Lithium brain fog

Lithium Therapy, Bipolar Disorder- and Neurocognition

Gin S. Malhi, MD, Tim Outhred, PhD

Psychiatric Times, Vol 34 No 1, Volume 34, Issue 1

Functional mood stability can be attained with lithium therapy, but guidelines on how to get there have become increasingly sophisticated.

Lithium has a global history-discovered initially by Danish siblings (Carl and James Lange) in the 19th century and then rediscovered as a treatment for manic-depressive illness in the mid-20th century by John Cade, an Australian. Sometime later, following publication of the first clinical trials, lithium was introduced to clinical practice in the US and across Europe.

In clinical practice, functional mood stability-which can on occasion be achieved with optimum lithium therapy-is the gold standard that both clinicians and patients strive to attain. To facilitate this endeavor, guidelines on lithium therapy have become increasingly sophisticated; they not only provide therapeutic indications and plasma levels with respect to efficacy, but also inform practitioners about how potential adverse effects can be minimized or avoided.

CASE VIGNETTE

Margaret, a 36-year-old with bipolar I disorder, is referred for an appraisal of treatment strategies following the resolution of an episode of depression. Although the episode was relatively moderate in severity and she did not require hospitalization, suicidality featured strongly during the episode. She currently takes 1000 mg of lithium and 400 mg of lamotrigine daily.

She reports that her mood is better but says that she has been “slowing down at work.” She is finding it difficult to perform mental arithmetic, something she had previously been very adept at doing. She is assessed for cognitive symptoms using the Lithium Battery–Clinical; in addition, a battery of cognitive tests reveals scores in the normal range. Her plasma lithium level (0.7 mmol/L) is within the normal range for maintenance therapy.

Given the presence of manic-mixed features and a recent episode occurrence, as well as subjective chronic cognitive impairment, it is recommended that valproate be substituted for the lamotrigine. Once the transition takes place, the dose of lithium is gradually decreased to achieve a plasma level of 0.5 mmol/L. During this period, Margaret regularly visits her primary physician for clinical assessment and monitoring. She is understandably anxious about the changes to her medication regimen but maintains mood stability and only reports anticipated adverse effects.

Once the transition takes place, the dose of lithium is gradually decreased to achieve a plasma level of 0.5 mmol/L. During this period, Margaret regularly visits her primary physician for clinical assessment and monitoring. She is understandably anxious about the changes to her medication regimen but maintains mood stability and only reports anticipated adverse effects.

When re-evaluated by her regular psychiatrist after 2 weeks, Margaret reports noticeable improvement in her cognitive symptoms. Twelve months later, Margaret remains well and continues to work full time. She is monitored regularly and comprehensively every 3 months.

This case highlights the fact that maintenance monotherapy is not always possible in the treatment of bipolar disorder and that therapy must always be tailored to individual needs. The most important component is patient engagement in the therapeutic process and clinical decision-making. This is best achieved by understanding the patient’s concerns and informing her fully of risks and benefits while ensuring regular follow-up.

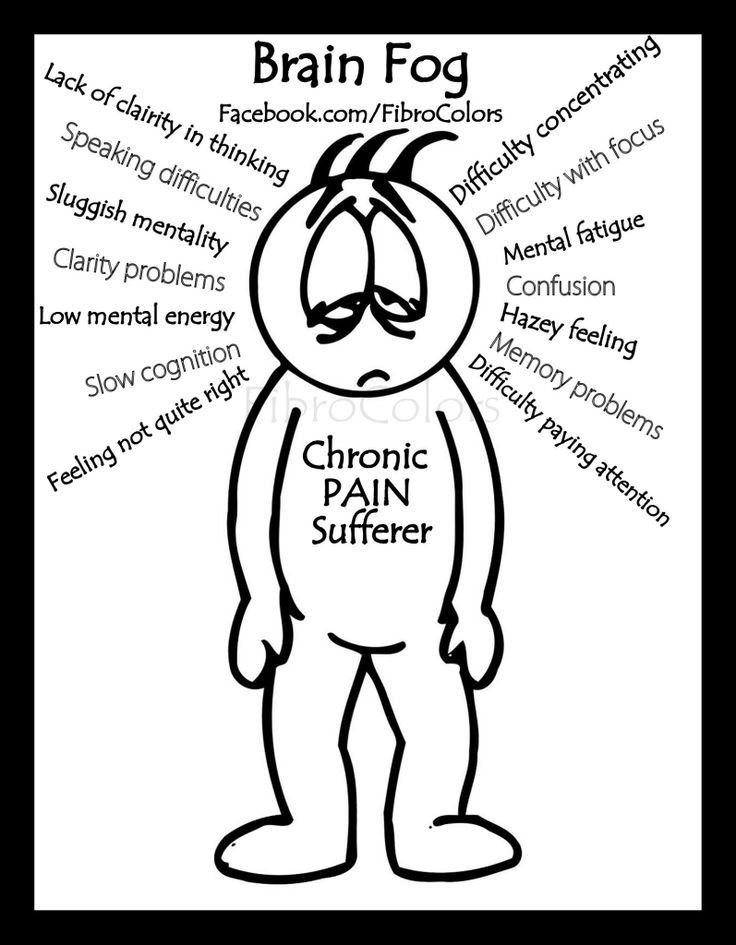

A common complaint made by those who take lithium, but one which may easily be overlooked, is cognitive compromise. Clinically, patients describe this as “brain fog”-an elusive admixture of complaints regarding attention, concentration, and memory occurring in conjunction with a slowing of thought processes. Clinicians usually regard these as symptoms of the illness, whereas patients are more inclined to attribute them to the effects of medications. In reality, both the illness and its treatment likely contribute to these symptoms, which makes disentangling the various causes extremely difficult. It is an important clinical issue because patients are likely to discontinue treatment on the basis of such concerns and the cognitive adverse effects do in reality limit patients’ ability to function-both occupationally and socially.

Although lithium provides a promising opportunity to attain long-term mood stability, it sometimes comes at considerable cost and forces psychiatrists and their patients to constantly balance remaining well on the one hand by preventing symptoms of illness and remaining functional on the other by addressingtolerability.

Stabilizing mood and improving cognition

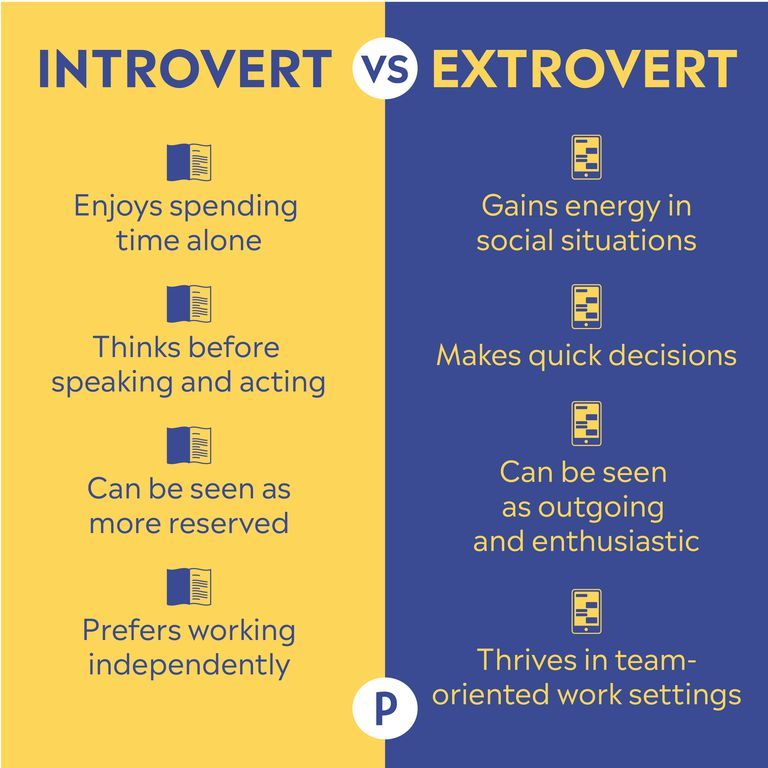

In addition to its effects on mood, lithium is known to alter neurocognition-improving some functions while impairing others. These opposing and complex actions likely occur both acutely and long term and are probably subject to changes in plasma levels. Lithium has profound effects on wellness in a significant proportion of patients with bipolar disorder, who remain episode-free and highly functioning for many years solely with lithium monotherapy.1 Lithium treatment response is helped by the ability to optimize its impact and tolerability with the use of plasma lithium concentrations to guide dosage adjustments. With this in mind, the Lithiumeter (Figure 1), a tool for balancing efficacy and tolerability in clinical practice, has recently been updated with the inclusion of additional guidance based on new evidence (version 2.0). 2

In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in lithium therapy that has increased awareness of its benefits and debunked some of the myths tarnishing its tolerability profile. In fact, key new studies have shown that severe problems are relatively rare and that assiduous monitoring of lithium plasma levels minimizes the likelihood of lithium toxicity and the potential risk of renal and thyroid dysfunction.3

In fact, key new studies have shown that severe problems are relatively rare and that assiduous monitoring of lithium plasma levels minimizes the likelihood of lithium toxicity and the potential risk of renal and thyroid dysfunction.3

While lithium monotherapy is the ideal, for most patients who have bipolar disorder, satisfactory prophylaxis with lithium is only possible when it is used in combination with other agents. In patients with predominantly manic episodes, lithium in combination with valproate is a useful option. Similarly, lamotrigine can be used in conjunction with lithium in cases with predominantly depressive episodes. In both scenarios, lithium combination therapy may also enable the use of lower doses of individual agents-thus maintaining efficacy while achieving greater tolerability. In this context, atypical antipsychotics and antidepressants can be conceptualized as rescue treatments that should be used mainly during manic and depressive episodes, respectively. Longer-term use poses considerable physical health risks and the possibility of a treatment-emergent affective switch.4-6 Hence, it is widely recommended that once the acute symptoms of an episode resolve in response to rescue treatments, dosages are reduced as quickly as possible.

Longer-term use poses considerable physical health risks and the possibility of a treatment-emergent affective switch.4-6 Hence, it is widely recommended that once the acute symptoms of an episode resolve in response to rescue treatments, dosages are reduced as quickly as possible.

Lithium also appears to have neuroprotective effects that are thought to be achieved by initiating and then maintaining a cascade of cellular processes, among which glycogen synthase kinase 3β inhibition appears to be key.7 Lithium’s many intracellular actions are thought to underpin its diverse therapeutic effects. When treating bipolar disorder with lithium, it is difficult to parcel out the effects of the agent from those of the illness, especially since lithium also seems to have positive effects on maintaining cognitive function over the long term. Hence, alongside its use in mood disorders, lithium is being studied in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases, in an attempt to harness its potential neuroprotective properties. 8,9

8,9

Intriguingly, independent of its effects on mood stability, lithium is a highly effective anti-suicidal agent, and much lower plasma concentrations than necessary for treating mood disorders may serve to reduce the risk of suicide.10,11 This means that lithium can be used to tackle suicidality, but in practice its use needs to be tempered against the individual’s conviction to commit suicide. Lithium’s anti-suicidal action is likely to be in part a consequence of its moderating effects on impulsivity andirritability.12

Altered neurocognition

Lithium has a complicated neurocognitive profile. It produces impairment across some domains, while preserving others-with these effects seemingly more apparent in those more vulnerable to the deleterious effects of bipolar disorder. A recent review concluded that lithium administration alters specific aspects of neurocognition and that these effects are perhaps cumulative-increasing with the duration of treatment. 13 The effects are likely to occur via direct and indirect mechanisms (eg, via altering mood) and may be the product of low-level chronic toxicity or repeated episodes of acute toxicity.

13 The effects are likely to occur via direct and indirect mechanisms (eg, via altering mood) and may be the product of low-level chronic toxicity or repeated episodes of acute toxicity.

In 2007, we examined 25 patients with bipolar I disorder over a period of 30 months in order to capture depressed and hypomanic mood episodes as well as periods of euthymia.14 Patients were compared with healthy cohorts on neurocognitive tests over time. This study provided the first indications that some neurocognitive impairments are mood-state–related, while others are more chronic and remain with patients even when they are relatively well.

Specifically, when patients were depressed, total recall scores on the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) were lower than during periods of euthymia or hypomania. This suggests that verbal memory ability is impaired during episodes of depression. Compared with healthy controls, depressed and hypomanic patients had relatively impaired executive function, memory and attention, and motor abilities. When patients were relatively well, they continued to show subtle impairments in attention and memory relative to healthy controls; this suggests that these impairments are chronic and do not necessarily recover with symptom improvement. Since this early study, a number of trials have produced similar results, which suggest that the neurocognitive profile of bipolar disorder is dynamic and subject to further modification with the use of medications.13,15

When patients were relatively well, they continued to show subtle impairments in attention and memory relative to healthy controls; this suggests that these impairments are chronic and do not necessarily recover with symptom improvement. Since this early study, a number of trials have produced similar results, which suggest that the neurocognitive profile of bipolar disorder is dynamic and subject to further modification with the use of medications.13,15

The impact of lithium therapy on neurocognition adds an additional layer of complexity for researchers, but in practice the broad range of effects is concordant with the experience of patients and clinicians. In research settings, lithium appears to have virtually no effect on concentration or on short- or long-term memory, but it does have modest effects on psychomotor speed, verbal memory, and verbal fluency.13 Therefore, lithium may be acting-at least in part-on the impairments displayed when patients are experiencing an episode. However, the effects of the disorder and lithium therapy are subtle, and in a clinical setting, they may not always be detectable.

However, the effects of the disorder and lithium therapy are subtle, and in a clinical setting, they may not always be detectable.

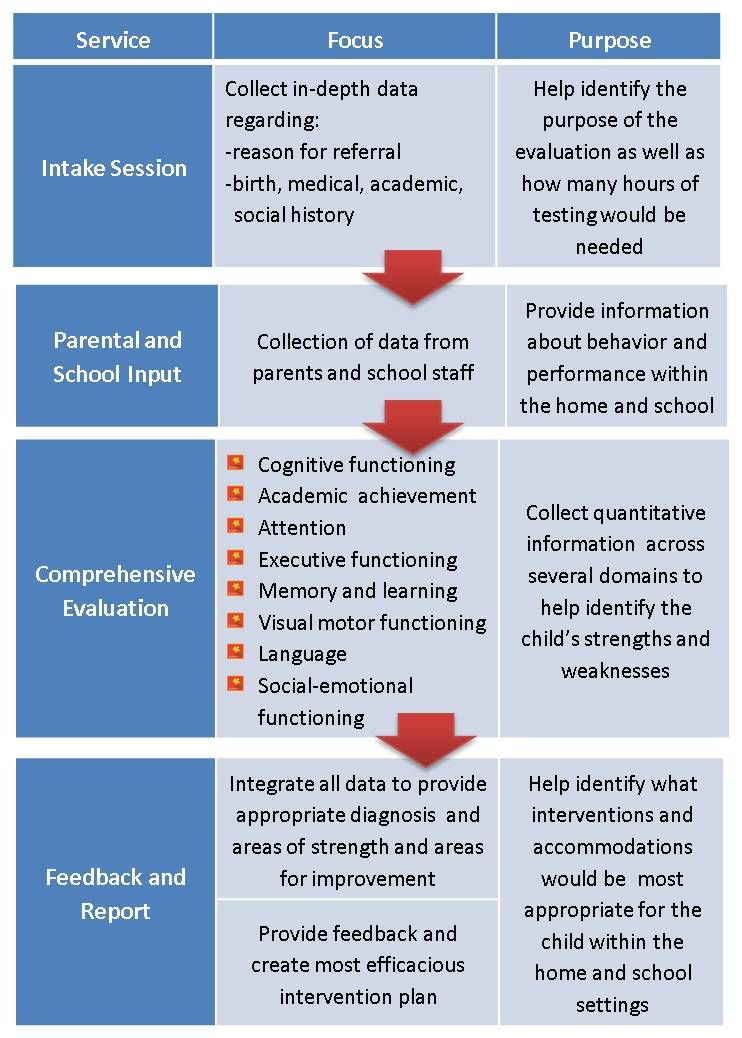

To map the neurocognitive changes that occur in patients with bipolar disorder who undergo lithium treatment, we propose that clinicians use the Lithium Battery–Clinical (Figure 2) to assess the neurocognitive effects of lithium.

13 This tool allows clinical complaints to be correlated with changes to the illness profile and, in particular, to changes in treatment. The adoption of such a tool automatically enhances the attention paid to neurocognition in clinical settings and provides a richer understanding of contributing factors in patient illness. In turn, this should assist in formulating treatment strategies that focus on improving neurocognition as well as on normalizing mood-and thereby enhance overall functioning. Specifically, lithium dose and plasma blood levels should be modified and monitored with neurocognitive components in mind, as part of an overarching clinical strategy to attenuate adverse effects and identify an optimal therapeutic level that is effective and safe and facilitates functioning.

Untangling neurocognitive domains

Untangling the domains of neurocognition that are modulated by lithium in the context of a fluctuating and complex illness such as bipolar disorder is a significant challenge. The Lithium Battery–Clinical offers a systematic approach for clinical practice settings, but to elucidate the causes and develop better treatments, a detailed scientific understanding is required. Until such a time that specific neurocognitive profiles can be mapped out, and the illness and the effects of treatment can be targeted and easily discernible, clinicians will have to rely on their judgment to provide advice and make treatment decisions on the basis of bedside tests.

Guidance based on evidence is urgently needed, and a useful first step is recognition of the problem. Even simple acknowledgment of neurocognitive compromise, as well as engagement with patients regarding their concerns, is likely to reassure them that the problems they sense are indeed real and in many cases can be ameliorated by optimizing therapy.

Clinical recommendation

Historically, neurocognitive outcomes and deficits have not been viable areas for treatment or for quantifying neurocognitive changes in patients. To understand the neurocognitive effects of bipolar disorder and its treatment, we propose that future research employ a more sophisticated research version of the Lithium Battery that includes specific neuropsychological tests. Over time, this approach is likely to reveal which medications are better suited to improving mood while preserving neurocognition. In the meantime, clinicians can employ the Lithium Battery–Clinical for noting and managing neurocognitive concerns as part of routine clinical practice during lithium treatment, and should do so regularly.

Neurocognition plays a significant role in functioning, and treatment effects and patient concerns affect compliance. Effective and more specific treatment strategies are urgently needed to improve outcomes and ameliorate this aspect of illness burden in bipolar disorder. Moreover, a better understanding is needed of the tolerability of lithium in patients for whom this treatment can be highly beneficial.

Moreover, a better understanding is needed of the tolerability of lithium in patients for whom this treatment can be highly beneficial.

Disclosures:

Professor Malhi is Head of the Department of Psychiatry, Royal North Shore Hospital, and Chair of Psychiatry, University of Sydney, Australia. Dr. Outhred is Postdoctoral Research Associate, Department of Psychiatry, Royal North Shore Hospital, University of Sydney. Professor Malhi and Dr. Outhred have received grant or research support from the National Health and Medical Research Council, Ramsay Health, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, and Sydney Medical School Foundation. Professor Malhi has received grant or research support from NSW Health, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly & Co, Organon, Pfizer, Servier, and Wyeth; he has been a speaker for AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly & Co, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Pfizer, Ranbaxy, Servier, and Wyeth; and he has been a consultant for AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly & Co, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, and Servier.

Note: The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

References:

1. Grof P. Excellent lithium responders: people whose lives have been changed by lithium prophylaxis. Lithium. 1999;50:36-51.

2. Malhi GS, Gershon S, Outhred R. Lithiumeter: version 2.0. Bipolar Disord. 2017 (in press). Accepted for publication October 27, 2016.

3. Hayes JF, Marston L, Walters K, et al. Adverse renal, endocrine, hepatic, and metabolic events during maintenance mood stabilizer treatment for bipolar disorder: a population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002058.

4. Malhi GS, Bassett D, Boyce P, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:1087-1206.

2015;49:1087-1206.

5. Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:495-553.

6. Bauer M, Gitlin M. The Essential Guide to Lithium Treatment. New York: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

7. Malhi GS, Outhred T. Therapeutic mechanisms of lithium in bipolar disorder: recent advances and current understanding. CNS Drugs. 2016;30:931-949.

8. Kessing LV, Forman JL, Andersen PK. Does lithium protect against dementia? Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:87-94.

9. Kessing LV, Sondergard L, Forman JL, Andersen PK. Lithium treatment and risk of dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1331-1335.

10. Cipriani A, Hawton K, Stockton S, Geddes JR. Lithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f3646.

BMJ. 2013;346:f3646.

11. Mauer S, Vergne D, Ghaemi SN. Standard and trace-dose lithium: a systematic review of dementia prevention and other behavioral benefits. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48:809-818.

12. Malhi GS, Bargh DM, Kuiper S, et al. Modeling bipolar disorder suicidality. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:559-574.

13. Malhi GS, McAulay C, Gershon S, et al. The Lithium Battery: assessing the neurocognitive profile of lithium in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18:102-115.

14. Malhi GS, Ivanovski B, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, et al. Neuropsychological deficits and functional impairment in bipolar depression, hypomania and euthymia. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:114-125.

15. Torres IJ, Malhi GS. Neurocognition in bipolar disorder. In: Yatham LN, Maj M, eds. Bipolar Disorder: Clinical and Neurobiological Foundations. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012:69-82.

Related Article >>>

Bipolar & Memory: Managing “Bipolar Brain Fog”

Post Views: 83,303

Views

Feeling scatterbrained? Can’t remember a thing? It may be “bipolar brain fog”—and you can manage it.

Photo: Siri Stafford / DigitalVision via Getty ImagesManaging Bipolar Complicated by Cognition Problems

“I’m the PhD down the hall whose memory fails during critical discussions at the office,” says Debra.

Debra, 48, is a behavioral scientist with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. She leads research and oversees a team of data analysts in the Division of Violence Prevention.

Before her bipolar diagnosis six years ago, she sometimes had trouble keeping focused. Now recall is a bigger problem, especially if she’s expected to dredge up dates or statistics during a meeting or keep track of details after an impromptu encounter.

“I ask people to schedule meetings rather than have these hallways conversations when we need to make decisions,” she says.

In meetings, she takes copious notes to jog her memory.

“I scribble as fast as I can … sometimes so fast I can’t read my own notes,” she reports. “I just have to chuckle when, ‘This research should move ahead,’ turns into, ‘This rabbit should go to bed.’”

Psychiatrists and researchers are coming to appreciate that memory lapses and other neurocognitive problems—disorganization, groping for words, difficulty learning new information—can go hand in hand with the more obvious mood and behavioral symptoms that characterize bipolar.

Joseph Goldberg, MD, a psychiatrist and associate clinical professor of psychiatry at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City, helped put these “thinking” problems on the bipolar map. He’s co-editor of Cognitive Dysfunction in Bipolar Disorder: A Guide for Clinicians, which came out in 2008.

Goldberg says the book builds on “literally hundreds of studies” analyzing aspects of cognition in patients with bipolar disorder.

He mentions an influential Spanish study, published in the American Journal of Psychiatry in February 2004. In every phase of the illness (depression, mania and remission), researchers found marked deficits in verbal memory and what’s known as “frontal executive tasks.”

Think of it this way: The brain is organized like a big office with specific departments designated to complex tasks such as decision-making, attention, verbal memory, spatial memory, motor speed and skill, and logical reasoning.

The frontal lobes of the brain contain circuitry that acts, in essence, like a hardworking executive secretary. Information comes into the frontal lobe and the secretary notes it, organizes it, and sends out messages to the brain’s different departments to get things done.

Faulty processing in this executive center can lead to cognitive deficits that affect awareness, perception, reasoning and judgment, Goldberg says.

The hippocampus, meanwhile, serves as a kind of file clerk for recording new memories and sending them on to permanent storage. Bipolar has been associated with shrinkage of the hippocampus, which may explain difficulties in acquiring and accessing various kinds of data.

Bipolar has been associated with shrinkage of the hippocampus, which may explain difficulties in acquiring and accessing various kinds of data.

Goldberg notes that many aspects of intellectual functioning carry on just fine in people with bipolar—sometimes even better than in the general population. The glitches seem limited to specific areas: verbal memory, executive organization, “processing speed” and attention.

Daily Cognitive Difficulties with Bipolar

Attention—the ability to focus on a task or conversation, tune out distractions, and, ultimately, filter information into working memory—is the gateway to learning, memory and other higher cognitive processes, says Frederick Goodwin, MD, a leading clinical researcher on bipolar disorder who is now based at George Washington University.

All of those functions can go haywire during depression and mania, of course. In fact, manic symptoms can mimic attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

On the other hand, ADHD occurs “at rates substantially greater than the general population” in individuals with bipolar and major depressive disorder, according to researchers with the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments.

Their treatment recommendations, published in the February 2012 issue of the Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, note the importance of accurate diagnosis and careful pharmacotherapy, since some ADHD medications can trigger mania. Mood stabilization should come first, they write, before addressing ADHD symptoms.

But what about scattered attention, memory glitches and other cognitive deficits that practitioners never hear about from their patients with bipolar?

Goodwin notes a change in thinking since Manic-Depressive Illness, the now-classic textbook he wrote with Kay Redfield Jamison, came out in 1990. Not more than a decade ago, he says, professionals checked off a host of mood and behavioral symptoms and didn’t pay much mind to cognitive factors.

It didn’t help that the problems can be subtle and unlikely to show up in an office interview—especially when verbal ability remains sharp.

Cognitive deficits can be subtle or severe, but studies show that as many as a third of people with bipolar I have cognitive problems that disrupt their lives.

Bipolar brain fog can complicate everything from succeeding in school to paying the bills. Rick of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, is less confident behind the wheel these days because of “near misses and some dents.” He blames poor concentration and slowed motor skills.

“I used to pride myself on being an excellent driver,” says Rick, 62, who crisscrossed the continent during his 25 years as a communications specialist in the Canadian Forces. “I didn’t even get any tickets.”

Rick says predominantly high moods helped him succeed socially, in sports and in his career. With time, however, he began to notice it was harder to follow a train of thought. Loud talking and other noise made it tough to focus on what he was doing.

His coordination also deteriorated, leaving him with a tendency to lose his balance on a ladder, stumble while walking, or nick himself when working with tools. Escalating mood shifts led to his bipolar II diagnosis a few years ago.

Rick still captains the car on local errands, but it helps to have his spouse on board as navigator, noting where to turn or when to slow down. As a military wife, she managed the family and handled all the relocations; now more than ever, Rick says, she’s “the decision-maker and my assistant.”

As a military wife, she managed the family and handled all the relocations; now more than ever, Rick says, she’s “the decision-maker and my assistant.”

In addition to checking in daily with his wife to make sure he hasn’t overlooked any obligations or appointments, Rick follows a routine that includes activities in the morning when he feels most alert, a nap in the afternoon when energy and attention flag, and a strictly regimented bedtime.

“It’s a long journey,” he says of learning how to manage his fluctuating symptoms, “but I believe that hope is the best car to drive in.”

Complicated Causes of Neurocognitive Concerns with Bipolar

The fact that neurocognitive problems linger after symptoms subside—and can be present before a bipolar diagnosis is made—makes scientists think that these disturbances are a core and consistent feature of the illness.

A Canadian study that appeared in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry in September 2010 found that attention, recall, and several aspects of executive functioning were compromised even at onset of the first manic episode.

Researchers are trying to learn more about what areas of the brain are vulnerable to the disease process and what role the course of illness plays.

Moira A. Rynn, MD, an associate professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center, is involved in a multi-center study on pharmacological treatment for adolescents that includes a detailed cognitive battery given at baseline and again every two years.

Rynn says it can be difficult to assess cognitive impairment in a “snapshot” evaluation because individuals come with their own set of cognitive strengths and weaknesses. A “longitudinal” study such as she is doing can reveal whether each participant’s learning difficulties get better or worse, and shed light on why.

“There is a need to do careful standardized assessments over time, controlling for the type of treatments given,” she says. “We do need to know whether the severity and frequency of episodes make cognitive problems more severe, and what is the impact of medication treatment over time. ”

”

Goodwin says that while the pathological underpinnings of the disease itself may play a role in cognitive problems, there are a number of other explanations to consider. All kinds of medications can affect the brain regions that control cognitive function. So can medical illnesses such as fibromyalgia and cancer, drug and alcohol use, anxiety, and stress.

Sue Marsh (not her real name) is a walking example of that interplay. Marsh, 59, recalls that learning was difficult for her as a kid. She was diagnosed with adult attention deficit disorder in her 30s. Still, she was driven to excel right through graduate school, then as a speech pathologist, and later in medical sales. She made good money and balanced a busy career with raising a family.

Her divorce in 2002 led to depression. When she went through therapy for breast cancer three years later, the treatment apparently triggered bipolar symptoms. Her diagnosis and treatment changed accordingly.

Now, seven years later, she frequently gets lost when she leaves the house. She can’t get out the door without reading dozens of slips of paper that line a path from her bathroom to the kitchen to the door that will send her out into the world. Some of the notes read: Brush teeth. Take pills. Find keys. Find phone. Put coat on. Lock door.

She can’t get out the door without reading dozens of slips of paper that line a path from her bathroom to the kitchen to the door that will send her out into the world. Some of the notes read: Brush teeth. Take pills. Find keys. Find phone. Put coat on. Lock door.

“I just can’t function the way other people do,” says Marsh. Without the notes throughout her house, “I don’t know how I would even get out in the morning.”

Every brain scan and neuropsychiatric report spits out the same result: problems with executive function. She is now on disability. Three words on a note card by the door remind her: Keep it simple.

“I’ve had to revamp my dreams,” she says.

Working through Cognitive Difficulties

Those who remain employed may have to work a little harder. Kyle, 33, says friends used to call him Superman because, “I could do a million things at once and do it well.”

He discovered the hard way that he needs to stay on medication to stave off psychosis and extreme behavior. He was fired from his previous job during a bout of unrecognized mania—although to this day, he can’t remember anything that happened during the episode.

He was fired from his previous job during a bout of unrecognized mania—although to this day, he can’t remember anything that happened during the episode.

Now the effortless multitasking of hypomania is a thing of the past. He’s made accommodations to handle his responsibilities as a production engineer at a small medical device company in Bloomington, Indiana.

“I’ve learned I can focus on one thing and do that,” he explains. “I have to consciously think, ‘This is what I’m doing, this is what I’ve done, and this is what I’m going to do when I get back to it.’”

Because he can’t keep all the balls juggling in his head anymore, he makes sure to note appointments on his calendar and jot down reminders about important tasks.

Kyle says he was upfront about his altered abilities when he was hired nearly two years ago, but he’s done well enough to win his supervisors’ support. During a recent psychiatric hospitalization, he says, the firm’s owner came by to let him know his job was waiting.

Debra, the CDC scientist, is also happy with the feedback from her superiors. In any event, she says, her bipolar diagnosis at 43 was a life-saving discovery—a fair swap for the slowdown of a few brain cells.

“It’s one of those side effects I have to deal with,” she says, “because I’m not going to stop taking the medication.”

Despite her positive evaluations, Debra admits to feeling incompetent at times because of her quirky memory. Still, she says, living with bipolar disorder also has its advantages. For Debra, lifelong traits such as creativity and increased productivity far outweigh the downside of her lapses.

“It’s about finding your strengths,” she says, “and capitalizing on them.”

• • • • •

SEEKING SOLUTIONS FOR MEMORY PROBLEMS WITH BIPOLAR

As new evidence emerges about cognitive deficits associated with bipolar disorder, clinicians are more apt to take such problems into consideration during evaluation and treatment.

A number of neuropsychological tests are proving helpful in identifying problems that can make everyday functioning difficult. Some tests are designed to pick up misfires in memory and attention, while others measure planning skills and “response initiation”—that is, how quickly and appropriately someone responds to stimuli.

Ivan Torres, PhD, a clinical associate professor of psychiatry at the University of British Columbia whose research focuses on cognition in bipolar, says that cognitive test scores correlate with how well people with bipolar are able to function in the real world.

What to do with the information is less clear.

“We are just in the beginning stages of identifying ways to help patients with these cognitive problems,” Torres says.

Current research is looking at the possible benefits of certain medications, cognitive remediation therapy, and rehabilitation interventions used with brain injury and stroke patients.

“At the very least,” says Torres, “we are in a position to provide education to patients about the cognitive difficulties that they may experience, and to come up with strategies for working around these problems in daily life. ”

”

Breaking complex tasks into smaller units, making the environment less distracting, and creating structure around daily duties can counteract deficits in focus and organization, he says.

Cues, prompts, reminders, and repetition can help with learning and memory problems.

In his work with patients whose memory is unreliable, psychiatrist Joseph Goldberg recommends similar tactics: sticky notes, appointment calendars, and a technique called “chunking”—splitting information into bite-size pieces that are easier to remember.

Betty of Port McNicoll, Ontario, relies on her cell phone. Her son originally gave her a phone with a keyboard so she could save money by texting him rather than calling. She discovered other benefits.

“My phone has a calendar in it, so I just started using my phone to set off a reminder that I had to do something or go somewhere. I even use it to wake me up in the morning,” she says.

After two decades of disabling depression and untreated hypomanic symptoms, Betty got a new doctor in 2010 who gave her a bipolar diagnosis. Now 65 and stable, she says she’s “always had problems with my cognitive abilities. It’s just gotten worse as I’ve got older.”

Now 65 and stable, she says she’s “always had problems with my cognitive abilities. It’s just gotten worse as I’ve got older.”

In her low-tech days, she says, she would miss appointments and forget that she was supposed to meet someone or pick something up—even with “my pieces of paper to remind me” and a calendar in her purse.

“The phone works a whole lot better,” she says.

Betty also adopted a counterintuitive therapy: the game of bridge, which favors players who can keep track of which cards have been put down. Somehow the mental exercise strengthens her erratic memory, she reports.

Her involvement with the game has been so successful, she says, “I not only play it, I teach it.”

Printed as “The Cognitive Connection,” Summer 2012

cognitive dysfunction, hypomania, memory, summer 2012

About the author

Related

90,000 terrible and incomprehensible illness affects those who have been ill with Covid: the brain fog deprives the mind ofKomsomolskaya Pravda

Health and Health

Anna Kukartseva

October 10, 2022 11:25

Patients from 20% of patients report fogs in the fog in brain fog three months after being infected with coronavirus

The cause of brain fog is coronavirus. Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock

Brain fog after coronavirus ... Those who have experienced this condition describe it in different ways, but it’s not pleasant enough - you acutely feel stupid, and you forget everything. The reason for this effect is the coronavirus. Now many who have been ill with the "crown" can experience for themselves what it is like for those who suffer from Alzheimer's disease. The symptoms are almost the same. But why does it come from? Covid made us stupid - how?

The popular magazine The Atlantic collected comments from doctors and patients - those who had this strange disease on themselves, those who treated and observed. The author of the investigation is Edie Yong , who won the Pulitzer Prize for reporting during the pandemic. We have read and tell you.

STRANGE ILLNESS. START

On March 25, 2020, Hannah Davis was texting two friends when she realized she couldn't understand one of their messages. She looked at the letters, said what she read aloud, and understood absolutely nothing. At that moment, her former happy life disappeared.

Hannah was an artificial intelligence specialist who could easily analyze complex systems. Now he hits a mental wall, even when faced with simple tasks like filling out forms on websites. Her memory, once bright, colorful, with smells and images, now seems tattered and fleeting. The old daily routines—grocery shopping, cooking, cleaning—are excruciatingly difficult. Her inner world - what she calls "daydreaming, planning, imagining" - is gone. The fog has perverted every area of her life. It's been over 900 days. All other consequences of the transferred covid disappeared. And the fog in her brain never dissipated.

THE MOST DESTRUCTIVE AND THE MOST MISTAKE

“Brain fog is by far one of the most disabling and devastating symptoms of long covid. And the most misunderstood,” said Emma Ladds, a primary care specialist at the University of Oxford.

Between 20 and 30 percent of patients report brain fog three months after contracting covid. It can affect people who are mildly ill and have almost no symptoms. But "brain fog" is observed in 60-80 percent of those who have been seriously ill and for a long time. Moreover, it also affects young people in the prime of their mental abilities.

Those who have experienced this state find it difficult to compare it to something worse than the slow thinking that accompanies a hangover, stress, or fatigue. And this is definitely not psychosomatics: the disease actually changes the structure and chemistry of the brain.

"And it's definitely not related to depression - it has a different chemistry," says Joanna Hellmuth, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Francisco. - At its core, it is almost always a disorder of "executive function" - that set of mental abilities that includes focusing attention, holding information in the mind, and blocking out distractions. These skills are so fundamental that when they collapse, much of the human cognitive edifice collapses. Everything that has to do with concentration, multitasking and planning - that is, almost everything important - becomes absurdly difficult.

THERE IS MEMORIES, BUT AS LIKE BEHIND GLASS

Of course, "brain fog" is not Alzheimer's disease at all, but it looks like it.

“When I try to remember my scientific work, some facts related to research, even my relatives, everything seems far away to me. These are just events, but no longer a part of me. It feels like I am a void and I live in a void,” says Hannah Davis.

Other patients make an interesting comparison - “before, the brain was like a racing car, it started at half a turn and smoothly fit into the sharpest turns. And now we are barely riding on a collapsed jalopy. For many, this loss becomes palpable, like real physical pain.

HE WAS LONG BEFORE COVID

The most amazing thing is that the covid pandemic “gave” brain fog to many people, but the “fog” itself was there before. These symptoms are well known to people living with HIV, epileptics after seizures, patients undergoing brain chemotherapy, and people with rare chronic conditions like fibromyalgia. Another "fog" occurs in myalgic encephalomyelitis, also known as chronic fatigue syndrome, or ME/CFS, a condition that Davis and many others now suffer from.

But - the disease was not recognized, but the sick were laughed at - you are fooling, pretending to be. At best, they said: “Oh, it’s just a little depression, don’t worry.”

"We don't yet have the right tools to measure the severity of brain fog," said David Putrino, head of the Mount Sinai Covid Rehabilitation Clinic. - Physicians often use the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, which was designed to identify extreme mental health problems in older people with dementia and is not suitable for people under 55. With such tests, a young person, even with a strong “brain fog”, can cope. There are more sophisticated tests, but they still compare people to the population average rather than to their previous baseline.

BRAIN FOG AFTER CORONAVIRUS IS EASIER TO HIDE THAN EXPLAIN

Unfortunately, many patients who experience "brain fog" prefer not to talk about it. For example, Julia Moore Vogel, who helps run a major biomedical research program, may have enough managerial responsibilities for her job, but “almost everything else in my life I cut out to make room for that. That is, I even reduced any communication to a minimum - it takes too much strength from me.

But she rarely talks about it, because “in my field, the brain is the currency,” she said. “And I know that my value in the eyes of many people will decrease if they find out that I have cognitive problems.”

The difficulty is that the usual methods of recovery are not suitable for such people. For example, sports are often contraindicated. But the regimen and good sleep, as well as proper, healthy food - yes. For example, Vogel wears a special device that tracks her heart rate, sleep, activity, and stress as a measure of her energy level. If they seem low, she forces herself to rest - both cognitively and physically

At times like these, “you have to admit that you're in a crisis and the best thing you can do is literally do nothing,” she said. When you get stuck in the fog, sometimes the only way out is to stand still. Read also

Acting EDITOR-IN-CHIEF OF THE SITE - KANSKY VICTOR FYODOROVICH.

THE AUTHOR OF THE MODERN VERSION OF THE EDITION IS SUNGORKIN VLADIMIR NIKOLAEVICH.

Messages and comments from site readers are posted without preliminary editing. The editors reserve the right to remove them from the site or edit them if the specified messages and comments are an abuse of freedom mass media or violation of other requirements of the law.

JSC "Publishing House "Komsomolskaya Pravda". TIN: 7714037217 PSRN: 1027739295781 127015, Moscow, Novodmitrovskaya d. 2B, Tel. +7 (495) 777-02-82.

Exclusive rights to materials posted on the website www.kp.ru, in accordance with the legislation of the Russian Federation for the Protection of the Results of Intellectual Activity belong to JSC Publishing House Komsomolskaya Pravda, and do not be used by others in any way form without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Acquisition of copyrights and communication with the editors: [email protected]

Scientists warn of "brain fog" in "protracted COVID" - RBC

adv.rbc.ru

adv.rbc.ru

adv.rbc.ru

Hide banners

What is your location ?

YesSelect other

Categories

Euro exchange rate on November 26

EUR CB: 62.88 (+0.09) Investments, 25 Nov, 16:30

Dollar exchange rate on November 26

USD Central Bank: 60.48 (+0.09) Investments, 25 Nov, 16:30

$21 trillion: how much carbon neutrality costs in China RBC and Sber, 13:13

Yeni Şafak learned about Turkey's plan to start a ground operation in Syria Politics, 13:01

Tunisia - Australia. Match of the second round of the group stage of the World Cup Sports, 13:00

adv.rbc.ru

adv.rbc.ru

What happens at the World Cup in Qatar. Online of the seventh gaming day Sports, 12:54

Belgium will transfer underwater drones and mobile laboratories to Kyiv Politics, 12:54

Former 100m world record holder retired Sports, 12:49

45 layouts and new technologies: what is the city-complex "Amaranth" RBC and Amaranth, 12:32

Black Friday: -50% off all intensives!

Buy now and start training at your convenience

Learn more

Lavrov promised Ukraine liberation from "neo-Nazi rulers" Politics, 12:27

Dick Advocaat decided to resume his coaching career Sport, 12:19

The IAEA announced the effect of a "dirty bomb" when hitting fuel from the ZNPP Politics, 12:06

Know your customers and competitors: how to grow your business and manage risk RBC and SberAnalytica, 12:05

The Ministry of Finance has developed a special procedure for the budgets of new regions Economy, 12:00

How fireworks harm wild and domestic animals Green economy, 12:00

In Russia, for the first time since the beginning of November, more than 6 thousand cases of COVID were detected Society, 11:57

adv. rbc.ru

adv.rbc.ru

adv.rbc.ru

Deposit "Stable"

Your income

0 ₽

Rate

0%

More

VTB Bank (PJSC). Advertising. 0+

"Brain fog", extreme exhaustion, hair loss, and inability to taste or smell, these symptoms may appear for months after recovery. The phenomenon was called “protracted COVID”

Photo: Maxim Shemetov / Reuters

In some cases, people who have recovered from COVID-19 continue to suffer from symptoms of the disease for months after the infection has disappeared from the body and is not determined by diagnostic methods. These conclusions were made by specialists from the National Institutes of Health of Great Britain, reports the Financial Times, citing their study.

Doctors describe these manifestations as "debilitating", and experts called the phenomenon itself "protracted COVID". Such cases raise concerns about the long-term health effects of the pandemic, the newspaper notes.

Patients who recovered from the first wave of coronavirus continued to suffer from diseases of the brain, lungs, heart, intestines, liver, skin and other parts of the body. Among the most severe manifestations are months of "brain fog" and extreme exhaustion. Other effects are milder, such as hair loss and the inability to taste or smell.

These symptoms appear in one physiological system, then subside, but appear in another body system, British researchers have described the manifestations of "protracted COVID".

Using the King's College London's Covid Symptom Study app, which is regularly used by 4 million people, scientists have found that up to 20% of infections lead to complications lasting more than a month.

adv.rbc.ru

Public Health England reported that about 10% of COVID-19 casesin a mild form, when hospitalization was not required, gave consequences in the form of symptoms that lasted more than four weeks.

"This coronavirus appears to behave very differently from other viral infections, such as the flu," said Philip Pearson, a physician.

Earlier, the head of the Russian Ministry of Health Mikhail Murashko said that as a result of the coronavirus infection, not only the lungs, but also the heart suffer. He warned that those who had been ill needed rehabilitation in order to return to their usual way of life.

The chief pathologist of the Irkutsk Clinical Hospital, Lyudmila Grishina, spoke about her observations during the autopsy of the bodies of those who died from COVID. First of all, according to her, the lungs suffer. “There is massive swelling. Microcirculation is disturbed, which leads to hemorrhage into the lumen of the alveoli, ”said Grishina.