Nicotine causes depression

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.

Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.

For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

The Association of Cigarette Smoking With Depression and Anxiety: A Systematic Review

1. Royal College of Physicians RCoP. Smoking and Mental Health. London: RCP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

2. Farrell M, Howes S, Taylor C, et al. Substance misuse and psychiatric comorbidity: An overview of the OPCS National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Addictive Behav. 1998;23(6):909–918. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00075-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Meltzer H, Gill B, Hinds K, Petticrew M. OPCS Surveys of Psychiatric Morbidity in Great Britain,Report 6: Economic Activity and Social Functioning of Residents With Psychiatric Disorders. London: HMSO; 1996. doi:10.5255/UKDA-SN-3585-1. [Google Scholar]

4. McManus S, Howard M, Campion J. Cigarette Smoking and Mental Health in England: Data From the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2007; 2010. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

5. Chaiton MO, Cohen JE, O’Loughlin J, Rehm J. A systematic review of longitudinal studies on the association between depression and smoking in adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:356. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-356. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Cigarette smoking and depression: tests of causal linkages using a longitudinal birth cohort. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196:440–446. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.065912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Taylor G, McNeill A, et al. Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g1151. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Markou A, Kosten TR, Koob GF. Neurobiological similarities in depression and drug dependence: a self-medication hypothesis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;18:135–174. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X (97)00113-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Rose JE, Behm FM, Ramsey C, Ritchie JC. , Jr Platelet monoamine oxidase, smoking cessation, and tobacco withdrawal symptoms. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3:383–390. doi:10.1080/14622200110087277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

, Jr Platelet monoamine oxidase, smoking cessation, and tobacco withdrawal symptoms. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3:383–390. doi:10.1080/14622200110087277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Munafò MR, Araya R. Cigarette smoking and depression: a question of causation. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196:425–426. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Kendler KS, Neale MC, MacLean CJ, Heath AC, Eaves LJ, Kessler RC. Smoking and major depression. A causal analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:36–43. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820130038007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed., Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

13. Fagerstrom KO, Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT. Nicotine addiction and its assessment. Ear Nose Throat J. 1990;69:763–765. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2276350 Accessed September 15, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Carvajal SC, Granillo TM. A prospective test of distal and proximal determinants of smoking initiation in early adolescents. Addict Behav. 2006;31:649–660. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

A prospective test of distal and proximal determinants of smoking initiation in early adolescents. Addict Behav. 2006;31:649–660. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Breslau N, Peterson EL, Schultz LR, Chilcoat HD, Andreski P. Major depression and stages of smoking. A longitudinal investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:161–166. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.55.2.161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Chen J, Li X, Zhang J, et al. The Beijing Twin Study (BeTwiSt): a longitudinal study of child and adolescent development. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2013;16:91–97. doi:10.1017/thg.2012.115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Fuemmeler B, Lee CT, Ranby KW, et al. Individual- and community-level correlates of cigarette-smoking trajectories from age 13 to 32 in a U.S. population-based sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:301–308. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction. 2004;99:1548–1559. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Addiction. 2004;99:1548–1559. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Naicker K, Galambos NL, Zeng Y, Senthilselvan A, Colman I. Social, demographic, and health outcomes in the 10 years following adolescent depression. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:533–538. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Weiss JW, Mouttapa M, Cen S, Johnson CA, Unger J. Longitudinal effects of hostility, depression, and bullying on adolescent smoking initiation. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48:591–596. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Brown RA, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Wagner EF. Cigarette smoking, major depression, and other psychiatric disorders among adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:1602–1610. doi:10.1097/00004583-199612000-00011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Holahan CK, Holahan CJ, Powers DA, Hayes RB, Marti CN, Ockene JK. Depressive symptoms and smoking in middle-aged and older women. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:722–731. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr066. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:722–731. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr066. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Killen JD, Robinson TN, Haydel KF, et al. Prospective study of risk factors for the initiation of cigarette smoking. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:1011–1016. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.65.6.1011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Senol Y, Donmez L, Turkay M, Aktekin M. The incidence of smoking and risk factors for smoking initiation in medical faculty students: cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:128. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Goodman E, Capitman J. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among teens. Pediatrics. 2000;106:748–755. doi:10.1542/peds.106.4.748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. O’Loughlin J, Karp I, Koulis T, Paradis G, DiFranza J. Determinants of first puff and daily cigarette smoking in adolescents. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(5):585–597. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Wiesner M, Ittel A. Relations of pubertal timing and depressive symptoms to substance use in early adolescence. J Early Adolesc.2002;22(1):5–23. doi: 10.1177/0272431602022001001. [Google Scholar]

Wiesner M, Ittel A. Relations of pubertal timing and depressive symptoms to substance use in early adolescence. J Early Adolesc.2002;22(1):5–23. doi: 10.1177/0272431602022001001. [Google Scholar]

28. Cuijpers P, Smit F, Ten Have M, de Graaf R. Smoking is associated with first-ever incidence of mental disorders: a prospective population-based study. Addiction. 2007;102(8):1303–1309. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01885.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Swendsen J, Conway KP, Degenhardt L, et al. Mental disorders as risk factors for substance use, abuse and dependence: results from the 10-year follow-up of the National Comorbidity Survey. Addiction. 2010;105:1117–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02902.x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Marmorstein NR, White HR, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Anxiety as a predictor of age at first use of substances and progression to substance use problems among boys. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38:211–224. doi: 10. 1007/s10802-009-9360-y. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1007/s10802-009-9360-y. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Patton GC, Carlin JB, Coffey C, Wolfe R, Hibbert M, Bowes G. Depression, anxiety, and smoking initiation: a prospective study over 3 years. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1518–1522. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.88.10.1518. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Escobedo LG, Reddy M, Giovino GA. The relationship between depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking in US adolescents. Addiction. 1998;93:433–440. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93343311.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Fischer JA, Najman JM, Williams GM, Clavarino AM. Childhood and adolescent psychopathology and subsequent tobacco smoking in young adults: findings from an Australian birth cohort. Addiction. 2012;107:1669–1676. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03846.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Leff MK, Moolchan ET, Cookus BA, et al. Predictors of smoking initiation among at risk youth: a controlled study. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2003;13(1):59–75. doi: 10.1300/J029v13n01_04. [Google Scholar]

2003;13(1):59–75. doi: 10.1300/J029v13n01_04. [Google Scholar]

35. Pedersen W, von Soest T. Smoking, nicotine dependence and mental health among young adults: a 13-year population-based longitudinal study. Addiction. 2009;104:129–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02395.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Hayatbakhsh R, Mamun AA, Williams GM, O’Callaghan MJ, Najman JM. Early childhood predictors of early onset of smoking: a birth prospective study. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2513–2519. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.05.009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Mendel JR, Berg CJ, Windle RC, Windle M. Predicting young adulthood smoking among adolescent smokers and nonsmokers. Am J Health Behav. 2012;36:542–554. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.36.4.11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Braithwaite RS, Fang Y, Tate J, et al. Do alcohol misuse, smoking, and depression vary concordantly or sequentially? A longitudinal study of HIV-infected and matched uninfected veterans in care. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:566–572. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1117-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2016;20:566–572. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1117-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Audrain-McGovern J, Lerman C, Wileyto EP, Rodriguez D, Shields PG. Interacting effects of genetic predisposition and depression on adolescent smoking progression. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1224–1230. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Rodgers K, Cuevas J. Declining alternative reinforcers link depression to young adult smoking. Addiction. 2011;106:178–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03113.x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Black DS, Sussman S, Johnson CA, Milam J. Testing the indirect effect of trait mindfulness on adolescent cigarette smoking through negative affect and perceived stress mediators. J Subst Use. 2012;17(5–6):417–429. doi: 10.3109/14659891.2011.587092. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Bomba J, Modrzejewska R, Pilecki M, Ślosarczyk M. Adolescent depression as a risk factor for the development of mental disorders. A 15-year prospective follow-up. Arch Psychiatr Psychother.2004;6(1):5–14. http://www.archivespp.pl/uploads/APPv6n1p5Bomba.pdf Accessed September 15, 2015. [Google Scholar]

A 15-year prospective follow-up. Arch Psychiatr Psychother.2004;6(1):5–14. http://www.archivespp.pl/uploads/APPv6n1p5Bomba.pdf Accessed September 15, 2015. [Google Scholar]

43. Brook JS, Balka EB, Ning Y, Whiteman M, Finch SJ. Smoking involvement during adolescence among African Americans and Puerto Ricans: risks to psychological and physical well-being in young adulthood. Psychol Rep. 2006;99:421–438. doi: 10.2466/pr0.99.2.421-438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Brummett BH, Babyak MA, Siegler IC, Mark DB, Williams RB, Barefoot JC. Effect of smoking and sedentary behavior on the association between depressive symptoms and mortality from coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:529–532. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00719-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Carvajal SC. Global positive expectancies in adolescence and health-related behaviours: longitudinal models of latent growth and cross-lagged effects. Psychol Health. 2012;27:916–937. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.633241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Anda RF, Williamson DF, Escobedo LG, Mast EE, Giovino GA, Remington PL. Depression and the dynamics of smoking. A national perspective. JAMA. 1990;264:1541–1545. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03450120053028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Kassel JD. Adolescent smoking and depression: evidence for self-medication and peer smoking mediation. Addiction. 2009;104:1743–1756. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02617.x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Park S, Weaver TE, Romer D. Predictors of the transition from experimental to daily smoking among adolescents in the United States. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2009;14:102–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2009.00183.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Clark HK, Ringwalt CL, Shamblen SR. Predicting adolescent substance use: the effects of depressed mood and positive expectancies. Addict Behav. 2011;36:488–493. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Gritz ER, Prokhorov AV, Hudmon KS, et al. Predictors of susceptibility to smoking and ever smoking: a longitudinal study in a triethnic sample of adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res.2003;5(4):493–506. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000118568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gritz ER, Prokhorov AV, Hudmon KS, et al. Predictors of susceptibility to smoking and ever smoking: a longitudinal study in a triethnic sample of adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res.2003;5(4):493–506. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000118568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Kandel DB, Davies M. Adult sequelae of adolescent depressive symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:255–262. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030073007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Knekt P, Raitasalo R, Heliövaara M, et al. Elevated lung cancer risk among persons with depressed mood. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:1096–1103. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Leve LD, Harold GT, Van Ryzin MJ, Elam K, Chamberlain P. Girls’ tobacco and alcohol use during early adolescence: prediction from trajectories of depressive symptoms across two studies. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2012;21(3):254–272. doi: 10.1080/1067828x.2012.700853. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Miller-Johnson S, Lochman JE, Coie JD, Terry R, Hyman C. Comorbidity of conduct and depressive problems at sixth grade: substance use outcomes across adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1998;26:221–232. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9650628 Accessed September 15, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Comorbidity of conduct and depressive problems at sixth grade: substance use outcomes across adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1998;26:221–232. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9650628 Accessed September 15, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Prinstein MJ, La Greca AM. Childhood depressive symptoms and adolescent cigarette use: a six-year longitudinal study controlling for peer relations correlates. Health Psychol. 2009;28:283–291. doi: 10.1037/a0013949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Wickrama T, Wickrama KA. Heterogeneity in adolescent depressive symptom trajectories: implications for young adults’ risky lifestyle. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Needham BL. Gender differences in trajectories of depressive symptomatology and substance use during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:1166–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Coogan PF, Yu J, O’Connor GT, Brown TA, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L. Depressive symptoms and the incidence of adult-onset asthma in African American women. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:333–8.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2013.12.025. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Coogan PF, Yu J, O’Connor GT, Brown TA, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L. Depressive symptoms and the incidence of adult-onset asthma in African American women. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:333–8.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2013.12.025. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Byers AL, Vittinghoff E, Lui LY, et al. Twenty-year depressive trajectories among older women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:1073–1079. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Franko DL, Striegel-Moore RH, Bean J, et al. Psychosocial and health consequences of adolescent depression in Black and White young adult women. Health Psychol. 2005;24:586–593. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.6.586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Leiferman J. The effect of maternal depressive symptomatology on maternal behaviors associated with child health. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29:596–607. doi: 10.1177/109019802237027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Appleton KM, Woodside JV, Arveiler D, et al. Depression and mortality: artifact of measurement and analysis? J Affect Disord. 2013;151(2):632–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Depression and mortality: artifact of measurement and analysis? J Affect Disord. 2013;151(2):632–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Niemelä S, Sourander A, Pilowsky DJ, et al. Childhood antecedents of being a cigarette smoker in early adulthood. The Finnish ‘From a Boy to a Man’ Study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50:343–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01968.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Repetto PB, Caldwell CH, Zimmerman MA. A longitudinal study of the relationship between depressive symptoms and cigarette use among African American adolescents. Health Psychol. 2005;24:209–219. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Leung J, Gartner C, Hall W, Lucke J, Dobson A. A longitudinal study of the bi-directional relationship between tobacco smoking and psychological distress in a community sample of young Australian women. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1273–1282. doi: 10.1017/s0033291711002261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Fleming CB, Mason WA, Mazza JJ, Abbott RD, Catalano RF. Latent growth modeling of the relationship between depressive symptoms and substance use during adolescence. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22:186–197. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.22.2.186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fleming CB, Mason WA, Mazza JJ, Abbott RD, Catalano RF. Latent growth modeling of the relationship between depressive symptoms and substance use during adolescence. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22:186–197. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.22.2.186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Patel V, Faith MS, Rodgers K, Cuevas J. How do psychological factors influence adolescent smoking progression? The evidence for indirect effects through tobacco advertising receptivity. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1216–1225. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. van Gool CH, Kempen GI, Bosma H, van Boxtel MP, Jolles J, van Eijk JT. Associations between lifestyle and depressed mood: longitudinal results from the Maastricht Aging Study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:887–894. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2004.053199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Wang MQ, Fitzhugh EC, Turner L, Fu Q, Westerfield RC. Association of depressive symptoms and school adolescents’ smoking: a cross-lagged analysis. Psychol Rep. 1996;79:127–130. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1996.79.1.127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychol Rep. 1996;79:127–130. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1996.79.1.127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Kang E, Lee J. A longitudinal study on the causal association between smoking and depression. J Prev Med Public Health. 2010;43:193–204. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2010.43.3.193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Ferdinand RF, Blüm M, Verhulst FC. Psychopathology in adolescence predicts substance use in young adulthood. Addiction. 2001;96:861–870. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9668617.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Albers AB, Biener L. The role of smoking and rebelliousness in the development of depressive symptoms among a cohort of Massachusetts adolescents. Prev Med. 2002;34:625–631. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Batterham PJ, Christensen H, Mackinnon AJ. Modifiable risk factors predicting major depressive disorder at four year follow-up: a decision tree approach. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-244x-9–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Buckner JC, Mandell W. Risk factors for depressive symptomatology in a drug using population. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:580–585. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.5.580. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Buckner JC, Mandell W. Risk factors for depressive symptomatology in a drug using population. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:580–585. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.5.580. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Choi WS, Patten CA, Gillin JC, Kaplan RM, Pierce JP. Cigarette smoking predicts development of depressive symptoms among U.S. adolescents. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19:42–50. doi: 10.1007/BF02883426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Colman I, Naicker K, Zeng Y, Ataullahjan A, Senthilselvan A, Patten SB. Predictors of long-term prognosis of depression. CMAJ. 2011;183:1969–1976. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110676. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Costello DM, Swendsen J, Rose JS, Dierker LC. Risk and protective factors associated with trajectories of depressed mood from adolescence to early adulthood. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:173–183. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.76.2.173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. de Jonge P, Kempen GI, Sanderman R, et al. Depressive symptoms in elderly patients after a somatic illness event: prevalence, persistence, and risk factors. Psychosomatics. 2006;47:33–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.1.33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Depressive symptoms in elderly patients after a somatic illness event: prevalence, persistence, and risk factors. Psychosomatics. 2006;47:33–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.1.33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Flensborg-Madsen T, von Scholten MB, Flachs EM, Mortensen EL, Prescott E, Tolstrup JS. Tobacco smoking as a risk factor for depression. A 26-year population-based follow-up study. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.06.006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Gravely-Witte S, Stewart DE, Suskin N, Grace SL. The association among depressive symptoms, smoking status and antidepressant use in cardiac outpatients. J Behav Med. 2009;32:478–490. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9218-3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Khaled SM, Bulloch AG, Williams JV, Hill JC, Lavorato DH, Patten SB. Persistent heavy smoking as risk factor for major depression (MD) incidence–evidence from a longitudinal Canadian cohort of the National Population Health Survey. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.11.011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.11.011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Klungsøyr O, Nygård JF, Sørensen T, Sandanger I. Cigarette smoking and incidence of first depressive episode: an 11-year, population-based follow-up study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:421–432. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. Koçer O, Wachter M, Zellweger M, Piazzalonga S, Hoffmann A. Prevalence and predictors of depressive symptoms and wellbeing during and up to nine years after outpatient cardiac rehabilitation. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13242. doi: 10.4414/smw.2011.13242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84. Meng X, D’Arcy C. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on major depression incidence: a 16-year longitudinal Canadian cohort of the National Population Health Survey. J Affect Disord. 2014;158:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85. Moon SS, Mo BC, Basham R. Adolescent depression and future smoking behavior: a prospective study. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2010;27(6):405–422. doi: 10.1007/s10560-010-0212-y. [Google Scholar]

Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2010;27(6):405–422. doi: 10.1007/s10560-010-0212-y. [Google Scholar]

86. Patten SB, Wang JL, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Khaled SM, Bulloch AG. Predictors of the longitudinal course of major depression in a Canadian population sample. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55:669–676. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20964946 Accessed September 15, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Schrader G, Cheok F, Hordacre AL, Guiver N. Predictors of depression three months after cardiac hospitalization. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:514–520. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000128901.58513.db. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. Schrader G, Cheok F, Hordacre AL, Marker J. Predictors of depression 12 months after cardiac hospitalization: the Identifying Depression as a Comorbid Condition study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:1025–1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1614.2006.01927.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89. Silberg JL, Rutter M, D’Onofrio B, Eaves L. Genetic and environmental risk factors in adolescent substance use. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2003;44(5):664–676. doi: 10.1111/1469–7610.00153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2003;44(5):664–676. doi: 10.1111/1469–7610.00153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

90. Sweeting HN, West PB, Der GJ. Explanations for female excess psychosomatic symptoms in adolescence: evidence from a school-based cohort in the West of Scotland. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:298. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91. Green BH, Copeland JR, Dewey ME, et al. Risk factors for depression in elderly people: a prospective study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992;86:213–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb03254.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Rodriguez D, Moss HB, Audrain-McGovern J. Developmental heterogeneity in adolescent depressive symptoms: associations with smoking behavior. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:200–210. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000156929.83810.01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93. Brook JS, Schuster E, Zhang C. Cigarette smoking and depressive symptoms: a longitudinal study of adolescents and young adults. Psychol Rep. 2004;95:159–166. doi: 10.2466/pr0.95.1.159-166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2004;95:159–166. doi: 10.2466/pr0.95.1.159-166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

94. Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Initiation and maintenance of tobacco smoking: changing personality correlates in adolescence and young adulthood. J Appl Soc Psychol.1996;26(2):160–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1559–1816.1996.tb01844.x. [Google Scholar]

95. Clyde M, Smith KJ, Gariepy G, Schmitz N. Assessing the longitudinal associations and stability of smoking and depression syndrome over a 4-year period in a community sample with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes. 2014;7(1):95–101. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96. Dugan SA, Bromberger JT, Segawa E, Avery E, Sternfeld B. Association between physical activity and depressive symptoms: midlife women in SWAN. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47:335–342. doi: 10.1249/mss.0000000000000407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. Duncan B, Rees DI. Effect of smoking on depressive symptomatology: a reexamination of data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:461–470. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:461–470. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98. Pasco JA, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, et al. Tobacco smoking as a risk factor for major depressive disorder: population-based study. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193:322–326. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.046706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

99. Tanaka H, Sasazawa Y, Suzuki S, Nakazawa M, Koyama H. Health status and lifestyle factors as predictors of depression in middle-aged and elderly Japanese adults: a seven-year follow-up of the Komo-Ise cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-244x-11–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

100. Almeida OP, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB, Golledge J, McCaul K, Flicker L. A risk table to assist health practitioners assess and prevent the onset of depression in later life. Prev Med. 2013;57:878–882. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.09.021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

101. Korhonen T, Broms U, Varjonen J, et al. Smoking behaviour as a predictor of depression among Finnish men and women: a prospective cohort study of adult twins. Psychol Med. 2007;37:705–715. doi: 10.1017/s0033291706009639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychol Med. 2007;37:705–715. doi: 10.1017/s0033291706009639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

102. Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Lee IM, Leung R. Physical activity and personal characteristics associated with depression and suicide in American college men. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1994;377:16–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb05796.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

103. Gage SH, Hickman M, Heron J, et al. Associations of cannabis and cigarette use with depression and anxiety at age 18: findings from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122896. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

104. Aneshensel CS, Huba GJ. Depression, alcohol use, and smoking over one year: a four-wave longitudinal causal model. J Abnorm Psychol. 1983;92:134–150. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.92.2.134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

105. Julian LJ, Tonner C, Yelin E, et al. Cardiovascular and disease-related predictors of depression in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:542–549.doi: 10.1002/acr.20426. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:542–549.doi: 10.1002/acr.20426. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

106. Munafò MR, Hitsman B, Rende R, Metcalfe C, Niaura R. Effects of progression to cigarette smoking on depressed mood in adolescents: evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Addiction. 2008;103:162–171.doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02052.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

107. Strong C, Juon HS, Ensminger ME. Long-term effects of adolescent smoking on depression and socioeconomic status in adulthood in an urban African American cohort. J Urban Health. 2014;91:526–540. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9849-0. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

108. Takeuchi T, Nakao M, Yano E. Relationship between smoking and major depression in a Japanese workplace. J Occup Health. 2004;46:489–492. doi: 10.1539/joh.46.489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

109. Weyerer S, Eifflaender-Gorfer S, Wiese B, et al. Incidence and predictors of depression in non-demented primary care attenders aged 75 years and older: results from a 3-year follow-up study. Age Ageing. 2013;42:173–180. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Age Ageing. 2013;42:173–180. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

110. Clark C, Haines MM, Head J, et al. Psychological symptoms and physical health and health behaviours in adolescents: a prospective 2-year study in East London. Addiction. 2007;102:126–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01621.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

111. Anstey KJ, von Sanden C, Sargent-Cox K, Luszcz MA. Prevalence and risk factors for depression in a longitudinal, population-based study including individuals in the community and residential care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:497–505. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31802e21d8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

112. Moylan S, Gustavson K, Karevold E, et al. The impact of smoking in adolescence on early adult anxiety symptoms and the relationship between infant vulnerability factors for anxiety and early adult anxiety symptoms: the TOPP Study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

113. Boyes AW, Girgis A, D’Este CA, Zucca AC, Lecathelinais C. Prevalence and predictors of the short-term trajectory of anxiety and depression in the first year after a cancer diagnosis: a population-based longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2013. doi: 10.1200/jco.2012.44.7540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boyes AW, Girgis A, D’Este CA, Zucca AC, Lecathelinais C. Prevalence and predictors of the short-term trajectory of anxiety and depression in the first year after a cancer diagnosis: a population-based longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2013. doi: 10.1200/jco.2012.44.7540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

114. Patel V, Kirkwood BR, Pednekar S, Weiss H, Mabey D. Risk factors for common mental disorders in women - Population-based longitudinal study. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:547–555. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.022558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

115. Wagena EJ, van Amelsvoort LG, Kant I, Wouters EF. Chronic bronchitis, cigarette smoking, and the subsequent onset of depression and anxiety: results from a prospective population-based cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:656–660. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000171197.29484.6b. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

116. Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Structural models of the comorbidity of internalizing disorders and substance use disorders in a longitudinal birth cohort. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46:933–942. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0268-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46:933–942. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0268-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

117. Bjørngaard JH, Gunnell D, Elvestad MB, et al. The causal role of smoking in anxiety and depression: a Mendelian randomization analysis of the HUNT study. Psychol Med. 2013;43:711–719. doi: 10.1017/s0033291712001274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

118. Clark DB, Cornelius J. Childhood psychopathology and adolescent cigarette smoking: a prospective survival analysis in children at high risk for substance use disorders. Addict Behav. 2004;29:837–841. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

119. Brook DW, Brook JS, Zhang C. Joint trajectories of smoking and depressive mood: associations with later low perceived self-control and low well-being. J Addict Dis. 2014;33:53–64. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2014.882717. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

120. Fergusson DM, Goodwin RD, Horwood LJ. Major depression and cigarette smoking: results of a 21-year longitudinal study. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1357–1367. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703008596 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychol Med. 2003;33:1357–1367. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703008596 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

121. Maslowsky J, Schulenberg JE, Zucker RA. Influence of conduct problems and depressive symptomatology on adolescent substance use: developmentally proximal versus distal effects. Dev Psychol. 2014;50:1179–1189. doi: 10.1037/a0035085. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

122. van Gool CH, Kempen GI, Penninx BW, Deeg DJ, Beekman AT, van Eijk JT. Relationship between changes in depressive symptoms and unhealthy lifestyles in late middle aged and older persons: results from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Age Ageing. 2003;32:81–87. doi: 10.1093/ageing/32.1.81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

123. Whitbeck LB, Yu M, McChargue DE, Crawford DM. Depressive symptoms, gender, and growth in cigarette smoking among indigenous adolescents. Addict Behav. 2009;34:421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.12.009. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

124. Lekka NP, Lee KH, Argyriou AA, Beratis S, Parks RW. Association of cigarette smoking and depressive symptoms in a forensic population. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24:325–330. doi: 10.1002/da.20235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Association of cigarette smoking and depressive symptoms in a forensic population. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24:325–330. doi: 10.1002/da.20235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

125. Windle M, Windle RC. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among middle adolescents: prospective associations and intrapersonal and interpersonal influences. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:215–226. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.69.2.215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

126. Patten CA, Hurt RD, Offord KP, et al. Relationship of tobacco use to depressive disorders and suicidality among patients treated for alcohol dependence. Am J Addict. 2003;12:71–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2003.tb00541.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

127. Beal SJ, Negriff S, Dorn LD, Pabst S, Schulenberg J. Longitudinal associations between smoking and depressive symptoms among adolescent girls. Prev Sci. 2013;15(4):506–515. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0402-x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

128. Galambos N, Leadbeater B, Barker E. Gender differences in and risk factors for depression in adolescence: a 4-year longitudinal study. Int J Beh Dev. 2004;28(1):16–25. doi: 10.1080/01650250344000235. [Google Scholar]

Gender differences in and risk factors for depression in adolescence: a 4-year longitudinal study. Int J Beh Dev. 2004;28(1):16–25. doi: 10.1080/01650250344000235. [Google Scholar]

129. Brook DW, Brook JS, Zhang C, Cohen P, Whiteman M. Drug use and the risk of major depressive disorder, alcohol dependence, and substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:1039–1044. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

130. Okeke NL, Spitz MR, Forman MR, Wilkinson AV. The associations of body image, anxiety, and smoking among Mexican-origin youth. J Adolesc Health. 2013.doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.03.011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

131. Brook JS, Brook DW, Zhang C. Psychosocial predictors of nicotine dependence in Black and Puerto Rican adults: a longitudinal study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(6):959–967. doi: 10.1080/14622200802092515. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

132. Breslau N, Kilbey MM, Andreski P. Nicotine dependence and major depression. New evidence from a prospective investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:31–35. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820130033006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

New evidence from a prospective investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:31–35. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820130033006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

133. Hamdi NR, Iacono WG. Lifetime prevalence and co-morbidity of externalizing disorders and depression in prospective assessment. Psychol Med. 2014;44:315–324. doi: 10.1017/s0033291713000627. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

134. Karp I, O’Loughlin J, Hanley J, Tyndale RF, Paradis G. Risk factors for tobacco dependence in adolescent smokers. Tob Control. 2006;15:199–204. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

135. Kleinjan M, Wanner B, Vitaro F, Van den Eijnden RJ, Brug J, Engels RC. Nicotine dependence subtypes among adolescent smokers: examining the occurrence, development and validity of distinct symptom profiles. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24:61–74. doi: 10.1037/a0018543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

136. Racicot S, McGrath JJ, Karp I, O’Loughlin J. Predictors of nicotine dependence symptoms among never-smoking adolescents: a longitudinal analysis from the Nicotine Dependence in Teens Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;130:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.006. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;130:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.006. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

137. DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, et al. Susceptibility to nicotine dependence: the Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youth 2 study. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e974–e983. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

138. Kendler KS, Gardner CO. Monozygotic twins discordant for major depression: a preliminary exploration of the role of environmental experiences in the aetiology and course of illness. Psychol Med. 2001;31:411–423. doi: 10.1017/S0033291701003622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

139. Bardone AM, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Dickson N, Stanton WR, Silva PA. Adult physical health outcomes of adolescent girls with conduct disorder, depression, and anxiety. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:594–601. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199806000-00009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

140. Kandel DB, Hu M-C, Griesler PC, Schaffran C. On the development of nicotine dependence in adolescence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91(1):26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

On the development of nicotine dependence in adolescence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91(1):26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

141. Tully EC, Iacono WG, McGue M. Changes in genetic and environmental influences on the development of nicotine dependence and major depressive disorder from middle adolescence to early adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 2010;22:831–848. doi: 10.1017/s0954579410000490. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

142. Goodwin RD, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Association between anxiety disorders and substance use disorders among young persons: results of a 21-year longitudinal study. J Psychiatr Res. 2004;38(3):295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2003.09.002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

143. Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM. Life course outcomes of young people with anxiety disorders in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1086–1093. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200109000-00018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

144. Goodwin RD, Kim JH, Weinberger AH, Taha F, Galea S, Martins SS. Symptoms of alcohol dependence and smoking initiation and persistence: a longitudinal study among US adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:718–723. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.08.026. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goodwin RD, Kim JH, Weinberger AH, Taha F, Galea S, Martins SS. Symptoms of alcohol dependence and smoking initiation and persistence: a longitudinal study among US adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:718–723. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.08.026. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

145. McKenzie M, Olsson CA, Jorm AF, Romaniuk H, Patton GC. Association of adolescent symptoms of depression and anxiety with daily smoking and nicotine dependence in young adulthood: findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Addiction. 2010;105:1652–1659. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03002.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

146. Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Sawyer SM, Wakefield M. Teen smokers reach their mid twenties. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.11.027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

147. Griesler PC, Hu MC, Schaffran C, Kandel DB. Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and nicotine dependence among adolescents: findings from a prospective, longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:1340–1350. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318185d2ad. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:1340–1350. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318185d2ad. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

148. Hu MC, Griesler P, Schaffran C, Kandel D. Risk and protective factors for nicotine dependence in adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52:1063–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02362.x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

149. Jamal M, Willem Van der Does AJ, Cuijpers P, Penninx BW. Association of smoking and nicotine dependence with severity and course of symptoms in patients with depressive or anxiety disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;126:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

150. Hooshmand S, Willoughby T, Good M. Does the direction of effects in the association between depressive symptoms and health-risk behaviors differ by behavior? A longitudinal study across the high school years. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

151. Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Tercyak KP, Cuevas J, Rodgers K, Patterson F. Identifying and characterizing adolescent smoking trajectories. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:2023–2034. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15598757 Accessed September 15, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Tercyak KP, Cuevas J, Rodgers K, Patterson F. Identifying and characterizing adolescent smoking trajectories. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:2023–2034. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15598757 Accessed September 15, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

152. Saules KK, Pomerleau CS, Snedecor SM, et al. Relationship of onset of cigarette smoking during college to alcohol use, dieting concerns, and depressed mood: results from the Young Women’s Health Survey. Addict Behav. 2004;29:893–899. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

153. White HR, Violette NM, Metzger L, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Adolescent risk factors for late-onset smoking among African American young men. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:153–161. doi: 10.1080/14622200601078350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

154. Juon HS, Ensminger ME, Sydnor KD. A longitudinal study of developmental trajectories to young adult cigarette smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66:303–314. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00008-X. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00008-X. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

155. Hu MC, Griesler PC, Schaffran C, Wall MM, Kandel DB. Trajectories of criteria of nicotine dependence from adolescence to early adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125:283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.03.001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

156. Brook JS, Ning Y, Brook DW. Personality risk factors associated with trajectories of tobacco use. Am J Addict. 2006;15(6):426–433. doi: 10.1080/10550490600996363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

157. Steuber TL, Danner F. Adolescent smoking and depression: which comes first? Addict Behav. 2006;31:133–136. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

158. Jamal M, Does AJ, Penninx BW, Cuijpers P. Age at smoking onset and the onset of depression and anxiety disorders. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:809–819.doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

159. Button KS, Ioannidis JP, Mokrysz C, et al. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:365–376. doi: 10.1038/nrn3475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:365–376. doi: 10.1038/nrn3475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

160. Mickens L, Greenberg J, Ameringer KJ, Brightman M, Sun P, Leventhal AM. Associations between depressive symptom dimensions and smoking dependence motives. Eval Health Prof. 2011;34:81–102. doi: 10.1177/0163278710383562. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

161. Leventhal AM, Ameringer KJ, Osborn E, Zvolensky MJ, Langdon KJ. Anxiety and depressive symptoms and affective patterns of tobacco withdrawal. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:324–329. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.06.015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

162. Leventhal AM, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB. Smoking-related correlates of depressive symptom dimensions in treatment-seeking smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:668–676. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr056. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

163. Heron J, Hickman M, Macleod J, Munafo MR. Characterizing patterns of smoking initiation in adolescence: comparison of methods for dealing with missing data. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(12):1266–1275. doi: 10.1093/Ntr/Ntr161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(12):1266–1275. doi: 10.1093/Ntr/Ntr161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

164. Gage SH, Smith GD, Zammit S, Hickman M, Munafò MR. Using Mendelian randomisation to infer causality in depression and anxiety research. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:1185–1193. doi: 10.1002/da.22150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

165. Furberg H, Ostroff J, Lerman C, Sullivan PF. The public health utility of genome-wide association study results for smoking behavior. Genome Med. 2010;2:26. doi: 10.1186/gm147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

166. Ware JJ, van den Bree M, Munafò MR. From men to mice: CHRNA5/CHRNA3, smoking behavior and disease. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:1291–1299. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

167. Taylor AE, Fluharty ME, Bjørngaard JH, et al. Investigating the possible causal association of smoking with depression and anxiety using Mendelian randomisation meta-analysis: the CARTA consortium. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e006141. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014–006141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

BMJ Open. 2014;4:e006141. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014–006141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

168. Lewis SJ, Araya R, Smith GD, et al. Smoking is associated with, but does not cause, depressed mood in pregnancy—a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS One. 2011;6(7). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021689. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

169. Hamet P, Tremblay J. Genetics and genomics of depression. Metabolism. 2005;54(5 Suppl 1):10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.01.006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

170. Norrholm SD, Ressler KJ. Genetics of anxiety and trauma-related disorders. Neuroscience. 2009;164:272–287. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.06.036. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

171. Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric GWAS Consortium , Ripke S, Wray NR, et al. A mega-analysis of genome-wide association studies for major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(4):497–511. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Smoking contributed to the development of schizophrenia and depression

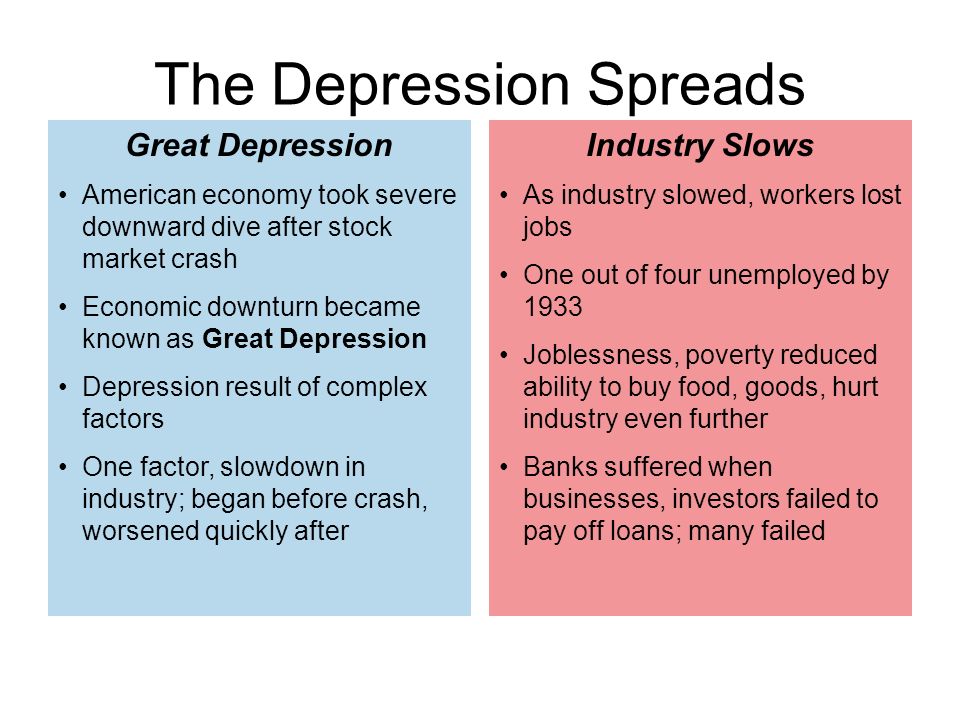

British geneticists have found a causal relationship between smoking and the risk of schizophrenia and depression. Using a genome-wide association analysis, they showed that smokers were 2.27 times more likely to develop schizophrenia and 1.99 times more likely to develop depression. At the same time, feedback was also observed - but only for depression. An article describing the study was published in Psychological Medicine .

Using a genome-wide association analysis, they showed that smokers were 2.27 times more likely to develop schizophrenia and 1.99 times more likely to develop depression. At the same time, feedback was also observed - but only for depression. An article describing the study was published in Psychological Medicine .

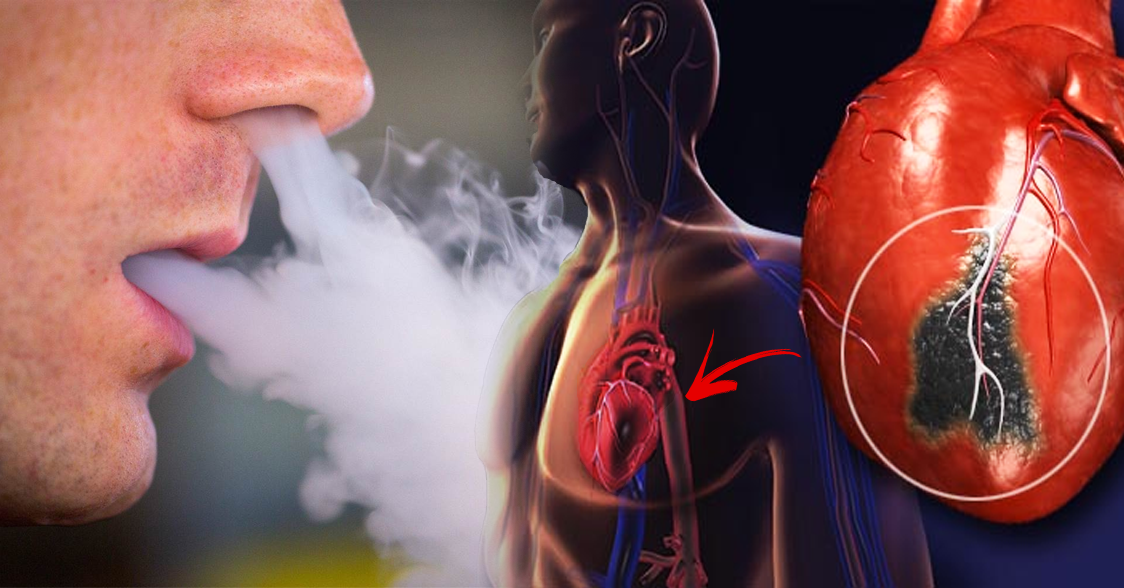

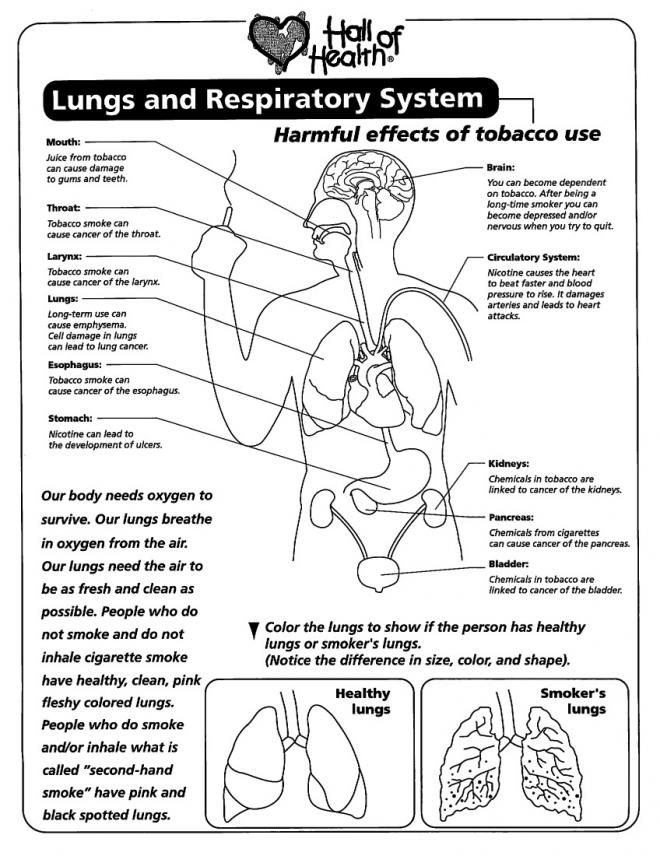

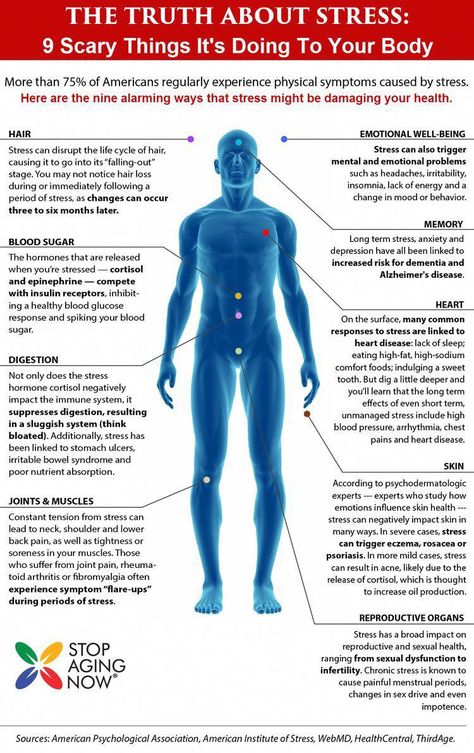

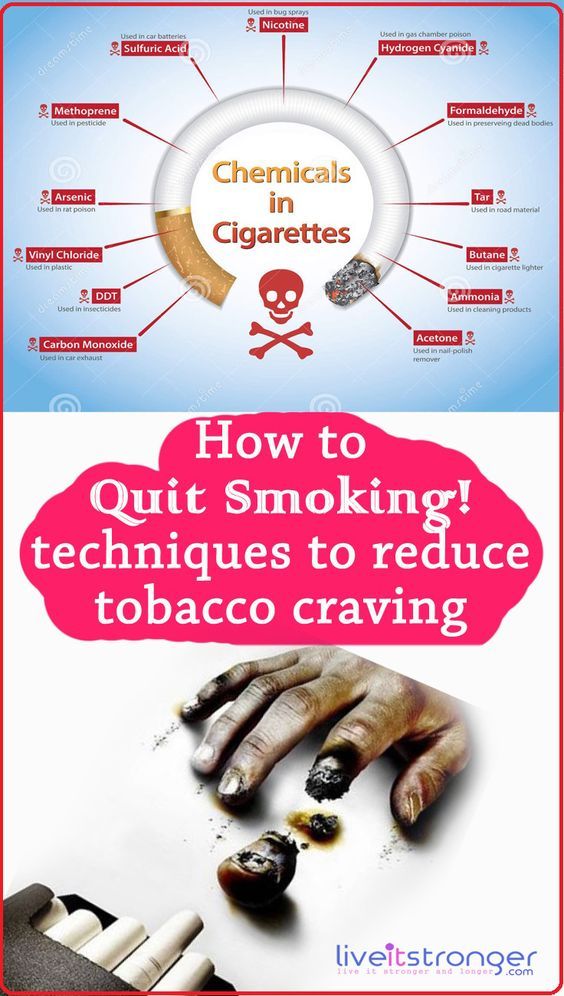

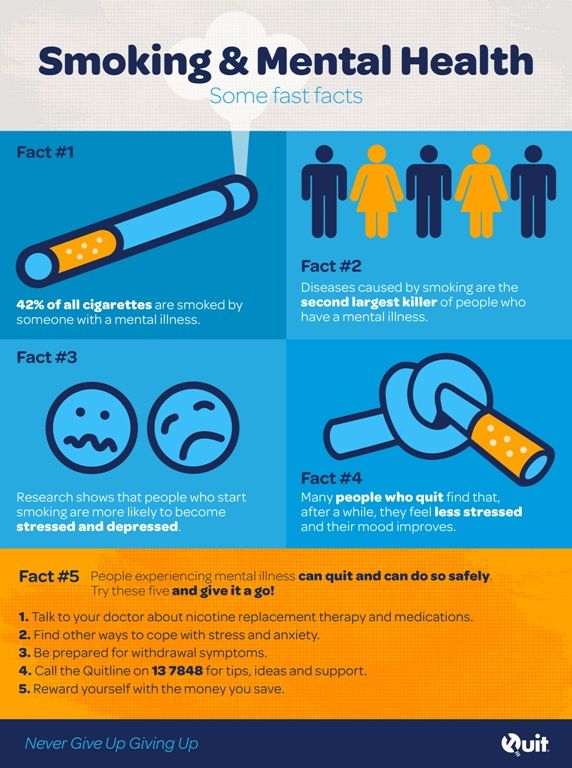

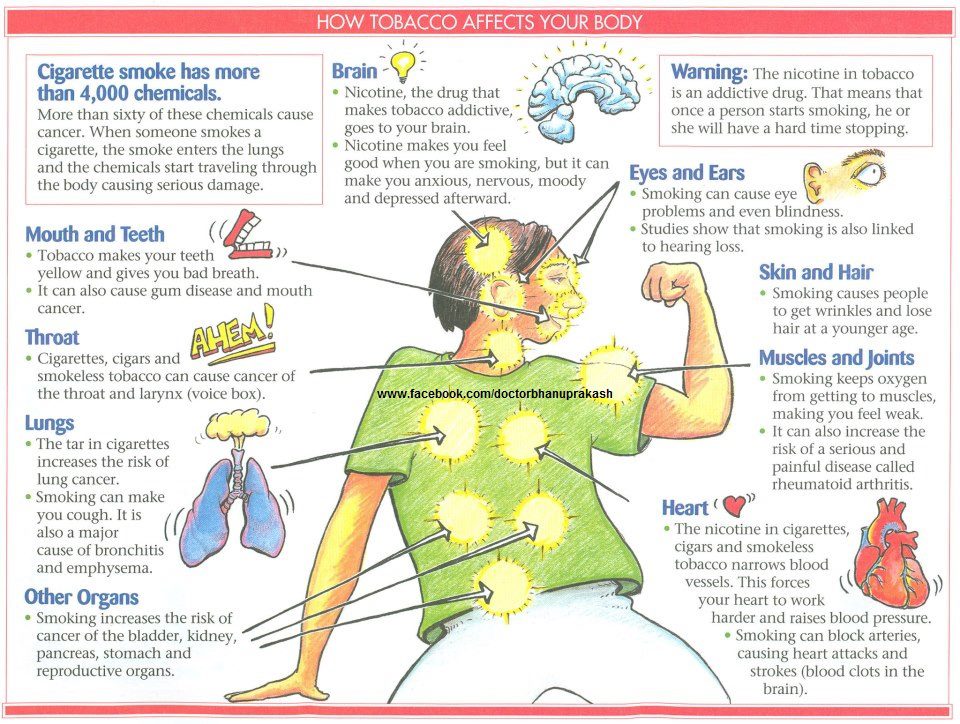

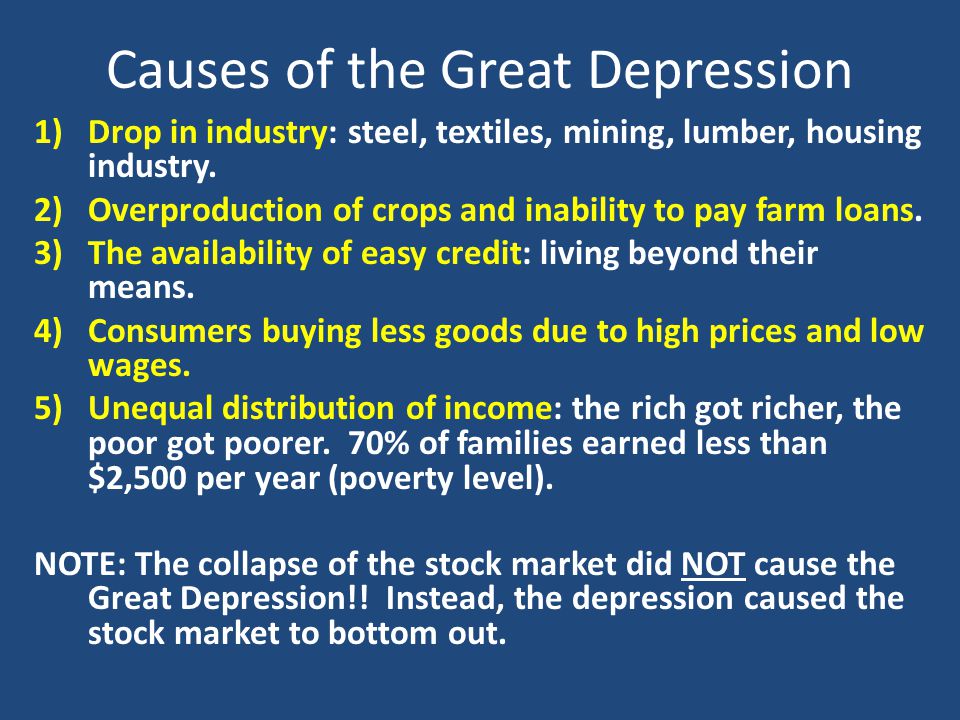

There are more smokers among people with mental disorders than among the healthy population. Due to the additional health problems that smoking causes (such as lung disease and cardiovascular disease), their life expectancy can be significantly reduced, so the nature of the relationship between smoking and mental disorders needs to be understood accurately. However, it is not always obvious and it is not possible to establish it exactly even with the help of studying biochemical mechanisms.

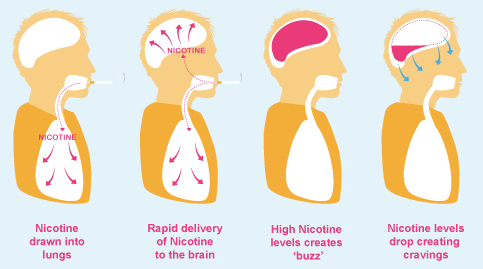

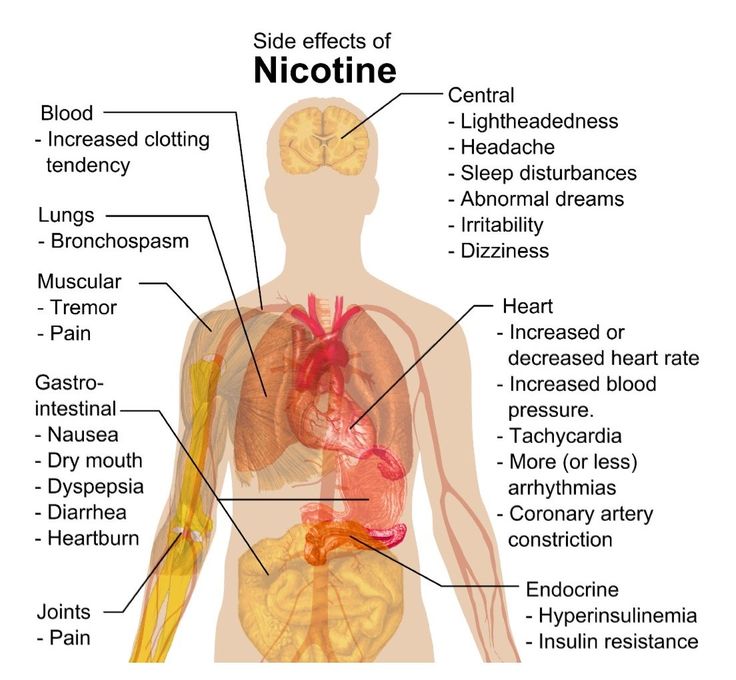

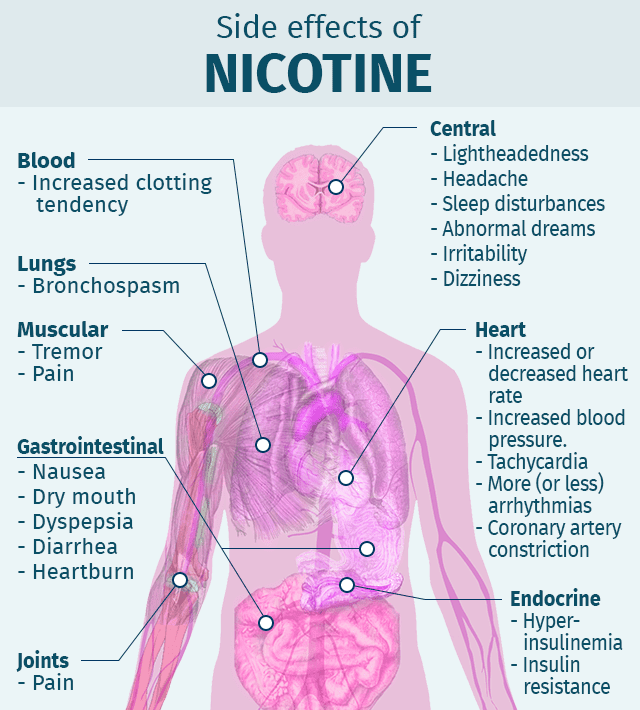

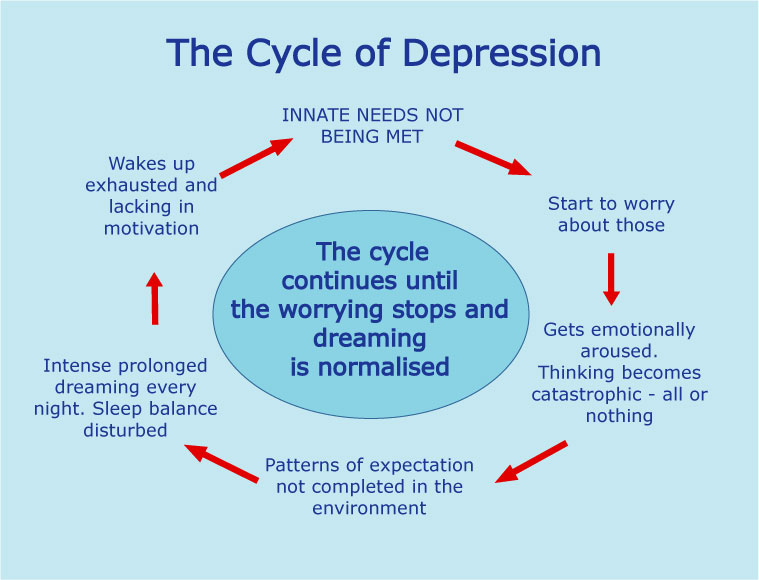

It is known, for example, that substances contained in tobacco inhibit the production of monoamine oxidase, an enzyme that breaks down monoamine neurotransmitters, such as dopamine. Antidepressants from the group of monoamine oxidase inhibitors have a related effect, from which it can be concluded that smoking could be used as a means of self-treatment in depression.

Antidepressants from the group of monoamine oxidase inhibitors have a related effect, from which it can be concluded that smoking could be used as a means of self-treatment in depression.

On the other hand, dopamine itself at high concentrations of nicotine in the body begins to be produced more strongly. Increased activity of dopaminergic neurons, in turn, is one of the obvious biomarkers of schizophrenia: this is why most of the drugs that stop the symptoms of the disease - antipsychotics - act specifically on dopamine. To show the connection between smoking and the development of mental disorders through the influence on the work of brain neurotransmitters, therefore, it is possible, but it will remain two-sided; in addition, smoking may well be a side variable.

Robin Wotton of the University of Bristol and colleagues tried to find a causal relationship between smoking and the risk of developing mental disorders using a genome-wide association search. To do this, they used the results of a recent study on genetic markers associated with smoking as a binary variable, which found 378 single nucleotide polymorphisms in a sample of more than 1. 3 million people.

3 million people.

After that they did their own research on the genomes of 462690 people who provided information on how much they smoke, how often, and their attempts to quit. In the end, the scientists were able to find 126 polymorphisms related to the duration of smoking, the number of cigarettes smoked, and whether people tried to stop (and also whether they succeeded).

Next, scientists used already known single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with the development of depression and schizophrenia (40 and 114, respectively). Scientists conducted a statistical analysis of the relationship between smoking and the development of mental disorders using Mendelian randomization methods - they evaluate the influence of genetic markers on the development of any trait as instrumental variables and help determine a causal relationship (with an eye to the fact that genetic factors are a variable random).

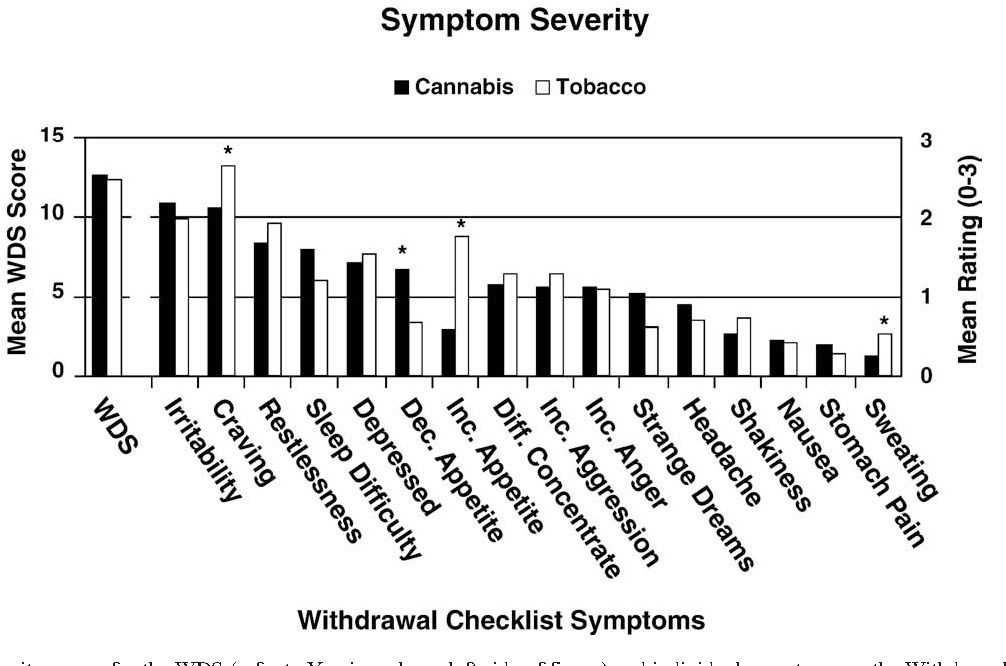

The analysis showed that smoking (both a binary variable and all studied indicators) is a risk factor for the development of both schizophrenia and depression (both p < 0. 001): smokers have a 2.27 times higher risk of developing schizophrenia, and depression - 1.99 times. An inverse relationship was found only for depression (p = 0.005), but not for schizophrenia, and there was a weak association between the presence of this disease and the onset of smoking.

001): smokers have a 2.27 times higher risk of developing schizophrenia, and depression - 1.99 times. An inverse relationship was found only for depression (p = 0.005), but not for schizophrenia, and there was a weak association between the presence of this disease and the onset of smoking.

The authors concluded that the relationship between smoking and the development of depression and schizophrenia is causal. However, they clarify that this is true only for a part of the studied population: due to the fact that an inverse relationship was also observed, but only for depression (this, apparently, is explained by the self-medication hypothesis), it is necessary to transfer the results to the entire population with caution. . The biochemical mechanism of such a connection remains to be studied: the authors, however, note that it most likely actually involves the work of monoamine neurotransmitters (not only dopamine, but also serotonin).

In recent years, genome-wide association studies have uncovered loci associated with, for example, insomnia and immediate reward predisposition, and have shown that homosexual intercourse cannot be explained purely genetically. However, scientists still doubt the need for genome-wide studies.

However, scientists still doubt the need for genome-wide studies.

Elizaveta Ivtushok

Found a typo? Select the fragment and press Ctrl+Enter.

Scientists have found out how smoking and depression are connected

Smoking can lead to depression, Israeli scientists say. Smokers are much more likely to experience depressive symptoms, and quitting the habit improves mental health.

Smoking is not only harmful to physical health, but is also associated with mental disorders, researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem found. The study was published in the journal PLOS ONE .

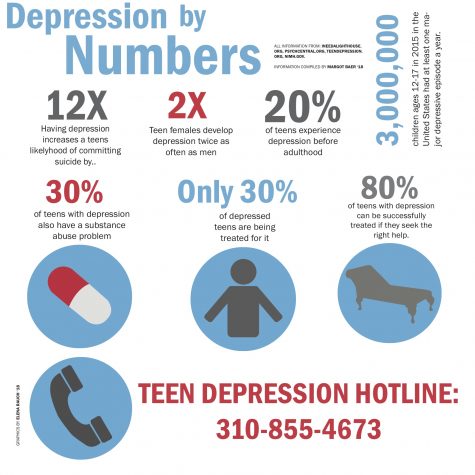

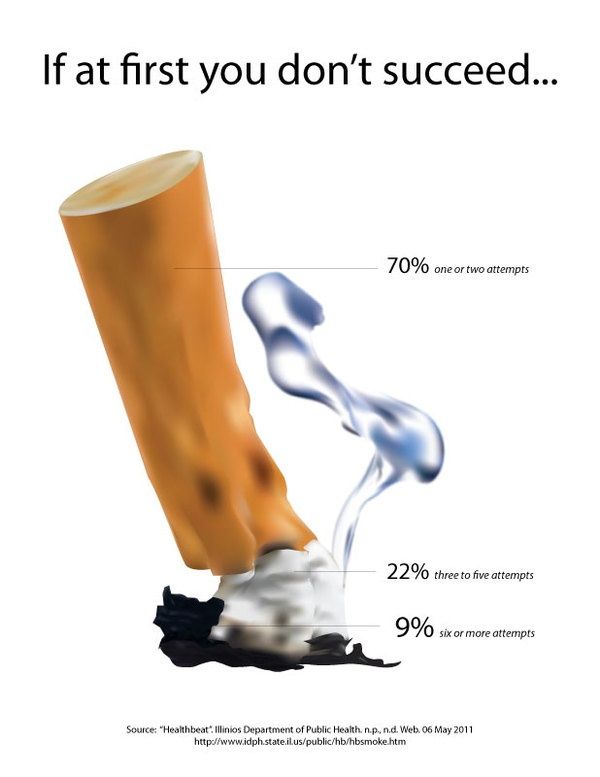

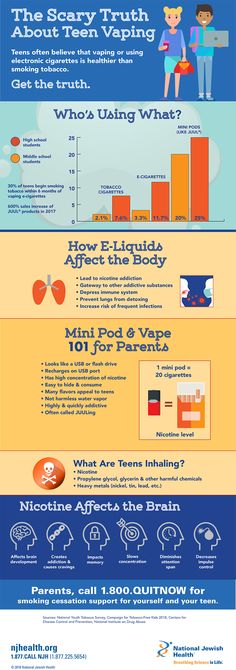

Smoking, including passive smoking, is one of the main risk factors for morbidity and mortality worldwide, the authors note. Almost 90% of smokers acquire this habit before adulthood, 98% before the age of 26.

Previous studies have shown that people with depression and other mental disorders are more likely to start smoking than mentally healthy people. In particular, many studies have noted that smokers have a much lower quality of life and more pronounced symptoms of anxiety and depression.

In particular, many studies have noted that smokers have a much lower quality of life and more pronounced symptoms of anxiety and depression.

More recent data have shown that there may be an inverse relationship - smoking becomes a predisposing factor for mental problems, and quitting it is associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms.

Together with colleagues from Serbia, the authors interviewed more than 2000 students of Serbian universities.

As it turned out, smoking students were several times more likely to suffer from depression than their non-smoking peers.

In particular, at the University of Pristina, depression was observed in 14% of smoking students and only 4% of non-smokers, and in the University of Belgrade - in 19% of smokers and 11% of non-smokers. Women were more likely to suffer from depressive symptoms.

In addition, regardless of economic or social status, students who smoke were also more likely to complain of depression and had lower mental health scores (energy, social functioning) than non-smokers.

“Our study confirms existing evidence that smoking and depression are closely linked,” says Prof. Hagai Levin. It's too early to say that smoking causes depression. But tobacco seems to have a negative effect on our mental health.”

The Israeli government is actively cracking down on smoking - as of 2020, cigarettes are banned from being displayed in stores, warning labels on packs are increased to 65% of the pack size, and all tobacco products and e-cigarettes must be sold in the same packaging, without logos or display manufacturer's brand.

Levin would like such measures to take into account the impact of smoking on mental health.

“I encourage universities to advocate for the health of their students by creating cigarette-free campuses where not only is smoking banned, but tobacco advertising is banned,” he says. “Combined with policies to prevent, screen for and treat mental illness, these steps will go a long way towards combating the harmful effects of smoking on our physical and mental health. ”

”

Researchers suggest that the effect of nicotine on the activity of neurotransmitters.

In addition, other chemicals in cigarette smoke indirectly stimulate the release of dopamine associated with feelings of satisfaction, which ultimately leads to mood swings.

Students generally have more mental health problems than non-graduate peers, the researchers note. This is probably due to the stress caused by the strict academic requirements. The authors of the work suggest that depression can push them to smoke, and then, in turn, only aggravate their condition. The researchers hope that quitting smoking will allow students to improve their mental health, but this remains to be tested.

Previously, British geneticists drew attention to the fact that

smoking can provoke not only depression, but also schizophrenia.

Since the prevalence of smoking among people with depression and schizophrenia is generally higher than among the rest of the population, they decided to find out whether the diseases predispose a person to smoking or vice versa.