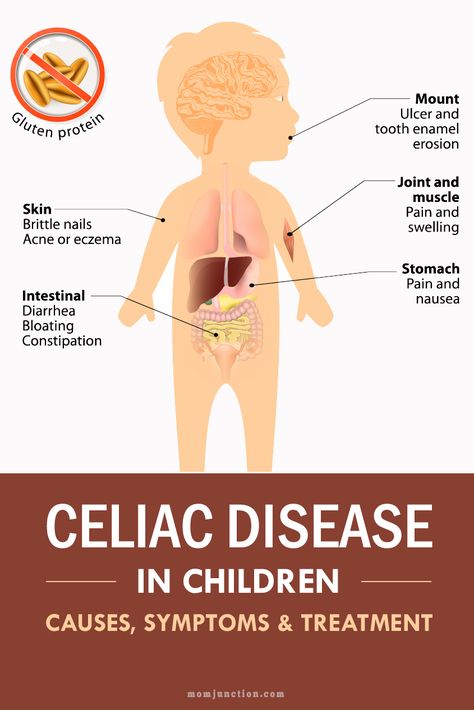

Celiac disease and anxiety

Psychological Impacts of Celiac Disease

How can a problem in the gut impact psychological functioning? What is the gut-brain connection and which areas of psychological functioning are most affected by celiac disease?

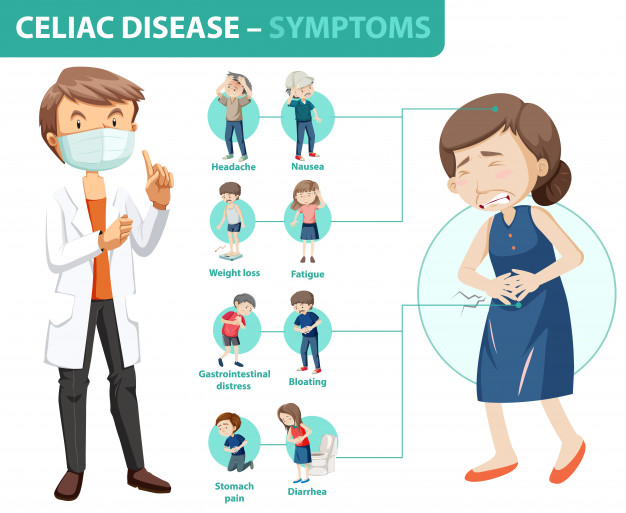

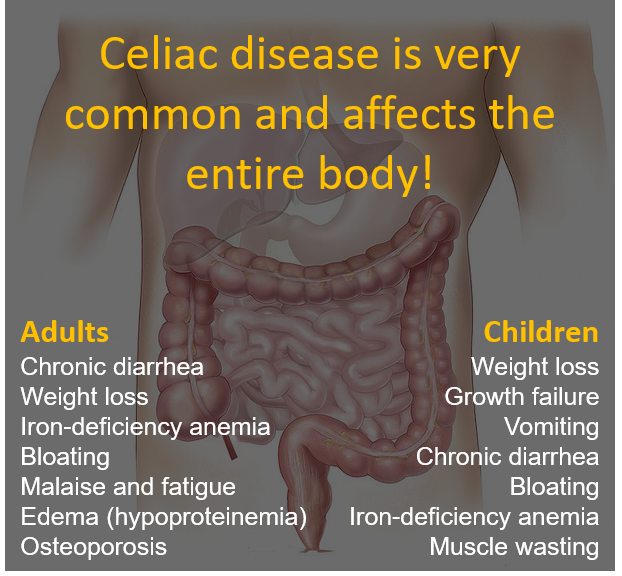

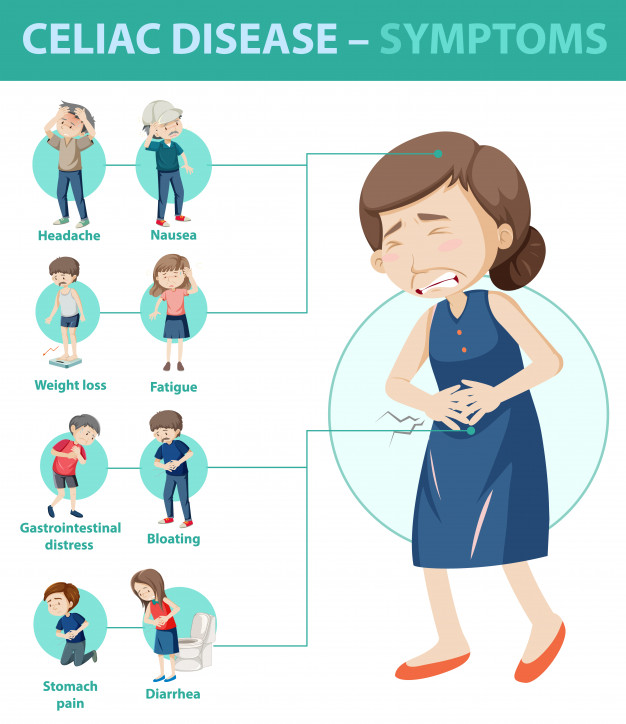

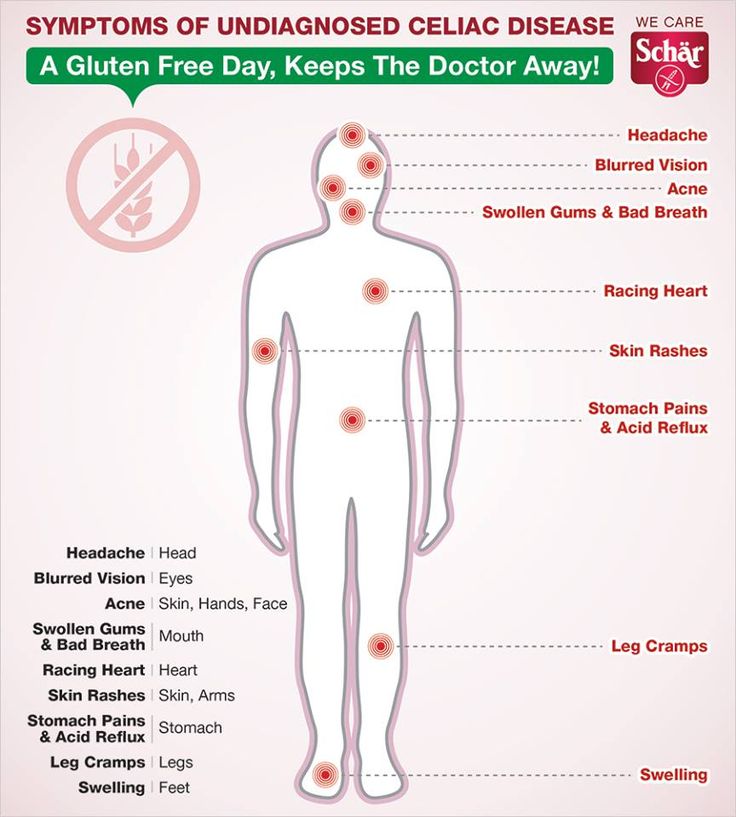

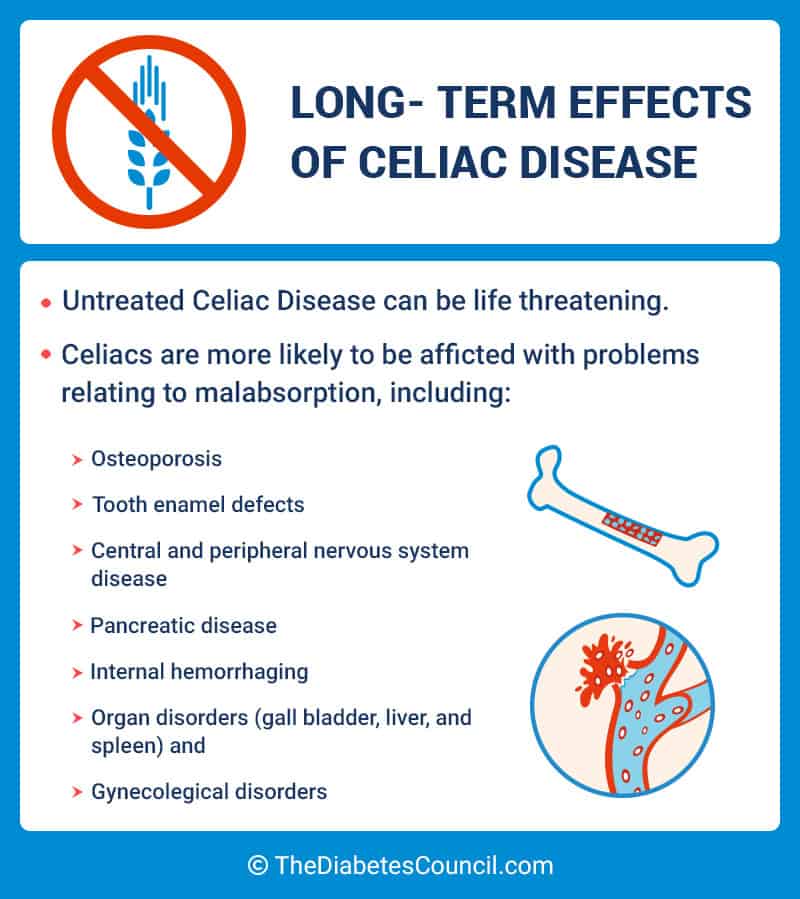

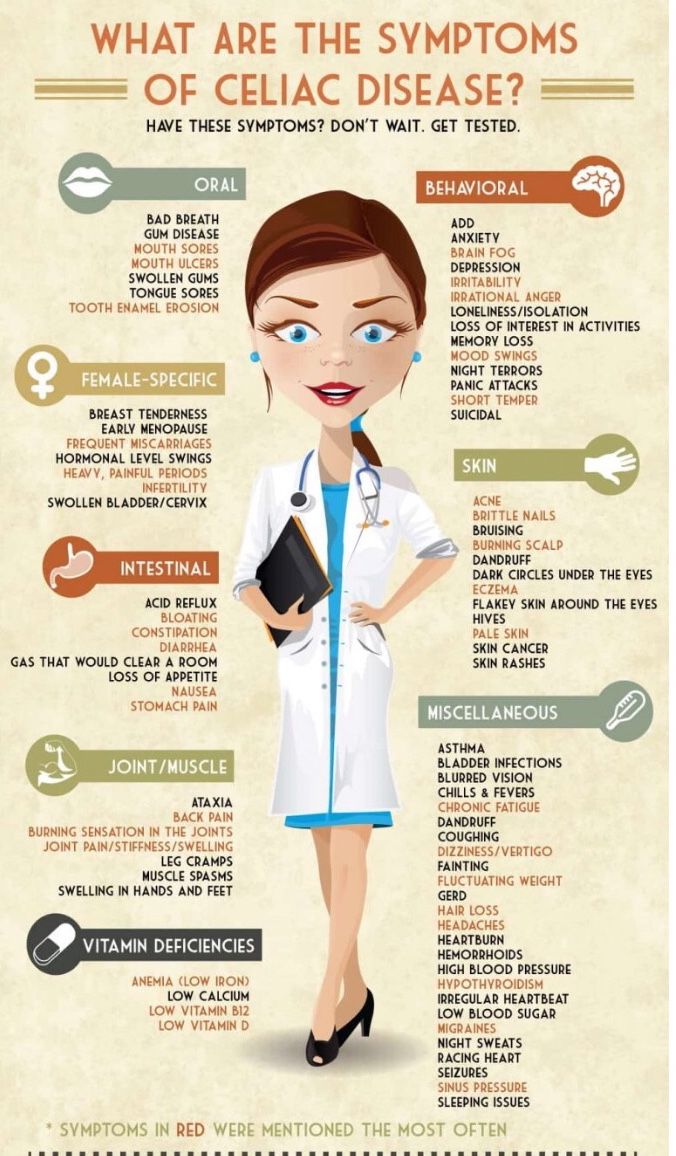

Research shows that untreated celiac disease can impact emotions, cognitive ability, behaviors, and more. Anxiety, depression and fatigue are common issues reported in celiac disease patients prior to diagnosis. Side effects of celiac disease can affect the brain in various ways, leading to a lower quality of life for those suffering from untreated celiac disease, and sometimes even after diagnosis, too.

Psychological Issues Associated with Celiac Disease

- Depression

- Moodiness, overwhelmed, non-restful sleep

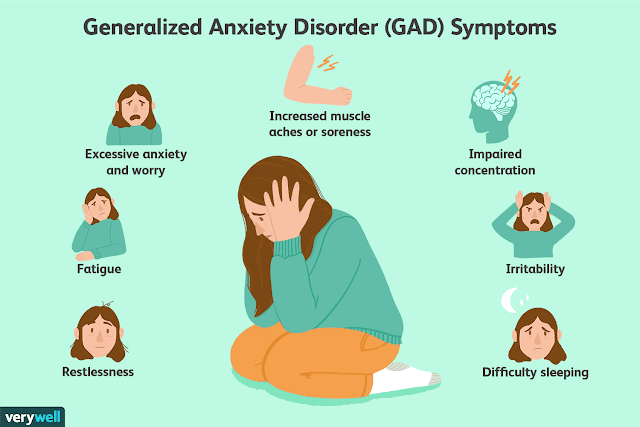

- Anxiety

- Phobias, separation anxiety, obsessive-compulsive tendencies, panic attacks

- Irritability

- Impatient and grumpiness in adults, outbursts of anger or temper tantrums in children

- ADHD

- Eating disorders

- Social anxiety

- Withdrawn, uncomfortable, and afraid of people

Neurological and Cognitive Issues Associated with Celiac Disease

- Brain fog

- Ataxia

- Memory lapse

- Headaches

- Migraines

- Difficulty paying attention

Latest Research on Celiac Disease and Brain Disorders and Mental Health

- 7/27/2021: Beyond Celiac Partners with University of Sheffield to Research Neuropathology of Celiac Disease and Gluten-Related Disorders – Researchers continue to investigate the sometimes debilitating neuropsychological impairment in those with celiac disease and NCGS.

- 6/11/2021: Brain fog survey reveals details about the symptom – Brain fog is a symptom that gets a lot of attention in the celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity communities, but not as much attention from researchers.

- 6/2/2021: The burden of celiac disease includes ongoing symptoms, missed workdays and disordered eating – Young adults with celiac disease may have more anxiety, disordered eating attitudes and beliefs, and a lower quality of life, a study suggests.

- 3/22/2021 – Neurological and psychological symptoms of celiac disease exposed by Go Beyond Celiac – data from the Go Beyond Celiac Gluten Exposure Survey highlights a number of neurological and psychological symptoms that celiac disease patients report experiencing after exposure to gluten

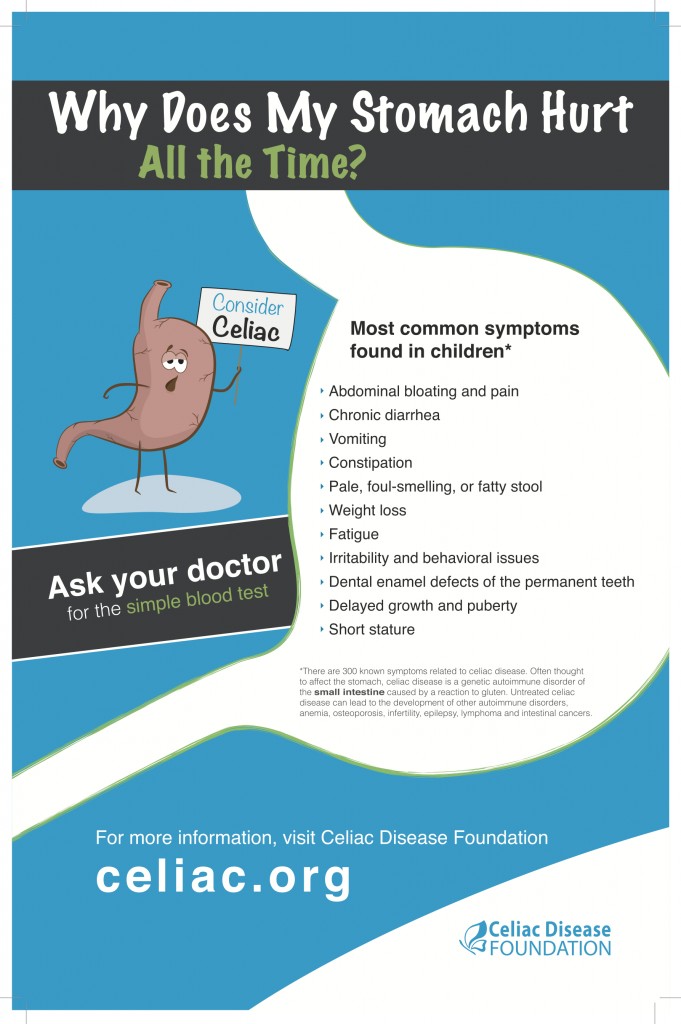

- 6/11/2020: Children with celiac disease at greater risk of mental health disorders – About one-third of children with celiac disease have mental health disorders, primarily anxiety disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), according to a new study.

- 3/25/2020: Brain images show celiac disease-related damage – Brain injury, cognitive deficiency and mental health issues tied to gluten exposure, study finds.

Understanding the Link between Celiac Disease and Psychological Disorders

The gut and brain are intimately connected. Just thinking about food can cause the stomach to release fluids and prepare to eat. Some people make decisions based on a “gut feeling,” or experience “butterflies in their stomach” when they are excited or nervous. Others may experience diarrhea whenever they are particularly anxious (called “anxiety poops” or “stress poops” colloquially). These are all examples of how things that happen in the gut can affect the mind and vice versa. So it makes sense that when the gut is suffering because of celiac disease, the mind might suffer, too.

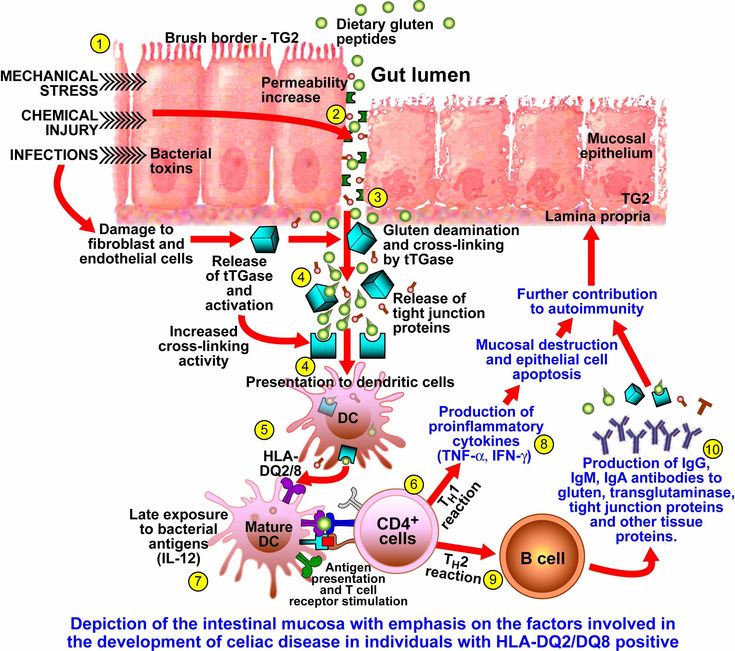

The exact reasons why those with celiac disease can experience negative psychological symptoms are varied, but include:

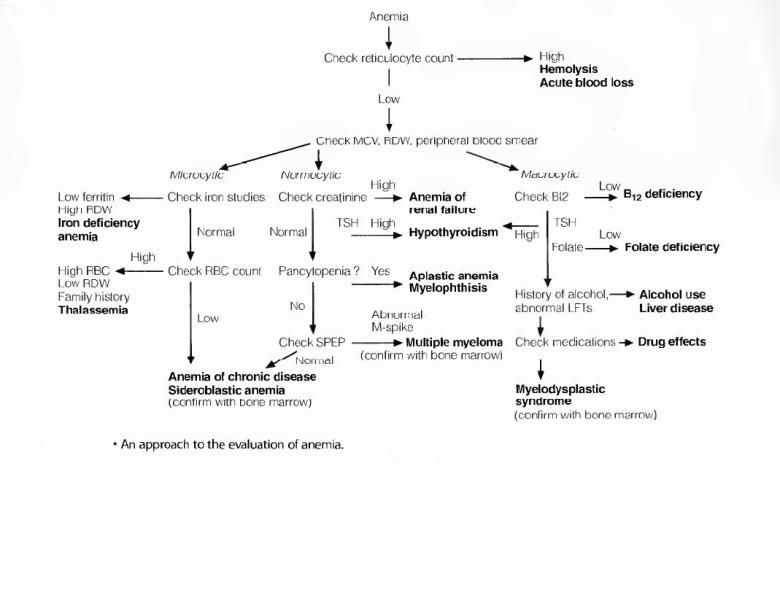

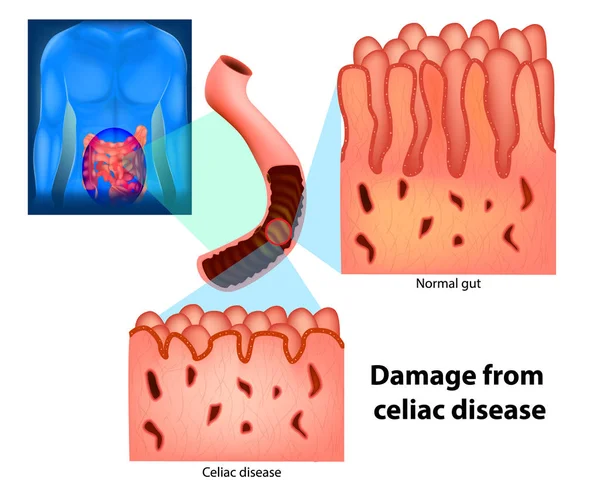

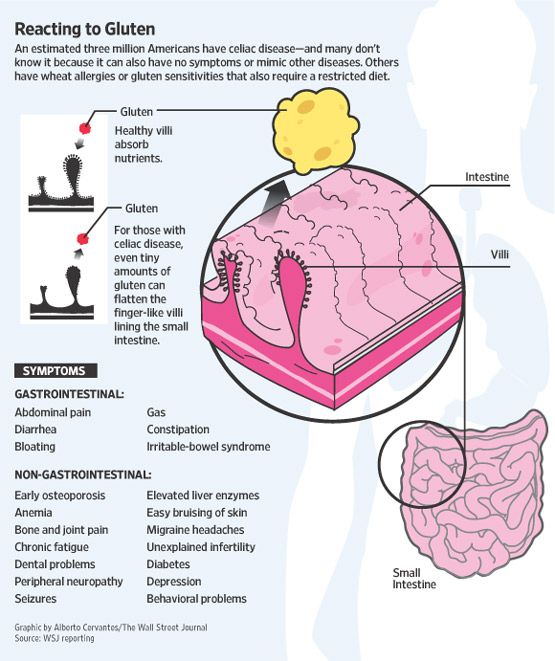

- Malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies

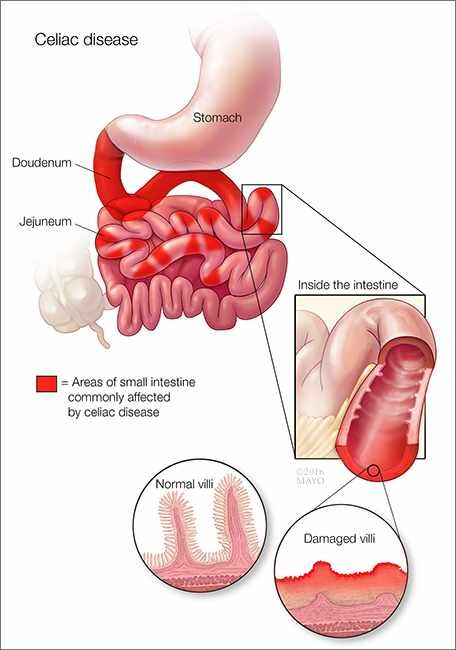

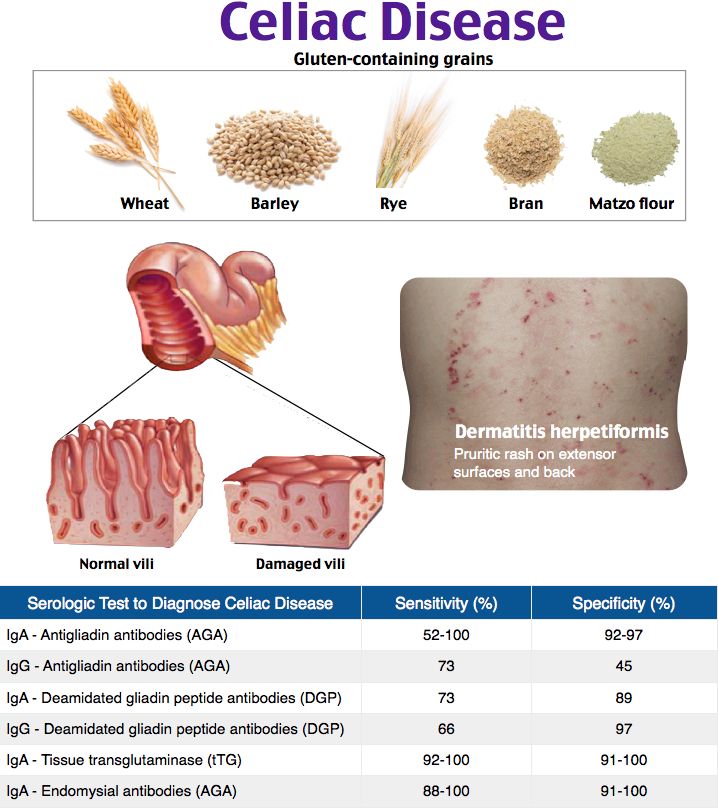

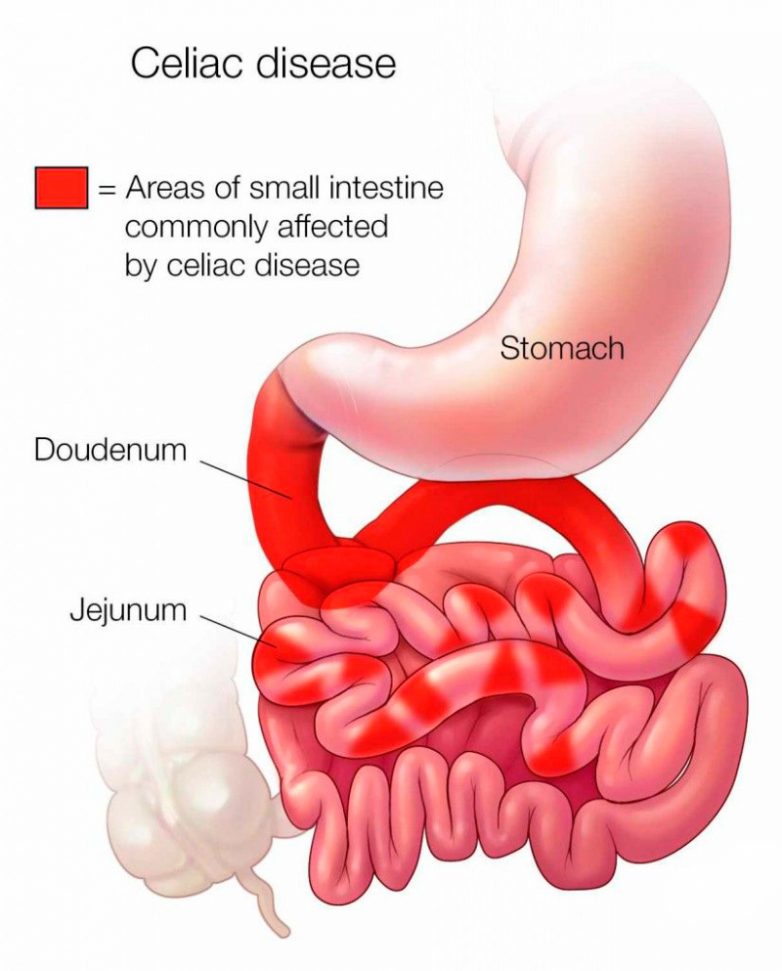

- Damaged villi, the distinguishing effect of celiac disease, make it difficult for the gut to assimilate nutrients essential for proper functioning of a number of organs.

- Notable nutritional deficiencies common in those with celiac disease include vitamin B (B6, B12, and Folate), iron, vitamin D, vitamin K, and calcium.

- The malnourished body may be unable to produce enough tryptophan and other monoamine precursors needed for the production of key neurotransmitters in the brain, such as serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine.

- This biochemical imbalance in the brain is associated with emotional problems.

- Damaged villi, the distinguishing effect of celiac disease, make it difficult for the gut to assimilate nutrients essential for proper functioning of a number of organs.

- Toxins

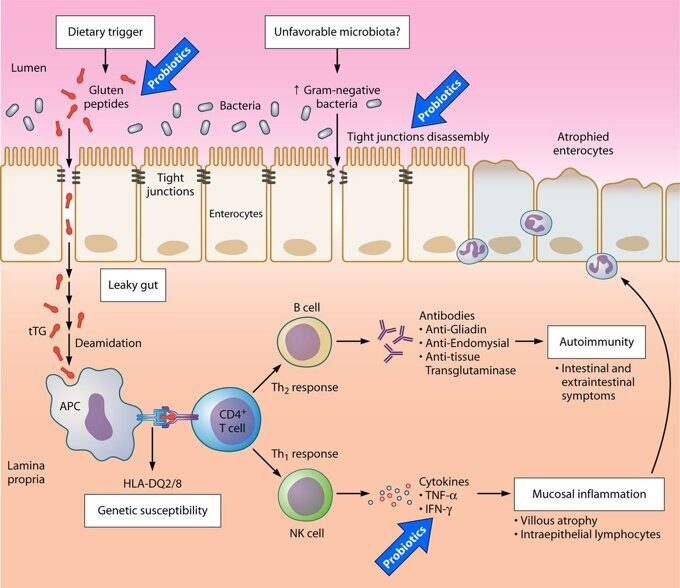

- Celiac disease is also associated with “leaky gut” syndrome.

- Poorly digested food overtax filtering organs such as the liver, leading to buildup.

- Some toxins affect opioid receptors of the brain.

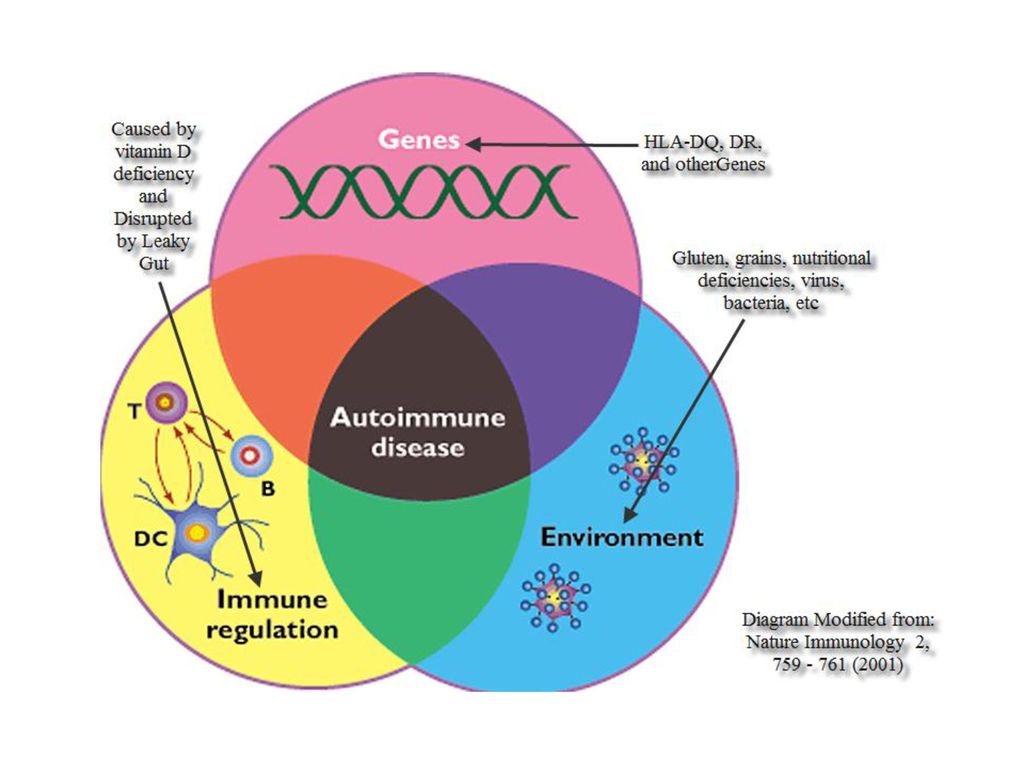

- Immune response

- Inflammation is the body’s natural response to assault.

- In the case of autoimmune illnesses, such as celiac disease, the body produces antibodies against the body’s own tissue.

- This manifests with symptoms like swelling, abdominal, joint pain, headaches, and hypoperfusion (low blood flow) in the brain.

- The immune response may also cause the production of stress hormones.

- Byproducts of digestion end up in the bloodstream and affect different parts of the body.

- Secondary diseases

- After many years of this autoimmune reactions, organs can become chronically affected and develop primary diseases.

- A common example is thyroid disease: studies show that in people who have celiac disease and depression, up to 80% of them have a comorbid thyroid disease.

- Social Isolation

- Some people dread social events or frequently decline to go at all because of their symptoms, such as fatigue, migraines, joint pain, itchy rashes, or a constant need to go to the bathroom. This can create feelings of social isolation, depression, and anxiety.

Mental Health Recovery Post-Celiac Disease Diagnosis

Some studies reveal complete remission of depression, anxiety and irritability with gluten-free diet, especially with younger populations. Other studies, especially on depression, are associated with mixed results.

Other studies, especially on depression, are associated with mixed results.

Here are a few things you can do after your diagnosis to help your brain recover:

- Stay gluten-free. No cheat days!

- Consider taking supplements until your gut heals.

- Exercise for about 30 minutes every day.

- Other organs may be damaged and require care, so talk to a doctor about getting additional tests to evaluate organ health and nutritional deficiencies.

- Try to become aware of your thinking habits and reframe overly negative or catastrophizing thoughts.

Let’s dive into that last bullet point. Did you know that the way we think creates neural connections in our brains? Humans develop habitual ways of thinking about situations and interpreting the world—they get used to using certain neural pathways. If you’re continually grumpy or sad for years, it becomes easier to feel grumpy or sad rather than happy. It make take effort to seek out and enjoy happiness.

It make take effort to seek out and enjoy happiness.

After many years of living in a bubble of discomfort, many forget to really live moments of well-being, satisfaction or joy. An official diagnosis can bring relief to many; however, others can feel emotionally secluded, socially isolated, or anxious and frustrated because of the gluten-free diet.

Some people reconnect with well-being through mindfulness exercises where they learn to “inhabit” happy and peaceful. Soaking up the good vibes, if you will. Meditation has also been found to increase cortical thickness.

Finally, studies show that connecting with others also enhances people’s ability to handle the gluten-free diet. Support groups and online forums can allow you to meet others who have experienced or are experiencing the same things, and counseling or therapy can provide personalized education around coping mechanisms for feelings of isolation and anxiety.

Possible Reasons for Continued Psychological Issues After Going Gluten-Free

Some possible reasons for continued celiac disease-related mental health problems after starting the gluten-free diet:

- Non-adherence to the gluten-free diet

- Unidentified food intolerances

- Thyroid problems

- Nutritional deficiencies

- Lengthy recovery period

- Difficulties accepting dietary change and its social implications

- Habitual ways of experiencing life

- Pre-existing conditions

It’s important to note that while many people see most of their ailments clear up after starting the gluten-free diet, there are also those that simply have a pre-existing psychological condition, not caused by or related to celiac disease. The gluten-free diet will not affect pre-existing conditions.

The gluten-free diet will not affect pre-existing conditions.

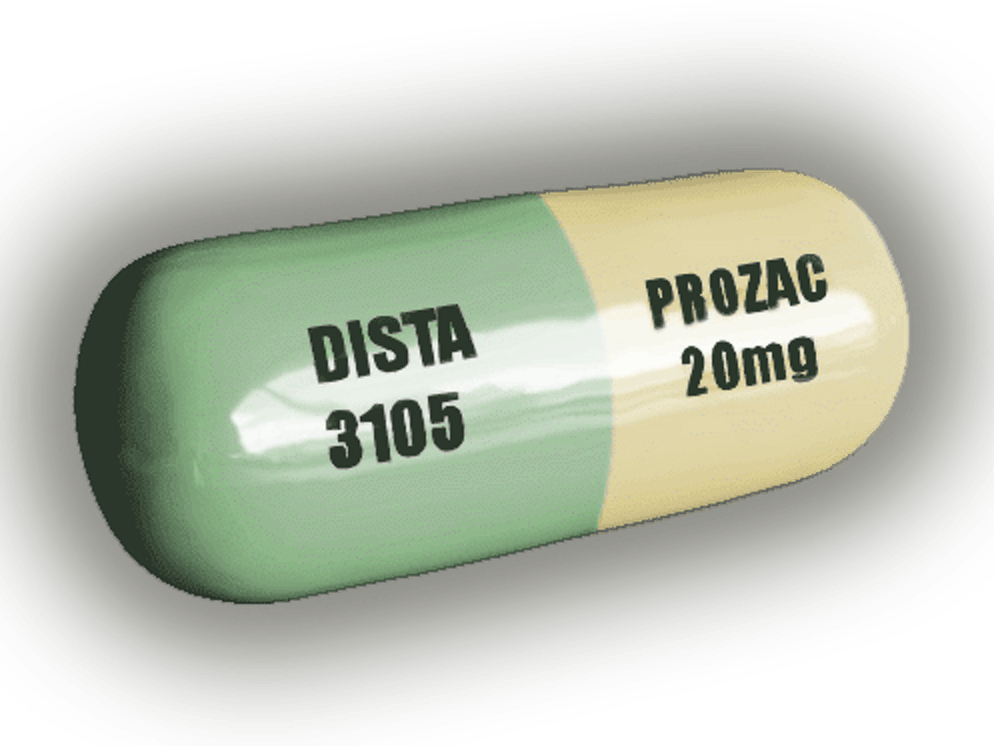

Treatments for pre-existing conditions include lifestyle changes and medications. If you take medication regularly, review the ingredients to ensure it is gluten-free. You should avoid medications with wheat starch when possible.

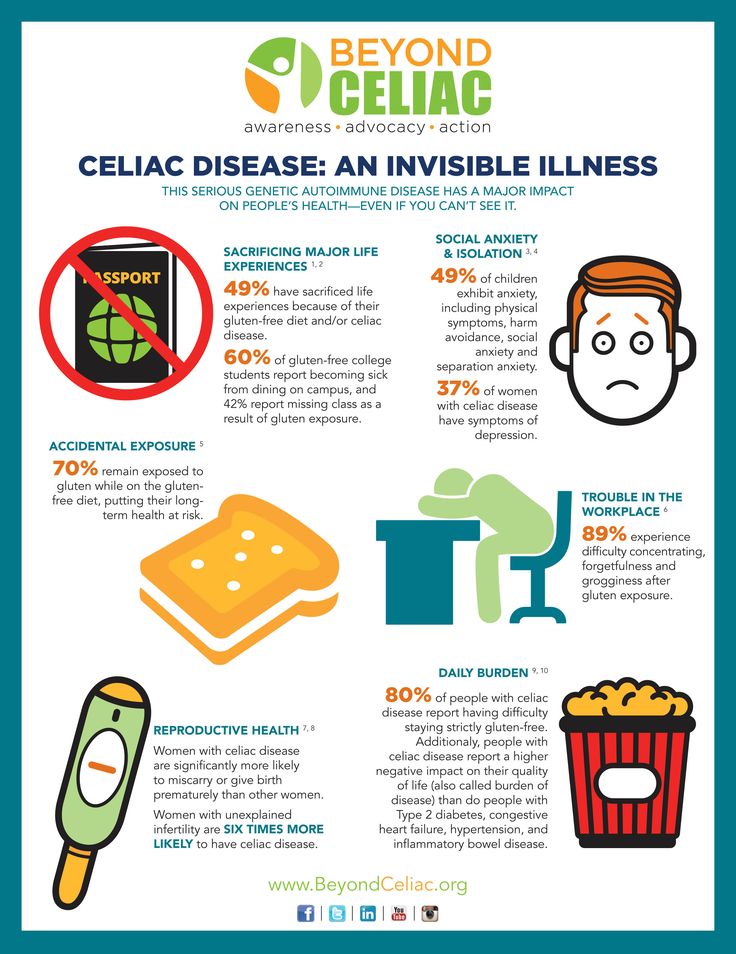

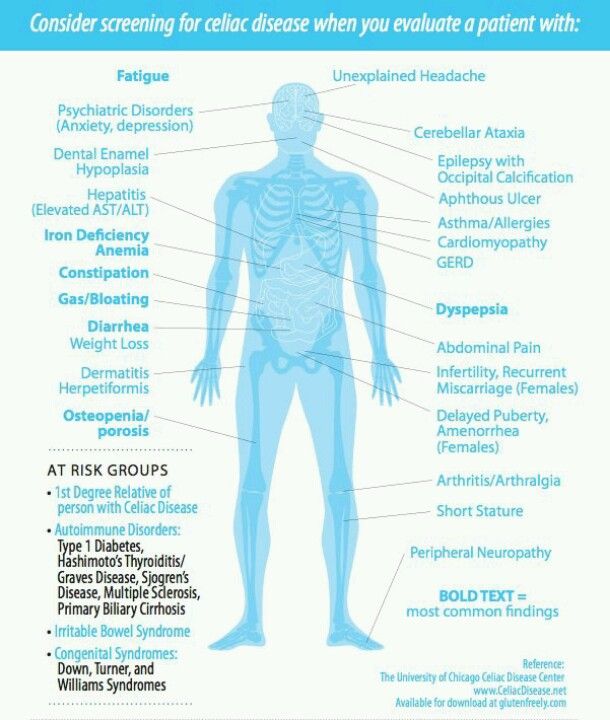

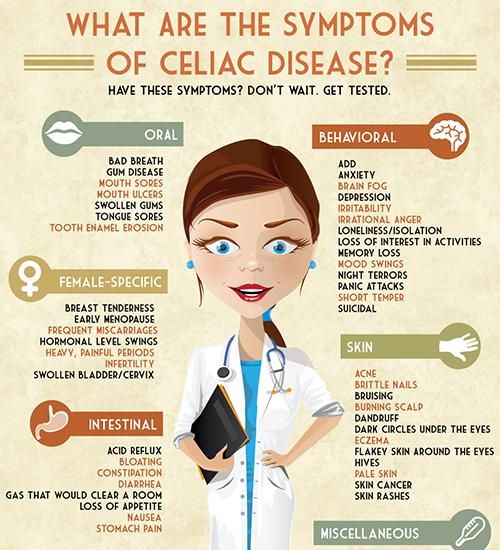

Infographic on the Psychosocial Impacts of Celiac Disease

(Click to enlarge image )

Neurologic and Psychiatric Manifestations of Celiac Disease and Gluten Sensitivity

1. Fasano A, Catassi C. Current approaches to diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease: An evolving spectrum. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:636–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Bizzaro N, Tozzoli R, Villalta D, Fabris M, Tonutti E. Cutting-edge issues in celiac disease and in gluten intolerance. Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s12016-010-8223-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Hadjivassiliou M, Grunewald RA, Davies-Jones GA. Gluten sensitivity as a neurological illness. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2002;72:560–563. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2002;72:560–563. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Hadjivassiliou M, Williamson CA, Woodroofe N. The immunology of gluten sensitivity: Beyond the gut. Trends in Immunology. 2004;25:578–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Sapone A, Lammers KM, Mazzarella G, Mikhailenko I, Carteni M, Casolaro V, et al. Differential mucosal IL-17 expression in two gliadin-induced disorders: Gluten sensitivity and the autoimmune enteropathy celiac disease. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 2010;152:75–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Kaukinen K, Turjanmaa K, Maki M, Partanen J, Venalainen R, Reunala T, et al. Intolerance to cereals is not specific for coeliac disease. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2000;35:942–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Bender L. Childhood schizophrenia. Psychiatric Quarterly. 1953;27:663–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Dohan FC. Wheat “consumption” and hospital admissions for schizophrenia during World War II. A preliminary report. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1966;18:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

A preliminary report. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1966;18:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Briani C, Zara G, Alaedini A, Grassivaro F, Ruggero S, Toffanin E, et al. Neurological complications of celiac disease and autoimmune mechanisms: A prospective study. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2008;195:171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Hadjivassiliou M, Grunewald RA, Chattopadhyay AK, Davies-Jones GA, Gibson A, Jarratt JA, et al. Clinical, radiological, neurophysiological, and neuropathological characteristics of gluten ataxia. Lancet. 1998;352:1582–1585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Hadjivassiliou M, Grunewald R, Sharrack B, Sanders D, Lobo A, Williamson C, et al. Gluten ataxia in perspective: Epidemiology, genetic susceptibility and clinical characteristics. Brain. 2003;126:685–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Bhatia KP, Brown P, Gregory R, Lennox GG, Manji H, Thompson PD, et al. Progressive myoclonic ataxia associated with coeliac disease. The myoclonus is of cortical origin, but the pathology is in the cerebellum. Brain. 1995;118 (Pt 5):1087–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brain. 1995;118 (Pt 5):1087–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Hadjivassiliou M, Boscolo S, Davies-Jones GA, Grunewald RA, Not T, Sanders DS, et al. The humoral response in the pathogenesis of gluten ataxia. Neurology. 2002;58:1221–1226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Hadjivassiliou M, Kandler RH, Chattopadhyay AK, Davies-Jones AG, Jarratt JA, Sanders DS, et al. Dietary treatment of gluten neuropathy. Muscle and Nerve. 2006;34:762–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Pellecchia MT, Scala R, Filla A, De Michele G, Ciacci C, Barone P. Idiopathic cerebellar ataxia associated with celiac disease: Lack of distinctive neurological features. Journal of Neurology, Neu-rosurgery and Psychiatry. 1999;66:32–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Chin RL, Sander HW, Brannagan TH, Green PH, Hays AP, Alaedini A, et al. Celiac neuropathy. Neurology. 2003;60:1581–1585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Chin RL, Latov N, Green PH, Brannagan TH, 3rd, Alaedini A, Sander HW. Neurologic complications of celiac disease. Journal of Clinical Neuromuscular Disease. 2004;5:129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Neurologic complications of celiac disease. Journal of Clinical Neuromuscular Disease. 2004;5:129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Morris JS, Ajdukiewicz AB, Read AE. Neurological disorders and adult coeliac disease. Gut. 1970;11:549–554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Pfaender M, D’Souza WJ, Trost N, Litewka L, Paine M, Cook M. Visual disturbances representing occipital lobe epilepsy in patients with cerebral calcifications and coeliac disease: A case series. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2004;75:1623–1625. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Arroyo HA, De Rosa S, Ruggieri V, de Davila MT, Fejerman N. Epilepsy, occipital calcifications, and oligosymptomatic celiac disease in childhood. Journal of Child Neurology. 2002;17:800–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Hernandez MA, Colina G, Ortigosa L. Epilepsy, cerebral calcifications and clinical or subclinical coeliac disease. Course and follow up with gluten-free diet. Seizure. 1998;7:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Seizure. 1998;7:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Canales P, Mery VP, Larrondo FJ, Bravo FL, Godoy J. Epilepsy and celiac disease: Favorable outcome with a gluten-free diet in a patient refractory to antiepileptic drugs. Neurologist. 2006;12:318–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Cernibori A, Gobbi G. Partial seizures, cerebral calcifications and celiac disease. Italian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 1995;16:187–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Fois A, Vascotto M, Di Bartolo RM, Di Marco V. Celiac disease and epilepsy in pediatric patients. Child’s Nervous System. 1994;10:450–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Peltola M, Kaukinen K, Dastidar P, Haimila K, Partanen J, Haapala AM, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis in refractory temporal lobe epilepsy is associated with gluten sensitivity. Journal of Neurology, Neu-rosurgery and Psychiatry. 2009;80:626–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Hadjivassiliou M, Rao DG, Wharton SB, Sanders DS, Grunewald RA, Davies-Jones AG. Sensory ganglionopathy due to gluten sensitivity. Neurology. 2010;75:1003–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sensory ganglionopathy due to gluten sensitivity. Neurology. 2010;75:1003–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Hadjivassiliou M, Chattopadhyay AK, Grunewald RA, Jarratt JA, Kandler RH, Rao DG, et al. Myopathy associated with gluten sensitivity. Muscle and Nerve. 2007;35:443–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Gabrielli M, Cremonini F, Fiore G, Addolorato G, Padalino C, Candelli M, et al. Association between migraine and Celiac disease: Results from a preliminary case-control and therapeutic study. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2003;98:625–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Poloni N, Vender S, Bolla E, Bortolaso P, Costantini C, Callegari C. Gluten encephalopathy with psychiatric onset: Case report. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2009;5:16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Kieslich M, Errazuriz G, Posselt HG, Moeller-Hartmann W, Zanella F, Boehles H. Brain white-matter lesions in celiac disease: A prospective study of 75 diet-treated patients. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pediatrics. 2001;108:E21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Addolorato G, Capristo E, Ghittoni G, Valeri C, Masciana R, Ancona C, et al. Anxiety but not depression decreases in coeliac patients after one-year gluten-free diet: A longitudinal study. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2001;36:502–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Cicarelli G, Della Rocca G, Amboni M, Ciacci C, Mazzacca G, Filla A, et al. Clinical and neurological abnormalities in adult celiac disease. Neurological Sciences. 2003;24:311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Carta MG, Hardoy MC, Boi MF, Mariotti S, Carpiniello B, Usai P. Association between panic disorder, major depressive disorder and celiac disease: A possible role of thyroid autoimmunity. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:789–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Niederhofer H, Pittschieler K. A preliminary investigation of ADHD symptoms in persons with celiac disease. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2006;10:200–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Genuis SJ, Bouchard TP. Celiac disease presenting as autism. Journal of Child Neurology. 2010;25:114–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Genuis SJ, Bouchard TP. Celiac disease presenting as autism. Journal of Child Neurology. 2010;25:114–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. De Santis A, Addolorato G, Romito A, Caputo S, Giordano A, Gambassi G, et al. Schizophrenic symptoms and SPECT abnormalities in a coeliac patient: Regression after a gluten-free diet. Journal of Internal Medicine. 1997;242:421–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Samaroo D, Dickerson F, Kasarda DD, Green PH, Briani C, Yolken RH, et al. Novel immune response to gluten in individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;118:248–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Cascella NG, Kryszak D, Bhatti B, Gregory P, Kelly DL, Mc Evoy JP, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease and gluten sensitivity in the United States clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness study population. Schizophrenia Research. 2011;37:94–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Addolorato G, Mirijello A, D’Angelo C, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Vonghia L, et al. Social phobia in coeliac disease. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;43:410–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Social phobia in coeliac disease. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;43:410–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Hauser W, Janke KH, Klump B, Gregor M, Hinz A. Anxiety and depression in adult patients with celiac disease on a gluten-free diet. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;16:2780–2787. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Ludvigsson JF, Reutfors J, Osby U, Ekbom A, Montgomery SM. Coeliac disease and risk of mood disorders—a general population-based cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;99:117–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Ruuskanen A, Kaukinen K, Collin P, Huhtala H, Valve R, Maki M, et al. Positive serum antigliadin antibodies without celiac disease in the elderly population: Does it matter? Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;45:1197–1202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Corvaglia L, Catamo R, Pepe G, Lazzari R, Corvaglia E. Depression in adult untreated celiac subjects: Diagnosis by the pediatrician. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1999;94:839–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1999;94:839–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Atladottir HO, Pedersen MG, Thorsen P, Mortensen PB, Deleuran B, Eaton WW, et al. Association of family history of autoimmune diseases and autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2009;124:687–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Valicenti-McDermott MD, McVicar K, Cohen HJ, Wershil BK, Shinnar S. Gastrointestinal symptoms in children with an autism spectrum disorder and language regression. Pediatric Neurology. 2008;39:392–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. de Magistris L, Familiari V, Pascotto A, Sapone A, Frolli A, Iardino P, et al. Alterations of the intestinal barrier in patients with autism spectrum disorders and in their first-degree relatives. Journal of Pediatric and Gastroenterology Nutrition. 2010;51:418–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Knivsberg AM, Reichelt KL, Hoien T, Nodland M. A randomised, controlled study of dietary intervention in autistic syndromes. Nutritional Neuroscience. 2002;5:251–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2002;5:251–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Whiteley P, Haracopos D, Knivsberg AM, Reichelt KL, Parlar S, Jacobsen J, et al. The ScanBrit randomised, controlled, single-blind study of a gluten- and casein-free dietary intervention for children with autism spectrum disorders. Nutritional Neuroscience. 2010;13:87–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Hsu CL, Lin CY, Chen CL, Wang CM, Wong MK. The effects of a gluten and casein-free diet in children with autism: A case report. Chang Gung Medical Journal. 2009;32:459–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Vojdani A, O’Bryan T, Green JA, McCandless J, Woeller KN, Vojdani E, et al. Immune response to dietary proteins, gliadin and cerebellar peptides in children with autism. Nutritional Neuroscience. 2004;7:151–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Kalaydjian AE, Eaton W, Cascella N, Fasano A. The gluten connection: The association between schizophrenia and celiac disease. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;113:82–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Graff H, Handford A. Celiac syndrome in the case histories of five schizophrenics. Psychiatric Quarterly. 1961;35:306–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Graff H, Handford A. Celiac syndrome in the case histories of five schizophrenics. Psychiatric Quarterly. 1961;35:306–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Dohan FC, Grasberger JC, Lowell FM, Johnston HT, Jr, Arbegast AW. Relapsed schizophrenics: More rapid improvement on a milk- and cereal-free diet. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1969;115:595–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Dohan FC, Grasberger JC. Relapsed schizophrenics: Earlier discharge from the hospital after cereal-free, milk-free diet. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1973;130:685–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Singh MM, Kay SR. Wheat gluten as a pathogenic factor in schizophrenia. Science. 1976;191:401–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Dohan FC, Levitt DR, Kushnir LD. Abnormal behavior after intracerebral injection of polypeptides from wheat gliadin: Possible relevance to schizophrenia. Pavlovian Journal of Biological Science. 1978;13:73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Rice JR, Ham CH, Gore WE. Another look at gluten in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1978;135:1417–1418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Another look at gluten in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1978;135:1417–1418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Vlissides DN, Venulet A, Jenner FA. A double-blind gluten-free/gluten-load controlled trial in a secure ward population. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;148:447–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Potkin SG, Weinberger D, Kleinman J, Nasrallah H, Luchins D, Bigelow L, et al. Wheat gluten challenge in schizophrenic patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1981;138:1208–1211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Cascella NG, Kryszak D, Bhatti B, Gregory P, Kelly DL, Mc Evoy JP, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease and gluten sensitivity in the United States clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness study population. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2011;37:94–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Dickerson F, Stallings C, Origoni A, Vaughan C, Khushalani S, Leister F, et al. Markers of gluten sensitivity and celiac disease in recent-onset psychosis and multi-episode schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:100–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:100–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Jin SZ, Wu N, Xu Q, Zhang X, Ju GZ, Law MH, et al. A study of circulating gliadin antibodies in schizophrenia among a Chinese population. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

63. Reichelt KL, Landmark J. Specific IgA antibody increases in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 1995;37:410–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Boscolo S, Sarich A, Lorenzon A, Passoni M, Rui V, Stebel M, et al. Gluten ataxia: Passive transfer in a mouse model. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1107:319–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Sander HW, Magda P, Chin RL, Wu A, Brannagan TH, 3rd, Green PH, et al. Cerebellar ataxia and coeliac disease. Lancet. 2003;362:1548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Burk K, Melms A, Schulz JB, Dichgans J. Effectiveness of intravenous immunoglobin therapy in cerebellar ataxia associated with gluten sensitivity. Annals of Neurology. 2001;50:827–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Annals of Neurology. 2001;50:827–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Hadjivassiliou M, Aeschlimann P, Strigun A, Sanders DS, Woodroofe N, Aeschlimann D. Autoanti-bodies in gluten ataxia recognize a novel neuronal transglutaminase. Annals of Neurology. 2008;64:332–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Alaedini A, Okamoto H, Briani C, Wollenberg K, Shill HA, Bushara KO, et al. Immune cross-reactivity in celiac disease: Anti-gliadin antibodies bind to neuronal synapsin I. Journal of Immunology. 2007;178:6590–6595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Palova-Jelinkova L, Rozkova D, Pecharova B, Bartova J, Sediva A, Tlaskalova-Hogenova H, et al. Gliadin fragments induce phenotypic and functional maturation of human dendritic cells. Journal of Immunology. 2005;175:7038–7045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Thomas KE, Sapone A, Fasano A, Vogel SN. Gliadin stimulation of murine macrophage inflammatory gene expression and intestinal permeability are MyD88-dependent: Role of the innate immune response in Celiac disease. Journal of Immunology. 2006;176:2512–2521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Journal of Immunology. 2006;176:2512–2521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Ashkenazi A, Krasilowsky D, Levin S, Idar D, Kalian M, Or A, et al. Immunologic reaction of psychotic patients to fractions of gluten. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1979;136:1306–1309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Pavol MA, Meyers CA, Rexer JL, Valentine AD, Mattis PJ, Talpaz M. Pattern of neurobehavioral deficits associated with interferon alfa therapy for leukemia. Neurology. 1995;45:947–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Denicoff KD, Rubinow DR, Papa MZ, Simpson C, Seipp CA, Lotze MT, et al. The neuropsychiatric effects of treatment with interleukin-2 and lymphokine-activated killer cells. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1987;107:293–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Hadjivassiliou M. Glutamic acid decarboxylase as a target antigen in gluten sensitivity: The link to neurological manifestations? Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Celiac Disease. Belfast. 2004 [Google Scholar]

75. Williamson S, Faulkner-Jones BE, Cram DS, Furness JB, Harrison LC. Transcription and translation of two glutamate decarboxylase genes in the ileum of rat, mouse and guinea pig. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1995;55:18–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Williamson S, Faulkner-Jones BE, Cram DS, Furness JB, Harrison LC. Transcription and translation of two glutamate decarboxylase genes in the ileum of rat, mouse and guinea pig. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1995;55:18–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Volta U, De Giorgio R, Granito A, Stanghellini V, Barbara G, Avoni P, et al. Anti-ganglioside antibodies in coeliac disease with neurological disorders. Digestive and Liver Diseases. 2006;38:183–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Santoro M, Thomas FP, Fink ME, Lange DJ, Uncini A, Wadia NH, et al. IgM deposits at nodes of Ranvier in a patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, anti-GM1 antibodies, and multifocal motor conduction block. Annals of Neurology. 1990;28:373–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Molander M, Berthold CH, Persson H, Andersson K, Fredman P. Monosialoganglioside (GM1) immunofluorescence in rat spinal roots studied with a monoclonal antibody. Journal of Neurocytology. 1997;26:101–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Hadjivassiliou M, Maki M, Sanders DS, Williamson CA, Grunewald RA, Woodroofe NM, et al. Autoantibody targeting of brain and intestinal transglutaminase in gluten ataxia. Neurology. 2006;66:373–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hadjivassiliou M, Maki M, Sanders DS, Williamson CA, Grunewald RA, Woodroofe NM, et al. Autoantibody targeting of brain and intestinal transglutaminase in gluten ataxia. Neurology. 2006;66:373–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Pynnonen PA, Isometsa ET, Veradale MA, Chaconne SA, Sipila I, Savilahti E, et al. Gluten-free diet may alleviate depressive and behavioural symptoms in adolescents with coeliac disease: A prospective follow-up case-series study. BMC Psychiatry. 2005;5:14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Hallert C, Sedvall G. Improvement in central monoamine metabolism in adult coeliac patients starting a gluten-free diet. Psychological Medicine. 1983;13:267–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychological characteristics in patients with celiac disease and their correction

UDK 616.34:612.821 LS Oreshko

II Mechnikova

The relevance of studying borderline psychosomatic adaptation disorders in diseases of the gastrointestinal tract is determined by the significant contribution of the latter to the structure of general morbidity.

According to the literature, the prevalence of adjustment disorders in general medical practice is 5-10%. With gastroenterological pathology, the value of this indicator increases significantly and reaches 45.5% [1].

Currently, celiac disease occupies one of the most stable positions in the structure of gastroenterological pathology and is characterized by the formation of a spectrum of reactions with anxiety, anxiety-phobic, neurasthenic, affective, hypochondriacal symptoms.

From a clinical and pathogenetic point of view, celiac disease is a chronic relapsing disease with a primary lesion of the small intestine due to incomplete breakdown of cereal protein peptides [2]. The gradual progression of the disease leads to the appearance of various symptoms that contribute to the formation and fixation of pathological personality changes in patients with celiac disease. In the development of psychological disorders, an important role is played by the relationship of personality-mediated reactive formations with significant parameters of somatic disease [3].

In this regard, an important scientific trend is the search for general patterns of human response to a disease under the conditions of risk factors that contribute to adaptation and changing its place and role in social life [4].

Psychopharmacotherapy of such disorders, defined as adjustment disorders, seems to be a difficult and at the same time an urgent task.

The purpose of this study was to study the effectiveness of a derivative of 2-mercaptobenzimidazole, a "short-lived" drug with an anxiolytic effect - afobazole in patients with celiac disease with anxiety and asthenic disorders during course treatment at the optimal therapeutic dose of 30 mg / day.

Materials and research methods. The study of the therapeutic efficacy of afobazole was carried out in patients with celiac disease with various individual typological characteristics: anxiety, anxiety-phobic and asthenic disorders. The mental state of the studied patients was determined by manifestations of constant internal tension, anxiety, fixation on the situation, their condition, inability to cope with problems on their own, anxious fears of the possibility of a serious illness, loss of working capacity. Along with this, emotional reactive lability with reactions of

Along with this, emotional reactive lability with reactions of

© LS Oreshko, 2008

irritations, difficulty concentrating, feeling tired, tendency to anger and increased excitability.

17 patients with celiac disease were under observation. The diagnosis was established on the basis of clinical and anamnestic data, endoscopic examination with a biopsy of the duodenal mucosa, histomorphological, immunological and immunogenetic research methods. Description of changes in the morphological structure of the duodenal mucosa with an assessment of linear parameters, morphofunctional parameters and free cells, including interepithelial lymphocytes, was used to verify the diagnosis according to two classification estimates - R. Whitehead and M. N. Marsh, P. T. Crowe (1995). The mean age of the patients was 35.3±3.5 years. The ratio of men and women was 6 (35.3%): 11 (64.7%).

To characterize the action of afobazole and its therapeutic efficacy, a complex of standardized methods and scales was used.

All patients before and after the course of therapy with afobazole underwent a standardized questioning to identify and clarify the nature of complaints, assessment of psychosocial status: the levels of personal and situational anxiety were determined using a multidimensional questionnaire of the integrative anxiety test (ITT) using 6 additional subscales (ED - emotional discomfort, AST - asthenic component of anxiety, FOB - phobic component of anxiety, OP - perspective assessment, SZ - social reactions of defense) [5], neuroticism according to the neurotization level questionnaire according to L.I. Wasserman [6].

Course treatment was carried out at the optimal therapeutic dose of 30 mg/day for 4 weeks.

The received data were processed statistically, their analysis and comparative analysis were carried out. When analyzing the results of the study, the statistical software package STATISTICA 6.0 was used. A significance level of 0.05 was set.

Research results. Psychological examination revealed the initial psychopathological predisposition in patients with celiac disease, which is formed according to the mechanisms of reactive lability with anxiety, anxiety-phobic and asthenic disorders, which indicated the presence of characteristic personality disorders and psychosomatic maladaptation.

Psychological examination revealed the initial psychopathological predisposition in patients with celiac disease, which is formed according to the mechanisms of reactive lability with anxiety, anxiety-phobic and asthenic disorders, which indicated the presence of characteristic personality disorders and psychosomatic maladaptation.

The initial assessment of the ITT indicators made it possible to establish an increase in the levels of personal (ITT (ST-L)) and situational (ITT (ST-S)) anxiety in 100% and 66.7% of patients, respectively. The dynamics of indicators of personal and situational anxiety and their components are illustrated in fig. 1 and 2.

The structure of personal anxiety in patients with celiac disease was formed due to changes in emotional discomfort, asthenic and phobic components, perspective assessment and social protection. Emotional discomfort was observed in 16 patients who noted a reduced emotional background, dissatisfaction with the life situation, emotional tension, elements of agitation. The asthenic component in the structure of anxiety corresponded to a moderate level of increase and was diagnosed in 11 patients. The phobic component, manifested in the fear of adverse consequences, doubts about one's own capacity, fear of change, was detected in 2 patients.

The asthenic component in the structure of anxiety corresponded to a moderate level of increase and was diagnosed in 11 patients. The phobic component, manifested in the fear of adverse consequences, doubts about one's own capacity, fear of change, was detected in 2 patients.

Perspective evaluation was formed in the form of a projection of fears into the future, general concern about the future against the background of increased emotional sensitivity and was detected in 4 subjects. In the structure of anxiety, patients noted violations of

O4

1QQ

9000 9000

8Q

7Q

6Q

5Q

4000 4000 9000 3Q

2Q

1Q

Q

Q.000

Country

V. Generally General Before treatment

AST FOB OP □ After treatment

SZ

Fig. 1. Indicators of personal anxiety in patients with celiac disease against the background of therapy with apobasol according to ITT

O4

L

H

O

U

7Q

6Q

5Q

4000 4000 3Q

2Q

00 2Q

00 2Q 00 2Q 9000 2Q

00 2Q 1Q

Total ED AST

B Before treatment

FOB OP □ After treatment

SZ

2. Indicators of situational anxiety in patients with celiac disease during therapy with afobazole according to ITT

Indicators of situational anxiety in patients with celiac disease during therapy with afobazole according to ITT

in the field of social protection in 4 people who considered the social environment as the main source of anxiety and self-doubt.

Therapeutic dynamics of the mental state of patients treated with afobazole was characterized by positive dynamics of the indicators of the level of personal anxiety: there was a decrease in the level of general anxiety in 10 patients, as well as a decrease in the severity of emotional discomfort. The phobic component was observed in 4 patients. However, it should be noted that 16 patients reported an improvement in their condition. The data obtained reflect the positive impact of the drug on the assessment of prospects and social protection.

The structure of situational anxiety consisted of the above components, and an increase in indicators indicated psychological maladaptation. When interpreting situational anxiety in patients with celiac disease, the indicators correspond to a moderate level of anxiety and average 4. 49 points.

49 points.

Q

When comparing the assessment of indicators before and after course use of the drug afobazole, their positive dynamics is noted. In patients, there was a decrease in the experience of insufficient value of one's own personality, a pessimistic assessment of the prospects. Psychoasthenic difficulties in situations of decision-making and interpersonal interaction were observed less frequently, which reflected the improvement in social functioning. The final assessment showed the restoration of habitual activity and resistance to stress.

The baseline estimate of the level of neuroticism (NL) in patients with celiac disease before therapy was changed in 11 patients, and in 7 patients the NL was increased, in 3 - high and in 1 - very high. After a four-week course of treatment with afobazole, NR remained elevated in 3 examined patients, high in 2, and a very high level was not detected in patients with celiac disease. Evaluation of the dynamics of the constituent indicators of the level of neuroticism by the end of the course of therapy with afobazole in most cases revealed a significant improvement in the condition.

The values of the general level of neuroticism in the groups of patients with celiac disease statistically significantly exceeded the value of the normal level, which indicates the presence of characteristic personality disorders and psychosomatic maladaptation. Patients had affective disorders, expressed in a constantly present feeling of anger, anger, protest, internal tension. The therapeutic dynamics of pharmacocorrection was manifested by an increase in the background of mood, activity level, working capacity, a decrease in fatigue, a decrease in anxiety, irritability and emotional stress.

Data on the dynamics of the level of neuroticism in patients with celiac disease on the background of therapy are shown in fig. 3.

Discussion of results. In patients with celiac disease, anxiety, anxiety-phobic and asthenic disorders were observed, which was confirmed by the initial indicators of the studied scales. The mental state of the studied patients was determined by manifestations of constant internal tension, anxiety, fixation on the situation, their condition, emotional reactive lability with irritation reactions, difficulty concentrating, feeling tired, and a tendency to increased excitability. The results of treatment showed the therapeutic efficacy of afobazole

The results of treatment showed the therapeutic efficacy of afobazole

V Normal

E Very high

□ High

□ High

3. The level of neuroticism in patients with celiac disease on the background of a four-week course of treatment with afobazole.

for patients with celiac disease with anxiety and anxiety-phobic disorders and asthenic personality traits.

When analyzing the effectiveness of course therapy with afobazole, it was found that in patients with different individual typological characteristics, there is a positive therapeutic dynamics of the state according to the scales for assessing personal and situational anxiety and the level of neurotization. Thus, the drug is a highly effective anti-anxiety agent that reduces the severity of anxiety symptoms according to both objective and subjective assessment methods.

The action of afobazole is characterized by a positive effect equally on the mental and somatic components of anxiety. The problem of treating patients with celiac disease remains relevant. This is due to the impossibility of taking drugs for the correction of disorders by this category of patients due to the presence of gluten-containing components in them, provoking an exacerbation of the disease.

The problem of treating patients with celiac disease remains relevant. This is due to the impossibility of taking drugs for the correction of disorders by this category of patients due to the presence of gluten-containing components in them, provoking an exacerbation of the disease.

Taking into account the potential prospects for the use of the drug in general medical practice and the absence of gluten content, we consider it appropriate to use afobazole for the correction of psychosomatic disorders in patients with celiac disease.

Summary

Oreshko L.S. Psychological peculiarities of celiacia patients and their correction.

The therapeutic effectiveness of Afobasol application to the treatment of 17 patients with celiac disease with different individual typological traits is studied.

The results of treatment showed therapeutic efficacy of Afobasol application to the treatment of celiacia patients with anxious and anxious-fobical nervous disorders and asthenic traits of character.

Taking into account the potential perspective of application of this medicine in wide medical practice, afobasol usage for the correction of psychosomatic disorders of celiacia patients is considered to be reasonable.

Key words: celiac disease, Afobasol.

Literature

1. Avedisova AS Will there be an alternative to benzodiazepines? // Psychiatrist. and a psychopharmacologist. 2006. No. 2. S. 2-3.

2. Parfenov AI Celiac enteropathy // Enterology. M.: Triada-X, 2002. S. 380-413.

3. Starostina EG Generalized anxiety disorder and symptoms of anxiety in general medical practice // Rus. honey. magazine 2004. V. 12. No. 22. S. 2-7.

4. Novik AA, Ionova TI Study of the quality of life in gastroenterology // Guidelines for the study of quality of life in medicine. SPb., 2002. S. 157-168.

5.Khanin Yu. L. A brief guide to the use of the scale of reactive and personal anxiety G. D. Spielberger. L., 1976. S. 5-21.

6. Raygorodsky D. Ya. Practical psychodiagnostics. Methods and tests: Textbook. Samara: Bahram, 1998. 672 p.

Ya. Practical psychodiagnostics. Methods and tests: Textbook. Samara: Bahram, 1998. 672 p.

Accepted May 21, 2008

Gluten and anxiety: is there a link?

The term gluten refers to a group of proteins found in various grains, including wheat, rye and barley.

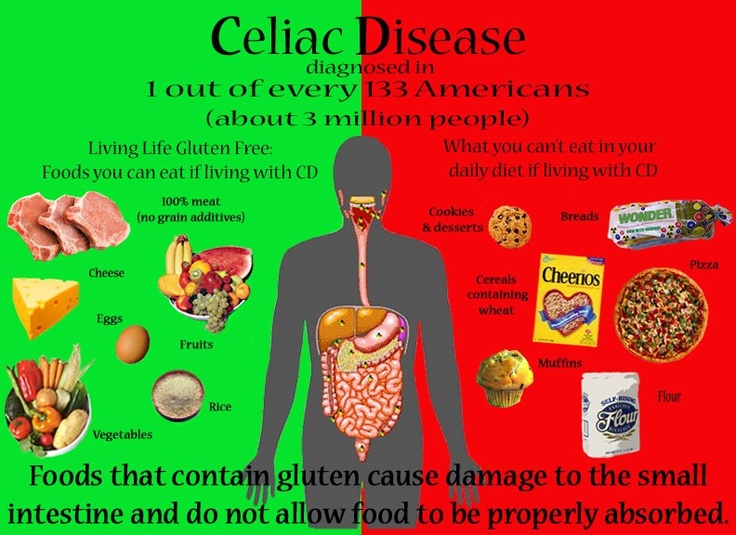

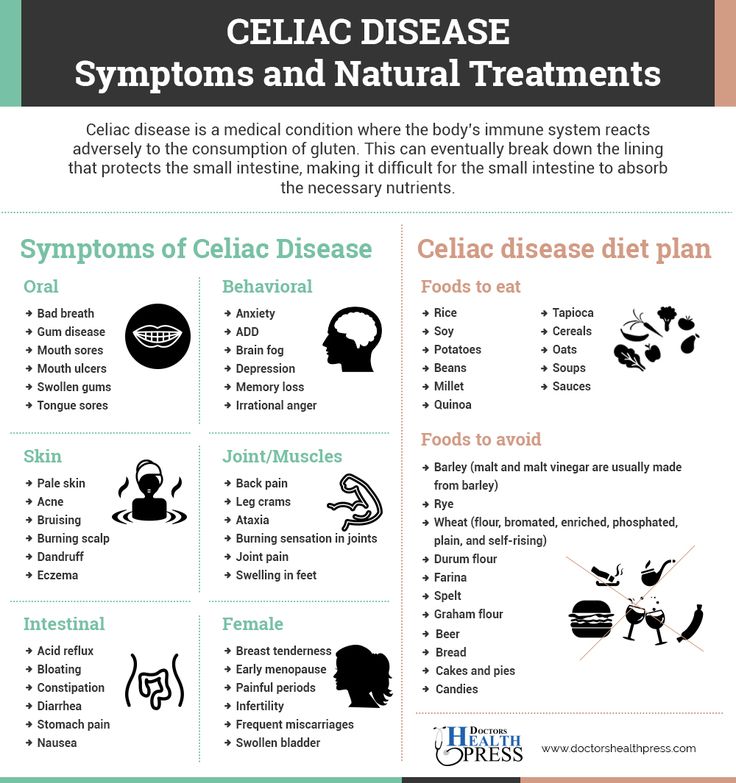

Although most people can tolerate gluten, it can cause a number of harmful side effects in people with celiac disease or gluten sensitivity.

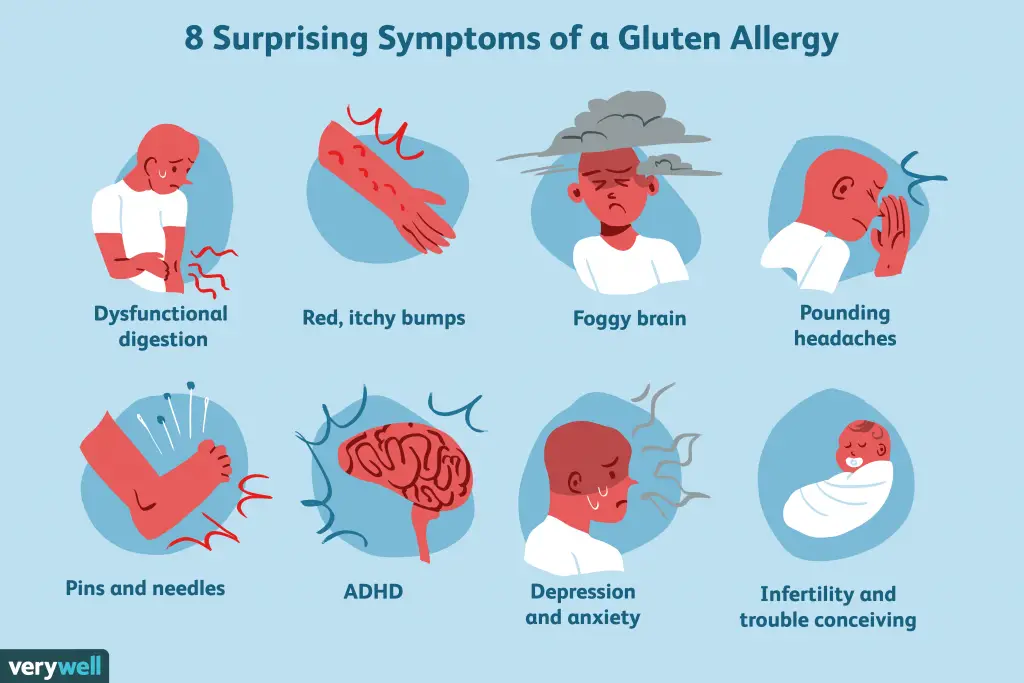

Some say that gluten not only causes indigestion, headaches, and skin problems, but it can also contribute to psychological symptoms such as anxiety (1).

This article discusses research in more detail to determine if gluten may be a concern.

Share on Pinterest

content

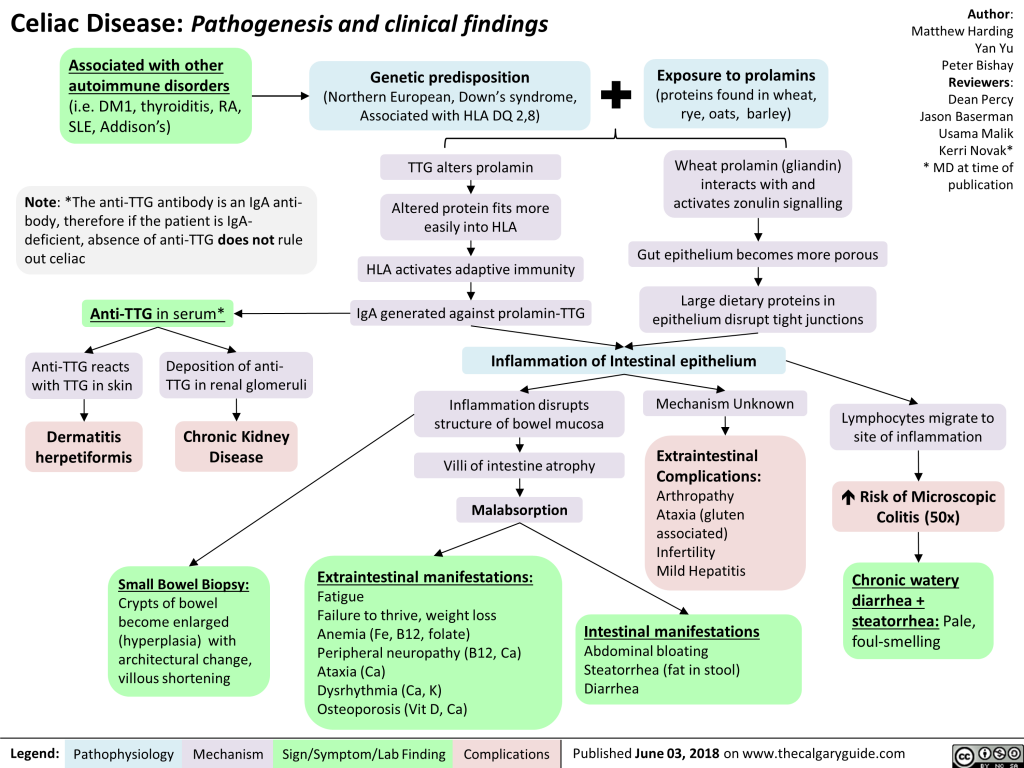

Celiac disease

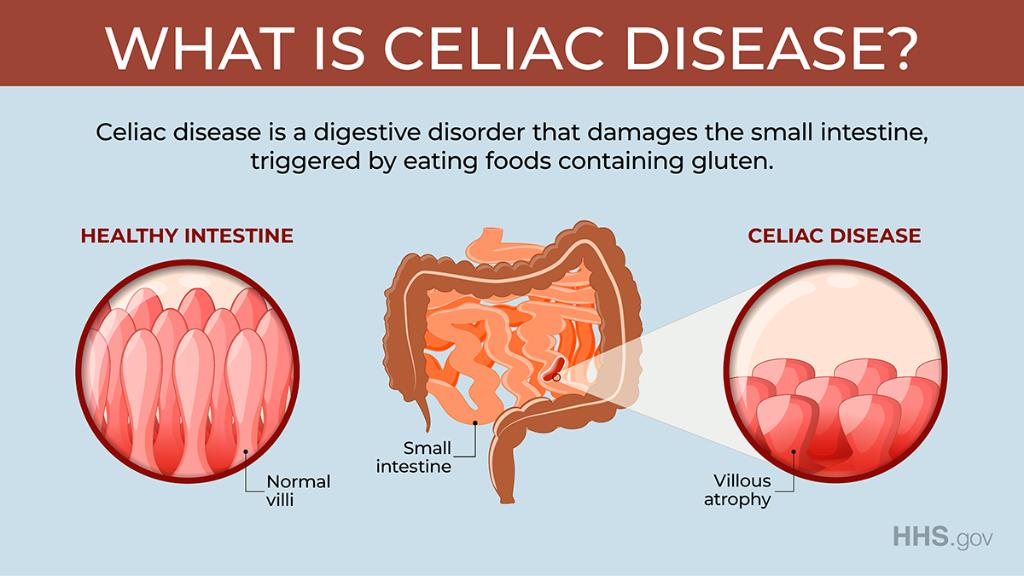

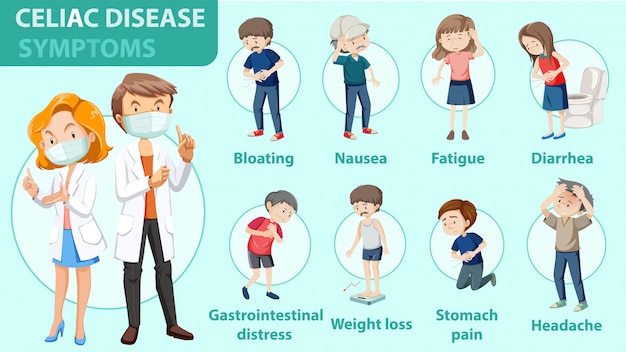

In patients with celiac disease, the consumption of gluten causes inflammation in the intestines, causing symptoms such as bloating, gas, diarrhea, and fatigue.2).

Some research suggests that celiac disease may be associated with a higher risk of certain psychiatric disorders, including anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. 3).

3).

A gluten-free diet can not only relieve symptoms of celiac disease, but also reduce anxiety.

In fact, a 2001 study showed that after a gluten-free diet for 1 year, anxiety decreased in 35 people with celiac disease.4).

Another small study of 20 people with celiac disease reported that participants experienced higher levels of anxiety before starting a gluten-free diet than after following it for 1 year.5).

However, conflicting results have been noted in other studies.

For example, one study found that women with celiac disease were more likely to have anxiety compared to the general population, even after completing a gluten-free diet.6).

Notably, homestay was also associated with a higher risk of anxiety disorders in the study, which may be related to the stress of buying and preparing meals for family members with and without celiac disease.6).

Moreover, a 2020 study of 283 people with celiac disease reported a high frequency of anxiety in people with celiac disease and found that following a gluten-free diet did not lead to a significant improvement in anxiety symptoms.

So while a gluten-free diet may reduce anxiety in some people with celiac disease, it may not reduce anxiety or even contribute to stress and anxiety in others.

More research is needed to evaluate the effect of a gluten-free diet on anxiety in people with celiac disease.

Gluten Sensitivity

People with gluten sensitivity to gluten may also experience harmful side effects from eating gluten, including symptoms such as fatigue, headaches, and muscle pain.7).

In some cases, people who are not sensitive to celiac disease may also experience psychological symptoms such as depression or anxiety.7).

While more qualitative research is needed, some studies suggest that removing gluten from the diet may be beneficial in these conditions.

In one study of 23 people, 13% of participants reported that their subjective anxiety decreased after a gluten-free diet (8).

Another study in 22 people with gluten sensitivity without celiac disease showed that eating gluten for 3 days resulted in increased feelings of depression compared to controls. 9).

9).

Although the cause of these symptoms is still unclear, some research suggests that the effect may be due to changes in the gut microbiome, a community of beneficial bacteria in the digestive tract that are involved in several aspects of health.10,11).

Unlike celiac disease or wheat allergy, there is no specific test used to diagnose gluten sensitivity.

However, if you experience anxiety, depression, or any other negative symptoms after eating gluten, consult your doctor to determine if a gluten-free diet is right for you.

Essence

Anxiety is often associated with celiac disease and gluten sensitivity.

Although studies have shown mixed results, several studies show that monitoring a gluten-free diet can help reduce anxiety symptoms in people with celiac disease or gluten sensitivity.

If you find that gluten is causing you anxiety or other harmful symptoms, consider talking to your healthcare provider to determine if gluten-free may be beneficial for your child.