People saying yes

Why you say yes to requests – even if you shouldn't

Loading

How we think

(Image credit: Getty Images)

By David Robson

19th November 2021

People have a hard time saying no, for fear of disagreement. Influencers can use this power for good – or bad.

W

While working as a graduate student in New York City, Vanessa Bohns was given the dreaded job of collecting survey data in Penn Station as part of an academic research project. Each time she approached a passer-by, she expected to hear a sigh of exasperation or a muttered insult. Yet the bad responses rarely came; many more people were willing to answer the questionnaires than she had expected.

Was it possible, she wondered, that most of us underestimate others’ willingness to respond to our requests? Over the following decade, she conducted multiple studies that confirmed that this was indeed the case: in many different situations, people are often far more likely to cooperate than we assume.

Superficially, her results seemed to provide a refreshingly optimistic view of human nature. “It started as a positive thing, like, isn't it great that people are more likely to do things for you than you think?” Bohns has since come to appreciate that her results reflect a broader tendency for us to underestimate how much influence our words can have over others, whether we’re asking them to perform good actions or bad ones. Often, people are only complying with us because they find it too awkward to say no, even when they feel uncomfortable with our requests.

Understanding this can help us understand how our requests might affect other people – particularly in the workplace – and adjust them accordingly, in ways that respect people’s boundaries.

Testing our helpfulness

Bohns’ work – which she’s now turned into a new book, You Have More Influence Than You Think – builds on research by Ellen Langer at Harvard University from the 1970s. In her study, participants attempted to jump the queue for the photocopier at the university library. As you might hope, a large number agreed if the person making the request had a good excuse. Ninety-four per cent of people allowed them to go ahead if the participant said they were “in a rush” – compared to 60% when the person offered no reason for their request.

As you might hope, a large number agreed if the person making the request had a good excuse. Ninety-four per cent of people allowed them to go ahead if the participant said they were “in a rush” – compared to 60% when the person offered no reason for their request.

Strikingly, however, almost as many people – 93% – allowed the participant to go forward if they said that they “need[ed] to make some copies”, which is really no excuse at all. The experiment suggested that people don’t pay attention to the details of what someone says, and they can therefore be swayed by a superficial explanation. “As long as something follows a general script, we're not necessarily going to process whether it makes sense. We just go along with it,” says Bohns, who is now a professor in organisational behaviour at Cornell University, US.

In Vanessa Bohns's research, she found a large majority of people would let others cut in line for photocopies, even without a good excuse (Credit: Getty Images)

Bohns’s own research on influence and compliance began in the late 2000s. The first experiment attempted to replicate her own experience in Penn Station: the participants had to approach strangers on the university campus and ask them to complete a survey. All they could say was “Will you fill out a questionnaire?” To get five responses, most people estimated that they’d need to ask at least 20 people. In practice, that number was closer to 10.

The first experiment attempted to replicate her own experience in Penn Station: the participants had to approach strangers on the university campus and ask them to complete a survey. All they could say was “Will you fill out a questionnaire?” To get five responses, most people estimated that they’d need to ask at least 20 people. In practice, that number was closer to 10.

In another experiment, the participants leaving the lab had to ask a stranger to walk them to a nearby gym, explaining that they couldn’t find it. On average, the participants assumed that they’d have to approach about seven people before someone would agree to take the detour. When they performed the task, however, they found that around one in every two people offered to go out of their way to help. “They would go out looking scared and sometimes kind of angry that they had to do this,” says Bohns. “And then they would return much earlier than expected, and bounce back into the lab.”

To test the phenomenon in a natural setting, among a more diverse group of participants who were not university students, Bohns questioned people raising money for the Leukaemia and Lymphoma Society. On average, the volunteers predicted that they’d need to ask around 210 people to meet their fundraising goals of between $2,100 and $5,000. In reality, they were able to contact just 122 people to reach their target.

On average, the volunteers predicted that they’d need to ask around 210 people to meet their fundraising goals of between $2,100 and $5,000. In reality, they were able to contact just 122 people to reach their target.

Avoiding awkwardness

It is easy to understand why Bohns and her colleagues were so excited about these initial results: knowing about people’s willingness to help could give us more confidence when managing work projects, for example.

A few years into the research, however, she decided to test whether we might also use our influence unethically, without realising how easily others would be swayed by our demands, or how uncomfortable they would feel saying no.

For one experiment, she gave participants fake library books. The participants were asked to approach strangers with the following request: “Hi, I’m trying to play a prank on someone, but they know my handwriting. Will you just quickly write the word ‘pickle’ on this page of this library book?”

Bohns suspected that very few people would agree, and the participants were similarly sceptical. But, as with the questionnaire study, those predictions proved to be wrong. Despite raising some objections, more than half the people that the participants approached agreed to commit the small act of vandalism.

But, as with the questionnaire study, those predictions proved to be wrong. Despite raising some objections, more than half the people that the participants approached agreed to commit the small act of vandalism.

This was not an isolated incident; another of Bohns’s studies found people were willing to falsify academic documents upon a simple request from a stranger. And she found similar patterns using an online platform, in which participants had to consider their reactions to various scenarios. The subjects reported they would be more comfortable committing an unethical act if someone told them to do so. Yet, they consistently underestimated how much their own words could influence someone else’s decision.

Why would this be? Bohns now suspects that people often comply with our requests due to a fear of disagreement. “We’re a social species, and we don't want to do things that risk damaging our relationships,” she says. In particular, we may fear that by saying no, we are somehow suggesting that the other person is themself immoral or selfish, leading them to lose ‘face’ – a phenomenon known as ‘insinuation anxiety’. “It would make it really awkward for both people,” says Bohns. “So, we might hint that we don't feel comfortable with something, but it's a lot harder to actually come out and say no, I'm not going to do it.”

“It would make it really awkward for both people,” says Bohns. “So, we might hint that we don't feel comfortable with something, but it's a lot harder to actually come out and say no, I'm not going to do it.”

This is the reality. When we are asked to predict how someone will react to a request, however, we discount their fear of embarrassment and assume the other person would be more courageous than they really are – which leads us to underestimate our potential power to persuade others to act against their better nature.

Leave room for refusal

Bohns believes that our tendency to underestimate our influence is very relevant in the workplace. If you ask a colleague to do you a favour by cutting corners in their work, for example, you may assume that they can just refuse, but their fear of creating awkwardness could prevent them from doing so.

Our tendency to underestimate our influence is very relevant in the workplace – and we can convince colleagues to do things like cut corners (Credit: Getty Images)

It’s worth emphasising that these are general patterns. Individual differences in people’s influence, and their perception of that power, will of course depend on many factors and the specific context of the situation.

Individual differences in people’s influence, and their perception of that power, will of course depend on many factors and the specific context of the situation.

In Bohns’s studies, the participants were almost always of equal stature. Clearly power dynamics will play an important role, though: by definition, people of higher status should have more influence over people of lower status within a hierarchy. Importantly, Bohns’s research suggests that these people may not realise how uncomfortable someone will feel about saying no to their demands. The upshot is that they may end up asking too much of their junior colleagues without even meaning to abuse their position.

Bohns believes that in many situations we should actively create opportunities for others to disagree with us. This may mean that we change the medium through which we make our requests. People are more likely to respond positively to your request if you ask them in person or over the phone, whereas they could feel more comfortable turning you down by email.

You may still decide that you’d like to make the request face to face, of course – perhaps it feels more polite or will allow you to explain your case in more detail – but you could at least give the person the time to mull it over and to respond at a later point. “You can give the person a little more space to gather their thoughts,” she says.

Ian MacRae, a work psychologist and author of the recent book Dark Social: The Darker Side of Work, Personality and Social Media, says he is very interested in Bohns’s research. He agrees that allowing room for disagreement is essential. In his opinion, managers should be especially wary about making a request in public, since that will make it even harder for the employee to say no. “That’s going to build up resentment and have negative consequences later on.”

And if you’re the worker who ends up having to decline a request, MacRae suggests that you might dissipate the awkwardness by thanking your colleague for the opportunity and by giving a constructive reason for your refusal. Imagine your boss has sprung a last-minute task on you that is going to be nearly impossible to complete without a huge amount of stress. “You might say that you’re really glad they thought you were capable of doing the task, and that in the future you’d be happy to do it, but you’d need ‘X’ days’ notice, or that you’d need extra resources to do so effectively,” says MacRae. “That way it’s not so much of a rebuff – it’s a conversation about how you can get it done.”

Imagine your boss has sprung a last-minute task on you that is going to be nearly impossible to complete without a huge amount of stress. “You might say that you’re really glad they thought you were capable of doing the task, and that in the future you’d be happy to do it, but you’d need ‘X’ days’ notice, or that you’d need extra resources to do so effectively,” says MacRae. “That way it’s not so much of a rebuff – it’s a conversation about how you can get it done.”

With the publication of her book, Bohns hopes that we’ll all become more aware of the ways our words affect others – and our tendency to underestimate the difficulty of refusal – so that we’re more readily respectful of their boundaries. “If we want genuine agreement, we should always be thinking of the ways that we can make it easier for others to say no.”

Our influence may often be invisible to us, but with a bit of training we could all wield that power with more compassion and responsibility.

David Robson is a science writer and author based in London, UK. His next book, The Expectation Effect: How Your Mindset Can Transform Your Life will be published by Canongate and Henry Holt in early 2022. He is @d_a_robson on Twitter.

His next book, The Expectation Effect: How Your Mindset Can Transform Your Life will be published by Canongate and Henry Holt in early 2022. He is @d_a_robson on Twitter.

Positives and Potential Pitfalls of Saying Yes

For students who are in graduate school, saying “yes,” can feel like a must. Graduate school, for most, was our identity, life, and job. Upon graduation, our roles change, we further develop our professional identity and our hours change. In this new chapter of our lives, as early career psychologists, saying yes becomes a choice. We are no longer matched; we not only choose our place of employment, we have more control over our role at our job. Thus, we do not have to feel the pressure to say yes to boost our curriculum vitae or impress an advisor (Toor, 2010). However, navigating this transition can be challenging for some; therefore, here are some points to consider in helping us when deciding whether to say yes.

Saying yes can influence numerous areas of our professional and personal lives. Deciding whether a yes is warranted requires deciding how much of an impact such an obligation would have on our lives. Therefore, it is important to consider the outcomes when making that choice. Before moving forward, we need to start this discussion by saying it is okay to say no. For some people, no is a “four-letter word,” but this reflection is about giving us the freedom to say no by focusing on when to say yes. So, as early career psychologists, we will have multiple chances to say yes. Examining why and when we will say yes can increase the fruitfulness of the times when we decide to say yes. Similarly, as we move from early career psychologists towards becoming mid-career psychologists with more ease defining our direction (Markin, 2014), we can use our current vision for ourselves to help guide which opportunities to which we say yes.

Deciding whether a yes is warranted requires deciding how much of an impact such an obligation would have on our lives. Therefore, it is important to consider the outcomes when making that choice. Before moving forward, we need to start this discussion by saying it is okay to say no. For some people, no is a “four-letter word,” but this reflection is about giving us the freedom to say no by focusing on when to say yes. So, as early career psychologists, we will have multiple chances to say yes. Examining why and when we will say yes can increase the fruitfulness of the times when we decide to say yes. Similarly, as we move from early career psychologists towards becoming mid-career psychologists with more ease defining our direction (Markin, 2014), we can use our current vision for ourselves to help guide which opportunities to which we say yes.

Positives

To begin, we should look at all the positives that can come from agreeing to take something on—such as how saying yes can help us in achieving our career goals, building relationships, and increasing personal growth. In addition, saying yes can be personally rewarding, as well.

In addition, saying yes can be personally rewarding, as well.

First, saying yes can build relationships within our places of employment, increase referrals, and give us a greater presence in our communities. An ECP may benefit from both current and future prospects from these relationships. By networking, we can open new pathways for our careers, research, and mentorship. Thus, we should ask, “where does saying yes take me?” Accepting opportunities can help us garner more administrative exposure as well as help us gain more responsibility in our workplaces. Consider saying yes when it gives you the chance for career advancement in a desired direction. For example, McCarthy’s (2014) advice to “never turn down the opportunity to give a talk” (p. 27) rings true when discussing the importance of saying yes. This is due to the multiple ways presenting can benefit us outside of the presentation itself, which can include networking, demonstrating expertise, and personal growth. New career doors or possibilities for advancement might be other benefits from saying yes.

Knowing about and reflecting on these benefits is an important step in making decisions about how to spend one’s professional development time as an ECP. “Yes” could allow us to be a part of an important grant, obtain a teaching position, or offer other unique experiences that could have substantial positive effects on our careers.

Next, we are in this field to do many things, personally and professionally, but the cornerstone of our field is changing people’s lives and having a positive impact on others. Therefore, when yes involves impacting others in a significant way, saying yes should be easier. Whether yes is volunteering at a soup kitchen or participating in awareness walks, our presence and empathy can greatly impact individuals’ lives. Think about the talents we have to offer as professionals in this field: By saying yes to certain things, we are able to use those talents/skills/expertise to improve others’ lives.

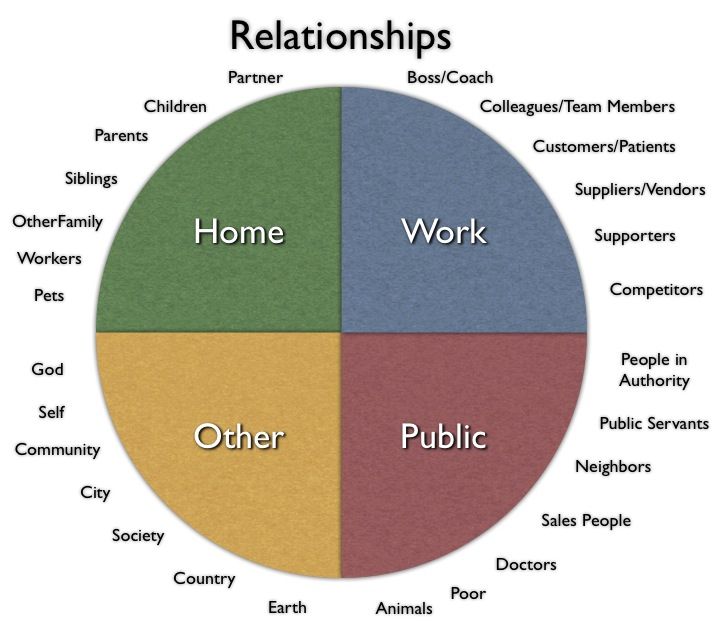

We should also ask ourselves if saying yes will expose us to new cultures, values, and diversity in experience.![]() These kinds of opportunities will assist in our cultural competence and broaden our experiences with differing or new worldviews. Understanding and appreciating other cultures is a positive result from saying yes, and recognizing this as a chance to give and learn is a major benefit professionally and personally.

These kinds of opportunities will assist in our cultural competence and broaden our experiences with differing or new worldviews. Understanding and appreciating other cultures is a positive result from saying yes, and recognizing this as a chance to give and learn is a major benefit professionally and personally.

Finally, saying yes has an impact on who we are as a person. In addition to the impact we can have on others, saying yes can have a positive impact on us individually. The right opportunity might help us overcome confidence hurdles, self-doubt, and imposter feelings. “Yes” can allow us to further build/apply our expertise in areas we have developed, show our willingness to be team players, and help cement our professional identities. As McCarthy (2014) noted, saying yes to talks allows individuals to deeply engage in their own expertise and changes individuals on a professional level, which then can be generalized to other situations.

Therefore, there are significant reasons why we would benefit from saying yes, which can include career advancement, creating new career opportunities, networking, increasing diversity experiences, positively impacting others, and growing personally as well as professionally. There are multiple reasons to say yes, and these should be considered carefully when opportunities arise. However, like every coin there is another side. Therefore, other aspects of our decision-making should be explored to better understand the limits for when we say yes.

There are multiple reasons to say yes, and these should be considered carefully when opportunities arise. However, like every coin there is another side. Therefore, other aspects of our decision-making should be explored to better understand the limits for when we say yes.

Potential Pitfalls

When thinking about all the reasons to say yes, ECPs should also think about any potential pitfalls from doing so. First, how are we going to plan self-care after saying yes? Are there time-related issues which would result in us feeling pressured, burned out, or rushed to a final product? We must also consider how this new responsibility may take us away from other regularly assigned duties or responsibilities at our main place of employment. Then, we should contemplate whether the tasks to which we are saying yes are reasonable or may take more time than available or pull us away from personal and professional goals. If so, would we feel comfortable saying yes?

In addition to the impact saying yes can have on us, we must also think about how it impacts our significant others and family—which may outweigh the benefits of saying yes. Is it possible to say yes and maintain our healthy relationships? We will need to plan how to work this new opportunity into our lives in a way that does not create ruptures or undue stress on our relationships. Consequently, thinking about how saying yes would impact our relationships is vital and must be something to consider.

Is it possible to say yes and maintain our healthy relationships? We will need to plan how to work this new opportunity into our lives in a way that does not create ruptures or undue stress on our relationships. Consequently, thinking about how saying yes would impact our relationships is vital and must be something to consider.

Before agreeing to a new obligation, we should ask: Does the time commitment take up weekends or nights, and will there be increased stress from work? If we still say yes to the opportunity, we will have to think about how it fits into our personal lives. This is important because multiple factors in a psychologist’s life, such as work-life balance and spending time with family and friends, have been found to impact psychologists’ level of satisfaction in their careers (Rupert, Stevanovic, Tuminello Hartman, Bryant, & Miller, 2012). We will need to find ways to integrate the additional task into our balance between work and our personal lives. Thus, consider how long the commitment is to the task. Is the experience temporary or is it a shift in roles? These considerations help inform us about potential issues with time commitments and how new commitments may impact our lives.

Is the experience temporary or is it a shift in roles? These considerations help inform us about potential issues with time commitments and how new commitments may impact our lives.

Finally, as ECPs we must be mindful of any ethical issues or dilemmas that may result from responding with a yes. We must be conscious of any blind spots the requesting person (or we) may have about any ethical issues that are present or could arise. We should ask, is the person making the request someone who passes the buck? A mentor or possible mentor? And does this individual have our best interests in mind? The role of the person doing the asking in relation to our existing job structure can indicate something about the priority of the task, the value of what is being requested, and the impact yes (or no) might have on our organizations as a whole.

Conclusion

As ECPs, we must consider what will be the end result of saying yes. Is saying yes in line with our career goals and aspirations? Knowing what the end will look like can give us greater insight into the value and worth of the task we are considering to engage in to grow. We then will be better equipped in planning and knowing how impactful our endeavors will be for us. Thus, saying yes has many advantages and knowing when to say yes can maximize those benefits. Considering when and why we are saying yes allows us to feel confident in our decisions to say no. Thinking about yes gives us options, and knowing we have those choices is empowering at this stage of our careers. Examining all the positives and potential pitfalls of saying yes gives us more data points and a better idea of possible outcomes. So, good luck with your decision-making and may you be successful in all the future opportunities you choose to take.

We then will be better equipped in planning and knowing how impactful our endeavors will be for us. Thus, saying yes has many advantages and knowing when to say yes can maximize those benefits. Considering when and why we are saying yes allows us to feel confident in our decisions to say no. Thinking about yes gives us options, and knowing we have those choices is empowering at this stage of our careers. Examining all the positives and potential pitfalls of saying yes gives us more data points and a better idea of possible outcomes. So, good luck with your decision-making and may you be successful in all the future opportunities you choose to take.

+2

0

Why do people say "yes"

Why do people say "yes"? If this question sounds rhetorical to you, ask it again.

The answer must be sought daily and hourly. Especially if you are a marketer.

I was inspired by the ideologist and CEO of Meclabs, Dr. Flint McGlaughlin, one of the most experienced Internet marketers I have met, and just a good person.

Flint McGlaughlin, one of the most experienced Internet marketers I have met, and just a good person.

His presentation at the Marketing Sherpa 2014 summit focused on the mindset of buyers and subscribers, as well as the analysis of marketers' actions, revealing their main mistakes. What should you do to be told "yes"?

A marketer is always a philosopher.

And also a psychologist. And then everything else.

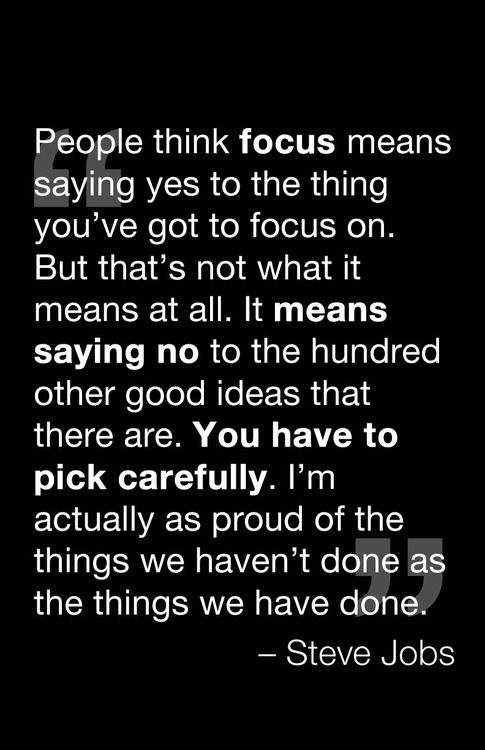

We must clearly understand the cause, and not just get the result. Ask yourself “why?” and not just “how?”. Not only to react, but also to reflect, to realize the true nature of the event.

In the face of constant market volatility, competition, pressure from management and other environmental factors, you rush to get ahead of events without having a holistic picture, without analyzing the causes. "By stopping, you can go faster." Slow down and evaluate if you are moving in the right direction - that's what you need now.

Marketer is egocentric.

But he puts the focus not on his personal ego, not the ego of the company, but on the ego of his client, each client. The client that we create ourselves.

The image of the ideal client is always in front of your eyes. If you know exactly what he should be, you will be able to educate him, influence his consciousness, development.

Buyer reality and values are the main ingredients of marketing. His ideas and expectations. Give the client clarity, maximum transparency - and his expectations will be justified. Crystal clear product presentation is what you need. Create such a product before creating a campaign image. Focus not only on technology, but also on product culture. Create a cult.

Marketing specialist

But not only data, statistics, trends.

The marketer is guided by wisdom. Adequate assessment of their actions. Thinking that leads to smart decision making.

The Internet is a global user behavior research laboratory. Enjoy!

Enjoy!

Analyze and ask why. "Why is that so?"

Questions will lead you to wisdom.

Marketer - optimizer.

But it’s not campaigns, pages, buttons, blocks that need to be optimized…

Optimize your train of thought.

Customers are not just objects, they are people. Put yourself in their place. Enter into a dialogue.

Become their guide: you know the route. This is the only way to influence the train of thought by optimizing it.

Every customer has his own decision-making algorithm in his mind. Every solid, big “yes” is made up of a sequence of small “yes”.

Every communication you make, every customer's attention to your product or promotion, answers tiny subconscious questions, tiny yes's or tiny no's.

You need to earn every little yes. To keep the pyramid from collapsing.

It is a lot of work to build a solid yes tower that will become the fortress of your product.

Think like your customer thinks. Offer him something that really has value. Do it in a way that none of your competitors will. Your ideal customer should clearly know why you are. Be responsible for every step and every offer. Consider every micro-action. After all, it can lead you to macro success.

Offer him something that really has value. Do it in a way that none of your competitors will. Your ideal customer should clearly know why you are. Be responsible for every step and every offer. Consider every micro-action. After all, it can lead you to macro success.

People who often say "yes" interesting statistics - BigData on vc.ru

Statistics related to this topic.

83 views

Several studies show that people who often say "yes" may have different characteristics and habits that affect their lives and relationships with others. Let's look at some statistics related to this topic.

1. Frequent consent to requests

A study by the University of California found that people who frequently agree to requests from others are more likely to be scammed. This is because they may be more likely to trust and believe other people, which can lead to them being deceived more easily.

2. Frequent overtime work

Frequent overtime work

A Gallup study found that people who tend to work overtime frequently are more likely to be burned out and have lower job satisfaction. This may be due to the fact that they do not find a balance between work and personal life, which can lead to a lack of time and energy for personal interests and relationships.

3. Frequent consent to social events

Research by Michigan State University found that people who frequently agree to participate in social events are more likely to be happy and have better relationships with others. This may be because participating in social activities can help them expand their social circle, learn new skills and interests, and gain support and inspiration from other people.

4. Frequent acceptance of new tasks and challenges

A Yale University study found that people who frequently agree to new tasks and challenges are more likely to succeed in life. This may be because they are more open to new opportunities and willing to take risks in order to achieve their goals.

By accepting new challenges, people can also expand their horizons and acquire new skills, which can also contribute to their success. In addition, frequent commitment to new tasks can improve a person's reputation in the eyes of colleagues and superiors, as it indicates their readiness for work and diligence.

In addition, people who say yes often can have better relationships in their professional and personal lives. They can be the best team players as they tend to be cooperative and supportive of their colleagues. They may also have more exciting and varied lives as they are ready to take on new challenges and opportunities.

5. Another study by the University of Minnesota found that people who say yes often feel more satisfied with their lives than those who turn down new opportunities. This is due to the fact that such people are often in new, interesting situations that can lead to new acquaintances, improved skills and opportunities for personal growth.

6. Also, a Columbia University study found that people who tend to say "yes" are more successful in their personal and professional lives. They often take on more responsibility and risk, which can ultimately lead to greater opportunity and success.

7. Another study by researchers at the London School of Economics also found a link between how often people say "yes" and their levels of happiness and well-being. Researchers polled 50,000 people from 143 countries and found that those who say yes often and take a more active approach to life are more likely to experience life satisfaction and have higher levels of happiness.

However, too much agreement on everything that is offered can have negative consequences. People can become overworked, not being able to complete all tasks on time, which can negatively impact their performance and quality of work. Also, constantly agreeing to everything can cause people to lose a sense of control over their lives and time, which can lead to stress and anxiety.