Lies by omission in relationships

What Is Lying By Omission?

Not all lies involve saying things that aren’t true.

Sometimes you might omit specific details to avoid an unpleasant reaction or to spare someone’s feelings.

And you might have wondered, “Is omitting considered lying?” The short answer is yes.

Granted, it’s hard to tell the whole truth if you know it will change the outcome in a way you probably won’t like.

Lying by omission can be a form of self-preservation.

Unfortunately, even well-intentioned lies of omission can sabotage your relationship.

What’s In This Article:

[show]

What Are the 4 Types of Lies?

What is the difference between lying and withholding information? To answer this question, you need to distinguish between the four types of lies:

- Denial

- Fabrication

- Exaggeration or Minimization

- Omission of truth.

Denial is when someone refuses to accept or acknowledge a truth. This can be purposeful or habitual, and it often goes with another lie to counter the truth.

Fabrication is when someone purposely fabricates a lie, telling you something objectively untrue.

Exaggeration is when someone exaggerates a truth, making it untrue or misleading.

Omission of truth is when someone leaves out a fact, like a key detail of a situation, or chooses not to correct a misunderstanding that works in their favor.

What is Lying by Omission?

Any lie can damage trust between two people. But lies by omission are sneaky because it’s easy to trick yourself into thinking you’re not actually lying because you’re not saying something out loud that isn’t true.

You might even tell yourself it’s in everyone’s best interests for you to omit certain details — or to choose not to correct a misunderstanding.

But put yourself in the place of the one receiving the lie — or receiving incomplete information. Consider the following lie by omission examples:

Consider the following lie by omission examples:

- Someone tells your friend you missed their wedding because you were in the hospital (but you’re better, now), and you choose not to correct that lie with the truth — that you decided to see a movie instead.

- You buy a car from someone who brags about how quiet and aerodynamic it is and how infrequently he has to gas up. After he gives you the keys and drives off, you discover the car has no engine.

- You tell your new romantic partner you’ve never had a physical affair but neglect to mention you and your ex-wife divorced because you had an emotional relationship with another woman.

Lies by omission can be just as harmful as other kinds, if not more so. It’s more difficult to expose a lie of omission than to disprove a straightforward lie. Meanwhile, the damage remains and can worsen as time passes.

Why Do People Lie by Omission?

The top reasons you might lie by omission have to do with one of the following:

- Fear — of the consequences that might come of telling the whole truth

- Guilt — because your actions have caused harm to someone

- Shame — because you don’t want others to know what you’ve done

- Manipulation — because it’s a means to an end (no matter who gets hurt)

With the first three, your feelings are behind the omission of truth. With the latter, it’s pure, cold pragmatism — no feelings required. The goal is to deceive, and the only one who benefits is you.

With the latter, it’s pure, cold pragmatism — no feelings required. The goal is to deceive, and the only one who benefits is you.

The more your relationships matter to you, though, the more you’ll want to know how lies of omission can hurt them.

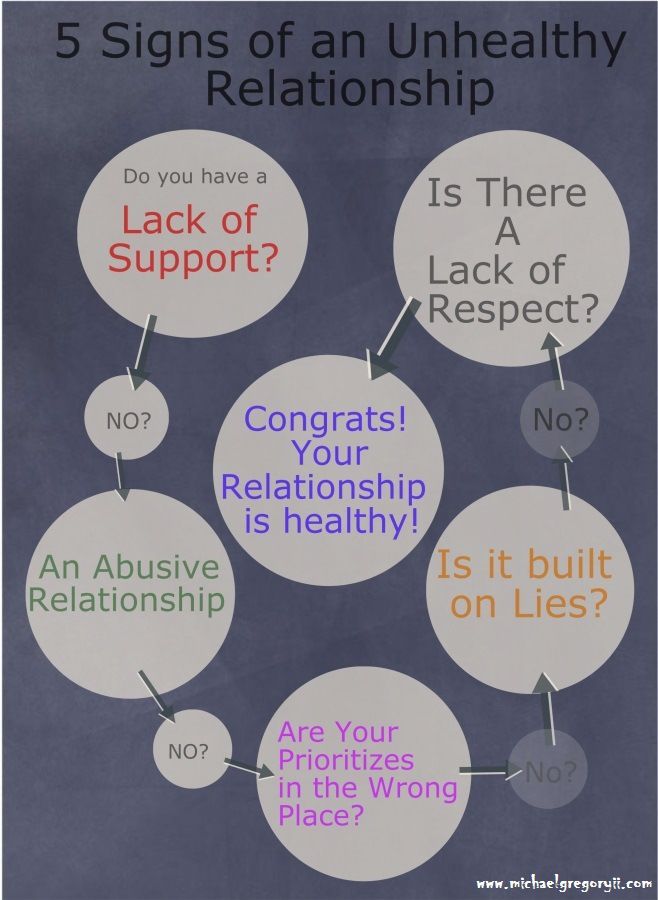

7 Reasons A Lie of Omission Hurts Relationships

Innocent as a lie by omission might seem, it’s still a lie, and it can still do damage. In fact, the more it seems to benefit you in the short term, the more it hurts in the long run. Look through the seven reasons below to understand why.

1. It causes a breakdown in communication.

Say you were fired from your previous job for showing up late, taking extra-long lunch breaks, and leaving early. When your new partner, who only knows you left that job to pursue a new opportunity, starts asking questions about what it was like working at XYZ Corporation, you find you have to keep lying to avoid suspicion.

There’s just something about lies of omission. The bigger the truth you’re hiding, the more it attracts questions.

The bigger the truth you’re hiding, the more it attracts questions.

When you keep trying to change the subject, your partner gets curious and does a little digging. Or maybe they decide they’d like to work at XYZ Corp, too, and they’re hoping your history there will give them an advantage.

Except, then they find out the truth. And kaboom.

2. Secrets can be harmful to your health.

Keeping secrets is stressful. And stress causes a variety of problems:

- Poor sleep quality

- Stress eating or poor nutrition

- Anxiety or panic attacks

- Impaired digestion (nausea, heartburn, etc.)

- Compromised immunity

- Moodiness (irritability, emotional lability, etc.)

Your body doesn’t like to hold things in. It’s got designated exit holes for a reason. But when you’re holding in a secret, your whole body is bracing for the consequences. Because eventually, the truth comes out.

And when it takes longer than it should, it tends to hurt more.

3. Hiding a problem puts a hold on any constructive solutions.

While the truth remains hidden, you can’t do anything to improve the situation around it because it has to remain secret.

If, for example, you’re hiding the fact that you no longer have a job, it’s more difficult to actively search for a new one since you’ll have to arrange for job interviews at times when you can prepare for them without arousing anyone’s suspicions. This makes it more likely that you’ll remain unemployed until you can no longer afford to hide the truth.

At that point, you will have wasted precious time you could have spent going after new job opportunities and rallying your support team behind you.

More Related Articles:

20 Signs Of Fake Friends And How To Deal With Them

11 Undeniable Signs It’s Time To Let Go Of A Relationship

12 Of The Worst Negative Personality Traits That Are Truly Nasty

4.

Lies of omission lead to misunderstandings with consequences.

Lies of omission lead to misunderstandings with consequences. Picture a pregnant woman interviewing for a job with zero intention of sticking around once her baby is born in a few months.

She could decide not to tell them this, thinking, “I could use the money I’ll earn until I give birth. They don’t need to know I won’t be coming back afterward. And they’ll probably have an easy time finding a replacement for me.”

Unfortunately, hiding her intention to leave in a few months will have consequences:

- For the employer and supervisors — wasted time and money training her for the job and a repeat of the process for someone else after she leaves.

- For her coworkers — who might come to rely on her and who will likely feel disappointed and even angry with her for leaving so soon.

- For herself — difficulty getting another job after jilting her previous employer.

She can avoid all this by being transparent about her intentions.

5. When the truth comes out, the loss of trust may be permanent.

When someone finally discovers the truth you were hiding from them, they’re likely to be angry. After all, you hid that information to steer their opinion of you in a more favorable direction, so they’ll feel manipulated as well as deceived.

And the more you gained by the deception, the worse they’ll feel about it. It’s one thing if you lied or were silent about something because you feared how it would affect their self-confidence or self-esteem. It’s another if you lied by omission to protect yourself.

Even if you thought you were acting to their benefit, though, they won’t trust you as much as they did before. And they might never again.

6. If you kept one thing secret, what else are you not telling them?

The more you lie, the easier it gets, and that goes for lying by omission, too. If you can justify keeping important details to yourself in one situation, you’re more likely to do the same in others. So, why should anyone trust you once they’ve learned the truth?

So, why should anyone trust you once they’ve learned the truth?

For example, if you hold off on telling someone you noticed another employee stealing office supplies, and that employee points the finger at you when he’s caught, your employer might well suspect you of doing the same.

And if you’ll lie by omission to avoid discomfort, why wouldn’t you lie again to keep your job?

7. What starts as self-protection ends as self-sabotage.

Ultimately, any omission of the truth will catch up. And the bigger the truth you kept, the bigger the fallout for you.

While you might have lied by omission to protect yourself or your reputation, in the end, the lie will cost you more than if you’d owned up to it from the start. In trying to act in your best interest or (to some extent) someone else’s, you end up sabotaging that good.

Even relatively innocent lies of omission — like neglecting to tell your partner you bought candy for your three-year-old to keep her happy — can contribute to a habit of omitting truths, which can then lead to bigger omissions, with bigger consequences.

So, in trying to avoid an unpleasant reaction in the short-term, you’re setting yourself up for a much more painful one down the road.

Don’t let lying by omission harm your relationships.

Now that you know what it means to lie by omission, you can probably think of moments when you kept certain details to yourself. And maybe you’ve yet to see any negative consequences.

But you might have noticed it’s gotten easier to lie. To make it harder, picture yourself in the other person’s shoes.

If you’d rather hear the unpleasant whole truth right up front than hear a pleasant half-truth — only to be blindsided later on — tell them what you’d want to be told.

May have you have all the courage you need to do the right thing.

What Is Lying By Omission And How Does It Harm Relationships?

Get expert help dealing with lies by omission from your partner. Click here to chat online to someone right now.

Lying by omission is when a person leaves out important information or fails to correct a pre-existing misconception in order to hide the truth from others.

“I didn’t lie; I just didn’t tell you.”

Ahhh, that old chestnut. Now where have I heard that before?

Some people view omissions as more than just white lies, but as outright lying, because by omitting information, you’re no longer being transparent.

A lack of vulnerability and transparency hamper communication, and destroy the safety that is expected in all close knit relationships – be they friendships or romantic partnerships.

Lying by omission is not always intended to be harmful; it is often thought of as an action undertaken to spare the recipient pain or embarrassment. But it can still have a detrimental effect on a relationship.

Even if the damage isn‘t immediate, the information omitted will eventually surface. The fallout from this can cause more problems than it would have if the information had been shared immediately, and accountability had been taken by the person sharing it.

Why Do We Omit Critical Pieces Of Information?

There are usually three reasons for people lying by omission:

- Fear (being on the receiving end of anger, reprisal, or punishment)

- Guilt (for the activity that caused them to lie in the first place)

- Shame (for their reputation being damaged, and how they will be perceived if the entire truth was known)

How Do People Lie By Omission?

It’s not just about leaving out a specific detail, lying by omission can take another form: manipulating your response to garner sympathy, or to protect self-interests.

There are two sides to every story – are you only sharing yours? If you tailor your responses to leave out the harshness of what really happened, you’re not being genuine, and that’s lying.

You’re more concerned about how you will come off socially than you are about sharing the truth, and that colors how others will respond to you. What does that mean? For one, you’re not getting their honest opinions because you’re not giving them all the information – half truths provide half-baked answers.

For example, if you tell a friend about a fight with your mother and how she was being unreasonable because the train was delayed causing you to be an hour late for her birthday dinner party, they will probably nod their head and sympathize, because let’s face it, sometimes we’re at the mercy of others. Stuff happens, technology fails, trains break down, or get rerouted.

However, if you also neglect to tell that friend that you left the house half an hour late because you were busy scrolling through Twitter, then realized you had to dash, and then lied to your mother about the train delay… how would their response differ?

You haven’t painted the full picture because you’re afraid of how you might look, to them, and your mother. To your mom, it would look like scrolling through social media was more important than her (because being late is saying, I am ok disrespecting you and devaluing your time). To your friend, you would look insensitive and rude, and that’s the truth.

To your mom, it would look like scrolling through social media was more important than her (because being late is saying, I am ok disrespecting you and devaluing your time). To your friend, you would look insensitive and rude, and that’s the truth.

Lastly, you also know that your friend would be likely to take your mother’s side if all the facts were laid bare, so you tell them an edited version of events. Then, your mother looks like the “bad guy,” and you come out smelling of roses.

This is just a tiny example of how people lie every day. In a million different ways, tiny bits of information are left out of conversations. What we get is half a story; and seemingly insignificant things that come back to haunt us later.

You’re scoffing, “How does lying about a train delay haunt someone?” How does omitting information damage you, and your relationships?

Here are four ways lying by omission hurts everyone.

It Damages Your Health

While most people think that they are sparing the other party by omitting important details, they don‘t realize that they are also inadvertently damaging themselves.

Keeping secrets is stressful. It can cause loss of sleep, and increased anxiety. Why? Because you’re preoccupied with trying to keep the problem under wraps, and keeping your story straight, while also fearing what will happen if the secret ever gets out.

The phrase, “the truth shall set you free” has never been more appropriate. By being fully open and honest with the other person, you free yourself of the burden of hiding this information and worrying about the fallout.

Losing sleep, and being stressed, will eventually have a harmful effect on your physical health. The sad thing is, it’s completely preventable, and completely in your hands.

It Damages You Emotionally

Lying by omission can leave a bad taste in your mouth. In addition to the stress and sleep issues, it can make you feel inauthentic. You feel like a fake, and emotionally, that can take a toll on your self-esteem.

In the example mentioned above, do you feel good after you have painted your mother out to be an unreasonable tyrant? Does that sit well with you? You may have saved your reputation with your friend, but you have inadvertently made your mother look bad at your expense.

If you have any shred of decency, you will feel bad about it at some point. Protecting yourself at the cost of making someone else look bad will always haunt you. You know you’re harming them, and influencing how other people will view them. There are things money can’t buy, and self-respect is one of them.

It Damages Your Credibility

Lying by omission breeds mistrust. Once the person you have been hiding things from finds out, the likelihood of them trusting you again has gone out the window.

It doesn’t matter if it was for their own good, or a protective move, it will just come across as an excuse, or what it really is: keeping yourself from getting in trouble.

In the eyes of that person, a lie, is a lie. There is no shade of gray when someone feels they have been lied to. That’s the point people miss when they believe that by omitting something they are not lying, but straddling some magical misty zone of truthiness.

Once the information is out, your credibility is shot and it will take a long time (if ever) to earn that back.

It’s Selfish

Last, but not least, lying by omission is selfish as Hell. Admit it. On a deep level, omitting something isn’t really about the other person’s feelings; it’s about protecting yourself from looking bad.

If you really have a hard think about the anxiety and fear that surrounds omitting a piece of information, nine times out of ten, in your gut you know it’s about saving your skin.

Saying it was to “protect the other person” is often a cop out. It’s just a convenient way of deflecting your need to control the outcome of a situation where you could potentially be perceived negatively.

Why do all this to yourself, and to the people you care about? Nothing feels better than being able to look someone in the face knowing you are being the most authentic version of yourself.

Being honest also demonstrates a profound level of maturity and compassion. When you aren’t busy saving face at the expense of others, and you’re fully accountable for your own actions, it’s not only incredibly empowering, but it’s also extremely empathetic.

It shows strength through vulnerability. It’s human to make mistakes – we are all blundering our way through life. There are no perfect people on this planet, so lets drop the façade, admit our follies, dust ourselves off, and get on with living life honestly, and to the fullest.

Still not sure what to do about your partner’s lying by omission? Chat online to a relationship expert from Relationship Hero who can help you figure things out. Simply click here to chat.

You may also like (article continues below):

- Why Pathological Or Compulsive Liars Lie + 10 Signs To Look Out For

- 8 Ways Lying Is Poisonous To Relationships

- How To Respond When You Find Out Someone Has Lied To You

- 6 Reasons Why Your Partner Lies To You About Little Things

- 10 Subtle Signs You’re Being Lied To

- How To Stop Lying In Just 6 Steps!

- 4 Ways A Lack Of Empathy Will Destroy Your Relationships

- How To Deal With Emotionally Unintelligent People

- How To Rebuild And Regain Trust After Lying To Your Partner

Why do we lie in a relationship and what does it lead to?

It's not that I'm a pathological liar. It's just that I have some kind of selective lie - for example, I never deceive my friends, and if I try to lie for good, I immediately blush treacherously. But in relationships, I am a virtuoso of lies. Except one case.

It's just that I have some kind of selective lie - for example, I never deceive my friends, and if I try to lie for good, I immediately blush treacherously. But in relationships, I am a virtuoso of lies. Except one case.

For four years I dated the perfect Yegor: he didn't quarrel, understood everything, didn't get jealous, didn't lose patience, gave flowers regularly, fulfilled every wish and didn't forget about dates and details. And he still did not know how to make strong-willed male decisions. It was good and ... boring with him.

After graduate school, we went on a trip with a big group, where I fell in love with his friend Vlad. Despite the male friendship, he began to look after me - right on the trip, without hiding from Yegor. When we returned to Kyiv, Vlad began to constantly make appointments with me. Coincidentally, I was just looking for a new home, which we originally planned to rent together with Yegor, but he was in no hurry to take the initiative.

As a result, Vlad invited me to live with him - temporarily, as a friend. We both knew that this was a lie and that our neighborhood would not be limited to joint breakfasts. Most of all, my friends were amused by the fact that Yegor himself brought me to Vlad, and then my things. And yes, I told him that Vlad and I are friends. But it didn't seem to bother him at all. We continued to date for almost a year before we broke up. He never once suspected me of cheating.

We both knew that this was a lie and that our neighborhood would not be limited to joint breakfasts. Most of all, my friends were amused by the fact that Yegor himself brought me to Vlad, and then my things. And yes, I told him that Vlad and I are friends. But it didn't seem to bother him at all. We continued to date for almost a year before we broke up. He never once suspected me of cheating.

It would seem that they usually say about such cases: “If you managed to deceive a person, this does not mean that he is a fool. You've just been trusted more than you deserve." But now it seems to me that it was a matter of self-deception, and not of trust in me. I think it was just painful for Yegor to admit that our relationship did not become ideal. Such is the defensive reaction.

Why do we deceive ourselves? Olga Kornienko, Ph.D. in Psychology, a practicing psychologist and leader of training groups, comments: “Often we seem to not recognize the truth ourselves, we don’t want to understand it. Then it goes into the shadows - that part of our personality that is not realized, but instinctively influences our emotions, choices, reactions. This is the part that is denied by our sharp-sighted inner "critic" who knows what is "right" to be, especially for a particular person or group of people. Hence the name "the shadow side of our personality." Through the acceptance of it in oneself, the recognition of its existence, the possibility of expressing it, it becomes conscious and possible for presentation. To do this, we need to agree with our "critic", the "social mask" that we wear for others and for ourselves, with the concepts of "good and bad", "right and wrong", "beautiful and ugly".

Then it goes into the shadows - that part of our personality that is not realized, but instinctively influences our emotions, choices, reactions. This is the part that is denied by our sharp-sighted inner "critic" who knows what is "right" to be, especially for a particular person or group of people. Hence the name "the shadow side of our personality." Through the acceptance of it in oneself, the recognition of its existence, the possibility of expressing it, it becomes conscious and possible for presentation. To do this, we need to agree with our "critic", the "social mask" that we wear for others and for ourselves, with the concepts of "good and bad", "right and wrong", "beautiful and ugly".

The second thing that can stop you is the fear of breaking up the relationship. Many prefer not to initiate another into the truth about themselves, as they are afraid of the consequences. Do not rush to fantasize that you with your "bad" trait, history or preference, the other person will not accept. A sincere desire to be together affects the acceptance of you by others.

A sincere desire to be together affects the acceptance of you by others.

When we do not recognize the truth in front of us, it goes into the shadows - that part of the personality that is not realized

Why didn't I break up with Yegor as soon as I met Vlad? I considered my boyfriend an invaluable person for the relationship, the person I love, and refused to admit to myself: he is very boring with him. Besides, I never found it difficult to lie to men. Mom says this is a kind of revenge on dad for his behavior. In fact, it was convenient for me.

The boomerang law was not slow to work: my friend Arina fell in love with Yegor, and they began to communicate. Secret from me. And one day the skeleton from their closet fell out - I saw photos from their wedding on Facebook. It was very painful. Then I learned that one of the most unpleasant feelings associated with lying is when your loved one tries to prove that he is not lying, but you feel: he is lying even now. I was able to forgive Anya only a few years later, when I met my future husband.

I was able to forgive Anya only a few years later, when I met my future husband.

“Lies are most often based on two feelings: fear and shame. Fear of losing relationships, lifestyle, status, respect. And the shame to show some side of yourself, - explains Olga Kornienko. - The habit of lying can begin to form in childhood, when the child really wants something, but his parents do not allow him to. In this case, he is looking for opportunities to get what he wants, avoiding the prohibition and punishment of his parents. And here is born not only the desire for a goal, but also excitement, cunning, adrenaline. In addition, in lies there is also a secret that excites. Especially if you share it with someone.

Lying in adult life is also the result of personal splitting. Shame keeps us from opening up. Some trait of mine is unacceptable, disgusting for another: he will not accept me with this. The level of shame depends on how much you yourself recognize the right to be such, regardless of the opinions of other people.

Only by recognizing all our sides, roles, desires as normal and having the right to life, can we risk telling others about them,” says Olga.

Things were not so easy with my husband either. When on the first date he asked where I live, I lied: I said that I had a friend (then I still lived with Vlad). And for the first time I felt almost physical pain from lying. Something in me has changed. I thought: having learned that I live with a guy, Sasha will not call again. I confessed everything myself - after he invited me to live together.

I knew that I was taking risks, but suddenly I realized that I could not start our relationship with deceit. There was no quarrel - instead of it there was a long silence, which turned out to be worse than a scandal. I tried to explain the reasons for my action, but I saw that I had lost Sasha's trust. He forgave me, although he walked away for a very long time, and during quarrels he kept recalling my deceit. This was my payment. Regardless of the consequences, every skeleton in my closet suddenly stirred and made itself felt. And I couldn't stop. For the first time in my life, I told a man everything about myself: about the terrible attitude towards other guys, about weaknesses, resentments and envy of someone else's success, about complexes due to small breasts and tiny lips, about the persistent fear of my father, about addiction to alcohol and drugs, about sexual preferences, about which she was silent, "because she is ashamed." I was not afraid to open my soul to him and show that not only winged unicorns live in it, but also ugly secrets. It is paradoxical that after that Sasha did not see me as a stranger and did not decide that we were not on the way - he became even closer.

Regardless of the consequences, every skeleton in my closet suddenly stirred and made itself felt. And I couldn't stop. For the first time in my life, I told a man everything about myself: about the terrible attitude towards other guys, about weaknesses, resentments and envy of someone else's success, about complexes due to small breasts and tiny lips, about the persistent fear of my father, about addiction to alcohol and drugs, about sexual preferences, about which she was silent, "because she is ashamed." I was not afraid to open my soul to him and show that not only winged unicorns live in it, but also ugly secrets. It is paradoxical that after that Sasha did not see me as a stranger and did not decide that we were not on the way - he became even closer.

In one day, you can be lied to from ten to two hundred times. We lie to strangers more often than to colleagues.

And most importantly: with his care and support, he gradually fed my inner demons, lured them out and did not allow me to come back. Only by daring to confess my hard-hitting secrets and learning that they love me just like that, no matter what, did I become who I always wanted to appear.

Only by daring to confess my hard-hitting secrets and learning that they love me just like that, no matter what, did I become who I always wanted to appear.

“Yes, somewhere inside each of us lives a childish desire for unconditional love and acceptance by others. We really want to believe that we will always be accepted. But the other also has its own boundaries that we meet. It is also important to notice both your own boundaries and the boundaries of another person. If you can't bear to be like this with me, we don't get along in this place. And can we continue our relationship in this regard? If so, let's agree in what format, so that both you and I feel good in them. And yes, relationships can disappear if the secret becomes a reality, but they can also reach a new level - find something very important that has not happened yet.

Here you should answer the question for yourself: are these relationships really so important to me if I cannot show some side of myself in them?

The cost of lying in intimate relationships is trust and the consequences of its loss; tension and secrecy, lack of spontaneity in some areas of life; the impossibility to share the joy of accepting oneself by another, as well as sharing one’s desires with him, the pleasures that lie in this shadow side of the “I”. You need to weigh the pros and cons of such a relationship. To take a risk and appear, to face fear and shame in order to be able to be just yourself with another,” commented Olga Kornienko.

You need to weigh the pros and cons of such a relationship. To take a risk and appear, to face fear and shame in order to be able to be just yourself with another,” commented Olga Kornienko.

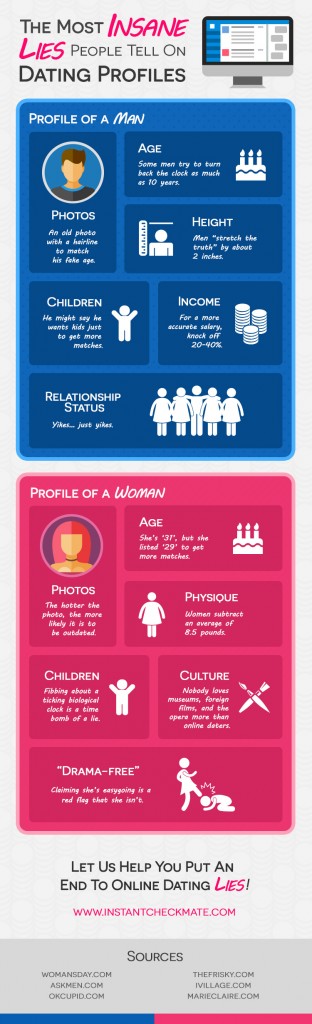

I recently heard from my colleague Alena: “What should I do with the skeletons in the closet? Why do anything with them at all? They lie to themselves - and let them lie. Maybe she's really right? After all, they all lie one way or another. TED has a talk by Pamela Meyer, author of How to Spot a Lie. In particular, she says: “In just one day, according to research, you can lie about ten to two hundred times. We lie to strangers more often than to colleagues. Extroverts lie more often than introverts. Men lie eight times more about themselves than about anyone else. And women use lies as a tool when they need to protect someone. If you are an average married couple, you will cheat on each other one time out of ten. If you're not married, that figure goes up to three out of ten." Lies are an integral part of life - and yours, and mine, and that guy. How do you define the line after which harmless embellishment ends and you enter dangerous territory?

How do you define the line after which harmless embellishment ends and you enter dangerous territory?

When Nicole Kidman's character on Big Little Lies first visits a psychologist without a husband, she asks her direct questions about domestic violence and her fear, and Kidman categorically denies everything, tearfully listing the qualities she values in husband. So she tries to avoid sudden shame and the truth that she hid from herself. At this moment, you understand: self-deception is one of the most terrible types of lies.

Another hero of the same series claimed that all married couples pretend, even the happiest ones. Is it so? A friend of mine adds: “Only those families in which partners lie to each other can be happy and strong.” His philosophy is simple: you can save a marriage for many years if you tell your partner only what can bring joy to your life together. Everything that overshadows the relationship, away. This also applies to the truth, which my interlocutor carefully hides and does not give out even in metered portions. He and his wife have two children and have been married for over fifteen years. And both spouses are really happy. Agree, there is reason for reflection. But it seems to me that this requires two mandatory conditions: the lack of conscience in one and curiosity in the second.

He and his wife have two children and have been married for over fifteen years. And both spouses are really happy. Agree, there is reason for reflection. But it seems to me that this requires two mandatory conditions: the lack of conscience in one and curiosity in the second.

I recently read a similar thought in Tamriko Sholi's book "Inside a Man". One of the characters with whom the author spoke tells how he loves his wife and at the same time cheats on her. But remorse does not oppress him. He admits that he thought for a long time about why he needed to sleep with other women, and realized that this is his nature, which cannot be changed. It's that simple. Of the hundreds of betrayals, his wife accidentally found out about one, but even the fear of losing her kept him from casual relationships for only a year. Maybe some people are simply incapable of loving anyone other than themselves?

"Of course I'll lie to them if they refuse to understand me!" - admits my cousin Anya, who, secretly from her parents who control her around the clock, got two tattoos, tried smoking and had sex. Probably, when you feel that your desires are respected, and you are loved without any conditions, you will not want to act contrary and contrary.

Probably, when you feel that your desires are respected, and you are loved without any conditions, you will not want to act contrary and contrary.

I wonder if the number of skeletons falling out of the closet depends on how honest we ourselves are with others? Or does this factor have nothing to do with our attitude towards people? Perhaps we need to become those with whom we want to be extremely honest - able to understand a loved one in any situation, not trying to get into his personal space, not giving unsolicited advice, not criticizing his choice - and then we will protect ourselves from lied? Don't know. It seems to me that in every relationship at least once your loved one will do something that he wants to hide from you. Not because he does not respect, does not appreciate you and does not value your relationship, but out of fear of losing your feelings and trust. That is why we are endowed with the talent to forgive. Those who have mastered it are the happiest people in the world.

Tags: lies, relationships, psychology

Intervene or remain silent? Aristotle version

Do you protest when you see parents hitting or yelling at their children? Silence when a muscular insolent person passes without a queue, pushing a frail pensioner? Or when a young healthy guy does not give up his seat on the subway to a pregnant woman? Aristotle equated moral inaction with complicity and said that on our deathbed we will not regret what we have done, but, on the contrary, what we have not done. T&P publishes an excerpt from Edith Hall's book "Happiness According to Aristotle" - about how epikeia, which the philosopher considered an integral part of absolute justice, can help us in the process of making important decisions.

Happiness according to Aristotle. How Ancient Philosophy Can Change Your Life

Edith Hall

Alpina non-fiction. 2019

[…] For Aristotle, the most important thing is an independent, independent person, free in his decision to act “justly”, even if everyone around behaves inappropriately. Perhaps these ideas developed partly in opposition to the endless strife that the philosopher observed at the magnificent Macedonian court at Pella in his own childhood and later, in 343-336. BC, when he raised Alexander. Struggle for power, murders, extortion, coercion, conspiracies, deceit, painful fears... But Aristotle managed to remain himself.

Perhaps these ideas developed partly in opposition to the endless strife that the philosopher observed at the magnificent Macedonian court at Pella in his own childhood and later, in 343-336. BC, when he raised Alexander. Struggle for power, murders, extortion, coercion, conspiracies, deceit, painful fears... But Aristotle managed to remain himself.

Perhaps the most difficult moral choice is to intervene or do nothing.

You are worried about a neighbor's child who seems to be being beaten. What to do - inform the guardianship service or keep silent, what if you made a mistake? Your co-worker is wasting corporate funds. Notify management or keep your mouth shut so that they don't consider you a snitch? The dilemma plays a pivotal role in Jonathan Kaplan's The Accused (1998), which for the first time in cinematic history highlights the unfair treatment of victims of sexual assault who seek redress. Four college students rape a working-class woman in a bar. A friend of one of them, although shocked by what is happening before his eyes, does not interfere in any way and does not try to stop the crime. However, he still calls the rescue service and notifies the police. His testimony will then play a big role in the investigation.

A friend of one of them, although shocked by what is happening before his eyes, does not interfere in any way and does not try to stop the crime. However, he still calls the rescue service and notifies the police. His testimony will then play a big role in the investigation.

Aristotle was the first of the ethical philosophers to understand that an unrighteous act can be not only action, but also inaction. He cites the most striking example in Book III of the Nicomachean Ethics:

. Therefore, if it depends on us to perform an act when it is beautiful, then it is up to us not to perform it when it is shameful.

The price of this choice is much higher today than it was in Aristotle's time. Although the ancient Greeks also had the concept of unsolicited interference, people who believed that their cause was the side were looked askance. If in our time, quiet ones cause, unlike troublemakers, rather approval, then the ancient Greeks considered detachment to be selfishness and irresponsibility, evasion from civic duties. Our vocabulary itself, which describes an initiative or intervention to restore order and eliminate injustice, often has a negative connotation. Leadership is often perceived as self-promotion or careerism. In our language, there are almost no verbs that mean interference in a positive sense, with rare exceptions like "intercede", but there are plenty of designations for condemned interference - "intrude", "get confused", "meddle in one's own business". It is even more difficult for women, who from time immemorial have been taught to “keep a low profile”, encouraging modesty and invisibility as opposed to participation in public or state affairs.

Our vocabulary itself, which describes an initiative or intervention to restore order and eliminate injustice, often has a negative connotation. Leadership is often perceived as self-promotion or careerism. In our language, there are almost no verbs that mean interference in a positive sense, with rare exceptions like "intercede", but there are plenty of designations for condemned interference - "intrude", "get confused", "meddle in one's own business". It is even more difficult for women, who from time immemorial have been taught to “keep a low profile”, encouraging modesty and invisibility as opposed to participation in public or state affairs.

In childhood, we all had to choose between intervening or remaining silent, becoming, in fact, accomplices when “unpopular” children were persecuted in front of our eyes. We find ourselves in similar situations in adult life. […]

It is not easy to intervene because the standard defensive reaction to third-party interference is: “Do you need it most?” or “And who appointed you as the vice police?” The question is what worries you more - the opinion of these people who spit on the norms of morality and justice, or the outrage that is happening. […]

[…]

Nowadays, the vast majority of ethical requirements and, accordingly, claims - especially against public figures - are made in relation to an action, that is, mistakes or misconduct. Politicians are criticized for taking wrong steps and very rarely for what they didn't do to improve the lot of the people. We do not ask politicians, general directors, rectors, chairmen of foundations enough for inaction, for programs that have not been implemented and, accordingly, for evading official duties. As the legend says, Alexander the Great, if he, as a ruler, did not manage to accomplish anything useful and constructive in a day, woefully declared that "today he did not rule." He probably learned about the dilemma of inaction from his mentor Aristotle.

Since the time of Aristotle, philosophers have illustrated this dilemma with odious hypothetical examples - a man who can swim did not save a drowning man; the rich, although they do not try to suppress the rebellion of the poor by force, allow the poor to die of starvation; one parent does not complain about the other abusing their child.

According to Aristotelian principles, harmful inaction also includes the unwillingness to take responsibility.

To understand what “guilty omission expressed in failure to accept responsibility” is, the easiest way is to look at how criminal omission is interpreted by the law - and the legislation in this area differs from country to country.

While it is a crime in Britain to intentionally conceal taxable income and assets, as well as to deliberately conceal information relating to terrorist activity, liability for failure to act has long been hard to establish in British law. The legal picture reflects the attitude towards privacy and civic passivity inherent in the British mentality. The famous “My home is my castle” is still held up as an ideal and prevents the reform of the law and police procedures in relation to marital rape, child punishment and “domestic violence” (a disgusting expression, implying that such violence is somehow qualitatively different from that committed strangers on the street or in a pub). But even in Britain there are several types of legal situations in which failure to act would be considered criminal.

Relationships impose certain obligations on the participants in relation to relatives. A parent can be held liable if a child is injured or killed due to lack of proper care. There are cases when close relatives who lived with the deceased and left him without the required medical care were found guilty of "causing death by negligence". Criminal liability may also arise in case of non-compliance with the terms of the contract: let's say you were hired to work as a lifeguard at the pool and someone drowned while you were away for a smoke break. There is a high probability of being sued for creating a dangerous situation and a threat to the lives of other people: for example, if you left the house during a fire that happened through your fault - albeit unintentionally - and did not call the firefighters, although you knew that there were still people in the house .

Even in such seemingly unambiguous situations, the line between negligence (even criminal) and deliberate inaction looks blurred, and Aristotle knew this very well. If bank employees or the owner of the rented apartment do not provide the police with information regarding the financial activities or residence of possible terrorists, is this a deliberate concealment or are they simply not up to it? How to figure out if a mother is intentionally starving a child - with a fatal outcome - or "simply" neglecting her duties, especially if her capacity as a breadwinner is reduced due to addictions, low intelligence or mental illness? Aristotle would definitely call for evaluating, first of all, the degree of intentionality. I suspect, however, that British law would have seemed woefully incomplete to him in regard to inaction. For example, it is still completely unclear whether other adults (other than the child's parents) who knew about what was happening should be held responsible for concealing information about (alleged) abuse of a child.

Such extremes, fortunately, are far from most of us, but there are, for example, dozens of people who have lost their jobs or at least have a chance of being promoted because of their indifference - those who, in the public interest, made public information that discredits people or the orders of employer. Cardiologist Raj Mattu won an unfair dismissal case in 2014. In 2010, he was fired, after being suspended from practice for eight years, for releasing data confirming that a reduction in funding in one of the Coventry hospitals was leading to overcrowding, which posed a mortal threat to patients. The NHS officials went to great lengths to silence Matta. They hired private detectives who looked for compromising evidence on him, spent millions of pounds on court cases - Raja Matta was deprived of a source of income, his career, reputation, health and personal life were ruined. He took responsibility and dared to act when, in the words of Aristotle, "it was impossible to remain inactive. " A brave man worthy of admiration. Not all of us would find the courage in ourselves - and besides, we may have other people on our payroll, which does not allow us to risk work for the sake of principles. In such cases, you have to choose which of the obligations is more important.

What if the situation is not so extreme and you do not face big losses?

Aristotle firmly believes that certain virtuous acts require connections, finances, or political power.

Accordingly, inaction on the part of a person who has such "insurance" is much more reprehensible. Assessing the activities of millionaires, celebrities, politicians, aristocrats, and even your immediate superiors, do not limit yourself to finding out if they became participants in any scandals. Find out what kind of charitable work they do, for what and how they fight - in other words, how they use their huge social advantages and leverage. Many famous and prosperous people have never stood up for either the poor or the oppressed. The ability to think not only about participation, but also about indifference allows you to get a more complete and objective picture of a person.

Aristotle also considers the need to take into account intentions in relation to the dilemma of ends and means. The argument that there are situations in which the desired can be achieved only by reprehensible means leads us into one of the most "gray" ethical areas of philosophy. This is how many military actions are justified, in particular the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: to sacrifice tens of thousands in order to prevent much more casualties in the event of a large-scale ground operation on Japanese territory. The problem is that now it is impossible to find out how events would have developed if the atomic bombing had not happened. Truman's chief of staff, Admiral of the Navy William Daniel Leahy, concluded that "the use of these barbaric weapons in Hiroshima and Nagasaki did not bring significant benefit in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender as a result of an effective naval blockade and successful conventional bombardment."

This event had another tragic consequence: the use of nuclear weapons dramatically accelerated the Cold War arms race. However,

Aristotle would judge the decision to bombard primarily on intentions, not results.

Is this a military measure or a political one? Many of those who criticize the bombing of the civilian population of two Japanese cities that did not have strategic importance argue that if President Truman could really be convinced that these actions would avoid much more death and destruction, then his Washington advisers were driven, above all, by the desire test new technologies (although these people were horrified by the unexpected number of victims of radiation sickness) and threaten Stalin and the USSR. Perhaps Truman should have been more suspicious of the intentions of his advisers. […]

The dilemma between the means and the end almost every day confronts each of us when we decide whether to tell the truth. Lies cause stress, which even affects the physical state - this is the basis of the principle of the lie detector. Therefore, in different cultures, it is believed that although deception is acceptable in a number of situations, in general, lying is more expensive for yourself. It rarely contributes to the happiness of both the deceiver and the one with whom the deceiver comes in contact. This intuitive notion finds theoretical support in Aristotelian ethics. Aristotle's reasoning about truth and falsehood is quite complex. He does not believe, like Plato, that there is some kind of transcendental truth, does not endow it with a metaphysical status and does not consider it as a good in itself. But he considers one of the conditions for a happy life to be the development and consistent application of principles regarding honesty and hypocrisy.

Aristotle has the notion of a "straight man", "honest with himself" ( authekastos - "such as he is"). This is a person who is whole and consistent, self-sufficient, he treats everyone equally and does not depend on the opinions of others. In this, he approaches the ideal of "greatness of the soul", to "openly expressing their likes and dislikes", to those for whom "truth is more precious than someone else's opinion". When a person knows that he will not have to blush for any letter, comment or post on social networks, he sleeps much more peacefully at night. Telling the one and only true version of events everywhere is much easier than remembering which fiction you fed to whom. It would be prudent never to say or write anything that you are not ready to make public. One of my colleagues, having opened up in a pub with a colleague, began to scold the management. The interlocutor threatened to go to the boss and convey everything he heard to him, to which the colleague said: “Forward!” - because she had already expressed everything to the boss in much stronger terms.

A person striving to observe the Aristotelian principles of a happy life will not lie in a truly critical situation (for example, in court - that is, in a more official setting than communication with relatives and friends). In such a situation, a lie will be meanness, which, in the understanding of Aristotle, is inseparable from injustice. So, for example, a builder lies to get more money out of an employer: he demands time payment, not piecework, promising that the work will take a month, when in fact it will take at least two. The employer, in turn, may lie to the IRS in order not to pay tax on the money owed to the builder. In both cases, this is not even just a lie, but something more pernicious - an element of injustice. This is a component of a process that harms not only its participants, but also society as a whole.

Truthfulness as a vital principle, even in situations not so critical, interests Aristotle no less. He closely studied those who embellish the truth for the sake of boasting (self-promotion was a prominent component of masculinity among the ancient Greeks, and to what extent it is permissible to exaggerate one's own achievements and exploits, the Iliad says a lot). Bragging, even based on lies, can be quite harmless if it's just a performance for casual interlocutors and hated acquaintances over a glass of beer in a pub. However, boasting can also have serious consequences - it is unlikely, for example, that someone would want to get on the operating table to a surgeon who overestimates his qualifications. But Aristotle is occupied with fabrications that are banal at first glance, with the help of which a braggart gains his own worth: “Whoever ascribes to himself more than he has, without any purpose, is like a bad person (otherwise he would not rejoice at deceit), but he seems more empty than vicious." […]

But does Aristotle consider truth to be a self-valued good? He does not say that the adherent of the principles of a wonderful life will never need to cheat anywhere. He thinks more practically:

it is more profitable to tell the truth from the point of view of reasonable egoism.

So, for example, a person who is by nature truthful and honest in everyday situations, most likely will not let you down and will not deceive in a critical situation. “Whoever is truthful and truthful, even when it is not important, will be all the more truthful when it is important, because he will certainly beware of deceit as a shame, if he is already wary of it as such. ” By accustoming yourself to honesty, you are much more likely to tell the truth and where it will be fundamentally important for you personally and for others. The reputation of an honest and truthful person will eventually bear fruit: in a decisive situation, everyone will know that your word can be trusted. […]

In the time of Aristotle, religion taught that punishment was inevitable. Justice among the ancients was designated by the term dike and meant the law approved by the supreme god Zeus: in the tragedy, it is dike that obliges Orestes to deal with his mother for the murder of his father, without taking into account any accompanying circumstances. One of the heroes of the tragedies of Sophocles exclaims: “Which god will you fall into the hands of! / He knows neither love nor addiction, / Simple only following the Truth. The most obvious example of the modern imposition of harsh and therefore controversial laws is prison terms, which do not allow the judge to consider extenuating circumstances and impose a sentence in accordance with the epicae principle. Which, in turn, sometimes leads to a "riot" of the jury, who refuse to pass a verdict of guilt, knowing that, from a formal point of view, the defendant committed a crime.

A few years ago, in England, a jury acquitted a man accused of murder, although the defendant admitted that he had really dealt with a resident of a neighboring street who took the life of his daughter. Due to violations in the conduct of the investigation and the loss of evidence, it turned out to be impossible to sentence the killer of the child to life imprisonment, so the grief-stricken father decided to "take justice into his own hands." The jury in this case acts as a collective voice of reason, realizing what scope for injustice creates the application of uniform measures without taking into account individual circumstances. The jurors act according to the principle of epikeia, showing prudent flexibility in issuing a verdict in order to avoid injustice, which the creators of the law did not foresee and did not intend (in this case, the sentence to the unfortunate father who suffered from the incompetence of the investigation). Epikeia is an indispensable and integral component of absolute justice.

The Aristotelian term epieikeia comes from the root eikos , meaning "allowable", "acceptable". The punishment should be proportionate to the guilt, and not the guilt should be adjusted to the measure of punishment, as Procrustes adjusted everyone who did not fit on it to his bed, either by stretching out the legs of the victims or chopping off the excess. But in the time of Aristotle , epieikeia was already beginning to acquire a different meaning among the Greeks, connected with the verb "submit, yield." That is, in general, epikea meant flexibility, concession to mitigating circumstances. However, in the history of law, one significant case is known, where the epic had to turn to, because the letter of the law, on the contrary, did not allow punishing the criminal to the fullest extent.

In 1880, Francis Palmer bequeathed almost all of his fortune to his grandson Elmer, until whose age the money was to be in the care of Elmer's mother. At 16, fearing that his grandfather would change his will, Elmer poisoned Francis. But if they could have imprisoned him for the murder, then the laws of the state of New York could not prevent the poisoner from receiving the due under the will in due time. Therefore, in 1889, Elmer's mother challenged the will in a civil court, and, guided by the Aristotelian principle of epikeia, the jury decided by a majority in her favor.

The strongest argument against epikeia is that we cannot be completely sure of the prudence and adequacy of those who apply it. If one of the tasks of the law is to promote universal equality, we need to look very carefully at how and in what we "rot" it according to the circumstances. Most precisely, he spoke on this subject in the 17th century. historian and parliamentarian John Selden, who called the epicae "crazy" and "proportionate to the conscience of a judge." After all, we don’t establish, he explains his thought, as a measure of length the size of the judge’s foot, because the legs of all judges are different: “one foot is longer, the other is shorter, the third one is neither, that’s the same with conscience” . But Aristotle would object that

there is no reason for humanity to refuse the good of true justice just because someone falls short of the high moral standards

set by the epic. In conclusion, Aristotle emphasizes that epicaea, justice, as well as the ability to make a balanced judgment, are purely human qualities. To wayward gods from ancient Greek mythology, it is incomprehensible, alien, and even, perhaps, would seem ridiculous.

Any juror, justice of the peace, teacher, inspector, anyone whose line of work involves making decisions related to rewarding merit, punishing offenses, or evaluating competence will undoubtedly benefit from such a precision instrument. Epikea can be useful for parents, especially if they have to provide for the needs of several children. For example, it seems to us that justice requires equal distribution of the acquired between two children, but in fact, if one of them is incapacitated and needs lifelong care, truly equal care will be expressed in taking into account the individual circumstances of each.