Preschool anxiety treatment

Treatment of Anxiety and Depression in the Preschool Period

1. Kashani JH, Holcomb WR, Orvaschel H. Depression and depressive symptoms in preschool children from the general population. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:1138–1143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Kashani JH, Allan WD, Beck NC, Jr, Bledsoe Y, Reid JC. Dysthymic disorder in clinically referred preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1426–1433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Luby J, Heffelfinger A, Mrakotsky C, et al. The clinical picture of depression in preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:340–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Luby J, Si X, Belden AC, Tandon M, Spitznagel E. Preschool depression: Homotypic continuity and course over 24 months. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:897–905. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Scheeringa MS. Developmental considerations for diagnosing PTSD and acute stress disorder in preschool and school-age children. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1237–1239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Warren SL, Umylny P, Aron E, Simmens SJ. Toddler anxiety disorders: a pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:859–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Gaffrey MS, Belden AC, Luby JL. The 2-week duration criterion and severity and course of early childhood depression: implications for nosology. J Affect Disord. 2011;133:537–545. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Scheeringa MS, Peebles CD, Cook CA, Zeanah CH. Toward establishing procedural, criterion, and discriminant validity for PTSD in early childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:52–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

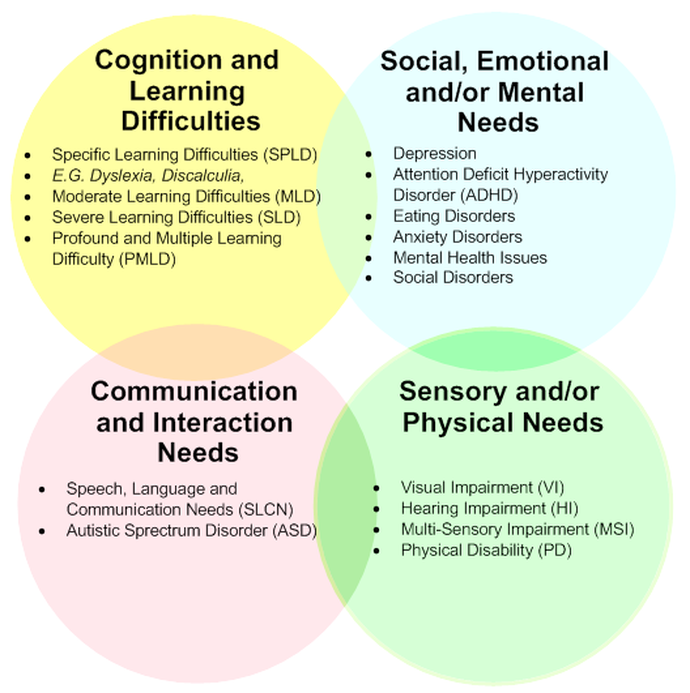

9. Egger H, Angold A. Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: Presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:313–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Bufferd SJ, Dougherty LR, Carlson GA, Rose S, Klein DN. Psychiatric disorders in preschoolers: continuity from ages 3 to 6. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:1157–1164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:1157–1164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Shonkoff JP, Phillips D. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington, D. C: National Academy Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

12. Luby JL. Dispelling the “They’ll Grow Out of It” Myth: Implications for Intervention. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:1127–1129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Call J, Galenson E, Tyson R. Frontiers of Infant Psychiatry. Vol. 1. New York: Basic Books; 1983. [Google Scholar]

14. Zeanah CH., Jr . Handbook of Infant Mental Health. Vol. 1. New York: The Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

15. Luby JL, Morgan K. Characteristics of an infant/preschool psychiatric clinic sample: Implications for clinical assessment and nosology. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1997;18:209–220. [Google Scholar]

16. Hooks MY, Mayes LC, Volkmar FR. Psychiatric disorders among preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27:623–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1988;27:623–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Frankel KA, Boyum LA, Harmon RJ. Diagnoses and presenting symptoms in an infant psychiatry clinic: Comparison of two diagnostic systems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:578–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Fraiberg S. Clinical Studies in Infant Mental Health: The First Year of Life. New York: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

19. DelCarmen-Wiggins R, Carter A, editors. Handbook of infant, toddler, and preschool mental health assessment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

20. Clark R, Tluczek A, Gallagher KC. Assessment of parent-child early relational disturbances. In: DelCarmen-Wiggins R, Carter A, editors. Handbook of infant, toddler, and preschool mental health assessment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 25–60. [Google Scholar]

21. Luby J, Belden AC, Pautsch J, Si X, Spitznagel E. The clinical significance of preschool depression: Impairment in functioning and clinical markers of the disorder. J Affect Disord. 2009;112:111–119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Affect Disord. 2009;112:111–119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Kashani JH, Carlson GA. Major depressive disorder in a preschooler. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1985;24:490–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Kashani JH, Carlson GA. Seriously depressed preschoolers. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:348–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Luby J, Heffelfinger A, Mrakotsky C, Brown K, Hessler M, Spitznagel E. Alterations in stress cortisol reactivity in depressed preschoolers relative to psychiatric and no-disorder comparison groups. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1248–1255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Luking KR, Repovs G, Belden AC, et al. Functional connectivity of the amygdala in early-childhood-onset depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:1027–1041. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Barch DM, Gaffrey MS, Botteron KN, Belden AC, Luby JL. Functional brain activation to emotionally valenced faces in school-aged children with a history of preschool-onset major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:1035–1042. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:1035–1042. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Lee BJ. Multidisciplinary evaluation of preschool children and its demography in a military psychiatric clinic. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1987;26:313–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Spence SH, Rapee R, McDonald C, Ingram M. The structure of anxiety symptoms among preschoolers. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39:1293–1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Eley TC, Bolton D, O’Connor TG, Perrin S, Smith P, Plomin R. A twin study of anxiety-related behaviours in pre-school children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2003;44:945–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Mian ND, Godoy L, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS. Patterns of anxiety symptoms in toddlers and preschool-age children: evidence of early differentiation. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26:102–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Lavigne JV, LeBailly SA, Hopkins J, Gouze KR, Binns HJ. The prevalence of ADHD, ODD, depression, and anxiety in a community sample of 4-year-olds. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2009;38:315–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2009;38:315–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Briggs-Gowan M, Horwitz S, Schwab-Stone M, Leventhal J, Leaf P. Mental health in pediatric settings: distribution of disorders and factors related to service use. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:841–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Luby J, Heffelfinger A, Mrakrotsky C, Hildebrand T. Preschool Feelings Checklist. St. Louis, MO: Washington University School of Medicine; 1999. [Google Scholar]

34. Luby J, Heffelfinger A, Koenig-McNaught AL, Brown K, Spitznagel E. The preschool feelings checklist: A brief and sensitive screening measure for depression in young children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:708–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Edwards SL, Rapee RM, Kennedy SJ, Spence SH. The assessment of anxiety symptoms in preschool-aged children: the revised Preschool Anxiety Scale. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2010;39:400–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:807–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:807–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2753–2766. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Masek B, Henin A, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for 4- to 7-year-old children with anxiety disorders: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:498–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N. Biological bases of childhood shyness. Science. 1988;240:167–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Kagan J, Snidman N, Zentner M, Peterson E. Infant temperament and anxious symptoms in school age children. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11:209–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Rapee RM, Kennedy SJ, Ingram M, Edwards SL, Sweeney L. Altering the trajectory of anxiety in at-risk young children. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1518–1525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, et al. A controlled study of behavioral inhibition in children of parents with panic disorder and depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:2002–2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J. Rationale and principles for early intervention with young children at risk for anxiety disorders. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2002;5:161–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Rapee RM, Kennedy S, Ingram M, Edwards S, Sweeney L. Prevention and early intervention of anxiety disorders in inhibited preschool children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:488–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Grave J, Blissett J. Is cognitive behavior therapy developmentally appropriate for young children? A critical review of the evidence. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:399–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:399–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Houde O. Inhibition and cognitive development: object, number, categorization, and reasoning. Cognitive Dev. 2000;15:63–73. [Google Scholar]

47. Scheeringa MS, Amaya-Jackson L, Cohen J. Preschool PTSD Treatment manual (PPT) 2002. [Google Scholar]

48. Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. A treatment outcome study for sexually abused preschool children: initial findings. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:42–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Deblinger E, Stauffer LB, Steer RA. Comparative efficacies of supportive and cognitive behavioral group therapies for young children who have been sexually abused and their nonoffending mothers. Child Maltreat. 2001;6:332–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Scheeringa MS, Weems CF, Cohen JA, Amaya-Jackson L, Guthrie D. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in three-through six year-old children: a randomized clinical trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52:853–860. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52:853–860. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Kendall PC, Hedtke KA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious children: therapist manual. 3. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

52. Eyberg S, Funderburk B. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy Protocol. PCIT International, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

53. Eyberg SM, Funderburk BW, Hembree-Kigin TL, McNeil CB, Querido JG, Hood KK. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy with behavior problem children: One and two year maintenance of treatment effects in the family. Child Fam Behav Ther. 2001;23:1–20. [Google Scholar]

54. Pincus DB, Santucci LC, Ehrenreich JT, Eyberg SM. The implementation of modified Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for youth with Separation Anxiety Disorder. Cogn Behav Pract. 2008;15:118–125. [Google Scholar]

55. Oerbeck B, Johansen J, Lundahl K, Kristensen H. Selective mutism: A home-and kindergarten-based intervention for children 3–5 Years: A pilot study. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;17:370–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;17:370–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Cohan SL, Chavira DA, Stein MB. Practitioner review: Psychosocial interventions for children with selective mutism: a critical evaluation of the literature from 1990–2005. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:1085–1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Freeman JB, Garcia AM, Coyne L, et al. Early childhood OCD: preliminary findings from a family-based cognitive-behavioral approach. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:593–602. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Ginsburg GS, Burstein M, Becker KD, Drake KL. Treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder in young children: An intervention model and case series. Child Fam Behav Ther. 2011;33:97–122. [Google Scholar]

59. Ginsburg GS, Kingery JN, Drake KL, Grados MA. Predictors of treatment response in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:868–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Freeman JB, Choate-Summers ML, Moore PS, et al. Cognitive behavioral treatment for young children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:337–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Freeman JB, Choate-Summers ML, Moore PS, et al. Cognitive behavioral treatment for young children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:337–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Field T. Infants of depressed mothers. In: Johnson SL, Hayes AM, Field TM, Schneiderman N, McCabe PM, editors. Stress, coping, and depression. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2000. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

62. Tronick E, Reck C. Infants of depressed mothers. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2009;17:147–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Toth SL, Rogosch FA, Manly JT, Cicchetti D. The efficacy of toddler-parent psychotherapy to reorganize attachment in the young offspring of mothers with major depressive disorder: a randomized preventive trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:1006–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. van Doesum KT, Riksen-Walraven JM, Hosman CM, Hoefnagels C. A randomized controlled trial of a home-visiting intervention aimed at preventing relationship problems in depressed mothers and their infants. Child Dev. 2008;79:547–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Child Dev. 2008;79:547–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Weisz J, McCarty C, Valeri S. Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:132–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Hood KK, Eyberg SM. Outcomes of parent-child interaction therapy: mothers’ reports of maintenance three to six years after treatment. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32:419–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Luby J, Belden AC, Sullivan J, Hayen R, McCadney A, Spitznagel E. Shame and guilt in preschool depression: evidence for elevations in self-conscious emotions in depression as early as age 3. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50:1156–1166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Luby J, Belden AC. Mood disorders and an emotional reactivity model of depression. In: Luby J, editor. Handbook of Preschool Mental Health: Development, Disorders, and Treatment. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 209–230. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

69. Luby J, Belden AC, Sullivan J, Spitznagel E. Preschoolers’ contribution to their diagnosis of depression and anxiety: Uses and limitations of young child self-report of symptoms. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2007;38:321–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Luby J, Lenze S, Tillman R. A novel early intervention for preschool depression: findings from a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53:313–322. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Wickramaratne P, Gameroff MJ, Pilowsky DJ, et al. Children of depressed mothers 1 year after remission of maternal depression: findings from the STAR*D-Child study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:593–602. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Coiro MJ, Riley A, Broitman M, Miranda J. Effects on children of treating their mothers’ depression: results of a 12-month follow-up. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:357–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Gunlicks ML, Weissman MM. Change in child psychopathology with improvement in parental depression: A systematic review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:379–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Change in child psychopathology with improvement in parental depression: A systematic review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:379–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Murray L, Cooper PJ, Wilson A, Romaniuk H. Controlled trial of the short- and long-term effect of psychological treatment of post-partum depression: 2. Impact on the mother-child relationship and child outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:420–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Forman DR, O’Hara MW, Stuart S, Gorman LL, Larsen KE, Coy KC. Effective treatment for postpartum depression is not sufficient to improve the developing mother-child relationship. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19:585–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Olfson M, Crystal S, Huang C, Gerhard T. Trends in antipsychotic drug use by very young, privately insured children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:13–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, Gardner JF, Boles M, Lynch F. Trends in the prescribing of psychotropic medications to preschoolers. JAMA. 2000;283:1025–1030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

JAMA. 2000;283:1025–1030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Zuckerman ML, Vaughan BL, Whitney J, et al. Tolerability of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in thirty-nine children under age seven: a retrospective chart review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17:165–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Coskun M, Zoroglu S. Efficacy and safety of fluoxetine in preschool children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19:297–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Vitiello B, Jensen PS. Developmental perspectives in pediatric psychopharmacology. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1995;31:75–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Wagner KD, Robb AS, Findling RL, Jin J, Gutierrez MM, Heydorn WE. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of citalopram for the treatment of major depression in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1079–1083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Evidence Base Update on the Treatment of Early Childhood Anxiety and Related Problems

Review

. 2019 Jan-Feb;48(1):1-15.

doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1534208. Epub 2019 Jan 14.

Jonathan S Comer 1 , Natalie Hong 1 , Bridget Poznanski 1 , Karina Silva 1 , Maria Wilson 1

Affiliations

Affiliation

- 1 a Mental Health Interventions and Technology (MINT) Program, Center for Children and Families , Florida International University.

- PMID: 30640522

- DOI: 10.

1080/15374416.2018.1534208

1080/15374416.2018.1534208

Review

Jonathan S Comer et al. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2019 Jan-Feb.

. 2019 Jan-Feb;48(1):1-15.

doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1534208. Epub 2019 Jan 14.

Authors

Jonathan S Comer 1 , Natalie Hong 1 , Bridget Poznanski 1 , Karina Silva 1 , Maria Wilson 1

Affiliation

- 1 a Mental Health Interventions and Technology (MINT) Program, Center for Children and Families , Florida International University.

- PMID: 30640522

- DOI: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1534208

Abstract

The controlled evaluation of treatments for early childhood anxiety and related problems has been a relatively recent area of investigation, and accordingly, trials examining early childhood anxiety treatment have not been well represented in existing systematic reviews of youth anxiety treatments. This Evidence Base Update provides the first systematic review of evidence supporting interventions specifically for the treatment of early childhood anxiety and related problems. Thirty articles testing 38 treatments in samples with mean age < 7.9 years (N = 2,228 children) met inclusion criteria. We applied Southam-Gerow and Prinstein's (2014) review criteria, which classifies families of treatments according to one of five levels of empirical support-Well-Established, Probably Efficacious, Possibly Efficacious, Experimental, and of Questionable Efficacy. We found family-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to be a Well-Established treatment, and Group Parent CBT and Group Parent CBT + Group Child CBT to both be Probably Efficacious treatments. In contrast, play therapy and attachment-based therapy are still only Experimental treatments for early childhood anxiety, relaxation training has Questionable Efficacy, and there is no evidence to date to speak to the efficacy of individual child CBT and/or medication in younger anxious children. All 3 currently supported interventions for early childhood anxiety entail exposure-based CBT with significant parental involvement. This conclusion meaningfully differs from conclusions for treating anxiety in older childhood that highlight the well-established efficacy of individual child CBT and/or medication and that question whether parental involvement in treatment enhances outcomes.

We found family-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to be a Well-Established treatment, and Group Parent CBT and Group Parent CBT + Group Child CBT to both be Probably Efficacious treatments. In contrast, play therapy and attachment-based therapy are still only Experimental treatments for early childhood anxiety, relaxation training has Questionable Efficacy, and there is no evidence to date to speak to the efficacy of individual child CBT and/or medication in younger anxious children. All 3 currently supported interventions for early childhood anxiety entail exposure-based CBT with significant parental involvement. This conclusion meaningfully differs from conclusions for treating anxiety in older childhood that highlight the well-established efficacy of individual child CBT and/or medication and that question whether parental involvement in treatment enhances outcomes.

Similar articles

-

Evidence Base Update for Psychosocial Treatments for Children and Adolescents Exposed to Traumatic Events.

Dorsey S, McLaughlin KA, Kerns SEU, Harrison JP, Lambert HK, Briggs EC, Revillion Cox J, Amaya-Jackson L. Dorsey S, et al. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017 May-Jun;46(3):303-330. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1220309. Epub 2016 Oct 19. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017. PMID: 27759442 Free PMC article. Review.

-

Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for child and adolescent anxiety disorders across different CBT modalities and comparisons: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Sigurvinsdóttir AL, Jensínudóttir KB, Baldvinsdóttir KD, Smárason O, Skarphedinsson G. Sigurvinsdóttir AL, et al. Nord J Psychiatry. 2020 Apr;74(3):168-180. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2019.1686653. Epub 2019 Nov 18. Nord J Psychiatry. 2020. PMID: 31738631

-

Evidence Base Update: 50 Years of Research on Treatment for Child and Adolescent Anxiety.

Higa-McMillan CK, Francis SE, Rith-Najarian L, Chorpita BF. Higa-McMillan CK, et al. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2016;45(2):91-113. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1046177. Epub 2015 Jun 18. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2016. PMID: 26087438 Review.

-

Behavioural and cognitive-behavioural group-based parenting programmes for early-onset conduct problems in children aged 3 to 12 years.

Furlong M, McGilloway S, Bywater T, Hutchings J, Smith SM, Donnelly M. Furlong M, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Feb 15;(2):CD008225. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008225.pub2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012. PMID: 22336837 Review.

-

Clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness of brief guided parent-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy and solution-focused brief therapy for treatment of childhood anxiety disorders: a randomised controlled trial.

Creswell C, Violato M, Fairbanks H, White E, Parkinson M, Abitabile G, Leidi A, Cooper PJ. Creswell C, et al. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017 Jul;4(7):529-539. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30149-9. Epub 2017 May 17. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017. PMID: 28527657 Free PMC article. Clinical Trial.

See all similar articles

Cited by

-

Harnessing Home-School Partnerships and School Consultation to Support Youth With Anxiety.

Conroy K, Hong N, Poznanski B, Hart KC, Ginsburg GS, Fabiano GA, Comer JS. Conroy K, et al. Cogn Behav Pract. 2022 May;29(2):381-399. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2021.02.007. Epub 2021 Apr 21. Cogn Behav Pract. 2022. PMID: 35812004

-

A Qualitative Inquiry of Parents' Observations of Their Children's Mental Health Needs During the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Barth AM, Meinert AC, Zopatti KL, Mathai D, Leong AW, Dickinson EM, Goodman WK, Shah AA, Schneider SC, Storch EA. Barth AM, et al. Child Health Care. 2022;51(2):213-234. doi: 10.1080/02739615.2021.2003196. Epub 2021 Dec 3. Child Health Care. 2022. PMID: 35530015

-

Better Together: A Review and Recommendations to Optimize Research on Family Involvement in CBT for Anxiety and Related Disorders.

Reuman L, Thompson-Hollands J, Abramowitz JS. Reuman L, et al. Behav Ther. 2021 May;52(3):594-606. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2020.07.008. Epub 2020 Aug 6. Behav Ther. 2021. PMID: 33990236 Free PMC article. Review.

-

Innovations in the Delivery of Exposure and Response Prevention for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder.

Patel SR, Comer J, Simpson HB.

Patel SR, et al. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2021;49:301-329. doi: 10.1007/7854_2020_202. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2021. PMID: 33590457

Patel SR, et al. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2021;49:301-329. doi: 10.1007/7854_2020_202. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2021. PMID: 33590457 -

Reducing the Nighttime Fears of Young Children Through a Brief Parent-Delivered Treatment-Effectiveness of the Hungarian Version of Uncle Lightfoot.

Kopcsó K, Láng A, Coffman MF. Kopcsó K, et al. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2022 Apr;53(2):256-267. doi: 10.1007/s10578-020-01103-4. Epub 2021 Jan 23. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2022. PMID: 33484397 Free PMC article.

See all "Cited by" articles

Publication types

MeSH terms

Children's anxiety.

How to help an anxious child? | "Four-leaf clover"

How to help an anxious child? | "Four-leaf clover" Children's anxiety

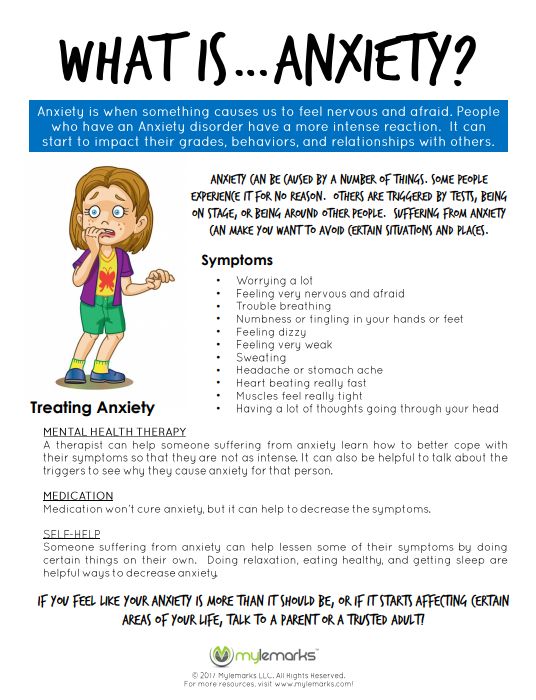

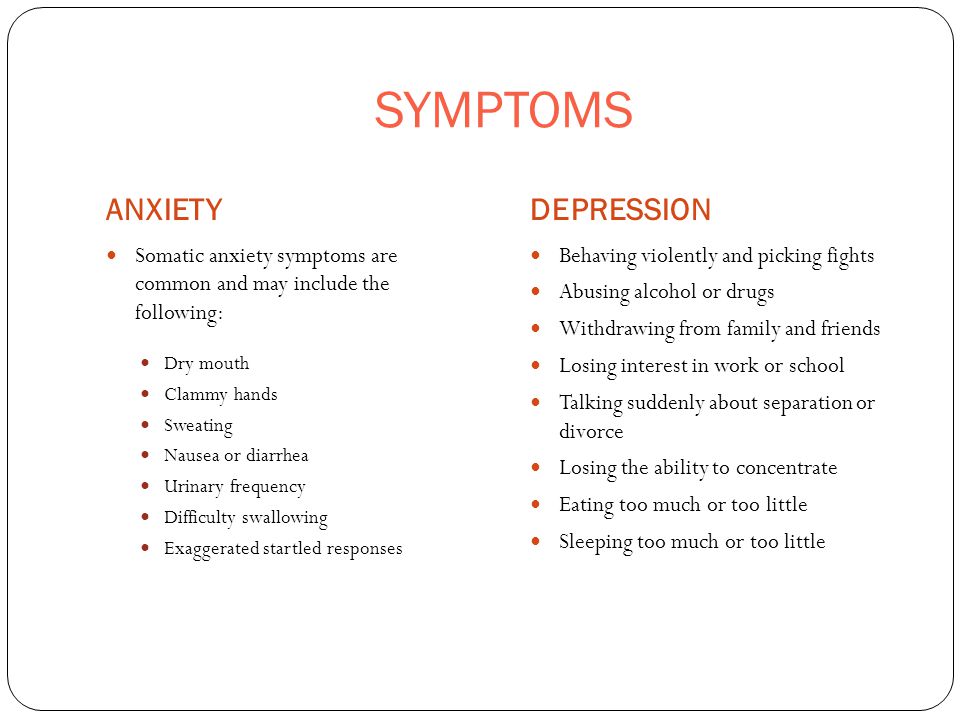

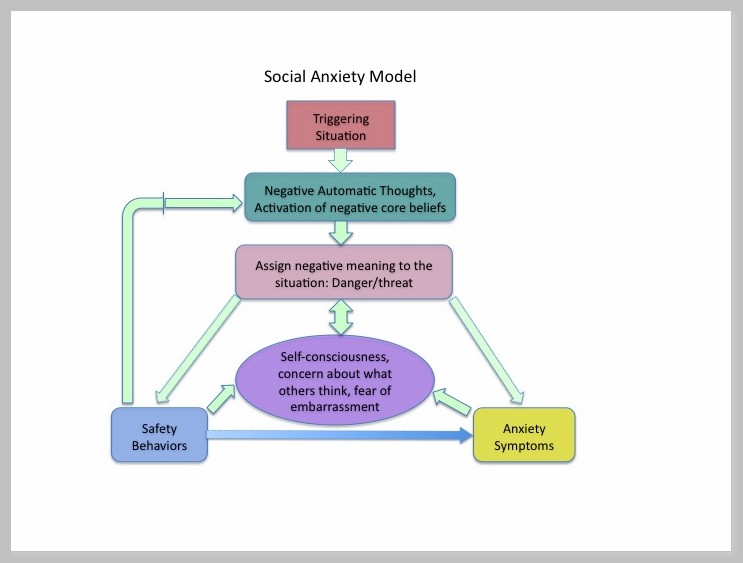

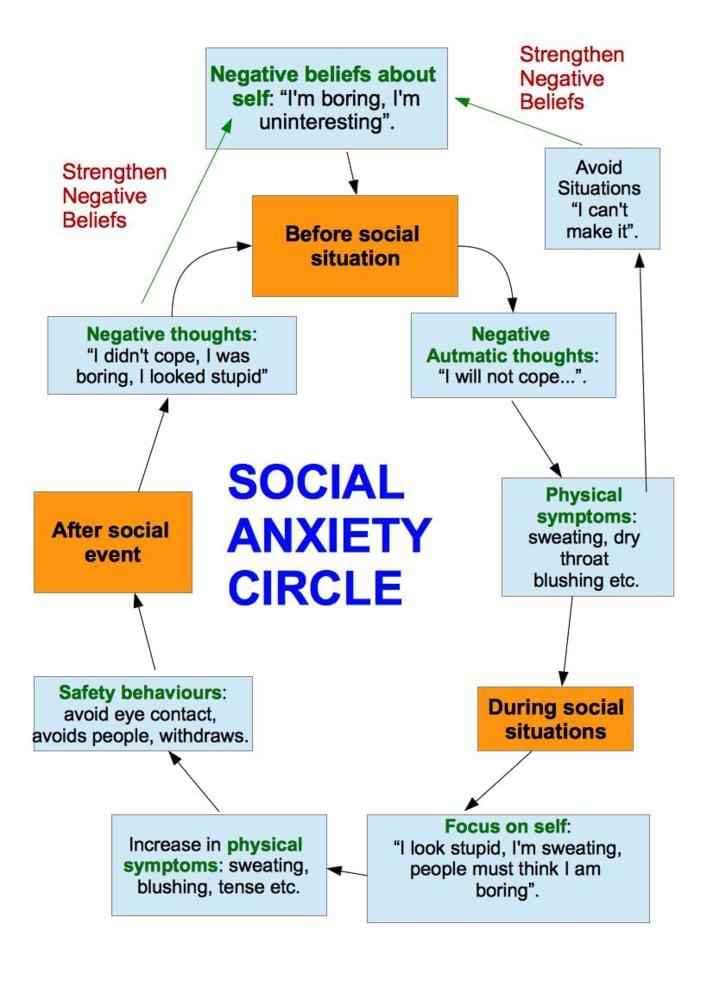

Anxiety is commonly referred to as an increased tendency to experience apprehension and worry. In some situations, anxiety is justified and even useful: it mobilizes a person, allows you to avoid danger or solve a problem. This is the so-called situational anxiety. But sometimes anxiety accompanies a person in all life circumstances, even objectively favorable ones. That is, it becomes a stable personality trait. Such a person experiences constant unaccountable fear, an indefinite sense of threat. Any event is perceived as unfavorable and dangerous.

An anxious child is constantly depressed, on guard, it is difficult for him to establish contact with others, the world is perceived as frightening and hostile.

An anxious child is constantly depressed, on guard, it is difficult for him to establish contact with others, the world is perceived as frightening and hostile. Low self-esteem and a gloomy look at the future are constantly fixed.

Low self-esteem and a gloomy look at the future are constantly fixed.

Signs of anxiety:

- The child cannot work for a long time without getting tired

- He has difficulty concentrating on something

- Any occupation causes unnecessary anxiety

- During the performance of the task is very tense, constrained

- Embarrassed more than others

- Often talks about tense situations

- Blushing in unfamiliar surroundings

- Complains about having nightmares

- His hands are usually cold and damp

- He often has stool disorder

- Sweats profusely when excited

- Does not have a good appetite

- Sleeps restlessly, falls asleep with difficulty

- Shy, many things cause him fear

- Usually restless, easily upset

- Often unable to hold back tears

- Does not tolerate waiting well

- Doesn't like to take on new business

- Unsure of yourself and your abilities

- Afraid to face difficulties

Childhood anxiety at different ages

Preschool anxiety

It is often difficult for parents to understand why their child may be worried. Well, what problems can there be at his age: dressed, well-fed, the yard is full of friends, a lot of toys, loving relatives ?!

Well, what problems can there be at his age: dressed, well-fed, the yard is full of friends, a lot of toys, loving relatives ?!

However, the presence of childhood anxiety problems signals that in the life of a small person, not everything is as smooth as it seems to adults. This condition should never be ignored. In addition, it doesn’t matter if you have a son or a daughter, at this age anxiety does not depend on the child’s gender.

Anxiety is inherent in a person, regardless of age. In children from 1 to 3 years of age, the most common fears are caused by sharp loud sounds, sudden pain, for example, during vaccinations, and as a result, a negative reaction to doctors. In the age range from 3 to 5 years, anxiety in preschoolers often manifests itself in the form of fears such as fear of the dark, closed space, and loneliness. At the age of 5 to 7 years, fear of death is often added. If you notice anxiety in your child, in no case should you let this problem go by itself.

In the age range from 3 to 5 years, anxiety in preschoolers often manifests itself in the form of such fears as fear of the dark, closed space, loneliness. At the age of 5 to 7 years, fear of death is often added.

School anxiety

The age from 7 to 11 years can become very difficult. At this time, the child's life changes, he becomes an adult, he is entrusted with the mission of studying well, behaving correctly, being better, diligent, smarter than his peers.

Usually, anxiety manifests itself 1.5 months after the start of the school year, it is in connection with this that schoolchildren need rest - holidays from 1 to 1.5 weeks.

Usually, anxiety manifests itself 1.5 months after the start of the school year, it is in connection with this that schoolchildren need rest - holidays from 1 to 1.5 weeks.

Sometimes anxiety is related to more serious problems. So, with the help of a professional psychologist at the Four-Leaf Clover Clinic of Restorative Psychology, a child can be diagnosed with a mental disorder, neurosis at an early stage.

So, with the help of a professional psychologist at the Four-Leaf Clover Clinic of Restorative Psychology, a child can be diagnosed with a mental disorder, neurosis at an early stage.

Where does increased anxiety come from?

- If there is a constant anxious and suspicious atmosphere in the house. If the parents themselves are constantly afraid of something and worry about something. This condition is very contagious, the child adopts from adults an unhealthy form of reaction to everything, even to ordinary life events.

- If the child lacks information (or uses incorrect information). Try to keep track of what he reads, what programs he watches, what emotions he experiences. It is sometimes difficult for adults to understand how children interpret this or that event.

- Anxious children can grow up not only with anxious parents. The authoritarian style of parenting in the family also does not contribute to the inner peace of the child.

Parents who do not doubt and do not worry know exactly what and how to achieve in life. And most importantly - what they want to achieve from their child. Such a child must constantly live up to the high expectations of adults. He is in a situation of constant and intense expectation: he managed or failed to please his parents. It is especially difficult for a child if the demands and reactions of adults are unpredictable and inconsistent.

A child's internal conflict can be caused by:

- Contradictory demands made by parents or parents and the school (kindergarten). For example, parents do not let their child go to school because they feel unwell, and the teacher puts a “deuce” in a journal and scolds him for skipping a lesson in the presence of other children.

- Inadequate requirements, most often overstated. For example, parents repeatedly repeat to the child that he must certainly be an excellent student, they cannot come to terms with the fact that the child receives at school not only "five" and is not the best student in the class.

- Negative demands that humiliate the child, put him in a dependent position. For example, a caregiver or teacher says to a child: “If you tell me who behaved badly in my absence, I won’t tell my mother that you got into a fight.”

Experts believe that in preschool and younger preschool age boys are more anxious, and after 12 years - girls. At the same time, girls are more worried about relationships with other people, and boys are more worried about violence and punishment.

Having committed some “unseemly” act, the girls worry that their mother or teacher will think badly of them, and their girlfriends will refuse to be friends with them. In the same situation, boys are likely to be afraid that they will be punished by adults or beaten by their peers.

How to help an anxious child?

- Raise the child's self-esteem

To achieve success in this matter, it is necessary that an adult himself see the dignity of the child, treat him with respect (and not just with love) and be able to notice all his successes, even the smallest ones.

- Teaching a child to manage their behavior

It is necessary to teach the ability to manage oneself in situations that cause the greatest anxiety in the child

- Teach the child to relax

It is important for all children to be able to relax, but for anxious children it is simply a necessity, because the state of anxiety is accompanied by a clamping of different muscle groups.

It is very useful for such a child to attend group psycho-corrective classes - after consultation with a psychologist. The topic of childhood anxiety is well developed in psychology, and usually the effect of such activities is palpable.

Prevention of anxiety. Recommendations to parents.

- Communicating with your child, do not undermine the authority of other significant people.

For example, you can’t say to a child: “Your teachers understand a lot, better listen to your grandmother!”.

Be consistent in your actions, do not forbid the child for no reason what was allowed before.

- Consider children's abilities, do not demand from them what they cannot do.

If a child is given some kind of educational Subject with difficulty, it is better to once again help him and provide support, and when even the slightest success is achieved, do not forget to praise him.

- Trust your child, be honest with him and accept him for who he is.

If for some objective reasons it is difficult for a child to study, choose a circle for him to his liking so that classes in it bring joy to the child and he does not feel disadvantaged.

If parents are not satisfied with the behavior and success of their child, this is not a reason to deny him love and support. Let your child live in an atmosphere of warmth and trust, and then all his many talents will manifest.

If you have any questions on this topic, write or call us +7 (3822) 33–44–77.

Yours truly, Four Leaf Clover.

We wish you happiness and prosperity!

We recommend you specialists: Kupriyanova Irina Evgenievna, Zaichenko Tatyana Vladimirovna, Serykh Nadezhda Sergeevna, Glushko Tatyana Valerievna

← Previous | Next →

Children's fears: symptoms, causes, treatment

Children's clinic JSC "Medicina"

(clinic of Academician Roitberg)

Sign up for doctor

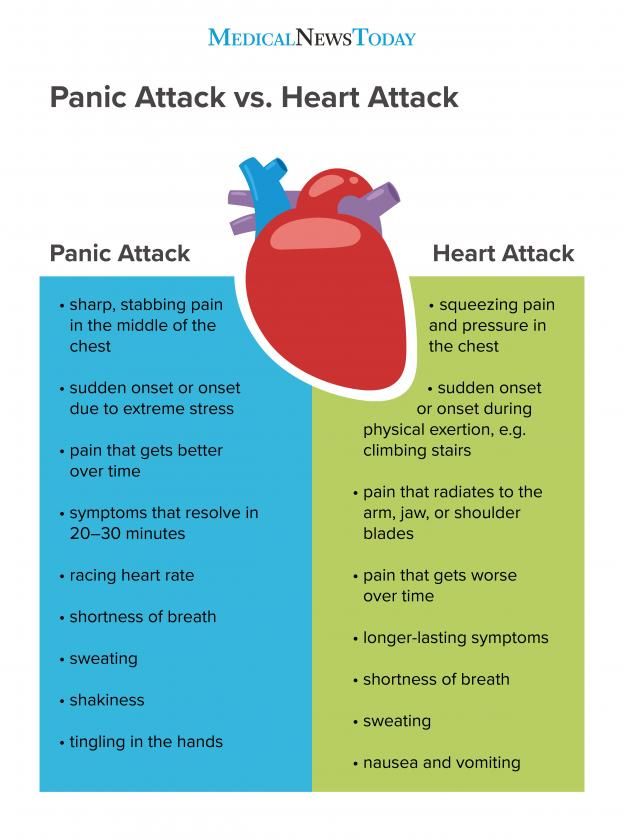

Children's fears are called specific age-related experiences, anxieties and anxieties. Anxiety and fears in children arise as a response mechanism to a real or imaginary threat. The main manifestations are a change in emotional behavior and physiological disorders: rapid heart rate, rapid breathing, muscle tension.

The appearance of fear in response to a real or imagined threat is a self-preservation instinct. However, children's fears are distinguished by the absence of a real threat, their appearance is based on the transformation of external information with the help of fantasy. Normally, fear is considered to be self-limiting and superficial.

According to statistics, no more than 1.5% of children of preschool and primary school age are endowed with pathological fears, while a greater tendency is observed in girls. Factors predisposing to the appearance of children's fears are:

- parents over 35;

- raising an only child;

- restriction of contacts with peers.

In children exposed to fear and anxiety, behavioral disorders are observed:

- avoidance of potentially dangerous situations or objects/objects;

- fear of being alone;

- excessive attachment to adults.

Psychologist, psychotherapist, psychiatrist deals with the treatment of children's fears. The main place is given to parental counseling and psychotherapy with creativity. Diagnosis is made by means of a conversation and a survey.

The main place is given to parental counseling and psychotherapy with creativity. Diagnosis is made by means of a conversation and a survey.

Causes of children's fears

The basis of the fear of certain situations and objects are the characteristics of the psyche of a particular child:

- impressionability;

- credulity;

- wild fantasy;

- increased level of anxiety.

The causes of fears in children lie in the external environment, while the strongest influence is exerted by such a factor as upbringing, and relations with parents become a source of neuroses in the child.

The causes of children's fears are divided into the following groups:

- negative experiences are situations experienced by the child that caused him emotional trauma, for example, a dog attack. Correction of fears in children of this kind is practically impossible; over time, they turn into phobias;

- bullying is a projected situation used by parents or caregivers to correct a child's behavior;

- overly anxious parents generate fears and anxiety in the child;

- The behavior of parents, showing their superiority and strength, gives rise in the child to timidity and a feeling of constant expectation of the bad;

- films and computer games showing scenes of violence;

- mental disorders, eg neurosis or neuropathy;

- intra-family relations, for example, conflicts between parents, constant quarrels and scandals, divorce of parents, manipulation of a child in order to influence a spouse, and others.

Pathogenesis

Explanation of the manifestations of fears in children is associated with age-related changes in the psyche. The main role is played by the fantasy and imagination of the child, under their influence, the transformation of external information into new images takes place. The manifestation of fantasy begins at the age of 2-3 years, reaching a peak at preschool or primary school age. Children's fears are more intense, varied and unusual than any other. The child is not able to assess the situation critically and objectively evaluate their emotions, so fears are so easily born and strengthened in the child's mind.

The content side of fear characterizes a significant area of a child's life for each particular age period, for example, infancy - fear of separation from mother, preschoolers - fear of the dark, animals or fictional characters, schoolchildren - social fears.

Classification

Perhaps the most widespread is the division of fears in children into:

- biological - based on the instinct of self-preservation;

- social - based on interpersonal contacts.

Children's fears are classified according to the object of manifestation, causes, duration of manifestation and features, as well as intensity.

The most common classification distinguishes the following types:

- overvalued. Appear as a result of fantasy work, are considered the most common;

- obsessive. Based on a specific situation in life and generate panic, for example, fear of dogs or heights;

- delusional. Cannot be explained in terms of logic.

Symptoms of fears in children

At different ages, the child manifests fears and anxiety in different ways. Symptoms characteristic of a newborn are anxiety, throwing back the handles, shuddering, general tension. Fears in children under the age of six months are usually caused by a loud sound or bright light, the rapid approach of something large and unfamiliar, or the loss of support. From 6-7 months to three years, there is a fear of loneliness from the long absence of the mother. From 8 months to a year and a half - fear of strangers.

From 8 months to a year and a half - fear of strangers.

From the age of 2, the child may be afraid of certain objects, objects or situations. After 3 years, children begin to be afraid of punishment or lack of attention from their parents, due to the onset of the age of a conscious flow of interpersonal contacts.

Preschool age is characterized by such fears as darkness, condemnation of others, fear of fairy-tale or fictional characters, dangerous objects and objects. At primary school age, interpersonal fears are manifested - public speaking, getting a bad mark, condemnation, ridicule, rejection.

At the age of 6, fears of accidents, catastrophes of various kinds, diseases, fires and even death may begin to appear. Under the influence of fear, the child often loses his appetite, sleep is disturbed, various pains appear, for example, muscle, head, heart, joint pains.

Complications

The most complex and dangerous complication of childhood fear is its transition to a state of phobia. They are expressed in intense reactions of the body in the form of anxiety and panic. They are distinguished by persistent irrational behavior in response to situations or objects that do not carry a real threat. Phobias cannot be corrected, unlike fears.

They are expressed in intense reactions of the body in the form of anxiety and panic. They are distinguished by persistent irrational behavior in response to situations or objects that do not carry a real threat. Phobias cannot be corrected, unlike fears.

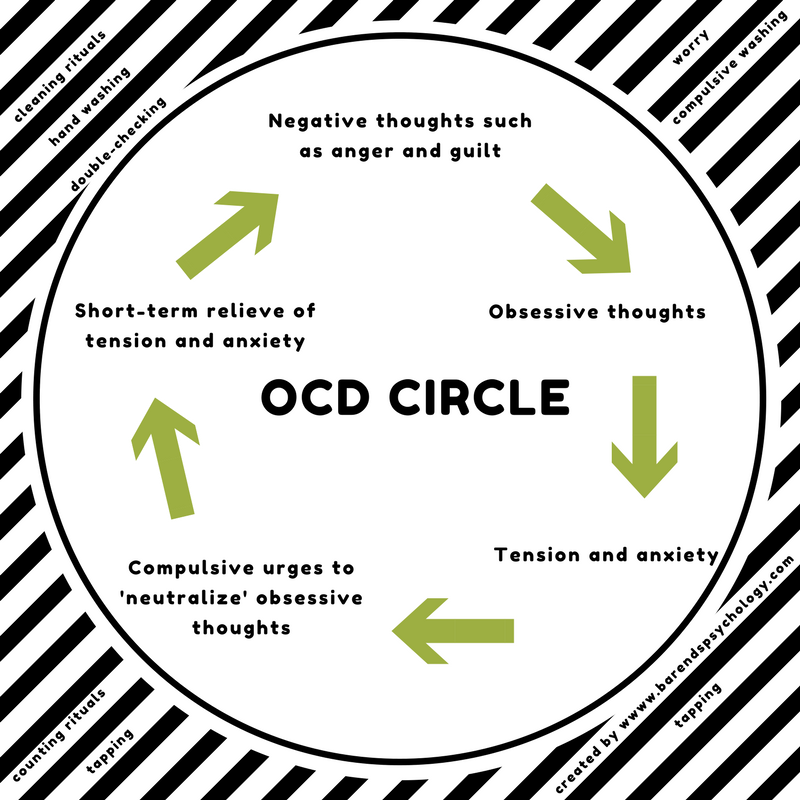

Children's fears can turn into a form of obsessive-compulsive disorder - an obsessive repetition of actions and thoughts. Under the influence of childhood fears in adolescence, traits of suspiciousness, uncertainty and anxiety appear in the character. Thus, the lack of real help and attention from parents, teachers and psychologists in children forms restrictions in behavior in the form of avoiding certain situations, as well as difficulties in social adaptation.

Diagnostics of children's fears

Diagnosing fears in children has the character of a clinical conversation. The child, as a rule, after meeting and establishing contact, does not hide his anxieties, openly talking about situations that cause anxiety.

The diagnostic process of the intensity of fear and anxiety is based on psychodiagnostic methods: personal conversation;

Contacting specialists

The presence of fears in a child is a reason to visit doctors - a psychologist, psychiatrist, psychotherapist. JSC "Medicine" (clinic of academician Roitberg) is receiving highly qualified specialists in this field. Here, children's health is treated as an important mission, so the appointments are conducted by doctors of the highest category with vast experience. They know almost everything about children's health and the specifics of diseases in children. Doctors of the clinic are on the protection of children's health 365 days a year. We are located in the very center of Moscow.

They know almost everything about children's health and the specifics of diseases in children. Doctors of the clinic are on the protection of children's health 365 days a year. We are located in the very center of Moscow.

Treating children's fears

Helping young patients deal with their fears is based on creating a supportive home environment in order to maintain a sense of security and peace. Psychotherapy is used as an additional treatment for fears in children. It is aimed at understanding and transforming emotions of the negative spectrum: fear, anxiety, anxiety.

Complex therapy has the best effect, including:

- family counseling. It aims to identify the causes that contribute to the emergence and maintenance of fear in the child. Here there is a discussion of the methods of education and leisure of children, as well as the features of relations within the family. The specialist should give parents advice on how to communicate with the child and how to correct parental behavior.

This stage is designed to establish comfortable home conditions for correcting fears in children;

This stage is designed to establish comfortable home conditions for correcting fears in children; - psychotherapy in this case is exclusively individual. Due to the conversation in a confidential atmosphere, initially there is a discussion of fears. Confidential dialogue relieves emotional tension. Then comes the period of processing fears. Here, the method of fairy tale therapy is appropriate, with the help of which a fairy tale is composed about fear, where it is defeated, or its visual dressing with the help of modeling / drawing, as a result, fear must be ritually destroyed or remade;

- drug therapy becomes necessary with advanced forms and the presence of complications. The beginning of taking sedatives coincides with the beginning of complex treatment, while the methods of administration and doses are determined by the attending physician individually.

Thus, the timely appeal to specialists for the treatment of children's fears contributes most of the success in the fight against fear in a child. However, in order to identify it, parents should be as attentive as possible to their child.

However, in order to identify it, parents should be as attentive as possible to their child.

Prevention of children's fears

Prevention of fears in children is half the success in the fight against their appearance.

In order to prevent the appearance of fears in their own child, parents must adhere to the following rules:

- establishing and maintaining a trusting relationship with the child;

- refusal of the line of education in the form of dominance of the parent;

- refusal to use physical force;

- refusing to display one's own anxieties and fears;

- proper organization of a child's leisure time.

Proper leisure of a child should meet the following principles:

- maximum outdoor games, creative activities and communication in a team;

- refusal to watch TV and play computer games;

- minimizing the time the child is alone.

Such simple measures can permanently save your child from the appearance of anxieties and fears, unnecessary fears and fears.