Is marriage relevant in the 21st century

Marriage in the 21st Century

James P. Cunningham

Michigan Bar Journal

January 2004

Fast Facts:

- Some form of formal marital dissolution has always been part of human experience.

- Women with choice about when and if to become pregnant and, by extension, an affordable choice when and if to stay in a marriage, effectively doubles the size of the married population reconsidering their vows.

- If one-half of all marriages will divorce, then statistically if not culturally, divorce is normal.

For the first time in human history, divorce has replaced death as the most common endpoint of marriage. This unprecedented shift in patterns of human coupling and uncoupling requires a new paradigm, that is, a more humane approach for social policy, family law, and marital therapy. The subtitle of this article is borrowed, with grateful permission, from a carefully researched study by prominent family psychologist William M.

Pinsof, Ph.D. Both intriguing and at times controversial, his essay is worthy of a wider audience.1

A Brief History of Marriage

The Pre-modern Experience

Historian Beatrice Gottlieb researched marriage in the Western World from 1400 to 1800. From the end of the black plague to the beginning of industrialization, she found marriages seldom lasted longer than 20 years. During this period:

Almost all broke up, not because of legal action but because of death...The fragility of marriage was deeply embedded in the consciousness...hardly anyone grew up with a full set of parents or grandparents. From the point of view of the married couple, this meant that however fond they were of each other, they were likely to feel it necessary to make provisions for a future without the other. Marriage ''contracts'' were primarily provisions for widowhood. For couples who were not particularly fond of each other, it was not unrealistic to dream of deliverance by death.2

Marriages were viewed as permanent, but relatively unstable and short lived. ''In the past when a couple got married they could not help but have ambivalent expectations about the durability of their relationship,'' reports Pinsof. ''While they were tightly locked into it and could not easily get out of it by legal means, they knew very well that the time was probably not far off they would part.''

The Modern Marital Experience

Some form of formal marital dissolution has always been part of human experience. From the mid 19th Century, the dawn of industrialization, the probability of a marriage ending in divorce (or annulment) hovered below 10 percent. 1974 marked the year that the most common endpoint of marriage became divorce. By 1985, the divorce rate had steadily increased to over 55 percent. Over the past 20 years, it has remained level at about 50 percent.

Dr. Pinsof uncovered an interesting fact: the mean length of marriage changed very little over this period of time. It remained surprisingly constant, hovering at about 20 years. In other words, after almost 600 years, 500 of which the predominant terminator was death, and in modern times divorce, a substantial body of empirical data inferred hard wiring of one generation.

It remained surprisingly constant, hovering at about 20 years. In other words, after almost 600 years, 500 of which the predominant terminator was death, and in modern times divorce, a substantial body of empirical data inferred hard wiring of one generation.

The Death to Divorce Transition

While modern human life is dramatically different from its past, this does not, ipso facto, explain away this seeming anomaly of the family. Dr. Pinsof's carefully documented study attempts to identify the reasons behind what he calls ''the death to divorce transition.''

Increased Life Span

A fundamental and unprecedented transformation is that we live longer and better. From 1900 to 2000, the average human life span increased more than 25 years. In other words, persons surviving to adulthood can now expect to have ''two adult life cycles'' when compared to our forbears. As well, the mortality decline in this century is greater than that which has occurred during the preceding 250 years.

Shouldn't an increased life span result in longer marriages? Logic suggests yes. But as the abundant statistics clearly demonstrate, this was not the case. As people lived longer, the duration of their marriages did not substantially increase. Instead, dissolution rates skyrocketed.

And not only are we living twice as long as our grandparents, but we are living better qualitatively. A healthy and vigorous life is a reality for many people in their late 80s. People's values, goals, and beliefs change as they age. Are any of us the same at 40 as we were at 20? Or will be at 55 and 80?

Since most people now marry between the ages of 25 and 35, in all probability they will have changed, and ''grown'' substantially by the time they reach 50. The arc of circumstance in life, careers, grown children, death events, often merge, or even initiate an individual's capacity for personal growth and adult development.

An alternative explanation is that people's sense of their relational future at 35 and 40 is very different now than it was before the 20th Century. The prospect of another 40 or 50 years with decent health and possibilities for individual growth in an unhappy relationship is very different than the prospect of another 10 or so years under the same conditions.

The prospect of another 40 or 50 years with decent health and possibilities for individual growth in an unhappy relationship is very different than the prospect of another 10 or so years under the same conditions.

Role of Women

As well as living longer and healthier, Dr. Pinsof identifies the changing ''biopsychosocial'' roles of women as having an enormous impact on this transition. The reduced fertility rate, through the diffusion of modern contraceptive technology, has resulted in much smaller families in the past half century. Several cited studies demonstrate that the likelihood of divorce is lower among larger families and greater among smaller ones.

Another concurrent factor is the rise in women's income. Financial independence, especially together with contraceptive freedom, has greatly increased choice. Women have freedom of opportunity heretofore largely unavailable for this half of the marital partnership. Women with choice about when and if to become pregnant and, by extension, an affordable choice when and if to stay in a marriage, effectively doubles the size of the married population reconsidering their vows.

Social Values and the Law

Undoubtedly, one of the most debated factors in the effort to explain the increase in divorce in the last 30 years is the reformation of divorce laws, the rise of ''no-fault.'' Pinsof cites over 10 independent studies exploring the impact of no-fault divorce laws. All conclude easing statutory requirements did not ''cause'' people who were otherwise inclined, to divorce. Empirical evidence suggests that blaming divorce on no-fault statutes places the cart before the horse. It most probably reflects, he concludes, a movement to minimize the social and legal stigma associated with divorce and reduce the psychosocial trauma historically associated with it.

Inclination to Stay Married/Capacity to Divorce

If one-half of all marriages will divorce, then statistically if not culturally, divorce is ''normal.''3 This perspective does not view divorce as a failure of the inclination to remain married but its own event, and one with its own potentially positive outcome. Pinsof states.

Pinsof states.

Any marital therapist who has treated a wide variety of couples over a number of years, knows that the divorce decision, however initially difficult, is in a number of circumstances a positive act. In such circumstances, staying married may reflect an inability to pursue what may be in the best interests of oneself, one's partner, and even one's children.

The capacity to divorce derives from one or both individuals in a couple concluding that its benefits outweigh that of staying. In essence, Pinsof argues that people are rational decision-makers and a disinclination to stay married is a rational act perceived by the individuals making the decisions as a beneficial step for their continuing lives. In this day and age, divorce is not a failure, but to the extent to which an individual is disposed or inclined to consider it, a realistic and oftentimes positive option.

Wanted: New Paradigms

Having come to a tentative explanation of the death to divorce transition, Pinsof reasons that we must rethink our world to incorporate the new marital realities.

The Courts

Family law practitioners will agree with Dr. Pinsof's conclusion that ''rethinking domestic relations law is likely to be a lengthy, contentious process.'' A new system of thought and law must transcend the dichotomous ''marriage versus everything else'' model by legally recognizing and appropriately protecting non-marital cohabiting, non-marital child bearing and child rearing, as well as marriage.

Statute and case law regarding the family and social policy generally are struggling to catch up with the new realities of human pair bonding and re-pair bonding. Examples abound. Attempts are being made to determine and enforce the rights and obligations of non-marital partners, unmarried parents to their children, rights of grandparents to their grandchildren, and the rights of gays and lesbians to marry-and divorce.

The courts, and to a lesser extent, legislatures, are coming to increasingly understand the value of co-parental relationships and protecting healthy child development as an alternative to adversarial proceedings. The major challenge to the distigmatization and cultural normalization of marital dissolution is the creation of non-traumatic legal processes that do not become party to the acrimony and alienation that many families unnecessarily and unfortunately bring to the divorce process.

The major challenge to the distigmatization and cultural normalization of marital dissolution is the creation of non-traumatic legal processes that do not become party to the acrimony and alienation that many families unnecessarily and unfortunately bring to the divorce process.

Social Sciences

Social science as well needs to confront the implications of the death to divorce transition. Conceptualizing divorce as a ''bad outcome'' whose probability needs to be reduced misses the point. Uncoupling is here to stay. About half of all people who marry will probably experience it at some point in their lives.

Research needs to move beyond a judgmental attitude towards divorce, and view it as a normal outcome that may be desirable or undesirable. For example, ''Stop comparing children of divorce to children of marriages,'' Pinsof recommends, to determine if divorce is emotionally and physically bad for children. That is the wrong comparison.

Children of divorce, if they are to be compared to anyone, should be compared to children in families with unhappy or deeply troubled marriages. People who divorce do not do so because they are happy with each other. A substantial number of couples who divorce have miserable marriages with high rates of depression and conflict. Pinsof states, ''It is the rare social scientist who would assert that deeply troubled families are better for child rearing than a two-home couple that can coparent collaboratively and effectively.''

People who divorce do not do so because they are happy with each other. A substantial number of couples who divorce have miserable marriages with high rates of depression and conflict. Pinsof states, ''It is the rare social scientist who would assert that deeply troubled families are better for child rearing than a two-home couple that can coparent collaboratively and effectively.''

While such data is only beginning to emerge, it will most likely confirm the hypothesis that, in most situations, a good divorce is better for all concerned than a bad marriage.

Mental Health Services

Therapy for marriages and couples has only recently emerged as a distinct form of mental health intervention, which by and large has coincided with the death to divorce transition. Are mental health practitioners integrating the implications of the death to divorce transition and the emerging pair bonding paradigm into their theories and interventions?

While family and marital therapists help couples stay together and dissolve their marriages every day, Dr. Pinsof concludes that most forms of therapy are designed to ''strengthen'' the marriage. Given that many of their patients will probably divorce anyway, is it fair to say that therapy has failed? In medicine for example, it would be irresponsible and unethical not to train obstetricians to do non-vaginal deliveries, or not to train oncologists to treat patients who don't respond to chemotherapy.

Pinsof concludes that most forms of therapy are designed to ''strengthen'' the marriage. Given that many of their patients will probably divorce anyway, is it fair to say that therapy has failed? In medicine for example, it would be irresponsible and unethical not to train obstetricians to do non-vaginal deliveries, or not to train oncologists to treat patients who don't respond to chemotherapy.

Mental health professionals should help couples divorce as well as try to stay together. They need to develop more explicit theories and practices to help couples exit from their existing pair bond structure, with minimal damage to both parties (and their children).

Dr. Pinsof believes the mental health profession, in all probability, will become the primary social educator for marriage's new paradigm. Increasingly, they will need to think of themselves as offering a set of services to couples and potential couples. Services will range from improving their patients' marriage, to educating what alternative pair bond structures are most appropriate at this junction in their lives, to repairing damaged relationships or facilitate their constructive dissolution.

Conclusion

Divorce has replaced death as the primary terminator of marriage. It has statistically become an overwhelmingly, albeit still an extremely difficult, ''normal'' life event. A number of factors have caused this death to divorce transition. The lengthening, and the qualitative improvement of the human life span, and enhanced opportunity for personal growth are two reasons. Reproductive technology has brought choice, resulting in smaller families. Social and economic improvement in women's lives, finally approaching that of their husbands, has doubled the couple's specter of choice.

''Divorce'' is no longer the bankruptcy, or bad result of marriage choice. Indeed it is altogether too common to view it as anything other than culturally ''normal.'' The emergence of new relationships, family values, and laws have contributed to a fundamental transformation in pair bonding.

Dr. Pinsof's hope is to further stimulate law, social science, and mental health practices, to integrate what can be learned about human pair bonding from the events of the 20th Century into a new paradigm, a new and beneficial way of betterment for the family in the 21st Century.

Footnotes

1. This author thanks William M. Pinsof, Ph.D., President of the Family Institute at Northwestern University and Director of Northwestern Center for Applied Psychological and Family Studies. His articles, The Death of ''Till Death Do Us Part'': The Transformation of Pair Bonding in the 20th Century can be found at Family Process, Volume 41, No. 2, 2002.

2. Gottlieb, B. (1993). The family in the Western World: From the Black Death to the Industrial Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press. P. 108. Hereafter, for ease of reading, citations to Dr. Pinsof's thorough recitation of authority are omitted. For those interested, reference is made to his original article.

3. "Normal" is used in the specific context of the statistical sense-meaning ''most common.'' See Walsh, Normal Family Processes (1982, 1993).

Biography

James P. Cunningham is a partner with the law firm of Williams, Williams, Ruby & Plunkett, P. C. in Birmingham, Michigan. For 23 years his practice has been limited to the family. He is a fellow in the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers, Michigan Chapter.

C. in Birmingham, Michigan. For 23 years his practice has been limited to the family. He is a fellow in the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers, Michigan Chapter.

- James Cunningham

21st Century Marriages Not What They Used to Be

A new study suggests the institution of marriage has changed, reflecting women’s educational attainment, earnings potential, and involvement in the workforce.

The commitment of women to jobs and careers has reduced, or eliminated economic disparities between men and women. This has changed the primary function of marriage so that now marriage is a vehicle to provide a long-term stable home for children.

Accordingly, investments in children have become a driving force in preserving the institution of matrimony, say researchers.

University of California, Santa Barbara demographer Shelly Lundberg, Ph.D., and economist Robert Pollak, Ph.D., of Washington University in St. Louis examined Americans’ changing sensibilities about marriage, using economics as a measuring tool.![]()

Lundberg and Pollak contend that families with high incomes and high levels of education have the greatest incentives to maintain long-term relationships. Their findings appear in the journal The Future of Children.

The researchers argue that, since the mid-20th century, marriage has morphed from an institution based on gender specialization — the man earns the income and the woman stays home to take care of the children — to a means of supporting intensive investment in children.

“In a gender-specialized economy, where men and women are playing very different productive roles, you need the long-term commitment to protect the vulnerable party, who in this case is the woman,” explained Lundberg.

“But when women’s educational attainment increased and surpassed that of men, and women became more committed to jobs and careers, the kind of economic disparity that supported a division of labor in the household eroded.”

If this scenario is true for people across the economic spectrum, Lundberg posited, then statistics should show a broad-based retreat from marriage. Evidence, however, bears out something entirely different.

Evidence, however, bears out something entirely different.

“What we see is a striking adherence to traditional marriage patterns among the college-educated and those with higher professional degrees,” Lundberg said.

“While marriage rates have declined consistently over time, they have declined far more among people whose education level is high school or some college.”

Also, college graduates tend to marry before they begin families and, when they do wed, their marriages are more stable than those of couples with less education. This puzzled Lundberg and Pollak.

The researchers hypothesized that now, in the 21st century, a primary function of marriage is to provide a long-term stable home for children, which suggests that investments in offspring have become a driving force in preserving the institution of matrimony.

Lundberg noted that mothers at all economic levels spend more time with their children now than was common 30 years ago.

“In terms of time and money, the well-educated, higher-income parents have increased their investments in children much more than those with lower incomes,” Lundberg said.

“They have the know-how and the resources and they expect to help their children become economically successful in a way that may seem out of reach for parents with much lower levels of resources.”

According to Lundberg, the playing field is not level and the focus for low-income parents is on keeping their children safe and healthy.

“When the joint project of intense investments in children seems out of reach, it may not seem worth putting up with the disadvantages of marriage,” Lundberg said.

“One possible implication if we are right — and I should say that this is a speculative argument — is that it may be possible to encourage investing in children among lower-income parents by devoting more social resources to early childhood, enabling parents to see a brighter future for their children,” Lundberg added.

“These societal investments could, in turn, make longer-term commitments among these parents more feasible and advantageous.”

One aspect of marriage that hasn’t changed much over the years is that most men and women eventually do marry.

“If you look at the fraction of people 50 years old who have ever married, the differences between the education groups are very, very small,” Lundberg said.

“What is really distinctive is the timing of marriage and the very high proportion of women with a high school diploma or some college who have their first child either on their own or within a cohabitating relationship, which is extremely rare among people with a college degree or higher.

“The timing is extraordinarily suggestive,” Lundberg concluded. “Almost everyone wants to get married eventually. The question is when, and do you wait until you get married before you have a child?”

Source: University of California, Santa Barbara/EurekAlert

Fragile Institute. Do the “snowflake generation” need marriage and family

- Forbes Woman

- Irina Tartakovskaya Author

July 8 is celebrated in Russia as the Day of Family, Love and Fidelity. How relevant is this holiday for the new generation? After all, representatives of generation Z are characterized as people who are tremulous, proud and do not tolerate any inconvenience. Forbes Woman - about the difficult fate of the institution of marriage in the 21st century

The future of the family institution is an issue that never ceases to worry politicians, religious figures, or ordinary people. Every time a new generation enters the conditional marriageable age, it begins to be discussed with renewed vigor: “And now, how will it be? Will the bonds hold, will demography rise, will some new forms of relations, incomprehensible and frightening, triumph? The full extent of all this anxiety - sociologists call it moral panic - is also present in today's agenda, when the focus is on the new young, the so-called generation z, to which the ironic label of "snowflakes" has already stuck. "Snowflakes", not without some reason, are considered to be very reverent, proud and not tolerant of any inconvenience. Of particular value to them is the preservation of personal boundaries, which they are ready to guard not only staunchly, but sometimes even passionately. The main confidant of the "snowflake" is usually considered not a boyfriend or girlfriend, and even more so not the parents, whom they are ready to present a serious bill for numerous childhood moral injuries, but a psychotherapist who helps them build warning signs along personal boundaries, a neutral zone, and sometimes even real fortifications.

"Snowflakes", not without some reason, are considered to be very reverent, proud and not tolerant of any inconvenience. Of particular value to them is the preservation of personal boundaries, which they are ready to guard not only staunchly, but sometimes even passionately. The main confidant of the "snowflake" is usually considered not a boyfriend or girlfriend, and even more so not the parents, whom they are ready to present a serious bill for numerous childhood moral injuries, but a psychotherapist who helps them build warning signs along personal boundaries, a neutral zone, and sometimes even real fortifications.

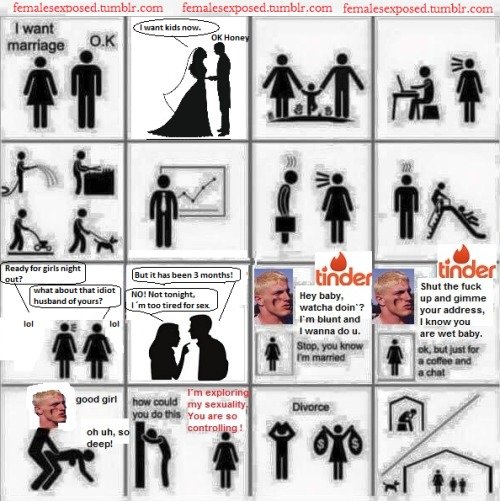

A reasonable question arises, how much such fragile creatures need marriage at all - a difficult, routine matter and certainly unfavorable for the protection of personal space? Moreover, when many gender queries can be easily satisfied with the help of Tinder and similar convenient services, civil marriage does not bother even the generation of their parents, and the sought-after term “polyamory” comes to high positions among search queries. Of course, many people love children, but the experience of the last few decades shows that marriage and children can be completely different stories, overlapping only partially, or not at all. And then, in fact, why, if not only a joint life in sorrow and joy, but also just a permanent relationship is perceived as a kind of burden?

Of course, many people love children, but the experience of the last few decades shows that marriage and children can be completely different stories, overlapping only partially, or not at all. And then, in fact, why, if not only a joint life in sorrow and joy, but also just a permanent relationship is perceived as a kind of burden?

However, modern family research tells us that things are not so simple. As sociologist Zhanna Chernova writes, in developed Western countries, the need for marriage and family relations has described a kind of parabola (this is such a curve in the form of the letter u, if someone suddenly doesn’t remember by chance): if in the middle of the 20th century marriage was still a very influential institution, implying relatively clearly defined gender roles (the man is the breadwinner of the family, the woman is the mother and “keeper of the hearth”), then in the second half of it, after the “sexual revolution” and the powerful gender and cultural changes that followed it, a certain crisis occurred: many women ( and men too, but above all women) the whole story ceased to suit. First of all, these changes related to educated middle-class women, who saw for themselves many other forms of self-realization and realized that they were quite capable of taking care of themselves, as a result, both the real marriage rate and the demand for “family values” decreased. , a lot of unremunerated homework and a bunch of other injustices. At that time, it seemed to many that marriage was really an obsolete form of relationship, demanded only by conservatives and poor people who simply couldn’t survive alone economically, let alone raise children.

First of all, these changes related to educated middle-class women, who saw for themselves many other forms of self-realization and realized that they were quite capable of taking care of themselves, as a result, both the real marriage rate and the demand for “family values” decreased. , a lot of unremunerated homework and a bunch of other injustices. At that time, it seemed to many that marriage was really an obsolete form of relationship, demanded only by conservatives and poor people who simply couldn’t survive alone economically, let alone raise children.

But in the first decades of the 21st century, everything suddenly changed: the demand curve for marital relations crept up again! It turned out that the family is not only about frustration and exploitation, that there are many very important emotional needs that are most conveniently satisfied in this form - in closeness, in support, in romance, finally ... The English sociologist Simon Duncan writes that back in The 1980s saw the reinvention of the "big Victorian white wedding" with lots of guests, bouquets, doves, cakes and more. “Instagram culture has given all these ventures a powerful new impetus.

“Instagram culture has given all these ventures a powerful new impetus.

However, do these new trends mean a return to traditional, conservative values? Social scientists say not at all, oddly enough. The fact is that these new desirable families no longer have such a strictly prescribed distribution of roles as traditional families: if earlier the duties of husband and wife were culturally prescribed, and those who could not cope with them or resisted them were subjected to significant moral pressure, then now any family union is largely an individual creation: each of its members has a much greater degree of freedom in determining what she or he would like to receive from him. And if something goes wrong, then it is not very difficult to get out of this cell of society ... An important point: we are talking now, of course, not about all modern people, but about educated middle-class youth from developed countries, where women, as as a rule, they already have enough social resources to live their lives independently, even with children. Moreover, such a parabola is still being built precisely and only for this successful social group: in low-resource groups, the institution of the family is still in a state of serious crisis.

Moreover, such a parabola is still being built precisely and only for this successful social group: in low-resource groups, the institution of the family is still in a state of serious crisis.

In this situation, the desired marriage no longer becomes the only possible scenario in life, but a kind of pleasure, a project that, if something happens, can always be closed. And from such positions it is already possible to agree on how and what will happen in this family, including the distribution of power and responsibilities. Thus, at the second end of the letter u, we again have a family, but this is a completely different family, with different rules of life, which may include the notorious respect for personal boundaries and other needs of the individual, and the mutual agreement of gender scenarios.

True, there is one significant nuance: we are still observing all these trends on the example of developed Western countries, in which over the past decades there have been significant changes not only in women's, but also in men's gender scenarios, i. e. for men, all these consequences women's emancipation of the twentieth century have become familiar. In Russia, by all appearances, this has not yet happened: men still do not understand well what their role is now and how modern masculinity should be expressed. That is why the divorce rate is so high and marriages are fragile: in 2018, there were 778 divorces per 1,000 marriages in Russia, and there are very few marriages themselves - only 6.2 per 1,000 inhabitants, and this is the lowest marriage rate since the beginning of the century. Male and female gender models do not mix well with each other and literally sparkle when they touch, many examples of which we can observe in any public discussions on gender. The still large gap between male and female life expectancy (10.2 years, and last year it began to grow again) is also to some extent the result of accumulated gender problems and family contradictions, due to which many men prefer to "live without a tower - fun and scary.

e. for men, all these consequences women's emancipation of the twentieth century have become familiar. In Russia, by all appearances, this has not yet happened: men still do not understand well what their role is now and how modern masculinity should be expressed. That is why the divorce rate is so high and marriages are fragile: in 2018, there were 778 divorces per 1,000 marriages in Russia, and there are very few marriages themselves - only 6.2 per 1,000 inhabitants, and this is the lowest marriage rate since the beginning of the century. Male and female gender models do not mix well with each other and literally sparkle when they touch, many examples of which we can observe in any public discussions on gender. The still large gap between male and female life expectancy (10.2 years, and last year it began to grow again) is also to some extent the result of accumulated gender problems and family contradictions, due to which many men prefer to "live without a tower - fun and scary.

The question of whether this new family model will become the norm in new generations, where all the rights and obligations of the participants will be discussed and observed, and household chores will be distributed fairly or at least to mutual satisfaction, remains open.

So all the hope is still on the “snowflakes”: maybe they won’t put pressure on each other so much anymore — they are so fragile after all… Bright Side

In recent years, more and more often one can hear the opinion that marriage and family in the classical sense of the word are becoming obsolete. Allegedly, we have become less likely to get married and get married, we are in no hurry to have children, and divorce statistics make us think about whether it is worth getting married at all.

We at ADME decided to find out what is happening with the family in the 21st century, how it has been transformed over the past decades, and what awaits the institution of marriage in the future.

The number of marriages is declining, but not in all countries

Today, the proportion of people getting married is declining in many countries. Moreover, according to studies, this does not depend on the welfare of the state - this trend is observed both in rich and poorer countries. For example, in the United States since 1972, the number of marriages has fallen by almost 50% and is now at an all-time low. Speaking about the reasons for this phenomenon, experts name the economic independence of women, gender equality, the disappointment of society in marriage as a whole, as well as unstable work and financial difficulties.

For example, in the United States since 1972, the number of marriages has fallen by almost 50% and is now at an all-time low. Speaking about the reasons for this phenomenon, experts name the economic independence of women, gender equality, the disappointment of society in marriage as a whole, as well as unstable work and financial difficulties.

However, the opposite trend is observed in some countries. For example, in China, Russia, and Bangladesh, marriage is more popular today than it was a couple of decades ago.

At the same time, although the number of official marriages has decreased in recent decades, at the same time the number of cohabitations has increased. That is, people prefer to live together, but are in no hurry to register their relationship.

We started families later

© Pexels

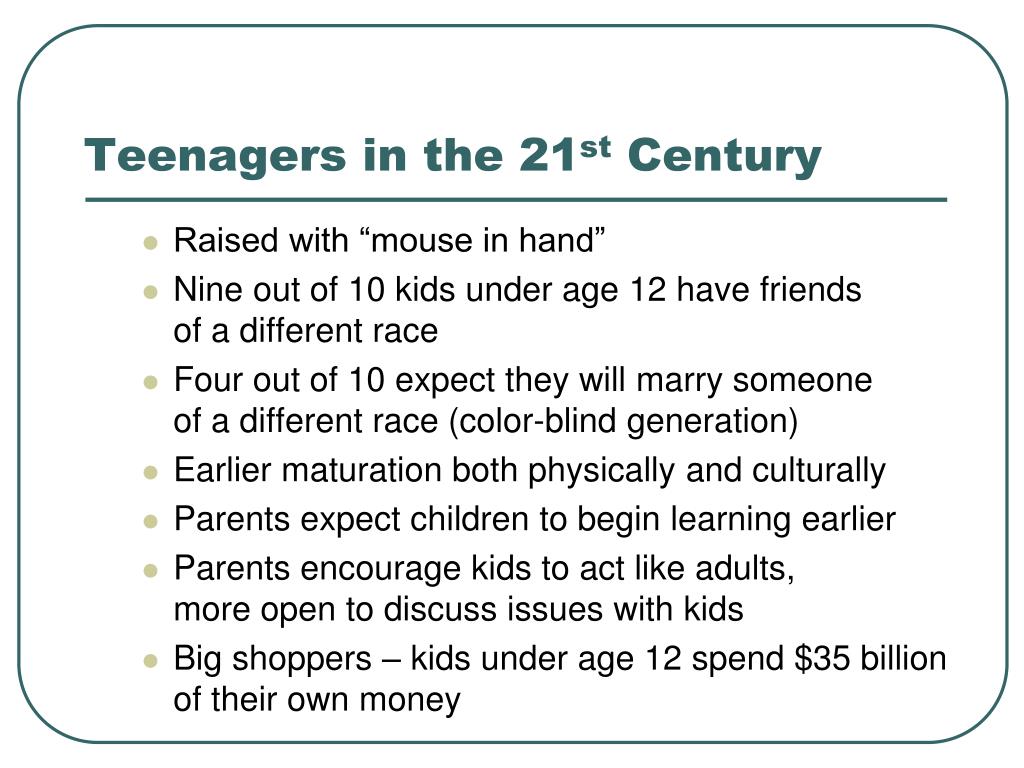

In the 21st century, in many countries, the decline in the number of weddings is accompanied by an increase in the age of marriage. This trend can be seen especially clearly in North America and Europe. For example, in Sweden, the average age of marriage for women increased from 28 years in 1990 to 34 years in 2017.

For example, in Sweden, the average age of marriage for women increased from 28 years in 1990 to 34 years in 2017.

Yes, of course, there are some countries where the average age of starting a family is still low and has remained unchanged for several years. However, in general, sociologists see a clear trend: people began to start families later and give birth to a child. This is probably due to the increase in life expectancy and the popularization of women's education.

In addition, it should be noted that now we are not so pressured by public opinion when it comes to the age until which it is necessary to get married. If earlier we could hear something like: “It’s time for you to get married, otherwise you’ll stay in the girls”, today the social norm has changed, and young people at 25 have completely different priorities.

Motherhood and marriage are now separated

© DALMAS / SIPA / SIPA / East News

It used to be like: a wedding, then a child. If for some reason this sequence was broken, the woman would inevitably catch sidelong glances at herself. Today, the proportion of children born out of wedlock has risen substantially in many countries. For example, in 1970, less than 10% of children were born out of wedlock, and in 2014 this number increased to 20% in some countries, and to half in some. The only exception is Japan, where motherhood and marriage are still tightly connected.

If for some reason this sequence was broken, the woman would inevitably catch sidelong glances at herself. Today, the proportion of children born out of wedlock has risen substantially in many countries. For example, in 1970, less than 10% of children were born out of wedlock, and in 2014 this number increased to 20% in some countries, and to half in some. The only exception is Japan, where motherhood and marriage are still tightly connected.

This does not necessarily mean single parents. As mentioned above, it’s just that in recent decades, it is cohabitation, and not marriage, that has become an increasingly common form of living together. At the same time, it does not mean at all that official marriages will disappear completely over time, it’s just that today many people prefer first live together, and then get married. This may result in unmarried couples having the same legal rights as married couples in the future. In any case, there is a demand from society for this.

We are no longer afraid of divorce

© olegparylyak / easyfotostock / East News, © Depositphotos.com

According to sociological research, the number of divorces is increasing all over the world. Scientists analyzed data from 84 countries of the world and came to the conclusion that the percentage of divorces has doubled in almost 40 years. And the statistics for the CIS countries and Russia are not at all rosy: about half of the couples break up. However, over the past decades, our attitude towards parting has changed and divorce has ceased to be something frightening. Previously, it was practically a disaster, especially for a woman: she instantly turned into a “persona non grata”, and today it is women who most often initiate divorces and are not afraid to be left alone. It should also be noted that in the modern world, expectations from a partner have become much higher than they were before. We want not just a reliable person who will help us in everyday life and financially, we also expect that it will be interesting with him, that he will develop and become our best friend. Preferably with a good sense of humor.

Preferably with a good sense of humor.

An interesting fact: there is a study according to which the happy outcome of a marriage directly depends on how much was spent on the wedding. And the more luxurious the celebration, the greater the likelihood of a divorce.

Monogamy vs serial monogamy

© ASSOCIATED PRESS / East News, © Depositphotos.com

Some experts say the average marriage today lasts 5-7 years. This is the period that is necessary in order to raise a joint child to his feet. Still, it should not be denied that one of the main reasons for marriage is the desire to have a child. So, while he is small, his parents have a good reason to live together, and then, when he reaches the age of social maturity, many begin to look for other relationships.

Sociologists even have a special term for this - "serial monogamy". That is, before the norm was just monogamy - the union of two people who promised to be faithful to each other. Today, once-in-a-lifetime marriages have become rare, so we see the dominance of serial monogamy. This is a model of relationships when 90,041 people enter into several monogamous unions in their life, but at the same time remain faithful in them. In other words, we still want fidelity in relationships and in the family, but not for the rest of our lives. One of the reasons for this phenomenon was the increased life expectancy. That is, even if people get married at 30, it is not so easy to live together for most of their lives up to 70 years. In 40 years, everything can change dramatically: goals, aspirations, desires. It's not good or bad, it's just a given. In the 21st century, it is becoming increasingly difficult for us to maintain a marriage union for life.

Today, once-in-a-lifetime marriages have become rare, so we see the dominance of serial monogamy. This is a model of relationships when 90,041 people enter into several monogamous unions in their life, but at the same time remain faithful in them. In other words, we still want fidelity in relationships and in the family, but not for the rest of our lives. One of the reasons for this phenomenon was the increased life expectancy. That is, even if people get married at 30, it is not so easy to live together for most of their lives up to 70 years. In 40 years, everything can change dramatically: goals, aspirations, desires. It's not good or bad, it's just a given. In the 21st century, it is becoming increasingly difficult for us to maintain a marriage union for life.

Loners as the main threat to the family

©Depositphotos.com, ©Pexels

Some experts believe that the main achievement of the social revolution of the 21st century is the ability to live alone, without a partner. The institution of the family is influenced in one way or another by new economic realities. A modern city dweller (whether male or female) can comfortably live alone. He is free from various obligations, free to spend time with friends, travel, build a career, spend money only on himself. And such an opportunity appeared for the first time in the entire time of the existence of mankind, because Previously, marriage unions were created precisely in order to survive .

The institution of the family is influenced in one way or another by new economic realities. A modern city dweller (whether male or female) can comfortably live alone. He is free from various obligations, free to spend time with friends, travel, build a career, spend money only on himself. And such an opportunity appeared for the first time in the entire time of the existence of mankind, because Previously, marriage unions were created precisely in order to survive .

So it is quite likely that in the new realities, single households, or single households, will become the main alternative to the family. True, sociologists note that so far there is one thing that is still quite difficult to handle alone - raising a child. It is difficult both from a material and psychological point of view. Although, perhaps, when the practice of providing an unconditional basic income to all citizens spreads in developed countries, this problem will also disappear. An unconditional basic income is a social concept where the government pays a certain amount of money on a regular basis to every citizen, regardless of their income level and without having to do any work.

The return of the non-nuclear family

© Zenon Zyburtowicz / East News

Sociologists call the return of the non-nuclear family, that is, the extended family, another important transformation of society. More recently, the main type of family was nuclear - mom, dad and child. Today, everything turns out to be much more complicated: as people began to divorce and start new families, they find themselves inside a distributed network of relationships . Imagine you have a child from a previous marriage, and your partner also, then you have a common baby - you get an extended family. Add to this grandparents who want to communicate with their grandchildren, regardless of whether you broke up with your partner or not.

Also, some experts note that a modern person's inner circle includes not only relatives, but also friends who can help in difficult times and provide the necessary support. Moreover, thanks to technological progress, we have more and more such ties.