Living well meaning

What Does "Living Well" Mean To You?

While I was going through the initial re-design process for my blog over the last month (it’s currently in development and should be done within the next couple of weeks!), I had to do some deep diving into my “why.” Why is this blog important to me? What is it that really makes me feel lit up enough to share my personal opinions and insights with the world, when I could always just keep it inside my own head and never share? Why did I want to start a blog in the first place? What kind of impact do I hope to have?

When I sit back into the feeling of why I wanted to start a blog, many years ago, it was for a few reasons:

- I was learning about new things every day that made me feel good, and excited, and healthy, and enthusiastic.

But why the impulse to share?

- Because so much of the inspiration and knowledge I found for my own life was what I had read on blogs — if the bloggers hadn’t shared them, I may have never received that spark of insight or inspiration that is the catalyst for change.

I wanted to give back to the community who was giving so much to me, and (hopefully) create that same moment of “spark” for others.

- “Living well” for me led directly to feeling more creativity. The better I treated myself, the more creative I felt, and the more my creativity felt like a wellspring of insight just waiting to burst forth and become something outside of me.

Healthy Crush – “a love affair with living well.”

When my friend Jeanne suggested that tagline for me, it felt like an immediate YES. I thought of it as feeling enamored with the process of experimenting and finding and sharing what feels good.

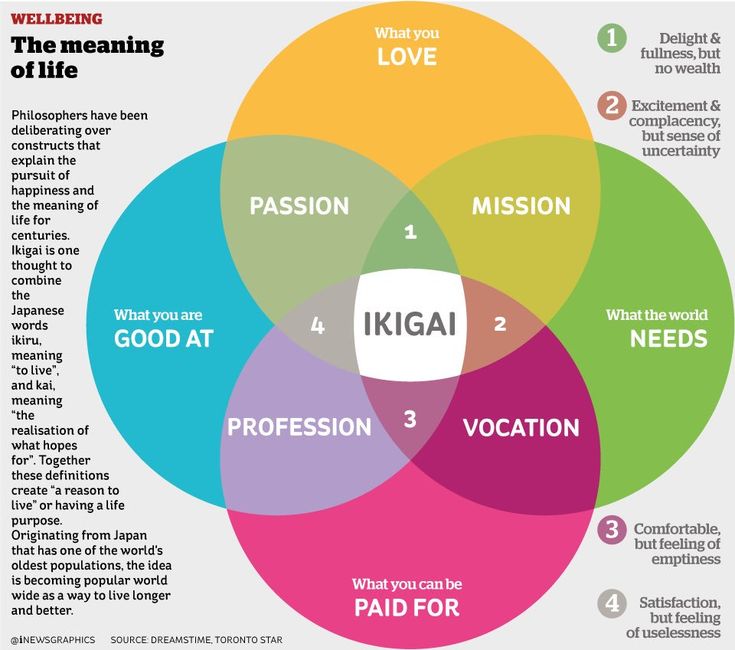

But what does “living well” actually mean? And why do I care?

It would be way too easy to say that living well is a list of things like eating lots of vegetables, avoiding sugar, exercising, being nice to people, doing work that makes you happy, and drinking enough water.

But the “living well” I care about is not a list of things to do.

It’s a feeling. It’s a way of being in the world.

I can’t always pinpoint the exact formula that contributes to that feeling of living well (it changes a lot and my experiments are never-ending) but I can always FEEL when I’m living well. I experience life in a much different way when I am.

We all have a different combination of factors that go into our own unique recipe for a life lived well. In fact, my blog many years ago before Healthy Crush was called “Recipe for Life – What’s In Yours?” because I found this concept so helpful and interesting.

I used to write a “recipe card” at the end of each day, and I’d have a plus and minus category — what ingredients (habits) I’d like to keep putting into my life recipe in the future, and what should be removed.

Regardless of the specific things that go into our individual recipes for living well, we can all probably share what living well FEELS LIKE to us.

When I’m living well, it is DIRECTLY related to how creatively expressive and inspired I feel. Sometimes it feels like creative outlets like writing, taking photos, cooking and self-expression are my lifeblood. If I’m creating and sharing a lot, it means my blood is really pumping. That I’m receiving messages and I’m translating them into something that might help even one person, and I’m putting them out there into the world. Even if it’s just a quick Instagram post, it’s energy and inspiration that’s flowing because I’m doing something right that contributes to my physical and emotional wellbeing.

When I’m living well, I don’t have to work hard to experience intuitive and creative flow. When my self-care habits include filling my mind and my body with positive input, and clearing enough space for energy to flow through, it feels effortless. It feels like simply allowing.

When I’m living well, I notice beauty more. I feel joy more. I feel more connected to life. I see things, really see things – and I get sparks of insight or emotion or appreciation, instead of just walking by. I live in a temple of enthusiasm. Inside that temple of enthusiasm, life feels like a celebration and it’s full of vivid color, and most importantly I have the energy and clarity and vibrancy and gratitude to experience it. That energy is alive and it’s extremely contagious.

I feel joy more. I feel more connected to life. I see things, really see things – and I get sparks of insight or emotion or appreciation, instead of just walking by. I live in a temple of enthusiasm. Inside that temple of enthusiasm, life feels like a celebration and it’s full of vivid color, and most importantly I have the energy and clarity and vibrancy and gratitude to experience it. That energy is alive and it’s extremely contagious.

Living well, to me, means the ability experience life and all the feelings that come with it in a way that flows through me more fluidly, without getting stuck in anxiety, depression or overwhelm. When I’m living well, those negative emotions simply aren’t able to gain the full momentum they need to consume me. With that comes the ability to make decisions with confidence, power and trust. (TM helps me with this).

Living well means having consistent habits that I show up for just because I know that the consistency supports me

, even if I don’t feel like doing it in the moment and even if there will be no “immediate” payoff.

Living well means having the energy and discipline to show up in reality for the things I set out to do in my mind. It means being able to meet my own expectations and commitments, or if I can’t meet them, being able to adjust accordingly without making a huge dramatic deal about it or feeling guilty. (I just watched this video and it helped a bit with the whole guilt thing, which I am working on).

Living well means having the emotional and energetic capacity to focus on others and how I can be helpful in the world and make some sort of positive difference, rather than focusing on my own internal dialogue constantly. The tricky part is, in order to have that capacity to care for others, I must take care of my own body and mind first. Without strengthening my own self, my “making other people happy” abilities that I care so much about will crumble. The sweet spot is being able to focus on self care and self strengthening without spending time self obsessing, worrying about doing things perfectly, or getting caught up in internal dramas.

Living well means feeling strong in my body, which inevitably leads to a stronger mind and spirit. It means actually listening to my body when it needs to move and when it needs to rest.

Living well means making choices intentionally because I KNOW how they will make me feel, based on trial and experimentation and TRUE LISTENING, rather than making choices because someone said they were good or healthy. The perfect diet or the perfect lifestyle is the one that makes YOU FEEL GOOD. It becomes more work when you have to actually pay attention to what works for you, but it is well worth the payoff when you can truly just look at a food and get an intuitive sense of how it will feel in your body.

Living well means knowing in the moment when something feels like a DEFINITE YES (or a definite no). It means noticing when a pattern of addiction is happening and having the strength and humility to course-correct. This is a constant practice and will never be perfect.

Living well means creating the financial freedom in my life that will allow me to make choices that support my well-being as wholly as possible, so I can show up for what’s important to me in the world, in this life. Relationships, experiences, travel, home, creative contributions…presence…

Living well means having the courage to have faith, and the courage to ask for help when know I can’t do it alone. The faith that I can feel better, the faith that I have the power to change what’s not working, and the faith that guidance will come. That guidance is already here. I just need to slow down and ask… and then open my eyes and pay attention.

Living well means seeing synchronicities, noticing miracles, creating enough stillness and quietude to actually feel and acknowledge when my dreams are coming true, rather than just checking a box and moving to the next thing.

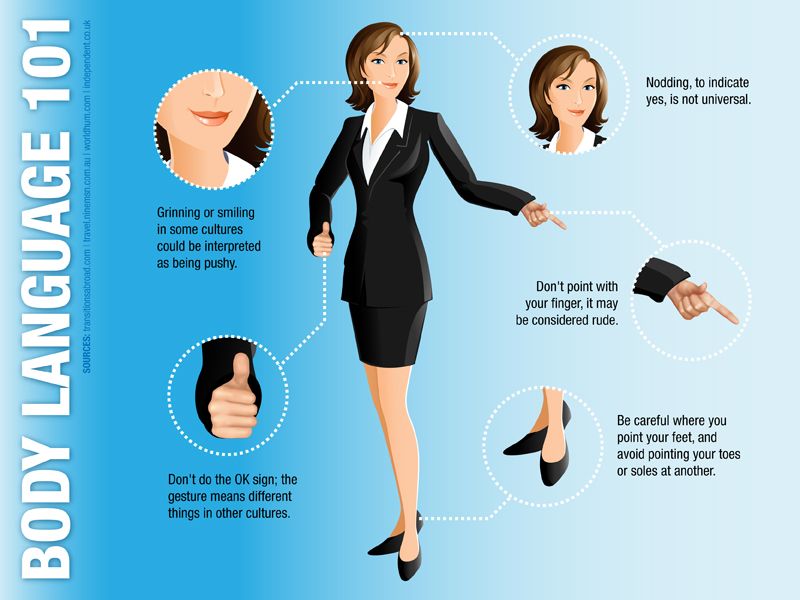

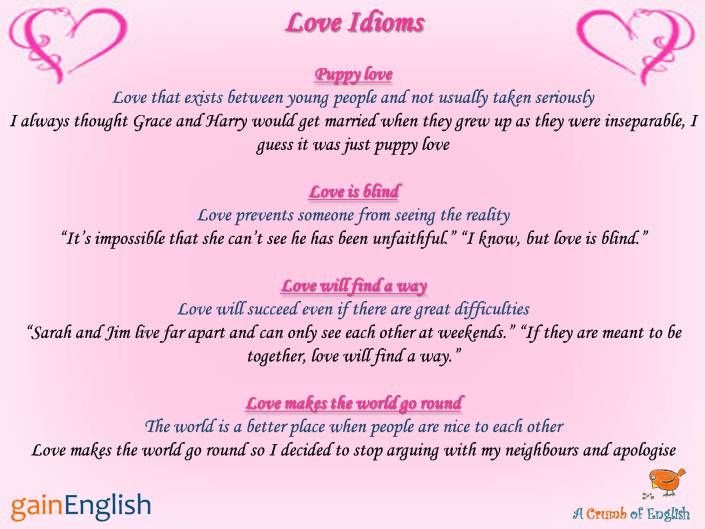

Living well means relating to others in a way that feels like real connection, love, deep laughter, understanding, appreciation and curiosity, without making anyone else’s opinion or reaction to me all powerful. It means having a strong sense of self in relation to others and being able to play together with grace and acceptance. And always being in the field of learning. And forgiving. We are humans trying to find our way in a world with no definite roadmap. We all have so much to learn from each other in relationships and we all have so much to teach.

It means having a strong sense of self in relation to others and being able to play together with grace and acceptance. And always being in the field of learning. And forgiving. We are humans trying to find our way in a world with no definite roadmap. We all have so much to learn from each other in relationships and we all have so much to teach.

Living well means to live my life on my own terms in a way that excites me, even if it seems “unconventional.”

Most of all, to me, living well means waking up with integrity.

Integrity about the woman that I choose to be in the world, knowing that I can attempt to be the best version of myself TODAY, or at least a pretty good version, with all of my tools and resources and knowledge, and with all of my flaws and limitations too. Knowing that I don’t have to do things perfectly in order to be OK at this whole life thing. It’s enough to keep learning and trying and shifting and recalculating. Appreciating the little wins every day, and not letting them slide by unnoticed.

Appreciating the little wins every day, and not letting them slide by unnoticed.

And finally, living well is a constantly evolving process. It has no true definition. It’s a breathing, growing, and ever-changing feeling.

And these are just a few things. I could go on and on.

But when I truly take care of myself, and I hook into the resources and tools and habits that elevate my existence…all of these “living well” feelings become closer to my reality.

The most we can hope for is to get to know ourselves well enough that we have a good idea of what makes us feel great, and do those things as much as possible. And then have the acceptance to let go and choose again when we took a detour or something feels off.

This is why I have a love affair with living well, because living well makes me feel truly alive. Like a sparkling, glittering stream of life.

Am I always “living well”? No way. It’s important to me to share about living well because I know, very intimately, what it feels like when I’m not. And for this reason, I’m committed to experimenting. I don’t have the time or desire to stay in an unwell place for too long.

And for this reason, I’m committed to experimenting. I don’t have the time or desire to stay in an unwell place for too long.

Here is what I do know:

It’s in those moments when we DON’T feel well that a quick Google search and a stranger’s blog post can be the spark that changes something powerful within us.

And it’s important to me to contribute to that spark, in some way, if I can.

OK, now I must know…

What does living well feel like to you?!

Let me know in the comments.

*hugs*

The Difference: Living Well vs. Doing Well

(Credit: h.koppdelaney)

“From all your herds, a cup or two of milk,

From all your granaries, a loaf of bread,

In all your palace, only half a bed:

Can man use more? And do you own the rest?”

— Ancient Sanskrit poem

Total post read time: 5 minutes.

Living well is quite different from “doing well. ”

”

In the quest to get ahead — destination often unknown — it’s easy to have life pass you by while you’re focused on other things. This post is intended as a reminder and a manifesto: keep it simple.

This is written by Rolf Potts, author of my perennial favorite and heavily highlighted Vagabonding. In the below piece, I’ve bolded some particular parts that have had an impact on my life.

Enter Rolf.

###

In March of 1989, the Exxon Valdez struck a reef off the coast of Alaska, resulting in the largest oil spill in U.S. history. Initially viewed as an ecological disaster, this catastrophe did wonders to raise environmental awareness among average Americans. As television images of oil-choked sea otters and dying shore birds were beamed across the country, pop-environmentalism grew into a national craze.

Instead of conserving more and consuming less, however, many Americans sought to save the earth by purchasing “environmental” products. Energy-efficient home appliances flew off the shelves, health food sales boomed, and reusable canvas shopping bags became vogue in strip malls from Jacksonville to Jackson Hole. Credit card companies began to earmark a small percentage of profits for conservation groups, thus encouraging consumers to “help the environment” by striking off on idealistic shopping binges.

Credit card companies began to earmark a small percentage of profits for conservation groups, thus encouraging consumers to “help the environment” by striking off on idealistic shopping binges.

Such shopping sprees and health food purchases did absolutely nothing to improve the state of the planet, of course — but most people managed to feel a little better about the situation without having to make any serious lifestyle changes.

This notion — that material investment is somehow more important to life than personal investment — is exactly what leads so many of us to believe we could never afford to go vagabonding. The more our life options get paraded around as consumer options, the more we forget that there’s a difference between the two. Thus, having convinced ourselves that buying things is the only way to play an active role in the world, we fatalistically conclude that we’ll never be rich enough to purchase a long-term travel experience.

Fortunately, the world need not be a consumer product. As with environmental integrity, long-term travel isn’t something you buy into: it’s something you give to yourself.

As with environmental integrity, long-term travel isn’t something you buy into: it’s something you give to yourself.

Indeed, the freedom to go vagabonding has never been determined by income level, but through simplicity — the conscious decision of how to use what income you have.

And, contrary to popular stereotypes, seeking simplicity doesn’t require that you become a monk, a subsistence forager, or a wild-eyed revolutionary. Nor does it mean that you must unconditionally avoid the role of consumer. Rather, simplicity merely requires a bit of personal sacrifice: an adjustment of your habits and routines within consumer society itself.

“Our crude civilization engenders a multitude of wants… Our forefathers forged chains of duty and habit, which bind us notwithstanding our boasted freedom, and we ourselves in desperation, add link to link, groaning and making medicinal laws for relief.”

— John Muir, Kindred and Related Spirits

At times, the biggest challenge in embracing simplicity will be the vague feeling of isolation that comes with it, since private sacrifice doesn’t garner much attention in the frenetic world of mass culture.

Jack Kerouac’s legacy as a cultural icon is a good example of this. Arguably the most famous American vagabonder of the 20th century, Kerouac vividly captured the epiphanies of hand-to-mouth travel in books like On the Road and Lonesome Traveler. In Dharma Bums, he wrote about the joy of living with people who blissfully ignore “the general demand that they consume production and therefore have to work for the privilege of consuming, all that crap they didn’t really want…general junk you always see a week later in the garbage anyway, all of [it] impersonal in a system of work, produce, consume.”

Despite his observance of material simplicity, however, Kerouac found that his personal life – the life that had afforded him the freedom to travel – was soon overshadowed by a more fashionable (and marketable) public vision of his travel lifestyle. Convertible cars, jazz records, marijuana (and, later, Gap khakis), ultimately came to represent the mystical “It” that he and Neal Cassidy sought in On the Road. As his Beat cohort William S. Burroughs was to point out years after his death, part of Kerouac’s mystique became inseparable from the idea that he “opened a million coffee bars and sold a million pairs of Levi’s to both sexes.”

As his Beat cohort William S. Burroughs was to point out years after his death, part of Kerouac’s mystique became inseparable from the idea that he “opened a million coffee bars and sold a million pairs of Levi’s to both sexes.”

In some ways, of course, coffee bars, convertibles and marijuana are all part of what made travel appealing to Kerouac’s readers. That’s how marketing (intentional and otherwise) works. But these aren’t the things that made travel possible for Kerouac. What made travel possible was that he knew how neither self nor wealth can be measured in terms of what you consume or own. Even the downtrodden souls on the fringes of society, he observed, had something the rich didn’t: Time.

This notion – the notion that “riches” don’t necessarily make you wealthy – is as old as society itself. The ancient Hindu Upanishads refer disdainfully to “that chain of possessions wherewith men bind themselves, and beneath which they sink”; ancient Hebrew scriptures declare that “whoever loves money never has money enough. ” Jesus noted that it’s pointless for a man to “gain the whole world, yet lose his very self”, and the Buddha whimsically pointed out that seeking happiness in one’s material desires is as absurd as “suffering because a banana tree will not bear mangoes.”

” Jesus noted that it’s pointless for a man to “gain the whole world, yet lose his very self”, and the Buddha whimsically pointed out that seeking happiness in one’s material desires is as absurd as “suffering because a banana tree will not bear mangoes.”

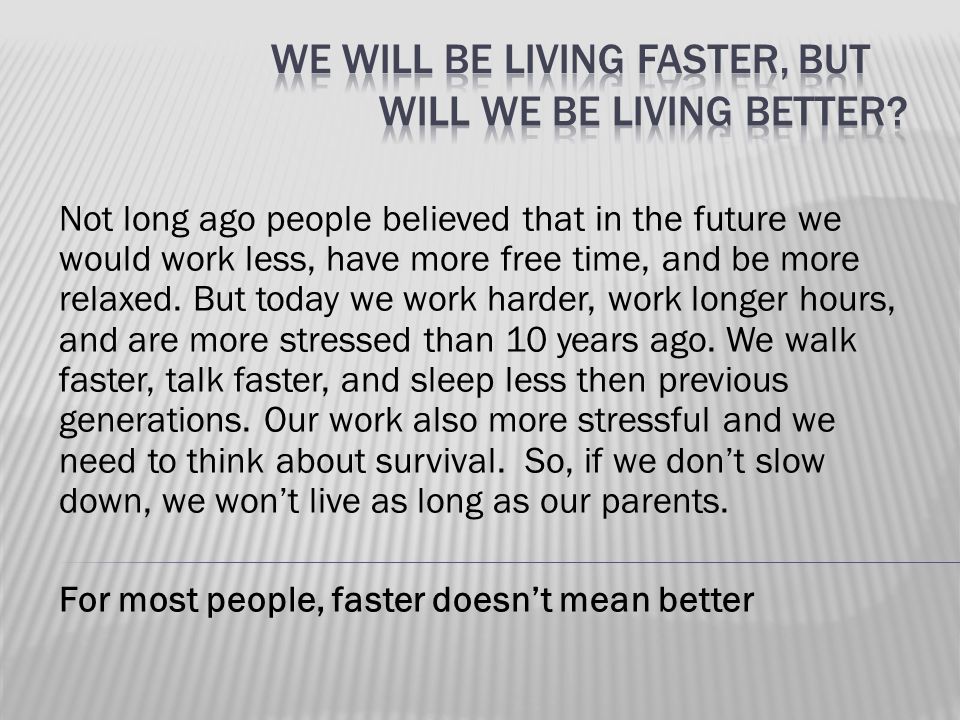

Despite several millennia of such warnings, however, there is still an overwhelming social compulsion – an insanity of consensus, if you will – to get rich from life rather than live richly, to “do well” in the world instead of living well. And, in spite of the fact that America is famous for its unhappy rich people, most of us remain convinced that just a little more money will set life right. In this way, the messianic metaphor of modern life becomes the lottery – that outside chance that the right odds will come together to liberate us from financial worries once and for all.

“Henceforth I ask not good-fortune, I myself am good-fortune,

Henceforth I whimper no more, postpone no more, need nothing…”

— Walt Whitman, “Song of the Open Road”

Fortunately, we were all born with winning tickets – and cashing them in is a simple matter of altering our cadence as we walk through the world. Vagabonding sage Ed Buryn knew as much: “By switching to a new game, which in this case involves vagabonding, time becomes the only possession and everyone is equally rich in it by biological inheritance. Money, of course, is still needed to survive, but time is what you need to live. So, save what little money you possess to meet basic survival requirements, but spend your time lavishly in order to create the life values that make the fire worth the candle. Dig?”

Vagabonding sage Ed Buryn knew as much: “By switching to a new game, which in this case involves vagabonding, time becomes the only possession and everyone is equally rich in it by biological inheritance. Money, of course, is still needed to survive, but time is what you need to live. So, save what little money you possess to meet basic survival requirements, but spend your time lavishly in order to create the life values that make the fire worth the candle. Dig?”

Dug. And the bonus to all of this is that – as you of sow your future with rich fields of time – you are also planting the seeds of personal growth that will gradually bloom as you travel into the world.

* * *

In a way, simplifying your life for vagabonding is easier than it sounds. This is because travel by its very nature demands simplicity. If you don’t believe this, just go home and try stuffing everything you own into a backpack. This will never work, because no matter how meagerly you live at home, you can’t match the scaled-down minimalism that travel requires. You can, however, set the process of reduction and simplification into motion while you’re still at home. This is useful on several levels: Not only does it help you to save up travel money, but it helps you realize how independent you are of your possessions and your routines. In this way, it prepares you mentally for the realities of the road, and makes travel a dynamic extension of the life-alterations you began at home.

You can, however, set the process of reduction and simplification into motion while you’re still at home. This is useful on several levels: Not only does it help you to save up travel money, but it helps you realize how independent you are of your possessions and your routines. In this way, it prepares you mentally for the realities of the road, and makes travel a dynamic extension of the life-alterations you began at home.

“Travel can be a kind of monasticism on the move: On the road, we often live more simply, with no more possessions than we can carry, and surrendering ourselves to chance. This is what Camus meant when he said that “what gives value to travel is fear” — disruption, in other words, (or emancipation) from circumstance, and all the habits behind which we hide.

— Pico Iyer, “Why We Travel”

As with, say, giving up coffee, simplifying your life will require a somewhat difficult consumer withdrawal period. Fortunately, your impending travel experience will give you a very tangible and rewarding long-term goal that helps ease the discomfort. Over time, as you reap the sublime rewards of simplicity, you’ll begin to wonder how you ever put up with such a cluttered life in the first place.

Fortunately, your impending travel experience will give you a very tangible and rewarding long-term goal that helps ease the discomfort. Over time, as you reap the sublime rewards of simplicity, you’ll begin to wonder how you ever put up with such a cluttered life in the first place.

On a basic level, there are three general methods to simplifying your life: stopping expansion, reining in your routine, and reducing clutter. The easiest part of this process is stopping expansion. This means that – in anticipation of vagabonding – you don’t add any new possessions to your life, regardless of how tempting they might seem. Naturally, this applies to things like cars and home entertainment systems, but this also applies to travel accessories. Indeed, one of the biggest mistakes people make in anticipation of vagabonding is to indulge in a vicarious travel buzz by investing in water filters, sleeping bags, and travel-boutique wardrobes. In reality, vagabonding runs smoothest on a bare minimum of gear – and even multi-year trips require little initial investment beyond sturdy footwear and a dependable travel bag or backpack.

While you’re curbing the material expansion of your life, you should also take pains to rein in the unnecessary expenses of your weekly routine. Simply put, this means living more humbly (even if you aren’t humble) and investing the difference into your travel fund. Instead of eating at restaurants, for instance, cook at home and pack a lunch to work or school. Instead of partying at nightclubs and going out to movies or pubs, entertain at home with friends or family. Wherever you see the chance to eliminate an expensive habit, take it. The money you save as a result will pay handsomely in travel time. In this way, I ate lot of baloney sandwiches (and missed out on a lot of grunge-era Seattle nightlife) while saving up for a vagabonding stint after college — but the ensuing eight months of freedom on the roads of North America more than made up for it.

“Very many people spend money in ways quite different from those that their natural tastes would enjoin, merely because the respect of their neighbors depends upon their possession of a good car and their ability to give good dinners.

As a matter of fact, any man who can obviously afford a car but genuinely prefers travels or a good library will in the end be much more respected than if he behaved exactly like everyone else.”

— Bertrand Russell, The Conquest of Happiness

Perhaps the most challenging step in keeping things simple is to reduce clutter – to downsize what you already own. As Thoreau observed, downsizing can be the most vital step in winning the freedom to change your life: “I have in my mind that seemingly wealthy, but most terribly impoverished class of all,” he wrote in Walden, “who have accumulated dross, but know not how to use it, or get rid of it, and thus have forged their own golden or sliver fetters.”

How you reduce your “dross” in anticipation of travel will depend on your situation. If you’re young, odds are you haven’t accumulated enough to hold you down (which, incidentally, is a big reason why so many vagabonders tend to be young). If you’re not-so-young, you can re-create the carefree conditions of youth by jettisoning the things that aren’t necessary to your basic well-being. For much of what you own, garage sales and on-line auctions can do wonders to unclutter your life (and score you an extra bit of cash to boot). Homeowners can win their travel freedom by renting out their houses; those who rent accommodation can sell, store, or lend out the things that might bind them to one place.

For much of what you own, garage sales and on-line auctions can do wonders to unclutter your life (and score you an extra bit of cash to boot). Homeowners can win their travel freedom by renting out their houses; those who rent accommodation can sell, store, or lend out the things that might bind them to one place.

An additional consideration in life-simplification is debt. As Laurel Lee wryly observed in Godspeed, “cities are full of those who have been caught in monthly payments for avocado green furniture sets.” Thus, if at all possible, don’t let avocado green furniture sets (or any other seemingly innocuous indulgence) dictate the course of your life by forcing you into ongoing cycles of production and consumption. If you’re already in debt, work your way out of it – and stay out. If you have a mortgage or other long-term debt, devise a situation (such as property rental) that allows you to be independent of its obligations for long periods of time. Being free from debt’s burdens simply gives you more vagabonding options.

And, for that matter, more life options.

* * *

“It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after your own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.”

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Self Reliance”

As you simplify your life and look forward to spending your new wealth of time, you’re likely to get a curious reaction from your friends and family. On one level, they will express enthusiasm for your impending adventures. But on another level, they might take your growing freedom as a subtle criticism of their own way of life. Because your fresh worldview might appear to call their own values into question (or, at least, force them to consider those values in a new light), they will tend to write you off as irresponsible and self-indulgent. Let them. As I’ve said before, vagabonding is not an ideology, a balm for societal ills, nor a token of social status. Vagabonding is, was, and always will be a private undertaking – and its goal is not to improve your life in relation to your neighbors, but in relation to yourself. Thus, if your neighbors consider your travels foolish, don’t waste your time trying to convince them otherwise. Instead, the only sensible reply is to quietly enrich your life with the myriad opportunities that vagabonding provides.

Vagabonding is, was, and always will be a private undertaking – and its goal is not to improve your life in relation to your neighbors, but in relation to yourself. Thus, if your neighbors consider your travels foolish, don’t waste your time trying to convince them otherwise. Instead, the only sensible reply is to quietly enrich your life with the myriad opportunities that vagabonding provides.

Interestingly, some of the harshest responses I’ve received in reaction to my vagabonding life have come while traveling. Once, at Armageddon (the site in Israel; not the battle at the end of the world), I met an American aeronautical engineer who was so tickled he had negotiated 5 days of free time into a Tel Aviv consulting trip that he spoke of little else as we walked through the ruined city. When I eventually mentioned that I’d been traveling around Asia for the past 18 months, he looked at me like I’d slapped him. “You must be filthy rich,” he said acidly. “Or maybe,” he added, giving me the once-over, “your mommy and daddy are. ”

”

I tried to explain how two years of teaching English in Korea had funded my freedom, but the engineer would have none of it. Somehow, he couldn’t accept that two years of any kind of honest work could have funded 18 months (and counting) of travel. He didn’t even bother sticking around for the real kicker: In those 18 months of travel, my day-to-day costs were significantly cheaper than day-to-day life would have cost me back in the United States.

The secret to my extraordinary thrift was neither secret nor extraordinary: I had tapped into that vast well of free time simply by forgoing a few comforts as I traveled. Instead of luxury hotels, I slept in clean, basic hostels and guesthouses. Instead of flying from place to place, I took local buses, trains, and share-taxis. Instead of dining at fancy restaurants, I ate food from street-vendors and local cafeterias. Occasionally, I traveled on foot, slept out under the stars, and dined for free at the stubborn insistence of local hosts.

In what ultimately amounted to over two years of travel in Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East, my lodging averaged out to just under $5 a night, my meals cost well under $1 a plate, and my total expenses rarely exceeded $1000 a month.

“When I was very young a big financier once asked me what I would like to do, and I said, ‘To travel.’ ‘Ah,’ he said, ‘it is very expensive; one must have a lot of money to do that.’ He was wrong. For there are two kinds of travelers; the Comfortable Voyager, round whom a cloud of voracious expenses hums all the time, and the man who shifts for himself and enjoys the little discomforts as a change from life’s routine.”

— Ralph Bagnold, Libyan Sands

Granted, I have simple tastes – and I didn’t linger long in expensive places – but there was nothing exceptional in the way I traveled. In fact, entire multi-national backpacker circuits (not to mention budget guidebook publishing empires) have been created by the simple abundance of such travel bargains in the developing world. For what it costs to fill your gas-tank back home, for example you can take a train from one end of China to the other. For the cost of a home-delivered pepperoni pizza, you can eat great meals for a week in Brazil. And, for a month’s rent in any major American city, you can spend a year in a beach hut in Indonesia. Moreover, even the industrialized parts of the world host enough hostel networks, bulk transportation discounts, and camping opportunities make long-term travel affordable.

For what it costs to fill your gas-tank back home, for example you can take a train from one end of China to the other. For the cost of a home-delivered pepperoni pizza, you can eat great meals for a week in Brazil. And, for a month’s rent in any major American city, you can spend a year in a beach hut in Indonesia. Moreover, even the industrialized parts of the world host enough hostel networks, bulk transportation discounts, and camping opportunities make long-term travel affordable.

Ultimately, you may well discover that vagabonding on the cheap becomes your favorite way to travel, even if given more expensive options. Indeed, not only does simplicity save you money and buy you time, it makes you more adventuresome, forces you into sincere contact with locals, and allows you the independence to follow your passions and curiosities down exciting new roads.

In this way, simplicity – both at home and on the road – affords you the time to seek renewed meaning in an oft-neglected commodity that can’t be bought at any price: life itself.

# # #

Resources for lifestyle simplicity

[Note from Tim: I took Walden with me, along with Vagabonding, when I traveled the world beginning in 2004. Less is More came a few months later, and I still reread it every six months or so.]

Walden, by Henry David Thoreau

The philosophical account of Thoreau’s experiment in anti-materialist living. An American literary classic for over 150 years.

Less Is More: The Art of Voluntary Poverty: An Anthology of Ancient and Modern Voices Raised in Praise of Simplicity, edited by Goldian Vandenbroeck (Inner Traditions, 1996)

Quotes and essays on the value of simplicity, from the likes of Socrates, Shakespeare, St. Francis, Benjamin Franklin, and Mohandas Gandhi — as well as the Bible, the Dhammapada, the Tao Te Ching, and the Bhagavad Gita.

Your Money or Your Life: 9 Steps to Transforming Your Relationship with Money and Achieving Financial Independence, by Joe Dominguez, Vicki Robin (Penguin USA, 2008)

A best-selling book that uses a nine-step process to demonstrate how most people are making a “dying” instead of a living. Practical pointers for achieving financial independence by altering your lifestyle.

Practical pointers for achieving financial independence by altering your lifestyle.

Voluntary Simplicity: Toward a Way of Life That Is Outwardly Simple, Inwardly Rich, by Duane Elgin (Quill, 1993)

First published in 1981, this is a popular reference and inspiration for those looking to live a simpler life. Strongly themed toward environmental sustainability.

The Simple Living Guide: A Sourcebook for Less Stressful, More Joyful Living, by Janet Luhrs (Broadway Books, 1997)

Luhrs is the founder and publisher of The Simple Living Journal (and the companion website). Book contains tips for living fully and well through simplicity.

Budgeting and money management

The Pocket Idiot’s Guide to Living on a Budget, by Peter J. Sander, Jennifer Basye Sander (Alpha Books, 2005)

A concise guide to planning and abiding by a day-to-day budget.

The Budget Kit: The Common Cents Money Management Workbook, by Judy Lawrence (Kaplan, 2008)

Easy-to-use tips for managing your finances and getting the most out of your income.

The Complete Tightwad Gazette: Promoting Thrift As a Viable Alternative Lifestyle by Amy Dacyczyn (Random House, 1999)

Nine hundred pages of compiled tips for frugal living.

How to Get Out of Debt, Stay Out of Debt, and Live Prosperously, by Jerrold Mundis (Bantam, 2003)

This book helps you get out of debt, stay out of debt, and live prosperously.

Generation Debt: Take Control of Your Money, Carmen Wong Ulrich (Business Plus, 2006)

Personal financial advice for young adults.

The Dollar Stretcher

An online resource for saving money in day-to-day life. Weekly columns on thrift and simplicity.

Get Rich Slowly

A detailed blog with personal finance tips.

Vagabonding for seniors

Exploritas

The world’s largest educational and travel organization for adults 55 and over. Offers 10,000 programs a year in over 100 countries. A good way for traveling seniors to get a taste of other cultures before striking off on their own.

State Department Travel Tips for Older Americans

Posted online, this tip sheet is a useful primer for older independent travelers. Topics covered include trip preparation, passport and visas, health, money and valuables, safety precautions, and shopping.

Transitions Abroad’s Best Senior Travel Websites

Extensive rundown of links, resources and articles about senior travel.

Lonely Planet’s older travelers’ forum

An online message board for senior travelers.

AARP Travel

Products, services and discounts for travelers aged 50 and over.

Boomeropia

Online travel resources for Baby Boomers.

Vagabonding with children

Lonely Planet Travel With Children, by Cathy Lanigan (Lonely Planet, 2002)

A practical guide to the challenges and joys of traveling with children, including trip preparation and kid-friendly destinations.

Gutsy Mamas: Travel Tips and Wisdom for Mothers on the Road, by Marybeth Bond (Travelers’ Tales, 1997)

Inspirational and informative advice on staying healthy on the road, traveling to third world countries (and close to home), and keeping children of all ages entertained and adults energized.

Your Child Abroad: A Travel Health Guide, by Jane Wilson-Howarth, Matthew Ellis. (Bradt Publications, 2005)

Accessible and practical health information for parents traveling with children to far-flung areas of the world.

One Year Off: Leaving It All Behind for a Round-the-World Journey with Our Children, by David Elliot Cohen (Simon & Schuster, 1999)

When David Elliot Cohen turned 40, he quit his job, sold his house and car and left to travel the world — with his wife and three kids (aged 8, 7, and 2) in tow. A first-hand account of how vagabonding exotic lands can be a family experience.

Take Your Kids to Europe: How to Travel Safely (and Sanely) in Europe with Your Children, by Cynthia Harriman (Globe Pequot, 2007)

A book of practical tips for traveling families traveling to Europe on limited budgets.

Adventuring With Children: An Inspirational Guide to World Travel and the Outdoors, by Nan Jeffrey (Avalon, 1995)

A classic book of advice on roaming the world with children, including preparation tips and adventurous family destinations.

Family Travel: The Farther You Go, the Closer You Get, by Laura Manske (Travelers’ Tales, 2000)

A collection of literary tales about family travel.

The Family Sabbatical Handbook: The Budget Guide To Living Abroad With Your Family, by Elisa Bernick (Intrepid Traveler, 2007)

Advice for families considering an expatriate stint abroad.

WorldTrek: A Family Odyssey, by Russell and Carla Fisher (Rainbow Books, 2007)

A family of four spends a year traveling the world.

Family Travel Forum

Online information on worldwide destinations for adults and children. Features discussion boards and advice for all manner of family travel issues.

Traveling Internationally With Your Kids

Online resources for traveling overseas with children. Features guidebook recommendations, trip preparation tips, and activity suggestions.

Delicious Baby

Ideas and stories about how to make travel fun for kids.

Families on the Road

For families who are on the road fulltime, on extended road trips, or are just dreaming about it.

Boostnall Traveling with Children forum

An online message board where family travelers can ask questions and share information.

Lonely Planet’s Kids to Go

Another useful online family-travel message board.

Pilgrims’ Progress

A Kiwi family with eight kids and a grandpa chronicle their pilgrimage from Singapore to London and beyond — overland all the way.

Traveling with Elliot

A blog documenting parent-child travel around the globe.

Six in the World

A family of six, ranging in age from 38 to 4, embarked on an 11-month round-the-world adventure in August 2006. This blog tracks their preparation, travels, and return to the US.

(A version of this post originally appeared as Chapter 3 in Vagabonding by Rolf Potts)

The Tim Ferriss Show is one of the most popular podcasts in the world with more than 900 million downloads. It has been selected for "Best of Apple Podcasts" three times, it is often the #1 interview podcast across all of Apple Podcasts, and it's been ranked #1 out of 400,000+ podcasts on many occasions. To listen to any of the past episodes for free, check out this page.

To listen to any of the past episodes for free, check out this page.

"Who should live well in Rus'" the meaning of Nekrasov's poem, meaning

In 1866, the prologue of Nekrasov's poem "Who Lives Well in Rus'" appears in print. This work, published three years after the abolition of serfdom, immediately caused a wave of discussion. Leaving aside the political criticism of the poem, let's focus on the main question: what is the meaning of the poem "Who should live well in Rus'"?

Of course, partly Nekrasov's impetus for writing the poem was the reform of 1861. Russia, which had lived for centuries at the expense of the labor of serfs, was reluctant to get used to the new system. Everyone was at a loss: both the landlords and the serfs themselves, which Nekrasov masterfully portrays in his poem. The first simply did not know what to do now: accustomed to living exclusively by other people's labor, they were not adapted to an independent life. They sing to the landowner: Work hard, but he “thought to live like this for a century” and is no longer ready to reorganize in a new way. For some, such a reform is literally like death - the author shows this in the chapter "Last Child". Prince Utyatin, her main character, has to be deceived until his death, claiming that serfdom in Rus' is still in effect. Otherwise, the prince will have a blow - the shock will be too strong.

They sing to the landowner: Work hard, but he “thought to live like this for a century” and is no longer ready to reorganize in a new way. For some, such a reform is literally like death - the author shows this in the chapter "Last Child". Prince Utyatin, her main character, has to be deceived until his death, claiming that serfdom in Rus' is still in effect. Otherwise, the prince will have a blow - the shock will be too strong.

The peasants are also confused. Yes, some of them dreamed of freedom, but soon they are convinced that they received the rights only on paper:

“You are good, royal letter,

Yes, you were not written with us ...”

The village of Vahalaki has been suing for years for its lawful meadows on the Volga with the former owners of the land, the landowners, but it is clear that the peasants will not see this land during their lifetime.

There is another type of peasant - those who were taken by surprise by the abolition of serfdom. They are accustomed to pleasing their landowner and treat him as an inevitable and necessary evil for life, moreover, they cannot imagine their life without him. “You have fun!

They are accustomed to pleasing their landowner and treat him as an inevitable and necessary evil for life, moreover, they cannot imagine their life without him. “You have fun!

Such is the serf, proud of the fact that all his life he drank and ate after the master. Faithful serf Yakov, who gave his whole life to an absurd master, on the contrary, decides to rebel. But let's see how this rebellion is expressed - in depriving oneself of life in order to leave the landowner alone, helpless. This, as it turned out, is an effective revenge, but it will no longer help Yakov ...

According to Nekrasov's plan, the meaning of "Who should live well in Rus'" was precisely the depiction of the country immediately after the abolition of serfdom from various points of view. The poet wanted to show that the reform was carried out largely thoughtlessly and inconsistently, and brought with it not only the joy of liberation, but also all sorts of problems that needed to be addressed. Poverty and lack of rights, a huge lack of education for the common people (the only school in the village is "crammed tightly"), the need for honest and smart people who would hold responsible positions - all this is said in the poem in a simple, folk language. Rus itself seems to speak with the reader in many voices, begging for help.

Poverty and lack of rights, a huge lack of education for the common people (the only school in the village is "crammed tightly"), the need for honest and smart people who would hold responsible positions - all this is said in the poem in a simple, folk language. Rus itself seems to speak with the reader in many voices, begging for help.

At the same time, it would be wrong to reduce the meaning of the work "To whom it is good to live in Rus'" exclusively to consideration of the current political problems of Russia. No, when creating the poem, Nekrasov put into it a different, philosophical meaning. It is already expressed in the very title of the poem: “Who in Rus' should live well”.

And really, to whom? - this is the problem that the author, and with him the reader, has to solve. Peasants in their wanderings will ask a variety of people, from a priest to a simple soldier, but none of their interlocutors can boast of happiness. And this is to some extent natural, because each of the heroes of the poem is looking for his own, personal happiness, without thinking about the universal, the people. Even the honest burgomaster Yermil cannot stand it and, in an attempt to benefit his family, forgets about the truth. Happiness, according to Nekrasov, can only be found by those who forget about personal things and take care of the happiness of their homeland, as Grisha Dobrosklonov does.

Even the honest burgomaster Yermil cannot stand it and, in an attempt to benefit his family, forgets about the truth. Happiness, according to Nekrasov, can only be found by those who forget about personal things and take care of the happiness of their homeland, as Grisha Dobrosklonov does. “Nekrasov, in his last work, remained true to his idea: to arouse the sympathy of the upper classes of society for the common people, their needs and needs,” the Russian critic Belinsky spoke of Nekrasov’s work. And indeed, this is the main meaning of the poem “To whom it is good to live in Rus'” - not only and so much to point out current problems, but to affirm the desire for universal happiness as the only possible way for the further development of the country.

See what else we have:

Product test

Hall of Honor

To get here - pass the test.

The meaning of the poem To whom in Rus' to live well essay

- Works /

- Literature /

- Meaning of the poem Who should live well in Rus'

In his lyrical-epic work “Who Lives Well in Rus'”, Nekrasov raises a very relevant topic for that period: he explains what happened to Russian peasants after the adoption of decrees on the abolition of serfdom. After all, neither the homesteaders themselves nor their former owners know what to do next.

How to live? After all, it was clear to many that the law was adopted ill-considered, with many mistakes. So the peasants gather and go to seek the truth. Reading the poem, it seems that their homeland itself is asking for help. Walking along the roads, ravines and gullies of villages and villages, the peasants question everyone they meet along the way. The stories of passers-by not only do not please them, but in many ways frighten them.

The stories of passers-by not only do not please them, but in many ways frighten them.

People live poorly, work hard, are oppressed and plundered by the rich. But everyone wants a good life, joy and good luck. The author explains that only those who give their personal grace for the well-being of others can be happy in Russia. Different people whom the author brought to the "stage" with different qualities and hopes, they wander through the open spaces and think about what happiness is and who deserves it.

These thoughts excite them, they are the meaning of not only the poem, but the very life of the working people. None of the seven peasants who, in the Prologue chapter, start a conversation about good, evil, happiness, sees its global significance. For them, it is about material well-being. In the “Happy” part, it seems that there seems to be a gap and there is someone who considers himself lucky. And a new one, for Russian literature of that time, is a hero, Dobrosklonov, who promises that other times will come and new people will come who will help the poor. But for now, their journey will most likely end in Siberia.

But for now, their journey will most likely end in Siberia.

In the chapters “Peasant Woman”, “Last Child” and the main part “A Feast for the Whole World”, “Good Time”, Nikolai Alekseevich describes many advantages and disadvantages of society. This work gives hope to everyone and everyone. No wonder he reveals this topic, but the meaning of the work, displays it in the title and tries to predict how this problem will be solved. Nekrasov idealizes his heroes a little. All the artistic, expressive means that he attracts help him create a picture of the life of the whole people, their aspirations and hopes. But he, like the peasants, hopes that a country with a strong spirit will come to changes that will change and give it free and happy people. The country has strength, faith and hope for happiness.

Others:← Oblomov's upbringing and education ↑ Literature Life and customs of the city of Kalinov in the play Thunderstorm Ostrovsky →

The meaning of the poem To whom it is good to live in Rus' Now they are reading:

The long-awaited weekend ended very quickly. As usual, I had to collect all the school supplies in the evening by Monday. With a good mood and cheerful spirit before the new school week, I went to bed,

As usual, I had to collect all the school supplies in the evening by Monday. With a good mood and cheerful spirit before the new school week, I went to bed,

Go to the shore of a lake or river and look into its surface. There you can see the meaning of all life, feel how small and insignificant you are compared to this beautiful and dangerous element. Enter the water, feel it pass through you

The artist Stanislav Zhukovsky was considered a singer of manor motifs, and he also loved autumn very much. It was the time of his inspiration. In his work "Autumn. Veranda

Art is a form of social consciousness or a sphere of culture, without which it is impossible to imagine the life of mankind. Through art, a person tries to creatively reflect his worldview, express feelings and thoughts, as well as learn, evaluate the world,

V.