Separation anxiety disorder treatment

Separation Anxiety Disorder | Boston Children's Hospital

Listen

As a parent, it can be heartbreaking to watch your child becoming distressed and worried about being separated from you. When this distress is ongoing and disruptive to your child’s (as well as your family’s) life, it is likely to be separation anxiety disorder. Separation anxiety disorder (SAD) is an anxiety disorder that causes a child to suffer from feelings of extreme worry when apart from family members or other places and people she is attached to. Sometimes just the thought of the separation causes this intense worry.

Children with SAD may experience:

- difficulty being away from parents or other loved ones

- excessive worry about harm to loved ones

- excessive worry about danger to self

- difficulty leaving the house, even to go to school

- difficulty sleeping

- feeling physically ill when away from loved ones

In order to diagnose SAD, these symptoms must be present for at least four weeks and be more severe than the normal separation anxiety that most children experience.

Treatment for separation anxiety disorder usually includes therapy, medication, or a combination of both. The most common form of therapy used to treat separation anxiety disorder is called cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT involves helping children and parents to learn ways to change unhelpful thoughts and behaviors. Therapists can help parents to understand how their behavior may increase their child’s anxiety (for example, allowing their child to skip school). It is very important to seek out medical advice if you are concerned that your child has separation anxiety disorder, because if left untreated, anxieties can grow bigger.

Who is affected by separation anxiety disorder?

About 4 percent of younger children have SAD, while the estimate for adolescents is slightly lower. Girls are affected more often than boys.

How common are anxiety disorders?

Anxiety disorders are among the most common mental, emotional, and behavioral problems affecting children. About 13 out of every 100 children ages 9 to 17 years old experience some kind of anxiety disorder, such as separation anxiety disorder. Approximately 4 percent of children suffer from separation anxiety disorder.

About 13 out of every 100 children ages 9 to 17 years old experience some kind of anxiety disorder, such as separation anxiety disorder. Approximately 4 percent of children suffer from separation anxiety disorder.

Separation Anxiety Disorder | Symptoms & Causes

What are the symptoms of separation anxiety disorder?

Children with SAD can’t just “put their worries aside” no matter how hard they try. They feel much more anxious, and for a much longer period of time, than other children in the same situations.

Common fears experienced by children with SAD Include:

- worry about separation

- worry about death or harm to a loved one

- worry about something bad happening to herself

- worry about being alone

- worry about sleep and nightmares

The consistent factor in any worry associated with SAD is that the child’s fear is unrealistic. What she fears will happen is very unlikely to happen.

What she fears will happen is very unlikely to happen.

Physical symptoms usually occur when there is a separation or anticipated separation. They may include:

- nausea and vomiting

- quick breathing or difficulty catching one’s breath

- muscle aches (especially stomach and headaches)

- fatigue

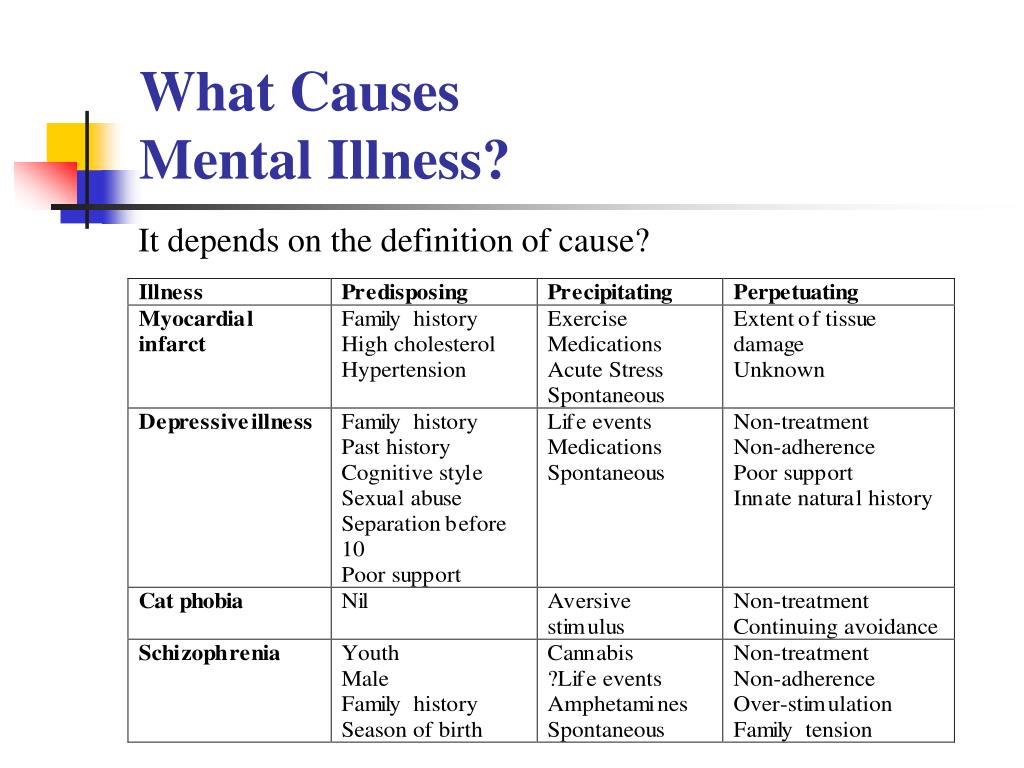

What causes separation anxiety disorder?

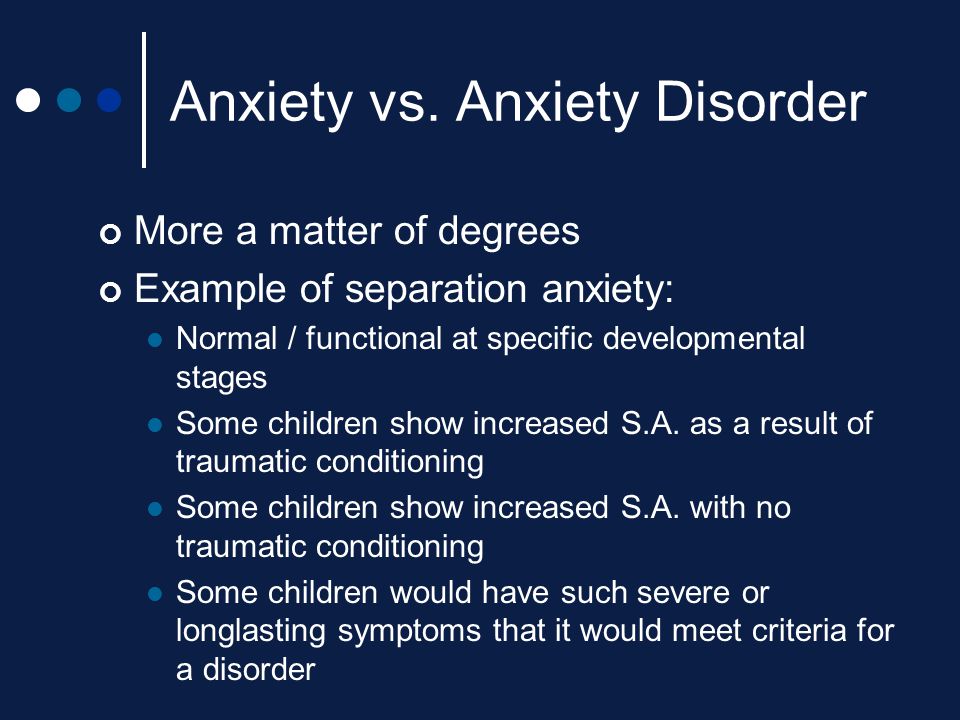

Nearly all children experience brief feelings of anxiety about being away from a parent and display clingy behavior. Typically these normal bouts occur when a child is between 18 months and 3 years old, although older children can have passing feelings of separation anxiety during times of stress. The difference between these normal feelings of anxiety and a disorder like SAD is that a child with separation anxiety disorder will experience an extended and extensive period of fear and distress about being apart from familiar people and places and the degree of anxiety or fear is notably out of proportion to the reality of the situation. Anxiety disorders like SAD are linked to biological, family and environmental factors.

Anxiety disorders like SAD are linked to biological, family and environmental factors.

- Biological factors: The brain has special chemicals, called neurotransmitters, that send messages back and forth to control the way a person feels. Serotonin and dopamine are two important neurotransmitters that, when “out of whack,” can cause feelings of anxiety.

- Family factors: Just as a child can inherit a parent’s hair color, a child can also inherit that parent’s anxiety. In addition, anxiety may be learned from family members and others who are noticeably stressed or anxious around a child. Parents can also contribute to their child’s anxiety without realizing it by the way they respond to their child. For example, allowing a child to miss school when they are anxious about going likely causes the child to feel more anxious the next school day.

- Environmental factors: A traumatic experience (such as a divorce, illness, or death in the family) may also trigger the onset of separation anxiety disorder.

Separation Anxiety Disorder | Diagnosis & Treatments

How is separation anxiety disorder diagnosed?

A child may be diagnosed with separation anxiety disorder if symptoms:

- are present for at least six months

- cause significant distress for the child

- do not go away, no matter how much the child tries to relax or stop worrying

- impair functioning at home, at school, or with peers

If my child is diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, what happens next?

The clinician who evaluates your child will make recommendations for treatment. These may include: parent guidance, especially around keeping the child involved in her activities, child therapy, and, sometimes, anti-anxiety medication.

How do we treat SAD?

Treatment for separation anxiety disorders vary from child to child, and your child’s therapist will work with you to determine the best approach for your child’s symptoms and circumstances. Treatment may include parent guidance, therapy, and/or medication.

Treatment may include parent guidance, therapy, and/or medication.

Psychotherapy, with parent and child involved, is an effective method of overcoming the disproportionate anxiety that is the calling card of SAD. An experienced mental health professional uses therapy to help your child practice healthy responses to anxiety, replacing the damaging practices of worry and avoidance learned before. Therapy sessions help you and your child:

- how to recognize and vocalize worry and fear

- techniques (such as breathing and imaging a relaxing scene) to reduce physical symptoms of anxiety

- new thought patterns to replace the destructive ones; instead of a worry thought the child can remember “I will be okay. I did it before, I can do it again"

- to approach feared situations in steps so that the child is practicing and experiencing success when separated from her parents.

There are many different medications used to help control anxiety. A prescribing clinician (psychiatrist or nurse practitioner) will choose a medication if needed that will work best to help your child.

What is the long-term outlook for a child with a separation anxiety disorder?

With proper treatment, the majority of children diagnosed with separation anxiety disorder experience a reduction or elimination of symptoms. Symptoms of SAD can recur when new developmental challenges emerge. When treatment is started early and involves the parent as well as the child, the child’s chance of recovery without multiple recurrences improves.

Separation Anxiety Disorder | FAQ

How can I tell if my child has separation anxiety disorder?

All kids experience some separation anxiety. For infants and toddlers it is a normal stage of development that's connected to developing an attachment to parents and other caregivers. In older children, certain separation fears and worries are typical for their age. For example, let’s say your child is starting his first day of kindergarten. He is likely to show some anxiety and discomfort when getting up and ready for school and going into the school for the first time. He may even cry when he comes home and say he wants to stay home and not return to school. If this period of anxiety is minor (he is comforted by reassurance), lasts only a few days, and is replaced by a return to his normal mood and activities, this is probably normal separation anxiety. However, if your child remains significantly distressed about being away from you during the school day (to the point where he is physically ill, can’t focus, isn’t soothed, and is disrupted in other activities), this may be separation anxiety disorder.

He is likely to show some anxiety and discomfort when getting up and ready for school and going into the school for the first time. He may even cry when he comes home and say he wants to stay home and not return to school. If this period of anxiety is minor (he is comforted by reassurance), lasts only a few days, and is replaced by a return to his normal mood and activities, this is probably normal separation anxiety. However, if your child remains significantly distressed about being away from you during the school day (to the point where he is physically ill, can’t focus, isn’t soothed, and is disrupted in other activities), this may be separation anxiety disorder.

What is the difference between separation anxiety disorder in children and in adults?

Separation anxiety disorder is uncommon in adults. With anxiety in general, children usually don’t realize how intense or abnormal their feelings of anxiety have become. It can be difficult for a child to know that something is “wrong. ”

”

How can I prevent separation anxiety disorder?

While anxiety disorders cannot be prevented altogether, seeking treatment as soon as you notice that your child has a problem can reduce the severity of the problem and improve your child’s quality of life. Some other tips include:

- Stay calm in front of your child, as she often looks to you for how to react in new and uncertain situations.

- Avoid providing an excessive amount of reassurance since this may signal more, not less, to worry about.

- Teach your child how to problem solve, cope, and reassure herself.

- Limit the avoidance of activities. Though avoidance may temporarily reduce distress, it will allow the anxiety to grow and make things more difficult for your child in the future.

- Provide support and praise for small victories in separation rather than consequences for the difficulties, since consequences tend to increase anxiety.

Where can I go to learn more about separation anxiety disorder?

Please note that neither Boston Children’s Hospital nor the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences unreservedly endorses all of the information found at the sites below. These links are provided as a resource.

These links are provided as a resource.

- Anxiety Disorders Association of America (ADAA)

- Anxiety Disorders Resource Center

Separation Anxiety Disorder | Programs & Services

Departments

Programs

Separation Anxiety Disorder | Contact Us

Separation Anxiety Disorder in Children: A Quick Guide

What is separation anxiety disorder?

Separation anxiety disorder is a mental health disorder that causes children to become extremely upset when they are separated from parents or caregivers. They worry that something bad will happen to their parents during the separation. It’s normal for young kids to have some trouble separating, but this anxiety is more extreme. With separation anxiety disorder, fear and anxiety get in the way of normal life, like going to school or to playdates.

Symptoms of separation anxiety disorder usually show up in preschool and early elementary school. In rare cases it can show up later, like when a child starts middle school.

What are the symptoms of separation anxiety disorder?

The anxiety that children with separation anxiety disorder feel is much more than what is normal for their age.

Signs that a child might have separation anxiety disorder include:

- Problems saying goodbye to parents

- Fear that something bad will happen to a family member during separation

- Tantrums when they have to leave parents or caregivers

- Overwhelming need to know where parents are, and be in touch with them by phone or texting

- Constantly following one parent around the house

- Nightmares about bad things happening to family members

- Physical symptoms like stomachaches, headaches and dizziness

- Refusing to go to school or on playdates

Younger children are mostly anxious at the time of separation. Older kids get anxious when they think about an upcoming separation.

Older kids get anxious when they think about an upcoming separation.

How is separation anxiety disorder diagnosed?

A diagnosis of separation anxiety requires anxiety at being separated from parents or caregivers that is beyond what is considered normal for a child’s age. The symptoms have to show up most of the time for at least four weeks and cause serious problems in the child’s daily life.

How is separation anxiety disorder treated?

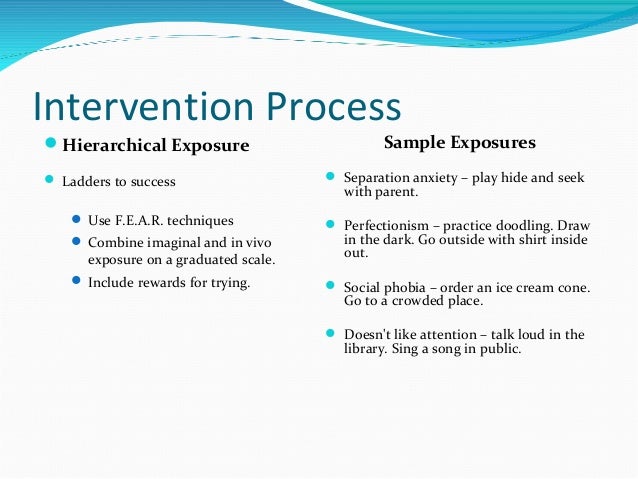

Treatment for separation anxiety disorder usually involves cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT. This is a treatment that helps children learn to understand and manage their fears. Exposure therapy, a specialized form of CBT, might also be used. Exposure therapy works by carefully exposing children to separation in small doses. This can help them feel less anxious over time.

When therapy is not enough, a child may be given medicine to lessen their symptoms and help make therapy more effective. The most common drug to treat separation anxiety disorder is an antidepressant medication called an SSRI. Occasionally anti-anxiety medications are used but they can be habit-forming.

The most common drug to treat separation anxiety disorder is an antidepressant medication called an SSRI. Occasionally anti-anxiety medications are used but they can be habit-forming.

This guide was last reviewed or updated on February 23, 2023.

Adult Separation Anxiety Disorder - New Diagnostic Category

Adult Separation Anxiety Disorder - New Diagnostic Category Website of the publishing house "Media Sfera"

contains materials intended exclusively for healthcare professionals. By closing this message, you confirm that you are a registered medical professional or student of a medical educational institution.

Avedisova A.S.

State Scientific Center for Social and Forensic Psychiatry. V.P. Serbsky, Moscow

Arkusha I.A.

Federal State Budgetary Institution "Federal Medical Research Center for Psychiatry and Narcology named after N.N. V.P. Serbsky" of the Ministry of Health of Russia, Moscow, Russia

Zakharova K. V.

V.

Separation anxiety disorder in adults - a new diagnostic category

Authors:

Avedisova A.S., Arkusha I.A., Zakharova K.V.

More about the authors

Magazine: Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakov. 2018;118(10): 66-75

DOI: 10.17116/jnevro201811810166

How to quote:

Avedisova A.S., Arkusha I.A., Zakharova K.V. Separation anxiety disorder in adults is a new diagnostic category. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakov. 2018;118(10):66-75.

Avedisova AS, Arkusha IA, Zakharova KV. Separation anxiety disorder in adults is a new diagnostic category. Zhurnal Nevrologii i Psikhiatrii imeni S.S. Korsakova. 2018;118(10):66-75. (In Russ.)

https://doi.org/10.17116/jnevro201811810166

Read metadata

The review presents a new diagnostic category — separation anxiety disorder (ADD) in adults and its position in modern diagnostic systematics. As in children, in these cases we are talking about the development of inadequate anxiety and fear about real or imagined separation from the object of affection (parents, loved one, etc.). In separate sections of the review, the epidemiology of ARS, data regarding the etiology and pathogenesis, personal prerequisites for the development of ARS in adults, diagnosis and diagnostic tools, comorbidity of ARS with other anxiety disorders, and therapy are considered. The need for further study of HRS in adults in all of the above aspects, especially in relation to treatment, is emphasized.

As in children, in these cases we are talking about the development of inadequate anxiety and fear about real or imagined separation from the object of affection (parents, loved one, etc.). In separate sections of the review, the epidemiology of ARS, data regarding the etiology and pathogenesis, personal prerequisites for the development of ARS in adults, diagnosis and diagnostic tools, comorbidity of ARS with other anxiety disorders, and therapy are considered. The need for further study of HRS in adults in all of the above aspects, especially in relation to treatment, is emphasized.

Keywords:

separation anxiety

separation anxiety disorder

age features

Authors:

Avedisova A.S.

State Scientific Center for Social and Forensic Psychiatry. V.P. Serbsky, Moscow

Arkusha I.A.

Federal State Budgetary Institution "Federal Medical Research Center for Psychiatry and Narcology named after N.N. V.P. Serbsky" of the Ministry of Health of Russia, Moscow, Russia

Zakharova K. V.

V.

Close metadata

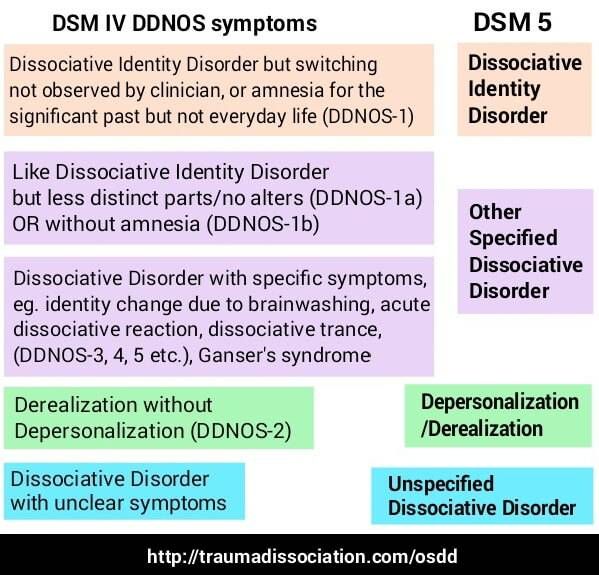

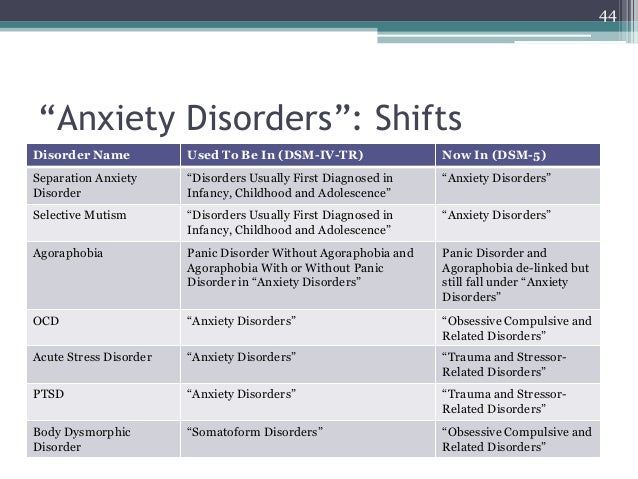

Separation Anxiety Disorder (TSD) is characterized by the presence of inappropriate and excessive fear or anxiety about real or imagined separation from the object of attachment. ASD has traditionally been considered in the ICD-10 and DSM-IV diagnostic rubrics as a disorder characteristic of childhood, separation anxiety disorder (AD) in children [1, 2]. In foreign literature, it is actively studied in the psychological and medical aspects [3-7], while in the domestic literature it is rarely discussed in the works of doctors and is more often the subject of psychological scientific research [8-17], being considered in the context of parent-child relationships (often with psychoanalytic positions).

Large-scale epidemiological studies conducted in recent years on the phenomenon of separation anxiety (TS) revealed an unexpectedly high prevalence of it in adults, often occurring for the first time in persons over 18 years of age. These data served as a stimulus for changing the positioning of TRS in various diagnostic manuals. In the latest edition of the DSM-5, TD is included in the broad group of TD, and its diagnosis no longer depends on the age of onset of the disease, covering the variation of symptoms throughout the life cycle [18]. This change represents a significant departure from the conceptualization of ASD in previous editions of the DSM, where the diagnosis was limited to a disorder first diagnosed in infancy, childhood, or adolescence, from onset of symptoms until age 18 (in persons over 18 years of age, this diagnosis could only be made retrospectively if its symptoms have been observed since childhood). ADHD without age is also considered in the draft International Classification of Diseases 11th revision (ICD-11) under the heading "Anxiety and fear-related disorders" [19].

In the latest edition of the DSM-5, TD is included in the broad group of TD, and its diagnosis no longer depends on the age of onset of the disease, covering the variation of symptoms throughout the life cycle [18]. This change represents a significant departure from the conceptualization of ASD in previous editions of the DSM, where the diagnosis was limited to a disorder first diagnosed in infancy, childhood, or adolescence, from onset of symptoms until age 18 (in persons over 18 years of age, this diagnosis could only be made retrospectively if its symptoms have been observed since childhood). ADHD without age is also considered in the draft International Classification of Diseases 11th revision (ICD-11) under the heading "Anxiety and fear-related disorders" [19].

TMS in adults was first described in the 90s of the last century by V. Manicavasagar and D. Silove [20]. Subsequently, several empirical studies have shown a high prevalence of TS in adult patients [3, 5, 6, 21], a significant level of dysfunction in such patients [6], a high comorbidity of TMS with anxiety and affective disorders [22–24], and also the insufficient response of such patients to the traditionally used treatment for the relief of other anxiety conditions [25].

Epidemiology of TRS

The prevalence of HRS among children and adolescents is 3–5%, with a peak at 7–9 years of age and a subsequent decrease in these values [26, 27]. Data from recent epidemiological studies conducted in the adult population disproved the notion of a decrease in the prevalence of HRS with age. According to the results of the National Questionnaire Comorbidity Study (NCS-R), conducted in the United States in 2001–2013, the prevalence of TRS is 4.1% in the pediatric population and 6.6% in the adult population [6]. Another transnational study (World Mental Health Surveys), which included 38,993 adults from 18 WHO countries showed that the lifetime prevalence of TMS is 4.8% on average, with 43.1% of cases manifesting over the age of 18 years [28]. A feature of this epidemiological study was the use of an expanded definition of TRS, which suggests the possibility of the primary onset of this disorder in adulthood without a history of equivalent conditions in childhood. At the same time, according to different authors, 1/3—¼ of cases of TRS manifest for the first time in adulthood [3, 24].

At the same time, according to different authors, 1/3—¼ of cases of TRS manifest for the first time in adulthood [3, 24].

The range of average age of patients at the onset of TRS in adults is quite wide. So, the average age of manifestation of the disorder in adulthood, according to S. Pini et al. [29], was 23.1±11.5 years and 8.3±8.1 years with the first manifestations in childhood [29]. Similar results were obtained by K. Shear et al. [6]. They reported that in most cases of adult TRS, the first manifestations of the disease occurred in late adolescence or age ≥20, while in adults with childhood-onset TRS, the first manifestations of the disease occurred during early childhood or early school age. At the same time, the underestimation of the prevalence of TRS in adults with onset in childhood is emphasized: in 1/3 of persons with TRS in childhood (36.1%), the disorder persists into adulthood, although it is classified as having first begun in adulthood (77.5%) .

In contrast to the prevalence of females in childhood TRS (odds ratio — OR = 2. 2), in the adult population, gender differences are smoothed out and more often the disease begins in adulthood in men [6, 24].

2), in the adult population, gender differences are smoothed out and more often the disease begins in adulthood in men [6, 24].

Etiology and pathogenesis of TRS

Mechanisms for the onset of ASD include genetic and environmental components. The study of comorbid TRS disorders in adults provides some insight into possible environmental risk factors for the development of this disorder. For example, trauma and associated fear for personal safety predetermine the “overlap” between TRS in adults and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [30], and distress in the form of loss of a loved one, death, divorce, etc. determines the correlation of TRS with complicated grief reaction [31].

Parenting styles can be assessed as another environmental risk factor for developing ASD in adults. Among them are considered parental overprotection [32], intrusiveness [33], maternal overinvolvement [34], which, as a rule, are associated with certain critical life periods - moving from the parental home, the first serious romantic relationship, the birth of children, etc. Even increasing independence children in adolescence, according to E. Hock et al. [35], is a possible risk factor for the development of TRS in their parents.

Even increasing independence children in adolescence, according to E. Hock et al. [35], is a possible risk factor for the development of TRS in their parents.

Estimates of heritability suggest that the contribution of genetic factors to the development of early onset TMS is more significant than the influence of environmental factors [36]. Genetic studies related to ASD are few and are based mainly on the hypothesis of D. Klein [37], according to which there is a common genetically determined neurophysiological vulnerability underlying ASD and panic disorder (PD), which predetermines their “overlap” [38] . So, the general determinants between retrospectively assessed children's TMS and PR, according to M. Battaglia et al. [39], explain 89% of their genetic variance. To such a vulnerability, O. Atli et al. [40] refer to hypersensitivity to inhaled carbon dioxide CO 2 . In a study by R. Roberson-Nay et al. [41] and A. Ogliari et al. [2] found an association of both disorders with hypersensitivity to CO 2 , which, in their opinion, explains the association of TMS with PR in children and adults. Twin studies [36,42–44] of ARS have found higher lifetime prevalence and concordance rates (especially in females) in monozygotic twins than in dizygotic twins.

Twin studies [36,42–44] of ARS have found higher lifetime prevalence and concordance rates (especially in females) in monozygotic twins than in dizygotic twins.

In the context of the search for a biological marker of TRS in adults, it is of interest to study the density of the platelet transport protein TSPO (18 kDa translocator protein) or the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor (PBR), which plays an important role in the biosynthesis of steroids during periods of stress and anxiety [45 ]. Subpopulations of adult patients with panic, depressive and bipolar disorders have been found to have low TSPO densities, and they are more reduced when these disorders are comorbid with TMS in adults [46–48]. B. Costa et al. [49] suggest that low levels of TSPO expression in adult HRS alter the synthesis of pregnenolone (the first metabolite in the steroidogenesis chain), and as a result of influencing processes in the CNS, this leads to a decrease in the level of neurosteroids with anxiolytic activity, creating a neuroendocrine imbalance.

A promising area of research on ASD in adults is the study of the role of oxytocin and cortisol. It is known that oxytocin determines social behavior, participates in the formation of romantic attachment [50], trust and empathy [51, 52], plays a role in the upbringing of a person, contributing to the establishment of parent-child and marital ties [53]. Peripheral oxytocin levels have been suggested to be potential markers of social sensitivity and attachment capacity [54]. Through interaction with other biological systems, oxytocin can modulate biological stress responses, such as increased release of cortisol (a steroidal glucocorticoid hormone — a biomarker of stress responses) and cytokines, and thus is associated with stress-related psychological disorders [55]. Thus, when studying the levels of oxytocin in plasma and cortisol in saliva in healthy students who do not have romantic relationships, data were obtained on the correlation of oxytocin concentration with attachment to parents and on feedback with depressive symptoms, and high levels of plasma cortisol are associated with anxiety [56 ]. However, the analysis of mutations in the promoter and coding regions of the oxytocin gene did not reveal any abnormalities in patients with TMS in adults [57].

However, the analysis of mutations in the promoter and coding regions of the oxytocin gene did not reveal any abnormalities in patients with TMS in adults [57].

Another attempt to study the neurobiological features of adult TRS was the work of R. Redlich [58] and D. Griffin and K. Bartholomew [59], performed by modern tomography methods. They found an increase in the volume of gray matter in the amygdala, its hypersensitivity to negative social stimuli, and its connection with the occipital and somatosensory regions, which modulate attention and emotional significance, which leads to increased attention to social cues. The results obtained confirm the data of earlier studies on the association of separation with an increase in the activity of the amygdala in adolescents [60], as well as with an increase in the functional connection of the amygdala with the prefrontal and occipital regions [61, 62]. However, amygdala reactivity to negative stimuli has also been observed in individuals with subclinical anxiety and depression [63], as well as in social TR, specific phobias, and generalized social phobia [64, 65], suggesting the existence of a common neurophysiological mechanism and neuroanatomical substrate of anxiety states.

Personality causes of TRS in adults

Literature on the personality preconditions for ASD in adults is sparse, but quite convincingly indicates an association with neuroticism and its correlates (insecure attachment, low self-esteem, uncertainty intolerance) [66].

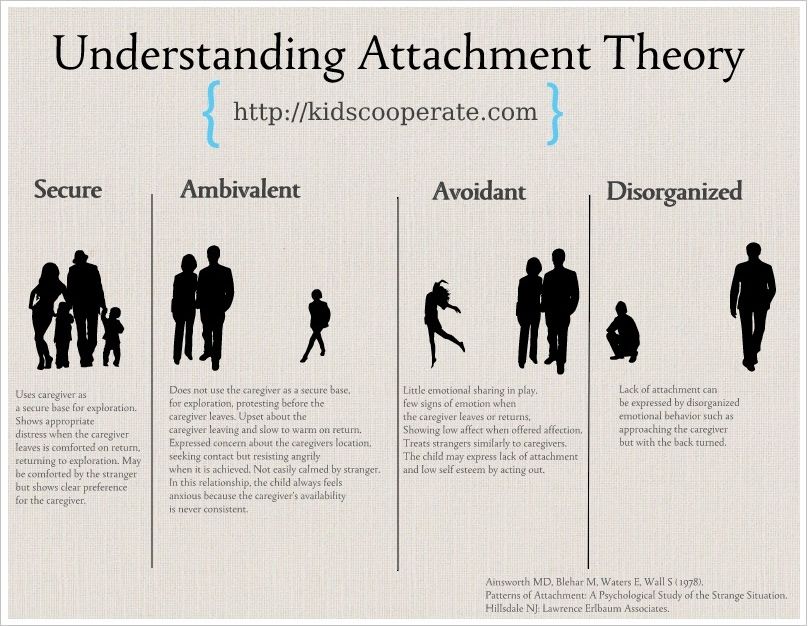

According to J. Bowlby's theory of attachment [67–69], early parent-child bonds play an important role in developing working models of close interpersonal relationships in which separation anxiety and fear of attachment are the driving force behind attachment formation, creating a template for enduring attachment styles: secure (reliable) and insecure (anxious-resisting/ambivalent, avoidant, disorganized). At the same time, adults with insecure attachment styles, which form when a significant person is under threat or unavailable, are prone to hypervigilance (increased vigilance) in interpersonal interactions, are sensitive to losses or the threat of breaking close relationships, which, in turn, predisposes to the formation anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Studying attachment styles in adult PD patients with and without adult ASD, V. Manicavisigar et al. [70] found that patients with ASD score higher in the Adult Attachment questionnaire due to the Need for Approval and Preoccupation with Relationship subscale. This led them to speculate that adult ASD might be related to their anxious attachment style.

In the context of the formation of insecure attachment styles, maternal ST is actively considered as a stable characteristic [71] associated with less mature self-awareness (as it can happen in adolescent mothers) [72], negative self-image [73], low self-esteem [74] , negative childhood memories of their own upbringing, rejection and infringement of independence [75]. Mothers with high levels of TS are more likely to exhibit more intrusive and autonomy-limiting behavior towards their children, which may lead to the perpetuation of insecure attachment in the family [74, 76, 77].

In addition to insecure attachment, another personality variable, neuroticism, is considered in the context of the occurrence of ASD in adults, as well as other anxiety and depressive disorders [78]. It has been shown that the level of neuroticism in patients with ASD and social phobia is higher than in patients with other ASDs [24]. The authors suggest that the early age of onset of SAD or social phobia is a reflection of hereditary vulnerability, increasing the general tendency towards anxiety and insecurity throughout life.

It has been shown that the level of neuroticism in patients with ASD and social phobia is higher than in patients with other ASDs [24]. The authors suggest that the early age of onset of SAD or social phobia is a reflection of hereditary vulnerability, increasing the general tendency towards anxiety and insecurity throughout life.

Both personality variables, insecure attachment and neuroticism, are associated with such personal characteristics as uncertainty intolerance (UH) [79-81]. We are talking about "cognitive bias or a negative reaction to situations of uncertainty and ambiguity" [82, 83]. To some extent HH can be seen as an integral part of the relationship that characterizes attachment. For example, people may experience uncertainty about how they will function in the absence of an attachment figure. Considering N.N. as a transdiagnostic factor of vulnerability to the occurrence and chronification of anxiety and depressive disorders, G. Ruggiero et al. [84] emphasize that its specificity in TS is determined only in the complex of assessments of other personality variables - neuroticism and anxious or avoidant attachment. Thus, J. Hirsh and M. Inzlicht [80] draw attention to the fact that neuroticism enhances the effect of HH on emotional stress, and S. Bőgels et al. [15] emphasize that HH, interacting with anxious attachment, contributes to the development of TRS in adults.

Thus, J. Hirsh and M. Inzlicht [80] draw attention to the fact that neuroticism enhances the effect of HH on emotional stress, and S. Bőgels et al. [15] emphasize that HH, interacting with anxious attachment, contributes to the development of TRS in adults.

Diagnosis of TRS in adults

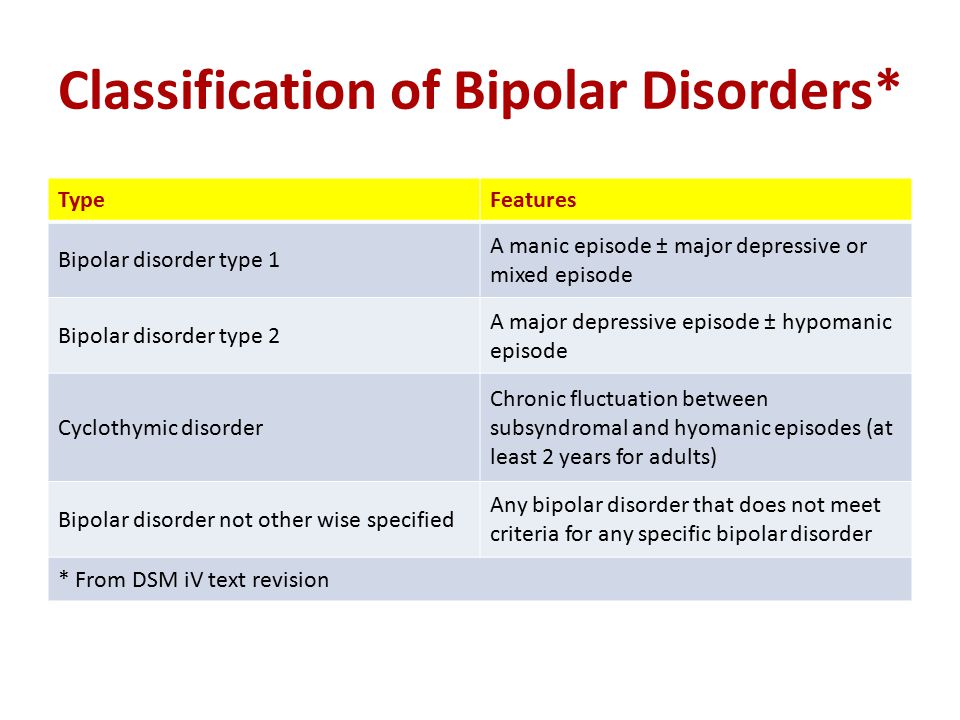

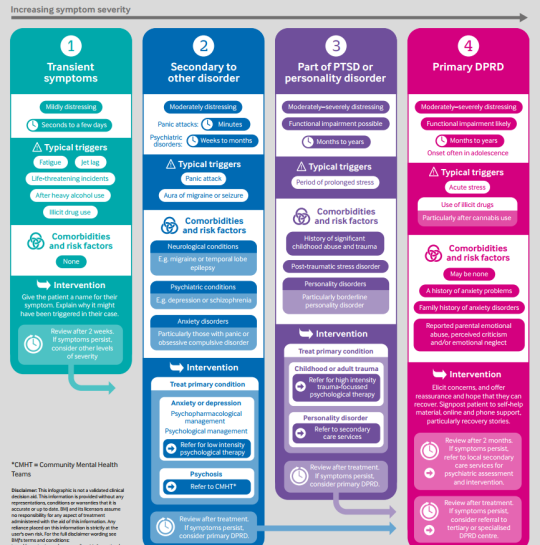

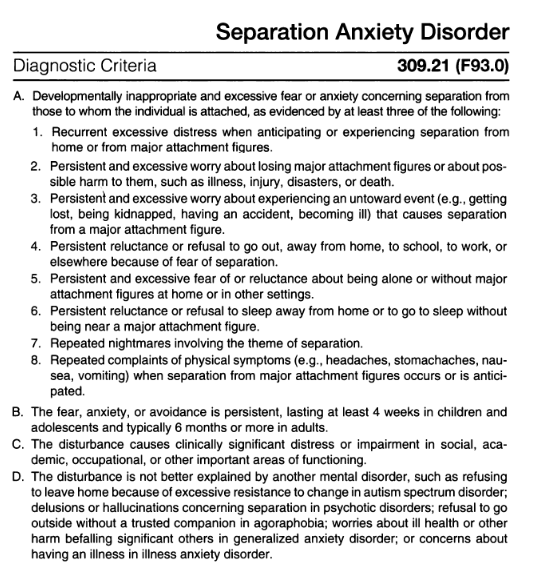

In the domestic version of the ICD-10, separation anxiety disorder (SAD) is presented in the section “Emotional and behavioral disorders beginning in childhood and adolescence” (heading F93.0) (Table 1)

Table 1. Diagnostic criteria for SAD in childhood according to ICD-10 and TRS according to DSM-5 1 . To make a diagnosis, at least 3 signs of criterion “A” must be met: mandatory onset before the age of six, duration of at least 4 weeks, exclusion of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and the inability to explain the existing symptoms by any other disorder [85]. In DSM-5 TRS (section 309.21), included in the TS section, requires the presence of at least 3 criteria "A" symptoms for diagnosis, lasting at least 4 weeks in childhood and 6 months or more in adults, causing clinically significant distress and impaired functioning and not explained by others mental disorders [18]. The DSM-5 also allows for a narrower TRS duration criterion, which for adults should be used as a “general guideline with some degree of flexibility”. The list of symptoms that meet criterion "A" in both classifications is almost identical and includes recurring excessive anxiety at actual and expected separation from the main figures of attachment, as well as constant worry about possible harm to oneself or the object of affection, or the occurrence of an adverse event (abduction, illness, death, etc.), which can lead to separation or loss of a significant figure. Individuals with ASD may be afraid or avoid staying at home or other places alone, refusing to leave the house or sleeping away from home because of separation anxiety. They may experience separation nightmares and recurring physical symptoms (pain, nausea, vomiting) during an upcoming or ongoing separation. At the same time, the description of ASD in adulthood, in contrast to that observed in childhood, is less detailed in the description of distress, as well as problems associated with sleep.

The DSM-5 also allows for a narrower TRS duration criterion, which for adults should be used as a “general guideline with some degree of flexibility”. The list of symptoms that meet criterion "A" in both classifications is almost identical and includes recurring excessive anxiety at actual and expected separation from the main figures of attachment, as well as constant worry about possible harm to oneself or the object of affection, or the occurrence of an adverse event (abduction, illness, death, etc.), which can lead to separation or loss of a significant figure. Individuals with ASD may be afraid or avoid staying at home or other places alone, refusing to leave the house or sleeping away from home because of separation anxiety. They may experience separation nightmares and recurring physical symptoms (pain, nausea, vomiting) during an upcoming or ongoing separation. At the same time, the description of ASD in adulthood, in contrast to that observed in childhood, is less detailed in the description of distress, as well as problems associated with sleep. At the same time, the presence of recurring complaints of somatic distress, such as nausea and abdominal pain, is more typical for children, while complaints of cognitive and emotional symptoms are more typical for adults [86]. In addition, adult patients with ASD have the opportunity to use various behavioral strategies (inaccessible to children) that aim to extend the time spent together with the object of attachment, such as initiating frequent phone calls or long conversations, developing and strictly maintaining such a daily routine that ensures the most frequent contact with a significant person, etc. [3].

At the same time, the presence of recurring complaints of somatic distress, such as nausea and abdominal pain, is more typical for children, while complaints of cognitive and emotional symptoms are more typical for adults [86]. In addition, adult patients with ASD have the opportunity to use various behavioral strategies (inaccessible to children) that aim to extend the time spent together with the object of attachment, such as initiating frequent phone calls or long conversations, developing and strictly maintaining such a daily routine that ensures the most frequent contact with a significant person, etc. [3].

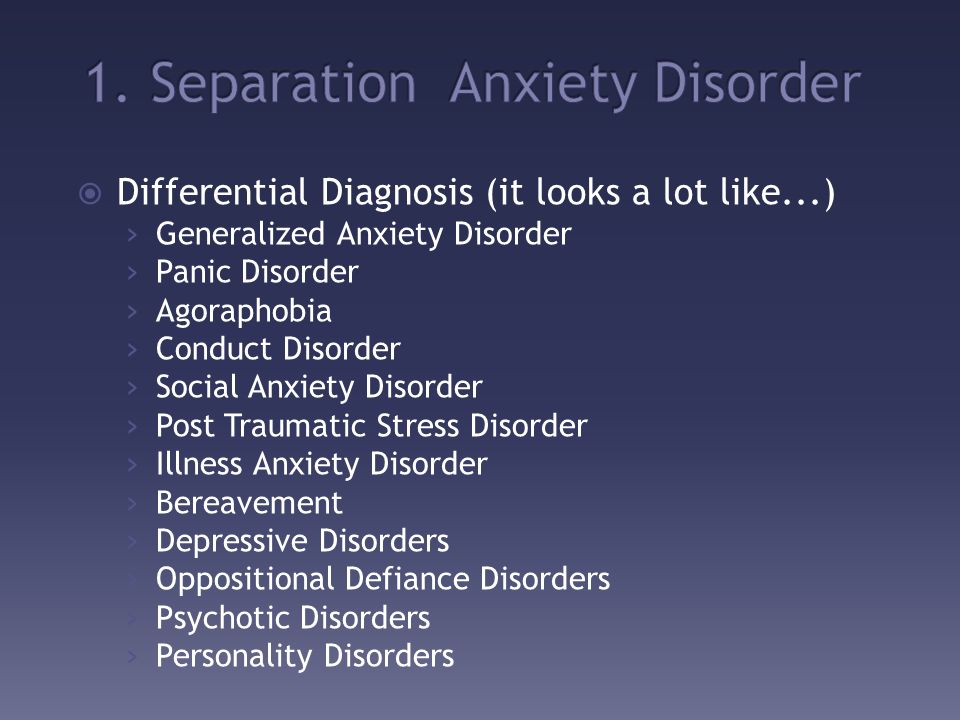

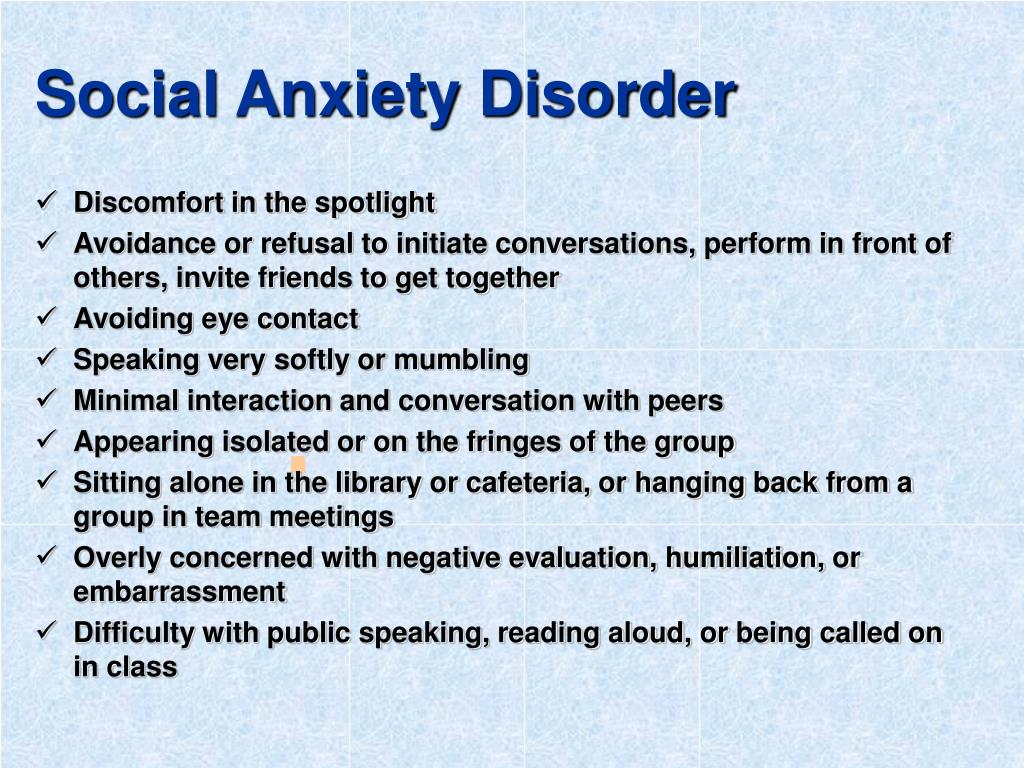

The problem of low detectability of HRS in adults, which all researchers pay attention to, is largely due to the phenomenological overlap of TS with other anxiety states [87]. In this regard, it seems relevant to consider the features of the differential diagnosis of CRT with other disorders that have similar manifestations.

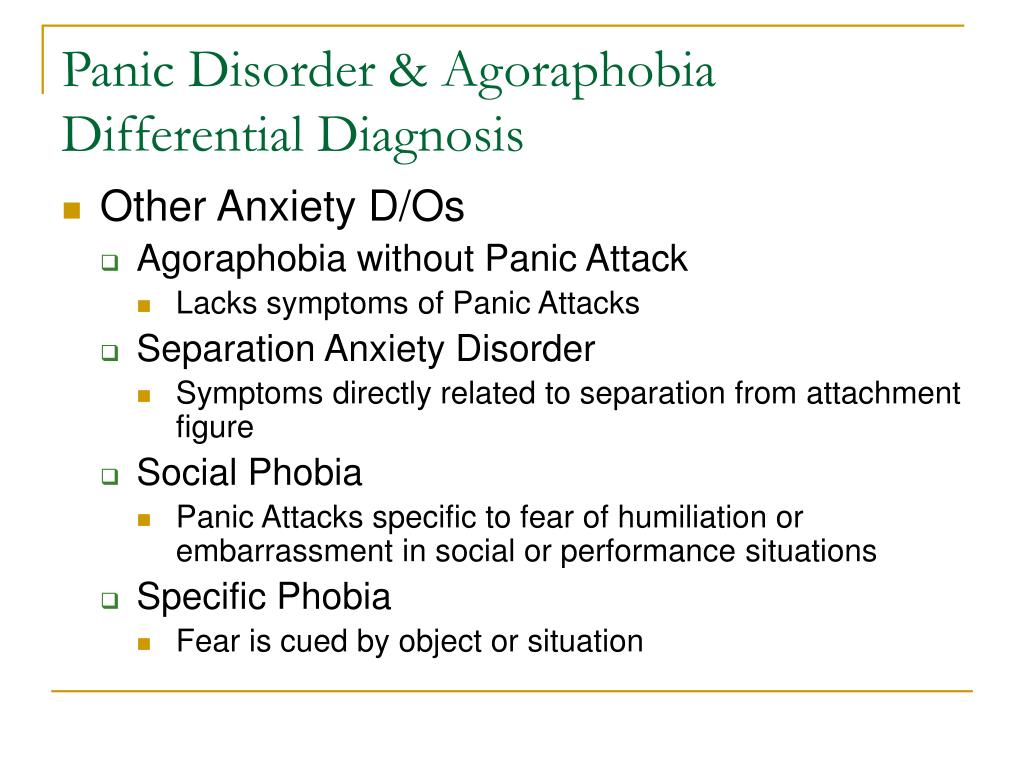

The greatest difficulties in diagnosing TRS in adults arise when it is necessary to differentiate it from PR with/without agoraphobia [24, 88]. The apparent similarity of the clinical manifestations of the disorders under consideration was the reason for conducting separate studies on the development of differential diagnostic features, the inclusion of which indicates the clinical independence of TMS. Thus, in the study by D. Silove and L. Marnane [89] found only three domains of symptoms overlap between adult TMS and PR with agoraphobia (anxiety about upcoming travel, sleep disturbances and anxiety associated with leaving the house), while all other symptoms are excellent. It is not excluded that patients with ASD may experience a panic attack, but their dominant fear is a potential or actual situation of separation from a person to whom a strong attachment has formed, and not at all fears of a recurrence of a panic attack. In addition, patients with PD are primarily concerned with their personal health and safety, while individuals with ASD are more concerned about the well-being of the object of their attachment, and their own health and safety is concerned about their own health and safety in the context of maintaining closeness with a significant person, which becomes impossible in the case, for example, of their illness [5].

Concerns about the health and safety of loved ones are seen in both adult TRS and GAD. This differential diagnostic problem arises when these conditions are distinguished already in childhood. Nearly 50% of children and adolescents with GAD worry that something bad might happen to their parents [90], and most children who meet the criteria for GAD have comorbid GAD [91]. The same problem persists into adulthood. The difference between DAD and GAD is that fear or anxiety about the loss of significant others is one of many other plots in generalized anxiety along with an over-preoccupation with various events and situations, while anxiety about separation and the loss of a limited number of significant others is a central characteristic. patients with TRS [5].

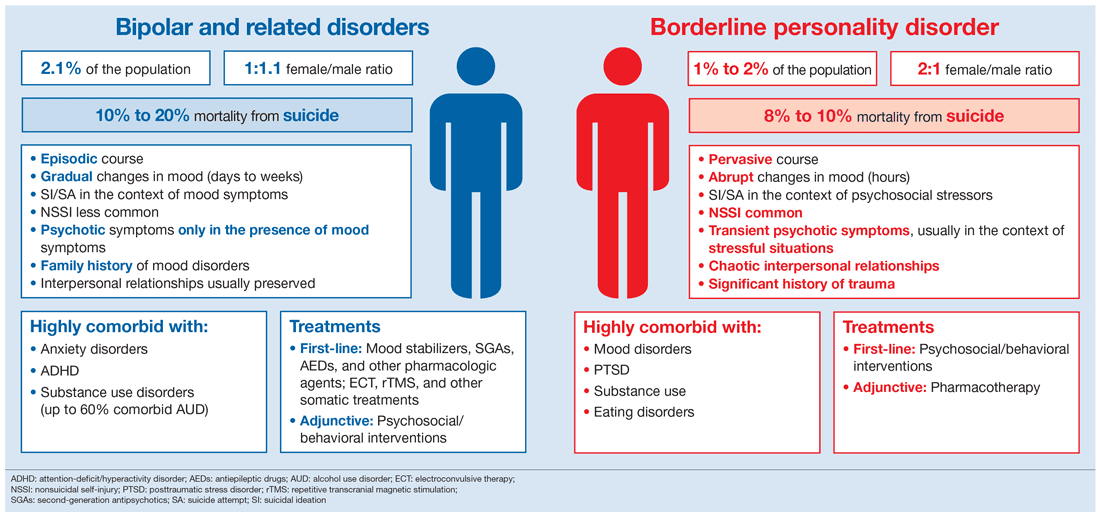

Differential diagnosis between adult ASD and personality disorders (PD) presents particular difficulties. In dependent PD, the fear of loss or separation is based on the inability to take care of oneself, cope with emotional problems independently, and make decisions, while in adults with ADHD, the fear of losing the object of affection is completely unrelated to issues of autonomy [29, 92]. Constant efforts to avoid the real or imagined fate of abandonment combine adult ASD with emotionally unstable borderline PD. Differential features in this case are affective instability inherent in borderline PD, uncertainty about oneself and most interpersonal relationships, which is not typical for TSD [92]. Fear of losing an attachment in STS may manifest as an excessive and unrealistic fear that the partner will commit adultery, suspicions of the partner's fidelity, which, ultimately, can lead to forced separation. In this case, TRS in adults has points of contact with paranoid personality disorder [5, 92]. Differential diagnosis in this case is based on the severity and totality of psychopathic features in paranoid personality disorder.

Diagnostic tools for the detection and evaluation of TRS

A number of diagnostic interviews and rating scales have been developed to facilitate the diagnosis and assessment of the severity of TRS in adults (Table 2).

One of the first and currently unused diagnostic tools was the Adult Separation Anxiety Structured Interview (ASA-SI) [3], which contains items derived from the DSM-IV-TR criteria for childhood ADMS modified for adulthood. Later, on the basis of ASA-SI V. Manicavasagar et al. [93] developed the Adult Separation Anxiety Questionnaire (ASA-27), a 27-item self-assessment of adult ASD symptoms. Due to its good psychometric properties, the questionnaire is often used in research. The Russian sample was adapted by A.A. Dityuk [94].

The path used to create the ASA-SI was followed by J. Cyranowski et al. [95], who adapted the symptoms of childhood ARS to adulthood and developed a new Structured Clinical Interview for Separation Anxiety Symptoms (SCI-SAS), which consists of two parts: the first allows retrospective assessment of symptoms of ARS in childhood, while the second is aimed at assessing the manifestations of TRS in adults. A retrospective assessment of the symptoms of TMS that adult patients probably experienced in childhood is also possible using the Separation Anxiety Symptom Inventory (SASI) developed by D. Silove et al. [96].

The Parents of Adolescents Separation Anxiety Scale (PASAS) [97] is rarely used due to its narrow diagnostic focus. It allows assessing the degree of separation anxiety of adolescent parents.

A new diagnostic tool is Severity Measure for Separation Anxiety Disorder-Adult [98]. It includes 10 items that generally meet DSM-5 criteria, which rate the past 7 days on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (all the time). Despite the content in this tool and DSM-5 of similar criteria for TRS, E. Schmit and R. Balkin [99] note that some items may not be fully compatible with the DSM-V criteria.

In the study of adult ASD, "psychological" questionnaires such as the Relationship Scales Questionnaire (RSQ) [59] and the Interpersonal Sensitivity Measure (IPSM) [100] are widely used. The RSQ measures attachment style (secure, withdrawn/avoidant, restless, anxious, fearful) and the IPSM contains a separation anxiety subscale, making them indispensable in the study of adult ASD.

Association of ASD in adults with other disorders

A high comorbidity of AMS in adults with other disorders has been reported in almost all studies. Thus, in 23% of patients with previously diagnosed TR, TRS is observed. The nature of comorbidity may differ depending on the age of onset of the disorder. M. Shear et al. [6] found that comorbid anxiety (OR 4.9) and affective disorders (OR 4.3) are common in cases of comorbid identification of TMS in adults with and without a childhood history (retrospectively) of TS. Thus, the OR was 4.3 for a specific phobia, 4.2 for PTSD, 3.9for PD, 3.7 for GAD, 3.6 for social anxiety disorder, 2.9 for agoraphobia, and 2.4 for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) [6].

Prolonged grief may be associated with TMS in adults. The adult cohort of patients with childhood-onset TMS has been found to have the highest risk of developing protracted grief [101]. In a study of war-affected Bosnian refugees, almost all adults with TSD were found to have co-existing PTSD, while only 50% of PTSD patients had TSD [30]. The severity of CRT symptoms depends on the nature of the comorbid pathology. So, according to S. Pini et al. [102], more severe variants of TS in adults were observed in patients with comorbid AR more often than in patients with an affective disorder. At the same time, the comorbidity of TRS with depressive disorder suggests a much greater number of depressive episodes [29]. The close connection of TRS in adults with dependent PD is emphasized in the works of G. Loas et al. [103] and A. Osone et al. [104].

Studies of TMS comorbidity are mainly devoted to the study of a variant of this disorder, the symptoms of which are "rooted" in childhood, and relate to the problem of specificity/nonspecificity of S.T. So, D. Silove et al. [24, 38] and M. Shear [105], based on data on a high combination of SRS and PR, consider juvenile SRS as a specific predictor of the development of PR with/without agoraphobia in adulthood. Numerous data on the relationship of this variant of ASD with the development of other anxiety and affective disorders in adults, especially in females [5], led some authors [24] to a different point of view. For example, M. Craske et al. [106] indicate that despite the high frequency of longitudinal associations between HRS in childhood and PR/agoraphobia in adults, these associations are not specific enough to explain the concept of HRS and PR as an alternative manifestation of a single pathophysiological process. Other researchers are more explicit [107, 108], emphasizing the non-specificity of this association and suggesting that TS in early life may represent a non-specific vulnerability to a wide range of anxiety and other disorders in adult life, including TS in adults. This point of view is confirmed by the study by T. Brückl et al. [109], which found an association of ASD in adolescents and young people (aged 14-22 years) not only with the development over the next 4 years of PD or agoraphobia (hazard ratio - RR 18), but also with a specific phobia (RR 2.7) , GAD (RR 9.4), OCD (RR 10.7), bipolar affective disorder (RR 7.7), pain disorder (RR 3.5) and alcohol dependence (RR 4.7).

Another hypothesis for ASD in adults is the “continuity” hypothesis [24], according to which the TS trajectory is similar to that of other childhood onset ADs, such as social phobia, whose symptoms “extend” from adolescence to adulthood and old age. Contributing to this continuity of symptoms is "insecure attachment," similar to terms such as "deviation sensitivity" or "interpersonal sensitivity," used to refer to a form of anxious attachment that persists from childhood to adulthood. However, if the “continuity” model is proven, then the previous hypothesis of a strong association of TS in early life with the risk of developing PR with/without agoraphobia should be questioned. It is noteworthy that studies aimed at testing the latter hypothesis did not include the adult form of RMS [110,111].

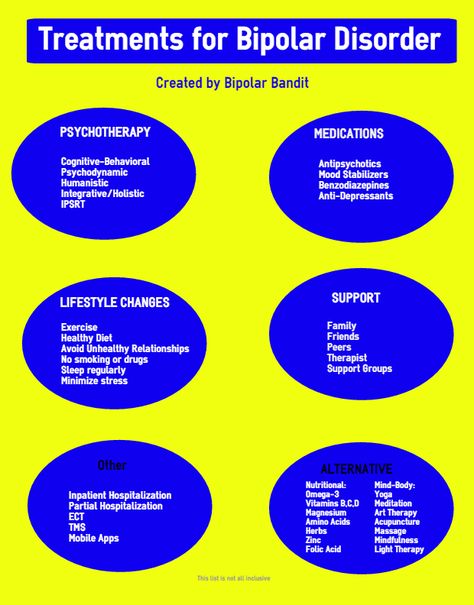

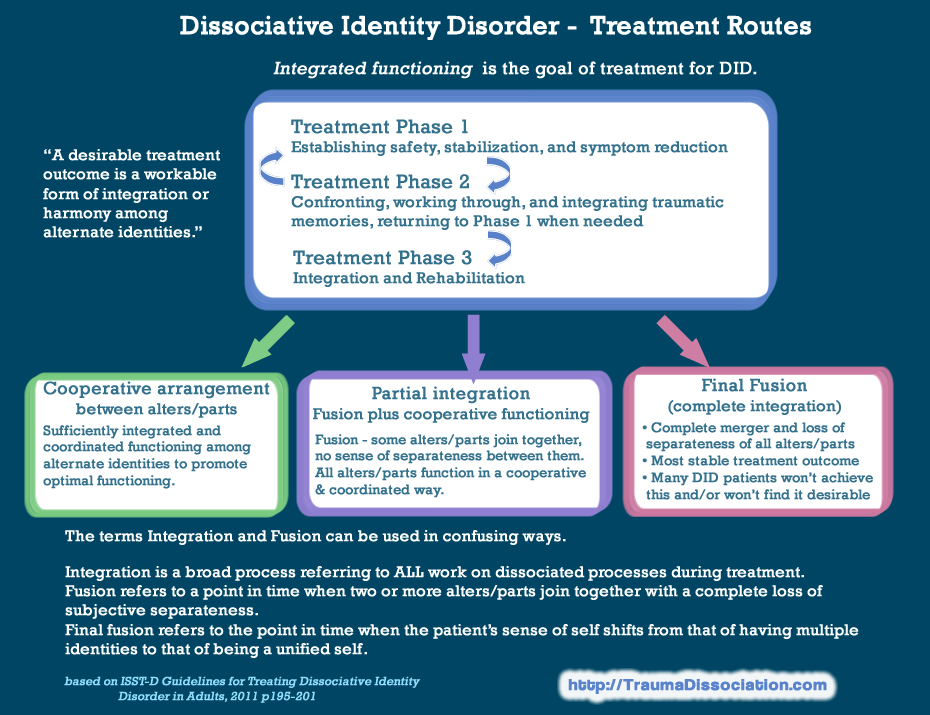

Treatment of TRS in adults

Therapeutic approaches for the management of TRS in adults are virtually non-existent. The results of the NCS-R study [6] showed that TMS in adults is a “debilitating” condition and 74.7% of these patients were treated for their emotional disorders, although in 68% of cases TMS was not a target of therapy.

The first description of a targeted therapeutic intervention for the symptoms of TMS in adults was the treatment of a person with panic attacks, the development of which was preceded by the manifestation of TS at an early age and its symptoms persisted throughout life [112]. The successful outcome of therapy in this observation was achieved through constant analysis of the patient's behavior and the use of a number of psychotherapeutic approaches: imaginary (in imagination) and real desensitization, recognition by the patient of the cognitive strategies that he used to protect against growing anxiety, teaching him progressive muscle relaxation. Two studies investigating the effect of CT on the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for other TDs noted a negative effect of CT on treatment outcome. So, C. Aaronson et al. [113] showed that the effectiveness of CBT in patients with panic disorder and concomitant TMS in adults is 4 times lower than that of isolated PR. In a study by V. Manicavasagaar et al. [3] also showed that conventional CBT targeting other TRs does not reduce TS in adults. According to M. Dugas and R. Ladouceur [114], a potential target of CBT for TRS in adults can be NN using specific cognitive and behavioral techniques aimed at it, providing for the patient's awareness of the problem [114].

The only attempt to investigate the effectiveness of psychopharmacotherapy of ASD in adults is the work of F. Schneier et al. [115]. The placebo-controlled, randomized trial included adult patients with an established diagnosis of TMS, 13 of whom received the antidepressant vilazodone (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and partial 5HT1a receptor agonist) and 11 received placebo. The groups of patients treated with vilazodone and placebo did not differ significantly in terms of therapeutic response at week 12, but the rate of regression of symptoms (at the trend level) was more pronounced in the active therapy group.

This review highlighting a new diagnostic category in the TR series, TRMS, should contribute to further research into its epidemiology, etiology and treatment. The first step in addressing these issues is to raise the awareness of professionals about the position of adult ADHD in the classification systems of mental and behavioral disorders.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*e-mail: [email protected]

Literature

1 This table compares ICD-10 with DSM-5.

Anxiety disorders in children. What are Anxiety Disorders in Children?

IMPORTANT

The information in this section should not be used for self-diagnosis or self-treatment. In case of pain or other exacerbation of the disease, only the attending physician should prescribe diagnostic tests. For diagnosis and proper treatment, you should contact your doctor.

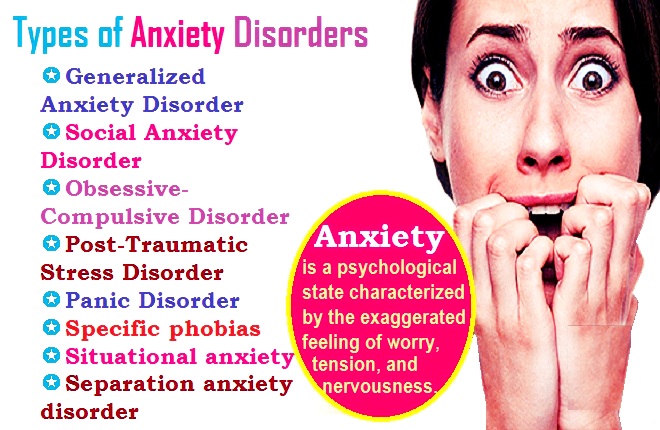

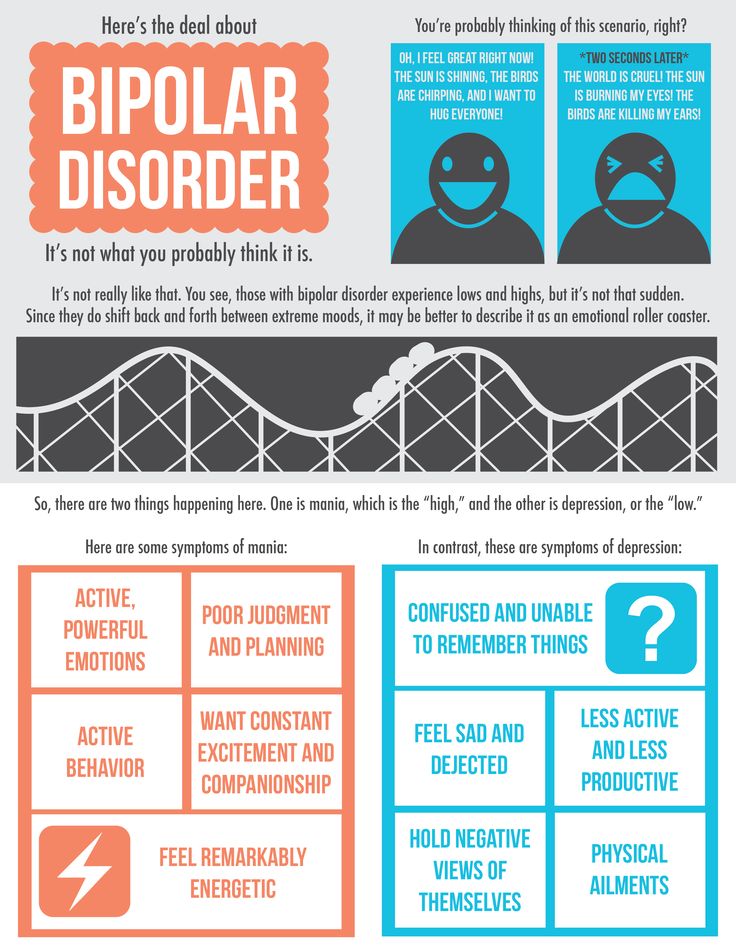

Anxiety disorders in children are a group of affective disorders characterized by emotional stress, anxiety, and fears. At the center of the child's experiences are negative expectations and premonitions about his own life, health, relationships in the family and school. Sometimes anxiety takes the form of obsessive thoughts, compulsions, phobias, panic attacks, and nightmares. The main diagnostic methods are history taking, conversation, observation. Additionally, psychodiagnostics is used. A common treatment is cognitive behavioral therapy in combination with antidepressants and anxiolytics.

ICD-10

F41 Other anxiety disorders

- Causes

- Pathogenesis

- Classification

- Symptoms

- Complications

- Diagnostics

- Treatment of anxiety disorders in children

- Prognosis and prevention

- Prices for treatment

General

Anxiety disorders in children are a broad group of emotional disorders in childhood. Their prevalence is constantly growing, currently pathology ranks second among mental illnesses in childhood and adolescence (after behavioral abnormalities). Active research over the past 20 years has made it possible to identify new nosological units, which are now included in the ICD-10 and DSM-IV - the official classifiers of diseases.

Epidemiological indicators range from 4 to 15% in various age groups. Preschoolers and younger schoolchildren are most susceptible to anxiety symptoms. In girls, variants of disorders with a pronounced emotional component predominate, in boys - with a somatic component (digestion and sleep disorders, abdominal and headaches).

Anxiety disorders in children

Causes

Anxiety is a natural reaction that increases concentration and activates the mechanisms of fight or flight in a situation of threat. With its strengthening, the adaptation process is disrupted, constant psychophysiological tension leads to exhaustion. In such cases, they speak of an anxiety disorder. In children, it can be caused by:

- Congenital factors. The results of twin studies prove that the tendency to intense anxiety is inherited. It may be due to the peculiarities of humoral regulation and functioning of the nervous system. Also at risk are children with prenatal and natal lesions of the central nervous system.

- Parenting style. Anxiety symptoms are formed as a result of a certain attitude of parents towards a child. The development of disorders is facilitated by the psychasthenic traits of the mother (less often, the father), hyperprotection, and directive methods of education.

- Traumatic event. Anxiety in a child can be triggered by the experience of illness, separation from a loved one, a sharp deterioration in the material capabilities of the family, disasters, natural and military-political disasters. A single impact of psychotrauma is more easily tolerated by children, repeated episodes form neurotic disorders.

Pathogenesis

The periodic manifestation of anxiety is a normal reaction of the body, serves as a motivational component of behavior, providing a high level of vigilance, purposefulness and readiness to make efforts to achieve results. However, frequent, uncontrollable fears negatively affect the ability to adequately assess the situation and act purposefully, and in severe cases distort the perception of everyday events. Anxiety is always future-oriented and is manifested by fear of what may happen. The more pronounced the disorder, the wider the range of events that are regarded as dangerous.

At the physiological level, high anxiety is associated with dysfunctions in the parts of the limbic system and the hippocampus responsible for regulating emotions. IP Pavlov considered fear and anxiety as variants of the manifestation of a passive-defensive reflex. These emotions are based on the instinct of self-preservation, which activates all body systems for flight or fight. And if normally the excitation and inhibition of the central nervous system is balanced, the natural defensive reflex is replaced by relaxation, then with an anxiety disorder there is a rigidity of neural processes - an emotion that has become irrelevant is experienced again and again.

Classification

There are many types of childhood anxiety disorders with different symptoms. Their common manifestation is prolonged anxiety, inadequate to the existing situation, which negatively affects the daily life of the child, reduces the feeling of psychological comfort. Taking into account the features of the clinical picture, there are:

- General anxiety disorder. With generalized AR, children constantly worry about various areas of life - about health, safety, relationships with peers and parents, academic success. Of all the futures, the negative one seems the most likely.

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder. In OCD, anxiety is manifested by compulsive actions and thoughts. Rituals provide a sense of calm for a short time.

- Phobias. A premonition of danger can take shape in a persistent fear (phobia) of certain objects and situations. Often children are afraid of heights, darkness, fictional monsters, social contacts.

- Panic attacks. Intense anxiety is sometimes manifested by an increase in vegetative symptoms - dizziness, increased heart rate, respiratory spasm, muscle strain that make up the clinic of a panic attack.

The child begins to avoid events that can provoke panic.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder. This variant of anxiety arises as a result of experiencing a traumatic event that does not fit into the framework of habitual experience. PTSD in children is manifested by a sudden flash of memories and nightmares.

Symptoms

The main symptom is persistent, pronounced anxiety. Patients feel emotionally tense, cannot distract themselves from negative experiences and relax. Due to anxiety, they have difficulty concentrating, adolescents report feeling "empty in the head." Increased nervousness is manifested by irritability, tearfulness, fearfulness. Starting at unexpected sharp sounds, changes in illumination, sudden touches is characteristic. Behavior becomes avoidant (restrictive): children refuse communication, walks, active games, travel, and the use of certain products.

Among the physical symptoms of anxiety disorders, causeless fatigue and rapid exhaustion predominate. Patients complain of dizziness, weakness, headache and muscle pain, discomfort in the abdomen and chest. There may be increased sweating, especially in stressful situations, palpitations, shortness of breath, tremors and tremors, feeling of a lump in the throat, hot flashes, chills. Appetite is often reduced, but sometimes gluttony develops, followed by nausea and vomiting. Sleep disturbances include difficulty falling asleep, waking up in the middle of the night, and nightmares.

The symptoms of phobic disorders are persistent fears. A fear of situations is formed that does not actually pose a threat or can be dangerous only under certain conditions. Young children are afraid of the dark, heights, separation from their mother. Preschoolers are actively developing their imagination, fears are associated with fabulous or fictional monsters - dragons, dinosaurs, animated skeletons, zombies, werewolves. In schoolchildren, social phobias come to the fore - the fear of communication, acquaintance, public speaking. Adolescents experience fear of loss of control, death, insanity, shame. Anxiety after experiencing a psychotrauma is characterized by "flashbacks" - uncontrollable frightening influxes of memories, nightmares at night.

In obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety is accompanied by the formation of obsessive ideas of a frightening nature. Children mentally play out negative scenarios, while experiencing fear. To cope with emotional stress, they are partly helped by ritual actions - compulsions. The most common are frequent washing of hands, sorting out the edges of clothes, biting nails, walking around the perimeter of the room. In panic attacks, anxiety occurs for no apparent reason and instantly increases, manifesting as autonomic symptoms. The state of health worsens - there is dizziness, darkening in the eyes, a feeling of alienation of one's own personality, the unreality of objects and events. The fear of another panic attack, avoidant behavior, is formed for the second time.

Complications

Emotional disorders often lead to complications, as children are unable to understand and critically evaluate their own experiences. They do not report a depressed mood and a constant feeling of anxiety, so the diagnosis is carried out out of time. Adolescents do not talk about disturbing thoughts, fearing misunderstanding and judgment from others. The long course of the disorder without adequate therapy is complicated by depression, autistic behavioral changes. Patients are prone to self-accusation, feel loneliness, become isolated, avoid communication. The risk of social maladaptation, suicidal attempts on the background of depression increases.

Diagnostics

The main examination is carried out by a psychiatrist: talking with parents and the child, he collects clinical and anamnestic data, finds out the presence of somatic diseases, congenital pathologies of the central nervous system, clarifies living conditions, adaptation features in kindergarten, school. With the predominance of complaints about the state of physical health, the doctor refers to a consultation with a pediatrician, a pediatric neurologist for differential diagnosis. Special research methods include:

- Conversation. In the course of easy communication with the child, the specialist often manages to determine the cause of anxiety - fears, destructive relationships at school and family, problems with learning, memories of psychotrauma. With severe anxiety, children are passive, but become more open when establishing trusting contact and discussing topical, disturbing topics.

- Surveillance. The doctor evaluates the child's emotions and behavior. The anxiety state is characterized by emotional and motor stiffness, hyperreactions to unexpected stimuli (noise outside the door, entry without warning strangers). Babies often do not want to leave their mother, they are afraid to look into the eyes.

- Questionnaires. Adolescents are asked to answer the questions of standardized methods to identify increased anxiety.

The Spielberger-Khanin scale, the Phillips school anxiety test, and the Beck anxiety test are used.

- Projective tests. To examine children of preschool and primary school age, methods are used that reveal unconscious dominant emotions (fear, anxiety) and problems in interpersonal relationships. Common diagnostic tools are drawing tests (a drawing of a person, a family, a non-existent animal) and a projective test “Choose a face” (R. Tamml, M. Dorki, V. Amen).

Treatment of anxiety disorders in children

Therapeutic assistance to children is provided by psychiatrists and psychotherapists, but for successful rehabilitation, the involvement of the mother, father and other close relatives is necessary. The volume of treatment procedures is determined individually: for mild forms of disorders, one course of psychotherapy and parental support is enough, for severe cases, long-term medication and periodic meetings with a psychologist are necessary. The general treatment regimen is as follows:

- Psychotherapy. In sessions of cognitive behavioral therapy, the psychotherapist corrects destructive attitudes, replaces negative judgments with positive ones, and teaches skills for managing emotions and solving problems. As a result, the child learns to independently resolve difficult situations, to resist the influence of stressful influences. If the anxiety is based on fears or phobias, a systematic desensitization technique is applied.

- Family psychotherapy. To eliminate the anxiety of the child, it is necessary to correct the increased anxiety of parents and problematic family relationships - factors in the development and maintenance of the disorder. Interacting with the family, the psychotherapist uses the techniques of cognitive psychotherapy, Gestalt therapy. It establishes normal communication between all family members, teaches parents to better understand the child, control emotions, and avoid situations that provoke anxiety in a son or daughter.

- Drug therapy. Medication is indicated for moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety. For long-term therapy, antidepressants are used. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the drugs of choice. The use of anxiolytics under the age of 18 years is justified in exceptional cases when there are acute symptoms. For this purpose, benzodiazepines are used, therapy is carried out for a short time.

Prognosis and prevention

The likelihood of recovery is largely determined by the timeliness of the start of treatment and the willingness of family members to help the child cope with emotional problems. With early access to specialists, the prognosis is favorable. Prevention of anxiety disorders is based on trusting family relationships, the right ways of education, based on love and respect, without overprotection and authoritarianism. It is important to show sincerity, openness in communication, share your own positive experience of overcoming insecurities and fears. In difficult situations, it is necessary to provide support, in case of failures - to analyze the experience gained, to teach the child to draw conclusions.

You can share your medical history, what helped you in the treatment of anxiety disorders in children.

Sources

- Modern ideas about the diagnosis and treatment of anxiety disorders / Khaustova EA, Bezsheiko VG// International neurological journal. - 2012 - No. 2 (48).

- Anxiety in children: causes and features of manifestation/ Nekhoroshkova AN, Gribanov AV// Modern problems of science and education. - 2014 - No. 5.

- Neurosis in children / Chutko L.S. – 2017.

- Early diagnosis of anxiety-phobic disorders in adolescents in general medical practice // Popov Yu.V., Pichikov A.A. – 2012.

- This article was prepared based on the materials of the site: https://www.krasotaimedicina.ru/

IMPORTANT

Information from this section cannot be used for self-diagnosis and self-treatment.