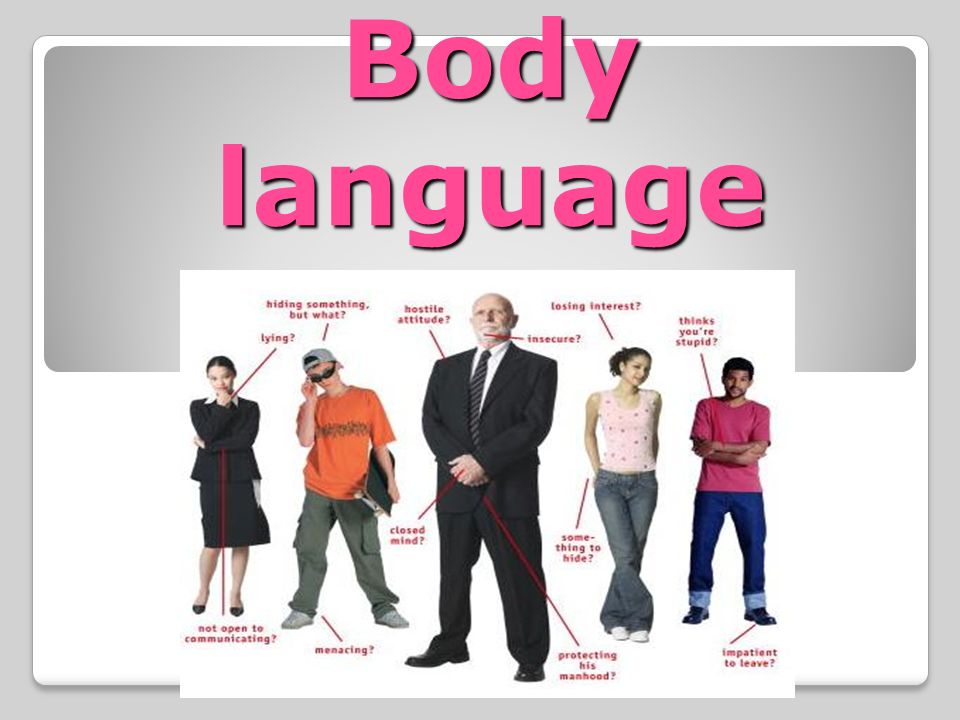

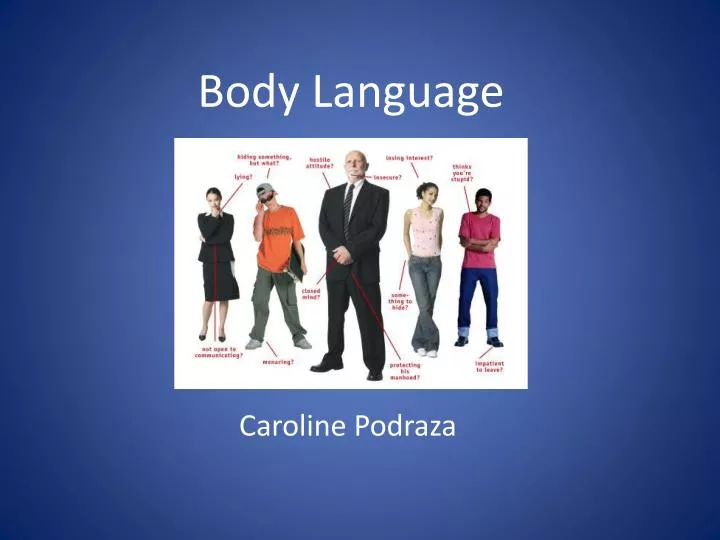

Basic body language

How to Understand and Read Body Language

Nonverbal communication is complex. It takes time and practice to increase awareness and perception of others’ body language.

Everyone from FBI agents to human resource professionals examine body language for clues about a person’s character.

It’s common for media commentators to scrutinize the postures, gestures, and facial expressions of public figures for insights into attitudes, beliefs, and inner worlds.

An angry look on the faces of celebrity lovers raises concern in the headlines about trouble in paradise, for example, or a halfhearted handshake between politicians becomes a debate about perceived disunion.

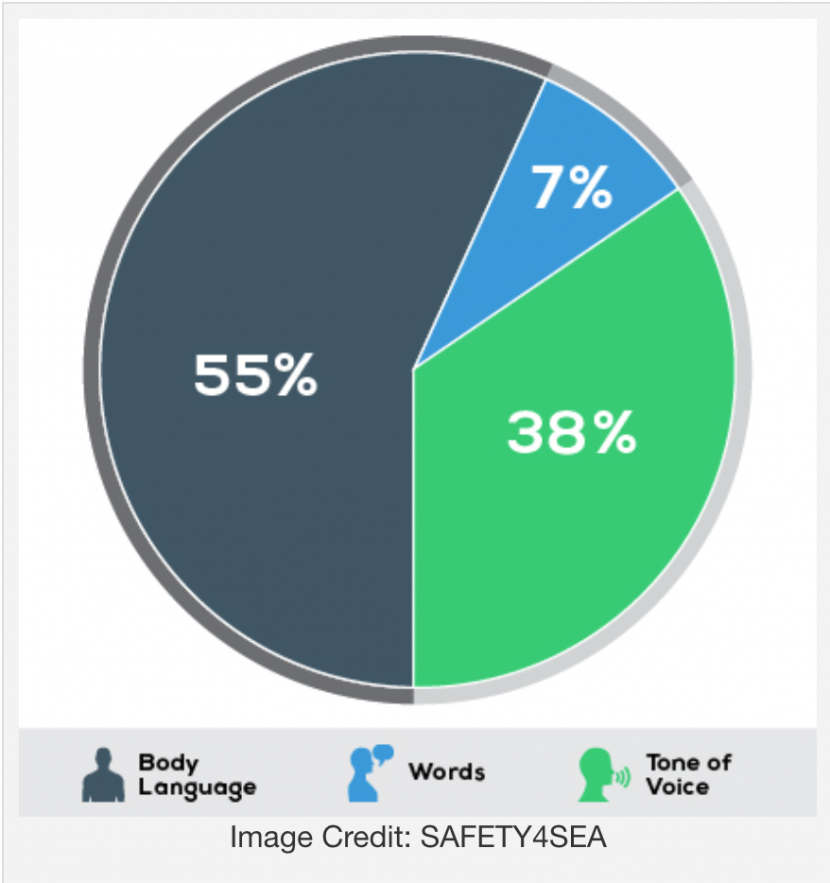

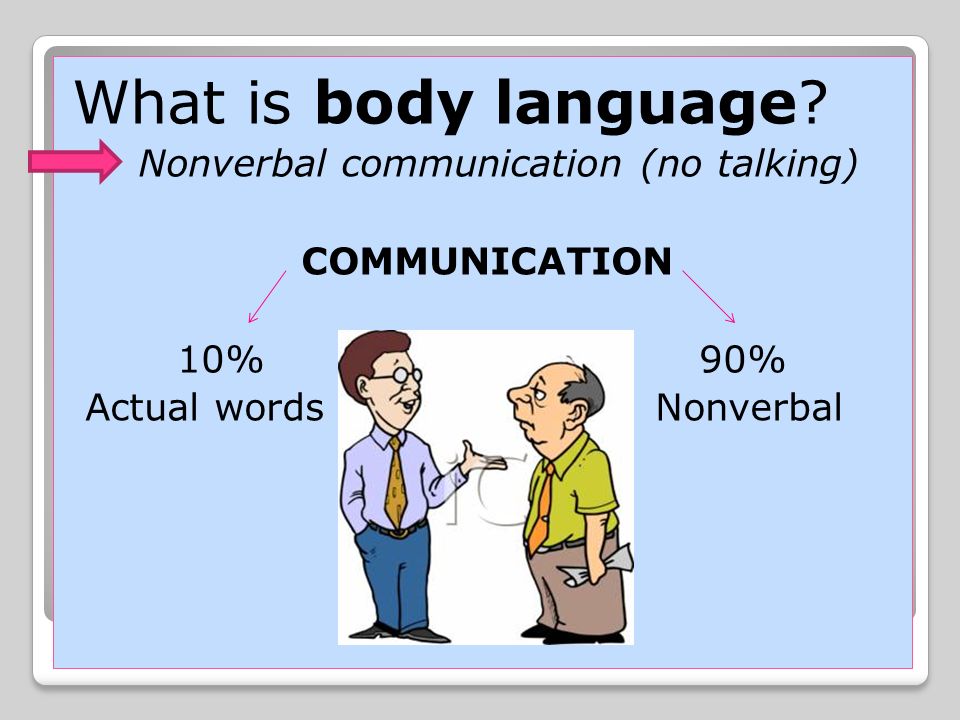

In the early 1970s, Albert Mehrabian, an engineer turned pioneer nonverbal communication researcher, found what is sometimes known as the 7-38-55 rule.

This means that of all messages, only 7% is verbal (words only), 38% is vocal (tone of voice, intonation, and other sounds), and 55% is through nonverbal (no words) forms of communications.

Nonverbal messages are so important for success in life that leaders in many fields even hire personal body language experts to help them communicate better without words.

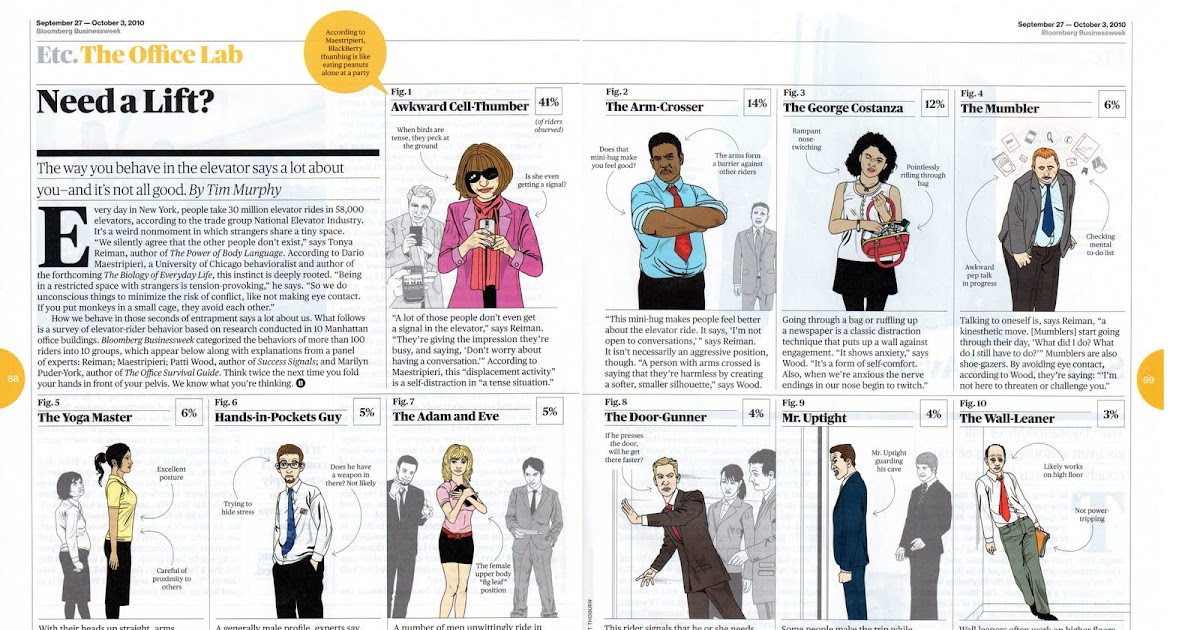

For the average person going about the day, much of your perception of body language is seemingly automatic.

Your supervisor gives you an instruction and your nod likely lets them know you understand, for example. Your friend smiles and you may assume a warm connection.

Yet when it comes to truly understanding how people communicate nonverbally, it’s worthwhile to learn the ins and outs of body language.

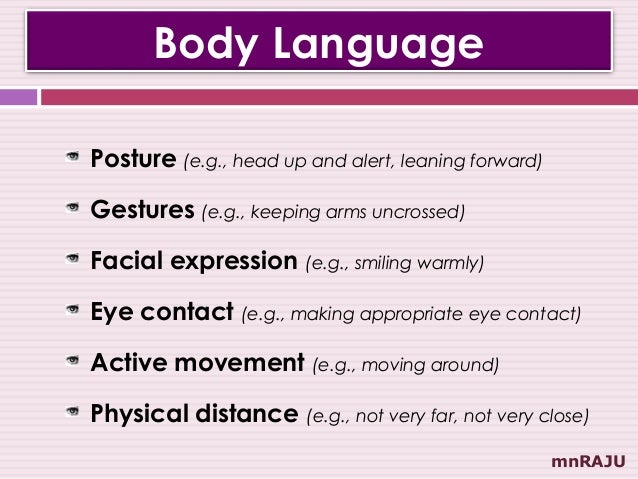

At the most basic level, body language is an external signal of a person’s inner emotional state. Body language is the story our bodies tell about how we think and feel.

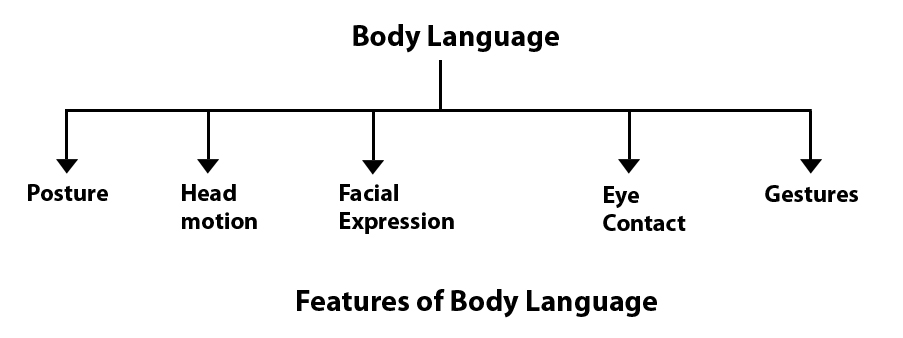

Understanding body language requires an overview into the different types of nonverbal communication and what they can mean.

According to Barbara and Allan Pease, authors of “The Definitive Book of Body Language,” researchers have recorded almost a million nonverbal cues and signals.

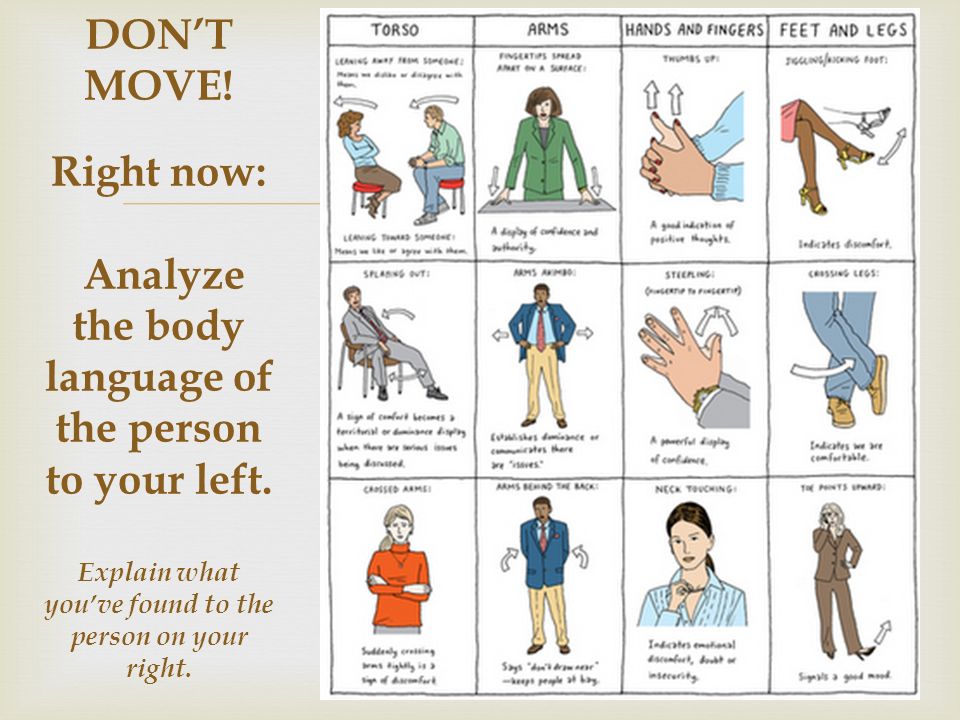

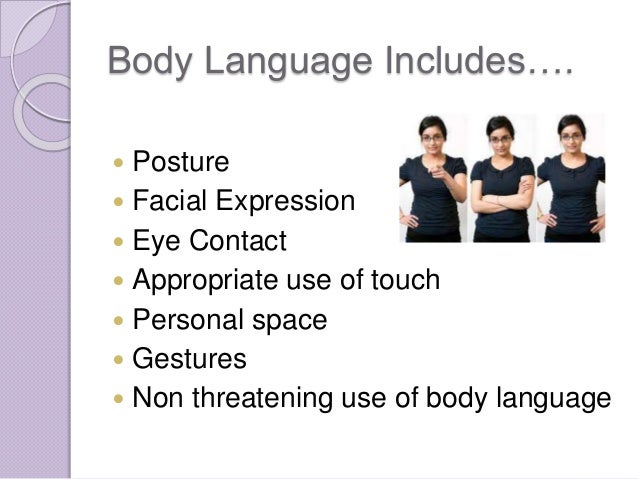

Some of these cues and signals include:

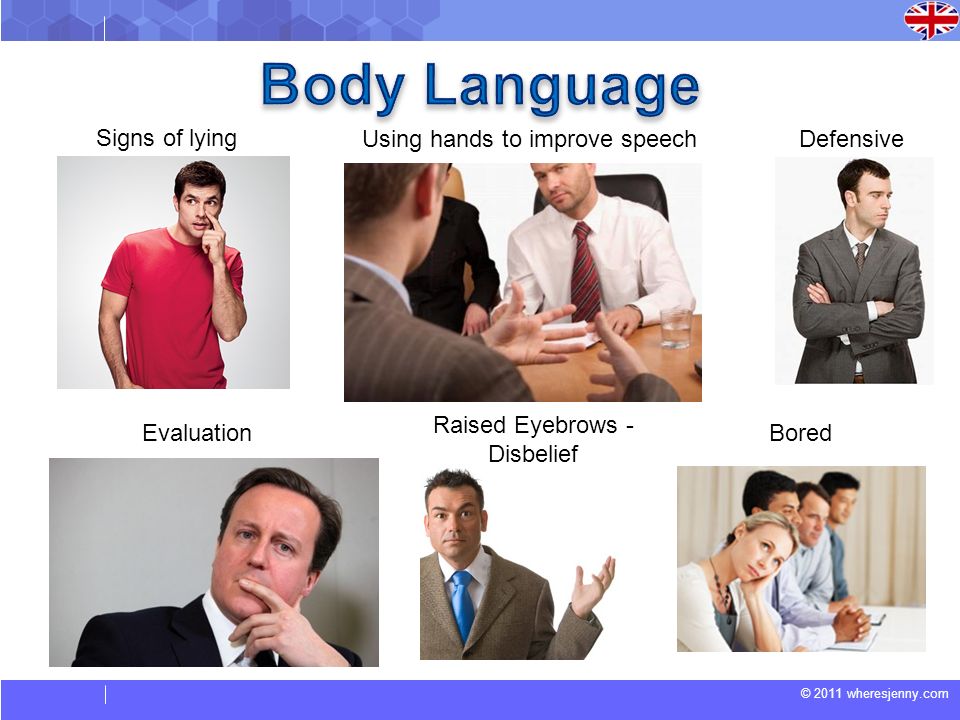

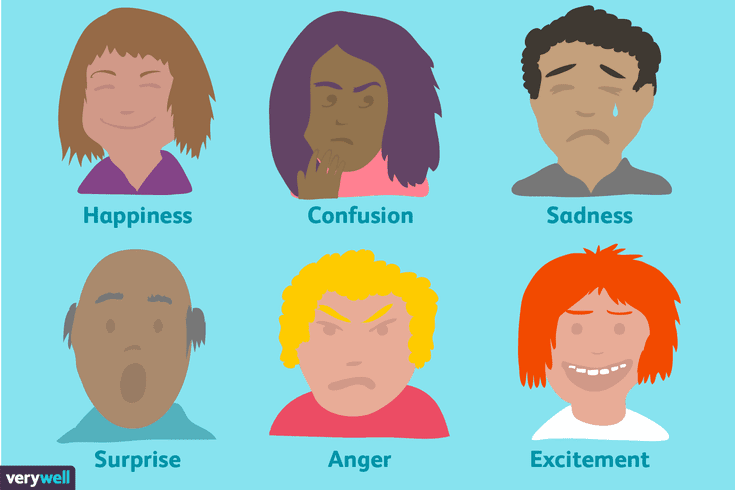

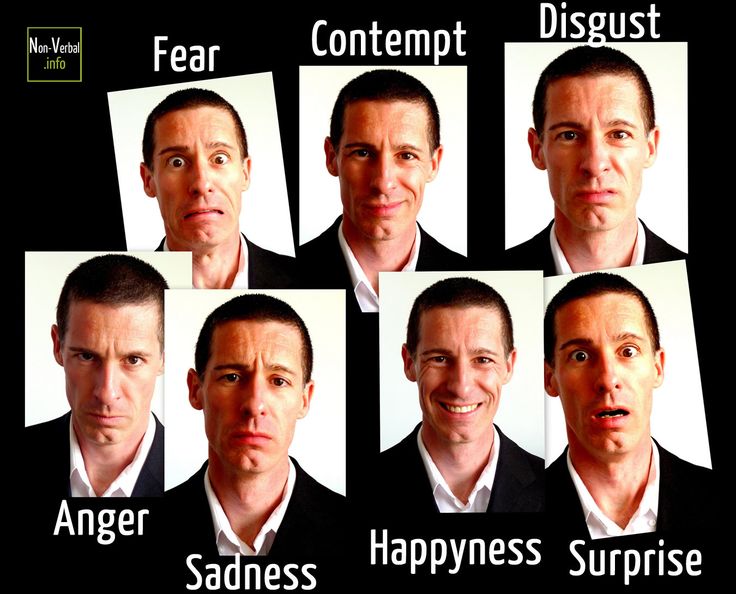

- facial expressions (raised brow indicating surprise, scowl indicating anger, frown indicating sadness)

- nonverbal cues (smiling, winking, nodding)

- hand gestures (thumbs up, a wave, pointing)

- posture (hunching, tilting head, sitting up straight)

- eye contact

“Most people are remarkably unaware of body-language signals and their impact, despite the fact that we now know that most of the messages in any face-to-face conversation are revealed through body signals,” wrote Barbara and Allan Pease in their book.

Reading and understanding body language takes time and is important in navigating several aspects of life, including:

- expressing intimacy

- providing information

- exercising professionalism

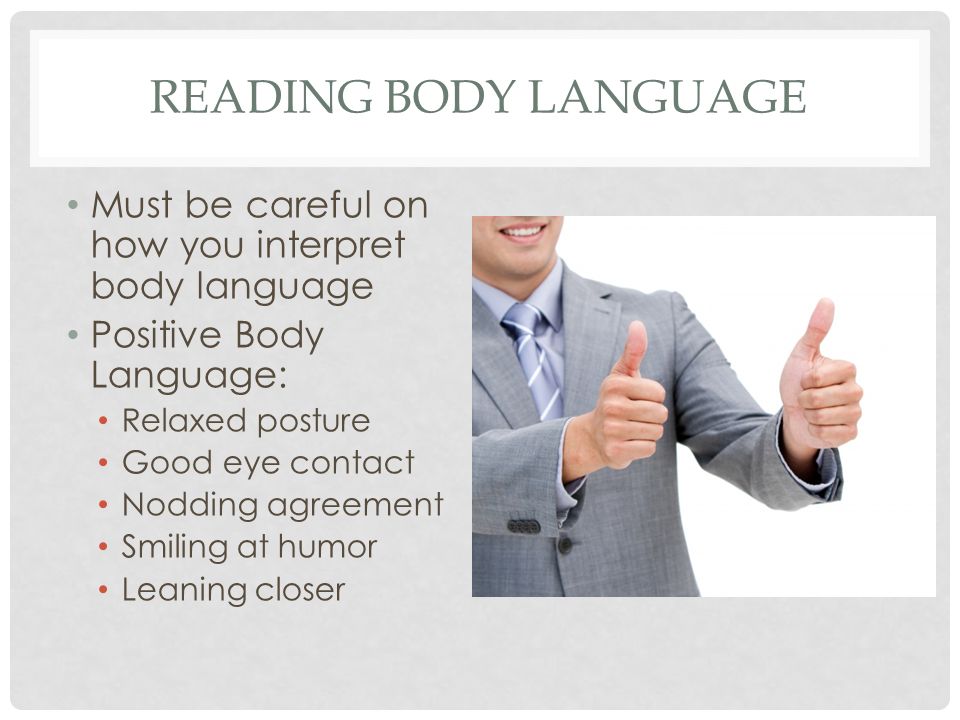

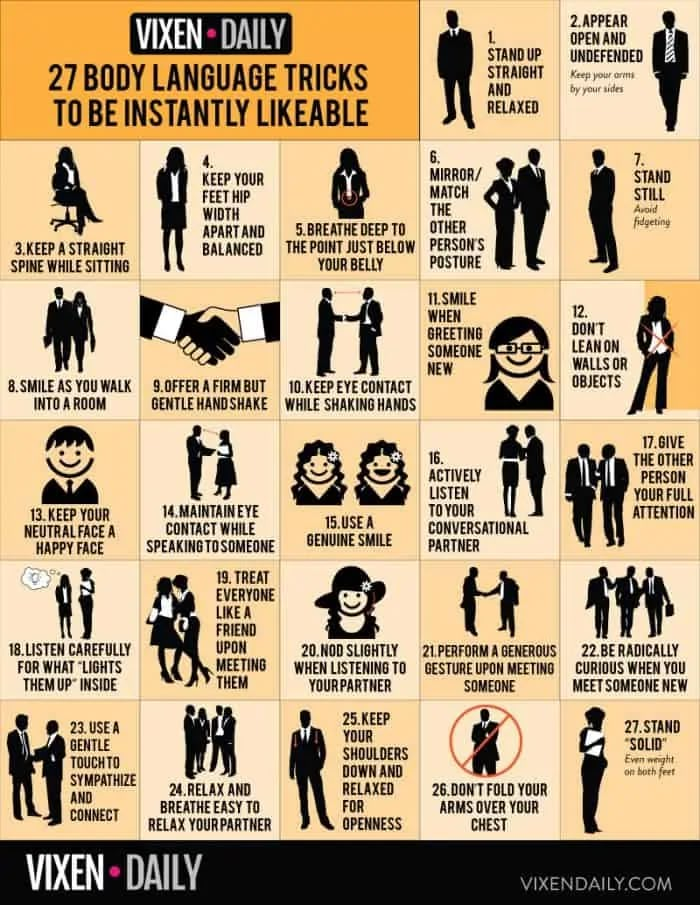

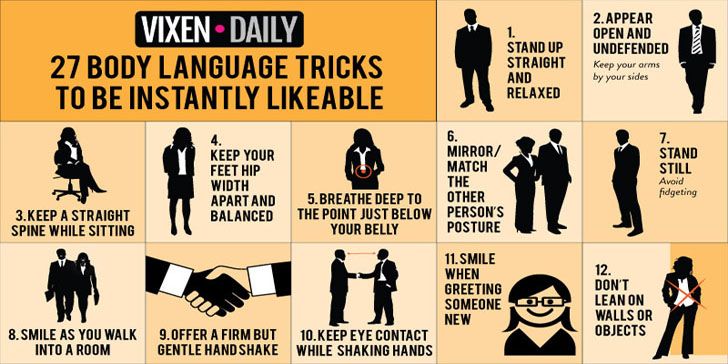

Here are a few tips to keep in mind as you work on improving your nonverbal communication skills.

Record yourself

Blake Eastman, creator of The Nonverbal Group and former adjunct professor of psychology in New York, suggests that recording ourselves communicating either in presentation form or with a trusted friend is one of the best tools for growing our body language awareness.

“Raw behavioral data — displayed via video — is the reality of what is happening,” he says.

According to Eastman, analyzing video allows us to slow down and more closely study how we communicate nonverbally.

Tune into microexpressions

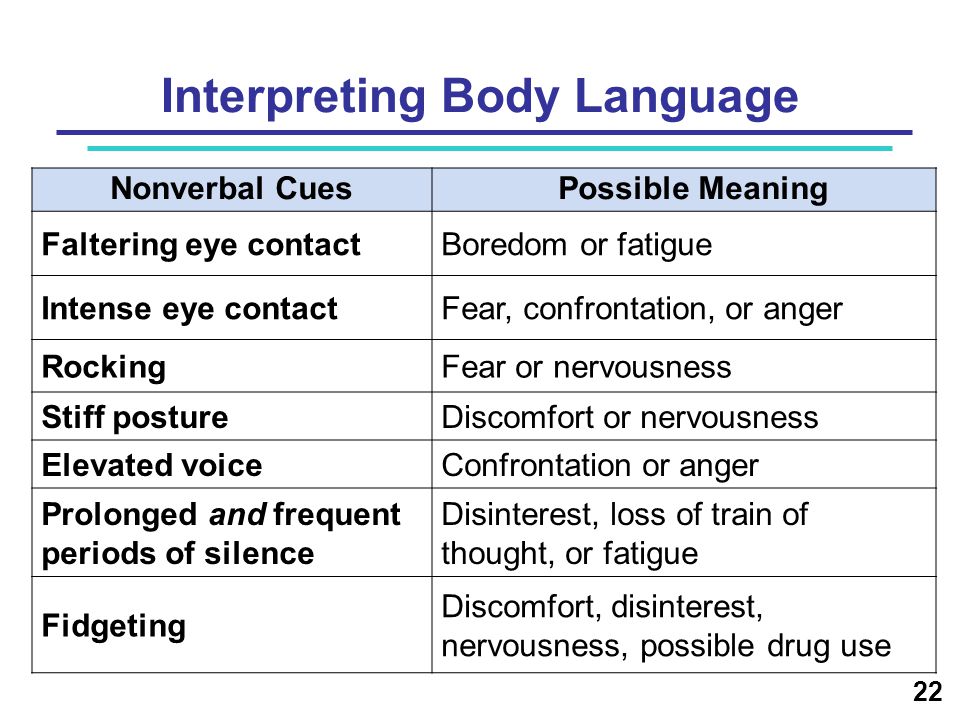

Becoming a perceptive observer of nonverbal communication takes paying careful attention to subtle movements, such as tilts of the head, rolls of the eye, or small shifts of the mouth.

Watching someone’s face or body for subtle movements can help you more closely tune into what they may knowingly or unknowingly be expressing.

Investigate your assumptions

Just as much of our body language is automatic, so is much of our perception of others’ body language — and it often goes unquestioned.

Someone might have a blank expression on their face that you might take for disinterest or even anger. But this isn’t always the case. Maybe that expression is how they express contentment — or maybe their thoughts are somewhere else entirely.

Where socially appropriate, you may consider asking for gentle clarification to match emotions with facial expressions. You might ask, “How are you feeling about what I just said?”

Put nonverbal communication in context

Nonverbal communication is interpreted differently across varying cultures and settings.

A kiss on the cheek could be a romantic gesture in America but merely a platonic greeting in parts of Europe. Sustained eye contact could signal polite attention at work but could seem rude at a public park.

Becoming a student of human behavior through body language in part requires studying the unspoken rules of the subcultures and surroundings that you inhabit.

Leave room for the unknown

When we interpret others’ nonverbal communication, it’s easy to assume that the meaning we give to the interaction is the correct one.

Eastman, who has coached thousands of clients on how to improve their body language, advises to acknowledge what we don’t know about how others communicate.

He says, “There’s [often] a behavioral disconnect between what people want to show and how they show it.”

Beyond behavioral disconnect, it’s not helpful to overlook the impact of bad days, illnesses, and distractions that might influence a person’s body language in any given interaction.

“We are never in a state where we are not transmitting information,” said Joe Navarro, author of “The Body Language Dictionary,” in an interview with Wired magazine.

Navarro, a former FBI agent, knows firsthand how much information we can learn through gestures, body movements, facial expressions, and tone of voice. He also knows just how careful we have to be in how we interpret body language.

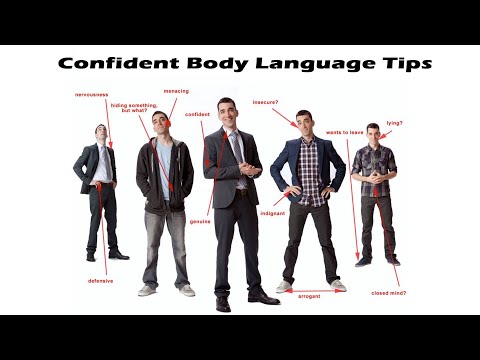

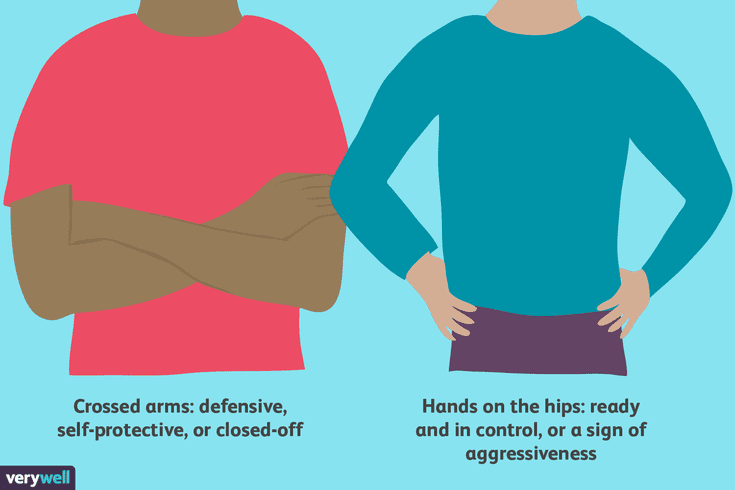

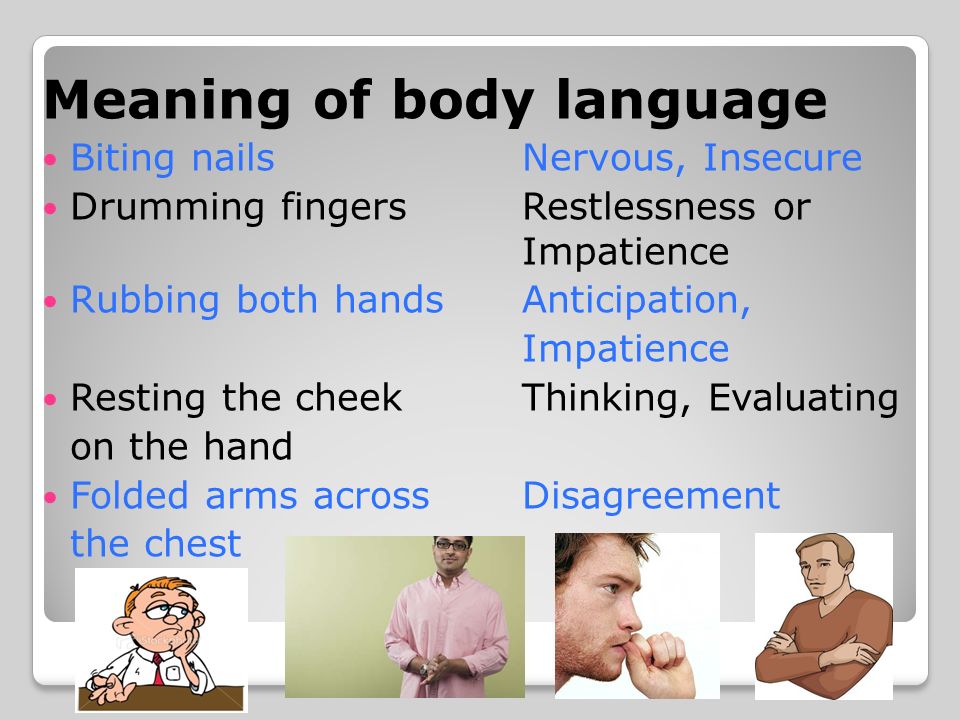

For example, let’s say your spouse crosses their arms. You may assume they’re closing themselves off, but what if their crossed arms indicate a self-hug instead? Or maybe your co-worker clears their throat and you wonder if they might be telling a lie. But is it possible they have a cold?

According to Navarro and Eastman, these are common false body language narratives. Crossing the arms and clearing the throat can both be self-soothing or pacifying behaviors and are not necessarily evidence of disinterest or deception.

Crossing the arms and clearing the throat can both be self-soothing or pacifying behaviors and are not necessarily evidence of disinterest or deception.

The meaning we give to others’ nonverbal communication can be highly misleading or even ableist.

Let’s say you view someone as unfriendly because they do not smile as much as socially expected. But it’s possible that individual could be nicer than you perceive. In fact, some people experience a flat affect, where they show fewer facial expressions than others.

Eastman says, “The first step in reading behavior is to really understand how often you’re just so wrong.”

Nonverbal communication is shaped by several forces including:

- personality

- environment

- biology

- culture

Understanding what we say without words takes practice and curiosity — and a willingness to sometimes be wrong — about human behavior.

It’s admirable to desire to improve how you read and understand body language. Doing so may help you gain further insight into the human experience.

Doing so may help you gain further insight into the human experience.

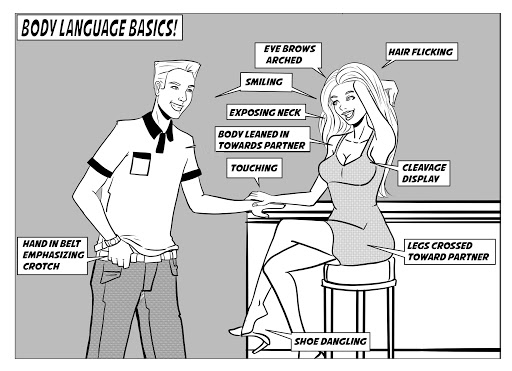

Body Language Basics

From a flip of the hair to hands on your hips, how you move, gesture, and make expressions can say as much as what comes out of your mouth.

Written by Heather Hatfield

Medically Reviewed by Louise Chang, MD on December 19, 2007

Angel Rose, 34, an assistant vice president at a bank in upstate New York, was interviewing candidates for a teller position, which required that a person have good people and communication skills, a professional presentation, and a strong focus on customer service, among other abilities.

One candidate in particular stood out, but not in a good way. While they could have been very intelligent, their nonverbal communication and body language were way off. Their handshake was more of a finger shake, their eye contact was nonexistent, and their slouched posture exuded insecurity. For Rose, what the candidate said didn't matter because their body language spoke volumes: they weren't a good fit for the position.

"Most communication experts now believe that almost 90% of what we say comes from nonverbal cues, which includes our body language," says Patti Wood, author of Success Signals: A Guide to Reading Body Language.

Body language, she explains, is everything from our facial expressions, to eye contact, to our gestures, stance, and posture. While the nuances of body language are complicated, there are some common body language signs worth a thousand words.

Body Language ABCs

Flipping your hair, shaking hands, making eye contact, and smiling are more than just movements -- they're a part of your nonverbal communication, adding emphasis and emotion.

"Body language represents a separate communication process beyond words," says Ross Buck, PhD, a professor of communication sciences and psychology at the University of Connecticut. "It exists simultaneously with language, but it is emotional and largely happening at the subconscious level."

What are some of the basic body language cues that we display and what kind of effect can they have on the impression we make on other people? Here's a beginner's guide to understanding what our bodies are saying:

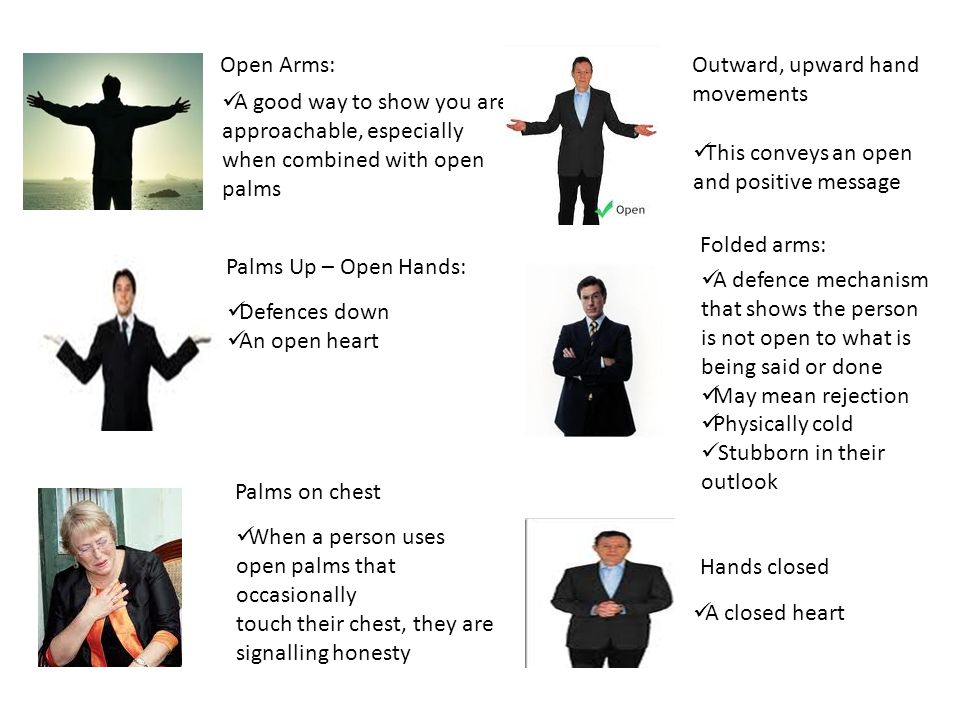

Handshakes. A handshake can say so much more than hello, nice to meet you. "The most important part of a handshake is palm-to-palm contact," says Wood. "It's even more significant than the grip."

A handshake can say so much more than hello, nice to meet you. "The most important part of a handshake is palm-to-palm contact," says Wood. "It's even more significant than the grip."

The palm-to-palm contact expresses an intention of honesty and openness, and that your interaction will be sincere and nonthreatening.

The "limp fish" handshake, Wood explains, seems so uncomfortable because it usually means that the palms don't touch, as Rose experienced in her interview.

Here are other handshake types:

- Bone crusher: A person may be insecure and trying to overcompensate with an over-the-top hello.

- Palm-down handshake: A person may be trying to express their dominance.

- A left-handed wrap of the handshake from the top: A person may be trying to express their dominance.

- A left-handed wrap of the handshake from underneath: A person may be trying to support and comfort you.

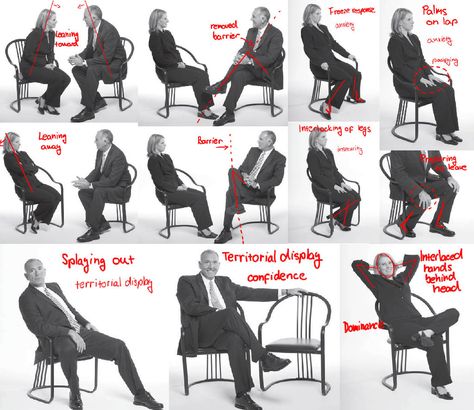

Synchrony. Synchrony happens when two people who are interacting mirror body language cues, explains Buck. What can it mean?

What can it mean?

"Synchrony is a signal that both people are on the same page," says Buck. "When you see someone copying your body language, or you notice that you are copying his, it's a clue that you are probably sharing a similar mind-set at the time."

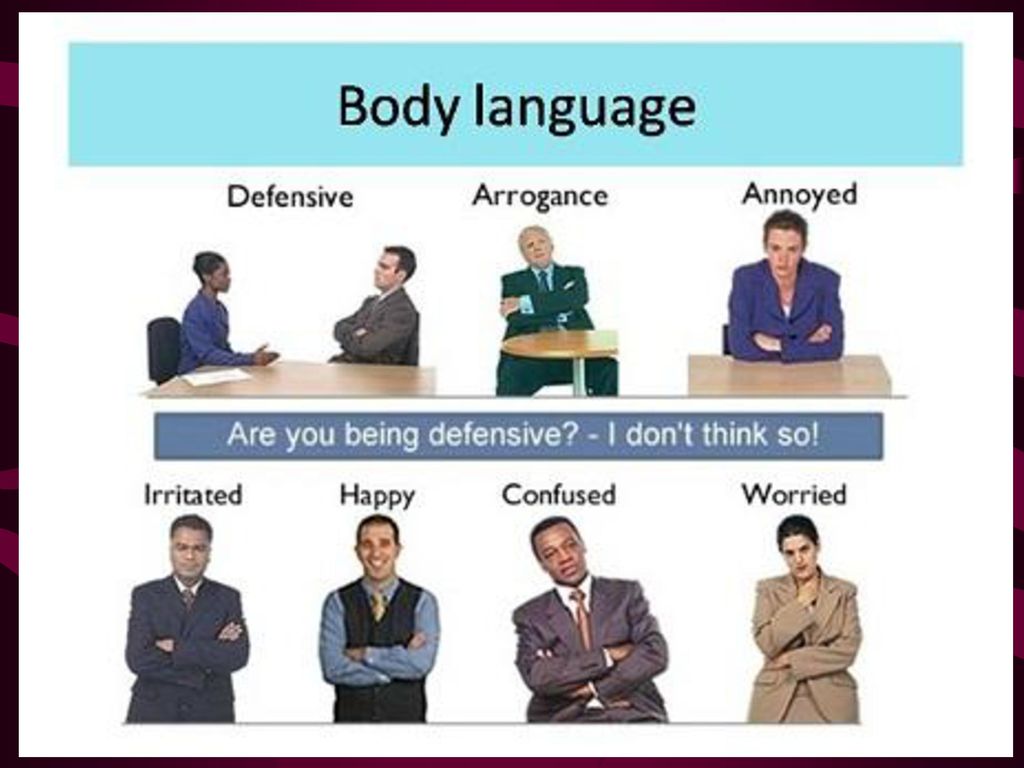

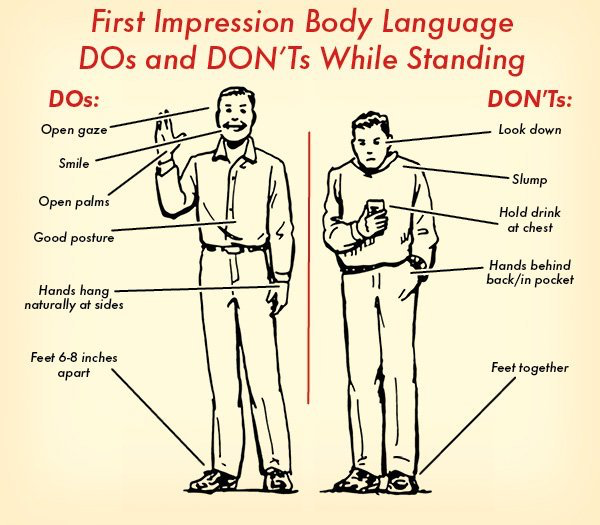

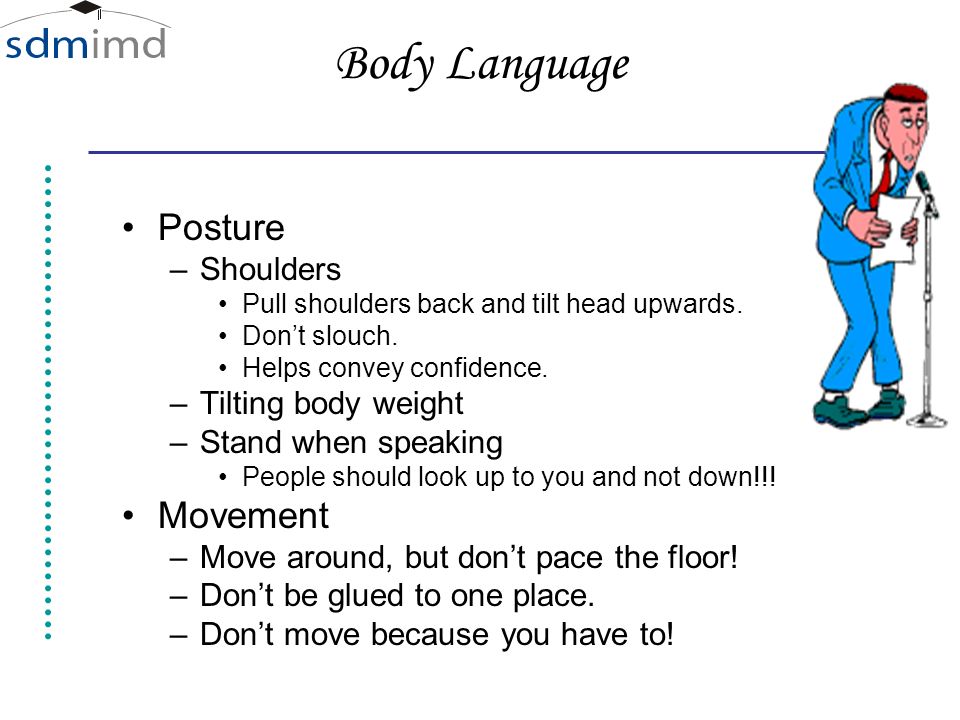

Posture. "Posture can be sign of dominance or submissiveness," says Buck.

Shoulders back with an erect posture can be a sign of dominance, he explains, while being slumped can mean insecurity, guilt, or a feeling of shame.

Eye contact. "While the rules of eye-contact engagement vary from culture to culture, in the U.S., it can mean honesty and forthrightness," says Buck.

The eyes are a powerful part of our body language cues and can express everything from sexual interest, to annoyance, to happiness and pain, he explains.

Playing with your hair. When women cup their hand, palm out, and tuck their hair behind their ear, it can be an expression of flirting, and can mean openness and interest, explains Wood. But be careful: It can also mean their hair is in their eyes.

But be careful: It can also mean their hair is in their eyes.

Using Body Language to Your Advantage

"If you want to better manage your own body language, you need to think about every aspect of your day and how you behave," says Wood.

While you might think you are friendly person, if you go straight to your office and avoid eye contact with anyone, it can send the wrong signals to your co-workers, she explains.

Go through your morning routine -- what you do at lunch, how you spend your afternoon and evening -- and ask yourself questions like: Do I smile? Do I make appropriate eye contact with people? Once you better recognize your body language, you can start to manage it in a more meaningful way.

On the flip side, how can you use the body language of others to your advantage? Most important is to trust your gut.

"Body language says so much, that you can use it to gauge the sincerity of what a person is saying," says Wood.

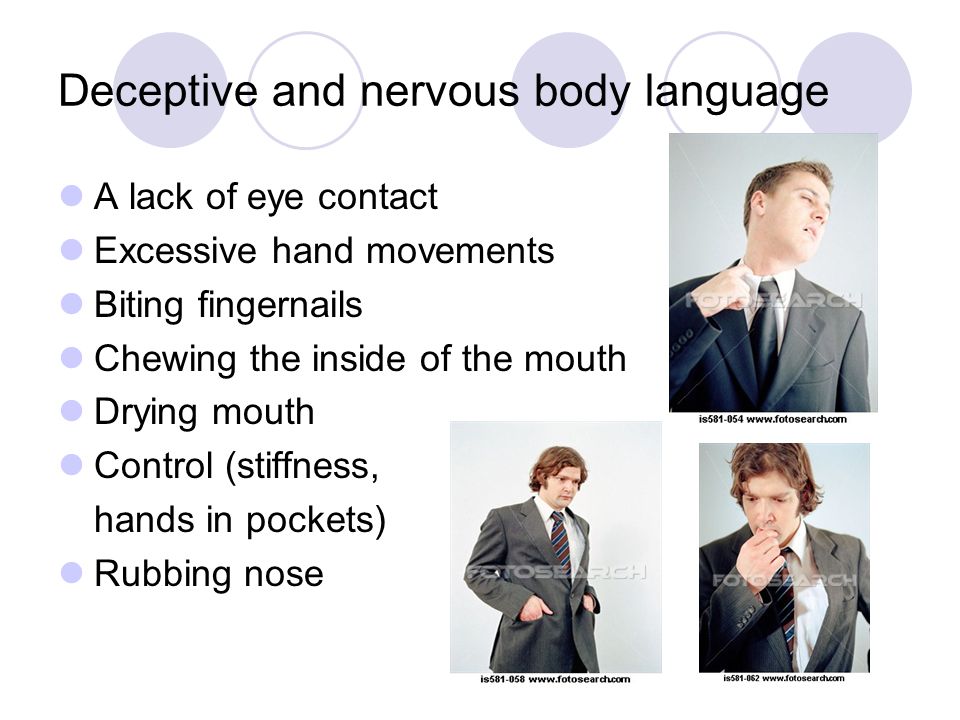

If a person is telling you something, and they are covering their mouth, they might be lying, she explains. If a person's hands rub from their forehead down across their face, they could be wiping away an emotion, like stress or anxiety. Either way, if what a person is saying contradicts their body language, your intuition might be picking up on something that is not quite right.

If a person's hands rub from their forehead down across their face, they could be wiping away an emotion, like stress or anxiety. Either way, if what a person is saying contradicts their body language, your intuition might be picking up on something that is not quite right.

Still, whether you are trying to manage your body language better, or understand that of others, remember the value of words.

"If you become too attentive to body language, instead of what you are saying or someone is saying to you, you miss out on the larger process of communication," says Buck.

Body Language Put to the Test

A basic understanding of body language, combined with verbal communication, can come in handy in almost every situation in your daily life. Here are some common scenarios in which body language can have a big impact, plus tips for putting your best foot forward while you watch what others around you are saying with their silent signs.

First dates. First dates are laden with body language signs that can help you gauge whether or not a person is interested.

"Men tend to talk a lot on first dates when they're interested in a woman," says Wood. "If you're interested back, make eye contact and listen."

If either person isn't interested, and looks around the room and avoids eye contact, that's a sign that a second date isn't likely.

Other first-date tips?

"When men touch a woman on the small of her back to walk her through a door, that's a sign of confidence and interest," says Wood.

For women, it's the length of their touch that measures their interest. While short, less-than-a-second touches are appropriate, touches that are too long could convey an intimate meaning.

Job interviews. First and foremost, don't sit down while you wait for your interviewer to come and greet you; it puts you in an awkward position where you have to stand and gather yourself and your belongings in an odd sort of shuffle.

"Instead, stand and wait, or sit on the arm of a chair," says Wood. "And when your interviewer arrives, make eye contact, raise your eyebrows slightly in acknowledgement, smile, and then shake hands. "

"

During the interview, she suggests you make eye contact when listening to show your interest, but don't stare. Sit up in your chair instead of slouching, and when you're done, leave strong by giving a good, palm-to-palm handshake.

Dinner with the in-laws. "One of the most important body language signs you should convey during your first encounter with your partner's parents is eye contact with your partner," says Wood.

Your partner's parents want to know that you are interested in and care for their child. The best way you can tell them that you are "the one" is to look at your partner with love and affection.

Body language | it's... What is Body Language?

This term has other meanings, see Body language (meanings).

Body language

gesture

Body language — sign elements of postures and movements of various parts of the body, with the help of which, like with the help of words, thoughts and feelings are structurally formed and encoded, ideas and emotions are transmitted. Body techniques, which include such non-significant movements as facial gestures, head and foot gestures, gait, and various postures, also belong to body language.

Body techniques, which include such non-significant movements as facial gestures, head and foot gestures, gait, and various postures, also belong to body language.

|

Contents

|

Classifications

- Body language that exists in parallel and interacts with the language of words in a communicative act (a subject of study of non-verbal semiotics and many other sciences)

- Artificial sign languages with little relation to speech - languages designed for people with hearing impairments

- pantomime language

- ritual sign languages

- professional sign languages and dialects

- gestural visual subsystems of theater and cinema languages, dance languages

The science of body language and its parts is kinesics , along with paralinguistics (the science of sound codes of non-verbal communication) it belongs to the central area of non-verbal semiotics - the science of non-verbal sign systems. Research in the field of non-verbal communication is also carried out by such sciences as applied psychology, ethnography, history, pedagogy, and psycholinguistics. In visual recall, the interlocutor's eyes are usually directed upwards to the left. When constructing (fiction), the eyes are directed upwards to the right. The first reaction to your question or information is important. For example, if a person with a fleeting movement of his eyes looked up to the right and then down to the left, most likely the person is lying: first he constructed an image that he had never seen, and then he begins to select words. Here it is necessary to take into account the fact that some people, preparing their lies in advance, visually well imagine the desired picture. They can remember their lies in the form of visual images and their eyes will be directed upwards to the left. So don't jump to conclusions.

Research in the field of non-verbal communication is also carried out by such sciences as applied psychology, ethnography, history, pedagogy, and psycholinguistics. In visual recall, the interlocutor's eyes are usually directed upwards to the left. When constructing (fiction), the eyes are directed upwards to the right. The first reaction to your question or information is important. For example, if a person with a fleeting movement of his eyes looked up to the right and then down to the left, most likely the person is lying: first he constructed an image that he had never seen, and then he begins to select words. Here it is necessary to take into account the fact that some people, preparing their lies in advance, visually well imagine the desired picture. They can remember their lies in the form of visual images and their eyes will be directed upwards to the left. So don't jump to conclusions.

Well, if you know for sure when your interlocutor is lying to you, then remember the strategy of his lie: what he says at such moments, where his eyes are, how he behaves. Perhaps knowing this person's lying strategy will help you later. Audials, visuals, and kinesthetics differ from each other in eye movements, predicates, timbre and pitch of voice, speed of speech, external data, and a number of other features.

Perhaps knowing this person's lying strategy will help you later. Audials, visuals, and kinesthetics differ from each other in eye movements, predicates, timbre and pitch of voice, speed of speech, external data, and a number of other features.

Visuals strive to dress more beautifully. In a conversation, it is important for them to show themselves and look at others. If there is a choice, in a room where there are several chairs, the visual will choose a place for himself that allows him to see the interlocutor. Always trying to keep his distance. Kinesthetic, on the contrary, is important for close communication, he likes to touch the interlocutor, grab him by the elbow. (Surely you know many such people). It is interesting to observe the communication of the visual and kinesthetic: it turns out a kind of dance. If space permits, the visual will constantly move away from the kinesthetic, and he will constantly come closer. This can continue for a long time until the visual, for example, is pinned to the wall.

If eye contact during a conversation is important for the visual, then he may not expect this from the auditory, which is important to hear. Everything else is secondary. In more detail, you can compare these conditional groups of people according to the information below.

Visual type

Clear voice, not breathy. Loudly (and not intonationally) accentuate the meaning. Trying to stay straight. The line of sight during contact should not be lower than the line of sight of the interlocutor, eye contact is needed ("if you do not look, then you do not hear"). During a conversation, they gesticulate (gestures above the chest), and when they listen, they freeze.

The contact zone is very high - keep a distance when you cross his zone, he (successively): 1) dilates the pupils; 2) raises eyebrows; 3) moves his head back; 4) pushes back the shoulders; 5) departs. They strive to dress beautifully, comb their hair, make beautiful gestures, take beautiful poses. Sensitive to external arrangements (like order) - remove dust when they see it, so that it is beautiful.

Kinesthetic type

Perceive the world with the body. Breathing is abdominal, slow and deep. The voice of a low timbre, slow pace, speech is quiet, soulful, weighty (does not just say so).

Sits closer, touches, likes to “grab” a button, elbow, walk around. He rubs his hands, strokes. The line of sight is below or at the level of the interlocutor's gaze, eye contact with the interlocutor is not necessary, but often interferes: it distracts from one's own bodily sensations. Kinesthetic gestures - below (to the chest).

Auditory type

When interacting, pays more attention to timbre, loudness and other auditory submodalities, “shows with his voice”, copies the voices of others and intonations well. Does not need eye contact when talking, eyes closed.

Usually keeps hands in pockets, rarely makes “stingy” gestures at chest, covers eyes with palm, touches ear, often mutters. Of facial expressions, only the bottom of the face (mouth) is expressive, and so it is amimic. The movements are rhythmic, the head is tilted, the head rests on the hand. Speech measured, with pauses (for internal dialogue). Can tell the same story many times with the same words. Don't interrupt the auditory when he starts talking, otherwise he will start all over again or refuse to talk at all.

The movements are rhythmic, the head is tilted, the head rests on the hand. Speech measured, with pauses (for internal dialogue). Can tell the same story many times with the same words. Don't interrupt the auditory when he starts talking, otherwise he will start all over again or refuse to talk at all.

Undoubtedly, a person is much more complex than any of the models for dividing people into visuals, auditory and kinesthetics. (as well as other types not discussed in this article). Often there are mixed types of people. You need to keep in mind that at the moment your partner's strategy is close to the behavior of any of the types described above.

Peculiarities of functioning of signs of different nature in speech

Communicative activity in human life plays one of the most important roles. The ability to verbally communicate a message separates people from the natural world, but, remaining part of it, we have a unique ability to unconsciously and consciously read each other's body language: gestures, various postures, voluntary and involuntary movements. In 1963, the outstanding Russian linguist A. A. Reformatsky, discussing the nature of various sign systems, described their relationship in one communicative act. He emphasized the impossibility of modeling communication systems and the thought process itself without studying how a non-verbal text relates to a verbal one. A. A. Reformatsky came to the conclusion that the recoding of information is not the only important process in the act of oral communication. During communication, sign information is processed in parallel by different systems: sign systems of different nature "somehow compete in principle, but do not overlap, but represent a more complex relationship" (Reformatsky 1963). Thus, body language as a non-verbal part of communication, and sometimes the only part of it (in the case of artificial sign languages that do not correlate with speech: "Russian language of the deaf-mutes, Amslen - a sign system used by the deaf-mutes in North America, Amerind" - "language of hands" deaf and dumb North American Indians, Britlen - the language of the deaf and dumb countries of the British Commonwealth, the deaf and dumb languages of Italy, Sweden and many others) occupies an exceptionally important position in the history of culture.

In 1963, the outstanding Russian linguist A. A. Reformatsky, discussing the nature of various sign systems, described their relationship in one communicative act. He emphasized the impossibility of modeling communication systems and the thought process itself without studying how a non-verbal text relates to a verbal one. A. A. Reformatsky came to the conclusion that the recoding of information is not the only important process in the act of oral communication. During communication, sign information is processed in parallel by different systems: sign systems of different nature "somehow compete in principle, but do not overlap, but represent a more complex relationship" (Reformatsky 1963). Thus, body language as a non-verbal part of communication, and sometimes the only part of it (in the case of artificial sign languages that do not correlate with speech: "Russian language of the deaf-mutes, Amslen - a sign system used by the deaf-mutes in North America, Amerind" - "language of hands" deaf and dumb North American Indians, Britlen - the language of the deaf and dumb countries of the British Commonwealth, the deaf and dumb languages of Italy, Sweden and many others) occupies an exceptionally important position in the history of culture.

From the history of body language research

The science of body language is considered to be kinesics, although recently it has been customary to more narrowly specialize the objects of its study: the study of hand gestures, mimic gestures, head and foot gestures, postures and symbolic body movements. All these units of non-verbal communication are combined in the concept of "gesture" - from lat. gestus, meaning to do, wear, be responsible, control, perform, perform, etc. The well-known researcher of sign language A. Kendon, exploring the evolution of this term, noted that in Roman treatises on the behavior of speakers, for example, Cicero and Quintilian, "gesture" was defined as the rules for using the capabilities of one's body, significant movements of the arms, legs, body and face, which brings this term closer to its modern use - an interactive sign of everyday non-verbal human behavior.

Body language, occupying an important position in the history of culture, is the subject of research in rhetoric, medicine, psychology, pedagogy, art, chirology (the language of lines and tubercles of the hands), chironomy (the art of manual rhetoric) and physiognomy, the doctrine of the manifestation of the inner qualities of a person in features and facial expressions.

Major body language studies

- J. Balwer was one of the first to write a book on body language in 1644, where hand language was viewed as a natural natural formation, as opposed to an artificial invented language of words.

- J. Kaspar Lavater, a pastor from Zurich, in 1792 published an Essay on Physiognomy, the first systematic study of body movements, which describes in detail the relationship between human facial expressions, body configurations and types of personality traits of a person.

- G. K. Lichtenberg, an outstanding German scientist and writer, the main opponent of Lavater, wrote a book in 1765 in which he criticized him for an overly simplified approach to physiognomy: for striving to explain the world, proceeding only from consciousness, in isolation from the real world , from practical human activity

- C. Bell, anatomist, neurophysiologist, artist and surgeon, was one of the first to become interested in the expression of emotions on the human face.

In 1844, doing research in the field of functional analysis of the nervous system, he concluded that all strong feelings are accompanied by a change in breathing and muscular activity of the face and trunk under the influence of changed breathing patterns.

In 1844, doing research in the field of functional analysis of the nervous system, he concluded that all strong feelings are accompanied by a change in breathing and muscular activity of the face and trunk under the influence of changed breathing patterns. - C. Darwin and E. Kretschmer in 1920 conducted research to describe the links between human emotions, his character and body type, the links between human facial expressions and the meanings of these non-verbal units.

- D. Bonifacio, D. Batista del Porta and F. Bacon in the late Renaissance, the heyday of the study of body language, in 1616, in their treatises on non-verbal communication, argued that there is a universal sign language, understandable to all peoples, body language, which also speaks of the character and temperament of the individual.

- A. Kendon, D. Morris, G. Kreidlin, modern sign language researchers who pay more attention to the interaction of verbal and non-verbal codes, as well as to the peculiarities of the body language of individual cultures.

Body language and natural language

The underlying processes that underlie natural language and body language are essentially similar, which makes their parallel existence in a communicative act possible. The following are facts confirming their similarity.

Classic "shish" ("fig", "muzzle", "fig")

- Each element of non-verbal language, like the element of natural language, can become a unit of conventional agreement and acquire contextual meaning, for example, waving a handkerchief, forefinger and thumb in the ring, acquiring different meanings depending on the culture of the countries.

- Under certain conditions, meaning is conveyed from one subject to another either only with the help of gestures, or only with words, or with a combination of both signs.

- Gestures, like linguistic units, are mostly symbolic signs, they form the lexicon of body language, and gesture combinations can form semiotic gesture acts like speech acts.

- Many signs of a certain language can be translated into the corresponding verbal language, as well as into the sign language of another country. The translation problems associated with non-verbal language are basically the same as those of natural languages.

- Gesture behavior of people changes in space, in time, as well as under the influence of economic and cultural conditions, which is typical for natural language.

Thus, the parallel existence of signed and natural language can be traced quite clearly. Moreover, research in this area confirms that their interaction enriches the transmission of meaning and emotions, clarifies and enhances the meaning of information, creating vivid imagery of words. But, despite the presence of common properties, between body language and natural language there are fundamental differences.

- All natural languages are composed of relatively stable and discrete units, which is not the case for body language where there is no agreement on the form, meaning and use of non-verbal units.

- The mechanism of non-verbal reference is arranged and operates in a different way: non-verbal units usually directly designate their denotation, that is, the object and its attributes - size, shape, specific situations and objects with actual spatial categories, when language categories serve an incomparably greater number of ideas, various abstract concepts and categories.

- Finally, gestural signs are perceived by the eyes. Basically, these are visual signs endowed with special functions: they not only describe phenomena, objects and properties of the real world, but also depict these phenomena, point to them. Gesture elements, demonstrative in nature, in a communicative act perform not only an informative, expressive, regulatory function, but also a pictorial one.

Sources

- Reformatsky 1963 — Reformatsky AA About recoding and transformation of communication systems // Research on the structure of typology. M.: Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1963, 208-215.

- Kendon A. 1981b. Introduction: current issues in the study of .nonverbal communication.. In Nonverbal Communication Interaction and Gesture, ed. A Kendon, pp. 1–53.

- Kreidlin 2002 - Kreidlin G. E. Non-verbal semiotics // M .: "New Literary Review", 2002.

- Morris D. People watching: A guide to body language. London: Vintage, 2002.

Links

- 75 signs of body language according to Max Eggert

Body language | it's... What is Body Language?

This term has other meanings, see Body language (meanings).

Body language

gesture

Body language — sign elements of postures and movements of various parts of the body, with the help of which, like with the help of words, thoughts and feelings are structurally formed and encoded, ideas and emotions are transmitted. Body techniques, which include such non-significant movements as facial gestures, head and foot gestures, gait, and various postures, also belong to body language.

|

Contents

|

Classifications

- Body language that exists in parallel and interacts with the language of words in a communicative act (a subject of study of non-verbal semiotics and many other sciences)

- Artificial sign languages with little relation to speech - languages designed for people with hearing impairments

- pantomime language

- ritual sign languages

- professional sign languages and dialects

- gestural visual subsystems of theater and cinema languages, dance languages

The science of body language and its parts is kinesics , along with paralinguistics (the science of sound codes of non-verbal communication) it belongs to the central area of non-verbal semiotics - the science of non-verbal sign systems. Research in the field of non-verbal communication is also carried out by such sciences as applied psychology, ethnography, history, pedagogy, and psycholinguistics. In visual recall, the interlocutor's eyes are usually directed upwards to the left. When constructing (fiction), the eyes are directed upwards to the right. The first reaction to your question or information is important. For example, if a person with a fleeting movement of his eyes looked up to the right and then down to the left, most likely the person is lying: first he constructed an image that he had never seen, and then he begins to select words. Here it is necessary to take into account the fact that some people, preparing their lies in advance, visually well imagine the desired picture. They can remember their lies in the form of visual images and their eyes will be directed upwards to the left. So don't jump to conclusions.

Research in the field of non-verbal communication is also carried out by such sciences as applied psychology, ethnography, history, pedagogy, and psycholinguistics. In visual recall, the interlocutor's eyes are usually directed upwards to the left. When constructing (fiction), the eyes are directed upwards to the right. The first reaction to your question or information is important. For example, if a person with a fleeting movement of his eyes looked up to the right and then down to the left, most likely the person is lying: first he constructed an image that he had never seen, and then he begins to select words. Here it is necessary to take into account the fact that some people, preparing their lies in advance, visually well imagine the desired picture. They can remember their lies in the form of visual images and their eyes will be directed upwards to the left. So don't jump to conclusions.

Well, if you know for sure when your interlocutor is lying to you, then remember the strategy of his lie: what he says at such moments, where his eyes are, how he behaves. Perhaps knowing this person's lying strategy will help you later. Audials, visuals, and kinesthetics differ from each other in eye movements, predicates, timbre and pitch of voice, speed of speech, external data, and a number of other features.

Perhaps knowing this person's lying strategy will help you later. Audials, visuals, and kinesthetics differ from each other in eye movements, predicates, timbre and pitch of voice, speed of speech, external data, and a number of other features.

Visuals strive to dress more beautifully. In a conversation, it is important for them to show themselves and look at others. If there is a choice, in a room where there are several chairs, the visual will choose a place for himself that allows him to see the interlocutor. Always trying to keep his distance. Kinesthetic, on the contrary, is important for close communication, he likes to touch the interlocutor, grab him by the elbow. (Surely you know many such people). It is interesting to observe the communication of the visual and kinesthetic: it turns out a kind of dance. If space permits, the visual will constantly move away from the kinesthetic, and he will constantly come closer. This can continue for a long time until the visual, for example, is pinned to the wall.

If eye contact during a conversation is important for the visual, then he may not expect this from the auditory, which is important to hear. Everything else is secondary. In more detail, you can compare these conditional groups of people according to the information below.

Visual type

Clear voice, not breathy. Loudly (and not intonationally) accentuate the meaning. Trying to stay straight. The line of sight during contact should not be lower than the line of sight of the interlocutor, eye contact is needed ("if you do not look, then you do not hear"). During a conversation, they gesticulate (gestures above the chest), and when they listen, they freeze.

The contact zone is very high - keep a distance when you cross his zone, he (successively): 1) dilates the pupils; 2) raises eyebrows; 3) moves his head back; 4) pushes back the shoulders; 5) departs. They strive to dress beautifully, comb their hair, make beautiful gestures, take beautiful poses. Sensitive to external arrangements (like order) - remove dust when they see it, so that it is beautiful.

Kinesthetic type

Perceive the world with the body. Breathing is abdominal, slow and deep. The voice of a low timbre, slow pace, speech is quiet, soulful, weighty (does not just say so).

Sits closer, touches, likes to “grab” a button, elbow, walk around. He rubs his hands, strokes. The line of sight is below or at the level of the interlocutor's gaze, eye contact with the interlocutor is not necessary, but often interferes: it distracts from one's own bodily sensations. Kinesthetic gestures - below (to the chest).

Auditory type

When interacting, pays more attention to timbre, loudness and other auditory submodalities, “shows with his voice”, copies the voices of others and intonations well. Does not need eye contact when talking, eyes closed.

Usually keeps hands in pockets, rarely makes “stingy” gestures at chest, covers eyes with palm, touches ear, often mutters. Of facial expressions, only the bottom of the face (mouth) is expressive, and so it is amimic. The movements are rhythmic, the head is tilted, the head rests on the hand. Speech measured, with pauses (for internal dialogue). Can tell the same story many times with the same words. Don't interrupt the auditory when he starts talking, otherwise he will start all over again or refuse to talk at all.

The movements are rhythmic, the head is tilted, the head rests on the hand. Speech measured, with pauses (for internal dialogue). Can tell the same story many times with the same words. Don't interrupt the auditory when he starts talking, otherwise he will start all over again or refuse to talk at all.

Undoubtedly, a person is much more complex than any of the models for dividing people into visuals, auditory and kinesthetics. (as well as other types not discussed in this article). Often there are mixed types of people. You need to keep in mind that at the moment your partner's strategy is close to the behavior of any of the types described above.

Peculiarities of functioning of signs of different nature in speech

Communicative activity in human life plays one of the most important roles. The ability to verbally communicate a message separates people from the natural world, but, remaining part of it, we have a unique ability to unconsciously and consciously read each other's body language: gestures, various postures, voluntary and involuntary movements. In 1963, the outstanding Russian linguist A. A. Reformatsky, discussing the nature of various sign systems, described their relationship in one communicative act. He emphasized the impossibility of modeling communication systems and the thought process itself without studying how a non-verbal text relates to a verbal one. A. A. Reformatsky came to the conclusion that the recoding of information is not the only important process in the act of oral communication. During communication, sign information is processed in parallel by different systems: sign systems of different nature "somehow compete in principle, but do not overlap, but represent a more complex relationship" (Reformatsky 1963). Thus, body language as a non-verbal part of communication, and sometimes the only part of it (in the case of artificial sign languages that do not correlate with speech: "Russian language of the deaf-mutes, Amslen - a sign system used by the deaf-mutes in North America, Amerind" - "language of hands" deaf and dumb North American Indians, Britlen - the language of the deaf and dumb countries of the British Commonwealth, the deaf and dumb languages of Italy, Sweden and many others) occupies an exceptionally important position in the history of culture.

In 1963, the outstanding Russian linguist A. A. Reformatsky, discussing the nature of various sign systems, described their relationship in one communicative act. He emphasized the impossibility of modeling communication systems and the thought process itself without studying how a non-verbal text relates to a verbal one. A. A. Reformatsky came to the conclusion that the recoding of information is not the only important process in the act of oral communication. During communication, sign information is processed in parallel by different systems: sign systems of different nature "somehow compete in principle, but do not overlap, but represent a more complex relationship" (Reformatsky 1963). Thus, body language as a non-verbal part of communication, and sometimes the only part of it (in the case of artificial sign languages that do not correlate with speech: "Russian language of the deaf-mutes, Amslen - a sign system used by the deaf-mutes in North America, Amerind" - "language of hands" deaf and dumb North American Indians, Britlen - the language of the deaf and dumb countries of the British Commonwealth, the deaf and dumb languages of Italy, Sweden and many others) occupies an exceptionally important position in the history of culture.

From the history of body language research

The science of body language is considered to be kinesics, although recently it has been customary to more narrowly specialize the objects of its study: the study of hand gestures, mimic gestures, head and foot gestures, postures and symbolic body movements. All these units of non-verbal communication are combined in the concept of "gesture" - from lat. gestus, meaning to do, wear, be responsible, control, perform, perform, etc. The well-known researcher of sign language A. Kendon, exploring the evolution of this term, noted that in Roman treatises on the behavior of speakers, for example, Cicero and Quintilian, "gesture" was defined as the rules for using the capabilities of one's body, significant movements of the arms, legs, body and face, which brings this term closer to its modern use - an interactive sign of everyday non-verbal human behavior.

Body language, occupying an important position in the history of culture, is the subject of research in rhetoric, medicine, psychology, pedagogy, art, chirology (the language of lines and tubercles of the hands), chironomy (the art of manual rhetoric) and physiognomy, the doctrine of the manifestation of the inner qualities of a person in features and facial expressions.

Major body language studies

- J. Balwer was one of the first to write a book on body language in 1644, where hand language was viewed as a natural natural formation, as opposed to an artificial invented language of words.

- J. Kaspar Lavater, a pastor from Zurich, in 1792 published an Essay on Physiognomy, the first systematic study of body movements, which describes in detail the relationship between human facial expressions, body configurations and types of personality traits of a person.

- G. K. Lichtenberg, an outstanding German scientist and writer, the main opponent of Lavater, wrote a book in 1765 in which he criticized him for an overly simplified approach to physiognomy: for striving to explain the world, proceeding only from consciousness, in isolation from the real world , from practical human activity

- C. Bell, anatomist, neurophysiologist, artist and surgeon, was one of the first to become interested in the expression of emotions on the human face.

In 1844, doing research in the field of functional analysis of the nervous system, he concluded that all strong feelings are accompanied by a change in breathing and muscular activity of the face and trunk under the influence of changed breathing patterns.

In 1844, doing research in the field of functional analysis of the nervous system, he concluded that all strong feelings are accompanied by a change in breathing and muscular activity of the face and trunk under the influence of changed breathing patterns. - C. Darwin and E. Kretschmer in 1920 conducted research to describe the links between human emotions, his character and body type, the links between human facial expressions and the meanings of these non-verbal units.

- D. Bonifacio, D. Batista del Porta and F. Bacon in the late Renaissance, the heyday of the study of body language, in 1616, in their treatises on non-verbal communication, argued that there is a universal sign language, understandable to all peoples, body language, which also speaks of the character and temperament of the individual.

- A. Kendon, D. Morris, G. Kreidlin, modern sign language researchers who pay more attention to the interaction of verbal and non-verbal codes, as well as to the peculiarities of the body language of individual cultures.

Body language and natural language

The underlying processes that underlie natural language and body language are essentially similar, which makes their parallel existence in a communicative act possible. The following are facts confirming their similarity.

Classic "shish" ("fig", "muzzle", "fig")

- Each element of non-verbal language, like the element of natural language, can become a unit of conventional agreement and acquire contextual meaning, for example, waving a handkerchief, forefinger and thumb in the ring, acquiring different meanings depending on the culture of the countries.

- Under certain conditions, meaning is conveyed from one subject to another either only with the help of gestures, or only with words, or with a combination of both signs.

- Gestures, like linguistic units, are mostly symbolic signs, they form the lexicon of body language, and gesture combinations can form semiotic gesture acts like speech acts.

- Many signs of a certain language can be translated into the corresponding verbal language, as well as into the sign language of another country. The translation problems associated with non-verbal language are basically the same as those of natural languages.

- Gesture behavior of people changes in space, in time, as well as under the influence of economic and cultural conditions, which is typical for natural language.

Thus, the parallel existence of signed and natural language can be traced quite clearly. Moreover, research in this area confirms that their interaction enriches the transmission of meaning and emotions, clarifies and enhances the meaning of information, creating vivid imagery of words. But, despite the presence of common properties, between body language and natural language there are fundamental differences.

- All natural languages are composed of relatively stable and discrete units, which is not the case for body language where there is no agreement on the form, meaning and use of non-verbal units.