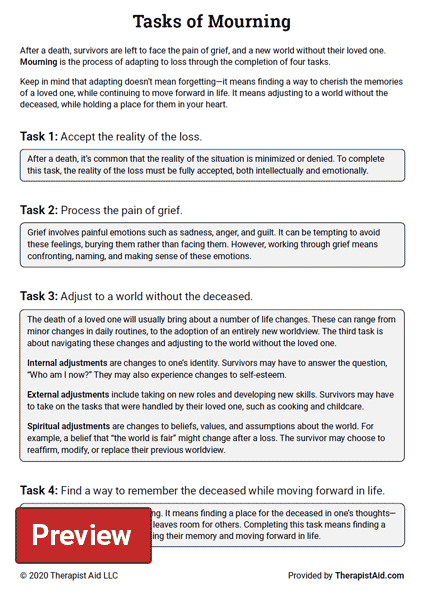

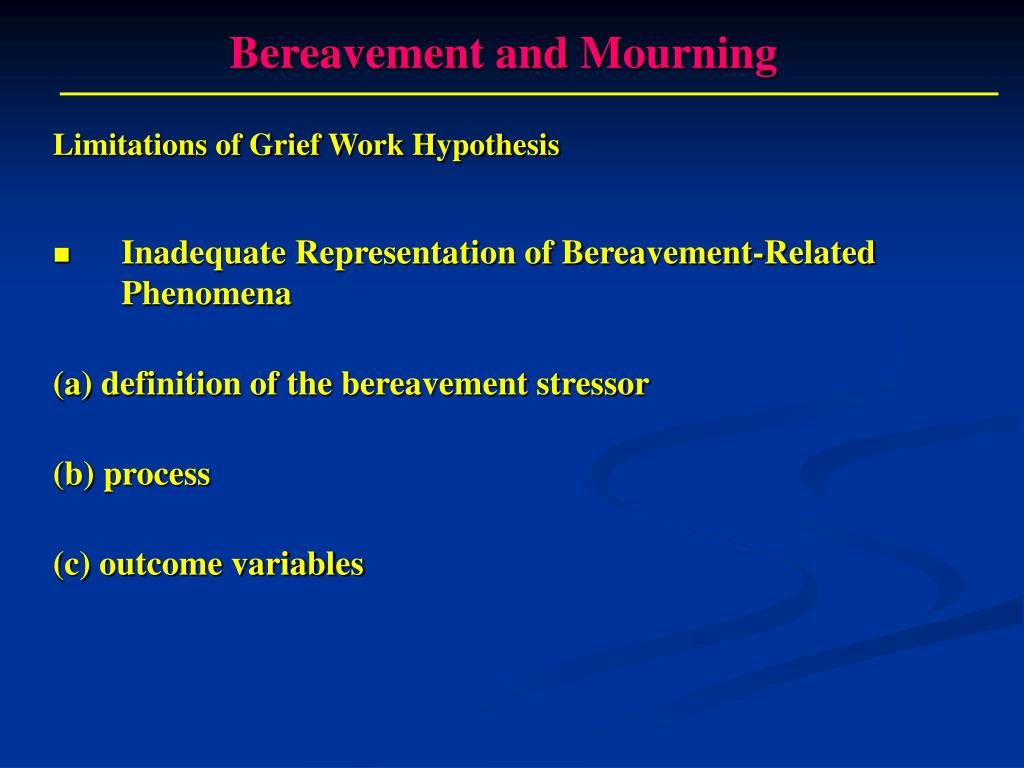

Mourning process definition

Grief And Bereavement | How Long Is The Grieving Process?

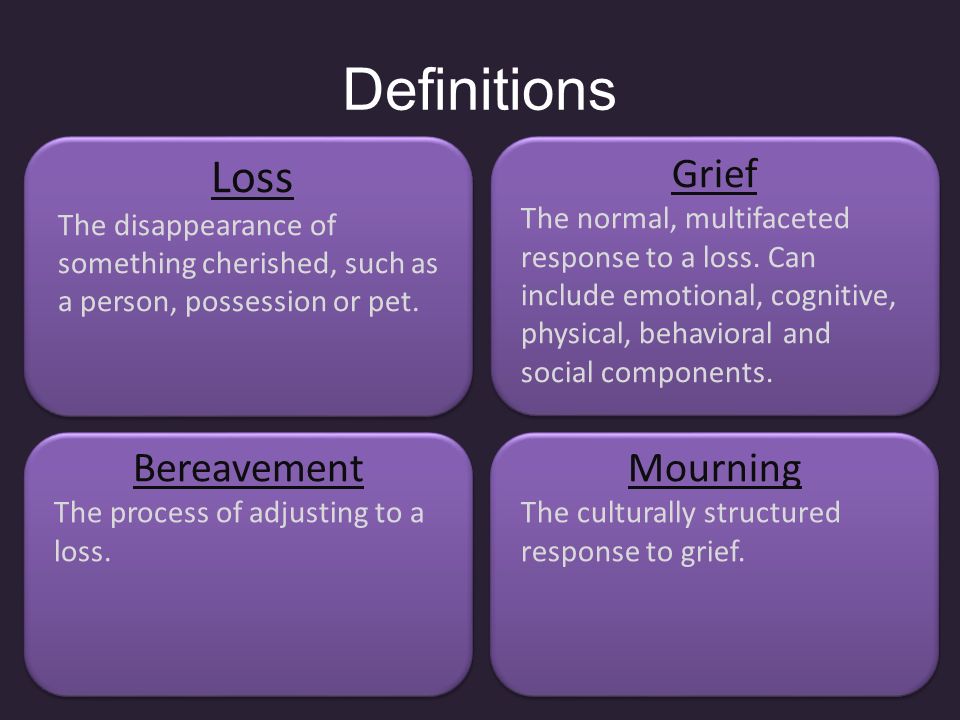

What are grief, mourning, and bereavement?

Grief

Grief is normal, and it is a process. Expressing grief is how a person reacts to the loss of a loved one.

Many people think of grief as a single instance or as a short time of pain or sadness in response to a loss – like the tears shed at a loved one’s funeral. But grieving includes the entire emotional process of coping with a loss, and it can last a long time. The process involves many different emotions, actions, and expressions, all of which help a person come to terms with the loss of a loved one.

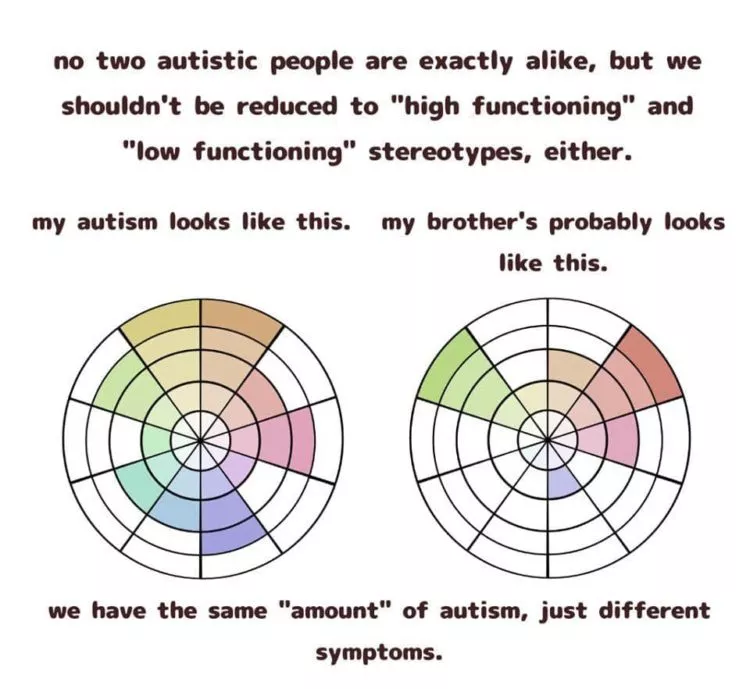

We may hear the time of grief being described as "normal grieving," but this simply refers to a process anyone may go through, and none of us experiences grief the same way. This is because grief doesn’t look or feel the same for everyone. And every loss is different.

Mourning

Mourning often goes along with grief. While grief is a personal experience and process, mourning is how grief and loss are shown in public. Mourning may involve religious beliefs or rituals, and may be affected by our ethnic background and cultural customs. The rituals of mourning − seeing friends and family and preparing for the funeral and burial or final physical separation − often give some structure to the grieving process. Sometimes a sense of numbness lasts through these activities, leaving the person feeling as though they are just “going through the motions” of these rituals.

Bereavement

Grief and mourning happen during a period of time called bereavement. Bereavement refers to the time when a person experiences sadness after losing a loved one.

How long does the grieving process last?

Since each person grieves differently, the length and intensity of the emotions people go through varies from person to person. Grieving is painful, and it’s important that those who have suffered a loss be allowed the time they need to express their grief.

Although grief is described in phases or stages, it may feel more like a roller coaster, with ups and downs. This can make it hard for the bereaved person to feel any sense of progress in dealing with the loss. A person may feel better for a while, only to become sad again. Sometimes, people wonder how long the grieving process will last, and when they can expect some relief. There’s no answer to this question, but some of the factors that affect the intensity and length of grieving are:

- Your relationship with the person who died

- The circumstances of their death

- Your own life experiences

It’s common for the grief process to take a year or longer. A grieving person must resolve the emotional and life changes that come with the death of a loved one. The pain may become less intense, but it’s normal to feel emotionally involved with the deceased for many years. In time, the person should be able to use their emotional energy in other ways and to strengthen other relationships.

Grief can take unexpected forms

Difficult relationships with the deceased prior to death can cause unique grieving experiences for loved ones. In addition, prolonged illnesses can also cause grief to take unexpected forms.

Difficult relationships

A person who had a difficult relationship with the deceased (a parent who was abusive, estranged, or abandoned the family, for example) is often surprised by the painful emotions they have after their death. It’s not uncommon to have profound distress as the bereaved mourns the relationship they had wished for with the person who died, and lets go of any chance of achieving it.

Others might feel relief, while some may wonder why they feel nothing at all at the death of such a person. Regret and guilt are common, too. This is all a normal part of the process of adjusting and letting go.

Grief after long illness

The grief experience may be different when the loss occurs after a long illness rather than suddenly. When someone is terminally ill, family, friends, and even the patient might start to grieve in response to the expectation of death. This is a normal response called anticipatory grief. It can help people complete unfinished business and prepare loved ones for the actual loss, but it might not lessen the pain they feel when the person dies.

When someone is terminally ill, family, friends, and even the patient might start to grieve in response to the expectation of death. This is a normal response called anticipatory grief. It can help people complete unfinished business and prepare loved ones for the actual loss, but it might not lessen the pain they feel when the person dies.

Many people think they are prepared for the loss because death is expected. But when their loved one actually dies, it can still be a shock and bring about unexpected feelings of sadness and loss. For most people, the actual death starts the normal grieving process.

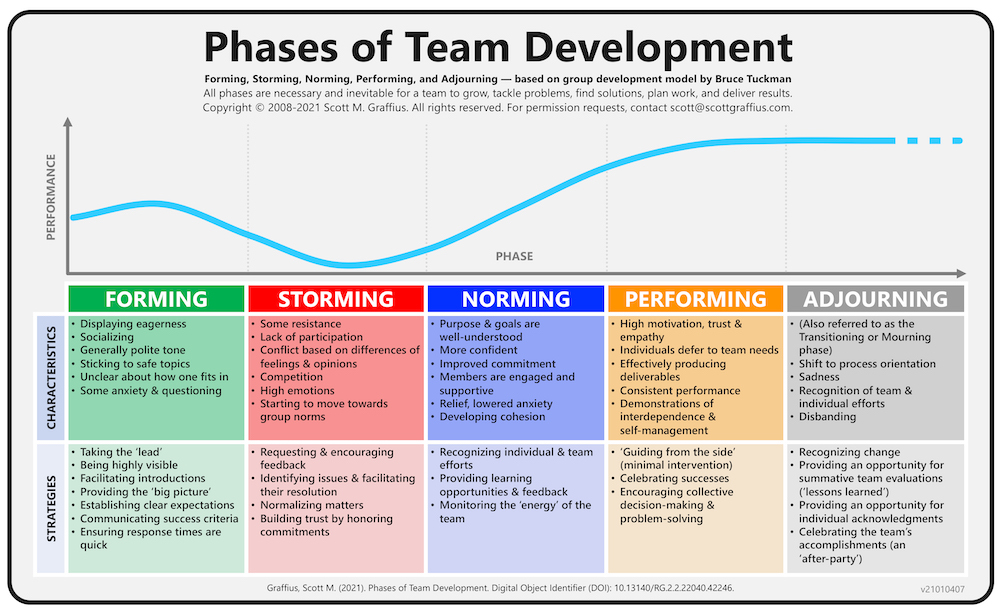

Stages of grief

People may go through many different emotional states while grieving. And in advanced cancer, the grieving process and stages often start before the loss of a loved one because of anticipatory grief.

Researchers describe grief in stages, but it's important to know that each person moves through the stages differently and at a different pace. Some may go through the stages just as they are described below, and other people may move back and forth between stages. Some people may get stuck in one stage and have trouble reaching the final stage of the grief process.

Some may go through the stages just as they are described below, and other people may move back and forth between stages. Some people may get stuck in one stage and have trouble reaching the final stage of the grief process.

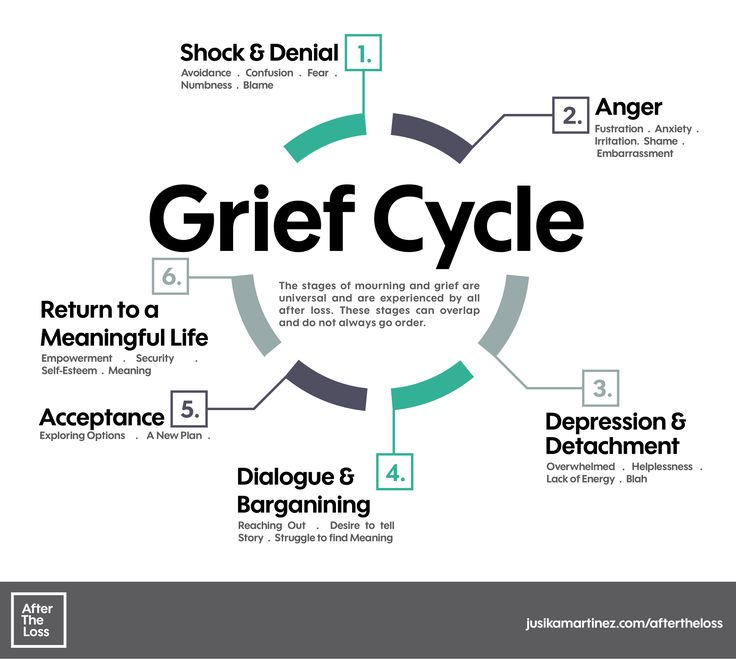

Experts describe 5 stages that are usually experienced by adults during the grief process.

- Denial and isolation - This first stage may start before the loss occurs if the death of the loved one is expected. Or it may begin immediately at the time or shortly after the loss. It can last anywhere from a few hours to days or weeks. The feelings experienced in the first stage of grief may be fear, shock, or numbness. The person may be have pangs of distress, often triggered by reminders of the deceased. During this time, the bereaved person may feel emotionally “shut off” from the world. The grieving person may avoid others or avoid talking about the loss.

- Anger - The next stage can last for days, weeks, or months.

It is when the earliest feelings are replaced by frustration and anxiety. This stage can involve anger, loneliness, or uncertainty. It may be when the feelings of loss are most intense and painful. The person may feel agitated or weak, cry, engage in aimless or disorganized activities, or be preoccupied with thoughts or images of the person they lost.

It is when the earliest feelings are replaced by frustration and anxiety. This stage can involve anger, loneliness, or uncertainty. It may be when the feelings of loss are most intense and painful. The person may feel agitated or weak, cry, engage in aimless or disorganized activities, or be preoccupied with thoughts or images of the person they lost. - Bargaining - This stage is likely to be shorter than others. It happens when a grieving person is struggling to find meaning for the loss of their loved one. They may reach out to others and tell their story. In doing so, they may begin to think more clearly about the changes brought about by the loss of their loved one.

- Depression - As life changes are realized, depression may set in. This stage is used to describe a grieving person who feels overwhelmed and helpless. They may withdraw, become hostile, or express extreme sadness. During this time, grief tends to come in waves of distress.

- Acceptance - This last phase of grief happens when people find ways to come to terms with and accept the loss. Usually, the person comes to accept the loss slowly over a few months to a year. This acceptance includes adjusting to daily life without the deceased.

Children grieve, too, but the process may look different from adults. To learn more about this, see Helping Children When a Family Member Has Cancer.

Some or all of the following may be seen in a person who is grieving:

- Socially withdrawing

- Trouble thinking and concentrating

- Becomes restless and anxious at times

- Loss of appetite

- Looks sad

- Feels depressed

- Dreams of the deceased (or even have hallucinations or “visions” in which they briefly hear or see the deceased)

- Loses weight

- Trouble sleeping

- Feels tired or weak

- Becomes preoccupied with death or events surrounding death

- Searches for reasons for the loss (sometimes with results that make no sense to others)

- Dwells on mistakes, real or imagined, that they made with the deceased

- Feels guilty for the loss

- Feels all alone and distant from others

- Expresses anger or envy at seeing others with their loved ones

Reaching the acceptance stage and adjusting to the loss does not mean that all the pain is over. Grieving for someone who was close to you includes losing the future you expected with that person. This must also be mourned. The sense of loss can last for decades. For example, years after a parent dies, the bereaved may be reminded of the parent’s absence at an event they would have been expected to attend. This can bring back strong emotions, and require mourning yet another part of the loss.

Grieving for someone who was close to you includes losing the future you expected with that person. This must also be mourned. The sense of loss can last for decades. For example, years after a parent dies, the bereaved may be reminded of the parent’s absence at an event they would have been expected to attend. This can bring back strong emotions, and require mourning yet another part of the loss.

The Stages of Grief: Accepting the Unacceptable

June 8, 2020

Posted by Caitlin Stanaway, Psy.D., Licensed Psychologist, UWCC

The pandemic has impacted our routines, social lives, school, work, and more. It has caused the loss of lives around the globe, as well as the loss of normalcy. The recent death of George Floyd has put police brutality, murders of Black and Brown people, racial and social injustice into the spotlight. There are many losses to grieve amidst the intensity of civil unrest, on top of more typical stressors like taking finals and looking for a job.

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross developed the five stages of grief in her 1969 book, On Death and Dying. Grief is typically conceptualized as a reaction to death, though it can occur anytime reality is not what we wanted, hoped for, or expected.

Persistent, traumatic grief can cause us to cycle (sometimes quickly) through the stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. These stages are our attempts to process change and protect ourselves while we adapt to a new reality. While there are consistent elements within each stage, the process of grieving looks different for everyone.

When you combine experiences of stress and trauma to grief, it is overwhelming. It takes a toll on our mental and physical health. Our minds and bodies are consistently being impacted by the stress response, a nervous system reaction to feeling threatened. It triggers the release of adrenaline and cortisol, impacting sleep, appetite, making it difficult to function at your best.

Symptoms of anxiety and depression may develop, as well as trauma symptoms like intrusive thoughts, nightmares, feeling disconnected from self. Trauma related to racial injustice is chronic. Resources for Black healing, including crisis support, self-care, and reducing cortisol levels in response to racial stressors can be found here.

Being aware of the grief stages and how you uniquely experience them can increase self-understanding and compassion. It can help you better understand your needs and prioritize getting them met.

Denial

| can look like: | can feel like: |

|---|---|

| avoidance | shock |

| procrastination | numbness |

| forgetting | confusion |

| easily distracted | shutting down |

| mindless behaviors | |

| keeping busy all the time | |

| thinking/saying, “I’m fine” or “it’s fine” |

Anger

| can look like: | can feel like: |

|---|---|

| pessimism | frustration |

| cynicism | impatience |

| sarcasm | resentment |

| irritability | embarrassment |

| being aggressive or passive-aggressive | rage |

| getting into arguments or physical fights | feeling out of control |

| increased alcohol or drug use |

Bargaining

| can look like: | can feel like: |

|---|---|

| ruminating on the future or past | guilt |

| over-thinking and worrying | shame |

| comparing self to others | blame |

| predicting the future and assuming the worst | fear, anxiety |

| perfectionism | insecurity |

| thinking/saying, “I should have…” or ”If only…” | |

| judgment toward self and/or others |

Depression

| can look like: | can feel like: |

|---|---|

| sleep and appetite changes | sadness |

| reduced energy | despair |

| reduced social interest | helplessness |

| reduced motivation | hopelessness |

| crying | disappointment |

| increased alcohol or drug use | overwhelmed |

Acceptance

| can look like: | can feel like: |

|---|---|

| mindful behaviors | “good enough” |

| engaging with reality as it is | courageous |

| “this is how it is right now” | validation |

| being present in the moment | self-compassion |

| able to be vulnerable & tolerate emotions | pride |

| assertive, non-defensive, honest communication | wisdom |

| adapting, coping, responding skillfully |

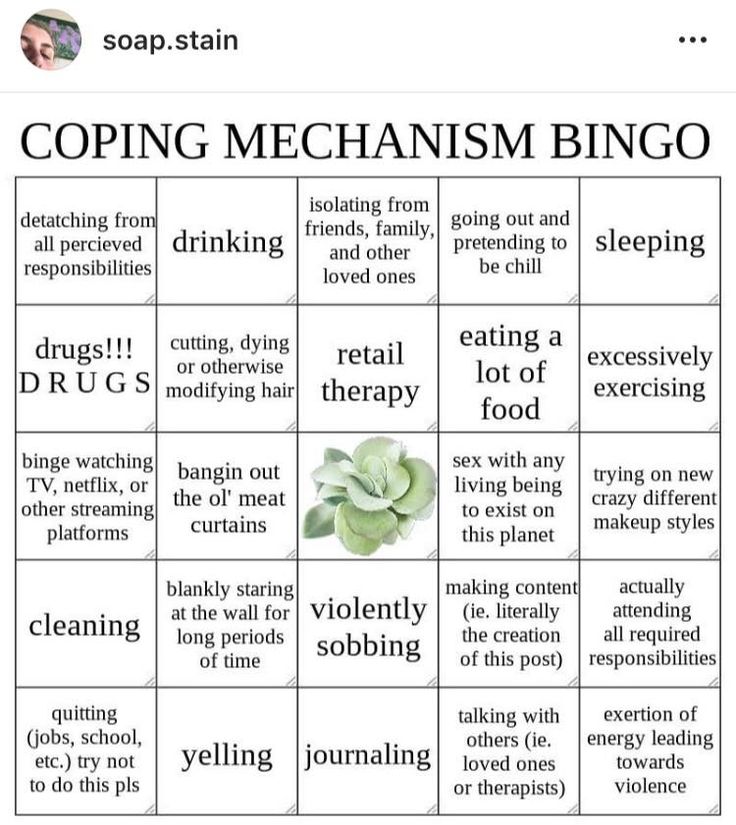

Generally, if we are not in the stage of acceptance then we are in some way fighting against or avoiding reality. We might start sleeping more. Our mood or anxious thoughts might become the focus of attention, distracting from external stressors. We might use alcohol or drugs to avoid or disconnect from reality. We might keep our focus on tasks, responsibilities, or the needs of others – staying busy as much as possible to avoid feeling distress.

We might start sleeping more. Our mood or anxious thoughts might become the focus of attention, distracting from external stressors. We might use alcohol or drugs to avoid or disconnect from reality. We might keep our focus on tasks, responsibilities, or the needs of others – staying busy as much as possible to avoid feeling distress.

Acceptance doesn’t mean not experiencing distress, emotions or trauma. It does not mean you condone what is happening. It means noticing what you are fighting against, validating your desire to fight against it, and re-orienting yourself to the reality of the moment you are in. It means not getting stuck, or getting un-stuck, from other stages. Mindfulness and a non-judgmental, curious attitude can be a big help.

Acceptance might look like saying to yourself: “If I sleep too long today I’ll keep sleeping through the mornings. I’m going to prioritize getting my schedule regulated.” It might look like noticing: “I’m directing my anger and sadness about what’s going on toward myself and ruminating on self-criticisms. I’ll acknowledge my anger and what it’s really about.” Or reflecting, “how could I not be angry about ___? Who wouldn’t be anxious about ___? Of course it’s extremely hard to accept ___”; It might look like checking in on yourself: “If I keep neglecting my own needs and focusing on work/others, I’ll end up feeling burned out and exhausted. I’ll take time to assess how I’m doing and what I need.”

I’ll acknowledge my anger and what it’s really about.” Or reflecting, “how could I not be angry about ___? Who wouldn’t be anxious about ___? Of course it’s extremely hard to accept ___”; It might look like checking in on yourself: “If I keep neglecting my own needs and focusing on work/others, I’ll end up feeling burned out and exhausted. I’ll take time to assess how I’m doing and what I need.”

It is rare to move through the stages in a linear way. It is normal to experience ups and downs in mood, thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors. It can be difficult maintaining acceptance while things feel so unacceptable.

If you are feeling overwhelmed by grief, loss, trauma you do not have to go through it alone. The Counseling Center can offer culturally-sensitive support and guidance through the grieving process.

Honduras: difficult process of identifying victims of Comayagua prison fire

14-03-2012 Interview

Following the 14 February fire at Comayagua prison in Honduras that killed more than 360 people, the ICRC began helping authorities identify the dead through a forensic medical examination, and provide psychological assistance to their family members. In this interview, Alejandra Jiménez, ICRC forensic adviser, talks about the challenges and achievements of her work in Honduras.

In this interview, Alejandra Jiménez, ICRC forensic adviser, talks about the challenges and achievements of her work in Honduras.

How is the humanitarian situation one month after the fire in Comayagua?

Since the remains of a large number of victims remain unidentified, the process of identifying the victims is complex and time-consuming. For families who are waiting for the release of the bodies of their relatives in order to pay tribute to the memory and say goodbye to them, the wait is associated with severe suffering. The main humanitarian impact so far is the psychological trauma inflicted on relatives who have to wait to begin the mourning process.

What support does the ICRC provide?

In the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, the ICRC provided the necessary materials for dealing with the remains of those killed in the fire, including body bags, surgical instruments, cameras and FTA cards to determine genetic information. However, the main focus of the ICRC was on providing technical advice to the Honduran government.

Two ICRC psychologists provided psychological support to relatives and relief workers. Three forensic experts provided assistance and advice on the methods to be used at various stages of the work, from the recovery of the bodies, to their transfer and disposal. The ICRC staff did not directly deal with the remains, but advised the authorities on issues such as processing information about the victims, storing the bodies and determining the work of the forensic teams.

As in many post-disaster situations, the absence of an adequate information management system was evident. The ICRC therefore handed over a database that had been developed to organize, manage and use the information collected during the identification process. Training on working with this database was also provided.

How was psychological support organized and what was the role of the ICRC?

The main challenge in such situations is to communicate clearly and openly with the families of the victims. If the authorities remain silent and do not maintain contact with families, then a psychological barrier is created, and families feel cut off from their loved ones and from the whole process.

If the authorities remain silent and do not maintain contact with families, then a psychological barrier is created, and families feel cut off from their loved ones and from the whole process.

The feeling of the unknown is very hard to bear. In relation to the situation in Honduras, families feared that their loved ones would be buried in a mass grave or that, in the absence of international assistance, their bodies would not be returned to their relatives.

The ICRC has advised both the government and forensic experts on establishing clear channels of communication with families so that they can be told what to expect from the process, how long it will take, and the limitations and difficulties involved in the identification procedure remains. The ICRC also stressed the need to explain to the media what forensic experts do, so that they are aware of the tireless and hard work that is going on, and how information is handled, thus supporting the families of the victims.

What are the main challenges today?

We need to take a short and long term approach. We need to continue to support family members whose relatives are still unidentified and maintain dialogue with them. It is very important that all the information collected during the identification of the remains be entered into the database provided by the ICRC. It needs to be fully analyzed.

The ICRC must live up to the expectations associated with its role in Honduras, which in turn will pave the way for the organization's involvement in the country's humanitarian problems. The Government has asked the ICRC to conduct a nationwide assessment of the capacity of the forensic services and forensic medicine in order to develop practical recommendations.

Violence is common in Honduras. Many of the bodies still remain unidentified, leaving many families anxiously awaiting news. In these circumstances, the ICRC seeks to cooperate with the authorities and intends to promote the development of forensic medicine in order to provide humanitarian assistance.

Photo

ICRC forensic expert Alejandra Jiménez assists forensic experts in organizing, classifying, verifying and processing the collected information.

© ICRC / A. Jiménez

A radiologist examines x-rays looking for signs of trauma, fractures, medical devices and other distinguishing features.

© ICRC / A. Jiménez

A forensic team dentist assesses the age of a deceased by examining the teeth.

© ICRC / A. Jiménez

Clothing helps to identify the remains and is valuable to relatives as a memory item.

© ICRC / A. Jiménez

Experts analyze and compare fingerprints to identify victims.

© ICRC / A. Jiménez

Medical examiners work to identify the bodies of the dead in the mortuary where autopsies were previously performed.

© ICRC / A. Jiménez

How do you restore peace of mind after the loss of a loved one?

Strength and love to all who are grieving now.

Human tears, oh human tears,

You are pouring early and late at times...

Unknown ones are pouring, invisible ones are pouring,

Inexhaustible, innumerable -

You are pouring like rain streams are pouring

In the deaf autumn sometimes at night...

F.I. Tyutchev

Every year on the third Sunday of May World AIDS Day is celebrated around the world. On this day, in all countries, millions of people organize various events to honor the memory of those who died from AIDS.

The loss of a loved one is the most difficult event affecting all aspects of life, all levels of a person's physical, mental and social existence. The process of experiencing loss is called the work of grief. Mourning is a natural process in which the body strives for balance, healing its wounds, both physical and mental.

“The experience of grief is one of the most mysterious actions of the soul,” writes F.E. Vasilyuk in his work "To Survive Grief". How miraculously will a person devastated by loss manage to be reborn and fill his world with meaning? How can he, confident that he has forever lost the joy and desire to live, be able to restore peace of mind, feel the colors and taste of life? How is suffering melted into wisdom? All these are pressing questions, to know specific answers, to which you need, if only because sooner or later we all have to, whether by professional duty or by human duty, console and support grieving people, help to survive grief.

Grief and loss are always unexpected, even if we seemed to be ready and expected the loss, it is still expected, but still a surprise.

Surely many of us are familiar with this feeling of embarrassment when you don't know what to say, how to behave, or when you don't know what to do. How to help a suffering person? Just like with bodily injuries, the process of healing a spiritual wound has its own patterns. Knowledge of these patterns can serve as a support to help reduce feelings of confusion and helplessness, can provide a more adequate perception of the behavior of a suffering person and provide the necessary support and assistance.

Knowledge of these patterns can serve as a support to help reduce feelings of confusion and helplessness, can provide a more adequate perception of the behavior of a suffering person and provide the necessary support and assistance.

The initial phase of grief is shock and numbness. "It can't be!" - this is the first reaction to the news of death. F.E. Vasilyuk notes that the characteristic state can last from a few seconds to several weeks, on average, by the 7-9th day, gradually changing to another picture.

Stupor is the most noticeable feature of this condition. The mourner's breathing is difficult, irregular, a frequent desire to take a deep breath leads to intermittent, convulsive (like steps) incomplete inspiration, stiffness, tension. Inactivity is sometimes replaced by minutes of fussy activity.

Everything that happened seems unreal, the soul seems to be numb, feeling insensible, stunned. External reality is perceived with difficulty, so after a while it can be difficult for a person to remember what is happening.

It is important to understand! It is believed that a person in this state does not let what happened into his life. At this time, he seems to be in two worlds at once, in the present - "here and now" and in the past - "there and then" until the moment of loss. We are not dealing with the denial of the fact that "he (the deceased) is not here", but with the denial of the fact that "I (the mourner) are here". A tragic event that has not happened is not admitted into the present, and it itself does not allow the present into the past. The shock leaves the person in this “before”, where the deceased was still alive, was still nearby. If a person could clearly realize what is happening to him in this period of stupor, he could say to those who sympathize with him that the deceased is not with him: “I am not with you, I am there, more precisely, here, with him.”

The present "presses" on such an inner world - any call, any signal from the present turns into a hindrance that interferes with existence in the "there and then", and this existence in the past - an urgent need and any obstacle - causes a feeling of anger. How to explain all these phenomena? Such a state is a protective mechanism of our psyche, mental anesthesia - a denial of the fact or meaning of death. The soul cannot immediately, entirely, accept the loss.

How to explain all these phenomena? Such a state is a protective mechanism of our psyche, mental anesthesia - a denial of the fact or meaning of death. The soul cannot immediately, entirely, accept the loss.

What to do? The main mental work of a grieving person is understanding and accepting what happened with the mind . It is very important at this stage to give vent to feelings – to be able to talk about what is happening, but also to be able to be distracted. It is good if there is a person nearby who is able to share the pain of loss and support. His task is to accompany the process of natural experience, not interfering with it, but supporting it, to be ready to listen and just be together. Remember the period of the first days after the loss? What was important to you at that moment? Most often they answer - the real help of friends, relatives. Need someone to just take care about the physical condition of a grieving person, because he may forget to eat, sleep badly, it happens that people go to bed without undressing, etc. To come, help organize a funeral, deal with documents, cook food, etc. phase of loss denial, its constancy and inevitability.

To come, help organize a funeral, deal with documents, cook food, etc. phase of loss denial, its constancy and inevitability.

The first strong feeling that breaks through the veil of numbness and deceptive indifference is often anger or aggression. It is unexpected, incomprehensible to the person himself, he is afraid that he will not be able to contain it. Sometimes it happens that with our mind we understand that “you can’t be angry, offended”, but still we feel anger or resentment because the deceased “left me”.

It is difficult to single out the temporal boundaries of this period, since it continues in waves in the next stages of grief. On average, they allocate 5-12 days after the news of death. At this time, the mind seems to be playing with us, while frightening with visions of the deceased - then we suddenly see him in the subway and immediately feel a prick of fright - “he is dead”, then suddenly a phone call, a thought flashes - he is calling, then we hear his voice is on the street, but here he is rustling slippers in the next room. .. Such visions are quite common and natural, but they frighten, being taken for signs of impending madness. It is important to understand that this is a normal course of grief, at this time the mind takes attempts to come to terms with the loss, to comprehend it.

.. Such visions are quite common and natural, but they frighten, being taken for signs of impending madness. It is important to understand that this is a normal course of grief, at this time the mind takes attempts to come to terms with the loss, to comprehend it.

Sometimes the mourner speaks of the deceased in the present tense, not in the past, for example, “he/she cooks well (and did not cook)”, if this happens a month or more after the loss, then there is a delay in the stage of understanding and acceptance mind. Stuck at the stage of denial can also be indicated by the fact that a person keeps the things of the deceased intact, continues to mentally communicate with him. A person is looking for any opportunity to linger in the past and forget the present.

But the present is accepted more and more and then comes the third phase - acute grief , lasting up to 6-7 weeks from the moment of the tragic event. Otherwise, it is called a period of despair, the greatest suffering, disorganization and acute mental pain.

Persist, and at first may even increase, various bodily reactions - shortness of breath, shortness of breath, muscle weakness, loss of energy, feeling of heaviness in any action, feeling of emptiness in the stomach, tightness in the chest, lump in the throat, increased sensitivity to odors, decreased or unusual increase in appetite, sleep disturbances.

Many difficult, sometimes strange and frightening feelings and thoughts appear. These are feelings of emptiness and meaninglessness, despair, a feeling of abandonment, loneliness, anger, guilt, fear, anxiety, helplessness. Characterized by an unusual preoccupation with the image of the deceased (frequent memories) and his idealization - especially emphasizing the merits of the deceased, avoiding memories of bad character traits and actions. Relations with others worsen - loss of warmth, irritability, desire to retire.

It is difficult to work, to do ordinary things, it is difficult to concentrate on what a person is doing, it is difficult to bring things to the end, and complexly organized activities may become completely inaccessible for some time. Sometimes, unconsciously, the mourner identifies himself with the deceased - involuntarily imitates his gait, gestures, facial expressions.

Sometimes, unconsciously, the mourner identifies himself with the deceased - involuntarily imitates his gait, gestures, facial expressions.

Sometimes a person cannot get out of depression, does not allow himself to rejoice, because the departed person cannot rejoice. The person may become stuck in anger, such as looking for blame, blaming the medical staff, constantly thinking about revenge, or becoming angry and irritable. Often, emotional problems develop into somatic ones, health deteriorates, a person “goes into illness”. Wanderings among doctors begin, the search for medical assistance, but in fact the person does not want healing.

Important to understand! It is here, at this step of acute grief, that separation begins, detachment from the image of the beloved, a shaky support in the “here and now” is being prepared, which will allow you to say at the next step: “You are not here, you are there ... ".

It is at this point that acute mental pain appears. Paradoxically, pain is caused by the grieving person himself: phenomenologically, in a fit of acute grief, it is not the deceased who leaves us, but we ourselves leave him, break away from him or push him away from us. And this self-made separation, this own departure, this exile of a loved one: “Go away, I want to get rid of you ...” and watching how his image really moves away, transforms and disappears, and, in fact, causes spiritual pain. However, it also creates a new connection. As F.E. Vasilyuk: “The pain of acute grief is not only the pain of decay, destruction and death, but also the pain of the birth of a new one.” What exactly? Two new selves and a new connection between them, two new times. The new "I" is able to see not "you", but "us" in the past.

Paradoxically, pain is caused by the grieving person himself: phenomenologically, in a fit of acute grief, it is not the deceased who leaves us, but we ourselves leave him, break away from him or push him away from us. And this self-made separation, this own departure, this exile of a loved one: “Go away, I want to get rid of you ...” and watching how his image really moves away, transforms and disappears, and, in fact, causes spiritual pain. However, it also creates a new connection. As F.E. Vasilyuk: “The pain of acute grief is not only the pain of decay, destruction and death, but also the pain of the birth of a new one.” What exactly? Two new selves and a new connection between them, two new times. The new "I" is able to see not "you", but "us" in the past.

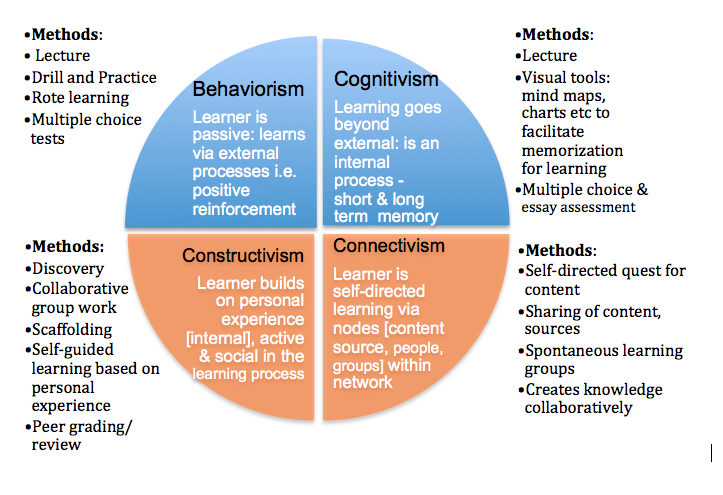

What to do? The main spiritual work is the acceptance of loss by feelings.

A grieving person needs to go through pain in order to return to the surface from the depths of the stream of the past. The pain goes away if you manage to take out a grain of sand, a pebble, a shell of memory from the depths and examine them in the light of the present, in the “here and now”. The harsh reality is that you can live through pain only by being sick, feeling it. Listen, hear, live until it becomes less unbearable. There is no other way than experience to get rid of suffering. The whole future life depends on the quality of the work of experiencing.

The pain goes away if you manage to take out a grain of sand, a pebble, a shell of memory from the depths and examine them in the light of the present, in the “here and now”. The harsh reality is that you can live through pain only by being sick, feeling it. Listen, hear, live until it becomes less unbearable. There is no other way than experience to get rid of suffering. The whole future life depends on the quality of the work of experiencing.

Just like in the previous stage, it is very important to express feelings . It is important to give vent to feelings, to give them a place to be, without judgment, with acceptance. This is not easy to do, as this is a difficult period for everyone - the grieving person and those who support him. After all, a grieving person can experience different feelings - pain, sadness, grief, anger, anger, guilt and shame for himself. He may judge himself for his negative emotions. It is sometimes difficult for close people to even sit next to each other, to be close. You want to leave, go out, console or distract and isolate yourself from the intense suffering of another.

You want to leave, go out, console or distract and isolate yourself from the intense suffering of another.

How to explain this? When a person next to you hurts, when he tells you about his pain, most likely this also actualizes your personal pain. It is very important in this case to be able to experience it, not to ignore it and not to push it away. You can literally report that you, too, were once in pain and that this pain is still with you to one degree or another. Perhaps it is at this moment that your pain will first "see the light" and be shared. It was not in vain that earlier there were mourners at the funeral, whose crying helped to express feelings to loved ones, helped to “cry out”.

And more importantly - forgive yourself . Mourning is almost always associated with guilt. A person may feel guilty for the grievances that he inflicted on the deceased, as well as for the fact that he is alive and admires the sunset, eats, drinks, listens to music, and a loved one died. Here it is important not to convince yourself (or the person experiencing the loss) that no one is to blame, as a rule, this is impossible, but to forgive yourself.

Here it is important not to convince yourself (or the person experiencing the loss) that no one is to blame, as a rule, this is impossible, but to forgive yourself.

Physical activity with an “emotional” intention helps to reduce the severity of feelings. D. Arcangel in his book "Life after loss" writes that it doesn't matter what kind of activity you engage in. Intention and emotions matter. You can do physical exercises or wash dishes, clean the house, etc. with the experience of pain and grief, giving a splash of their energy, releasing their feelings.

The fourth phase of grief is the phase of "residual shocks and reorganization".

Gradually, life gets back on its track, sleep, appetite, professional activity are restored, the deceased ceases to be the main focus of life. A person, as it were, learns to live in a new, different way.

The experience of grief now proceeds in the form of at first frequent, and then increasingly rare individual shocks, such as occur after a major earthquake. Such residual grief attacks can be as acute as in the previous phase, and subjectively perceived as even more acute against the background of normal existence. The reason for them is most often some dates, traditional events (“New Year for the first time without him”, “spring for the first time without him”, “birthday”, etc.) or events of everyday life (“offended, there is no one to complain” , “a letter came to his name”, etc.). The fourth phase, as a rule, lasts for a year: during this time, almost all ordinary life events occur and begin to repeat themselves in the future. The death anniversary is the last date in this series. Perhaps not coincidentally, this is why most cultures and religions set aside one year for mourning.

Such residual grief attacks can be as acute as in the previous phase, and subjectively perceived as even more acute against the background of normal existence. The reason for them is most often some dates, traditional events (“New Year for the first time without him”, “spring for the first time without him”, “birthday”, etc.) or events of everyday life (“offended, there is no one to complain” , “a letter came to his name”, etc.). The fourth phase, as a rule, lasts for a year: during this time, almost all ordinary life events occur and begin to repeat themselves in the future. The death anniversary is the last date in this series. Perhaps not coincidentally, this is why most cultures and religions set aside one year for mourning.

What to do? The main mental work at this stage is the formation of a new identity, a new "I". The meaning and task of the work of grief in this phase is to ensure that the image of the deceased takes its permanent place in the ongoing semantic cycle of life (it can, for example, become a symbol of kindness) and be fixed in the timeless, value dimension of being.

Having survived a loss, a person becomes a little (and sometimes a lot) different. It is important to realize and accept the new self. After all, long-term pain and suffering are strong feelings - and the mourner cannot ignore them. And then there comes a moment when we realize that we can no longer remain the same as we were before the loss. Something within us transforms suffering into wisdom.

The described normal experience of grief in about a year enters its last phase - "completion" . Here, the mourner sometimes has to overcome some cultural barriers that make the act of completion difficult (for example, the notion that the duration of grief is a measure of our love for the deceased). Gradually, the loss enters life, is comprehended. Sadness appears, which is called, including “light”.

More and more memories appear, freed from pain, guilt, resentment, abandonment. Some of these memories become especially valuable, dear, they are sometimes woven into whole stories that are exchanged with relatives, friends, they often enter the family "mythology".

Often the image of a departed person, with whom many life ties connected us, is “saturated” with unfinished joint affairs, unfulfilled hopes, unfulfilled desires, unfulfilled plans, unforgiven insults, unfulfilled promises. Many of them are already almost obsolete, others are in full swing, others have been postponed for an indefinite future, but all of them are not finished, all of them are like questions asked, waiting for some kind of answers, requiring some kind of action. Each of these relationships is charged with a goal, the final unattainability of which is now felt especially sharply and painfully.

What to do? Rituals are of great importance in psychological practice. In addition to the rituals offered to us by culture, we can resort to our own special rituals. For example, to the ritual of farewell to the deceased by writing him a farewell letter. Such a ritual mourning ceremony will help to release some of the feelings and emotions that cause discomfort, to become aware of them, and also to begin the recovery process. Psychological letter writing technique is effective for loss, separation, resentment, guilt, etc. The exercise releases a lot of complex feelings: pain, longing, anxiety, sadness, regret, sadness.

Psychological letter writing technique is effective for loss, separation, resentment, guilt, etc. The exercise releases a lot of complex feelings: pain, longing, anxiety, sadness, regret, sadness.

Here are some simple rules for writing " Farewell Letter " (you can add to them as you wish):

- Title and address (to the deceased person).

- Start each new sentence of your letter with the word "Goodbye" (this will help you stay focused on the task).

- Write in a letter about overwhelming feelings.

- Thank the deceased person for being in your life, for all the good that is connected with him, for the life experience that you have gained thanks to him, etc.

- Write how you see your life further, without him.

- Sign.

It is necessary to understand that the experience of grief, as well as relationships, is always individual, unique and hardly fits into the framework of universal laws and rules.