Loss of memory due to trauma

Trauma and Memory Loss - How Trauma Affects the Brain and Memory

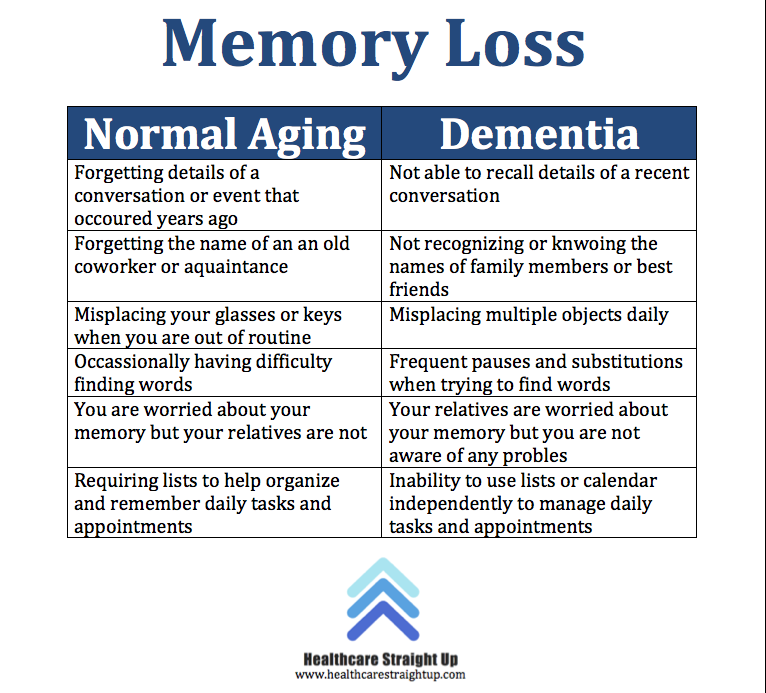

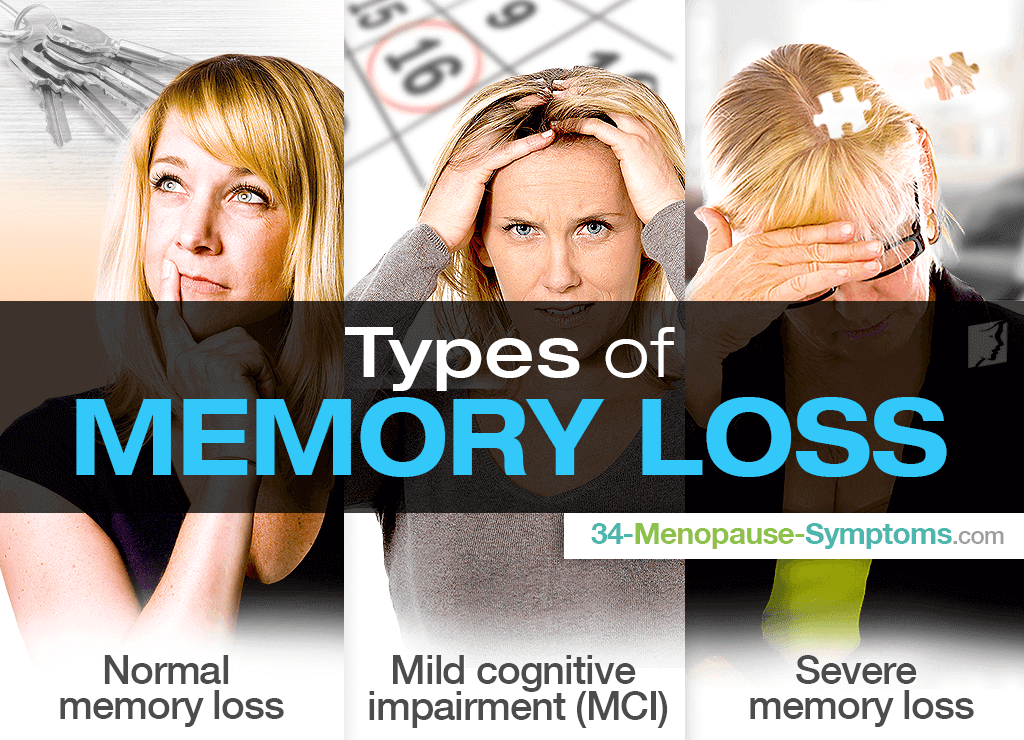

Memory loss is a frustrating and sometimes scary experience, especially if the memory loss is caused by a traumatic event. Research shows that there is a definite relationship between occurrences of emotional, psychological or physical trauma and memory. Some of this memory loss may be a temporary way to help you cope with the trauma, and some of it may be permanent due to a severe brain injury or disturbing psychological trauma. Knowing how trauma can affect your memory can guide you in choosing an appropriate treatment to help you cope with trauma and heal your memory problems.

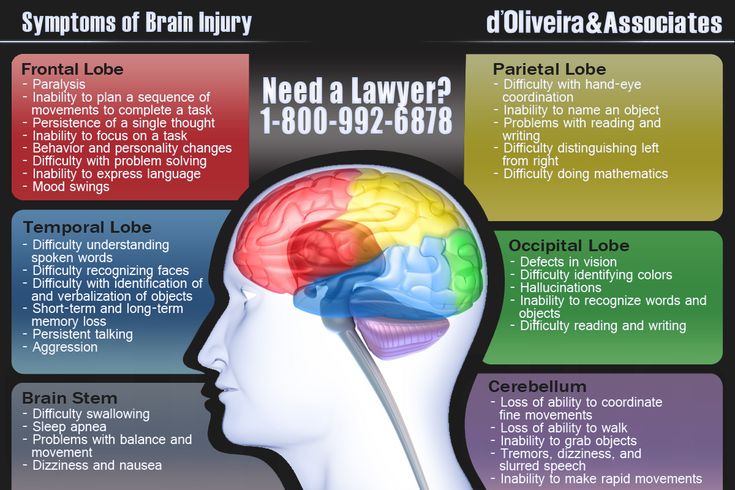

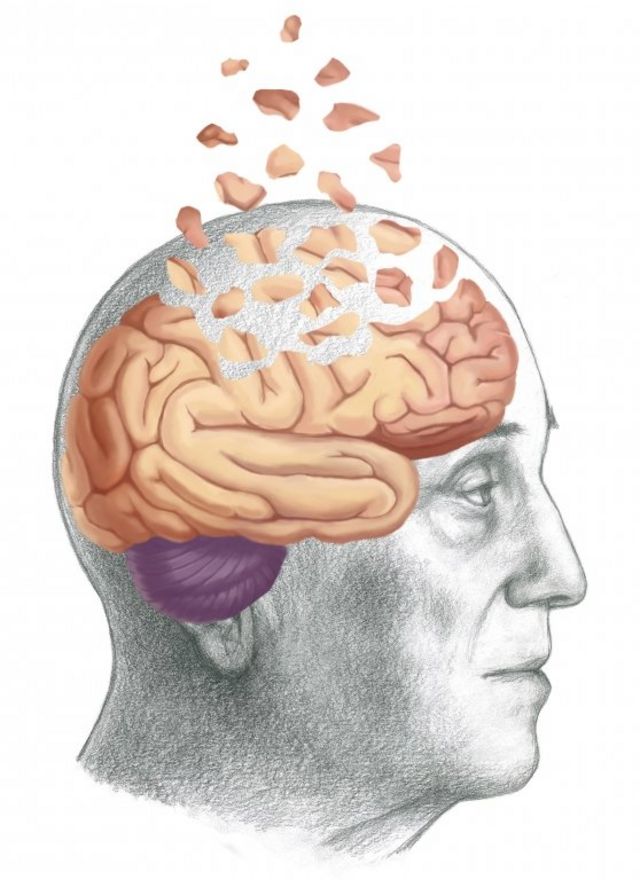

How Trauma Affects the Brain

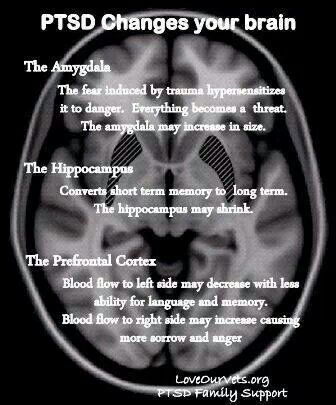

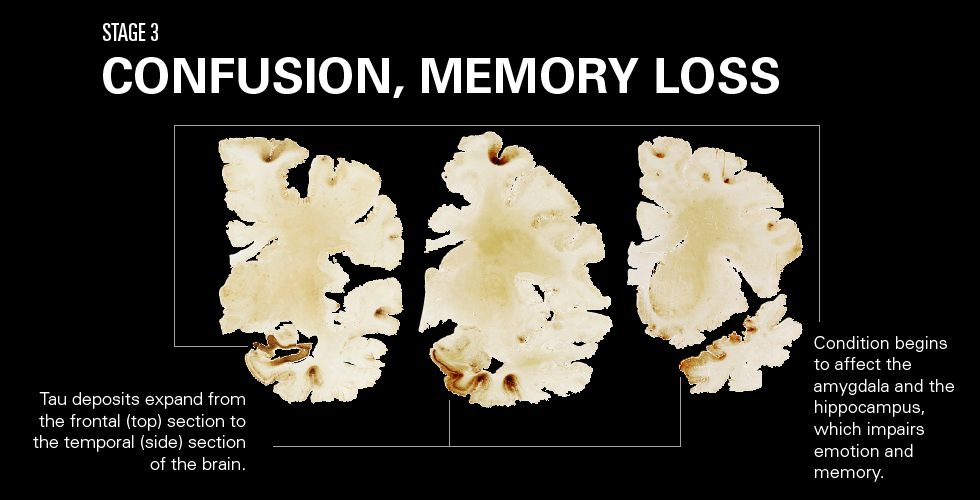

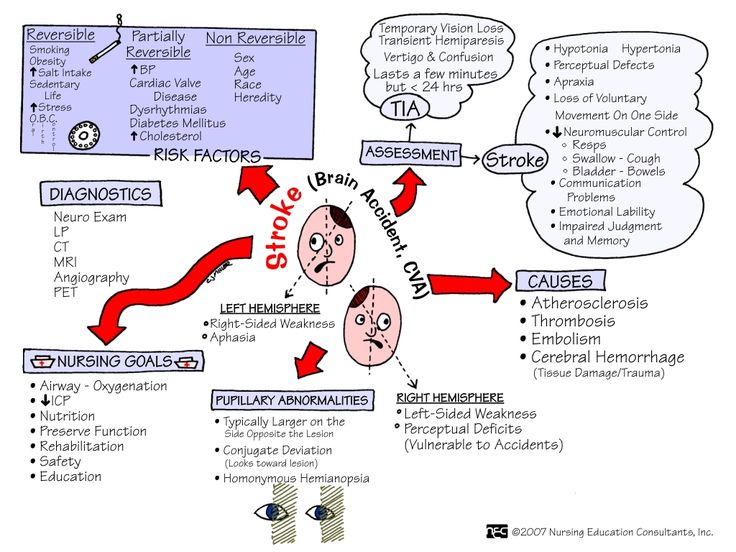

A traumatic incident can cause a great deal of stress in both the short term and the long term. That stress response can have an impact on different areas of the brain, such as the hippocampus, amygdala and prefrontal cortex. In fact, those areas of the brain can change in shape and volume, and experience diminished function.

Not coincidentally, these are areas of the brain that are strongly associated with memory function. The prefrontal cortex helps process working memory, the information that we need to remember on an everyday basis. The hippocampus is also a major memory center in the brain. The left hippocampus focuses on memorizing facts and recognition, while the right hippocampus is associated with spatial memory. The hippocampus also gives us a way to learn by comparing past memories with present experiences. And the amygdala processes fear-based memories; if you ever burned your hand on a stove once, you remember not to touch the hot surface again because the memory is processed and stored by the amygdala. The amygdala is also believed to help with the formation of long-term memory. Trauma-based memory loss, therefore, can easily occur when the trauma creates stress that negatively affects the brain.

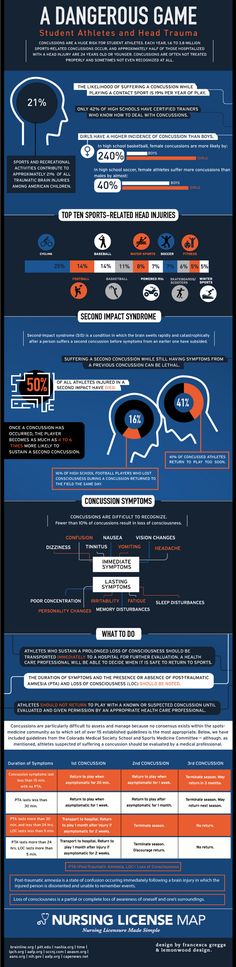

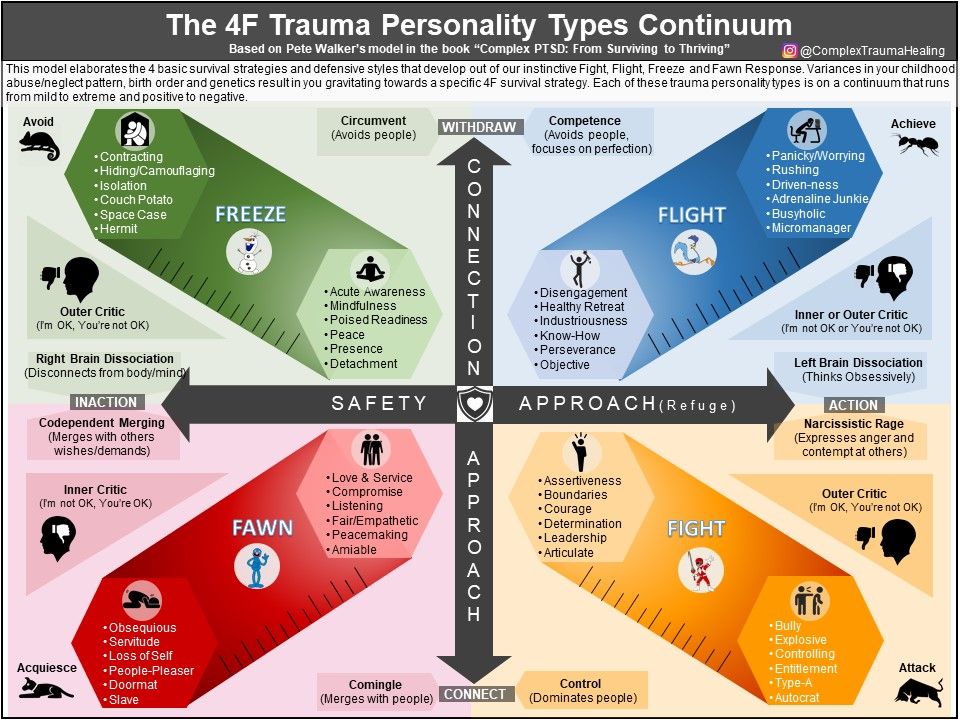

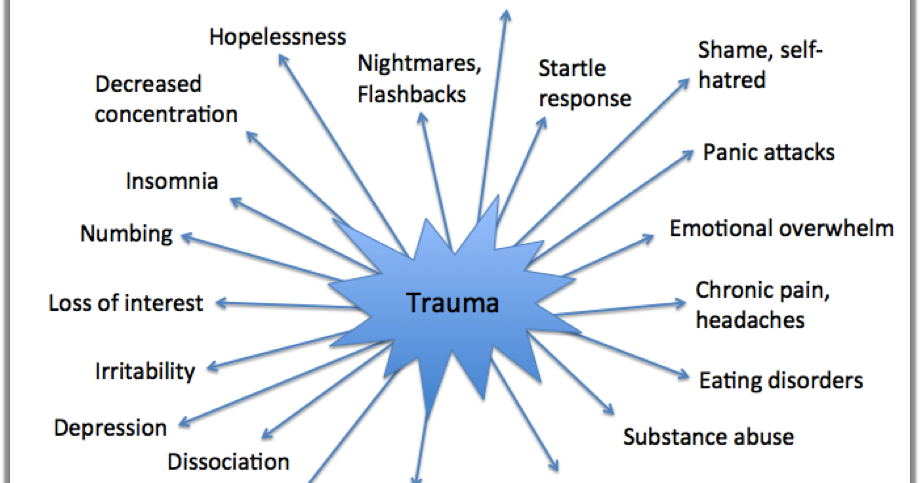

A traumatic event can be so intense that it can spark posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This psychiatric condition has long been associated with war-related experiences, but it can also be triggered by various events including accidents, attacks and natural disasters. There are three different kinds of PTSD: acute (symptoms end in three months or less), chronic (symptoms continue for more than three months) and delayed-onset (where symptoms don’t present themselves until well after the traumatic event has occurred). In addition to memory loss, people with PTSD may experience angry outbursts, irrational behavior, detachment from friends and family and feelings of guilt or shame, among other symptoms. PTSD memory loss can add to the stress someone experiences and may intensify certain symptoms even more.

This psychiatric condition has long been associated with war-related experiences, but it can also be triggered by various events including accidents, attacks and natural disasters. There are three different kinds of PTSD: acute (symptoms end in three months or less), chronic (symptoms continue for more than three months) and delayed-onset (where symptoms don’t present themselves until well after the traumatic event has occurred). In addition to memory loss, people with PTSD may experience angry outbursts, irrational behavior, detachment from friends and family and feelings of guilt or shame, among other symptoms. PTSD memory loss can add to the stress someone experiences and may intensify certain symptoms even more.

When it comes to trauma and memory loss, there are different types of trauma that can cause temporary or permanent problems.

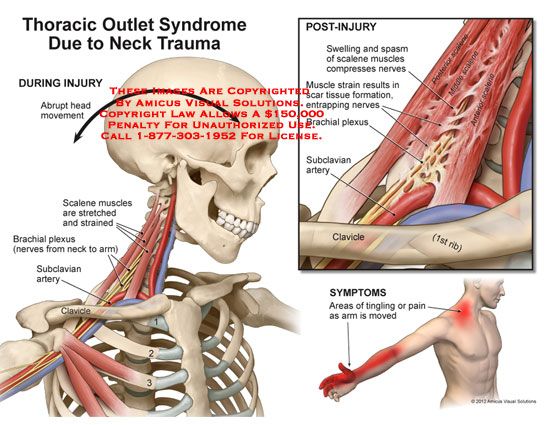

Physical Trauma and Memory Loss

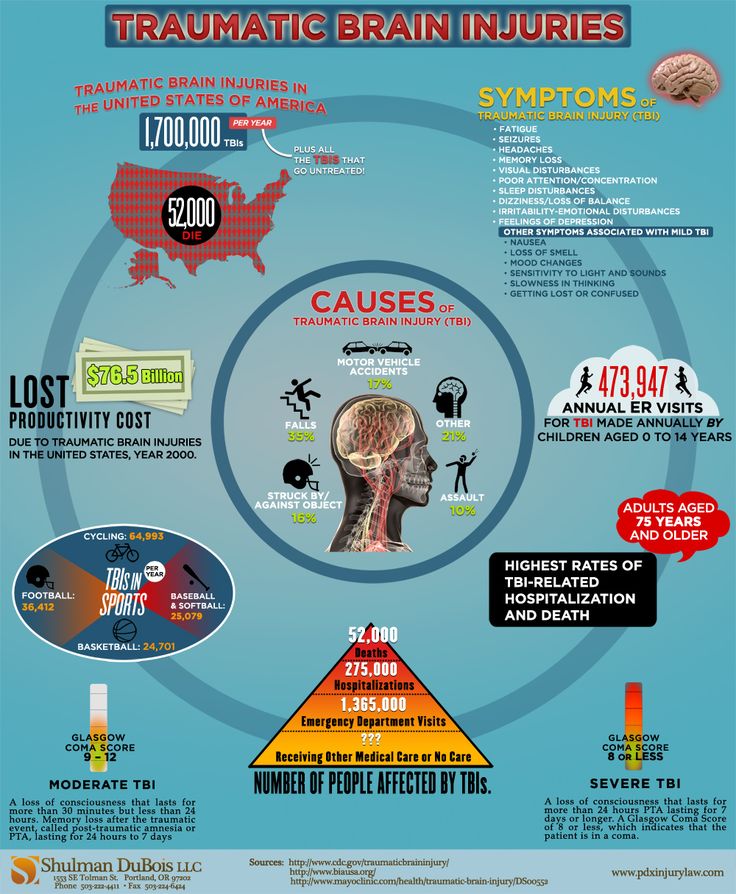

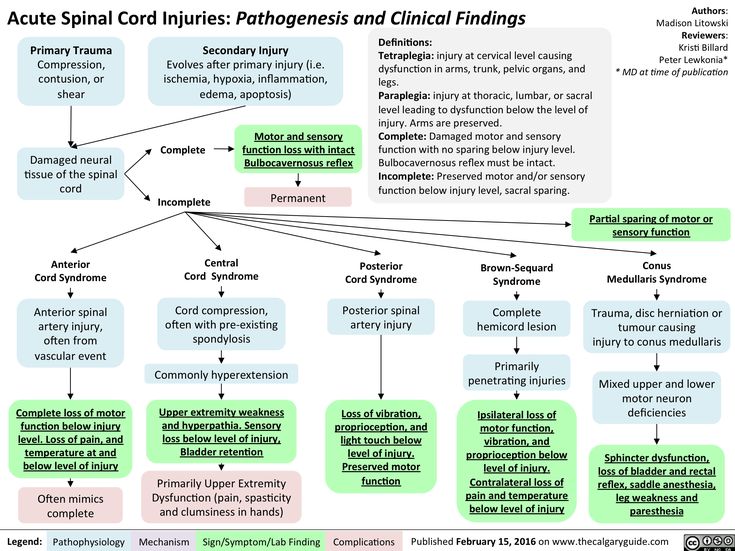

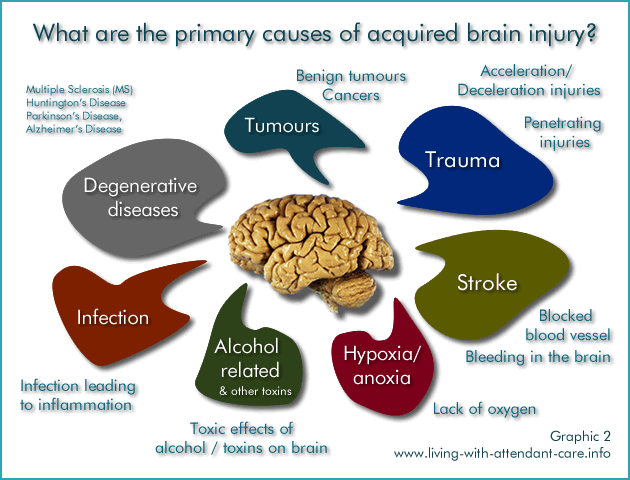

Physical trauma can greatly affect your memory, especially if brain damage occurs as a result of the injury. Physical trauma such as a head injury or stroke can damage the brain and impair a person’s ability to process information and store information, the main functions of memory.

Physical trauma such as a head injury or stroke can damage the brain and impair a person’s ability to process information and store information, the main functions of memory.

Another form of brain damage that directly affects memory is Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome, which is a consequence of chronic alcohol abuse. Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome is a combination of two disorders: Wernicke’s Disorder, in which poor nutrition damages the nerves in both the central and peripheral nervous system, and Korsakoff’s Syndrome, which impairs memory, problem-solving skills and learning abilities. Severe injuries and physical trauma can also produce post-traumatic stress disorder, which can cause temporary memory loss to help a person cope with the traumatic event that caused the injury.

In the case of physical trauma, the length of memory loss depends on the severity of the injury.

Emotional or Psychological Trauma and Memory Loss

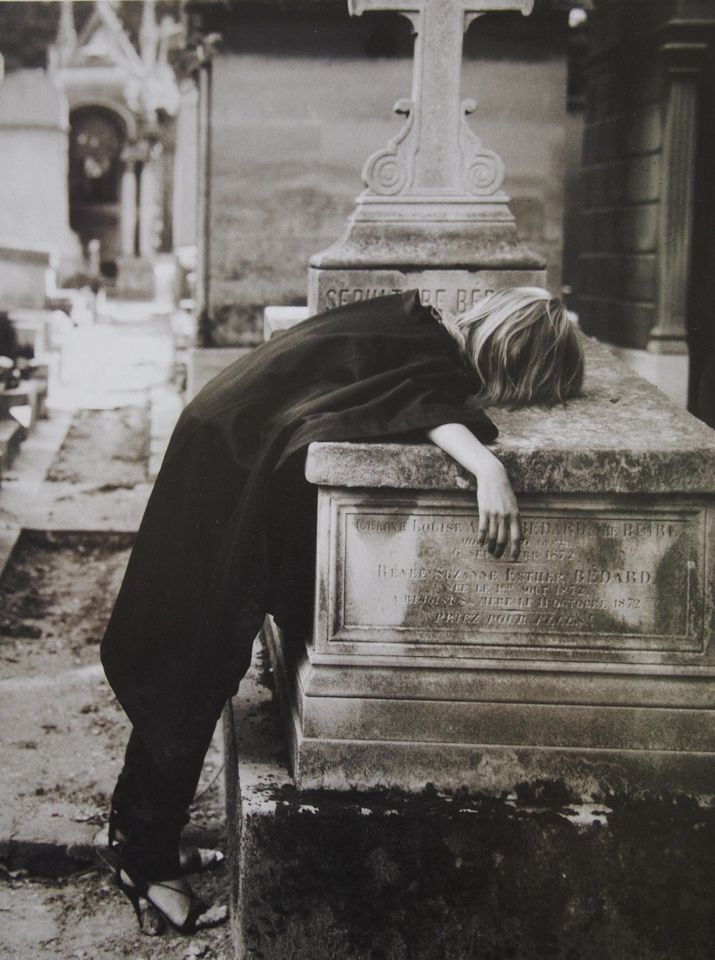

Emotional or psychological trauma can also affect your memory. Memory loss is a natural survival skill and defense mechanism humans develop to protect themselves from psychological damage. Violence, sexual abuse and other emotionally traumatic events can lead to dissociative amnesia, which helps a person cope by allowing them to temporarily forget details of the event. With this type of memory loss, which is also called psychogenic amnesia or functional amnesia, a person will often suppress memories of a traumatic event until they are ready to handle them, which may never occur. This situation-specific memory loss helps block out the traumatic event, but another type of dissociative amnesia, called global amnesia, can cause a person to forget who they are for a brief period of time; they can also experience confusion or depression. Dissociative amnesia can range from mild to severe, and it can lead to dysfunction in relationships and the daily activities associated with normal life.

Memory loss is a natural survival skill and defense mechanism humans develop to protect themselves from psychological damage. Violence, sexual abuse and other emotionally traumatic events can lead to dissociative amnesia, which helps a person cope by allowing them to temporarily forget details of the event. With this type of memory loss, which is also called psychogenic amnesia or functional amnesia, a person will often suppress memories of a traumatic event until they are ready to handle them, which may never occur. This situation-specific memory loss helps block out the traumatic event, but another type of dissociative amnesia, called global amnesia, can cause a person to forget who they are for a brief period of time; they can also experience confusion or depression. Dissociative amnesia can range from mild to severe, and it can lead to dysfunction in relationships and the daily activities associated with normal life.

Emotional or psychological trauma can also lead to posttraumatic stress disorder, which can manifest itself in different ways including flashbacks of the event and intrusive, unwanted thoughts about the trauma. Repressed memories and PTSD are also common. Without treatment, these repressed memories may resurface at any time with a trigger event and if they are revisited over and over, the brain continues to experience the trauma anew each time.

Repressed memories and PTSD are also common. Without treatment, these repressed memories may resurface at any time with a trigger event and if they are revisited over and over, the brain continues to experience the trauma anew each time.

Healing from Trauma-Induced Memory Loss

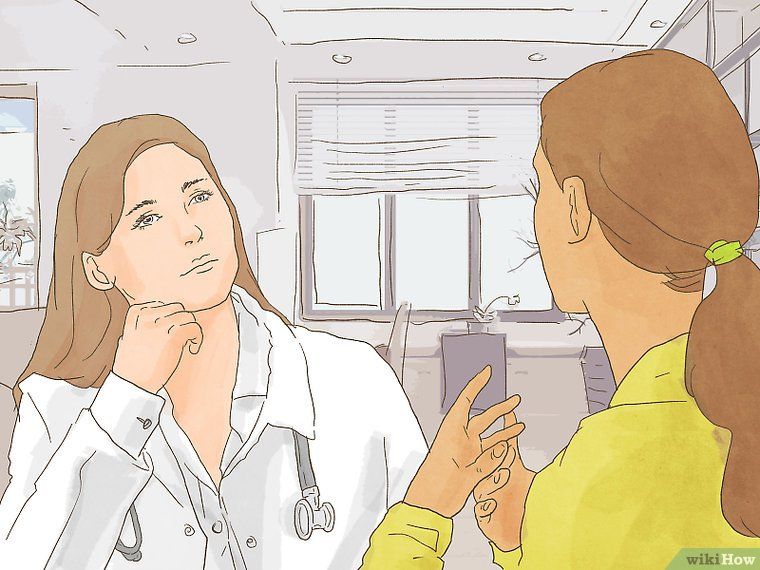

Recovering from a traumatic experience can take days, weeks or even months. Memory loss can come back suddenly, but the underlying traumatic cause must be addressed for authentic healing. Everyone heals at their own pace, but if several months have gone by and your symptoms have not gotten better, then it may be time to seek professional help. It’s also a good idea to seek professional help if you:

* Have trouble functioning at home or work.

* Suffer from severe fear, anxiety or depression.

* Are experiencing terrifying memories, nightmares or flashbacks.

* Are emotionally numb and disconnected from others.

* Are avoiding things that remind you of the trauma.

* Are using alcohol or drugs to feel better.

If you fall into any of the categories above, then contact a trauma specialist today. A certified therapist can help you process the traumatic event and finally start healing your emotional trauma. You can also seek help with a center qualified in trauma treatment, where individualized plans with a variety of modalities can be employed to address your mental, emotional, physical and spiritual needs.

Under the care of a treatment facility, you’ll be able to work with a trauma specialist to process your trauma-related feelings and memories, stop the “fight or flight” response, learn how to control your emotions and rebuild your ability to trust other people. All of this will be done through a series of therapy sessions combined with emotional trauma treatments. Some of these treatments might include cognitive behavioral therapy, somatic experiencing and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR). Cognitive behavioral therapy instills valuable coping mechanisms that can be used in times of stress. Somatic experiencing focuses on the body’s response to stress, as well as the brain’s response, to help unstick the traumatic event. And EMDR helps patients gain control over memories that are unpleasant or unwanted. In certain cases where someone also exhibits signs of depression or an anxiety disorder, antidepressant medication may be recommended as well.

Somatic experiencing focuses on the body’s response to stress, as well as the brain’s response, to help unstick the traumatic event. And EMDR helps patients gain control over memories that are unpleasant or unwanted. In certain cases where someone also exhibits signs of depression or an anxiety disorder, antidepressant medication may be recommended as well.

Patients who have suffered memory loss due to physical trauma can sometimes benefit from surgery. After surgery, therapy is needed to help them recover their lost memories. Patients who suffer memory loss due to Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome should seek treatment right away at an alcohol rehab, where their substance abuse issues can be properly addressed.

If you are experiencing co-occurring PTSD and substance use disorder, it’s critical to seek treatment with a reputable dual-diagnosis facility. Instead of just treating one of the disorders, dual-diagnosis centers address both concerns equally. If your trauma has sparked a drug or alcohol addiction, you can’t separate the two—they are both enmeshed with each other and need to be worked on simultaneously. Both of the disorders can seriously and negatively affect your mind, body and spirit, so it can be helpful for your recovery to take part in complementary therapies such as yoga and tai chi that encourage positive goal-setting, expressiveness and a focus on whole-person health. Combined with therapy and medical treatments, this makes for a well-rounded program for healing.

Both of the disorders can seriously and negatively affect your mind, body and spirit, so it can be helpful for your recovery to take part in complementary therapies such as yoga and tai chi that encourage positive goal-setting, expressiveness and a focus on whole-person health. Combined with therapy and medical treatments, this makes for a well-rounded program for healing.

Anyone who’s been through a traumatic experience knows that psychological, emotional and physical trauma hurt deeply. Start the journey to healing and find a way to stop the pain by calling a treatment facility today.

About the author

Post-traumatic stress disorder and declarative memory functioning: a review

1. American Psychiatrie Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994 [Google Scholar]

2. Bremner JD., Scott TM., Delaney RC., et al. Deficits in short-term memory in post-traumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1015–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1015–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Golier J., Yehuda R., Cornblatt B., et al. Sustained attention in combat related posttraumatic stress disorder, integr Physiol Behav Sci. 1997;32:52–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Yehuda R., Keefe RS., Harvey PD., et al. Learning and memory in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:137–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Uddo M., Vasterling JJ., Brailey K., et al. Memory and attention in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 1993;15:43–52. [Google Scholar]

6. Gilbertson MW., Gurvits TV., Lasko NB., et al. Multivariate assessment of explicit memory function in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2001;14:413–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Vasterling JJ., Brailey K., Constans J. I., et al. Attention and memory dysfunction in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychology. 1998;12:125–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Neuropsychology. 1998;12:125–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Vasterling JJ., Duke LM., Brailey K., et al. Attention, learning, and memory performance and intellectual resources in Vietnam veterans: PTSD and no disorder comparisons. Neuropsychology. 2002;16:5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Samuelson KW., Neylan T., Lenoci M., et al. Neuropsychological functioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychology. 2006;20:716–726. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Bremner JD., Vermetten E., Nafzal N., et al. Deficits in verbal declarative memory function in women with childhood sexual abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:643–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Bremner JD., Randall PR., Capelli S., et al. Deficits in short-term memory in adult survivors of childhood abuse. Psychiatry Res. 1995;59:97–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Jenkins MA., Langlais PJ. , Delis D., et al. Learning and memory in rape victims with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:278–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

, Delis D., et al. Learning and memory in rape victims with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:278–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Johnsen GE., Asbjornsen AE. Verbal learning and memory impairments in posttraumatic stress disorder: the role of encoding strategies. Psychiatry Res. 2009;165:68–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Golier JA., Yehuda R., Lupien SJ., et al. Memory performance in Holocaust survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1682–1688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Yehuda R., Golier JA., Harvey PD., et al. Relationship between Cortisol and age-related memory impairments in Holocaust survivors with PTSD. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:678–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Danckwerts A., Leathern J. Questioning the link between PTSD and cognitive dysfunction. Neuropsychol Rev. 2003;13:221–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Samuelson K., Krueger C. , Burnett C., Wilson. C. Neuropsychological functioning in children with posttraumatic stress disorder. Child Neuropsychol. 2010;16:119–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

, Burnett C., Wilson. C. Neuropsychological functioning in children with posttraumatic stress disorder. Child Neuropsychol. 2010;16:119–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Moradi AR., Doost HT., Taghavi MR., et al. Everyday memory deficits in children and adolescents with PTSD: performance on the Rivermead Behavioural Memory test. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40:357–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Yasik L., Saigh P., Oberfield. R., Halamandaris P. Posttraumatic stress disorder: memory and learning performance in children and adolescents. Bio Psychiatry. 2007;61:382–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Neylan T., Lenoci M., Rothlind J., et al. Attention, learning, and memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2004;17:41–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Kivling-Boden G., Sundbom E. Cognitive abilities related to post-traumatic symptoms among refugees from the former Yugoslavia in psychiatric treatment. Nordic J Psychiatry. 2003;57:191–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nordic J Psychiatry. 2003;57:191–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Pederson CL., Maurer SH., Kaminski PL., et al. Hippocampal volume and memory performance in a community-based sample of women with posttraumatic stress disorder secondary to child abuse. J Trauma Stress. 2004:1737–1740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Stein MB., Hanna C., Vaerum V., Koverola C. Memory functioning in adult women traumatized by childhood sexual abuse. J Trauma Stress. 1999;12:527–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Stein M., Kennedy C., Twamley E. Neuropsychological function in female victims of intimate partner violence with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:1079–1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Zalewski C., Thompson W., Gottesman I. Comparison of neuropsychological test performance in PTSD, generalized anxiety disorder, and control Vietnam veterans. Assessment. 1994;1:133–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Sullivan K., Krengel M., Proctor S., et al. Cognitive functioning in treatment-seeking Gulf War veterans: pyridositmine bromide use and PTSD. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32:515–528. [Google Scholar]

Sullivan K., Krengel M., Proctor S., et al. Cognitive functioning in treatment-seeking Gulf War veterans: pyridositmine bromide use and PTSD. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32:515–528. [Google Scholar]

27. Brewin CR., Kleiner JS., Vasterling JJ., Field AP. Memory for emotionally neutral information in posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analytic investigation. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116:448–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Johnsen GE., Asbjornsen AE. Consistent impaired verbal memory in PTSD: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord . 2008;111:74–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Vasterling JJ., Brailey K., Sutker B. Olfactory identification in combatrelated posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13:241–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Barrett DH., Green ML., Morris R., et al. Cognitive functioning and posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1492–1494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Southwick S., Rasmusson A., Barron J., Arnsten A. Neurobiological and neurocognitive alterations in PTSD: a focus on norepinephrine, serotonin, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. In: Vasterling J, Brewin C, eds. Neuropsychology of PTSD: Biological, Cognitive, and Clinical Perspectives. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005:178–207. [Google Scholar]

Southwick S., Rasmusson A., Barron J., Arnsten A. Neurobiological and neurocognitive alterations in PTSD: a focus on norepinephrine, serotonin, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. In: Vasterling J, Brewin C, eds. Neuropsychology of PTSD: Biological, Cognitive, and Clinical Perspectives. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005:178–207. [Google Scholar]

32. Shin L., Rauch S., Pittman R. Structural and functional anatomy of PTSD: findings from neuroimaging research. In: Vasterling J, Brewin C, eds. Neuropsychology of PTSD: Biological, Cognitive, and Clinical Perspectives. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005:178–207. [Google Scholar]

33. Luine V., Villages M., Martinex C., et al. Repeated stress causes reversible impairments of spatial memory performance. Brain Res. 1994;639:167–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Diamond DM., Fleshner M., Ingersoll N., et al. Psychological stress impairs spatial working memory: relevance to electrophysiological studies of hippocampal function. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110:661–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Behav Neurosci. 1996;110:661–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Karl A., Schaefer M., Malta L., Dorfel D., Rohleder N., Werner A. A metaanalysis of structural brain abnormalities in PTSD. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:1004–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Kitayama N., Vaccarino V., Kutner M., Weiss P., Bremner JD. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measurement of hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2005;88:79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Shin LM., Shin PS., Heckers S., et al. Hippocampal function in posttraumatic stress disorder. Hippocampus. 2004;14:292–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Bremner JD., Vythilingam E., Vermetten E., et al. MRI and PET study of deficits in hippocampal structure and function in women with childhood sexual abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:924–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Schuff N., Neylan T. , Lenoci M., et al. Decreased hippocampal N-acetylaspartate in the absence of atrophy in posttraumatic stress disorder. Bio Psychiatry. 2001;50:952–959. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

, Lenoci M., et al. Decreased hippocampal N-acetylaspartate in the absence of atrophy in posttraumatic stress disorder. Bio Psychiatry. 2001;50:952–959. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Freeman T., Cardwell D. Karson C, Komoroski R. In vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the medial temporal lobes of subjects with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Mag Res Med. 1998;40:66–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Delahanty DL., Raimonde AJ., Spoonster E., et al. Injury severity, prior trauma history, urinary Cortisol levels, and acute PTSD in motor vehicle accident victims. J Anxiety Disord. 2003;17:149–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Yehuda R., Kahana B., Binder-Brynes K., et al. Low urinary Cortisol excretion in holocaust survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:982–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Yehuda R., Teicher MH., Levengood RA., et al. Orcadian regulation of basal Cortisol elevations in posttraumatic stress disorder. Ann. NY Acad Sci. 1994:378–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ann. NY Acad Sci. 1994:378–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Yehuda R., Teicher MH., Trestman RL., et al. Cortisol regulation in posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression: a chronobiological analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:79–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Baker DB., West SA., Nicholson WE., et al. Serial CSF corticotropin-releasing hormone levels and adrenocortical activity in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:585–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Carrion V., Weems C., Reiss A. Stress predicts brain changes in children: a pilot longitudinal study on youth stress, posttraumatic stress disorder, and the hippocampus. Pediatrics. 2007;119:509–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Carrion V., Haas B., Garrett A., Song S., Reiss AL. Reduced hippocampal activity in youth with posttraumatic stress symptoms: an FMRI study. J Pediatric Psychology. 2010;35:559–569. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Laakso MP., Soininen H., Partanen K., et al. Volumes of hippocampus, amygdale and frontal lobes in the MRI-based diagnosis of early Alzheimer's disease: correlation with memory functions . J Neural Transm: Parkinson's Disease and Dementia Section. 1995;1:73–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Laakso MP., Soininen H., Partanen K., et al. Volumes of hippocampus, amygdale and frontal lobes in the MRI-based diagnosis of early Alzheimer's disease: correlation with memory functions . J Neural Transm: Parkinson's Disease and Dementia Section. 1995;1:73–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Soininen H., Partanen K., Pitkanen A. et al. Volumetric MRI analysis of the amygdale and the hippocampus in subjects with age-associated memory impairment: correlation to visual and verbal memory. Neurology. 1994;44:1660–1668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Convit A., de Leon MJ., Tarshish C., et al. Hippocampal volume losses in minimally impaired elderly. Lancet. 1995;345:266–XX. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Zimmerman M., Pan JW., Hetherington HP., et al. Hippocampal neurochemistry, neuromorphometry, and verbal memory in nondemented older adults. Neurology. 2008;70:1594–1600. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Bremner JD., Randall P. , Scott TM., et al. MRI-based measurement of hippocampal volume in patients with combat- related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:973–981. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

, Scott TM., et al. MRI-based measurement of hippocampal volume in patients with combat- related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:973–981. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Vythilingam M., Luckebaugh D., Lam T., et al. Smaller head of the hippocampus in Gulf War-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2005;139:89–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Woodward S., Kaloupek D., Grande L., et al. Hippocampal volume and declarative memory function in combat-related PTSD. J int Neuropsychol Soc. 2009;15:830–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Bremner JD., Randall P., Vermetten E., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-based measurement of hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood physical and sexual abuse-a preliminary report. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:23–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Nakano T., Wenner M., Inagaki M., et al. Relationship between distressing cancer-related recollections and hippocampal volume in cancer survivors. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:2087–2093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:2087–2093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Shimamura AP. Memory and frontal lobe function. In: Gazzaniga MS, ed. The Cognitive Neurosciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1996:803–814. [Google Scholar]

58. Theirry AM., Tassin JP., Blanc G., Glowinsky J. Selective activation of the mesocortlcal DA system by stress. Nature. 1976;263:242–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Goldstein LE., Rasmusson AM., Bunney BS., Roth RH. Role of the amygdala in the coordination of behavioral, neuroendocrine, and prefrontal cortical monoamine responses to psychological stress in the rat. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4787–4798. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Arnsten AF. Through the looking glass: differential noradrenergic modulation of prefrontal cortical function. Neuronal Plasticity. 2000;7:133–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Brandes D., Ben-Schachar G., Gilboa A., et al. PTSD symptoms and cognitive performance in recent trauma survivors. Psychiatry Res. 2002;110:231–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychiatry Res. 2002;110:231–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Beers SR., De Bellis MD. Neuropsychological function in children with maltreatment-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:483–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Koenen KC., Driver KL., Oscar-Berman M., et al. Measures of prefrontal system dysfunction in posttraumatic stress disorder. Brain Cogn. 2001;45:6478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Ehring T., Quack D. Emotion regulation difficulties in trauma survivors: the role of trauma type and PTSD symptom severity. Behav Ther. 2010;41:587–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Tull MT., Barrett HM., McMillan ES., Roerner L. A preliminary investigation of the relationship between emotion regulation difficulties and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Behav Ther. 2007;38:303–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. De Bellis M., Keshavan. M., Shifflett H., et al. Brain structures in pediatric maltreatment-related post-traumatic stress disorder: a sociodemographically matched study. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:1066–1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:1066–1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Carrion V., Weems C., Eliez S., et al. Attenuation of frontal asymmetry in pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder. Bio Psychiatry. 2001;50:943–951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Fennema-Notestine C., Stein M., Kennedy C., et al. Brain morphometry in female victims of intimate partner violence with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:1089–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Rauch SL., Shin LM., Segal E., et al. Selectively reduced regional cortical volumes in post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuroreport. 2003;14:913–916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Yamasue H., Kasai K., Iwanami A., et al. Voxel-based analysis of MRI reveals anterior cingulate gray-matter volume reduction in posttraumatic stress disorder due to terrorism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9039–9043. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Woodward SH. , Kaloupek DG., Street CC., et al. Decreased anterior cingulate volume in combat-related PTSD. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:582–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

, Kaloupek DG., Street CC., et al. Decreased anterior cingulate volume in combat-related PTSD. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:582–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Rogers MA., Yamasue H., Abe O., et al. Smaller amygdale volume and reduced anterior cingulated gray matter density associated with history of post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2009;174:210–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Geuze E., Vermetten E., Ruf M., et al. Neural correlates of associative learning and memory in veterans in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:659–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. De Bellis M., Keshavan M., Spencer S., Hall J. N- Acetylaspartate concentration in the anterior cingulate of maltreated children and adolescents with PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1175–1177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Gilbertson M., Paulus L., Williston S., et al. Neurocognitive function in monozygotic twins discordant for combat exposure: Relationship to posttraumatic stress disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;11:484–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;11:484–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Gilbertson M., Shenton M., Ciszewski A., et al. Smaller hippocampal volume predicts pathologic vulnerability to psychological trauma. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:1242–1247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Parslow R., Jorn A. Pretrauma and posttrauma neurocognitive functioning and PTSD symptoms in a community sample of young adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:509–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Vasterling J., Brailey K. Neuropsychological findings in adults with PTSD. In: Vasterling J, Brewin C, eds. Neuropsychology of PTSD: Biological, Cognitive, and Clinical Perspectives. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005:178–207. [Google Scholar]

79. Wild J., Gur R. Verbal memory and treatment response in post-traumatic stress disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193:254–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Surviving a head-on collision and why amnesia is not what you think / Habr

Hi Habr.

Not so long ago I was in a car accident, and I experienced firsthand what broken bones, severe traumatic brain injury and memory loss are like. In the article, I also want to talk about the misconceptions about the symptom of amnesia in modern popular culture. The area is quite confusing and controversial, but I still wanted to structure the known data and share my personal experience.

Background

Briefly about me

I am 22 years old, studied for a bachelor's degree in engineering, worked as a freelancer (mostly web, although I use Python and C).

Recently I have been learning Java and developing a reader for Android (well, there are no normal open readers, they either slow down, or the functionality is cut down, or there are no settings).

Semi-professional in mountain biking (cross-country) and aikido, but I never had any special achievements in sports.

It was at the beginning of March. The family dinner dragged on and I had to call a taxi, because the transport was no longer running, and I had to go to the neighboring city. It wasn't that anyone was drunk or anything, it was just that the oncoming driver was taking a little nap on a dark suburban road. Of course, I was fastened, but after a collision with a 2-ton Mitsubishi Pajero, there was little left of the light Prius. Unfortunately, the driver died before the ambulance arrived.

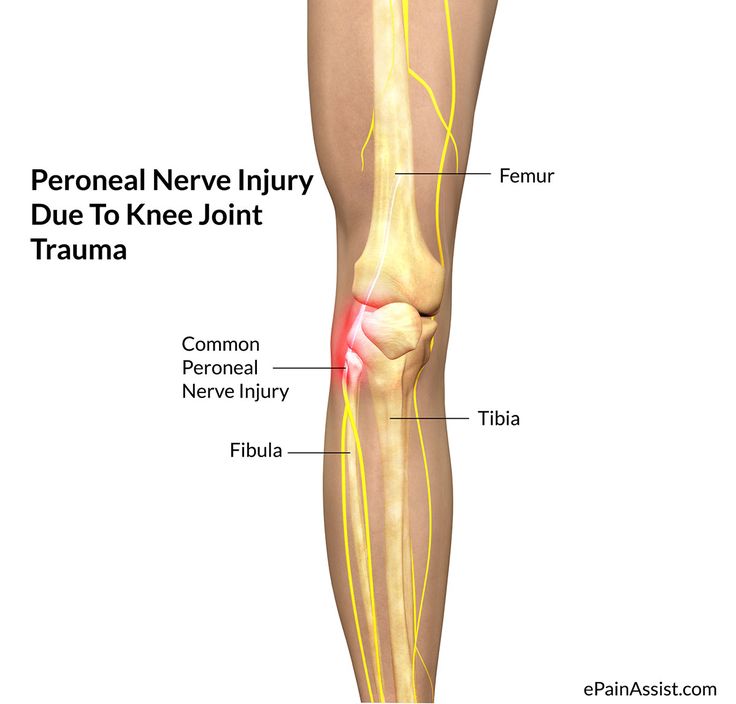

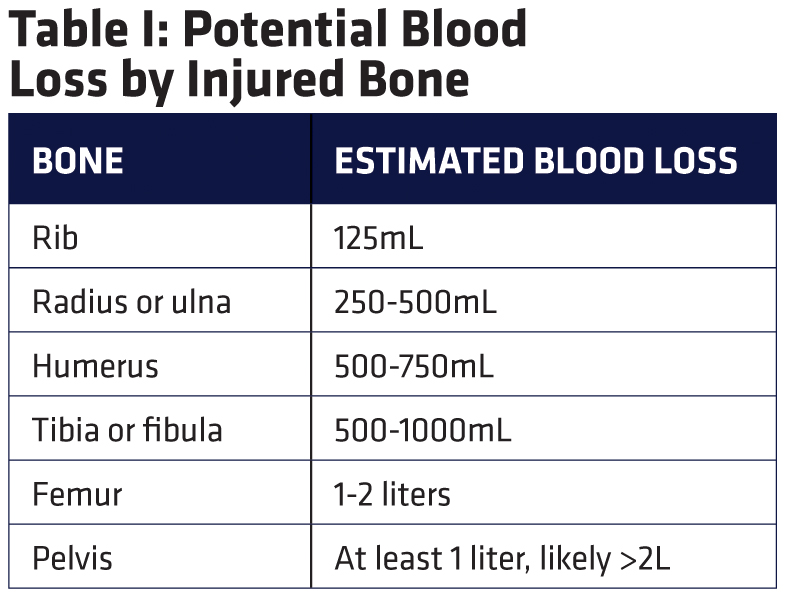

As a result: an open fracture of the leg in 2 places (tibia and fibula + dislocation of the ankle), fracture of the wrist and 3 fingers, dislocation of the elbow joint, numerous minor bruises and cuts, injuries of the cervical spine, severe craniocerebral trauma, cerebral edema and eye damage. And also, as a bonus, a coma lasting 10 days.

Recovery was difficult: nauseating headaches that painkillers could not cope with, sounds resounding in the skull with a painful echo, pain in the leg, and in the arm, and in general in the whole body, insomnia and a depressive state. Even when I managed to fall asleep, there was no particular relief, because the dream was very restless, I had nightmares.

Even when I managed to fall asleep, there was no particular relief, because the dream was very restless, I had nightmares.

Of course, I have crashed on a bike before, but from serious injuries (when I was doing Enduro) I was always saved by protective equipment - a full-face helmet (similar to those used in motocross), shell, neck support, pads, etc. ., so for me it was a new and completely nightmarish experience.

I spent almost 7 weeks in the hospital, I think you can imagine what it's like.

Traffic accident statistics

According to statistics compiled by WHO, in 2016 the number of deaths related to road accidents reached 1.35 million people. And, despite the fact that the mortality rate for 15 years has generally decreased from 18.8 to 18.2 per 100,000 people, the absolute figure continues to grow every year.

Every year, between 20 and 50 million people suffer non-fatal injuries, and many become disabled.

Road crashes are the leading cause of death for children and young people aged 5 to 29 and are the 8th leading cause of death among people of all ages [1] .

About amnesia

disclaimer: I am not a specialist in brain neurophysiology, neuropsychiatry, psychiatry or any other medical specialty. The following descriptions are my attempt to make sense of the often very contradictory material, and may be erroneous, but certainly superficial and inaccurate.

After coming out of the comatose state, I was completely disoriented, there was an inability to understand the contents of conversations and confused meaningless speech.

In fact, I did not realize myself, and I could not talk. These memories have not been preserved (the description was restored from conversations with the doctor), but everything somehow turns cold inside me at the mere thought that brain damage could be irreversible.

It's not even the state itself that frightens, after all, if you can't understand anything, then nothing can bother you. More frightening is the thought of how parents could survive this. It hurts me even now to see how haggard and old they are because of this whole situation. But, at least, I try not to strain them once again, and somehow I try to do everything on my own (well, I try to restrain the impulses of my far from mild character).

It hurts me even now to see how haggard and old they are because of this whole situation. But, at least, I try not to strain them once again, and somehow I try to do everything on my own (well, I try to restrain the impulses of my far from mild character).

Amnesia in popular culture and reality

Descriptions of amnesia in popular culture (movies, books, games, etc.) are rather inaccurate. Every example I've come across from Prince Corwin to Gunner to James Bourne describes retrograde amnesia, but is unrealistic. The exception, oddly enough, are the cartoons made by Pixar - "Finding Nemo" and "Finding Dory", where Dory the fish suffers from anterograde amnesia, which I will write about a little later. The same theme is used in the films "Memento" and "50 First Dates", but this movie is not very realistic.

The very same retrograde amnesia is depicted as follows: there is a hero, he gets into some kind of unpleasant situation, and as a result he gets a head injury, after which, to the sad music, he painfully tells his relatives and friends that he can’t anyone and nothing recall. At the same time, the main character quite remembers how to drive a car, knows how to fight, and behaves like a completely healthy person.

At the same time, the main character quite remembers how to drive a car, knows how to fight, and behaves like a completely healthy person.

In reality, everything is a little different (with such injuries, perhaps, you can drool) and, in fact, people who have lost memories of their personality after a traumatic impact, but at the same time retained: general knowledge, professional skills, knowledge of languages (including native language) or the ability to do half-pirouettes, in general, should not exist, because memory is impaired for a certain period of time [2] .

If a person does not have memories of his own personality, then he will have skills and knowledge from the period before realizing his personality, for example, like children, until they are able to remember their name.

Screenwriters and writers also have problems with anterograde amnesia. Usually some ridiculous restrictions are introduced: memory loss after 15 minutes or sleep. In fact, in case of serious problems with memory consolidation , thoughts or events are forgotten immediately after the person is distracted.

Classification

Amnesia can be classified in various ways, but in my opinion, it is most logical to first consider the cause of the symptom, then the symptom itself and the dynamics of development.

▍ Causes of symptom development:

- organic [2] - caused by brain damage.

Possible causes:

- TBI

- infections

- stroke

- brain diseases (including age-related)

- psychogenic - caused by mental disorders.

Possible causes:

- traumatic event

- long depressions

- psychosis

▍ Symptoms:

Anterograde amnesia - inability to remember new memories. Depending on the severity, fragmentary or partial memories may remain, or not remain at all.

Cause of appearance: organic brain damage, mental trauma.

Associated areas of the brain: temporal lobes, diencephalon, hippocampus.

Treatment: there is no drug treatment, it is possible to train the brain for partial memorization [3] .

Temporal lobes and diencephalon

Retrograde amnesia - inability to recall events preceding the onset of the symptom. The more severe the injury, the longer the memory period can be affected. At the same time, early memories are more stable and are restored first [4] .

Cause of appearance: organic brain damage, mental trauma.

Associated areas of the brain : hippocampus, anterior nuclei of the thalamus.

Treatment: depending on the causes of the symptom, but most often drugs that improve blood circulation, neuroprotectors, nootropics, antioxidants and B vitamins are used [4] .

Hippocampus and Thalamus

Forms of retrograde amnesia

- Partial - fragments of events and vague images are stored in the memory, while space-time orientation is violated

- Complete - memories completely lost for a certain period of time

- Temporary (post-traumatic) - inability to reproduce the events preceding the injury, most often a few minutes, hours or days before the injury, less often months or more (often the moment of the injury itself can never be remembered)

- Permanent - occurs in case of serious vascular damage (encephalitis, stroke, etc.

)

)

Transient global amnesia is a time-limited episode of memory loss (up to 2 days), with no signs of injury.

The ability to remember, and memory, is lost for a period from a day to several years. The memory of one's own personality, general and professional skills are preserved.

Reason for appearance: Unknown [5] .

Associated areas of the brain : Most likely the hippocampus.

Treatment: Not required.

This is a list of MB21.1 symptoms from the ICD-11. All other types of amnesia are a specific variation or a combination of variations of retrograde and anterograde amnesia, so I will not consider them in detail, with the exception of a symptom that can combine both signs of retrograde amnesia and anterograde, but with a psychogenic cause:

Dissociative amnesia - memory loss that can block memories of a person, while maintaining general skills and knowledge [6] . Most often there are cases with partial loss of memory for certain events, but sometimes the ability to remember events is lost.

Most often there are cases with partial loss of memory for certain events, but sometimes the ability to remember events is lost.

Cause: mental trauma

Associated areas of the brain: not directly connected

Treatment: depending on the condition of the patient

Fugue amnesia

Fugue amnesia is a subtype of dissociative amnesia with 2 stages:

1. A person forgets his identity and at the same time moves to an unfamiliar place.

2. Remembers his personality, forgetting what happened during the 1st stage.

It is a rather rare and poorly studied phenomenon of self-defense of the human psyche.

[6] , I have not found any evidence that this type of amnesia can be caused by physiological or physical effects (i.e., substances or injuries) (but here on Wikipedia it is indicated that pharmacological and somatic causes are excluded).

Also, symptoms are often divided according to the dynamics of development: progressive, regressive or stationary.

The general classification is very confusing. So in the ICD-11 reference book, in addition to symptoms, there is "Amnetic disorder". I don’t really understand why it was necessary to introduce the syndrome as well. In my opinion, memory loss is not a disease, but a sign of certain diseases, injuries, etc., and you should not produce unnecessary entities. But doctors have a different logic.

The writers also describe dissociative amnesia after a head injury, but this does not happen in real life.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosis is based on the combination of the following data [4] :

- Anamnesis confirming the presence of a traumatic factor

- Memory tests, different countries use ( MMSE , AMI )

- Instrumental diagnostics: EEG , Ultrasound , X-ray of the skull, MRI , CT

Memory operation

Separately, it is worth noting that memories are not erased from the brain, and problems arise with their reading [2] . To exaggerate, in the human brain, as well as in computers, there is short-term and long-term memory, consciousness can process information that is in the operational part of short-term memory using intelligent operations.

To exaggerate, in the human brain, as well as in computers, there is short-term and long-term memory, consciousness can process information that is in the operational part of short-term memory using intelligent operations.

Short-term memory is a temporary neural connections located in the frontal (mainly dorsolateral prefrontal) area of the brain and in the parietal cortex.

- structure of the brain (illustration by Wikimedia user Pancrat, CC BY-SA 3.0)

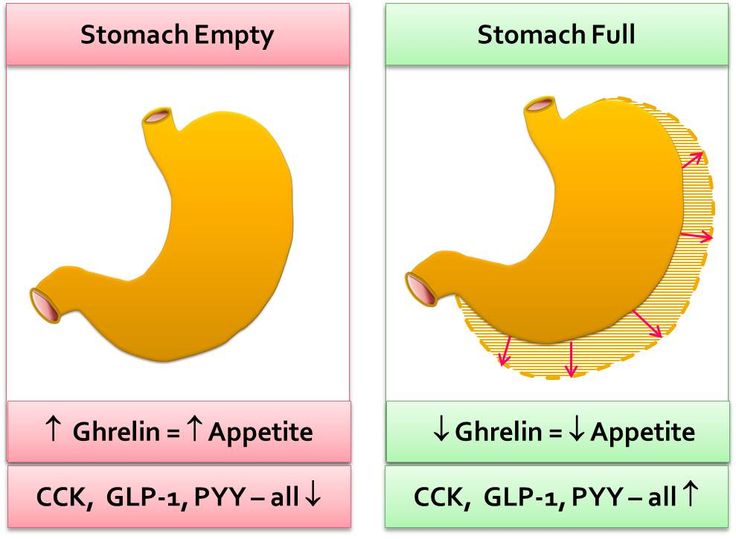

The amount of information in short-term memory is seriously limited, as is the storage time (20-30 seconds). At the same time, consciousness cannot directly work with long-term memory distributed throughout the brain, so it is necessary to decode and load data into short-term memory using the hippocampus and, probably, the system of the anterior nuclei of the Thalamus responsible for connectivity. The hippocampus is also responsible for saving data from short-term memory to long-term memory.

▍ Types of long-term memory:

There are many typologies of memory, but I will only consider the division according to the organization of memorization and awareness:

- Declarative memory - includes the memorization of words, faces and events.

Declarative memory can be divided into:

- Semantic - general knowledge about the world represented by words, for example, if you mention the word "cat", then data about cats should appear in memory, without emotional coloring

- Episodic - memories of events from the past (this also includes autobiographical memory), allows you to reproduce what happened. It is this memory that is blocked in dissociative amnesia

- Procedural Memory - Responsible for skills brought to automatism

Example: using a mouse, driving a bicycle and other actions that do not need to be thought about

Episodic memory is hierarchically dependent on semantic, i. e. first, the semantic basis is invoked, and only then memories are layered on top.

e. first, the semantic basis is invoked, and only then memories are layered on top.

Semantic and procedural memory are more stable: knowledge and skills are less often forgotten. There are studies confirming that procedural memory has a different algorithm for recording and processing memory, for example, patients with anterograde amnesia retained the skill of playing the "Tower of Hanoi" [7] , even if they did not remember that they had assembled the tower before. It is assumed that procedural memory is processed independently of declarative memory and without the participation of consciousness, but both types of memory are closely interconnected. For example, if you are an experienced Starcraft player, you will unconsciously perform hundreds of actions while simultaneously analyzing the situation and planning further actions and tactics.

I have never been able to find any evidence that procedural or semantic memory can be preserved in the event of severe organic brain damage that causes episodic memory failure. It is likely that the algorithm for consolidating from long-term to short-term memory does not differ much for different types of memory.

It is likely that the algorithm for consolidating from long-term to short-term memory does not differ much for different types of memory.

Conclusion

As for me, the signs of anterograde amnesia disappeared 4 days after regaining consciousness, speech function was restored around the same time and most of the memories returned, although I remember about six months or a year before the accident very fragmentary and vaguely (more precisely, almost I don't remember anything, it's a partial form of retrograde amnesia).

It doesn’t really bother me, in the end people always forget everything, much more problems are caused by a broken body and severe pain. On the other hand, the topic is quite interesting and important, because who are we without our memories and brain. An empty shell, nothing more.

Once, in the hospital, they sent me a staff psychotherapist, to whom I developed a strong dislike because of stupid mocking advice like "relax and have fun. "

" It is a pity that there was no HK-47 at hand. But, in general, I very quickly refused to communicate with this horseman, and I do not visit a psychotherapist.

Firstly, I don't believe that it can help in any way, and secondly, why pay that kind of money? For chatting? Moreover, finding a good specialist is not an easy task.

Therefore, in order to somehow begin to move away from what happened, I started working on an article about the Knights of the Old Republic series of games (and these are one of my favorite games). I wanted to know if I can create something or now my limit is a couple of hours a day to watch the series.

The writing of the article took more than 2.5 months, and everything was very difficult. I had to type with one hand, and take constant breaks, because the slightest effort was very tiring. Well, I had to get used to monocular vision.

Not everything was done the way I wanted, but sometimes you just need to complete the project, otherwise you will never be able to finish it. The article itself will be published on Friday (I hope).

The article itself will be published on Friday (I hope).

At the moment, although I have severe headaches, they are not as unbearable as at first, and in general I already feel better, I can move independently and even do simple things.

*nervously adjusts the dressing gown, taken secretly from the doctor*

I would like to wish everyone not to get into such situations. Take care of your brain. Try to eat right according to WHO recommendations, do not forget about physical activity (it is not necessary to be an extreme athlete, you can go swimming, Nordic walking or just do exercises). Engage in intellectual and creative activities.

All this reduces the likelihood of developing brain diseases [8] .

And a small message to drivers:

Remember that not only your life, but also the lives of the people around you depend on your actions while driving, so don't forget to rest while driving.

Materials used in the article:

1. Road traffic injuries. World Health Organization, article.

Road traffic injuries. World Health Organization, article.

2. Understanding Memory: Explaining the Psychology of Memory through Movies. course of lectures by Professor John Simon on Coursera.

3. Current Approaches in Psychiatry. Erdogan, Serap (2010), book

4. "Retrograde amnesia." Article on Liqmed.

5. What is amnesia and how is it treated? Christian Nordquist, article.

6. “Autopersonal amnesia (biographical amnesia): Depersonalization? Conversion? Simulation? Organic amnesia? Independent Psychiatric Journal, article.

7. “Posttraining increases in REM sleep intensity implicate REM sleep in memory processing and provide a biological marker of learning potential.” Article.

8. Dementia World Health Organization, article.

Article licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

P. s. Unfortunately, I am not able to personally thank you all, so I am writing here.

Thank you all for your kind words and wishes. And for your own stories.

Amnesia: Causes, Symptoms, Treatment | doc.

ua

ua Types of amnesia

There are two forms of the disease - retrograde (the patient does not remember the events that occurred before the disease) and anterograde (the patient does not remember the events that occurred after the onset of the disease).

Retrograde amnesia

Usually does not affect events long in the past, ie. the most frequent cases of loss of memory about the last hours or weeks, less often - months. A sign of recovery is usually a decrease in the period of lost memory, but the memory of the time immediately preceding the onset of the disease is extremely rare.

Anterograde amnesia

Characterized by an unlimited period of memory loss, the duration of which is closely related to the duration of post-traumatic disorder of conscious activity. If anterograde memory loss has developed as a consequence of a traumatic brain injury, then the period of memory loss will depend on its severity.

There are other forms of amnesia, usually classified by developmental causes, such as the protective form of the disease, which represses traumatic events from memory, or post-hypnotic, the loss of the ability to recall events experienced in a hypnotic trance state.

Researchers have also identified spontaneous memory loss (the cause of which is probably simply not identified) and Korsakoff's syndrome (inability to fix current events), which is formed due to a lack of vitamin B1.

Regardless of the form of the disease, upon recovery, the ability to learn new skills and new information is the last to return, memory returns strictly chronologically (starting with the most distant memories), and the events immediately preceding the onset of the disease are often never restored.

Causes

Among the most common causes of amnesia can be identified primarily traumatic brain injury, emotional shock, tumors and strokes. However, the disease can also be triggered by a number of other diseases, such as epilepsy, mental illness, degenerative brain disease, metabolic encephalopathy, intoxication, and herpetic encephalitis.

One example of psychogenic amnesia, for example, is a dissociative fugue that develops as a result of moving to a new place of residence or a complete change of environment. The patient may be completely unable to remember his past for months or even years, while he may suddenly remember and forget individual events again.

The patient may be completely unable to remember his past for months or even years, while he may suddenly remember and forget individual events again.

The reason for the development of another type of disease - dissociated, is a temporary loss of memory of traumatic events (loss of loved ones, severe stress, shock), but the memory of other events and skills remains in perfect order. Interestingly, in dissociated amnesia, memory function is impaired only in the waking state, while in an altered state of consciousness (sleep, trance, hypnosis), the patient can recall all events.

Among the causes contributing to the development of Korsakoff's syndrome, alcoholism and malnutrition dominate. From the point of view of the anatomy of the brain, any violation of the functions of its key parts can, depending on the severity of the injury, provoke the development of amnesia.

Symptoms

Often, amnesia is associated with other disorders of the nervous system and cognitive function of the brain, such as pronounced thinking disorders, incoherent speech, inability to control attention, anxiety or depression.

Anterograde amnesia

Patients with anterograde amnesia exhibit perfectly normal behavior upon first contact, but memory problems are easily identified if recent events are mentioned in the conversation.

Retrograde amnesia

Patients with retrograde amnesia have excellent recall of recent events, but have difficulty remembering events a week or a month ago. This form of the disease may not affect the events of the distant past, so it is necessary to analyze their memories in stages. The main difficulty in identifying retrograde amnesia is the tendency in many patients to fill in memory gaps with false memories.

Korsakov's syndrome

The presence of symptoms of Korsakov's syndrome is indicated by the patient's disorientation in time and space, impaired attention and false memory (the patient reports fictitious events). The most resistant to forgetting information is the memory of self-identification (name, surname, date and place of birth).

Amnesia, in which the patient does not remember distant events of his past and personally identifiable data, is most likely psychogenic in nature, i.e. caused by serious mental disorders.

Diagnosis

For the treatment of amnesia, it is necessary to determine the cause of the development of the disease as accurately as possible and all possible parallel provocations. To do this, when symptoms are detected, a comprehensive examination is necessary with the obligatory consultation of a psychiatrist, narcologist and neuropathologist.

For in-depth diagnostics, special detailed testing of memory functions and examination by a traumatologist, infectious disease specialist, neurosurgeon and other highly specialized specialists are used. If necessary, a blood test, ECG, MRI, computed tomography and toxicological analysis are prescribed.

Treatment

The structure and function of human memory have not yet been fully studied, and research in this area is being actively conducted around the world. Modern data show that in humans, as in some animals, not only the brain, but the entire nervous system is involved in the process of memorization.

Modern data show that in humans, as in some animals, not only the brain, but the entire nervous system is involved in the process of memorization.

Treatment of memory loss must be carried out carefully and in stages, especially to prevent real memories from being replaced by false ones. Treatment of amnesia begins with the neutralization of the underlying disease or traumatic event, as well as the factors that contributed to memory loss.

For drug therapy, a wide range of antioxidants and neuroprotectors are actively used, for example, cerebrolysin, memantine, cortexin, cytoflavin, semax, citicoline, ginkgo biloba extract, glycine and vitamins. A variety of techniques and methods of neuropsychological rehabilitation are very effective in promoting recovery.

Amnesia, the treatment of which is complicated by the psychogenic nature of the disease or for the treatment of non-progressive forms, neuropsychological therapy is effective. If the effect of the underlying disease and other provocateurs of amnesia is eliminated, drug therapy is oriented towards enhancing the cholinergic transmission of the brain.