Inability to connect with others disorder

Why You May Experience Emotional Detachment and What to Do About It

Emotional detachment is an inability or unwillingness to connect with other people on an emotional level. It may help protect some people from unwanted drama, anxiety, or stress.

For others, detachment isn’t always voluntary. Instead, it’s the result of events that make the person unable to be open and honest about their emotions.

Below you’ll read about the different types of emotional detachment and learn when it’s a good thing and when it might be worrisome.

Emotional detachment describes when you or others disengage or disconnect from other people’s emotions. It may stem from an unwillingness or an inability to connect with others.

There are two general types. In some cases, you may develop emotional detachment as a response to a difficult or stressful situation. In other cases, it may result from an underlying psychological condition.

Emotional detachment can be helpful if you use it purposefully, such as by setting boundaries with certain people or groups. Boundaries can help you maintain a healthy distance from people who demand much of your emotional attention.

But emotional detachment can also be harmful when you can’t control it. You may feel “numbed” or “muted.” This is known as emotional blunting, and it’s typically a symptom or issue that you should consider working with a mental health professional to address.

Learn more about emotional blunting here.

People who are emotionally detached or removed may experience symptoms such as:

- difficulty creating or maintaining personal relationships

- a lack of attention, or appearing preoccupied when around others

- difficulty being loving or affectionate with a family member

- avoiding people, activities, or places because they’re associated with past trauma

- reduced ability to express emotion

- difficulty empathizing with another person’s feelings

- not easily sharing emotions or feelings

- difficulty committing to another person or a relationship

- not making another person a priority when they should be

Emotional detachment can slowly build over time, or it may occur more rapidly in response to an acute situation. Though everyone is different, some signs and symptoms to watch for include:

Though everyone is different, some signs and symptoms to watch for include:

- inability to feel emotions or feeling empty

- losing interest in enjoyable activities

- becoming less involved in relationships

- showing little or no empathy toward others

- being harsh or unkind to others

If you suspect you may be developing emotional detachment, you should consider talking with your doctor. They can help identify your symptoms and recommend potential treatment options.

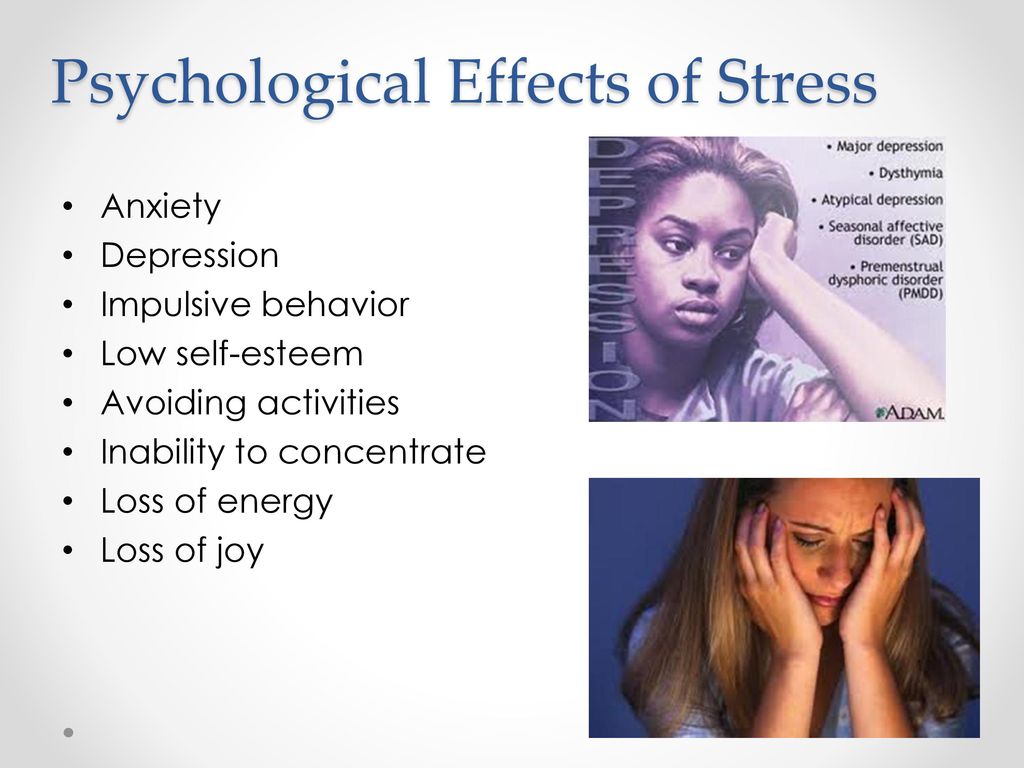

Emotional detachment may develop due to a variety of potential causes, which can include:

- constant exposure to bad or unpleasant news

- traumatic experience

- abuse

- side effects of certain medications

- conditioning as a child due to parental or cultural expectations

Emotional detachment may be voluntary. Some people can choose to remain emotionally removed from a person or situation.

Other times, emotional detachment results from trauma, abuse, or a previous encounter. In these cases, previous events may make it difficult to be open and honest with a friend, loved one, or significant other.

In these cases, previous events may make it difficult to be open and honest with a friend, loved one, or significant other.

By choice

Some people choose to proactively remove themselves from an emotional situation.

This might be an option if you have a family member or a colleague that you know upsets you greatly. You can choose not to engage with the person or persons. This will help you remain cool and keep calm when dealing with them.

In situations like this, emotional detachment is a bit like a protective measure. It helps you prepare for situations that may trigger a negative emotional response.

As a result of abuse

Sometimes, emotional detachment may result from traumatic events, such as childhood abuse or neglect. Children who live through abuse or neglect may develop emotional detachment as a means of survival.

Children require a lot of emotional connection from their parents or caregivers. If it’s not forthcoming, the children may stop expecting it. When that happens, they may begin to turn off their emotional receptors, as in the case of reactive attachment disorder (RAD). RAD is a condition in which children cannot form bonds with their parents or caregivers.

When that happens, they may begin to turn off their emotional receptors, as in the case of reactive attachment disorder (RAD). RAD is a condition in which children cannot form bonds with their parents or caregivers.

That can lead to depressed mood, inability to show or share emotions, and behavior problems.

Other conditions

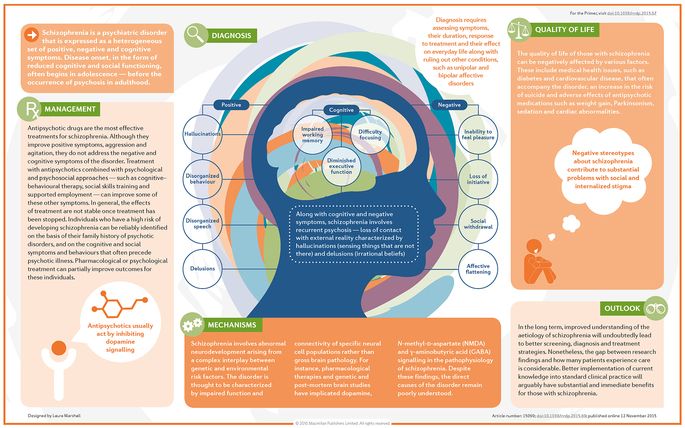

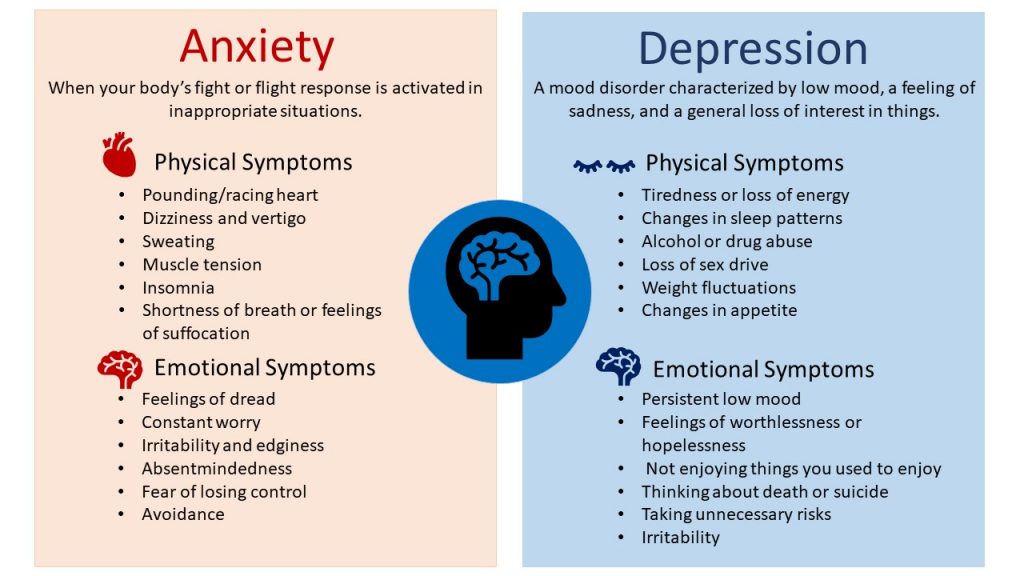

Emotional detachment or “numbing” is frequently a symptom of other conditions. You may feel distant from your emotions at times if you have:

- post-traumatic stress disorder

- bipolar disorder

- major depressive disorder

- personality disorders

Medication

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a type of antidepressant. Some people who take this type of drug may experience emotional blunting or a switched-off emotional center, particularly at higher doses.

This period of emotional detachment may last as long as you take these medications. Doctors can help you find another alternative or help to find the right dosage if the medication affects you in this way.

Emotional detachment isn’t an official condition like bipolar disorder or depression. Instead, it’s often considered one element of a larger medical condition.

Conditions might include personality disorders or attachment disorders.

Emotional detachment could also be the result of acute trauma or abuse.

A healthcare professional may be able to see when you’re not emotionally available to others. They may also talk with you, a family member, or a significant other about your behaviors.

Understanding how you feel and act can help a provider recognize a pattern that could suggest this emotional issue.

Asperger’s and emotional detachment

Contrary to popular belief, people living with Asperger’s, which forms part of the Autism spectrum disorder, are not cut off from their emotions or the emotions of others.

In fact, experts indicate they may feel others’ emotions more intensely even if they do not show typical outward signs of emotional involvement, such as changes in affect or facial expressions. This can lead to them taking additional steps to avoid hurting others, even at their own expense.

This can lead to them taking additional steps to avoid hurting others, even at their own expense.

Treatment for emotional detachment depends on the reason it’s occurring.

If your healthcare professional believes you’re experiencing problems with emotional attachment because of another condition, they may suggest treating that first.

These conditions might include depression, PTSD, or borderline personality disorder. Medication and therapy are often helpful for these conditions.

If the emotional detachment symptoms result from trauma, your doctor may recommend psychotherapy, also known as talk therapy. This treatment can help you learn to overcome the impacts of the abuse. You may also learn new ways to process experiences and anxieties that previously upset you and led to emotional detachment.

For some people, however, emotional distance isn’t problematic. In that case, you may not need to seek any treatment.

However, if problems with feeling or expressing emotions have caused issues in your personal life, you may want to seek out treatment or other support. A therapist or other mental health provider can provide treatment, though you may find that talking first to your primary care provider can help connect you with those who can help.

A therapist or other mental health provider can provide treatment, though you may find that talking first to your primary care provider can help connect you with those who can help.

For some people, emotional detachment is a way of coping with overwhelming people or activities. You choose when to be involved and when to step away.

In other cases, however, numbing yourself to emotions and feelings may not be healthy. Indeed, frequently “turning off” your emotions may lead to unhealthy behaviors, such as an inability to show empathy or a fear of commitment.

People that live through trauma or abuse may find it difficult to express emotions. This may cause people to seek other, negative outlets for those feelings, such as drug or alcohol misuse, higher risk sexual behaviors, or other behaviors that can lead to involvement with law enforcement.

Emotional detachment occurs when people willingly or unwillingly turn off their connection with their emotions. This may be intentional, such as a defensive mechanism on emotionally draining people, or unintentional due to an underlying condition or medication side effect.

If you have difficulty processing emotions or you live with someone who does, you may want to consider seeking help from a mental health provider. They can offer support and treatment to help you understand how you process emotions and respond to others and activities.

Why You May Experience Emotional Detachment and What to Do About It

Emotional detachment is an inability or unwillingness to connect with other people on an emotional level. It may help protect some people from unwanted drama, anxiety, or stress.

For others, detachment isn’t always voluntary. Instead, it’s the result of events that make the person unable to be open and honest about their emotions.

Below you’ll read about the different types of emotional detachment and learn when it’s a good thing and when it might be worrisome.

Emotional detachment describes when you or others disengage or disconnect from other people’s emotions. It may stem from an unwillingness or an inability to connect with others.

There are two general types. In some cases, you may develop emotional detachment as a response to a difficult or stressful situation. In other cases, it may result from an underlying psychological condition.

Emotional detachment can be helpful if you use it purposefully, such as by setting boundaries with certain people or groups. Boundaries can help you maintain a healthy distance from people who demand much of your emotional attention.

But emotional detachment can also be harmful when you can’t control it. You may feel “numbed” or “muted.” This is known as emotional blunting, and it’s typically a symptom or issue that you should consider working with a mental health professional to address.

Learn more about emotional blunting here.

People who are emotionally detached or removed may experience symptoms such as:

- difficulty creating or maintaining personal relationships

- a lack of attention, or appearing preoccupied when around others

- difficulty being loving or affectionate with a family member

- avoiding people, activities, or places because they’re associated with past trauma

- reduced ability to express emotion

- difficulty empathizing with another person’s feelings

- not easily sharing emotions or feelings

- difficulty committing to another person or a relationship

- not making another person a priority when they should be

Emotional detachment can slowly build over time, or it may occur more rapidly in response to an acute situation. Though everyone is different, some signs and symptoms to watch for include:

Though everyone is different, some signs and symptoms to watch for include:

- inability to feel emotions or feeling empty

- losing interest in enjoyable activities

- becoming less involved in relationships

- showing little or no empathy toward others

- being harsh or unkind to others

If you suspect you may be developing emotional detachment, you should consider talking with your doctor. They can help identify your symptoms and recommend potential treatment options.

Emotional detachment may develop due to a variety of potential causes, which can include:

- constant exposure to bad or unpleasant news

- traumatic experience

- abuse

- side effects of certain medications

- conditioning as a child due to parental or cultural expectations

Emotional detachment may be voluntary. Some people can choose to remain emotionally removed from a person or situation.

Other times, emotional detachment results from trauma, abuse, or a previous encounter. In these cases, previous events may make it difficult to be open and honest with a friend, loved one, or significant other.

In these cases, previous events may make it difficult to be open and honest with a friend, loved one, or significant other.

By choice

Some people choose to proactively remove themselves from an emotional situation.

This might be an option if you have a family member or a colleague that you know upsets you greatly. You can choose not to engage with the person or persons. This will help you remain cool and keep calm when dealing with them.

In situations like this, emotional detachment is a bit like a protective measure. It helps you prepare for situations that may trigger a negative emotional response.

As a result of abuse

Sometimes, emotional detachment may result from traumatic events, such as childhood abuse or neglect. Children who live through abuse or neglect may develop emotional detachment as a means of survival.

Children require a lot of emotional connection from their parents or caregivers. If it’s not forthcoming, the children may stop expecting it. When that happens, they may begin to turn off their emotional receptors, as in the case of reactive attachment disorder (RAD). RAD is a condition in which children cannot form bonds with their parents or caregivers.

When that happens, they may begin to turn off their emotional receptors, as in the case of reactive attachment disorder (RAD). RAD is a condition in which children cannot form bonds with their parents or caregivers.

That can lead to depressed mood, inability to show or share emotions, and behavior problems.

Other conditions

Emotional detachment or “numbing” is frequently a symptom of other conditions. You may feel distant from your emotions at times if you have:

- post-traumatic stress disorder

- bipolar disorder

- major depressive disorder

- personality disorders

Medication

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a type of antidepressant. Some people who take this type of drug may experience emotional blunting or a switched-off emotional center, particularly at higher doses.

This period of emotional detachment may last as long as you take these medications. Doctors can help you find another alternative or help to find the right dosage if the medication affects you in this way.

Emotional detachment isn’t an official condition like bipolar disorder or depression. Instead, it’s often considered one element of a larger medical condition.

Conditions might include personality disorders or attachment disorders.

Emotional detachment could also be the result of acute trauma or abuse.

A healthcare professional may be able to see when you’re not emotionally available to others. They may also talk with you, a family member, or a significant other about your behaviors.

Understanding how you feel and act can help a provider recognize a pattern that could suggest this emotional issue.

Asperger’s and emotional detachment

Contrary to popular belief, people living with Asperger’s, which forms part of the Autism spectrum disorder, are not cut off from their emotions or the emotions of others.

In fact, experts indicate they may feel others’ emotions more intensely even if they do not show typical outward signs of emotional involvement, such as changes in affect or facial expressions. This can lead to them taking additional steps to avoid hurting others, even at their own expense.

This can lead to them taking additional steps to avoid hurting others, even at their own expense.

Treatment for emotional detachment depends on the reason it’s occurring.

If your healthcare professional believes you’re experiencing problems with emotional attachment because of another condition, they may suggest treating that first.

These conditions might include depression, PTSD, or borderline personality disorder. Medication and therapy are often helpful for these conditions.

If the emotional detachment symptoms result from trauma, your doctor may recommend psychotherapy, also known as talk therapy. This treatment can help you learn to overcome the impacts of the abuse. You may also learn new ways to process experiences and anxieties that previously upset you and led to emotional detachment.

For some people, however, emotional distance isn’t problematic. In that case, you may not need to seek any treatment.

However, if problems with feeling or expressing emotions have caused issues in your personal life, you may want to seek out treatment or other support. A therapist or other mental health provider can provide treatment, though you may find that talking first to your primary care provider can help connect you with those who can help.

A therapist or other mental health provider can provide treatment, though you may find that talking first to your primary care provider can help connect you with those who can help.

For some people, emotional detachment is a way of coping with overwhelming people or activities. You choose when to be involved and when to step away.

In other cases, however, numbing yourself to emotions and feelings may not be healthy. Indeed, frequently “turning off” your emotions may lead to unhealthy behaviors, such as an inability to show empathy or a fear of commitment.

People that live through trauma or abuse may find it difficult to express emotions. This may cause people to seek other, negative outlets for those feelings, such as drug or alcohol misuse, higher risk sexual behaviors, or other behaviors that can lead to involvement with law enforcement.

Emotional detachment occurs when people willingly or unwillingly turn off their connection with their emotions. This may be intentional, such as a defensive mechanism on emotionally draining people, or unintentional due to an underlying condition or medication side effect.

If you have difficulty processing emotions or you live with someone who does, you may want to consider seeking help from a mental health provider. They can offer support and treatment to help you understand how you process emotions and respond to others and activities.

What is social phobia and how to live with it

Social phobia is a mental disorder in which a person experiences fear in situations involving communication with other people. Afisha Daily learned from people suffering from this disorder and a psychiatrist where social phobia comes from and how to live with it.

Antonina, 35 years old

For me, any communication is associated with tension and fear, with the exception of communication with close people: my husband, children, sister and, possibly, my mother. This is despite the fact that I am not a closed person and I like to communicate. But if I was invited somewhere, and then suddenly everything was canceled, I will feel relieved.

I rarely take the initiative - usually my friends or my husband invite me somewhere. By the way, it is much easier for me to go out somewhere in the company of my husband than alone, because he takes care of communication. Now I am rarely invited somewhere: my old friends have either left or they have small children. This makes me happy and sad at the same time.

Often, after communicating with a person, I feel very embarrassed because of the way I behaved all my attention. Therefore, I like to communicate with people who talk about themselves all the time and do not allow words to be inserted into the dialogue - I feel comfortable with them.

Often, after interacting with a person, I feel very acutely uncomfortable because of the way I behaved: I remember some phrase that I said, or I get the general impression that I behaved stupidly. This feeling, similar to shame, comes in waves for a couple more days, and it is very difficult for me to endure it - so much so that I can scratch my hands, scream sharply, or hit the wall with my fist.

When I worked, it was easy for me to communicate with colleagues: I was a system administrator, and I was interested in my colleagues as a professional, and not as an interlocutor. It’s easier for me when there is some kind of protocol for communication: I got on the minibus, handed over money, received change, sat down - everything is simple. It is much more difficult to do something new: go to an unfamiliar doctor in an unfamiliar hospital, organize a child’s birthday, get documents from an official. Such cases hang on me as a heavy burden, and if it works out, I ask someone else to do them for me.

I’m scared even to stand in line for a minibus, and when I last applied for a foreign passport, it came to panic - I was afraid that a live line would tear me apart

Superficial communication, the so-called small talk (translated from English "little conversation" - Note ed. ), because I don't know what I can talk about and how I should answer. I am constantly afraid to blurt out something wrong, I am afraid that people will laugh at me and call me strange.

For me, the worst thing is to be in a situation of real or potential aggression. I’m scared even to stand in line for a minibus, and when I last handed in my documents for a foreign passport, it came to panic - I was afraid that a live line would tear me apart. Perhaps this is due to my experience of bullying.

I cope with social phobia simply by adjusting the amount of social contact - sometimes I refuse something that I don't think I can handle. My relatives help me in some ways - for example, my husband goes to parent-teacher meetings.

There was a time in my life when almost any communication was scary, perceived as potentially dangerous. I went to a psychiatrist, and I was diagnosed with post-stress disorder, and then I was diagnosed with depression. After I began to treat depression, fear disappeared from communication, although it is still difficult for me.

Rina, 26 years old

Now I live in Vladimir — it's a small but very cool city. I work in a bookstore, do sketches for tattoos, and sometimes help design weddings. In addition, I run a telegram channel where I write about my mental disorder, among other things.

I work in a bookstore, do sketches for tattoos, and sometimes help design weddings. In addition, I run a telegram channel where I write about my mental disorder, among other things.

Social phobia is not my main diagnosis, the main one is bipolar disorder of the first type and mild schizophrenic disorder. It all started in 2011, which turned out to be especially difficult: I studied and worked, so I didn’t have time to stop and think about myself. I stayed in this mode for quite a long time, but closer to autumn, it began to cover me - I didn’t want to work or meet friends. I lived in constant tension, suffered from the fact that I did not have time to complete everything on time, and as a result, I became afraid to go to the office and communicate with people. Panic attacks happened to me in crowded places. I turned to my mother for advice, and she gave me the contacts of her psychotherapist. She prescribed drugs, from which I just slept 20 hours a day, and in the end I stopped working with her.

I irrationally wanted to hide under the closet - not under the bed, not in the closet, but in a narrow gap under it, where no one would definitely find me

At the end of the year, I had a serious breakdown. I got myself a week's vacation and went to a friend's place in Moscow. After working on vacation for a few days, I felt really bad. I remember how I sat in the room and was afraid to go into the kitchen, where my three friends were. I irrationally wanted to hide under the closet - not under the bed, not in the closet, but in a narrow gap under it, where no one would definitely find me. Then I was scared to ride the subway, because it is deep underground, and there are a lot of people there. When the noise of the trains became unbearable for me, I squatted down and covered my ears with my hands.

I went to see a psychologist, but not about social phobia. I was lucky with the specialists, and they diagnosed me with a bipolar disorder of the first type with abrupt transitions between phases, which means that I do not have intermissions, that is, relatively calm periods between manic and depressive phases.

Before I started treatment, I often just forced myself to communicate with people despite my fear. Now I have learned to notice in time when such a state comes over me, and try to limit communication until I feel better. It helps me a lot that my current social circle consists of people who accept my oddities and do not force me to communicate with them through force. Now I know for sure that I am an introvert, and I am comfortable limiting my communication to a couple of close friends. I know them very well, communication with them is predictable, I understand what to expect from them, and they know what they can expect from me.

The best compliment I received was from a girl who looked at me and said, "You know, you don't look like a person with problems at all." I was very happy - the prank was a success!

Unfortunately, I know many examples when people around do not consider mental disorder a real problem and dismiss the complaints of the one who suffers from it. A person who hears words like “Yes, you need a good man” and “Just clean the house” in his address does not feel better, and for some people, the symptoms of the disorder can only intensify from this. The best way to communicate with a person who even has panic attacks against the background of social phobia is simply not to pressure him, do not drag him to noisy parties and not be offended when he refuses to meet.

A person who hears words like “Yes, you need a good man” and “Just clean the house” in his address does not feel better, and for some people, the symptoms of the disorder can only intensify from this. The best way to communicate with a person who even has panic attacks against the background of social phobia is simply not to pressure him, do not drag him to noisy parties and not be offended when he refuses to meet.

Now I have learned to meet new people quite easily, but in most cases my new acquaintances do not cross the border of friendship. I think that in five years I will be able to successfully impersonate a completely normal person. By the way, the best compliment was given to me by one girl who looked at me and said: “You know, you don’t look like a person with problems at all.” I was very happy - the prank was a success!

Ayman, 21

I would like to talk about how social phobia can manifest itself in an autistic person. It is important that not all autistic people experience social phobia, and not all people with social phobia are autistic.

I experienced a state very close to the clinical understanding of social phobia when I was in school, now this problem is almost solved. Now I live in St. Petersburg and lead the Autistic Civil Rights Initiative, help LGBT people with disabilities in the Queer Peace project, and run the Neurodiversity in Russia and LGBTI+ Autistic websites.

When I was in school, I didn't feel safe. There was a feeling that I was in a totalitarian state, where at any moment they could take away my things (both children and teachers), hit me, and not let me go somewhere. I felt that I could not read and write what I wanted - I was afraid that they would ask me strange questions. I was bullied at school, so I was generally afraid to say anything. This is despite the fact that it was difficult for me to formulate my thoughts orally (this is a fairly common problem in autistic people). Even in those rare cases when I could say something (for example, when I understood how to ask classmates for a pen), I often opened my mouth and could not utter a word. Often I could not understand what was happening, because I seemed to be chained from the inside. I was thrown into a fever, my heart was beating strongly, and this was only when I tried to ask for a pen, what can I say about full communication.

Often I could not understand what was happening, because I seemed to be chained from the inside. I was thrown into a fever, my heart was beating strongly, and this was only when I tried to ask for a pen, what can I say about full communication.

Hearing the laughter of unfamiliar teenagers, I crossed to the other side of the street

The more important the conversation was for me, the more difficult it was to speak. This is paradoxical, because for such conversations I chose the words in advance, thinking through everything to the smallest detail. But I was afraid that after every word they would laugh at me, no matter what I said. It was also difficult to answer the teachers' questions - I could formulate only 5-10 percent of what I could say, but often I could not squeeze out even these 5-10 percent.

I got over my social phobia when I realized that I would not be left behind until I spoke. I began to forcibly squeeze out at least some word, at least a tenth of what I had thought through. I did it quickly so as not to look whether they were listening to me or not, not to think about the reaction of others and not be distracted. And so time after time - it was very scary.

I did it quickly so as not to look whether they were listening to me or not, not to think about the reaction of others and not be distracted. And so time after time - it was very scary.

During that period, I was frightened by any strange behavior of people, even strangers who did not even think of approaching me. I looked around when I was walking down the street and talking with someone close to me, and when I heard the laughter of unfamiliar teenagers, I crossed to the other side of the street. When they approached me to find out the time, I internally reacted to this as if they were trying to attack me. I was especially afraid of young people who looked like my classmates.

But one day I noticed that there were no more mental problems related specifically to speech. I was talking to a woman in the village I went to every summer, and I suddenly realized that, despite the fact that she is young, when I talk, I don’t feel like something is holding me down from the inside. It also helped to communicate with the girls in the village - I knew them for a long time and felt safer with them.

It also helped to communicate with the girls in the village - I knew them for a long time and felt safer with them.

My persistence in wanting to learn how to communicate and make friends also helped. When I got better, I forced myself to chat with strangers, such as a salesperson in a book or CD store. Sometimes I imagined myself as my sociable classmate - so the task turned from "overcoming fear" into "an exercise in the formulation of thoughts and acting skills."

It did not make it easier for me to formulate my thoughts orally, but the fear and the feeling of constraint were gone. I was able to communicate with any people in the same way as I communicated with my closest relatives.

Social phobia is a fairly common disorder. His characteristic feature is a feeling of intense irrational anxiety that is out of control. This anxiety manifests itself in situations related to communication, and very often such a reaction is caused by speaking in public - in a child, for example, this may be the answer at the blackboard at school. In this state, it may seem to a person that thoughts simply disappear from his head. There are also somatic manifestations: rapid breathing and palpitations, tension or, conversely, relaxation in the muscles, severe fatigue, discomfort in the stomach up to a sudden need to go to the toilet, even a hypertensive crisis is possible. From the outside, it looks like a person suddenly fell ill: he can turn pale, blush, tremble, his pupils dilate. And as soon as the cause of fear is removed, he will feel better.

In this state, it may seem to a person that thoughts simply disappear from his head. There are also somatic manifestations: rapid breathing and palpitations, tension or, conversely, relaxation in the muscles, severe fatigue, discomfort in the stomach up to a sudden need to go to the toilet, even a hypertensive crisis is possible. From the outside, it looks like a person suddenly fell ill: he can turn pale, blush, tremble, his pupils dilate. And as soon as the cause of fear is removed, he will feel better.

It is easier for such people to communicate with acquaintances, but it is still scary: it is scary to seem stupid, make a mistake, look funny. It is also common for women to worry a lot about their appearance. Also, it may seem to a person that something terrible will happen right now.

In especially severe cases, social phobia can result in such physiological manifestations as, for example, frequent urination. I know of a case where a woman suffering from this disorder moved around the city in such a way that she was always near the toilet. She was afraid to eat and drink outside the house, fearing that she would not be able to resist this urge.

She was afraid to eat and drink outside the house, fearing that she would not be able to resist this urge.

Puberty is a very disturbing period in itself, and if, for example, excessive family demands are imposed on it, social phobia may also arise

Social phobia can greatly complicate a person's life. For example, he may have serious difficulties in getting a job because he cannot pass an interview. Business contacts can also be given with great difficulty: it is difficult for a person with social phobia to participate in discussions, especially with strangers whom he meets for the first time. It is also difficult for him to concentrate on work or study, his productivity and academic performance suffer. Sometimes a person with social phobia may lose a job because from the outside it may seem that he is lazy and does nothing all day. But in fact, he is not lazy, but endlessly scrolls his catastrophic scenario in his head, experiences fear.

Most often, social phobia manifests itself in adolescence. Puberty is a very disturbing period in itself, and if, for example, excessive family requirements are superimposed on it, social phobia may also occur. We have all experienced this: when parents do not praise their children, but, on the contrary, devalue their feelings and strongly criticize, focus on failures instead of achievements.

Puberty is a very disturbing period in itself, and if, for example, excessive family requirements are superimposed on it, social phobia may also occur. We have all experienced this: when parents do not praise their children, but, on the contrary, devalue their feelings and strongly criticize, focus on failures instead of achievements.

Parents often do not take seriously the onset of social phobia. For example, if a student received a deuce, parents will simply drive him to retake, thinking that he did not learn the lesson, while he simply cannot bear the very situation of the exam. Anxiety disorders tend to develop, and in some cases they can develop into panic disorders, and to such an extent that the person may require hospital treatment.

A person who lives with social phobia develops an avoidance reaction, he can come up with rather complicated ways to avoid situations that frighten him. For example, if he is afraid to make a presentation, he can write the perfect text and ask another person to speak with him.

Unfortunately, it is still not customary for us to go to psychologists and psychiatrists because of the stigma surrounding these professions. Now there are effective methods of treatment of social phobia. A psychotherapist is involved in the treatment, and often he does without medication. In cases where therapy is not enough, antidepressants may be prescribed. Someone can cope with social phobia on their own, simply by reading the relevant literature - cases of self-healing are known. But with the help of a therapist, getting rid of fear is, of course, better. Parents should listen to their children. If, for example, a teenager is a good student, but something prevents him from speaking in front of the class, it is worth helping him cope with this problem at the initial stage. It will only help him in the future.

tell your friends

tags

sociophobiapsychologypsychiatryphobia

What is non-verbal learning disorder and how can I help my child?

Many people think that the term "learning disorder" only covers problems with verbal skills, like reading or writing.

These are the classic signs of Nonverbal Learning Disorder (NVLD / NLD). Nonverbal learning disorder (NVLD) affects skills such as abstract thinking and organization. NRA affects your child's learning ability, but creates even more problems when it comes to communication. Learn more about NRA and how to help your child.

What is Nonverbal Learning Disorder?

Learning and attention disorders create difficulties in communication. The NRA affects a child's social skills, but not their speaking or writing skills.

Children with non-verbal learning disorder tend to talk a lot, but they don't always manage to do it in acceptable ways. They often miss important information, don't understand sign language, so it's hard for them to make friends, and there can often be misunderstandings with teachers, parents, and other adults.

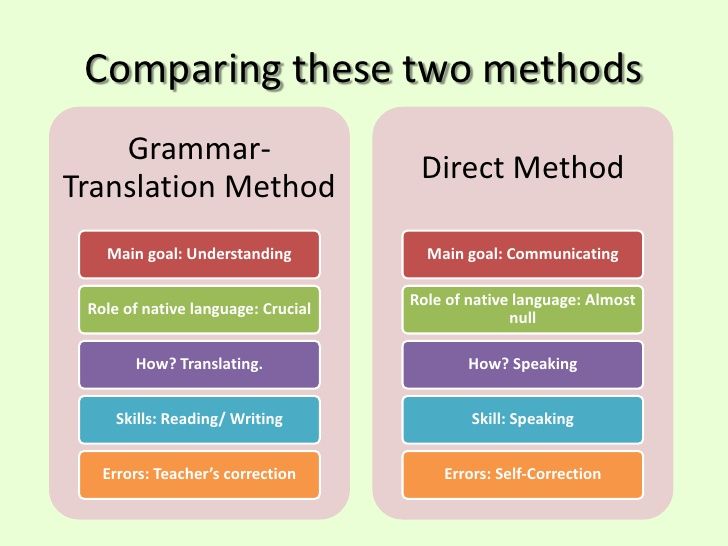

In contrast to children with learning disorders related to speech and writing (dyslexia, dysgraphia), children with NDE have difficulty understanding non-verbal communication. This includes body language, intonation, and facial expressions.

When a classmate says something sarcastic, a child with non-verbal learning disorder may take it literally. He may laugh at something serious because the speaker is smiling. Due to the fact that the child does not understand the non-verbal subtext to words, it is difficult for him to make friends.

In order to better understand what NLR is, it is necessary to learn more about learning disorders based on speech developmental problems. Children with these problems have difficulty reading, writing, and speaking. Their speech and language skills are weak and they have difficulty with accuracy and processing speed.

Some children with NDE have good language skills but have difficulty analyzing information and understanding hidden meanings. They may not have problems with written or spoken language, but they take information literally without understanding the subtext.

The exact cause of NRO is not yet clear, but researchers believe that this is due to a lack of coordination in different brain processes located in the left and right areas of the brain.

Despite growing awareness of this disorder, nonverbal learning disorder is controversial in medical circles. It does not appear in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the most recent update of the manual used by therapists to diagnose learning disorders.

Non-verbal learning disorder may cause learning difficulties, but this does not mean that a child with NVD is not smart. Like most children with learning disabilities, children with LLD usually have average or above average intelligence.

It is also important to know that non-verbal learning disorder is not the same as Asperger's or autism, although they can also affect social skills and social interaction.

How common is non-verbal learning disorder?

It is difficult to know exactly how many children an NRA has. This is because there is no clear definition of what this category of learning disorder includes. Studies show that the NRA may have 1% of children in the United States. This applies equally to boys and girls. Apparently, NRO is not inherited, as, for example, problems with concentration and dyslexia.

Non-verbal learning disorder often occurs in people with Asperger's syndrome. In fact, studies show that up to 80% of children with Asperger's have symptoms associated with NRO. People with ADHD may also experience symptoms of NRO, although there are no statistical data on this yet.

What causes NRA?

Experts don't know the exact cause of NRA symptoms. But they are exploring a number of theories related to differences in important brain processes and functions in the left and right sides of the brain.

There is no consensus among experts as to whether non-verbal learning disorder exists and what are the underlying causes of NLD symptoms. For example, some experts believe that problems may be caused by damage or developmental features of the part of the brain that coordinates the work of the two hemispheres. Others believe that the problems may be related to the frontal lobe of the brain, which is responsible for executive function skills such as working memory, organization and planning.

Help your child overcome learning difficulties quickly and permanently!

Learn more

What are the symptoms of NRA?

The main symptoms of non-verbal learning disorder include poor social skills, but NVE can manifest itself in other ways. For example, children with NDE may have difficulty with math, reading comprehension, writing, and/or physical coordination. Here are some of the symptoms you may find in your child with NRO:

-

Remembers information but does not know why it is important;

-

Communicates in socially unacceptable ways;

-

Pays attention to details but does not see the big picture;

-

Has difficulty reading;

-

Has difficulty with mathematics, especially with problems;

-

Physically awkward and clumsy;

-

Poor handwriting;

-

Takes information literally;

-

Does not understand intonation, body language, facial expressions;

-

Poor social skills;

-

violates the personal boundaries of others - may stand too close to the interlocutor;

-

Pays no attention to other people's reactions;

-

Changes subject abruptly;

-

Too dependent on parents;

-

Afraid to be in an unusual situation;

-

Has difficulty adjusting to change.

Children with ADHD are often misunderstood because of their behavior. Peers and adults may find them strange or immature. Not knowing that the child has NRO, the teacher may think that he is inattentive or cocky.

Symptoms may change with age.

Young children with nonverbal learning disorder may appear bright and precocious because they have good verbal skills. They, like little professors, ask adults a lot of questions and spew out the information received like a fountain.

Despite their good memory, they may find it difficult to interpret and draw conclusions from what they read.

As children get older, the symptoms of NRO may become more obvious and cause more problems. Children understand that they perceive social situations differently than their peers, but do not know what to do with it. Some develop anxiety that can lead to compulsive behavior, such as touching a doorknob a certain number of times before opening the door.

The sooner you know about your child's problems, the sooner you can find treatments and strategies to improve social skills and relieve anxiety.

What skills are affected by non-verbal learning disorder?

NLL does not affect all children in the same way, but for most children NLL affects the following skills:

-

Conceptual Skills: Difficulties with problem solving, understanding big concepts and cause and effect relationships.

-

Motor skills: problems with coordination and movement. This includes gross motor skills (such as running), fine motor skills (such as writing), and balance (such as cycling).

-

Visual-spatial skills: problems with visual images, visual processing and spatial relationships. The child may remember what he heard, but not what he saw.

-

Social skills: Difficulty sharing information in a socially acceptable way. The child may not understand sarcasm or facial expressions, may interrupt the interlocutor in the middle of a conversation.

-

Abstract and critical thinking: problem with reading comprehension and understanding the "big picture". A child may be good at remembering details but not understanding the larger concepts behind them. You may also have trouble organizing your thoughts.

How to recognize NRA?

Since there is no universally accepted test for HRO, the diagnostic process involves several steps:

Step 1: Get a medical examination. Your child's doctor probably isn't an expert on learning disorders, but you can talk to them about your concerns and find out if a medical condition might be causing your child's symptoms. Your doctor can help you find a specialist, such as a neurologist, for further evaluation.

Step 2: Get a referral to a mental health professional. Once the medical causes are corrected, your child's doctor will likely refer you to a mental health professional such as a neurologist. The specialist will talk to you and your child about your concerns. He will then administer various tests to assess your child's ability in the following areas:

-

Speech and language: Development of speech in young children; verbal skills, understanding of abstract ideas and context in older children.

-

Visuospatial Organization: The ability to draw a parallel between visual information and abstract concepts, such as reading a map or telling time by a clock.

-

Motor skills: Fine motor skills such as drawing and writing and gross motor skills such as the ability to throw and catch objects.

The specialist will look at your child's performance in these skills and ask you about the symptoms you have noticed in your child.

Step 3: Analyze the received information. After collecting all the information, the specialist will look for the strengths and weaknesses that are characteristic of children with ADHD. This will help determine if your child has a disability.

General strengths:

-

The level of intelligence is average or above average;

-

Good verbal skills;

-

Early speech development;

-

Good memory and ability to repeat what was said;

-

Learns better what he heard than what he saw.

General weaknesses:

-

Social skills;

-

Balance, coordination, handwriting;

-

Understanding cause and effect;

-

Visualization of information;

-

Activity level (higher at a young age, decreases with age).

What disorders are associated with NRO?

Nonverbal learning disorder is the disorder most closely associated with problems with social skills. However, there are several other disorders that prevent children from making friends. These disorders are not related, but they may occur together with NMR:

-

ADHD: Children with ADHD may initially be misdiagnosed with ADHD.

Both deviations have similar symptoms, such as excessive talkativeness, poor coordination and the habit of interrupting the interlocutor. But ADHD is not a learning disorder. This is a brain disorder that makes it difficult for children to concentrate, think about consequences, and control impulses.

-

Speech development disorders: these are problems with speech (expressive speech development disorder) and language understanding (receptive speech development disorder). Children with these disabilities find it difficult to understand and use sign language, follow directions, and carry on a conversation. NRO may also resemble some of the symptoms of social communication disorder.

-

Asperger's Syndrome: This is a developmental disorder that affects a child's ability to socialize and communicate with others. This is a mild form of autism. Many of the symptoms of Asperger's Syndrome and NRO overlap, and researchers suggest that about 80% of children with Asperger's Syndrome also have NRO.

But these are two separate disorders.

"We have the potential to help children who are lagging behind reach the norm and even exceed it!"

Watch part of Dr. Michael Merzenich's TED talk in 2004 where he talks about brain plasticity-based techniques to correct the workings in a child's brain to increase their ability to recognize speech, speak, read and learn successfully.

How can professionals help with NRA?

There are a number of treatments and educational strategies that can help your child manage the symptoms of NMO. These include:

-

Social skills training groups where children are taught how to behave in social situations, such as how to greet a friend, join a conversation, and recognize and respond to teasing.

-

Parental support from a psychologist is needed to help parents learn how to cooperate with teachers and help children improve their social skills.

-

Occupational therapy helps reduce fear of the unknown, improve coordination and improve fine motor skills.

-

Cognitive therapy helps to cope with anxiety and other types of mental disorders.

-

Talk to teachers about how to help your child do well in school.

What can you do at home?

Parenting a child with ADHD can be challenging, but there are many things you can do at home to help your child cope with symptoms and learn social skills. You can also try some of the behavior experts' strategies. These steps can help you make positive changes in your child's life and in your family life:

-

Think about how you speak. Remember that children with NRA are not good at understanding sarcasm and intonation, and they are likely to take what you say literally. For example, if you say, “If I see that thing in your hands again…,” he may continue to play with the prohibited item, turning away so that you cannot see it. Give clear instructions such as, "Please don't touch this thing."

-

Help with transitions. Children with NRO tend to dislike change because it is difficult for them to understand it. They may not have the abstract thinking skills needed to imagine what's next. You can prepare your child for routine changes by using logical explanations. Instead of saying, “We're going to have dinner with grandma soon,” try, “We're going to have lunch at grandma's house tonight because it's her birthday. We leave in an hour."

-

Watch your child.

A child with NRO may be shocked by sudden external stimuli such as noise, smells, sounds, and temperature. Try to avoid situations that may trigger shock reactions in your child.

-

Arrange meetings with friends. Help your child find friends with similar interests, whether it's a love of comics or cooking. Invite friends over for a social experience in a familiar setting. Think about what the children will do, offer them games so that they do not sit idle. It is also best to invite guests at times of the day when the child is usually well-behaved.

Use the Fast ForWord neurological online method. It is also called "Brain Fitness". By studying Fast ForWord at home, your child will train brain areas responsible for key executive functions, reading, speech skills, concentration skills, develop memory and other important cognitive skills necessary for successful learning and socialization. Thanks to these activities, more than 3 million children in the world have left special education.

What can make learning easier?

There are many ways to support your child with NRO:

-

Take notes. Monitor the child's behaviors and symptoms, when and where they occur. Your observations will be valuable information for professionals who can help your child.

-

Tell your child's doctor about your findings to discuss possible next steps. This may include a referral to a psychologist who can conduct a comprehensive assessment and develop a treatment plan.

-

Talk to your child's teacher to find out what problems your child is having at school. Ask what methods of assistance have been used and which ones are most effective. Discuss with teachers if the child needs special education.

-

Contact other parents. Discuss your observations with parents who have experienced similar problems, perhaps they can share their successful experience with you.

Nonverbal learning disorder can cause both social and academic problems for your child and there is no proven cure.