Interventions for attention seeking behaviors

How can you prevent or replace attention-seeking behavior?

If you did an impromptu survey of one hundred classroom teachers, likely all of them would report facing attention-seeking behaviors in the classroom at some point in their career. Many of those teachers would report feeling confused or frustrated about how to stop attention-seeking behavior and prevent it from starting in the first place. Whether it’s distracting other classmates or repeatedly using problem behavior to divert your focus, attention-seeking behaviors present a problem for even the most well-managed classrooms.

Before teachers begin to address attention-seeking problem behaviors in the classroom, it’s essential to understand what factors contribute to attention-seeking behavior and the science behind how to address it.

What is attention-seeking behavior?To clarify, attention-seeking behavior in the classroom is any behavior a student engages in—whether it’s positive or negative—that results in an adult or student providing some form of social acknowledgment to the child. Attention-seeking behaviors are social, meaning they only happen in the context of other people.

Attention-seeking problem behaviors in the classroom can come in all forms—including out of seat behavior, blurting out, making noises, bullying or teasing peers, excessive hand-raising, or merely talking when it’s not an appropriate time.

In short, attention-seeking problem behaviors share these qualities:

- Maintained by social attention from others – When students engage in attention-seeking behavior, they receive what they were looking for—a response from others.

- May start as mild and easily redirected behavior, but can quickly become a problem.

- Often does not respond when addressed with a reprimand. Even negative attention in the form of a redirection or reprimand to a student may still be providing notice to the problem behavior.

Often students who are seeking attention will accept any attention, even if it’s in the form of an attempt to discipline the student.

Often students who are seeking attention will accept any attention, even if it’s in the form of an attempt to discipline the student.

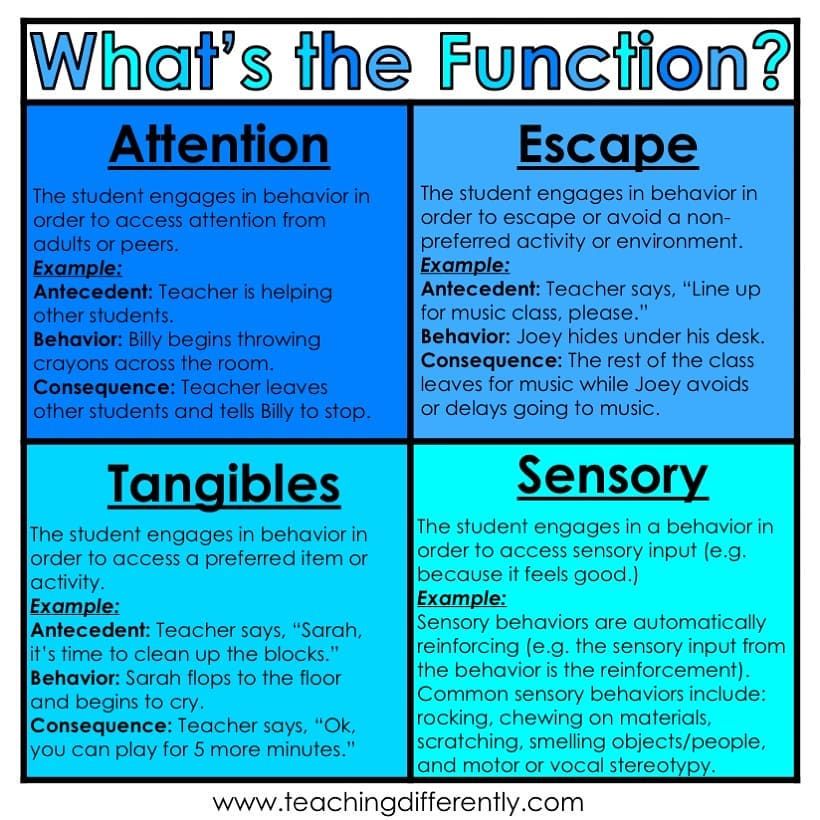

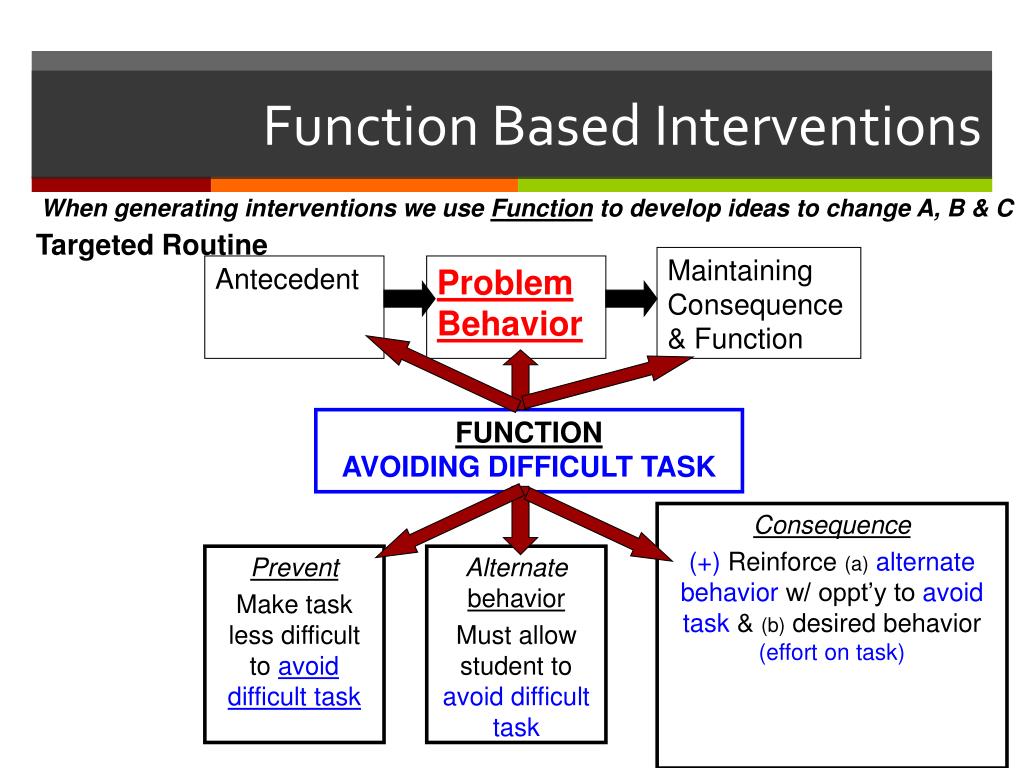

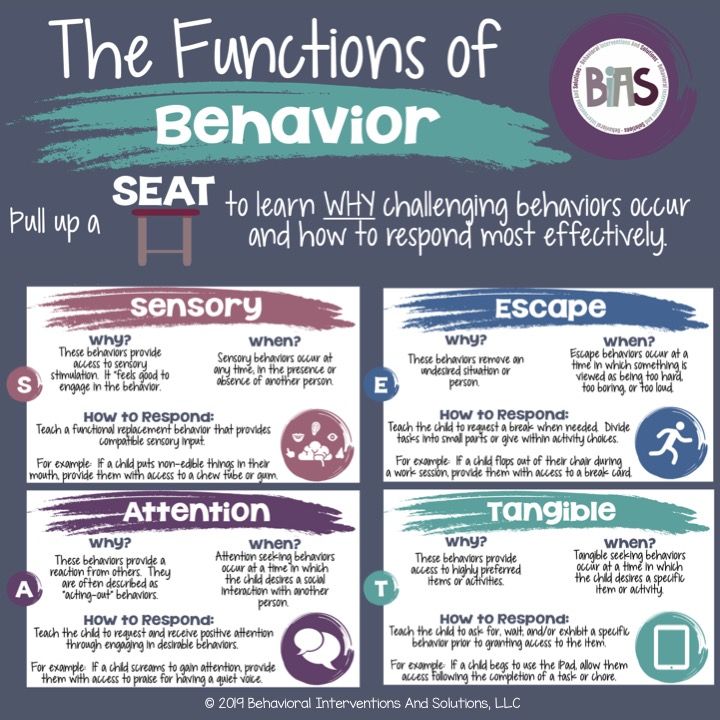

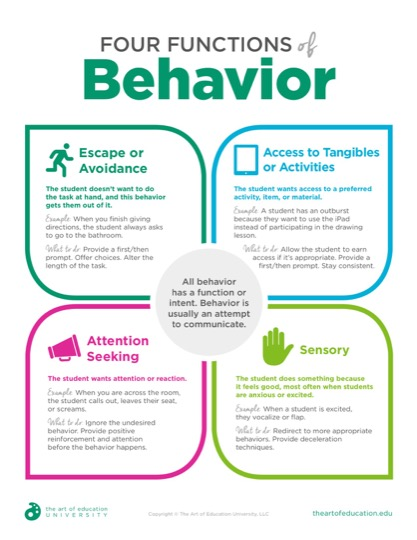

When it comes to decreasing and preventing attention-seeking behaviors in the classroom, it’s essential to understand the function, or “Why?” a student’s behavior is happening in the first place. The most straightforward answer is to get attention.

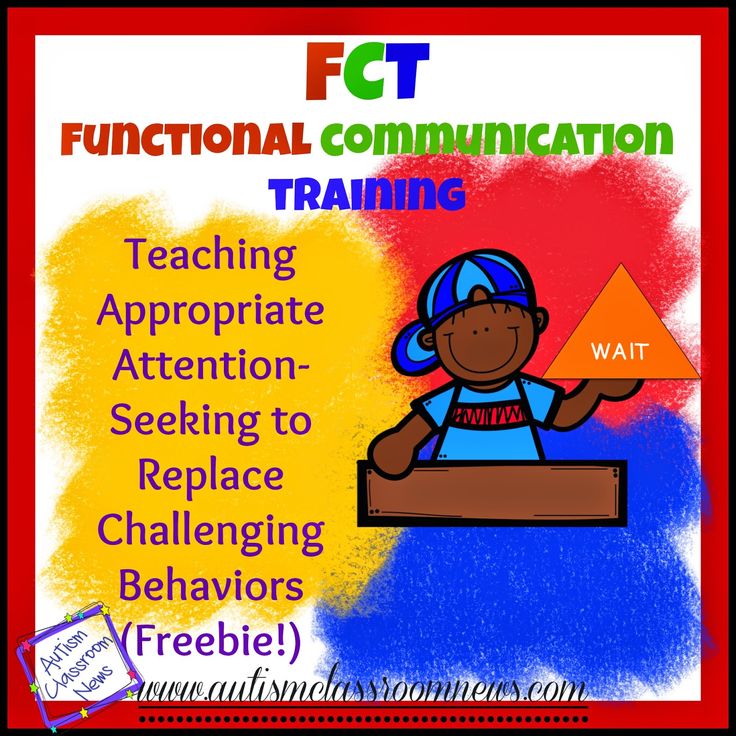

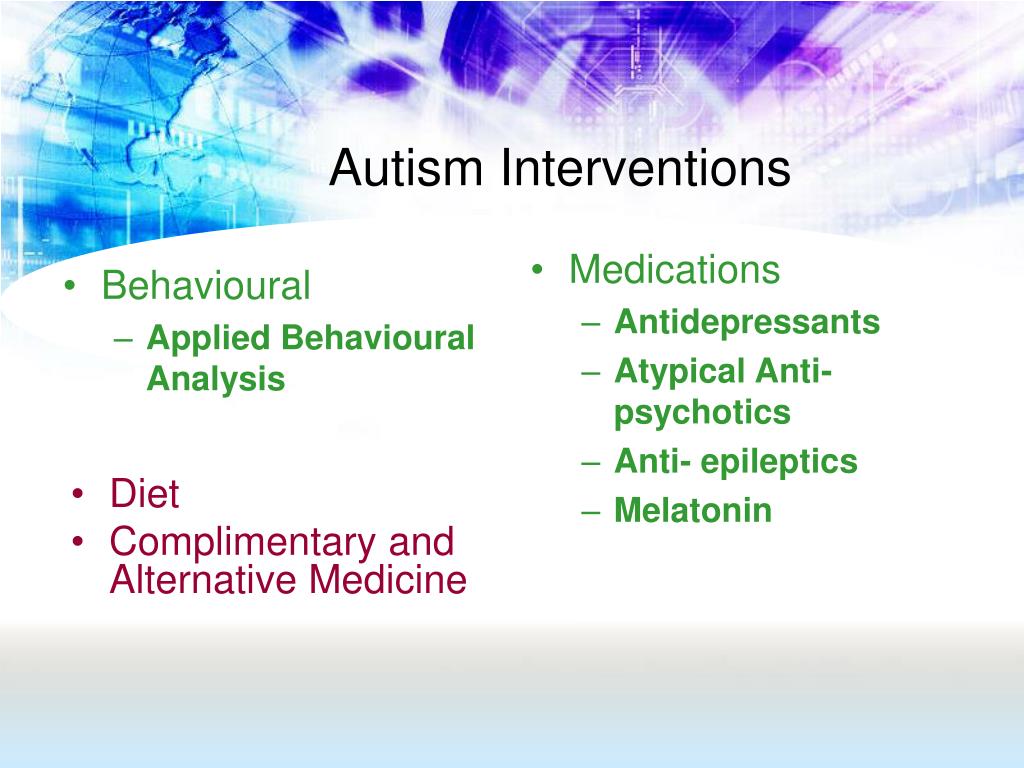

But underneath that answer, Applied Behavior Analysis helps us understand that other factors may contribute to attention-seeking problem behaviors. Many students, especially those with higher needs, may not have the best tools and strategies to engage socially. Some students may lack opportunities for appropriate adult or peer interaction outside of the classroom and use inappropriate opportunities to see attention. Depending on the student’s needs, you’ll likely need to develop an individualized strategy of proactive and reactive strategies that work to decrease the problem behavior.

The suggestions below may help in brainstorming tools for students.

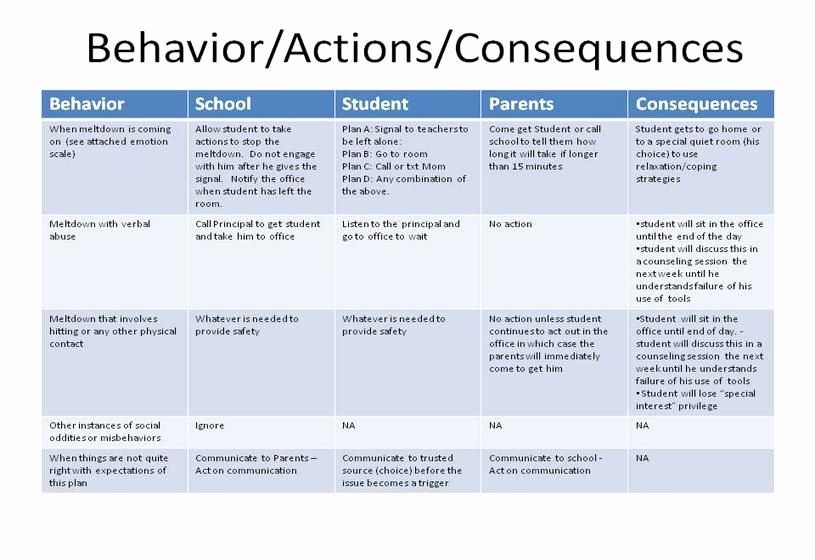

Before You BeginIt’s worth noting that before beginning any interventions to reduce problem behavior, carry out two steps. First, specifically, define the attention-seeking behavior that you intend to address. Too often, teachers talk about problem behaviors using wishy-washy or emotional terms rather than concrete, observable definitions. Instead of saying, “The student is noisy and blurts out during circle time.” Define the behavior as “Attention-seeking behavior occurs in circle time, any opportunity when the student speaks to an adult or peer without first requesting permission by hand-raising or being directed to share with another by the teacher.” This definition not only contains a more precise, more objective description of the behavior, but it also includes what actions the student should be doing instead.

Secondly, you’ll want to collect some data. Finding out when the problem behavior occurs most often and how many times the problem behavior occurs (i. e., per minute, per day, per week) can help you better understand when you do intervene—if that intervention was successful. Collecting data can also help you discover patterns that might help you create an intervention plan. Perhaps problem behavior happens consistently during one daily activity or if individual peers are nearby. Having data available on these factors better informs the intervention you choose, and if that intervention decreases the problem behavior.

e., per minute, per day, per week) can help you better understand when you do intervene—if that intervention was successful. Collecting data can also help you discover patterns that might help you create an intervention plan. Perhaps problem behavior happens consistently during one daily activity or if individual peers are nearby. Having data available on these factors better informs the intervention you choose, and if that intervention decreases the problem behavior.

Once you’ve collected data on a student’s attention-seeking behaviors in the classroom, you’ll want to develop some ideas on what the student should be doing instead. Focus on the question: What are the replacement behaviors or things this student could be doing instead of attention-seeking? Then focus proactive strategies on teaching and rewarding those replacements. Some examples might include:

- Provide attention on a time-based schedule.

Once you collect data, you may discover that a student engages in attention-seeking problem behavior on average every 15 minutes throughout the day. One strategy is to provide social attention to that student before problem behavior occurs—perhaps every 12-14 minutes. By checking in with that student and giving praise for good behavior, you’re may avoid problem behaviors from happening in the first place. Over time as the student builds success, slowly increase the time. If that seems like too many resources dedicated to one student, remember when the problem behavior occurs, you’re likely spending time away dealing with the response anyway.

Once you collect data, you may discover that a student engages in attention-seeking problem behavior on average every 15 minutes throughout the day. One strategy is to provide social attention to that student before problem behavior occurs—perhaps every 12-14 minutes. By checking in with that student and giving praise for good behavior, you’re may avoid problem behaviors from happening in the first place. Over time as the student builds success, slowly increase the time. If that seems like too many resources dedicated to one student, remember when the problem behavior occurs, you’re likely spending time away dealing with the response anyway. - Set clear expectations for all students about attention-seeking. For example, don’t allow some students to blurt out and others. Don’t permit blurting in some activities but not others. For some students, inconsistent expectations create confusion.

- Practice and reward how to appropriately ask for attention.

Don’t assume that all students have mastered hand-raising and other social cues for recognition. Practice these skills and provide praise when the student uses them.

Don’t assume that all students have mastered hand-raising and other social cues for recognition. Practice these skills and provide praise when the student uses them. - Teach and reward appropriate waiting. Sometimes the student has the tools to initiate, but not the skills to wait appropriately for attention. Practice waiting for longer durations and provide praise when the student waits for your attention.

- Teach the student how to initiate to a friend without disruption. Some students lack the skills to know what to say to a peer and instead rely on inappropriate interactions to gain attention. Try out a social skills curriculum in your classroom to help students better engage without disruption.

- Use a behavioral contract or “if…then…” statements to indicate when it’s okay to gain attention. Sometimes a simple behavioral contract like “if you complete your seat work quietly, then you can have five minutes of free time with a friend” can be a powerful motivator for students to decrease attention-seeking behaviors.

- Use visuals schedules to indicate when attention can be delivered. Many students with additional needs respond well to visual cues. By indicating when it’s an appropriate time to gain an adult or peer’s attention, you set more apparent and easy to follow expectations.

The above strategies are helpful to reduce or avoid attention-seeking behavior in the classroom, but what are strategies once the problem behavior occurs? The key to addressing attention-seeking behaviors is simple—avoid giving attention. Depending on the severity of the disruption and the student, this might not always be possible. Some examples of reactive strategies include:

- Ignore attention-seeking behaviors. Providing the least amount of attention possible avoids feeding into or maintaining the problem behavior.

- Have an alternative consequence, but be consistent. If it’s not possible to ignore the behavior altogether, have a set of consequences (redirection, consequence removal, take a break, etc.

) that happen each time predictably. That way, a student understands that despite their behavior, they’ll receive the same consistent attention and nothing more or less.

) that happen each time predictably. That way, a student understands that despite their behavior, they’ll receive the same consistent attention and nothing more or less. - Give positive attention to someone else. Sometimes, merely drawing positive attention to another student’s appropriate behavior can help remind the student of the appropriate expectations. “Did you see how Student A lined up at the door quietly? Let’s give her a high-five for doing a good job!” can help motivate students to get back on track.

- Remember, giving a reprimand is still giving attention. Finally, as mentioned above, negative attention still serves as attention for many students. Rely more on proactive strategies than reactive ones when trying to address attention-seeking behavior in the classroom.

Bachelor of Arts (B.A.), Psychology | University of Minnesota

February 2020

More Articles of Interest:

-

- How Does Research Support Applied Behavior Analysis?

- Is EFT Tapping Effective with Those with Autism?

- What are the characteristics of a teacher using ABA?

- What is a Bio-medical Approach to Autism?

Strategies for Attention Seeking Behaviors

We all want and need attention.

However, every teacher has had that one student who wanted

MORE.That one student who is not satisfied with the amount of attention the typical student receives.

This student seems to crave that EXTRA– attention and is willing to be a disruptive force in the classroom to get it.

This week, we are continuing my Behavior Strategies Series where I focus on the 4 main functions of behavior and what you can do to prevent them from taking over your classroom.

Last week we examined

Strategies for Avoidance Behaviors. You can read the blog post here.Today, I am focusing on Attention-Seeking Behaviors.

It’s frustrating when your students are constantly misbehaving in order to get your attention or the attention of their classmates. Having to repeatedly address their calling out, noise making and peer agitating behaviors is tiring and presents a major challenge to your teaching process.

I want to shed some light on students who misbehave to get attention and what you can do about it.

Function # 3: Attention -Seeking

The Characteristics

Some of the attributes of students motivated by getting attention are:

-

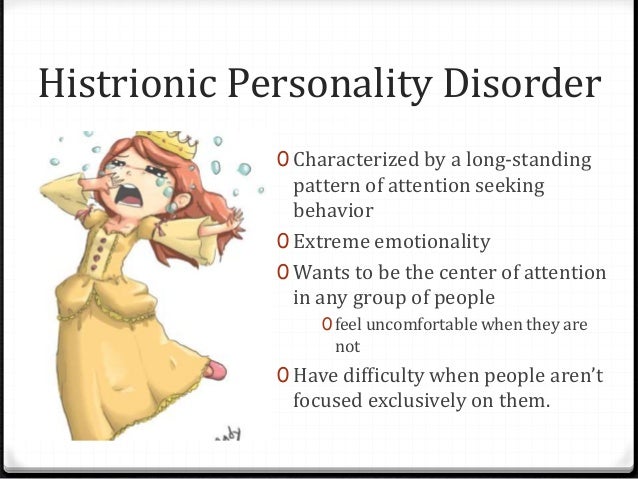

Like to get response from others– They enjoy how their behavior affects others.

-

Like to be the center of attention – They do not like to share the spotlight.

-

They need an audience– It doesn’t work them unless someone watching or paying attention.

-

They like to perform (can we say

DRAMA)- A lot of times, these students can take things over-the-top unnecessarily.

The Student’s Goal

For the most part, these students have one main goal:

Possible Reasons for this Behavior

-

Less attention in other areas of life– This student may not be getting the attention they need away from school.

-

Makes them feel important or valuable– Some student may feel that they matter, only when given that extra-attention

How this affects your classroom

Strategies for the Student

Give a lot of attention for appropriate behavior– Catch your student behaving responsibly and celebrate and encourage to the max.

Teach replacement behaviors– Show your student appropriate ways to get attention.

Set up opportunities to get attention appropriately– Create situations where your student can get natural (built in) attention via classroom job or responsibilities (ex: Class comedian – read or tell teacher approved joke of the day)

Give attention to students demonstrating positive behavior as a cue– Pay attention to on-task students to give your misbehaving student a hint on what behavior gets your attention.

Planned ignoring– Let the student know that the negative attention-seeking behavior is not ok and will be be ignored. Be specific on which attention-seeking behavior is ok and make sure to give plenty attention when that desired behavior is demonstrated.

Allow for chill out – When behaviors get out of control, provide an opportunity for the child to go to an separate area within the classroom to calm-down and refocus.

Strategies for You

Accept that your student needs more attention than the norm.- sometimes no matter how much attention we give, that bucket will never get full. That’s ok. Do what you can and accept their need.

I’m not going to lie to you, a student who displays problematic attention-seeking behaviors is a lot of work. Choose 1-3 strategies, be consistent and you will see your behavior management workload decrease.

Let me know in the comment section below: What type of attention-seeking behaviors are you experiencing? What strategies are you currently using? Leave your comment below.

Breast cancer awareness interventions for women

Review question

We reviewed the evidence for the effectiveness of various interventions to raise awareness of breast cancer among women. We found two randomized controlled trials with high quality evidence.

Relevance

Breast cancer is the most common diagnosed cancer among women. Early detection, diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer are key factors in improving outcomes. Since many women can self-diagnose breast symptoms, it is important that they are aware of breast cancer, ie. had sufficient knowledge, skills and confidence to pay attention to changes in the breast in a timely manner and consult a doctor.

Study profile

Search for trials investigating breast cancer awareness interventions in women was conducted in January 2016. We found two clinical trials involving a total of 997 women.

A study to promote early detection funded by the UK Breast Cancer Center involved 867 women who were randomly assigned to receive one of three interventions: (1) a printed brochure and a conventional (standard) ) care, (2) a printed brochure and routine care combined with a personal consultation with a health care professional, or (3) receiving routine care only. This study, involving women aged 67-70 years, took place in the screening (diagnosis) of breast cancer in the UK.

This study, involving women aged 67-70 years, took place in the screening (diagnosis) of breast cancer in the UK.

The Zahedan Medical University study enrolled 130 women who were randomly assigned to two groups: (1) to receive an educational program with written and oral materials focused on breast cancer prevention behavior (e.g., maintaining a healthy diet and being positive about breast self-examination), or (2) no intervention. This study included women aged 35-39years working at Zahedan Medical University.

Key outcomes

In these two studies, outcomes were measured (estimated) in different ways. In a study conducted by the Center for the Study of Breast Cancer in the UK, outcomes were assessed at one month, one year and two years after the intervention. In a study conducted at Zahedan Medical University, outcomes were assessed one month after the intervention. Because these studies varied widely in terms of age of participants, interventions, outcomes, and timing of their evaluation, their results are presented separately.

Knowledge about symptoms of breast cancer

According to the Center for Breast Cancer Research, women's knowledge of breast cancer symptoms appears to have improved after receiving a printed brochure or a printed brochure combined with oral conversation. Compared to usual (standard) care, these outcomes were better when assessed 2 years after the intervention. In a study conducted at the Zahedan Medical University, when assessed one month after the educational program, women's awareness of the symptoms of breast cancer increased.

Knowledge of age-related breast cancer risk

In a study by the Center for the Study of Breast Cancer: 2 years after the intervention, knowledge of age-related risk increased among women who received a printed brochure and consultation with a specialist, compared with usual (standard) care. Women who received only the brochure had lower rates of improvement in knowledge. The Zahedan Medical University study: only assessed women's self-assessment of breast cancer risk. This self-determination of risk did increase one month after the intervention.

Breast self-examination

In a study by the Center for Breast Cancer Research, 2 years after intervention, monthly breast self-examination rates increased, but not significantly, compared with usual (standard) care. In a study by Zahedan Medical University, women reported improved scores on breast cancer prevention behaviors one month after the intervention. In particular, this refers to their positive perception of preventive self-examination of the mammary glands.

General awareness of breast cancer

In a study by the Center for the Study of Breast Cancer: When assessed 2 years after intervention, women's awareness of breast cancer generally did not change after receiving the printed brochure alone, compared with usual (standard) care. However, among women who received not only a brochure, but also a personal consultation with a health professional, awareness of breast cancer has increased. Behavioral changes were compared with usual care 2 years after the interventions. The Zahedan Medical University study reported improvements in breast cancer prevention behaviors one month after the intervention.

Behavioral changes were compared with usual care 2 years after the interventions. The Zahedan Medical University study reported improvements in breast cancer prevention behaviors one month after the intervention.

None of the studies reported on other aspects of breast cancer awareness, intention to seek care, quality of life, adverse effects of interventions, or breast cancer-related outcomes.

Quality of evidence

The quality of the evidence was rated as moderate in the UK Breast Cancer Research Center study and low in the Zahedan Medical University study. None of the studies provided a clear definition of breast cancer awareness. The lack of high quality clinical trials limits our ability to draw definitive conclusions. However, findings from the UK Breast Cancer Research Center suggest that a combination of written information and face-to-face interviews has a long-term effect on raising women's awareness of breast cancer. In the future, larger studies (with more women) with longer follow-up periods are needed.

Translation notes:

Translation: Mirakova Kamilla. Editing: Kislyakova Alena Alekseevna, Yudina Ekaterina Viktorovna. Project coordination for translation into Russian: Cochrane Russia - Cochrane Russia (branch of the Northern Cochrane Center on the basis of Kazan Federal University). For questions related to this translation, please contact us at: [email protected]; [email protected]

"He just pisses me off!" How to deal with disobedient students?

Photos: Depositphotos / Illustrations: Yulia Zamzhitskaya

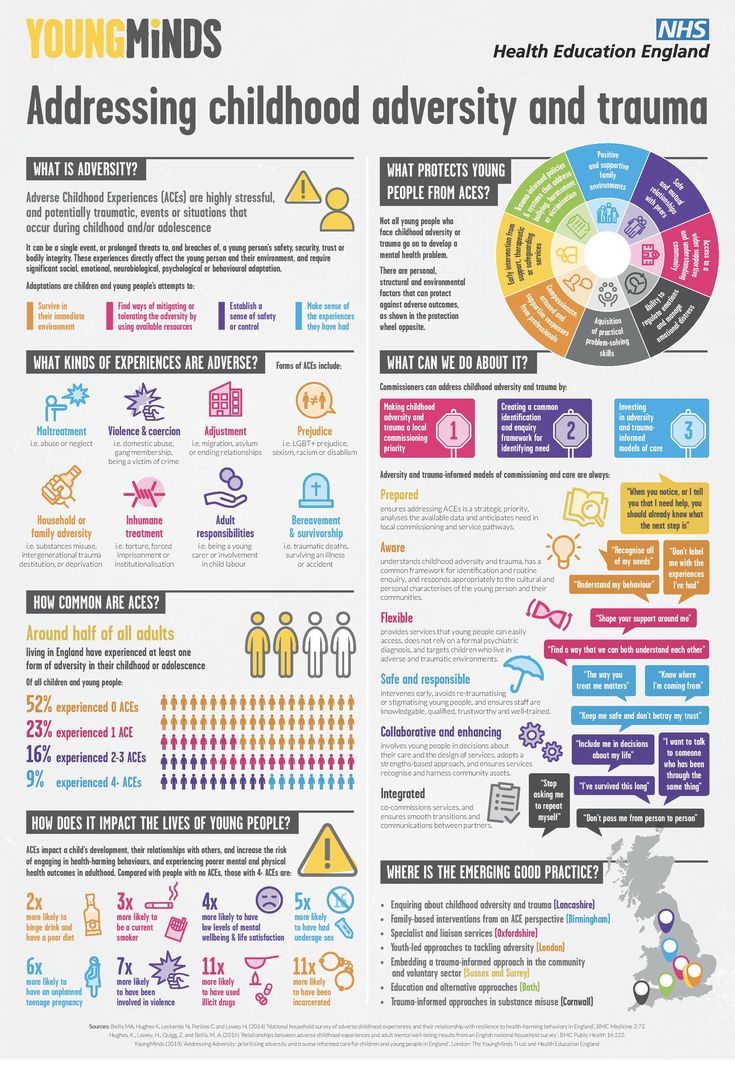

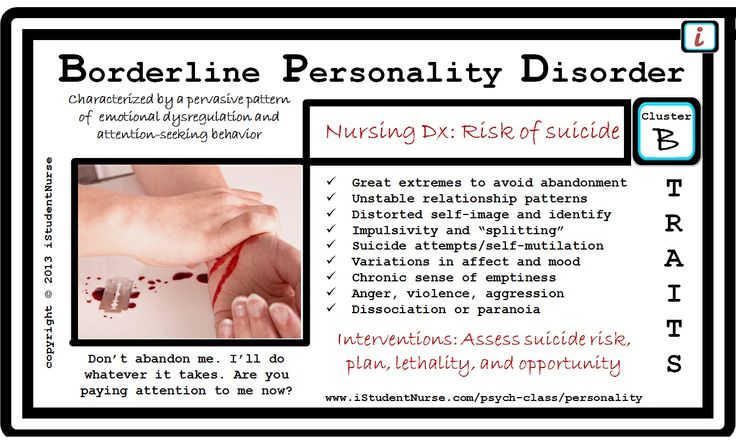

There are children who seem to deliberately wake up the "beast" in the teacher: they are daring, swearing, not reacting to remarks. They say about such people: "uncontrollable". Are there medical explanations for difficult behavior? How to organize work and not lose control over yourself if there is such a child in the class? We deal with Russian and Western experts on children's behavioral problems.

Any reason?

Pupils who put teachers at nothing are not uncommon not only in Russia, but also abroad. Bronwyn Harris, a longtime teacher from Oakland, California, has worked with many troubled students, but nonetheless she was not ready to meet one of them, third grader Antonio:

“Sometimes he would say no before I had even finished asking a question,” recalls Harris. - Once I said: "Hey, you don't even know what I wanted to ask you." He replied, “It doesn't matter. No!" Another time, the child simply patted him on the shoulder, and Antonio turned around and attacked him, waving his fists.”

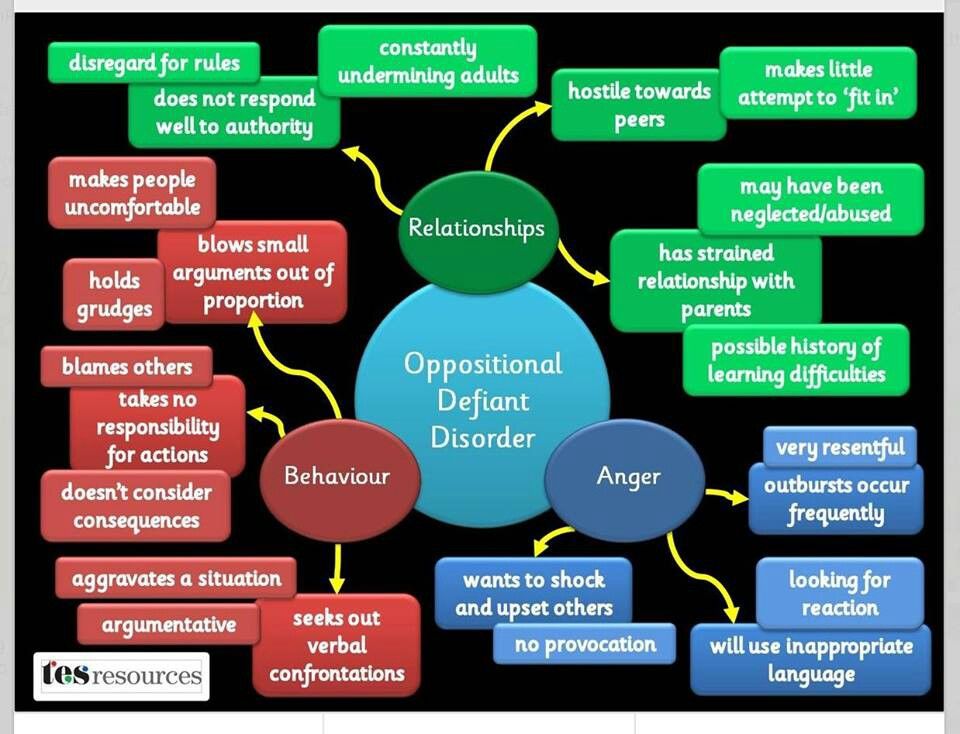

Bronwyn Harris contacted the boy's family and learned that he had been diagnosed with Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) - ed. ). According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, OAD is "a pattern of rebellious, hostile, and defiant behavior directed at authority figures." Children with this diagnosis refuse to cooperate, are defiant and hostile towards their peers, parents, teachers.

“One of my charges went to a special school for the sole reason that he couldn't control himself. Only in the first grade, he was already expelled from two schools. The child did not obey the teacher, was aggressive with peers, hostile to other adults. He ran out of the classroom, sent “three letters”, flipped desks, put up fights - ignoring the rules was habitual behavior for him, ”says Maria Buryka, a child clinical psychologist, a specialist in working with children with behavioral difficulties.

Get the profession of a teacher-organizer with the additional qualification "Social teacher" at the Training Center of the Teachers' Council.

What's in the program?

— Practice-oriented methods of work of a social pedagogue and an organizing teacher.

— Methods of social and pedagogical work with children left without parental care and dysfunctional families.

— Support for curators and feedback from teachers.

And what is the result?

A new profession and a diploma of professional retraining of the established sample.

Installment available.

Find out more

Where does OVR come from?

The causes of the diagnosis of Oppositional Defiant Disorder are not fully understood. Researchers put forward two theories:

- Developmental theory , according to which problems begin when children are still in infancy. Perhaps children and adolescents with ODD were emotionally attached to a parent or other significant adult and had difficulty learning to be independent of them.

- Learning theory which suggests that the negative symptoms of ODD are learned attitudes. Parents and other people in authority over the child use negative reinforcement methods—in short, punishment—to eliminate the unwanted behavior. At the same time, only unwanted behavior allows the child to get what he wants: attention and reaction from parents or other people.

In both cases, these are children who have received psychological trauma in the early stages of development. Like many of her colleagues, Bronwyn Harris had never heard of OID before, but after studying this diagnosis, she understood why, communicating with Antonio, she felt so exhausted and helpless.

“The difficult behavior of a child with ODD is not a reflection of a personal attitude towards us. This should be treated as a cry for help. These are the children whom adults could not help to cope with themselves, find their place in life, integrate into society. The feelings that arise when interacting with them are sometimes difficult and traumatic, but these experiences are a reflection of what the child himself feels - anger, powerlessness, deep sadness. There are probably no children who would need our acceptance, understanding and help more than others,” Maria Buryka explains.

In Russia, few have heard of such a diagnosis either. Although children who potentially have it are quite common. Experts say that it affects between 1 and 16 percent of students, and many of them remain undiagnosed. Despite the fact that most teachers have never worked with children with confirmed ODD, they note that in practice they constantly encounter opposition and disobedience from individual students.

Although children who potentially have it are quite common. Experts say that it affects between 1 and 16 percent of students, and many of them remain undiagnosed. Despite the fact that most teachers have never worked with children with confirmed ODD, they note that in practice they constantly encounter opposition and disobedience from individual students.

What should a teacher do?

Here are some strategies to help keep the classroom healthy and not lash out at your child.

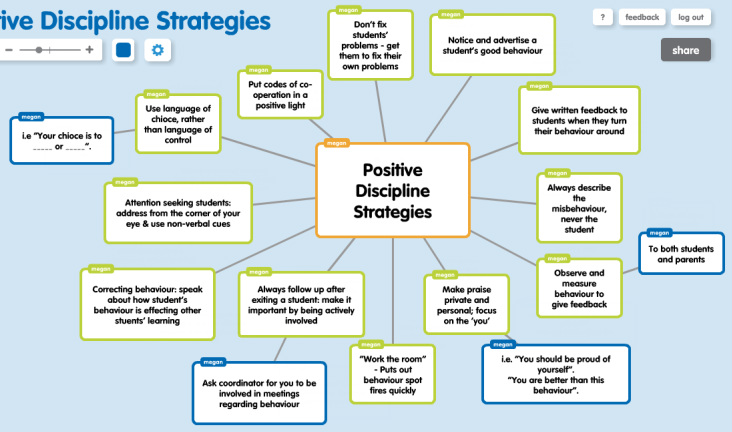

Set realistic goals.

Let's say you have a student who refuses to sit at a desk and instead makes a row and leaves the class. First determine what behavior you would like to see. Be realistic: if a child is used to leaving the classroom, then just staying in your place is already a big step for him.

Then collect the original data. How often does the child behave in the desired way? Zero percent of the time? Twenty percent?

"Baseline data will help you set smart goals and track growth," says David Anderson, senior director of the Child Brain Institute's Center for ADHD and Destructive Behavioral Disorders.

- Work to achieve the desired behavior using a combination of positive reinforcement and the predictable consequences of breaking the rules. Don't expect magic. Behavior change is slow and requires constant effort.”

Praise good behavior.

Children who exhibit challenging behavior receive a lot of negative attention. Turn your attention to the positive by giving specific feedback when you notice that the child is doing what you expect from him.

“But be aware that some of them are so accustomed to negative feedback that positive feedback can make them feel insecure. Be careful not to suddenly put them in the spotlight, as this can provoke a defensive reaction in the form of aggression. It may be better to compliment the student in a whisper or talk to him in private,” advises Rachel Lohmann, school counselor at Wake Young Men’s Leadership Academy (Raleigh, North Carolina).

Please wait before reacting.

Sometimes teachers unwittingly create conditions for disobedience by assuming the worst about a child.

“We can be so worried that a child will misbehave that we end up provoking him. But in many cases, he may not be going to misbehave. So take a deep breath and don't interfere unnecessarily. You may be able to avoid power struggles altogether, and you will be pleasantly surprised by the good behavior of the child, which can be praised, ”says David Anderson.

Talk to the class.

One student's challenging behavior affects the entire class, so it's important to discuss what's going on.

“One day, when Antonio was out of school, I talked to the class about how some people have more control over their feelings than others,” says Bronwyn Harris. “The students responded very well and were able to ignore his antics later on.”

Remember that students may not be as sensitive to destructive behavior as adults. David Anderson suggests that teachers address children with these words: “We all have moments when we lose our temper or have difficulty following directions. This is what we are working on as a class, and our task is to help each other.”

This is what we are working on as a class, and our task is to help each other.”

Call for help.

Ask a school psychologist for help. He can unobtrusively observe the student's behavior and his interaction with the teacher, as well as give useful advice on how to level the problem.

“Often these children just lose their temper, not understanding what exactly led to the outburst of anger. I teach them to identify triggers and tell them what to do when they get angry,” says Rachel Lohmann.

Professional retraining

Teacher of additional education with additional qualification "Social teacher"

More →>

Perhaps the psychologist will be able to work with the student individually or recommend a good specialist to his parents, to whom they can turn. It is worth noting that mothers and fathers are not always ready to cooperate with a teacher and a psychologist: they are so overwhelmed and exhausted by their own problems that they perceive with hostility any "interference" from the outside.

Create an emotional communication system.

Work with students to develop a communication system that allows them to communicate when they are at their emotional limits. You can use a scale from 1 to 10, where 10 means "everything is great" and 1 means "everything is very bad." Students can write numbers on cards and give them to the teacher before the lesson without showing them to classmates.

On those days when a student signals a high level of stress, you can allow him to work at his own pace without drawing too much attention to him.

Conclude a contract.

A "behavioral contract" can be made with high school students. It needs to define the behavior you want to see, as well as rewards and consequences for violating the terms of the "contract". At the same time, it is important not to make too high demands.

“If a student does not do his homework, he is more likely to start doing it partially than completely. You can draw the children's attention to the fact that they can ask for help with homework at a designated time.