Does lamictal help with depression

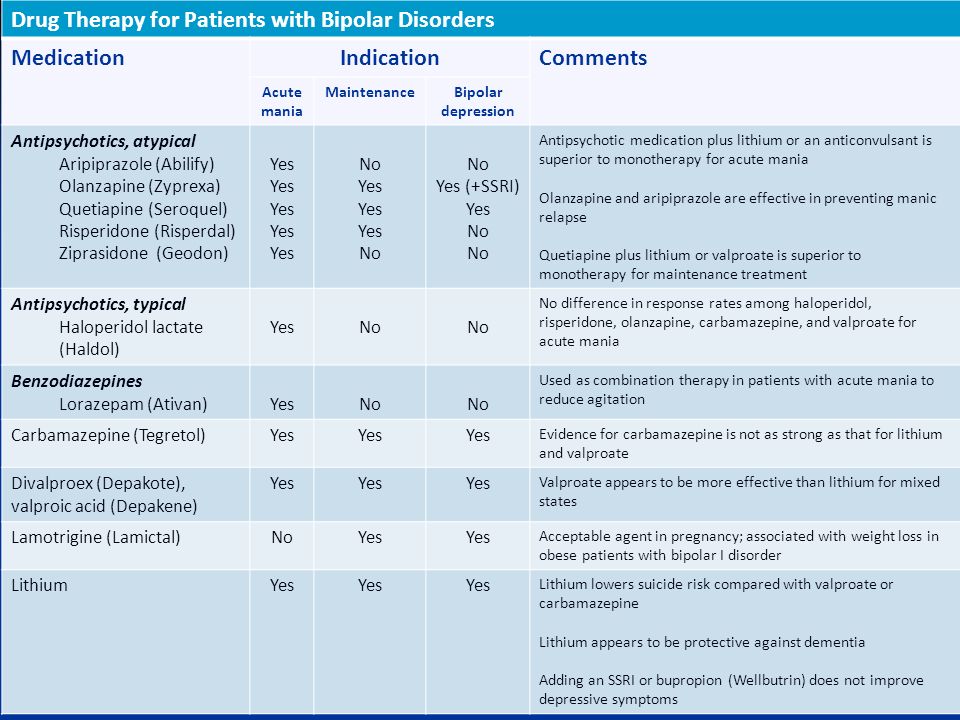

Psychiatric Uses of Lamotrigine

Lamotrigine (Brand names: Lamictal, Lamictal CD, Lamictal ODT, Lamictal XR)Like other mood stabilizers, lamotrigine was originally developed as an anticonvulsant to treat seizures and is often used with other medications in the treatment of bipolar (manic-depressive) disorder. For the latest information on the use of lamotrigine, Psycom spoke with Joseph Goldberg, MD, Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, and co-author of Managing the Side Effects of Psychotropic Medications, 2nd Ed, a textbook published by American Psychiatric Association Publishing and Christopher Aiken, MD, the director of the Mood Treatment Center in North Carolina.

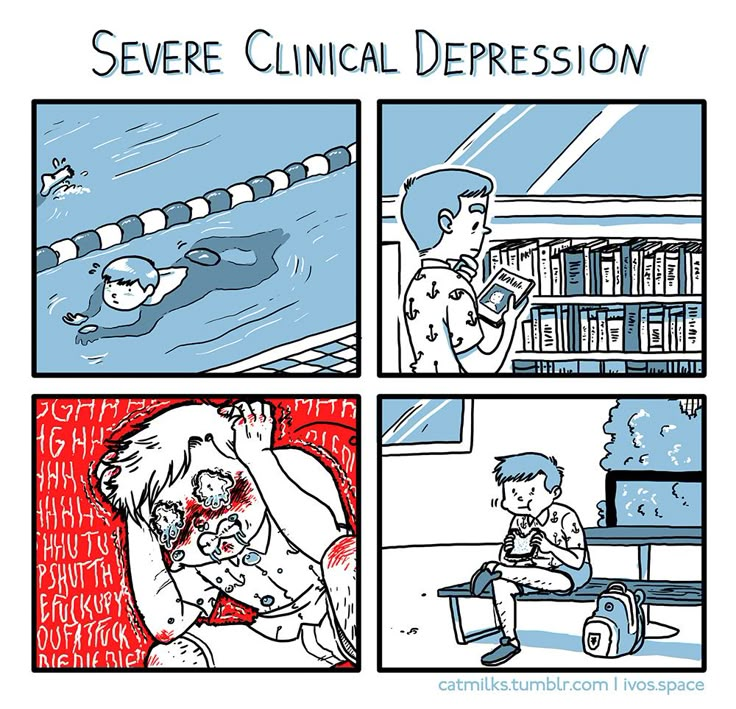

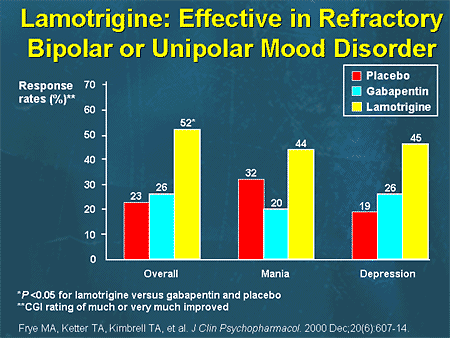

Lamotrigine is the only mood stabilizer that calms mood swings by lifting the depression rather than suppressing the mania, says Dr. Aiken. "That makes it a great choice for the bipolar spectrum, where the depressive symptoms usually outweigh the manic ones. Its greatest benefit is in prevention. It can prevent both the depressive and manic side, but its benefits are much stronger for depression and it does not treat active mania or hypomania."

Dr. Aiken adds that part of the reason patients prefer lamotrigine is that it’s generally well tolerated. "In the original research studies people reported more side effects on the placebo than on lamotrigine. That may sound impossible, but it’s likely that lamotrigine helped them feel better physically by treating their depression," explains the mood disorder expert adding that lamotrigine is also largely free of the “medicated” feelings that people dislike with mood stabilizers. "People don’t tend to feel dull, flat, or groggy on it."

In some research studies comparing a placebo to the medicine, the results were exceptional. "Lamotrigine is the only medicine we know of where patients were unable to tell they were taking the medication," he explains. "It didn’t make them feel medicated, and its benefits built up very gradually. After 2 years, people taking lamotrigine had half as many days of depression as those who did not take it."

After 2 years, people taking lamotrigine had half as many days of depression as those who did not take it."

Which conditions are treated with lamotrigine?

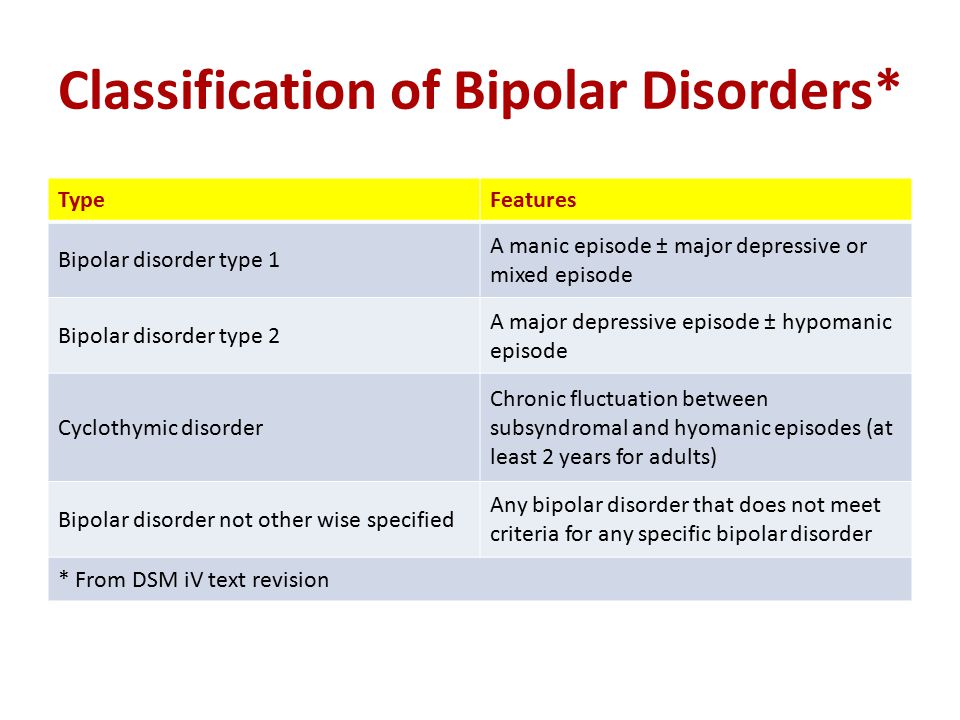

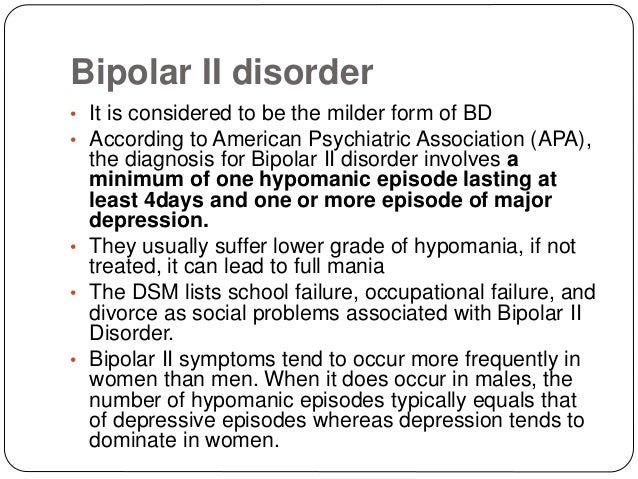

Although lamotrigine is not considered an antidepressant, it is used as a maintenance treatment for bipolar I disorder in patients 18 and older to help stabilize mood changes by delaying the time to occurrence of mood episodes in patients treated for acute mood episodes with standard therapy. (Bipolar I disorder is characterized by manic episodes.)¹˒²

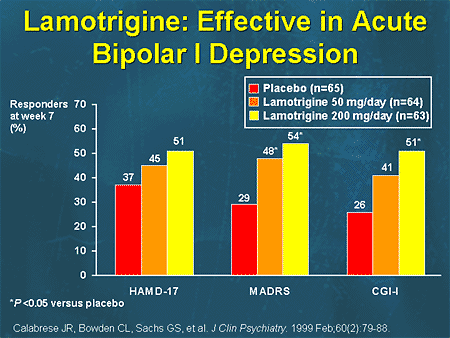

It is considered second-line therapy. “The drug manufacturer’s original studies of lamotrigine in bipolar depression found that improvements were stronger in bipolar 1 than bipolar II disorder,” Dr. Goldberg recalls. (Bipolar II disorder is characterized by longer episodes and more frequent occurrence of major depression and hypomania.) Newer research suggests, however, that lamotrigine may be even more effective as a mood stabilizer in preventing relapses in treating bipolar II disorder. ²

²

There are also conditions lamotrigine treats off-label including borderline personality disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), Dr. Aiken says.

How does lamotrigine work?

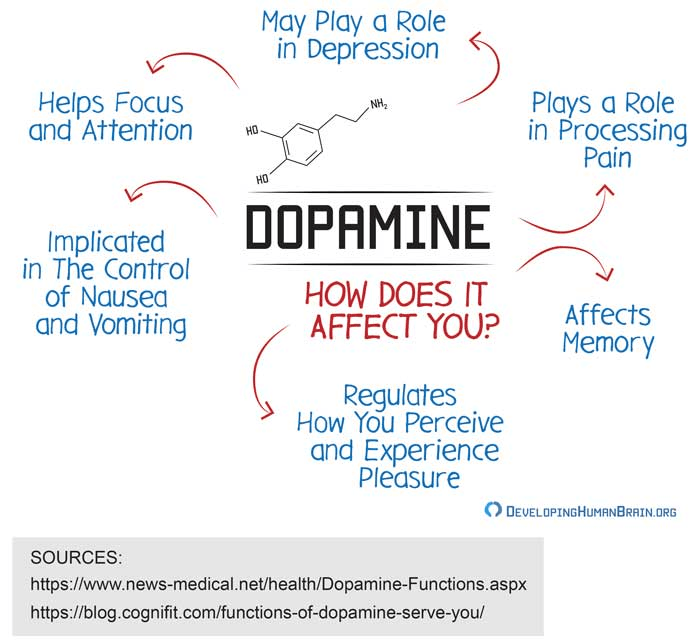

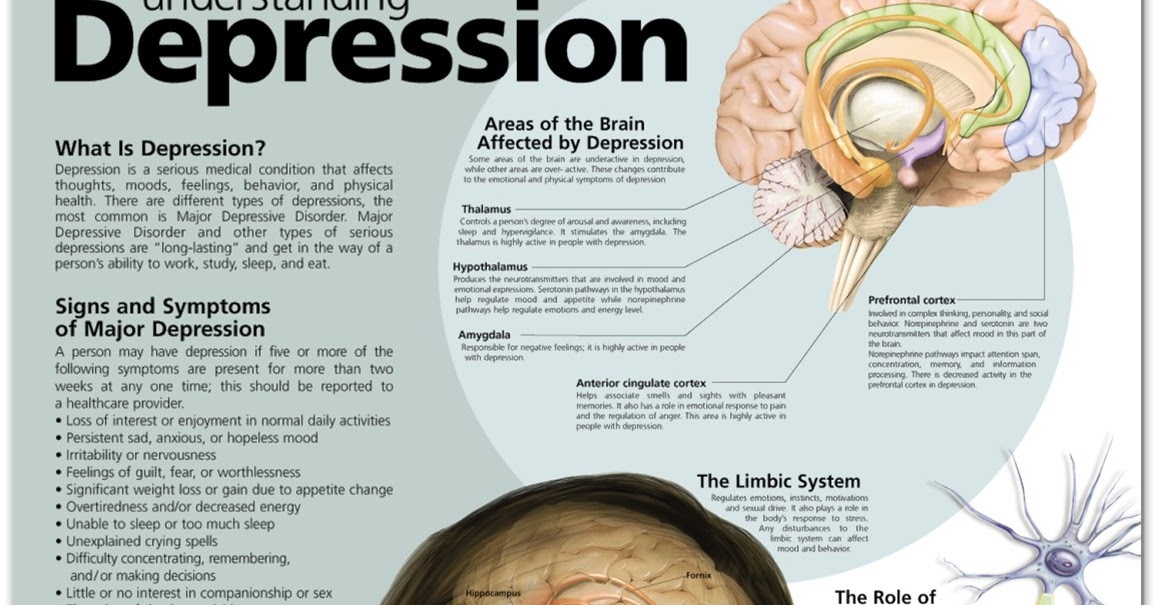

While the exact mechanism of action is not entirely understood, lamotrigine delays the time between mood changes and manic or depressive states in people with bipolar disorder by decreasing the intensity of irregular electrical activity in the brain. People with bipolar disorder are at high risk of experiencing recurrent and relapsing episodes of mood change. Maintenance treatment with lamotrigine helps reduce the risk by preventing or delaying these recurrences and relapses.

“Many clinicians think that lamotrigine helps achieve and sustain even moods over time by virtue of its antidepressant properties, rather than anti-manic (mood-stabilizing) properties,” says Dr. Goldberg. “It works with mood stabilizers like lithium and Divalproex, but it’s not interchangeable with these drugs and cannot be used in their place. ”

”

The efficacy of lamotrigine appears to be similar to the effects of lithium, yet is better tolerated.

Lamotrigine is used over time as a preventative medication. Clinical trials that looked at lamotrigine’s potential for treating acute (in-the-moment) episodes of mania found no difference between the medication and placebo.²

Is there a typical dose of lamotrigine?

Your doctor will initially prescribe a low dose of lamotrigine and gradually increase your dose every week or two for several weeks, until you reach an effective dose level.

“Treatment guidelines for target blood levels of lamotrigine have not been established for conditions other than epilepsy,” Dr. Goldberg points out. “In relapse prevention studies conducted by its manufacturer, however, 200 mg/day was found to be a better target dose than 50 mg/day, while higher doses (400 mg/day) did not provide greater benefit against relapse.”

The dosing regimen of lamotrigine can depend on which other medications you are taking to treat bipolar disorder, and is adjusted when you wean off and discontinue other medications. It may also depend on indication and patient age.

It may also depend on indication and patient age.

“Some medicines slow down the metabolism of lamotrigine (notably, Divalproex), requiring a slower rate of increase and a lower target dose,” notes Dr. Goldberg. “Others speed up its metabolism (notably, carbamazepine), requiring a faster-than-usual dose increase and a higher-than-usual target dose.”

Also, estrogen derivatives (including hormonal contraceptives) induce lamotrigine metabolism. Dosage adjustments will be necessary in most patients who start or stop taking estrogen-containing oral contraceptives while taking Lamictal.

Lamotrigine comes in several forms for treating bipolar disorder: Tablets, chewable tablets, dissolving tablets. Your doctor may tell you to take tablets once a day, twice a day or every other day.

If you miss a dose of lamotrigine, take the missed dose as soon as you remember. If it is close to the time of your next dose, however, skip the missed dose and continue with your usual schedule. Never take a double dose of lamotrigine.

Never take a double dose of lamotrigine.

How long does it take to work?

In certain cases, the antidepressant and antimanic benefits of lamotrigine are noticed pretty early on in the treatment cycle, says Dr. Aiken. "For some other patients, though, effects are seen after about a month of being on lamotrigine treatment. But there will always be others that take a bit longer to experience the positive effects."

Cost of Lamictal/Lamotrigine

When ordered in lots of 100 tablets, here is the breakdown in pricing for one tablet of the medication in the following doses (Note: pricing information generated April 2011):

$4.83 for 25 mg tablet

$5.43 for 100 mg tablet

$5.93 for 150 mg tablet

$6.67 for 200 mg tablet

Generic cost (lamotrigine) is as follows:

$0.3 for 25 mg tablet

$0.3 for 100 mg tablet

$0.53 for 150 mg tablet

$0.53 for 2000 mg tablet

Advantages of Lamotrigine

Dr. Aiken reports there are some major advantages of lamotrigine including:

Aiken reports there are some major advantages of lamotrigine including:

It's effective in a majority of bipolar patients Almost two-thirds of patients who are suffering from bipolar mood disorders have responded extremely well to lamotrigine.

It's ideal for mixed states People who, due to mania switches during intense cycling, have not been able to rely on other antidepressants have responded well to lamotrigine when given in therapeutic doses.

It's good for patients who respond to nothing else Patients who fail to respond to any other mood stabilizers and lithium have shown good results when treated using lamotrigine.

There are minimal side effects Lamotrigine has minimal side effects that usually fade away after some time.

Who can (and cannot) take lamotrigine for bipolar disorder?

Doctors may prescribe lamotrigine to adults or adolescents who are otherwise being treated for bipolar disorder or weaning off other medications used to treat bipolar disorder. Older adults may be more sensitive to the effects of lamotrigine and prescribed lower doses. "When people respond to lamotrigine, they often say they can see things in perspective better and are less reactive under stress. They usually still have days of depression, but these tend to be shorter and less frequent," says Dr. Aiken.

Older adults may be more sensitive to the effects of lamotrigine and prescribed lower doses. "When people respond to lamotrigine, they often say they can see things in perspective better and are less reactive under stress. They usually still have days of depression, but these tend to be shorter and less frequent," says Dr. Aiken.

Children under age 18 are at higher risk of developing a skin rash from lamotrigine if dosed too rapidly. In spite of the potential side effects, however, Dr. Goldberg points out that many studies support the use of lamotrigine for treating bipolar disorder in youth.

Definitive information about the safety of lamotrigine in pregnancy is not available, as there are no adequate studies in a pregnant woman population, but according to Dr. Goldberg, many doctors perceive it to be among the safer options when treatment benefit outweighs risk to the fetus, especially in women who are more prone to depression than mania. Like many psychotropic drugs, lamotrigine is secreted into breast milk, so women are advised to discuss with their doctors the risk and benefits of breastfeeding while taking lamotrigine.

Lamotrigine is not recommended in patients who have demonstrated hypersensitivity to the medication or any of its ingredients.

As with any medication, Dr. Goldberg adds, allergic reactions to lamotrigine can occur. Get immediate emergency help if you show any signs of an allergic reaction, such as hives, facial or throat swelling, or difficulty breathing. Notify your doctor if you develop a skin rash, especially if it occurs within your mouth or on soft body tissue such as eyelids or around nasal openings, and if it is blistering, peeling, painful, burning, or involves a fever or sore throat. Be sure to report all medications you are taking to medical staff.

Lamotrigine Side Effects

Some people who take lamotrigine may experience adverse reactions or side effects. Serious side effects that should be reported immediately to your doctor include:

Any skin rash, blistering or peeling of skin

Painful (burning) sores in or around the mouth, eyes or genitals

Jaundice (yellowish skin or eyes)

Swollen gland, fever, severe muscle pain

Weakness, drowsiness, confusion

Stiff neck, headache

Increased sensitivity to light

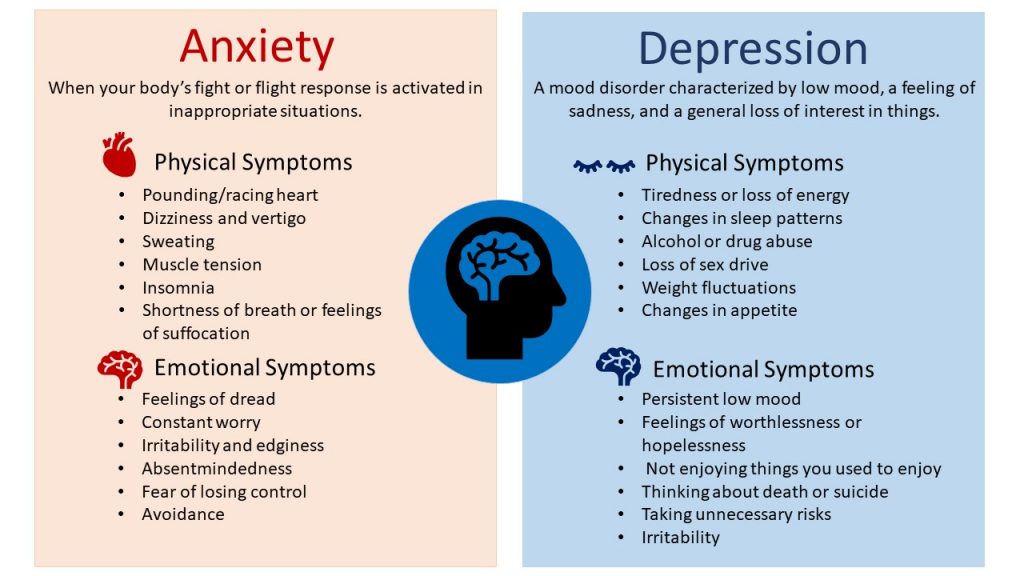

Mood or behavior changes, such as depression, anxiety, agitation, hostility, restlessness, mental or physical hyperactivity, suicidal thoughts

Common side effects of lamotrigine that are not emergencies but should also be reported to your doctor include:

Headache or dizziness

Blurred or double vision

Dry mouth

Gastrointestinal distress such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea or stomach pain

Fever, sore throat, runny nose

Drowsiness or fatigue

Tremor

Insomnia

The biggest risk with lamotrigine is a rare allergic reaction called Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, which can be fatal if left untreated. First a patient may experience flu-like symptoms of fever, cough or sore throat, then a rash or skin blistering will follow.

First a patient may experience flu-like symptoms of fever, cough or sore throat, then a rash or skin blistering will follow.

Most rashes have occurred within two to eight weeks of initiating treatment, and is more common in the pediatric population compared to adults. The risk of rash increases with higher starting doses, higher escalating doses and use of lamotrigine in combination with valproate. Early clinical trials and follow-up research showed that the overall incidence of any skin disorders was 11% to 12% in both bipolar I and bipolar II patients treated with lamotrigine. ²

Many medications can cause this reaction, including antibiotics like Bactrim and penicillin and over-the-counter medications like Tylenol and Motrin. Some ways to try to prevent lamotrigine rash include:

Dosing increases must be raised very slowly.

It should be stopped if any new rash or skin changes occur while you’re starting the medication, unless the rash is clearly known to be non-drug-related.

(After the first 3 months the risk of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome declines to almost zero).

(After the first 3 months the risk of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome declines to almost zero).To avoid false-alarm rash confusion, the use of new soaps, getting a sunburn, exposure to poison ivy and starting any other new medications should be avoided during the first 3 months of starting lamotrigine.

With those steps, the risk of this severe rash is about 1 in 3,000 in adult patients; without them, it’s more like 1 in 100. "Unfortunately, there is still a high risk of non-serious, benign rashes (10% chance), so many people have to stop lamotrigine to be on the safe side," Dr. Aiken explains. "If you responded to lamotrigine but had to stop it because of a rash, it may be possible to restart at a lower dose."

Does lamotrigine interact with any medications or other substances?

Certain other drugs can affect the way lamotrigine works in your body by decreasing its effectiveness or delaying its excretion from your body. These include hormonal birth control methods, estrogen-containing contraceptives, hormone treatments, the antibiotic rifampin, seizure medications such as phenobarbital, and valproic acid, which is also used to treat bipolar disorder.

Your doctor will carefully prescribe and monitor your dosage when lamotrigine is taken with other treatments. Avoid alcohol, cannabis, and other substances that can increase dizziness or drowsiness while taking lamotrigine. To rule out dangerous side effects, discuss all other medications or mind-altering substances you consume with your doctor before taking lamotrigine.

One recent British study found that folic acid supplements can cancel out lamotrigine’s benefits (Geddes et al., 2016). "No one expected that result, as folic acid usually helps depression, and other medications, like valproate (a mood stabilizer approved for mania associated with bipolar disorder, seizures/epilepsy, and migraine headaches)," says Dr. Aiken. "More research is needed before we can fully trust this result, but until then, we recommend taking lamotrigine without any folic acid supplements, including those found in multivitamins. Once you’re doing well on lamotrigine, if you decided to add folic acid, watch out for a potential loss of benefits. "

"

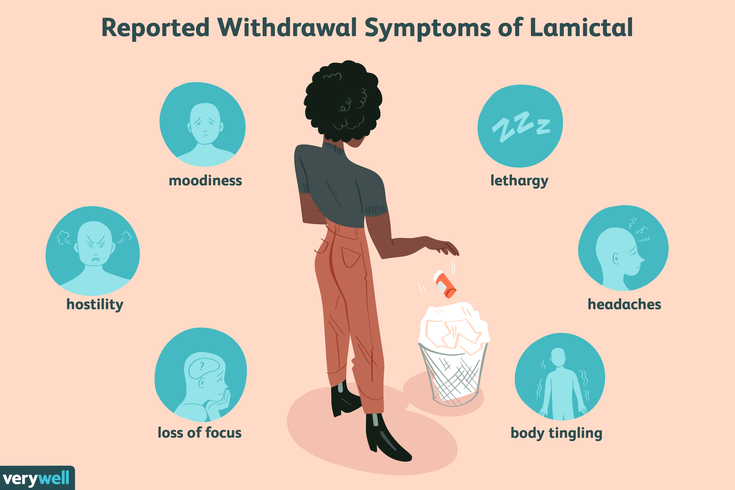

Is it OK to suddenly stop taking lamotrigine?

It is NOT recommended to discontinue lamotrigine abruptly, as this may increase risk of seizures. Consult your doctor before stopping lamotrigine. If you do stop for more than a few days, DO NOT restart at your current dose. Call your doctor to review your dosing schedule.

- MedlinePlus. Lamotrigine. Last revised January 15, 2019. Available at: https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a695007.html. Accessed October 10, 2019.

- Terao T, Ishida A, Kimura T, Yarita M, Hara T. Preventive effects of lamotrigine in bipolar II versus bipolar I disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. September 1, 2017; 78(8): e1000-e1005. Available at: www.psychiatrist.com/JCP/article/Pages/2017/v78n08/16m11404.aspx. Accessed October 10, 2019/

Notes: This article was originally published January 24, 2016 and most recently updated June 8, 2022.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders. This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.

Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

Antidepressant therapy with antidepressants. Lamictal and the problem of drug resistance | Yastrebov D.V.

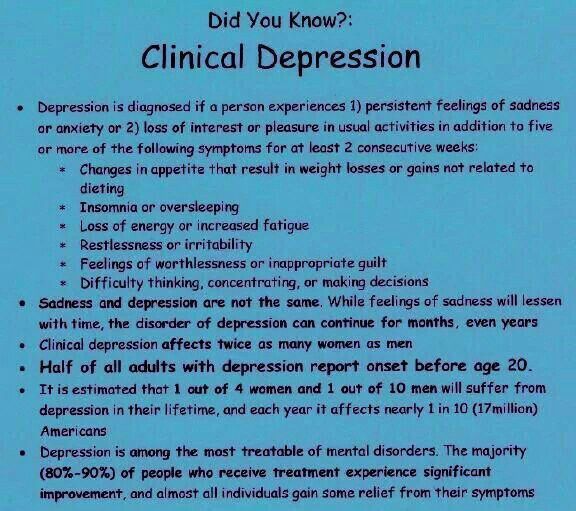

Introduction The initial prescription of antidepressants, the effectiveness of which has been proven in clinical studies, involves achieving a drug response rate of 50-75% within 3-4 weeks of therapy. From this it follows that from 25 to 50% of patients fall into a group of heterogeneous conditions, defined as "treatment-resistant depression" [I. M. Anderson et al., 2000; Schatzberg A.F., 2003]. Today there is no generally accepted definition of the phenomenon of drug resistance. For the most part, the use of this term implies the absence of a satisfactory response to treatment. However, the criteria used in clinical trials, which involve a rating system-based assessment of symptom dynamics as a result of therapy (eg, a 50% reduction in the total score of the HAMD1 scale), are of little use in everyday practice. As one of the reasons for this, one can mention that an improvement of this level is often not recognized by the patient as a positive outcome, which is confirmed by the discrepancy between subjective and objective ratings that is often found in clinical studies [A.J. Rush et al., 2006].

M. Anderson et al., 2000; Schatzberg A.F., 2003]. Today there is no generally accepted definition of the phenomenon of drug resistance. For the most part, the use of this term implies the absence of a satisfactory response to treatment. However, the criteria used in clinical trials, which involve a rating system-based assessment of symptom dynamics as a result of therapy (eg, a 50% reduction in the total score of the HAMD1 scale), are of little use in everyday practice. As one of the reasons for this, one can mention that an improvement of this level is often not recognized by the patient as a positive outcome, which is confirmed by the discrepancy between subjective and objective ratings that is often found in clinical studies [A.J. Rush et al., 2006].

The initial prescription of antidepressants, the effectiveness of which has been proven in clinical studies, involves achieving a drug response rate of 50-75% within 3-4 weeks of therapy. From this it follows that from 25 to 50% of patients fall into a group of heterogeneous conditions, defined as "treatment-resistant depression" [I.M. Anderson et al., 2000; Schatzberg A.F., 2003]. Today there is no generally accepted definition of the phenomenon of drug resistance. For the most part, the use of this term implies the absence of a satisfactory response to treatment. However, the criteria used in clinical trials, which involve a rating system-based assessment of symptom dynamics as a result of therapy (eg, a 50% reduction in the total score of the HAMD1 scale), are of little use in everyday practice. As one of the reasons for this, one can mention that an improvement of this level is often not recognized by the patient as a positive outcome, which is confirmed by the discrepancy between subjective and objective ratings that is often found in clinical studies [A.J. Rush et al., 2006].

From this it follows that from 25 to 50% of patients fall into a group of heterogeneous conditions, defined as "treatment-resistant depression" [I.M. Anderson et al., 2000; Schatzberg A.F., 2003]. Today there is no generally accepted definition of the phenomenon of drug resistance. For the most part, the use of this term implies the absence of a satisfactory response to treatment. However, the criteria used in clinical trials, which involve a rating system-based assessment of symptom dynamics as a result of therapy (eg, a 50% reduction in the total score of the HAMD1 scale), are of little use in everyday practice. As one of the reasons for this, one can mention that an improvement of this level is often not recognized by the patient as a positive outcome, which is confirmed by the discrepancy between subjective and objective ratings that is often found in clinical studies [A.J. Rush et al., 2006].

Other definitions based on the clinical assessment of the condition suggest an estimate of the number of unsuccessful treatments (2 or more). And finally, the third version of the definitions involves the persistence of depressive symptoms in the absence of success in achieving a state of remission as a result of the therapy (it should be noted that in this case the concepts of remission and drug response are combined) - M.R. Nelsen, D.L. Dunner, 1993; M.E. Thase, P.T. Ninan, 2002.

And finally, the third version of the definitions involves the persistence of depressive symptoms in the absence of success in achieving a state of remission as a result of the therapy (it should be noted that in this case the concepts of remission and drug response are combined) - M.R. Nelsen, D.L. Dunner, 1993; M.E. Thase, P.T. Ninan, 2002.

Any of the listed approaches for determining drug resistance is justified only for patients for whom there were no diagnostic inconsistencies and for whom adequate therapy was initially prescribed. In these cases, one speaks of the so-called "true" resistance. However, there are other options in which the achieved drug response against the doctor's expectations can be assessed as insufficient. Among them can be named: an error in the choice of an antidepressant or its dosage; poor tolerance, which makes it impossible to use a specific drug in the appropriate dose, violations of compliance, and a number of others (Fig. 1). It is obvious that in these cases, sometimes defined as "pseudo-resistance" or "relative resistance", medical tactics are fundamentally different and should be aimed at overcoming or eliminating factors that interfere with the achievement of a drug response [H. E. Lehmann, 1974].

E. Lehmann, 1974].

After eliminating the signs that allow attributing the lack of a drug response to the account of "pseudo-resistance", the question arises of determining the "true" (absolute) resistance [D. Bird et al., 2002]. In contrast to the previously existing ideas about drug resistance, as a phenomenon of the atomic order, M. Thase and A. Rush (1997) proposed a dynamic multi-stage system for assessing therapy-resistant depression, which is currently widely used. This typology reflects the authors' idea of drug resistance as a stage concept that requires comparison of the entire set of previous therapeutic measures that did not lead to an improvement in the condition (Table 1).

More complex is the taxonomically organized European staged method for assessing drug resistance, partially echoing the approach of M. Thase and A. Rush. Each of the stages of resistance, instead of a serial number, has its own definition with the designation of groups of drugs and the terms of their therapy that did not lead to an improvement in the condition (Table 2).

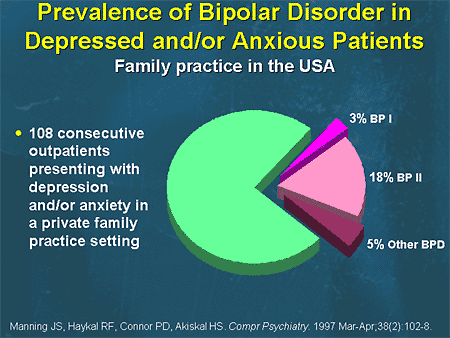

Variants of depressions,

therapy resistant

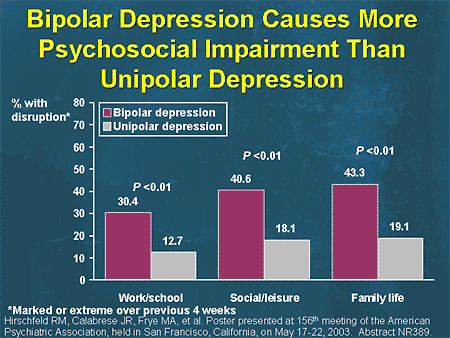

The issue of determining the clinical subtype of depression (psychotic, atypical, seasonal) is an important component in the management of this group of patients, since such differences may determine sensitivity to a particular therapy option. In addition, resistance to therapy may be due to an erroneous diagnosis with the definition of a unipolar variant of a depressive disorder in a patient with an undiagnosed bipolar course. Due to the fact that depressive phases in patients with bipolar disorder are clinically detected more often (including due to the greater attendance of patients with depressive symptoms), it is expected that up to half of patients with bipolar disorder can receive treatment according to therapeutic algorithms developed for unipolar depression. [S.N. Ghaemi et al., 1999]. As will be shown below, the question of the correct diagnosis of bipolar disorder is key in the appointment of therapy.

Coping methods

drug resistance

Identification of a case of drug resistance dictates to the doctor the need to change the tactics of managing the patient. At the first stage, the choice is made between two main options: changing the antidepressant or prescribing an additional drug to "enhance" the antidepressant effect of the main drug. Let's take a closer look at each of them.

At the first stage, the choice is made between two main options: changing the antidepressant or prescribing an additional drug to "enhance" the antidepressant effect of the main drug. Let's take a closer look at each of them.

Changing Therapy

Changing the drug is preferable in the event of a complete lack of response to therapy or in the presence of side effects requiring the withdrawal of the originally prescribed antidepressant. Despite the apparent obviousness of the fact that the change of an antidepressant that turned out to be ineffective should imply the choice of a “second-line” drug with a fundamentally different mechanism of action, there are separate data arguing the expediency of switching to a more potent drug of the same group. In particular, for the most commonly prescribed antidepressants - selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), it has been shown that the change of less potent drugs (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram) that did not improve the symptoms of depression to more potent ones (paroxetine, sertraline) gives a percentage of improvements similar to selective ones. serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (venlafaxine) and selective norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors (bupropion) up to 30% of cases. At the same time, the number of cases of early discontinuation of therapy due to developed side effects for "double-acting" drugs is 25% higher than for drugs of the SSRI group. Thus, the assumption that the lack of sensitivity of depressive symptoms to the initially prescribed antidepressant indicates the ineffectiveness of the entire class of drugs with a similar mechanism of action has not been confirmed to date [A.J. Rush et al., 2006]. These data, presented in the form of practical recommendations, show that when changing therapy, it is justified to choose a drug not with the largest number of cumulative mechanisms of action, but with the maximum potential in relation to the leading neurotransmitter system (for SSRIs, this is paroxetine (Paxil) and sertraline). At the same time, certain arguments can be given that do not allow defining this tactic as the main one.

serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (venlafaxine) and selective norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors (bupropion) up to 30% of cases. At the same time, the number of cases of early discontinuation of therapy due to developed side effects for "double-acting" drugs is 25% higher than for drugs of the SSRI group. Thus, the assumption that the lack of sensitivity of depressive symptoms to the initially prescribed antidepressant indicates the ineffectiveness of the entire class of drugs with a similar mechanism of action has not been confirmed to date [A.J. Rush et al., 2006]. These data, presented in the form of practical recommendations, show that when changing therapy, it is justified to choose a drug not with the largest number of cumulative mechanisms of action, but with the maximum potential in relation to the leading neurotransmitter system (for SSRIs, this is paroxetine (Paxil) and sertraline). At the same time, certain arguments can be given that do not allow defining this tactic as the main one. In particular, an increase in drug potential automatically means a decrease in tolerability. Thus, in patients who notice the occurrence of certain side effects even during first-line therapy, tactics aimed at enhancing the potential of the drug can lead to worse tolerability and a decrease in the level of drug compliance [Thase M.E., Rush A.J., 1997].

In particular, an increase in drug potential automatically means a decrease in tolerability. Thus, in patients who notice the occurrence of certain side effects even during first-line therapy, tactics aimed at enhancing the potential of the drug can lead to worse tolerability and a decrease in the level of drug compliance [Thase M.E., Rush A.J., 1997].

Antidepressant withdrawal policy

Discontinuation of drug antidepressant therapy (AD-therapy) may be accompanied by the occurrence of certain disorders, which are currently accepted to be classified as part of the "anti-adhesion discontinuation syndrome" (AD-AD cessation syndrome).

In earlier studies, the terms “AD withdrawal reaction” and “AD withdrawal syndrome” were more often used to denote pathological symptoms associated with antidepressant (AD) withdrawal [Rotschild, 1995; Dilsaver, 1984; Garner, 1993], which were later changed to emphasize the difference between these disorders and classical withdrawal, which already “reserved” these concepts for itself. However, until now, uncertainty remains in the terminological attribution of the same clinical manifestations, reflecting the opinion of a particular author about the advisability of considering them as withdrawal symptoms [Haddad, 2005].

However, until now, uncertainty remains in the terminological attribution of the same clinical manifestations, reflecting the opinion of a particular author about the advisability of considering them as withdrawal symptoms [Haddad, 2005].

Early descriptions of SPP AD appeared already in the course of clinical trials of the first ADs (imipramine) [Mann, 1959]. Subsequently, reports of similar disorders were given for almost all groups of AD: other tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), MAO inhibitors (MAOIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and other modern antidepressants [ Hadad, 2004]. It was revealed that the features and severity of SPP BP vary both in relation to different groups of drugs, and for representatives within the same class.

Despite the fact that usually SPP AD manifests itself within a few days after stopping the use of AD or reducing the dosage of the drug and is characterized by a short duration and relative mildness of manifestations, correct recognition if they occur is important, because. these conditions are associated with certain disturbances in daily activities, causing a marked decrease in performance, and their occurrence in a patient unaware of this possibility can lead to serious violations of drug compliance. Also, in some cases, SPP BP can take on a rather pronounced character, requiring hospitalization of the patient [Warner, 2006].

these conditions are associated with certain disturbances in daily activities, causing a marked decrease in performance, and their occurrence in a patient unaware of this possibility can lead to serious violations of drug compliance. Also, in some cases, SPP BP can take on a rather pronounced character, requiring hospitalization of the patient [Warner, 2006].

As the main measure to prevent the occurrence of SPP AD or minimize its manifestations, most authors declare the need to follow the prescribed regimen of taking the drug with the elimination of possible interruptions. If it is necessary to cancel blood pressure, it is advisable to follow the method of gradual dose reduction, taking into account the pharmacokinetic properties of a particular drug. The therapeutic value of the last recommendation, in our opinion, however, needs additional verification. According to the data of comparative studies, the gradual abolition of blood pressure allows to achieve an approximately two-fold decrease in the severity of SPP AD compared with one-stage [Van Geffen, 2005]. However, there are other data that show that the gradual withdrawal of the drug rather "blurs" the "rebound" symptoms throughout the entire period of withdrawal. If the manifestations of SPP BP are mild, this technique really makes it possible to additionally “smooth out” them, however, with a greater severity of violations, such tactics of “delaying” may be inappropriate [Yastrebov, 2007]. In addition, the result of gradual withdrawal does not guarantee an asymptomatic outcome of AD withdrawal.

However, there are other data that show that the gradual withdrawal of the drug rather "blurs" the "rebound" symptoms throughout the entire period of withdrawal. If the manifestations of SPP BP are mild, this technique really makes it possible to additionally “smooth out” them, however, with a greater severity of violations, such tactics of “delaying” may be inappropriate [Yastrebov, 2007]. In addition, the result of gradual withdrawal does not guarantee an asymptomatic outcome of AD withdrawal.

According to various sources, up to 50% of patients diagnosed with SPP AD discontinued the drug gradually [Barr, 1994; Pacheco, 169]. Among the factors associated with an increased risk of developing SPP AD, we can name episodes of reactions to the abolition of AD that have already been noted in the anamnesis. In this case, the risk of developing SPP BP increases to 75% [Black, 2000]. For such patients, when canceling AD, gradual withdrawal over 4–8 weeks is desirable, possibly under the “cover” of a short course of replacement therapy, which can be tranquilizers or AD with a different mechanism of action than the drug being withdrawn. These drugs, on the one hand, stop SPP BP, and on the other hand, allow the corresponding receptor subsystems (but not the concentration of the corresponding neurotransmitter) to return to the “pre-therapeutic” state (for example, when paroxetine is canceled - mirtazapine), which in most cases allows you to “cover up” the manifestations reactive symptomatology throughout its course up to complete regression [Warner, 2006].

These drugs, on the one hand, stop SPP BP, and on the other hand, allow the corresponding receptor subsystems (but not the concentration of the corresponding neurotransmitter) to return to the “pre-therapeutic” state (for example, when paroxetine is canceled - mirtazapine), which in most cases allows you to “cover up” the manifestations reactive symptomatology throughout its course up to complete regression [Warner, 2006].

Combination therapy

In the event that a certain positive shift in the clinical picture of depression is recorded, which, however, indicates only a partial response to therapy, and at the same time the tolerability of the initially prescribed antidepressant is assessed as satisfactory, it is proposed to use combination therapy with the addition of either another antidepressant ("dual therapy"). ”), or a drug of another class that enhances the effect of the main antidepressant (enhanced therapy). There are some differences between these two combination therapy options.

"Dual" therapy involves the addition of a second antidepressant to an existing monotherapy. At the same time, unlike the procedure for changing an antidepressant, its mechanism of action, if possible, should not overlap with that of the “primary” drug. An example is the combination of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram) or a selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor with a drug such as mirtazapine. However, this tactic has not been widely adopted for a variety of reasons. The main one is that this approach, despite the simplicity of its definition, is largely based on empirical experience and is difficult to rationally evaluate the effectiveness and formalize the assignment algorithm. To date, there are no comparable data on the effectiveness of various combinations of antidepressants; at the same time, the number of side effects, due to which patients stop treatment, increases significantly. Separately, it is necessary to specify the special care required in these cases in the choice of drugs to exclude undesirable drug interactions.

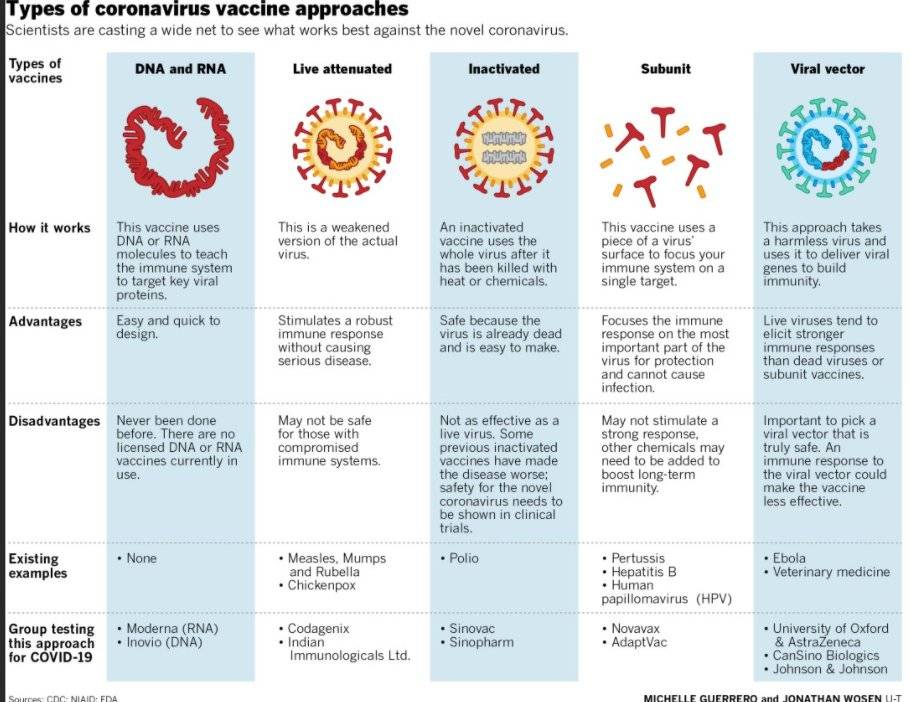

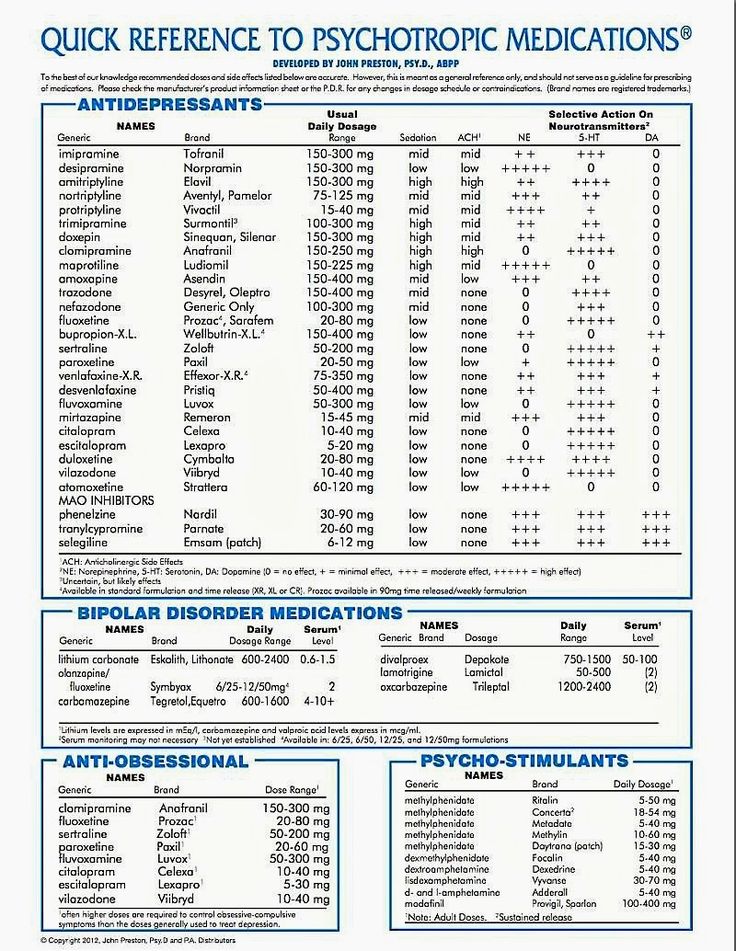

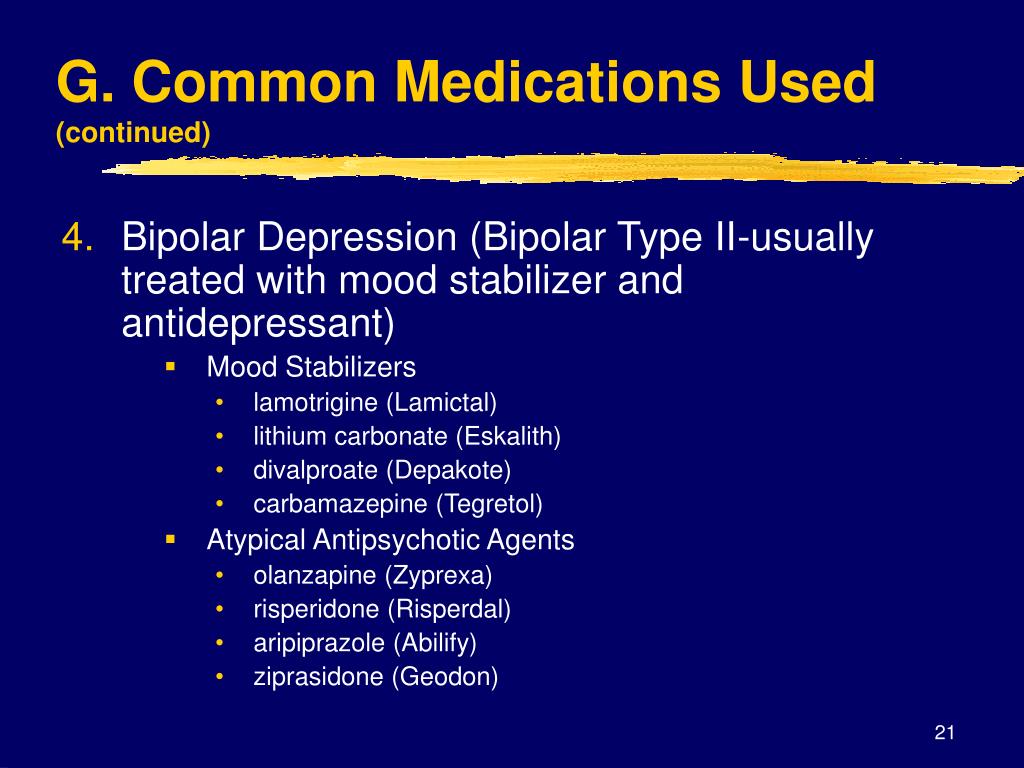

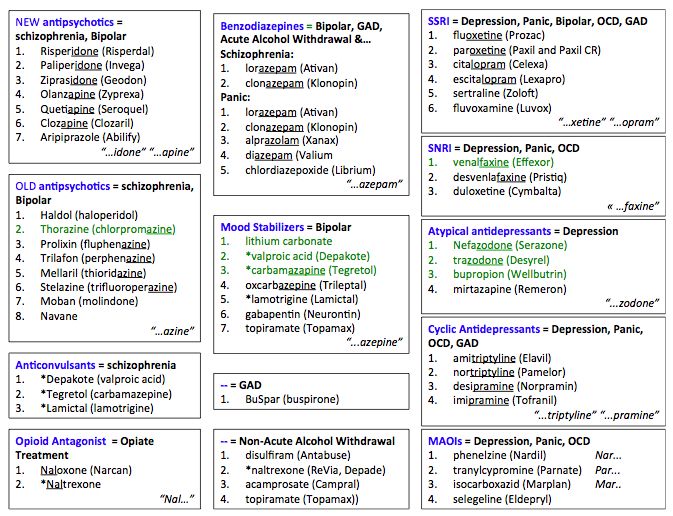

An enhanced version of combination therapy involves the appointment of an antidepressant, coupled with one of the antipsychotics, or with drugs from the group of mood stabilizers. The latter include lithium salts, carbamazepine, salts of valproic acid and lamotrigine (Table 3).

Limitations in the use of antidepressants

The choice of drugs for antidepressant therapy requires mandatory consideration of the characteristics of the clinical picture of an affective disease and its dynamics in general. So, R. El–Mallakh and A. Karippot (2006) indicate that the presence of a history of signs of a bipolar course makes the appointment of antidepressants alone undesirable due to the possibility of affect inversion, cycle acceleration and the appearance of prolonged irritable dysphoria.

Thus, it is suggested that antidepressant monotherapy is undesirable in patients with depression as part of bipolar disorder due to the possible worsening of the course of bipolar disorder [C. B. Nemeroff, 2001]. Official guidelines published by the American Psychiatric Association [APA Practice Guidelines, 2002] also recommend that antidepressants should not be used as monotherapy in these patients at all initially. Instead, a one-time appointment of at least combination therapy is proposed; it is recommended to use lithium salts or Lamictal (lamotrigine) along with antidepressants as first-line agents at the stage of active therapy. These recommendations are based on recent studies of depression in bipolar disorder defined as resistant to prior therapy (stage II resistance). It has been shown that the appointment of such patients with mood stabilizers (Lamictal (lamotrigine) at doses up to 150-250 mg per day) for combination with antidepressants can significantly increase the level of drug response in comparison with atypical antipsychotics (risperidone) and reduce the likelihood of relapse within a year (with 5% for risperidone to 24% for Lamictal (lamotrigine)) [A. A. Nierenberg et al.

B. Nemeroff, 2001]. Official guidelines published by the American Psychiatric Association [APA Practice Guidelines, 2002] also recommend that antidepressants should not be used as monotherapy in these patients at all initially. Instead, a one-time appointment of at least combination therapy is proposed; it is recommended to use lithium salts or Lamictal (lamotrigine) along with antidepressants as first-line agents at the stage of active therapy. These recommendations are based on recent studies of depression in bipolar disorder defined as resistant to prior therapy (stage II resistance). It has been shown that the appointment of such patients with mood stabilizers (Lamictal (lamotrigine) at doses up to 150-250 mg per day) for combination with antidepressants can significantly increase the level of drug response in comparison with atypical antipsychotics (risperidone) and reduce the likelihood of relapse within a year (with 5% for risperidone to 24% for Lamictal (lamotrigine)) [A. A. Nierenberg et al. , 2006].

, 2006].

Separate attention should be paid to the possibility of using drugs that do not belong to the class of antidepressants for monotherapy of depression in bipolar disorder. Existing data confirm the possibility of using some mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics in this capacity (Table 4) [K. Fountoulakis et al., 2007].

It must be noted that the appointment of some of the above drugs for long-term therapy (atypical antipsychotics, especially olanzapine), despite proven effectiveness, may be undesirable due to their inherent undesirable side effects, mainly manifested with long-term use (weight gain, metabolic disorders) .

Long-term prophylactic monotherapy with lamotrigine for bipolar depression

Experience with long-term use of Lamictal has shown that this drug is equally effective in bipolar I and II disorders [Geddes, 2009]. The advantages of Lamictal, which justify its use at the stage of long-term preventive therapy, are: the effect on the residual manifestations of depression, the absence of rebound symptoms upon withdrawal, and the minimal presence of side effects [Calabrese, 2008]. Of particular value to the drug is the absence of the ability to cause weight gain with long-term use, which may justify the need to transfer patients with a tendency to obesity from other drugs (including lithium) to it [Bowden, 2006].

Of particular value to the drug is the absence of the ability to cause weight gain with long-term use, which may justify the need to transfer patients with a tendency to obesity from other drugs (including lithium) to it [Bowden, 2006].

Supplement

Article sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline

1 HAMD: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

Literature

1. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder (Revision). Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159 (April suppl).

2. Anderson I. M., Nutt D. J., Deakin J. F. W. Evidence–based guidelines for treating depressive illness with antidepressants: a revision of the 1993 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol (2000), 14, 3–20.

3. Barr L. C., Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H. Physical symptoms associated with paroxetine discontinuation. Am J Psychiatry (1994), 151, 289.

3. Bird D., Haddad P. M., Dursun S. M. An overview of the definition and management of treatment–resistant depression. Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bulteni 2002; 12:92–101.

4. Black K., Shea, C., Dursun, S., Kutcher, S. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: proposed diagnostic criteria. J Psychiatry NeuroSci (2000), 25, 255–261.

5. Calabrese JR, Huffman RF, White RL, Edwards S, Thompson TR, Ascher JA, et al. Lamotrigine in the treatment of bipolar depression: results of five double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials. Bipolar Disord 2008; 10:323–33.

6. Charles L. Bowden, M.D. Joseph R. Calabrese, M.D. Terence A. Ketter, M.D. Gary S. Sachs, M.D. Robin L. White, M.S. Thomas R. Thompson, M.D. Impact of Lamotrigine and Lithium on Weight in Obese and Nonobese Patients With Bipolar I Disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1199–1201.

7. Dilsaver S. C., Greden, F. J. Antidepressant withdrawal phenomena. Biol Psychiatry (1984), 19, 237–256.

8. Ghaemi S. N., Sachs G. S., Chiou A. M., Pandurangi A. K., Goodwin K. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord 1999;52:135–44.

9. El–Mallakh R. S., Karippot A. Chronic depression in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Aug;163(8):1337–1341; quiz 1478.

10. Fountoulakis K. N., Vieta E., Siamouli M. et al. Treatment of bipolar disorder: a complex treatment for a multi-facet disorder. Annals of General Psychiatry 2007, 6:27 (http://www.annals-general-psychiatry.com/content/6/1/27).

11. Garner E.M., Kelly, M.W., Thompson, D.F. Tricyclic antidepressant withdrawal syndrome. Ann Pharmacother (1993), 27, 1068–1072.

12. Haddad P.M. Do antidepressants cause dependence? Epidemiologie e Psychiatria Sociale (2005), 14, 58–62.

13. Haddad P. M., Anderson, I., Rosenbaum, J. (2004). Antidepressant discontinuation syndromes. In Haddad P., Dursun, P., Deakin, B. (Ed.), Adverse syndromes and psychiatric drugs: a clinical guide. (pp. 183–205). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

(pp. 183–205). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

14. John R. Geddes, Joseph R. Calabrese and Guy M. Goodwin. Lamotrigine for treatment of bipolar depression. The British Journal of Psychiatry (2009) 194, 4–9.

15. Lehmann H. E. Therapy–resistant depressions–a clinical classification. Pharmakopsychiatr Neuropsychopharmakol 1974;7:156–63.

16. Mann A. M., MacPherson, A. Clinical experience with imipramine (G22355) in the treatment of depression. Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal (1959), 4, 38–47.

17. Messenheimer J., Mullens E. L., Giorgi L., Young F. Safety of adult clinical trial experience with lamotrigine. Drug Safety 1998, 18: 281–296.

18. Nelsen M. R., Dunner D. L. Clinical and differential diagnostic aspects of treatment-resistant depression. Journal of Psychiatric Research. Vol. 29, 1, January–February 1995, 43–50.

19. Nemeroff C. B., Evans D. L., Gyulai L., Sachs G. S., Bowden C. L., Gergel I. P., Oakes R., Pitts C. D.: Double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of imipramine and paroxetine in the treatment of bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:906–912

Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:906–912

20. Nierenberg A. A., Ostacher M. J., Calabrese J. R., Ketter T. A., Marangell L. B., Miklowitz D. J., Miyahara S., Bauer M. S., Thase M. E., Wisniewski S. R., Sachs G. S. Treatment–resistant bipolar depression: a STEP–BD equipoise randomized effectiveness trial of antidepressant augmentation with lamotrigine, inositol, or risperidone. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Feb;163(2):210–6.

21. Pacheco L., Malo, P., Aragues, E., Etxebeste, M. More cases of paroxetine withdrawal symptoms. Brit J Psychiatry (169), 169, 384.

22. Rotschild A. J. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor–induced sexual dysfunction: efficacy of a drug holiday. Am J Psychiatry (1995), 152, 1514–1516.

23. Rush A. J., Kraemer H. C., Sackeim H. A., et al. Report by the ACNP Task Force on response and remission in major depressive disorder. neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1841–1853.

24. Rush A. J., Trivedi M. H., Wisniewski S. R., Stewart J. W., Nierenberg A. A., Thase M. E., Ritz L., Biggs M. M., Warden D., Luther J. F., Shores–Wilson K., Niederehe G., Fava M. Bupropion–SR , sertraline, or venlafaxine–XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006 Mar 23;354(12):1231–1242.

E., Ritz L., Biggs M. M., Warden D., Luther J. F., Shores–Wilson K., Niederehe G., Fava M. Bupropion–SR , sertraline, or venlafaxine–XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006 Mar 23;354(12):1231–1242.

25. Santos M. A., Rocha F. L., Hara C. Efficacy and Safety of Antidepressant Augmentation With Lamotrigine in Patients With Treatment–Resistant Depression: A Randomized, Placebo–Controlled, Double–Blind Study. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008; 10(3): 187–190.

26. Schatzberg A. F., Cole J. O., DeBattista C. Manual of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2003:42.

27. Souery D., Amsterdam J., de Montigny C., Lecrubier Y., Montgomery S., Lipp O., Racagni G., Zohar J., Mendlewicz J. Treatment resistant depression: methodological overview and operational criteria. European neuropsychopharmacology : the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology 1999;9(1–2):83–91.

28. Thase M. E., Rush A. J. When at first you don’t succeed: sequential strategies for antidepressant nonresponders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:23–29.

E., Rush A. J. When at first you don’t succeed: sequential strategies for antidepressant nonresponders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:23–29.

29. Thase M. E., Ninan P. T. New goals in the treatment of depression: moving towards recovery. Psychopharma Bull. 2002;36(Suppl 2):24–35.

30. Van Geffen E.C., Hugtenburg, J.G., Heerdink, E.R., Van Hulten R.P., Egberts, A.C.G. Discontinuation symptoms in users of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in clinical practice: tapering versus abrupt discontinuation. 2005.

31. Warner C.H., Bobo, W., Warner, C., Reid, S., Rachal., J. Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome. Am Fam Physician (2006), 74(3), 449–456.

32. Yastrebov D.V., Alkeeva–Kostycheva, E.A. Comparison of the results of gradual and simultaneous withdrawal of benzodiazepine tranquilizers taken in therapeutic doses. Russian Journal of Psychiatry, No. 1, 2008.

updated recommendations of the British Association for Psychopharmacology

01/08/2017

Treatment outcomes for bipolar disorder (BD) have been, and still are, modest. However, British experts believe that there is significant potential for improvement if therapy is carried out in accordance with modern recommendations based on evidence-based medicine. This summer, the British Association for Psychopharmacology presented the third update of its evidence-based BD treatment guideline, the key provisions of which we would like to acquaint our readers with.

However, British experts believe that there is significant potential for improvement if therapy is carried out in accordance with modern recommendations based on evidence-based medicine. This summer, the British Association for Psychopharmacology presented the third update of its evidence-based BD treatment guideline, the key provisions of which we would like to acquaint our readers with.

The quality of the evidence on which recommendations were made was rated from I to IV (descending), and the strength of the recommendations, respectively, by the number of asterisks, from very low (*) to high (****). The provisions, the observance of which, according to the authors, should be the most stringent, they marked with the letter S.

Acute manic episode

Most patients with manic states require short-term medical treatment in an adequate clinical setting (I). A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrated the efficacy of a range of drugs (I). When choosing a drug, it is necessary to take into account its effectiveness and the risk of developing adverse events.

When choosing a drug, it is necessary to take into account its effectiveness and the risk of developing adverse events.

There is currently no alternative psychotherapeutic treatment for acute mania.

For patients not receiving long-term treatment with BR . In the case of severe manic episodes, oral dopamine receptor antagonists, which provide a rapid anti-manic effect, should be considered (****). Thus, a systematic analysis of clinical trial data indicates that haloperidol, olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine are highly effective for the short-term relief of symptoms of acute mania. An alternative is valproate, which has a lower risk of developing adverse motor reactions, but they should not be prescribed to women of childbearing age due to the unacceptable risk of a teratogenic effect and a slowdown in the child's intellectual development in the future. It is also possible to use aripiprazole, other antagonists and partial agonists of dopamine receptors, carbamazepine and lithium preparations.

If an agitated patient requires parenteral therapy for behavioral modification without full consent, dopamine antagonists/partial agonists and GABAergic drugs (benzodiazepines) should be used (S).

It is recommended to prescribe the minimum effective dose of drugs (S). Do not increase the dose of dopamine receptor antagonists just to achieve a sedative effect (S).

For less severe, non-psychotic patients with mania and hypomania, treatment can be extrapolated from mania practice (IV).

In order to quickly induce sleep in agitated hyperactive patients, it is worth considering the additional prescription of GABAergic drugs (***).

Whenever possible, the choice of therapy should be based on the patient's previous experience and preferences.

Antidepressants (that is, medicines approved for the treatment of unipolar depression) during a manic episode are usually discontinued by tapering the dose (**).

Long-term therapy with BR should be considered if treatment of mania has been successful (S).

For patients with a manic episode that developed during long-term therapy. If the current condition is caused by insufficient effectiveness of basic therapy, it is recommended to increase the dose of the drug used to the maximum well tolerated (S). Increasing the dose of dopamine receptor antagonists and partial agonists or valproate may be sufficient to relieve manic symptoms (IV).

In the case of treatment with lithium preparations, it should be ensured that its concentration in the blood serum is in the target range. Try increasing the dose until a concentration of 0.6-0.8 mmol/L (mEq/L) is reached. A concentration of 0.8-1.0 mmol/L may be more effective, but long-term maintenance is associated with an increased risk of side effects (I).

If the patient is on lithium, consider adding a dopamine receptor antagonist/partial agonist or valproate to therapy (****).

If the manic episode was the result of the patient's non-compliance with medical recommendations, the cause should be determined and adequate measures taken (S). For example, if insufficient adherence to therapy is due to adverse events, it is necessary to reduce the dose of the drug (if the side effect is dose-dependent) or transfer the patient to an alternative treatment regimen with better tolerance. If non-compliance is deliberate and not related to tolerability of therapy, long-term use of lithium preparations is not indicated due to the risk of developing mania or depression if they are discontinued (I).

For example, if insufficient adherence to therapy is due to adverse events, it is necessary to reduce the dose of the drug (if the side effect is dose-dependent) or transfer the patient to an alternative treatment regimen with better tolerance. If non-compliance is deliberate and not related to tolerability of therapy, long-term use of lithium preparations is not indicated due to the risk of developing mania or depression if they are discontinued (I).

If symptoms cannot be controlled with optimal doses of first-line drugs and/or the manic state is extremely severe, another treatment should be added. Consider a combination of lithium or valproate with a dopamine antagonist/partial agonist (****).

Clozapine is considered in more refractory cases (**).

Electroconvulsive therapy may be considered in patients with very severe or treatment-resistant mania, in cases where the patient prefers this type of treatment, in severe mania during pregnancy (***).

Manic or hypomanic episode with mixed features. DSM-5 proposes the term "mixed traits" instead of the definition of "mixed episode" used in DSM-IV. A secondary analysis of the results of studies in relation to the effectiveness of the treatment of mixed episodes indicates that the treatment of episodes such as manic is adequate.

DSM-5 proposes the term "mixed traits" instead of the definition of "mixed episode" used in DSM-IV. A secondary analysis of the results of studies in relation to the effectiveness of the treatment of mixed episodes indicates that the treatment of episodes such as manic is adequate.

Use of psychoactive substances. If substance use may have contributed to a manic or hypomanic episode, consider medical support for drug withdrawal (S).

Termination of therapy for an acute episode. Drug withdrawal should be planned based on the need for further long-term maintenance treatment (S). Many drugs are effective not only for the treatment of manic states, but also for the prevention of their relapse (I).

The dose of drugs used only for the intensive treatment of mania, upon reaching a complete remission, is gradually reduced (for 4 weeks or more) until complete withdrawal (IV). Remission often occurs after 3 months, but mood stabilization may take 6 months or more.

Any drugs used additionally for symptomatic treatment (sedation, sleep induction) should be discontinued immediately after improvement (S).

Acute depressive episode

Network meta-analysis of RCTs showed the effectiveness of a limited range of drugs with different pharmacodynamics and different evidence bases.

There is no consensus on the appropriateness of the use of antidepressants, that is, drugs that are effective in unipolar depression (IV).

Most of the data come from studies involving patients with type I BD, but it seems logical to extrapolate them to people with type II BD.

For patients not receiving long-term BR treatment. Consider quetiapine, lurasidone, or olanzapine (***). An important benefit of dopamine receptor antagonists is their antimanic properties (I).

The use of antidepressants in BD is currently not well understood. Only the combination of fluoxetine with olanzapine has the necessary evidence base for BD (***). The widespread use of other antidepressants in patients with BD is the result of an extrapolation of data obtained in the treatment of unipolar depression. However, when prescribing antidepressants to patients with a history of mania, anti-manic agents (dopamine receptor antagonists, lithium preparations, valproates) should be added to them (S).

The widespread use of other antidepressants in patients with BD is the result of an extrapolation of data obtained in the treatment of unipolar depression. However, when prescribing antidepressants to patients with a history of mania, anti-manic agents (dopamine receptor antagonists, lithium preparations, valproates) should be added to them (S).

Initial therapy with lamotrigine (with gradual dose escalation) should be considered, usually as an adjunct to drugs to prevent relapse of mania (****).

Electroconvulsive therapy should be considered in patients with increased risk of suicide, treatment resistance, psychosis, severe depression during pregnancy, or life-threatening exhaustion (***). If possible, reduce previous polypharmacy, which can cause an increase in the seizure threshold.

If symptoms of depression are mild, despite a limited evidence base, lithium may be used, especially as a preparation for long-term treatment (**).

Family CBT or Interpersonal Rhythm Therapy should be considered as adjunctive treatment if possible, as this may help shorten the duration of an acute episode (**).

For patients with a depressive episode that developed during long-term therapy. It is necessary to ensure that the current long-term treatment regimen is able to prevent the relapse of a manic state (lithium preparations, valproates, dopamine receptor antagonists/partial agonists), to evaluate the adequacy of drug doses and / or serum lithium concentration (S). If possible, current stressors should be eliminated.

If the patient does not respond to the optimization of long-term treatment, and the symptoms of depression are sufficiently pronounced, it is necessary to start the treatment indicated in the paragraph above. The following are recommendations for the treatment of resistant depression.

Drug choice for a depressive episode. Preferable treatment options cannot be determined based on the available studies (IV).

In the treatment of depression, there is a risk of transition to a manic state or unstable mood (I). And although such a phase change is characteristic of the disease itself, with monotherapy with antidepressants, the risk increases. Non-selective monoamine reuptake inhibitors (venlafaxine, duloxetine, amitriptyline, and imipramine) are more likely to induce mania than selective drugs, especially selective serotonin (II) reuptake inhibitors. The risk of developing a manic state while taking antidepressants in combination with antimanic drugs is minimal (I). If an antidepressant is prescribed as monotherapy for type II BD, dose escalation should be gradual and closely monitored by the clinician for early management of adverse reactions such as hypomania, comorbidity, or agitation (IV).

Non-selective monoamine reuptake inhibitors (venlafaxine, duloxetine, amitriptyline, and imipramine) are more likely to induce mania than selective drugs, especially selective serotonin (II) reuptake inhibitors. The risk of developing a manic state while taking antidepressants in combination with antimanic drugs is minimal (I). If an antidepressant is prescribed as monotherapy for type II BD, dose escalation should be gradual and closely monitored by the clinician for early management of adverse reactions such as hypomania, comorbidity, or agitation (IV).

In contrast to the widespread use of antidepressants, lamotrigine is rarely used outside of specialized centers, despite its effectiveness in type I BD and the possibility of use in type II BD.

Long-term therapy should be considered after successful treatment of a depressive episode (S).

Withdrawal of antidepressants. The possibility of gradual withdrawal of antidepressants is considered after achieving complete remission (IV). Depressive episodes in BD are usually shorter than in unipolar depression (I). In the absence of indications for prolongation of therapy, it is worth canceling the antidepressant no earlier than 12 weeks after the start of remission (*). Longer treatment with antidepressants is justified if their withdrawal causes a relapse in the patient.

Depressive episodes in BD are usually shorter than in unipolar depression (I). In the absence of indications for prolongation of therapy, it is worth canceling the antidepressant no earlier than 12 weeks after the start of remission (*). Longer treatment with antidepressants is justified if their withdrawal causes a relapse in the patient.

Treatment of resistant depression. BD patients with depression may show relative or even marked resistance to treatment (I). This means that the patient does not respond to treatment not only with antidepressants, but also with quetiapine, olanzapine, lurasidone and lamotrigine both as monotherapy and in combinations. The evidence base for the treatment of such patients with BD is extremely scarce. Electroconvulsive therapy may be a treatment option (***). It is possible to extrapolate the experience of treating unipolar depression using augmentation strategies. Coverage with anti-manic drugs such as lithium, valproate, dopamine antagonists/partial agonists (S) is needed.

Psychosocial therapy as initial treatment. There is very little evidence of the effectiveness of psychotherapy alone (without medication) in the treatment of acute bipolar depression. More evidence is needed that this approach is effective (IV).

Long-term treatment

Long-term treatment should be considered even after one severe manic episode, i.e. type I BD (***).

Without active consent to long-term treatment, treatment adherence may be low (I). Extended treatment should be considered, including psychoeducation, motivational and family support, especially in the initial stages of the disease, to model the patient's behavior and help him adhere to the regimen (***).

If the patient has been successfully treated for several years, continued therapy is recommended due to the high risk of relapse (***).

Recommendations for the treatment of type I BD can be extrapolated to type II BD as clinical studies show similar efficacy (**).

Long-term treatment strategies. Currently, continuous rather than intermittent oral therapy is the preferred relapse prevention strategy.

A network meta-analysis of studies evaluating long-term therapy showed the effectiveness of a limited range of drugs with different pharmacodynamics and different evidence bases in preventing relapses of mania: lithium preparations, olanzapine, quetiapine, long-acting injectable risperidone and valproates. Lamotrigine, lithium, quetiapine, and lurasidone have been shown to be effective in preventing recurrence of depressive episodes.

Although relatively few patients remain in such studies for 6 months or more, there is strong evidence of a high efficacy of lithium in preventing relapse in patients who have not experienced an early response to therapy with these drugs (I).

Short-term addition of other drugs (GABA receptor modulators or antagonists/partial agonists of dopamine receptors) is necessary if a stressor is likely or present, early symptoms of relapse (especially insomnia) or severe anxiety (IV). It is worth considering the possibility of providing the patient with these drugs in advance, instructing him on the cases in which they should be used (*). Increasing the doses of long-term therapy drugs instead of additional drugs may also be effective (*).

It is worth considering the possibility of providing the patient with these drugs in advance, instructing him on the cases in which they should be used (*). Increasing the doses of long-term therapy drugs instead of additional drugs may also be effective (*).

Due to the fact that the optimal strategy for long-term treatment has not yet been determined, clinicians and patients are involved in clinical studies designed to answer key therapeutic questions (S).

Choice of drug for long-term therapy. In addition to studies on relapse prevention, analysis of treatment results in real clinical practice indicates the effectiveness of such drugs: lithium > valproate > olanzapine > quetiapine > carbamazepine (I).

It is recommended to consider lithium preparations as monotherapy (****). Lithium monotherapy is effective in preventing relapses of manic, depressive and mixed states (I), has a greater evidence base for the prevention of new episodes compared to other agents (I) and a better studied long-term safety profile (I). According to RCTs and observational studies, patients with BD who use lithium preparations are less at risk of suicide and self-harmful behavior (I).

According to RCTs and observational studies, patients with BD who use lithium preparations are less at risk of suicide and self-harmful behavior (I).

In the treatment of lithium, biochemical monitoring, including the determination of its concentration in blood serum, is mandatory (S). The target range is 0.6-0.8 mmol/L. Lithium concentrations above 0.8 mmol/L are associated with an increased risk of impaired renal function, especially in women (I). Monitoring of lithium concentration in somatically healthy patients should be carried out at intervals of 3 months in the first year of treatment and 6 months thereafter (S).

If lithium is ineffective, poorly tolerated, or non-compliant, other treatment options should be considered: valproate, dopamine antagonists/partial agonists (****).

Often valproates are put on the same level with lithium as "mood stabilizers". The evidence base based on the results of controlled clinical trials is weaker, however, data from real practice indicate a greater effectiveness of valproates compared to other drugs (I). Risk factors in women have been discussed above.

Risk factors in women have been discussed above.

Additional data obtained from studies on the treatment of acute episodes. If a patient experiences a sustained remission of a manic or depressive episode while taking any drug, this may be a reason to use this drug as long-term monotherapy (IV). At the same time, preference will probably be given to dopamine receptor antagonists due to their effectiveness in short-term use, however, the possibility of using lithium preparations as a better alternative should also be considered (IV).

Carbamazepine as a maintenance treatment is less effective than lithium preparations, but can sometimes be used as monotherapy when lithium is ineffective, especially in patients without classic episodes of euphoric mania (II). The drug seems to be effective mainly only for the prevention of relapses of manic states (I). Do not forget about drug interactions, which are a big problem in the treatment of carbamazepine. One might consider oxcarbazepine, which is less prone to such interactions (I).

If mania relapse prevention is needed, but the patient is not following oral medication recommendations, or parenteral route of administration is preferred, long-acting drugs should be considered (**). There are a large number of long-acting dopamine receptor antagonists/partial agonists such as fluphenazine decanoate, haloperidol decanoate, olanzapine pamoate, risperidone microspheres, paliperidone palmitate, and aripiprazole monohydrate. In RCTs, only risperidone (II) has been shown to be effective. The use of other drugs is based on the class efficacy of dopamine antagonists/partial agonists, extrapolation of the results of their use in oral form and clinical experience (IV).

Lamotrigine and quetiapine can be considered as monotherapy for type II BD (***). Type I BD usually requires a combination of lamotrigine with a long-term antimanic drug (IV).

Insufficient efficacy of monotherapy. If a patient fails to respond to monotherapy and subthreshold symptoms or relapses persist, long-term combination therapy is considered. When it comes to symptoms or relapses of mania, a combination of two predominantly anti-manic drugs (i.e., lithium, valproate, dopamine antagonists/partial agonists) would be logical (IV). In case of persisting symptoms or recurrence of depression, a combination of lithium, lamotrigine, quetiapine, lurasidone, or olanzapine (IV) may be appropriate.

When it comes to symptoms or relapses of mania, a combination of two predominantly anti-manic drugs (i.e., lithium, valproate, dopamine antagonists/partial agonists) would be logical (IV). In case of persisting symptoms or recurrence of depression, a combination of lithium, lamotrigine, quetiapine, lurasidone, or olanzapine (IV) may be appropriate.

The role of antidepressants in the long-term treatment of BD has not been studied in RCTs, but their long-term use appears to be effective in some patients (**).

If clozapine has been shown to be effective in the treatment of resistant mania, continued use is considered (**).

Supportive electroconvulsive therapy may be considered in patients who respond well to it during an acute episode but respond poorly to oral medications (*).

Consider adding psychotherapy if subthreshold symptoms are present (**).

Fast cycling. Conditions that contribute to rapid cycling, such as hypothyroidism or substance use, should be identified and addressed (**).

Gradual withdrawal of antidepressants should also be considered as they may cause cycling (**).

There is no specific treatment for rapid cycling. Many patients with this often debilitating form of BD require a combination of drugs. The countercyclical effect of therapy is evaluated in dynamics over a period of six months or more by monitoring the patient's mood. Ineffective drugs are canceled to avoid unnecessary polypharmacy (S).

Cancellation of long-term treatment . After discontinuation of drugs, there is a risk of relapse even after years of stable remission (II). Thus, the decision to discontinue treatment should be made after assessing the potential risks (S).

The gradual withdrawal of any drug should take at least 4 weeks, and longer if possible (S). Abrupt withdrawal of lithium preparations is fraught with early relapse of mania (I).

Discontinuation of drugs must not lead to termination of the patient's follow-up. It is necessary to continue monitoring and develop a plan to recognize and eliminate early signs of a relapse of a manic or depressive state (S).

Specific psychosocial interventions. Psychosocial interventions may improve treatment outcomes, reduce subthreshold symptoms, and reduce the risk of relapse (II). Psychoeducation is an important component of good clinical practice, as without it clinical interaction cannot be effective (S).

Various forms of psychotherapy (family therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal rhythm therapy) have been studied to prevent relapse. Psychological interactions are more effective in the initial stages of the disease (I).

Functional impairment in BD patients may require the use of cognitive and functional remediation strategies (II).

Patient groups provide the patient with support and additional information about BD and its treatment (IV).

Treatment of alcoholism in patients with BD

In alcoholics, even a modest reduction in alcohol consumption can improve health (I).

To reduce alcohol consumption, the patient should be offered naltrexone or nalmefene in addition to a behavioral therapy program (**).

If taking naltrexone has not helped the patient stay sober, acamprosate is recommended (**).

If the patient wants to remain sober, but acamprosate and naltrexone do not help, disulfiram is considered. However, the patient should be aware of the risks associated with the use of disulfiram and the need to monitor his mood (*).

Treatment of comorbid borderline personality disorder in patients with BD

Patients with comorbidity require treatment for both disorders. In this regard, one should not give preference only to medical treatment (carried out in BD) or only psychotherapy (indicated in borderline conditions) (S). In the absence of appropriate indications, there is no need to cancel or suspend adequate therapy for BD or borderline personality disorder.

Although there are few data supporting the effectiveness of medical treatment of borderline conditions, mood instability common to both pathological conditions can be successfully treated with drugs (lamotrigine, lithium preparations, olanzapine, risperidone, aripiprazole and quetiapine), which improves the course of borderline disorder .

Treatment of anxiety and other comorbid disorders in patients with BD

Co-occurring anxiety disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and substance abuse are treated according to relevant clinical guidelines (*).

Antidepressants should be used with caution (S).

Treatment of BR in selected groups of patients

Manic states in children and adolescents. Aripiprazole is preferred because it is approved for the treatment of type I BD in adolescents (over 13 years of age) (***). In other cases, it is worth adhering to the recommendations for the treatment of BD in adults. There is evidence that olanzapine and risperidone are effective in adolescents (**).

Children should be given adequate doses of drugs (S). It is necessary to be aware of the increased risk of side effects, in particular the possible weight gain (S).

Bipolar depression in children and adolescents. Considers medication and psychotherapy based on adult treatment data (*).

Antidepressants are more likely to cause mania in children and adolescents than in adults (II).

Long-term treatment is recommended in young patients, as relapses and mood instability can have a detrimental effect on the formation of cognitive and emotional functions (S).

Elderly patients . If obvious side effects are observed when using normal doses of psychotropic drugs, a dose reduction is considered (*).

Women who can become pregnant. Valproate and carbamazepine may be teratogenic (I). Given the risk/benefit ratio, valproate is contraindicated in women who may become pregnant (I).

Concerns about the association of lithium intake and the development of heart defects appear to be unfounded (II).

Since at least 50% of pregnancies today are unplanned, family planning counseling should be provided to patients whenever possible (S).

Pregnancy and postpartum period. Dopamine antagonists/partial agonists, antidepressants, lamotrigine and lithium preparations are not teratogenic or the risk is very low. However, it should be remembered that the risk of new drugs is always unknown, so they should be used with caution.

However, it should be remembered that the risk of new drugs is always unknown, so they should be used with caution.