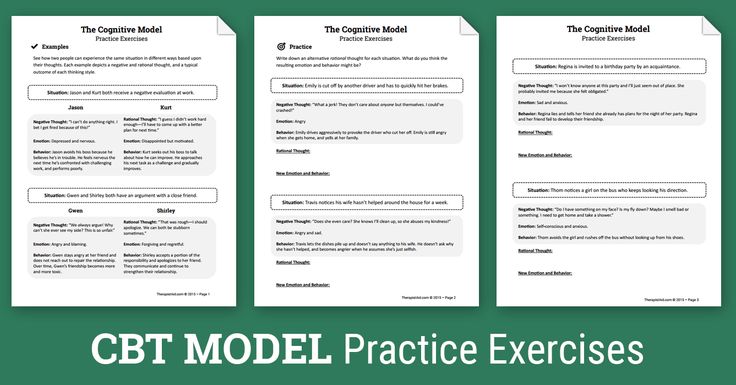

Cognitive behavioral examples

What Is It and Who Can It Help?

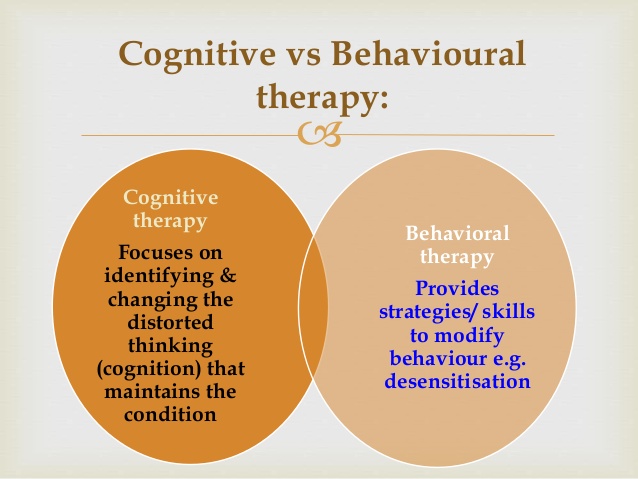

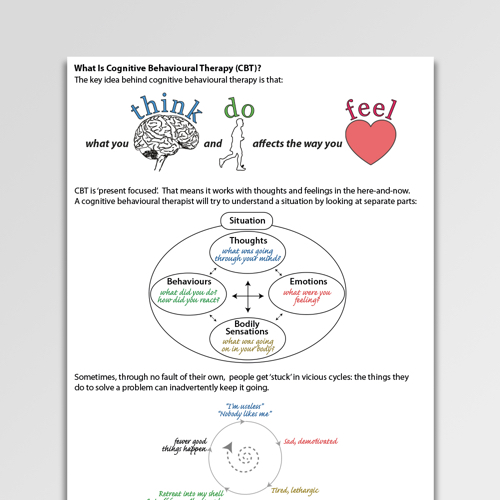

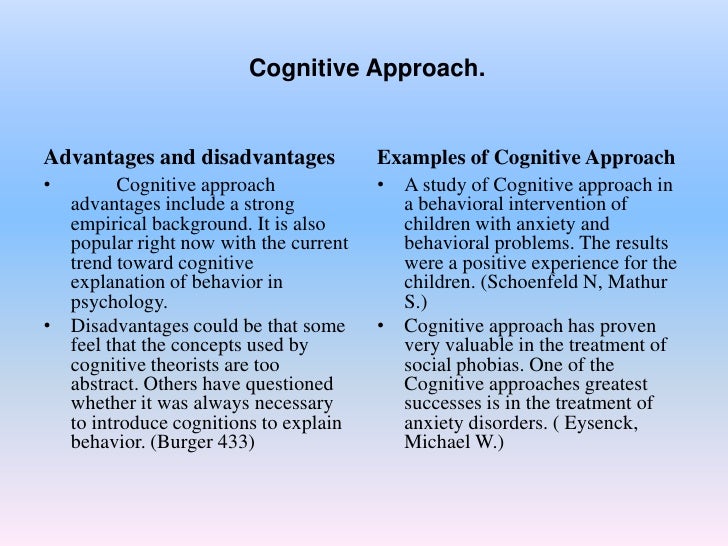

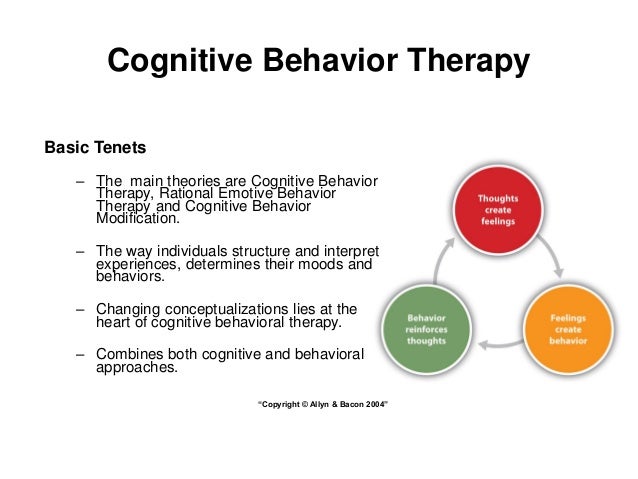

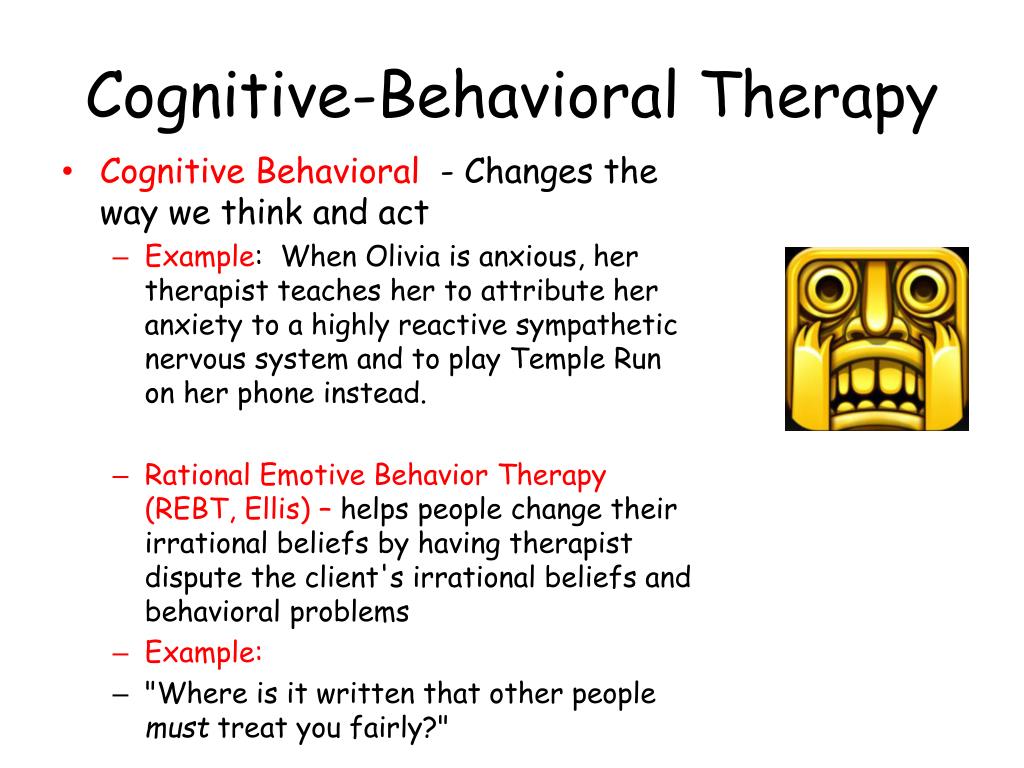

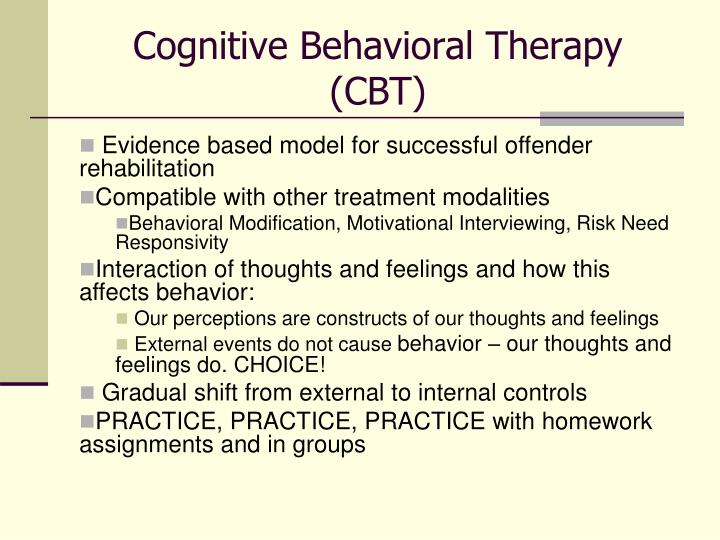

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a treatment approach that helps you recognize negative or unhelpful thought and behavior patterns.

CBT aims to help you identify and explore the ways your emotions and thoughts can affect your actions. Once you notice these patterns, you can begin learning how to change your behaviors and develop new coping strategies.

CBT addresses the here and now, and focuses less on the past. For some conditions in some people, other forms of psychotherapy are equally or even more effective. The key is that there is no one size that fits all.

Read on to learn more about CBT, including:

- core concepts

- what it can help treat

- what to expect during a session

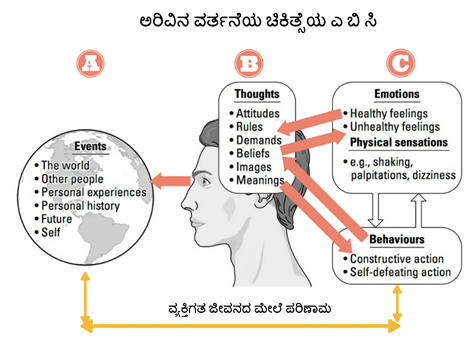

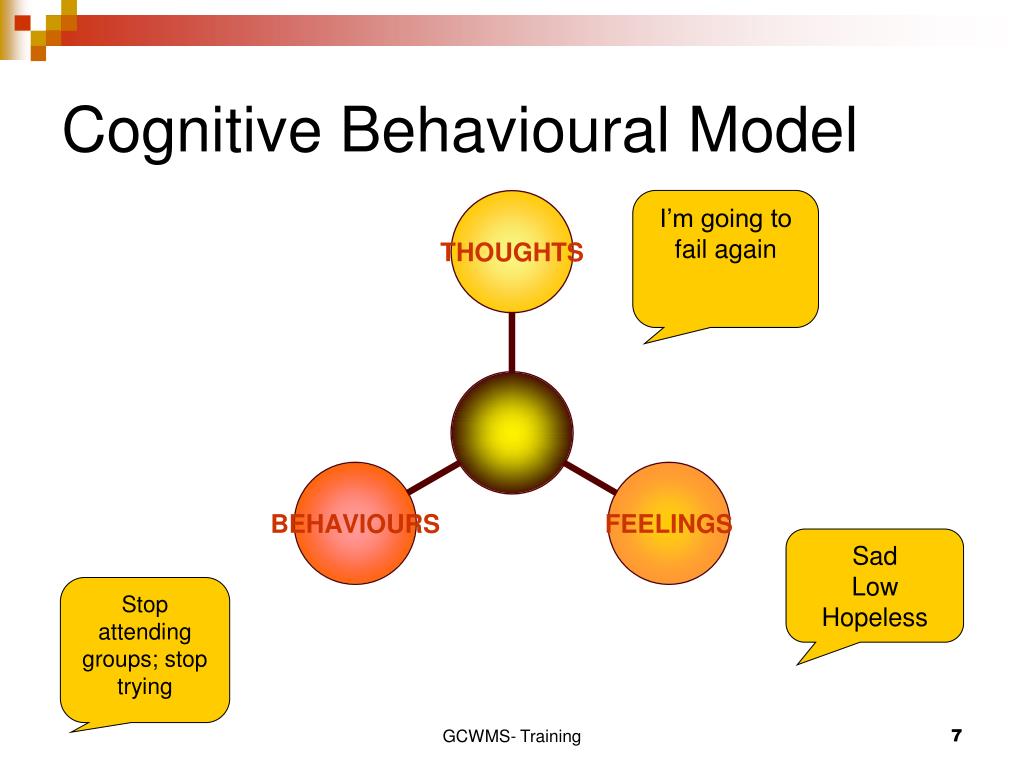

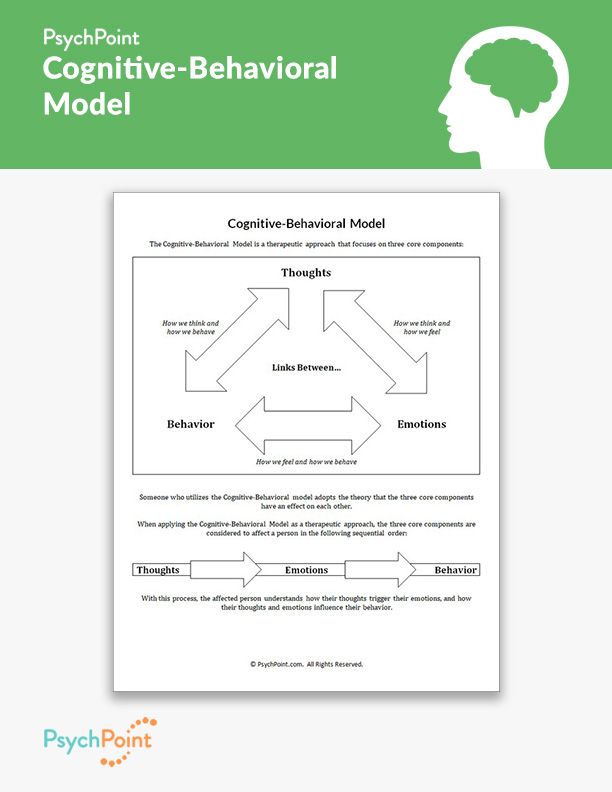

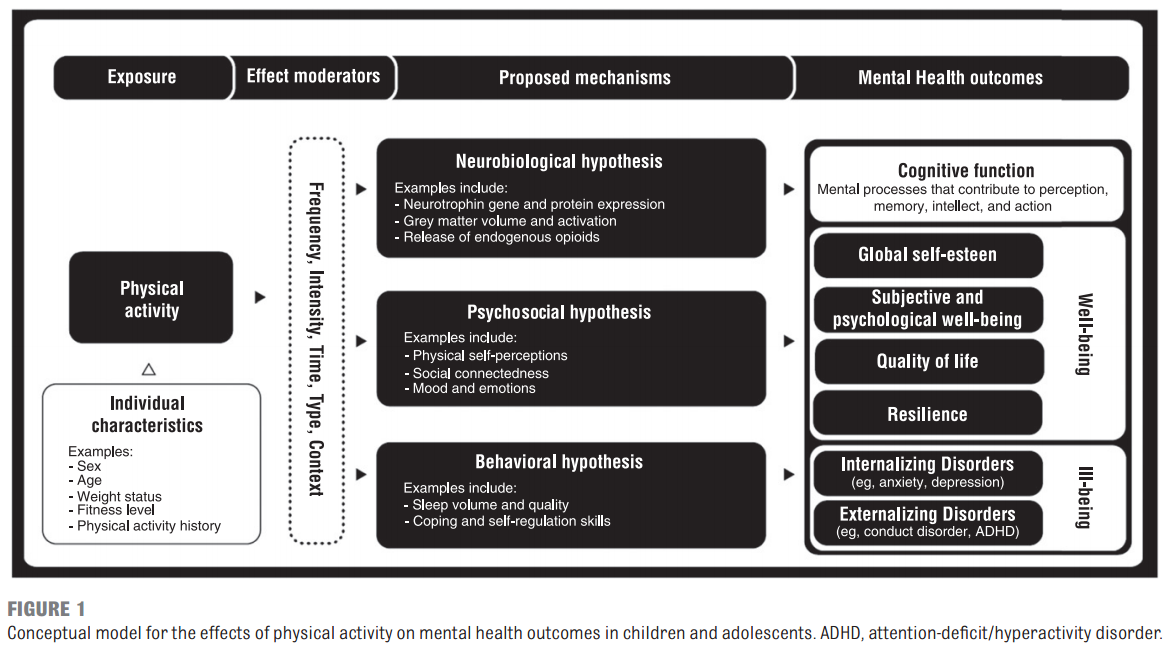

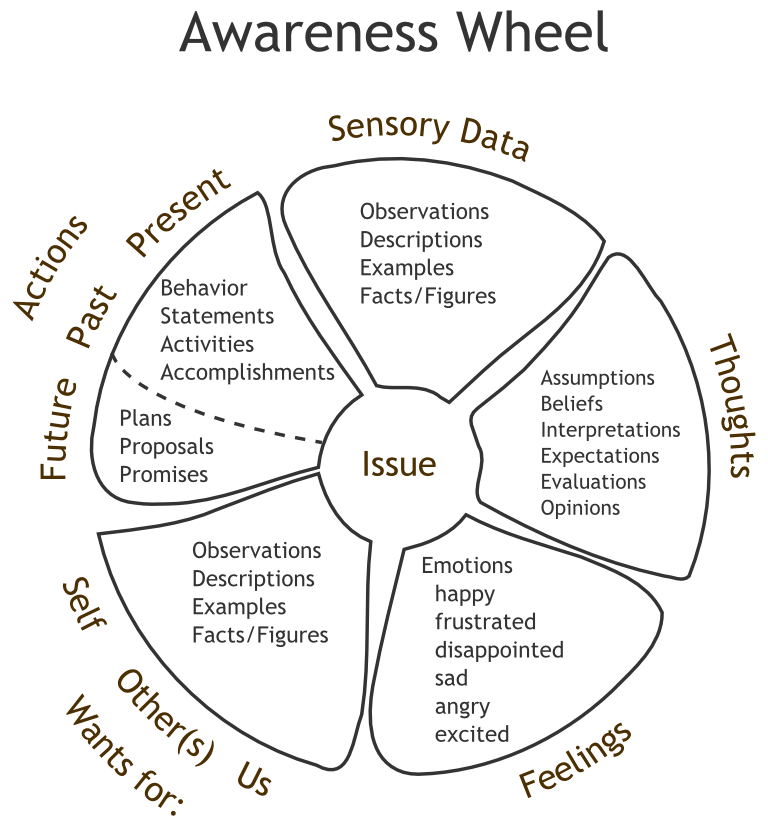

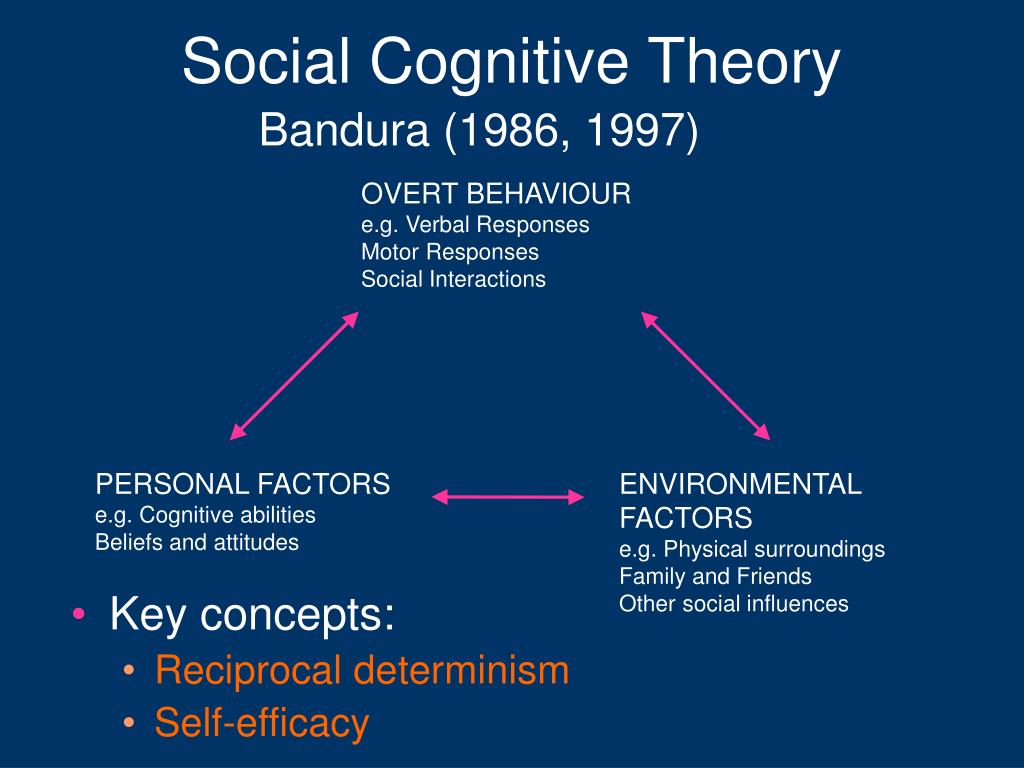

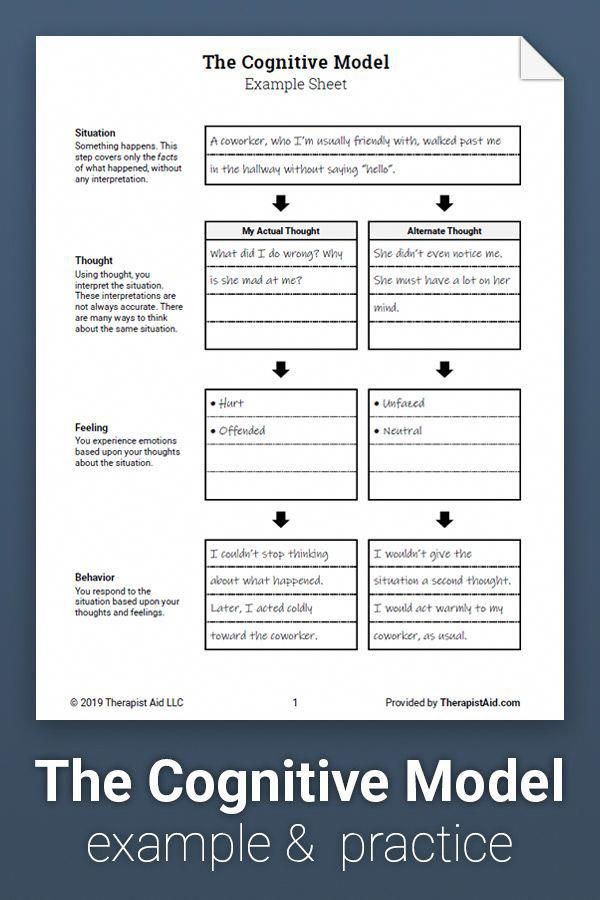

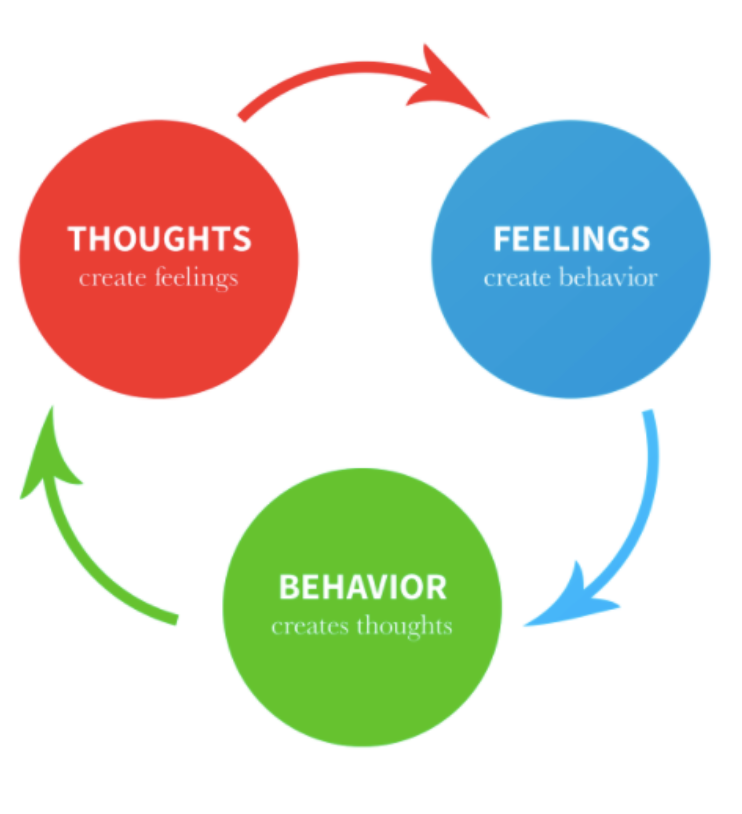

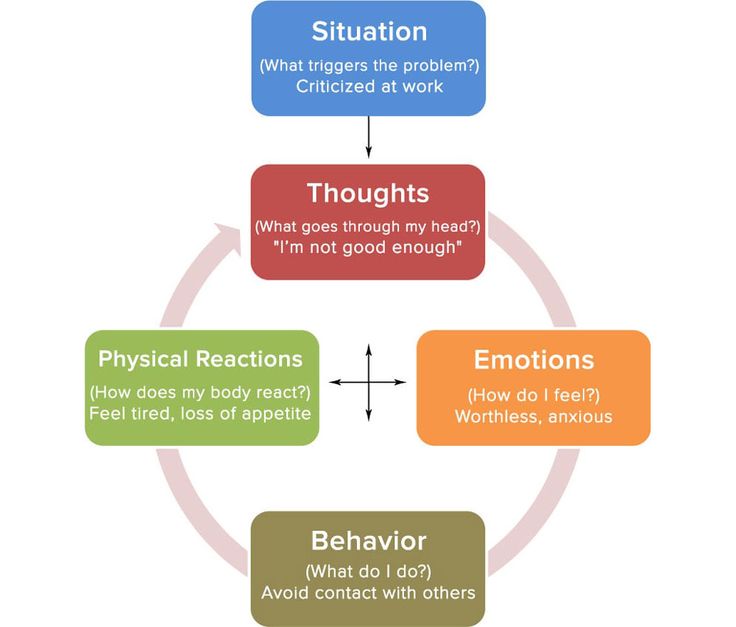

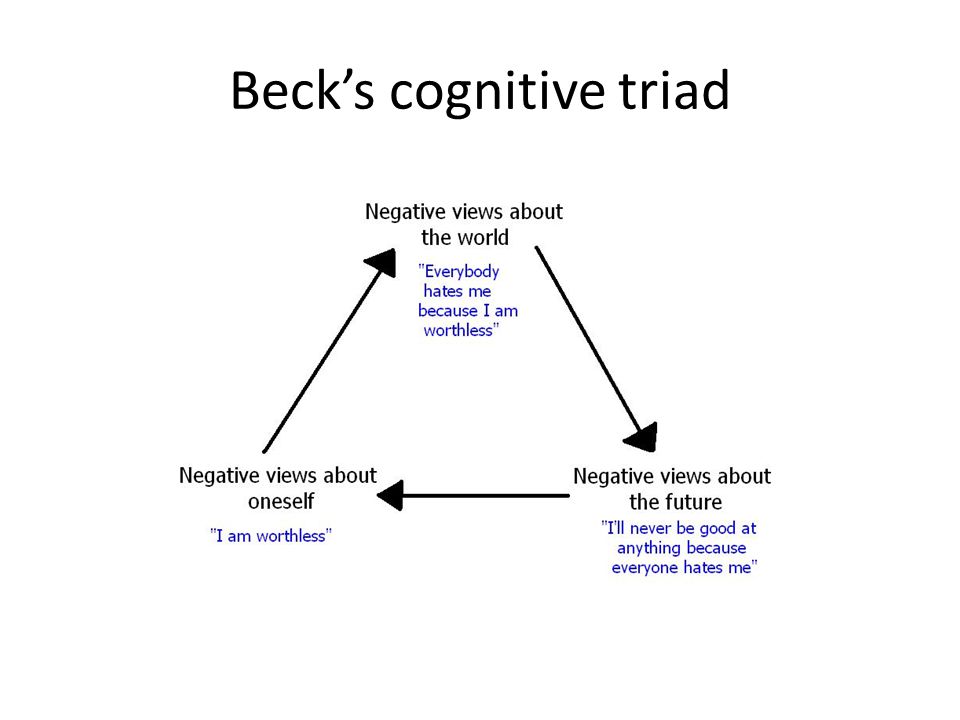

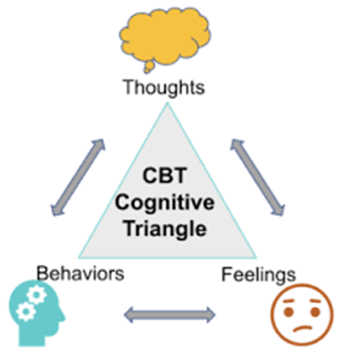

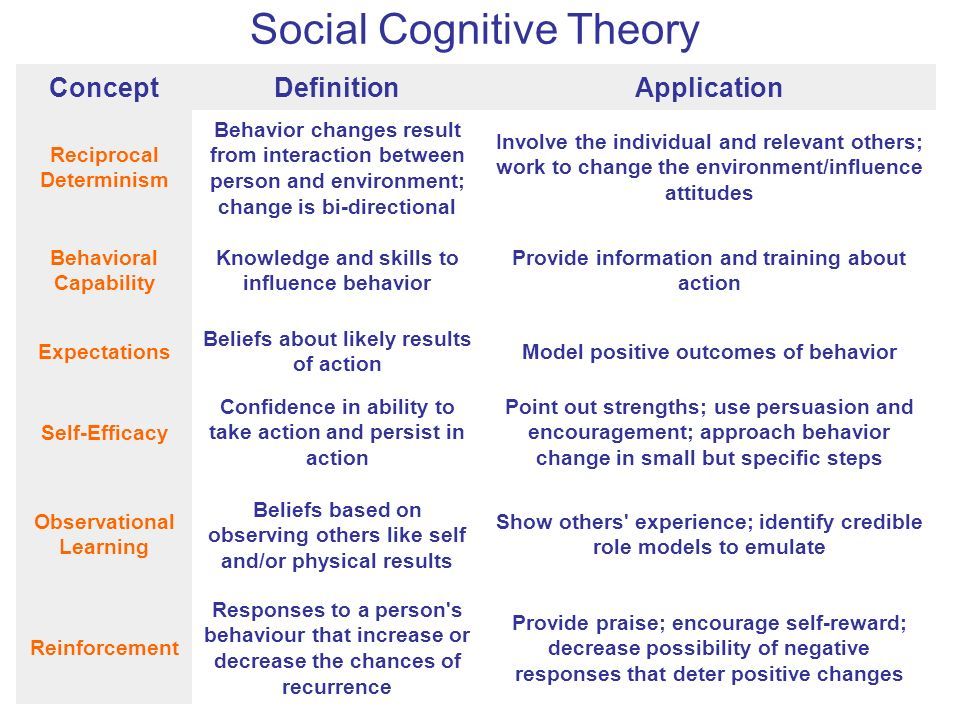

CBT is largely based on the idea that your thoughts, emotions, and actions are connected. In other words, the way you think and feel about something can affect what you do.

If you’re under a lot of stress at work, for example, you might see situations differently and make choices you wouldn’t ordinarily make. But another key concept of CBT is that these thought and behavior patterns can be changed.

According to the American Psychological Association, the core concepts of CBT include:

- psychological issues are partly based on unhelpful ways of thinking

- psychological issues are partly based on learned patterns of behavior

- those living with these issues can improve with better coping mechanisms and management to help relieve their symptoms

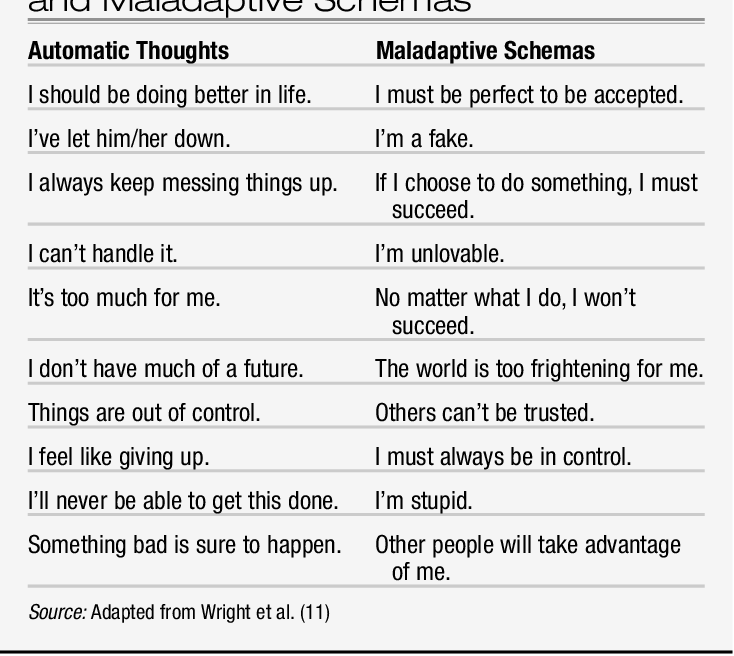

The cycle of thoughts and behaviorsHere’s a closer look at how thoughts and emotions can influence behavior — in a positive or negative way:

- Inaccurate or negative perceptions or thoughts contribute to emotional distress and mental health concerns.

- These thoughts and the resulting distress sometimes lead to unhelpful or harmful behaviors.

- Eventually, these thoughts and resulting behaviors can become a pattern that repeats itself.

- Learning how to address and change these patterns can help you deal with problems as they arise, which can help reduce future distress.

So how does one go about reworking these patterns? CBT involves the use of many varied techniques. Your therapist will work with you to find the ones that work best for you.

Typical treatment often involves the following:

- recognizing how inaccurate thinking can worsen problems

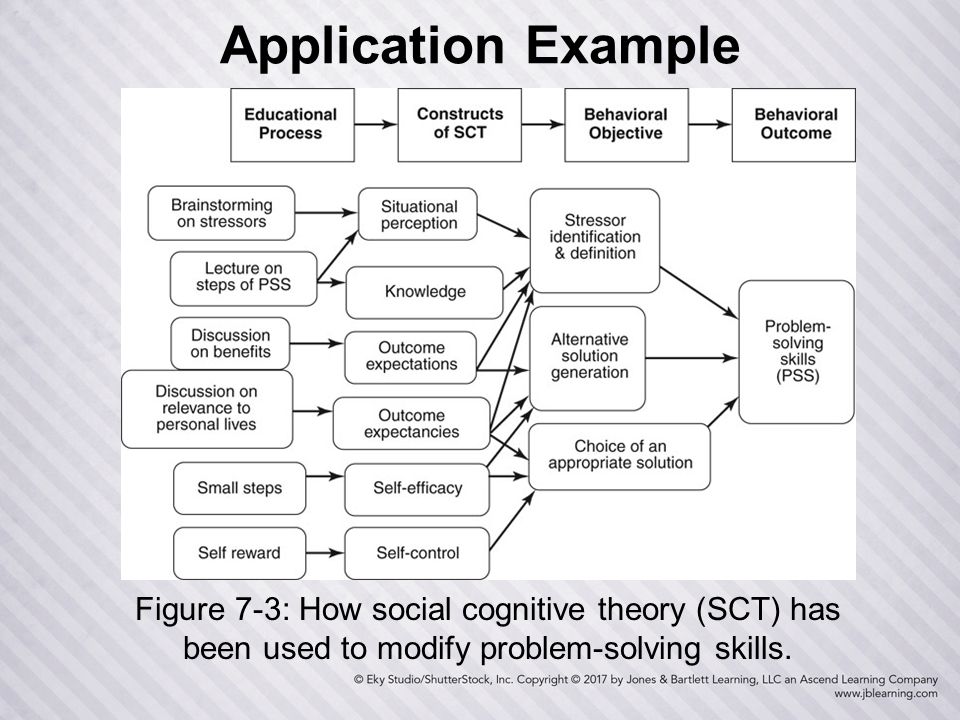

- learning new problem-solving skills

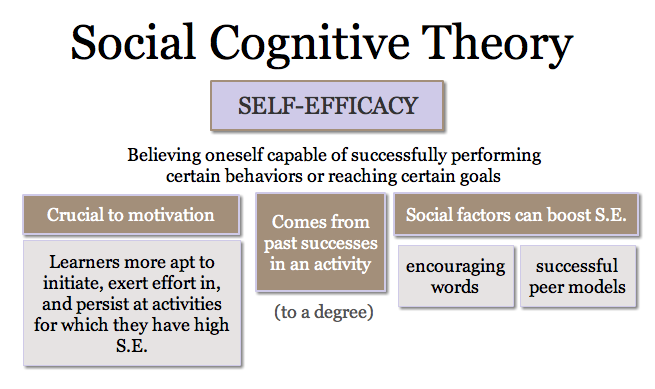

- gaining confidence and a better understanding and appreciation of your self-worth

- learning how to face fears and challenges

- using role play and calming techniques when faced with potentially challenging situations

The goal of these techniques is to replace unhelpful or self-defeating thoughts with more encouraging and realistic ones.

For example, “I’ll never have a lasting relationship” might become, “None of my previous relationships have lasted very long. Reconsidering what I really need from a partner could help me find someone I’ll be compatible with long term.”

These are some of the most popular techniques used in CBT:

- SMART goals.

SMART goals are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-limited.

SMART goals are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-limited. - Guided discovery and questioning. By questioning the assumptions you have about yourself or your current situation, your therapist can help you learn to challenge these thoughts and consider different viewpoints.

- Journaling. You might be asked to jot down negative beliefs that come up during the week and the positive ones you can replace them with.

- Self-talk. Your therapist may ask what you tell yourself about a certain situation or experience and challenge you to replace negative or critical self-talk with compassionate, constructive self-talk.

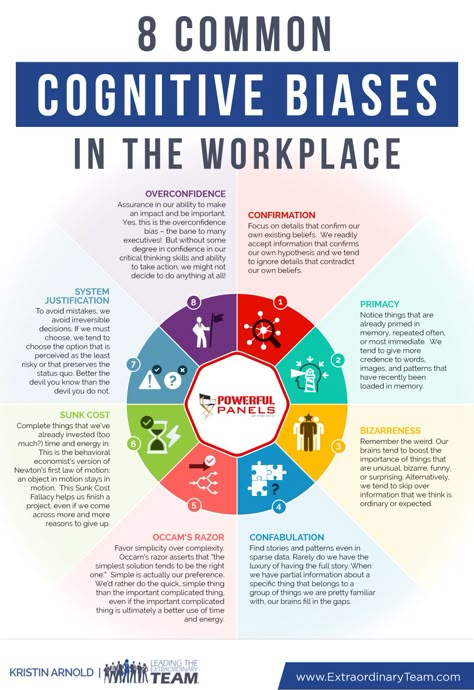

- Cognitive restructuring. This involves looking at any cognitive distortions affecting your thoughts — such as black-and-white thinking, jumping to conclusions, or catastrophizing — and beginning to unravel them.

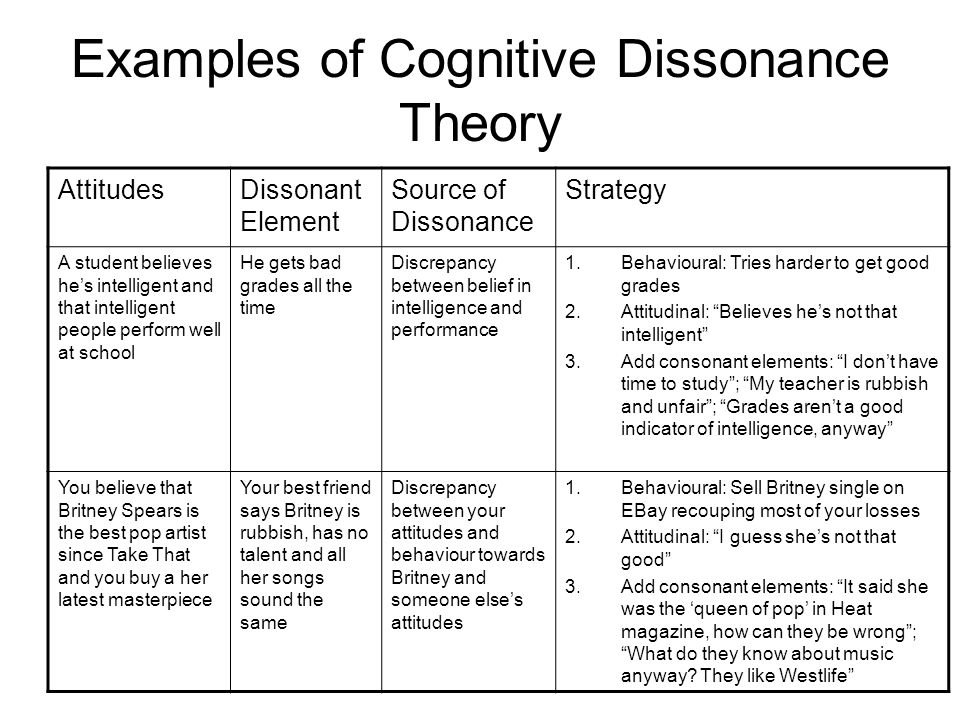

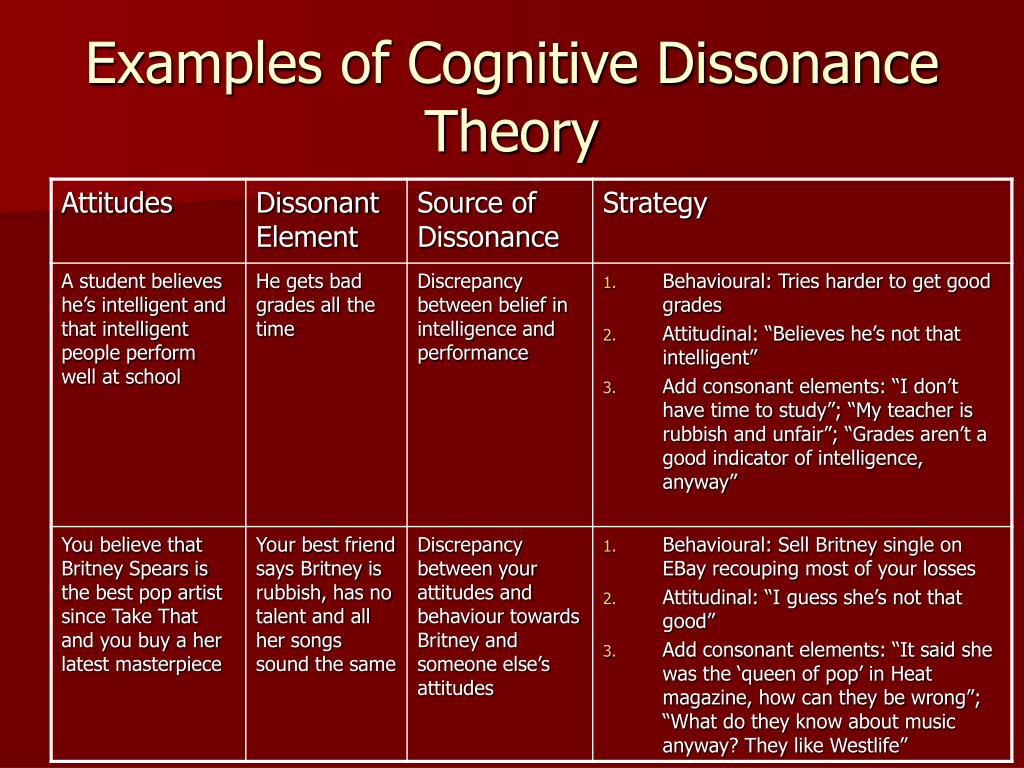

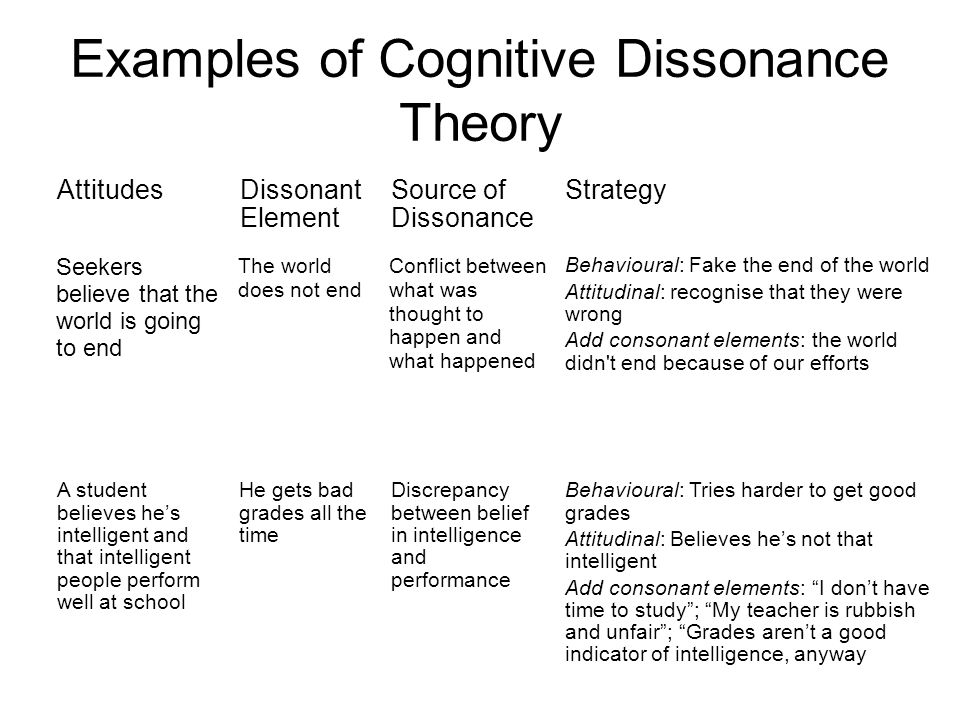

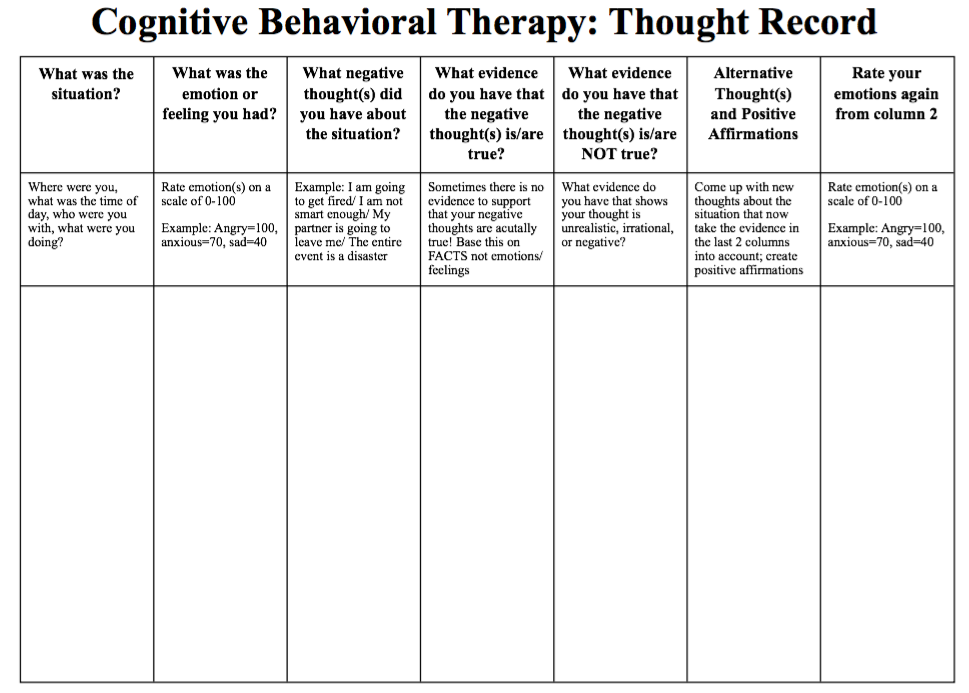

- Thought recording. In this technique, you’ll record thoughts and feelings experienced during a specific situation, then come up with unbiased evidence supporting your negative belief and evidence against it.

You’ll use this evidence to develop a more realistic thought.

You’ll use this evidence to develop a more realistic thought. - Positive activities. Scheduling a rewarding activity each day can help increase overall positivity and improve your mood. Some examples might be buying yourself fresh flowers or fruit, watching your favorite movie, or taking a picnic lunch to the park.

- Situation exposure. This involves listing situations or things that cause distress, in order of the level of distress they cause, and slowly exposing yourself to these things until they lead to fewer negative feelings. Systematic desensitization is a similar technique where you’ll learn relaxation techniques to help you cope with your feelings in a difficult situation.

Homework is another important part of CBT, regardless of the techniques you use. Just as school assignments helped you practice and develop the skills you learned in class, therapy assignments can help you become more familiar with the skills you’re developing.

This might involve more practice with skills you learn in therapy, such as replacing self-criticizing thoughts with self-compassionate ones or keeping track of unhelpful thoughts in a journal.

CBT can help with a range of things, including the following mental health conditions:

- depression

- eating disorders

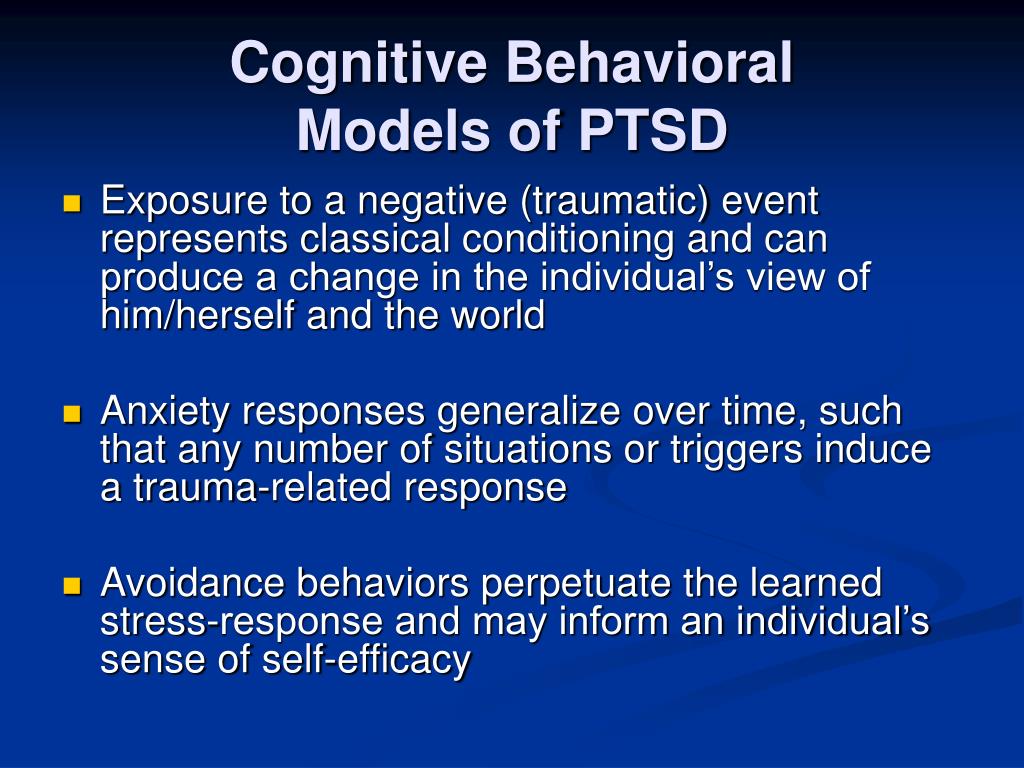

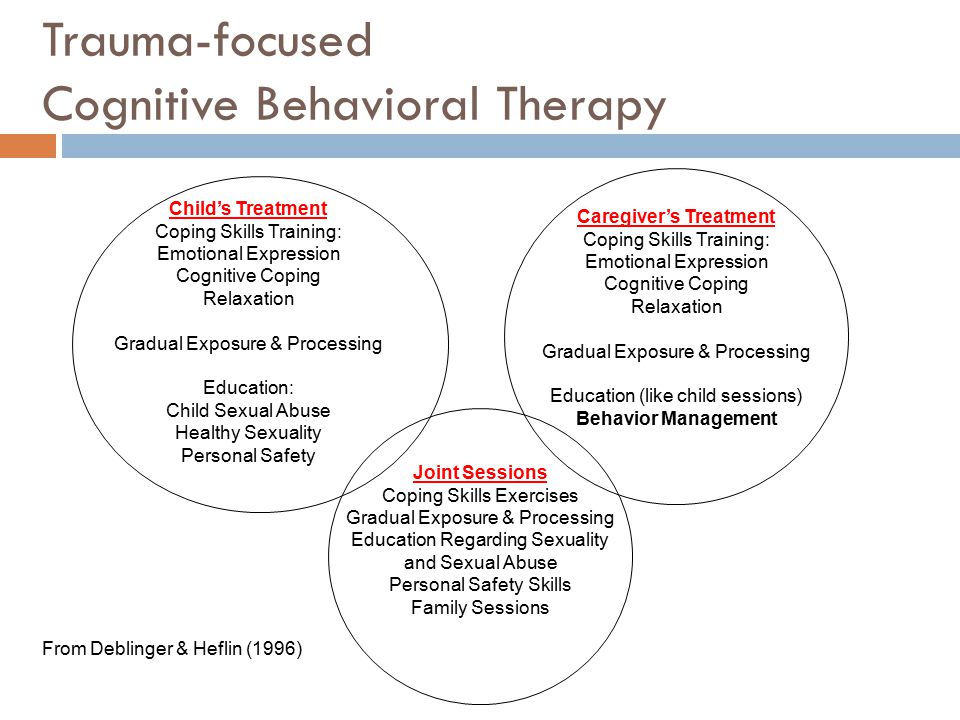

- post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- anxiety disorders, including panic disorder and phobia

- obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- schizophrenia

- bipolar disorder

- substance misuse

But you don’t need to have a specific mental health condition to benefit from CBT. It can also help with:

- relationship difficulties

- breakup or divorce

- a serious health diagnosis, such as cancer

- grief or loss

- chronic pain

- low self-esteem

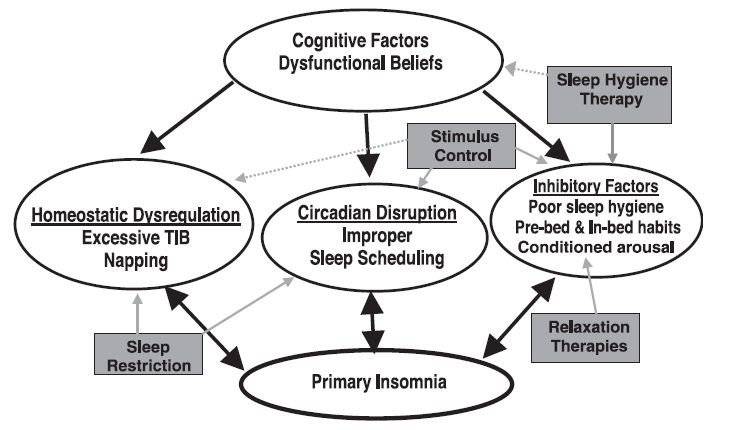

- insomnia

- general life stress

CBT is one of the most studied therapy approaches. In fact, many experts consider it to be the best treatment available for a number of mental health conditions.

Here’s some research behind it:

- A 2018 review of 41 studies looking at CBT in the treatment of anxiety disorders, PTSD, and OCD found evidence to suggest that it could help improve symptoms in all of these situations. The approach was most effective for OCD, anxiety, and stress.

- A 2018 study looking at CBT for anxiety in young people found that the approach appeared to have good long-term results. More than half of the participants in the study no longer met criteria for anxiety at follow-up, which took place 2 or more years after they completed therapy.

- Research published in 2011 suggests that CBT can not only help treat depression, but it may also help reduce the chances of relapse after treatment. Additionally, it may help improve symptoms of bipolar disorder when paired with medication, but more research is needed to help support this finding.

- One 2017 study looking at 43 people with OCD found evidence to suggest brain function appeared to improve after CBT, particularly with regard to resisting compulsions.

- A 2018 study looking at 104 people found evidence to suggest CBT can also help improve cognitive function for people with major depression and PTSD.

- Research from 2010 shows that CBT can also be an effective tool when dealing with substance misuse. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, CBT can also be used to help people cope with addiction and avoid relapse after treatment.

- Newer research from 2020 and 2021 even shows that both virtual and internet-based CBT hold promise for effective treatment. More research is needed to see how to best treat people virtually and if blended techniques could also be beneficial.

Cognitive behavioral therapy is often considered the gold standard of psychotherapy — but it’s certainly not the only approach. Read on to discover the different types of therapy and which one may work best for your needs.

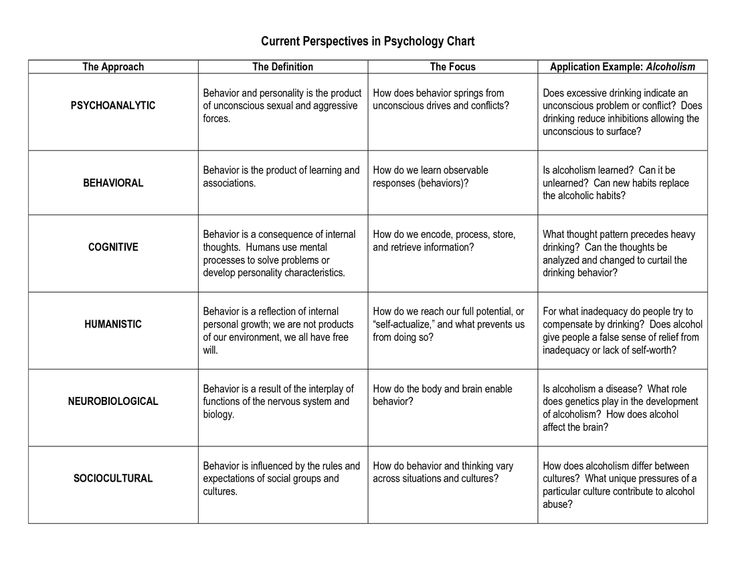

Psychodynamic therapy

Psychodynamic therapy is often a longer-term approach to mental health treatment compared with CBT.

Psychodynamic therapy was developed from psychoanalysis, where you are encouraged to talk about anything on your mind to uncover patterns in thoughts or behavior. In psychodynamic therapy, you’ll examine your emotions, relationships, and thought patterns to explore the connection between your unconscious mind and your actions.

This form of therapy can be useful for addressing a variety of mental health conditions including depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and substance use disorder.

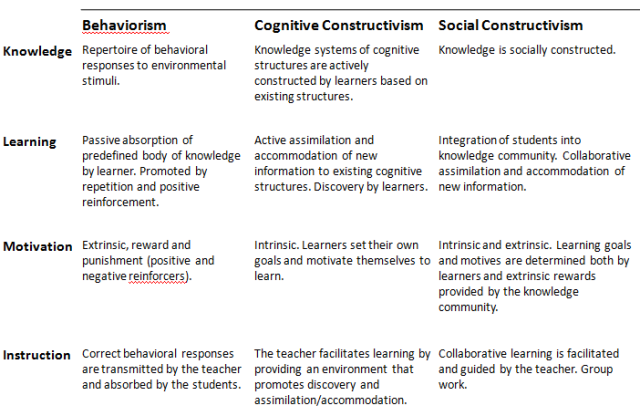

Behavioral therapy

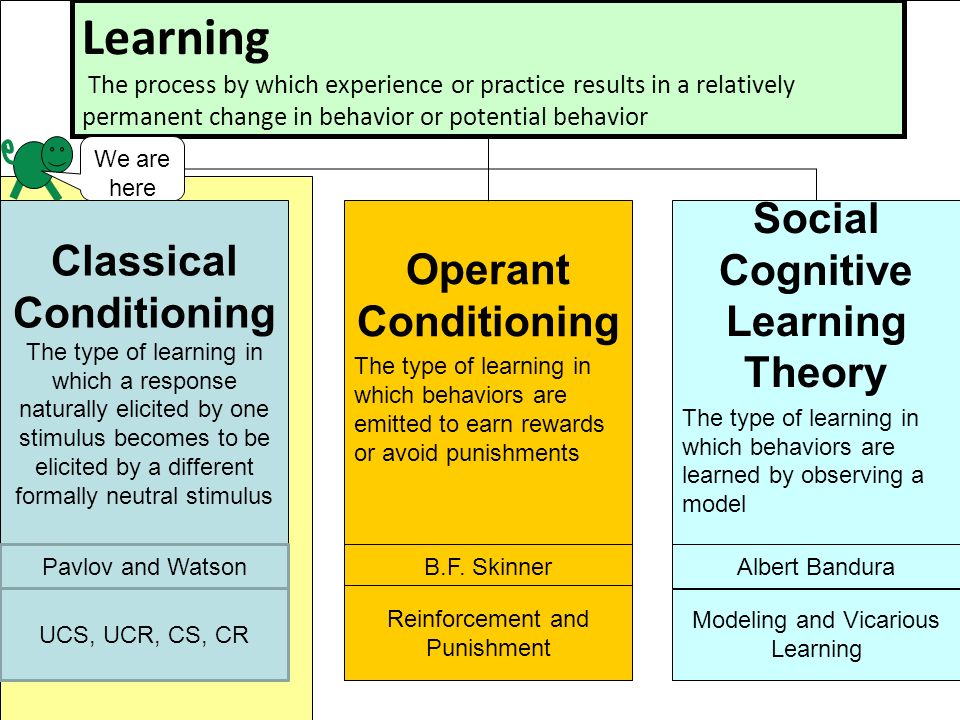

According to behavioral theory, certain behaviors that might affect your life negatively develop from things you learned in your past. In behavioral therapy, instead of focusing on unconscious reasons for your behaviors, your therapist will help you identify ways to change behavioral reactions and patterns that cause distress.

Behavioral therapy is often focused on current issues and how to change them. People most commonly seek this form of therapy to treat depression, anxiety, panic disorders, and anger issues.

Humanistic therapy

Humanistic therapy is based on the idea that your unique worldview impacts your choices and actions. In this therapeutic approach, you’ll work with a therapist to better understand your worldview and develop true self-acceptance.

Humanistic therapy tends to focus more on your day-to-day life than other types of therapy. Humanistic therapists work from the idea that you are the expert in your difficulties, and they will let you guide the direction of your sessions, trusting that you know what you need to talk about. Instead of treating a specific diagnosis, this form of therapy is often used to help you develop as a whole.

It’s important to note that this comparison of therapeutic approaches, subtypes, and issues that each type of therapy is useful for addressing is not exhaustive. Each therapist will take their own approach when working with clients, and the type of therapy that works best for you will depend on a number of factors.

There are various forms of therapy that fit under the CBT umbrella. You’ll work with your therapist to find which type of therapy works best for you and your goals.

You’ll work with your therapist to find which type of therapy works best for you and your goals.

These subtypes include:

- Exposure therapy. This type of therapy involves slowly introduces anxiety-inducing activities/situations into your life for measured periods of time (one to two hours up to three times a day, for example). This subtype can be particularly effective for people who deal with phobias or obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

- Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT). DBT incorporates things like mindfulness and emotional regulation through talk therapy in an individual or group setting. This subtype can be particularly effective for people who deal with borderline personality disorder (BPD), eating disorders, or depression.

- Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). ACT is therapy that involves learning to accept negative or unwanted thoughts. This subtype may be particularly effective for people who deal with intrusive thoughts or catastrophic thinking.

- Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT). MBCT uses mindfulness techniques and meditation along with cognitive therapy. This subtype can be particularly effective for people who deal with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).

- Rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT). REBT is the original form of CBT and focuses on negative thought patterns and how they influence issues with emotions or behaviors. This subtype can be particularly effective for anything from anxiety to depression, sleep issues to addictive behaviors and more.

CBT can be used for a wide variety of mental health issues — as mentioned above — and including schizophrenia, insomnia, bipolar disorder, and psychosis. Some people even turn to CBT for help coping with chronic health issues, like irritable bowel syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome, and fibromyalgia. That said, some sources say CBT may not be for people who have brain diseases, brain injuries, or other issues that impact thinking.

Whereas other types of therapy may look at how previous events have affected your current state of mind, CBT tends to focus much more on current issues and moving forward. CBT also focuses exclusively on the individual versus any family problems or other situations that may impact a person’s life.

Perhaps most important of all, CBT is for people who want to take a very active role in their own healing process. While the therapist helps to break down different thoughts and feelings in therapy sessions, each session likely involves getting some type of homework intended to apply different learned coping skills in everyday life.

There are benefits to engaging in any type of therapy — not just for yourself, but also for your family members, partner, or other people in your life.

Benefits and pros specifically related to CBT:

- The overall course of therapy is short. The duration of therapy tends to be shorter than in other types — typically five to 20 sessions in all.

- As a result, CBT may be more affordable than other options that take place over a longer period of time. It may also be more affordable if you get it in a group setting.

- CBT reaps long-term results. Research on depression shows that people who have had CBT are less likely to relapse than people who took antidepressant medications with no therapy.

- Sessions are flexible and offered in various formats. For example, you can go to in-person sessions that are either individual or group. Some people even get CBT online or via phone.

- Skills learned in therapy can be applied directly to everyday life. The goal of CBT is to give tools to the person receiving therapy. These tools help them take control of their issues during the course of therapy and beyond.

- Playing an active role in healing may be empowering to people who get CBT. With time, the goal for people in therapy is to overcome issues on their own using the tools they picked up in their sessions.

- CBT be used with or without medication. Some people may only need CBT while others may find it a useful complement to medications they are taking.

Beginning therapy can seem overwhelming. It’s OK to feel nervous about your first session. You might wonder what the therapist will ask. You may even feel anxious about sharing your difficulties with a stranger.

CBT sessions tend to be very structured, but your first appointment may look a bit different.

Here’s a high-level look at what to expect during that first visit:

- Your therapist will ask about symptoms, emotions, and feelings you experience. Emotional distress often manifests physically, too. Symptoms such as headaches, body aches, or stomach upset may be relevant, so it’s a good idea to mention them.

- They’ll also ask about the specific difficulties you’re experiencing. Feel free to share anything that comes to mind, even if it doesn’t bother you too much. Therapy can help you deal with any challenges you experience, large or small.

- You’ll go over general therapy policies, such as confidentiality, and talk about therapy costs, session length, and the number of sessions your therapist recommends.

- You’ll talk about your goals for therapy, or what you want from treatment.

Feel free to ask any questions you have as they come up. You might consider asking:

- about trying medication along with therapy, if you’re interested in combining the two

- how your therapist can help if you’re having thoughts of suicide or find yourself in a crisis

- if your therapist has experience helping others with similar concerns

- how you’ll know therapy is helping

- what will happen in the other sessions

In general, seeing a therapist you can communicate and work well with will help you get the most out of your therapy sessions. If something doesn’t feel right about one therapist, it’s perfectly OK to see someone else. Not every therapist will be a good fit for you or your situation.

CBT can be helpful. But if you decide to try it, there are a few things to keep in mind.

It’s not a cure

Therapy can help improve concerns you’re experiencing, but it will not necessarily eliminate them. Mental health issues and emotional distress could persist, even after therapy ends.

The goal of CBT is to help you develop the skills to deal with difficulties on your own in the moment when they come up. Some people view the approach as training to provide their own therapy.

Results take time

CBT can last for weeks or months, usually with one session each week. In your first few sessions, you and your therapist will likely talk about how long therapy might last.

That being said, it’ll take some time before you see results. If you don’t feel better after a few sessions, you might worry therapy isn’t working, but give it time. Keep doing your homework and practicing your skills between sessions.

Undoing deep-set patterns is major work, so go easy on yourself.

It can be challenging

Therapy can challenge you emotionally. It often helps you get better over time, but the process can be difficult. You’ll need to talk about things that might be painful or distressing. Don’t worry if you cry during a session — it can be a typical experience during therapy.

It’s just one of many options

While CBT can be helpful for many people, it does not work for everyone. If you don’t see any results after a few sessions, do not feel discouraged. Check in with your therapist.

A good therapist can help you recognize when one approach is not working. They can usually recommend other approaches that might help more.

How to find a therapistFinding a therapist can feel daunting, but it does not have to be. Start by asking yourself a few basic questions:

- What issues do you want to address? These can be specific or vague.

- Are there any specific traits you’d like in a therapist? For example, are you more comfortable with someone who shares your gender?

- How much can you realistically afford to spend per session? Do you want someone who offers sliding-scale prices or payment plans?

- Where will therapy fit into your schedule? Do you need a therapist who can see you on a specific day of the week? Or someone who has sessions at night?

- Next, start making a list of therapists in your area.

If you live in the United States, head over to the American Psychological Association’s therapist locator.

Concerned about the cost? Our guide to affordable therapy can help.

Online therapy options

Read our review of the best online therapy options to help find the right fit for you.

What does a cognitive behavioral therapist do?

Typical CBT treatment often involves identifying personal beliefs or feelings that negatively impact your life and learning new problem-solving skills. Your therapist will work to help you gain confidence and better understand and appreciate your self-worth by facing fears and learning to use calming techniques during challenging situations.

There are a number of techniques your therapist might use during a session, but some of the most popular involve:

- setting achievable goals

- practicing cognitive restructuring

- journaling

- undergoing situation exposure

A cognitive behavioral therapist will often assign homework to help you practice the skills you learn in therapy, such as replacing self-criticizing thoughts or journaling.

What are some cognitive behavioral interventions?

There are a number of interventions, or techniques, used during CBT.

All cognitive behavioral interventions share a number of general characteristics, including:

- therapist-client collaboration

- an emphasis on environment-behavior relations

- a time-limited and present focus

Common CBT techniques include:

- thought recording and journaling

- exposure therapy

- role-playing

What can I expect in CBT?

CBT focuses on finding ways to change current thought patterns and behaviors that are negatively impacting your life.

CBT is usually a short-term process that provides you with tools to solve problems you are currently going through. While specific goals should be set by you and the therapist, the general goal of CBT is to reframe your negative thoughts into positive feelings and behaviors.

What are examples of cognitive behavioral therapy?

Examples of CBT techniques might include the following:

- Exposing yourself to situations that cause anxiety, like going into a crowded public space.

- Journaling about your thoughts throughout the day and recording your feelings about your thoughts.

- Engaging in mindfulness meditation, where you tune into the thoughts that come into your mind and let them pass without judgment.

- Looking at overwhelming tasks in a new way by breaking them up into smaller, more manageable pieces.

- Scheduling activities that make you nervous or give you anxiety.

- Role-playing to practice social skills or to improve your communication skills.

What is the goal of CBT?

People come to therapy for a variety of reasons, so the individual goal will vary by person. With CBT, the ultimate goal is to focus on the relationship between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

Through therapy, exercises, and homework, a therapist encourages people to recognize and gain control over their automatic thoughts and to learn ways to change their behaviors. As a result, a person may feel better, leading to a more positive cycle between these three things.

In other words: Positive feelings = positive thoughts = positive behaviors.

CBT may be a good therapy choice for you if you’re looking for something that’s focused on current problems you’re facing versus those that happened in the past.

It’s a short-term therapy that requires you to be actively involved in the process. Meeting with a therapist can help you identify your therapy goals and discover whether CBT or its subtypes are the right choice in your particular situation.

If CBT isn’t what’s best for you, there are various other types of therapy that may be a better fit. Reach out to a doctor or a licensed mental health professional for help navigating the options.

Case Study: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

This case example explains how Jill's therapist used a cognitive intervention with a written worksheet as a starting point for engaging in Socratic dialogue.

About this Example

This is a case example for the treatment of PTSD using Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. It is strongly recommended by the APA Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of PTSD. Download case example (PDF, 108KB).

It is strongly recommended by the APA Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of PTSD. Download case example (PDF, 108KB).

Jill's Story

Jill, a 32-year-old Afghanistan war veteran, had been experiencing PTSD symptoms for more than five years. She consistently avoided thoughts and images related to witnessing her fellow service members being hit by an improvised explosive device (IED) while driving a combat supply truck. Over the years, Jill became increasingly depressed and began using alcohol on a daily basis to help assuage her PTSD symptoms. She had difficulties in her employment, missing many days of work, and she reported feeling disconnected and numb around her husband and children. In addition to a range of other PTSD symptoms, Jill had a recurring nightmare of the event in which she was the leader of a convoy and her lead truck broke down. She waved the second truck forward, the truck that hit the IED, while she and her fellow service members on the first truck worked feverishly to repair it. Consistent with the traumatic event, her nightmare included images of her and the service members on the first truck smiling and waving at those on the second truck, and the service members on the second truck making fun of the broken truck and their efforts to fix it — “Look at that piece of junk truck — good luck getting that clunker fixed.”

Consistent with the traumatic event, her nightmare included images of her and the service members on the first truck smiling and waving at those on the second truck, and the service members on the second truck making fun of the broken truck and their efforts to fix it — “Look at that piece of junk truck — good luck getting that clunker fixed.”

After a thorough assessment of her PTSD and comorbid symptoms, psychoeducation about PTSD symptoms, and a rationale for using trauma focused cognitive interventions, Jill received 10 sessions of cognitive therapy for PTSD. She was first assigned cognitive worksheets to begin self-monitoring events, her thoughts about these events, and consequent feelings. These worksheets were used to sensitize Jill to the types of cognitions that she was having about current day events and to appraisals that she had about the explosion. For example, one of the thoughts she recorded related to the explosion was, “I should have had them wait and not had them go on. ” She recorded her related feeling to be guilt. Jill’s therapist used this worksheet as a starting point for engaging in Socratic dialogue, as shown in the following example:

” She recorded her related feeling to be guilt. Jill’s therapist used this worksheet as a starting point for engaging in Socratic dialogue, as shown in the following example:

Therapist: Jill, do you mind if I ask you a few questions about this thought that you noticed, “I should have had them wait and not had them go on?”

Client: Sure.

Therapist: Can you tell me what the protocol tells you to do in a situation in which a truck breaks down during a convoy?

Client: You want to get the truck repaired as soon as possible, because the point of a convoy is to keep the trucks moving so that you aren’t sitting ducks.

Therapist: The truck that broke down was the lead truck that you were on. What is the protocol in that case?

Client: The protocol says to wave the other trucks through and keep them moving so that you don’t have multiple trucks just sitting there together more vulnerable.

Therapist: Okay. That’s helpful for me to understand. In light of the protocol you just described and the reasons for it, why do you think you should have had the second truck wait and not had them go on?

Client: If I hadn’t have waved them through and told them to carry on, this wouldn’t have happened. It is my fault that they died. (Begins to cry)

Therapist: (Pause) It is certainly sad that they died. (Pause) However, I want us to think through the idea that you should have had them wait and not had them go on, and consequently that it was your fault. (Pause) If you think back about what you knew at the time — not what you know now 5 years after the outcome — did you see anything that looked like a possible explosive device when you were scanning the road as the original lead truck?

Client: No. Prior to the truck breaking down, there was nothing that we noticed. It was an area of Iraq that could be dangerous, but there hadn’t been much insurgent activity in the days and weeks prior to it happening.

Therapist: Okay. So, prior to the explosion, you hadn’t seen anything suspicious.

Client: No.

Therapist: When the second truck took over as the lead truck, what was their responsibility and what was your responsibility at that point?

Client: The next truck that Mike and my other friends were on essentially became the lead truck, and I was responsible for trying to get my truck moving again so that we weren’t in danger.

Therapist: Okay. In that scenario then, would it be Mike and the others’ jobs to be scanning the environment ahead for potential dangers?

Client: Yes, but I should have been able to see and warn them.

Therapist: Before we determine that, how far ahead of you were Mike and the others when the explosion occurred?

Client: Oh (pause), probably 200 yards?

Therapist: 200 yards—that’s two football fields’ worth of distance, right?

Client: Right.

Therapist: You’ll have to educate me. Are there explosive devices that you wouldn’t be able to detect 200 yards ahead?

Client: Absolutely.

Therapist: How about explosive devices that you might not see 10 yards ahead?

Client: Sure. If they are really good, you wouldn’t see them at all.

Therapist: So, in light of the facts that you didn’t see anything at the time when you waved them through at 200 yards behind and that they obviously didn’t see anything 10 yards ahead before they hit the explosion, and that protocol would call for you preventing another danger of being sitting ducks, help me understand why you wouldn’t have waved them through at that time? Again, based on what you knew at the time?

Client: (Quietly) I hadn’t thought about the fact that Mike and the others obviously didn’t see the device at 10 yards, as you say, or they would have probably done something else. (Pause) Also, when you say that we were trying to prevent another danger at the time of being “sitting ducks,” it makes me feel better about waving them through.

(Pause) Also, when you say that we were trying to prevent another danger at the time of being “sitting ducks,” it makes me feel better about waving them through.

Therapist: Can you describe the type of emotion you have when you say, “It makes me feel better?”

Client: I guess I feel less guilty.

Therapist: That makes sense to me. As we go back and more accurately see the reality of what was really going on at the time of this explosion, it is important to notice that it makes you feel better emotionally. (Pause) In fact, I was wondering if you had ever considered that, in this situation, you actually did exactly what you were supposed to do and that something worse could have happened had you chosen to make them wait?

Client: No. I haven’t thought about that.

Therapist: Obviously this was an area that insurgents were active in if they were planting explosives. Is it possible that it could have gone down worse had you chosen not to follow protocol and send them through?

Client: Hmmm. I hadn’t thought about that either.

I hadn’t thought about that either.

Therapist: That’s okay. Many people don’t think through what could have happened if they had chosen an alternative course of action at the time or they assume that there would have only been positive outcomes if they had done something different. I call it “happily ever after” thinking — assuming that a different action would have resulted in a positive outcome. (Pause) When you think, “I did a good job following protocol in a stressful situation that may have prevented more harm from happening,” how does that make you feel?

Client: It definitely makes me feel less guilty.

Therapist: I’m wondering if there is any pride that you might feel?

Client: Hmmm...I don’t know if I can go that far.

Therapist: What do you mean?

Client: It seems wrong to feel pride when my friends died.

Therapist: Is it possible to feel both pride and sadness in this situation? (Pause) Do you think Mike would hold it against you for feeling pride, as well as sadness for his and others’ losses?

Client: Mike wouldn’t hold it against me. In fact, he’d probably reassure me that I did a good job.

In fact, he’d probably reassure me that I did a good job.

Therapist: (Pause) That seems really important for you to remember. It may be helpful to remind yourself of what you have discovered today, because you have some habits in thinking about this event in a particular way. We are also going to be doing some practice assignments that will help to walk you through your thoughts about what happened during this event, help you to remember what you knew at the time, and remind you how different thoughts can result in different feelings about what happened.

Client: I actually feel a bit better after this conversation.

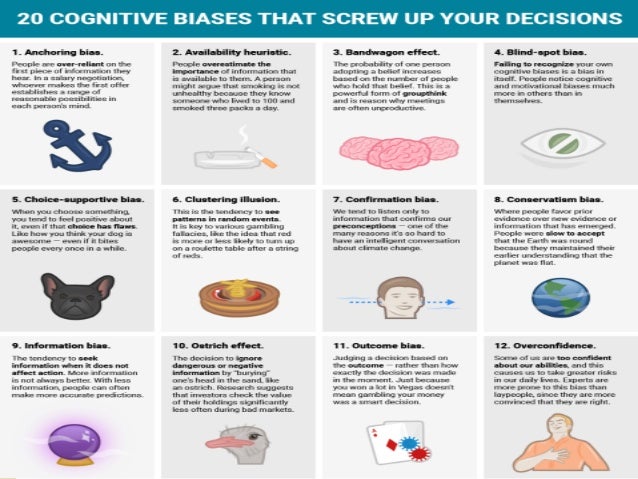

Another thought that Jill described in relation to the traumatic event was, “I should have seen the explosion was going to happen to prevent my friends from dying.” Her related feelings were guilt and self-directed anger. The therapist used this thought to introduce the cognitive intervention of "challenging thoughts" and provided a worksheet for practice. The therapist first provided education about the different types of thinking errors, including habitual thinking, all-or-none thinking, taking things out of context, overestimating probabilities, and emotional reasoning, as well as discussing other important factors, such as gathering evidence for and against the thought, evaluating the source of the information, and focusing on irrelevant factors.

The therapist first provided education about the different types of thinking errors, including habitual thinking, all-or-none thinking, taking things out of context, overestimating probabilities, and emotional reasoning, as well as discussing other important factors, such as gathering evidence for and against the thought, evaluating the source of the information, and focusing on irrelevant factors.

More specifically, Jill noted that she experienced 100 percent intensity of guilt and 75 percent intensity of anger at herself in relation to the thought "I should have seen the explosive device to prevent my friends from dying." She posed several challenging questions, including the notion that improvised explosive devices are meant to be concealed, that she is the source of the information (because others don't blame her), and that her feelings are not based on facts (i.e., she feels guilt and therefore must be guilty). She came up with the alternative thought, "The best explosive devices aren't seen and Mike (driver of the second truck) was a good soldier. If he saw something he would stopped or tried to evade it," which she rated as 90 percent confidence in believing. She consequently believed her original thought 10 percent, and re-rated her emotions as only 10 percent guilt and 5 percent anger at self.

If he saw something he would stopped or tried to evade it," which she rated as 90 percent confidence in believing. She consequently believed her original thought 10 percent, and re-rated her emotions as only 10 percent guilt and 5 percent anger at self.

Reprinted with Permission

Treating PTSD with cognitive-behavioral therapies: Interventions that work

This case example is reprinted with permission from:

Monson, C. M. & Shnaider, P. (2014). Treating PTSD with cognitive-behavioral therapies: Interventions that work. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Updated July 31, 2017

Date created: June 2017

What is cognitive behavioral therapy and how quickly it helps

March 28LikbezZdorovye

A simple question "Why?" can sort everything out.

Share

0What is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

In essence, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a way to change the way you think about life and yourself, based on two important steps:

- ), where negative thoughts, experiences, habits come from. Assess how they affect your life. Find those logical errors, cognitive distortions that make you worry. Ask yourself, “Why do I choose suffering over joy?”

- Change behavior to eliminate negative experiences by focusing on positive ones.

Personal life problems, social anxiety, chronic stress, eating disorders, psychological complexes that interfere with life - all of these can be dealt with with the help of cognitive behavioral therapy.

Keep in mind that CBT is not a magic pill. It will not save you from the existing objective problem. For example, if you suffer from the fact that your nose is too big, then it will remain the same. If you're going crazy over a divorce, your partner won't come running back with an apology. If you have a major anxiety disorder or clinical depression, psychotherapy is not a substitute for medication.

If you have a major anxiety disorder or clinical depression, psychotherapy is not a substitute for medication.

But CBT can teach you to be more accepting of problems or even turn them to your advantage. So, the same large nose can be a cause of suffering or become a highlight of appearance.

How Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Works

The basic idea of this type of psychotherapy is as follows. Your psychological state does not depend on the stressful situation as such, but on how you feel about it. The therapist will teach you to distinguish between different types of emotions, understand how your mind switches between them, and focus on the positive ones.

Here is a simple example: you are invited to a party. On this occasion, you may have such thoughts and feelings:

- “Sounds tempting! My friends will be there, and I will also be able to meet new interesting people.” Experience: anticipatory, happy, excited.

- “Parties are still not my thing.

Today, a new episode of my favorite series is coming out, I’d better stay at home, I don’t want to miss it. ” Experience: neutral.

Today, a new episode of my favorite series is coming out, I’d better stay at home, I don’t want to miss it. ” Experience: neutral. - “I never know what to do or what to say at these events. They will make me make a toast again, I will make a fool of myself, and they will laugh at me again. Experience: anxious, negative.

Bottom line: the same event can lead to completely different emotions. Which one to choose is up to you. You must make the selection process conscious. Like in a store: you are offered emotions, they cost the same - which one will you take?

To help you feel like a rational "emotion buyer", the therapist will do the following.

Will teach you to detect negative thoughts

That is, to catch what exactly you are thinking about when you start to feel anxiety. For example, the thesis “I will be laughed at” is negative.

Will help evaluate and challenge the negative

To evaluate means to ask questions: “Is the bad thing that scares me really going to happen? And if it does, will it really be catastrophic? Maybe it's not so scary?

Learn to replace negative thoughts with realistic ones

After you have identified and analyzed the disturbing thoughts, they will need to be replaced with more rational and realistic statements. For example: “Who will make me make a toast? I don’t drink at all and don’t plan to raise a glass.”

For example: “Who will make me make a toast? I don’t drink at all and don’t plan to raise a glass.”

How quickly CBT can work

Understanding why certain situations make you nervous can take time. And it will also be needed to teach your brain to choose the right ones from the “range” of emotions - calm and joyful.

It takes on average 5 to 20 psychotherapy sessions to understand and change behavior.

However, the duration of work with a psychotherapist is an individual matter. If your psychological problems are small, two or three meetings with a doctor may be enough. And someone will have to visit a specialist for years. It is impossible to predict the timing in advance. But, as experts note, on average, cognitive behavioral therapy leads to noticeable results faster than other types of intervention.

CBT has another bonus: meetings with a psychotherapist can be held online, and they will be no less effective than in person.

Read also 😱😢🙂

- 14 Early Symptoms of Bipolar Disorder You Shouldn't Ignore

- 9symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder that should not be ignored

- When passive aggression becomes a personality disorder and what to do about it

- How to recognize alcoholism, depression and other mental disorders

- How to take care of loved ones with mental disorders

Cognitive behavioral therapy - effective techniques

- Material Information

- Therapy

- Views: 1

- Previous article Specificity of psychotherapy

- Next article Art Therapy

Set font

- Size

- Style

- Reading mode

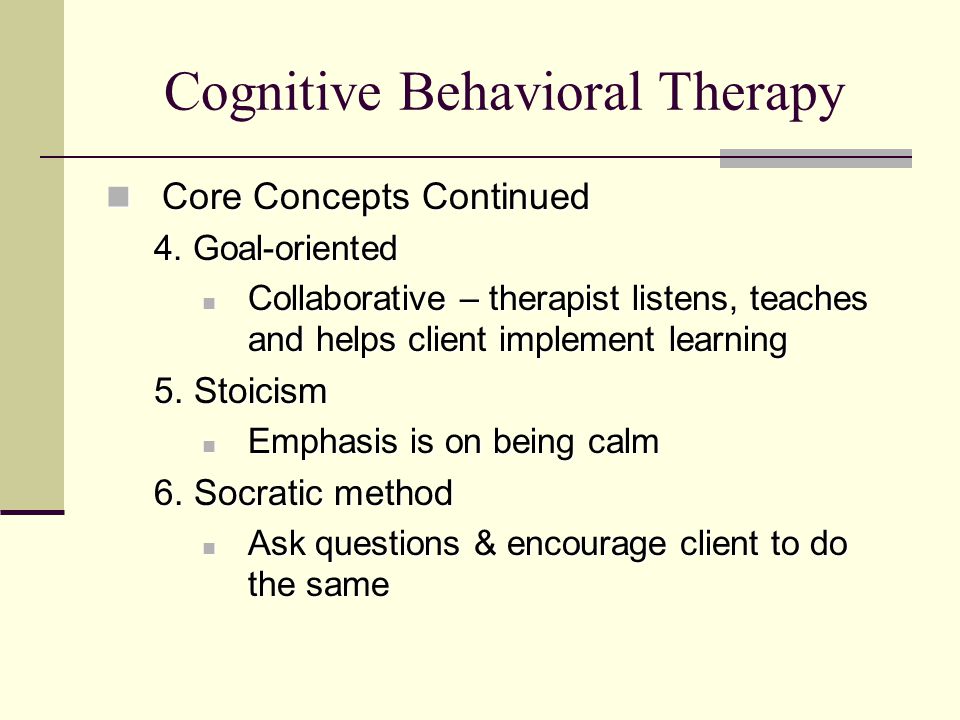

The foundation of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) was laid by the eminent psychologist Albert Ellis and psychotherapist Aaron Beck.

Originating in the sixties of the last century, this technique is recognized in the academic community as one of the most effective methods of psychotherapeutic treatment. Cognitive behavioral therapy is a universal method of helping people suffering from various neurotic and mental disorders.

The authoritativeness of this concept is added by the dominant principle of the methodology - the unconditional acceptance of personality traits, a positive attitude towards each person while maintaining healthy criticism of the negative actions of the subject.

Methods of cognitive-behavioral therapy helped thousands of people who suffered from various complexes, depressive states, irrational fears. The popularity of this technique explains the combination of obvious advantages of CBT:

- a guarantee of achieving high results and a complete solution to the existing problem;

- long-term, often life-long persistence of the effect obtained;

- short course of therapy;

- comprehensibility of exercises for an ordinary citizen;

- simplicity of tasks;

- the ability to perform the exercises recommended by the doctor on your own in the comfort of your own home;

- a wide range of applications of techniques, the ability to use to overcome various psychological problems;

- no side effects;

- atraumatic and safe;

- the use of hidden resources of the body to solve the problem.

Cognitive behavioral therapy has shown good results in the treatment of various neurotic and psychotic disorders. CBT methods are used in the treatment of affective and anxiety disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder, problems in the intimate sphere, and eating disorders. CBT techniques bring excellent results in the treatment of alcoholism, drug addiction, gambling, and psychological addictions.

General information

One of the features of cognitive-behavioral therapy is the division and systematization of all emotions of a person into two broad groups:

- productive, also called rational or functional;

- unproductive, called irrational or dysfunctional.

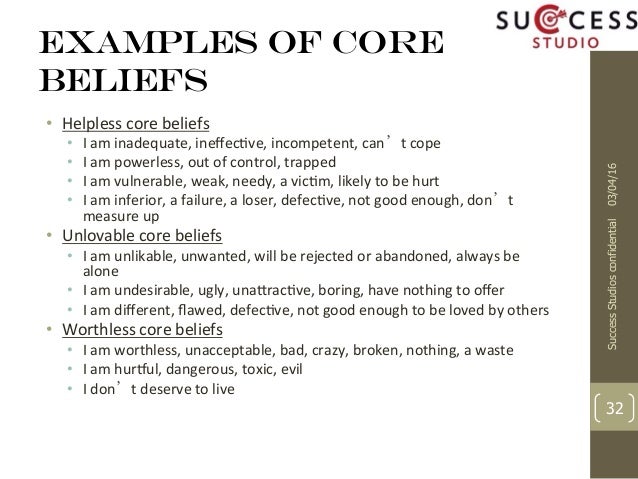

The group of unproductive emotions includes destructive experiences of an individual, which, according to the concept of CBT, are the result of irrational (illogical) beliefs and beliefs of a person - “irrational beliefs”. According to supporters of cognitive-behavioral therapy, all unproductive emotions and the dysfunctional model of personality behavior associated with it are not a reflection or result of the subject's personal experience. All irrational components of thinking and the non-constructive behavior associated with them are the result of a person's incorrect, distorted interpretation of their real experience. According to the authors of the methodology, the real culprit of all psycho-emotional disorders is the distorted and destructive belief system present in the individual, which was formed as a result of the wrong beliefs of the individual.

All irrational components of thinking and the non-constructive behavior associated with them are the result of a person's incorrect, distorted interpretation of their real experience. According to the authors of the methodology, the real culprit of all psycho-emotional disorders is the distorted and destructive belief system present in the individual, which was formed as a result of the wrong beliefs of the individual.

These ideas form the foundation of cognitive-behavioral therapy, the main concept of which is the following: the emotions, feelings and behavior of the subject are not determined by the situation in which he is, but by how he perceives the current situation. From these considerations comes the dominant strategy of CBT - to identify and identify dysfunctional experiences and stereotypes, then replace them with rational, useful, realistic feelings, taking full control of your train of thought.

By changing the personal attitude to some factor or phenomenon, replacing a rigid, rigid, non-constructive life strategy with flexible thinking, a person will acquire an effective worldview.

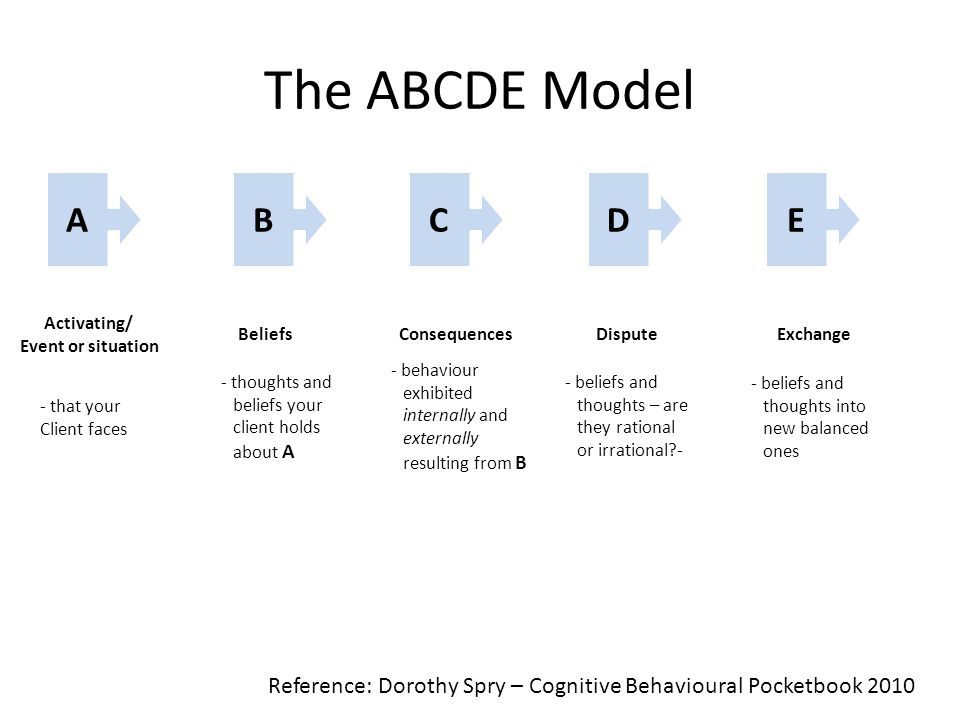

The functional emotions that have arisen will improve the psycho-emotional state of the individual and ensure excellent well-being under any life circumstances. On this basis, a conceptual model of cognitive-behavioral therapy was formulated , presented in an easy-to-understand ABC formula, where:

- A (activating event) - a certain event occurring in reality, which is a stimulus for the subject;

- B (belief) - the system of personal beliefs of an individual, a cognitive structure that reflects the process of a person's perception of an event in the form of emerging thoughts, formed ideas, formed beliefs;

- C (emotional consequences) - final results, emotional and behavioral consequences.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is focused on the identification and subsequent transformation of distorted components of thinking, which ensures the formation of a functional strategy for the behavior of the individual.

Treatment process

The treatment process using cognitive behavioral therapy techniques is a short course of 10 to 20 sessions. Most patients visit a therapist no more than twice a week. After a face-to-face meeting, clients are given a small “homework assignment”, which includes the performance of specially selected exercises and additional acquaintance with educational literature.

CBT treatment involves the use of two groups of techniques: behavioral and cognitive.

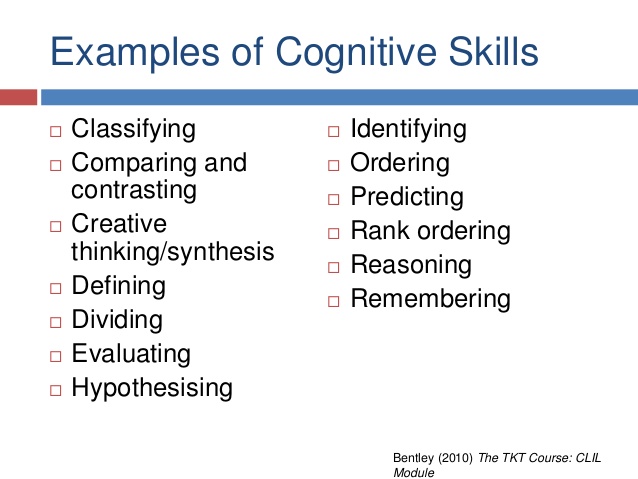

Let's consider cognitive techniques in more detail. They are aimed at detecting and correcting dysfunctional thoughts, beliefs, ideas. It should be noted that irrational emotions impede the normal functioning of a person, change a person’s thinking, force them to make and follow illogical decisions. Going off scale in amplitude, affective unproductive feelings lead to the fact that the individual sees reality in a distorted light. Dysfunctional emotions deprive a person of control over himself, force him to commit reckless acts.

Cognitive techniques are conditionally divided into several groups.

Group one

The purpose of the techniques of the first group is to track and become aware of one's own thoughts. For this, the following methods are most often used.

Recordings of one's own thoughts

The patient receives the task: to state on a piece of paper the thoughts that arise before and during the performance of any action. In this case, it is necessary to fix thoughts strictly in the order of their priority. This step will indicate the significance of certain motives of a person when making a decision.

Keeping a diary of thoughts

The client is advised to briefly, concisely and accurately record all thoughts that arise in a diary for several days. This action will allow you to find out what a person thinks about most often, how much time he spends thinking about these thoughts, how much he is disturbed by certain ideas.

Distance from non-functional thoughts

The essence of the exercise is that a person must develop an objective attitude towards his own thoughts. In order to become an impartial "observer", he needs to move away from emerging ideas. Detachment from one's own thoughts has three components:

- awareness and acceptance of the fact that a non-constructive thought arises automatically, an understanding that the overcoming idea was formed earlier under certain circumstances, or that it is not its own product of thinking, but is imposed from outside by extraneous subjects;

- awareness and acceptance that stereotypical thoughts are non-functional and interfere with normal adaptation to existing conditions;

- doubt about the truth of the emerging non-adaptive idea, since such a stereotypical construct contradicts the existing situation and does not correspond in its essence to the emerging requirements of reality.

Second group

The task of the technicians from the second group is to challenge existing non-functional thoughts. To do this, the patient is asked to perform the following exercises.

To do this, the patient is asked to perform the following exercises.

Examining arguments for and against stereotypical thoughts

A person examines his own maladaptive thought and writes down the arguments for and against. The patient is then instructed to reread their notes daily. With regular exercise in the mind of a person, over time, the “correct” arguments will be firmly fixed, and the “wrong” ones will be eliminated from thinking.

Weighing advantages and disadvantages

This exercise is not about analyzing your own non-constructive thoughts, but about studying existing solutions. For example, a woman makes a comparison of what is more important for her: to maintain her own safety by not coming into contact with persons of the opposite sex, or to allow a share of risk in her life in order to eventually create a strong family.

Experiment

This exercise provides that a person experimentally, on personal experience, comprehends the result of demonstrating one or another emotion. For example, if the subject does not know how society reacts to the manifestation of his anger, he is allowed to express his emotion in full force, directing it to the therapist.

For example, if the subject does not know how society reacts to the manifestation of his anger, he is allowed to express his emotion in full force, directing it to the therapist.

Return to the past

The essence of this step is a frank conversation with impartial witnesses of past events that left a mark on the human psyche. This technique is especially effective in disorders of the mental sphere, in which memories are distorted. This exercise is relevant for those who have delusions that have arisen as a result of an incorrect interpretation of the motives that move other people.

Use of authoritative sources of information

This step involves giving the patient arguments drawn from scientific literature, official statistics, personal experience of the doctor. For example, if a patient is afraid of flying, the therapist points him to objective international reports, according to which the number of accidents when using airplanes is much lower compared to disasters that occur on other modes of transport.

Socratic method (Socratic dialogue)

The doctor's task is to identify and point out to the client logical errors and obvious contradictions in his reasoning. For example, if the patient is convinced that he is destined to die from a spider bite, but at the same time declares that he has already been bitten by this insect before, the doctor points out a contradiction between anticipation and the real facts of personal history.

Change of mind - reassessment of facts

The purpose of this exercise is to change a person's current view of an existing situation by testing whether alternative causes of the same event would have the same effect. For example, the client is invited to reflect and discuss whether this or that person could have done the same to him if she had been guided by other motives.

Decreasing the significance of results - decatastrophe

This technique involves the development of a non-adaptive thought of the patient to a global scale for the subsequent devaluation of its consequences. For example, to a person who is terrified of leaving his own home, the doctor asks questions: “In your opinion, what will happen to you if you go outside?”, “How much and for how long will negative feelings overcome you?”, “What will happen next? Are you going to have a seizure? Are you dying? Will people die? The planet will end its existence? A person understands that his fears in a global sense are not worth attention. Awareness of the temporal and spatial framework helps to eliminate the fear of the imagined consequences of a disturbing event.

For example, to a person who is terrified of leaving his own home, the doctor asks questions: “In your opinion, what will happen to you if you go outside?”, “How much and for how long will negative feelings overcome you?”, “What will happen next? Are you going to have a seizure? Are you dying? Will people die? The planet will end its existence? A person understands that his fears in a global sense are not worth attention. Awareness of the temporal and spatial framework helps to eliminate the fear of the imagined consequences of a disturbing event.

Softening the intensity of emotions

The essence of this technique is to conduct an emotional reassessment of a traumatic event. For example, the injured person is asked to summarize the situation by saying to herself the following: “It is very unfortunate that such a fact took place in my life. However, I will not allow

this event will control my present and ruin my future. I'm leaving the trauma in the past. " That is, the destructive emotions that arise in a person lose their power of affect: resentment, anger and hatred are transformed into softer and more functional experiences.

" That is, the destructive emotions that arise in a person lose their power of affect: resentment, anger and hatred are transformed into softer and more functional experiences.

Role change

This technique consists of an exchange of roles between the doctor and the client. The task of the patient is to convince the therapist that his thoughts and beliefs are maladaptive. Thus, the patient himself is convinced of the dysfunctionality of his judgments.

Postponing ideas

This exercise is suitable for those patients who cannot give up their impossible dreams, unrealistic desires and unrealistic goals, but thinking about them makes him uncomfortable. The client is invited to postpone the implementation of his ideas for a long time, while specifying a specific date for their implementation, for example, the occurrence of a certain event. The expectation of this event eliminates psychological discomfort, thereby making a person's dream more achievable.

Drawing up a plan of action for the future

The client, together with the doctor, develops an adequate realistic program of actions for the future, which specifies specific conditions, defines the actions of a person, sets step-by-step deadlines for completing tasks. For example, the therapist and the patient agree that in the event of a critical situation, the client will follow a certain sequence of actions. And until the onset of a catastrophic event, he will not exhaust himself with disturbing experiences at all.

Group three

The third group of techniques is focused on activating the sphere of the individual's imagination. It has been established that the dominant position in thinking of anxious people is not occupied by “automatic” thoughts at all, but by obsessive frightening images and exhausting destructive ideas. Based on this, therapists have developed special techniques that act on the correction of the area of imagination.

Termination method

When a client has an obsessive negative image, he is advised to utter a conditional laconic command in a loud and firm voice, for example: “Stop!”. Such an indication terminates the action of the negative image.

Repetition method

This technique involves the patient repeatedly repeating the settings that are characteristic of a productive way of thinking. Thus, over time, the formed negative stereotype is eliminated.

Use of metaphors

To activate the sphere of the patient's imagination, the doctor uses appropriate metaphorical statements, instructive parables, quotations from poetry. This approach makes the explanation more colorful and understandable.

Image modification

The method of modifying imagination involves the active work of the client, aimed at gradually replacing destructive images with ideas of a neutral color, and then with positive constructs.

Positive imagination

This technique involves replacing a negative image with positive ideas, which has a pronounced relaxing effect.

Constructive imagination

The desensitization technique consists in the fact that a person ranks the probability of an expected catastrophic situation, that is, he establishes and orders the expected future events in order of importance. This step leads to the fact that the negative forecast loses its global significance and is no longer perceived as inevitable. For example, a patient is asked to rank the probability of death when meeting with an object of fear.

Fourth group

Techniques from this group are aimed at increasing the effectiveness of the treatment process and minimizing the resistance of the client.

Purposeful repetition

The essence of this technique is persistent repeated testing of various positive instructions in personal practice.