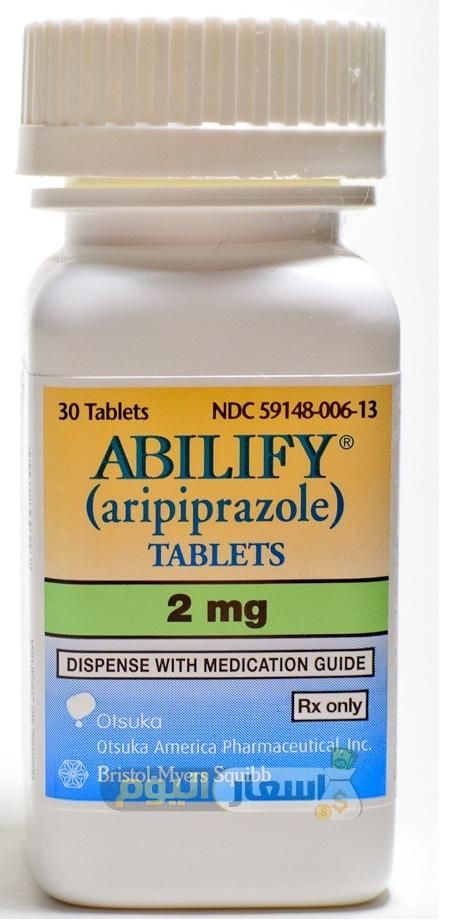

Max dosage of abilify

Initiation and Dosing | ABILIFY MAINTENA® (aripiprazole)

ISI Block Title

WARNING: INCREASED MORTALITY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS WITH DEMENTIA-RELATED PSYCHOSIS

Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at increased risk of death (1.6 to 1.7 times) compared to placebo-treated patients. ABILIFY MAINTENA is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis.

Contraindication: Known hypersensitivity reaction to aripiprazole. Reactions have ranged from pruritus/urticaria to anaphylaxis.

Cerebrovascular Adverse Events, Including Stroke: Increased incidence of cerebrovascular adverse events (e.g., stroke, transient ischemic attack), including fatalities, have been reported in clinical trials of elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with oral aripiprazole.

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS): NMS is a potentially fatal symptom complex reported in association with administration of antipsychotic drugs including ABILIFY MAINTENA. Clinical signs of NMS are hyperpyrexia, muscle rigidity, altered mental status and evidence of autonomic instability. Additional signs may include elevated creatine phosphokinase, myoglobinuria (rhabdomyolysis), and acute renal failure. Manage NMS with immediate discontinuation of ABILIFY MAINTENA, intensive symptomatic treatment, and monitoring.

Tardive Dyskinesia (TD): Risk of TD, and the potential to become irreversible, are believed to increase with duration of treatment and total cumulative dose of antipsychotic drugs. TD can develop after a relatively brief treatment period, even at low doses, or after discontinuation of treatment. Prescribing should be consistent with the need to minimize TD. If antipsychotic treatment is withdrawn, TD may remit, partially or completely.

Metabolic Changes: Atypical antipsychotic drugs have caused metabolic changes including:

- Hyperglycemia/Diabetes Mellitus: Hyperglycemia, in some cases extreme and associated with ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar coma, or death, has been reported in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics including aripiprazole.

Patients with diabetes mellitus should be regularly monitored for worsening of glucose control; those with risk factors for diabetes (e.g., obesity, family history of diabetes), should undergo baseline and periodic fasting blood glucose testing. Any patient treated with atypical antipsychotics should be monitored for symptoms of hyperglycemia including polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, and weakness. Patients who develop symptoms of hyperglycemia should also undergo fasting blood glucose testing. In some cases, hyperglycemia has resolved when the atypical antipsychotic was discontinued; however, some patients required continuation of anti-diabetic treatment despite discontinuation of the suspect drug.

Patients with diabetes mellitus should be regularly monitored for worsening of glucose control; those with risk factors for diabetes (e.g., obesity, family history of diabetes), should undergo baseline and periodic fasting blood glucose testing. Any patient treated with atypical antipsychotics should be monitored for symptoms of hyperglycemia including polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, and weakness. Patients who develop symptoms of hyperglycemia should also undergo fasting blood glucose testing. In some cases, hyperglycemia has resolved when the atypical antipsychotic was discontinued; however, some patients required continuation of anti-diabetic treatment despite discontinuation of the suspect drug. - Dyslipidemia: Undesirable alterations in lipids have been observed in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics.

- Weight Gain: Weight gain has been observed with atypical antipsychotic use. Clinical monitoring of weight is recommended.

Pathological Gambling and Other Compulsive Behaviors: Intense urges, particularly for gambling, and the inability to control these urges have been reported while taking aripiprazole. Other compulsive urges have been reported less frequently. Prescribers should ask patients or their caregivers about the development of new or intense compulsive urges. Consider dose reduction or stopping aripiprazole if such urges develop.

Orthostatic Hypotension: ABILIFY MAINTENA may cause orthostatic hypotension and should be used with caution in patients with known cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, or conditions which would predispose them to hypotension.

Falls: Antipsychotics may cause somnolence, postural hypotension, motor and sensory instability, which may lead to falls causing fractures or other injuries. For patients with diseases, conditions, or medications that could exacerbate these effects, complete fall risk assessments when initiating treatment and recurrently during therapy.

Leukopenia, Neutropenia, and Agranulocytosis: Leukopenia, neutropenia and agranulocytosis have been reported with antipsychotics. Monitor complete blood count in patients with pre-existing low white blood cell count (WBC)/absolute neutrophil count or history of drug-induced leukopenia/neutropenia. Discontinue ABILIFY MAINTENA at the first sign of a clinically significant decline in WBC and in severely neutropenic patients.

Seizures: ABILIFY MAINTENA should be used with caution in patients with a history of seizures or with conditions that lower the seizure threshold.

Potential for Cognitive and Motor Impairment: ABILIFY MAINTENA may impair judgment, thinking, or motor skills. Instruct patients to avoid operating hazardous machinery, including automobiles, until they are certain ABILIFY MAINTENA does not affect them adversely.

Body Temperature Regulation: Use ABILIFY MAINTENA with caution in patients who may experience conditions that increase body temperature (e. g., strenuous exercise, extreme heat, dehydration, or concomitant use with anticholinergics).

g., strenuous exercise, extreme heat, dehydration, or concomitant use with anticholinergics).

Dysphagia: Esophageal dysmotility and aspiration have been associated with ABILIFY MAINTENA. Use caution in patients at risk for aspiration pneumonia.

Alcohol: Advise patients to avoid alcohol while taking ABILIFY MAINTENA.

Concomitant Medication: Dosage adjustments are recommended in patients who are CYP2D6 poor metabolizers and in patients taking concomitant CYP3A4 inhibitors or CYP2D6 inhibitors for greater than 14 days. Avoid concomitant use of CYP3A4 inducers with ABILIFY MAINTENA for greater than 14 days. Dosage adjustments are not recommended for patients with concomitant use of CYP3A4 inhibitors, CYP2D6 inhibitors or CYP3A4 inducers for less than 14 days.

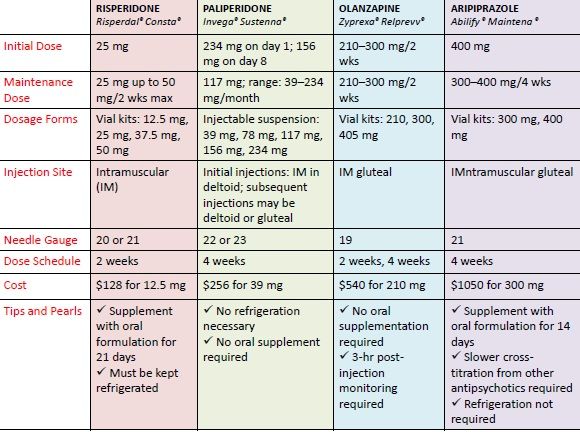

Most Commonly Observed Adverse Reactions: The most commonly observed adverse reactions with ABILIFY MAINTENA in patients with schizophrenia (incidence ≥5% and at least twice that for placebo) were increased weight, akathisia, injection site pain, and sedation.

Injection Site Reactions: In a short-term, clinical trial with ABILIFY MAINTENA in patients with schizophrenia treated with gluteal administered ABILIFY MAINTENA, the percent of patients reporting any injection site-related adverse reaction was 5.4%, and 0.6% for placebo. In an open label study of ABILIFY MAINTENA administered in the deltoid or gluteal muscle, injection site pain was observed at approximately equal rates.

Dystonia: Symptoms of dystonia may occur in susceptible individuals during the first days of treatment and at low doses.

Pregnancy: Neonates exposed to antipsychotic drugs, including ABILIFY MAINTENA, during the third trimester of pregnancy are at risk for extrapyramidal and/or withdrawal symptoms. Consider the benefits and risks of ABILIFY MAINTENA and possible risks to the fetus when prescribing ABILIFY MAINTENA to a pregnant woman. Advise pregnant women of potential fetal risk.

Lactation: Aripiprazole is present in human breast milk. A decision should be made whether to discontinue nursing or to discontinue the drug, taking into account the importance of the drug to the mother and any potential risks to the infant.

A decision should be made whether to discontinue nursing or to discontinue the drug, taking into account the importance of the drug to the mother and any potential risks to the infant.

To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc. at 1-800-438-9927 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 (www.fda.gov/medwatch).

INDICATIONS

ABILIFY MAINTENA® (aripiprazole) is an atypical antipsychotic indicated for:

- Treatment of schizophrenia in adults

- Maintenance monotherapy treatment of bipolar I disorder in adults

Please see , including BOXED WARNING.

Dose Trends of Aripiprazole from 2004 to 2014 in Psychiatric Inpatients in Korea

Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2017 May; 15(2): 177–180.

Published online 2017 May 31. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2017.15.2.177

,1,2,3,4,5,5,6,7,8 and 1

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Objective

Although aripiprazole has been widely used to treat various psychiatric disorders, little is known about the adequate dosage for Asian patients in clinical practice. Hence, we evaluated the initial and maximum doses of aripiprazole from 2004 to 2014 to estimate the appropriate dosage for Korean psychiatric inpatients in clinical practice.

Hence, we evaluated the initial and maximum doses of aripiprazole from 2004 to 2014 to estimate the appropriate dosage for Korean psychiatric inpatients in clinical practice.

Methods

In this retrospective study, we reviewed the medical records of patients who were hospitalized in five university hospitals in Korea from March 2004 to December 2014. The psychiatric diagnosis according to the text revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition during index hospitalization and the initial and maximum doses of aripiprazole were evaluated.

Results

There were 74 patients in Wave 1 (2004–2006), 201 patients in Wave 2 (2007–2010), and 353 patients in Wave 3 (2011–2014). The initial doses of aripiprazole in all diagnostic groups were significantly lower in Wave 3 than in Wave 2. The maximum doses of aripiprazole in each diagnostic group were not significantly different among Waves 1, 2, and 3.

Conclusion

The relatively low initial doses of aripiprazole documented in our study may reflect a strategy by clinicians to minimize the side effects associated with aripiprazole use, such as akathisia.

Keywords: Aripiprazole, Prescribing pattern, Initial dose

Aripiprazole is regarded as a third-generation antipsychotic due to its unique pharmacological profile.1) Its distinct pharmacological profile suggests aripiprazole may be effective in treating various psychiatric disorders.2–6) Moreover, the safety profile of aripiprazole, with low risk of weight gain, sedation and hyperprolactinemia, as well as its relatively high cardiovascular safety in comparison with other atypical antipsychotics,7) may also increase the clinical utility of aripiprazole.

One of the key issues in clinical practice is the choice of antipsychotic dose because it can determine the efficacy and safety/tolerability of treatment. However, published evidence from studies assessing the use of atypical antipsychotics in psychiatric practice show that prescribed doses can diverge from those recommended on the product label.8,9) In real world situations, clinicians may modify their prescribing practices, with some antipsychotics being prescribed at much lower or at much higher doses than originally anticipated, after gaining clinical experience with new medications. 10) Because some side effects such as agitation, akathisia and extrapyramidal symptoms may limit its clinical use,11) and the overall safety and tolerability of aripiprazole is favorable compared to other psychiatric medications, it would be regarded as prudent to aim for the minimum effective dose. However, in spite of attempts to establish a dose-response range for aripiprazole,1,12) little is known about the adequate dosage in clinical practice for Asian patients with various psychiatric disorders.

10) Because some side effects such as agitation, akathisia and extrapyramidal symptoms may limit its clinical use,11) and the overall safety and tolerability of aripiprazole is favorable compared to other psychiatric medications, it would be regarded as prudent to aim for the minimum effective dose. However, in spite of attempts to establish a dose-response range for aripiprazole,1,12) little is known about the adequate dosage in clinical practice for Asian patients with various psychiatric disorders.

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the initial and maximum doses of aripiprazole over a decade to estimate appropriate dosage in clinical practice. We hypothesized that there was a measurable change in dosing patterns during 2004–2014 in Korean psychiatric inpatients.

In this retrospective study, we reviewed the medical records of patients who were hospitalized in the psychiatric ward of five university hospitals in Korea from March 2004 to December 2014. The patients were at least 18 years of age, prescribed aripiprazole during the index hospitalization and were given at least one prescription for oral aripiprazole. Patients who were treated with aripiprazole for a psychiatric disorder before the index hospitalization, who had severe medical conditions which would affect aripiprazole prescription, and were admitted for reasons other than treatment of psychiatric symptoms during index hospitalization, including for social reasons or diagnostic purposes, were excluded.

Patients who were treated with aripiprazole for a psychiatric disorder before the index hospitalization, who had severe medical conditions which would affect aripiprazole prescription, and were admitted for reasons other than treatment of psychiatric symptoms during index hospitalization, including for social reasons or diagnostic purposes, were excluded.

The psychiatric diagnosis according to the text revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV-TR) during index hospitalization and the initial and maximum doses of aripiprazole were evaluated. We also reviewed the demographic and clinical data, including age, sex, marriage, employment, years of education and concomitant medications.

We compared baseline demographic variables among Waves 1 (2004–2006), 2 (2007–2010) and 3 (2011–2014) using univariate one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction for continuous variables and a chi-square test for categorical variables. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with Bonferroni post-hoc pair-wise comparisons, adjusting for the statistically significant variables from univariate analysis including age and concomitant medications, was performed to compare the initial and maximum doses of aripiprazole for each diagnostic group among waves. A p value <0.05 (p<0.017 with Bonferroni’s correction) was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with Bonferroni post-hoc pair-wise comparisons, adjusting for the statistically significant variables from univariate analysis including age and concomitant medications, was performed to compare the initial and maximum doses of aripiprazole for each diagnostic group among waves. A p value <0.05 (p<0.017 with Bonferroni’s correction) was considered to indicate statistical significance.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of each hospital, and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional review board approved the exemption for informed consent because this was a retrospective chart review study.

A total of 628 patients were included in this study. There were 74 patients in Wave 1, 201 patients in Wave 2, and 353 patients in Wave 3. A detailed overview of the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients is presented in . There was a significant difference in mean age among waves (p=0. 012). The mean age of Wave 1 (34.0±10.4) was significantly different from that of Wave 2 (39.9±15.7, p=0.008) and Wave 3 (40.1±17.5, p=0.003).

012). The mean age of Wave 1 (34.0±10.4) was significantly different from that of Wave 2 (39.9±15.7, p=0.008) and Wave 3 (40.1±17.5, p=0.003).

Table 1

Comparisons of baseline demographic and clinical characteristics among Wave 1 (2004–2006), Wave 2 (2007–2010) and Wave 3 (2011–2014)

| Full sample (n=628) | Wave 1 (n=74) | Wave 2 (n=201) | Wave 3 (n=353) | 1 vs. 2 vs. 3 | 1 vs. 2 | 1 vs. 3 | 2 vs. 3 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 39.3±16.4 | 34.0±10.4 | 39.9±15.7 | 40.1±17.5 | 0.012 | 0.008* | 0.003* | 0.849 |

| Male | 252 (40.1) | 34 (45.9) | 81 (40.3) | 137 (38. 8) 8) | 0.522 | 0.400 | 0.255 | 0.730 |

| Married | 261 (41.6) | 23 (31.1) | 88 (43.8) | 150 (42.6) | 0.141 | 0.057 | 0.069 | 0.768 |

| Employed | 334 (53. 2) 2) | 35 (47.3) | 106 (52.7) | 193 (54.8) | 0.490 | 0.424 | 0.247 | 0.660 |

| Education (yr) | 13.0±3.8 | 13.7±2.7 | 13.2±3.2 | 12.7±4.2 | 0.092 | 0.309 | 0. 045 045 | 0.180 |

| Concomitant medication | ||||||||

| Other AAPs | 204 (32.5) | 20 (27.0) | 55 (27.4) | 129 (36.5) | 0.048 | 0.956 | 0.118 | 0.027 |

| MSs | 233 (37.1) | 14 (18.9) | 78 (38. 8) 8) | 141 (39.9) | 0.003 | 0.002* | 0.001* | 0.792 |

| ADs | 239 (38.1) | 31 (41.9) | 57 (28.4) | 151 (42.8) | 0.003 | 0.033 | 0.889 | 0.001* |

| Diagnosis | ||||||||

| SPR | 290 (46. 2) 2) | 57 (77.0) | 96 (47.8) | 137 (38.8) | <0.001 | <0.001* | <0.001* | 0.040 |

| MDD | 138 (22.0) | 7 (9.5) | 41 (20.4) | 90 (25.5) | 0.008 | 0.034 | 0. 003* 003* | 0.175 |

| BP-M | 116 (18.5) | 7 (9.5) | 45 (22.4) | 64 (18.1) | 0.048 | 0.015* | 0.069 | 0.225 |

| BP-D | 41 (6.5) | 1 (1.4) | 10 (5.0) | 30 (8. 5) 5) | 0.043 | 0.174 | 0.031 | 0.123 |

| Others | 43 (6.8) | 2 (2.7) | 9 (4.5) | 32 (9.1) | 0.039 | 0.505 | 0.066 | 0.047 |

Open in a separate window

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

AAPs, atypical antipsychotics; MSs, mood stabilizers; Ads, antidepressants; SPR, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders; MDD, major depressive disorders and other depressive disorders; BP-M, bipolar disorder manic/mixed/hypomanic episode; BP-D, bipolar depressive episode.

*Bonferroni corrected significance of p<0.017 in the post hoc analysis.

The use of concomitant medications with aripiprazole was significantly different among waves, as well. The use of other atypical antipsychotics in Wave 1 was 27.0% (n=20) and 27.4% (n=55) in Wave 2 and increased to 36.5% (n=129) in Wave 3, but the difference between Waves 1 and 3 (p=0.118) and 2 and 3 (p=0.027) did not reach statistical significance after Bonferroni’s correction. However, the concomitant use of mood stabilizers/anticonvulsants with aripiprazole was significantly different between Waves 1 (18.9%, n=14) and 2 (38.8%, n=78, p=0.002), and 1 and 3 (39.9%, n=141, p=0. 001). For anti-depressants, 28.4% of patients in Wave 2 (n=57) and 42.8% (n=151) of patients in Wave 3 were prescribed anti-depressants, which constituted a significant difference (p=0.001).

001). For anti-depressants, 28.4% of patients in Wave 2 (n=57) and 42.8% (n=151) of patients in Wave 3 were prescribed anti-depressants, which constituted a significant difference (p=0.001).

In total, the initial dose of aripiprazole was significantly lower in Wave 3 (7.0±3.9 mg/day) when compared to Waves 1 (10.9±4.6 mg/day, p<0.001) and 2 (10.7±5.6 mg/day, p<0.001). The initial doses of aripiprazole in all diagnostic groups were significantly lower in Wave 3 than in Wave 2 (). When comparing the initial doses of aripiprazole between Waves 3 and 1 in each diagnostic group, there was a significant difference in schizophrenia and other psychotics disorders (11.0±4.1 mg/day in Wave 1, 8.2±3.8 mg/day in Wave 3, p<0.001). The maximum doses of aripiprazole in all subjects and for each diagnostic group were not significantly different among Waves 1, 2, and 3.

Table 2

Comparisons of starting and maximum dose of aripiprazole among Wave 1 (2004–2006), Wave 2 (2007–2010), and Wave 3 (2011–2014)

| Variable | Aripiprazole dose (mg/day) | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Covariate adjusted p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| | ||||||||

1 vs. 2 vs. 3 2 vs. 3 | 1 vs. 2 | 1 vs. 3 | 2 vs. 3 | |||||

| Full sample | Initial | 10.9±4.6 | 10.7±5.6 | 7.0±3.9 | <0.001* | >0.999 | <0.001* | <0.001* |

| Maximum | 21. 2±8.4 2±8.4 | 20.3±9.3 | 18.1±10.5 | 0.142 | >0.999 | 0.368 | 0.325 | |

| SPR | Initial | 11.0±4.1 | 11.9±5.8 | 8.2±3.8 | <0.001* | >0.999 | <0.001* | <0. 001* 001* |

| Maximum | 22.3±8.0 | 23.4±8.0 | 23.3±9.8 | 0.990 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | |

| MDD | Initial | 7.6±2.5 | 6.8±3.8 | 5.0±3.3 | 0. 004* 004* | >0.999 | 0.243 | 0.006* |

| Maximum | 13.6±5.6 | 12.3±6.8 | 10.9±9.1 | 0.297 | >0.999 | >0.999 | 0.419 | |

| BP-M | Initial | 12. 9±8.6 9±8.6 | 12.1±5.0 | 8.6±4.1 | 0.001* | >0.999 | 0.048 | 0.003* |

| Maximum | 22.1±9.1 | 22.9±8.6 | 20.7±7.6 | 0.459 | >0.999 | >0.999 | 0. 651 651 | |

| BP-D | Initial | 15 | 10.5±4.4 | 6.3±2.9 | 0.004* | 0.633 | 0.066 | 0.018* |

| Maximum | 30 | 21.0±10.2 | 16.8±8.5 | 0. 261 261 | >0.999 | 0.537 | 0.814 | |

| Other diagnosis | Initial | 10.0±0.0 | 8.3±.2 | 4.8±2.8 | 0.005* | >0.999 | 0.180 | 0.009* |

| Maximum | 10. 0±0.0 0±0.0 | 9.7±5.1 | 12.0±9.5 | 0.631 | >0.999 | >0.999 | >0.999 | |

Open in a separate window

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation.

SPR, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders; MDD, major depressive disorders and other depressive disorders; BP-M, bipolar disorder manic/mixed/hypomanic episode; BP-D, bipolar depressive episode.

*Bonferroni corrected significance of p<0.017 in the post hoc analysis.

The mean initial dose of aripiprazole in Wave 3 was 7.0±3.9 mg/day for schizophrenic patients and 8.6±4.1 mg/day for bipolar manic/mixed patients which was lower than the recommended dose (10–15 mg/day for schizophrenia and 15 mg/day for bipolar manic/mixed episode) according to the product information sheet. For the treatment of major depressive disorders, 5.0±3.3 mg/day of aripiprazole was prescribed initially in Wave 3, which was in accordance with the product information sheet (2–5 mg/day). The results from the present study show that the initial doses of aripiprazole, and not the maximum doses, decreased in hospitalized psychiatric patients with the accumulation of clinical experience in aripiprazole use. The relatively low initial doses of aripiprazole documented in our study may reflect a strategy by clinicians to minimize the side effects associated with aripiprazole use. One of the most common adverse effects associated with aripiprazole is akathisia which can adversely affect patients’ adherence to medication, potentially leading to reluctance among clinicians in prescribing the drug.11,13,14) In a pooled analysis of short-term aripiprazole clinical trials, the incidence of akathisia was 9.0% in schizophrenia trials, and 17.9% in bipolar trials.15) Although a study analyzing safety and tolerability data from short-term trials with aripiprazole in schizophrenia reported that there was no dose-response relationship with aripiprazole for akathisia,16) a few studies suggested an association between akathisia and dosing of antipsychotics including aripiprazole.

For the treatment of major depressive disorders, 5.0±3.3 mg/day of aripiprazole was prescribed initially in Wave 3, which was in accordance with the product information sheet (2–5 mg/day). The results from the present study show that the initial doses of aripiprazole, and not the maximum doses, decreased in hospitalized psychiatric patients with the accumulation of clinical experience in aripiprazole use. The relatively low initial doses of aripiprazole documented in our study may reflect a strategy by clinicians to minimize the side effects associated with aripiprazole use. One of the most common adverse effects associated with aripiprazole is akathisia which can adversely affect patients’ adherence to medication, potentially leading to reluctance among clinicians in prescribing the drug.11,13,14) In a pooled analysis of short-term aripiprazole clinical trials, the incidence of akathisia was 9.0% in schizophrenia trials, and 17.9% in bipolar trials.15) Although a study analyzing safety and tolerability data from short-term trials with aripiprazole in schizophrenia reported that there was no dose-response relationship with aripiprazole for akathisia,16) a few studies suggested an association between akathisia and dosing of antipsychotics including aripiprazole. Miller et al.17) reported that higher doses or a rapid dose increase of antipsychotics could be a possible risk factor for akathisia. Moreover, Basu and Brar18) suggested that starting aripiprazole at lower doses, either 5 or 10 mg/day, minimizes the risk of akathisia and that starting at doses greater than 30 mg/day increases the risk of schizoaffective disorder. In line with the suggestion by Nelson et al.19) that lowering the starting dose of aripiprazole represents one of the most widely used strategies to minimize the incidence or the severity of akathisia, the results from the present study may reflect clinical experience that a low initial dose could reduce the risk of akathisia.

Miller et al.17) reported that higher doses or a rapid dose increase of antipsychotics could be a possible risk factor for akathisia. Moreover, Basu and Brar18) suggested that starting aripiprazole at lower doses, either 5 or 10 mg/day, minimizes the risk of akathisia and that starting at doses greater than 30 mg/day increases the risk of schizoaffective disorder. In line with the suggestion by Nelson et al.19) that lowering the starting dose of aripiprazole represents one of the most widely used strategies to minimize the incidence or the severity of akathisia, the results from the present study may reflect clinical experience that a low initial dose could reduce the risk of akathisia.

The principal limitation here was the retrospective nature of this work and the relatively small sample size taken from five university hospitals in Korea. Thus, we cannot address the explicit reasons for choosing particular medications and doses with the limited generalizability to other populations. Second, we collected only initial and maximum doses of aripiprazole as a representative value for dosing patterns, and the mean or modal dose was not evaluated. Finally, psychiatric and medical comorbidities in subjects which might affect the prescribing and dosing patterns in the present study were not evaluated. Despite these limitations, this study has strength in that it shows long-term trends in prescribing patterns of aripiprazole. Although “prescribing-based evidence” is not a substitute for “evidence-based prescribing,”9) it would be worthy to update dose trend information through controlled trials in order to test the utility of different dose strategies, as fixed-dose studies of aripiprazole that clearly elucidate the dose-response relationship with effectiveness/tolerability are generally lacking.

Second, we collected only initial and maximum doses of aripiprazole as a representative value for dosing patterns, and the mean or modal dose was not evaluated. Finally, psychiatric and medical comorbidities in subjects which might affect the prescribing and dosing patterns in the present study were not evaluated. Despite these limitations, this study has strength in that it shows long-term trends in prescribing patterns of aripiprazole. Although “prescribing-based evidence” is not a substitute for “evidence-based prescribing,”9) it would be worthy to update dose trend information through controlled trials in order to test the utility of different dose strategies, as fixed-dose studies of aripiprazole that clearly elucidate the dose-response relationship with effectiveness/tolerability are generally lacking.

We found that the initial doses of aripiprazole in all diagnostic groups were significantly lower in 2011–2014 than in 2007–2010. However, there were no significant changes over time in the maximum doses of aripiprazole in each diagnostic group. Although it is not surprising since there are reports indicating that the higher initial doses can provoke more adverse events, this study could be meaningful as we were able to confirm that the evidences are reflected to real clinical practice.

Although it is not surprising since there are reports indicating that the higher initial doses can provoke more adverse events, this study could be meaningful as we were able to confirm that the evidences are reflected to real clinical practice.

1. Di Sciascio G, Riva MA. Aripiprazole: from pharmacological profile to clinical use. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2635–2647. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Stip E, Tourjman V. Aripiprazole in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: a review. Clin Ther. 2010;32( Suppl 1):S3–S20. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.01.021. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Moro MF, Carta MG. Evaluating aripiprazole as a potential bipolar disorder therapy for adults. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2014;23:1713–1730. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2014.971152. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Pae CU, Forbes A, Patkar AA. Aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy for patients with major depressive disorder: overview and implications of clinical trial data. CNS Drugs. 2011;25:109–127. doi: 10.2165/11538980-000000000-00000. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

CNS Drugs. 2011;25:109–127. doi: 10.2165/11538980-000000000-00000. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Farmer CA, Aman MG. Aripiprazole for the treatment of irritability associated with autism. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:635–640. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2011.557661. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Zheng W, Li XB, Xiang YQ, Zhong BL, Chiu HF, Ungvari GS, et al. Aripiprazole for Tourette’s syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2016;31:11–18. doi: 10.1002/hup.2498. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Khanna P, Suo T, Komossa K, Ma H, Rummel-Kluge C, El-Sayeh HG, et al. Aripiprazole versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(1):CD006569. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Hartung DM, Wisdom JP, Pollack DA, Hamer AM, Haxby DG, Middleton L, et al. Patterns of atypical antipsychotic subtherapeutic dosing among Oregon Medicaid patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1540–1547. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v69n1003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2008;69:1540–1547. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v69n1003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Citrome L, Reist C, Palmer L, Montejano L, Lenhart G, Cuffel B, et al. Dose trends for second-generation antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. 2009;108:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.11.017. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Citrome L, Jaffe A, Levine J. Dosing of second-generation antipsychotic medication in a state hospital system. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:388–391. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000169623.30196.b9. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Pae CU. A review of the safety and tolerability of aripiprazole. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2009;8:373–386. doi: 10.1517/14740330902835493. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Mace S, Taylor D. Aripiprazole: dose-response relationship in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:773–780. doi: 10.2165/11310820-000000000-00000. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Kane JM. Extrapyramidal side effects are unacceptable. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001;11( Suppl 4):S397–S403. doi: 10.1016/S0924-977X(01)00109-2. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Kane JM. Extrapyramidal side effects are unacceptable. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001;11( Suppl 4):S397–S403. doi: 10.1016/S0924-977X(01)00109-2. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Ghaemi SN, Hsu DJ, Rosenquist KJ, Pardo TB, Goodwin FK. Extrapyramidal side effects with atypical neuroleptics in bipolar disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30:209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.10.014. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Kane JM, Barnes TR, Correll CU, Sachs G, Buckley P, Eudicone J, et al. Evaluation of akathisia in patients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar I disorder: a post hoc analysis of pooled data from short- and long-term aripiprazole trials. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:1019–1029. doi: 10.1177/0269881109348157. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Marder SR, McQuade RD, Stock E, Kaplita S, Marcus R, Safferman AZ, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of schizophrenia: safety and tolerability in short-term, placebo-controlled trials. Schizophr Res. 2003;61:123–136. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00050-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Schizophr Res. 2003;61:123–136. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00050-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Miller CH, Hummer M, Oberbauer H, Kurzthaler I, DeCol C, Fleischhacker WW. Risk factors for the development of neuroleptic induced akathisia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1997;7:51–55. doi: 10.1016/S0924-977X(96)00041-7. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Basu R, Brar JS. Dose-dependent rapid-onset akathisia with aripiprazole in patients with schizoaffective disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2006;2:241–243. doi: 10.2147/nedt.2006.2.2.241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Nelson JC, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, Fava M, Han J, Van Tran Q, et al. Safety and tolerability of adjunctive aripiprazole in major depressive disorder: A pooled post hoc analysis (studies CN138-139 and CN138-163) Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11:344–352. doi: 10.4088/PCC.08m00744gre. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

90,000 the possibility of using modern antipsychotic aripiprazole (Abilifai) in border psychiatry and general somatic practice (Review of literature) - mental disorders in general medicine No. 02 2010

02 2010

Subscribe to new numbers

The possibility of using the modern antipsychotic aripiprazole (Abilify) in borderline psychiatry and general somatic practice (literature review) No. 02 2010

Author: N.A. Ilyina

NTsPZ RAMS, Moscow

Page numbers in the issue: 45-48

Currently, an increasing number of studies are aimed at developing effective tactics for the treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders. At the same time, the choice of psychotropic drugs is more often based not so much on the use of antidepressants in monotherapy, but on the use of combination therapy with the use of modern antipsychotics. A lot of works have been devoted to the study of these drugs in the treatment of disorders observed in general somatic practice.

Currently, an increasing number of studies are aimed at developing effective tactics for the treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders. At the same time, the choice of psychotropic drugs is more often based not so much on the use of antidepressants in monotherapy, but on the use of combination therapy with the use of modern antipsychotics. A lot of works have been devoted to the study of these drugs in the treatment of disorders observed in general somatic practice. Their results showed a satisfactory safety and tolerability profile of new antipsychotics prescribed in optimal doses, taking into account the age of the patient and the characteristics of the course of the somatic disease [1, 2].

At the same time, the choice of psychotropic drugs is more often based not so much on the use of antidepressants in monotherapy, but on the use of combination therapy with the use of modern antipsychotics. A lot of works have been devoted to the study of these drugs in the treatment of disorders observed in general somatic practice. Their results showed a satisfactory safety and tolerability profile of new antipsychotics prescribed in optimal doses, taking into account the age of the patient and the characteristics of the course of the somatic disease [1, 2].

One such modern antipsychotic is aripiprazole (Abilify). It has been established that the combination of partial agonistic activity against dopamine D2- [3] and serotonin 5HT1A receptors with antagonistic activity against serotonin 5HT2A receptors [4] determines the therapeutic effect of aripiprazole in schizophrenia. In vitro experiments have shown that aripiprazole has a high affinity for dopamine D2- and D3-receptors, serotonin 5HT1A- and 5HT2A-receptors and a moderate affinity for dopamine D4-, serotonin 5HT2C- and 5HT7-, a1-adrenergic receptors and histamine h2 receptors. In addition, the effect of the drug is also characterized by a moderate affinity for serotonin reuptake sites and a lack of affinity for muscarinic receptors. Such a fairly wide pharmacodynamic profile ensures the effectiveness of aripiprazole therapy also in relation to manic states in type I bipolar disorder [5, 6]; studied the possibility of using aripiprazole in bipolar depression [7, 8]. More recently, the drug has been registered as an additional therapy for major depressive disorder in case of insufficient effectiveness of the antidepressants used [10-13].

In addition, the effect of the drug is also characterized by a moderate affinity for serotonin reuptake sites and a lack of affinity for muscarinic receptors. Such a fairly wide pharmacodynamic profile ensures the effectiveness of aripiprazole therapy also in relation to manic states in type I bipolar disorder [5, 6]; studied the possibility of using aripiprazole in bipolar depression [7, 8]. More recently, the drug has been registered as an additional therapy for major depressive disorder in case of insufficient effectiveness of the antidepressants used [10-13].

The data of some authors, given below, suggest the effectiveness of aripiprazole not only in schizophrenia and affective pathology, but also in other (anxiety, obsessive-compulsive, personality - PD) disorders, often associated with somatic diseases.

Aripiprazole in RL therapy

Although the drug has no registered indications for the treatment of LC, some clinical data suggest the presence of pharmacological activity of the drug in personality pathology. As is known, the greatest need for the appointment of psychotropic drugs, in particular antipsychotics, occurs in borderline PD due to the variety of clinical manifestations.

As is known, the greatest need for the appointment of psychotropic drugs, in particular antipsychotics, occurs in borderline PD due to the variety of clinical manifestations.

So, when conducting a double-blind, placebo-controlled study to determine the effectiveness of aripiprazole (a sample that included 52 patients with borderline PD), M. Nickel et al. [14] concluded that aripiprazole at a dose of 15 mg/day provides a statistically significant improvement in the condition of patients compared with placebo.

It should be noted that among the comorbid disorders, patients were diagnosed with: depression (aripiprazole group: n=21 - 80.8%; placebo group: n=22 - 84.6%), anxiety disorders (aripiprazole group: n=16 - 61, 5%; placebo group: n=14 - 53.8%), obsessive-compulsive disorders (aripiprazole group: n=3 - 11.5%; placebo group: n=3 - 11.5%) and somatoform disorders (n= 18 - 69.2% and n=19 - 73.1%, respectively).

A decrease in the values of indicators of obsessive-compulsiveness, hostility in social contacts, depression, anxiety, aggressiveness/hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid thinking, psychomotor functions (scale SCL-90-R) was recorded.![]() An analysis of formalized indicators on the same scale allowed the authors to state that the use of aripiprazole (treatment course for 8 weeks) is accompanied primarily by a reduction in depressive symptoms, while anxiety is subject to a gradual regression. At the same time, according to the Hamilton scales for depression and anxiety (HAM-D and HAM-A), the change in the total score during treatment with aripiprazole versus placebo was not statistically significant. In addition, aripiprazole therapy also contributed to the reduction of manifestations of anger (STAXI scales, which allow assessing the severity of this phenomenon).

An analysis of formalized indicators on the same scale allowed the authors to state that the use of aripiprazole (treatment course for 8 weeks) is accompanied primarily by a reduction in depressive symptoms, while anxiety is subject to a gradual regression. At the same time, according to the Hamilton scales for depression and anxiety (HAM-D and HAM-A), the change in the total score during treatment with aripiprazole versus placebo was not statistically significant. In addition, aripiprazole therapy also contributed to the reduction of manifestations of anger (STAXI scales, which allow assessing the severity of this phenomenon).

In assessing the tolerability of the drug, the authors noted a number of the most common adverse events, including headache, insomnia, nausea, constipation and anxiety. It is important to note that a significant increase in body weight was not registered.

Thus, despite the relatively small sample size, as well as the short duration of the study, the authors concluded that aripiprazole may be effective as a means of not only reducing the symptoms of borderline PD, but also improving the quality of life of patients in terms of health. and interpersonal relationships.

and interpersonal relationships.

This assumption was confirmed in the second (clinical and follow-up) part of the study by M. Nickel et al. [fifteen]. Patients with borderline personality disorder included in the above sample continued to receive aripiprazole at a dose of 15 mg/day for 18 months. The results of a long-term study showed that aripiprazole effectively affects not only depressive, but also dysphoric symptoms (anger, aggression), thereby stabilizing the condition of patients with borderline PD, which is characterized by affective imbalance with the detection of dysphoric outbreaks.

Aripiprazole in the treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders

The data on the effectiveness of aripiprazole in relation to anxiety symptoms in the structure of PD can be supplemented by data obtained from clinical observations, which more fully reveal the spectrum of pharmacological activity of this drug, extending to anxiety and comorbid depressive pathology.

So, D. Adson et al. [16] conducted a 9-week study evaluating the efficacy of aripiprazole in depressed patients with anxiety symptoms who received selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) at stable dosages. The authors noted a significant reduction in all outcome measures after addition of aripiprazole. The study included 10 patients over 18 years of age with a diagnosis of unipolar depression or dysthymia and/or generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder or phobic disorder, with a Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A) score of ≥16. Aripiprazole was prescribed at a starting dose of 5 mg/day with a further increase to a maximum (20 mg/day) by the 4th week. Mean Montgomery Asberg Scale (MADRS) scores decreased from baseline of 28.9±7.3 to 6.5±8.7 by the end of the study (p<0.001). The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) scores also decreased from 18.4 at baseline to 6.7 by the end of the study. The Hospital Anxiety and Depressions Rating Scale (HAD) score decreased from baseline 22. 8 to 9.3. An analysis of the values of the anxiety and depression subscales of the HAD scale also revealed a decrease from 13.3 to 6.1 and from 9.0 to 3.2 points, respectively. When assessing the condition at the stage of follow-up 2 weeks after discontinuation of aripiprazole, some increase in symptoms was detected.

8 to 9.3. An analysis of the values of the anxiety and depression subscales of the HAD scale also revealed a decrease from 13.3 to 6.1 and from 9.0 to 3.2 points, respectively. When assessing the condition at the stage of follow-up 2 weeks after discontinuation of aripiprazole, some increase in symptoms was detected.

Adverse events were minor and resolved after a few days or weeks from the start of aripiprazole. The average increase in body weight of patients was about 3 kg. This fact, contrary to the prevailing idea of the “neutrality” of aripiprazole in relation to changes in body weight, allowed the authors to suggest that in depression, including anxious symptoms, sensitivity to taking psychotropic drugs increases, and accordingly, there is a risk of weight gain during aripiprazole therapy. The authors also suggested that akathisia and other extrapyramidal symptoms in patients with affective disorders may be due to an increase in the concentration of aripiprazole when combined with antidepressants that have the ability to inhibit the CYP2D6 enzyme. Some limitations of the study were noted: open design, short duration, the possibility of a placebo effect and inadequate dosages of SSRIs.

Some limitations of the study were noted: open design, short duration, the possibility of a placebo effect and inadequate dosages of SSRIs.

M. Kellner [17] reported on a 25-year-old patient who, according to the DSM-IV criteria, was diagnosed with chronic post-traumatic stress disorder along with bipolar affective disorder after a series of massive psycho-traumatic effects. The clinical picture revealed signs of social phobias and trichotillomania. After repeated attempts at therapy with serotonergic antidepressants, as well as some atypical antipsychotics used in high doses, without significant improvement in the condition, in addition, sedation was noted. Administration of aripiprazole at a dose of 15 to 30 mg/day resulted in stabilization of mood, a significant reduction in anxiety, nightmares, and relief of symptoms of trichotillomania. When taking aripiprazole up to 45-60 mg / day (the patient increased the dose of the drug on her own), a further decrease in the severity of anxiety, dysphoric disorders and auto-aggression without sedation and other undesirable effects was noted. This observation led the authors to conclude that the use of aripiprazole "may be an available option for treatment-resistant patients with bipolar and/or post-traumatic stress disorder."

This observation led the authors to conclude that the use of aripiprazole "may be an available option for treatment-resistant patients with bipolar and/or post-traumatic stress disorder."

Aripiprazole in the treatment of schizophrenia with comorbid social phobia

R. Stern et al. [18] reported preliminary results from a study whose working hypothesis was that switching to aripiprazole reduces the severity of social phobias that develop within schizophrenia. The dynamics of psychopathological disorders was assessed using the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS), Sheehan's Disability Scale (SDS), and the Lehman's Quality of Life Interview (B-QOLI) questionnaire - an abbreviated version. Pre-study neuroleptic therapy was gradually (by cross-titration) replaced with aripiprazole (maximum daily dose of 30 mg). Patients who completed the 8-week study in the acute phase were eligible to participate in the extended phase for a further 10 months. 9patients included in the extended phase, by the 12th month, there was a significant (compared to the values on the 56th day of the study) decrease in social phobia scores (overall score on the LSAS scale, avoidance, anxiety), social disability (overall score on the Sheehan scale as well as work, social activity, and family items), general functioning and emotional well-being (B-QOLI), and psychotic symptoms (PANSS total score). The authors concluded that these preliminary data, indicating a reduction not only in psychosis, but also in social phobia, as well as an improvement in the quality of life of patients when switching to aripiprazole therapy, dictate the need for further research in this direction.

The authors concluded that these preliminary data, indicating a reduction not only in psychosis, but also in social phobia, as well as an improvement in the quality of life of patients when switching to aripiprazole therapy, dictate the need for further research in this direction.

Aripiprazole add-on therapy study

J. Worthington et al. [19] reported an increase in the action of SSRIs with the addition of aripiprazole in 17 patients with treatment-resistant depression or anxiety, according to a retrospective, open-label pilot study. In 71% of patients, previous therapy with atypical antipsychotics was unsuccessful. The performance parameters in this study were the scores on the CGI-I and CGI-S scales.

Overall, the mean aripiprazole dosage was 17 mg (range, 7.5 to 30 mg/day) and the mean duration of therapy was 4.9 ± 3 weeks (range, 1 to 12 weeks). By the end of the study, the total scores on the CGI-S scale decreased significantly (from 5.4 to 3.8; p<0. 001). Therapeutic response, defined in CGI-I scores as "very marked improvement" or "marked improvement", was observed in 10 (59%) of 17 patients, according to the analysis of "intent-to-treat" (analysis of data from all patients, included in the study), in 8 (67%) of 12 patients who completed the study. Of the 17 patients, 5 prematurely discontinued participation in the study: 3 due to adverse events, 1 due to insufficient therapeutic effect, 1 due to economic reasons. In 5 of 17 patients, no adverse events were noted.

001). Therapeutic response, defined in CGI-I scores as "very marked improvement" or "marked improvement", was observed in 10 (59%) of 17 patients, according to the analysis of "intent-to-treat" (analysis of data from all patients, included in the study), in 8 (67%) of 12 patients who completed the study. Of the 17 patients, 5 prematurely discontinued participation in the study: 3 due to adverse events, 1 due to insufficient therapeutic effect, 1 due to economic reasons. In 5 of 17 patients, no adverse events were noted.

E.Hoge et al. [20] reported an 8-week, open-label, prospective, booster study investigating the efficacy and tolerability of aripiprazole in adult outpatients with GAD (n=13) or panic disorder (n=10) who also had somatovegetative disturbances despite for a previous at least 8 weeks of treatment with conventional methods of pharmacotherapy in adequate doses. As a result of the addition of aripiprazole, a significant reduction in psychopathological symptoms was achieved according to the CGIS-S scale (paired values t=4. 41, df=22, p<0.001) in an intent-to-treat sample of 23 patients. The authors concluded that the findings suggest a possible use of an augmentation strategy in patients with GAD or panic disorder who show insufficient response to prior psychopharmacotherapy.

41, df=22, p<0.001) in an intent-to-treat sample of 23 patients. The authors concluded that the findings suggest a possible use of an augmentation strategy in patients with GAD or panic disorder who show insufficient response to prior psychopharmacotherapy.

Aripiprazole for GAD

M.Menza et al. [21] in an open 6-week pilot study studied the possibility of increasing the effectiveness of treatment of therapeutically resistant GAD (comorbid depression was detected in 8 patients) by adding aripiprazole in 9 patients (18–65 years old). Aripiprazole was prescribed at a dose of 10 mg/day with subsequent adjustment according to tolerability and therapeutic response. The prescribed antidepressant, if necessary, was combined with benzodiazepines or sedative hypnotics at a stable dosage for 6 weeks.

Of the 9 patients, 8 completed the study. The Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A) score decreased from baseline 26.2 to 14 (p<0.0001), and 89% of patients had a CGI score of “marked improvement” or “very marked improvement” at the end of the study. ". 5 patients were assessed as HAM-A responders (score reduction by at least 50%), and 1 patient was in remission (HAM-A score <10). The mean dosage at the end of the study was 13.9mg/day Significant improvement was also noted in relation to depressive symptoms. Mean values on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) were 21.6 points at baseline and 11.8 points at the end of the study (p=0.0004). The indicators of the SF-36 subscales also improved: social functioning, state of health, activity, emotional manifestations. At the same time, the SF-36 Physical Feeling Subscales and the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS) scores remained unchanged. In 3 patients during the 1st week of therapy, the phenomena of akathisia were noted. Other mild to moderate adverse events included headache (1 patient), nausea (1), dizziness (1), fatigue and blurred vision (1), weight gain (10 lb gain), and increased anxiety (1 patient). ). All of these events (with the exception of weight gain) resolved in 8 patients who completed the study.

". 5 patients were assessed as HAM-A responders (score reduction by at least 50%), and 1 patient was in remission (HAM-A score <10). The mean dosage at the end of the study was 13.9mg/day Significant improvement was also noted in relation to depressive symptoms. Mean values on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) were 21.6 points at baseline and 11.8 points at the end of the study (p=0.0004). The indicators of the SF-36 subscales also improved: social functioning, state of health, activity, emotional manifestations. At the same time, the SF-36 Physical Feeling Subscales and the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS) scores remained unchanged. In 3 patients during the 1st week of therapy, the phenomena of akathisia were noted. Other mild to moderate adverse events included headache (1 patient), nausea (1), dizziness (1), fatigue and blurred vision (1), weight gain (10 lb gain), and increased anxiety (1 patient). ). All of these events (with the exception of weight gain) resolved in 8 patients who completed the study.

G.Kinrys et al. [22] studied the efficacy of aripiprazole in treatment of therapeutically resistant GAD with somatic and autonomic symptoms (tachycardia, cardialgia, nausea, etc.). In an open study, 12 patients (mean age 48.9 years, 66.7% women) with GAD who did not achieve a clinical response to adequate anxiolytic therapy received aripiprazole for 8 weeks. The primary outcome measures were Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A), CGI-S CGI-I. Completed research 9patients, of which 8 (88.8%) were regarded as responders. Intent-to-treat analysis (ITT - analysis of data from all patients included in the study) identified 9 (75%) responders. The total number of patients in remission (according to ITT) was 7/9 and 7/12.

The most frequently observed adverse events were sedation, fatigue, agitation and nervousness.

The authors concluded that aripiprazole may enhance the efficacy of anxiolytic therapy in patients with therapeutically resistant GAD with somatovegetative manifestations.

C. Rae et al. [23] presented a review of preclinical and preliminary data on the use of aripiprazole in the treatment of depressive and anxiety disorders. The authors indicate that clinical studies demonstrate the possibility of using aripiprazole in the treatment of bipolar depression, major depressive disorder, treatment-resistant depression, and possibly anxiety disorders. Moreover, clinical data show that aripiprazole has fewer side effects than other atypical drugs. The authors note that future studies may confirm the potential use of aripiprazole in the treatment of depressive and anxiety disorders.

Aripiprazole and HIV

Aripiprazole is the first drug approved by the FDA as an adjuvant in the treatment of depression, but the therapeutic response when using the drug in patients with HIV is not well understood. One of the few publications indicating that aripiprazole therapy can reduce the severity of depressive symptoms and improve immunoreactivity during antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection belongs to C. Cechelli et al. [24]. The authors present a casuistic observation in which they discussed a patient with a verified at 1997 HIV. Since then, he has received antiretroviral therapy. Blood tests showed a decrease in the number of CD4+ cells and a positive viral load. Since the spring of 2008, the patient began to experience attacks of trembling and nausea with vomiting, diarrhea, tremors and paresthesias. The condition was accompanied by complaints of headaches, dorsalgia, insomnia, fatigue, loss of appetite, performance, concentration. A fixation on the problems of his own health was revealed: he repeatedly turned to various specialists for help. Of the psychotropic drugs, he took lorazepam (3 mg/day), trimipramine (100 mg/day) for 8 weeks, paroxetine (20 mg/day) for 10 weeks, and mirtazapine (30 mg/day) for 12 weeks without clinical effect.

Cechelli et al. [24]. The authors present a casuistic observation in which they discussed a patient with a verified at 1997 HIV. Since then, he has received antiretroviral therapy. Blood tests showed a decrease in the number of CD4+ cells and a positive viral load. Since the spring of 2008, the patient began to experience attacks of trembling and nausea with vomiting, diarrhea, tremors and paresthesias. The condition was accompanied by complaints of headaches, dorsalgia, insomnia, fatigue, loss of appetite, performance, concentration. A fixation on the problems of his own health was revealed: he repeatedly turned to various specialists for help. Of the psychotropic drugs, he took lorazepam (3 mg/day), trimipramine (100 mg/day) for 8 weeks, paroxetine (20 mg/day) for 10 weeks, and mirtazapine (30 mg/day) for 12 weeks without clinical effect.

In September 2008, he was admitted to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with resistant depression, somatoform disorder (hypochondria) and panic disorder. Combination therapy with citalopram 40 mg/day and aripiprazole (up to 15 mg/day) was prescribed. During the treatment, the patient's depressive and somatoform symptoms were reduced, professional adaptation was restored. In parallel, hematological and immunological parameters improved (an increase in the number of CD4 cells and a negative viral load were recorded).

Combination therapy with citalopram 40 mg/day and aripiprazole (up to 15 mg/day) was prescribed. During the treatment, the patient's depressive and somatoform symptoms were reduced, professional adaptation was restored. In parallel, hematological and immunological parameters improved (an increase in the number of CD4 cells and a negative viral load were recorded).

The authors believe that the addition of low doses of aripiprazole (up to 15 mg/day) increases the effectiveness of therapy in patients with symptoms of resistance to antidepressant monotherapy (SSRIs, tricyclic antidepressants), and indicate the prospect of further studying the effectiveness of aripiprazole in HIV-infected patients with concomitant depression.

Conclusion

The above data on the efficacy and tolerability of the modern antipsychotic aripiprazole can be considered as confirmation of the possibility of its use not only in schizophrenia, type I bipolar disorder and unipolar depression, but also as an adjuvant therapy in patients with anxiety disorders and psychosomatic disorders. Aripiprazole can also be used to correct a wide range of symptoms (obsessive-compulsive, dysphoric, etc.) observed in PD. Own data obtained in clinical practice can also serve as an additional argument in favor of the effectiveness of aripiprazole for the treatment of these conditions, and a favorable tolerability profile makes it possible to use this antipsychotic for the correction of psychopathological disorders in somatic patients.

Aripiprazole can also be used to correct a wide range of symptoms (obsessive-compulsive, dysphoric, etc.) observed in PD. Own data obtained in clinical practice can also serve as an additional argument in favor of the effectiveness of aripiprazole for the treatment of these conditions, and a favorable tolerability profile makes it possible to use this antipsychotic for the correction of psychopathological disorders in somatic patients.

Credits:

Ilyina Natalya Alekseevna - Dr. med. sciences, ved. scientific collaborator NCPZ RAMS. 115522, Moscow, Kashirskoe sh., 34;

tel. 8 499 616-18-56

List of used literature Hide list

May 10, 2010

Views: 3025

Previous articleComplex therapy of patients with psoriasis vulgaris with trigger stress factor

Next articlePossibilities of correcting mild cognitive impairment in elderly and senile patients in general medical practice

Aripiprazole

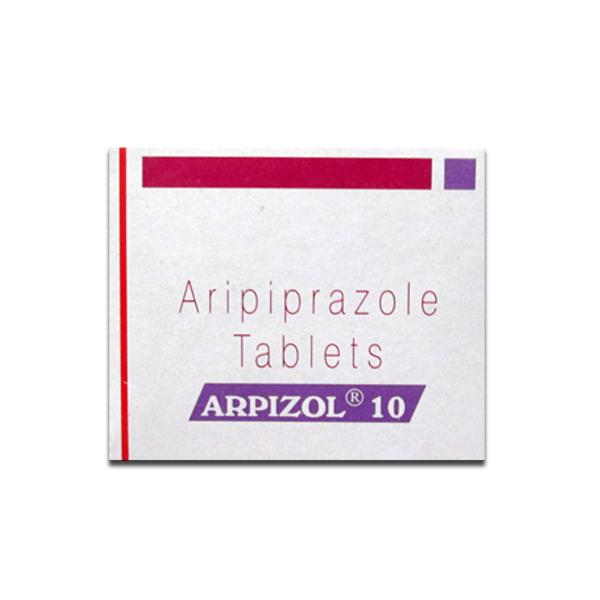

Chemical group: aripiprazole (Abilify) a quinolinone derivative.

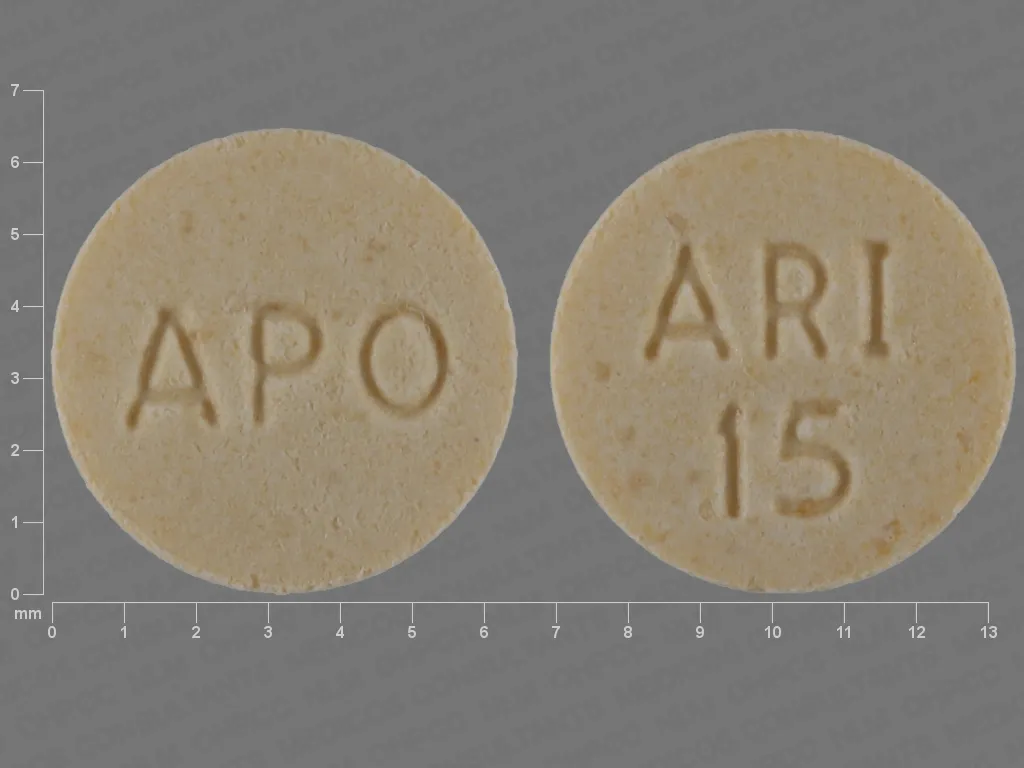

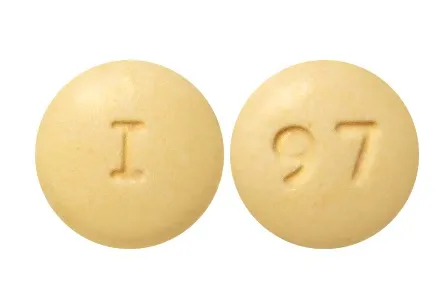

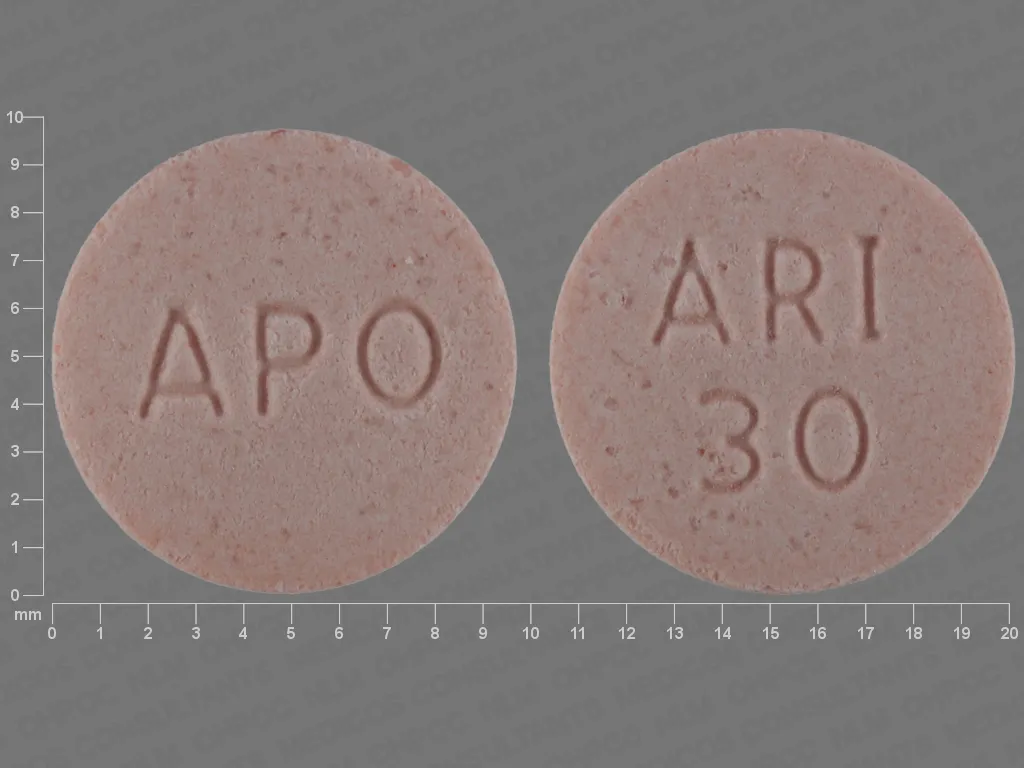

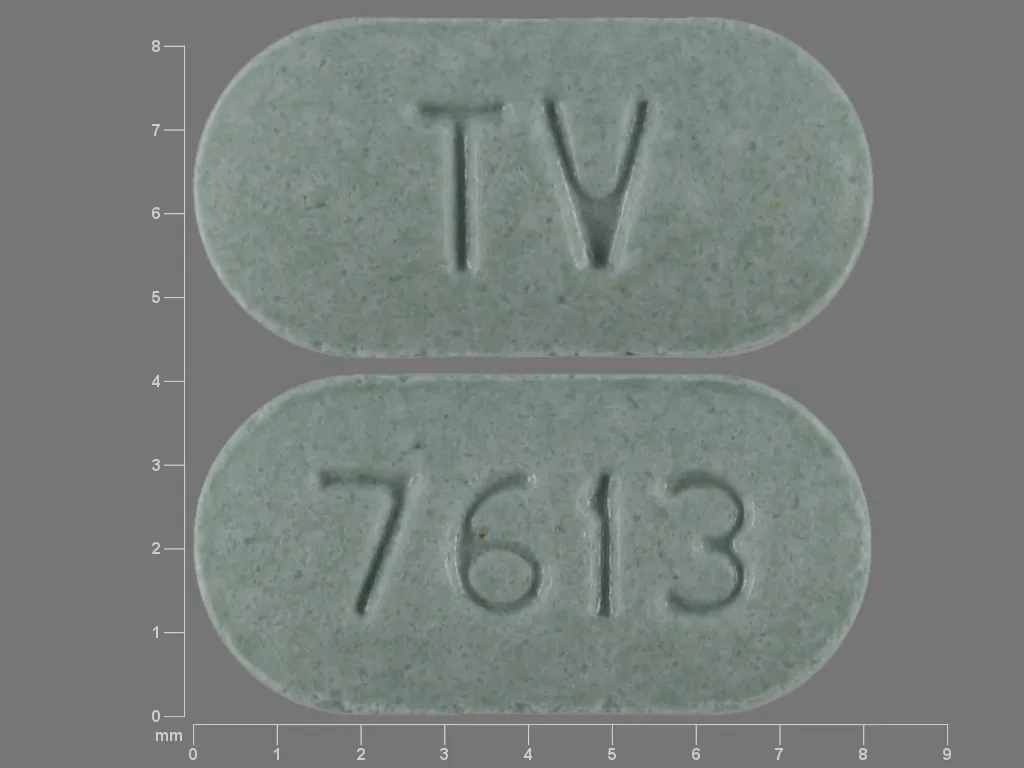

Formulation: Aripiprazole is available in tablets of 2, 5, 10, 15, 20 and 30 mg

Pharmacokinetics: Aripiprazole has an average half-life of approximately 75 hours, so the drug can be administered once a day. The maximum concentration of aripiprazole in plasma is reached after 3-5 hours. Absolute bioavailability is 87%. Equilibrium concentration is reached after 14 days. The main metabolite of the drug is dehydroaripiprazole, has the same affinity for dopamine receptors as aripiprazole, its half-life is 94 o'clock.

Dosage regimen: starting dose of the drug 10-15 mg per day. The same dose is considered the minimum for the relief of acute exacerbation of schizophrenia.

Average daily therapeutic doses of aripiprazole correspond to 20-30 mg, maintenance therapy can be carried out at the level of 15-20 mg. After reaching the optimal dose of the drug (15-20 mg), its correction is usually carried out after 2-3 weeks. According to a number of authors, 30 mg should be considered the most effective daily dose of the drug.

According to a number of authors, 30 mg should be considered the most effective daily dose of the drug.

A relatively low initial dose of the drug is especially necessary in elderly patients and in combination with other psychotropic drugs.

The drug can be taken at any time of the day, regardless of food intake.

Unlike some AAs, aripiprazole does not require dose adjustment in smokers and can also be used for renal and mild liver failure.

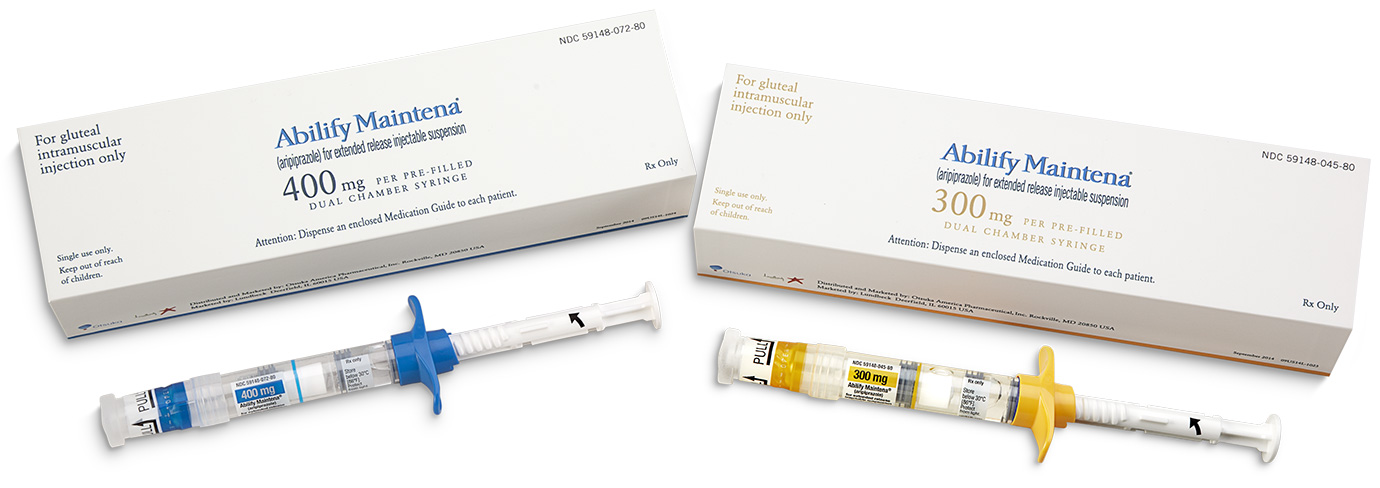

An injectable form of aripiprazole is currently being developed for intramuscular administration of the drug.

Mechanism of action: Aripiprazole is an atypical antipsychotic that increases dopamine activity in areas of the brain where it is reduced (mesocortical structures) and decreases dopamine activity in those brain structures where it is, on the contrary, increased (mesolimbic structures).

In the first case, the clinical effect of aripiprazole is manifested by a reduction in negative symptoms, in the second case, by relief of positive symptoms.

Aripiprazole is considered a stabilizer of the dopamine system and the first partial agonist of dopamine receptors (D2), but its stimulation of these receptors is somewhat inferior in intensity to the actual stimulation of dopamine. The concept of "partial agonist" emphasizes that the effect of aripiprazole depends on the initial state of the functional activity of the dopamine network.

Aripiprazole is also a serotonin 5HT2A antagonist and a partial serotonin 5HT1A receptor agonist, the first feature explains the absence of a decrease in the seizure threshold, the second is the presence of anxiolytic activity in this drug.

Aripiprazole shows moderate sensitivity to D4, 5HT2C, 5HT7, h2 receptors.

The peculiar mechanism of action of the drug avoids negative effects on the receptors of neurons in the nigrostriatal and tuberoinfundibular regions, manifested in extrapyramidal symptoms and hyperprolactenemia.

Thus, aripiprazole can be considered the first neuromodulator (stabilizer) in relation to the dopaminergic and serotonergic systems of the central nervous system.

Aripiprazole has moderate activity at alpha1-adrenergic, histamine and serotonin 5HT2C receptors.

Indications: the drug is distinguished by a pronounced reduction in positive and negative symptoms, cognitive impairment, stable maintenance of the effect with long-term use of the drug.

Aripiprazole has a distinct preventive and anti-relapse activity.

Indications for treatment of schizophrenia with aripiprazole

- Prevention of schizophrenia in boys over 18 years of age

- Severe manifestations of negative symptoms

- Severe manifestations of cognitive deficits, especially verbal memory impairment

- Supportive care

- Comorbid neurotic disorders, depressive spectrum disorders

While taking aripiprazole, there is a significant improvement in secondary verbal memory, one of the components that determine the primary and repeated reproduction, as well as the categorization of a list of words. Taking the drug enhances the activity of patients with schizophrenia, increases motivation, promotes the acquisition of new skills, improves the ability to solve social problems by regulating interpersonal relationships.

Taking the drug enhances the activity of patients with schizophrenia, increases motivation, promotes the acquisition of new skills, improves the ability to solve social problems by regulating interpersonal relationships.

In comparative studies of the effectiveness of the drug with an antipsychotic such as haloperidol, aripiprazole was comparable in terms of the strength of the effect, but markedly outperformed in terms of safety of use.

At the same time, some authors noted an increase in the severity of mania among the adverse clinical effects of aripiprazole. Some authors note the effectiveness of aripiprazole in the presence of psychotic seizures that are not accompanied by psychomotor agitation, pronounced affects of fear and anxiety (Ivanov M.V. et al., 2007).

American psychiatrists note the effectiveness of aripiprazole in the treatment of patients with borderline disorder (according to the DSM1V classification).

Aripiprazole reduces the severity of depressive symptoms.

Side effects: the absence of daytime sleepiness and lethargy in 90% of patients treated with aripiprazole makes it attractive to many patients. However, at a dosage of 15 mg, sedation and drowsiness may occur in 10% of patients, at the level of 30 mg, similar symptoms were recorded in 15% of patients.

Side effects of aripiprazole:

- Psychiatric disorders: mania, anxiety (25%)

- Neurological disorders: headache (32%), insomnia (24%), dizziness (11%), akathisia (10%)

- Gastroenterological disorders: nausea (14%), vomiting (12%), constipation (10%)

- Rare cardiovascular disorders: vasovagal syndrome, arrhythmias

The drug does not increase weight, the level of prolactin in the blood. Due to the fact that aripiprazole, as a rule, blocks less than 70% of dopamine D2 receptors, it practically does not cause extrapyramidal symptoms, which, on average, are recorded only in 6-13% of cases, more often manifesting as tremor and akathisia.