Husband calls me crazy

Why Men Need to Stop Using The Word "Crazy" During Arguments

“You’re crazy!” is something many of us, men and women, have been saying since we were kids. Back then, it might have been a knee-jerk, dubious response used when another kid bragged about how fast he could run or when a buddy made a claim about eating an entire pizza in one sitting. But now we’re adults, and in relationships with other adults. And in 2018, calling your partner crazy, particularly when you’re arguing, is problematic.

“It depends on the intent behind the use of the word,” says Heidi McBain, LMFT, a therapist in Flower Mound, Texas. “If someone is using it in a cute, joking way and the other person is fine with that, then there probably wouldn’t be an issue. However, if the person is using it to be hateful and mean, then the other person probably feels the use of this word at a deeper, much more hurtful level.”

To some, “crazy” is a loaded term in any context. There are those who would say that even blithely commenting, “Traffic is crazy today!” trivializes mental illness and perpetuates negative ableist coding that psychiatric illnesses are a deficiency or failing. Many people also argue that “crazy” accusations are misogynistic because women are called crazy more often than men are. The viewpoint of feminist women and men is that calling your partner crazy when she expresses anger or other emotions during an argument is just one manifestation of the deeply engrained idea that women don’t know what they’re talking about, even when it comes to their own perceptions and emotions.

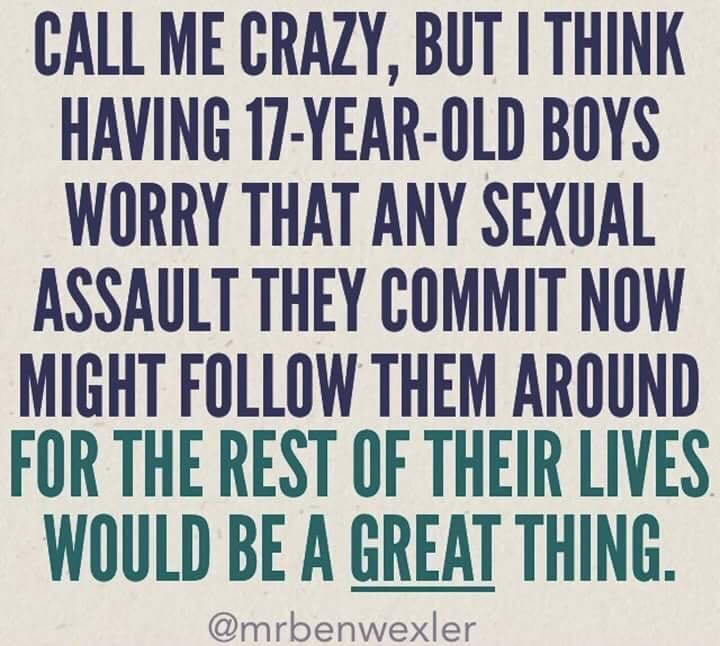

“’Crazy’ is a strongly gendered insult in that it is rarely used against men, and the purpose is to discredit the speaker without regard for the content of their concern.”

“Because such attitudes are embedded in a social environment where it’s considered acceptable to demean women, such statements will be seen as legitimate by others,” says Johanna Higgs, doctoral candidate in anthropology at La Trobe University in Melbourne and founder of Project MonMa an international women’s rights organization. “It is essentially a way of sustaining male hegemony and keeping women submissive. ”

”

Much like blaming women for sexual assault and harassment and calling women whores, the acceptableness of calling women crazy is so embedded in the cultural subconscious that it’s seen as a natural part of the world, Higgs says.

The roots of the perception that women are called crazy more than men are is deep and historical, says David Klow, LMFT, owner of Skylight Counseling Center in Chicago, Northwestern University instructor and author You Are Not Crazy: Letters From Your Therapist. The term “hysteria” comes from the Greek word for womb and was considered an exclusively female mental disturbance only deleted from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1980. That’s one reason the idea that women are inherently more emotional and prone to craziness has stuck. Hell, as recently as 2015 there was still debate among some great minds of our time about whether women were too rash and overemotional to be president.

“’Crazy’ is a strongly gendered insult in that it is rarely used against men, and the purpose is to discredit the speaker without regard for the content of their concern,” says Nicole Prause, Ph. D., a psychologist and neuroscientist at the Libero Center in Los Angeles.

D., a psychologist and neuroscientist at the Libero Center in Los Angeles.

Delegitimizing your partner’s feelings is a cop-out when you don’t want to deal.

I could go on about deep-seated patriarchal ties to calling women crazy and cite studies of men and women that have found no gender differences in levels of felt emotion. You could argue that women aren’t called crazy more than men are because you have plenty of female friends who insist their ex-boyfriends or husbands are batshit nuts.

But whether you believe that “crazy” is a tool of the patriarchy to keep women down or believe women fling accusations of craziness during arguments as regularly as men do doesn’t matter. If the word is used in anger in the context of an argument with your partner, it’s always a bad idea. A response such as, “You’re crazy,” or “You’re being really crazy right now,” (note: the latter isn’t any better) when your partner expresses her feelings is at best unhelpful and at worst, incredibly damaging to her and to your relationship.

The reality is that some people — both men and women — don’t have the greatest coping skills. They might react in ways that are outside of your perception of normal, acceptable behavior. Even if your partner yells at you and throws things when you’re fighting, for example, a lot of people might agree with you that she’s acting crazy. But what is telling her that going to help? She’s never going to agree with you or thank you for your armchair psychiatric evaluation.

Like a lot of things, it boils down to, do you want to be right or do you want to be happy?

“If we look at how we show up and fight in our relationship, it says a lot more about ourselves than it does about the person we’re calling crazy, even if your partner is acting in a way you find crazy,” Klow says. “How might it be possible to instead show up as compassionate and understanding and work toward greater clarity?”

It isn’t easy, Klow admits. Arguments trigger the fight or flight response in the brain, and when we fight, our prefrontal cortex, the part that controls reasoning, problem solving and language, goes “offline,” he says. So often when people fight, they try to manipulate the narrative or framework of the conversation, usually unconsciously, because they’re feeling threatened. In other words: Delegitimizing your partner’s feelings, is a cop-out when you don’t want to deal.

So often when people fight, they try to manipulate the narrative or framework of the conversation, usually unconsciously, because they’re feeling threatened. In other words: Delegitimizing your partner’s feelings, is a cop-out when you don’t want to deal.

“It’s a primitive defense mechanism,” Klow continues. “But what an effective defense that is, when someone’s blaming you or accusing you of something, to say, ‘You’re just crazy, that’s all in your head.’”

“If we look at how we show up and fight in our relationship, it says a lot more about ourselves than it does about the person we’re calling crazy, even if your partner is acting in a way you find crazy,”

Using “crazy” in an argument creates other core problems as well, Prause says.

For one thing, “it is nonspecific,” she says. “If you ask someone to be ‘less crazy’ in the most optimistic circumstances, that person will have no idea what exactly they should change to exhibit behaviors that appear less crazy to their partner. ”

”

In addition, saying your partner is being crazy in the midst of a real fight is name-calling, she says, and inherently mean.

“It’s often part of expressing contempt for a partner,” Prause says. “Contempt in couples’ discussions is the most negative form of emotion that we study and is a strong predictor of later divorce.”

Will all women react to a crazy accusation in the same way? No. To some, it will just be annoying. To others, it will be enraging. And for those with a trauma history, it could be emotionally damaging.

“Someone predisposed to negative moods or depression already have that learned helplessness that they can’t affect change in their world,” she says. “So when someone with that history is dismissed in that way, she’s likely to think, ‘See, I can’t do anything right’ and feel hopeless.”

If your partner feels empowered to speak and be assertive, on the other hand, the argument can easily escalate, with her throwing it back at you (“I’m crazy? No, you’re crazy!”), which obviously isn’t any good either.

Some psychologists say that it’s typical but also lazy of hetero men to say, “I just don’t understand women, they’re so complicated,” Prause says.

“What they mean, technically, by ‘lazy’ is that men are engaging with less effort to interpret emotions that are portrayed,” she explains. “When they have a lack of understanding, rather than attempting to communicate, solicit more information, or become more adept at identifying emotions accurately in their partner, they fall back on saying, ‘You’re crazy’ or ‘You’re too complicated.’”

“When we start thinking or feeling something that falls outside of our realm of normal, instead of dismissing those parts of ourselves, can we instead have a more friendly and investigatory relationship even with ourselves?”

A more compassionate approach, Klow says, is to investigate why your partner is acting the way she is rather than shutting her down with a judgment that she’s being crazy. It’s more helpful to say something like, “There must be a good reason why you’re acting this way and I want to understand,” Klow says.

“Labeling someone crazy is ‘othering’ them, and I see both men and women othering each other,” Krow says.

If you care about your relationship, you need to figure out a way to show up as your “best self” even in the face of ugly behavior.

“It’s a natural human response to dismiss that other person,” with a crazy accusation, Klow says. “It’s our ego’s way of controlling the world around us. When we start thinking or feeling something that falls outside of our realm of normal, instead of dismissing those parts of ourselves, can we instead have a more friendly and investigatory relationship even with ourselves?”

Ideally, if you feel a “You are crazy!” welling up on the tip of your tongue while you’re arguing with your partner, you should de-escalate the situation by taking a break. Couples that stay together tend to have the ability to de-escalate, even during an argument, Prause says. When couples like this argue, if one person accuses the other of overreacting, the other is able to say, “You’re right, I did overreact to that part,” and the first person responds with something like, “Thank you for saying that, I think I overreacted, too. ” But if you’re not that kind of couple, take a break, especially if a “crazy” has already been leveled.

” But if you’re not that kind of couple, take a break, especially if a “crazy” has already been leveled.

“Once it’s gone there, you’re done for now,” Prause says. “Don’t try to talk through it.”

In fact, thinking you need to “hash it out” immediately is one of the biggest mistakes many couples make, she says. It’s usually more helpful to take a break for a specified amount of time.

“Let the other person know you’re not running away,” she says. “Say you’ll be back in an hour and actually do come back, even if it’s just to say that you haven’t cooled down yet and need more time.”

This article was originally published on

When Your Partner Accuses You of Being “Crazy"

During my initial session with a client who is having relationship issues, he or she often says, “It's me. I’m the problem.” Yet as we delve into specific circumstances, it is clear that the client is not at the root of the couple’s dysfunction. He or she has a partner who continually deflects.

He or she has a partner who continually deflects.

Deflection is a common, universal, and unconscious defense mechanism, yet when used to an extreme, it can blind a person to the information he or she needs to be close to others. Almost like a force field around a person’s ego, it maladaptively keeps out the material that causes tension regarding who a person is and what he or she believes.

Having a partner who routinely deflects often results in a person feeling punished for having any feeling that differs from the partner. The defense may be especially robust if a person has a feeling about the partner that the partner does not appreciate.

For example, say Sally is hurt because of a comment Tim made while out to dinner with friends the previous night. “Sally won’t get that promotion because she’s too naïve. Her employees would run circles around her,” Tim said as he chuckled.

Perhaps Sally is very trusting, but the term naïve is slightly degrading and Tim’s belief that Sally will not move up in her field understandably hurts Sally. Yet when Sally shares with Tim that his comment made her feel bad, Tim deflects and says, “I didn’t say it like that. You are making stuff up. You are crazy. We had a good time last night. Why do you have to ruin it?” Now, even more upset, Sally attempts to explain why the comment hurt her, but Tim continues to deflect accountability, “I was joking. Can’t you take a joke? You're too sensitive.”

Yet when Sally shares with Tim that his comment made her feel bad, Tim deflects and says, “I didn’t say it like that. You are making stuff up. You are crazy. We had a good time last night. Why do you have to ruin it?” Now, even more upset, Sally attempts to explain why the comment hurt her, but Tim continues to deflect accountability, “I was joking. Can’t you take a joke? You're too sensitive.”

Because Sally does not share the rigorous need to deflect, and because Tim is absolutely adamant that he did nothing wrong, Sally begins to doubt herself and her feelings. “Is all of this in my head?” she wonders. She lets it go, blaming herself. Yet, over the course of several months, if the dynamic is repeated, Sally may begin to think she is the problem.

Alternatively, if Tim does not deflect, he may be able to understand how and why his sentiment caused discomfort in Sally. Acknowledging that he grasps why the comment hurt Sally’s feelings, owning it, and repairing the conflict by rephrasing, “Sally, you have a big heart, I worry that manipulative employees may try and take advantage of you, but I am sure you will handle it like a pro,” helps Sally instead of hurts her.

Tim gets his opinion across, which may provide Sally with important insight, but it is relayed in a respectful, supportive, and encouraging manner. It is important that both parties see, understand, and respect each other’s perspectives. This is not possible when one party continuously and robustly deflects.

In the long run, if one person is shamed or dismissed for having any feeling that contradicts a partner’s, he or she may stop acknowledging how he or she feels in the relationship. Stifling feeling states within the context of a close relationship may eventually lead to symptoms of anxiety and depression. This may inflate the deflector’s belief that the person has “issues.”

The tricky aspect regarding this dynamic occurs when the deflector accuses the other person of deflecting. Often an individual who uses deflection to a fault also utilizes projection. He or she may constantly accuse the person of having character defects that he or she actually embodies but refuses to see. For example, A narcissist frequently calls his or her partner a narcissist.

For example, A narcissist frequently calls his or her partner a narcissist.

Taking the example above, the deflector may say, “I am telling you the truth, but you can’t hear it. Being a manager is not for you. You just never want to listen to me.” The key in this situation is to understand the criticism as a projection. It may be that the deflector is a poor business manager because he is rarely accountable and barely listens to ideas that are not his. Responding calmly and logically to the projection is important.

“I understand you believe I do not listen, so that may hurt me in business. I get it. I’ll keep that in mind when I get the new position.”

Ultimately, if a partner deflects, projects, and attempts to continually disempower a person, the person may need to take note of this so he or she does not surrender to the belief that he or she is impaired. Maintaining a cohesive sense of self in the midst of deflections and projections is difficult but important.

A relationship takes two. Respecting and honoring each other’s feelings and perspectives is essential. A partner who supportively and respectfully attempts to provide a person with insight in a way that encourages and empowers is a loving and healthy partner. A partner who refuses to try to understand a person’s feelings because he or she pervasively deflects and projects may need professional help.

Respecting and honoring each other’s feelings and perspectives is essential. A partner who supportively and respectfully attempts to provide a person with insight in a way that encourages and empowers is a loving and healthy partner. A partner who refuses to try to understand a person’s feelings because he or she pervasively deflects and projects may need professional help.

#1

#2

#3

#4

#5

#6

#7

#8

#9,0002

#10

#11

#12

#14

#15

#16

#17

#18

#19

#20

#21

#22

Woman. ru experts

ru experts

-

Maxim Sorokin

Practicing psychologist

620 responses

-

Nikita Nosov

Practicing psychologist

8 answers

-

Maria Burlakova

Psychologist

3 answers

-

Nikitina Anna Viktorovna

Specialist of Oriental practitioners

29 answers

-

Vyacheslav is rich

Certified practitioner.

..

.. 254 answers

-

Daria Gorbunova

Practicing psychologist

142 answers

-

Olga Dmitrievna Novikova

Practicing psychologist...

13 answers

-

Egor Mazurok

Clinical psychologist

11 answers

-

Alla Buraya

Psychologist

34 answers

-

Nidelko Lyubov Petrovna

Practicing psychologist

226 answers

#23

January 2008, 11:12

#26

Invented stories

-

I am infuriated by my husband with his children and grandchildren .

..

.. 312 answers

- 9000

The man immediately warned that all the property was recorded on children

472 answers

-

Such a salary - I don't want to work

309 answers

-

A lie 22 years long. How to destroy?

654 answers

-

Husband left, 2 months of depression... How will you cope if you are left all alone?

153 replies

#28

#29

#30

#31

#32

#33

#35

#36

New topics

-

I suspect a guy in lies

No answers

- 9000

Will the former return?

No answers

-

Relations.

and if I love another

and if I love another 2 answers

-

Have you burned out in a relationship?

No answers

-

Is this true?

8 answers

#37

#38

666666 #39

#40

#41

9000 #42 9000 9000