Adhd with bipolar disorder

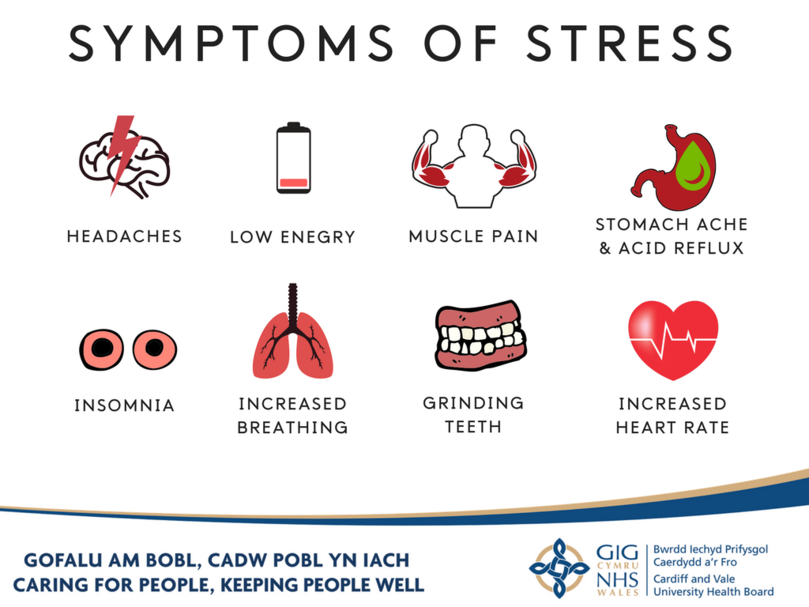

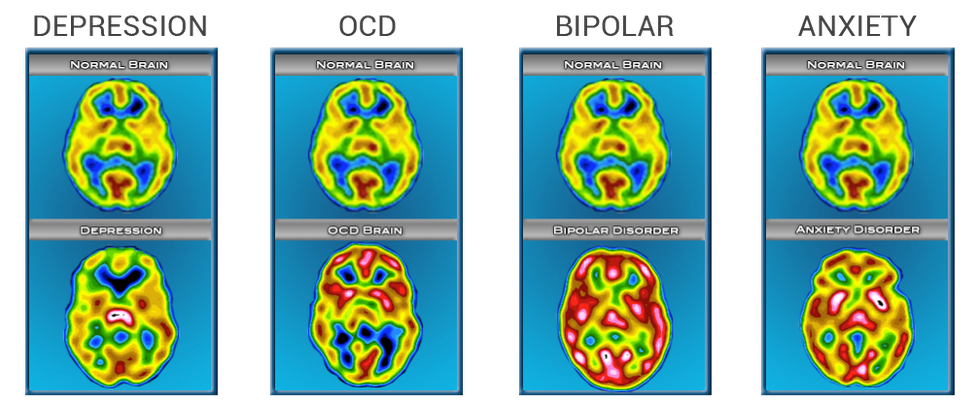

Symptoms of ADD and BPD

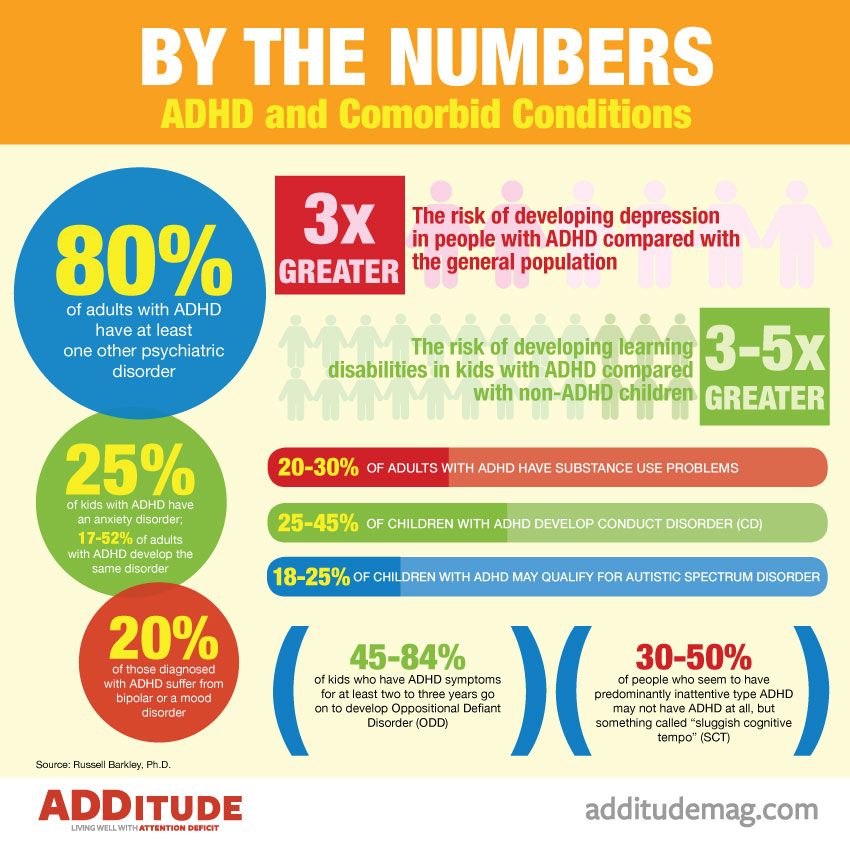

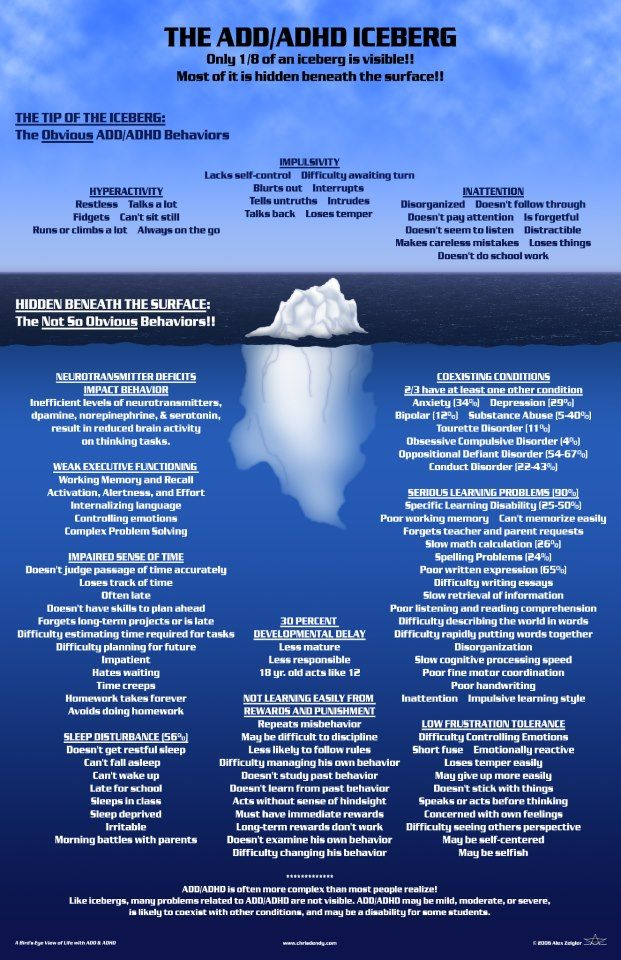

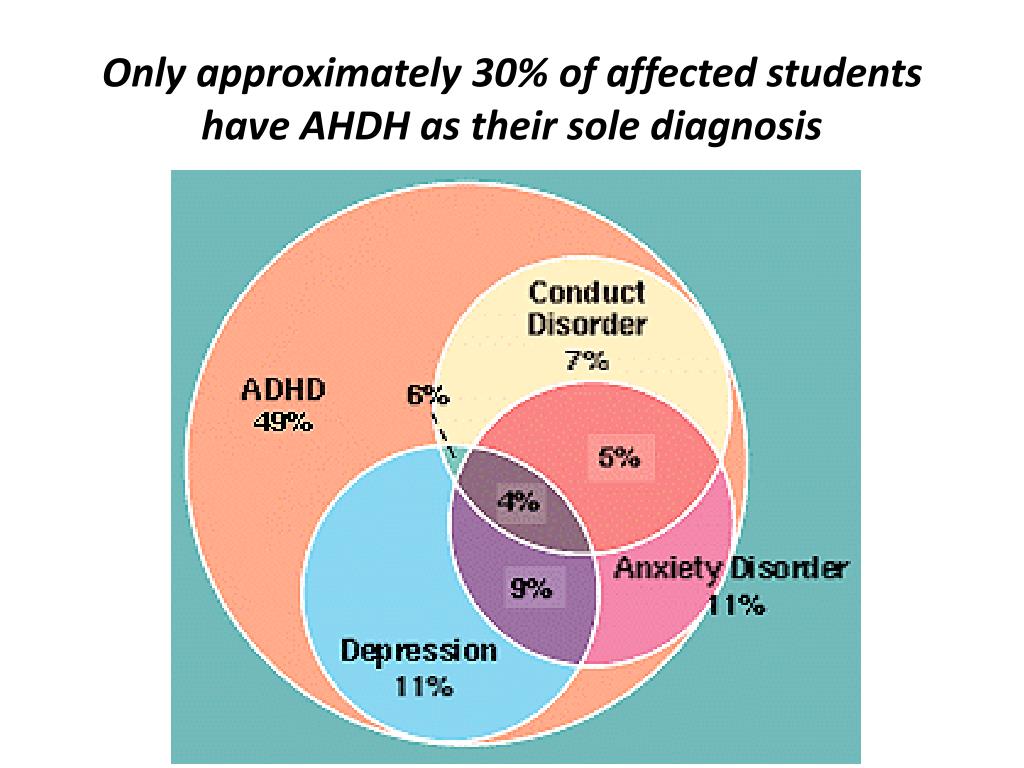

It can be difficult enough to obtain a diagnosis of attention deficit disorder (ADHD or ADD), but to complicate matters further, ADHD commonly co-exists with other mental and physical disorders. One review of adults with ADHD demonstrated that 42 percent had one other major psychiatric disorder. Therefore, the diagnostic question is not “Is it bipolar disorder or ADHD?” but rather “Is it both?”

Can You Have Both ADHD and Bipolar Disorder?

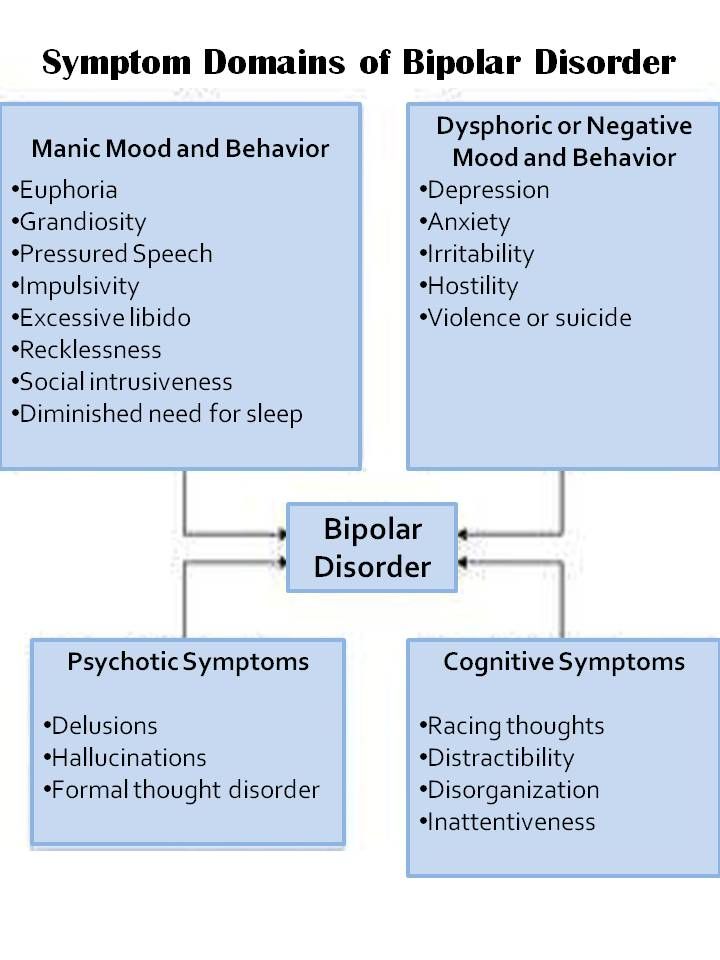

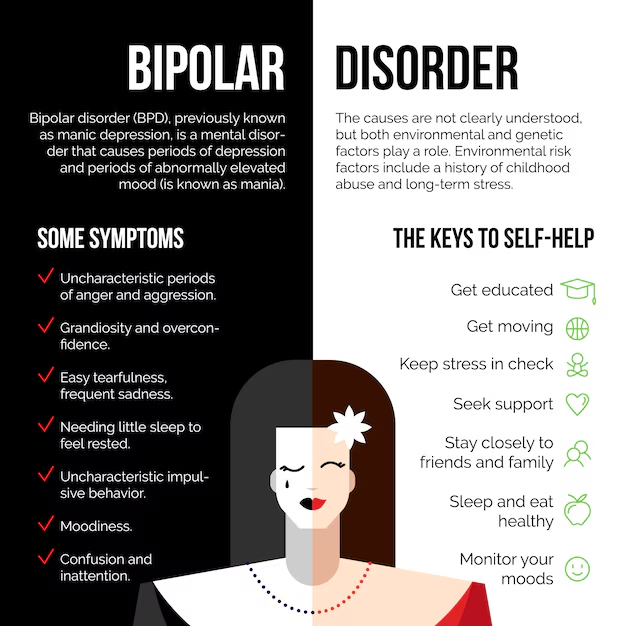

Perhaps the most difficult differential diagnosis to make is between Bipolar Mood Disorder (BMD) and ADHD, since they share many symptoms, including:

- Mood instability

- Bursts of energy

- Restlessness

- Talkativeness

- Impatience

It’s estimated that as many as 20 percent of those diagnosed with ADHD also suffer from a mood disorder on the bipolar spectrum — and correct diagnosis is critical in treating bipolar disorder and ADHD together.

ADHD or ADD

ADHD or ADD is characterized by significantly higher levels of inattention, distractibility, impulsivity, and/or physical restlessness than would be expected in a person of similar age and development. For a diagnosis of ADHD, such symptoms must be consistently present and impairing. ADHD is about 10 times more common than BMD in the general population.

[Free Download: Is It Bipolar Disorder or ADHD?]

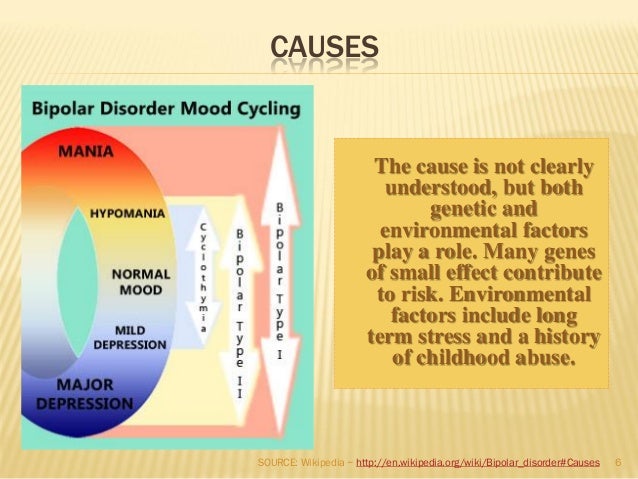

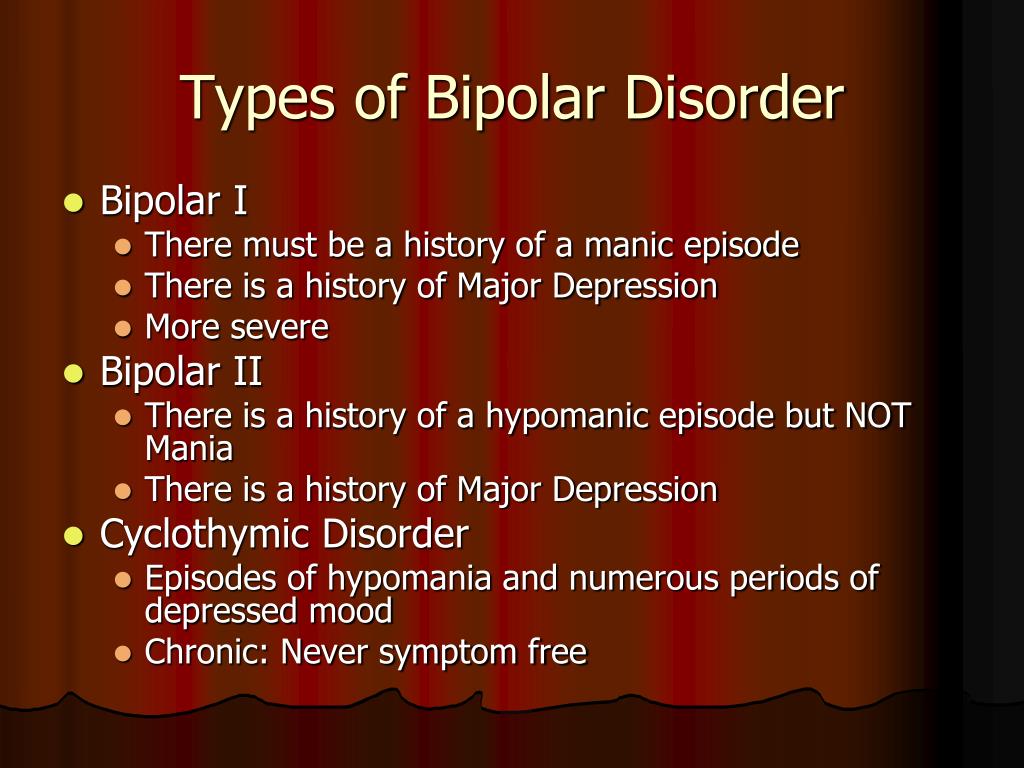

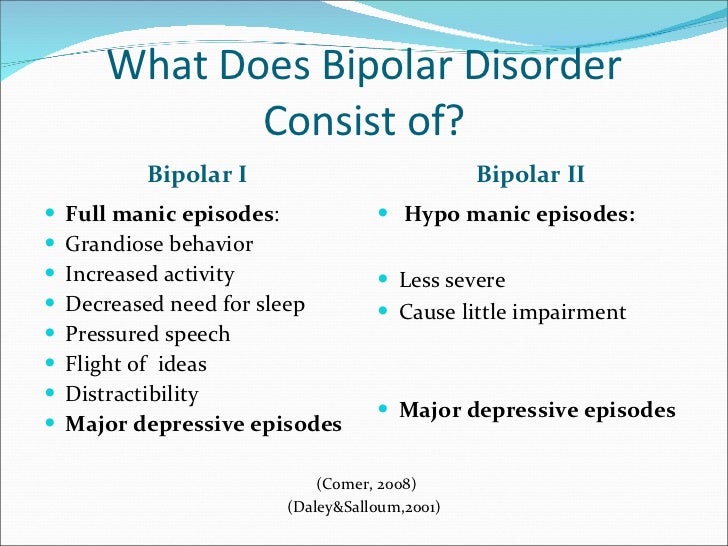

Bipolar Mood Disorder (BMD)

By diagnostic definition, mood disorders are “disorders of the level or intensity of mood in which the mood has taken on a life of its own, separate from the events of a person’s life and outside of [his] conscious will and control.” In people with BMD, intense feelings of happiness or sadness, high energy (called “mania”), or low energy (called “depression”) shift for no apparent reason over a period of days to weeks, and may persist for weeks or months. Commonly, there are periods of months to years during which the individual experiences no impairment.

Making a Diagnosis

Because of the many shared characteristics, there is a substantial risk of either a misdiagnosis or a missed diagnosis. Nonetheless, when determining if it is Bipolar Disorder or ADHD, use these six factors as a guide:

1. Age of onset: ADHD is a lifelong condition, with symptoms apparent (although not necessarily impairing) by age twelve. While we now recognize that children can develop BMD, this is still considered rare. The majority of people who develop BMD have their first episode of affective illness after age 18, with a mean age of 26 years at diagnosis.

Age of onset: ADHD is a lifelong condition, with symptoms apparent (although not necessarily impairing) by age twelve. While we now recognize that children can develop BMD, this is still considered rare. The majority of people who develop BMD have their first episode of affective illness after age 18, with a mean age of 26 years at diagnosis.

2. Consistency of impairment: ADHD is chronic and always present. BMD comes in episodes that alternate with more or less normal mood levels.

3. Mood triggers: People with ADHD are passionate, and have strong emotional reactions to events, or triggers, in their lives. Happy events result in intensely happy, excited moods. Unhappy events — especially the experience of being rejected, criticized, or teased — elicit intensely sad feelings. With BMD, mood shifts come and go without any connection to life events.

[Free Webinar: Emotions and ADHD: What Clinicians Need to Know for Accurate Diagnosis]

4. Rapidity of mood shift: Because ADHD mood shifts are almost always triggered by life events, the shifts feel instantaneous. They are normal moods in every way, except in their intensity. They’re often called “crashes” or “snaps,” because of the sudden onset. By contrast, the untriggered mood shifts of BMD take hours or days to move from one state to another.

Rapidity of mood shift: Because ADHD mood shifts are almost always triggered by life events, the shifts feel instantaneous. They are normal moods in every way, except in their intensity. They’re often called “crashes” or “snaps,” because of the sudden onset. By contrast, the untriggered mood shifts of BMD take hours or days to move from one state to another.

5. Duration of moods: Although responses to severe losses and rejections may last weeks, ADHD mood shifts are usually measured in hours. The mood shifts of BMD, by DSM-V definition, must be sustained for at least two weeks. For instance, to present “rapid-cycling” bipolar disorder, a person needs to experience only four shifts of mood, from high to low or low to high, in a 12-month period. Many people with ADHD experience that many mood shifts in a single day.

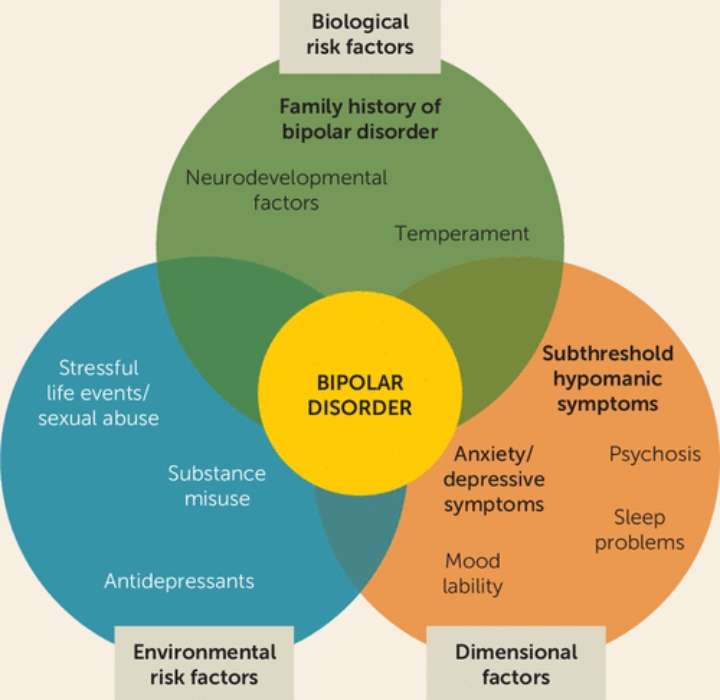

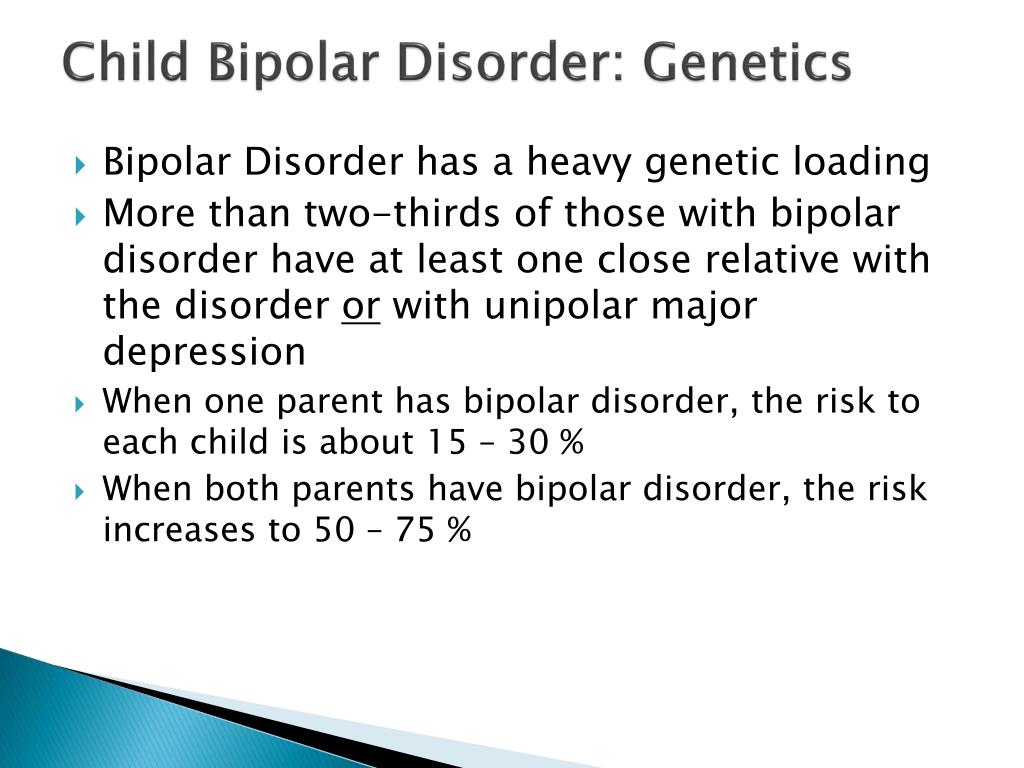

6. Family history: Both disorders run in families, but individuals with ADHD almost always have a family tree with multiple cases of ADHD. Those with BMD are likely to have fewer genetic connections.

Those with BMD are likely to have fewer genetic connections.

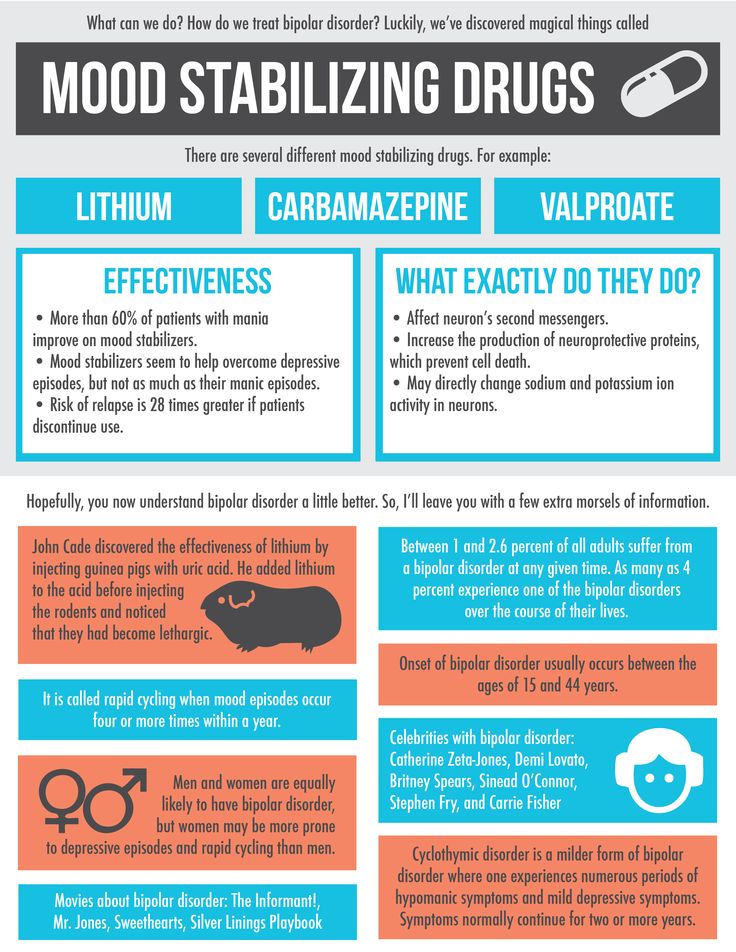

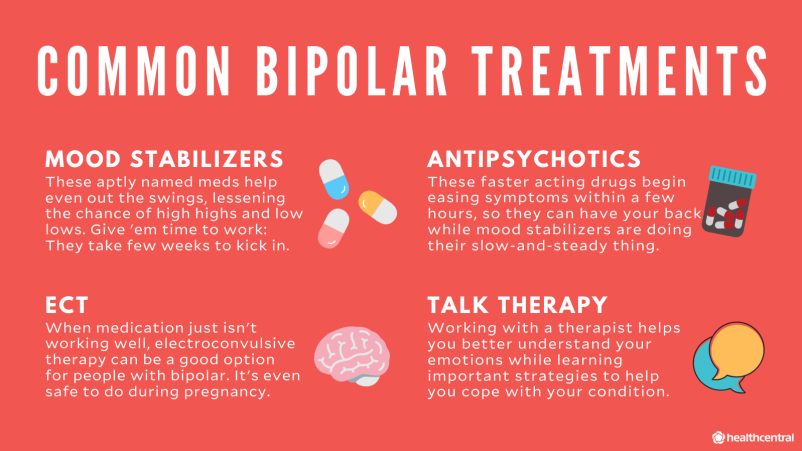

Treatment of Combined ADHD and BMD

Few articles have been published about the treatment of people who have ADHD and BMD. My clinical experience, having seen more than 100 patients with both disorders, shows that coexisting ADHD and BMD can be treated very well. It’s important to always diagnose and treat the BMD first, as ADHD treatment may precipitate mania or otherwise worsen BMD.

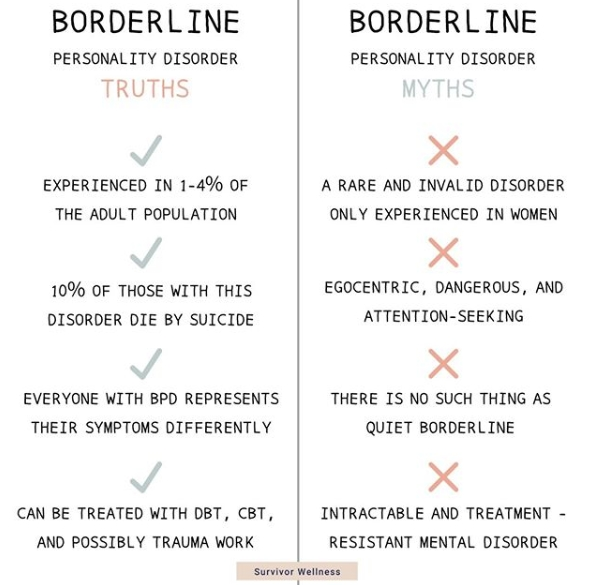

[10 Myths (and Truths) About Bipolar Disorder]

Outcomes for my patients treated for both ADHD and BMD have thus far been good. The majority have been able to return to work. Perhaps more importantly, they report that they feel more “normal” in their moods and in their ability to fulfill their roles as spouses, parents, and employees. It is impossible to determine whether these significantly improved outcomes are due to enhanced mood stability, or whether treatment of ADHD makes for better medication compliance. The key lies in the recognition that both diagnoses are present and that the disorders will respond to independent, but coordinated, treatment.

Previous Article Next Article

Bipolar and ADHD...Together? An Expert Explains The Signs

Richard, 31, had been diagnosed with ADHD at 12, but he felt that the diagnosis did not explain some of his disabling symptoms. He suffered from terrible depressive episodes and had weeks when he was consistently restless, agitated, and unable to sleep.

His therapist said that people with ADHD often had mood fluctuations. Richard did not find the ADHD stimulants that his doctor prescribed to be helpful, and he began to feel worthless and socially isolated.

Jack, 17, was diagnosed with ADHD and Oppositional Defiant Disorder at age four. His mother said that on some days “he would wake up on the destructive side of the bed.” Instead of tantrums, she endured rages over things that, on other days, didn’t anger him. He attempted suicide at 16, after reporting that he couldn’t live in a world that was “too loud” for him.

Richard and Jack had ADHD, but they also suffered from Bipolar Disorder (BD), characterized by episodes of depression and of elevated mood states, referred to as hypomanic or manic episodes.

Bipolar Facts

Approximately 10 million people in the United States have BD. Bipolar disorder often co-occurs with ADHD in adults, with comorbidity rates estimated between 5.1 and 47.1 percent1. Recent research, however, suggests that about 1 in 13 patients with ADHD has comorbid BD, and up to 1 in 6 patients with BD has comorbid ADHD2. The tragedy is that, when the disorders co-occur, the diagnoses are often missed. It can take up to 17 years for patients to receive a diagnosis of BD. As with any co-occurring disorder, it is important to receive the right diagnosis as early as possible to treat the condition effectively.

Tristan had struggled with BD for 12 years. “I had been told I had something called ‘Limbic and Ring of Fire ADHD,’ which could be treated with supplements. After the treatment, I still couldn’t get my life together, so I figured I was a loser.” After a bout of alcoholism and two suicide attempts, he was assessed by a specialist who understood both conditions and was diagnosed with ADHD and BD. Tristan is now happier than ever before.

After the treatment, I still couldn’t get my life together, so I figured I was a loser.” After a bout of alcoholism and two suicide attempts, he was assessed by a specialist who understood both conditions and was diagnosed with ADHD and BD. Tristan is now happier than ever before.

It is understandable that doctors confuse bipolar symptoms for those of ADHD. Both conditions involve impulsivity, irritability, hyperactivity, emotional dysregulation, sleep problems, a racing brain, and problems with maintaining attention. But on deeper examination, there are ways to distinguish one condition from the other.

[ADHD Directory: Find a Specialist or Clinic Near You]

Depressive Episodes: One Side of BD

1. Persistent, sad, or irritable mood. Francis, 14, would wake up feeling “completely gray. I knew that meant the beginning of what I call one of my ‘doomdays.’ I never knew why I felt that way, and it lasted for two or three days sometimes.” This is a classic depressive episode commonly seen with BD.

Lilia, diagnosed with ADHD, could always pinpoint the reason for her moods — a break-up, a poor grade on a test, or a fight with a friend. She saw that her depressive moods were caused by external events. In BD, the mood shifts, which can be rapid and intense, seem to come from the inside, regardless of what is happening externally.

2. Loss of interest in previously enjoyable activities. One of the first signs of depression for Indigo, 17, was not wanting to play the guitar. “With ADHD, I get bored quickly and lose interest in something. But with BD depression, I lose interest in everything.”

3. Significant changes in appetite, body weight, and sleep patterns. The key here is context. Those with ADHD have weight fluctuations or periods when they are sleeping too much or too little. These are often caused by the activities people participate in. When Mario is engaged in periods of hyperfocus (due to procrastination), he works 10-12 hours straight, and feels he cannot stop to eat for fear that he will lose momentum. Kate, 19, who had BD, lost her appetite and couldn’t sleep for six or seven days at a time.

Kate, 19, who had BD, lost her appetite and couldn’t sleep for six or seven days at a time.

4. Low energy and concentration. Many people with ADHD become fatigued, particularly in situations when their executive functions are taxed. Trouble in focusing and paying attention comes with situations that are boring and not stimulating to them. Vincenzo, 28, who has both ADHD and BD, has learned the signs of an oncoming depressive episode. “It is as if I am walking in molasses through life, even in situations where the day before I was dancing. My ability to focus is completely shot in a way that makes ADHD look like a cakewalk.”

5. Feelings of worthlessness, inappropriate guilt, and recurrent thoughts of death and suicide. One of the major distinctions between ADHD and a depressive episode is feeling worthless, which can lead to suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Fifty percent of people with BD attempt suicide, and 20 percent eventually kill themselves.

Manic Episodes: The Other Side of BD

1. Severe changes in mood. The hallmark of a manic or hypomanic (a less intense but still potentially disabling) episode is a severe shift in mood, in which someone becomes extremely irritable or inappropriately elated without any external reason. These mood states last for hours (as do mixed manic episodes), days, or weeks. With ADHD, irritability is often the result of boredom, sleep deprivation, a stressful situation, or heavy demands on executive functioning. A person having a manic episode feels irritable, regardless of what is going on.

2. Inflated self-esteem and grandiosity. When patients are in the throes of a manic episode, their sense of themselves can become grandiose or narcissistic. Sometimes it is subtle (“I am a better driver than anyone I know”), and other times it can be detached from reality (“I have an amazing ability to do everything”).

3. Increased, revved-up energy. Kathleen, 30, described her manic episodes as “a flurry of uncontrolled energy.” With ADHD, people can feel excited and energetic; manic energy, however, feels scary, uncontrolled, and uncontained.

Kathleen, 30, described her manic episodes as “a flurry of uncontrolled energy.” With ADHD, people can feel excited and energetic; manic energy, however, feels scary, uncontrolled, and uncontained.

4. Impulsive or self-destructive behaviors. Hypersexuality, substance abuse, reckless driving, and conflict with others are common in mania. With ADHD, impulsive acts are driven by something someone wants to do. With BD, people having a manic episode feel driven to do acts that, when not manic, they would have no desire to do.

5. Psychosis. Having thoughts that are detached from reality is not a symptom of ADHD, but that is a symptom of a severe depression or mania. Jeff, 36, believed he was Jesus Christ when manic, while Kelly, 14, heard “angels talking.”

Although ADHD and BD are characterized by emotional dysregulation, the mood experiences associated with BD tend to be longer, more chronic in nature, more cyclical, and triggered more easily than in ADHD.

BD runs in families, so someone is at increased risk if he or she has a family member who has been diagnosed with it. Many times BD goes undiagnosed, so it is a good idea for clinicians to ask if anyone in the family has attempted or committed suicide, has had electroconvulsive shock therapy, or has been involuntarily committed to a psychiatric hospital.

BD and ADHD: A Bad Combination

It is essential that a clinician evaluate a patient for ADHD when BD is part of the picture. The debilitating and tormenting nature of this illness cannot be overestimated, especially in someone who also has ADHD. Since the comorbidity rates are high, any time someone is diagnosed with one, the presence of the other should always be looked for.

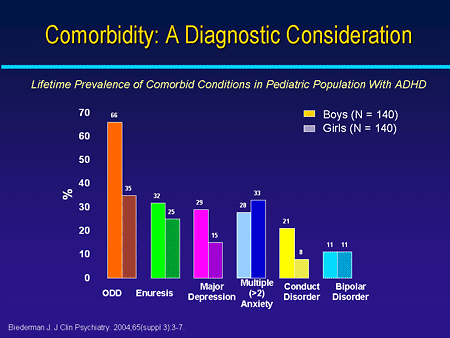

Studies of people who have both ADHD and BD demonstrate that they have more severe ADHD symptoms, have an earlier age of onset for BD, and have more psychiatric disorders than those with ADHD alone. When compared to patients with BD only, patients with both ADHD and BD tend to be male, and most of them have been diagnosed with conduct disorder or ODD.

Keep in mind that these studies involved many people who were not identified early and suffered for years without the proper diagnoses. Early diagnosis and treatment — which is different for each disorder — are essential in changing the prognosis. With proper medication, therapy, and life management, a patient can live a full, healthy life.

View Article Sources

1 Katzman, M. A., Bilkey, T. S., Chokka, P. R., Fallu, A., & Klassen, L. J. (2017). Adult ADHD and comorbid disorders: clinical implications of a dimensional approach. BMC psychiatry, 17(1), 302. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1463-3

2Schiweck C, Arteaga-Henriquez G, Aichholzer M, et al. Comorbidity of ADHD and adult bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2021;124:100-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.017

Previous Article Next Article

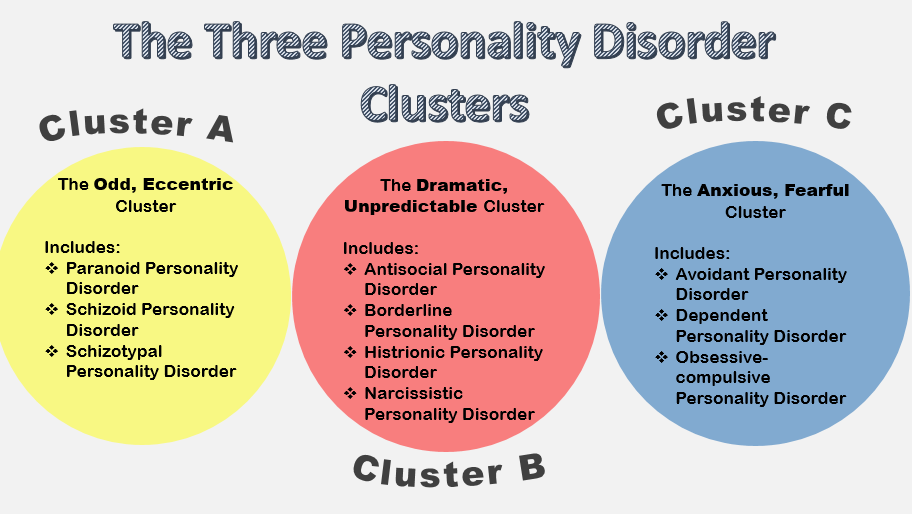

Comorbidity in ADHD | Neuroapex

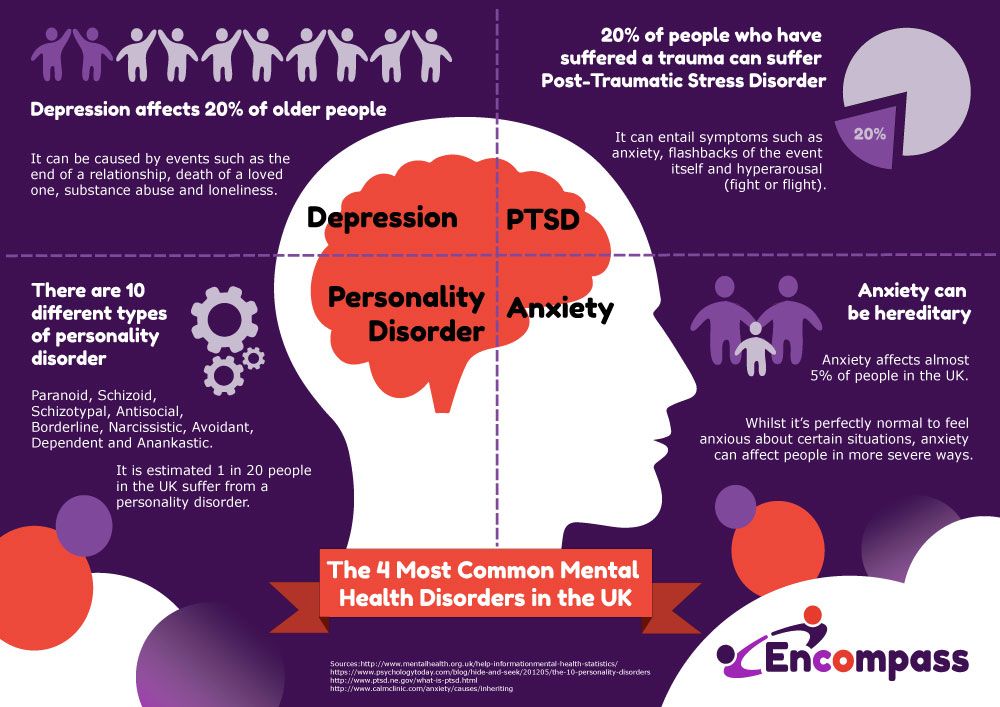

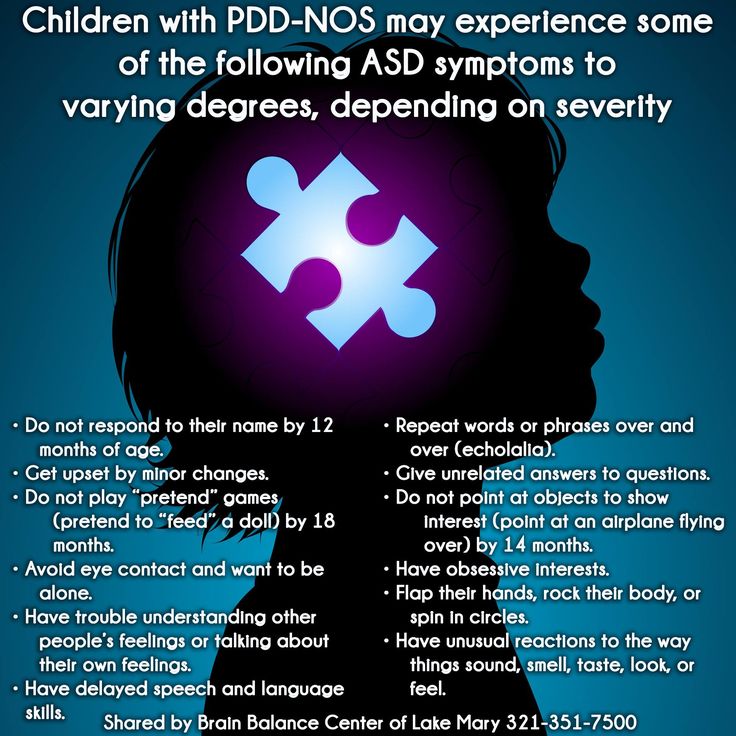

The problem of correct diagnosis and treatment of ADHD is even more complicated by the fact that a large proportion (from 40% to 70% according to different authors) of hyperactive children with ADHD have concomitant or comorbid disorders that are not formally associated with the syndrome and more often exist in the form of independent forms of mental disorders, however, in some cases, they may be due to pathogenetic mechanisms common with ADHD. Among the accompanying ADHD disorders most often appear specific learning disorders, the so-called. oppositional behavioral disorder, the so-called. conduct disorder, Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, anxiety disorder, bipolar (depressive) disorder, and paroxysmal disorder (epilepsy or epileptiform syndrome).

Among the accompanying ADHD disorders most often appear specific learning disorders, the so-called. oppositional behavioral disorder, the so-called. conduct disorder, Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, anxiety disorder, bipolar (depressive) disorder, and paroxysmal disorder (epilepsy or epileptiform syndrome).

Specific learning disorders Many hyperactive children with ADHD, approximately 20-30 percent, have specific learning disabilities. At preschool age, these problems are incomprehension of certain sounds or words, and/or difficulty in expressing one's opinions in words. At school age, problems with reading, spelling, writing and arithmetic may appear. A common type of reading disorder is dyslexia . Nearly 8 percent of elementary school children have reading problems. There are also such specific forms of learning disorders as dysgraphia, dyscalculia, etc.

Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. A very small percentage of people with ADHD have a neurological disease called Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. People with this syndrome suffer from various nervous tics and repetitive actions, including blinking, facial tics, or grimacing. Others may repeatedly cough, snort, sniff, or yell swear words. This behavior can be controlled with medication. Although very few children have Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, many children who do have it are associated with ADHD. In such cases, drugs are needed to treat both conditions.

People with this syndrome suffer from various nervous tics and repetitive actions, including blinking, facial tics, or grimacing. Others may repeatedly cough, snort, sniff, or yell swear words. This behavior can be controlled with medication. Although very few children have Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, many children who do have it are associated with ADHD. In such cases, drugs are needed to treat both conditions.

Oppositional defiant disorder . One-third to one-half of all hyperactive children with ADHD—mostly boys—have another disorder known as oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). Such children are usually impudent, stubborn, intractable, they are characterized by outbursts of anger or aggression. They argue with adults and refuse to obey.

Conductive disorder. Approximately 20-40% of hyperactive children with ADHD develop conduct disorder (CD) over time, a more severe antisocial behavior compared to a less mild form of oppositional behavior. These children often lie or steal, fight or bully others, and are more likely to have problems at school or with the police. They violate the rights of others, are aggressive towards other people or animals, destroy private property, break into people's homes, commit theft, carry or use weapons, or engage in vandalism. These children or teenagers are more likely to try drugs and then become addicted.

They violate the rights of others, are aggressive towards other people or animals, destroy private property, break into people's homes, commit theft, carry or use weapons, or engage in vandalism. These children or teenagers are more likely to try drugs and then become addicted.

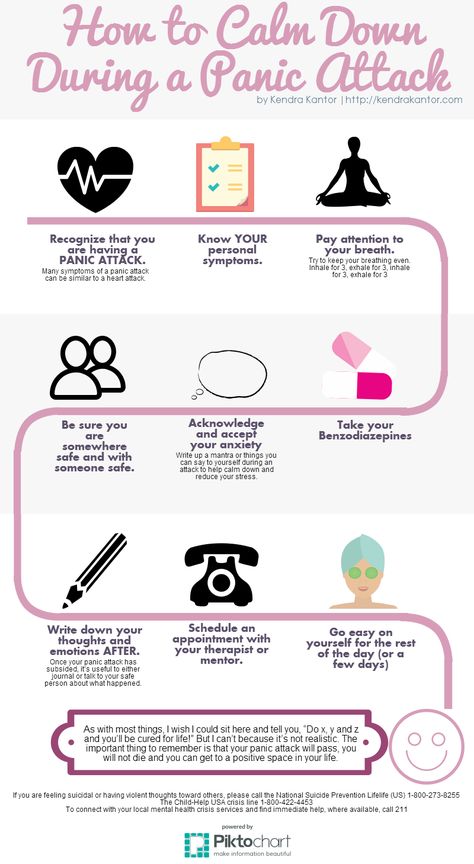

Anxiety and depression . Some hyperactive children with ADHD often have comorbid anxiety or depression. In this case, the following pattern appears quite clearly - if anxiety or depression is diagnosed and treated, the child can better control the problems associated with ADHD. Conversely, effective ADHD treatment may also have a positive effect on anxiety, as the child is able to perform better in school.

Bipolar disorder. There are no definitive statistics on how many hyperactive children with ADHD have bipolar disorder. In childhood, it is very difficult to distinguish between ADHD and bipolar disorder. In its classic form, bipolar disorder is characterized by alternating periods of good and bad mood. But it seems that children with bipolar disorder are more likely to have chronic mood dysregulation combined with euphoria, depression, and irritability. In addition, there are several symptoms that are common to both ADHD and bipolar disorder, such as increased activity and reduced need for sleep. The symptoms that differentiate ADHD from bipolar disorder are persistent high spirits with elements of demonstrativeness in a child with bipolar disorder. It should also be noted that in the case of comorbidity of ADHD with bipolar disorder, diagnosis and treatment require the participation of a qualified psychiatrist.

But it seems that children with bipolar disorder are more likely to have chronic mood dysregulation combined with euphoria, depression, and irritability. In addition, there are several symptoms that are common to both ADHD and bipolar disorder, such as increased activity and reduced need for sleep. The symptoms that differentiate ADHD from bipolar disorder are persistent high spirits with elements of demonstrativeness in a child with bipolar disorder. It should also be noted that in the case of comorbidity of ADHD with bipolar disorder, diagnosis and treatment require the participation of a qualified psychiatrist.

Paroxysmal disorder. In 5-10% of cases of hyperactive children with ADHD, predominantly hyperactive and/or impulsive type, a paroxysmal disorder is detected in the form of various kinds of paroxysms or seizures, both with loss of consciousness and without it. In some cases, paroxysmal manifestations appear exclusively at a non-clinical level and are detected using an electroencephalographic examination of the brain.

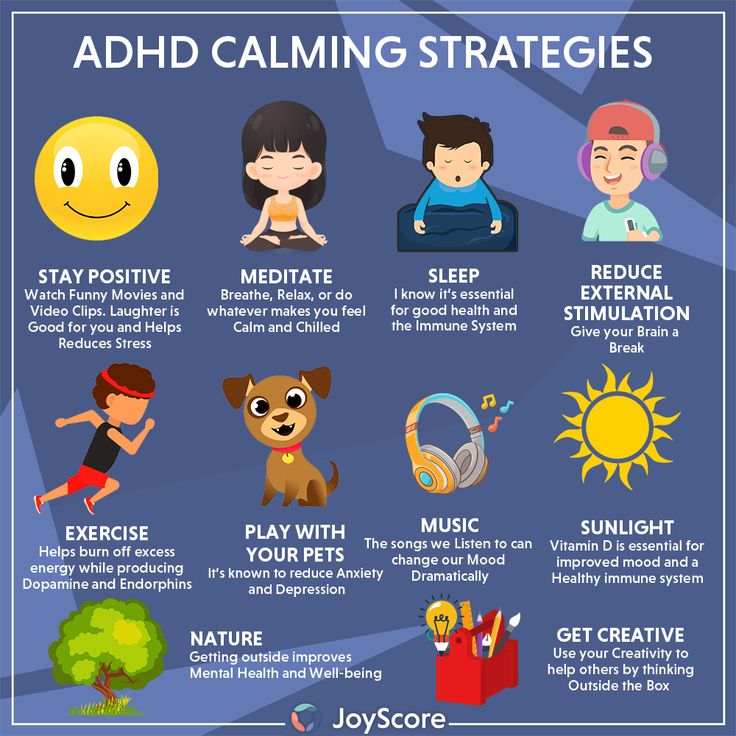

How to deal with Attention Deficit Disorder?

Bipolar disorder often co-occurs with other mental conditions. One of the most common options is a combination of bipolar disorder and ADHD, that is, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

In this case, in order to feel better, it is necessary not only to take drugs for bipolar disorder, but also to control the symptoms of ADHD. Unfortunately, in Russia, attention deficit disorder in adults is not recognized as a disease and no special medicines are prescribed for it. But there are many ways to improve your condition without drugs. All of them are collected in the bestseller Why I Get Distracted. The author of the book, Edward Hallowell, is one of the most famous ADHD researchers.

Here are some helpful tips from the author:

1. Make sure the diagnosis is correct.

It is essential to know that you are working with a professional who truly understands ADD and has ruled out related and related conditions such as anxiety, agitated depression, hyperthyroidism, manic depressive illness, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

2. Educate yourself.

Perhaps the most powerful cure for ADD is understanding the disease. Read books. Communicate with specialists. Talk to other adults with ADD. They can be found through support groups, local and national disease organizations. In this way, you can develop your own treatment that is suitable for your variant of the syndrome.

3. Select a trainer.

It is useful to have a coach or person nearby who will look after you, and always with humor. The coach will help you get ready, stay on target, inspire you and remind you to get back to work. Whether it's a friend, a colleague, or a therapist (it's okay to coach your spouse, but it's risky), the coach needs to push you to get things done, motivate you, control you, and generally take care of you. A coach can be an incredible help in treating ADD.

4. Seek encouragement.

Adults with ADD are in dire need of encouragement. This is partly due to the numerous self-doubts that have accumulated over the years, but not only this. Such people fade more than others without encouragement and flourish if they receive it. For the sake of their neighbor, they often work in a way that they would not work for themselves. It's not bad: they just are. This must be recognized and used.

This is partly due to the numerous self-doubts that have accumulated over the years, but not only this. Such people fade more than others without encouragement and flourish if they receive it. For the sake of their neighbor, they often work in a way that they would not work for themselves. It's not bad: they just are. This must be recognized and used.

5. Realize that you cannot call ADD.

This is not a conflict with the mother, not a subconscious fear of success, not a passive-aggressive personality, etc. Patients with ADD, of course, are not immune from all these conditions, but it is important to separate the syndrome from other problems, because it needs to be treated in a completely different way .

6. Educate and involve others.

It is important not only to understand the diagnosis yourself. It is equally important that others understand you - friends, relatives, teachers, colleagues. When they know what the problem is, it will be easier for them to understand you and help you achieve your goals.

7. Stop blaming yourself for looking for strong incentives.

Realize that you are drawn to intense stimulation anyway, so you need to choose stimuli wisely, and not constantly beat yourself up for "bad" ones.

8. Get feedback from people you trust.

Adults (and children too) with Attention Deficit Disorder are extremely bad at observing themselves, and from the outside it may seem that they are denying the obvious.

9. Consider joining or organizing a support group.

A lot of useful information about ADD is not yet described in books: we are talking about the invaluable experience of people with this syndrome. In a group, such information can be voiced. Another plus will be the support that the patient so badly lacks.

10. Try to get rid of the negative attitude.

It could have infected you for years before you knew that attention deficit disorder was to blame for your condition. This is where a good therapist can help.

This is where a good therapist can help.

11. Don't feel constrained by traditional careers and habitual adaptations.

Allow yourself to be yourself. Stop trying to be the person you are supposed to be—like a model student or an organized leader—and allow yourself to be who you really are.

12. Remember that you have a neurological disease.

It is inherited. It arose for biological reasons. This is how your brain works. This is not your personal flaw, not a moral flaw and not some kind of neurosis. It's not a weakness or an inability to grow up. For treatment, one does not need to strain the will, endure pain, punishments and sacrifices. Always remember this. No matter how hard many people with ADD try, it can be very difficult for them to come to terms with the fact that the origins of this syndrome are rooted in biology, and not in weakness of character.

13. Try to help others with ADD.

By helping, you will learn a lot about this disease and feel better.

14.Create the outer structure.

Structure is the basis of non-pharmacological treatment of ADD in children, but it is equally useful for adults. It acts like the walls of the track to keep the bobsleigh from flying out. Actively use lists, notes, color coding, rituals, reminders, folders. Apply the planning described above.

15. Brighten up your life.

Try to make the environment lively, but don't overdo it. If your organization system is stimulating rather than boring (think about it!), you are more likely to use it. For example, tidy up with color coding. This is worth emphasizing. Keep in mind that many ADD patients are visually oriented, so try to remember things by their color: folders, memos, texts, schedules, etc. Almost everything in black and white can be made more memorable, eye-catching if you add colors.

16. In paper work, use the principle of "taken - bring to the end."

Having received a document, a note, some written materials, try to deal with them immediately: immediately, on the spot, answer, throw it away or send it on. No need to put off anything indefinitely, in a bunch of upcoming things. For people with ADD, this might as well be called a bunch of things that will remain unfinished. They will become little nightmares on the table or in the room, they will slowly feed the guilt, anxiety and resentment, and they will also take up a lot of space. Get into the habit of doing paperwork immediately. Make the agonizing decision to throw out something irrelevant, or fight the inertia and answer immediately . Whatever you do with a document, whenever possible, do it only once.

No need to put off anything indefinitely, in a bunch of upcoming things. For people with ADD, this might as well be called a bunch of things that will remain unfinished. They will become little nightmares on the table or in the room, they will slowly feed the guilt, anxiety and resentment, and they will also take up a lot of space. Get into the habit of doing paperwork immediately. Make the agonizing decision to throw out something irrelevant, or fight the inertia and answer immediately . Whatever you do with a document, whenever possible, do it only once.

17. Create an atmosphere of encouragement around you, not discouragement.

To understand what an atmosphere of despondency and defeat is, most adult patients need only remember school. Now you have grown up and received all the rights and freedoms, so take care not to constantly face reminders of your limitations.

18. Recognize and remember that a certain percentage of projects started and commitments made will inevitably go unfulfilled.

It is better to anticipate failures than to be surprised and suffer about them. Think of them as running costs.

19. Accept calls openly.

People with ADD thrive when they have a lot of work to do. If you understand that not all of them will turn out to be a gold mine, and do not fall into perfectionism and scrupulousness too much, you can do a lot and avoid problems. It's far better to be too busy than not busy enough. There is an old saying: if you want to get a job done, ask a busy person.

20. Set deadlines.

21. Break big tasks into small ones.

Set deadlines for small fragments, and large tasks will be solved. It is one of the simplest and most powerful structuring tools. A big deal suppresses the patient's imagination. The very thought of trying to fulfill it makes one turn away. But if a large whole is broken down into small parts, they may seem quite capable. (For example, I was only able to write a book thanks to this technique. )

)

22. Prioritize, don't procrastinate.

If you can't resolve an issue at once, remember to prioritize it. When an adult with ADD gets into time trouble, he loses his sober view of things: paying a parking ticket can seem as urgent as putting out a fire on a wastebasket. Sometimes a person is simply paralyzed. So prioritize. Take a deep breath. Do the important things first. Then move on to the second and third tasks. Do not stop. Procrastination is a hallmark of ADD in adults. You will need serious self-discipline to notice and prevent it in time.

23. Accept the fear if things are going too well.

Put up with nervousness in the moments when everything seems too easy, when there is no conflict. Don't make things difficult just for the sake of stimulation.

24. Pay attention to where and how you work best.

In a noisy room, on a train, wrapped in three blankets, with music, anything. Children and adults with ADD sometimes do their best under rather strange circumstances. Allow yourself to work the way you like best.

Children and adults with ADD sometimes do their best under rather strange circumstances. Allow yourself to work the way you like best.

25. Remember that doing two things at the same time is okay.

You can knit and talk, take a shower and think about serious things, go for a run and plan a business meeting. Often people with ADD need to do several things at once, otherwise nothing will work at all.

26. Do what you are good at.

Again, if it seems easy, it's okay. There is no such law to do only what you can do poorly.

27. Take time to collect your thoughts between tasks.

People with ADD find it difficult to bear the transition from one thing to another, and mini-breaks will help with this.

28. Keep notebooks in your car, by your bed, or in your jacket pocket.

You never know when a good idea will come to mind or something will need to be remembered.