Mental health parenting

Mental health of children and parents —a strong connection

The mental health of children is connected to their parents’ mental health. A recent studyexternal icon found that 1 in 14 children has a caregiver with poor mental health. Fathers and mothers—and other caregivers who have the role of parent—need support, which, in turn, can help them support their children’s mental health. CDC works to make sure that parents get the support they need.

A child’s mental health is supported by their parents

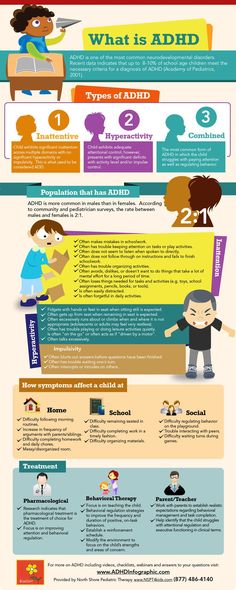

Being mentally healthy during childhood includes reaching developmental and emotional milestones and learning healthy social skills and how to cope when there are problems. Mentally healthy children are more likely to have a positive quality of life and are more likely to function well at home, in school, and in their communities.

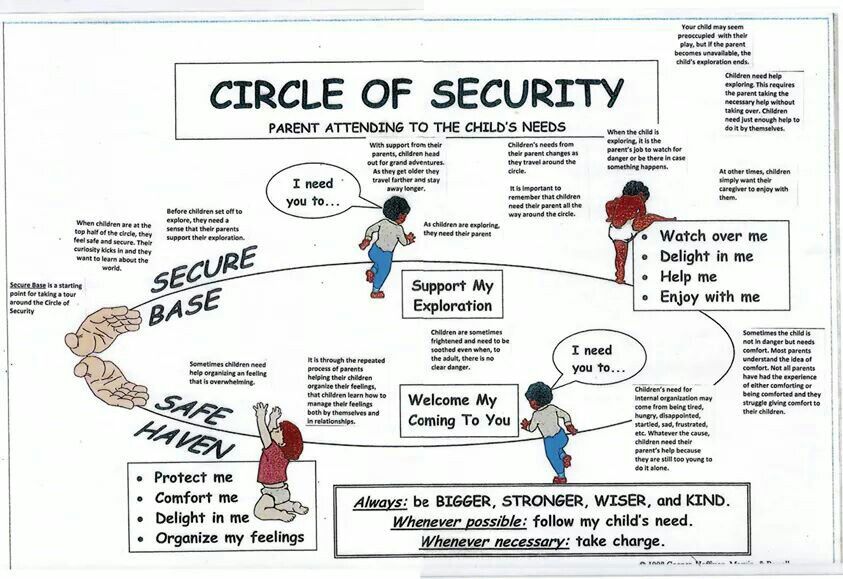

A child’s healthy development depends on their parents—and other caregivers who act in the role of parents—who serve as their first sources of support in becoming independent and leading healthy and successful lives.

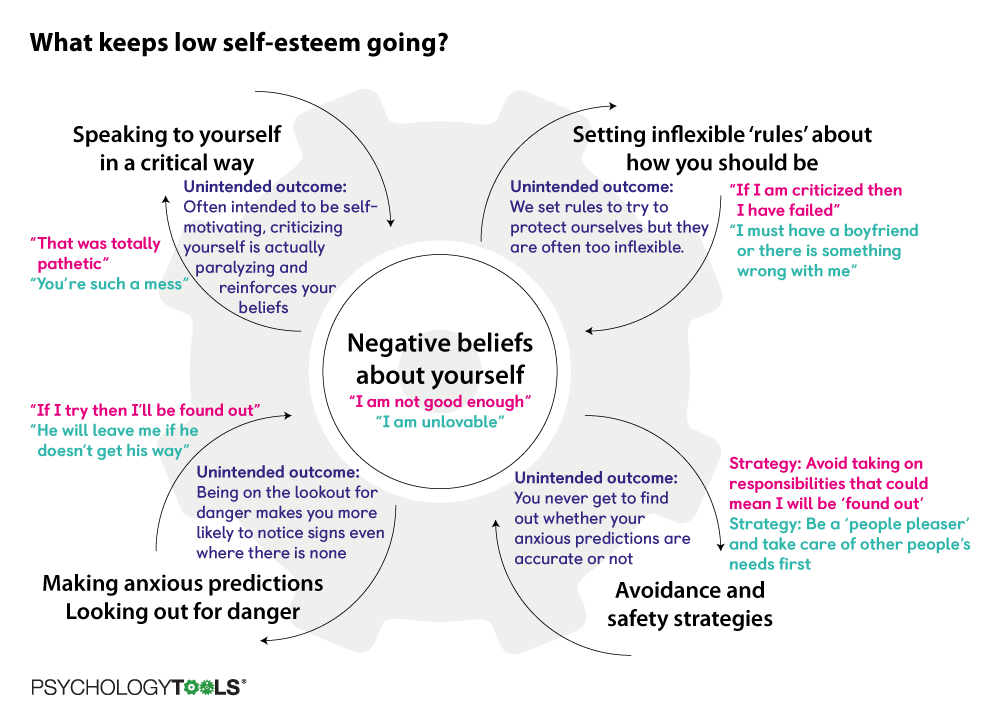

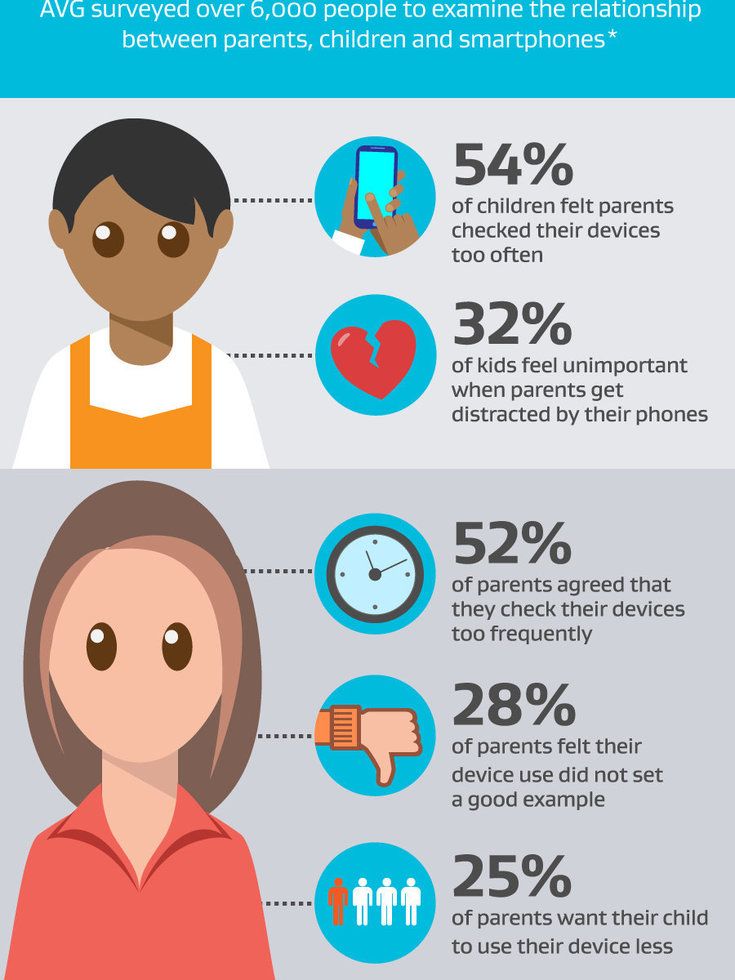

The mental health of parents and children is connected in multiple ways. Parents who have their own mental health challenges, such as coping with symptoms of depression or anxiety (fear or worry), may have more difficulty providing care for their child compared to parents who describe their mental health as good. Caring for children can create challenges for parents, particularly if they lack resources and support, which can have a negative effect on a parent’s mental health. Parents and children may also experience shared risks, such as inherited vulnerabilities, living in unsafe environments, and facing discrimination or deprivation.

Poor mental health in parents is related to poor mental and physical health in children

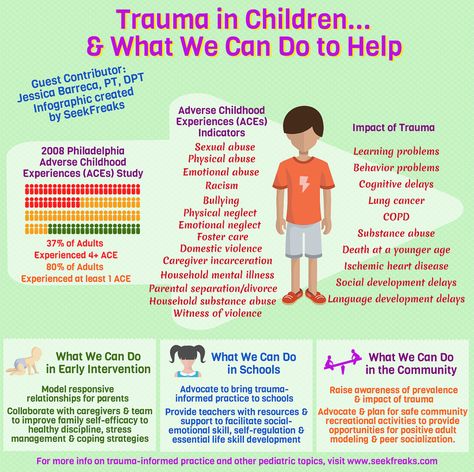

A recent study asked parents (or caregivers who had the role of parent) to report on their child’s mental and physical health as well as their own mental health. One in 14 children aged 0–17 years had a parent who reported poor mental health, and those children were more likely to have poor general health, to have a mental, emotional, or developmental disability, to have adverse childhood experiences such as exposure to violence or family disruptions including divorce, and to be living in poverty.

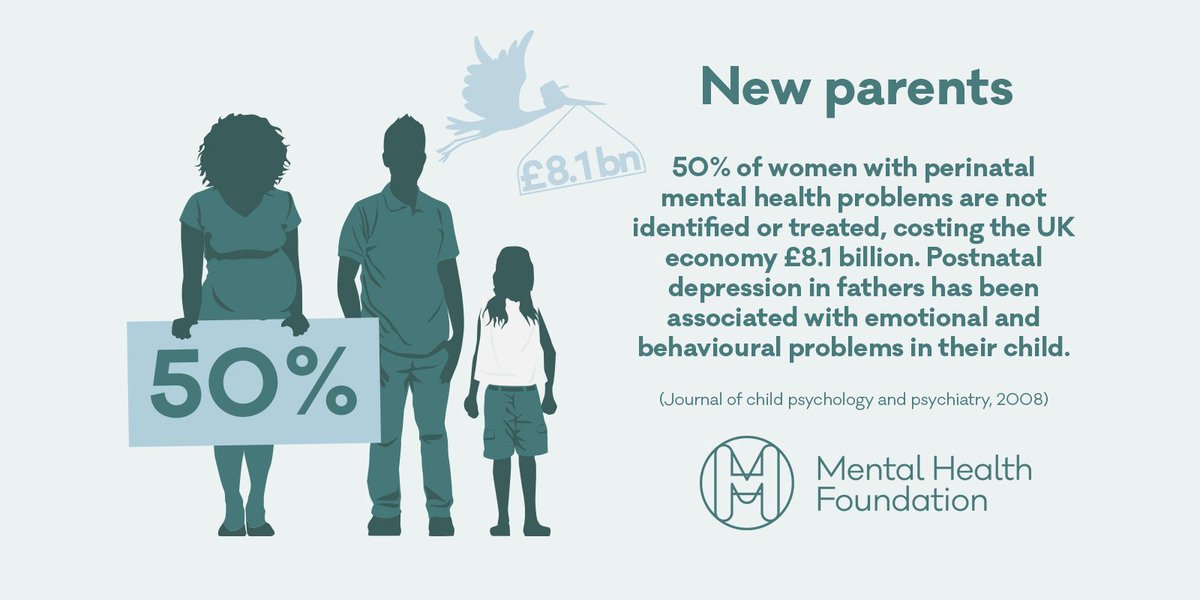

Fathers are important for children’s mental health

Fathers are important for promoting children’s mental health, although they are not as often included in research studies as mothers. The recent study looked at fathers and other male caregivers and found similar connections between their mental health and their child’s general and mental health as for mothers and other female caregivers.

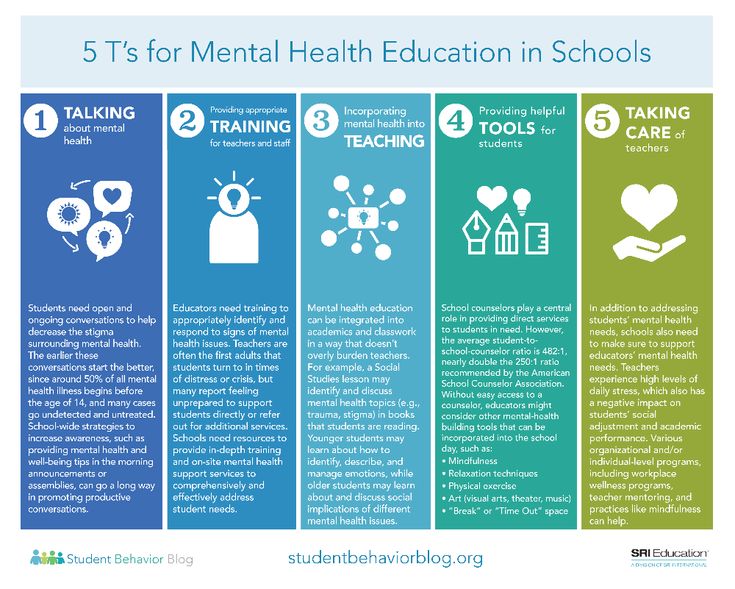

Supporting parents’ mental health

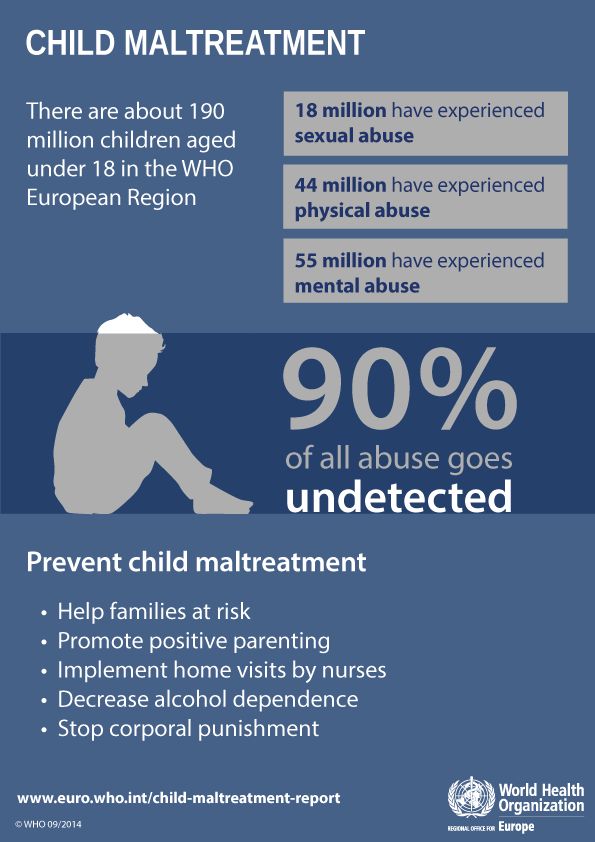

Supporting parents, and caregivers who act in the role of parent, is a critical public health priority. CDC provides parents with information about child health and development, including positive parenting tips, information and support when parents have concerns about their child’s development, or help with challenging behavior. CDC supports a variety of programs and services that address adverse childhood experiences that affect children’s and parents’ mental health, including programs to prevent child maltreatment and programs that support maternal mental health during and after pregnancy. CDC also examines issues related to health equity and social determinants of health, including racism, that affect the emotional health of parents and children. More work is needed to understand how to address risks to parents’ mental health.

CDC also examines issues related to health equity and social determinants of health, including racism, that affect the emotional health of parents and children. More work is needed to understand how to address risks to parents’ mental health.

To help parents and other adults with mental health concerns in times of distress, CDC funded the web campaign How Right Nowexternal icon as a way to find resources and support. CDC is also funding the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicineexternal icon to develop an online resource for parents to learn skills to cope with emotions and behavior using evidence-based approaches to improving mental health, which will be released this summer.

More Information

- CDC’s Children’s Mental Health

- CDC’s Child Development

- CDC’s Positive Parenting Tips

- CDC’s Information on Adolescent Mental Health

- CDC’s Information on Parenting Teens

- CDC’s Information on Depression During and After Pregnancy

- CDC’s Information on Managing Stress and Anxiety during a Pandemic

- HHS Information on Supporting Familiesexternal icon

- HHS Information on Engaging Fathersexternal icon

Reference:

Wolicki SB, Bitsko RH, Cree RA, et al. Associations of mental health among parents and other primary caregivers with child health indicators: Analysis of caregivers, by sex—National Survey of Children’s Health, 2016–2018, Adversity and Resilience Science: Journal of Research and Practice. Published online April 19, 2021 [read summaryexternal icon]

Associations of mental health among parents and other primary caregivers with child health indicators: Analysis of caregivers, by sex—National Survey of Children’s Health, 2016–2018, Adversity and Resilience Science: Journal of Research and Practice. Published online April 19, 2021 [read summaryexternal icon]

Parenting with a Mental Health Condition

Be the Best Parent You Can Be

Mental health conditions can affect any person regardless of gender, age, health status and income, and that includes people who have or want to have children of their own. Parenting is both greatly rewarding and a daunting task for anyone, but it poses some particular challenges for people with a mental health condition. Here, you will find information about parenting and mental illness, where to go to get help for you and your family, and how to support yourself and your children.

Everyone can improve on their parenting skills. Consider taking a parenting class to learn the basics and lessen the anxiety of being a parent. Parentingwell.org is a web site especially for parents with mental illness. It includes an online community, tips and tools and other resources. For perspective on all of the roles being a parent entails, visit the Parenting section of the Temple University Collaborative on Community Inclusion website.

Parentingwell.org is a web site especially for parents with mental illness. It includes an online community, tips and tools and other resources. For perspective on all of the roles being a parent entails, visit the Parenting section of the Temple University Collaborative on Community Inclusion website.

My Mental Illness and My ChildMy Child's Mental HealthTalking to My ChildCaring for ChildrenCould I Lose My Child? Legal IssuesKeeping Families Intact

What impact does a parent's mental illness have on children?

The effect of a parent's mental illness on children is varied and unpredictable.[1] Although parental mental illness poses biological, psychosocial and environmental risks for children, not all children will be negatively affected, or affected in the same way. The fact that a parent has mental illness alone is not sufficient to cause problems for the child and family. Rather, it is how the mental health condition affects the parent's behavior as well as familial relationships that may cause risk to a child. The age of onset, severity and duration of the parent's mental illness, the degree of stress in the family resulting from the illness, and most importantly, the extent to which parents' symptoms interfere with positive parenting, such as their ability to show interest in their children, will determine the level of risk to a child. The child's age and stage of development is also important.

The age of onset, severity and duration of the parent's mental illness, the degree of stress in the family resulting from the illness, and most importantly, the extent to which parents' symptoms interfere with positive parenting, such as their ability to show interest in their children, will determine the level of risk to a child. The child's age and stage of development is also important.

Will my child have a mental health condition as well?

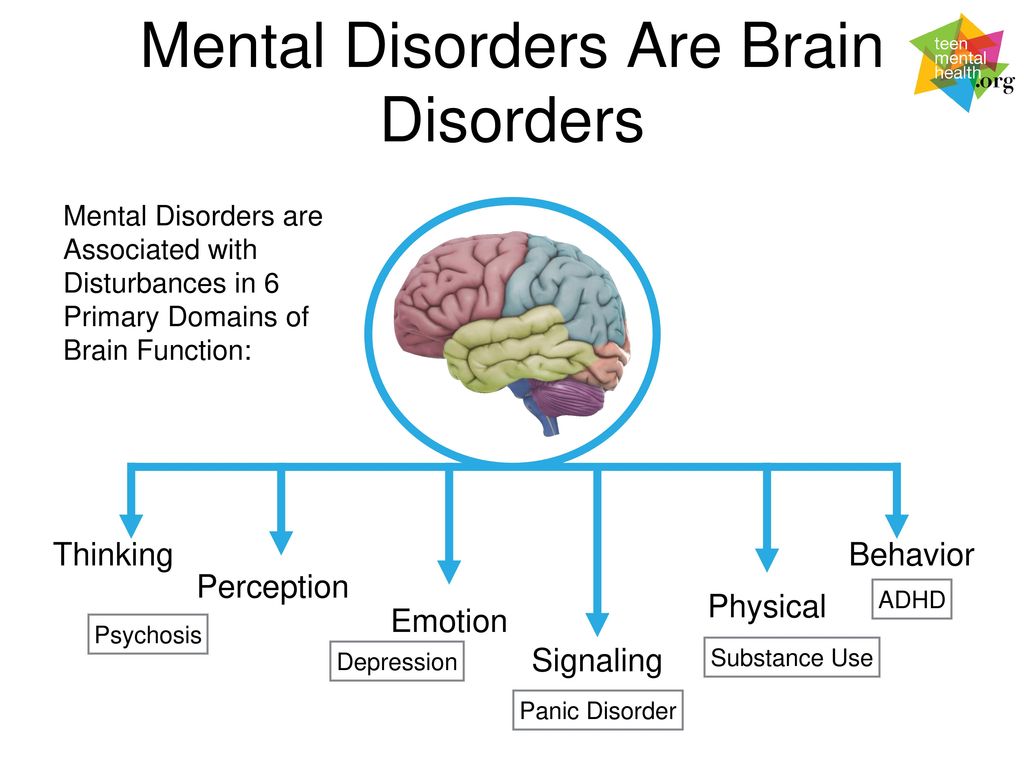

Mental health conditions are not contagious, but research shows that some mental health conditions may have a genetic link. Bipolar disorder, for example, has long been shown to run in families. Other people may pass on hereditary traits that make a mental health disorder more likely without passing on a specific disorder.

Because you have a mental health condition does not mean that your child will have a mental health condition. But because of your own experiences, it may help you be better attuned to the psychological challenges that parenting can bring.

Risk Factors

Children whose parents have a mental illness are at risk for developing social, emotional and/or behavioral problems. An inconsistent and unpredictable family environment, often found in families in which a parent has mental illness, contributes to a child's risk. Other factors that place all children at risk, but particularly increase the vulnerability of children whose parents have a mental illness, include:

- Poverty

- Occupational or marital difficulties

- Poor parent-child communication

- Parent's co-occurring substance abuse disorder

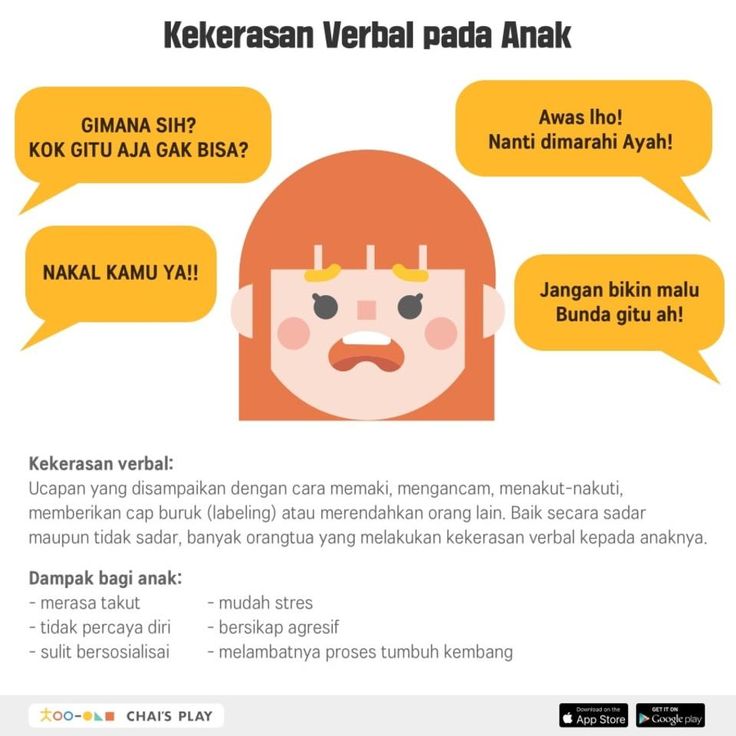

- Openly aggressive or hostile behavior by a parent

- Single-parent families

Families at greatest risk are those in which mental illness, a child with their own difficulties, and chronically stressful family environments are all present. Many of these factors, however, can be reduced through preventive interventions. For example, poor parent-child communication can be improved through skills training, and marital conflict can be reduced through couple's therapy.

The Prevention Perspective

Whether or not children of parents with mental illness will develop social, emotional, or behavioral problems depends on a number of factors. These include the child's genetic vulnerability, the parent's behavior, the child's understanding of the parent's illness, and the degree of family stability (for example, the number of parent-child separations). Preventive interventions aimed at addressing risk factors and increasing children's protective factors increase the likelihood that they will be resilient, and grow and develop in positive ways. Effective prevention strategies help increase family stability, strengthen parents' ability to meet their children's needs, and minimize children's exposure to negative manifestations of their parent's illness.[2]

Protective Factors

Increasing a child's protective factors helps develop his or her resiliency. Resilient children understand that they are not responsible for their parent's difficulties, and are able to move forward in the face of life's challenges. It is always important to consider the age and stage of development when supporting children. Protective factors for children include:

It is always important to consider the age and stage of development when supporting children. Protective factors for children include:

- A parent's warm and supportive relationship with his or her children

- Help and support from immediate and extended family members

- A sense of being loved by their parent

- Positive self-esteem

- Good coping skills

- Positive peer relationships

- Interest in and success at school

- Healthy engagement with adults outside the home

- An ability to articulate their feelings

- Parents who are functioning well at home, at work, and in their social relationships

- Parental employment

References:

1. Joanne Nicholson, Elaine Sweeny, and Jeffrey Geller. Mothers With Mental Illness: I. The Competing Demands of Parenting and Living With Mental Illness. Psychiatric Services. May 1998. Vol. 49. No. 5.

2. Ibid.

How do I talk to my child about my mental health condition?

How you talk to your child about your mental health condition will depend on the age and maturity of your child and your willingness to open up to him or her.

In general, children, especially as they grow older, are very astute and knowledgeable about their surroundings. They can sense emotional changes and can often tell if something is hidden from them without their knowledge. Some children may be able to fully understand what it means to have a mental health condition. In talking with children you can help them to know how to cope when you are not feeling well. And, a child may be able to support you in your recovery by reminding you when to take your medications or help you stay on track.

Your decision to talk to your child about your condition should also take into account your readiness. Parents often want to appear invincible and strong to their children, as they think it is the parents' role to care for a sick child and not the other way around. The decisions you make should be made with both parent and child in mind.

Before proceeding, you should always talk to your doctor or therapist about the best ways to bring this information up. You may want to consider the possibility of inviting a child to a session to explore this information.

You may want to consider the possibility of inviting a child to a session to explore this information.

What can I expect from my child?

Your child might experience some of these feelings:

- Anger - Your child may be angry at you for having a mental health condition. The child may think that it was your fault that you had a mental health condition and that it is your fault that they will experience a harder life. Your child might also be angry at external forces, such as a higher power or the world, for unfairly hurting you or your family. Your child may also be angry at him or herself. If you notice anger problems in your child, you should talk to your therapist or doctor about arranging for your child to join in sessions.

- Fear - Your child might be scared about what the future will bring. Your child might be afraid about how your mental health condition will change your relationship. They might be afraid about your ability to take care of them.

Your child may also be scared about what others will think if they found out that you have a mental health condition. Sit down and talk to your child about these issues, reassure them you still love them.

Your child may also be scared about what others will think if they found out that you have a mental health condition. Sit down and talk to your child about these issues, reassure them you still love them. - Guilt - Your child may blame himself or herself for your mental health condition, especially in cases or anxiety or depression. Your child may express guilt by taking over an inordinate amount of household duties. Your child may try and hide his or her own problems so as not to make your life any worse.

- Shame - Despite efforts to educate the public about mental illness, mental illness is still often a stigmatized and misunderstood condition. Your child might be embarrassed. He or she might think that your condition will have negative impacts on his or her social life and might be worried.

- Sadness - Children can become very sad when they learn that a loved one, especially a parent, is hurt or sick. You should talk to your doctor about ways to cope with sadness and ways to know when sadness becomes depression.

- Anxiety - Your child may become overanxious or worried about you if he or she learns that you have a mental health condition. These children tend to be overly helpful and may miss out on their own lives.

- Relief - For some children, learning that you have a mental health condition might be a relief. It might help explain behaviors or incidents that they experienced that they previously could not understand.

- Supportiveness - Your child may be very supportive of your mental health, regardless of his or her previous attitudes toward mental illness. Often, having mental illness in a family can change someone's orientation toward mental illness.

How can I care for a child while caring for myself?

In addition to being a parent, you are also a person of your own. Your recovery plans and activities should always include time for yourself that is relaxing and beneficial.

If you have a crisis action plan or a psychiatric advance directive, you should designate someone to help with your parenting duties. If your child is old enough, you should discuss your plan with your child and identify resources and options together for handling things when you are not well.

If your child is old enough, you should discuss your plan with your child and identify resources and options together for handling things when you are not well.

Could I lose my child because I have a mental health condition?

A higher proportion of parents with serious mental illness lose custody of their children than parents without mental illness. There are many reasons why parents with a mental illness risk losing custody, including the stresses their families undergo, the impact on their ability to parent, economic hardship, and the attitudes of mental health providers, social workers and the child protective system. Supporting a family where mental illness is present takes extra resources that may not be available or may not be offered. Also, a few state laws cite mental illness as a condition that can lead to loss of custody or parental rights. One unfortunate result is that parents with mental illness might avoid seeking mental health services for fear of losing custody of their children. Studies that have investigated this issue report that:

Studies that have investigated this issue report that:

- Only one-third of children with a parent who has a serious mental illness are being raised by that parent.

- In New York, 16 percent of the families involved in the foster care system and 21 percent of those receiving family preservation services include a parent with a mental illness.

- Grandparents and other relatives are the most frequent caregivers if a parent is psychiatrically hospitalized, however other possible placements include voluntary or involuntary placement in foster care.[1]

The major reason states take away custody from parents with mental illness is the severity of the illness, and the absence of other competent adults in the home.[2] Although mental disability alone is insufficient to establish parental unfitness, some symptoms of mental illness, such as disorientation and adverse side effects from psychiatric medications, may demonstrate parental unfitness. A research study found that nearly 25 percent of caseworkers had filed reports of suspected child abuse or neglect concerning their clients. [3]

[3]

The loss of custody can be traumatic for a parent and can exacerbate their illness, making it more difficult for them to regain custody. If mental illness prevents a parent from protecting their child from harmful situations, the likelihood of losing custody is drastically increased.

Legal Issues

All people have the right to bear and raise children without government interference. However, this is not a guaranteed right. Governments may intervene in family life in order to protect children from abuse or neglect, imminent danger or perceived imminent danger. When parents are not able, either alone or with support, to provide the necessary care and protection for their child, the state may remove the child from the home and provide substitute care.

Adoption and Safe Families Act

The Federal Adoption and Safe Families Act, Public Law 105-89 (ASFA) was signed into law November 19, 1997. This legislation is the first substantive change in federal child welfare law since the Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act of 1980, Public Law 96-272. 4 It is intended to achieve a balance of safety, well-being and permanency for children in foster care. It requires that state child welfare agencies make "reasonable efforts" to prevent the unnecessary placement of children in foster care and to provide services necessary to reunify children in foster care with their families. ASFA establishes expedited timelines for determining whether children who enter foster care can be moved into permanent homes promptly-their own familial home, a relative's home, adoptive home, or other planned permanent living arrangement.

4 It is intended to achieve a balance of safety, well-being and permanency for children in foster care. It requires that state child welfare agencies make "reasonable efforts" to prevent the unnecessary placement of children in foster care and to provide services necessary to reunify children in foster care with their families. ASFA establishes expedited timelines for determining whether children who enter foster care can be moved into permanent homes promptly-their own familial home, a relative's home, adoptive home, or other planned permanent living arrangement.

While ASFA is designed to protect children, it also includes provisions pertaining to parental rights. For example, under ASFA, parents have the right to receive supports and services to help them retain custody and keep their families intact. The child welfare system must provide these services according to an individualized plan that has been developed and agreed upon by all parties to ensure parents with mental illnesses are not discriminated against due to their illness. A plan with parental input also helps ensure that, when appropriate, efforts are made by state welfare agencies to promote family permanency, including establishing whether children in foster care can be moved into a permanent living situation.

A plan with parental input also helps ensure that, when appropriate, efforts are made by state welfare agencies to promote family permanency, including establishing whether children in foster care can be moved into a permanent living situation.

Helping Families Stay Intact

Parental mental illness alone can cause strain on a family; parental mental illness combined with parental custody fears can cause even greater strain. Such strain, as well as the lack of specialized services for families in the child welfare system and the overall stigma associated with mental illness, makes it difficult for families to get the help they need. With the right services and supports though, many families can stay together and thrive. The following efforts by advocates can help families living with mental illness maintain custody and stay intact:

- Help parents become educated about their rights and obtain legal assistance and information.

- Advocate for parents as services plans are developed, and assist adult consumers to develop their own self-care plans and advance directives to strengthen their parenting skills and manage their own illness.

- Enable parent-child visitation during psychiatric hospitalization to maintain the bond between parent and child.

- Train child protective services workers to better understand parental mental illness.

- Educate the legal system about advances in the treatment of serious mental illness.

- Advocate for increased specialized services for parents with serious mental illnesses available through the court system.

References:

1. Network practical tools for changing environment. Making the Invisible Visible: Parents with Psychiatric Disabilities. National Technical Assistance Center for State Mental Health Planning. Special Issue Parents with Psychiatric Disabilities. Spring, 2000.

2. Roberta Sands. "The Parenting Experience of Low-Income Single Women with Serious Mental Disorders. Families in Society." The Journal of Contemporary Human Services. 76 (2), 86-89. 1995.

3. Joanne Nicholson, Elaine Sweeny, and Jeffrey Geller. Mothers With Mental Illness: II. Family Relationships and the Context of Parenting. May 1998. Vol. 49. No. 5.

Family Relationships and the Context of Parenting. May 1998. Vol. 49. No. 5.

4. Ibid.

Mental health of parents raising a child with special needs

The difficulties that a family with a problem child constantly experiences are significantly different from the daily worries that a family raising a normally developing child lives with. An analysis of the literature on family issues makes it possible to single out the main functions most often attributed to an ordinary family . Among them:

· bearing and raising children;

communication between generations, preservation and transmission of family values and traditions to children; nine0009 satisfaction of the need for psychological comfort and emotional support, warmth and love;

Creation of conditions for the development of the personality of all family members;

Satisfaction of sexual and erotic needs;

Satisfying the need to communicate with loved ones;

Satisfaction of individual needs in fatherhood or motherhood, in contacts with children, their upbringing, self-realization in children;

Health protection of family members, organization of recreation, stress relief. nine0007

nine0007

Almost all functions, with a few exceptions, are not implemented or not fully implemented in families raising children with developmental disabilities. This may be due to the following reasons.

As a result of the birth of a child with special features , the development of relationships within the family, as well as contacts with the surrounding society, is distorted . The causes of violations are associated with the psychological characteristics of the child, as well as with the enormous emotional burden that members of his family bear due to long-term stress. Many parents find themselves helpless in this situation. Their position can be described as0003 internal (psychological) and external (social) impasse.

Qualitative changes in such families are manifested at the following levels: psychological, social and somatic.

Psychological level

The birth of a child with developmental disabilities is perceived by his parents as the greatest tragedy. The fact of the birth of a child “not like everyone else” is the cause of severe stress experienced by parents, especially the mother. Stress becomes the initial condition for a sharp traumatic change in the way of life that has formed in the family. Deformed: nine0007

The fact of the birth of a child “not like everyone else” is the cause of severe stress experienced by parents, especially the mother. Stress becomes the initial condition for a sharp traumatic change in the way of life that has formed in the family. Deformed: nine0007

- established style of intra-family relationships;

- system of relations of family members with the surrounding society;

- features of the worldview and value orientations of each of the parents of a sick child.

All the hopes and expectations of family members in connection with the future of the child turn out to be futile and collapse in an instant, and understanding what happened and acquiring new life values sometimes stretches for a long period. This can be due to many reasons, including: nine0007

- psychological characteristics of the parents themselves, their ability to accept or not accept a sick child;

- the presence of a complex of disorders that characterize one or another developmental anomaly, the degree of their severity;

- the absence of a positively supportive influence of society in contacts with a family raising an abnormal child.

The distribution of responsibilities between husband and wife, father and mother in most Russian families is traditional. Problems related to the internal state and ensuring the life of the family (economic, domestic), as well as the upbringing and education of children, including developmental features, mainly fall on the woman. A man - the father of a sick child - provides, first of all, the economic base of the family. He does not leave or change the profile of his work because of the birth of a sick child and, thus, is not excluded, like the mother of a child, from familiar social relations. His life stereotype, according to our observations, does not change so much, since he spends most of his time in the same social environment (at work, with friends, etc.). The father of a special child spends less time with him than the mother due to being busy at work and in accordance with the traditional understanding of this family responsibility. Therefore, his psyche is not exposed to pathogenic influence as intensively as the psyche of the mother of a sick child. The characteristics listed are usually the most common. But, of course, there are exceptions to the rule. nine0007

The characteristics listed are usually the most common. But, of course, there are exceptions to the rule. nine0007

The emotional impact of stress on a woman who has given birth to a special child is immeasurably greater. Mothers often experience tantrums and depression. The fears that overcome women about the unborn child give rise to a feeling of loneliness, loss and a feeling of "the end of life." Mothers are with their children all the time. Often, such mothers are characterized by a decrease in mental tone, low self-esteem, which manifests itself in the loss of a taste for life, prospects for a professional career, and the impossibility of realizing their own creative plans. nine0007

Due to the fact that the birth of the child's characteristics, and then his upbringing, education and, in general, communication with him are a long-term pathogenic psychological factor, the mother's personality can undergo significant changes (V.A. Vishnevsky, 1987). Depressive experiences can transform into neurotic development of the personality and significantly disrupt its social adaptation.

Social level

After the birth of a child with developmental problems, his family, due to the numerous difficulties that arise, becomes uncommunicative and selective in contacts. It narrows the circle of acquaintances and even relatives due to the characteristic features of the state and development of the child, and also because of the personal attitudes of the parents themselves (fear, shame). nine0007

The birth of a child with developmental problems also has a deforming effect on the relationship between the parents of a sick child. One of the saddest manifestations that characterize the state of the family is divorce. The child is not always called the external cause of divorce (parents refer to the spoiled character of the spouse (or spouse), lack of mutual understanding in the family, frequent quarrels and, as a result, cooling of feelings). Nevertheless, the objective stressor that frustrates the psyche of family members is the very fact of the birth of a special child and the state of his health in the subsequent period. The current new situation becomes a test to verify the authenticity of feelings both between spouses and between each parent and a sick child. There are cases when such difficulties united the family. However, some families do not withstand such a test and break up, which has a negative impact on the process of forming the personality of a child with developmental disabilities. For this reason, some families refuse to have other children. nine0007

The current new situation becomes a test to verify the authenticity of feelings both between spouses and between each parent and a sick child. There are cases when such difficulties united the family. However, some families do not withstand such a test and break up, which has a negative impact on the process of forming the personality of a child with developmental disabilities. For this reason, some families refuse to have other children. nine0007

There are families in which one or two more healthy children are brought up. In most of them, a child with developmental disabilities is the last to be born. Nevertheless, in such families there are more favorable opportunities for normalizing the psychological state of parents compared to the objective possibilities of parents raising an only child with special needs.

Family relationships can worsen not only between spouses. They may vary between the mother and her parents or her husband's parents. The characteristics of a child are difficult to accept for an unprepared person. Pity for your grandson and his mother can permeate the relationship of loved ones for a long time. nine0007

Pity for your grandson and his mother can permeate the relationship of loved ones for a long time. nine0007

The educational level of the parents is different. The opinion still prevailing in society that “sick” children are born only in families with a low social and cultural level turns out to be incorrect. Many parents have high and very high social status.

However, some mothers, due to the prevailing circumstances, after the birth of a child with developmental disabilities, are forced to change the profile of their work or leave it altogether. The departure of a woman from her favorite job not only deprives her of earnings, but also changes her social status, puts her in a dependent position from her husband, from her family. Some mothers find the strength and opportunity to receive special education and use new knowledge to develop and educate both their child and other children. nine0007

Some parents take a dependent or non-initiative position. Parents believe that specialists and employees of institutions in which their children are brought up, educated or treated and live for a long time should deal with the problems of their child.

Somatic level

Stress that has arisen as a result of a complex of irreversible mental disorders in a child can cause various diseases in his mother, being, as it were, a trigger for this process. A pathological chain arises: the child’s illness causes psychogenic stress in his mother, which, to one degree or another, provokes the occurrence of somatic or mental illness in her. Thus, a child’s illness, his mental state can be psychogenic for parents, especially mothers. nine0007

According to the literature data, somatic diseases in parents of children with developmental disabilities have the following features. Mothers complain of fluctuations in blood pressure, insomnia, frequent and severe headaches, violations of thermoregulation. The older the child becomes, i.e. the longer the psychopathogenic situation, the more some of the mothers show health problems. There are: disorders of the menstrual cycle and early menopause; frequent colds and allergies; cardiovascular and endocrine diseases; pronounced or total graying; problems associated with the gastrointestinal tract. Mothers often complain of general fatigue, lack of strength, and also note a state of general depression and melancholy. nine0007

Mothers often complain of general fatigue, lack of strength, and also note a state of general depression and melancholy. nine0007

The presence of a huge physical load, which undoubtedly depletes strength and affects the somatic state of the parents, the psychological factor and the unmeasurable severity of the experience play a primary role. As you know, "pathogenic is that experience that occupies a significant place in the system of the relationship of the individual to reality." For parents of special children, psychological features of the development of their children are primarily pathogenic. Feelings of fear, self-doubt, various forms of depression - all these painful states of parents are not only a response of their personality to a traumatic experience, but also a defensive response of their entire body. nine0007

Particularly significant is the impact on individual mothers of repeated psychotraumas that are no longer directly related to the state of health and developmental features of their child. Such injuries can include both fairly mild ones - conflicts in transport or in a store, a conflict with superiors, dismissal from work, a quarrel with relatives, fear of expulsion of a child from an educational institution due to poor progress, and more severe ones - a husband leaving for another family, divorce, death of a loved one. A new traumatic situation is assessed by such parents as more severe, prolonged and profound. They seem to take blow after blow from life, and each new stress that traumatizes their psyche overthrows them lower and lower. nine0007

Such injuries can include both fairly mild ones - conflicts in transport or in a store, a conflict with superiors, dismissal from work, a quarrel with relatives, fear of expulsion of a child from an educational institution due to poor progress, and more severe ones - a husband leaving for another family, divorce, death of a loved one. A new traumatic situation is assessed by such parents as more severe, prolonged and profound. They seem to take blow after blow from life, and each new stress that traumatizes their psyche overthrows them lower and lower. nine0007

It turns out that the systems of experiences that have ceased to sound under certain conditions can have an influence on the experiences of a given moment. The most important of these conditions are the degree of completeness of the disconnected system of experiences and its emotional significance. As children grow older, the experiences of their mothers may only be somewhat smoothed out, and even then not always, but this does not mean at all that the experience ends and is disconnected from the present.

Mental health of children - in the hands of parents -

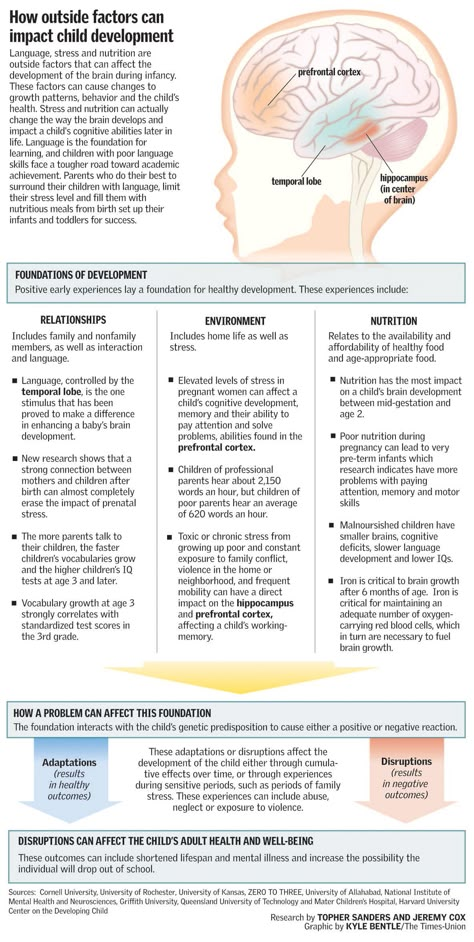

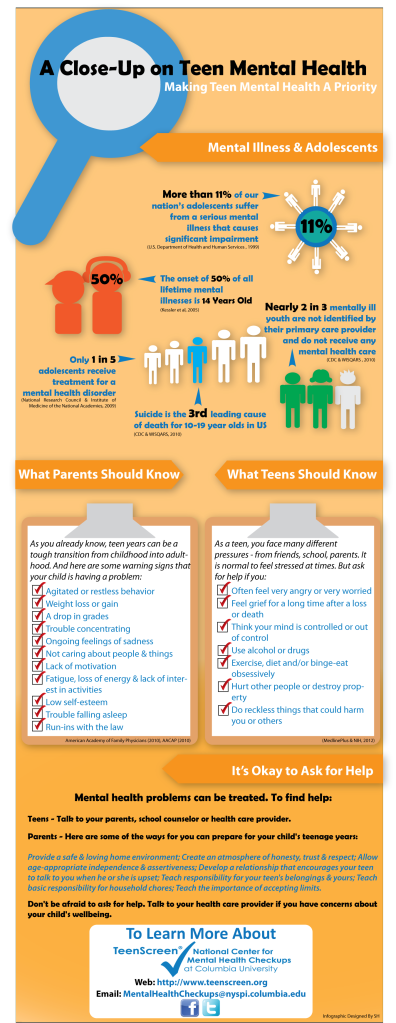

From the first years of a child's life, parents need to take care of their child's mental health. In a normal family, the baby is surrounded by the attention and care of relatives, and, it would seem, there should be no cause for concern. However, even in children brought up in a family, a very high percentage of mental illnesses, including neuroses, is observed, especially in older preschool and younger school age.

The atmosphere in the family and, consequently, the mental health of the child is influenced by various factors. The negative impact is exerted by excessive workload of parents, their neuroticism, the presence of personal problems and ignorance of how to solve them. Unsatisfactory living conditions and the mother's early departure for work also contribute. Placing a child in a kindergarten until the age of three or attracting a nanny severely traumatizes his psyche, since he is not yet ready to be separated from his mother. nine0007

nine0007

Bad influence on the child and conflicts between parents. At this age, the baby cannot yet navigate the intricacies of interpersonal communication well, is unable to understand the causes of conflicts between parents, and cannot express his own feelings and experiences. Very often, quarrels between parents are perceived by him as an alarming event, a situation of danger. The child tends to feel guilty about the conflict that has arisen, the misfortune that has happened, because he cannot understand the true reasons for what is happening and explains everything by the fact that he is bad, does not justify the hopes of his parents and is not worthy of love. All this causes in preschoolers a constant feeling of anxiety, self-doubt, emotional stress and can become a source of mental illness. nine0007

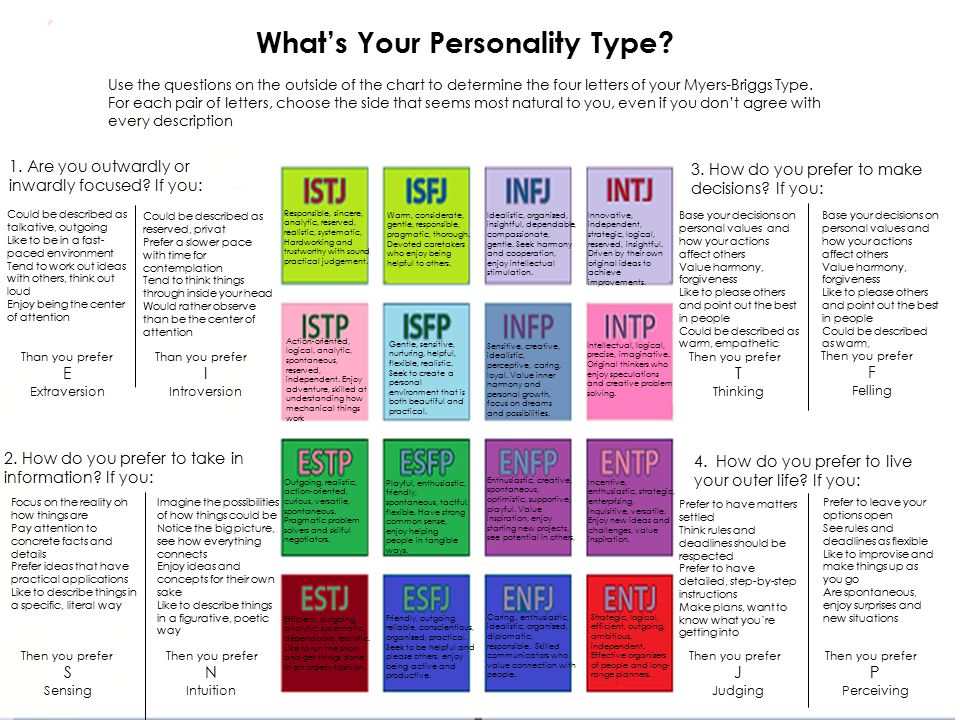

Upbringing and relationships with parents also play a role in the development of a child. Experts distinguish democratic, controlling and mixed styles of parenting. The democratic style is characterized by a high level of acceptance of the child, well-developed verbal communication with children, faith in the independence of the child, combined with a willingness to help him if necessary. As a result of such upbringing, children are distinguished by the ability to communicate with peers, activity, the desire to control other children (and they themselves cannot be controlled), and good physical development. With a controlling style of parenting, parents take on the function of controlling the behavior of children: they limit their activities, but explain the essence of the prohibitions. Children are obedient, non-aggressive, indecisive. With a mixed style of upbringing, children are most often characterized as obedient, emotionally sensitive, suggestible, incurious, with poor imagination. Wrong education leads to the formation of various neuroses. For example, scientists distinguish three types of improper parenting:

As a result of such upbringing, children are distinguished by the ability to communicate with peers, activity, the desire to control other children (and they themselves cannot be controlled), and good physical development. With a controlling style of parenting, parents take on the function of controlling the behavior of children: they limit their activities, but explain the essence of the prohibitions. Children are obedient, non-aggressive, indecisive. With a mixed style of upbringing, children are most often characterized as obedient, emotionally sensitive, suggestible, incurious, with poor imagination. Wrong education leads to the formation of various neuroses. For example, scientists distinguish three types of improper parenting:

1. Non-acceptance, emotional rejection of the child (consciously or unconsciously), the presence of strict regulatory and control measures, the imposition of a certain type of behavior on the child in accordance with parental concepts of “good children”. The other pole of rejection is characterized by complete indifference, connivance and lack of control on the part of parents.

The other pole of rejection is characterized by complete indifference, connivance and lack of control on the part of parents.

2. Hyper-socializing upbringing - anxious and suspicious attitude of parents to health, educational success of their child, his status among peers, as well as excessive concern for his future. 3. Egocentric excessive attention to the child of all family members, assigning him the role of "family idol". nine0007

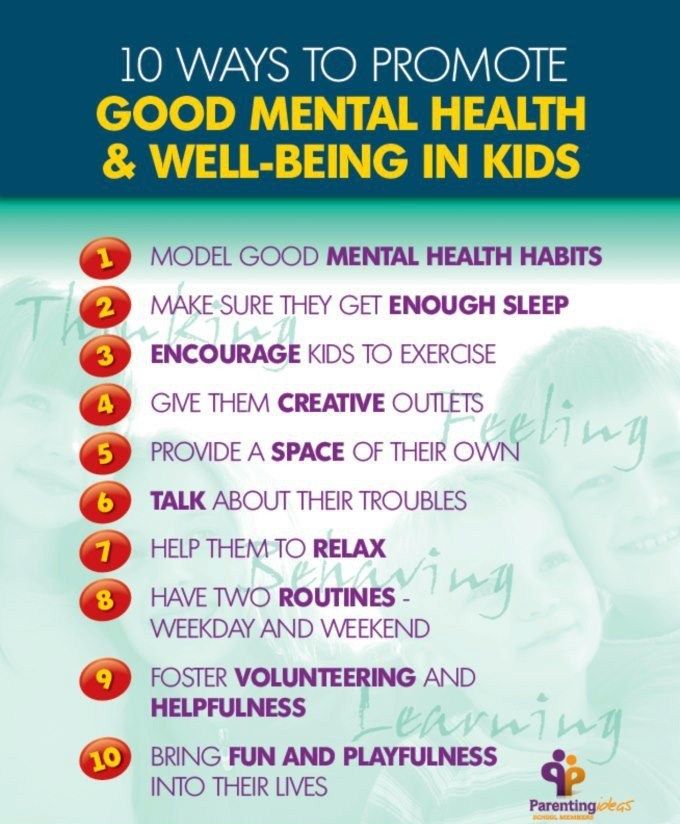

Of course, there are no ready-made recipes and models of upbringing that you can simply take and, without changing, apply to your child. But we can give some recommendations:

1. Believe in the uniqueness of your child, he is not like you, so do not demand from the child to implement the life program you set and achieve the goals you set, give him the right to live life himself.

2. Let the child be himself, with his faults, weaknesses and strengths. Accept him as he is. Build on your child's strengths. nine0007

3. Do not hesitate to show your love to your child, let him know that you will love him always, under any circumstances.

Do not hesitate to show your love to your child, let him know that you will love him always, under any circumstances.

4. Don't be afraid to "love" the child, take him on your knees, look into his eyes, hug and kiss him when he wants to.

5. As an educational influence, use affection and encouragement more often than punishment and censure.

6. Try not to let your love turn into permissiveness and neglect. Set clear limits and prohibitions (it is desirable that there are not many of them, the most basic, in your opinion) and allow the child to act within the established prohibitions and permissions. nine0007

7. Do not rush to resort to punishment. Try to influence the child with requests - this is the most effective way to give him instructions. In case of disobedience to the parent, it is necessary to make sure that the request corresponds to the age and capabilities of the child.

8. Do not forget that the key to a child's heart lies through play. During the game, you will be able to transfer to him the necessary skills and knowledge, concepts of life rules and values.