Narcolepsy as a disability

Is Narcolepsy a Disability? Everything You Need to Know

A disability is defined as any condition that interferes with your capacity to do your job or other daily activities. The World Health Organization (WHO) lists three different dimensions to a disability:

- It impairs your body’s structure or function, such as losing your memory or vision.

- It limits movement, such as having trouble walking or seeing.

- It makes it hard to participate in daily activities, such as work or running errands.

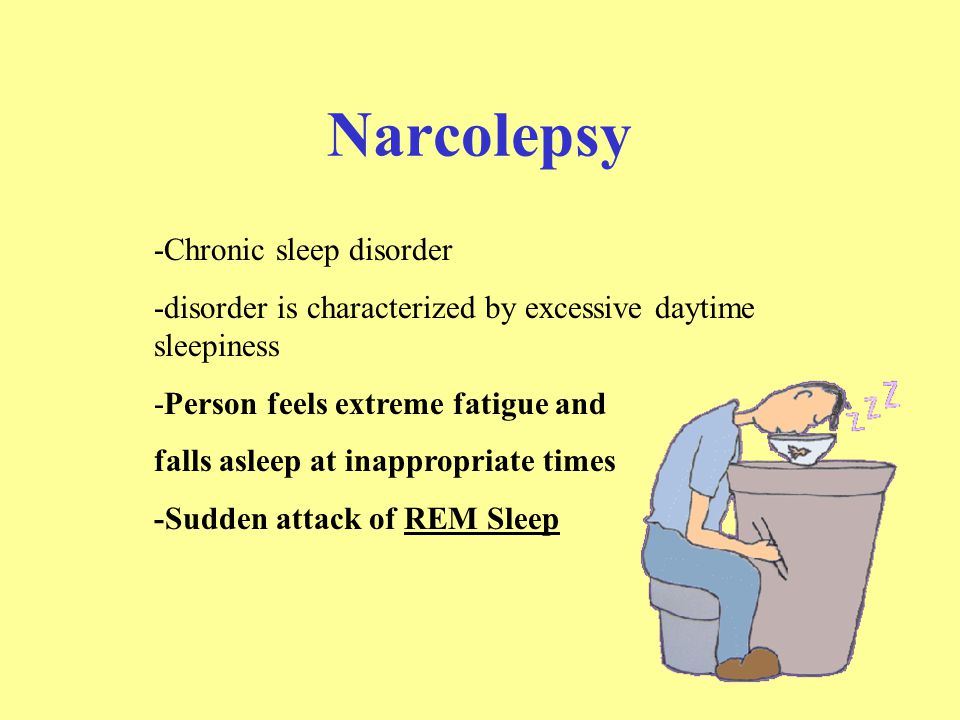

Narcolepsy causes symptoms that include severe daytime sleepiness and a sudden loss of muscle control. And for some people, it can create enough limitations to qualify as a disability.

Research like a 2016 study has found that people living with narcolepsy are more likely to be unemployed than people without this condition. People living with narcolepsy who are employed often miss work or can’t do their jobs well because of the disorder.

If you can’t work because you’re living with narcolepsy, you may be able to receive Social Security disability benefits. The first step is to find out whether your symptoms qualify you for these payments.

Narcolepsy can meet the criteria for a disability in certain circumstances.

The extreme daytime sleepiness and sudden loss of muscle control that may come with narcolepsy can make it difficult to work. Some people even fall asleep without warning during the day.

These symptoms make certain jobs, including those that involve driving or operating heavy machinery, very dangerous.

People with a disability that limits their ability to work may be able to get Social Security disability benefits.

Narcolepsy isn’t on the Social Security Administration’s (SSA’s) list of qualified disorders. But if you get frequent bouts of sleep attacks, you may still be able to get benefits.

First, you’ll need to meet these criteria:

- You have at least one episode of narcolepsy each week.

- You’ve been on treatment for at least 3 months and you still have symptoms.

- Your condition has a significant impact on your ability to perform daily activities such as driving or following directions.

To qualify for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), you must have worked for a certain period of time before you became disabled.

In general, you’ll need to have worked for the last 5 out of the past 10 years; however, the requirement is shorter if you’ve worked for fewer than 10 years.

The sooner you apply for disability benefits, the better. It can take 3 to 5 months for the SSA to process your claim.

Before you apply, make sure that you have all the medical information the SSA will need from you. This includes:

- your diagnosis

- when your condition started

- the tests your doctor used to make your diagnosis, including EEGs, lab tests, and sleep studies

- your symptoms and how often you have them

- the list of medications you take and how they affect your symptoms

- a letter from the doctor who treats you stating how narcolepsy symptoms affect your ability to work, including walking, lifting, sitting, and remembering instructions

Your doctor can help you pull this information together.

If your claim is denied, you can appeal it. You have 60 days from the date on the denial notice to file an appeal. Note that there’s a good chance your first appeal will be denied — most claims don’t get approved on the first try.

If your appeal is denied, the next step is to have a hearing before a judge. Hiring a disability lawyer can increase your odds of having a successful outcome at the hearing.

If you still don’t get approval for disability benefits, consider asking your employer for accommodations. Under the Americans with Disabilities Act, many companies are required to make changes that help their employees with disabilities do their jobs.

You might ask to adjust your work hours so you can sleep later. Or you could request frequent breaks during the day to take naps. Talk with your company’s human resources manager to find out what accommodations are available to you.

You can apply for Social Security disability in one of three ways:

- in-person at your local Social Security office

- online through the SSA website

- by calling 800-772-1213

In addition to getting help from your doctor, you can seek assistance from the following resources:

- a Social Security lawyer

- a disability starter kit from the SSA

- American Association of People with Disabilities

- National Council on Disability

- The International Center for Disability Resources on the Internet

Narcolepsy isn’t one of the conditions the SSA considers a disability. But if your symptoms interfere with your ability to do your job, you may still qualify for benefits.

But if your symptoms interfere with your ability to do your job, you may still qualify for benefits.

The Disability Benefits Help website offers a free evaluation to help you determine whether your condition is considered a disability.

Start by having a conversation with your doctor. Gather all of your medical information. Then, if possible, hire a lawyer to help steer you through the process.

If you can’t afford a lawyer, don’t worry — disability lawyers work on a contingency basis. That means your lawyer won’t get paid unless you win your claim. At that point, they’ll get a percentage of the back pay you’re awarded.

Is Narcolepsy a Disability under U.S. Law?

Excessive sleepiness caused by narcolepsy can make everyday life challenging. But there are legal protections in place to help.

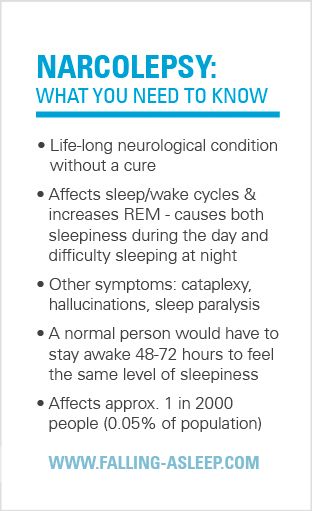

Narcolepsy is a chronic neurological condition that affects the body’s sleep-wake cycle. Though symptoms can vary from person to person, they can have a profound impact on everyday life.

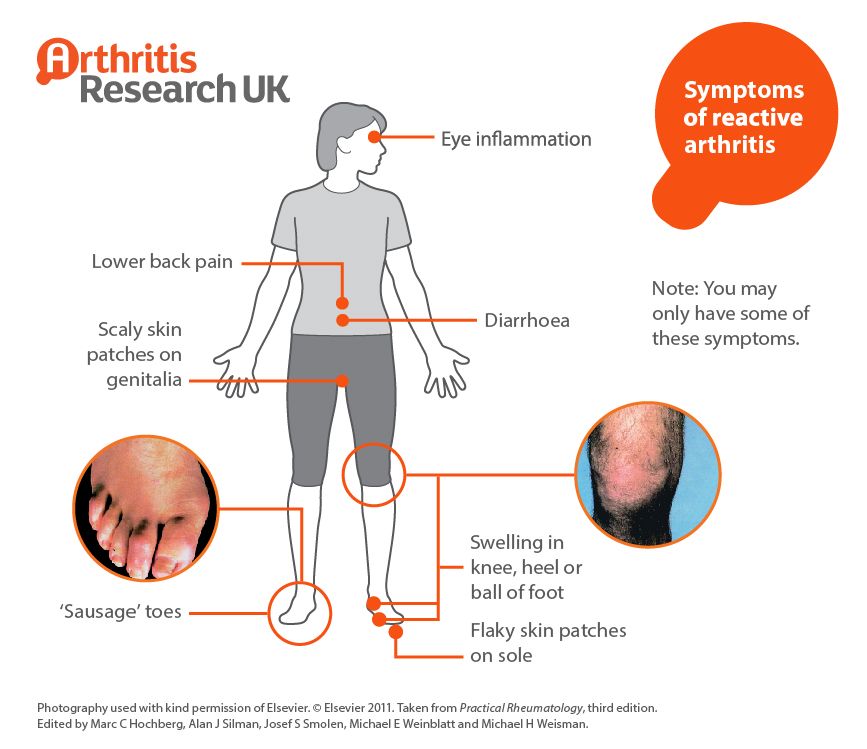

The most common symptoms of narcolepsy include:

- excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS)

- cataplexy (a sudden loss of muscle control)

- sleep paralysis, which can sometimes be accompanied by hallucinations

It’s important to note that less than a quarter of those with narcolepsy typically experience all four of these symptoms, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. There’s a lot of variation in how this condition manifests, which can sometimes create limitations in qualifying as a disability for some.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) define a disability as any condition of the body or mind that makes it more difficult for a person to perform or participate in certain activities.

Narcolepsy exists on a spectrum, so those who live with the condition often experience different levels of limitation. But for some people, narcolepsy impacts their life enough to qualify as a disability.

Narcolepsy can be considered both a physical and mental disability since it affects both the body and the mind. It causes mental changes, including excessive daytime sleepiness and a loss of concentration. Other symptoms are primarily physical, like:

It causes mental changes, including excessive daytime sleepiness and a loss of concentration. Other symptoms are primarily physical, like:

- episodes of sudden sleepiness

- cataplexy

- sleep paralysis

Some people with the condition also experience “automatic behaviors,” meaning that they fall asleep during an activity, and continue the activity without being aware of what they’re doing. Their performance is usually impaired, which can be dangerous if they’re in the middle of an activity like driving.

All these symptoms can make everyday life more challenging for a person with narcolepsy.

Yes, narcolepsy is a condition covered by the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act.

The ADA forbids employment discrimination on the basis of disability. To be protected by the ADA, a person must have a physical or mental disability that substantially limits at least one major life activity.

Because narcolepsy can cause excessive daytime sleepiness and sudden loss of muscle control, this condition may make it challenging for some people to perform job duties. Certain types of work may be dangerous for people with narcolepsy, particularly those that involve driving or operating machinery.

Certain types of work may be dangerous for people with narcolepsy, particularly those that involve driving or operating machinery.

In a 2019 legal case regarding the termination of an employee in Alabama, the court explicitly stated that narcolepsy is a covered disability. The court noted that narcolepsy is a physical impairment that can substantially limit major life activities — in this case, the plaintiff’s ability to do his job — and therefore qualified as a disability under the ADA.

Narcolepsy is not on the SSA’s list of qualified disorders. But if the condition affects their ability to work, a person with narcolepsy may still qualify for Social Security benefits.

Qualifications

Although there is no listing for the condition itself, SSA claims for narcolepsy are sometimes assessed under the same criteria as nonconvulsive epilepsy. If a person’s narcolepsy causes frequent sleeping episodes, they may qualify under this criteria.

To qualify, you must prove that:

- You have at least one narcolepsy episode a week.

- You’re still having symptoms despite having received treatment for at least 3 months.

- Your condition has severely inhibited your ability to carry out day-to-day activities.

To qualify, you’ll need to provide evidence of your condition, including as much medical information as possible. Your doctor can help you gather this information. Details that the SSA may ask for include:

- your clinical diagnosis

- the date when symptoms began

- what diagnostic tests your doctor used to diagnose you

- what symptoms you experience and how often they occur

- any medications you take for your condition, their impact on your symptoms, and any side effects

It’s also helpful to have a letter from your doctor outlining how your condition affects your ability to work.

What if my claim is denied?

If your claim is denied, don’t be discouraged. You have 60 days after the notice of denial to appeal. And if your appeal is denied, you’re also entitled to a hearing before a judge.

Hiring a Social Security lawyer may be a good idea at this stage. Most attorneys who handle these types of cases work on a contingency basis, meaning they will not be paid unless they win your case.

Even if your application for SSA benefits isn’t approved, keep in mind that your condition is still protected under the ADA. That means that you may be able to ask your employer for accommodations.

Reasonable accommodations

Under the ADA, employers are required to make “reasonable accommodations” to allow folks with disabilities to successfully perform their job. There are three main areas where accommodations are required, including:

- enduring equal opportunity during the hiring process

- enabling any qualified person with a disability to perform their job functions

- allowing any employee with a disability to enjoy the same benefits and privileges of employment as a person without a disability

Specific accommodations will vary, depending on:

- the nature of your work

- where you work

- other factors

For a person with narcolepsy, an example of a reasonable accommodation might be your employer working with you to create a flexible schedule allowing for potentially unpredictable sleep patterns.

It may be a good idea to speak with your company’s human resources manager to find out what accommodations are already available.

Living with narcolepsy can present a number of challenges. Excessive sleepiness, sudden muscle weakness, and unpredictable bouts of daytime sleeping can make everyday tasks more difficult.

However, know that there are many legal resources available that can help you if you have narcolepsy or are supporting a loved one with the condition.

Narcolepsy is a recognized and protected disability under the ADA. This means that employers are required to make reasonable accommodations to support you in performing your job duties.

In some cases, narcolepsy may qualify you for Social Security benefits. Whether you qualify depends on:

- your specific symptoms

- severity

- how your participation in daily activities is impacted

To learn more about your disability rights, consider checking out online resources like:

- American Association of People with Disabilities

- National Council on Disability

- Americans with Disabilities Act: A Guide to Disability Rights Law

- National Disability Rights Network

Dealing with narcolepsy can be an isolating experience, but you don’t have to go it alone. To connect with others, you can find in-person and virtual support groups via the Narcolepsy Network. The Narcolepsy 360 podcast can also offer guidance on everyday life with the condition from those who live with it.

To connect with others, you can find in-person and virtual support groups via the Narcolepsy Network. The Narcolepsy 360 podcast can also offer guidance on everyday life with the condition from those who live with it.

Is narcolepsy a disability? - Drink-Drink

A disability is defined as any condition that interferes with your ability to do your job or do other daily activities. The World Health Organization (WHO) lists three different aspects of disability:

- It impairs the structure or function of your body, such as losing your memory or vision.

- This restricts movement, such as problems with walking or vision. nine0006

- This makes it difficult to participate in daily activities such as work or running errands.

Narcolepsy causes symptoms such as severe daytime sleepiness and sudden loss of muscle control. And for some people, this can create enough restrictions to qualify as a disability.

Research like the 2016 study found that people living with narcolepsy are more likely to be unemployed than people without the condition. Working people with narcolepsy often miss work or are unable to do their jobs well due to the disorder. nine0003

Working people with narcolepsy often miss work or are unable to do their jobs well due to the disorder. nine0003

If you can't work because you have narcolepsy, you can get Social Security disability benefits. The first step is to find out if your symptoms qualify for these payments.

Is narcolepsy a disability?

Narcolepsy may qualify for disability under certain circumstances.

Extreme daytime sleepiness and sudden loss of muscle control, which may be accompanied by narcolepsy, can make work difficult. Some people even fall asleep unannounced during the day. nine0003

These symptoms make certain jobs, including driving or operating heavy machinery, very dangerous.

People with a disability that limits their ability to work may be eligible for Social Security disability benefits.

Narcolepsy is not on the SSA's list of qualified disorders. But if you have frequent bouts of sleep, you may still benefit.

First, you need to meet the following criteria:

- You have at least one episode of narcolepsy every week.

- You have been treated for at least 3 months and still have symptoms.

- Your condition has a significant impact on your ability to perform everyday activities such as driving or following directions.

To be eligible for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), you must work for a certain period of time before becoming disabled. nine0003

As a general rule, you need to work the last 5 of the last 10 years; however, the requirement is shorter if you have been employed for less than 10 years.

Tips for applying for disability benefits

The sooner you apply for disability benefits, the better. It may take 3 to 5 months to process your SSA application.

Before you apply, make sure you have all the health information SSA will need from you. This includes:

- your diagnosis

- when your condition began

- tests your doctor used to make the diagnosis, including EEG, lab tests, and sleep tests

- your symptoms and how often you have them

- a list of medications you take , and how they affect your symptoms

- a letter from your doctor stating how the symptoms of narcolepsy affect your ability to work, including walking, lifting weights, sitting, and remembering instructions

Your doctor can help you put this information together.

If your claim is denied, you can appeal it. You have 60 days from the date of the denial notice to file an appeal. Please note that there is a good chance that your first appeal will be rejected - most applications are not approved on the first try.

If your appeal is denied, the next step is to have a hearing before a judge. Hiring a disability lawyer can increase your chances of a successful hearing. nine0003

If you are still not approved for disability benefits, consider asking your employer for accommodations. Many companies are required by the Americans with Disabilities Act to make changes that help their employees with disabilities do their jobs.

You can ask to adjust the opening hours so that you can sleep later. Or you can request frequent breaks during the day to take a nap. Talk to your company's HR manager to find out what accommodation options are available to you. nine0003

Resources to help you apply

You can apply for Disability Assistance in one of three ways:

- in person at your local Social Security office

- online through the SSA website

- by calling 800-772 -1213

In addition to getting help from your doctor, you can get help from the following resources:

- Social Security Lawyer

- SSA Starter Kit for the Disabled

- American Disability Association

- National Council on Disability

- International Disability Resource Center Online

Conclusion

Narcolepsy is not one of the conditions that the SSA considers a disability. But if your symptoms are preventing you from doing your job, you can still qualify for benefits.

The Disability Benefits Help website offers a free assessment to help you determine if your condition is considered a disability. nine0003

Start by talking to your doctor. Gather all your medical information. Then, if possible, hire a lawyer to help you through the process.

If you can't afford a lawyer, don't worry—disability lawyers are available for contingencies. This means that your lawyer will not be paid if you do not win your lawsuit. At that point, they will receive a percentage of the debt awarded to you.

Not just sleepiness. How to live with narcolepsy and why there is still no cure for it - Knife

At one of my first jobs, I stood on a lion's nibble. There are activities that are not suitable for a person with narcolepsy, and this is probably one of them. I was 22, recently graduated from the Faculty of Zoology and studied meerkats in the Kalahari Desert in South Africa. My colleague and I worked in pairs: one on the move walking with meerkats, and the other in a jeep scanning the horizon for the danger of a lion. Many times I woke up with a steering wheel imprint on my forehead and the realization that I had overlooked a colleague and meerkats. I searched the surrounding landscape for signs of life, and as the panic grew, for signs of death. Now I can tell this story only because no one was devoured after all. nine0003

My colleague and I worked in pairs: one on the move walking with meerkats, and the other in a jeep scanning the horizon for the danger of a lion. Many times I woke up with a steering wheel imprint on my forehead and the realization that I had overlooked a colleague and meerkats. I searched the surrounding landscape for signs of life, and as the panic grew, for signs of death. Now I can tell this story only because no one was devoured after all. nine0003

I wasn't always like this. I slept well for the first twenty years of my life, but shortly after my 21st birthday, I began to experience symptoms of narcolepsy, a rare (but not uncommon) disorder that affects about one in 2,500 people.

that the sufferer experiences frequent bouts of uncontrollable drowsiness. This is true, but the disease is much more serious: it is often accompanied by cataplexy (a condition where strong emotions cause loss of muscle tone and the person falls like a rag doll), psychedelic dreams, sleep paralysis and frightening hallucinations.

nine0118

nine0118 No medicine. Bye.

In the Kalahari in 1995, these symptoms were new to me. I didn't realize the damage the endless struggle with sleep would do to my body and mind. I was not alone in my ignorance. Few family doctors have heard of this disorder, let alone seen even one patient live. Some neurologists knew what to look for, but many did not. Even sleep experts could not explain why I suddenly had this condition.

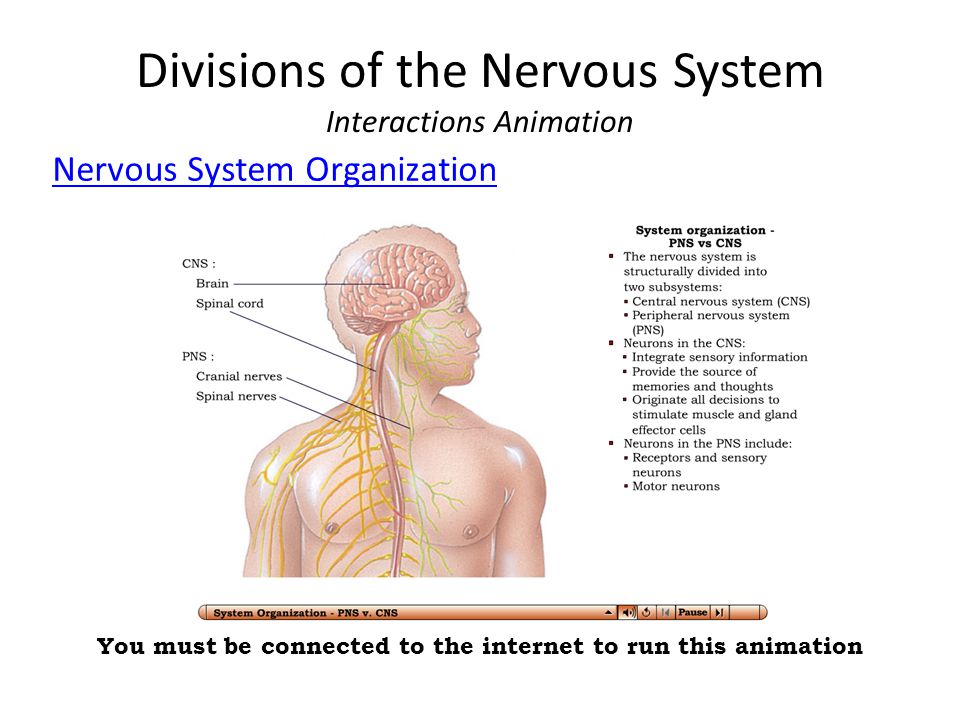

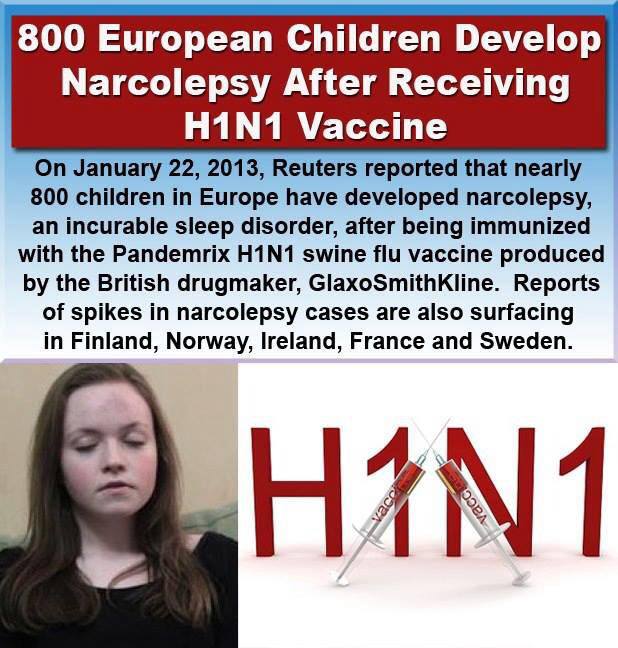

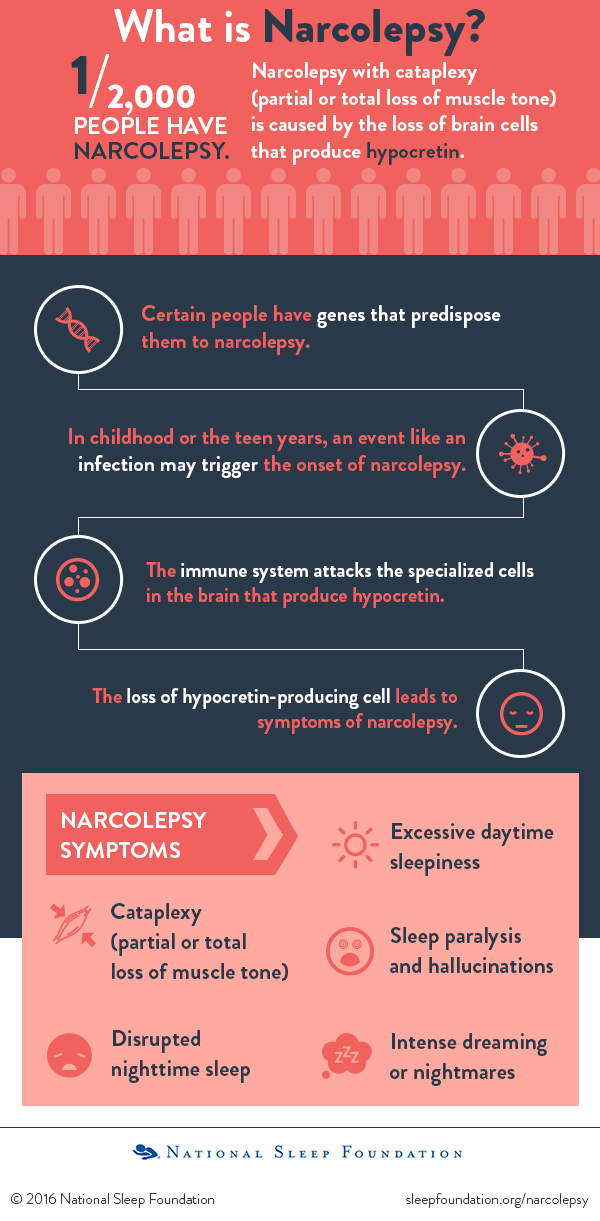

A lot has changed since then. Evidence is mounting that the most common cause of narcolepsy is an autoimmune malfunction, in which the immune system misinterprets an upper respiratory tract infection and mistakenly clears out about 30,000 neurons in the center of the brain.

The brain is made up of 100 billion cells, and there doesn't seem to be much to worry about.

But these are not simple cells, these are cells of the hypothalamus, a small, evolutionarily ancient, and incredibly important device that helps regulate many basic body functions, including the daily swing between sleep and wakefulness.

nine0118

nine0118 They are also the only cells in the brain that synthesize orexins (also known as hypocretins).

This pair of peptides—short chain amino acids—was unknown to science at the time of my diagnosis in 1995. The story of their discovery, which began in the 1970s, is a beautiful parable of luck and luck, fantasy and foresight, risk and rivalry, and besides, it features a colony of narcoleptic Dobermans.

There are medications now available to help manage the worst symptom of narcolepsy, but none come close to correcting the underlying brain damage. The answer to my problems seems simple - I just need to put orexins (or something equivalent) in my brain. So why am I still waiting for my cure to be invented? nine0003

In 1972, a poodle puppy was born in Canada, he was named Monique. When Monique tried to play, she suddenly suddenly fell. It didn't feel like sleep, more like partial paralysis. Veterinarians suspected narcolepsy with symptoms of cataplexy. Monique was moved to California, where she was studied by sleep specialist and Stanford University professor William Dement. Word began to spread, and soon Dement and his colleague Merrill Mitler were watching not only Monique, but several other dogs as well. nine0003

Word began to spread, and soon Dement and his colleague Merrill Mitler were watching not only Monique, but several other dogs as well. nine0003

The fact that narcolepsy was more common in certain dog breeds suggested that there was a genetic basis for the disorder.

Then the breakthrough came: Dement was informed of a Doberman litter of seven puppies, all with narcolepsy and cataplexy. “During the first day, each of the puppies collapsed to the ground once,” says Mitler.

It turned out that the disease was inherited in Labradors and Dobermans. Dement decided to focus on Dobermans, and by the end of the 70s he was already the proud owner of an entire colony of dogs of this breed. He established that narcolepsy in Dobermans is caused by the transmission of a single recessive gene. By the 1980s, genetic analysis methods had advanced enough to try to track down the defective Doberman gene. nine0003

I will never be able to reconstruct the combination of factors that led to my narcolepsy, but the main thing happened at the moment of my conception in 1972 - around the same time Monique was born in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. I have inherited a special version of a gene (known as HLA-DQB1*0602) that is involved in a process that helps the immune system distinguish friend from foe.

I have inherited a special version of a gene (known as HLA-DQB1*0602) that is involved in a process that helps the immune system distinguish friend from foe.

The HLA-DQB1*0602 gene is quite common - about one in four Europeans can boast a copy - and it plays a key role in many cases of narcolepsy and is present in about 98% of patients with narcolepsy and cataplexy.

In addition to genetics, time also seems to play a role. People with narcolepsy are often born in March (like me). This "birth effect" is also seen in other autoimmune disorders and is likely due to seasonal infections. In the case of narcolepsy, apparently those born in March are just a little more vulnerable than everyone else.

Although other childhood infections, hormonal imbalances and stress may also have contributed, I encountered a key pathogen in late 1993 years old - I was overtaken by the flu virus or possibly a strep infection. It was an autoimmune tipping point that resulted in the rapid destruction of my orexin system. In short, most cases of narcolepsy are the result of an unfortunate set of circumstances that created the ninth immunological wave, the perfect storm.

In short, most cases of narcolepsy are the result of an unfortunate set of circumstances that created the ninth immunological wave, the perfect storm.

Around this time, the Doberman project at Stanford was close to solving the mystery of narcolepsy in this breed. The mutation was hunted down by Emmanuel Mignot, who later succeeded Dement as director of the Stanford Sleep Center. We meet in his office, Mignota accompanies Watson, a narcoleptic chihuahua. “Such a stupid breed,” he says. “I would never choose such a dog for myself.” nine0003

At first, Watson is wary of me, keeping his distance. I get down on the floor, he yips and jumps at me, pretending that he is angrier than he is.

I feel empathy, even though his view is an abyss from mine. I know what severe daytime sleepiness is. I know what cataplexy is, I know what it's like when emotions short circuit the neurological network in the brain stem and cause muscle collapse (this happens in REM sleep, that's when we dream most often).

I wonder if Watson is afraid of sleep paralysis and the supernatural hallucinations that often accompany sleep paralysis. The dog's eyelids close and then open again, and I recognize the lethargy in his gaze. He climbs into the basket and curled up asleep during the entire interview.

In the 1980s, the idea of finding the gene responsible for canine narcolepsy seemed extremely ambitious. Breeding narcoleptic Dobermans is a more difficult task than it seems at first glance, since such dogs can fall in the middle of intercourse, temporarily paralyzed by cataplectic trembling (the so-called orgasmolepsy, also happens in humans). And even without taking into account this inconvenience, it was necessary to find a gene whose sequence is unknown in the genome, which at that time was not studied. “Most people said I was crazy,” Mignot recalls. In a way, they were right: it took him over ten years, hundreds of dogs, and over a million dollars. And he almost got ahead of himself. nine0003

nine0003

In January 1998, just as Mignot's team was approaching the finish line, young neurologist Luis de Lecea of the Scripps Institute for Research in San Diego published a paper describing two new brain peptides. De Lecea and his colleagues named them hypocretins, from the hypothalamus where they were found, and from the word secretin, a hormone with a similar structure. These were chemical mediators that functioned exclusively within the brain.

A few weeks later, a team of scientists led by Masashi Yanagisawa from the University of Texas, independently of de Lecea and his colleagues, described the same peptides, but called them orexins, and also presented the structure of their receptors. They hypothesized that the interaction of these proteins with receptors could influence appetite regulation. “We didn’t think about sleep at all,” admits Yanagisawa. nine0003

At Stanford, Mignot learned about the publication of two papers, but there was no reason to believe that the discovery had anything to do with narcolepsy or sleep. However, by the spring of 1999, he and his team figured out that the recessive mutation must lie in one of the two genes. One is expressed in the foreskin. "It didn't look like a candidate for narcolepsy," Mignot says. There was a second gene that encoded one of the two orexin receptors. When he learned that Yanagisawa's team had created an orexin-free mouse, and that mouse was now showing symptoms of narcolepsy, the race was on. nine0003

However, by the spring of 1999, he and his team figured out that the recessive mutation must lie in one of the two genes. One is expressed in the foreskin. "It didn't look like a candidate for narcolepsy," Mignot says. There was a second gene that encoded one of the two orexin receptors. When he learned that Yanagisawa's team had created an orexin-free mouse, and that mouse was now showing symptoms of narcolepsy, the race was on. nine0003

A few weeks later, Mignot and his colleagues published their work in the journal Cell, where they talked about a defect in the gene encoding one of the orexin receptors. "This result suggests that hypocretins (orexins) are important sleep-influencing neurotransmitters, which opens the prospect of new approaches to the treatment of patients with narcolepsy," they wrote. Kalua, one of a litter of Dobermans named after spirits, lies lounging on the cover of the publication. Yanagisawa and colleagues published the results of their experiments two weeks later, also in the journal Cell. nine0003

nine0003

Under normal circumstances, the chemical transmitter and its receptor work like a key and a lock. The key (transmitter) goes to the lock (receptor) to open the door (cause a change in the target cell). In the case of Mignot Dobermans, a large-scale mutation messed up the orexin receptor lock, rendering the orexin useless.

Either the lock does not work, as in this case, or there are no keys, as in the case of the Yanagisawa mice, but the outcome is the same - the door will not open. The orexin system is out of order. In the case of humans, there are many ways to break the orexin system. Sometimes the damage is caused by a brain tumor or a head injury. In most cases, however, narcolepsy is caused by an unfortunate set of circumstances, as described above. nine0003

Orexin neurons are a very important thing, and not only for those who have lost them. Almost all major classes of vertebrates have them and perform a very important function. When de Lecea first described orexins in 1998, he was not yet thirty and had just arrived from Barcelona to San Diego. In 2006, he moved to Stanford to be closer to the science of sleep. “To be honest, I thought that now we will understand the system much better than we eventually understand it,” he says.

In 2006, he moved to Stanford to be closer to the science of sleep. “To be honest, I thought that now we will understand the system much better than we eventually understand it,” he says.

However, much has been learned, especially thanks to optogenetics. By introducing a virus, a promoter, and a gene from blue-green algae, it is possible to identify a specific group of light-sensitive neurons. nine0003

To illustrate this magic, de Lecea shows a video on his laptop. In the video, we see a mouse that has been genetically programmed to fire its orexin neurons in response to light. A thin fiber optic wire is led to the mouse brain. "The mouse is sleeping," he says, and at the top of the screen we see waves of electrical activity characteristic of deep sleep. The wire comes to life, a bluish flash lasts ten seconds. Light-sensitive orexin neurons release neuropeptides and suddenly the rodent wakes up. When the light is turned off, the mouse falls asleep as quickly as it woke up. nine0003

nine0003

Suddenly my tear ducts tingle, and for a fraction of a second I almost envy this mouse.

Using optogenetics and other methods, de Lecea was able to prove that orexins play an important role in many neurological networks. Sometimes they function as neurotransmitters and help neurons release norepinephrine into the cerebral cortex. In other cases, orexins act more like hormones. This is how orexins affect other chemicals in the brain, including dopamine (which plays a key role in the reward system, in planning and motivation), serotonin (strongly associated with mood and involved in depression), and histamine (an important warning signal). nine0003

“Most other neural networks have parallel and multiple layers of security,” de Lecea says. “So if something goes wrong, other systems turn on and take over. In the case of orexins, however, there is little or no safety net.

That is, manipulating this system gives a clear response that scientists can work with. This is an excellent model for understanding how neural networks work in a more general sense.”

This is an excellent model for understanding how neural networks work in a more general sense.”

What we now know about orexins also helps to explain why the loss of just a few tens of thousands of cells can lead to such a serious multi-symptom disease as narcolepsy, which affects wakefulness and sleep, body temperature, metabolism, appetite, motivation and mood. These proteins give us an exceptional insight into how the human brain works. nine0003

And that turns the orexin story into an archetypal double helix tale, and a great illustration of how science works. There is a mystery (narcolepsy), a primordial story (Monique), foresight (Dement), aspiration (Mignot), technological discoveries (genetics), a photogenic animal (Dobermans), a race (with Yanagisawa), looks like science (optogenetics), and yet has high goal (sleep and brain).

It's elements like these that can turn current scientific events into compelling cultural narratives, says Stephen Kasper, a neuroscience historian at Clarkson University in New York. “Here are all the ingredients for what physiologists and neurologists at the beginning of the 20th century were looking for and hoped to find - something that would unite heredity, biochemistry, biophysics, neurology and psychology.” nine0003

“Here are all the ingredients for what physiologists and neurologists at the beginning of the 20th century were looking for and hoped to find - something that would unite heredity, biochemistry, biophysics, neurology and psychology.” nine0003

“However, there is a tendency in biochemical studies of niche disorders that they are often promising, but never help the patients themselves,” Kasper adds. Something is missing in the narrative around narcolepsy, he says: “A good story should have a clear happy ending.”

We are still waiting for that happy ending.

Even if I can get a bottle of orexin-A and orexin-B, how can I put them in my brain? If I swallowed them in solution, the enzymes in my intestines quickly dealt with them, plucking the amino acids like beads off a necklace. If you inject into a muscle or blood vessel, only a few will pass blood-brain barrier .

There have been experiments with nasal delivery - it has been suggested that inhaling orexins might be a way to smuggle some of them into the hypothalamus via the olfactory nerve, but no one has made much investment in this approach.

This does not mean that the pharmaceutical industry has ignored the discovery of orexins. Not at all. Fifteen years after Mignot's publication, Merck received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration to market the drug suvorexant (commercial name Belsomra). The substance crosses the blood-brain barrier and blocks orexin receptors. And it is sleeping pills. nine0003

Sleeping pills are not exactly what people with narcolepsy needed. By preventing orexins from binding to receptors, the drug provides a completely narcoleptic onset - but the fog from it dissipates in the morning. Sleeping pills, commonly used to treat insomnia, depress the nervous system as a whole, says Paul Coleman, a chemist at Merck's Philadelphia lab. “Suvorexant differs in that it very selectively blocks wakefulness without affecting systems that control balance, memory, and thought processes,” he says. nine0003

Coleman developed drugs to treat a number of different infections, diseases, and disorders, but the orexin system stands apart. “Narcolepsy has given us a thread that we can pull and unravel the tangle of knowledge about what is behind the system that controls sleep and wakefulness,” says the chemist. “Waking is a pretty key process for all of us, whether you are healthy or have insomnia or narcolepsy. It's the most interesting thing I've ever worked on."

“Narcolepsy has given us a thread that we can pull and unravel the tangle of knowledge about what is behind the system that controls sleep and wakefulness,” says the chemist. “Waking is a pretty key process for all of us, whether you are healthy or have insomnia or narcolepsy. It's the most interesting thing I've ever worked on."

The use of suvorexant could be scaled up, with clinical trials planned for its ability to provide quality daytime sleep for shift workers, improve sleep in Alzheimer's patients, help those suffering from post-traumatic disorder and drug addiction, and alleviate the symptoms of panic disorder. nine0118

I'm glad to see this news, but we, millions of people with narcolepsy, are still waiting for a drug that will shake up rather than subdue the orexin system.

Masashi Yanagisawa has been working on this for a long time, who competed with Mignot 20 years ago to link orexins to narcolepsy. But designing and synthesizing a substance that will pass intact through the gut—which is exactly what it takes to get it from the blood to the brain—and that has the perfect configuration to activate one or both of the orexin receptors—“is a very, very big challenge,” he says. This is "significantly" more difficult than finding a compound that inhibits the receptor, as suvorexant does. nine0003

This is "significantly" more difficult than finding a compound that inhibits the receptor, as suvorexant does. nine0003

Earlier this year, Yanagisawa and his colleagues published data on the most powerful such compound to date, the small molecule YNT-185. The introduction of this molecule into narcoleptic mice significantly improves their wakefulness and reduces the excess of REM sleep (this is one of the characteristics of narcolepsy). And while the affinity of YNT-185 (how strongly it binds to the orexin receptor) is not enough to warrant clinical trials, Yanagisawa's team has already identified a number of other potential candidates. “The best of them is almost a thousand times stronger than YNT-185,” he boasts. Although the symptoms of narcolepsy can vary widely from person to person, the underlying pathology—the absence of orexins—remains the same. “If this compound works, it will work for all patients. In that sense, it will be a relatively simple clinical trial compared to many other disorders,” says Yanagisawa. nine0003

nine0003

An even more futuristic perspective involves stem cells.

Sergiu Pasca shares an office with Emmanuel Mignot at Stanford, and in 2015 he and colleagues developed a way to take induced pluripotent stem cells made from skin cells and send them to a new life as brain cells.

In theory, an orexin neuron could be grown and transplanted into the brains of people with narcolepsy. However, everything is not so simple. Firstly, it is unlikely that the cells themselves will be exactly the same as orexin cells, secondly, the introduction of a needle into the brain is a risk, and thirdly, there is always a chance that the immune system will make another attack - now on transplanted cells. nine0003

So, will the orexin tale have a happy ending? Translating basic research into clinics is difficult and expensive, Kasper notes.

The cost of the optimally available drug for narcolepsy - sodium oxybutyrate - is such that not every patient can afford it, although the drug is one of those that can qualitatively change the lives of many people.

It is widely believed that narcolepsy is a rare disorder with a small market, so any pharmaceutical research and development in this area is unlikely to generate significant revenue. This view ignores the fact that narcolepsy is likely to be undiagnosed for many people, and that a person who develops narcolepsy as a teenager and lives to be 80 years old will need approximately 25,000 doses of medication in their lifetime. nine0003

An orexin-stimulating drug may also be useful in any disease characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness, not to mention a myriad of other situations where low orexin levels play a role—including obesity, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and dementia.

I believe there is another reason why this story has not yet come to an end.

For far too long we have underestimated sleep as an uncomfortable distraction from being awake. With this mindset, sleep research does not seem to be a priority. But this is far from a rational approach.