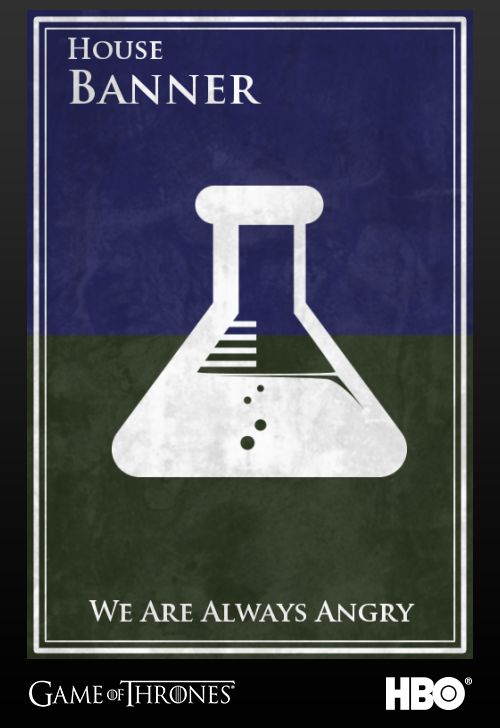

My daughter is always angry

Anger, Irritability and Aggression in Kids > Fact Sheets > Yale Medicine

Overview

Nobody likes to feel angry, but we all experience the emotion from time to time. Given that many adults find it hard to express anger in ways that are healthy and productive, it’s unsurprising that angry feelings often bubble into outbursts for children. Most parents find themselves wondering what to do about tantrums and angry behavior, and more than a few wonder whether the way their child behaves is normal.

At the Yale Medicine Child Study Center, we work with children and their families to develop plans for each behavioral goal. We offer a variety of evaluations and treatment plans.

When is anger, irritability, and aggression unhealthy in a child?

It’s not unusual for a child younger than 4 to have as many as nine tantrums per week. These can feature episodes of crying, kicking, stomping, hitting and pushing that last five to 10 minutes, says Denis Sukhodolsky, PhD, a clinical psychologist with Yale Medicine Child Study Center. Most children outgrow this behavior by kindergarten. For children whose tantrums continue as they get older and become something that is not developmentally appropriate, professional help may be in order. According to Sukhodolsky, anger issues are the most common reason children are referred for mental health treatment.

What causes anger, irritability, and aggression in children?

Multiple factors can contribute to a particular child’s struggles with anger, irritability, and aggression (behavior that can cause harm to oneself or another). One common trigger is frustration when a child cannot get what he or she wants or is asked to do something that he or she might not feel like doing. For children, anger issues often accompany other mental health conditions, including ADHD, autism, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and Tourette’s syndrome.

Genetics and other biological factors are thought to play a role in anger/aggression. Environment is a contributor as well. Trauma, family dysfunction and certain parenting styles (such as harsh and inconsistent punishment) also make it more likely that a child will exhibit anger and/or aggression that interferes with his or her daily life.

Trauma, family dysfunction and certain parenting styles (such as harsh and inconsistent punishment) also make it more likely that a child will exhibit anger and/or aggression that interferes with his or her daily life.

How is anger, irritability, and aggression in children diagnosed?

Young children may be taken in for a psychological or psychiatric evaluation by their parents or be referred by a pediatrician, psychologist, teacher or school administrator. Older children with behavioral problems that bring them in contact with the law may be sent for evaluation and treatment by the courts or juvenile justice system. (Sukhodolsky notes that this is exactly what earlier treatment aims to prevent.)

When assessing the breadth and depth of a child’s anger or aggression, a provider will look at the behaviors in the context of the child’s life. This includes obtaining input from parents and teachers, reviewing academic, medical, and behavioral records, and conducting one-on-one interviews with the child and parent. “We look at the full spectrum of mental health disorders and how they are affecting a child’s life,” Sukhodolsky says.

“We look at the full spectrum of mental health disorders and how they are affecting a child’s life,” Sukhodolsky says.

Sukhodolsky adds that research-based measurement tools, such as answers parents and child give to specific questions, are used to determine whether a child meets diagnostic criteria for a behavioral disorder. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V), which is considered the “bible” of diagnoses, potential diagnoses for a child with anger, irritability and aggression include:

- Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), a pattern of angry/irritable mood, argumentative/defiant behavior and/or spitefulness that lasts six months or more

- Conduct disorder (CD), a persistent pattern of behavior that violates the rights of others, such as bullying and stealing, and/or age appropriate norms, such as truancy from school or running away from home

- Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD), characterized by frequent angry outbursts and irritable or depressed mood most of the time

Sometimes clinicians may use terms that are not part of the DSM but have been used in research, education or advocacy. For example, “severe mood dysregulation” is a term that refers to a combination of irritable mood and angry outbursts/aggressive behavior in children with mood disorders and ADHD. In the area of Tourette’s syndrome, the term “rage attacks” has been used to describe the anger outbursts that are often out of proportion to provocation and out of character to the child’s personality.

For example, “severe mood dysregulation” is a term that refers to a combination of irritable mood and angry outbursts/aggressive behavior in children with mood disorders and ADHD. In the area of Tourette’s syndrome, the term “rage attacks” has been used to describe the anger outbursts that are often out of proportion to provocation and out of character to the child’s personality.

How is anger, irritability, and aggression in children treated?

Behavioral intervention is the first line of treatment for childhood anger and aggression. Though there are quite a few therapies that can be helpful, the Child Study Center emphasizes two primary approaches that focus on changing the interpersonal dynamics that lead to and result from angry outbursts. These are complementary therapies that address a child’s behavior problems from different directions.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a three-pronged approach that helps a child acquire new and more effective strategies for regulating angry emotions, thoughts, and behaviors.

- Emotion regulation, which allows the child to learn to identify anger triggers and preventive strategies.

- Learning alternate ways to express and address frustration will help the child and parent weigh the potential consequences of each choice and minimize conflict.

- Developing new communication strategies, via with role-play for practice, helps to prevent and resolve anger-provoking situations.

Even though CBT is conducted with the child, parents actively participate in treatment and support child’s progress towards learning anger management skills.

- Parent management techniques (PMT) helps parents limit outbursts by teaching alternative ways to handle misbehavior. The focus is on using positive reinforcement for what a child does right, rather than punishment for transgressions. PMT emphasizes positive interaction in families as rewards. “We help families enjoy spending time together.

It becomes a child’s biggest motivation for reducing angry outbursts,” Sukhodolsky says.

It becomes a child’s biggest motivation for reducing angry outbursts,” Sukhodolsky says.

Some children also take medication to help manage other mental health conditions (such as ADHD, anxiety, or depression). But cognitive behavioral therapy and parent management techniques (which have a 65 percent success rate in reducing the frequency and intensity of outbursts) are the primary treatments.

Other approaches may be tried if a child doesn’t respond, Sukhodolsky says, adding that some children need more intensive outpatient services or even inpatient treatment. “A life of emotional intensity doesn’t feel good so our focus and treatment goal is to help the child feel better and not suffer,” he says.

What makes Yale Medicine's approach to anger, aggression, and irritability in children unique?

Anger and aggression are complex problems. A key benefit of seeking treatment from us is being able to access the resources of Yale University and Yale New Haven Hospital. “Oftentimes, one approach doesn’t work in isolation,” Sukhodolsky says, adding that Yale provides access to a wide range of mental health services for children with complicated mental health conditions and behavioral problems.

“Oftentimes, one approach doesn’t work in isolation,” Sukhodolsky says, adding that Yale provides access to a wide range of mental health services for children with complicated mental health conditions and behavioral problems.

Also notable is the Child Study Center’s commitment to treating children within the context of the family, with great sensitivity to culture and to each family’s values and lifestyle. For example, Sukhodolsky says, showing respect for grandparents may be culturally important to a particular family. “Some kids need a bit of extra training in how to be respectful,” he says, “so we develop a plan for each and every behavioral goal.” Parents also learn to be respectful of things that matter to the child, and siblings are sometimes included in the treatment.

Whether the goal is accomplishing chores or getting to school on time, the approach is the same. “We develop a realistic plan that takes about three months or so of weekly effective therapy to change behavior and that includes behaviors of the child and the parents and often the behavior of the siblings,” Sukhodolsky says.

Yale is widely known as a preeminent research institution exploring, creating and shaping new treatments for children with mental health challenges. Doctors at Yale are focused on understanding the efficacy of treatments with the goal of predicting who is most likely to respond to which approach. “A lot of what we do here at the Child Study Center is randomized control trials to understand which forms of psychotherapy are effective,” Sukhodolsky says.

Why Is My Child or Teen So Angry?

Have you found yourself asking the question, “Why is my child always so angry at me?”

Do you feel like your adolescent surrounds himself or herself with a force field of anger and hostility?

In this article, James Lehman, creator of The Total Transformation® child behavior program, discusses anger, hostility, and your child.

Understanding Anger and Hostility

First of all, it’s important to make a distinction between anger and hostility. When you’re angry, you feel as if you’ve been wronged, and you want to strike back somehow.

When you’re angry, you feel as if you’ve been wronged, and you want to strike back somehow.

We all get angry from time to time—it’s a natural reaction to certain situations. Well adjusted kids and adults get angry but can manage their anger when it arises.

In contrast, hostility is an attitude of defensiveness and waiting for an attack. Hostility is related to antagonism, animosity, and hatred. What a lot of parents experience as defiance is, in most cases, hostility.

Think of it this way: hostility is the attitude. And the attitude says, “Don’t mess with me.” Hostility is constant and full of bad intentions.

“My Child is Angry and Hostile All the Time”

I often describe angry kids as having a “force field of hostility” around them at all times. Even if you innocently ask your teen, “How was your day?” you get a response full of contempt and disrespect. Or you get no response at all. This is hostility. And as many parents know, it’s tough to deal with a child who behaves this way.

What can a parent do when their child is hostile toward them all the time?

Some parents will punish their child for having an attitude. Other parents will yell, scream, and threaten. Unfortunately, these responses are ineffective.

I tell parents that if screaming at our kids was effective, I’d be out of business. You’d just yell at your child, and they’d change. Or you’d bring your child to my office, I’d shout at them and call them names for 45 minutes, and then they’d go home and be nice for a week.

The right response addresses the underlying problem—the hostility—and motivates your child to solve that problem by taking responsibility for their hostile behavior.

Anger, Hostility, and Thinking Errors

Hostile adolescents have a distorted way of thinking whereby they are always the victim. Their distorted thinking tells them that things aren’t fair, that their parents have placed too many expectations on them, that their teachers are idiots. They believe that nobody understands them except for their friends.

They believe that nobody understands them except for their friends.

In some kids, this further develops into a general air of, “I hate you. I’m against you.” And it leads to frequent bursts of anger.

Distorted thinking is what psychologists call thinking errors. Thinking errors are the thoughts we have that don’t match reality and are usually negative and self-defeating. And, as you might expect, those who commit thinking errors don’t realize that their thoughts don’t match reality.

Teens who employ thinking errors think that they’re always the victim. In their minds, they’re the victim of you. You’re the enemy. Or they’re the victims of their teachers who are “out to get them,” according to your teen.

When kids with thinking error face consequences, they don’t connect the consequence with their behavior. Instead, they view the consequences as further evidence that they are a victim of the people out to get them.

After using these thinking errors for a while, they get into more and more trouble and develop an increasing sense of hypervigilance. Faced with criticism or challenge, they either attack or shut down. These are the kids whose parents say to me: “I can’t even get two words out of my mouth and he’s running up the stairs” or “She’s screaming at me all the time.”

Faced with criticism or challenge, they either attack or shut down. These are the kids whose parents say to me: “I can’t even get two words out of my mouth and he’s running up the stairs” or “She’s screaming at me all the time.”

Related content: The Secret to Understanding Acting-Out Behavior: 5 Common Thinking Errors Kids Make

Accountability Is the Key to Managing Hostility

To end the hostility, the thinking-errors need to be corrected. And you address the thinking-errors by holding your child accountable for his actions so that they eventually learn to take responsibility for their behavior.

Indeed, taking responsibility for behavior is necessary for any long-lasting improvements in behavior. It’s the basis of The Total Transformation® child behavior program that I developed, and it’s the basis of the authoritative parenting style, which stresses setting and enforcing limits and, at the same time, expects parents to coach their kids to become independent and self-disciplined.

“I’m Afraid to Ask My Child to Do Anything”

Parents tell me that they are afraid to ask their hostile child or teen to do anything because it just provokes an angry outburst. Parents reason that it’s better to leave the kid alone than it is to deal with the anger.

But parents have to understand that the purpose of anger and hostility is to keep you away. Hostility and anger are like a porcupine’s quills—when you get too close, you get pricked, and it hurts.

Hostile kids are like porcupines all the time. You try to talk to them, and they glare at you the way a porcupine warns you away with his quills. You try to get closer, and next thing you know, you’re full of quills in the form of a nasty outburst.

And it’s not just with you. They’re often nasty to their siblings. These kids often prefer to hide out in their rooms and avoid contact with the family.

There’s no such thing as a pleasant conversation with them. And if you ask these kids for anything, they reply with an angry outburst.

So now your child’s attitude is, “Don’t mess with me…don’t mess with me…don’t mess with me…POW! Now you did it.” And then an hour later, or the next day, the same thing happens again.

Parents learn to avoid making their kids explode, and, as a result, the behavior continues because it has the intended effect of keeping you away.

“My Child Will Hate Me If I Give Them Consequences”

Indeed, your child wants you to believe that they will hate you if you confront their hostility and give them consequences. And we fear that our kids will no longer love us if we make them too angry.

But here’s the truth: if you make your child or teen angry, don’t worry that they will no longer love you. That’s the last thing I tell parents to worry about. Here’s why.

There’s a word we use in therapy called ambivalence. Ambivalence is the concept of having conflicting feelings, and it’s common for kids in adolescence to have ambivalence toward their parents. Their ambivalence is that they love you, but at the same time, they hate you. They love you when you’re nice to them. They hate you when you hold them accountable.

Their ambivalence is that they love you, but at the same time, they hate you. They love you when you’re nice to them. They hate you when you hold them accountable.

So as far as kids loving you or hating you, I think you’re going to see a lot of ambivalence from your child. I think parents have to ride that out and accept it as normal during adolescence. In other words, your child can hate you and still love you at the same time.

Adults have ambivalence too. Many of us get angry at our spouses while, at the same time, we love them. We get angry at our children, and we love them too. Think about it, the people we tend to be the angriest towards are the people we love the most! Anger in relationships is normal; we just need to learn how to deal with it. And your hostile child needs to learn how to deal with it.

I explain ambivalence to parents so that they don’t equate their child’s anger and hostility with pure hatred. It’s more than likely just the negative side of the ambivalence they feel. Kids love their parents, even when they’re acting hostile. Unless there’s some abusive situation or neurological or psychological problem, their instinct is to love their parents.

Kids love their parents, even when they’re acting hostile. Unless there’s some abusive situation or neurological or psychological problem, their instinct is to love their parents.

I always tell parents, if you do things for your kids so that they love you, maybe they’ll love you and maybe they won’t. I don’t know. But if you do things and carry yourself in such a way that they respect you, then they’ll want to love you. Kids want to love the people they respect—and they’ll find things to love about you.

Nevertheless, hostility that is allowed to go unchecked can seriously hurt relationships. That is why we need to confront the hostility even if it provokes an angry outburst in the short-run.

Remember, you’re not looking for friendship, love, and affection from your kids. It may be there—and I think these kids love their parents—but it has more to do with getting your child to comply with the rules.

How to Manage Your Child’s Anger and Hostility

Hostile and defiant kids are willing to break things, call you filthy names, and even run away to avoid taking responsibility for their behavior. And parents can’t prevent their child from doing those things if their child is insistent.

And parents can’t prevent their child from doing those things if their child is insistent.

That’s why parents need to focus on those things over which they have control. And parents control—or ought to control—their own home. Parents need to take a stand and enforce the rules with effective consequences if those rules are broken. You might start by saying:

“If you don’t do your homework, you’re going to lose your cell phone until your homework is handed in.”

Now, while some kids will answer you with, “All right, sure, I’ll take care of it,” hostile kids will respond by saying, “It’s none of your business. It’s my grades. Don’t bother me.”

So then you take their phone. If they refuse to hand over the phone, then you say:

“Well, then I’m removing your phone from the phone plan until you comply.”

And then remove them from your phone plan.

Think of all the things over which you have control and exercise your authority over those things. Consistent exercise of that authority over the things you control will eventually get through to your child.

Consistent exercise of that authority over the things you control will eventually get through to your child.

In extreme cases, if your child threatens you, and you fear for your safety, then you may need to consider calling the police. That needs to be an option because you should never feel unsafe in your own home.

Protect the Rest of the Family From Your Hostile Teen

If there are other siblings in your home, have a safety plan for them. Let the kids know ahead of time what to do if their brother gets out of control.

Make the plan the safest, most helpful thing for your other children to do. An example might be that they can go to their rooms and play or read a book. When an argument starts, you can say to the other kids:

“Go to your room and read a book while I deal with Johnny.”

That gets your other kids out of the way. These episodes can be traumatic for younger kids, so you will need to talk with them afterward. But, when Johnny is out of control, the important thing is their safety.

Make the Rules Clear to Your Hostile Child or Teen

Clearly explain the rules to your child or teen, especially if you have not been enforcing them consistently. Make sure they know the rules and the consequences if they break the rules. You can say:

“You’re striking out at me. You’re hostile to me and the rest of the family. When you’re hostile, I will not help you. If you want a ride to school, if you need a ride to practice, if you want to go out, if you want to do something, if you want permission to go to parties or anything, you’re not going to get it. You need to learn how to make requests, not demands.”

By the way, I always counseled parents to give their child a carrot big enough to make them want to change. This might include getting their driver’s permit or having access to electronics, or use of the car. Just remember, the carrot alone is not enough to create changes. You need to use effective consequences as well.

Coach Your Child on How to Cope with His Anger and Hostility

And ask yourself what your child can replace the hostility with if they don’t like what’s going on. How can they learn to behave differently?

How can they learn to behave differently?

With the kids I worked with, I would suggest that they keep a journal and write down their hostile feelings. They were able to take a timeout and write without a consequence. It sounds hokey, and they might not do it the first time, but I’ve found that it works.

By the way, if your child says, “I need a break right now” and goes to their room, they should never be punished for that unless they’re trying to manipulate you to get out of a chore or responsibility.

Remember, a timeout is a coping skill. We hope kids learn to take them on their own. During a timeout, your child unwinds from over–stimulation until they’re calm and composed enough to understand the situation better. It gives them a chance to reconsider his thinking errors and distorted thinking.

Kids get overstimulated, and I believe that contributes to the anger and acting out. When I would work with kids in my office, I would tell them:

“Any time you want to take a break, you just let me know and go sit in the other room. That’s fine with me. But understand, when you come back, we still have to deal with this.”

That’s fine with me. But understand, when you come back, we still have to deal with this.”

I would then say:

“If you act out and are angry here, don’t blame me. I gave you an option to take a break.”

Just giving your child that option also gives them the power to exercise it.

By the way, if your child takes a timeout during homework time, they have to make that time up later on. For example, if they’re supposed to be doing an hour of homework at the kitchen table, and they take a timeout for 15 minutes because something bothers them, they have to make up those 15 minutes later.

In the same way, if your child takes a timeout when they’re doing chores, they have to come back and finish their chores.

Get Professional Help for You and Your Teen

If your kid is hostile, angry, and defiant all the time, you may need some professional help to deal with them. If you take them to a therapist, give the therapist six or eight weeks, and if you don’t see any changes in that amount of time, I would look for someone else.

I think it’s also important to get help with your parenting skills. The bottom line is that you need to learn how to effectively parent a child with angry and hostile behavior patterns. The right techniques are very powerful and can get your child on track and can restore peace to your home.

Hostile kids are hostile to everyone: to you, to his teachers, to the cops. You’ve got two options: (1) your child can go to a counselor for an hour every week in the hopes that they’ll learn some coping skills and apply what they’ve learned at home, and (2) you can get the effective parenting skills you need to help create change where it counts. I recommend both, which is why in my practice, I did both. I met with kids, and I met with parents. And I would teach parents the skills to promote change at home.

Be Businesslike and Firm When Confronting Your Child’s Hostility

Let’s say you want to make these changes, but in the meantime, whenever your child comes into the room, they fill the air with a bad attitude. Keep calm and give them direction. Don’t get dragged into a fight.

Keep calm and give them direction. Don’t get dragged into a fight.

I wouldn’t ask, “What’s wrong?” I wouldn’t ask about their attitude. I would say:

“All right, it’s four o’clock. You need to go to do your homework now, Jessica.”

Kids will walk around with a contemptuous attitude, and it does affect everybody and everything. But in my opinion, you just keep them focused on the task at hand. If they start making negative comments, say:

“Look, why don’t you go to your room until you’re ready to behave like the rest of us.”

Disconnect When Your Child Has an Angry Outburst

The best way to handle an angry outburst is to say what you have to say and then get out of the discussion. I recommend that you say something like:

“I’m not going to talk to you till you calm down.”

Then disconnect. Turn and leave the room. If your adolescent yells at your back or calls you a name as you’re walking out of the room, don’t respond to them. Don’t argue and don’t turn around. Just keep walking.

Don’t argue and don’t turn around. Just keep walking.

If you have to get in your car and drive around the block, then do it as long as there are no small children in the house. But the point is to keep walking. Go to your bedroom and stay there for a few minutes.

The idea is that once they’re in that angry, agitated state, they’re thinking that you’re the enemy, that you don’t understand, and they’re blaming you. They see themselves as the victim, and there’s nothing you can do at that moment to change them. They’re going to think what they’re going to think.

As soon as you extract yourself from the argument, there’s nothing to yell about. Your child may walk around the house shouting for a few more minutes, but they usually quiet down if you don’t respond to it.

Don’t try to talk your child out of his anger. Don’t try to reason with them. When you try to reason, you give your child a feeling of false power and more of a sense that they’re in control, and you’re not.

Related content: Angry Kids: 7 Things Not To Do When Your Child Is Angry

What To Do If You Fear for Your Safety

Parents need to understand that when you disconnect, in some cases, a teen might escalate to the point of being destructive, threatening, and even violent.

In my opinion, if you feel threatened and fear for your safety or the safety of your family, then it’s time to consider calling the police.

Get the police to help you because if your child is behaving this way, they’re out of control. When you call the police, say:

“I don’t feel safe here. My son is out of control.”

No one should feel threatened in their own home. There is no excuse for abuse, and you should not tolerate abuse of any kind.

Your Child and His Feelings

In my experience, the more you ask your child about his feelings, the more your child will simply state his case. Indeed, they’ll scream their case if you let them.

Keep the focus on your child’s behavior. The behavior needs to change before anything. There will be time to discuss feelings once his behavior improves.

The behavior needs to change before anything. There will be time to discuss feelings once his behavior improves.

I tell parents, your child won’t feel their way to better behavior, but they can behave their way to better feelings.

The truth is, some kids want to appear out of control whether or not they are. Don’t forget, acting–out people get more power by looking like they’re losing control. They control you by acting out of control.

Don’t Accept the Hostile Behavior

If you think you have to accept this type of hostile, defiant, or angry attitude to be loved by your child, that’s called co-dependency. In a co-dependent relationship, you have to fulfill a certain role to be loved. That’s one of its main definitions. The co-dependent spouse of an alcoholic reasons, “You’ll love me as long as I make excuses for your alcoholism.”

With parents of a defiant child, it’s “You’ll love me as long as I put up with your garbage attitude and leave you alone. ”

”

Parents should try to maintain their dignity and self–respect. Remember, as I said before, kids want to love the people they respect. And they’ll find things to love about you when they respect you. But they won’t respect you if you give in to and accept their hostile behavior.

Why a child is often angry and psycho: how to help an aggressive child cope with aggression and hysteria 13 years of experience working with teenagers.

Being angry is normal

The emotion of anger is innate. American psychologist Paul Ekman notes that this is one of the five basic emotions. Among them are disgust, fear, happiness and sadness.

Although it is customary to demonize anger, it is actually a useful emotion. It is accompanied by a physiological reaction - an increase in adrenaline, cortisol, pressure and heart rate, a rush of blood to the muscles. Anger is needed to make a person stronger and more fearless in the moment, to help him defend himself from "enemies". Anger tells us what we don't like and gives us the energy to change the situation.

Anger tells us what we don't like and gives us the energy to change the situation.

The perception and expression of anger is a social pattern. Children learn this during their upbringing in the family, under the influence of culture and experience. It is important to learn how to properly respond to children's anger and explain to the child how to express anger in an environmentally friendly way.

If you broadcast to a child that he is “not loved” when he is angry, and refuse to recognize his right to be angry, this can result in problems with aggression and recognition of his own emotions. Children who have had to suppress anger often do not understand, as adults, what they like and what they don't like, how they can and cannot be treated.

How anger attacks manifest themselves in children

Depending on age, children express aggression in different ways:

- under 1.5 years: crying, biting, throwing toys;

- 1.

5–5 years: possible outbursts of rage, physical attack on a peer, screaming, crying, stamping feet, wallowing on the floor, running away, name-calling;

5–5 years: possible outbursts of rage, physical attack on a peer, screaming, crying, stamping feet, wallowing on the floor, running away, name-calling; - 5–7 years: pugnacity, tantrums, insults, ignoring, property damage;

- primary school age: teasing, "light" attacks (push, take backpack, throw something), revenge planning, damage to property, ignoring requests, tears;

- senior school age: physical and verbal aggression, transfer of aggression to oneself.

No matter how angry the child is, it is important to understand the causes of what is happening, resolve the conflict here and now and prevent aggression in the future.

Why the child is angry

Causes of child aggression are one way or another connected with the dissatisfaction of basic needs. Psychologists distinguish five needs of the child: respect, a sense of self-worth, acceptance, connection with others and security.

So, if he is angry because he was not bought the desired toy, the need may not be the toy itself, but the feeling of self-worth. Probably, his opinion was not taken into account and they chose another, uninteresting and ugly. In the child’s subconscious, the following could be fixed: “I’m not good enough for that toy”, “Mom and dad don’t love me enough to buy that toy”, “Mom and dad don’t care about my desires”, “They don’t hear me, they don’t appreciate me, they don’t respect me , I am bad".

Probably, his opinion was not taken into account and they chose another, uninteresting and ugly. In the child’s subconscious, the following could be fixed: “I’m not good enough for that toy”, “Mom and dad don’t love me enough to buy that toy”, “Mom and dad don’t care about my desires”, “They don’t hear me, they don’t appreciate me, they don’t respect me , I am bad".

Psychologists identify several possible causes of child aggression:

Reaction to frustration. The child is trying to overcome an obstacle on the way to satisfying his needs.

Last resort. The child has tried all other ways, has not satisfied his need and is feeling helpless.

"Learned" behavior. The child freaks out and gets angry because he copies the aggressive behavior of significant adults, literary and film characters, because he sees that their actions led to a result.

How to help deal with anger

If your child is aggressive here and now, act like this:

Remember that you are an adult. You already have the skill to keep your composure. The child is just learning this - he needs help. Do not get infected and do not get turned on, so you reinforce the pattern of responding to anger with anger.

You already have the skill to keep your composure. The child is just learning this - he needs help. Do not get infected and do not get turned on, so you reinforce the pattern of responding to anger with anger.

Give your child a big hug. Hugs will help the attack of aggression come to naught. Tactile contact is a manifestation of love and protection that an aggressive child needs. If the child screams and refuses, continue to calmly offer: “Let me hug you,” “Let me pity you.”

Validate feelings. Say the state of the child: “You are angry because…”, “You are now angry because…”, “I understand your anger”. Explain that it is normal to experience negative emotions.

Don't be ashamed of what's happening. If a child has an attack of anger in a public place, parents often feel ashamed in front of others. Parents begin to shush at the child: “Shame on you, everyone is watching” and think more about the opinions of others than about the state of the child at that moment. Try to ignore public opinion and concentrate on the fact that the child is now ill, he needs your protection and help.

Try to ignore public opinion and concentrate on the fact that the child is now ill, he needs your protection and help.

Talk. When the child calms down, have a conversation: discuss the situation, his feelings, your feelings, the problem, what could be done, what you propose to do next time. The discussion should take place in private. Make sure you are at the level of the child - for example, squat down, and do not speak from the height of your height.

How to help prevent violent behavior

Here are some preventive measures:

Show love. The more care and contact a child is surrounded by, the less he has to resort to negative emotions to attract attention.

Never raise your hand. Psychologists agree that even "frivolous" physical punishment (for example, a slap on the bottom) can injure the child's psyche and subsequently lead not only to outbursts of aggression, but also to the inability to defend boundaries, fear of others and low self-esteem.

Meet your own requirements . If a mother tries to explain the inadmissibility of aggression, while she screams at the same time, the words diverge from the deed. If dad says that using obscene words is bad, but he swears, the wrong picture is formed in the child’s head again.

Find where to vent your energy. It is useful to sign up for sports training - sports help get rid of excessive aggression and put things in order in the head.

Use mental exercises. Regularly go to a deserted place in nature to shout loudly into the void with your child - good for the whole family. At home, you can tear paper, beat a pear, beat a pillow, play with sand, water - these are eco-friendly ways to express anger.

Together with psychologist Elena Petrusenko, we figure out how to cope with an angry tantrum and prevent future aggression in a child.

Stop being angry.

.. at your parents

.. at your parents 69013

Know yourself Older generation

Main ideas

- They are imperfect: parents are ordinary people who gave us as much love as they could.

- We don't have to fulfill all of their expectations... just as they won't fulfill all of our desires.

- By accepting our parents, we get the opportunity to live in peace with ourselves.

It would seem that we have grown up a long time ago, built an adult life and even became parents ourselves. But have we managed to fully deal with long-standing childhood grievances that sometimes so violate our relationships with the people closest to us?

“I have a wonderful mother,” says 37-year-old Yuliya. She loves me, she worries about making me happy. And I don’t understand why I am offended, and sometimes really hurt, even by trifling criticism on her part. Seems like a common concern: "straighten your back, you're slouching!" or “It’s time for you to cut your hair!” — and I can't resist. I break down, yell at her ... I want to be left alone, given the opportunity to live as I want. But as a result, it turns out that it is I who offend her and because of this I constantly feel guilty ... "0003

I break down, yell at her ... I want to be left alone, given the opportunity to live as I want. But as a result, it turns out that it is I who offend her and because of this I constantly feel guilty ... "0003

Any, even the most ordinary gesture, casual look or word of parents has a special meaning for us. And many are familiar with resentment, disappointment, anger ... These feelings are the stronger, the deeper our affection and love.

Dual feelings

“Pain is the other side of love,” explains family psychotherapist Varvara Sidorova. - And in relations with parents, this duality of feelings manifests itself especially strongly. No matter how old we are, it is from them that we expect attention, support, we hope that they will accept us as we are.”

For the first time, we are “disappointed” with our parents very early. Already at the age of 3-4, each child begins an unconscious "count" of what adults did not give him, what they missed, what they could not. Child psychoanalysts even believe that the child pays more attention to what (as it seems to him) he was deprived of than to what was given to him. Why do we fixate on what we lack?

Why do we fixate on what we lack?

“It's about existential doubt,” says family therapist Nicole Prieur. - All children are unconsciously looking for an answer to the question: is my existence important to you, mom and dad? After all, in order to grow, you need to know whether you can trust your parents, whether you can rely on them.

This question arises especially sharply at every significant event in the life of a family: the birth of a brother or sister, the divorce of parents, the appearance of a stepfather or stepmother... Nicole Prieur emphasizes. “They will never be able to meet absolutely all of our needs.”

Hence this unconscious resentment: they did not give us what we desired so much. “And this feeling affects the rest of my life,” explains family psychotherapist Inna Khamitova. “Having not received love, care, affection, we can feel our lack in the world, self-doubt and, most likely, we will blame our parents for this and try to change them.”

But there are those who say that there is no bitterness in their relationship with their parents, only joy and warmth of communication. What is the secret of such families?

What is the secret of such families?

“If parents have managed to give the child a sense of security in the world, a clear understanding of the boundaries — what is good, what is bad, what is possible, what is impossible, what is already within his power and what is not, and let him go to an independent life, then the claims and insults from he is gone,” says Inna Khamitova. - And their relationship, as they grow older, will gradually develop into partnership, friendship. This does not mean that such parents do not make mistakes at all (this does not happen, no one is perfect), it is important that in such a family the general vector of relations is positive, and parents see an independent person in the child, and not their continuation.

“My father doesn't have to admire only me”

“I've always been proud of my dad: smart, talented, charming,” says 43-year-old Kseniya. - He is a mathematician, so in high school, my parents transferred me to a boarding school for physics and mathematics. I left to study, then easily entered the university, defended my PhD, got married ... I “dedicated” every height I took in my life to my dad: I really hoped that he would be proud of me.

I left to study, then easily entered the university, defended my PhD, got married ... I “dedicated” every height I took in my life to my dad: I really hoped that he would be proud of me.

All these years we saw each other infrequently, and two years ago my husband and children decided to return to my hometown. Parents by this time retired, moved to live in the country. And we became very good friends with our neighbors - a young couple, graduate students from my father's institute.

And all of a sudden I started catching myself... that it just pisses me off, how dad smiles at this neighbor Katya, jokes with her, compliments her. I was tormented by annoyance, irritation, anger ... I did not understand where such feelings came from. Is it possible that I, a mother of two children, an adult woman, was seized by blind childish jealousy? It was terribly stupid, but I felt betrayed. It's not my fault that I left home so early! Mom and dad themselves sent me to study, and now they are friends with Vanya and Katya, they drink tea with them in the evenings - with them, not with me . ..

..

I must have been chewing on my grievances for a whole month. Until one day she asked herself: do you want to remain an offended little girl who didn’t get sweets at the holiday? This image somehow calmed me down. My father doesn't have to admire me exclusively. I myself have something to praise myself for.

Lay down your arms and stop conflicts

“We have to defend our positions,” says 42-year-old Inna. - Mother was not very interested in me, now I see the same indifference to my daughter. Why should I endure this? Unleashing her anger on her parents, Inna tries to achieve her goal, to change her imperfect mother.

Varvara Sidorova says that in such cases she answers the client: “You are trying to get love from your mother, which she did not give you in your 30 (40, 50) years. Why do you think it will suddenly happen now? It is important for you to learn to do without your mother's love.

Parents, like all of us, find it difficult to admit their imperfection, Inna Khamitova agrees: “It is unlikely that in response to the claims of their adult child, a mother or father will say: I understand everything, forgive me. After all, by admitting guilt, they thereby devalue their lives, and by justifying themselves, they can maintain self-esteem.

After all, by admitting guilt, they thereby devalue their lives, and by justifying themselves, they can maintain self-esteem.

Does this mean that mutual understanding will never be achieved? Not at all, say our experts. “The only way is to lay down your arms, stop fighting and accept the fact that your parents are not perfect,” says Inna Khamitova. - That a mother or father is not an omnipotent deity, but not villains either, but ordinary people with their own shortcomings and problems. They gave us as much love as they could. Mother worked hard and didn't tell bedtime stories? Did you think that the main thing is to feed-shoe-clothe? Well, it means that she had such a love language! Parents themselves were inexperienced (as we are now) and lived as best they could. Nobody is to blame for anything."

We also need to accept that the parental family will never be able to give us absolutely everything we need: happiness, satisfaction, well-being. “Growing up, we are looking for other people who will satisfy these needs - friends, partners, colleagues, like-minded people,” emphasizes Varvara Sidorova. “We must come to the conclusion that I can give myself what I lack.”

“We must come to the conclusion that I can give myself what I lack.”

The world doesn't owe us anything

But why is it so difficult to accept this thought? “Because it’s much easier to blame your parents for their mistakes than to take responsibility for your life,” explains Varvara Sidorova. On the way to adulthood, we go through three stages.

The first is the childish attitude, where we live in the passive expectation that we will get something from others.

The second is the position of a teenager who makes claims to his parents, settles scores, demands what is due to him. And many get stuck at this stage. Remaining dependent on others for years, they demand from friends and loved ones what their parents did not give them. And they are wrong, because the partner will never be able to love them like a father, a beloved cannot be exactly the same caring as a mother. These are different people and different relationships.

“A person who is dependent on others has nothing to rely on inside himself, he does not feel a core in himself, does not feel his identity, selfhood,” says Inna Khamitova. “Dependence on the opinions and actions of other people speaks of the infantility of a person.”

“Dependence on the opinions and actions of other people speaks of the infantility of a person.”

In order to grow, we have to admit that we will never be able to "get the bills."

The third stage on the path of growing up is to accept the fact that what you haven’t received will never be received, to stop being offended by your parents and to say to yourself: “Well, no matter what I do, I won’t see this affectionate look, don’t feel the support and recognition that I dreamed of. If we manage to manage our feelings at this moment, we will feel real liberation.

Find your way

But even this is not enough to really become an adult. The unconscious not only retained the memory of grievances, but also absorbed parental expectations, these “impossible missions”, whether they were spoken out loud or not: “Mom could not become a pianist, now I must make her dream come true!”, “I must be in everything the first to make dad proud of me!

“Rare parents do not project their expectations onto their child, assuming that they know what is best for him,” confirms Irina Khamitova. But this is, of course, an illusion. Each person must find his own way."

But this is, of course, an illusion. Each person must find his own way."

We grow up under the burden of these parental expectations, and even if we protest against them in adolescence, we still lack the strength to free ourselves from them. And only by the age of 25–30 do we feel that it will not work to pass all the parental “exams” for five. So, we will not fulfill their desires, we will disobey them. It's hard to admit it and allow yourself to move on. But this is the last stage on the path that allows you to become yourself. Those who make their own decisions and take responsibility for their lives.

“For those who grew up in Russia, this is especially difficult,” says Varvara Sidorova. “Our children often receive two conflicting messages: “you are the center of the world” and “you are full of flaws.” And because I, the almighty, do not reach the required heights, a strong sense of guilt arises.

But our parents did not bring us into this world to meet their expectations. If, as adults, we still continue to prove something to them, it means that we are not living our own life, we are not achieving our goals. “It is worth listening to your convictions,” advises Inna Khamitova. “I don’t trust people—isn’t it because my father said so?” I'm afraid of men who "only need one thing" - aren't these my mother's words? It is important to understand whose voices are in our heads, what we ourselves want, where our path is.”

If, as adults, we still continue to prove something to them, it means that we are not living our own life, we are not achieving our goals. “It is worth listening to your convictions,” advises Inna Khamitova. “I don’t trust people—isn’t it because my father said so?” I'm afraid of men who "only need one thing" - aren't these my mother's words? It is important to understand whose voices are in our heads, what we ourselves want, where our path is.”

And make no mistake: if we act against our parents just to prove them wrong, we are still dependent on them. This is the same relationship, only with the opposite sign. “Only when there is no protest, resentment, anger, guilt in the soul, then we were able to separate from our parents and really become adults,” says Inna Khamitova.

Find out family history

“Interest in family history helps to understand and, therefore, forgive one's parents,” says Inna Khamitova. - It is worth finding out: in what conditions did the mother grow up? How was she brought up, how was she treated in childhood? It's not about "turning the arrows" on grandparents, but about justifying the mother. It is important to see and understand the whole family context. Think: why such women, such men, such marriages were in the family?

It is important to see and understand the whole family context. Think: why such women, such men, such marriages were in the family?

The next step is to look at family history in the context of the country's history. Maybe the ancestors were dispossessed or exiled, and all their strength was spent only to survive? From here, for example, rigidity and severity could arise, which were passed on to the next generations. Or maybe when the mother was born, the grandmother received a funeral for her grandfather - and the girl lacked attention, joy and warmth.

When we learn and analyze such details, the picture of life acquires volume, ambiguity. And black-and-white assessments are no longer possible: bad - good, good - evil. We will see difficult people, with their own difficult fate, whom it is pointless to blame.”

Accept their choice

Yet we have received much from them and feel we owe them. To what extent can we afford to be disloyal? “It takes time to admit: this person is not perfect - but I love him,” notes Varvara Sidorova.![]() - And it is even more difficult to accept that we have both love and anger in us at the same time (everyone, of course, in different proportions). It’s easier for us to see only one color: I love him or I hate him.

- And it is even more difficult to accept that we have both love and anger in us at the same time (everyone, of course, in different proportions). It’s easier for us to see only one color: I love him or I hate him.

When we discover the vulnerability of our parents, we often get frightened and feel more guilty. Sometimes adult children reach a dead end trying to save their parents - to get their mother out of depression, to cure their alcoholic father ... even against their wishes. And they suffer when none of this works.

“You need to help when parents are ready to accept this help,” says Varvara Sidorova. - After all, not only I am an adult independent person, but my mother is an adult independent person. And has the right to make choices that I don't like. Including, no matter how scary it sounds, and destroy yourself. Love is not omnipotent: we cannot “drive them into happiness” by force. Respecting your parents means accepting their conscious and unconscious choices.