experience phase, at the 5-month follow-up, and at the 10-month observation.

The final secondary outcome is an improvement in social responsiveness on the Social Responsiveness Scale - Adult Version (SRS-A; [30,31]). The SRS-A is a 64-item self-report questionnaire measuring various aspects of interpersonal behavior, communication, and the rigid, repetitive behaviors and interests of adults with ASD. The elements correspond to 4 processing scales: social consciousness, social communication, social motivation, and rigidity and repetition. Each item consists of four statements, rated on a scale of 1-4. The Dutch version of the SRS-A will be used to measure improvement in social responsiveness by analyzing total scores and scores across 4 treatment scales. All participants complete the SRS-A during the screening procedure (i.e. before the start of the study), after the maintenance sessions phase, after the study phase, after the cognitive behavioral intervention phase, after the experience phase, at the 5-month follow-up, and at the 10-month observation.

3.

7. Study parameters

7. Study parameters 3.7.1. Main research parameter

The following variable will be used to test the first hypothesis:

VAS (negative core beliefs) strength of beliefs.

3.8. Secondary study parameters

To test the second hypothesis, i.e. to assess whether schema therapy results in less dysfunctional schemas and more functional modes, manifestations of schema modes will be assessed using SMI. To answer the third hypothesis, we will use the evaluation criterion, the corresponding RLs are evaluated using SCID-II. To answer the fourth question, we will use the SCL-9 total score0 (psychological symptoms). To answer the fifth hypothesis, we will use the overall and four lower SRS-A (social interaction and communication) scores.

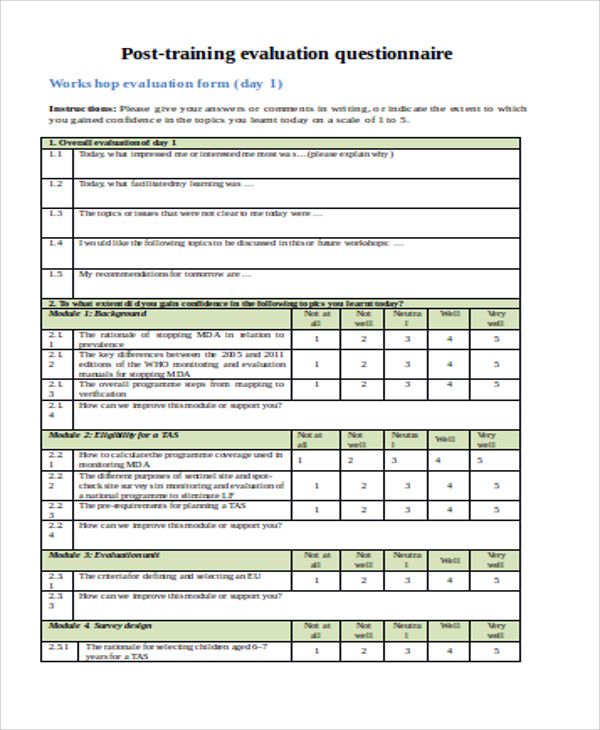

Screening procedure - 2 sessions

- Session 1-2. Inclusion and exclusion screening, administration of SMI, SCL-90, SRS-A and SCID-II, formulation of negative core beliefs, assessment of background information.

Base and maintenance sessions phase - 10-week period from 4-9TAU-baseline weeks and 6 to 1 weeks with weekly support sessions with Investigative Therapist:

- Week 5. Participants 1 and 2 start dating therapist (6 support sessions).

- Week 6. Participants 3 and 4 start dating a therapist (5 support sessions).

- Week 7. Participants 5 and 6 start dating a therapist (4 support sessions).

- Week 8. Participants 7 and 8 start dating a therapist (3 support sessions).

- Week 9 Participants 9 and 10 start dating a therapist (2 support sessions).

- Week 10 Participants 11 and 12 begin dating a therapist (1 support session).

Exploration Phase - 5 weekly sessions:

- Session 1 - Introduction to Schematic Therapy and Cognitive Behavioral and Experiential Interventions.

- Communication

- Psychological education about basic needs, functional and dysfunctional behavior, links between current problems and childhood experiences.

- Session 2 - Psychological and educational work on basic needs, functional and dysfunctional behavior, links between current problems and childhood experiences, and cognitive behavioral and experiential interventions.

- Communication

- Session 3-5 - The Conceptual Model of Personality Disorder: Schema Oriented Case Conceptualization and Childhood Presuppositions of PD Problems.

- Communication

Treatment phase - 15 weekly CBT sessions:

- Sessions 1-11 - Correction of negative core beliefs, reducing the presence of early maladaptive schemas in everyday life by completing the schema table and choosing psychoeducation, past and actual tests, analyzing pros and cons, writing a positive diary, compiling a flash card or prevention plan relapses.

- Sessions 12-14 - Replacing negative core beliefs and behavior patterns with new, healthy cognitive and behavioral options, reducing the presence of early maladaptive schemas in daily life, breaking down behavioral patterns through behavioral experiment/role play.

- Session 15 - Assessment.

Treatment phase - 15 weekly sessions of experiential interventions

- Session 1 - Psychological-pedagogical experiential interventions, introduction to image rewriting and working on two chairs, and creating an image of a safe place.

- Sessions 2-14 - Choosing to work with two chairs or recreating images of childhood memories, present or future situations.

- Session 15 - Assessment.

Subsequent phase - 10 monthly booster sessions

- Sessions 1-10 - Maintenance and deepening of changes.

3.9. Statistical analysis

We chose a parallel design (project) with several basic conditions because, like RCTs, it is able to demonstrate the occurrence of changes over time as a result of an intervention [36,37]. The current multi-baseline design is practical because it requires fewer patients. The reduced effect is offset by the fact that participants perform self-monitoring functions, as well as more evaluation of the primary outcome. We are not aware of a systemic way to perform a power analysis for a multiple reference design at the same time. As an indicator, the study would have 80% power to detect a Cohen d change of 1⁄4 1 or greater at alpha 1⁄4 0.05, two-way, if a before and after paired t-test of change before and after was used to assess treatment effect. A mixed regression analysis will be used for time, condition, and time-within-treatment, which has been successfully used in previous case series studies. Mixed regression analysis will be used to evaluate differences between study, treatment (cognitive-behavioral and experiential), and subsequent steps compared to baseline. As a guide, we refer to the article by Arntz, Sofi and Van Breukelen [38].

The reduced effect is offset by the fact that participants perform self-monitoring functions, as well as more evaluation of the primary outcome. We are not aware of a systemic way to perform a power analysis for a multiple reference design at the same time. As an indicator, the study would have 80% power to detect a Cohen d change of 1⁄4 1 or greater at alpha 1⁄4 0.05, two-way, if a before and after paired t-test of change before and after was used to assess treatment effect. A mixed regression analysis will be used for time, condition, and time-within-treatment, which has been successfully used in previous case series studies. Mixed regression analysis will be used to evaluate differences between study, treatment (cognitive-behavioral and experiential), and subsequent steps compared to baseline. As a guide, we refer to the article by Arntz, Sofi and Van Breukelen [38].

The influence of time will be tested with a linear time trend over the entire study period, with the first baseline as the zero time point. The condition will be tested at 5 levels: the base and maintenance phase of the sessions, the exploration phase, the cognitive-behavioral intervention phase, the experiential intervention phase, and the follow-up phase.

The condition will be tested at 5 levels: the base and maintenance phase of the sessions, the exploration phase, the cognitive-behavioral intervention phase, the experiential intervention phase, and the follow-up phase.

The time within processing will be checked by centered linear time effects in each of the conditions. To analyze the power of core beliefs, we will follow the same strategy as in the case of Arntz, Sofi and Van Breukelen [38] and Videler, Van Alphen, Van Royen, Van der Feltz-Cornelis, Rossi & Arntz [39]. First, a complete model with time, condition (with the baseline as a reference), will run time within each condition, with a repeating part of the AR1 or ARMA structure and, if possible, random intercepts on the coordinate axis, and slopes for the participant. If the linear time effect becomes N.S., it will be excluded from the model. Further, the effects of N.S. time-with-state will be eliminated step by step.

We expect both active treatment states to be significantly different from baseline, as is follow-up. We expect the time-within-condition to be significant, reflecting a gradual decrease in the strength of beliefs over the course of two active states, with a difference of N.S. between two active states. Other variables (other than RL scores) will also be analyzed using mixed regression, now with a simpler model, since weekly scores are not available.

We expect the time-within-condition to be significant, reflecting a gradual decrease in the strength of beliefs over the course of two active states, with a difference of N.S. between two active states. Other variables (other than RL scores) will also be analyzed using mixed regression, now with a simpler model, since weekly scores are not available.

Symptom reduction in initially diagnosed PD using SCID-II between the first (during the screening procedure), the second (at 5-month follow-up) and the last (at 10-month follow-up) measurement will be verified using the signed Wilcoxon rank test.

4. Discussion

To the authors' knowledge, no regimen-focused study has yet been published that focuses on adult patients with ASD and comorbid PD.

The aim of this study is to investigate the effectiveness of schema therapy in PD psychopathology in patients with both ASD and PD. Our work explores whether these patients can benefit from both cognitive behavioral and experiential interventions. We use cognitive-behavioral interventions to address dysfunctional cognitive beliefs and beliefs, as well as work on the development of (social) skills. We use experiential interventions to change the meaning of childhood experiences and current and future situations that have caused or contributed to negative core beliefs and schemas (see Reference [40]). In patients with BPD who do not suffer from ASD, both sets of methods were found to be effective [39,41]. Clinicians often question whether empirical methods can be used in patients with ASD. Because empirical methods are central to the treatment of BPD, it is important to test this.

We use cognitive-behavioral interventions to address dysfunctional cognitive beliefs and beliefs, as well as work on the development of (social) skills. We use experiential interventions to change the meaning of childhood experiences and current and future situations that have caused or contributed to negative core beliefs and schemas (see Reference [40]). In patients with BPD who do not suffer from ASD, both sets of methods were found to be effective [39,41]. Clinicians often question whether empirical methods can be used in patients with ASD. Because empirical methods are central to the treatment of BPD, it is important to test this.

The study is based on a paired t-test, so with 80% power, a large effect size before and after (Cohen's coefficient 1×4 1) can be detected at a significance level of 0.05. This effect size is based on previous research into schema therapy for personality disorders.

In ASD patients, the effects may be weaker, but this can only be determined later. On the other hand, a planned statistical analysis (mixed regression) and multiple evaluations of primary outcomes will result in a higher exponent than a simple double-scored paired t-test.

On the other hand, a planned statistical analysis (mixed regression) and multiple evaluations of primary outcomes will result in a higher exponent than a simple double-scored paired t-test.

A limitation of this study is that we did not consider using base length as a stratification factor when designing the study.

Since we have already started the study, this cannot be revised. However, since we independently randomized the length and order of the TAU baseline, the combinations are random and therefore we do not expect significant correlations between them.

This study offers the first systematic test of regimen prescription in adults with ASD. The results of this study will provide initial evidence for the efficacy of regimen therapy in the treatment of adults with both ASD and PD. The aim of the study is to provide valuable information for the future development and implementation of therapeutic interventions for adults with both ASD and PD.

Study status

The study began in April 2016 and data collection is expected to continue until April 2018.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

RV and AA designed the study. RV prepared most of this manuscript with critical input from another author. RV received funding. developed SPSS database. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Information about authors

RV, M.D., is a clinical psychologist and postdoctoral researcher at the Sarr Expert Center for Autism. A.A. Professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Amsterdam.

Funding

The study is funded by the Sarr Autism Expert Center.

Human rights

The study will be conducted in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Informed consent was obtained from participants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daphne van Hooken, Research Fellow at the Parnassian Academy, for her help with the development of the SPSS database, and Mathijs Dean, Parnassian Academy statistician and researcher at the University of Leiden, Institute of Psychology, for their assistance with the statistical analysis.

The study protocol received an honorable mention at the 16th National Autism Congress in the Netherlands.

Bibliography

- American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, text revision, fourth ed., American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, 2000.

- American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth ed., American Psychiatric Association, Arlington, VA, 2013.

- L.A. Croen, O. Zerbo, Y. Qian, M.L. Massolo, S. Rich, S. Sidney, C. Kripke, The health status of adults on the autism spectrum, Autism 19(2015) 814e823.

- M.-C. Lai, M.V. Lombardo, S. Baron-Cohen, Autism. Lancet 383 (2014) 896e910.

- A. Mannion, G. Leader, Comorbidity in autism spectrum disorder: a literature review, Res. Autism spectrum. Discord. 7 (2013) 1595e1616.

- L. Tebartz Van Elst, M. Pick, M. Biscaldi, T. Fangmeier, A. Riedel, High-functioning autism spectrum disorder as a basic disorder in adult psychiatry and psychotherapy: psychopathological presentation, clinical relevance and therapeutic concepts , EUR.

Archives Psychiatry Clin. neurosci. 263 (2013) 189e196.

Archives Psychiatry Clin. neurosci. 263 (2013) 189e196. - T. Lugnegård, M.U. Hallerback, C. Gillberg, Psychiatric comorbidity in young adults with a clinical diagnosis of Asperger syndrome, Res. dev. disabil. 32 (2011) 1910e1917.

- N. Skokauskas, L. Gallagher, Psychosis, affective disorders and anxiety in autistic spectrum disorder: prevalence and nosological considerations, Psychopathology (2010) 8e16.

- B. Hofvander, R. Delome, P. Chaste, A. Nyden, E. Wentz, O. Stahlberg, et al., Psychiatric and psychosocial problems in adults with normal-intelligence autism spectrum disorders, BMC Psychiatry 35 (2009) 35e44.

- T. Lugnegård, M.U. Hallerback, C. Gillberg, Personality disorders and autism spectrum disorders: what are the connections? Compr. Psychiatry 53(2012)333e340.

- H. Anckarsater, O. Stahlberg, Larson, C. Hakansson, S.-B. Jutblad, L. Niklasson, et al., The impact of ADHD and autism spectrum disorders on temperament, character and personality development, Am.

J. Psychiatry 163(2006)1239e1244.

J. Psychiatry 163(2006)1239e1244. - B. Sizoo, W. van den Brink, M. Gorissen, R.J. van der Gaag, Personality characteristics of adults with autism spectrum disorders or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with and without substance use disorders, J. Nerv. Ment Discord. 197 (2009) 450e454.

- H. Soderstrom, M. Rastam, C. Gillberg, Temperament and character in adult with Asperger syndrome, Autism 6 (2002) 287e297.

- R. Vuijk, P.F.A. Nijs, S.G. de Vitale, M. Simons-Sprong, M.W. Hengeveld, Personality traits in adults with autism spectrum disorders measured by means of the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI). (Dutch). Persoonlij-kheidsaspecten bij volwassenen met autismespectrumstoornissen gemeten met de 'Temperament and Character Inventory' (TCI), Tijdschr. Psychiatr. 54(2012) 699e707.

- C.R. Cloninger, A practical way to diagnose personality disorder: a proposal, J. Personality Disord. 14 (2000) 99e108.

- J. Renty, H. Roeyers, Quality of life in high-functioning adults with autism spectrum disorder, Autism 10 (2006) 511e524.

- P. Vermeulen, E. Vanspranghe, Psychological support of individuals with an autism spectrum disorder, Good Autism Pract. 7 (2006) 23e29.

- J. Binney, S. Blainey, The use of cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorders. A review of evidence, Ment. Health Rev. J. 18 (2013) 93e104.

- L. Bishop-Fitzpatrick, N.J. Minshew, S.M. Eack, A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for adults with autism spectrum disorders, J. Autism Dev. Discord. 43 (2013) 687e694.

- R.L. Cachia, A. Anderson, D.W. Moore, Mindfulness in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and narrative analysis, Rev. J. Autism Dev. Discord. 3 (2016) 165e178.

- S.M. Eack, D.P. Greenwald, S.S. Hogarty, A.L. Bahorik, M.Y. Litschge, C.A. Mazefsky, N.J. Minshew, Cognitive enhancement therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorder: results of an 18-month feasibility study, J. Autism Dev. Discord. 43 (2013) 2866e2877.

- A.

Gantman, S.K. Kapp, K. Orenski, E. Laugeson, Social skills training for young adults with high-functioning autism spectru disorders: a randomized controlled pilot study, J. Autism Dev. Discord. 42 (2012) 1094e1103.

Gantman, S.K. Kapp, K. Orenski, E. Laugeson, Social skills training for young adults with high-functioning autism spectru disorders: a randomized controlled pilot study, J. Autism Dev. Discord. 42 (2012) 1094e1103. - P. Howlin, Outcomes in adults with autism spectrum disorder, in: F.R. Volkmar, S.J. Rogers, R. Paul, K.A. Pelphrey (Eds.), Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders. Volume 1. Diagnosis, Development and Brain Mechanisms, fourth ed., John Wiley & Sons, Inc, Hoboken, New Jersey, 2014, pp. 97e116.

- S. Leclerc, D. Easley, Pharmacological therapies for autism spectrum disorder: a review, Pharm. Ther. 40 (2015) 389e397.

- D. Spain, S.H. Blainey, Group social skills interventions for adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review, Autism 19 (2015) 874e886.

- D. Spain, J. Sin, T. Chalder, D. Murphy, F. Happe, Cognitive behavior therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorders and psychiatric co-morbidity: a review, Research autism Spectr.

Discord. 9(2015) 151e162.

Discord. 9(2015) 151e162. - L.L.M. Bamelis, S.M.A.A. Evers, P. Spinhoven, A. Arntz, Results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness of schema therapy for personality disorders, Am. J. Psychiatry 171 (2014) 305e322.

- B.B. Sizoo, R.J. van der Gaag, W. van den Brink, Temperament and character as endophenotype in adults with autism spectrum disorders or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, Autism 19 (2015) 400e408.

- A.J. Esbensen, J.S. Greenberg, M.M. Seltzer, M.G. Aman, A longitudinal investigation of psychoactive and physical medication use among adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders, J. Autism Dev. Discord. 39(2009) 1339e1349.

- J.N. Constantino, Social Responsiveness Scale e Adult Research Version, Western Psychological Services, Los Angeles, CA, 2005.

- I. Noens, W. De la Marche, E. Scholte, SRS-a Screeningslijst Voor Autismes- pectrumstoornissen Bij Volwassenen. Handleiding, 2012 (Amsterdam:Hogrefe).

- M.B. First, R.L. Spitzer, M. Gibbon, J.B.W. Williams, L. Benjamin, Structured Clinical Interview for Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-ii), American Psychiatric Inc, Washington, D.C., 1997.

- M. Freyd, The graphic rating scale, J. Educ. Psychol. 14 (1923) 83e102.

- J. Young, A. Arntz, T. Atkinson, J. Lobbestael, M. Weishaar, M. Van Vreeswijk, J. Klokman, The Schema Mode Inventory (SMI), Schema Therapy Institute, New York, 2007.

- W.A. Arrindell, J.H.M. Ettema, SCL-90 Symptom Checklist, Pearson, Amsterdam, 2003.

- N.G. Hawkins, R.W. Sanson-Fisher, A. Shakeshaft, C. D'Este, L.W. Green, The multiple baseline design for evaluating population-based research, Am. J. Prev. Med. 33 (2007) 162e168.

- P. Onghena, Single-case designs, in: D.C. Howell, B.S. Everitt (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavrioal Science, Vol. 4Wiley, Chichester, 2005, pp.1850e1854.

- A. Arntz, D. Sofi, G. Van Breukelen, Imagery rescripting as treatment for complicated PTSD in refugees: a multiple baseline case series study, Behav.

Res. Ther. 51 (2013) 274e283.

Res. Ther. 51 (2013) 274e283. - Videler, A.C., Van Alphen, S.P.J., Van Royen, R.J.J., Van der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M., Rossi, G., & Arntz, A. Schema therapy for personality in older adults: a multiple-baseline case series design. Submitted.

- A. Arntz, Imagery rescripting for personality disorders, Cognitive Behav. Pract.18 (2011) 466e481.

- A. Weertman, A. Arntz, Effectiveness of treatment of childhood memories in cognitive therapy for personality disorders: a controlled study contrasting methods focusing on the present and methods focusing on childhood memories, Behav. Res. Ther. 45 (2007) 2133e2143.

Important :

© The article is the property of the Schema Therapy Institute, Moscow. Copying and use of materials is possible only with the written consent of the owner.

You may also be interested in:

Clinical efficacy review of schema therapy

Systematic review of clinical efficacy studies published between February 2011 and February 2015

Borderline Personality Disorder Test Online • Psychologist Yaroslav

The technique is a personality questionnaire developed on the basis of diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder according to DSM-III-R and DSM-IV in 2012 by a team of authors (T. Yu. Lasovskaya, S. V. Yaichnikov, Yu. V. Sarycheva, Ts. P. Korolenko). This questionnaire is just a convenient and valid tool for screening, daily diagnosis and verification of the diagnosis in psychiatric, general clinical and non-medical practice.

Yu. Lasovskaya, S. V. Yaichnikov, Yu. V. Sarycheva, Ts. P. Korolenko). This questionnaire is just a convenient and valid tool for screening, daily diagnosis and verification of the diagnosis in psychiatric, general clinical and non-medical practice.

The respondent is likely to have borderline personality disorder if scores more than 25 .

In this case, a consultation with a psychiatrist is required to clarify the diagnosis.

Another Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD) symptom questionnaire here

Read more about the symptoms, signs and diagnosis of BPD here

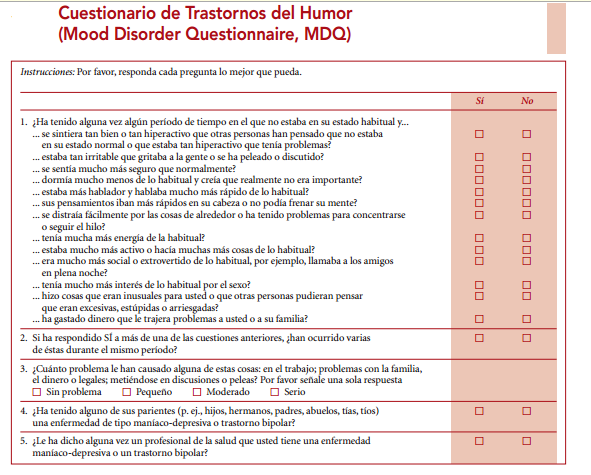

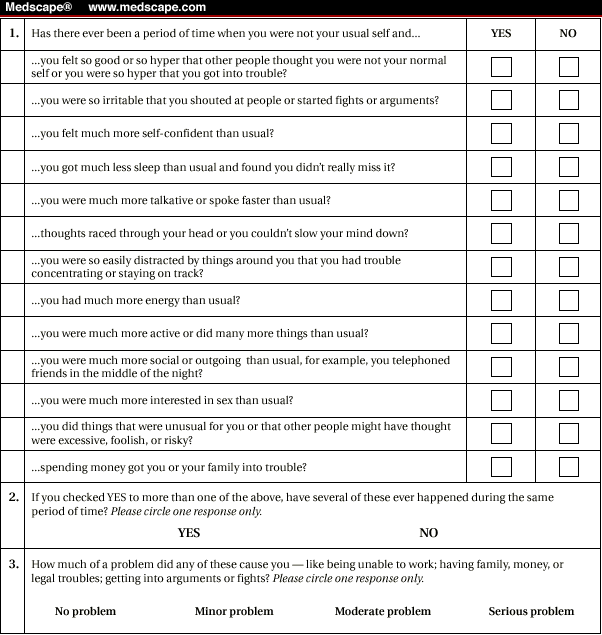

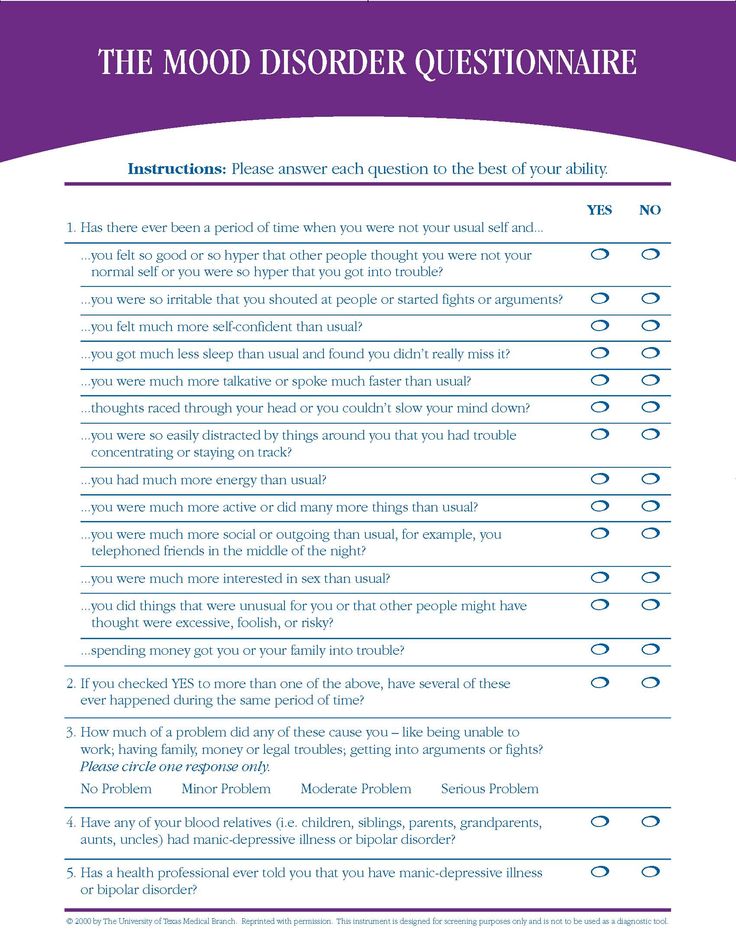

Probability Test for Bipolar Spectrum Disorders

Depression Severity Test

1. I am often disappointed in people who seemed ideal to me

Yes

No

2. I can be called a "risk person" - I like everything that helps to feel the brightness of the world - driving at high speed, spending big money, experimenting with alcohol or drugs

Yes

No

3. I experience an unprecedented high of mood if I manage to win at least a small amount of money (for example, in cards or a casino)

I experience an unprecedented high of mood if I manage to win at least a small amount of money (for example, in cards or a casino)

Yes

No

4. I have episodes when I can eat a large amount of food in a short time (sweets, cake) and in general everything that is in the refrigerator

Yes

No

5. My mood is often good, even and stable

Yes

No

6. Others notice that my mood can be very changeable - sometimes several times a day

Yes

No

7. If I am really angry, I can easily insult a person or provoke a fight

Yes

No

8. Sometimes I get very angry, which is difficult to contain

Yes

No

9. At moments of difficult emotional experiences, I have thoughts of suicide or harming myself

Yes

No

10.Sometimes I suddenly want to do something that may or may not end in my death, such as taking a large dose of medication

Yes

No

11.