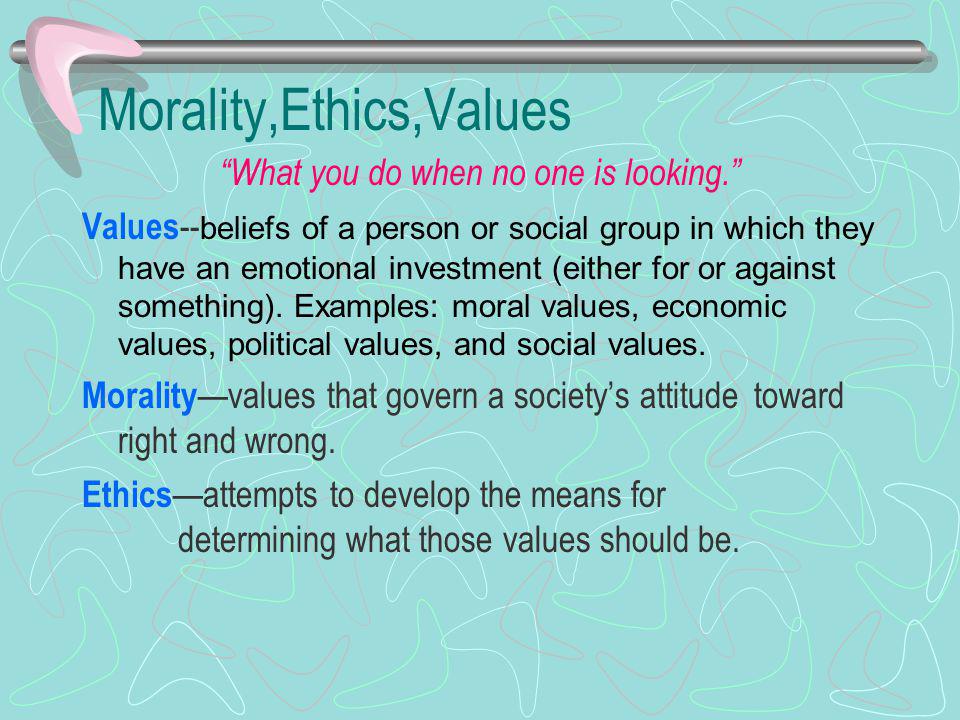

Moral conscience examples

The Moral Conscience - Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis

By Most Reverend Harry J. Flynn

Archbishop Emeritus

Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis

INTRODUCTION

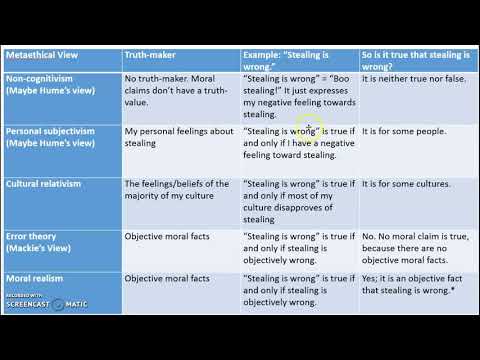

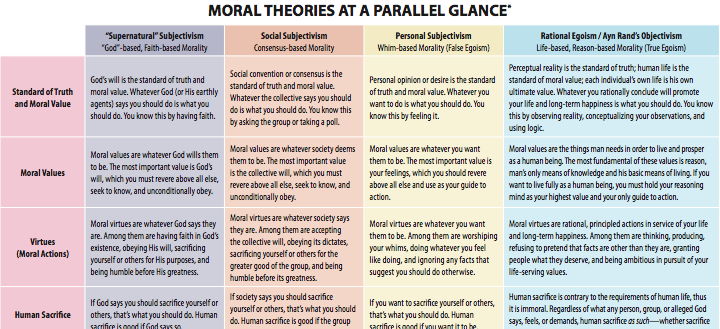

There are those who view the moral conscience as personal, internal, subjective and open to no criticism from without. Even in the Catechism of the Catholic Church one might think to find justification for such an outlook. There we read: “Man has the right to act in conscience and in freedom so as personally to make moral decisions. ‘He must not be forced to act contrary to his conscience. Nor must he be prevented from acting according to his conscience, especially in religious matters.’”1

The problem with an overly subjective outlook is that it misses the point. It does not look at the whole question of conscience, just as this quotation from the catechism would not be properly understood if it were left standing by itself without seeing it in conjunction with the paragraphs that surround it.

The proper understanding of the moral conscience is basic to our understanding of morality and to the living of our lives. I would like, therefore, in this letter to address some of the most important aspects of conscience with the hope that a clearer understanding of them will also result in a deeper appreciation of what a gift conscience is and why we must, for our own eternal happiness, attend to its proper formation.

I. THE QUESTION: “Where are you?” (Gen 3:9)

Can we really know the difference between right and wrong? Fifty years ago that would have been a question easily answered. Now it may be hotly debated or simply dismissed. In one sense the explanation is as old as humanity. We were created in the image of God (Gen 1-2) and were called to know the truth and to live in love. Yet, our first parents disobeyed God and introduced sin into the world, thus depriving the intellect of an easy grasp of truth and constancy of will in living the good (Gen 3). Created for communion with God and with one another in truth and love, Adam and Eve chose instead to decide for themselves what would be right and what would be wrong, and so they (and in them all of us) began to hide from God.

Created for communion with God and with one another in truth and love, Adam and Eve chose instead to decide for themselves what would be right and what would be wrong, and so they (and in them all of us) began to hide from God.

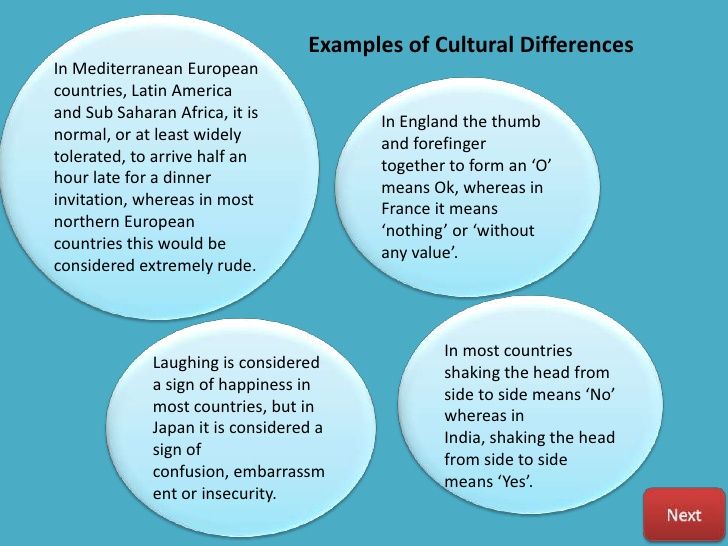

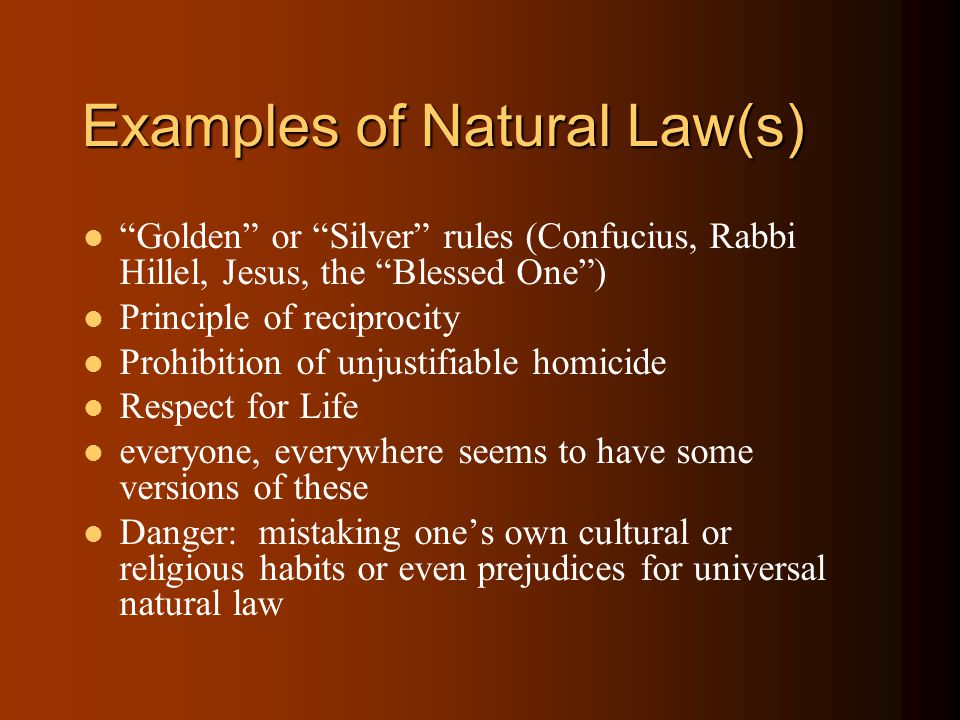

The consequence of that choice is mutual recrimination (“The woman made me do it…,” “The serpent tricked me…”), self-disillusionment and even death — consequences which we know all too well. But God does not abandon Adam and Eve to their lie. Instead, he seeks them out: “Where are you?” (Gen 3:9-) Fifty years ago it was every bit as possible as it is now to choose wrong rather than right and try to justify oneself for doing so, but fifty years ago it was also easier to know and agree on the difference between right and wrong. At that time we still shared cultural values about the truth of the natural moral law. What is “new” today is that now the very idea of knowing right and wrong is called into question.

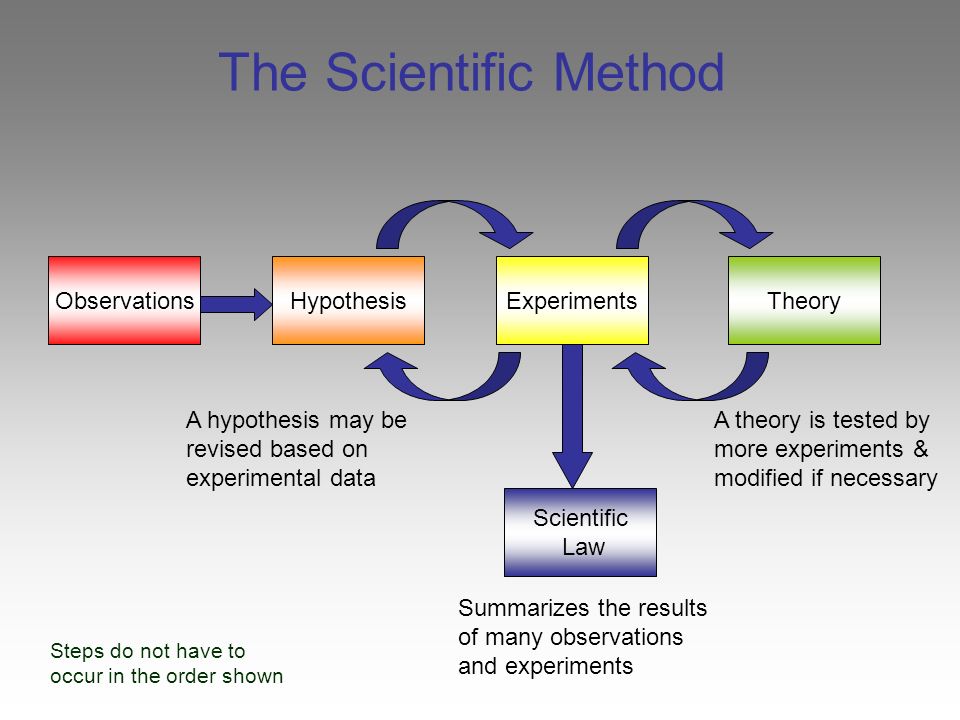

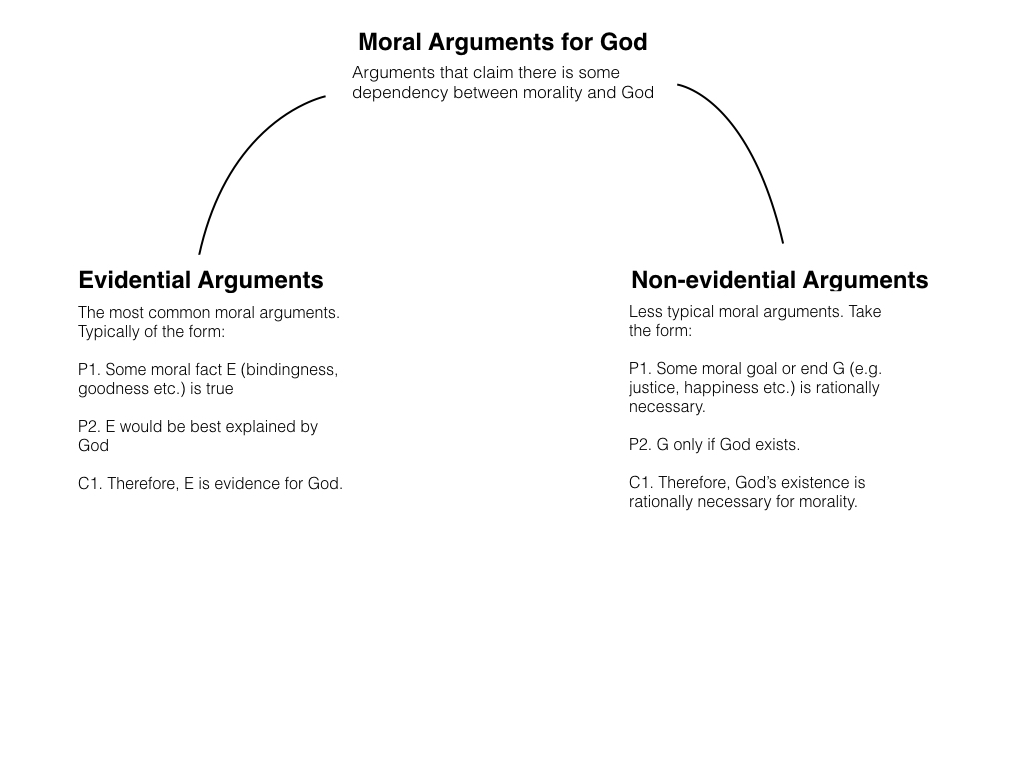

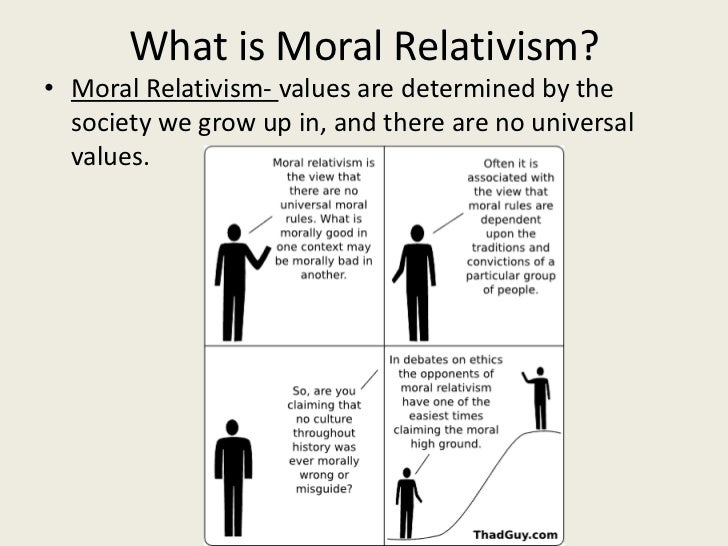

This questioning of the truth of right and wrong, the questioning even of the possibility of knowing anything to be certain, leads to what we call “relativism. ” It has been creeping up on us for centuries, gradually changing the way we think about ourselves and our world. The Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment — not to mention religious wars and persecutions — were among the catalysts that led intellectuals in the Western world to question the shared philosophies of our ancestors and the theological foundations of Greek and Judaeo-Christian thought. Such questions fostered a tendency to think it better to be “modern” than to be “ancient,” even though to classify an idea as “modern” or “ancient” tells us nothing about whether it is true or false.

” It has been creeping up on us for centuries, gradually changing the way we think about ourselves and our world. The Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment — not to mention religious wars and persecutions — were among the catalysts that led intellectuals in the Western world to question the shared philosophies of our ancestors and the theological foundations of Greek and Judaeo-Christian thought. Such questions fostered a tendency to think it better to be “modern” than to be “ancient,” even though to classify an idea as “modern” or “ancient” tells us nothing about whether it is true or false.

This is not to disparage advances in the modern world. We have gained a greater respect for the freedom of the human person. There have been wonderful medical and technological advances. Ideas both democratic and scientific have benefitted all of us. At the same time, the lack of a common intellectual and moral sense has contributed to a century of totalitarianism and materialism which converged to wreak havoc on all peoples and on the world we share. The result, however, has been more than a matter of global movements. On the smaller scale these notions (which inevitably involve lies about God and man) are the basis also of individual moral decisions and values. Over time they have fostered a moral culture which prizes personal autonomy and subjective determination of good above all else, creating a world of “merely individualistic morality”2

The result, however, has been more than a matter of global movements. On the smaller scale these notions (which inevitably involve lies about God and man) are the basis also of individual moral decisions and values. Over time they have fostered a moral culture which prizes personal autonomy and subjective determination of good above all else, creating a world of “merely individualistic morality”2

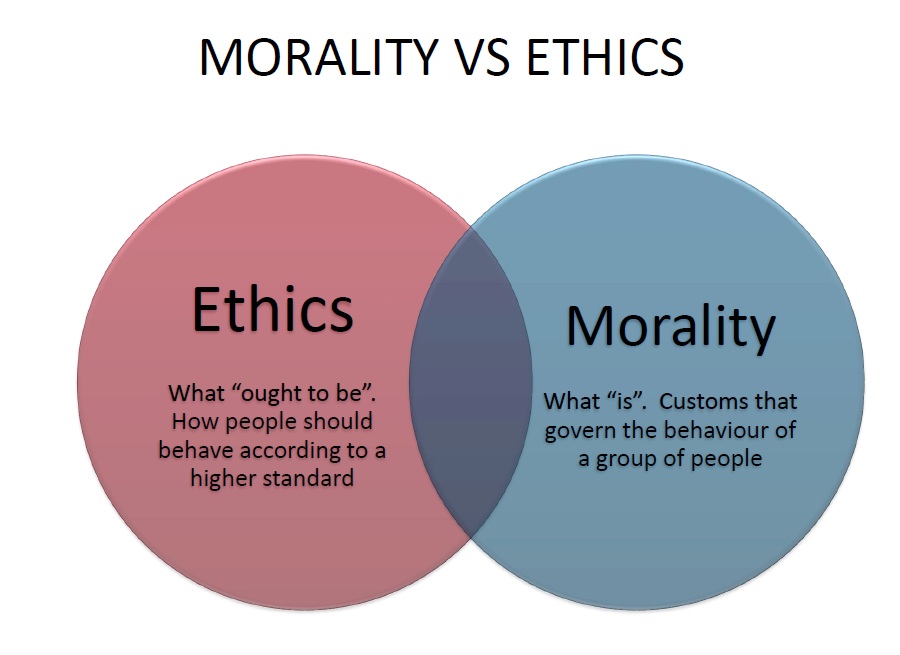

This sort of subjectivism leads to the notion that things are good or bad because they do or do not suit my preferences, because they are or are not in accord with what I think is best for me — almost like deciding what sort of car to drive or what sort of music to enjoy. Of course, preferences have a valid part to play in our lives, but mere self-centered choices will never serve as a basis for true fulfillment or as a way of serving the common good.

This is not a difficult idea to grasp. In fact, all of us (even children) make use of it all the time in our daily relations with each other. 3

3

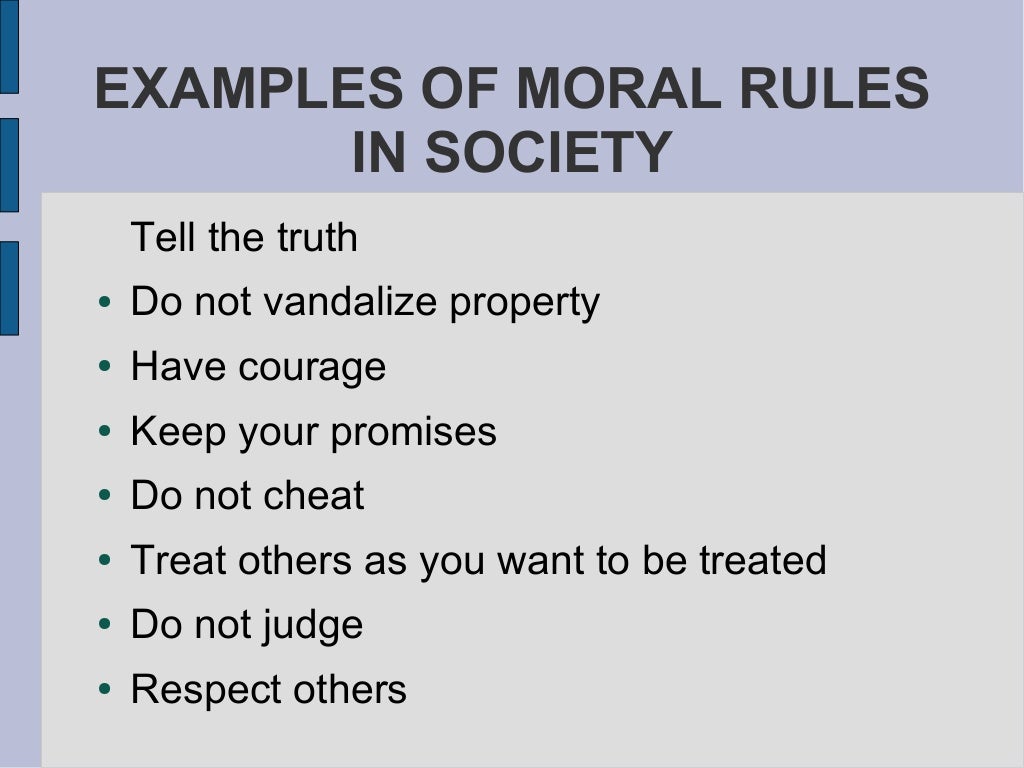

“You’re not being fair!” “You promised.” “Excuse me, but you’re in my seat.” “He was nice to you. Shouldn’t you be nice to him?” Every one of these statements, commonplace as they are, reveals something far deeper at work here. They all make sense only if the speaker is right in supposing that the listener and he share a common standard upon which both of them can and should agree — a standard of fairness or of honesty to which both of them are bound and which both should recognize. In fact, even when we don’t agree with what the speaker wants, we still are prone to try to justify ourselves on the ground of some exception to the standard rather than by simply denying the standard itself. There is an implication here of something outside of both speaker and listener, some reality that both subscribe to and which both consider important to the relationships of daily life. Indeed, that same standard is present in far greater things than the small examples I have chosen to give.

We have here a standard that we do not “make up” for ourselves, as though conscience were purely private and personal. It is an objective standard that we discover, not a subjective one that we manufacture. If we want to live in a society that respects the dignity of all persons, then it is in our interest to take a strong look at the objectivity of what is good or bad, right or wrong for all of us. To avoid the question of objective truth only pretends to allow subjectivity to reign and individualism to be sovereign, and even our simple examples show what an impossible world that would create. In such a world raw power would be decisive and pleasure would become the principle of action. But to choose such a world is to choose to act against our truest selves and against our deepest desire to love and be loved.

It is an objective standard that we discover, not a subjective one that we manufacture. If we want to live in a society that respects the dignity of all persons, then it is in our interest to take a strong look at the objectivity of what is good or bad, right or wrong for all of us. To avoid the question of objective truth only pretends to allow subjectivity to reign and individualism to be sovereign, and even our simple examples show what an impossible world that would create. In such a world raw power would be decisive and pleasure would become the principle of action. But to choose such a world is to choose to act against our truest selves and against our deepest desire to love and be loved.

We must ask ourselves the question God asked of Adam and Eve, “Where are you?” Do you accept the truth? Do you live in real love? The implications are enormous, because love fosters life and sin fosters death. If we are not building a community of love, then we are fostering what Pope John Paul II called a culture of death, a totally inhospitable place in which to live. 4 But there is another way to live: There is the truth that leads to life.

4 But there is another way to live: There is the truth that leads to life.

II. TRUTH, CHRIST, CHURCH: “I am the Way, the Truth and the Life” (Jn 14:6)

At supper with his friends on the night before his death, Jesus, fully aware of all that was about to happen, rose from the table, set aside his outer garments and fastened a towel around his waist. Then he filled a bowl with water and began to wash his disciples’ feet.5

“Do you realize what I have done for you,”6 he asked them after he had finished. If he, their master and teacher, washed their feet like a common servant, then they must do likewise for each other. “I give you a new commandment: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you also should love one another. This is how all will know that you are my disciples — if you have love for one another.”7

Jesus desires to share with his disciples the love that he shares with the Father, and he does so by an action of pure service, an act of witness to the fulness of his love. This love is no mere feeling, no noble or touching sentiment. It is a commitment, a choice to place oneself at the disposal of the other. It is demanding, so demanding that — as Good Friday proved — it will suffer death rather than fail in its commitment. It is a love almost frightening in its fidelity to the truth.

This love is no mere feeling, no noble or touching sentiment. It is a commitment, a choice to place oneself at the disposal of the other. It is demanding, so demanding that — as Good Friday proved — it will suffer death rather than fail in its commitment. It is a love almost frightening in its fidelity to the truth.

Truth is at the heart of it all. “If you remain in my word, you will truly be my disciples, and you will know the truth and the truth will set you free.”8 But even for Jesus the truth is not simply his, not simply subjective. “The words that I speak to you, I do not speak on my own. The Father who dwells in me is doing his works.”9 It is this truth of the Father that the disciples must come to learn and appreciate. That will happen through the Advocate, the Helper, the Spirit of Truth: “The Holy Spirit which the Father will send in my place will teach you everything and remind you of everything that I have told you.”10 It is the Holy Spirit who insures that the disciples — the Church — will remain in union with Jesus, who is “the way and the truth and the life,”11 and will continue to teach the truth that sets us free.

Truth is essential in our relationship to God and to each other. The foolishness of what we have referred to as relativism is in the fact that it tries to accept everything as possibly true and ends up accepting nothing as actually true. Listen to the exchange between Jesus and Pilate. Jesus said, “For this I was born and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice.”12 And all that Pilate could respond was, “What is truth?” And he went back out to try to sway the mob to spare Jesus, without the courage of truth to enable him to act on his own, free of the fear of Caesar that might have truly set Pilate free had he only known the truth. It was Jesus who was bound for trial, but it was actually Pilate who was not free. And, saddest of all, he had been within inches of the Living Truth, so close he could have reached out and touched it, but his cynicism held him back.

God has given us the means of finding the truth. He has given us faith and reason, and they are both his gifts, they are both of value in our search for truth, our search for God. Far from denigrating the power of human reason, the Church has consistently defended it. It has seen no contradiction between reason and faith, but has recognized their ordered relationship. Reason’s search for truth is not wrong, it is simply not fully sufficient in itself. It finds its fulfillment in the act of faith.

He has given us faith and reason, and they are both his gifts, they are both of value in our search for truth, our search for God. Far from denigrating the power of human reason, the Church has consistently defended it. It has seen no contradiction between reason and faith, but has recognized their ordered relationship. Reason’s search for truth is not wrong, it is simply not fully sufficient in itself. It finds its fulfillment in the act of faith.

The more we know ourselves through both reason and faith, the more we come to know the truth of our relationship to God. And the more we know of that relationship, the more we know about how we ought to live. We begin to learn the truth about what is right and what is wrong in the things we do, and that knowledge of the truth, far from limiting our freedom, actually expands it. It sets us free to do what is truly right, and in that we will find our true fulfillment.

True freedom is not, as we are sometimes prone to think, the possibility of choosing either good or evil. The possibility of choosing evil is actually a perversion of freedom. True freedom is the possibility of always being able to choose what is truly good, and that we can do only if we come to know the truth about what is right and what is wrong. Know the truth, and the truth will truly set you free.

The possibility of choosing evil is actually a perversion of freedom. True freedom is the possibility of always being able to choose what is truly good, and that we can do only if we come to know the truth about what is right and what is wrong. Know the truth, and the truth will truly set you free.

There is no contradiction between a Church that offers the love of Christ and a Church that teaches the truth which Christ embodies. Christians who endeavor to follow Christ and to live in his love should be fully disposed to learn from the witness that this Church provides.13 Its statements are not contrary to freedom of conscience, they are, rather, a statement of the truths which enable our consciences to act with true freedom.

III. CONSCIENCE: “You will know the truth and the truth will set you free.” (Jn 8:32)

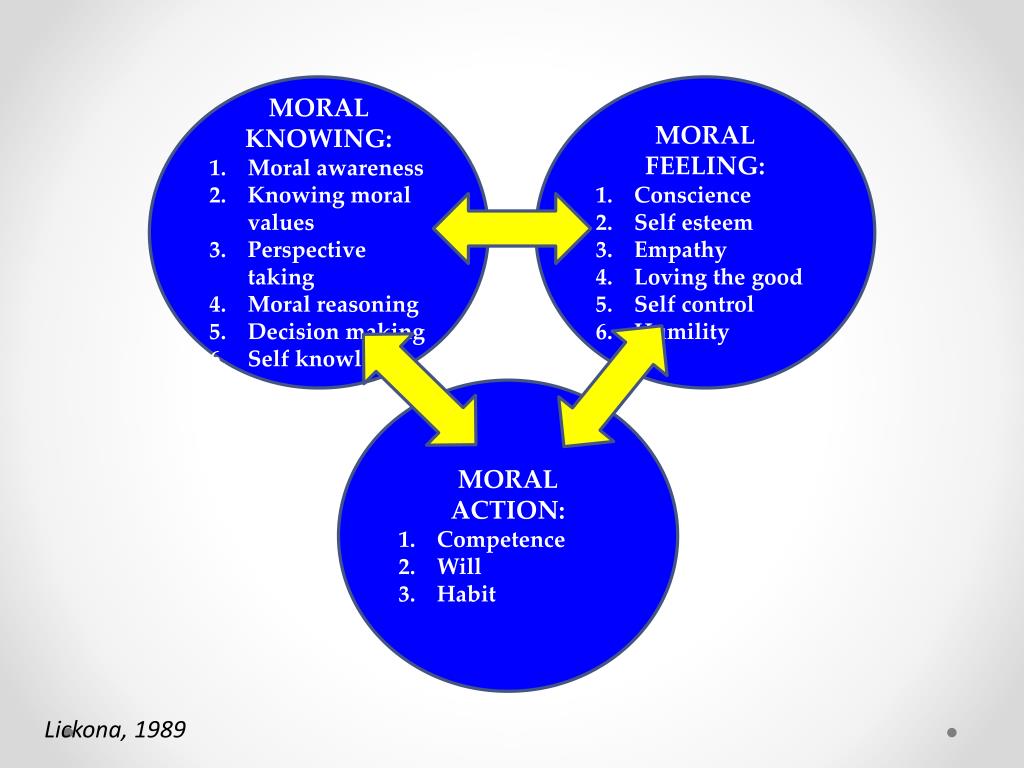

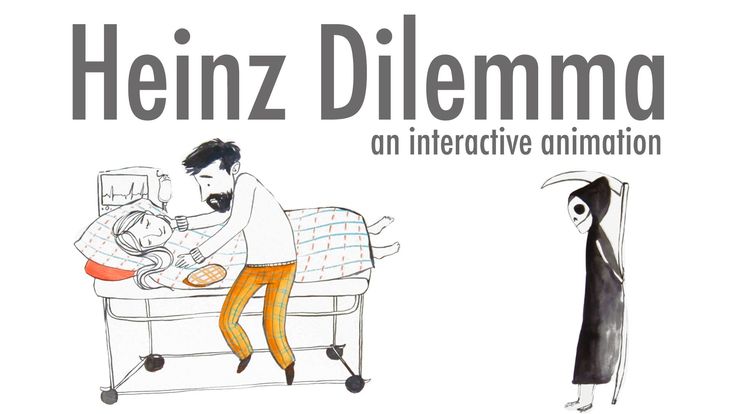

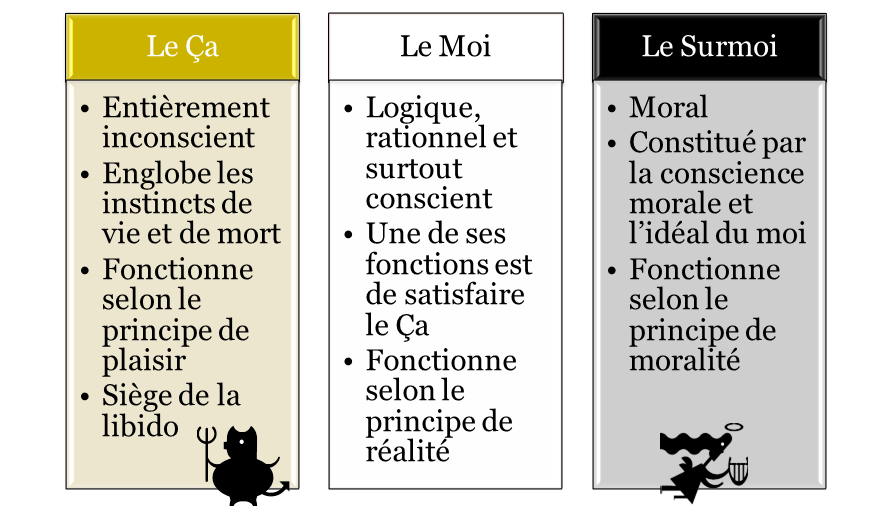

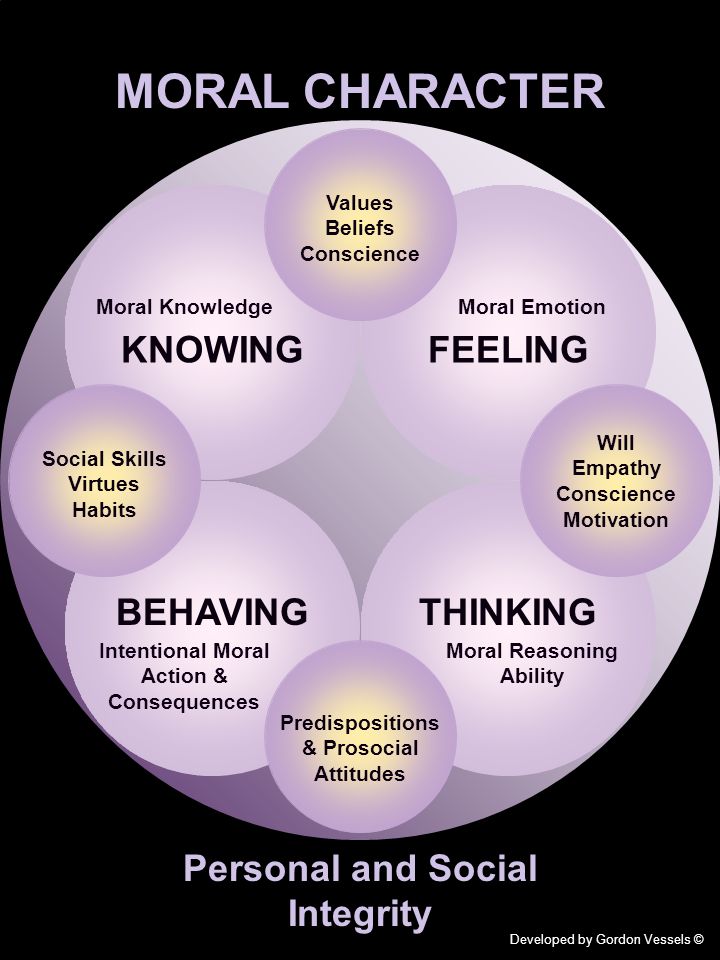

What is conscience? Is it a body of knowledge about what is right or wrong? Is it an attitude of mind, a habitual outlook on moral conduct? In fact, it is neither of those things. It is something simpler. It is an act of judgment about the morality of an action one is considering doing. “Conscience is one’s last and best judgment concernng what one should choose.”14

It is something simpler. It is an act of judgment about the morality of an action one is considering doing. “Conscience is one’s last and best judgment concernng what one should choose.”14

Conscience measures a contemplated act against the objective standard of the moral law, which is one aspect of the truth that sets us free and to which the Church bears witness. Conscience applies this law of love in the particular circumstances of daily life. For this reason, conscience is the immediate norm of our moral action as it moves us to do one thing or avoid another by making a judgment of reason about the good or evil of a particular case.15

In rendering the judgment of conscience on the moral quality of a particular act, we make use of the unity of truth as we know it — in part through natural reason (that truth “written upon our hearts,” as Paul says in Romans 2: 15) and in part through revelation. Conscience presupposes these sources of knowledge. In other words, conscience does not determine what is right or wrong, but rather makes a judgment about whether a particular proposed action is in accord with what is right or wrong and is, therefore, a good or evil action. 16This is why those people are wrong who say that morality is purely individualistic, that conscience is a wholly independent, exclusively personal capacity to determine what constitutes good or evil.17 In fact, to reduce conscience to so narrow and ineffectual a vision is actually to demean its real significance.

16This is why those people are wrong who say that morality is purely individualistic, that conscience is a wholly independent, exclusively personal capacity to determine what constitutes good or evil.17 In fact, to reduce conscience to so narrow and ineffectual a vision is actually to demean its real significance.

It is only because you and I know the same truth — whose fullness is to be found in Christ — that we can base our moral act in an operation of conscience. If decisions of conscience were no more than privately decided “truths,” we could never share a common good. Instead, it is essential that we have the capacity to know the truth and so to deliberate what act is good.

Conscience is not only our last judgment before acting, it must also be our best. However, if conscience is a human judgment, then it is also capable of error and is not infallible. This is why the Church teaches that conscience must be properly formed. It must be enabled to discern what actually does or does not correspond to the “eternal, objective and universal divine law” which human intelligence is capable of discovering. 18

18

Our freedom is a freedom for the truth and not a freedom from the truth. Otherwise there would be no possibility of sharing in a true good. This is why the Fathers of Vatican II affirmed that “through loyalty to conscience, Christians are joined to other men in the search for truth and for the right solution to so many moral problems that arise both in the life of individuals and from social relationships. Hence, the more a correct conscience prevails, the more do persons and groups turn aside from blind choice and try to be guided by the objective standards of moral conduct.”19

Clearly a person must follow conscience in order to be morally responsible. Yet no human being can realistically claim that his conscience is simply infallible, since decisions of conscience depend on conformity to the objective moral law and do not create the moral law. But if conscience can be erroneous, therein lies the potential for tragedy. In spite of all sincerity, a conscience in error neither fosters fulfillment nor serves the good. If conscience, therefore, is to serve its purpose, it must not only be sincere, it must also be correct. How sad, indeed, to be utterly sincere in what we do and to be, at the same time, utterly and sincerely wrong. Conscience needs formation.

If conscience, therefore, is to serve its purpose, it must not only be sincere, it must also be correct. How sad, indeed, to be utterly sincere in what we do and to be, at the same time, utterly and sincerely wrong. Conscience needs formation.

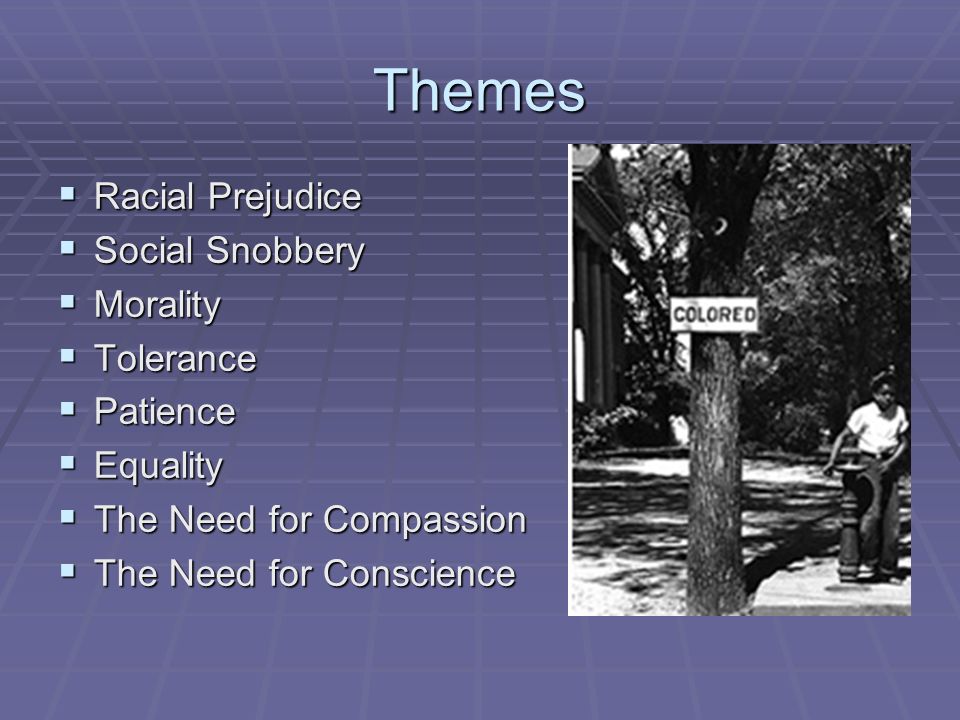

IV. FORMATION OF CONSCIENCE: “Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind, so that you may prove what the will of God is, that which is good and acceptable and perfect.” (Rom 12:2)

The importance of conscience cannot be underestimated. The judgment of conscience about the goodness or evil of a contemplated act is not only a judgment on the value of the act itself, but is also a judgment on the doer of the act. His choice of action is also his choice of his own moral state. His actions reveal what he is and even contribute to making him what he is. To choose to do good is to choose to be a moral person; to choose to do evil is to choose to be an immoral person. The judgment of conscience is crucial.

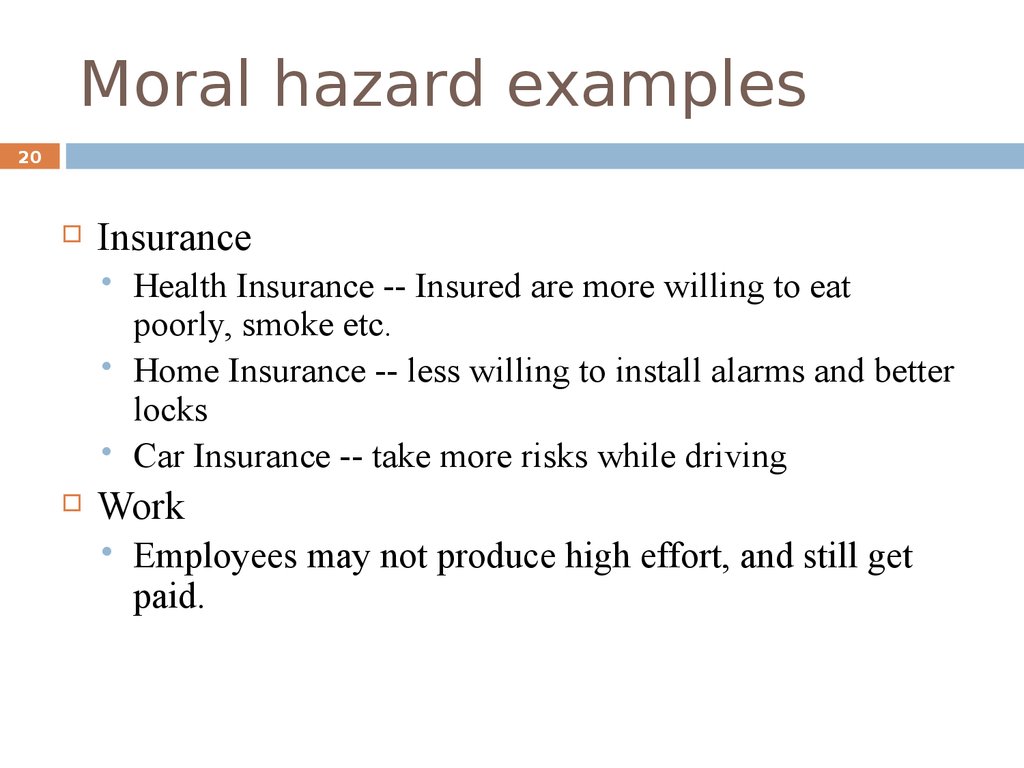

“A human being must always obey the certain judgment of his conscience. If he were deliberately to act against it, he would condemn himself.”20 It is obvious that to act against a conscientious judgment made with certitude would really be a way of doing violence to one’s own moral state. However, we must also recognize the fact that human judgment is capable of error. Even when the person making the judgment is certain that he is right, he may easily fail to grasp the question correctly or to have the full knowledge he needs or to be aware of all the facts. In such cases, the person making the judgment would be acting in good faith and would not be guilty of sin, but he would still be wrong and the evil of the act would still take place.

One may be morally blameworthy for his lack of proper judgment and his own ignorance. “This is the case when a man ‘takes little trouble to find out what is true and good, or when conscience is by degrees almost blinded through the habit of committing sin. ’ In such cases the person is culpable for the evil he commits.”21 The sources for errors in moral conduct may be varied. “Ignorance of Christ and his gospel, bad example given by others, enslavement to one’s passions, assertion of a mistaken notion of autonomy of conscience, rejection of the Church’s authority and her teaching, lack of conversion and of charity; these can be at the source of errors of judgment in moral conduct.”22

’ In such cases the person is culpable for the evil he commits.”21 The sources for errors in moral conduct may be varied. “Ignorance of Christ and his gospel, bad example given by others, enslavement to one’s passions, assertion of a mistaken notion of autonomy of conscience, rejection of the Church’s authority and her teaching, lack of conversion and of charity; these can be at the source of errors of judgment in moral conduct.”22

In either case — whether the ignorance is or is not blameworthy — one always has the obligation to take whatever steps are required to ensure that one removes that ignorance, since it is an obstacle to right judgment and therefore to right living. Such ignorance is always harmful.

Earlier we spoke of conscience as one’s last and best judgment concerning what one should choose. For that judgment to be the best judgment, one must take care to see to it that conscience (the judgment) is properly formed. Good judgment never just “happens.” It always demands insight and knowledge of both facts and values.

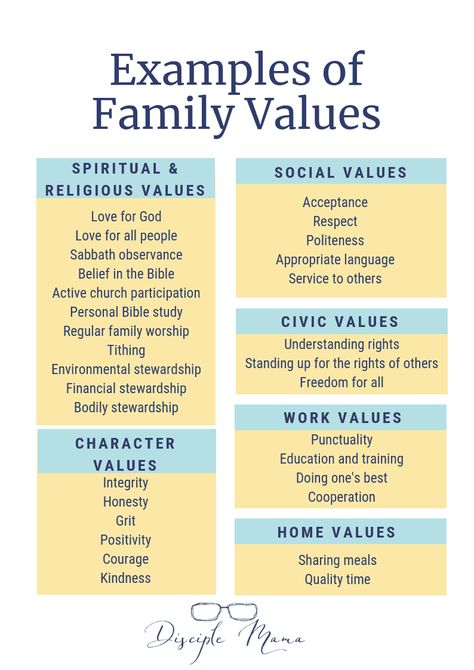

There are certain norms for formation of conscience that will apply in every case, as outlined in the Catechism of the Catholic Church: (1) One may never do evil even if the intention is that good will come of it; (2) one should do unto others as he would have them do unto himself; (3) charity always demands respect for one’s neighbor and his conscience.23

In order for conscience to be properly formed, one must make the effort to be upright and truthful. This means making every effort to form judgments of conscience based on good reasoning and on the acceptance of the true good willed by God. As human beings we are influenced by negative forces and by the temptation to sin. We are easily drawn to a false autonomy and the temptation to reject even legitimate authoritative teaching.

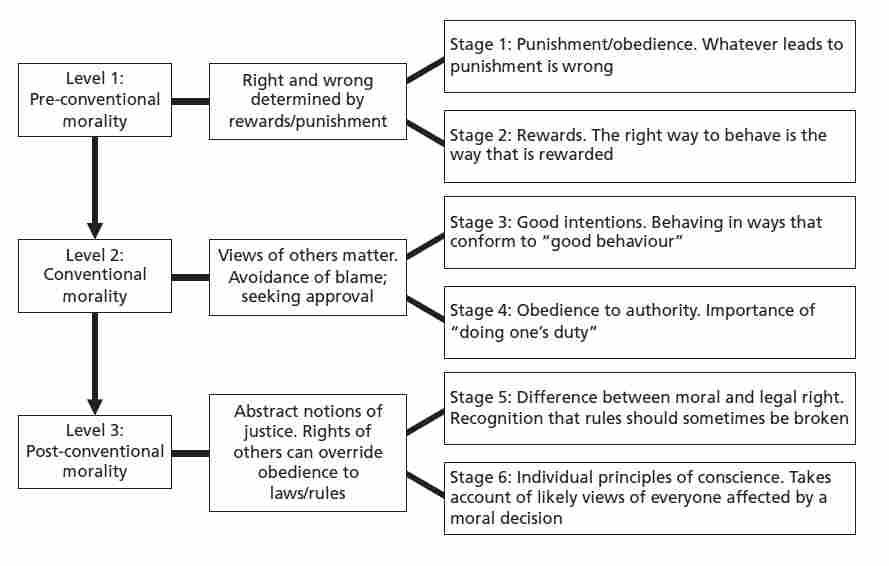

“The education of the conscience is a lifelong task. From the earliest years, it awakens the child to the knowledge and practice of the interior law recognized by conscience. Prudent education teaches virtue; it prevents or cures fears, selfishness and pride, resentment arising from guilt, and feelings of complacency, born of human weakness and faults. The education of the conscience guarantees freedom and engenders peace of heart.”24

The education of the conscience guarantees freedom and engenders peace of heart.”24

The judgment of conscience is at the heart of our relationship to God and to neighbor. It is essential to our life and happiness, since it is conscience that directs us to live in such a way as to be everything that the loving Creator intended us to be. To be otherwise is to doom ourselves to a vain quest for a happiness that cannot be attained because it does not exist. We are daily faced with choices, large and small, all of which lead us in one direction or the other. We do not always have ready answers to the situations that arise, but we are bound to have minds and hearts open to the truth that will be presented to us through reason and through faith. We are bound to listen to the voice of God as both reason and faith make it known to us.

To have a well formed conscience is not to have our freedom constrained. It is, rather, to have a freedom that is full and complete, because in every choice made on the ground of a well formed conscience we come one step nearer to God and one step nearer to what, in our heart of hearts, we truly wish to be.

CONCLUSION: “Christ lives in me.” (Gal 2:15)

The grace of baptism is the grace of new life in Christ. That new life, however, is not a static gift given for the day of baptism and remaining within us as a “relic” of the sacrament. It is, rather, a new life, a new vitality renewed each day and drawing us ever nearer to the fullness of life that will be ours in Heaven. To live in Christ is to live as another Christ. It is to live for the truth and to lay down our lives for that truth as witnesses to the gift we have received. To live in Christ is to love self and neighbor as does Christ.

This love is not a feeling. It is a steadfast willing. It is a constant choice of the good, and that good must be illuminated by the truth known to reason and fulfilled in faith. This is the function of the well formed conscience. It is a responsibility of the highest order. It is something we must all pursue, for without a conscience informed by the truth we can never find fulfillment in the love of God or love of neighbor. Only when I have the certitude of a truly well formed conscience will I be able to say in truth, “Christ lives in me.”

Only when I have the certitude of a truly well formed conscience will I be able to say in truth, “Christ lives in me.”

—

1 Catechism of the Catholic Church [CCC], 2nd edition with modifications from the Editio Typica, 1994, 1997, quoting from Vatican II, Declaration on Religious Freedom Dignitatis Humanae, 1965, n. 3 § 2.

2 Vatican II, Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World Gaudium et spes [GS], n. 30. Pope John Paul II in the Encyclical Veritatis splendor [VS], 1993, n. 32, writes: “But in this way the inescapable claims of truth disappear, yielding their place to a criterion of sincerity, authenticity and ‘being at peace with oneself,’ so much so that some have come to adopt a radically subjectivistic conception of moral judgment… there is a tendency to grant to the individual conscience the prerogative of independently determining the criteria of good and evil and then acting accordingly. Such an outlook is quite congenial to an individualist ethic, wherein each individual is faced with his own truth, different from the truth of others. ”

”

3 The ideas presented here are not original with me, but come from a delightful passage in Mere Christianity by C.S. Lewis (Macmillan Co., 1966 [8th printing], Book I, chapter 1).

4 “For us too Moses’ invitation rings out loud and clear, ‘See, I have set before you this day life and good, death and evil… I have set before you life and death, blessing and curse; therefore choose life, that you and your descendants may live’ (Dt 30:15,19). This invitation is very appropriate for us who are called day by day to the duty of choosing between the ‘culture of life’ and the ‘culture of death.’” Pope John Paul II, Encyclical Letter Evangelium vitae, 1995, n. 28.

5 Cf. Jn 13.

6 Jn 13:12.

7 Jn 13:35.

8 Jn 8: 31-32.

9 Jn 14: 10.

10 Jn 14: 26.

11 Jn 14: 6.

12 Jn 18: 37-38.

13 VS, n.64, “It follows that the authority of the Church, when she pronounces on moral questions, in no way undermines the freedom of conscience of Christians. This is so not only because freedom of conscience is never freedom ‘from’ the truth but always and only freedom ‘in’ the truth, but also because the Magisterium does not bring to the Christian conscience truths which are extraneous to it; rather it brings to light the truths which it ought already to possess, developing them from the starting point of the primordial act of faith. The Church puts herself always and only at the service of conscience, helping it to avoid being tossed to and fro by every wind of doctrine proposed by human deceit (cf. Eph 4:14), and helping it not to swerve from the truth about the good of man, but rather, especially in more difficult questions, to attain the truth with certainty and to abide in it.”

As the Second Vatican Council put it: “in matters of faith and morals, the bishops speak in the name of Christ and the faithful, for their part, are obliged to accept their bishops’ teaching with a ready and respectful allegiance of mind” (Vatican II, Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Lumen Gentium, 1964, n. 25). And always, as Vatican II noted: “[I]n forming their consciences, the faithful must pay careful attention to the sacred and certain teaching of the Church. For the Catholic Church is, by the will of Christ, the teacher of truth. It is her duty to proclaim and teach with authority the truth which is Christ and, at the same time, to declare and confirm by her authority the principles of the moral order which spring from human nature” (Dignitatis Humanae, n. 14).

25). And always, as Vatican II noted: “[I]n forming their consciences, the faithful must pay careful attention to the sacred and certain teaching of the Church. For the Catholic Church is, by the will of Christ, the teacher of truth. It is her duty to proclaim and teach with authority the truth which is Christ and, at the same time, to declare and confirm by her authority the principles of the moral order which spring from human nature” (Dignitatis Humanae, n. 14).

14 Germain Grisez, The Way of the Lord Jesus, Volume I, Christian Moral Principles, Franciscan Herald Press, 1983, p. 76.

15 Cf. VS, 34. Pope John Paul later writes: “The dignity of this rational forum and the authority of its voice and judgments derive from the truth about moral good and evil, which it is called to listen to and to express. This truth is indicated by the ‘divine law,’ the universal and objective norm of morality. The judgment of conscience does not establish the law; rather it bears witness to the authority of the natural law and of the practical reason with reference to the supreme good, whose attractiveness the human person perceives and whose commandments he accepts. ‘Conscience is not an independent and exclusive capacity to decide what is good and what is evil. Rather there is profoundly imprinted upon it a principle of obedience vis-à-vis the objective norm which establishes and conditions the correspondence of its decisions with the commands and prohibitions which are at the basis of human behavior.’” (VS, 60, quoting Paul VI, Encyclical Letter Dominum et vivificantem, 1986, n. 43.)

‘Conscience is not an independent and exclusive capacity to decide what is good and what is evil. Rather there is profoundly imprinted upon it a principle of obedience vis-à-vis the objective norm which establishes and conditions the correspondence of its decisions with the commands and prohibitions which are at the basis of human behavior.’” (VS, 60, quoting Paul VI, Encyclical Letter Dominum et vivificantem, 1986, n. 43.)

16 Cf. CCC, n. 1778.

17 Cf. Dominum et vivificantem, n. 43.

18 Cf. Dignitatis humanae, n. 3; VS, n. 60.

19 Gaudium et Spes, n. 16, emphasis added. See also Dignitatis humanae, n. 3: “On his part, man perceives and acknowledges the imperatives of the divine law through the mediation of conscience. In all his activity a man is bound to follow his conscience in order that he may come to God, the end and purpose of life. It follows that he is not to be forced to act in a manner contrary to his conscience. ”

”

20 CCC, n. 1790.

21 CCC, n. 1791, quoting Gaudium et Spes, n. 16.

22 CCC, n. 1792.

23 Cf. CCC, n. 1789.

24 CCC, n. 1784.

Moral Conscience

From the Catechism of the Catholic Church, Simplified

« prev : next »

An Inner Law (1776)

Deep within his conscience, man discovers a law which he must obey, namely to do good and to avoid evil. In his conscience (man's most secret core) he is alone with God whose voice echoes within man.

Conscience - Judge of Individual Acts (1777-1779)

Moral conscience urges a person to do good and avoid evil. It even judges his particular choices (past, present, and future) and shows God's authority. The prudent man hears God speaking in his commandments.

By conscience, the person's reason judges the morality of his actions (past, present, or future). In this judgment, man sees God's law. "Conscience is a messenger of him who speaks to us behind a veil and teaches us by his representatives. Conscience is the aboriginal Vicar of Christ" (John Cardinal Newman).

"Conscience is a messenger of him who speaks to us behind a veil and teaches us by his representatives. Conscience is the aboriginal Vicar of Christ" (John Cardinal Newman).

Every person must have sufficient interior awareness so he can hear and follow his conscience. "Turn inward, brethren, and in everything you do, see God as your witness" (St. Augustine).

An Upright Conscience Assumes Responsibility (1780-1782)

Human dignity requires an upright conscience which knows moral principles and applies them in each circumstance. Truth is recognized by prudent judgments. Whoever follows his conscience is indeed prudent.

By conscience, a person assumes responsibility. Even in evil deeds, conscience remains an inner witness to truth that the choice was evil. This true judgment makes clear that the person must seek forgiveness and choose good in the future. "Whenever our hearts condemn us, we reassure ourselves that God is greater than our hearts and he knows everything" (1 Jn 3:19-20).

Man has a right to make his own moral decisions. He cannot be forced to act contrary to his conscience, nor be prevented from acting according to his conscience, especially in religious matters.

Man's Duty - To Have a Right Conscience (1783-1785)

The person has a duty to have a true conscience which is formed by reason and seeks to know God's will. Only the educating of conscience can overcome negative influences and temptations.

This lifelong task begins with awakening the child to know and practice God's law. A prudent education teaches virtues, cures selfishness, and guarantees peace of heart.

The Word of God guides this education. Man must examine his conscience before the cross, seek the advice of others, and learn the Church's authoritative teaching.

Difficulties in Judging (1786-1789)

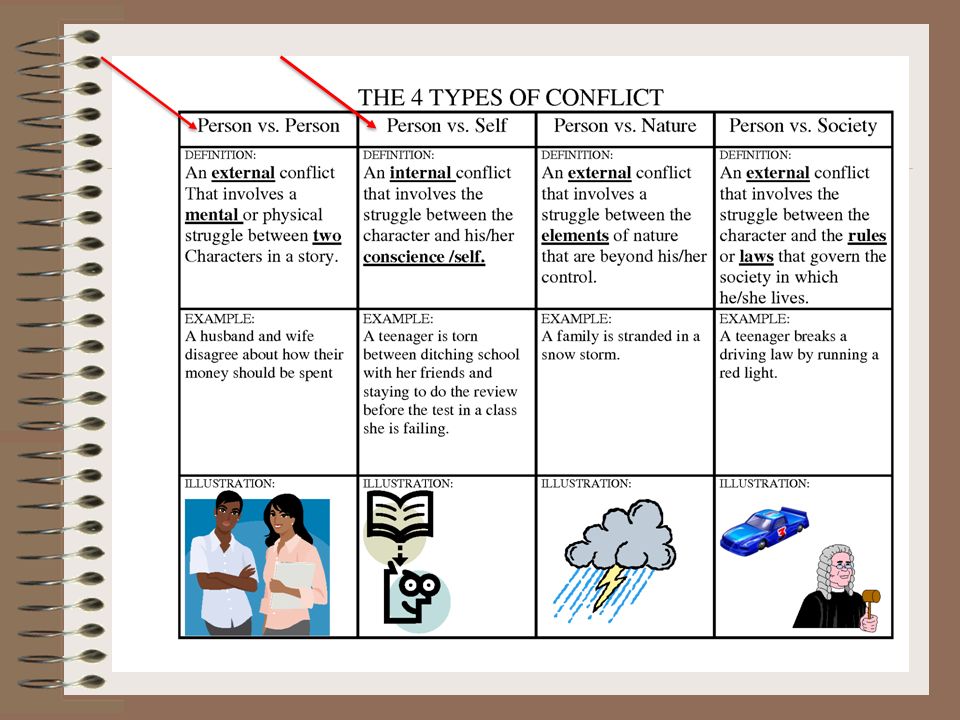

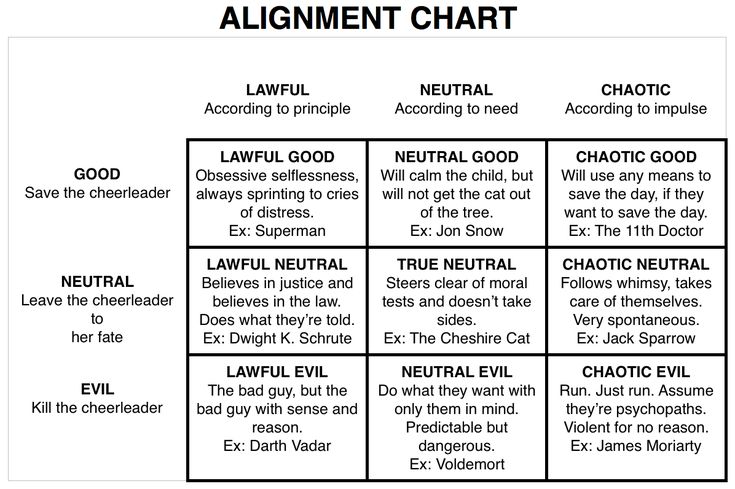

Conscience can make a right judgment (in accord with God's law and reason) or an erroneous judgment (not in accord).

In some situations, moral judgments are difficult. However, in every case, the person must seek God's will in accord with his law.

However, in every case, the person must seek God's will in accord with his law.

The person must interpret the data, assisted by his own prudence, competent advice, and the help of the Holy Spirit.

In all cases, evil can never be done so good can result. "Whatever you wish that men would do to you, do so to them" (Mt 7:12). "Do nothing that makes your brother stumble" (Rom 14:21).

Sources of Errors in Judgment (1790-1792)

Although a person must always obey the certain judgments of his conscience, he might be in ignorance and make erroneous judgments.

Sometimes, the person is to blame for having an erroneous conscience because he took no effort to discover the truth. In this case, he is responsible for the evil he commits.

There are several sources of these errors in judgment: ignorance of Christ and of his Gospel, bad example from others, enslavement to passions, lack of conversion of heart, and rejection of the Church's teaching.

Unable to Overcome (1793-1794)

Sometimes, the person is not responsible for his erroneous judgment because he cannot overcome the obstacles to truth. This is called "invincible ignorance." Although evil is present, the person is not blameworthy. He should work to correct his errors.

This is called "invincible ignorance." Although evil is present, the person is not blameworthy. He should work to correct his errors.

Conscience must be enlightened by faith so that persons and groups will turn aside from blind choices.

« prev : next »

Pray to Save America — Only $1

Join the movement! Pray 12-minutes a day to help God save America. order » Join the movement! Pray 12 minutes a day to help God save America. order »

Our supporters have distributed tens of millions of life-changing Catholic gifts since 1991, making us America's largest producer of high-quality, super-affordable tools for evangelization. Join our work today!

See All Our Catholic Materials

Purple Scapular = Family Protection

Meet Bud Macfarlane, Our Founder

Donate to Help Us Reach Millions

Pray with Us to Save America

Moral law and conscience - Germogen Ivanovich Shimansky

Germogen Ivanovich Shimansky

Download

epub fb2 pdf Original: pdf2Mb

Contents

The concept of moral law Moral law and physical law. Their similarities and differences Origin of the moral law Natural moral law. ConscienceDifferent states of conscienceThe meaning of conscience for the moral life of a person. The conscience of a person who has turned to God and lives a truly Christian life nine0003

Their similarities and differences Origin of the moral law Natural moral law. ConscienceDifferent states of conscienceThe meaning of conscience for the moral life of a person. The conscience of a person who has turned to God and lives a truly Christian life nine0003

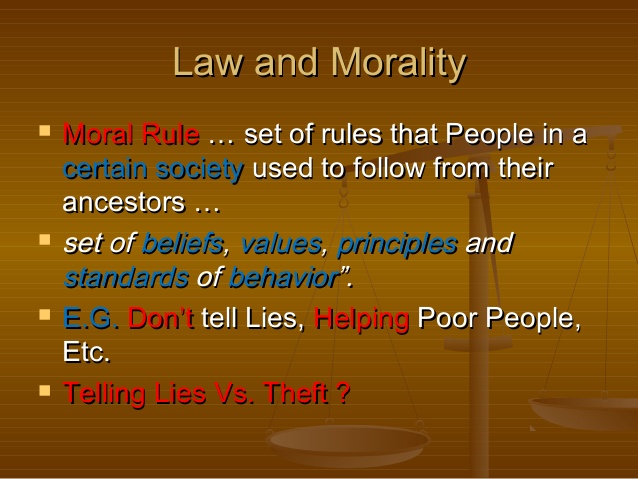

The concept of the moral law

In addition to freedom and self-awareness, the third condition for moral activity is the moral law.

What is the moral law?

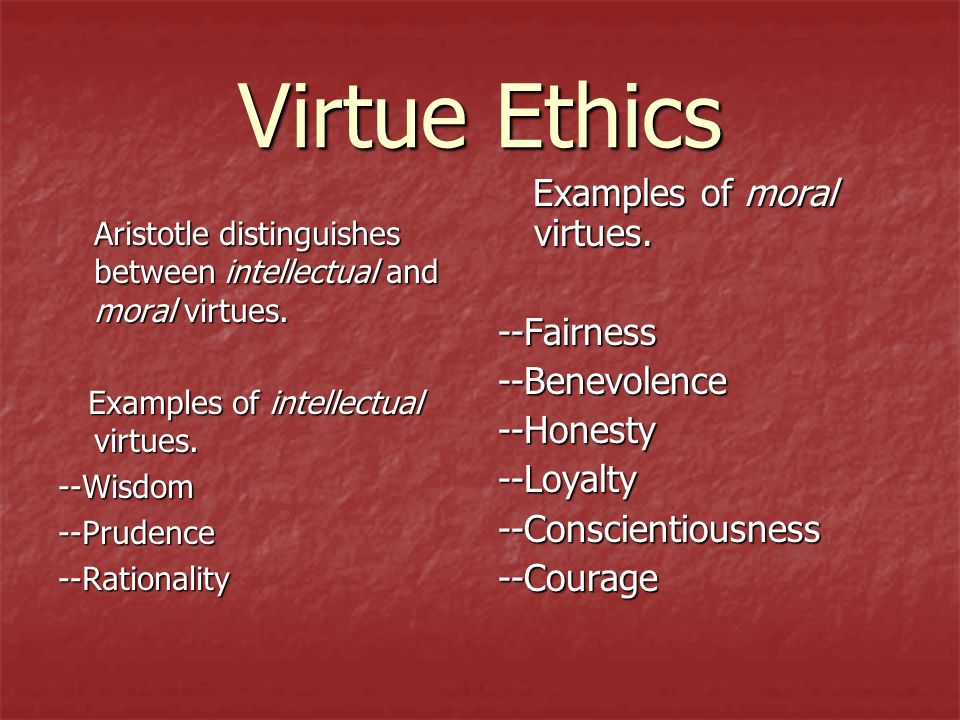

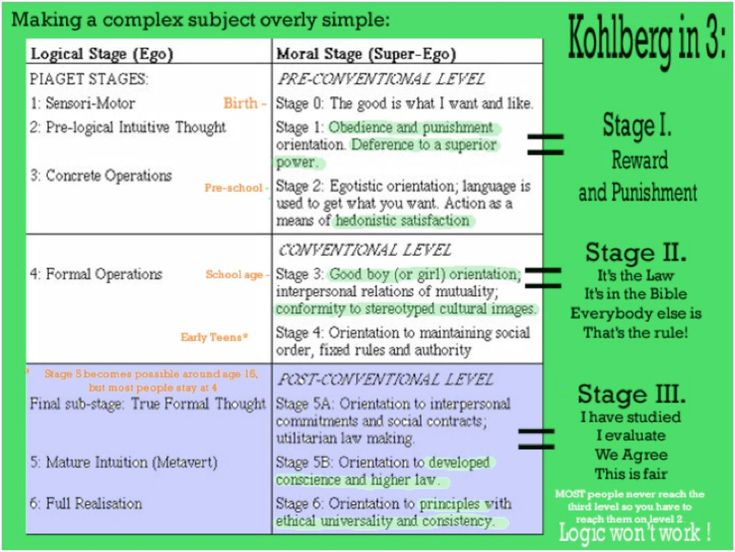

When a moral feeling is realized and repeatedly manifests itself in us regarding our intentions and actions, then it leaves a deep imprint on us. Our consciousness and thinking then already constantly turn to the movements of the moral feeling. In this way, moral concepts, or rules of free moral action, are formed in us, which is called the moral law.0025 1 . The moral law is a consciousness based on a moral sense of what should and should not be done.

In general, a law is a rule or a set of rules that determine the operation of any force. For example, the mechanical law of gravity determines the action of gravity.

For example, the mechanical law of gravity determines the action of gravity.

The moral law determines the mode of action of our moral force, i.e. free will. This means that the moral law indicates how a person should live, what he should do in order to achieve his destination or his moral goal. nine0003

Moral law and physical law. Their similarities and differences

Laws can be of two kinds - physical and moral. The former determine the activity of the forces and beings of the physical world that do not have consciousness and freedom, while the latter determine the activity of morally rational beings acting freely and with consciousness (i.e. people).

A distinctive feature of any law is its universality and necessity. The moral law also has these properties. It is universal, since the very law that I hear in my conscience is heard in myself by all other people: there is not a single person, not a single tribe or people who would not realize that one should do and the other should be avoided. It is necessary; this means that it contains an indispensable requirement in relation to a person who wants to achieve his moral goal. There is no other way to this goal than the way of fulfilling the law. nine0003

It is necessary; this means that it contains an indispensable requirement in relation to a person who wants to achieve his moral goal. There is no other way to this goal than the way of fulfilling the law. nine0003

Being similar in these features to the physical law (also universal and necessary), the moral law at the same time

differs from the physical law. The physical law determines the activity of the forces and beings of the physical (material) world, the moral law determines the activity of morally reasonable and free beings. The physical law is the law of the quantity of forces: it consists in a simple relation between cause and effect. The moral law is the law of the quality of forces: it contains the concepts of good and evil, which are completely alien to the physical law. nine0003

In terms of universality, the difference between the moral law and the physical law lies in the fact that the physical law is implemented everywhere in the same way. The moral law is not fulfilled by different people in the same way: the same requirement of the moral law (for example, the requirement of self-sacrifice) is fulfilled differently depending on the personality of each person, his position, gender, age, etc. One, for example, sacrifices himself like a warrior, defending their Fatherland; another as a doctor, a third as a scientist, a fourth as a pastor of the Church, a fifth as a worker, and so on. One in self-sacrifice dies, the other fights. Everyone acts in accordance with his individual position in the moral world and in accordance with the difference in the tasks set by God for different people. When the Apostle Paul inspires Roman Christians to test that there is the will of God, good, pleasing and perfect, he means to induce them to recognize and fulfill not only the general requirements of the moral law, which apply equally to everyone, but also those that were set. by the will of God precisely to them, precisely in the position in which they were, and with those spiritual gifts that they possessed. nine0003

One, for example, sacrifices himself like a warrior, defending their Fatherland; another as a doctor, a third as a scientist, a fourth as a pastor of the Church, a fifth as a worker, and so on. One in self-sacrifice dies, the other fights. Everyone acts in accordance with his individual position in the moral world and in accordance with the difference in the tasks set by God for different people. When the Apostle Paul inspires Roman Christians to test that there is the will of God, good, pleasing and perfect, he means to induce them to recognize and fulfill not only the general requirements of the moral law, which apply equally to everyone, but also those that were set. by the will of God precisely to them, precisely in the position in which they were, and with those spiritual gifts that they possessed. nine0003

The moral law differs from the physical law in terms of necessity. Necessity is possible twofold: unconditional and conditional.

Unconditional necessity dominates physical nature: here the law goes directly into action. Physical law operates with absolute necessity, excluding any intention or purpose, any preselection of means.

Physical law operates with absolute necessity, excluding any intention or purpose, any preselection of means.

The moral law, acting with conditioned necessity, expresses in itself a demand to which moral beings are not forced, but only obligated; this means that the requirements of the moral law are fulfilled by a person only when a person recognizes these requirements as obligatory for himself. nine0003

Thus, the moral law is conditioned by its recognition by the human free will. It appears as a requirement, always leaving room for consideration, reasoning, decision. The conditional necessity of the moral law is called obligation.

Commitment is conduct without coercion.

For example, the moral law obliges to be merciful, but does not force it. A person may not fulfill this requirement of the moral law. However, this does not mean that if the requirement of the moral law is not fulfilled, the latter (law) is canceled and destroyed in its objective meaning. nine0003

nine0003

The moral law remains the law, but, not achieving its confirmation by a person in a positive way (by fulfilling his requirements), it achieves its confirmation in a negative way. It acts against the deviation of a person from it and brings on him those pernicious consequences that are inseparable from the deviation of any object from its being, i.e. entails self-decomposition, self-destruction, continuing until the person again submits to the requirements of the law. If you do not ... listen (to the commandments of God) - you will girdle the sword (the sword will devour you) (Is. 1:20), - the prophet testifies. nine0003

The origin of the moral law

Where did the moral law come from and how was it formed in man? Naturalists, and generally moralists of the empirical direction, derive the moral law from experience, from empirical knowledge of nature. The idea of obligation, in their opinion, is not an original idea that essentially belongs to human nature, but is an a posteriori idea, formed over time: it is generated by civilization and transmitted from generation to generation. It was formed, like all morality in general, out of benefit and sympathy, i.e. from the involuntary attraction of people to a profitable life and to sympathy for their kind. nine0003

It was formed, like all morality in general, out of benefit and sympathy, i.e. from the involuntary attraction of people to a profitable life and to sympathy for their kind. nine0003

But the following evidence speaks against this theory.

There are no moral actions in external nature, everything happens in it according to the law of quantitative forces, and only we ourselves attach moral significance to something in it.

This means that external nature cannot be the source of the moral law.

In unreasonable nature, laws operate that are completely indifferent to all those norms of moral behavior that we consider obligatory for ourselves. She showers people with her gifts with equal generosity or strikes with disasters, both the righteous and the sinners. An avalanche rolling down from a fire-breathing mountain can devastate entire cities and villages; an opportune rain can save the population of an entire region from starvation, but we do not call either phenomenon morally good or morally bad. In the same way, we now express moral condemnation of animals for the harm they have caused us or for the help and benefit they have rendered us. All this testifies to the fact that external nature cannot be the source of moral principles. nine0003

In the same way, we now express moral condemnation of animals for the harm they have caused us or for the help and benefit they have rendered us. All this testifies to the fact that external nature cannot be the source of moral principles. nine0003

In addition, this theory is opposed by the universality of the moral law and the impossibility of canceling its requirements: if only a person discovered that the idea of duty has no essential meaning for him, that it is not fundamentally connected with human nature, then he could easily free himself from this idea. However, in reality, a person is never able to do this. He may refuse to fulfill the requirements of the moral law, but in the depths of his being he will recognize that these demands that he has not fulfilled still appeal (turn) to his will, still reign over him, present their rights to him, insisting on them. performance. nine0003

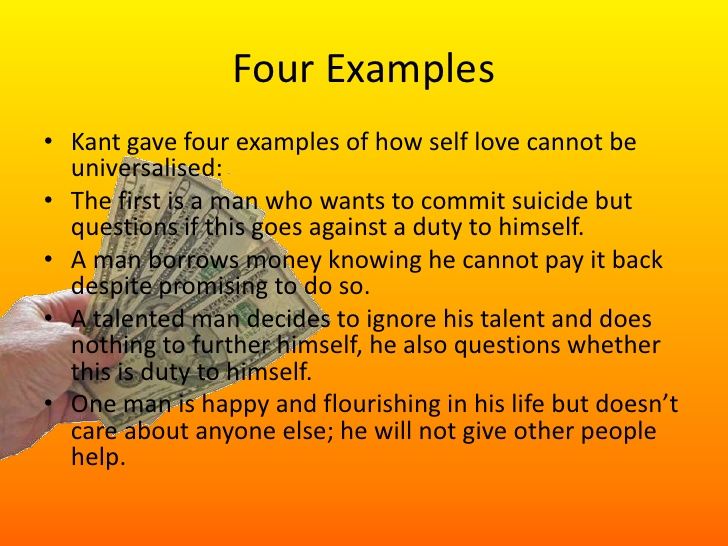

The impossibility of explaining the origin of the moral law from external experience led Kant to the conclusion that the moral law is, as it were, the product of the pre-experimental activity of "pure reason". Reason, according to Kant and his followers, gives itself a law in the unconditional and absolute form of a categorical imperative (command) - "you must" (of course, do this or that). But how our mind deduces from itself such a law, which we must fulfill only out of respect for it, is, according to Kant, unacceptable for human knowledge, it is an impenetrable mystery. nine0003

Reason, according to Kant and his followers, gives itself a law in the unconditional and absolute form of a categorical imperative (command) - "you must" (of course, do this or that). But how our mind deduces from itself such a law, which we must fulfill only out of respect for it, is, according to Kant, unacceptable for human knowledge, it is an impenetrable mystery. nine0003

That the moral law takes the form of a law, i.e. rules that determine our internal and external behavior, only through thinking, therefore, through the mind - this is understandable. However, the human mind is not such an authority that could order "imperatively" (imperiously) and insist on the indispensability of the execution of orders. If the mind orders "imperatively", then it could also cancel these orders, i.e. annul the requirements of the moral law. However, this does not happen. nine0003

All this testifies that one cannot agree with the opinion of Kant, who recognizes the human mind as the primary source of the moral law. True, the content of the moral law, i.e. rules of moral behavior, our mind develops itself on the basis of repeated stimulation of moral consciousness and moral feeling. But to be aware and to process moral phenomena in one’s heart, and then to process ideas about them into norms or rules of the moral law, does not yet mean creating a law for oneself, but means only interpreting it as something already given to the moral need of human nature. nine0003

True, the content of the moral law, i.e. rules of moral behavior, our mind develops itself on the basis of repeated stimulation of moral consciousness and moral feeling. But to be aware and to process moral phenomena in one’s heart, and then to process ideas about them into norms or rules of the moral law, does not yet mean creating a law for oneself, but means only interpreting it as something already given to the moral need of human nature. nine0003

The impossibility of explaining the origin of the moral law from experience and from the activity of pure reason leads to the conclusion that moral consciousness and feeling are inborn in us. Our inherent ability to distinguish between good and bad in our behavior, obviously, is the very nature of our spirit, our mind. The innateness of our moral consciousness to us is also confirmed by the biblical teaching about the God-likeness of the human soul. God created man in His image and likeness, and since God, by His very essence, is the highest good or good, then we, His god-like creatures, bearing the imprint of this good in our souls, by our very nature tend to distinguish between good and evil. and strive only for the first, and turn away from the second. nine0003

and strive only for the first, and turn away from the second. nine0003

Thus, the source of the moral law must be assumed in the will of God. The will of God, being the law for the whole world, serves as the basis of the moral law for all rationally free beings. From this the imperious authority of moral demands is easily explained. There is one Lawgiver and Judge (James 4:12), says the Apostle James. All nature obeys the will of God, it is fulfilled by the Angels, for its fulfillment Christ Himself came to earth, and all people must recognize and fulfill it.

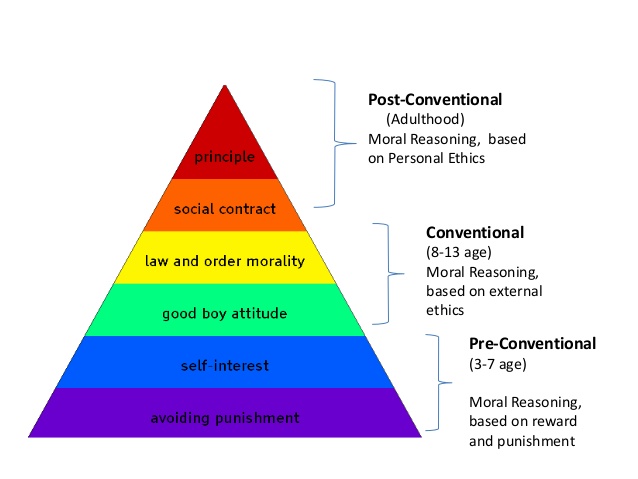

Natural moral law. Conscience

The will of God becomes known to man in two ways: firstly, through his own inner being and, secondly, through Revelation, or positive commandments, communicated by God and the incarnate Lord Jesus Christ and written down by the prophets and apostles.

The first way of communicating the will of God is called internal, or natural, the second - external, or supernatural. In other words, the will of God is communicated to man through the internal, or natural, moral law and through the positive, or revealed, moral law given through Divine Revelation. nine0003

In other words, the will of God is communicated to man through the internal, or natural, moral law and through the positive, or revealed, moral law given through Divine Revelation. nine0003

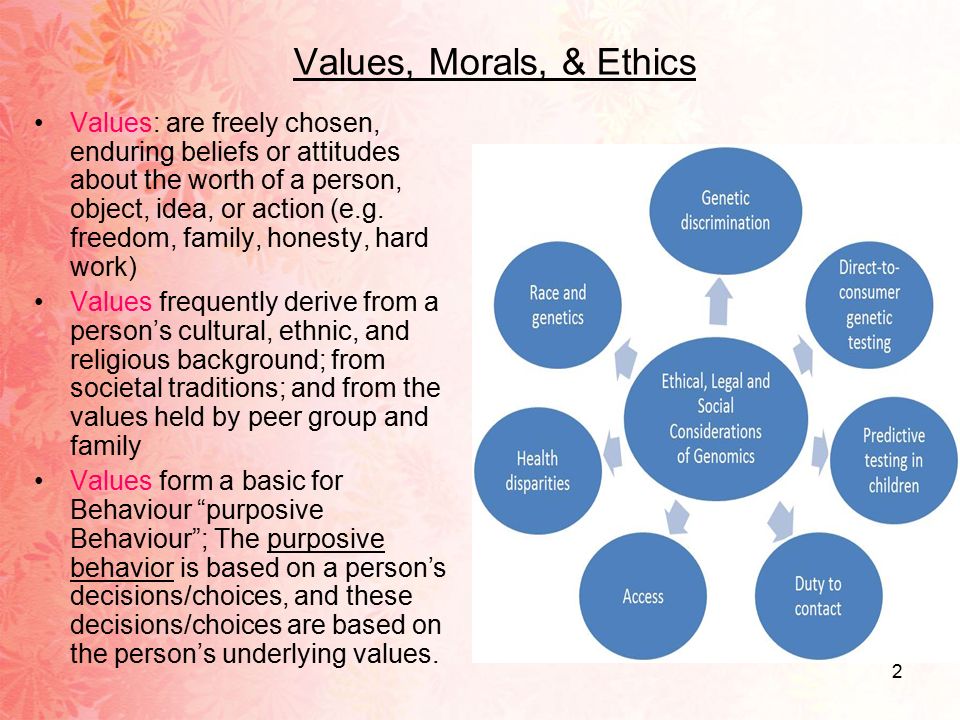

The beginning of morality is innate in man. Each of us by nature is able to discern the quality of our actions and to feel in our soul contentment or dissatisfaction with our actions. This is the so-called natural moral law, embedded in our nature, in our nature by the Creator.

Under the name of the natural moral law is meant that internal law inherent in our soul, which through reason and conscience shows a person what is good and what is evil, what he should do and what should be removed 2 .

0 the existence of a natural moral law in us speaks to everyone, first of all, his own consciousness. Delving deep into ourselves, we hear in ourselves some kind of voice (conscience), which, pointing out to us the difference between good and evil, prescribes one thing to do and the other to avoid. This law is so deeply rooted in our nature that no one can get rid of it, erase it or stifle it. It is known and felt by all peoples and all nations of the earth, for there is not a single person who would not be aware of the difference between good and evil, and also of what good should do, and evil should be avoided and removed. nine0003

This law is so deeply rooted in our nature that no one can get rid of it, erase it or stifle it. It is known and felt by all peoples and all nations of the earth, for there is not a single person who would not be aware of the difference between good and evil, and also of what good should do, and evil should be avoided and removed. nine0003

The existence of a natural moral law in man is also confirmed by Holy Scripture. Thus, the apostle Paul speaks of the pagans, that they, having no (revealed) law, "work by the lawful nature," i.e. by nature do what is lawful; not knowing the law (written), they are their own law; they show that the work of the law is written in their hearts, as evidenced by their conscience and thoughts, now accusing, now justifying one another (Rom 2:1 4-15).

The Holy Fathers reason in the same way. St. John Chrysostom writes: “Neither Adam nor any other person, it seems, has ever lived without the natural law... As soon as God created Adam, put this law into him, making him a reliable cohabitant for the entire human race” 3 . Saint Isidore Pelusiot says: "Truly, those who fulfill the duty of inculcating the natural law are worthy of praise" 4 . For nature itself bears in itself an exact and uncorrupted criterion of virtues, to which Christ Himself points in the form of stimulus or encouragement, saying: In everything you want people to do to you, do to them the same way (Matt. 7:12) .

Saint Isidore Pelusiot says: "Truly, those who fulfill the duty of inculcating the natural law are worthy of praise" 4 . For nature itself bears in itself an exact and uncorrupted criterion of virtues, to which Christ Himself points in the form of stimulus or encouragement, saying: In everything you want people to do to you, do to them the same way (Matt. 7:12) .

Guided by this internal natural law, humanity developed not only separate moral rules, but also created a whole moral worldview, developed certain customs and mores, which are nothing more than unwritten laws that, according to legend, passed from generation to generation and became the source of all written laws. These laws served as a guide in public life and, however imperfect they may be, nevertheless restrained gross arbitrariness, violence and licentiousness in human societies. nine0003

The bearer and exponent of the natural moral law is the conscience (from the verb "know", "know", "co-know", hence - "consciousness"). The very name "conscience" indicates that conscience is, first of all, consciousness, but consciousness is special (of a kind).

The very name "conscience" indicates that conscience is, first of all, consciousness, but consciousness is special (of a kind).

We learn about the operation of the moral law by our inherent sense of conscience, or, as they say, “the voice of conscience.” Since ancient times, conscience has been called the voice of God in a person’s soul, and in one of the books of the Old Testament Scripture it is represented as the eye of God: He laid His eye on their hearts (Sir 17, 7). Conscience really can and should serve as an internal organ for the revelation of God's will to man. “When God created man,” says the Monk Abba Dorotheos, “He instilled something Divine into him, like a certain thought, having in itself, like a spark, both light and warmth; thought that enlightens the mind and shows it what is good and what is evil - this is called conscience, and it is a natural law ... Following this law, i.e. conscience, the [Old Testament] patriarchs and all the saints before the written law pleased God. 0025 5 .

0025 5 .

An uncorrupted conscience is a constant judge of our feelings and thoughts, our best friend and adviser, the first comforter in trouble and misfortune, and an inexorable executioner in case of violations of the moral law. How reproaches and pangs of conscience can be strong and at the same time inevitable, we see from the story in the "Spiritual Meadow" (ch. 136) about the repentant thief (see also Cheti-Minei, June 4). “A criminal can sometimes escape the judgment of man,” says St. Gregory the Theologian, “but he will never escape the judgment of his own conscience.” nine0003

How reproaches and pangs of conscience can be strong and at the same time inevitable, our poet Pushkin perfectly expressed this in the image of a criminal who is haunted by his crime with a bloody shadow all his life, poisons all the minutes of his peace and pleasure, corrodes his family happiness, so what he says:

And glad to run, but nowhere!

Yes, pitiful is he who has an unclean conscience!

Shakespeare portrays the torments of conscience both in the dream and in reality of King Richard III, when he suffers a well-deserved punishment for all murders and crimes. Desperate king says:

Desperate king says:

My conscience has a hundred tongues,

And everyone tells me a hundred fairy tales

And in every fairy tale he calls me a monster.

I betrayed oaths, and terrible oaths...

I killed, and I killed terribly... sinful, sinful!”

Despair gnaws at me... No one

Of all people can love me...

I'll die - and who will cry for me? nine0003

If conscience approves good thoughts, feelings and deeds of a person, then it has a negative attitude towards evil, sinful moods and deeds: it does not approve of them, immediately convicts a person, arousing a sense of guilt, blaming a person before and during, especially after committing a sin.

Conscience is a universal human phenomenon. Her voice is heard in every human heart. But speaking of the innate conscience, one must keep in mind that it is not given to us in a ready-made form, but in the form of a natural moral feeling; from this feeling, with the participation of reason and will, a natural moral law is gradually formed through development. nine0003

nine0003

The natural moral feeling, like any feeling in general, develops gradually. Initially, this feeling is weak and tender. It develops along with the general development of the human spirit, acquiring a greater and greater degree of consciousness of duty. The awareness of this moral feeling, its particular content and the manifestation of this feeling as a law are strongly influenced by the moral character of the mother, father, relatives and other persons surrounding the child, home education, the environment with its mores, customs and traditions, and nature of religious beliefs. The influence of all these circumstances explains the fact that the concepts of good and evil, both among all peoples and among individuals, are different, and, consequently, the conscience is different. History and life show us that people sometimes accept as morally good what others reject. For example, the inhabitants of the Caucasus considered it their sacred duty to take bloody revenge for the murder of their relatives, which was considered a vice by other people. Or the Spartans (the inhabitants of ancient Sparta) considered it perfectly natural to kill newborn babies if they were physically weak, an act that disgusts us. The conscience of pagan peoples once not only justified, but also sanctified with religion human sacrifices, wild orgies in honor of Bacchus, acts of bloody revenge, the killing of decrepit old people, etc. People sometimes committed the most cruel acts, even terrible crimes, referring to the voice of their conscience (for example, in the Middle Ages, the executions of the Inquisition). nine0003

Or the Spartans (the inhabitants of ancient Sparta) considered it perfectly natural to kill newborn babies if they were physically weak, an act that disgusts us. The conscience of pagan peoples once not only justified, but also sanctified with religion human sacrifices, wild orgies in honor of Bacchus, acts of bloody revenge, the killing of decrepit old people, etc. People sometimes committed the most cruel acts, even terrible crimes, referring to the voice of their conscience (for example, in the Middle Ages, the executions of the Inquisition). nine0003

Thus, conscience is dependent on everything in the aggregate mental and especially moral state of a person. And since in the mental, and especially in the moral sense, the state of both an individual person and entire nations is perverted, for this reason the voice of conscience among people is heard very different, even contradictory.

Different states of conscience

6 Being equally inherent in every person, conscience is very different in different people, even in the same person it does not always act in the same way. It is not uncommon to meet people who, at different periods of their lives, are sometimes more or less conscientious, sometimes condemning, sometimes justifying the same phenomena in the moral field. There are people who seem to have completely lost their conscience, drowned it in themselves. nine0003

It is not uncommon to meet people who, at different periods of their lives, are sometimes more or less conscientious, sometimes condemning, sometimes justifying the same phenomena in the moral field. There are people who seem to have completely lost their conscience, drowned it in themselves. nine0003

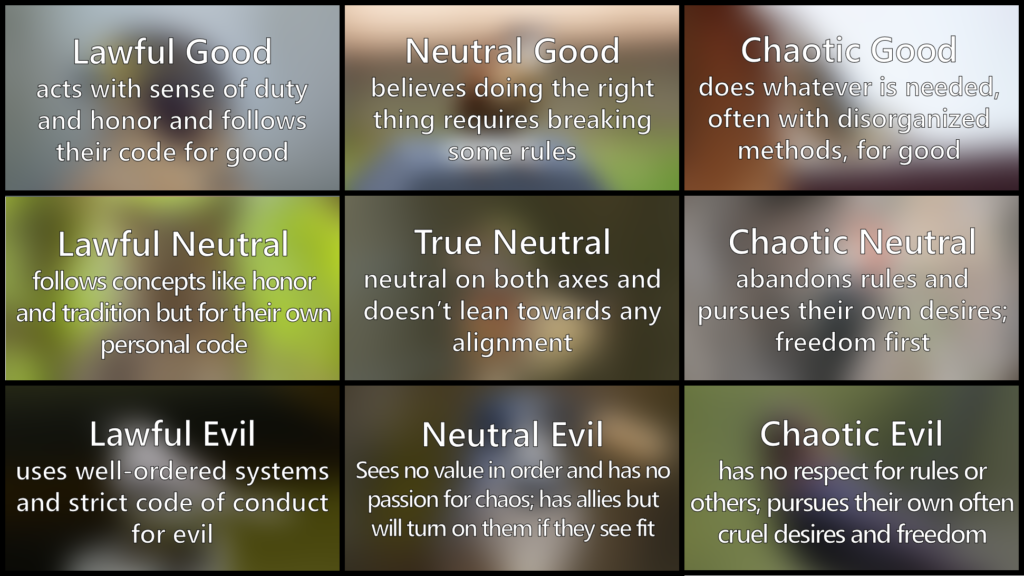

The voice of a person's conscience can be true or untrue, and both are manifested in his soul to varying degrees.

In Holy Scripture, the conscience is called, on the one hand, good or good, beautiful, pure, immaculate 7 , and on the other hand, vicious or evil, defiled, weak, burned 8 and yet - deluded or weak 9 .

By actions (functions) in conscience they see a legislator, a witness or a judge, a punisher. There is a big difference

in her actions in the soul of a good Christian and in the soul of a sinner who has fallen away from God. If conscience is the voice of God in the

soul (legislator), His eye (witness) and vicar of His justice (judge and retributor), then when a person falls away from God, all these, so to speak, Divine influences, influxes through the spirit, weaken and decrease . In addition, the forces of the soul (reason,

In addition, the forces of the soul (reason,

will and feelings), through which the conscience is revealed, are upset, therefore, correct activity cannot be expected from the conscience. nine0003

Deviations of conscience from the paths of truth are involuntary and unintentional (delusions) and there are intentional - distortions or damage to conscience from counteracting it in favor of vices and passions. All this is reflected in the indicated actions or functions of conscience.

Let us point out deviations, distortions of conscience in its functions (actions).

As a legislator, conscience can be ignorant, wavering and erring.

The business of conscience as a legislator is to show the moral laws according to which a person must act. First of all, conscience should indicate to a person the main principle in his moral activity, which is required of him by the will of God, the main direction of all his aspirations, thoughts and actions. nine0003

But it often happens that a person's conscience is silent in this respect, is in ignorance (see: Acts 17:30). Therefore, it happens that a person considers the most important thing in life that in reality is not the main thing. For example, someone puts above all only going to church services, not doing useful work, like everyone else, the main thing is his profession, the third is serving one of the types of art, the fourth considers the study of a scientist the most important, etc.

Therefore, it happens that a person considers the most important thing in life that in reality is not the main thing. For example, someone puts above all only going to church services, not doing useful work, like everyone else, the main thing is his profession, the third is serving one of the types of art, the fourth considers the study of a scientist the most important, etc.

But when the conscience is ignorant of the main thing (regarding the law of God), then in particular actions and cases it is vacillating, short-sighted. In all particular cases, conscience fluctuates between "yes" and "no", often leaves a person to act at random, at the behest of circumstances, without inner assurance and approval of what is good and what is bad. nine0003

The legislative conscience is even more damaged and distorted when it is subjected to the influence of egoism in a person and submits to it. Here, at first, its laws are reinterpreted, then they are perverted, and finally they are replaced by completely different ones, self-willed and even contradictory to the true law of God. It turns out this is how. We willingly believe what we love, what we like, and we strongly desire that the truth be on the side of the beloved, on the side of our selfish inclinations. Therefore, if in ourselves we hear the voice of conscience with a commandment contrary to our inclination, then already at the very beginning it has less conviction for us than the demand of the heart. Reflection, doubt, bewilderment is born in the soul as to the true meaning of the commandment: whether it generally fits the given case and my position, and so on. The fulfillment of the demand of the voice of conscience is postponed, and then, under the influence of thoughts, for the sake of the heart, the law is reinterpreted, and we do not fulfill it under various pretexts. So, under the pretext of maintaining health, they are removed from fasting and abstinence, and under the pretext of material need or maintaining family well-being, they refuse to do good work; defending honor, allow revenge, and so on.

It turns out this is how. We willingly believe what we love, what we like, and we strongly desire that the truth be on the side of the beloved, on the side of our selfish inclinations. Therefore, if in ourselves we hear the voice of conscience with a commandment contrary to our inclination, then already at the very beginning it has less conviction for us than the demand of the heart. Reflection, doubt, bewilderment is born in the soul as to the true meaning of the commandment: whether it generally fits the given case and my position, and so on. The fulfillment of the demand of the voice of conscience is postponed, and then, under the influence of thoughts, for the sake of the heart, the law is reinterpreted, and we do not fulfill it under various pretexts. So, under the pretext of maintaining health, they are removed from fasting and abstinence, and under the pretext of material need or maintaining family well-being, they refuse to do good work; defending honor, allow revenge, and so on. nine0003

nine0003

But all this is still half the calamity of conscience.

If one and the same person continues this activity with the reinterpretation of the moral law for a long time and constantly in one direction, then the conscience is completely distorted, becomes deviant in its legislative function. In place of the true law (in conscience), a perverse rule is put: the good is called bad, and the bad is good, and the light seems to be darkness.

As a consequence, stinginess, for example, is considered thrift, and, conversely, extravagance, generosity; anger is considered a feeling of noble indignation, and indulgence - indulgence; cruelty is presented as jealousy for the truth; flattery is considered flexibility of character, cunning - prudence, pride - self-esteem, etc. If, however, a person with such notions, with such a sinful conscience, lives and circulates in a circle of people with the same kind of opinions and rules of external behavior, then what is surprising if he takes these rules as a decisive legislation of conscience and considers their satisfaction as a just thing and virtue, and life or actions not according to them will be condemned not only by the tongue, but also by a sense of conscience? nine0003

Conscience, as a witness and judge, can be weak, lulled, hardened.

Conscience, as a witness and judge, is aware of how a person treated the law prescribed by it, determines whether a person is right or wrong. The court of conscience, as they say, is incorruptible. This is what happens, but not always. Where the legislation of conscience is wrong, where there is no beginning for judgment, there one cannot expect a true judgment of conscience. In addition, a sinner man is constantly plundered of the mind, and he cannot notice his inner spiritual dispositions that accompany the commission of an act, and therefore the conscience cannot correctly judge. In order for the judgment of conscience to be true, not hypocritical, one must also have zeal for the truth, which the sinner also does not have. nine0003

This already shows how weak and weak the conscience of a sinner is. As a result of this state of hers, each person seems to himself better than he really is. With the exception of decisive cases and all sorts of sins, a person is ready to say: what have I done?

Such is conscience as a witness and judge, if passion is not mixed with it. In a person in whom sinful passions dominate, the judgment of conscience is even more distorted: as soon as it is necessary to judge one's passionate deeds, the judgment of conscience is always crooked. Such is the judgment of conscience of an ambitious man for his ambition, of a miser for his avarice, of a fornicator for his fornication, and so on. The conscience in a person under the influence of passions gradually weakens to such an extent that, having become weak, it cannot induce a person to fulfill the law of God. nine0003

In a person in whom sinful passions dominate, the judgment of conscience is even more distorted: as soon as it is necessary to judge one's passionate deeds, the judgment of conscience is always crooked. Such is the judgment of conscience of an ambitious man for his ambition, of a miser for his avarice, of a fornicator for his fornication, and so on. The conscience in a person under the influence of passions gradually weakens to such an extent that, having become weak, it cannot induce a person to fulfill the law of God. nine0003

Not a small sign of a distortion of conscience is the evasion of judgment from oneself on others. Conscience is given to us in order to judge ourselves; if she judges others, then it must be said that she has not begun to do her job. The judgment of others, and not oneself, is a sign of the unfaithfulness of the actions of conscience. In condemning others, the judgment is quick, instant, while over ourselves it is slow, delayed, but it should be the other way around. The judgment of others is inexorably strict, while the judgment of oneself is always covered by condescension, but it should be the other way around. Such a judgment almost always ends with the words I am not like other people... And while others are constantly condemned from the heart, we love to cover ourselves with justification. Self-justification is almost a common sin. To justify their actions, they present either weakness, or ignorance, or external circumstances, or temptations, bad examples, the number of participants, and how they do not justify themselves. nine0003

The judgment of others is inexorably strict, while the judgment of oneself is always covered by condescension, but it should be the other way around. Such a judgment almost always ends with the words I am not like other people... And while others are constantly condemned from the heart, we love to cover ourselves with justification. Self-justification is almost a common sin. To justify their actions, they present either weakness, or ignorance, or external circumstances, or temptations, bad examples, the number of participants, and how they do not justify themselves. nine0003

Self-justification is a transitional stage to an even worse state of conscience. A stubborn unconsciousness is formed in a person - the fruit of a great damage to conscience and, at the same time, strong egoism. The man inside says in defiance of himself: not guilty, empty, nothing! At the same time, various twists and turns, apologies regarding the judged act are used. And in the end, a person can reach a complete hardening of conscience, when he consciously and voluntarily rejects the fulfillment of the will of God. Depart from us, say people with a similar conscience, we do not want to know Your ways (Job 21:14). nine0003

Depart from us, say people with a similar conscience, we do not want to know Your ways (Job 21:14). nine0003

Conscience as a bribe-giver can be suspicious or scrupulous, lulled (biased, hypocritical, burned).

How is the rewarding action of conscience manifested? As soon as the judgment of conscience is pronounced and a person realizes in himself that he is guilty, grief, hardship, annoyance with himself, reproaches, torments or torments of conscience begin, so, on the contrary, the gratifying feelings of conscientious justification are the reward for truth.

But even from this side there are many deviations in conscience. The basis for it, on the one hand, is in the wrong operation of the legislation and the court of conscience, for why torture the innocent? On the other hand, in the state of the heart: the callous, hardened heart of the sinner is indifferent, no matter how you blame him. Because of this, the consciousness of one's guilt for the most part remains in thought, without disturbing the heart, and a person often says: "Guilty, but what is it?" - and remains a cold spectator of his sins, often considerable sins. Time and place are of great importance. So, the recent crime is still quite disturbing, but time will pass, and it turns into a mere memory; the place where the crime is committed is also very disturbing, and away from it we are calmer. nine0003

Time and place are of great importance. So, the recent crime is still quite disturbing, but time will pass, and it turns into a mere memory; the place where the crime is committed is also very disturbing, and away from it we are calmer. nine0003

Often, without our malicious participation, fearfulness (scrupulousness, petty precision) attacks the conscience, according to which, considering almost every deed a sin, it disturbs and gnaws a person for everything. The state of one who is subjected to such a judgment is painful, and therefore it is a painful, unnatural state.

But it is a completely different matter where intent enters, where we deliberately distort conscientious retribution or force it to remain silent. This is done in various ways to lull the conscience. This lulling of conscience also occurs by itself from the increased frequency of falls, for it is known that the second fall torments less, the third even less, and so less and less, and finally the conscience becomes completely dumb: do what you want . .. But out of fear that the lulled conscience somehow did not wake up again, did not begin to torment, they resort to various tricks. For example, choosing a condescending confessor for oneself, a false confession and after that a false reassurance of oneself with permission, limiting further correction to one appearance or one outward deeds of piety and excessive hope in God's mercy. In this state of sleep, a person can enjoy the world undeservedly (a hypocritical conscience), and a person can, like the hypocrites Pharisees, even recognize himself as almost righteous. Further, conscience can come to such a state when, clearly pointing out the shortcomings of others, it will not in the least disturb a person’s own peace of mind even when grave sins are committed (biased conscience). The most disastrous moral state of a person is when his conscience comes into complete slumber, or, in the words of the Apostle Paul, a burnt conscience (see: 1 Tim 4: 2). A person enters this state when he begins to convince himself that the torments of conscience are superstitious fears that have passed from inexperienced childhood, then deliberately removes himself from persons, places and even thoughts that can disturb the conscience, deliberately indulges in vain, stupefying, strong impressions.