Parenting high functioning autism

7 Tips for Parenting a Child with 'High Functioning' Autism

Your autistic child might be the family computer expert. They may be the one you ask when you can’t remember which day your neighbor came to visit, or what time the hailstorm started. When it comes to their focused interest, it might seem like they have more information in their head than exists on the entire internet.

They might also object to unexpected routine changes or rules they don’t agree with. Their school grades might fluctuate wildly between the subjects they enjoy and the ones they loathe. You might spend many hours trying to entice their attention away from an issue that bothers them.

As intelligent and talented as your autistic child might be, they likely need support in certain areas. Examples include:

- socializing

- communication

- emotional regulation

- anxiety management

- adapting to change

- sensory regulation

That said, there are ways you can help.

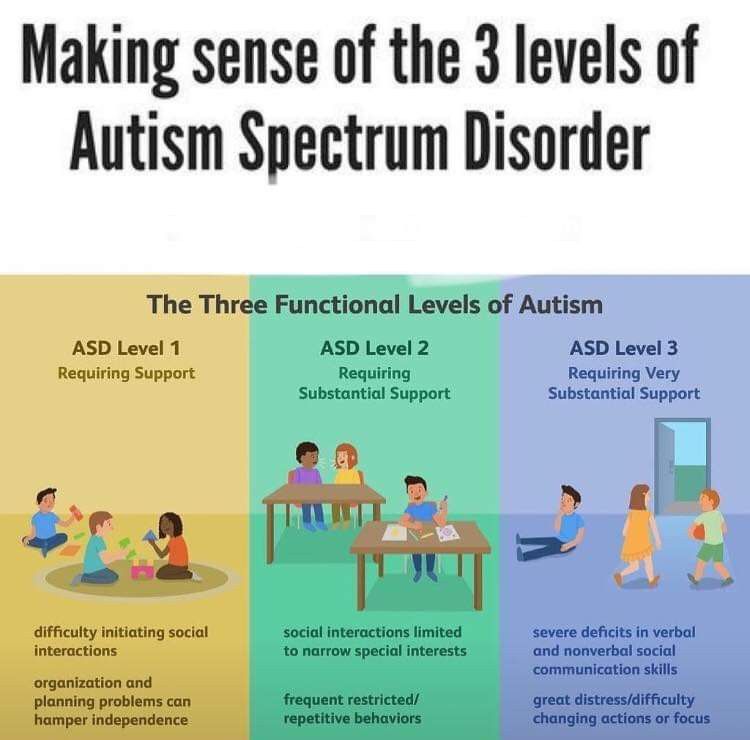

Autism is a spectrum, which means it affects everyone differently. Each child has their own strengths and areas of development. There are various parenting strategies you can try, depending on your child’s support needs.

1. Build rapport.

Rapport is affinity. It’s familiarity and trust that includes two-way interaction, like communication or a change in behavior in response to another person’s presence.

When an educator or therapist works with a child, the first step is building rapport.

Increasing rapport with your child involves finding ways to share in their experiences, such as:

- active listening: Active listening involves giving your child your undivided attention and noticing as much as you can about what they’re trying to communicate. You can gain useful insight by listening to behaviors as well as words.

- child-led activities: Participating in activities that your child chooses sends a message that their interests matter and is a powerful rapport-building strategy.

Rapport means your child will be more willing to communicate with you, which makes supporting them easier.

2. Increase social awareness.

Theory of mind (ToM) is the skill that allows people to understand the different perspectives of others. ToM differences are common in autism.

If your child experiences ToM differences, this doesn’t mean they can’t learn what other people think or feel. However, if they don’t passively acquire this insight at the same rate as allistic (non-autistic) kids, they might need explanations about other people’s behavior.

Spending time talking about social encounters can increase ToM skills. Asking your child how they felt or what they thought about interactions with their peers can create teachable moments where you explain behaviors that they may have misunderstood.

3. Examine communication.

It’s ironic that autistic kids with advanced vocabularies would benefit from support with communication. However, there are a few areas in which your child might benefit from coaching, such as:

- pragmatic language.

This is social communication, including taking turns while speaking and listening appropriately while the other person is talking.

This is social communication, including taking turns while speaking and listening appropriately while the other person is talking. - expressive language. Outgoing communication, both written and spoken, is expressive language. Nonverbal communications, like gestures, are part of expressive language.

- receptive language. Incoming communication, including reading and listening, is part of receptive language. It can be useful to check for comprehension by asking your child to repeat the things you’ve told them.

Effective communication impacts how your child interacts with the allistic world, so it’s a skill worth taking the time to improve.

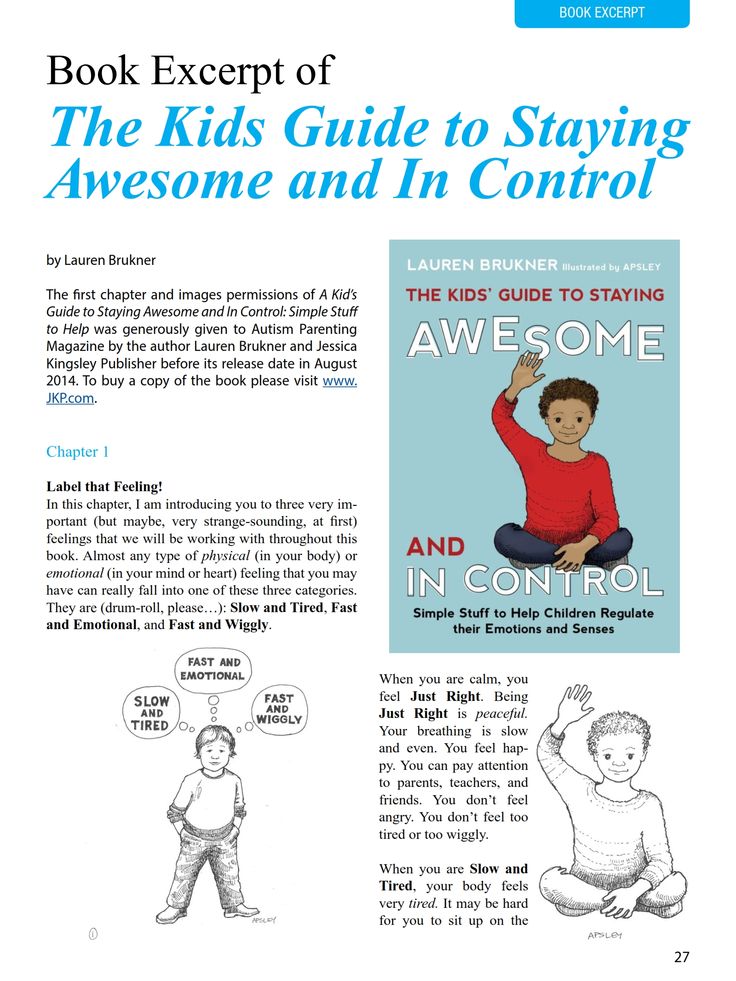

4. Teach calming strategies.

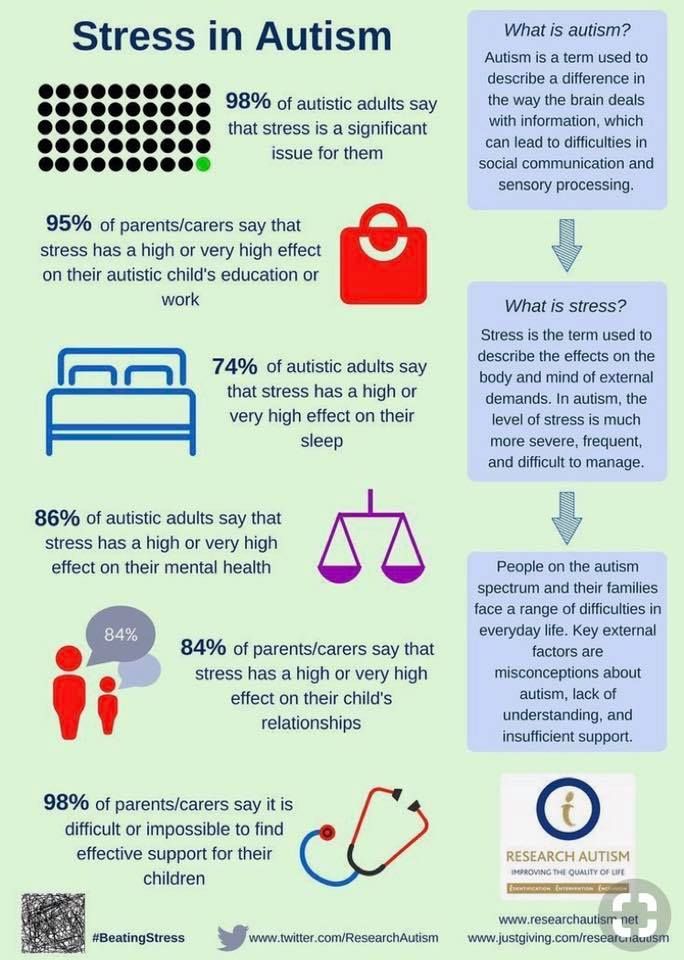

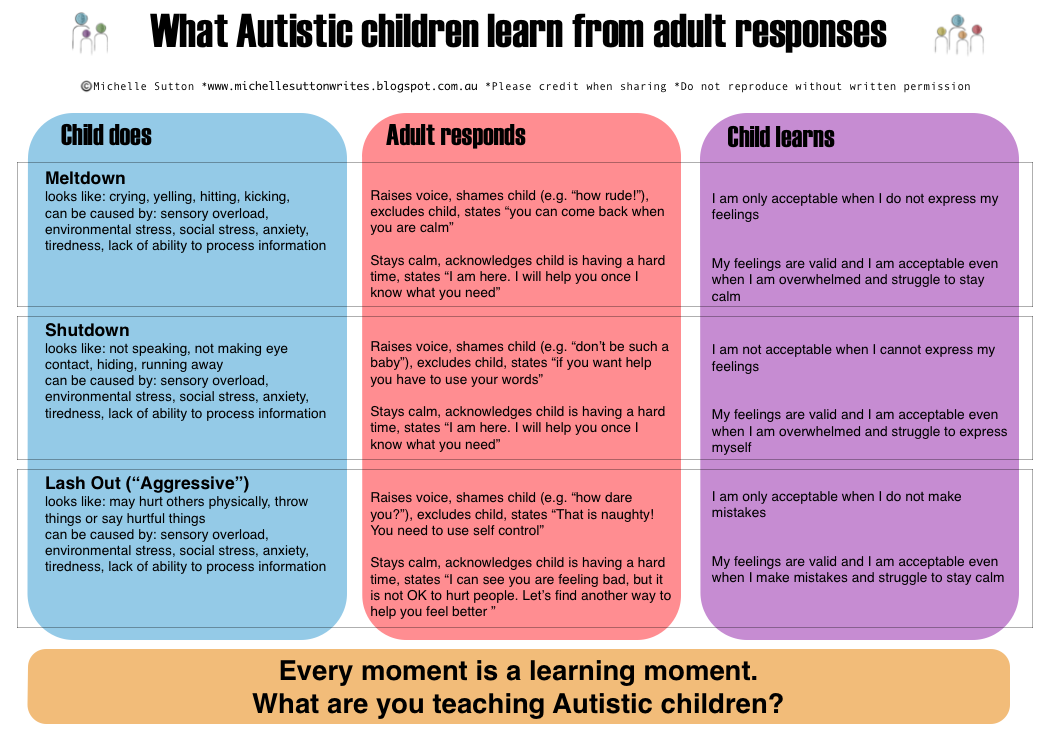

Emotional dysregulation isn’t just a cause of disruptive outbursts. Research, including a 2020 study, also links it to anxiety in autistic people.

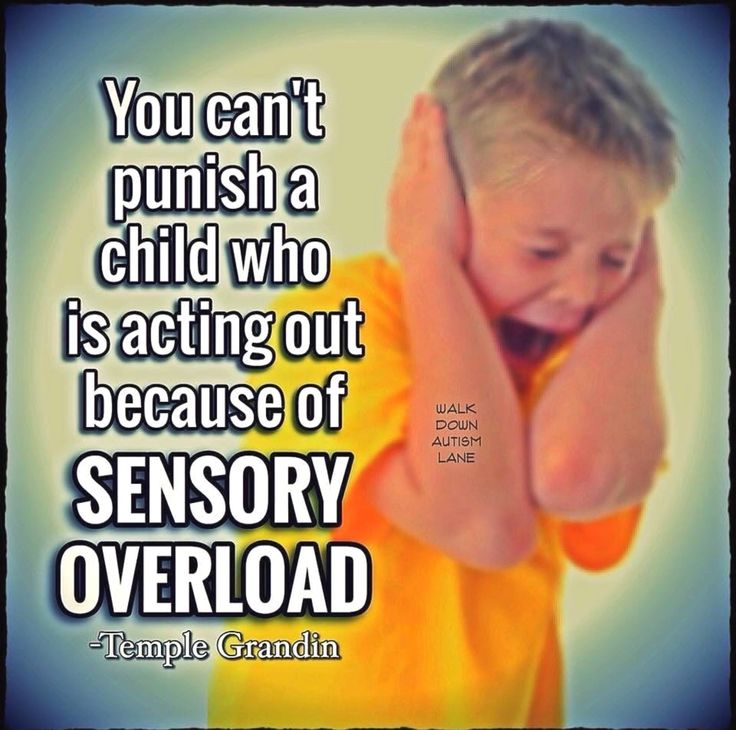

It’s important to remember that emotional outbursts are not a form of manipulation. Instead, your child is feeling overwhelmed and has temporarily lost their ability to regulate emotion.

Observing and identifying triggers or warning signs enables you to intervene before your child gets too upset. When you see signs of an impending outburst, redirecting with a calming activity can help:

- “You look like you’re getting frustrated. Do you need to ask for a break?”

- “I can see you’re clenching your fists. Do you want to try a breathing exercise?”

Choices can also help your child feel more in control, such as: “You look like you need a break. Do you want to go for a walk, or have something to eat?”

Research from 2017 suggests that wearable technology like smartwatches can also be effective emotional regulation tools. The watches monitor the wearer’s internal cues like heart rate and respond with a calming intervention, such as soothing imagery or music.

5. Foster flexibility.

You may have discovered that prompting your child before an activity change makes the transition easier. This is because an unpredicted change can be anxiety-provoking for autistic people.

It’s usually easy to manage transitions at home because it’s a controlled environment. You can prompt your child with a 5- or 10-minute warning, and check in several times during that time frame. However, the outside world is not as accommodating.

One solution is to gradually fade transition prompts. Try a shorter notice with fewer check-ins to see how your child can handle it.

Another solution is to create a positive association with an unexpected change. Offer something in return for an unprompted transition, like extra iPad time later for turning off the TV now.

6. Increase autism awareness.

Increasing your child’s autism awareness begins with discussing their diagnosis.

They may have already felt different from their typically developing peers, so hearing the news that they’re autistic likely makes sense. Maybe they were diagnosed later in childhood or early in their teen years, so they knew about autism even before their own diagnosis.

Regardless of their path to diagnosis, it’s important to focus on the positive aspects of autism, such as special isolated skills (SIS). A 2014 study examining SISs in autism found repeat occurrences in several areas:

A 2014 study examining SISs in autism found repeat occurrences in several areas:

- memory

- reading

- visuospatial

- drawing

- computation

- music

Even if your child doesn’t have an SIS, there are other autistic strengths. For example, the preference for structure makes autistic people comfortable following rules.

Along with the emphasis on strengths comes the understanding that most people, autistic or otherwise, have areas where they can benefit from help. As your child learns more about autism, they’ll likely have questions that may inspire interesting and rapport-building conversations.

7. Network with other parents.

Sometimes the best advice comes from those who’ve been in your shoes. Networking with other parents in the autistic community can connect you to support and understanding that can make your role easier.

Your child’s pediatrician may have contact information for parent support groups in your area, or you can try searching online.

These autism organizations and resources may offer support and social connection:

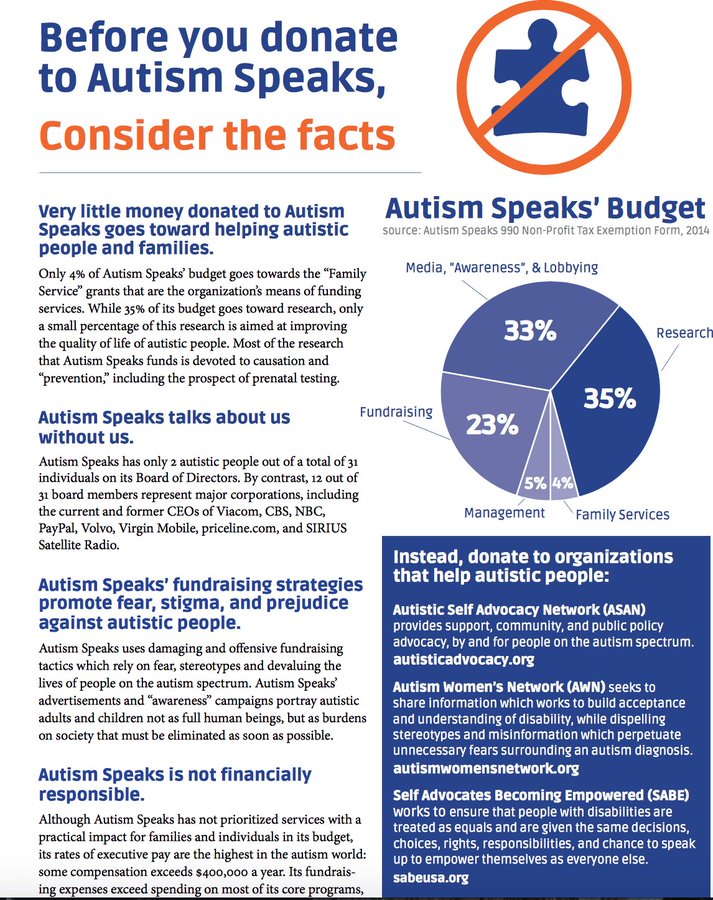

- Autism Society of America

- Autistic Self Advocacy Network

- Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network

- Autism Research Institute

- Self Advocates Becoming Empowered

- Sesame Street and Autism

- Wrong Planet

Autism is a neurodevelopmental difference that involves both strengths and areas of development.

Parents can help their autistic kids thrive and reach their potential with a few simple strategies, like strengthening rapport, and increasing social and communication abilities.

It can help to meet other parents of autistic kids, to learn and exchange ideas. It’s helpful to network with people who share your experience.

Parenting Tips & Treatment Techniques

"We have recently learned that our daughter has (or might have) High-Functioning Autism, and we're wondering about what comes next. We were not prepared to hear that she is anything other than happy and healthy, and this diagnosis is particularly worrisome."

We were not prepared to hear that she is anything other than happy and healthy, and this diagnosis is particularly worrisome."

You may be unsure about how to best help your youngster or confused by conflicting treatment advice. Also, you may have been told that High-Functioning Autism (HFA) is an incurable, lifelong condition, leaving you concerned that nothing you do will make a difference.

While it is true that HFA is not something a child simply "grows out of," there are many treatments that can help kids learn new skills and overcome a wide variety of developmental challenges. From free government services to in-home behavioral therapy and school-based programs, assistance is available to meet your youngster's special needs. With the right treatment plan, and a lot of love and support, your youngster can learn, grow, and thrive.

Here is a comprehensive list of things to consider:

1. Accept your youngster, quirks and all. Rather than focusing on how your HFA youngster is different from other kids and what he or she is “missing,” practice acceptance. Enjoy your kid’s special quirks, celebrate small successes, and stop comparing your youngster to others. Feeling unconditionally loved and accepted will help your youngster more than anything else.

Enjoy your kid’s special quirks, celebrate small successes, and stop comparing your youngster to others. Feeling unconditionally loved and accepted will help your youngster more than anything else.

2. Be consistent. Kids with High-Functioning Autism have a hard time adapting what they’ve learned in one setting (e.g., a therapist’s office or school) to other settings, including the home. Creating consistency in your youngster’s environment is the best way to reinforce learning. Find out what your youngster’s therapists are doing and continue their techniques at home. Explore the possibility of having therapy take place in more than one place in order to encourage your youngster to transfer what he or she has learned from one environment to another. It’s also important to be consistent in the way you interact with your youngster and deal with challenging behaviors.

==> How To Prevent Meltdowns and Tantrums In Children With High-Functioning Autism and Asperger's

3. Become an expert on your youngster. Figure out what triggers your kid’s “bad” or disruptive behaviors and what elicits a positive response. What does your HFA youngster find stressful? Calming? Uncomfortable? Enjoyable? If you understand what affects your youngster, you’ll be better at troubleshooting problems and preventing situations that cause difficulties.

Become an expert on your youngster. Figure out what triggers your kid’s “bad” or disruptive behaviors and what elicits a positive response. What does your HFA youngster find stressful? Calming? Uncomfortable? Enjoyable? If you understand what affects your youngster, you’ll be better at troubleshooting problems and preventing situations that cause difficulties.

4. Caring for a youngster with High-Functioning Autism can demand a lot of energy and time. There may be days when you feel overwhelmed, stressed, or discouraged. Parenting isn’t ever easy, and raising a youngster with HFA is even more challenging. It’s essential that you take care of yourself in order to be the best mother or father you can be. Don’t try to do everything on your own. You don’t have to! There are many places that families of HFA children can turn to for advice, a helping hand, advocacy, and support.

5. Create a home safety zone. Carve out a private space in your home where your youngster can relax, feel secure, and be safe. This will involve organizing and setting boundaries in ways he can understand. Visual cues can be helpful (e.g., colored tape marking areas that are off limits, labeling items in the house with pictures). You may also need to safety proof the house, particularly if he is prone to tantrums or other self-injurious behaviors.

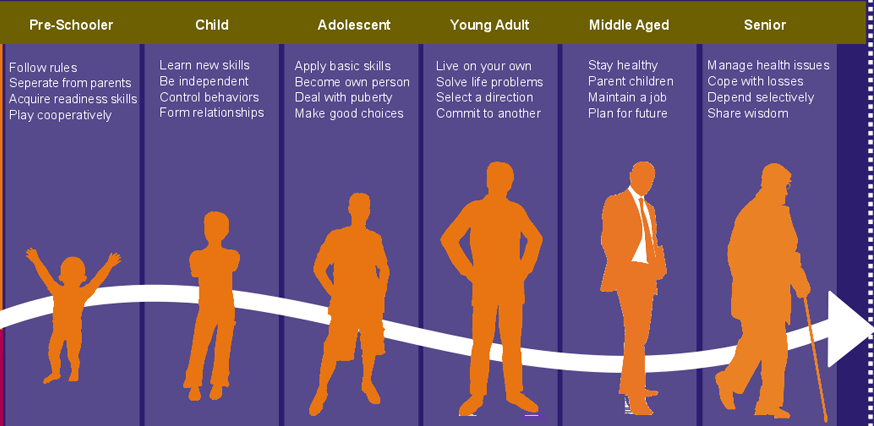

6. Don’t give up. It’s impossible to predict the course of High-Functioning Autism. Don’t jump to conclusions about what life is going to be like for your youngster. Like everyone else, people with High-Functioning Autism have an entire lifetime to grow and develop their abilities.

7. Don’t wait for a diagnosis. As the mother or father of a youngster with High-Functioning Autism or Asperger’s Syndrome, the best thing you can do is to start treatment right away. Seek help as soon as you suspect something’s wrong. Don't wait to see if your youngster will catch up later or outgrow the problem. Don't even wait for an official diagnosis. The earlier kids with HFA get help, the greater their chance of treatment success. Early intervention is the most effective way to speed up your youngster's development and reduce the symptoms of HFA.

Seek help as soon as you suspect something’s wrong. Don't wait to see if your youngster will catch up later or outgrow the problem. Don't even wait for an official diagnosis. The earlier kids with HFA get help, the greater their chance of treatment success. Early intervention is the most effective way to speed up your youngster's development and reduce the symptoms of HFA.

8. Every mother or father needs a break now and again. And for moms and dads coping with the added stress of High-Functioning Autism, this is especially true. In respite care, another caregiver takes over temporarily, giving you a break for a few hours, days, or even weeks.

9. Figure out the need behind the temper tantrum. It’s only natural to feel upset when you are misunderstood or ignored, and it’s no different for kids with High-Functioning Autism. When kids with High-Functioning Autism act out, it’s often because you’re not picking up on their nonverbal cues. Throwing a tantrum is their way communicating their frustration and getting your attention.

==> Parenting System that Significantly Reduces Defiant Behavior in Teens with Aspergers and High-Functioning Autism

10. If stress, anxiety, or depression is getting to you, you may want to see a therapist of your own. Therapy is a safe place where you can talk honestly about everything you’re feeling—the good, the bad, and the ugly. Marriage or family therapy can also help you work out problems that the challenges of life with an HFA youngster are causing in your spousal relationship or with other family members.

11. HFA infants and toddlers through the age of two can receive assistance through the Early Intervention program. In order to qualify, your youngster must first undergo a free evaluation. If the assessment reveals a developmental problem, you will work with early intervention treatment providers to develop an Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP). An IFSP describes your youngster’s needs and the specific services he or she will receive. For High-Functioning Autism, an IFSP would include a variety of behavior, physical, speech, and play therapies. It would focus on preparing HFA children for the eventual transition to school. Early intervention services are typically conducted in the home or at a childcare center. To locate local early intervention services for your youngster, ask your doctor for a referral.

For High-Functioning Autism, an IFSP would include a variety of behavior, physical, speech, and play therapies. It would focus on preparing HFA children for the eventual transition to school. Early intervention services are typically conducted in the home or at a childcare center. To locate local early intervention services for your youngster, ask your doctor for a referral.

12. Joining a support group is a great way to meet other families dealing with the same challenges you are. Moms and dads can share information, get advice, and lean on each other for emotional support. Just being around others in the same boat and sharing their experience can go a long way toward reducing the isolation many moms and dads feel after receiving the youngster’s diagnosis.

13. Keep in mind that no matter what treatment plan is chosen, your involvement is vital to success. You can help your youngster get the most out of treatment by working hand-in-hand with the treatment team and following through with the therapy at home.

14. HFA kids over the age of three may receive assistance through school-based programs. As with early intervention, special education services are tailored to your youngster’s individual needs. Kids with HFA are often placed with other developmentally-delayed children in small groups where they can receive more individual attention and specialized instruction. However, depending on their abilities, they may also spend at least part of the school day in a regular classroom. The goal is to place children in the least restrictive environment possible where they are still able to learn. If you’d like to pursue special education services, your local school system will first need to evaluate your youngster. Based on this assessment, an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) will be created. An IEP outlines the educational goals for your youngster for the school year. Additionally, it describes the special services or aids the school will provide your youngster in order to meet those goals.

==> Parenting Children and Teens with High-Functioning Autism: Comprehensive Handbook

15. Learn about High-Functioning Autism. The more you know about HFA, the better equipped you’ll be to make informed decisions for your youngster. Educate yourself about the treatment options, ask questions, and participate in all treatment decisions.

16. Look for nonverbal cues. If you are observant and aware, you can learn to pick up on the nonverbal cues that kids with High-Functioning Autism use to communicate. Pay attention to the kinds of sounds they make, their facial expressions, and the gestures they use when they’re tired, hungry, or want something.

17. Make time for fun. A youngster coping with High-Functioning Autism is still a kid. For kids and their moms and dads, there needs to be more to life than therapy. Schedule playtime when your youngster is most alert and awake. Figure out ways to have fun together by thinking about the things that make her smile, laugh, and come out of her shell. Your youngster is likely to enjoy these activities most if they don’t seem therapeutic or educational. There are tremendous benefits that result from your enjoyment of your youngster’s company and from her enjoyment of spending un-pressured time with you. Play is an essential part of learning and shouldn’t feel like work.

Your youngster is likely to enjoy these activities most if they don’t seem therapeutic or educational. There are tremendous benefits that result from your enjoyment of your youngster’s company and from her enjoyment of spending un-pressured time with you. Play is an essential part of learning and shouldn’t feel like work.

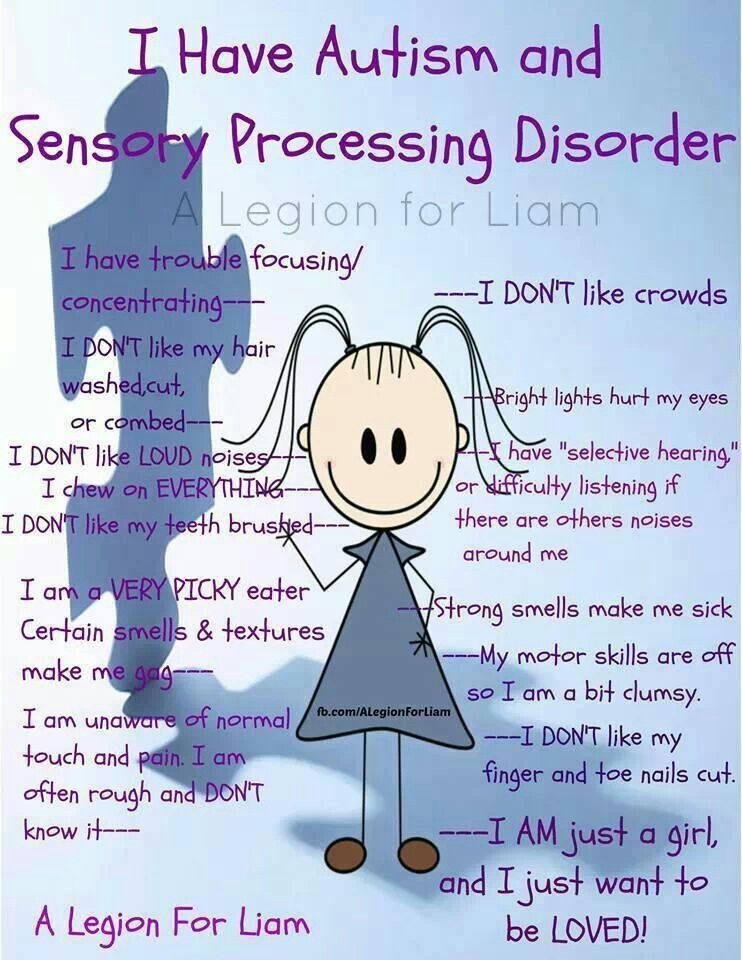

18. Pay attention to your youngster’s sensory sensitivities. Many kids with High-Functioning Autism are hypersensitive to light, sound, touch, taste, and smell. Other kids are “under-sensitive” to sensory stimuli. Figure out what sights, sounds, smells, movements, and tactile sensations trigger your kid’s “bad” or disruptive behaviors and what elicits a positive response. What does your HFA youngster find stressful? Calming? Uncomfortable? Enjoyable? If you understand what affects your youngster, you’ll be better at trouble-shooting problems, preventing situations that cause difficulties, and creating successful experiences.

==> Teaching Social Skills and Emotion Management to Children and Teens with Asperger's and High-Functioning Autism

19. Reward good behavior. Positive reinforcement can go a long way with kids with High-Functioning Autism, so make an effort to “catch them doing something good.” Praise them when they act appropriately or learn a new skill, being very specific about what behavior they’re being praised for. Also look for other ways to reward them for good behavior (e.g., giving them a sticker, letting them play with a favorite toy, etc.).

Reward good behavior. Positive reinforcement can go a long way with kids with High-Functioning Autism, so make an effort to “catch them doing something good.” Praise them when they act appropriately or learn a new skill, being very specific about what behavior they’re being praised for. Also look for other ways to reward them for good behavior (e.g., giving them a sticker, letting them play with a favorite toy, etc.).

20. Stick to a schedule. Kids with High-Functioning Autism tend to do best when they have a highly-structured schedule or routine. This goes back to the consistency they both need and crave. Set up a schedule for your youngster, with regular times for meals, therapy, school, and bedtime. Try to keep disruptions to this routine to a minimum. If there is an unavoidable schedule change, prepare him for it in advance.

21. Under the U.S. federal law known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), kids with disabilities—including those with HFA—are eligible for a range of free or low-cost services. Under this provision, kids in need and their families may receive:

- assisted technology devices

- medical evaluations

- parent counseling and training

- physical therapy

- psychological services

- speech therapy

- other specialized services

Kids under the age of 10 do not need a diagnosis to receive free services under IDEA. If they are experiencing a developmental delay, including delays in communication or social development, they are automatically eligible for early intervention and special education services.

22. With so many different treatments available, it can be tough to figure out which approach is right for your youngster. Making things even more complicated, you may hear different or even conflicting recommendations from other moms and dads – and even doctors. When putting together a treatment plan for your youngster, keep in mind that there is no single treatment that will work for everyone. Each child with High-Functioning Autism is unique, with different strengths and weaknesses.

When putting together a treatment plan for your youngster, keep in mind that there is no single treatment that will work for everyone. Each child with High-Functioning Autism is unique, with different strengths and weaknesses.

23. Your youngster’s treatment should be tailored according to his or her individual needs. You know your youngster best, so it’s up to you to make sure those needs are being met. You can do that by asking yourself the following questions:

- How does my youngster learn best (e.g., through seeing, listening, or doing)?

- What are my youngster’s strengths?

- What are my youngster’s weaknesses?

- What behaviors are causing the most problems?

- What does my youngster enjoy and how can those activities be used in treatment?

- What important skills is my youngster lacking?

24. Know that a good treatment plan will:

- Actively engage your youngster's attention in highly structured activities

- Build on your youngster's interests

- Offer a predictable schedule

- Provide regular reinforcement of behavior

- Involve the moms and dads

- Teach tasks as a series of simple steps

25. Know your youngster’s rights. As the mother or father of an HFA youngster, you have a legal right to:

Know your youngster’s rights. As the mother or father of an HFA youngster, you have a legal right to:

- Seek an outside evaluation for your youngster

- Request an IEP meeting at any time if you feel your youngster’s needs are not being met

- Invite anyone you want—from a relative to your youngster’s doctor—to be on the IEP team

- Free or low-cost legal representation if you can’t come to an agreement with the school

- Disagree with the school system’s recommendations

- Be involved in developing your youngster’s IEP from start to finish

More resources for parents of children and teens with High-Functioning Autism and Asperger's:

==> Launching Adult Children with Asperger's and High-Functioning Autism: Guide for Parents Who Want to Promote Self-Reliance

==> Unraveling The Mystery Behind Asperger's and High-Functioning Autism: Audio Book

==> Highly Effective Research-Based Parenting Strategies for Children with Asperger's and High-Functioning Autism

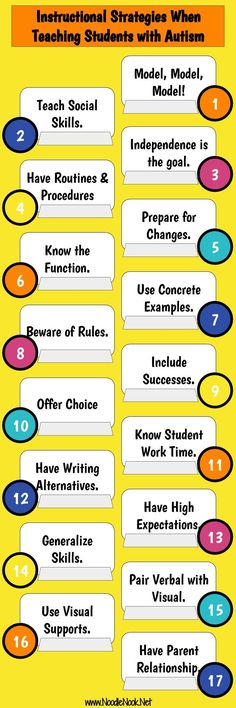

How to teach a student with high-functioning autism?

02. 10.14

10.14

Tips for teachers of children with high -functional autism or asperger syndrome

Author: Susan J. Susan J. Moreno

Source: Oasis Maap

9000 9000 9000

Regardless of the level intelligence and/or age, people with autism have problems with self-organization skills. Even an "A" student with a photographic memory with autism may constantly forget to get a pencil for work or turn in an assignment to a teacher. In such cases, students need help, which should be provided in the least restrictive way. For example, you can stick a photo of a pencil on the cover of a workbook that needs it, or the teacher can remind you at the end of the day what tasks you need to do at home.

It is important to always praise a student if he has done something that he previously forgot. If he did not succeed, then never scold or “snarl” at him. No notation on this topic will NOT help, most likely, the problem will only get worse. You will only convince the child that he will never be able to cope with this task.

You will only convince the child that he will never be able to cope with this task.

Such a student's desk is the neatest or most cluttered desk in the whole school. The child with the neatest desk is likely to have a strong craving for uniformity and get upset if anything gets in the way of the order he has created. The owner of the most cluttered desk needs your regular tidying tips so that he can find everything he needs. Remember that, most likely, a mess is not his choice, he simply does not cope with such a task of organizing, and he needs separate training in such a skill. Teach him the skills of self-organization by suggesting small and concrete steps.

1. People with autism have difficulty with abstract and conceptual thinking. Some of them may acquire some abstract skills over time, but others never will. Avoid abstract ideas whenever possible. When abstract concepts need to be explained, use visuals, gestures, or written text to make it easier for the student to understand the abstract idea.

2. An increase in unusual or problematic behavior may indicate an increase in stress levels. Sometimes the cause of such stress is a feeling of loss of control over what is happening. In such situations, it is helpful to have a "safe place" or "safe person" that the student can turn to if they need to leave an overly stressful situation. If this happens, then a program should be developed to help the student gradually get used to and/or stay in the stressful situation next time.

3. Don't take problem behavior personally. A child with high functioning autism is not a cunning manipulator who wants to make life difficult for you. As a general rule, any problematic behavior is just an unfortunate way to survive in an overly confusing, confusing, and frightening world. People with autism, by definition, can only look at situations from their own perspective and may find it difficult to assess or predict other people's reactions. This makes them incapable of manipulation.

4. Most people with autism use and perceive language only literally. Until you get to know the ability of a particular student better, avoid the following speech constructions:

Most people with autism use and perceive language only literally. Until you get to know the ability of a particular student better, avoid the following speech constructions:

- Idiom (“mouth shut”, “fly off the coils”, “like snow on your head”, and so on).

- Double meanings (most jokes have double meanings).

- Sarcasm, for example, when you say "Well done!" a student who spilled a bottle of ketchup.

- Nickname.

- Diminutives, for example, friend, friend, and so on.

5. When talking to such students, try to be as specific as possible. Remember that your facial expressions and other social cues may not make any sense to him. Avoid general questions like, "Why are you acting like this?" Instead, say, “I didn't like that you slammed your textbook on the desk so loudly when I said it was time to go to PE. Please quietly put your textbook on the table and get ready for PE."

6. If the student seems to be failing on a task, explain the task as a sequence of small steps, or present it in a different form (using a visual, verbal, or physical model).

7. Try not to make your student speech overload. Speak clearly and to the point. Use the shortest sentences if you feel that the student does not understand you. Even if he does not have hearing problems and he listens carefully, he may have problems understanding the meaning of what was said and isolating important information.

8. Always prepare the student in advance for changes in routine and/or environment, including meetings, teacher changes, schedule changes, and so on. Use a visual or written schedule to prepare for change.

9. Behavioral methods work, but if used incorrectly, they lead to robotic behavior, only short-term improvements or an increase in aggressive behavior. If you are using behavioral procedures, they must be based on positive reinforcement only and be appropriate for the child's chronological age.

10. Consistency in your expectations and behavior with a student is the key to success.

11. Be aware that a normal level of auditory or visual information may be perceived by the student as too much or too little. For example, the buzzing of a fluorescent light can completely capture the attention of some people with autism. Consider whether you can change the classroom environment to reduce "visual noise" or seat the student in a way that does not distract or upset them.

For example, the buzzing of a fluorescent light can completely capture the attention of some people with autism. Consider whether you can change the classroom environment to reduce "visual noise" or seat the student in a way that does not distract or upset them.

12. If a student with high functioning autism is arguing with you by repeating the same phrase and/or repeating the same questions, ask them to write down the question or objection. Then write your answer. If you continue to respond in writing, then, as a rule, a person with autism calms down and stops repetitive speech. If that doesn't work, then ask him to write down the recurring question or argument, and then ask him to write down the most logical answer or the words he thinks you need to say. This will distract him from the escalation of the verbal question or objection, and it may become a socially acceptable way for him to express his displeasure or dismay.

13. If a student cannot read or write, try role playing where you ask him a repeated question and he answers you. If every time you try to logically answer or argue with him, then this is unlikely to stop the behavior. Very often it is not the subject of the question or objection that upsets the student at all. Rather, he is trying to convey to you a sense of loss of control or insecurity about someone or something in the environment.

If every time you try to logically answer or argue with him, then this is unlikely to stop the behavior. Very often it is not the subject of the question or objection that upsets the student at all. Rather, he is trying to convey to you a sense of loss of control or insecurity about someone or something in the environment.

14. It can be difficult for students with autism to "get into" your arguments. If repeated objections or questions continue, consider the possibility that he is very excited about the topic, but he does not know how to reformulate the question so that it more accurately reflects the essence of the matter.

15. Since there can be various communication problems with autism, do not expect a student with autism to correctly convey important messages to their parents about school activities, assignments, rules, and so on. Pass something through the student to the parents only for experimental purposes with a control check, or if you are absolutely sure that he has this skill. Sometimes even parental notes don't work, as the student may forget to give them or lose them before he gets home. Until this skill is perfected, it is best to rely on phone calls to parents. In general, frequent and transparent communication between the teacher and parents (or other family members involved in the upbringing of the child) is extremely important when teaching these children.

Sometimes even parental notes don't work, as the student may forget to give them or lose them before he gets home. Until this skill is perfected, it is best to rely on phone calls to parents. In general, frequent and transparent communication between the teacher and parents (or other family members involved in the upbringing of the child) is extremely important when teaching these children.

16. If your class needs to pair up or choose partners to work with, assign the children to a score or some random attribute. Or ask a particularly kind student to choose a child with autism as a mate. This will need to be agreed before the lesson. Otherwise, a student with autism may be permanently single. And this is a great pity, since it is these students who can benefit the most from working with another child.

We hope that the information on our website will be useful or interesting for you. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

Friendly environment, Education and training

Autism through the eyes of a sister. A girl's view of her brother's autism - Autism and developmental disorders

Autism through the eyes of a sister.

A girl's view of her brother's autism.

Book for children about high -functional autism

and similar developmental disorders [1]

Introduction

Autisms about autism are gradually becoming increasingly more and more clearly, as the number autism spectrum. What we want to focus on in this book is siblings - children who are connected in their daily lives with a brother or sister with high-functioning autism or Asperger's syndrome. We hope that parents and children will read this book together. This book also aims to provide siblings with more accurate information specifically about high functioning autism and related disorders. Second, we aim to share experiences and discuss feelings that siblings experience, such as feelings of anger, confusion, anxiety, responsibility, care, and pride. At the end of the book, questions are proposed, the discussion of which together with the child will help parents and children start a conversation on exciting topics.

At the end of the book, questions are proposed, the discussion of which together with the child will help parents and children start a conversation on exciting topics.

As more and more children with high functioning autism or Asperger's Syndrome are enrolled in integrated classrooms in schools, there is a need for materials to inform classmates and peers. If healthy children are aware of what autism is, it will be easier for them to cope with their feelings, and they will begin to better understand their role as a classmate and friend of such a child. The material in this book can be used by teachers, therapists, and other professionals.

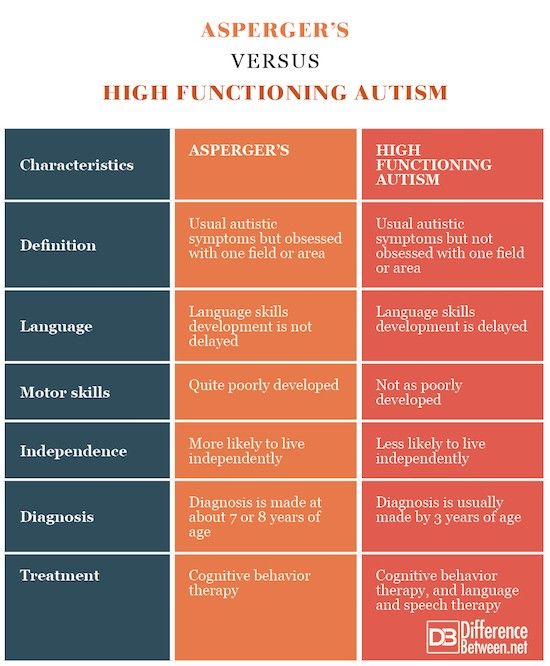

This book is very personal. Although written by Eve Bend, PhD, a clinical psychologist, it conveys the thoughts, feelings, and experiences of Emily Hecht, a 9-year-old girl with a brother with high-functioning autism. Based on numerous conversations with Emily, her parents and her brother Daniel, the book conveys Emily's vision of her brother's autism. Information about autism as a disease is presented by Dr. Bend in a form accessible to children's understanding. There are no particular differences between high-functioning autism and Asperger's syndrome, although there is constant talk among specialists about whether Asperger's syndrome is a form of high-functioning autism or is it a separate disorder.

Information about autism as a disease is presented by Dr. Bend in a form accessible to children's understanding. There are no particular differences between high-functioning autism and Asperger's syndrome, although there is constant talk among specialists about whether Asperger's syndrome is a form of high-functioning autism or is it a separate disorder.

In this book, we have chosen to talk about autism in its main manifestations in order to reflect, if possible, the entire spectrum of autistic disorders. The author hopes that this book will help many, and especially those who live or work with people with high-functioning autism or Asperger's Syndrome. In working on the book, we tried to talk not only about Daniel's difficulties, but also about positive moments, about his successes. We will consider that we have reached our goal if, after reading this book, you not only learn something new for yourself, but also change your idea about all this.

Author's Preface

I would like to thank so many people for their help in making this book possible. I am very grateful to my husband and children: Stephen, Anna and Rebecca for their patience and understanding. I am grateful to the Hecht family, David, Bes, Emily, and Daniel for their input and support, without which this book would not have been possible. Acquaintance with them was for me a real gift of fate.

I am very grateful to my husband and children: Stephen, Anna and Rebecca for their patience and understanding. I am grateful to the Hecht family, David, Bes, Emily, and Daniel for their input and support, without which this book would not have been possible. Acquaintance with them was for me a real gift of fate.

I also want to thank Wayne Gilpin and Paulie McGlue of Future Horizons for editing and publishing assistance and Sue Lynn for excellent illustrations. Dr. Gary Mesibov, Lynn Medley, Elaine Williams, Dr. Steven Bend and David Bend are the people who contributed a lot of their comments during the writing of this text. I am also very grateful for the support and help of Helen Gillett, Wendy Gelber, Katie Lopez and Lisa Bend.

And of course I want to remember the parents and children in whose families a child with autism or Asperger's syndrome is brought up, whom I managed to meet during my work. This book is dedicated to them, and I am grateful to them for the inspiration and understanding with which they treated my work.

Yves Bend

Family Foreword

We would like to thank many, many people for their inspiration and support. Participation in the writing of this book was not only pleasant for us, but also useful. It helped us to see ourselves as an ordinary family, with all the joys and difficulties that we face daily.

There were many wonderful teachers, professionals and doctors who helped us through this journey of life with Daniel. Constant support has always surrounded us in the form of friends and relatives, and this helped us find the strength to move forward in the implementation of this idea. This book is an opportunity for us to express our gratitude and thank these people.

We especially want to thank Dr. Yves Bend. She has provided our family with essential information, continued support and guidance throughout these years. Special thanks to Dr. Steven Bend for his patience with all of us during the long months that this book was written.

Bas, David, Daniel, and Emily Hecht

Foreword

The opportunity to work with students like Yves Bend is what really attracts me in my work. I've known Eve since she was first a graduate student and then a graduate student and clinical psychologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I always looked forward to our conversations, because Eve was distinguished by reasonableness, and she always had many interesting ideas. Remembering Eve in those years, I can say that she had a great creative potential, inspiration, a deep understanding of the problem and the talent of a writer. Since then, almost nothing has changed, although 10 years have passed, and in this book you can find the named qualities of Yves, which made the book interesting for the reader.

Creativity and the ability to find non-standard solutions to various situations helped Eve find her own way of communicating with the reader, which she used in this book. One of her clients, Emily Hecht, faced a whole host of problems with being a sibling child with autism. Eve began writing this book in the course of her meetings with Emily, and it has helped both of them to better articulate their thoughts about the issues that siblings are concerned about. While working with the girl, Eve had non-standard ideas that she, with the permission of Emily and her parents, was able to translate into this wonderful book.

One of her clients, Emily Hecht, faced a whole host of problems with being a sibling child with autism. Eve began writing this book in the course of her meetings with Emily, and it has helped both of them to better articulate their thoughts about the issues that siblings are concerned about. While working with the girl, Eve had non-standard ideas that she, with the permission of Emily and her parents, was able to translate into this wonderful book.

This book combines a natural and direct approach to the situation of a little nine-year-old girl with a professional view of a specialist. The result is an interesting combination.

Working with students like Yves is always a pleasure and honor, so it's a little sad to part with them when they go on a "free float" to achieve something in this world on their own. Sadness gradually disappears, because I continue to communicate with children and watch how they grow and develop. With Eve, this feeling of sadness has grown into a feeling of great pride and satisfaction for such a creation of hers as this book, and I understand that this is also my, albeit small, merit. It is very pleasant to realize that now many people will learn about Eve and her ideas, having read, I am sure, with pleasure, this book. 9-year-old sister Emily. They wanted me to help her better understand her brother and his disorder.

It is very pleasant to realize that now many people will learn about Eve and her ideas, having read, I am sure, with pleasure, this book. 9-year-old sister Emily. They wanted me to help her better understand her brother and his disorder.

When Emily first came to me, she brought with her a book about autism, written specifically for children, which gave an example of a child with classic autism and wrote about his family. We reviewed the book together and I asked her if what is described in this book is similar to her family with her brother Daniel. Emily shook her head. She found none of this to be personal, and I promised her that I would look for something we could read together that would be more like her life with her brother with Asperger's.

At my next consultation, I had to apologize to Emily for not being able to find literature depicting a life similar to her situation. And then I suggested that the girl write a book together that would describe her own experience, and we decided to write about high-functioning autism, about Asperger's syndrome, and not about "classic" autism, in order to help her learn more about her brother herself. My goal was purely therapeutic. It seemed to me that while helping Emily tell her own story, we would also discuss her emotions and feelings towards her brother, and she would be able to better understand her brother by gaining the necessary information about this developmental disorder. Gradually, Emily and I became more and more involved in our "project". I was touched and inspired by her stories of life with Daniel. And when Emily and I finally read our “book” to her parents (it consisted of only 8-10 pages), no one was hiding tears. I remember telling her parents, David and Bes, that such a "real" book could help children like Emily who have siblings with high-functioning autism or Asperger's.

My goal was purely therapeutic. It seemed to me that while helping Emily tell her own story, we would also discuss her emotions and feelings towards her brother, and she would be able to better understand her brother by gaining the necessary information about this developmental disorder. Gradually, Emily and I became more and more involved in our "project". I was touched and inspired by her stories of life with Daniel. And when Emily and I finally read our “book” to her parents (it consisted of only 8-10 pages), no one was hiding tears. I remember telling her parents, David and Bes, that such a "real" book could help children like Emily who have siblings with high-functioning autism or Asperger's.

This was the beginning of the book Through the Eyes of a Sister . With the help of the Hecht family (I talked to them, clarified some points), the book has changed a bit and now it looks the way you see it. The decision to put such personal records on public display was given to the girl not immediately and not easily. I really admire Emily's courage and her desire to help other children who have a sibling with high functioning autism or Asperger's in the family. I hope Emily's story will help you better understand your loved ones and choose the right path, as she helped me.

I really admire Emily's courage and her desire to help other children who have a sibling with high functioning autism or Asperger's in the family. I hope Emily's story will help you better understand your loved ones and choose the right path, as she helped me.

Yves Bend

Chapter 1

Meet Emily

Hello. My name is Emily and I am 9 years old. I want to tell you about my eleven year old brother Daniel. Daniel is autistic. He has a type of autism called high functioning, also called Asperger's syndrome. As Daniel's sister, I needed to know a lot about high functioning autism. I needed to understand what it is and what to do with it in the family. Before I learned about autism, I couldn't understand why my brother was so different from me and other kids I knew. I didn’t understand why he spoke loudly to himself so often, why he repeated what I said, or answered me in the same way that I told him myself, or why he clapped his hands when he was very excited.

My mom and dad told me that I often asked them, “Why is Daniel doing this?” when he did something weird or funny. But when I learned about autism and Asperger's, it really helped me understand my brother better. I now know why Daniel does a lot of things differently than me and what I should do about it. I would like to tell you about what I found out myself. It seems to me that if you have a brother or sister, a classmate or someone in the family with high-functioning autism, then you need to learn more about this, and this will help you a lot.

Chapter 2

Meet Daniel

When you first look at my brother Daniel, you won’t suspect anything at all. He's pretty cute. He has dark hair and brown eyes, and just like you and me, he has 2 eyes, 2 ears, two arms and legs, he walks, runs, talks, eats and plays. If you saw him and me together, walking down the street or playing ball, you would hardly be able to guess that he is somehow different from others. But if you watch a little longer, you will begin to notice that there is something about him that distinguishes him from other boys of his age.

But if you watch a little longer, you will begin to notice that there is something about him that distinguishes him from other boys of his age.

Sometimes Daniel just starts talking loudly to himself. We can go to the store or somewhere else, and all of a sudden he starts spouting nonsense. When we play hide and seek, of course, we love to make funny noises, but Daniel keeps talking to himself even when he's looking for me, so it looks like he's talking to a ghost. Sometimes he starts laughing out loud at things that don't seem funny at all, and no one around laughs anymore. Also, when he leaves the house, he definitely needs to take something with him, some toy or book, usually this is related to Walt Disney cartoons. When I was little, this did not seem strange to me, and I also sometimes carried my favorite toys with me. But now I'm already nine, and I don't do that anymore, because I'm big. Daniel does not understand that it looks stupid and funny: after all, he is 11 years old!

If you approach and try to speak to Daniel, he is usually friendly and has no problem telling you his name and how old he is. But he will not be able to tell where he lives, his phone number, and at the same time he may not look at you when you are talking to him. And if you ask him about something else, for example, ask him to watch his Game Boy, he may answer “no” or say something completely meaningless. Daniel doesn't understand how his Game Boy electronic game works. One day he thought that our friend broke it because he played it when the batteries were dead. It was difficult for Denil to understand that sometimes the batteries run out, and this does not mean at all that the thing is broken. And now, when this boy comes, Daniel hides his game so as not to "break".

But he will not be able to tell where he lives, his phone number, and at the same time he may not look at you when you are talking to him. And if you ask him about something else, for example, ask him to watch his Game Boy, he may answer “no” or say something completely meaningless. Daniel doesn't understand how his Game Boy electronic game works. One day he thought that our friend broke it because he played it when the batteries were dead. It was difficult for Denil to understand that sometimes the batteries run out, and this does not mean at all that the thing is broken. And now, when this boy comes, Daniel hides his game so as not to "break".

Chapter 3

Daniel also has feelings

Sometimes I worry that people who don't know that he's autistic might think Daniel is weird I'm afraid they'll start laughing at him if he laughs out loud or says something nonsense. There's another problem: Daniel is very easily offended. While they don't feel sarcasm and may not understand subtle or veiled banter, a person with autism also has feelings and may be offended. And maybe the next time you see a person who seems strange to you, you will think that he may have autism or some other disorder, and that he also has feelings, just like you. or mine, which are easy to hurt.

While they don't feel sarcasm and may not understand subtle or veiled banter, a person with autism also has feelings and may be offended. And maybe the next time you see a person who seems strange to you, you will think that he may have autism or some other disorder, and that he also has feelings, just like you. or mine, which are easy to hurt.

I hope that my story about my brother will help you understand and feel more comfortable with people like him. I hope you will also understand how important it is to speak pleasant words to him, praise and not offend. After all, Daniel wasn't asked if he wanted to be autistic, just as you and I don't choose our hair color or eye color at birth. He can't handle not being weird or funny. But he still wants to be loved and accepted by other children, just like me and you.

Chapter 4

How I found out about autism

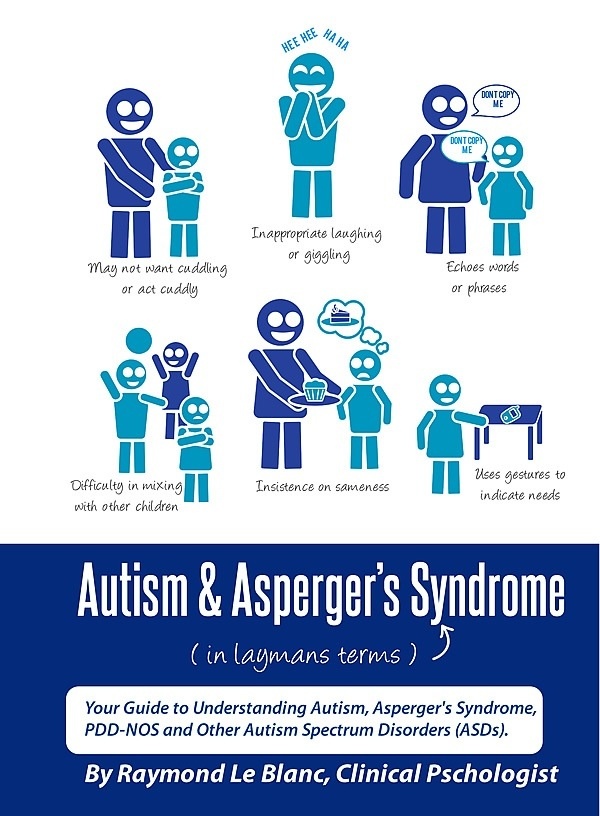

when he is not yet 3 years old. A child with autism is called "autistic". Many people say that autism is a type of disorder where children have trouble communicating, playing and learning. Not all autists are the same. Some autistic people have pronounced problems that are highly visible. This usually happens with moderate to severe autism. In other children, the problems are not so pronounced, and they are difficult to immediately recognize. This is called "high functioning autism or Asperger's Syndrome".

A child with autism is called "autistic". Many people say that autism is a type of disorder where children have trouble communicating, playing and learning. Not all autists are the same. Some autistic people have pronounced problems that are highly visible. This usually happens with moderate to severe autism. In other children, the problems are not so pronounced, and they are difficult to immediately recognize. This is called "high functioning autism or Asperger's Syndrome".

Children do not "grow out" of autism and get rid of it with age, but if they are helped, many problems can be solved. Children with autism think, feel and behave differently, have problems thinking and behaving because their brains do not work the way you and I do. Some parts of their brains have been malfunctioning since they were born. You can't "catch" autism from someone the way you might catch a cold or the flu. Doctors and scientists are working hard to understand how the brain of a person with autism is different and to find ways to help autistic children.

Chapter 5

Moderate to Severe Autism

First, let me tell you about "moderate (moderate) autism and severe (severe autism"). Such children usually have problems learning to speak and behave in society - getting to know, playing with others and understanding what people say. Many children with severe and moderate autism do not like loud sounds, bright colors, strong emotions in general, they cannot stand being touched. They usually don't like it when there are a lot of people around, and a big noisy crowd can piss them off. They also really don't like it when something changes, things don't go the way they always do (for example, they always eat Nestlé corn flakes for breakfast, and suddenly one morning mom gives them other cereal because they weren't in the store).

Sometimes children with severe autism like to do unusual things over and over again, such as rocking back and forth, running in circles, or staring at a light for a long time. Also, many children with moderate and severe autism do not know how to play with ordinary children. They do not know how to imagine something, to play pretend with toys. But at the same time, they can spend a lot of time lining up their toys in a long row or tasting different objects.

Also, many children with moderate and severe autism do not know how to play with ordinary children. They do not know how to imagine something, to play pretend with toys. But at the same time, they can spend a lot of time lining up their toys in a long row or tasting different objects.

Many children with moderate to severe autism tend to prefer strict order in everything. In their studies, such children need much more help, so they usually study in special school classes. And some autistic people have great talents, they are very good at some things, for example, music, mathematics, someone easily collects complex puzzles or quickly memorizes different facts or dates. And although children with autism are not often found with special talents and skills, some are able to do absolutely incredible things, for example, perform complex arithmetic operations with numbers in their minds in a few seconds.

Chapter 6

High Functioning Autism

Now let me tell you more about my brother Daniel. As I said, Daniel has a type of autism called high-functioning (HFA). Sometimes doctors and other professionals also refer to this as pervasive developmental disorder or Asperger's syndrome. This can be confused because Daniel may act like a child with more pronounced autism, although in fact his problems are not so serious. Because of this, it was not so easy for my parents and doctors to determine that Daniel really had autism (my brother was not diagnosed with autism until he was 3 years old). But my mom and dad were already worried when they noticed he had problems at a younger age, because Daniel learned to speak and play much later than other children.

As I said, Daniel has a type of autism called high-functioning (HFA). Sometimes doctors and other professionals also refer to this as pervasive developmental disorder or Asperger's syndrome. This can be confused because Daniel may act like a child with more pronounced autism, although in fact his problems are not so serious. Because of this, it was not so easy for my parents and doctors to determine that Daniel really had autism (my brother was not diagnosed with autism until he was 3 years old). But my mom and dad were already worried when they noticed he had problems at a younger age, because Daniel learned to speak and play much later than other children.

When I was little, I didn't know that Daniel was any different from me and other children. I remember when I was 3 years old and he was 5, we played together and had fun. I was sure that he was the same as me. But when I was already 6, I began to notice that he was different from me. I don't know how I felt when I first realized this. I wondered why, when he watches a movie, he laughs at something that is not funny at all, and why, on the contrary, he does not laugh at something funny. Sometimes I noticed that Daniel would start to giggle for no reason. Then I started laughing and my parents too, and then we were already laughing at nothing all together!

I wondered why, when he watches a movie, he laughs at something that is not funny at all, and why, on the contrary, he does not laugh at something funny. Sometimes I noticed that Daniel would start to giggle for no reason. Then I started laughing and my parents too, and then we were already laughing at nothing all together!

Chapter 7

How Daniel behaves with people and makes friends

My brother Daniel enjoys being with me, our family and friends. Sometimes people say that children with autism are like they are in their own little world. But Daniel usually acts very friendly towards other people and he even has friends. But it's much harder for him to make new friends than it is for me. Most children with high functioning autism want to have friends, but they don't know how to make friends and keep in touch with others.

Children need to learn to do certain things in order to feel good with other people and make friends. For example, you and I know how to look at a person when talking to them, how to play a game together and how to join someone else's game (for example, you can say: “Wow, how are you You're great, can I play with you too?"). This understanding of how to behave with people, children with high-functioning autism, as a rule, do not. For example, Daniel often forgets to look at the person who says something to him, so people sometimes do not understand whether he is listening to them or not. And Daniel only likes to talk about things that interest him, like his favorite Disney cartoons. But he usually forgets to ask others what they like and doesn't remember to talk about anything else.

For example, you and I know how to look at a person when talking to them, how to play a game together and how to join someone else's game (for example, you can say: “Wow, how are you You're great, can I play with you too?"). This understanding of how to behave with people, children with high-functioning autism, as a rule, do not. For example, Daniel often forgets to look at the person who says something to him, so people sometimes do not understand whether he is listening to them or not. And Daniel only likes to talk about things that interest him, like his favorite Disney cartoons. But he usually forgets to ask others what they like and doesn't remember to talk about anything else.

Many children, like you and me, communicate easily with other people. We learn this intuitively, without really thinking about it, because we are constantly among other people, friends, in the family. But Daniel needs help to understand how to communicate with other people. He needs to practice, and he needs to be taught what he should say and what to do, just as you and I need to learn to read and count.