Lamotrigine sex drive

Lamotrigine-induced sexual dysfunction and non-adherence: case analysis with literature review

1. Boon P, Engelborghs S, Hauman H, Jansen A, Lagae L, Legros B, et al. Recommendations for the treatment of epilepsy in adult patients in general practice in Belgium: an update. Acta Neurol Belg 2012; 112: 119–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Ketter TA, Miller S, Dell’Osso B, Calabrese JR, Frye MA, Citrome L. Balancing benefits and harms of treatments for acute bipolar depression. J Affect Disord 2014; 169 (suppl 1): S24–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Buelow JM, Smith MC. Medication management by the person with epilepsy: perception versus reality. Epilepsy Behav 2004; 5: 401–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Chapman SC, Horne R, Chater A, Hukins D, Smithson WH. Patients’ perspectives on antiepileptic medication: relationships between beliefs about medicines and adherence among patients with epilepsy in UK primary care.

Epilepsy Behav 2014; 31: 312–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Sajatovic M, Valenstein M, Blow F, Ganoczy D, Ignacio R. Treatment adherence with lithium and anticonvulsant medications among patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv 2007; 58: 855–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Ettinger AB, Manjunath R, Candrilli SD, Davis KL. Prevalence and cost of nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs in elderly patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2009; 14: 324–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Olesen J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Wittchen HU, Jönsson B, CDBE2010 Study Group et al. The economic cost of brain disorders in Europe. Eur J Neurol 2012; 19: 155–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ, Degenhardt L, Feigin V, Vos T. The global burden of mental, neurological and substance use disorders: an analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0116820. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Kessler RC, Akiskal HS, Ames M, Birnbaum H, Greenberg P, Hirschfeld RM, et al. Prevalence and effects of mood disorders on work performance in a nationally representative sample of U.S. workers. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 1561–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kessler RC, Akiskal HS, Ames M, Birnbaum H, Greenberg P, Hirschfeld RM, et al. Prevalence and effects of mood disorders on work performance in a nationally representative sample of U.S. workers. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 1561–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Getnet A, Woldeyohannes SM, Bekana L, Mekonen T, Fekadu W, Menberu M, et al. Antiepileptic drug nonadherence and its predictors among people with epilepsy. Behav Neurol 2016; 2016: 3189108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Nakhutina L, Gonzalez JS, Margolis SA, Spada A, Grant A. Adherence to antiepileptic drugs and beliefs about medication among predominantly ethnic minority patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2011; 22: 584–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Baldessarini RJ, Perry R, Pike J. Factors associated with treatment nonadherence among US bipolar disorder patients. Hum Psychopharmacol 2008; 23: 95–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Leclerc E, Mansur RB, Brietzke E. Determinants of adherence to treatment in bipolar disorder: a comprehensive review. J Affect Disord 2013; 149: 247–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leclerc E, Mansur RB, Brietzke E. Determinants of adherence to treatment in bipolar disorder: a comprehensive review. J Affect Disord 2013; 149: 247–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. Why don’t patients take their medicine? Reasons and solutions in psychiatry. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2007; 13: 336–46. [Google Scholar]

15. Sleath B, Rubin RH, Huston SA. Hispanic ethnicity, physician-patient communication, and antidepressant adherence. Compr Psychiatry 2003; 44: 198–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Serretti A, Chiesa A. Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction related to antidepressants: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2009; 29: 259–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Kaufman KR, Wong S, Sivaraaman K, Anim C, Delatte D. Epilepsy and AED-induced decreased libido – the unasked psychosocial comorbidity. Epilepsy Behav 2015; 52(Pt A): 236–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Henning OJ, Nakken KO, Træen B, Mowinckel P, Lossius M. Sexual problems in people with refractory epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2016; 61: 174–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sexual problems in people with refractory epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2016; 61: 174–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Sivaraaman K, Mintzer S. Hormonal consequences of epilepsy and its treatment in men. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2011; 18: 204–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Michael A, O’Keane V. Sexual dysfunction in depression. Hum Psychopharmacol 2000; 15: 337–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Grover S, Ghosh A, Sarkar S, Chakrabarti S, Avasthi A. Sexual dysfunction in clinically stable patients with bipolar disorder receiving lithium. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2014; 34: 475–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. La Torre A, Giupponi G, Duffy DM, Pompili M, Grözinger M, Kapfhammer HP, et al. Sexual dysfunction related to psychotropic drugs: a critical review. Part III: mood stabilizers and anxiolytic drugs. Pharmacopsychiatry 2014; 47: 1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Kaufman KR, Struck PJ. Gabapentin-induced sexual dysfunction. Epilepsy Behav 2011; 21: 324–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Epilepsy Behav 2011; 21: 324–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Kandeel FR, Koussa VK, Swerdloff RS. Male sexual function and its disorders: physiology, pathophysiology, clinical investigation, and treatment. Endocr Rev 2001; 22: 342–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Capogrosso P, Ventimiglia E, Boeri L, Capitanio U, Gandaglia G, Dehò F, et al. Sexual functioning mirrors overall men’s health status, even irrespective of cardiovascular risk factors. Andrology 2017; 5: 63–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Viigimaa M, Doumas M, Vlachopoulos C, Anyfanti P, Wolf J, Narkiewicz K, et al. Hypertension and sexual dysfunction: time to act. J Hypertens 2011; 29: 403–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Francis ME, Kusek JW, Nyberg LM, Eggers PW. The contribution of common medical conditions and drug exposures to erectile dysfunction in adult males. J Urol 2007; 178: 591–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. McCabe MP, Sharlip ID, Lewis R, Atalla E, Balon R, Fisher AD, et al. Risk factors for sexual dysfunction among women and men: a consensus statement from the Fourth International Consultation on Sexual Medicine 2015. J Sex Med 2016; 13: 153–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Risk factors for sexual dysfunction among women and men: a consensus statement from the Fourth International Consultation on Sexual Medicine 2015. J Sex Med 2016; 13: 153–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Lehrner A, Flory JD, Bierer LM, Makotkine I, Marmar CR, Yehuda R. Sexual dysfunction and neuroendocrine correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder in combat veterans: preliminary findings. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016; 63: 271–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Kumsar NA, Kumsar Ş, Dilbaz N. Sexual dysfunction in men diagnosed as substance use disorder. Andrologia 2016; 48: 1229–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Naranjo CA, Shear NH, Lanctôt KL. Advances in the diagnosis of adverse drug reactions. J Clin Pharmacol 1992; 32: 897–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Kennedy SH, Dugré H, Defoy I. A multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sildenafil citrate in Canadian men with erectile dysfunction and untreated symptoms of depression, in the absence of major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2011; 26: 151–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2011; 26: 151–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Seidman S. Ejaculatory dysfunction and depression: pharmacological and psychobiological interactions. Int J Impot Res 2006; 18 (suppl 1): S33–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Rajkumar RP, Kumaran AK. Depression and anxiety in men with sexual dysfunction: a retrospective study. Compr Psychiatry 2015; 60: 114–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Blumentals WA, Gomez-Caminero A, Brown RR, Vannappagari V, Russo LJ. A case-control study of erectile dysfunction among men diagnosed with panic disorder. Int J Impot Res 2004; 16: 299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Badour CL, Gros DF, Szafranski DD, Acierno R. Problems in sexual functioning among male OEF/OIF veterans seeking treatment for posttraumatic stress. Compr Psychiatry 2015; 58: 74–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Smaldone M, Sukkarieh T, Reda A, Khan A. Epilepsy and erectile dysfunction: a review. Seizure 2004; 13: 453–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Seizure 2004; 13: 453–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Hellmis E. Sexual problems in males with epilepsy – an interdisciplinary challenge! Seizure 2008; 17: 136–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Aull-Watschinger S, Pataraia E, Baumgartner C. Sexual auras: predominance of epileptic activity within the mesial temporal lobe. Epilepsy Behav 2008; 12: 124–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Suffren S, Braun CM, Guimond A, Devinsky O. Opposed hemispheric specializations for human hypersexuality and orgasm? Epilepsy Behav 2011; 21: 12–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Fiszman A, Alves-Leon SV, Nunes RG, D’Andrea I, Figueira I. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a critical review. Epilepsy Behav 2004; 5: 818–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Baslet G, Roiko A, Prensky E. Heterogeneity in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: understanding the role of psychiatric and neurological factors. Epilepsy Behav 2010; 17: 236–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Epilepsy Behav 2010; 17: 236–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Doumas M, Douma S. Sexual dysfunction in essential hypertension: myth or reality? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2006; 8: 269–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Iovino P, Pascariello A, Limongelli P, Tremolaterra F, Consalvo D, Sabbatini F, et al. The prevalence of sexual behavior disorders in patients with treated and untreated gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc 2007; 21: 1104–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Missori P, Scollato A, Formisano R, Currà A, Mina C, Marianetti M, et al. Restoration of sexual activity in patients with chronic hydrocephalus after shunt placement. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2009; 151: 1241–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. La Torre A, Giupponi G, Duffy D, Conca A. Sexual dysfunction related to psychotropic drugs: a critical review – part I: antidepressants. Pharmacopsychiatry 2013; 46: 191–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Montejo AL, Llorca G, Izquierdo JA, Rico-Villademoros F. Incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant agents: a prospective multicenter study of 1022 outpatients. Spanish Working Group for the Study of Psychotropic-Related Sexual Dysfunction. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62 (suppl 3): 10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Montejo AL, Llorca G, Izquierdo JA, Rico-Villademoros F. Incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant agents: a prospective multicenter study of 1022 outpatients. Spanish Working Group for the Study of Psychotropic-Related Sexual Dysfunction. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62 (suppl 3): 10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Fossey MD, Hamner MB. Clonazepam-related sexual dysfunction in male veterans with PTSD. Anxiety 1994–1995; 1: 233–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Uhde TW, Tancer ME, Shea CA. Sexual dysfunction related to alprazolam treatment of social phobia. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145: 531–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Kaufman KR. Antiepileptic drugs in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Epilepsy Behav 2011; 21: 1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Calabrò RS, Italiano D, Militi D, Bramanti P. Levetiracetam-associated loss of libido and anhedonia. Epilepsy Behav 2012; 24: 283–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Herzog AG, Drislane FW, Schomer DL, Pennell PB, Bromfield EB, Dworetzky BA, et al. Differential effects of antiepileptic drugs on sexual function and hormones in men with epilepsy. Neurology 2005; 65: 1016–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Herzog AG, Drislane FW, Schomer DL, Pennell PB, Bromfield EB, Dworetzky BA, et al. Differential effects of antiepileptic drugs on sexual function and hormones in men with epilepsy. Neurology 2005; 65: 1016–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Gil-Nagel A, López-Muñoz F, Serratosa JM, Moncada I, García-García P, Alamo C. Effect of lamotrigine on sexual function in patients with epilepsy. Seizure 2006; 15: 142–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Svalheim S, Taubøll E, Luef G, Lossius A, Rauchenzauner M, Sandvand F, et al. Differential effects of levetiracetam, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine on reproductive endocrine function in adults. Epilepsy Behav 2009; 16: 281–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Husain AM, Carwile ST, Miller PP, Radtke RA. Improved sexual function in three men taking lamotrigine for epilepsy. South Med J. 2000; 93: 335–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Grimm RH Jr, Grandits GA, Prineas RJ, McDonald RH, Lewis CE, Flack JM, et al. Long-term effects on sexual function of five antihypertensive drugs and nutritional hygienic treatment in hypertensive men and women. Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study (TOMHS). Hypertension 1997; 29(Pt 1): 8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Long-term effects on sexual function of five antihypertensive drugs and nutritional hygienic treatment in hypertensive men and women. Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study (TOMHS). Hypertension 1997; 29(Pt 1): 8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. La Torre A, Giupponi G, Duffy D, Conca A, Catanzariti D. Sexual dysfunction related to drugs: a critical review. Part IV: cardiovascular drugs. Pharmacopsychiatry 2015; 48: 1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Brixius K, Middeke M, Lichtenthal A, Jahn E, Schwinger RH. Nitric oxide, erectile dysfunction and beta-blocker treatment (MR NOED study): benefit of nebivolol versus metoprolol in hypertensive men. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2007; 34: 327–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Fogari R, Zoppi A. Effects of antihypertensive therapy on sexual activity in hypertensive men. Curr Hypertens Rep 2002; 4: 202–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Coulson M, Gibson GG, Plant N, Hammond T, Graham M. Lansoprazole increases testosterone metabolism and clearance in male Sprague-Dawley rats: implications for Leydig cell carcinogenesis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2003; 192: 154–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2003; 192: 154–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Lindquist M, Edwards IR. Endocrine adverse effects of omeprazole. BMJ 1992; 305: 451–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Lareb. Omeprazole and Erectile Dysfunction (http://databankws.lareb.nl/Downloads/kwb_2006_4_omep.pdf). [Google Scholar]

63. Cascorbi I. Drug interactions – principles, examples and clinical consequences. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2012; 109: 546–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Low Libido? 11 Drugs That Affect Your Sex Drive

Everyone’s heard of medication that can improve your sex life (hello, Viagra!), but some drugs can actually quash it. If you’re feeling less than interested in having sex, the culprit might be in your medicine cabinet.

If you suspect your low libido might be related to your medication, talk to your doctor. (Don’t just stop taking a potential lifesaver.) He or she will probably be able to suggest an alternative. “Communication is key,” says Raymond Hobbs, MD, a senior staff physician in the department of internal medicine at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

“Communication is key,” says Raymond Hobbs, MD, a senior staff physician in the department of internal medicine at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

Health.com: 15 Everyday Habits to Boost Your Libido

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Depression is a well known libido killer, but so are some antidepressants. Prozac, Zoloft, and other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) improve mood by raising serotonin. Unfortunately, that can also lower libido, says Irwin Goldstein, MD, director of sexual medicine at Alvarado Hospital in San Diego. You have options. Wellbutrin and Viibryd are two SSRIs that don’t have this side effect. Or try exercise. A recent study suggests that women taking antidepressants who do cardio and strength training before sex may see improvements in the bedroom.

Tricyclic antidepressants

Since the SSRIs came out in the 1990s, tricyclic antidepressants such as Elavil aren’t used as often. But some doctors do still prescribe them to treat not only depression, but also nerve pain such as that associated with shingles.![]() But these, too, can decrease libido.

If you have a problem, try switching drugs or playing with the dose (after talking to your doctor, of course). “A lot of times you just want to use the lowest dose that accomplishes what you want,” says Dr. Hobbs. “Start low and go slow.”

But these, too, can decrease libido.

If you have a problem, try switching drugs or playing with the dose (after talking to your doctor, of course). “A lot of times you just want to use the lowest dose that accomplishes what you want,” says Dr. Hobbs. “Start low and go slow.”

Health.com: 7 Foods for Better Sex

Birth control pills

Oral contraceptives can lower levels of sex hormones, including testosterone, and therefore may also affect libido. Non-hormonal contraceptives, such as an IUD, are good alternatives, says Dr. Goldstein. Less popular are condoms and diaphragms. Or you can try one of the many other birth control pills available. Bear in mind that the pill can also increase your sex drive. “I’ve seen it go both ways,” says Dr. Hobbs. “Taking the pill is very effective and [women who are] more confident in their birth control device… find that their sexuality improves.”

Proscar

Proscar is used to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia or BPH, better known as an enlarged prostate. It’s a problem most men will encounter as they age. The active ingredient in the drug is finasteride, which prevents testosterone from converting into its active form. Lower testosterone can mean a lower libido.

An alternative treatment for BPH is a procedure known as a transurethral resection of the prostate. This widely performed one-hour operation involves slipping a tube up the urethra and removing a portion of the prostate. That could take care of the prostate problems and the need for medication.

It’s a problem most men will encounter as they age. The active ingredient in the drug is finasteride, which prevents testosterone from converting into its active form. Lower testosterone can mean a lower libido.

An alternative treatment for BPH is a procedure known as a transurethral resection of the prostate. This widely performed one-hour operation involves slipping a tube up the urethra and removing a portion of the prostate. That could take care of the prostate problems and the need for medication.

Health.com: 10 Reasons You’re Not Having Sex

Propecia

This drug is basically the same as Proscar, but it’s used at lower doses to prevent hair loss in men. “It’s the same chemical [finasteride] designed with a new dosing regimen,” says Dr. Goldstein. This means that younger men without prostate problems may also see decreased libido (about 2% of men reported sexual side effects in clinical trials). And there have been reports that the effects can last even after discontinuing the drug, says Dr. Goldstein.

There are alternative hair-loss treatments, such as Rogaine, that don’t have sexual side effects.

Goldstein.

There are alternative hair-loss treatments, such as Rogaine, that don’t have sexual side effects.

Antihistamines

Over-the-counter antihistamines, especially diphendyramine (Benadryl) and chlorpheniramine (Chlor-Trimeton), may alleviate your allergies, but temporarily affect your love life. The solution here could be as simple as carefully timing when you take the drug. “Many of these drugs do not last 24 hours and certainly their side effects don’t,” says Allison Dering-Anderson, Pharm.D., a clinical assistant professor of pharmacy practice at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha. “Antihistamines should be cleared in eight hours in younger and healthier patients.” Keep in mind that antihistamines are also found in many combination cough-and-cold medicines so read the label. You may be taking antihistamines and lowering your libido without knowing it.

Medical marijuana

Marijuana is only approved for medical purposes in 20 states, but regardless of where or why it’s used, pot can have “a significant negative impact both on libido and on ability to perform,” says Dering-Anderson.

If you’re in a place that hasn’t legalized marijuana, obviously you shouldn’t be using it. If you are using marijuana legally and having sex drive problems, talk with a healthcare provider about alternatives for pain and nausea, two common reasons people use marijuana-the-drug.

Health.com: The Secret to Hotter Sex

Anti-seizure drugs

Tegretol can be a game changer for people who have seizures and even for some with bipolar disorder. But the price can be reduced sexual desire. Tegretol and other drugs like it work by preventing impulses from traveling along the nerve cells, but therein lies the problem. An orgasm is similar to a seizure—in both, sensory input triggers a body response—says Dr. Goldstein, so medications that dampen nerve impulses can also reduce pleasurable sensations. In short, the things that used to stimulate you just may not do it for you any more.

If an anti-seizure drug is affecting your libido, ask your doctor about an alternative medication. “That’s not the only drug out there,” says Dr. Hobbs.

“That’s not the only drug out there,” says Dr. Hobbs.

Opioids

Opioid medications can be a blessing in terms of pain relief, but a curse in terms of addiction and sex drive. Studies have shown that opioids such as Vicodin, OxyContin, and Percocet, can lower testosterone, which can affect your libido.

Testosterone therapy—perhaps in the form of a gel—may help men taking opioids for pain who have libido problems, one study found.

Beta blockers

Tens of millions of Americans use beta blockers such as propranolol and metoprolol with great benefit to their hearts, but not necessarily their sex lives. In rare cases, even eye drops containing the beta blocker Timolol (used to treat glaucoma) can decrease libido, says Dering-Anderson.

But there are many beta blockers on the market. They all lower blood pressure, but in different ways. Talk to your doctor to find one that works for all of you.

Benzodiazepines

There have been some reports that anti-anxiety drugs like Xanax can lower your sex drive.

But the underlying anxiety could be the real problem. “Benzodiazepines are used for severe anxiety and many times [people with severe anxiety] aren’t so interested in having sex,” says Dr. Hobbs.

In that case, the medication might calm your anxiety enough to actually enjoy sex, says Dering-Anderson.

This article originally appeared on Health.com.

Contact us at [email protected].

SIDE EFFECTS OF LAMOTRIGINE - DRUG, MEDICINE, MEDICATION

introduction

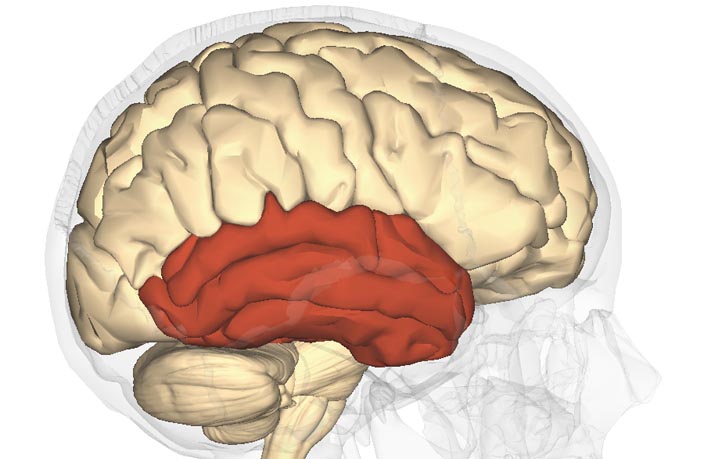

Lamotrigine is a medicine that belongs to a group of medicines called anticonvulsants used to treat seizures such as epilepsy. It is one of the newer anticonvulsants and is mainly used for focal seizure disorders, that is, seizures that are limited to a specific area of the brain.

Lamotrigine has a relatively low level of harm to the liver and kidneys.

review

Even though lamotrigine is generally considered to be a well-tolerated anti-epidemic agent, side effects can occasionally occur. This usually occurs during the dose escalation phase, ie. when the dose of lamotrigine is slowly increased. It should be emphasized that most side effects (with the exception of Stevens-Johnson syndrome) are generally unpleasant, but not dangerous and disappear at the latest after a few weeks. The most common side effects are listed below.

This usually occurs during the dose escalation phase, ie. when the dose of lamotrigine is slowly increased. It should be emphasized that most side effects (with the exception of Stevens-Johnson syndrome) are generally unpleasant, but not dangerous and disappear at the latest after a few weeks. The most common side effects are listed below.

- Dizziness

- Headache

- Fatigence Nausea/vomiting

- Tremor (tremor)

- Joint pain

- Increased irritability

- Allergic skin reactions up to Stevens-Johnson syndrome

Weight gain

Some patients with epilepsy report weight gain while taking lamotrigine. This is based on the fact that lamotrigine is involved in the regulation of hunger in the brain.

In this context, it should be emphasized that gaining weight with lamotrigine is a process that takes several weeks and does not happen overnight. If, just a few days after starting lamotrigine therapy, you suspect that you have gained weight, this is probably a misjudgment. In this case, be patient for at least two to three weeks and objectively evaluate possible weight gain by periodically weighing yourself.

In this case, be patient for at least two to three weeks and objectively evaluate possible weight gain by periodically weighing yourself.

If after this period there is indeed a significant weight gain, contact your treating neurologist. He or she can discuss with you whether lamotrigine should be replaced with another antiepileptic drug or whether weight gain and other measures to stabilize the weight (eg, exercise, diet changes) are possible.

Weight loss

Surprisingly, some patients respond to lamotrigine with weight loss. This is due to the complex regulation of hunger in the brain and the effect of lamotrigine on the mediators involved.

Losing weight also does not happen every day, but takes several weeks. Ideally, you should weigh yourself at least once a week to keep track of your weight loss. Because even if losing a kilo or two is fine for some, losing weight too quickly is not healthy at all and should not be tolerated.

In this context, it is difficult to determine exact limit values due to individual physical characteristics. However, as a rough rule of thumb, weight loss of more than 2 kilograms per week or 5 kilograms per month should be reported to the treating neurologist. Together with the patient, they can weigh whether the weight loss is tolerable or if they should switch to another antiepileptic drug.

However, as a rough rule of thumb, weight loss of more than 2 kilograms per week or 5 kilograms per month should be reported to the treating neurologist. Together with the patient, they can weigh whether the weight loss is tolerable or if they should switch to another antiepileptic drug.

Most patients affected by weight loss with lamotrigine stop losing weight after a multi-week dose escalation phase. For this reason, in most cases it is possible to accept weight loss with lamotrigine and continue therapy until the weight loss is too significant.

fatigue

One of the most common side effects of all antiepileptic drugs, including lamotrigine, is fatigue.

This is due to the mechanism of action of antiepileptic drugs: by blocking certain ion channels that are involved in the transmission of neurons in the brain, the increased excitability of the brain in epileptics is neutralized. This reduces the risk of epileptic seizures, but also increases the mental fatigue of the patient.

In most cases, fatigue occurs at the beginning of lamotrigine therapy and disappears after a few weeks, when the brain and its metabolism have adapted to lamotrigine.

However, some people are so annoyed by being tired during their free time or at work that they sometimes refrain from taking lamotrigine. But skipping a single dose of lamotrigine significantly increases the risk of an epileptic seizure. Therefore, before going down this path in the hope of reducing fatigue, talk to your treating neurologist and keep in mind that in the vast majority of cases, fatigue is only an early stage of therapy.

However, if you can't live with fatigue at all, whether it's because it's particularly severe or because you work in a job that doesn't allow you to get tired, a neurologist may consider switching to another antiepileptic drug together with you. Because any antiepileptic drug can potentially provoke overwork. However, this does not mean that any other antiepileptic drug will cause fatigue in a patient taking lamotrigine.

forgetfulness

Because lamotrigine, like all antiepileptic drugs, disrupts the balance of neurotransmitters in the brain, this leads to temporary cognitive impairment in some patients.

Often they are expressed in the form of forgetfulness. Therefore, if you have the impression that you are more forgetful than usual while increasing your dose of lamotrigine, there may well be a connection with the new drug. If forgetfulness does not greatly limit your leisure and work, it is recommended to continue lamotrigine therapy as planned.

However, if forgetfulness is too severe, consult your treating neurologist instead of skipping lamotrigine on your own. The latter solution is not recommended because a single missed dose increases the risk of an epileptic seizure. Instead, you should discuss with your neurologist whether another antiepileptic drug is right for you, even though, unfortunately, all antiepileptic drugs can, at least theoretically, cause forgetfulness.

skin rash

Some people with epilepsy who take lamotrigine get a rash. In the vast majority of cases, this occurs at the very beginning of lamotrigine therapy. The rash usually starts on the trunk and face, and in more severe cases can spread to the entire body. Initially, this manifests itself in redness of the skin and itching, later blisters and peeling of the skin may appear.

If you develop a rash after taking lamotrigine, contact your neurologist or family doctor as soon as possible. In the vast majority of those affected, the rash is limited to a specific area, red, and itchy, but it can also be a precursor to the life-threatening, severe form of the disease, Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

More on the topic below Drug rash.

hair loss

Even though there have been anecdotal reports of hair loss after taking lamotrigine, there is no proven statistical or biological relationship.

If you experience more than normal hair loss during treatment with lamotrigine, contact your family doctor. They can analyze if you have another, more common cause of your hair loss. Especially if hair loss occurs only after prolonged use of lamotrigine and not in the high dose phase, an association with the active ingredient is much less likely than other potential triggers. The latter include iron deficiency or hormonal changes.

They can analyze if you have another, more common cause of your hair loss. Especially if hair loss occurs only after prolonged use of lamotrigine and not in the high dose phase, an association with the active ingredient is much less likely than other potential triggers. The latter include iron deficiency or hormonal changes.

Do you suffer from hair loss? More on the topic: Hair loss

libido

Some people with epilepsy suffer from sexual dysfunction, usually in the form of decreased libido.

Many antiepileptic drugs are believed to increase this decrease in libido. Lamotrigine is an exception in this context: a clinical study has shown that lamotrigine increases libido. The authors of the study attribute this effect to mood stabilization with lamotrigine.

Even though many patients benefit from this effect because it counteracts the decrease in libido caused by epilepsy, some patients also find it uncomfortable. In this case, together with the neurologist, you can decide whether to switch to another antiepileptic drug. However, in most cases, the effect of lamotrigine on libido is assessed on its own after a few weeks.

However, in most cases, the effect of lamotrigine on libido is assessed on its own after a few weeks.

Side effects on the eyes

Occasionally, double vision may occur during treatment with lamotrigine. This may cause other symptoms such as headaches and nausea. For most people, this side effect only occurs during the first few days to weeks after starting lamotrigine. However, especially in professions in which such visual impairment is unacceptable, it may be necessary to discontinue lamotrigine therapy and switch to another antiepileptic drug.

Nystagmus, i.e. involuntary repetitive convulsive movements of the eyes in the horizontal plane, is one of the most common symptoms of acute overdose of lamotrigine. In most cases, this occurs as a result of double-accidental use of lamotrigine. If you notice any of these symptoms, contact your neurologist or family doctor. He or she can get an idea of the extent of the overdose and, if necessary, take countermeasures.

You can find more information about nystagmus here: Nystagmus.

headache

A relatively large number of patients with epilepsy experience headaches in the first few weeks after starting lamotrigine therapy.

The exact mechanism is not yet known, but the association with lamotrigine interference with neuronal transmission in the brain is clear.

The headache is usually dull and bilateral. The headache usually resolves after a few weeks as the neurotransmitter balance in the brain adjusts to lamotrigine.

If the symptoms are too severe and stressful, contact your treating neurologist. This allows one to analyze whether there really is an association with lamotrigine therapy or if there is another cause of the headache. In the first case, if necessary, you can switch to another antiepileptic drug.

Read more about headaches on the following page: headache

Increase in liver parameters

In particular, during the initial phase of therapy with lamotrigine, some patients experience an increase in liver values.

Liver values are specific liver enzymes that can be measured in the blood using a blood sample. Elevated levels suggest liver tissue damage.

The fact that an increase in liver values may be observed at the beginning of lamotrigine is due to the fact that lamotrigine is excreted through the liver, and at first the body is somewhat overloaded with this task. Since liver cells, like muscles, show a significant training effect, liver values generally return to normal after a few weeks.

However, one or more blood samples should be taken to monitor liver function during the dosing phase. Based on the values determined therein, the doctor can evaluate the degree of liver damage and decide whether it is possible to continue therapy with lamotrigine. Otherwise, the patient is switched to an antiepileptic drug that is excreted not through the liver, but through the kidneys (for example, gabapentin, levetiracetam).

You can find more information about liver values here: Liver values

Side effects on the heart

Some patients report intermittent palpitations on lamotrigine therapy. Even if there are still no studies of statistical or biological relationships, at least it can be assumed that lamotrigine can cause such a side effect in the heart, affecting the center of blood circulation in the brain.

Even if there are still no studies of statistical or biological relationships, at least it can be assumed that lamotrigine can cause such a side effect in the heart, affecting the center of blood circulation in the brain.

Because palpitations are often harmless, but can be very dangerous under certain circumstances, you should consult a neurologist or family doctor if you experience these symptoms. They can check to see if lamotrigine is the most likely cause of the heart palpitations or if there are other causes (such as heart or thyroid disease).

Find out more about palpitations on the following page: Racing Heart

itching

If a patient with epilepsy develops itching while taking lamotrigine, this is usually accompanied by a rash on the itchy area. In this case, a doctor should be consulted, as the rash is usually harmless and temporary, but can also be a precursor to the life-threatening form of Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

If itching occurs on its own, ie without a rash, another cause is likely to be suspected (especially liver and gallbladder disease). In this case, you should also consult a doctor to determine and eliminate the real cause.

In this case, you should also consult a doctor to determine and eliminate the real cause.

You can find more causes of itching here: itching

sweat

To date, there is no known statistical or biological association between lamotrigine and excessive sweating, although anecdotal patient reports indicate this. In particular, if sweating occurs only after long-term use of lamotrigine and not during the dosing phase, other causes are more likely. Your therapist can look into this and figure out the most common causes of excessive sweating. First of all, these are hormonal diseases and diseases of the thyroid gland.

Word search disorders

Due to their interference with neuronal transmission of the brain, cognitive functional impairment may occur, especially in the phase of increasing dosage.

In addition to forgetfulness, one of the most common manifestations is word-finding disorders: people who suffer from this do not want to think in general terms. Since this can lead to uncomfortable situations both in private and at work, significant suffering sometimes occurs.

Since this can lead to uncomfortable situations both in private and at work, significant suffering sometimes occurs.

However, intermittent skipping of lamotrigine is not a recommended solution, as skipping a dose once increases the risk of an epileptic seizure. Therefore, if word search disorders are no longer tolerated, talk to your neurologist about using another antiepileptic drug.

Difficulty concentrating

Concentration disorders are another form of cognitive impairment that may occur during lamotrigine therapy, especially in the initial phase. They usually last only a few days or weeks and disappear after the dose is finished.

However, if they last longer or are so severe that they have a major impact on your personal or professional life, your neurologist can arrange for you to switch to another antiepileptic drug. However, it should be remembered that theoretically any antiepileptic drug can cause impaired concentration.

acne

There are anecdotal patient reports suggesting an association between lamotrigine and the development of acne. However, until now there has been no biological explanation or statistical confirmation of this association. Especially if pimples appear only after long-term use of lamotrigine, and not at the beginning of lamotrigine therapy, another cause (especially hormonal changes) is much more likely. Therefore, in this case, it is recommended to consult a dermatologist.

However, until now there has been no biological explanation or statistical confirmation of this association. Especially if pimples appear only after long-term use of lamotrigine, and not at the beginning of lamotrigine therapy, another cause (especially hormonal changes) is much more likely. Therefore, in this case, it is recommended to consult a dermatologist.

Tremor (tremor)

Occasionally, people with epilepsy who take lamotrigine experience shaking, which, when more severe than usual, is called a tremor.

The exact mechanism by which lamotrigine causes tremors is still being reversed, but the link to the effect on neuronal transmission in the brain is clear. As a rule, the tremor goes away on its own after the end of the drug phase, so therapy is usually not necessary.

This is only a cause for concern if you work in an occupation in which the tremor is intolerable, or if the tremor is severe enough to significantly reduce your quality of life. In these cases, the neurologist may discuss whether lamotrigine therapy should be discontinued and another antiepileptic drug chosen.

You can find more information about jolts here: tremor

sleep disorders

Paradoxically, the more common side effects of lamotrigine include not only increased mental fatigue but also insomnia. One explanation for this could be that the fatigue caused by lamotrigine means that the person is being gentle with themselves and reducing physical stress. Since the increased fatigue only affects the mind and not the body, the latter is practically not “busy” at the end of the day and therefore not in the mood to go to bed.

Persistent sleep disturbances can be a serious burden on a person's well-being and quality of life. Therefore, in this case, it is advisable to consult a family doctor or a neurologist. Together with the patient, the physician can decide whether the insomnia can still be tolerated and whether other measures (eg, herbal or synthetic sleeping pills, exercise) can be taken or whether a switch to another antiepileptic drug is necessary.

joint pain

Some people who take lamotrigine complain of musculoskeletal pain, mainly affecting the joints. The biological mechanism is still unclear. Other causes are more likely, especially if joint pain does not occur during the dosing phase, but only after long-term use of lamotrigine.

These include rheumatic or infectious diseases. Your family doctor will determine the most likely cause of your joint pain and refer you to a specialist if necessary. If no other cause can be found and lamotrigine is determined to be the most likely cause of joint pain in the process of being eliminated, you should talk to a neurologist about switching to another antiepileptic drug.

More about rheumatism: Rheumatoid arthritis

Gender differences in sexual function in patients with epilepsy

Manuscript

00460461 Kalinina Lina Vladimirovna

Gender differences in sexual function in patients

epilepsy.

14. hours at a meeting of the dissertation council D 208.044.01 at the Federal State Institution "Moscow Research Institute of Psychiatry of the Federal Agency for Health and Social Development" at the address: 107076, Moscow , st. Amusing, d.Z.

hours at a meeting of the dissertation council D 208.044.01 at the Federal State Institution "Moscow Research Institute of Psychiatry of the Federal Agency for Health and Social Development" at the address: 107076, Moscow , st. Amusing, d.Z.

The dissertation can be found in the scientific library of the Moscow Research Institute of Psychiatry of Roszdrav.

The abstract has been sent out “¿//” since 2010

Scientific secretary of the dissertation council, doctor of medical sciences

T.V. Dovzhenko

General performance

Research relevance. Sexual health is one of the main indispensable conditions for the quality of life of each individual. In recent years, WHO recommends considering sexual health in the context of biopsychosocial interaction, which, in essence, reflects the multidimensional influence of many factors, both biological and psychological and social nature, on the state of sexual health. Neurological and psychiatric diseases are among the group of diseases that most often cause sexual disorders in humans. It is well known that in traumatic brain injury (TBI), depending on the location of the injury, a specific pattern of sexual dysfunction occurs. So, with damage to the prefrontal cortex, there are pictures of apathy with hyposexuality and, less often, disinhibition with hypersexuality. In the case of pathology of the hypothalamic-pituitary region, there is a decrease in libido, impotence and dysmenorrhea. More complex and ambiguous violations of sexual function occur with epilepsy. Epilepsy, being formally a neurological disease, is characterized by a rich palette of various mental disorders, among which sexual dysfunctions occupy one of the first places in terms of frequency of occurrence.

It is well known that in traumatic brain injury (TBI), depending on the location of the injury, a specific pattern of sexual dysfunction occurs. So, with damage to the prefrontal cortex, there are pictures of apathy with hyposexuality and, less often, disinhibition with hypersexuality. In the case of pathology of the hypothalamic-pituitary region, there is a decrease in libido, impotence and dysmenorrhea. More complex and ambiguous violations of sexual function occur with epilepsy. Epilepsy, being formally a neurological disease, is characterized by a rich palette of various mental disorders, among which sexual dysfunctions occupy one of the first places in terms of frequency of occurrence.

Observations about the relationship between epilepsy and sexual disorders have been known for thousands of years, and go back to the works of Hippocrates, Galen and Cornelius Celsus (Suyagin VM, 1969). 6 modern works of the last 15-20 years also confirmed the relationship between epilepsy and sexual dysfunctions. It has been established that the frequency of sexual dysfunctions in epilepsy exceeds that in the general population, and according to various data is at least 20-29% in women and 8-55% in men. Moreover, it is emphasized that sexual dysfunctions are more common in epilepsy than in other neurological diseases, and

It has been established that the frequency of sexual dysfunctions in epilepsy exceeds that in the general population, and according to various data is at least 20-29% in women and 8-55% in men. Moreover, it is emphasized that sexual dysfunctions are more common in epilepsy than in other neurological diseases, and

decrease in sexual activity, along with excessive religiosity and hypergraphia, is characteristic of an epileptic personality, which is called the "Geschwind-Gastaut triad". All this suggests that there are common pathogenetic mechanisms in epilepsy and sexual dysfunctions, although the patterns of occurrence of these disorders have not been fully established. However, there are also observations to the contrary. Thus, in particular, the possibility of developing orgasmic auras in the structure of complex partial and secondary generalized seizures, as well as the so-called spontaneous orgasm, erection states and sexual arousal in general, within the framework of simple partial seizures in epilepsy is indicated (Erickson, 1945; Currier et al. , 1971; Stoffels et al., 1980, Calleja et al., 1988; Remillard et al., 1983; O'Donovan et al, 2000; Panayiotopoulos, 2007).

, 1971; Stoffels et al., 1980, Calleja et al., 1988; Remillard et al., 1983; O'Donovan et al, 2000; Panayiotopoulos, 2007).

In general, it should be emphasized that the existing sexological studies in epileptology are still few, and the results obtained have not yet received an unambiguous assessment. It is not completely clear to what extent the basic characteristics of epilepsy (form of the disease, type, frequency of seizures, gender, type and dose of antiepileptic drugs) affect sexual function. Equally, it remains unknown whether the personality characteristics of the premorbid period and the characteristics of the psychopathological status have a bearing on the state of sexual function in epilepsy.

The purpose of the study: to create a system for the early detection of neuropsychiatric risk criteria for sexual health and their correction in patients with epilepsy. The main objectives of the study were as follows:

1) Study of the influence of the basic characteristics of epilepsy (form, semiotics and frequency of seizures, localization and lateralization of the focus) on sexual function in patients with epilepsy.

2) Determination of the role of antiepileptic drug therapy (AED) in terms of risk factors or, on the contrary, correction of sexual disorders in epilepsy

3) Establishing the role of premorbid personality characteristics in terms of the risk of sexual dysfunction in epilepsy

4) The study of psychopathological disorders in patients with epilepsy with sexual dysfunctions.

5) Analysis of gender differences in neuropsychiatric correlates of sexological disorders in epilepsy.

Scientific novelty of the research. For the first time, the influence of the basic characteristics of epilepsy, the personal characteristics of patients and their psychopathological state on sexual function was shown for the first time on a representative clinical material. An ambiguous relationship has been established between different basic characteristics of epilepsy, AED, and personality traits with individual components of sexual function in both men and women. Gevder differences were found in the formation of sexual dysfunctions arising under the influence of the studied disease factors and depending on personality characteristics. The practical significance of the work. When assessing sexual health in patients with epilepsy, one should take into account a set of basic characteristics, features of AED therapy, the patient's personality structure, and the symptoms of a concomitant psychopathological disorder. It was found that the significance of these characteristics of different modalities is different for patients of different sexes, and these characteristics can have a multidirectional effect on individual components of sexual function. In men, the greatest links with sexual disorders have signs of mental status, in women - features of the personality structure. Among the basic characteristics, the most unfavorable value for the global assessment of SF in men is the frequency of AIV, while in women it is a positive value.

The practical significance of the work. When assessing sexual health in patients with epilepsy, one should take into account a set of basic characteristics, features of AED therapy, the patient's personality structure, and the symptoms of a concomitant psychopathological disorder. It was found that the significance of these characteristics of different modalities is different for patients of different sexes, and these characteristics can have a multidirectional effect on individual components of sexual function. In men, the greatest links with sexual disorders have signs of mental status, in women - features of the personality structure. Among the basic characteristics, the most unfavorable value for the global assessment of SF in men is the frequency of AIV, while in women it is a positive value.

seizure severity. AED therapy has a greater effect on SF in men and less in women. In this case, in men, the use of LMT should be avoided and CBM is recommended.

Publications and approbation of results. The main results of the study are reflected in 6 scientific publications, including 2 in the publication recommended by the Higher Attestation Commission of Russia.

The main results of the study are reflected in 6 scientific publications, including 2 in the publication recommended by the Higher Attestation Commission of Russia.

The dissertation was approved at the problematic commission "Clinical and pathogenetic problems of psychiatry" at the Federal State Institution "Moscow Research Institute of Psychiatry of the Federal Agency for Health and Social Development" October 21, 2009of the year.

Scope and structure of work. The dissertation is presented on 96 typewritten pages and consists of an introduction, a literature review, a chapter describing the materials and research methods, three chapters containing a summary of the results of the study, 11 tables, a conclusion, conclusions, an appendix and a list of references containing 107 sources. Defense provisions. 1) Epilepsy has a complex and multidirectional effect on the state of sexual function in patients. At the same time, both the basic characteristics of epilepsy and the nature of the therapy being carried out, as well as personal characteristics of the premorbid period and concomitant psychopathological symptoms, are important; 2) Separate characteristics of epilepsy, the nature of the therapy, personality characteristics and comorbid psychiatric pathology have an ambiguous, and more often multidirectional effect on men and women with epilepsy; 3) Partial forms of epilepsy are characterized, in general, by a less favorable prognosis than idiopathic forms, both in men and women. In men, simple partial seizures (SPS) and secondary generalized seizures (GAS) are generally beneficial for sexual function, while complex partial seizures (CSPS)

In men, simple partial seizures (SPS) and secondary generalized seizures (GAS) are generally beneficial for sexual function, while complex partial seizures (CSPS)

indicate a poor prognosis. In women, most seizures have a positive effect on sexual function; 4) Personal characteristics of the premorbid period are not equally related to sexual dysfunction in men and women. In women, they are more important in predicting the global assessment of sexual function than in men. At the same time, the possibility of predicting sexual disorders by personal characteristics in women is 3 times higher than in men; 5) Symptoms of comorbid psychopathological disorders are more important for sexual dysfunction in men than in women. The accuracy of the global assessment of sexual dysfunction in men is 1.5 times higher than in women.

Materials and research methods. 110 patients with epilepsy were studied, including 45 men and 65 women. The average age of the studied sample of patients was 29. 4+-8.0 years and varied in the sample from 18 to 47 years. The average age of onset of epilepsy was 15.8+-9.6 years, the duration of epilepsy was 13.6+-7.5 years, the duration of sexual disorders was 1.0+-2.4 years and varied from 0 to 10 years during the entire sample. The duration of sexual disorders was assessed solely on the basis of the reports of patients, and therefore was purely subjective. Among the entire studied contingent of patients, subjective complaints of sexual difficulties were detected in 28 out of 110 people (25.4%). In other cases, patients did not show any complaints. The state of sexual function was assessed using formalized scales developed in the Department of Sexopathology of the Moscow Research Institute of Psychiatry of Roszdrav.

4+-8.0 years and varied in the sample from 18 to 47 years. The average age of onset of epilepsy was 15.8+-9.6 years, the duration of epilepsy was 13.6+-7.5 years, the duration of sexual disorders was 1.0+-2.4 years and varied from 0 to 10 years during the entire sample. The duration of sexual disorders was assessed solely on the basis of the reports of patients, and therefore was purely subjective. Among the entire studied contingent of patients, subjective complaints of sexual difficulties were detected in 28 out of 110 people (25.4%). In other cases, patients did not show any complaints. The state of sexual function was assessed using formalized scales developed in the Department of Sexopathology of the Moscow Research Institute of Psychiatry of Roszdrav.

Along with this, the basic characteristics of epilepsy were assessed in the form of the form of the disease, the semiotics of seizures and their frequency, the focus of epileptic activity, as well as the nature of anticonvulsant therapy (type of AED and its maximum daily dose).

For. Seizure severity was assessed using the National Hospital Seizure Severity Scale (NHS3) developed by O'Donoghue et al. (1996).

Personal characteristics of patients with epilepsy and psychopathological symptoms were assessed strictly in the interictal period. The Munich Personality Test (MJIT) developed by von Zerrsen (1988). The SCL-90 scale (Derogatis et al., 1973) was used to assess concomitant psychopathological symptoms of epilepsy and sexological disorders.

Analysis of the obtained data was carried out using the program "Statistics" - 8th version. Student's t-test was used to compare independent variables and correlation analysis (Pearson's method) to evaluate relationships between quantitative variables. At the final stage, the stepwise multiple regression method was used (to find the dependence of the global assessment of sexual function on a set of neuropsychiatric indicators). Results of the study and their discussion. In accordance with the purpose and objectives, the study was divided into two stages. At the first stage, an analysis was made of the relationship between basic characteristics and sexological disorders in epilepsy. At the second stage, an analysis was made of the relationship between personality characteristics and psychopathological symptoms with sexual disorders in epilepsy. Analysis of the interaction of basic characteristics and sexological disorders in epilepsy was also carried out in several stages. At the first stage of the study, patients of the two main studied groups (idiopathic and partial forms of epilepsy) were compared according to the main sexological parameters separately for men and women. Partial epilepsy was characterized by an earlier age of onset and an earlier age of onset of sexual disorders (24.6+-6.1 vs.

At the first stage, an analysis was made of the relationship between basic characteristics and sexological disorders in epilepsy. At the second stage, an analysis was made of the relationship between personality characteristics and psychopathological symptoms with sexual disorders in epilepsy. Analysis of the interaction of basic characteristics and sexological disorders in epilepsy was also carried out in several stages. At the first stage of the study, patients of the two main studied groups (idiopathic and partial forms of epilepsy) were compared according to the main sexological parameters separately for men and women. Partial epilepsy was characterized by an earlier age of onset and an earlier age of onset of sexual disorders (24.6+-6.1 vs.

32.3+-10.8 years; p=0.018) compared with idiopathic epilepsy in men. Given that epilepsy itself had an earlier age of onset than the age of onset of sexual dysfunction, the occurrence of the latter can be explained by the development of epilepsy or concomitant therapy with AEDs.

From other indicators of sexual function in men, statistically significant differences were obtained in 2 indicators. The first of them included the "Assessment of the success of sexual life", (3.0+-0.9in patients with idiopathic epilepsy versus 1.7+-1.3 in patients with partial epilepsy; p=0.0085). The second indicator - "Duration of sexual intercourse" (respectively 2.8+-1.5 versus 3.6+-1.0; p=0.046) was statistically significant only when applying a one-sided test. This allows us to speak only about the tendency to its higher values in partial epilepsy.

Thus, it can be considered that the earlier onset of the partial form of epilepsy in men contributes to an earlier onset of sexual disorder and a lower subjective assessment of their sexual abilities compared to the idiopathic form.

When comparing men with left-sided and right-sided foci, no statistically significant differences were found in any of the above indicators. It is also important to note that a positive correlation was found between the age of onset of epilepsy and the age of onset of sexual disorders (r=0. 80; p<0.01), as well as between the duration of epilepsy and the duration of sexual disorders (r=0.38; p< 0.05).

80; p<0.01), as well as between the duration of epilepsy and the duration of sexual disorders (r=0.38; p< 0.05).

Comparison of idiopathic and partial forms of epilepsy in the group of women by sexual characteristics showed a difference between them (respectively 25.0+-6.3 versus 32.5+-7.6; p=0.012). Thus, the age of onset of sexual dysfunction in women was later in partial epilepsy.

Along with this, it is noteworthy that the severity of orgasm in women was higher in idiopathic epilepsy (3.1+-0.6 versus 2.4+-0.5; p=0.021). Women also showed differences in three more measures when using a one-tailed test. They included the level of sexual activity (I.E. > P.E.), duration of intercourse (I.E. > P.E.), and duration of sexual dysfunction (I.E. < P.E.). This corresponds to a later onset of the partial form of epilepsy in women compared to the idiopathic form.

Comparison of indicators of sexual function between left-sided and right-sided foci in partial epilepsy in the group of women showed that with left-sided foci there were lower values of such indicators as "Physical well-being after the act" (3. 2 + -0.4 vs. 3.7 +-0.5; p=0.024), "Mood after acts" (3.2+-1.0 versus 4.0+-0.1; p=0.022) and "Level of sexual activity" (1.6+ -0.9 vs. 2.3+-0.8; p=0.041).

2 + -0.4 vs. 3.7 +-0.5; p=0.024), "Mood after acts" (3.2+-1.0 versus 4.0+-0.1; p=0.022) and "Level of sexual activity" (1.6+ -0.9 vs. 2.3+-0.8; p=0.041).

At the next stage of the study, we studied correlations between the frequency of seizures of different structures and the main parameters of formalized sexological scales separately for men and women. The main data of this section are presented in tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Basic characteristics and sexual manifestations in men

Characteristics of disorders Simple partial seizures (SPS) Complex partial seizures (SPS) Secondary generalized seizures (GAS)

Need for sexual intercourse 0.19 0.6"; p<0.01 -0.09 -0.27

Mood before the act 0.71; p<0.01 0.11 0.02 -0.10

Sexual enterprise 0.33 0.18 0.10 0.07

Frequency of acts -0D1 0.22 0.18 -0.15

Erection -0.27 -0.72; p<0.01 0.27 -0.01

Duration of sexual intercourse -0.05 0.28 0.15 -0.28

Frequency of sexual expulsions -0. 18 0.39; p<0.05 0.14 -0.07

18 0.39; p<0.05 0.14 -0.07

Mood after the act 0.11 -0.15 0.43; p<0.05 -0.18

Evaluation of the success of sexual life 0.55; p<0.01 -0.48; p<0.01 0.17 -0.01

Duration of sexual disorder 0.07 -0.72; p<0.01 0.36; p<0.95 0.16

Global estimate 0.17 -0.15 0.27 -0.09

Statistically significant values are marked in bold

In the group of men, seizures, depending on their semiotics, were associated in different directions with the characteristics of sexual disorders. Thus, simple partial seizures had positive associations with mood and the indicator of "success in sexual life." More complex relationships with sexual parameters have been established for complex partial seizures. On the one hand, they had a negative value for the severity of erection, negatively correlated with the indicator of "success of sexual life" and the duration of sexual dysfunction. On the other hand, they were positively correlated with the need for sexual intercourse and, accordingly, with the frequency of sexual functions. Secondary generalized seizures were positively associated with good mood after sexual intercourse and were consistent with a short duration of sexual distress. The indicator of the severity of seizures according to the IHOS scale did not have a significant correlation with any of the indicators of male sexual dysfunction.

Secondary generalized seizures were positively associated with good mood after sexual intercourse and were consistent with a short duration of sexual distress. The indicator of the severity of seizures according to the IHOS scale did not have a significant correlation with any of the indicators of male sexual dysfunction.

In the group of women (Table 2), simple partial seizures correlated positively with 5 indicators of sexual parameters. At the same time, a high frequency of simple partial seizures corresponded to a high severity of orgasm, good somatic health and mood after acts, and high sexual activity, which obviously predetermined a positive correlation with the global assessment.

In contrast, complex partial seizures were related to sexual parameters in a more complex way. On the one hand, a high frequency of complex partial seizures was negatively correlated with menstrual function, i.e. corresponded to menstrual dysfunction and, along with this, corresponded to a negative attitude towards sexual activity. On the other hand, a high frequency of SPP correlated positively with the severity of orgasm.

On the other hand, a high frequency of SPP correlated positively with the severity of orgasm.

Secondary generalized seizures in women had a positive relationship with menstrual function (high incidence of AIV corresponds to normal menstrual function, low - disturbed menstrual function) and attitude to sexual activity (high frequency of AIV - positive attitude to sexual intercourse). Along with this, there was a positive relationship with physical well-being after sexual intercourse.

Table 2 Basic characteristics and sexual manifestations in women

Characteristics of disorders Simple partial seizures (SPS) Complex partial seizures (SPS) Secondary generalized seizures (GAS) SBZ

Menses 0.09 -0.54; p<0.01 0.50; p<0.01 0.43; <8.05