Is greg louganis still alive

Greg Louganis Proved What Is Possible For Athletes Living With HIV

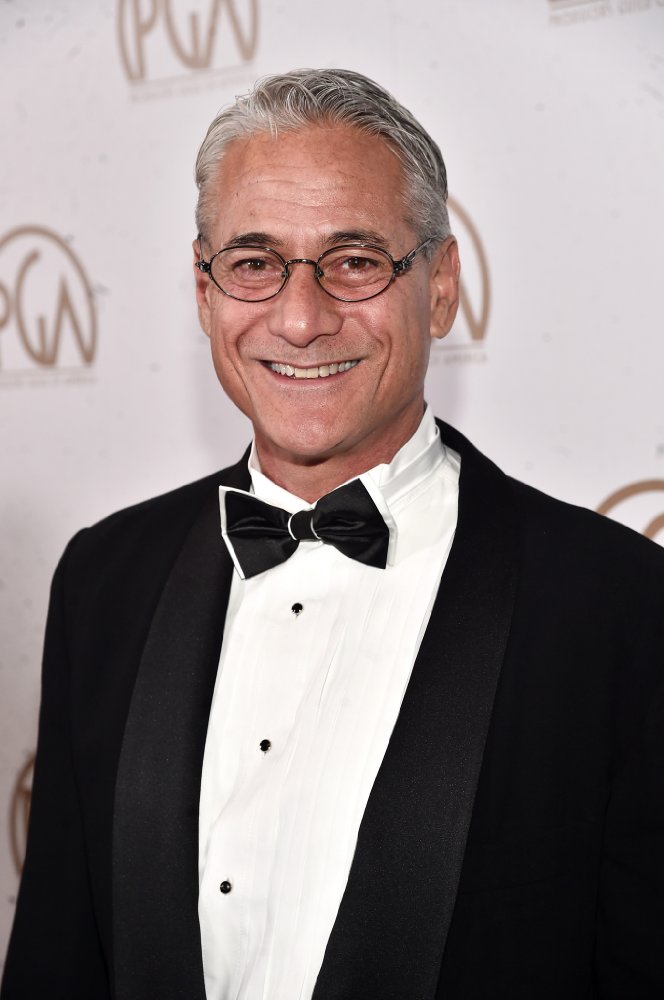

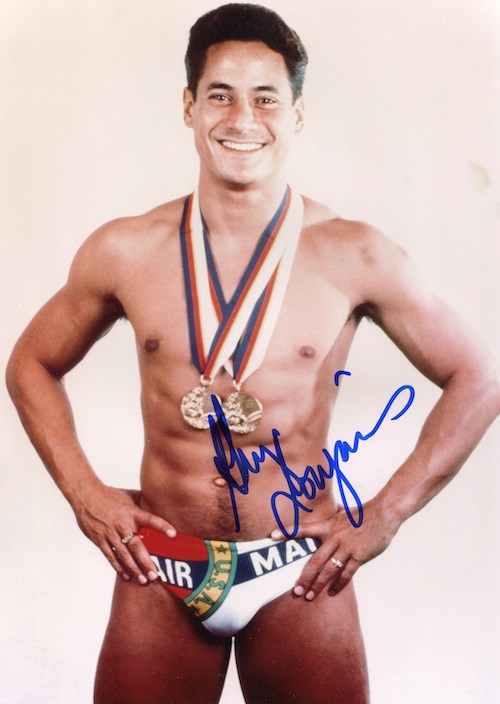

The next time you think about what HIV looks like, think about Greg Louganis winning two Gold medals at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul.

He became the first man and only the second diver in Olympic history to sweep both diving events in two consecutive Olympics—and he did it six months after learning that he was living with HIV. Louganis was taking AZT at the time, setting his alarm for every four hours, even waking up in the middle of the night during the competition to take the medication.

"When I was in the pool, when I was competing, when I was training, HIV and AIDS didn't exist. That was a sanctuary for me. So it was a place that I could go to, really to seek refuge from the stress of the HIV diagnosis," Louganis says. Now at 62, Louganis is proof of what is possible: you can live and compete at the highest levels with HIV. You can win gold medals and be considered one of the greatest divers in the history of the sport.

Greg Louganis joins the LGBTQ&A podcast this week to look back on the controversy created by the concussion he received at the 1988 Olympics, sharing his HIV status with the world in 1995, and adjusting to the reality of HIV today, where with access to appropriate treatments, HIV is no longer a death sentence.

You can listen to the full interview on Apple Podcasts and read excerpts below.

JM: How were you thinking about HIV and how it might affect your diving career back in '88 when you first received your diagnosis?

GL: I really didn't know. Now back in '88, we thought of HIV/AIDS as a death sentence. So my thought was, "Well, if I'm HIV positive, I don't want to waste my coach's time. I don't want to waste my teammates' time." So I was going to pack up my bags and go back to California and lock myself in my house and wait to die. Because that was what we thought of HIV at that time.

But my doctor, who was also my cousin, he encouraged me to stay and train. He said that that was the healthiest thing I could probably do for myself. They put me on AZT right away because they wanted to treat me very aggressively. Also, at that time there were travel bans, so nobody could know about my HIV status or I wouldn't have been allowed into the country, into Korea. So it was a well kept secret.

He said that that was the healthiest thing I could probably do for myself. They put me on AZT right away because they wanted to treat me very aggressively. Also, at that time there were travel bans, so nobody could know about my HIV status or I wouldn't have been allowed into the country, into Korea. So it was a well kept secret.

JM: This was well before the drugs got good, well before we learned how to appropriately treat HIV.

GL: It's before we knew anything. AZT was an experimental drug. It was initially a cancer drug, and so they didn't know the toxicity. They didn't know potential side effects. We were basically guinea pigs.

The way that it was prescribed back then, it was two pills every four hours around the clock. So you're getting up in the middle of the night, in the middle of the morning, no matter where you are. If I was training, my little alarm would go off, and it's like, "Oh, AZT break." Just like in Rent.

As a performer, it's like, okay, you sprained your ankle? Wrap it up and get back out there. As soon as the music starts, you've got to perform. It's that mentality. I was able to compartmentalize my life. When I was in the pool, when I was competing, when I was training, HIV/AIDS didn't exist. That was a sanctuary for me. So it was a place that I could go to, really to seek refuge from the stress of the HIV diagnosis.

As soon as the music starts, you've got to perform. It's that mentality. I was able to compartmentalize my life. When I was in the pool, when I was competing, when I was training, HIV/AIDS didn't exist. That was a sanctuary for me. So it was a place that I could go to, really to seek refuge from the stress of the HIV diagnosis.

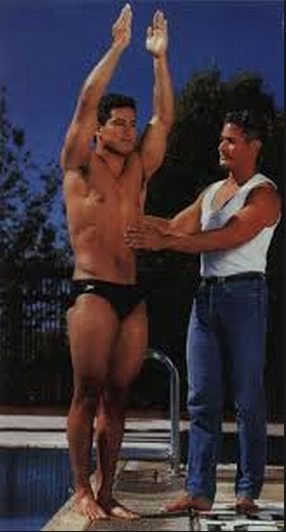

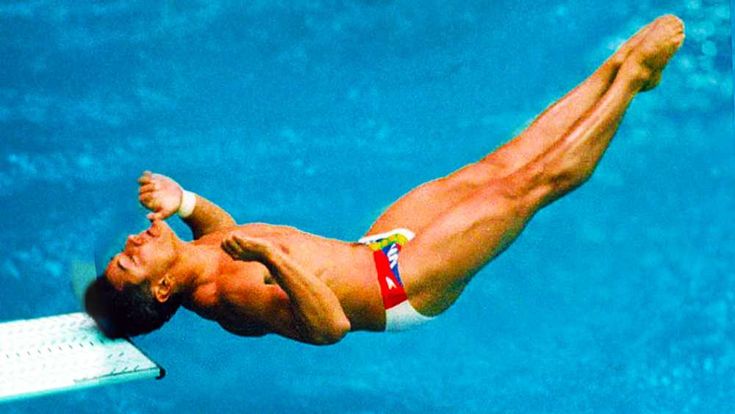

JM: It was at the '88 Olympics when you hit your head on the diving board and got a conussion. You got stitches and then got back up on the board 30 minutes later. I had wondered how much of getting back up there was your drive and determination, versus you thinking you had a death sentence and had nothing to lose.

GL: Well, trying to roll everything up in one little moment, going into the 1988 Olympic Games, I was the odds-on favorite. Going into the competition when I did my reverse two and a half pike and hit my head on the board, in that split second I became the underdog. And so the underdog position is much more comfortable to be in because then you have nothing to lose.

It was a wake-up call to my coach, Ron O'Brien, and myself to pay attention because nothing is guaranteed. Anything can happen, and so it really forced us to focus in on, Okay, let's just do one dive at a time and not get ahead of ourselves. Because once I hit my head on the springboard, I had no idea if I was going to be strong enough to do my dives on the 10-meter platform. I had to just get through that competition on the three-meter springboard first, and then we could look at the other stuff later. And so it really pushed us to focus on the moment, being in the moment.

JM: When you shared with the world that you were living with HIV in 1995, there was a controversy because in 1988, your head was bleeding while you were in the pool, even though there is no way to transmit HIV through pool water. Did any of the coverage focus on you competing with HIV and winning two gold medals? It seems like a big, very public opportunity to help combat HIV stigma?

GL: I guess it kind of turned into that. That wasn't my intent. I was doing Jeffrey, the play by Paul Rudnick. And I played Darius, so I was able to live out my fantasies and fears on stage because Darius is out and proud. He also, I felt, delivers the most poignant message to the lead character, Jeffrey, when he turns to Jeffrey and says, "Jeffrey, hate AIDS, not life." And that was a big part of it because I did. I felt isolated. I felt alone. And I was thinking, you know what? Chances are I'm not the only one. So if I come forward with what I've been dealing with, with my HIV, with all of that stuff and open that door up, then I would hopefully be letting people in who may be feeling the same way to let them know that they're not alone.

That wasn't my intent. I was doing Jeffrey, the play by Paul Rudnick. And I played Darius, so I was able to live out my fantasies and fears on stage because Darius is out and proud. He also, I felt, delivers the most poignant message to the lead character, Jeffrey, when he turns to Jeffrey and says, "Jeffrey, hate AIDS, not life." And that was a big part of it because I did. I felt isolated. I felt alone. And I was thinking, you know what? Chances are I'm not the only one. So if I come forward with what I've been dealing with, with my HIV, with all of that stuff and open that door up, then I would hopefully be letting people in who may be feeling the same way to let them know that they're not alone.

JM: You were one of the most famous gay men in the U.S. for a period of time. What has that been like for that to recede?

GL: Okay, so I'm dyslexic. And so I'm not one to...it was never a habit of mine to pick up a newspaper and read it every day. During my diving career, one thing that my mother used to do when I was growing up is she would come in and read the articles, and she'd share with me a nice article that somebody wrote, had nice things to say. And her instructions to me were, "Okay, next time you see this individual," because the sports reporters, we'd see them. So the next time I saw them, I could say, "Thank you for the kind words," so I can be in gratitude and be appreciative of what they might be saying about me if it was positive. The other stuff I didn't really care about, I didn't focus on. It wasn't interesting to me.

And her instructions to me were, "Okay, next time you see this individual," because the sports reporters, we'd see them. So the next time I saw them, I could say, "Thank you for the kind words," so I can be in gratitude and be appreciative of what they might be saying about me if it was positive. The other stuff I didn't really care about, I didn't focus on. It wasn't interesting to me.

JM: You were in a long-term relationship during the peak of your fame. Does any part of you wish that you could have been single and slutty?

GL: It's funny because I probably describe myself more as a serial monogamist. I latch onto somebody, and it's like, Oh, that's it. This is it. This is it. And then I stay too long. And it's like, Oh my God. This isn't working. Oh, this is not what I thought it was. But you learn through relationships and all that.

I'm happily divorced and I'm very good friends with my ex-husband, and we still share a lot of things together. It's a good thing. I think we recognized that it was good for when it was and it wasn't necessarily meant to be a forever thing. But now I'm single, and we'll see. I'm learning I need to be comfortable with myself. And I am. Me and the dogs, we do great. We navigate very well together. And also I'm learning that we don't have to look outside of ourselves for validation, that we can be the validating cheerleader for ourselves and have confidence in that.

It's a good thing. I think we recognized that it was good for when it was and it wasn't necessarily meant to be a forever thing. But now I'm single, and we'll see. I'm learning I need to be comfortable with myself. And I am. Me and the dogs, we do great. We navigate very well together. And also I'm learning that we don't have to look outside of ourselves for validation, that we can be the validating cheerleader for ourselves and have confidence in that.

JM: You've been very open about challenges with money, post-Olympics. How are you doing today?

GL: I'd be lying if I said, "Oh, it's great. It's great. It's wonderful." No. It's a struggle.

I think everybody's had a struggle with the whole pandemic and the shifting because most of my livelihood has been speaking and that kind of events dried up. It's changed a lot. Have I found my pot of gold? Not yet. Still looking.

JM: Growing up, you were dyslexic and thought you were dumb because of that. You've also said that you thought you were ugly and didn't fit in. And then the world gets to know this handsome, shirtless, Olympic gold medal-winner. Did your brain ever make that adjustment and catch up to the way that everyone else sees you?

You've also said that you thought you were ugly and didn't fit in. And then the world gets to know this handsome, shirtless, Olympic gold medal-winner. Did your brain ever make that adjustment and catch up to the way that everyone else sees you?

GL: No. No. I don't see myself that way. Yeah. I never saw myself in that light. I mean, when they would give me these labels, it's like, Oh, that's interesting. Yeah. I still probably saw this little kid with a wide, ethnic nose.

JM: After the 1988 Olympics, you retired. What's it been like to have to figure out what you wanted to do next?

GL: Well, I didn't think I'd see 30, honestly. Because I was diagnosed in '88 and generally they gave you two years, and so I didn't think I would see 30.

There was a point there, it's like, Oh, I'll do whatever I want because I'm not going to be here. And then a year would go by, a year would go by, a year would go by, kind of thing. So now at 62, it's like, Wow. Now, what do I do? I've got to get a job.

Now, what do I do? I've got to get a job.

JM: You've seen firsthand the evolution of HIV/AIDS meds. What was that moment like when you found out that with the current treatment you were undetectable and could no longer transmit the virus yourself?

GL: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. That was huge. When that information hit, it was like, Oh, wow. It's like, Okay, this is definitely not what it used to be. But I still go to a couple of doctor's appointments, young men who recently serial converted because it's still frightening. You don't know what it is, what it looks like, and how it's going to be managed and all that stuff. And I've probably been on just about every HIV/AIDS medication that's out there, so I know side effects and all that stuff.

JM: Did learning that you were undetectable have a noticeable effect on your mentality, how you thought about HIV and went up about your life?

GL: No, because what I was conditioned to in my early diagnosis, I'd go to my doctor's appointment, get my numbers, and then they'd put that file back in the shelves, back in the filing cabinet. And that's where I would put it, because Okay, I have my marching orders. I've got to do this, this, this and take care of myself and then go about the business of living. So I really didn't focus on it all that much. I didn't know if there were more medications coming down the pipeline. I wasn't really that stressed over all of that stuff because I knew that it was going to be what it was going to be. I didn't have control over it. A lot of my friends were like, Oh my God. This is the last combination I can do because I'm resistant to all of these drugs.

And I just didn't focus on that. When they put the file away, I put the file away.

And that's where I would put it, because Okay, I have my marching orders. I've got to do this, this, this and take care of myself and then go about the business of living. So I really didn't focus on it all that much. I didn't know if there were more medications coming down the pipeline. I wasn't really that stressed over all of that stuff because I knew that it was going to be what it was going to be. I didn't have control over it. A lot of my friends were like, Oh my God. This is the last combination I can do because I'm resistant to all of these drugs.

And I just didn't focus on that. When they put the file away, I put the file away.

Click here to listen to the full interview with Greg Louganis.

This is part of LGBTQ&A's new LGBTQ+ Elders Project. Click here to listen to an interview with the 87-year-old trans elder Barbara Satin.

LGBTQ&A is The Advocate's weekly interview podcast hosted by Jeffrey Masters. Past guests include Pete Buttigieg, Laverne Cox, Brandi Carlile, Billie Jean King, and Roxane Gay.

Past guests include Pete Buttigieg, Laverne Cox, Brandi Carlile, Billie Jean King, and Roxane Gay.

New episodes come out every Tuesday.

Olympic diver Greg Louganis tells his coming out story

play

LGBTQ+ athletes on how they came out to themselves (2:53)

Out sports stars from across the globe detail their experiences of coming out to themselves. (2:53)

Oct 11, 2021

Lindsay du Plessis

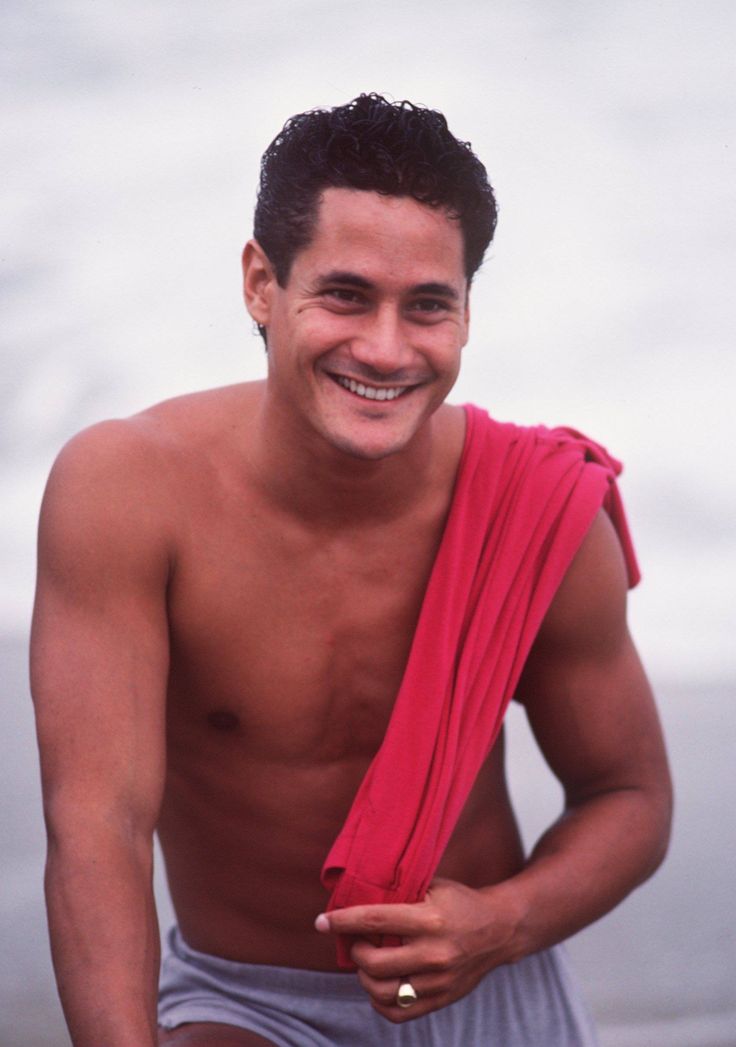

Olympic diving legend Greg Louganis [he/him], 61, won four gold medals across back-to-back Olympic Games, in 1984 and 1988. He came out publicly as gay at the Gay Games in 1994, but was out to those around him from an early age.

What was the 'coming out to myself' process like for you?

When you're really young, you don't really know about sex or sexuality or anything like that, I just felt different. I think I knew pretty early on about my sexual identity and then I fought against it because I was being called 'sissy boy' and all this other stuff. That was really challenging as far as self-acceptance [went], because we all just want to fit in. That was [when I was] pretty young -- probably pre-teens. I just knew that I was different.

Did you have a specific reason for coming out to the media/public, rather than keeping your private life private?

It's kind of an interesting journey as far as my coming out [goes] because I was out in my early 20s. I was out to my friends and family, but not to members of the media. Also, people in USA Diving -- they knew about my sexual identity, because the diving team is a really small team and we're travelling internationally. I came out at the Gay Games in 1994, welcoming the athletes and saying, 'It's great to be out and proud.' That was my public coming out. The reason why I came out at that time was that I knew that I was coming out with my book, 'Breaking the Surface,' in 1995, so I knew that I had to start getting comfortable with talking about my sexual identity with interviews. Because I knew that in 1995, a lot was coming out in the book, because I was coming out with my HIV Status, as well as an abusive relationship, depression, and my learning difference. That was a stepping stone into a bigger picture of being able to talk about who I was as a whole person.

I was out to my friends and family, but not to members of the media. Also, people in USA Diving -- they knew about my sexual identity, because the diving team is a really small team and we're travelling internationally. I came out at the Gay Games in 1994, welcoming the athletes and saying, 'It's great to be out and proud.' That was my public coming out. The reason why I came out at that time was that I knew that I was coming out with my book, 'Breaking the Surface,' in 1995, so I knew that I had to start getting comfortable with talking about my sexual identity with interviews. Because I knew that in 1995, a lot was coming out in the book, because I was coming out with my HIV Status, as well as an abusive relationship, depression, and my learning difference. That was a stepping stone into a bigger picture of being able to talk about who I was as a whole person.

READ: 17 LGBTQ+ athletes share their coming out journeys

USA diving great Greg Louganis, who won double golds at the 1984 and 1988 Olympic Games, is the sports director of the Red Bull Cliff Diving World Series, and is a champion of LGBTQ+ and HIV/AIDS awareness. Dean Treml/Red Bull via Getty Images

Dean Treml/Red Bull via Getty ImagesDid coming out impact your career and opportunities at all?

I'm sure it did interfere with endorsements. There was word back to me that because of my sexual identity [being] questioned, that was why I didn't get a lot of sponsorships and it definitely affected me professionally. Just a few years ago, athletes were getting endorsement because of their sexual identity and because of diversity and that whole mentality, but I was old news, so I got passed over, but I think it's wonderful. I needed to do what I needed to do not only for myself, but also for these other individuals behind me to benefit. I'm just so happy that the times have changed and that they do have these opportunities.

How has your sport changed with regard to the LGBTQ+ community during your career?

During my career, it was challenging, and so too after I retired from my sport. I think a lot of the powers that be in my federation were happy to see me move on and hopefully get a new person, a new face, in the limelight. It really has evolved. Now, there's a whole diversity movement within the sport to being able to talk openly about sexual identity or any bullying or anything that is happening, so there's much more awareness and a lot more sensitivity.

It really has evolved. Now, there's a whole diversity movement within the sport to being able to talk openly about sexual identity or any bullying or anything that is happening, so there's much more awareness and a lot more sensitivity.

What is the most rewarding, and perhaps unexpected, part of being out?

The most unexpected -- the thing that really struck me -- was when I was at the 2012 Olympics in London and I had an interview with Piers Morgan and he asked me about my HIV and I was just very casual. I said, 'Yeah, I take my meds in the morning, evening, and go about the business of living and that's just a part of my life,' so I talked really casually about that. Then, a few days later -- or it may even have been the next day -- [Australia Olympian] Ji Wallace came forward about his sexual identity and HIV status, saying that I was his inspiration. That's what surprises me. That's what I'm kind of blown away with, because I don't think that anybody is really looking at me. It's surprising the impact that we all have really, being open and honest in who we are and sharing that. It empowers so many individuals to not hide in the shadows, to be embraced, because, really, I think the deadliest thing is to isolate. Letting go of the secrets enables you to feel seen, heard and embraced.

It's surprising the impact that we all have really, being open and honest in who we are and sharing that. It empowers so many individuals to not hide in the shadows, to be embraced, because, really, I think the deadliest thing is to isolate. Letting go of the secrets enables you to feel seen, heard and embraced.

What would your advice be to folks who are struggling with their identity?

There are going to be people who criticise, but chances are that if people are true friends and truly love you, then they're going to embrace you and support you. To have that support is so meaningful and so powerful. Doing it in such an honest way; that's what I think people gravitate towards -- authenticity. It really not only empowers you, but it strengthens relationships. It strengthens those bonds we have with each other that we can share ourselves authentically.

When debating coming out in your mind, what were your worst - and best - case scenarios? And did either come to pass?

My thought before I came out to my mom, that was the scariest thing -- to lose the love and support of your parent. My thought before I came out to my mom was, 'Oh my God, if my parents knew that I was gay, then the earth is going to open up and swallow me whole.' Did that come to pass? No. I was kind of disappointed that my mother wasn't more upset or something -- you know, have some sort of reaction instead of 'what's for dinner?'

My thought before I came out to my mom was, 'Oh my God, if my parents knew that I was gay, then the earth is going to open up and swallow me whole.' Did that come to pass? No. I was kind of disappointed that my mother wasn't more upset or something -- you know, have some sort of reaction instead of 'what's for dinner?'

It was a little bit more nerve-wracking when I came out in '95, prior to my book, about my HIV status. Being a gay man with HIV, at that time there was still a lot of stigma surrounding HIV. A lot of the attitude in the country and the world was, 'It's killing the right people -- gay men, IV drug users and prostitutes.' And so there was a whole lot of judgement. Because HIV is transmitted sexually, there was a lot of shame surrounding that and a lot of self-loathing and shame and that's a really horrible place to be. I think we're coming around to being more understanding about the virus. It's manageable -- it's not a death sentence anymore, but there's still some stigma, so if you educate yourself, you empower yourself.

Did you ever feel any pressure, either internally or from speculating fans, to be a role model or an ambassador for the queer community? And is that something you embrace now?

That was one thing I was a little concerned about when I came forward with my HIV status -- that I would be the poster boy for HIV. That wasn't something that I wanted, but in a sense I did give it a face and bring awareness to it. I thought that was a good thing. It's not anything that I wanted -- I didn't want that kind of attention -- but I learned that stepping into that can be really powerful and influential. I'm not anything special and I'm no better or worse than anyone else. As long as I can represent myself, that's the best I can do. The one thing when I work with kids -- I encourage them to learn to be their own heroes, because we all have a hero inside of ourselves to be the best of who we are. If we continue to bring that forward, then we will have lived a life to be proud of.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- EU Privacy Rights

- Cookie Policy

- Manage Privacy Preferences

© ESPN Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved.

Greg Louganis diving personal life hiv. Photo - August 6, 2020

Viktoria Dmitrieva

Share

Comments

His biography is an eternal struggle.

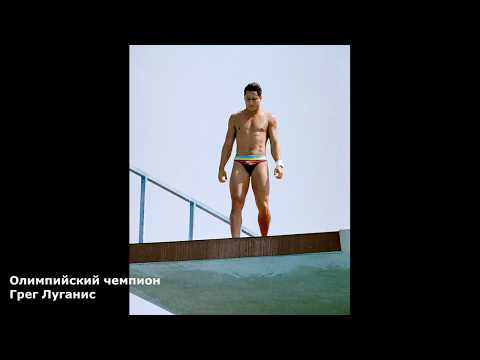

American diver Greg Louganis is probably the coolest in his sport. He is the only man among men to win four Olympic golds, become a 5-time world champion, 6-time Pan American Games champion and 47-time US champion. But all this fades against the background of the fact that Louganis could have died before the age of 30.

But all this fades against the background of the fact that Louganis could have died before the age of 30.

His biological parents left him at 8 months old, but Greg was lucky to get into a foster family. She supported him in his desire to go in for sports. The American first ended up with coach Sammy Lee (two-time Olympic champion), and in the late 1970s he began to train with Ron O'Brien . Already at the age of 16, he went to his first Olympics in Montreal. But youth did not win over experience: in the final, Luganis lost to Klaus Dibiasi, who won the third Olympic gold , , who won the third Olympic gold.

A post shared by Greg Louganis (@greglouganis) on

- My father is a Greek by nationality, we seriously discussed with him the option of playing in Moscow for the Greek national team. The trouble was that my father did not have a Greek passport. And the procedure for its registration would take too much time to manage to resolve the issue with my citizenship.

Yes, the boycott was a terrible blow for me. And that's why I went to the 1982 World Cup in Guayaquil fantastically motivated. After all, Alexander Portnov, who became the Olympic champion in Moscow on a three-meter springboard, was supposed to come there.

By that time, I had the silver of Montreal and the gold of the 1978 World Championship, won on the tower. Until that time, I had not competed on the springboard in major competitions. But this did not at all prevent a huge number of Americans from looking at me as a person who "will now show everyone who is the boss in the house.

"

He took his at the Olympics in Los Angeles and Seoul (gold medals on the 3-meter springboard and 10-meter platform). The last Games become the most important and dramatic in Louganis' career. Six months before the competition, he learned about HIV infection. He was about to leave the sport, but his cousin (part-time doctor) persuaded him to stay by prescribing therapy. Every four hours, the jumper took zidovudine, the first antiretroviral drug, the side effects of which led the athlete to latent depression.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Greg Louganis (@greglouganis) on

In the 80s, HIV was a death sentence, but Louganis did it.

True, in Seoul, no one knew about his diagnosis. If he had told, then the jumper would not have been allowed into South Korea. The situation worsened during qualifying when Greg hit his head on the edge of the springboard. The American hit his head and fell into the water. The water did not pose any danger to the athletes, but the national team doctor James Puffer may have been seriously injured. He darned the wound without gloves, knowing nothing about Louganis' HIV infection.

After the Olympics, the American ended his sports career and stopped appearing in public.

- I felt isolated because my illness was a mystery to many. I did not meet with friends and family, and although almost everyone knew about my orientation, only a few people were aware of my HIV status. I lived as if on an island.

He publicly confessed everything in 1995 in his book Breaking the surface. A little earlier, Louganis spoke about his homosexuality. And if everyone reacted normally to the latter, then the story of HIV shocked everyone.

First of all, the participants of the Games in Seoul. And if there was no risk for the athletes (specialists confirmed this to them), then Puffer was seriously scared. Fortunately, the doctors did not find an infection in him. The athlete then for many years apologized to all athletes.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Greg Louganis (@greglouganis) on

When he got worse, the doctor persuaded him to try a new therapy. That helped. So much so that in 2011 Louganis returned to the sport. He began to train in one of the sports clubs in California, and at the Games in London and Rio he was even a consultant for the US team. In parallel with this, an athlete can often be found at charity events, motivational lectures and other activities dedicated to LGBT and HIV.

Now Luganis is 60. And if you look at his happy photos on the net, it is impossible to think that he is sick. Greg leads a full life, works hard, plays sports and spends time with his beloved dog. He still considers his salvation not so much therapy as sports, which distracted him from dark thoughts.

- HIV taught me to believe that I am much stronger than I thought. And showed that I should not take everything for granted. I used to think that I would hardly live to 30. I never know what will be waiting for me around the corner. And I never consider my mistakes as failures, because this is nothing more than just a lesson. And you know, I had enough of such lessons.

Subscribe to the Sport24 channel on Yandex.Zen

On March 22, 2022, by a court decision, the Meta company, the social networks Instagram and Facebook were recognized as an extremist organization, their activities on the territory of the Russian Federation are prohibited.

"He cannot be forgiven." Diving legend Greg Louganis hid HIV and scared opponents with blood in the pool

The underside of his success is monstrous health problems: several times an American could end his career and generally thought that he would not live to be 30 years old.

Also, at the 1988 Games in Seoul, Greg was afraid that he had infected other athletes with HIV. Here is his story.

Greg was abandoned by his parents when he was less than a year old. As an adult, he found them (and seemed to even understand)

Greg was born in 1960 in El Cayon (California). The parents, who are of Swedish and Samoan origin, gave the boy to an orphanage when he was 8 months old.

A new family was found quickly - Greg was adopted by Francis and Peter Louganis: Peter had once moved to the USA from Greece, so the child got a Greek surname. Subsequently, the new parents told Greg about the adoption, and he started looking for the real father and mother: he found the Samoan Tuwal Lutu in 1984, and his mother only in 2017 thanks to DNA tests.

The very fact of parental abandonment weighed heavily on Louganis: “It always seemed to me that if my real parents didn't love me, then no one else could. Then I got out of control and didn’t let anyone near me.” Subsequently, Greg was reassured only by the knowledge that the parents came to the orphanage for the sake of his own future: they did not have money to support the child.

Greg was attracted to sports since childhood: at 1.5 he was dancing, acrobatics and gymnastics, at three he competed and trained every day. Asthma and allergies did not interfere - on the contrary, the doctors advised me to do even more actively.

Greg didn't resist: he took trampolining lessons, and then, when he was 9, he became interested in diving: then the family moved into a house with a large swimming pool.

Out of curiosity, Luganis tried to perform tricks of jumping on a trampoline right in the pool - when his mother saw this, she was so scared for her son that she took him to diving lessons.

Stuttering, crooked knees, many phobias - Louganis overcame everything, and made some things an advantage

Jumping was not easy for Greg for several reasons:

1) Little Louganis was not talkative at all, slowed down - he stuttered and suffered from dyslexia. According to Greg's recollections, at home, his older sister finished all the phrases for him, because he could not formulate a thought for a long time.

At school, of course, his sister was not around, so he did not open his mouth there at all. Because of this, Greg was constantly laughed at and made fun of by classmates. More-often beat and called a niger because of the dark skin color-so he developed self-doubt, which greatly interfered in sports.

2) At the same time, Greg began to complain of pain in his legs: it turned out that his knees were developing abnormally. Doctors advised the boy to stop playing sports, otherwise there was a risk of disability.

Luganis did not obey: over the years, his legs became significantly twisted, although this did not interfere with him - at an adult level, it even helped.

By crouching while jumping, he could monitor the situation through the space between his legs, although jumpers with normal legs do not have such an opportunity.

3) Surprisingly, Greg was afraid of heights. In fact, he was afraid of many things. His coach Ron O'Brien immediately noticed the potential in the boy, but doubted that he would cope with phobias.

Louganis coped by acting on the principle “to overcome fear, you need to face it”. For example, he suffered from ophiophobia - the fear of snakes - and bought a boa constrictor at a pet store. Gradually, the fear went away: Greg looked after the snake, fed and treated. Something similar happened with the jumps, although it took much more time: Louganis progressed, but the fear remained.

At one of the tournaments, two-time Olympic champion Sammy Lee noticed him: “When I saw Greg, I immediately understood that he would be the greatest diver if he found the right coach.” They soon began working together.

By the age of 16, Louganis won many tournaments in the US and qualified for the 1976 Olympics in Montreal. But he was not lucky at the Games: before the performance on the springboard, his tooth ached badly - because of the pain, Greg could not concentrate and took only 6th place. The option with painkillers was not considered - the athlete was afraid that he would fail the doping test, and went to the dentist.

On the platform, the performance turned out better - silver. At the award ceremony, champion Klaus Dibiasi leaned over to Louganis and whispered: "In 4 years you will be standing in my place."

He was afraid to crash on the platform - and miraculously did not see how it happened with a competitor

Probably, DiBiase would have been right, but politics intervened: the US team boycotted the 1980 Olympics in Moscow, where Louganis, already a world champion, really wanted to. So much so that I thought about the possible citizenship of Greece (the father's homeland), but because of problems with the documents, it did not work out.

In 1982, Greg took two more World Championship golds, the first ever to receive 10 points for a jump from each of the seven judges.

And in 1983 something happened that made Louganis almost quit his favorite sport. Despite all the successes, the fear of jumping persisted: most of all, the American feared that one day he would hit the platform with his head and break. At competitions, he pushed these fantasies, but the phobia still prevented him from learning new elements.

For the Universiade-83 in Edmonton, Greg mastered the most difficult back somersault on three and a half turns with a tuck (307C). Before Luganis, only one person in the world had mastered such a jump - the Soviet athlete Sergei Shalibashvili, who also came to Edmonton.

It so happened that Shalibashvili spoke just in front of Luganis. Greg watched the jumps of all competitors, but when the Soviet jumper was about to perform 307C, he turned away. Louganis knew that he, too, would have to spin in the hardest jump, and did not want to shoot down and scare himself, looking at Shalibashvili's attempt.

This decision probably saved Greg's career: in that attempt, Shalibashvili hit his head on a concrete platform, breaking his skull in several places. It was not possible to get him out of a coma - 6 days later, the Soviet athlete died.

“It was like I knew something terrible was going to happen. And then he felt the platform shake and heard a scream. Only then did I open my eyes. I ran to the pool and saw blood in the water. A lot of blood. I already wanted to jump there for Sergey, but they stopped me.

Later, Luganis admitted that if he had seen how Shalibashvili hit, he would probably no longer be able to jump himself. He recalled how in 1979 he made the same mistake and crashed his head into the platform: the only thing that saved him was that the platform was wooden - but Greg still lost consciousness for 20 minutes.

Back then, at the Universiade-83, Luganis finally pulled himself together and did a sterile 307C by jumping into a pool of blood.

Homosexuality and HIV-positive status - Louganis hid it from coaches 100 points.

Before the last jump on the tower, Louganis listened to the music from the movie "Chariots of Fire" and talked to his beloved teddy bear named Gar to calm down.

Around the same time, Greg became aware of his homosexuality - he started a relationship with his own manager Jim Babbitt, but their union quickly fell apart. Babbitt constantly stole from Greg, beat him and once raped him with a knife to his throat.

Shortly after the breakup, Babbitt died of AIDS. Six months before the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, Luganis passed the tests, and the result was staggering - they found HIV. Greg wanted to quit the sport, but the doctor dissuaded him by prescribing an antiviral drug to be taken every 4 hours.

At first, Greg wanted to tell the coaches and the USOC: “It was really hard for me. I felt that the committee should know about my illness. What if I can't compete in the Olympics because of this?

But in the end he kept silent - only the closest people knew about the disease, and Luganis resigned himself to the fact that he would not live to 30 years.

Seoul 1988 incident: head bashed, blood in the pool, doctor without gloves

Greg did go to Seoul 1988, and there was a wild incident in the 3m springboard qualifying.

After a jump error, Louganis hit his head on the springboard, suffering a concussion. This did not prevent him from reaching the final - Greg took gold there, thinking not about titles at all.

Because of the blow, he cut the skin on his head - and some blood spilled into the pool. Team doctor James Puffer rushed to Louganis to quickly stitch up the wound. Greg wanted to tell him he was HIV positive, but he didn't dare. It wasn't until Puffer was done with the wound that Louganis realized the doctor hadn't even put on gloves.

In fact, Puffer was required to wear gloves, but the wound on Louganis' head scared him so much that he rushed to help, forgetting everything else. According to Louganis himself, he was paralyzed with fear when he thought that Puffer and the other jumpers might become infected because of his blood.

But telling someone about it was even scarier.

At those Games, Greg took another gold, becoming 4-times, but, as his coach recalled, there was no smile on the athlete's face after the award.

Luganis kept a secret about the disease and the incident in Seoul-1988 for 7 years - only in 1995 did he admit that he was HIV-infected. At the same time, Dr. Puffer took an HIV test, which - to the delight of both James and Greg himself - turned out to be negative. “This is all very sad. I'm talking about Greg's illness. To speak or not to speak about HIV status is the right of any person. He can admit it when he sees fit, ”Puffer said when he learned about Louganis’s diagnosis.

Some athletes, after Greg's confession, asked the IOC to test all participants in the Games for HIV, but the committee was skeptical about this idea. “I don't think it makes sense. It will be useless. And it’s just stupid,” said the head of the IOC medical commission, Alexander de Merode.

Later experts confirmed that it is almost impossible to get HIV through the blood in the pool.

First, blood dissolves in huge volumes of water. Secondly, the chlorine contained in the water kills HIV. Thirdly, the athletes would not have become infected through the skin anyway - only if Greg's blood got into their open wounds. Only Dr. Puffer really took risks, but everything worked out for him.

"You can't forgive for this." Louganis was criticized by athletes, but defended by the media and officials

American diver Wendy Lucero: “I think Greg had the right to remain silent about the diagnosis, but he had to be honest with the doctor. The doctor was in danger! He had to confess."

Head of the 1988 Seoul Organizing Committee Seo Chik Pak: “It's a pity that Louganis participated in the Olympic Games knowing his HIV status. From a moral point of view, he did absolutely wrong, especially when he got injured and bled.”

Dick Kazmaier, a well-known American football player at that time, did not spare Greg either: “He cannot be forgiven. Louganis should have more respect for the people around him.

Look at the NBA - any basketball player who gets hurt during a game immediately leaves the court.

Athletes with a positive HIV status, according to the rules of the IOC, may well participate in the Games - but only with the permission of the doctors, who must determine whether the athlete will not put himself or others at risk. Of course, Greg did not receive approval from the doctors.

But the head of the US Diving Federation, Steve McFarland, said in 1995 that Louganis had every right to remain silent about his HIV status, even if he violated the rules and put others at risk: “We live in a country that respects privacy and freedom the words. I can’t imagine a situation where we will require every athlete to have a medical history before being allowed to compete.”

US NOC spokesman Mike Moran was of the same opinion: “It is not our intention to test all athletes for HIV. People need to understand that the athletes on the US Olympic team represent diversity and all aspects of America.

We are not going to regulate it in any way, shape it or change it.”

In general, in 1995, the American media defended Greg in the situation with blood in the pool. But Dr. Puffer was accused of negligence, because wearing gloves is his direct duty.

Luganis himself hopes that his story will serve as a lesson for everyone.

Life after sport: coaching, books, and dog training

In 1996, Greg Louganis wrote an autobiographical book, Breaking the Surface, which was made into a movie a year later.

After retiring from sports, he acted in films and played in plays (he became interested in theater in his student years). He also got a lot of dogs, most of which he named after characters from Harry Potter, and participated in training competitions. At 19Greg's book "For Your Dog's Life: A Complete Guide to Grooming" was published in 1999.

In 2010, Louganis began his coaching career, working with people of all ages in Fullerton (California), and in London 2012 and Rio 2016 he was the coach of the US diving team.