Words that rhyme with constant

242 best rhymes for 'constant'

1 syllable

- Stunt

- Cunt

- Blunt

- Hunt

- Front

- Stunned

- And

- Und

- Dump

- Dust

- Pump

- Bump

- Bust

- Touched

- Punt

- Lust

- Must

- Just

- Punk

- Loved

- Jump

- Crushed

- Trust

- Shoved

- Shunned

- Tucked

- Sucked

- Fucked

- Stuffed

- Trunk

- Drunk

- Bunt

- Gunned

- Shunt

- Funk

- Grunt

- Rust

- Fund

- Tunde

- Rushed

- Dunk

- Munt

- Glunt

- Brunt

- Kunde

- Trump

- Chump

- Junk

- Thump

- Stump

- Thunk

- Skunk

- Mund

- Slump

- Lund

- Runde

- Hund

- Duct

- Crust

- Grund

- Thrust

- Hump

- Lump

- Sunk

- Tongued

- Cussed

- Cup

- Flushed

- Gump

- Buzzed

- Bummed

- Gust

- Dusk

- Judged

- Bunk

- Cuffed

- Thumbed

- Yup

- Stunk

- Cult

- Numbed

- Upped

- Brushed

- Spunk

- Hulk

- Gushed

- Hushed

- Blushed

- Gummed

- Summed

- Plump

- Bucked

- Rump

- Puffed

- Shut

- Cut

- Up

- But

- Clump

- Gloved

- Cusp

- Monk

- Sump

- Chunk

- Pulp

- Fussed

- Hust

- Stuck

- What

- Gut

- Nut

- Grump

- Crump

- Brust

- Shucked

- Crunk

- Shunk

- Flunk

- Plucked

- Tusk

- Clutched

- Drugged

- Scuffed

- Stubbed

2 syllables

- Wasn't

- Arent

- Product

- Darkened

- Contant

- Hardened

- Sharpened

- Ardent

- Sergeant

- Solvent

- Convent

- Instant

- Potent

- Distant

- Smartened

- Heartened

- Parchment

- Pardoned

- Garment

- Didn't

- Student

- Couldn't

- Wouldn't

- Tallent

- Galant

- Quadrant

- Isn't

- Doesn't

- Present

- Haven't

- Bargained

- Scotland

- Almond

- Holland

- Pregnant

- Auckland

- Garland

- Rolland

- Bottled

- Decent

- Silent

- Violent

- Pavement

- Basement

- Talent

- Opened

- Happened

- Moment

- Movement

- Ancient

- Donald

- Shouldn't

- Statement

- Different

- Current

- Giant

- Second

- Thousand

- Bottomed

- Conduct

- Stardust

- Vacant

- Legend

- Island

- Diamond

- Listened

- Blatant

- Judgement

- Construct

- Blossomed

- Ruined

- Pleasant

- Peasant

- Startled

- Serpent

- Frightened

- Parent

3 syllables

- Apartment

- Despondent

- Department

- Retardant

- Respondent

- Insolvent

- Disheartened

- Important

- Compartment

- Involvement

- Bombardment

- Covalent

- President

- Enlargement

- Allotment

- Evident

- Confident

- Government

- Innocent

- Accident

- Permanent

- Ignorant

- Opponent

- Relevant

- Abandoned

- Arrogant

- Persistent

- Misconduct

- Byproduct

- Consistent

- Hesitant

- Elephant

- Militant

- Element

4 syllables

- Correspondent

- Irrelevant

- Independent

- Intelligent

- Omnipotent

- Equivalent

- Entertainment

Want to find rhymes for another word? Try our amazing rhyming dictionary.

If you write lyrics you should definitely check out RapPad. It has tons of useful features for songwriters, lyricists, and rappers.

Near rhymes with constantB-Rhymes | B-Rhymes

| Word | Pronunciation | Score ? | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | inconstant | inkons_tuhn_t | 3640 | Definition |

| 2 | correspondent | koris_ponduhn_t | 3628 | Definition |

| 3 | despondent | dis_ponduhn_t | 3628 | Definition |

| 4 | respondent | ris_ponduhn_t | 3628 | Definition |

| 5 | convent | konvuhn_t | 3591 | Definition |

| 6 | fondant | fonduhn_t | 3562 | Definition |

| 7 | secondment | sekon_dmuhn_t | 3521 | Definition |

| 8 | cantonment | kaantonmuhn_t | 3518 | Definition |

| 9 | abundant | uhbanduhn_t | 3495 | Definition |

| 10 | redundant | ridanduhn_t | 3495 | Definition |

| 11 | recumbent | rikambuhn_t | 3481 | Definition |

| 12 | incumbent | inkambuhn_t | 3481 | Definition |

| 13 | atonement | uhtuh_uunmuhn_t | 3453 | Definition |

| 14 | microenvironment | mah_ik_ruh_uuenvah_iruhnmuhn_t | 3420 | Definition |

| 15 | environment | envah_iruhnmuhn_t | 3420 | Definition |

| 16 | enthronement | enth_ruh_uunmuhn_t | 3415 | Definition |

| 17 | important | impawrtuhn_t | 3413 | Definition |

| 18 | accordant | uhkawrduhn_t | 3407 | Definition |

| 19 | discordant | diskawrduhn_t | 3407 | Definition |

| 20 | concordant | konkawrduhn_t | 3407 | Definition |

| 21 | triumphant | t_rah_iamfuhn_t | 3407 | Definition |

| 22 | enlightenment | enlah_ituhnmuhn_t | 3405 | Definition |

| 23 | imprisonment | imp_rizuhnmuhn_t | 3405 | Definition |

| 24 | apportionment | uhpawrshuhnmuhn_t | 3392 | Definition |

| 25 | reapportionment | riuhpawrshuhnmuhn_t | 3392 | Definition |

| 26 | pungent | panjuhn_t | 3389 | Definition |

| 27 | impotent | impuhtuhn_t | 3383 | Definition |

| 28 | solvent | solvuhn_t | 3378 | Definition |

| 29 | insolvent | insolvuhn_t | 3378 | Definition |

| 30 | impudent | imp_yuhduhn_t | 3374 | Definition |

| 31 | appointment | uhpo_in_tmuhn_t | 3367 | Definition |

| 32 | disappointment | disuhpo_in_tmuhn_t | 3367 | Definition |

| 33 | poignant | po_inyuhn_t | 3367 | Definition |

| 34 | mordant | mawrduhn_t | 3366 | Definition |

| 35 | executant | egzekyuhtuhn_t | 3345 | Definition |

| 36 | quotient | k_wuh_uushuhn_t | 3344 | Definition |

| 37 | occupant | okyuhpuhn_t | 3335 | Definition |

| 38 | involvement | invol_vmuhn_t | 3335 | Definition |

| 39 | adjutant | aajuhtuhn_t | 3330 | Definition |

| 40 | omnipotent | omnipuhtuhn_t | 3330 | Definition |

| 41 | torrent | toruhn_t | 3328 | Definition |

| 42 | absorbent | aabsawrbuhn_t | 3327 | Definition |

| 43 | resultant | rizaltuhn_t | 3325 | Definition |

| 44 | exultant | egzaltuhn_t | 3325 | Definition |

| 45 | reluctant | rilaktuhn_t | 3321 | Definition |

| 46 | grandiloquent | g_raandiluhk_wuhn_t | 3320 | Definition |

| 47 | eloquent | eluhk_wuhn_t | 3320 | Definition |

| 48 | decadent | dekuhduhn_t | 3320 | Definition |

| 49 | stuyvesant | s_tah_ivuhsuhn_t | 3316 | Definition |

| 50 | accountant | uhkah_uuntuhn_t | 3315 | Definition |

| 51 | ointment | o_in_tmuhn_t | 3314 | Definition |

| 52 | entanglement | entaangguhlmuhn_t | 3313 | Definition |

| 53 | arrogant | aaruhguhn_t | 3310 | Definition |

| 54 | elegant | eluhguhn_t | 3310 | Definition |

| 55 | celebrant | seluhb_ruhn_t | 3310 | Definition |

| 56 | inelegant | ineluhguhn_t | 3310 | Definition |

| 57 | extravagant | iks_t_raavuhguhn_t | 3310 | Definition |

| 58 | immigrant | imuhg_ruhn_t | 3310 | Definition |

| 59 | wonderment | wanduhrmuhn_t | 3310 | Definition |

| 60 | bewilderment | biwilduhrmuhn_t | 3310 | Definition |

| 61 | encroachment | enk_ruh_uuchmuhn_t | 3308 | Definition |

| 62 | recusant | rekyuhzuhn_t | 3307 | Definition |

| 63 | student | s_t_yuuduhn_t | 3305 | Definition |

| 64 | carpenter | karrpuh_uhn_t_r | 3302 | Definition |

| 65 | innocent | inuhsuhn_t | 3301 | Definition |

| 66 | consultant | kuhnsaltuhn_t | 3297 | Definition |

| 67 | comportment | kompawr_tmuhn_t | 3295 | Definition |

| 68 | installment | ins_tawlmuhn_t | 3295 | Definition |

| 69 | deportment | dipawr_tmuhn_t | 3295 | Definition |

| 70 | elephant | eluhfuhn_t | 3292 | Definition |

| 71 | dormant | dawrmuhn_t | 3291 | Definition |

| 72 | adornment | uhdawr_nmuhn_t | 3291 | Definition |

| 73 | endorsement | endawr_smuhn_t | 3291 | Definition |

| 74 | warrant | woruhn_t | 3290 | Definition |

| 75 | quadrant | k_wodruhn_t | 3288 | Definition |

| 76 | instant | ins_tuhn_t | 3281 | Definition |

| 77 | relevant | reluhvuhn_t | 3281 | Definition |

| 78 | adjuvant | aajuhvuhn_t | 3281 | Definition |

| 79 | irrelevant | ireluhvuhn_t | 3281 | Definition |

| 80 | proportioned | p_ruhpawrshuhn_d | 3280 | Definition |

| 81 | delinquent | dilingk_wuhn_t | 3277 | Definition |

| 82 | pollutant | puhluutuhn_t | 3276 | Definition |

| 83 | government | gavuhrmuhn_t | 3275 | Definition |

| 84 | allotment | uhlotmuhn_t | 3272 | Definition |

| 85 | lodgment | lojmuhn_t | 3272 | Definition |

| 86 | enrollment | enruh_uulmuhn_t | 3270 | Definition |

| 87 | covent | kovuhn_t | 3269 | Definition |

| 88 | vincent | vinsuhn_t | 3268 | Definition |

| 89 | excrement | eks_k_ruhmuhn_t | 3268 | Definition |

| 90 | deodorant | deeuh_uuduhruhn_t | 3265 | Definition |

| 91 | preponderant | p_riponduhruhn_t | 3265 | Definition |

| 92 | protuberant | p_ruht_yuubuhruhn_t | 3265 | Definition |

| 93 | exuberant | egz_yuubuhruhn_t | 3265 | Definition |

| 94 | aberrant | aabuhruhn_t | 3265 | Definition |

| 95 | testament | testuhmuhn_t | 3264 | Definition |

| 96 | accoutrement | uhkuut_ruhmon_t | 3264 | Definition |

| 97 | argument | arrg_yuhmuhn_t | 3264 | Definition |

| 98 | instrument | ins_t_ruhmuhn_t | 3264 | Definition |

| 99 | temperament | temp_ruhmuhn_t | 3264 | Definition |

What is B-Rhymes?

B-Rhymes is a rhyming dictionary that's not stuck up about what does and doesn't rhyme. As well as regular rhymes, it gives you words that sound good together even though they don't technically rhyme.

As well as regular rhymes, it gives you words that sound good together even though they don't technically rhyme.

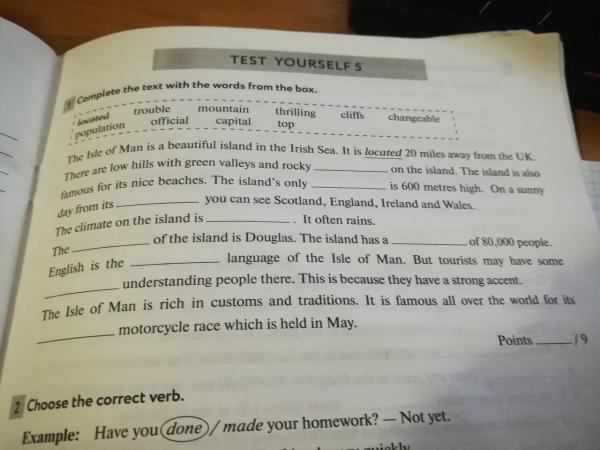

Make up a dictionary of your own rhymes for any of the given words exact, rattle, night, squirrel, bird, book

Answer or solution2

K

Rhyme is an important feature of poetic speech. Let's analyze this concept in more detail and give some examples of rhymes.

What is rhyme

The name "rhyme" goes back to the Greek language, from which this word is translated as "measurement" or "rhythm". Most literary scholars define rhyme as the consonance of the endings of two or more words. Thus, words can form rhyming pairs with each other, which is used successfully in poetic texts.

It is important that representatives of different parts of speech can rhyme, i.e. grammatical features in no way affect the ability of words to rhyme.

There are several ways to classify rhymes. The first one is related to the place of stress in rhyming words. The two main varieties in this situation are masculine (stress falls on the last syllable, for example: no - answer) and feminine (stress falls on the penultimate syllable, for example: cloud - little thing).

The two main varieties in this situation are masculine (stress falls on the last syllable, for example: no - answer) and feminine (stress falls on the penultimate syllable, for example: cloud - little thing).

In addition, exact and inexact types of rhymes are also distinguished. In the first case, the endings of a pair of words completely coincide with each other phonetically, while in the second, there may be some discrepancies between them (for example, one word may end in a vowel, and the second in a combination of vowel + [й]).

In order to facilitate the selection of rhyming pairs, there are special rhyming dictionaries that already contain words of different parts of speech with the same endings.

Examples of rhymes

Having determined what a rhyme is and what features it has, let's give examples of rhymes for the word "night":

- Daughter.

- Bump.

- Kidney.

- Kvochka (colloquial name for chicken).

- Point.

- Lobe (soft part of the ear).

- Barrel.

- Single.

All the rhymes listed above are nouns in the nominative case. However, the rhyming pair does not have to be in the initial form. By the word "night" you can also pick up rhymes in the form of nouns in the form of a singular, masculine, genitive case. For example:

- Bell.

- Puppy.

- Son.

- Lock.

- Piece.

- Leaf.

At the same time, there will be much more rhyming words in the second group.

K

Precise - juicy, durable, urgent, floral, durable, extracurricular, stock, lowercase.

Rattle - toy, drying, feeder, humpback, frog, spinner, skull, freckle, spinner.

Night - a line, a bump, a kidney, a dot, a shirt, a chain, a lobe, a daughter, a cheek.

Squirrel - arrow, plate, wall.

Bird - kitty, skirmish, particle, match, master key, plug, titmouse, technical, strawberry, eyelash.

Book - haircut, latch, movement, affair, latch, stalk, ankle.

Do you know the answer?

How to write a good answer? How to write a good answer?

Be careful!

- Copying from other sites is prohibited. Stickers and gifts for such answers are not awarded. Use your knowledge. :)

- Only detailed explanations are published. The answer cannot be less than 50 characters!

0 /10000

Mayakovsky's rhyme - Questions of Literature

M. Shtokmar, Mayakovsky's rhyme "Soviet writer", M. 1958, 145 pp. The researcher has done a huge and painstaking work on the study of Mayakovsky's rhyme, which testifies to the sharp eyesight of a scientist-analyst, who thoughtfully selects the necessary facts. The book has obvious merits - wide attraction and novelty of the material, new interesting conclusions about Mayakovsky's poetic technique.

M. Shtokmar points to the role of Mayakovsky's acoustic (or, as he calls it, orthoepic) principle of rhyming, in which the poet used "quite real sound coincidences that previously remained out of poetic use as a result of the difference in spelling" (p. 30).

30).

Attempts to classify Mayakovsky's rhymes were made even before the study of M. Stockmar (for example, B. Tomashevsky), but such a detailed technological classification was not in the literature of poetry, and its development is the undoubted merit of M. Stockmar.

It seems justified that the researcher introduces new terms to denote previously little-known concepts: “variation” rhyme (p. 14), “sprayed” rhyme (p. 47), “initial-middle” rhyme (p. 90), “total” rhyme (p. 96), etc. It should be noted that the existence of new concepts has been proven on the basis of rich factual material (for example, the analysis of echoic rhyme on pp. 17–22).

M. Stockmar seeks to comprehend not only the consonance of endings; he attaches an important role to the analysis of euphony and the instrumentation of verse, showing how closely the various elements of the verse structure are closely connected. Completely new in the Mayakovo literature is the conclusion about the "preparation of rhyme" in the poet's verse, which the researcher came to. Using a large amount of poetic material, he proved that "in Mayakovsky's poems, the "sound preparation" of rhyme from afar, even within a line of poetry, acquires special significance" (p. 51).

Using a large amount of poetic material, he proved that "in Mayakovsky's poems, the "sound preparation" of rhyme from afar, even within a line of poetry, acquires special significance" (p. 51).

As can be seen from what has been said, the book advances the study of not only Mayakovsky's rhyme, but Russian rhyme in general. And yet, despite the obvious advantages, the work does not cause complete satisfaction. This happens for two reasons. The first (not the main one) is that M. Shtokmar's book is sometimes devoid of internal harmony and unity. So, for example, the reasons for the emergence of new types of Mayakovsky's rhyme are revealed in several places (pp. 23 - 28, 105 - 107), the poet's innovation in the use of the pre-stressed part of rhyming words is said on pages 30 and 60, etc.

The main reason for dissatisfaction with the book, in my opinion, is that the author has chosen an aspect of research that does not fully reflect the achievements of Soviet literary criticism in the analysis of verse, although the methodology for analyzing poetic technique is original.

For the most part, he takes the linguo-technological aspect of the study, characteristic of Soviet versification of the 20s, in which the prevailing attention is paid to the technological aspects of verse (changes in individual sounds in rhyme, etc.) and, to a certain extent, underestimates the aesthetic understanding of the material . I say "predominantly" because there is also an aesthetic aspect in the work (an attempt to comprehend Mayakovsky's innovation in the field of verse, an analysis of transfers - on pp. 131 - 132, etc.).

The best works of Soviet versifiers are characterized by the aesthetic and technological aspect of the study, which consists in understanding how the individual components of the verse (rhythm, rhyme, etc.) are connected with the poetic content, contribute to its expression, being at the same time elements of the poetic technology with its own rules.

What has been said can be demonstrated by the author's analysis of a compound rhyme. M. Shtokmar carefully traces each technological change on a large number of examples. One would not have to object to this if the author paid more attention to the aesthetic understanding of Mayakovsky's rhymes. Sometimes a researcher simply states a fact, without convincingly proving the stated position: “In cases where Mayakovsky achieves special semantic emphasis, he decomposes the combination (meaning a close phrase. - B.G. .) into component parts and rhymes each of them separately” (p. 84). Seven quatrains are cited to support this position, but none of them has been analyzed. And the reader wants to get an answer to the question: how does semantic expressiveness manifest itself? It awaits concrete analysis.

M. Shtokmar carefully traces each technological change on a large number of examples. One would not have to object to this if the author paid more attention to the aesthetic understanding of Mayakovsky's rhymes. Sometimes a researcher simply states a fact, without convincingly proving the stated position: “In cases where Mayakovsky achieves special semantic emphasis, he decomposes the combination (meaning a close phrase. - B.G. .) into component parts and rhymes each of them separately” (p. 84). Seven quatrains are cited to support this position, but none of them has been analyzed. And the reader wants to get an answer to the question: how does semantic expressiveness manifest itself? It awaits concrete analysis.

In another place, the author makes an interesting claim - to analyze how rhyming words are compared on the grounds of direct correspondence and opposite meaning. After a brief statement on two pages (26, 28), examples of individual rhymes taken out of context follow (although just now, on page 25, the author recalled the role of context). When the reader looks through the lists of rhymes, he may have perplexed questions: what, for example, is the ratio of the rhymes "samo - Komsomol", "eye - stengaz" (p. 27). What is it - correspondence or opposite? Or maybe neither?

When the reader looks through the lists of rhymes, he may have perplexed questions: what, for example, is the ratio of the rhymes "samo - Komsomol", "eye - stengaz" (p. 27). What is it - correspondence or opposite? Or maybe neither?

The predominant adherence to the linguo-technological aspect of the analysis led to the fact that the most important problems of Mayakovsky's rhyme did not receive full coverage. The author did not pay due attention to the semantic expressiveness of the poet's rhymes.

It seems that when analyzing the semantic meaning of Mayakovsky's rhyme, one should be guided by the following premises: to approach each example concretely; do not necessarily try to "squeeze out" a certain semantic meaning from each rhyme. It should be borne in mind that the most important words in terms of meaning are by no means always necessarily placed at the end of the line. It's poetic tendency, therefore, only with a specific analysis can one find out what semantic meaning this or that rhyme has.

Two cases are possible. Firstly, rhyme, correlating various concepts during repetition, linking them in our minds with a sound call, contributes to the expression of the main thoughts contained in certain stanzas. In this case, a kind of “echo” of the main idea of the stanza is formed in the rhyme, because additional attention is drawn to the words put in rhyme. Concepts do not always collide according to the principle of correspondence, similarity or opposition. In some rhyming words, the concepts are not opposite, but mutually exclusive.

Rhyme cannot directly express certain concepts, it only has the ability to fix them in consonance and thus make people pay attention to them. Of course, to a large extent, the correlation of concepts would occur even without rhyme, but rhyme helps, promotes such a correlation. Concepts very rarely correlate in a straight line, without associativity.

Secondly, another poetic tendency is manifested to a greater extent, when the “focus” of the main idea of the stanza is, as it were, formed in the rhyme. This tendency is expressed in the fact that words collide in rhyme, the most important in the meaning of the given stanza, bearing the main semantic load. Again, a strictly concrete approach is needed, because sometimes rhymes contain words that do not carry a semantic load, and an attempt at analysis in this case can lead to vulgar sociologism. Sometimes these two tendencies merge.

This tendency is expressed in the fact that words collide in rhyme, the most important in the meaning of the given stanza, bearing the main semantic load. Again, a strictly concrete approach is needed, because sometimes rhymes contain words that do not carry a semantic load, and an attempt at analysis in this case can lead to vulgar sociologism. Sometimes these two tendencies merge.

Another important problem remained without a satisfactory answer - the reason for the emergence of new types of Mayakovsky's rhyme.

M. Shtokmar tries to explain Mayakovsky's innovation in the field of rhyme with the help of vocabulary that emerged after 1917. “A poet who put his work at the service of the revolution,” the author writes, “needed to master a lot of words related to the construction and defense of the proletarian state ...” (p. 22). But since "Mayakovsky's rhyme is saturated with meaning," "the poet had to "get" a number of new rhymes for words that, in connection with the revolution, replenished the vocabulary of the Russian language" (p. 23). So, innovation arose because after 19At the age of 17, Mayakovsky needed to select a rhyme for new words. Such a “lexical” explanation of innovation raises a number of perplexing questions: Mayakovsky had new ways of rhyming even before the revolution, when there were not many words that appeared later. By the way, the words listed on page 22 were mostly known to the poet even before the revolution. Before 1917, was Mayakovsky not familiar with the words "revolution", "socialism", "communism", "dictatorship", "revolt", "proletarian", "Bolshevik", etc.? Not only was he familiar, but he also used it in rhyme (for example, "stubby - revolutions" in "Cloud"). Therefore, a lexical explanation of innovation is by no means sufficient.

23). So, innovation arose because after 19At the age of 17, Mayakovsky needed to select a rhyme for new words. Such a “lexical” explanation of innovation raises a number of perplexing questions: Mayakovsky had new ways of rhyming even before the revolution, when there were not many words that appeared later. By the way, the words listed on page 22 were mostly known to the poet even before the revolution. Before 1917, was Mayakovsky not familiar with the words "revolution", "socialism", "communism", "dictatorship", "revolt", "proletarian", "Bolshevik", etc.? Not only was he familiar, but he also used it in rhyme (for example, "stubby - revolutions" in "Cloud"). Therefore, a lexical explanation of innovation is by no means sufficient.

More fruitful is the author's search for innovation in Mayakovsky's "democratization of verse" (p. 105). But here, too, M. Shtokmar focuses on vocabulary, “linguistic style”; on pages 108 - 116 it is traced how the poet uses colloquial words in rhyme. But the "peculiarities of the language" (p. 106) also apply to prose speech.

But the "peculiarities of the language" (p. 106) also apply to prose speech.

Sometimes you can hear: "Mayakovsky's new rhyme appears because the poet needs to express new content." But such statements will remain general words until it is revealed how the new content is reflected in the structure of the verse.

The origins of Mayakovsky's innovation should be sought in the specificity of verse as an expressive system of speech with "its own sound organization, which is realized in a specific pronunciation.

Verse implies a special perception, different from the perception of prose speech. When perceiving a verse, the attention of the reader or listener is sharpened. The listener reacts not only to semantic changes, but also to changes in individual components of the sound structure (rhythm, rhymes, etc.). When perceiving a verse, linguistic errors in form and poetic technique are more striking.

In the article “Our verbal work”, Mayakovsky pointed out that the armament with new poetic devices is “not an aesthetic end in itself, but a laboratory for the best expression of the facts of our time” (vol. II, M. 1939, p. 498).

II, M. 1939, p. 498).

Mayakovsky's innovation in the field of rhyme is explained by the fact that Mayakovsky deliberately rebuilt the verse structure to better express the poetic content. The poet took into account that the constant use of traditional rhymes (as well as “meters”) in a poetic work leads to the fact that when reading, you begin to pay attention not to the content of the poetic work, but to the repetition, monotony and grayness of the rhyme (cf. Mayakovsky’s statement about rhyme “ sobriety - playfulness").

Mayakovsky's verse is specific, because, as M. Shtokmar noted, it is designed for a special pronunciation, the relationship between words is of a different nature than, for example, in Pushkin's poetry, each word sounds more full-bodied and is separated by a special pause. Since special pauses appear in Mayakovsky's verse, the connection between words weakens, becomes less tangible, the "melodiousness" of the verse disappears, and the role of rhyme as an organizing factor increases. Therefore, Mayakovsky said that without rhyme, "verse ... will crumble."

Therefore, Mayakovsky said that without rhyme, "verse ... will crumble."

A conscious orientation toward a specific pronunciation led to an ever greater emergence of pronunciation (acoustic) rhyme, and the strengthening of the organizing function of rhyme led to an increase in the degree of support, that is, the number of common sounds to the left and to the right from the reference vowel (M. Stockmar speaks only of an increase in the number of common sounds to the left).

The question of the connection between rhymes and 9 almost does not appear in the field of view of the researcher0092 rhythm in Mayakovsky's verse. In addition to strengthening the organizing function of rhyme, the importance of rhyme as a rhythm factor increases in Mayakovsky's verse. Rhyme, interrupting the smooth flow of poetic speech, divides it into verses, forming the primary rhythm of verses. The peculiarity of this function of rhyme in Mayakovsky's verse has not been revealed.

Some of the terms used by the researcher are not disclosed. The author uses the word "inaccuracy" (p. 38), speaks of "inaccurate rhyme" (p. 42). But what is "inaccuracy" as a category of poetry and what is the aesthetic meaning of this category? The question of the classification of Mayakovsky's rhyme from a sound point of view remained unanswered. Is the existing highly controversial classification into "exact" and "inexact" rhyme applicable to Mayakovsky's rhyme?

The author did not say enough about the achievements of his predecessors. So, for example, the statement on page 30 about how the role of the pre-stress part of consonance increases in Mayakovsky's rhyme was first formulated by V. Zhirmunsky 1 , and then developed by V. Bryusov 2 , and this should be pointed out.

As can be seen from what has been said, M. Shtokmar's book, which on the whole is very useful for Soviet versification, contains shortcomings, as well as controversial and insufficiently proven provisions.