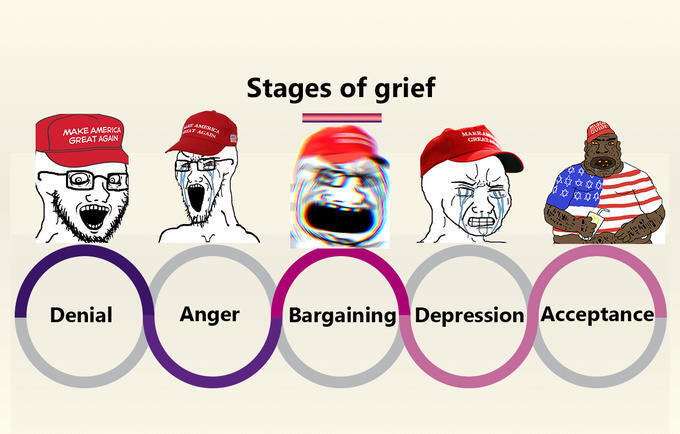

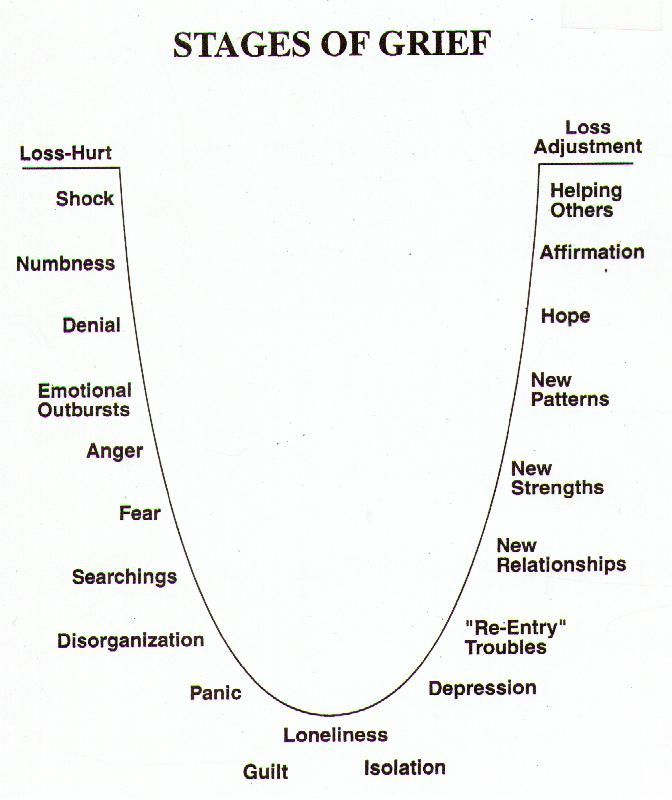

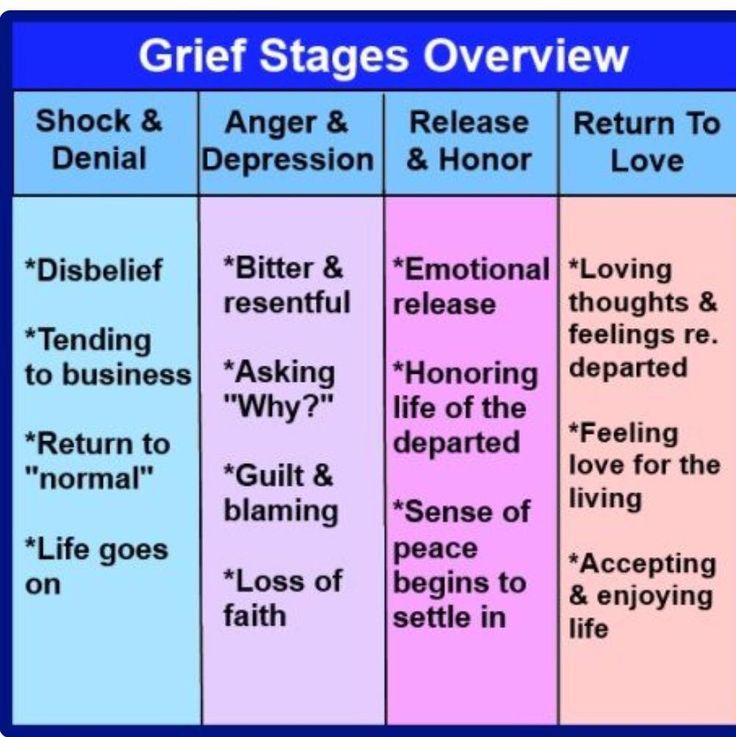

Stages grief chart

Five Stages Of Grief - Understanding the Kubler-Ross Model

Depression

An Examination of the Kubler-Ross Model

The Editors of Psycom

iStockPhoto.com/PeopleImages

Grief Model Background

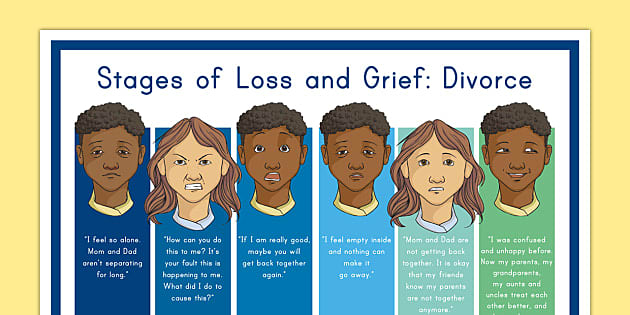

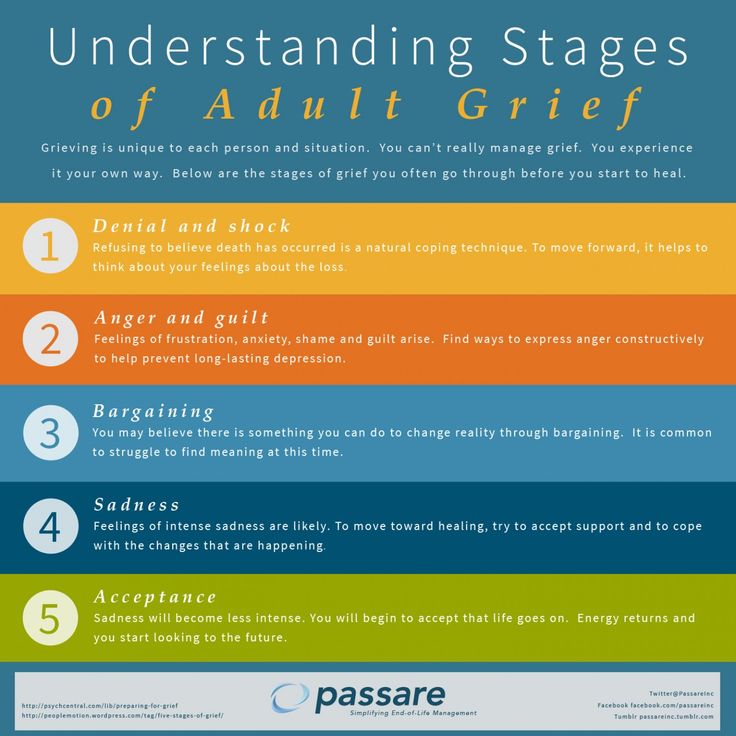

Throughout life, we experience many instances of grief. Children may grieve a divorce, a wife may grieve the death of her husband, a teenager might grieve the ending of a relationship, or you might have grieved the loss of a pet.

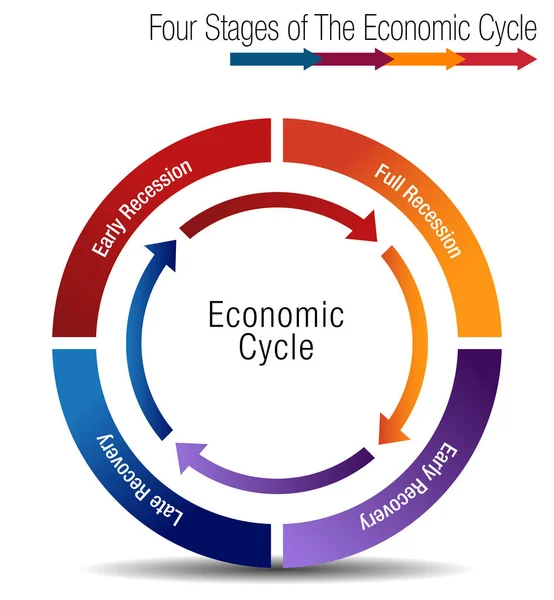

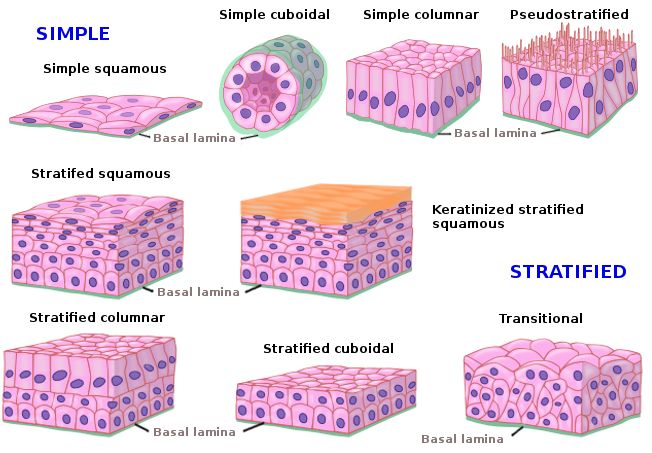

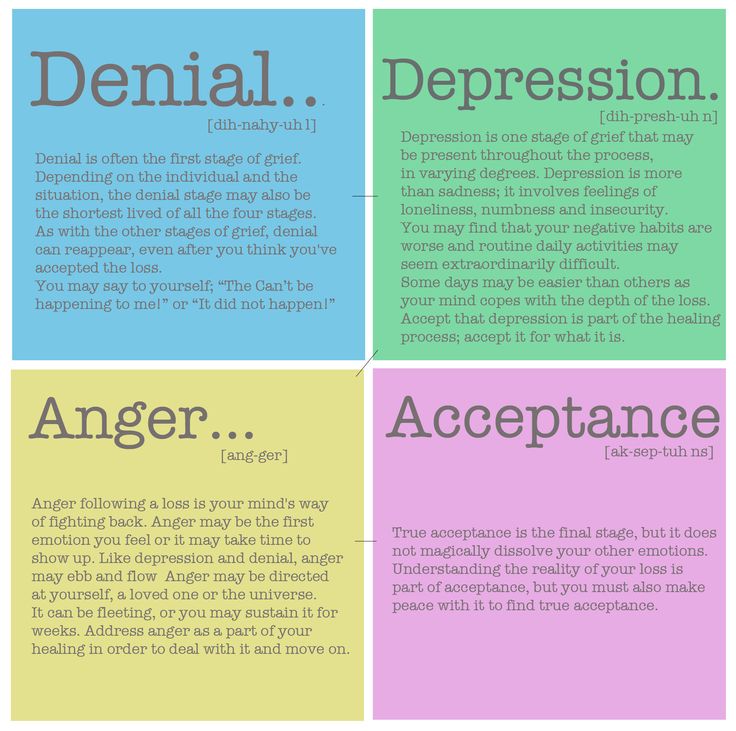

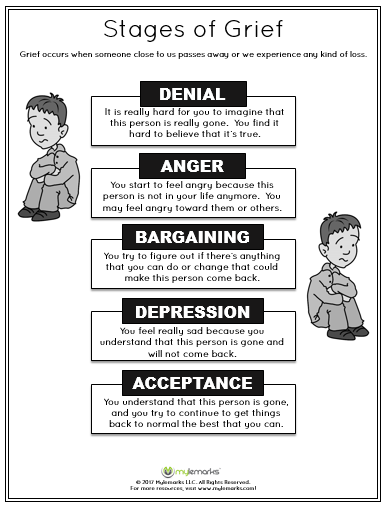

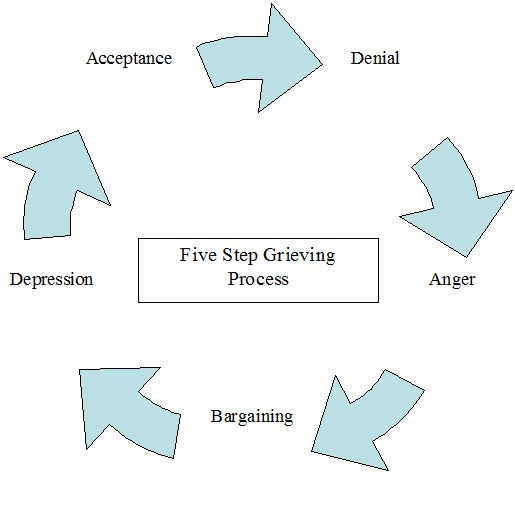

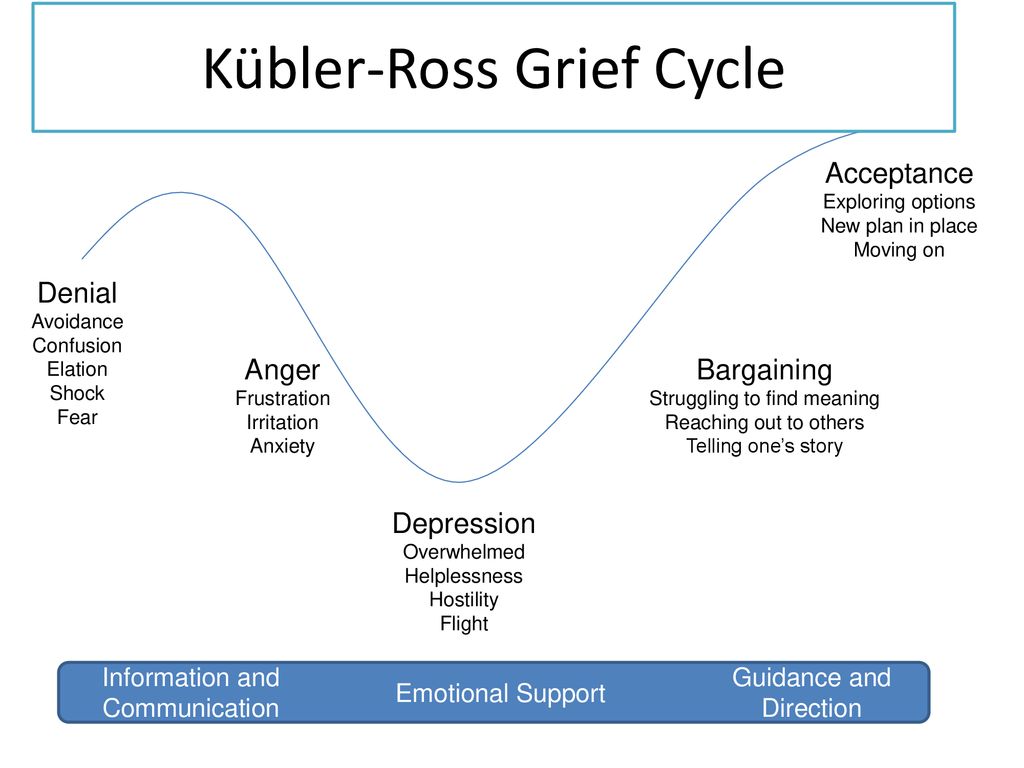

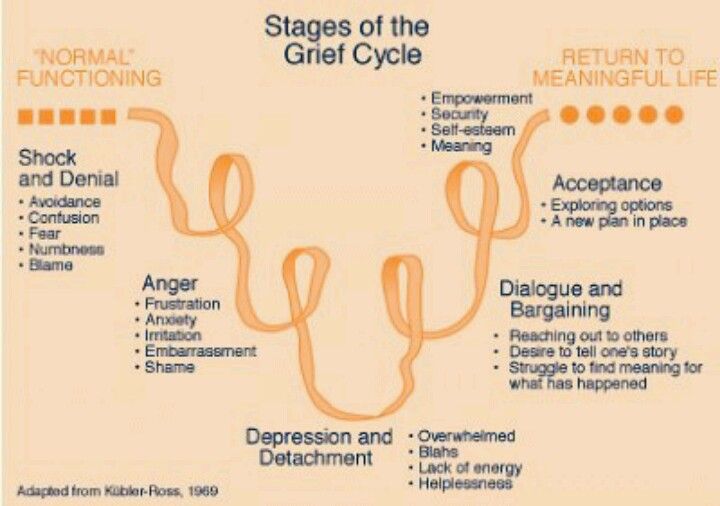

In 1969, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross described five common stages of grief, popularly referred to as DABDA. They include:

Denial

Anger

Bargaining

Depression

Acceptance

A Swiss psychiatrist, Kübler-Ross first introduced her five stage grief model in her book

On Death and Dying. Kübler-Ross’ model was based on her work with terminally ill patients and has been the subject of debate and criticism in the years since. Mainly, because people studying her model mistakenly believed this is the specific order in which people grieve and that all people go through all stages.

Kübler-Ross now notes that these stages are not linear and some people may not experience any of them. Others might only undergo a few stages rather than all five. It is now more readily known that these five stages of grief are the most commonly observed in the grieving population.

So, What Are The Five Stages?

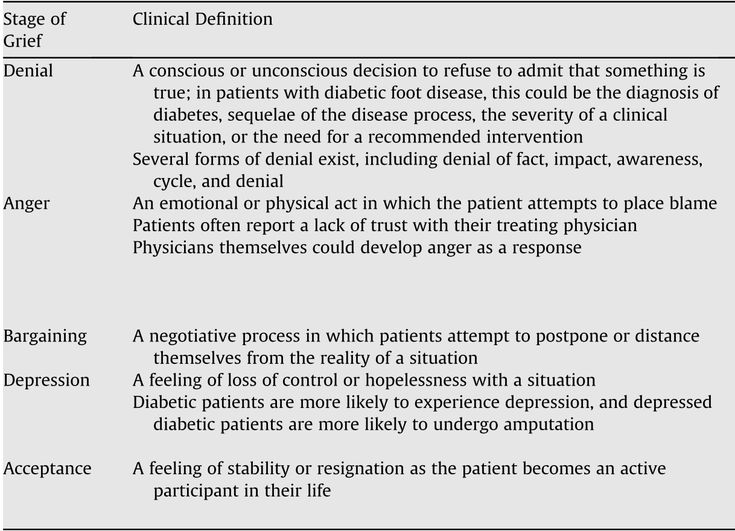

Denial

Denial is the stage that can initially help you survive the loss. You might think life makes no sense, has no meaning, and is too overwhelming. You start to deny the news and, in effect, go numb.

It's common in this stage to wonder how life will go on in this different state—you are in a state of shock because life as you once knew it has changed in an instant. If you were diagnosed with a deadly disease, you might believe the news is incorrect—a mistake must have occurred somewhere in the lab; they mixed up your blood work with someone else's. If you receive news of the death of a loved one, perhaps you cling to a false hope that they identified the wrong person. In the denial stage, you are not living in "actual reality," rather, you are living in a "preferable" reality.

If you receive news of the death of a loved one, perhaps you cling to a false hope that they identified the wrong person. In the denial stage, you are not living in "actual reality," rather, you are living in a "preferable" reality.

Interestingly, it is denial and shock that help you cope and survive the grief event. Denial aids in pacing your feelings of grief. Instead of becoming completely overwhelmed with grief, we deny it, do not accept it, and stagger its full impact on us. Think of it as your body's natural defense mechanism, saying "Hey, there's only so much I can handle at once."

Once the denial and shock start to fade, the healing process begins. At this point, those feelings that you were once suppressing are coming to the surface.

Once you start to live in "actual" reality again, anger might start to set in. This is a common stage to think "Why me?" and "Life's not fair!" You might look to blame others for the cause of your grief and also may redirect your anger to close friends and family. You find it incomprehensible how something like this could happen to you. If you are strong in faith, you might start to question your belief in God: Where is God? Why didn't he protect me?

You find it incomprehensible how something like this could happen to you. If you are strong in faith, you might start to question your belief in God: Where is God? Why didn't he protect me?

Researchers and mental health professionals agree that this anger is a necessary stage of grief. And encourage the anger. It's important to truly feel the anger. Even though it might seem like you are in an endless cycle of anger, it will dissipate—and the more you truly feel the anger, the more quickly it will dissipate, and the more quickly you will heal. It is not healthy to suppress your feelings of anger—it is a natural response—and perhaps, arguably, a necessary one.

(However, while suppressing anger is not advised, neither is letting it control you. It's important to seek help from a trained counselor or therapist if you are struggling with processing your anger.)

In everyday life, we are normally told to control our anger toward situations and toward others. When you experience a grief event, you might feel disconnected from reality, that you have no grounding anymore. Your life has shattered and there's nothing solid to hold onto. Think of anger as a strength to bind you to reality. You might feel deserted or abandoned during a grief event. That no one is there. You are alone in this world. The direction of anger toward something or somebody is what might bridge you back to reality and connect you to people again. It is a "thing." It's something to grasp onto, a natural step in healing.

Your life has shattered and there's nothing solid to hold onto. Think of anger as a strength to bind you to reality. You might feel deserted or abandoned during a grief event. That no one is there. You are alone in this world. The direction of anger toward something or somebody is what might bridge you back to reality and connect you to people again. It is a "thing." It's something to grasp onto, a natural step in healing.

Bargaining

When something bad happens, have you ever found yourself making a deal with God? "Please God, if you heal my husband, I will strive to be the best wife I can ever be, and never complain again." This is bargaining.

In a way, this stage is false hope. You might falsely make yourself believe that you can avoid the grief through this type of negotiation. If you change this, I'll change that. You are so desperate to get your life back to how it was before the grief event, you are willing to make a major life change in an attempt toward normality.

Guilt is a common wingman of bargaining. This is when you can experience a seemingly endless string of "what ifs": What if I had left the house 5 minutes sooner? The accident would have never happened. What if I encouraged him to go to the doctor six months ago like I first thought? The cancer could have been found sooner and he could have been saved.

Depression

Depression is commonly associated with grief. It can be a reaction to the emptiness we feel when we are living in reality and realize the person or situation is gone or over. In this stage, you might withdraw from life, feel numb, live in a fog, and not want to get out of bed. The world might seem too much and too overwhelming for you to face. You might not want to be around others or feel like talking, and you might feel hopeless. You might even experience suicidal thoughts, thinking "What's the point of going on?"

Acceptance

The last stage of grief identified by Kübler-Ross is acceptance. Not in the sense that "it's OK my husband died" but rather, "my husband died, but I'm going to be OK."

Not in the sense that "it's OK my husband died" but rather, "my husband died, but I'm going to be OK."

In this stage, your emotions may begin to stabilize. You re-enter reality. You come to terms with the fact that the "new" reality is your partner is never coming back, or that you are going to succumb to your illness. It's not a "good" thing, but it's something you can move forward from.

It is definitely a time of adjustment and readjustment. There are good days, there are bad days, and then there are good days again. In this stage, it does not mean you'll never have another bad day, where you are uncontrollably sad. But, the good days tend to outnumber the bad days.

In this stage, you may lift from your fog, start to engage with friends again, and might even make new relationships as time goes on. You understand your loved one can never be replaced, but you move, grow, and evolve into your new reality.

Symptoms of Grief

Your grief symptoms may present themselves physically, socially, mentally, emotionally, or spiritually. Some of the most common symptoms of grief are presented below:

Some of the most common symptoms of grief are presented below:

Crying

Headaches

Difficulty sleeping

Questioning the purpose of life

Questioning your spiritual beliefs (e.g., your belief in God)

Feelings of detachment

Isolation from friends and family

Abnormal behavior

Worry

Anxiety

Frustration

Guilt

Fatigue

Anger

Loss of appetite

Aches and pains

Stress

Treatment of Grief

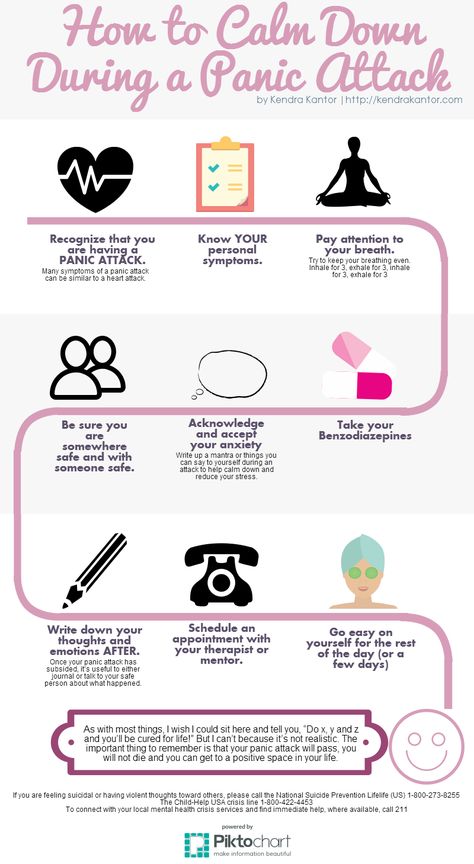

Counseling, along with medication when needed, have been the most common methods of treating grief. Initially, your doctor may prescribe you medications to help you function more fully. These might include sedatives, antidepressants, or anti-anxiety medications to help you get through the day. In addition, your doctor might prescribe medication to help you sleep.

However, the use of medication in grief treatment is controversial. Some providers believe it can mask feelings that arise as one goes through the grief process, and potentially delay healing. But you and your physican can determine a treatment plan that's best for you.

Counseling is a more solid approach to grief. Support groups, bereavement groups, or individual counseling can help you work through unresolved grief. This is a beneficial treatment alternative when you find the grief event is creating obstacles in your everyday life and you are having trouble functioning.

This support in no way "cures" you of your loss, rather, it provides you with coping strategies to help you deal with your grief in an effective way. The Kübler-Ross Model is a tried and true guideline, but there is no right or wrong way to work through your grief. Personal experiences may vary as people move among the stages of grief.

If you or a loved one is having a hard time coping with a grief event, seek treatment from a health professional or mental health provider. Call a doctor right away if you experience thoughts of suicide, feelings of detachment for more than two weeks, you experience a sudden change in behavior, or believe you are suffering from depression.

Call a doctor right away if you experience thoughts of suicide, feelings of detachment for more than two weeks, you experience a sudden change in behavior, or believe you are suffering from depression.

Notes: This article was originally published March 22, 2016 and most recently updated June 7, 2022.

Five Stages Of Grief - Understanding the Kubler-Ross Model

Depression

An Examination of the Kubler-Ross Model

The Editors of Psycom

iStockPhoto.com/PeopleImages

Grief Model Background

Throughout life, we experience many instances of grief. Children may grieve a divorce, a wife may grieve the death of her husband, a teenager might grieve the ending of a relationship, or you might have grieved the loss of a pet.

In 1969, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross described five common stages of grief, popularly referred to as DABDA. They include:

Denial

Anger

Bargaining

Depression

Acceptance

A Swiss psychiatrist, Kübler-Ross first introduced her five stage grief model in her book On Death and Dying. Kübler-Ross’ model was based on her work with terminally ill patients and has been the subject of debate and criticism in the years since. Mainly, because people studying her model mistakenly believed this is the specific order in which people grieve and that all people go through all stages.

Kübler-Ross’ model was based on her work with terminally ill patients and has been the subject of debate and criticism in the years since. Mainly, because people studying her model mistakenly believed this is the specific order in which people grieve and that all people go through all stages.

Kübler-Ross now notes that these stages are not linear and some people may not experience any of them. Others might only undergo a few stages rather than all five. It is now more readily known that these five stages of grief are the most commonly observed in the grieving population.

So, What Are The Five Stages?

Denial

Denial is the stage that can initially help you survive the loss. You might think life makes no sense, has no meaning, and is too overwhelming. You start to deny the news and, in effect, go numb.

It's common in this stage to wonder how life will go on in this different state—you are in a state of shock because life as you once knew it has changed in an instant. If you were diagnosed with a deadly disease, you might believe the news is incorrect—a mistake must have occurred somewhere in the lab; they mixed up your blood work with someone else's. If you receive news of the death of a loved one, perhaps you cling to a false hope that they identified the wrong person. In the denial stage, you are not living in "actual reality," rather, you are living in a "preferable" reality.

If you were diagnosed with a deadly disease, you might believe the news is incorrect—a mistake must have occurred somewhere in the lab; they mixed up your blood work with someone else's. If you receive news of the death of a loved one, perhaps you cling to a false hope that they identified the wrong person. In the denial stage, you are not living in "actual reality," rather, you are living in a "preferable" reality.

Interestingly, it is denial and shock that help you cope and survive the grief event. Denial aids in pacing your feelings of grief. Instead of becoming completely overwhelmed with grief, we deny it, do not accept it, and stagger its full impact on us. Think of it as your body's natural defense mechanism, saying "Hey, there's only so much I can handle at once."

Once the denial and shock start to fade, the healing process begins. At this point, those feelings that you were once suppressing are coming to the surface.

Once you start to live in "actual" reality again, anger might start to set in. This is a common stage to think "Why me?" and "Life's not fair!" You might look to blame others for the cause of your grief and also may redirect your anger to close friends and family. You find it incomprehensible how something like this could happen to you. If you are strong in faith, you might start to question your belief in God: Where is God? Why didn't he protect me?

This is a common stage to think "Why me?" and "Life's not fair!" You might look to blame others for the cause of your grief and also may redirect your anger to close friends and family. You find it incomprehensible how something like this could happen to you. If you are strong in faith, you might start to question your belief in God: Where is God? Why didn't he protect me?

Researchers and mental health professionals agree that this anger is a necessary stage of grief. And encourage the anger. It's important to truly feel the anger. Even though it might seem like you are in an endless cycle of anger, it will dissipate—and the more you truly feel the anger, the more quickly it will dissipate, and the more quickly you will heal. It is not healthy to suppress your feelings of anger—it is a natural response—and perhaps, arguably, a necessary one.

(However, while suppressing anger is not advised, neither is letting it control you. It's important to seek help from a trained counselor or therapist if you are struggling with processing your anger. )

)

In everyday life, we are normally told to control our anger toward situations and toward others. When you experience a grief event, you might feel disconnected from reality, that you have no grounding anymore. Your life has shattered and there's nothing solid to hold onto. Think of anger as a strength to bind you to reality. You might feel deserted or abandoned during a grief event. That no one is there. You are alone in this world. The direction of anger toward something or somebody is what might bridge you back to reality and connect you to people again. It is a "thing." It's something to grasp onto, a natural step in healing.

Bargaining

When something bad happens, have you ever found yourself making a deal with God? "Please God, if you heal my husband, I will strive to be the best wife I can ever be, and never complain again." This is bargaining.

In a way, this stage is false hope. You might falsely make yourself believe that you can avoid the grief through this type of negotiation. If you change this, I'll change that. You are so desperate to get your life back to how it was before the grief event, you are willing to make a major life change in an attempt toward normality.

If you change this, I'll change that. You are so desperate to get your life back to how it was before the grief event, you are willing to make a major life change in an attempt toward normality.

Guilt is a common wingman of bargaining. This is when you can experience a seemingly endless string of "what ifs": What if I had left the house 5 minutes sooner? The accident would have never happened. What if I encouraged him to go to the doctor six months ago like I first thought? The cancer could have been found sooner and he could have been saved.

Depression

Depression is commonly associated with grief. It can be a reaction to the emptiness we feel when we are living in reality and realize the person or situation is gone or over. In this stage, you might withdraw from life, feel numb, live in a fog, and not want to get out of bed. The world might seem too much and too overwhelming for you to face. You might not want to be around others or feel like talking, and you might feel hopeless. You might even experience suicidal thoughts, thinking "What's the point of going on?"

You might even experience suicidal thoughts, thinking "What's the point of going on?"

Acceptance

The last stage of grief identified by Kübler-Ross is acceptance. Not in the sense that "it's OK my husband died" but rather, "my husband died, but I'm going to be OK."

In this stage, your emotions may begin to stabilize. You re-enter reality. You come to terms with the fact that the "new" reality is your partner is never coming back, or that you are going to succumb to your illness. It's not a "good" thing, but it's something you can move forward from.

It is definitely a time of adjustment and readjustment. There are good days, there are bad days, and then there are good days again. In this stage, it does not mean you'll never have another bad day, where you are uncontrollably sad. But, the good days tend to outnumber the bad days.

In this stage, you may lift from your fog, start to engage with friends again, and might even make new relationships as time goes on. You understand your loved one can never be replaced, but you move, grow, and evolve into your new reality.

You understand your loved one can never be replaced, but you move, grow, and evolve into your new reality.

Symptoms of Grief

Your grief symptoms may present themselves physically, socially, mentally, emotionally, or spiritually. Some of the most common symptoms of grief are presented below:

Crying

Headaches

Difficulty sleeping

Questioning the purpose of life

Questioning your spiritual beliefs (e.g., your belief in God)

Feelings of detachment

Isolation from friends and family

Abnormal behavior

Worry

Anxiety

Frustration

Guilt

Fatigue

Anger

Loss of appetite

Aches and pains

Stress

Treatment of Grief

Counseling, along with medication when needed, have been the most common methods of treating grief. Initially, your doctor may prescribe you medications to help you function more fully. These might include sedatives, antidepressants, or anti-anxiety medications to help you get through the day. In addition, your doctor might prescribe medication to help you sleep.

These might include sedatives, antidepressants, or anti-anxiety medications to help you get through the day. In addition, your doctor might prescribe medication to help you sleep.

However, the use of medication in grief treatment is controversial. Some providers believe it can mask feelings that arise as one goes through the grief process, and potentially delay healing. But you and your physican can determine a treatment plan that's best for you.

Counseling is a more solid approach to grief. Support groups, bereavement groups, or individual counseling can help you work through unresolved grief. This is a beneficial treatment alternative when you find the grief event is creating obstacles in your everyday life and you are having trouble functioning.

This support in no way "cures" you of your loss, rather, it provides you with coping strategies to help you deal with your grief in an effective way. The Kübler-Ross Model is a tried and true guideline, but there is no right or wrong way to work through your grief. Personal experiences may vary as people move among the stages of grief.

Personal experiences may vary as people move among the stages of grief.

If you or a loved one is having a hard time coping with a grief event, seek treatment from a health professional or mental health provider. Call a doctor right away if you experience thoughts of suicide, feelings of detachment for more than two weeks, you experience a sudden change in behavior, or believe you are suffering from depression.

Notes: This article was originally published March 22, 2016 and most recently updated June 7, 2022.

Five stages of grief. The Rise and Fall of Kübler-Ross

- Lucy Burns

- BBC

Image copyright Getty Images

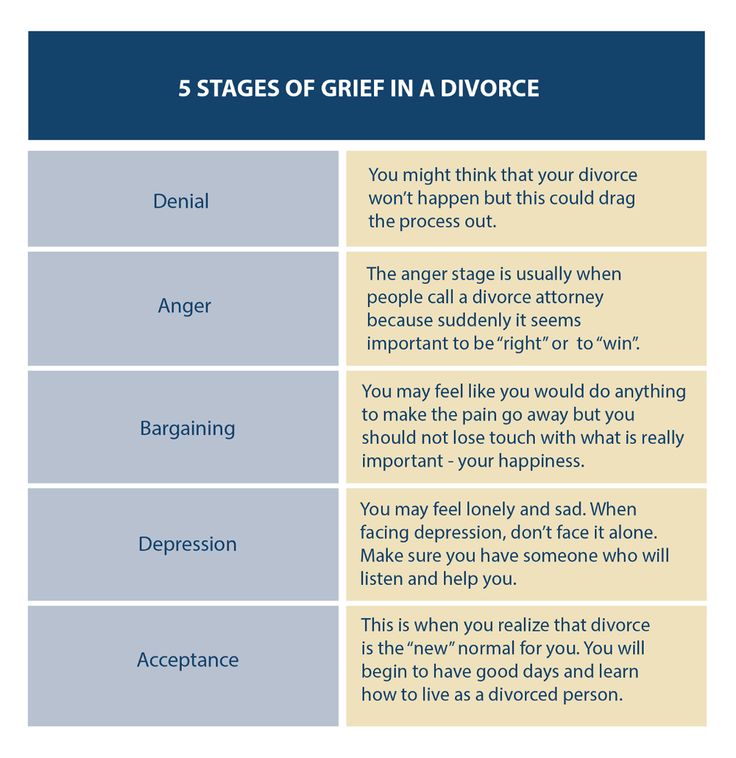

Denial. Anger. Finding a compromise. Despair. Adoption. Many people know the theory according to which grief, when receiving unbearable information for a person, goes through these steps. The scope of its application is wide: from hospices to boards of directors of companies.

The scope of its application is wide: from hospices to boards of directors of companies.

A recent interview with a psychologist in English on the Internet proves that the perception of the current quarantine is subject to the same rules. But do we all experience the same?

When Swiss psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross began working in American hospitals in 1958, she was struck by the lack of methods of psychological care for dying patients.

- A method that can predict your death

"Everything was impersonal, the attention was paid exclusively to the technical side of things," she told the BBC at 1983 year. “Terminally ill patients were left to their own devices, no one talked to them.”

She started a workshop with Colorado State University medical students based on her conversations with cancer patients about what they thought and felt.

Author photo, LIFE/Getty Images

Photo caption, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross talks to a woman with leukemia in Chicago, 1969. Seminar participants observe through a special mirror glass

Seminar participants observe through a special mirror glass

Despite the misunderstanding and resistance of a number of colleagues, soon there was nowhere for an apple to fall at the Kübler-Ross seminars.

In 1969 she published a book, On Death and Dying, in which she quoted typical statements from her patients and then moved on to discuss how to help doomed people pass from life as free of fear and pain as possible.

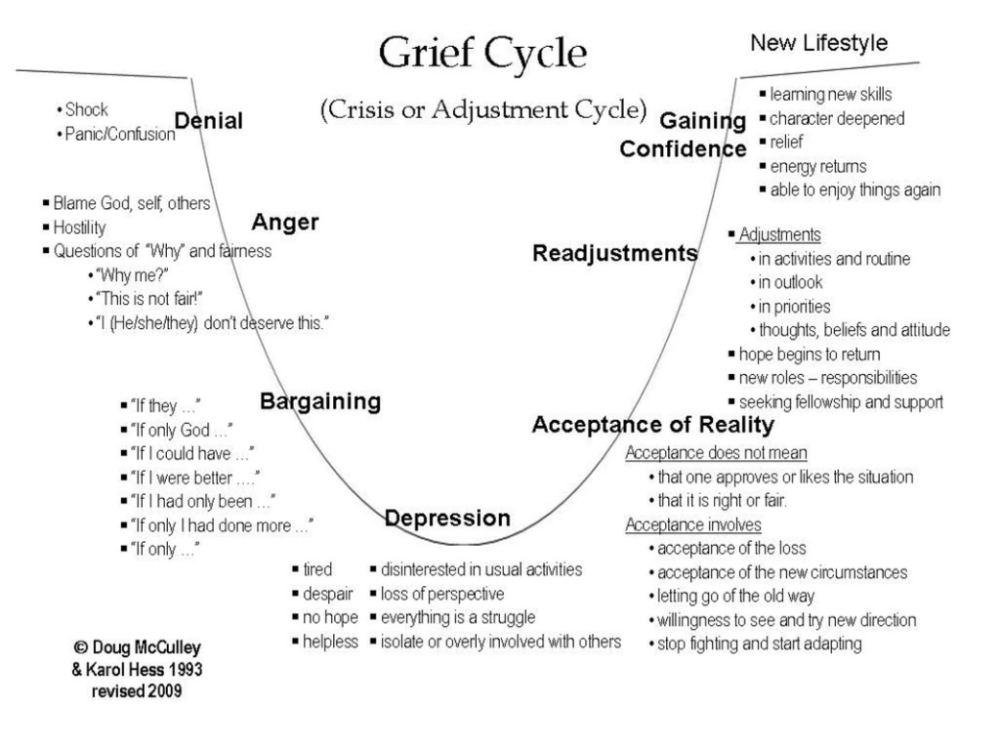

Kübler-Ross described in detail the five emotional states that a person goes through after being diagnosed with a terminal diagnosis:

- Denial: "No, that can't be true"

- Anger: "Why me? Why? It's not fair!!!"

- Bargaining: "There must be a way to save myself, or at least improve my situation! I'll think of something, I'll behave properly and do whatever is necessary!"

- Depression: "There is no way out, everything is indifferent"

- Acceptance: "Well, we must somehow live with this and prepare for the last journey"

difficult situation.

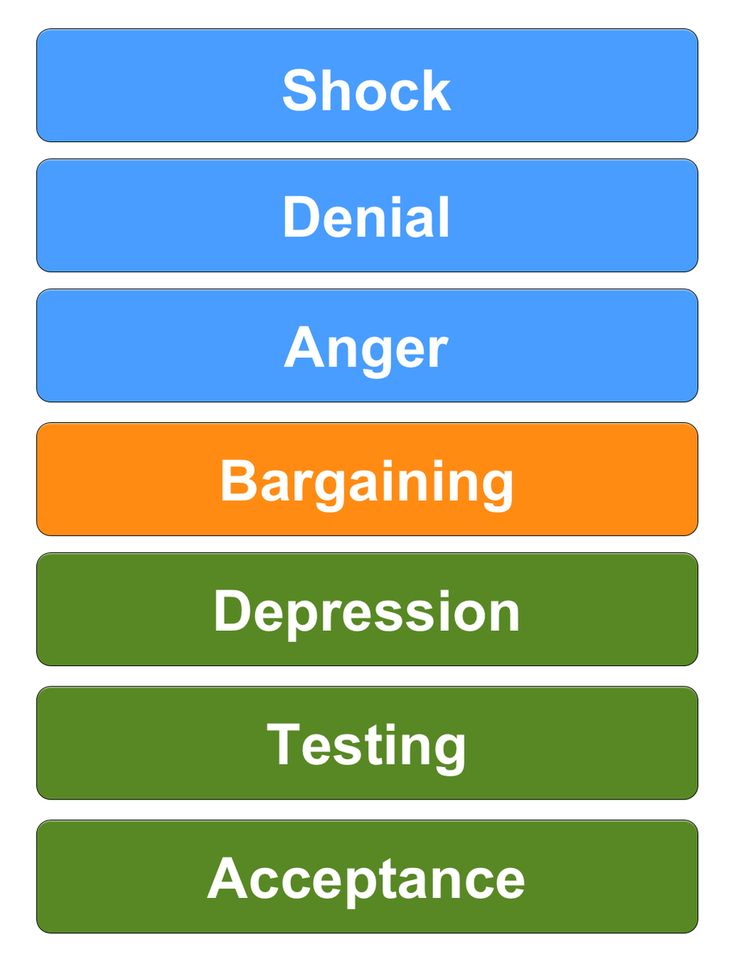

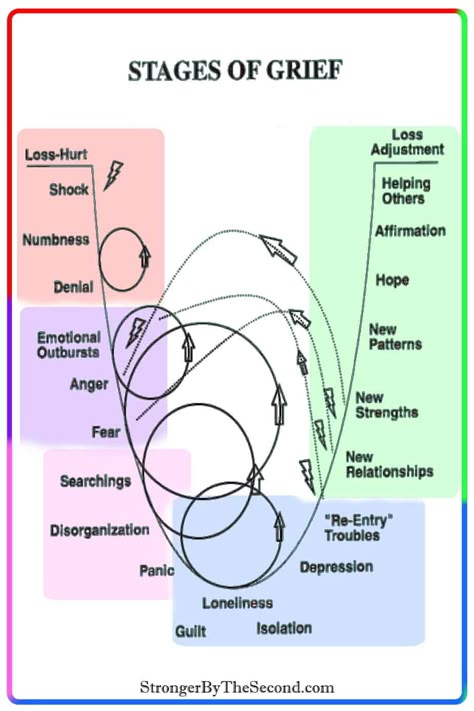

A separate chapter of the book is devoted to each of the stages. In addition to the five main ones, the author identified intermediate states - the first shock, preliminary grief, hope - from 10 to 13 types in total.

Image copyright Getty Images

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross died in 2004. Her son, Ken Ross, says she never insisted that every person must go through these five stages in sequence.

"It was a flexible framework, not a panacea for dealing with grief. If people wanted to use other theories and models, the mother did not object. She wanted to start a discussion of the topic first," he says.

- Last will: how did the photo of a dying American touch the world?

- "You hear everything, Fernando." How was the evening in honor of the terminally ill football player

The book "On Death and Dying" became a bestseller, and Elisabeth Kübler-Ross was soon inundated with letters from patients and doctors from all over the world.

"The phone kept ringing, and the postman started visiting us twice a day," recalls Ken Ross.

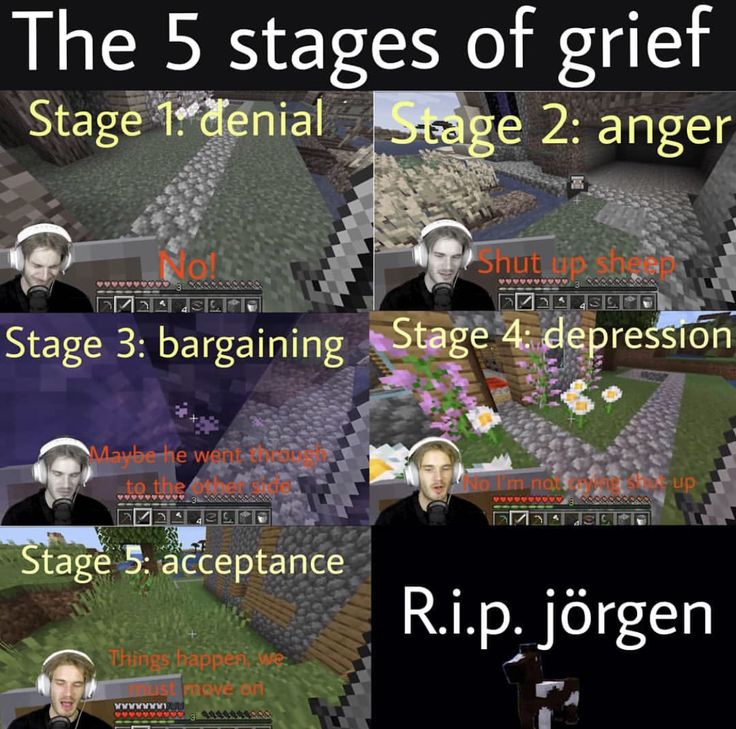

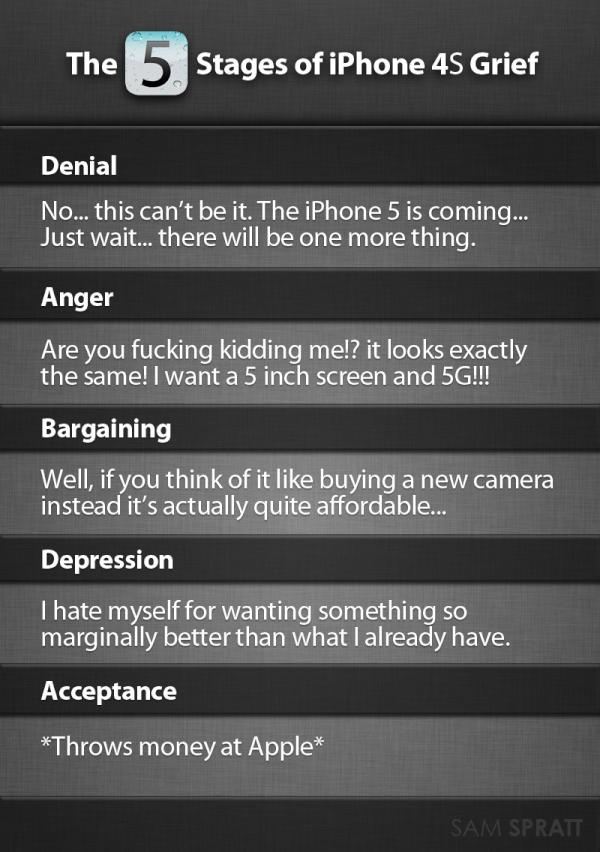

The notorious five steps took on a life of their own. Following the doctors, patients and their relatives learned about them. They were mentioned by the characters of the series "Star Trek" and "Sesame Street". They were parodied in cartoons, they gave food for creativity to the mass of musicians and artists and gave rise to many successful memes.

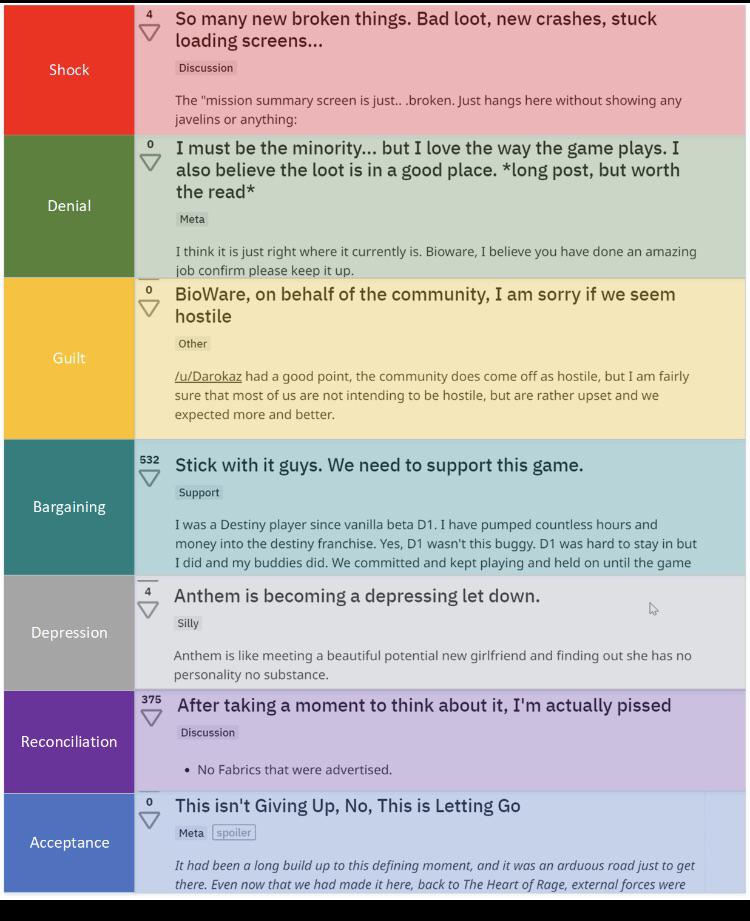

Literally thousands of scientific papers have been written that have applied the theory of the five steps to a wide variety of people and situations, from athletes suffering career-incompatible injuries to Apple fans' worries about the release of the 5th iPhone.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of History Podcast

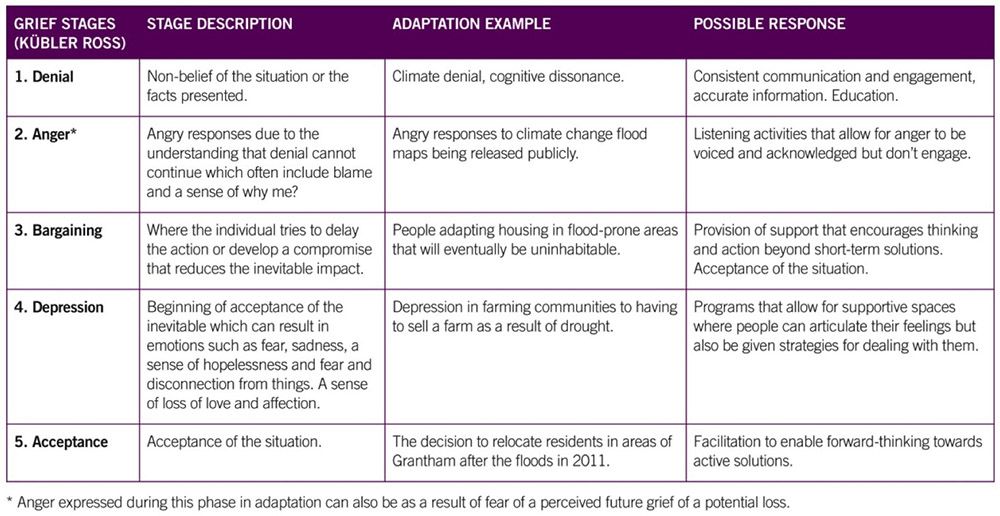

Kübler-Ross's legacy has found its way into corporate governance: Big companies from Boeing to IBM (including the BBC) have used her "change curve" to help employees at times of great business change.

And during the coronavirus pandemic, it applies, says psychologist David Kessler.

Kessler worked with Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and co-authored her latest book, Grief and How We Grieve. His interview with the Harvard Business Review at the start of the pandemic garnered a lot of attention online as people everywhere searched for solutions to their emotional problems.

"And here, first comes denial: the virus is not terrible, nothing will happen to me. Then anger: who dares to deprive me of my usual life and force me to stay at home?! Then an attempt to find a compromise: okay, if after two weeks of social distancing it gets better, then why not? Followed by sadness: no one knows when it will end. And, finally, acceptance: the world is now like this, you have to somehow live with it, "describes David Kessler.

And, finally, acceptance: the world is now like this, you have to somehow live with it, "describes David Kessler.

"As you can see, strength comes with acceptance. It gives you control: I can wash my hands, I can keep a safe distance, I can work from home," he says.

"It's a roadmap," says George Bonanno, professor of clinical psychology and head of the Loss, Trauma, and Emotion Laboratory at Columbia University. "When people are in pain, they want to know: how long will it last? What will happen to me? something to grab on to. And the five-step model gives them that opportunity."

"This scheme is seductive," notes Charles Corr, social psychologist and author of Death and Dying, Life and Being. "It offers an easy solution: sort everyone, and it takes no more than the fingers of one hand to label each one." .

George Bonanno sees this as a possible harm.

"People who don't fit exactly into these stages - and I've seen the majority of them - may decide they're grieving the wrong way, so to speak," he explains.

According to him, over the years he has seen many cases when people themselves inspired that they must certainly experience this and that, or they were convinced of this by friends and relatives, but they did not feel it and decided, that they need a doctor.

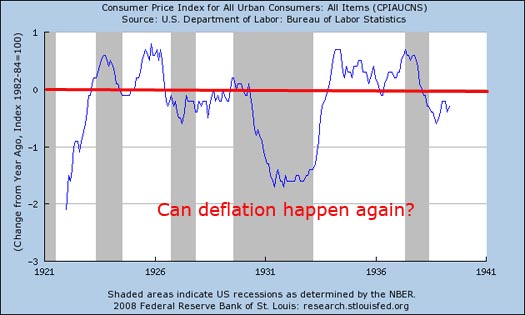

Experimental evidence of the existence of the five stages of grief is not enough. The longest and most extensive bereavement interview was conducted in 2007.

According to him, the most common state at any time is acceptance, only a few go through the stage of denial, and the second most common emotion is longing.

However, according to David Kessler, while scientists debate the nuances and terms, people who experience grief continue to find meaning in the Kübler-Ross scheme.

"I meet people who tell me, 'I don't know what's wrong with me. Now I'm angry, and a minute later I'm sad. I must be crazy.” And I say, “It has names. These are called the stages of grief. ” The person says, “Oh, so there is a special stage called 'anger'? It's about me!" And feels more normal."

” The person says, “Oh, so there is a special stage called 'anger'? It's about me!" And feels more normal."

Image copyright, Getty Images

"People need catchy statements. If Kübler-Ross hadn't called it stages and stated that there are exactly five of them, then she probably would have been closer to the truth. But then she would not have attracted to attention," says Charles Corr.

He believes that talking about the five stages distracts from the main scientific legacy of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross.

"She wanted to take on the topic of death and dying in the broadest sense: how to help terminally ill people come to terms with their diagnosis, how to help those who care for them, support these patients and cope with their own emotions, how to help everyone live a full life, realizing that we are not eternal,” says Charles Corr.

"The terminally ill can teach us everything: not only how to die, but also how to live," said Elisabeth Kübler-Ross at 1983 year.

During the 1970s and 1980s, she traveled the world, giving lectures and giving workshops to thousands of people. She was a passionate supporter of the hospice idea pioneered by British nurse Cecily Saunders.

Kübler-Ross has established hospices in many countries, the first in the Netherlands in 1999. Time magazine named her one of the 100 most important thinkers of the 20th century.

Professor Kübler-Ross' scientific reputation was shaken after she became fascinated with theories about the afterlife and began to experiment with mediums.

One of them, a certain Jay Barham, practiced non-standard religious-erotic therapy, in particular, he persuaded women to have sex, assuring that he was possessed by a person close to them from the afterlife. In 1979, because of this, a loud scandal arose.

In the late 1980s, she tried to set up a hospice for children with AIDS in rural Virginia, but faced strong local opposition to the idea.

In 1995, her house caught fire under suspicious circumstances. The next day Kübler-Ross had her first stroke.

She spent the last nine years of her life with her son in Arizona, moving around in a wheelchair.

In her last interview with the famous TV presenter Oprah Winfrey, she said that at the thought of her own death she feels only anger.

"The public wanted the famed expert on death and dying to be some kind of angelic personality and quickly get to the stage of acceptance," says Ken Ross. "But we all deal with grief and loss as best we can."

The theory of the five stages of grief is not widely taught in medical schools these days. It is more popular at corporate trainings under the name "Curve of Change".

Since then, there have been many theories about how to deal with your grief.

David Kessler, with the consent of Kübler-Ross's family, added a sixth stage to the five: the understanding that everything that is done makes sense.

"Understanding can come in a million different ways. Let's say I've become a better person after losing a loved one. Maybe my loved one passed away in a different way than it should have happened, and I can try to make the world a better place to this has not happened to others," says David Kessler.

Charles Corr recommends the "double process model". It was developed by Dutch researchers Margaret Stroebe and Nenk Schut and suggests that a person in grief is simultaneously experiencing a loss and preparing himself for new things and life challenges.

George Bonanno talks about four trajectories of grief. Some people have great stamina and do not fall into depression, or it is weakly expressed in them, others remain morally broken for many years, others recover relatively close, but then a second wave of grief rolls over them, and finally, the fourth becomes stronger from the loss.

Over time, one way or another, the vast majority of people get better.

But Professor Bonanno admits that his approach is less clear-cut than the five-stage theory.

"I can say to a person: 'Time heals.' But that doesn't sound so convincing," he says.

Grief is difficult to control and hard to endure. The thought that there is some kind of road map that suggests a way out is comforting, even if it is an illusion.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, in her latest book, Grief and How We Grieve, wrote that she did not expect to sort out the tangled human emotions.

Everyone experiences grief in their own way, even if some patterns can sometimes be deduced. Everyone goes their own way.

What is the Kubler-Ross Change Curve?

- Posted on Feb 17, 2022

- /Under Change Management

1 The Kübler-Ross Change Curve - A Real Life Example

2 Updated Kubler-Ross Change Curve

3 Kubler-Ross Curve Patterns and Examples

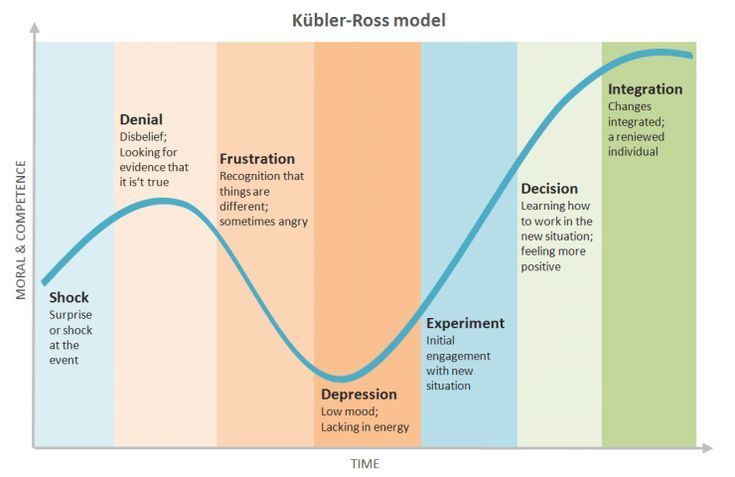

Kübler-Ross, an American psychologist, divided the psychological reactions and behavioral changes of terminally ill patients from the moment they are told of their illness to the time of death into five typical stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Edit this Kubler-Ross Change Curve Template

This curve pattern started not only with people's relationship to death, but later extended to life and business; she also developed the ADKAR organizational change model and the John Kotter eight-step change management model.

The five stages of the Kübler-Ross model are:

- " Shock and denial "No way, this can't be!" "Wasn't it always good?" – Shock or denial is the first and often the shortest step on the path to experiencing. The moment people hear bad news, defense mechanisms kick in and their brain refuses to accept reality and doesn't believe the news is true. Some people even miss the past for a long time and are unable to stop themselves.

- " Wrath " Why me? This is unfair!" "Who can I blame?" “When people finally accept reality and realize the seriousness of the problem, they get angry. This anger can take many forms; some people will blame themselves and place all the blame on themselves; others will take their anger out on others or on society as a whole.

In short, people at this stage will become irritable and cynical.

In short, people at this stage will become irritable and cynical. - " Bargaining " Just let me live to see my son graduate. Please (you), give me a few more years!” “I would do anything if she woke up. When angry, people try to find ways to prevent bad things from happening or find a compromise.

- " Depression " "Ugh, why all this? I'll die anyway." "I don't want to live, what's the point of living." In this stage of depression, people experience sadness, fear, regret, remorse, or other negative emotions. Perhaps they have completely given up on the fight and believe that the future is bleak. At this stage, people usually show signs of indifference to the outside world, reject others and lose all interest in life.

- " Acceptance of " "Good! Since I can't change anything anymore, I will prepare for the afterlife!" “When people discover that immersing themselves in grief does not help change the facts, they instead begin to accept the facts and begin to look to the future.

Kübler-Ross applies this model to all catastrophic personal losses (job, income, freedom), as well as the loss of family members and even divorce. She also assumes that the stages do not necessarily occur in a particular order and that the patient may not go through all of them, but she believes that the patient will go through at least two of them.

The Kübler-Ross curve - a real life example

One weekday you wake up with a jolt and realize that you are late. You hurriedly wash your face and get ready to drive to work, only to find that your car won't start. As a result, your mental activity will undergo the following changes.

1. Shock or denial

Faced with the fact that you are already late for work and your car won't start, obviously adding resentment to the trauma, shock and denial are probably the first reactions of mental activity. You begin to disbelieve how this misfortune can happen to you, and then you shoot the car again and again, trying to start it.

2. Anger

When you try dozens of times and find nothing helps, you become angry at your predicament.

3. Bargain

You begin to pray for a miracle, hoping that the car will understand your predicament and start. And promise yourself that after today you will take good care of your car so that nothing like this ever happens.

4. Depression.

All negative emotions immediately come to your mind and you suddenly feel helpless. You're worried that your boss will have problems with your being late and even fire you for it.

5. Acceptance

You calm down and know what to do next. You call an express car in a hurry and think about how to fix it in the car.

Updated Kubler-Ross Change Curve

Kubler-Ross suggests that a terminally ill patient goes through five stages of grief after becoming aware of their condition. She further suggested that this model could be applied to any life-changing situation.