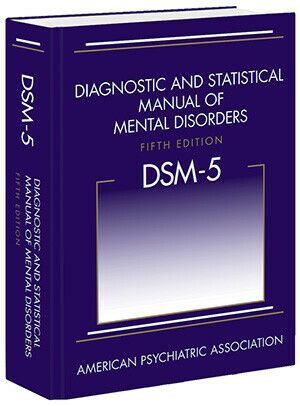

Mental health dsm

What is the DSM?

The DSM is a reference handbook that most U.S. mental health professionals use to reach an accurate diagnosis. The latest version of the manual is the DSM-5-TR.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR) was released on March 18, 2022 by the American Psychiatric Association (APA).

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a formal classification of mental health disorders, featuring symptoms, diagnostic criteria, culture and gender-related features, and other important diagnostic information. The DSM does not include treatment guidelines.

In other words, the DSM is a tool and reference guide for mental health clinicians to diagnose, classify, and identify mental health conditions.

The DSM also includes “specifiers.” These are extensions to the formal diagnoses that specify one or more particular features, like onset or severity. A diagnosis can have one or more specifiers to make it more precise.

In other words, because a mental health condition doesn’t always present itself in the same way, a DSM specifier can better describe particular scenarios.

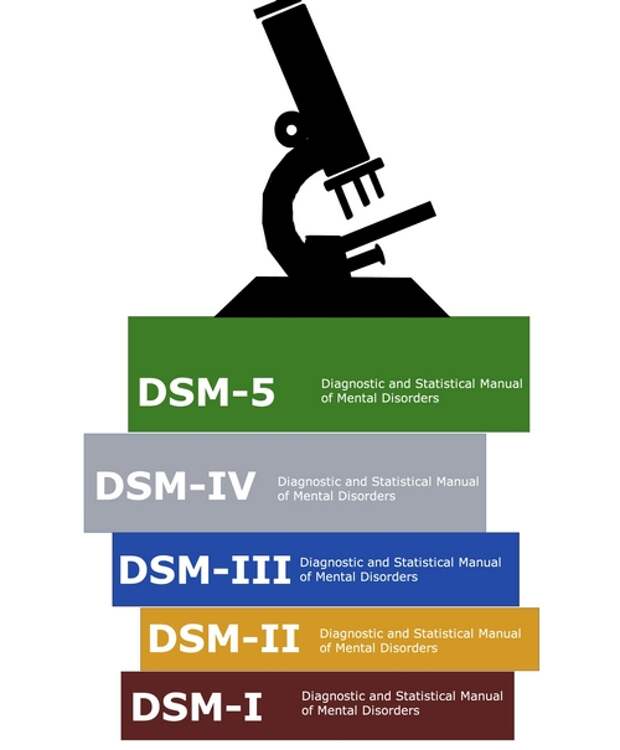

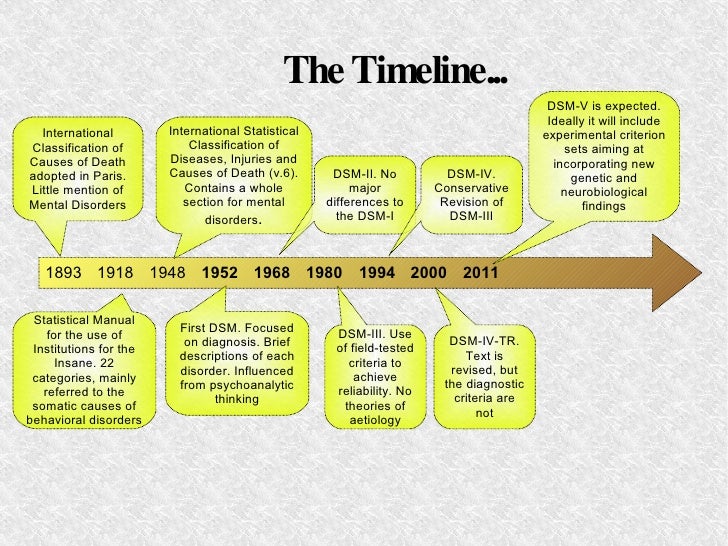

The DSM has had many revisions, to clarify, add, or remove mental health diagnoses according to the latest research and clinical consensus.

It took more than 13 years to update and finalize the book’s fifth edition and about 10 years to release the current text revision.

The DSM-5 was released in 2013 and the current version released in 2022 is the DSM-5-TR.

The difference between a new edition and a text revision is that the first one is released when new research supports the need to create, remove, or significantly revise key aspects of existing diagnoses.

A text revision, on the other hand, refers to editing the existing text to clarify some concepts, introduce inclusive language, or update statistics and references. Sometimes, like it’s the case with the DSM-5-TR, a new diagnosis might be introduced.

The first edition of the DSM was published in 1952 following an increased need to classify and define mental conditions, especially in veterans returning home after World War II.

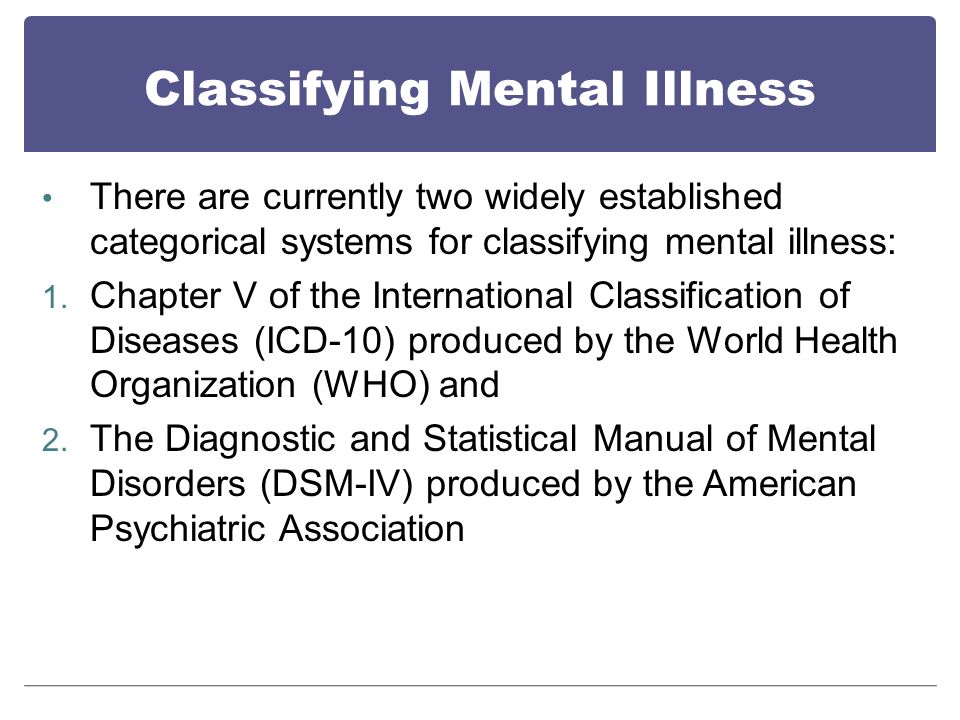

The DSM was created to catalog mental health conditions similar to its counterpart, the International Classification of Disease (ICD).

The ICD is published by the World Health Organization (WHO) and catalogs both physical and mental conditions.

The DSM-II was released in 1968 and focused on broadening terms and definitions from the original DSM to diagnose mental health conditions better.

The biggest shift in the history of the DSM came as a result of the DSM-III, published in 1980.

This edition listed 265 categories — a big increase from 182 in the previous edition. This jump was due to an expansion of disorder subtypes, which allowed for more accurate classifications and options for a diagnosis.

The DSM-III also saw the removal of “homosexuality” as a mental condition category.

The DSM-III would later receive an update and be revised and renamed in 1987 as the DSM-III-R.

The next edition, the DSM-IV, was published in 1994 and was created alongside the WHO’s International Classification of Disease, 10th edition. This aimed to decrease inconsistencies in terminology between the two manuals.

The DSM-IV would see one final revision in 2000, named the DSM-IV-TR before the DSM-5 was released in 2013.

The latest text revision of the DSM-5 was released in 2022.

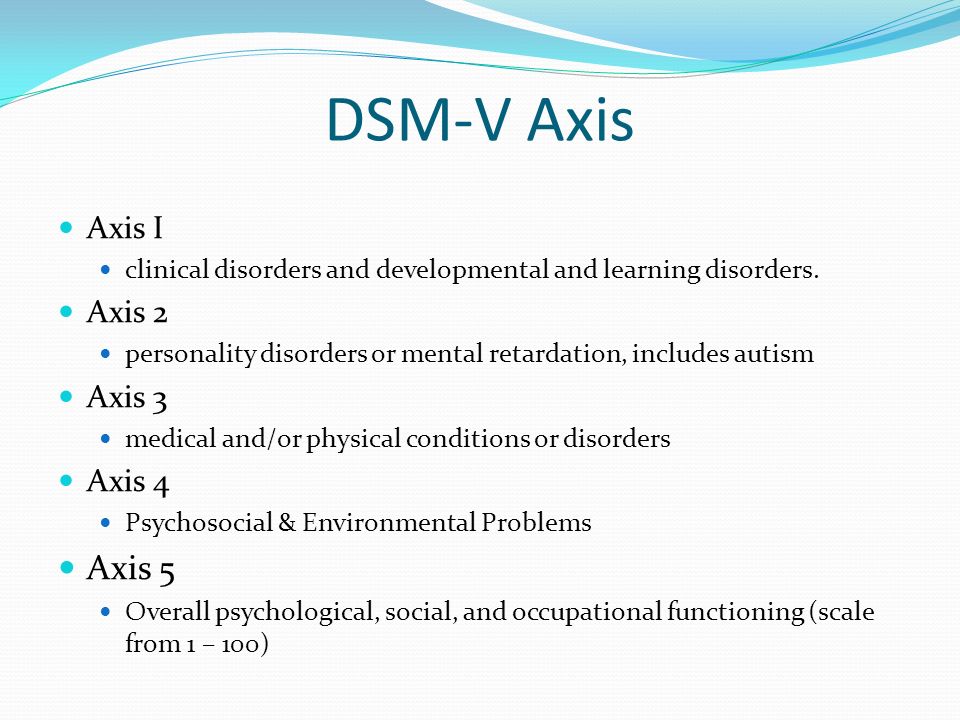

One of the biggest changes in the DSM-5 is the removal of the multiaxial assessment system to categorize diagnoses.

This evaluation method was based on multiple factors, specifically five “axes”:

- clinical disorders

- personality disorders

- general medical disorders

- psychosocial and environmental factors

- global assessment of functioning

The system was removed and replaced with a streamlined diagnostic method that combines axes I, II, and III into 1.

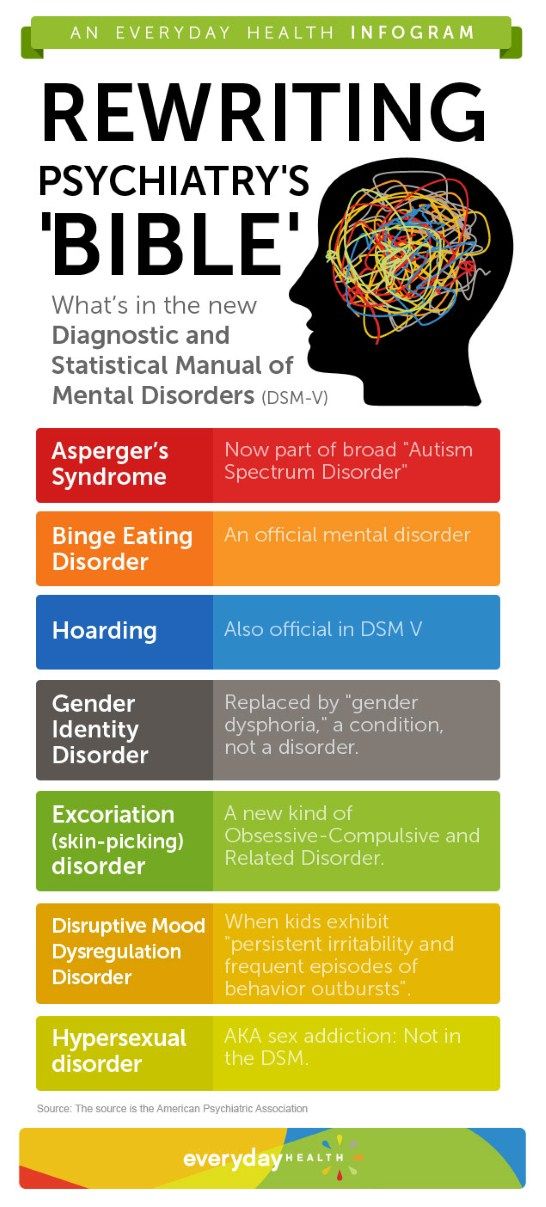

Additional changes in the DSM-5 include broadening the definitions to clarify certain conditions.

For example, the diagnostic label autism spectrum disorder now comprises four previously separate conditions:

- autistic disorder

- Asperger’s disorder

- childhood disintegrative disorder

- pervasive developmental disorder

The DSM-5 is organized into three sections and an appendix.

Section II of the DSM-5 is the lengthiest because it lists all of the mental health disorders.

Here are the DSM sections:

Section I: DSM-5 Basics

This section includes an “Introduction” and “Use of the Manual” chapters, as well as a “Cautionary Statement for Forensic Use of DSM-5” chapter.

Section II: Diagnostic Criteria and Codes

This section includes classifications and definitions of mental health disorders.

These conditions are organized alphabetically and developmentally, with all childhood conditions listed before adult on-set conditions.

Section III: Emerging Measures and Models

This section comprises chapters that discuss applying the newest mental health information — for example, assessment measures and how to account for cultural influences.

It also includes newer conditions that require further study before entering the general diagnostic classification — for example, caffeine use disorder and internet gaming disorder.

Appendix

The final section contains supplemental information such as a list of changes from the DSM-4 to the DSM-5, a glossary of technical terms, and a list of DSM-5 advisors.

Major changes in the DSM-5 from the DSM-IV

Below are links to explore additional updates and changes to the DSM-5:

- DSM-5 Released: The Big Changes

- DSM-5 Changes: Depression & Depressive Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Anxiety Disorders & Phobias

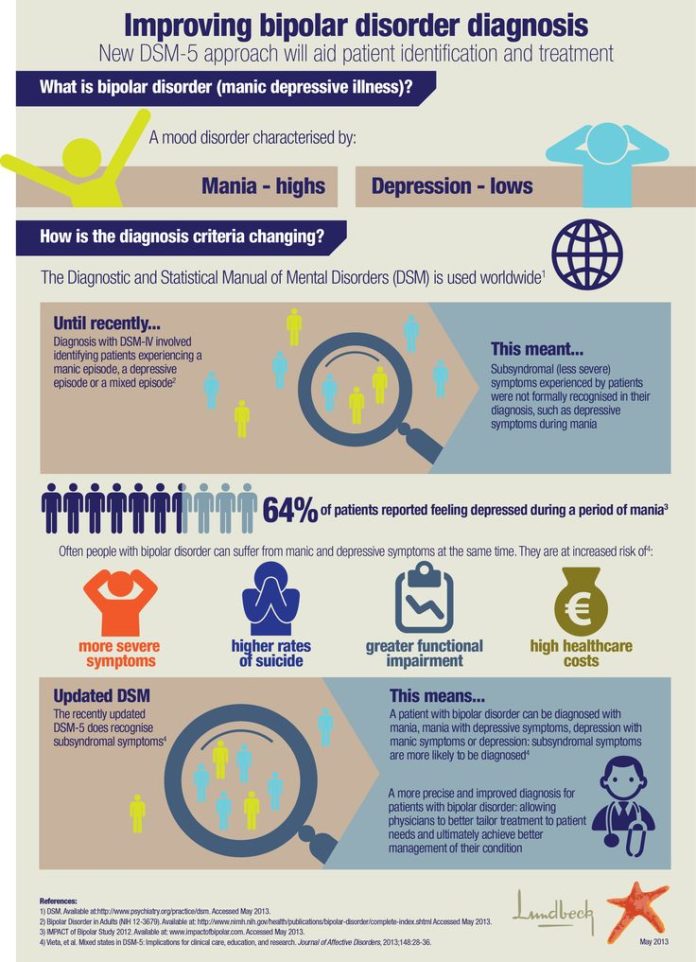

- DSM-5 Changes: Bipolar & Related Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Schizophrenia & Psychotic Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- DSM-5 Changes: Addiction, Substance-Related Disorders & Alcoholism

- DSM-5 Changes: PTSD, Trauma & Stress-Related Disorders

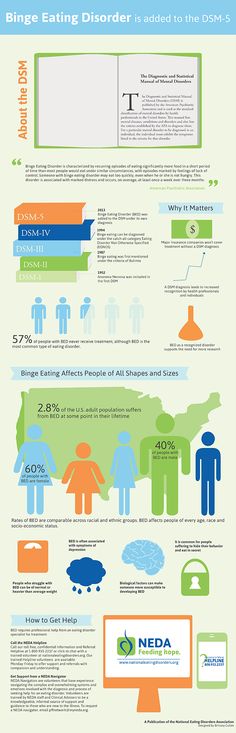

- DSM-5 Changes: Feeding & Eating Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders

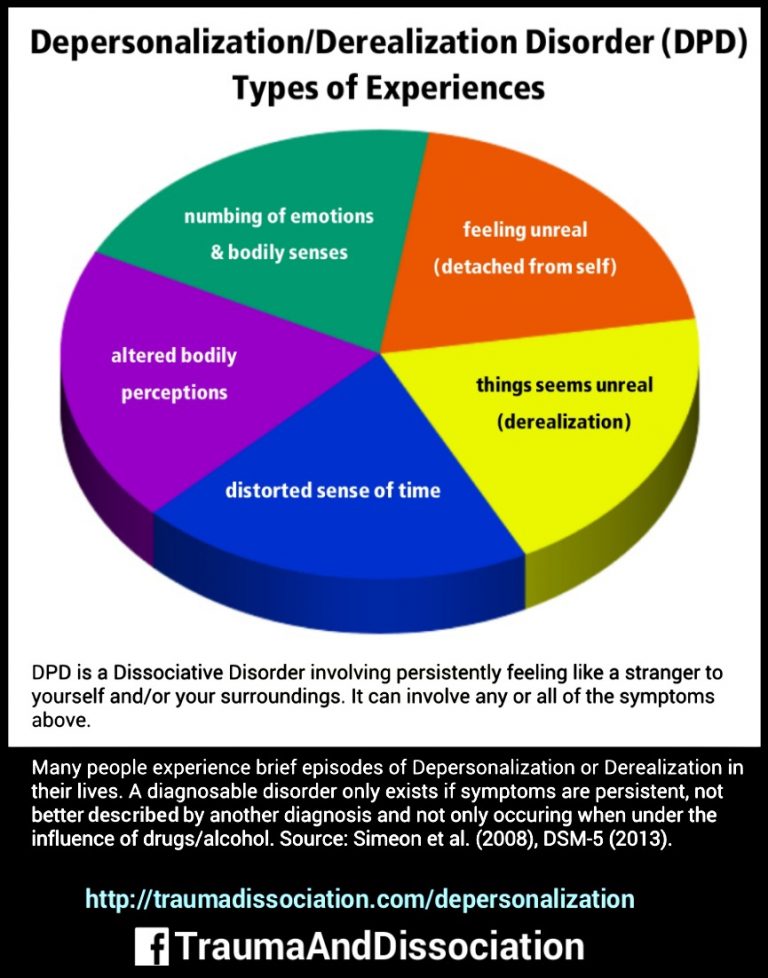

- DSM-5 Changes: Dissociative Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Personality Disorders (Axis II)

- DSM-5 Changes: Sleep-Wake Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Neurocognitive Disorders

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR) is an edit of the DSM-5 that includes:

- a revision of the original descriptive text in the DSM-5, specifically under these headings:

- recording procedures

- specifiers

- diagnostic features

- associated features

- prevalence

- development and course

- risk and prognostic factors

- culture-related diagnostic issues

- sex and gender-related diagnostic issues

- association with suicidal thoughts or behavior

- functional consequences

- differential diagnosis

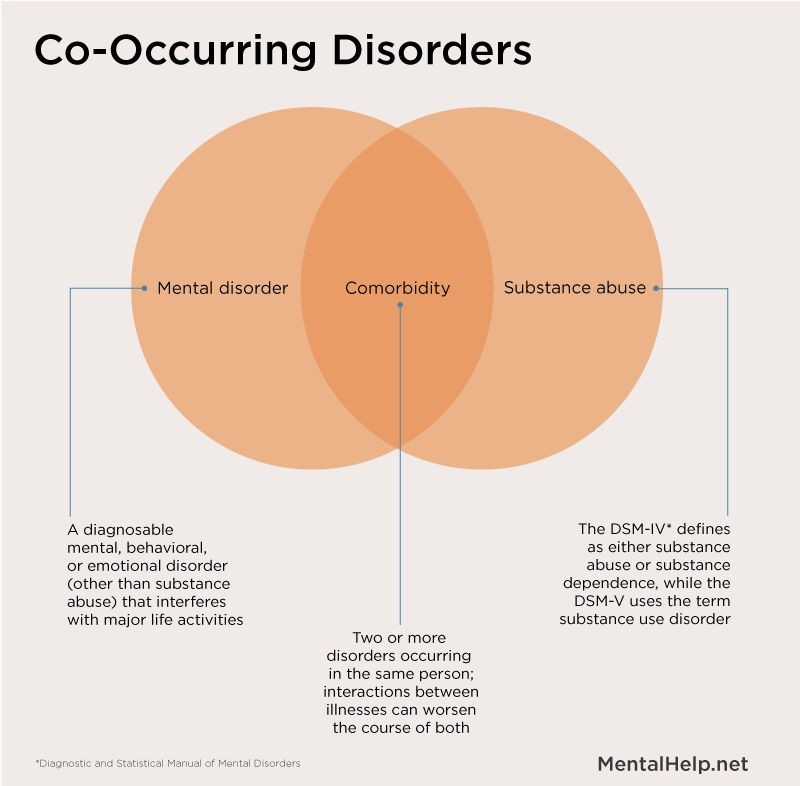

- comorbidity

- new and updated references to include more recent literature

- new text regarding the impact of discrimination and racism on mental health diagnoses

- a list of updated diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, clinical modification (ICD-10-CM), including codes related to suicidal behavior and nonsuicidal self-harm

- one new diagnosis (prolonged grief disorder) in section II, under trauma- and stressor-related disorders

- changes in language in the gender dysphoria chapter, going from “desired gender” to “experienced gender”

- changes in language to refer to gender-related procedures, going from “cross-sex medical procedure” to “gender-affirming medical procedure”

- changes in language in sex-related assignments, going from “natal male” or “natal female” to “individual assigned male at birth” and “individual assigned female at birth”

This is how the DSM-5-TR is indexed:

- DSM-5-TR Classification

- Preface

- Section I: DSM-5-TR Basics

- Introduction

- Use of the Manual

- Cautionary Statement for Forensic Use of DSM-5-TR

- Section II: Diagnostic Criteria and Codes

- Neurodevelopmental Disorders

- Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders

- Bipolar and Related Disorders

- Depressive Disorders

- Anxiety Disorders

- Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders

- Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders

- Dissociative Disorders

- Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders

- Feeding and Eating Disorders

- Elimination Disorders

- Sleep-Wake Disorders

- Sexual Dysfunctions

- Gender Dysphoria

- Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorders

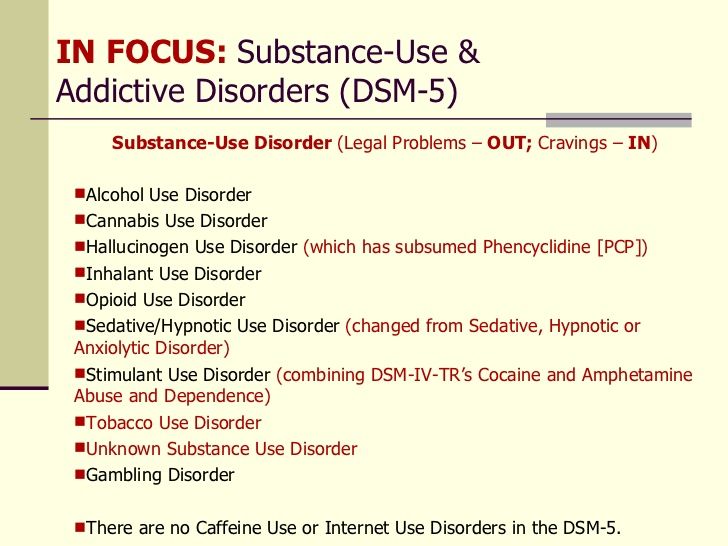

- Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

- Neurocognitive Disorders

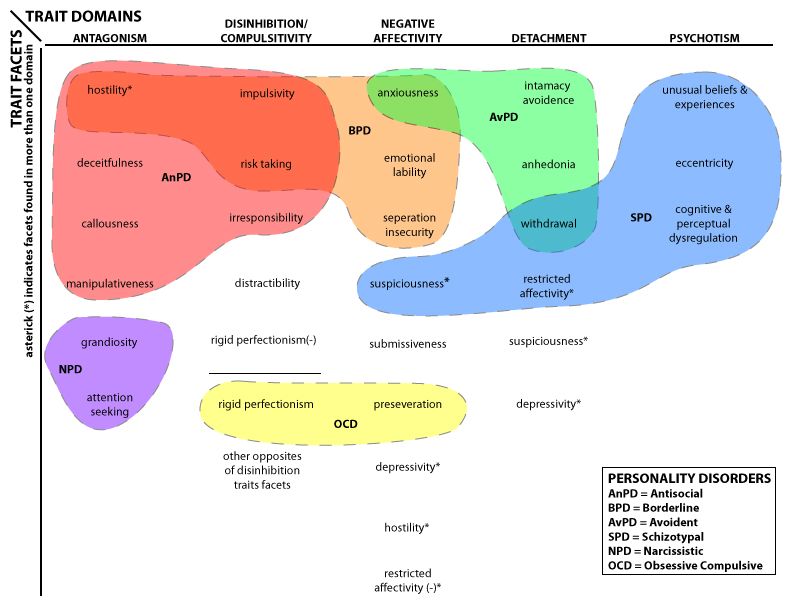

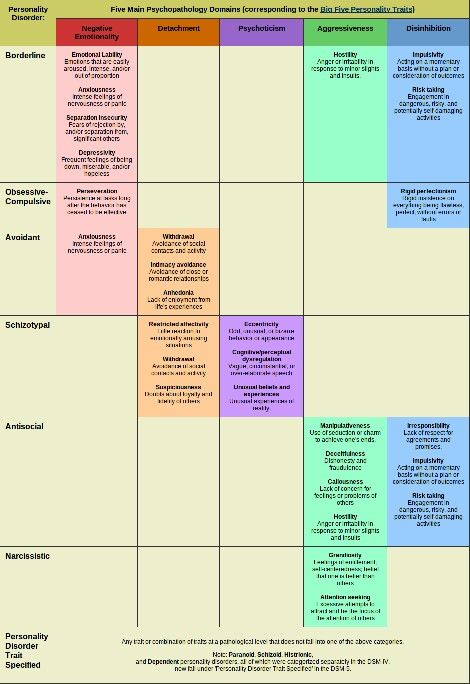

- Personality Disorders

- Paraphilic Disorders

- Other Mental Disorders and Additional Codes

- Medication-Induced Movement Disorders and Other Adverse Effects of Medication

- Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention

- Section III: Emerging Measures and Models

- Assessment Measures

- Culture and Psychiatric Diagnoses

- Alternative DSM-5 Model for Personality Disorders

- Conditions for Further Study

- Appendix

- Alphabetical Listing of DSM-5-TR Diagnoses and Codes (ICD-10-CM)

- Numerical Listing of DSM-5-TR Diagnoses and Codes (ICD-10-CM)

- DSM-5 Advisors and Other Contributors

- Index

More than 200 mental health experts contributed to the DSM-5-TR.

The DSM-5 offers an extensive list of conditions and symptoms that can aid mental health professionals in reaching accurate diagnoses. The latest version is the DSM-5-TR.

The manual has come a long way since its first edition and now provides diagnostic criteria for 193 mental health conditions.

The DSM is a living document that continues to change over time as we learn more about human cognition and behavior.

DSM | Psychology Today

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a guidebook widely used by mental health professionals—especially those in the United States—in the diagnosis of many mental health conditions. The DSM is published by the American Psychiatric Association and has been revised multiple times since it was first introduced in 1952. The most recent edition is the fifth, or the DSM-5. It was published in 2013.

The most recent edition is the fifth, or the DSM-5. It was published in 2013.

The DSM coexists with various alternative diagnostic tools, although these other guides are generally less commonly used in the U.S. The most widely consulted counterpart of the DSM, the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD), covers mental health disorders along with a vast number of other health conditions. The ICD is the primary diagnostic tool for mental health professionals outside the U.S.

Contents

- How the DSM Is Used

- How the DSM Has Changed Over Time

How the DSM Is Used

The DSM features descriptions of mental health conditions ranging from anxiety and mood disorders to substance-related and personality disorders, dividing them into categories such as major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and narcissistic personality disorder. These disorders are grouped into chapters based on shared features, e.g., Feeding and Eating Disorders; Depressive Disorders; Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders.

These disorders are grouped into chapters based on shared features, e.g., Feeding and Eating Disorders; Depressive Disorders; Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders.

For each disorder category, the manual includes a set of diagnostic criteria—lists of symptoms and guidelines that psychiatrists, psychotherapists, and other health professionals use to determine whether a patient or client meets the criteria for one or more diagnostic categories. For diagnosis of major depressive disorder, for example, the current DSM states that a person shows at least five of a list of nine symptoms (including depressed mood, diminished pleasure, and others) within the same two-week period. It also requires that the symptoms cause “clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning,” along with other stipulations.

Updates to these diagnostic categories and criteria are made through a years-long research and revision process that involves groups of experts focusing on distinct areas of the manual.

What are the benefits of DSM?

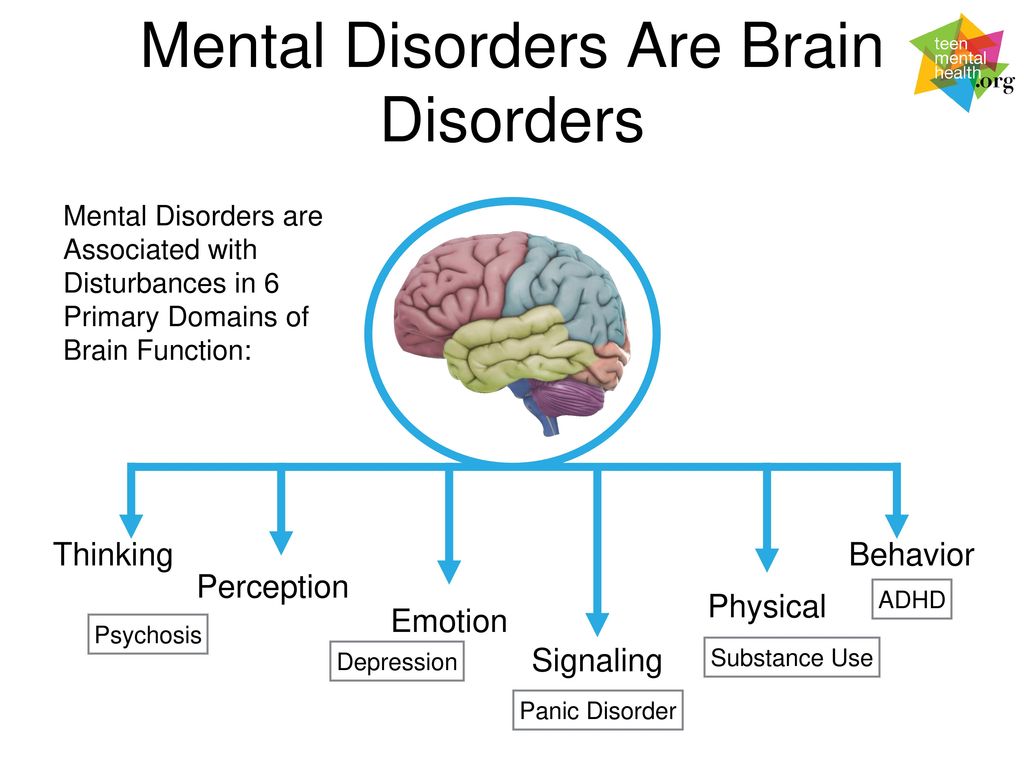

The DSM is important for several reasons. First, it creates a common language to describe mental disorders; developing consistency is key because diagnoses are primarily based on symptoms and family history rather than more objective measures like blood tests or brain scans.

Second, diagnosis makes it possible to study treatments for mental illnesses. When people present to mental health services, professionals need to have some guide as to which treatments will best address particular collections of symptoms. Third, diagnosis facilitates research into the causes of mental disorders. If research in Peru links depression with poverty, a common concept of depression is necessary to investigate similar links in Canada.

Is the DSM helpful for clinicians?

Diagnostic criteria help students and early-career professionals build templates of mental disorders that go beyond a layperson’s impressions—for instance that bipolar disorder describes abnormal moods sustained over weeks or months, not moods that shift over an hour or a day. The DSM establishes a common language for professional communication and research, not to mention insurance codes.

The DSM establishes a common language for professional communication and research, not to mention insurance codes.

However, there are also ways in which mental health professionals don’t view the DSM as clinically useful. After seeing many patients, clinicians gradually form their own mental models of common diagnoses that might differ from the DSM, for example that the published criteria for a particular diagnosis is a little too wide or too narrow. In the end, clinicians may privilege the nosology of their own experience over the official manual that approximates it.

Is the DSM helpful for researchers?

The criterion-based diagnoses listed in the DSM have improved consistency and reliability in classifying mental health conditions over time; clinicians around the world can now largely agree whether a particular patient “meets DSM criteria.” This shift in the DSM has been useful for research, in which the homogeneity of study groups is crucial.

What are some criticisms of the DSM?

Some believe that the failure to develop effective treatments for mental health disorders can in part be traced to a failure of classification, embodied by the long-standing reliance on the DSM. The DSM labels clusters of co-occurring symptoms and sorts them into disorder categories, but there is little evidence that these categories correspond to distinct biological realities. DSM categories may thereby hamper rather than facilitate psychology’s understanding of mental disorders.

How the DSM Has Changed Over Time

The DSM has always been a lightning rod for debate about psychiatric diagnosis and classification. Since the 1950s, various categories of disorders have been added to the manual, altered, or removed altogether based on evolving clinical expertise and research and changes in the field of psychiatry, including a pivot away from psychoanalysis.

As the DSM is the dominant text for making mental health diagnoses in America, many of these changes are considered historically significant, such as when the DSM ceased to classify homosexuality as a form of mental illness in 1973. Other shifts have been controversial, including the omission of Asperger’s disorder from the DSM-5 in favor of a broader autism spectrum disorder category.

What are the current disorder categories in the DSM-5?

The DSM-5 organizes mental disorders into the following chapters: Neurodevelopmental Disorders, Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders, Bipolar and Related Disorders, Depressive Disorders, Anxiety Disorders, Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders, Dissociative Disorders, Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders, Feeding and Eating Disorders, Elimination Disorders, Sleep-Wake Disorders, Sexual Dysfunctions, Gender Dysphoria, Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorders, Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders, Neurocognitive Disorders, Personality Disorders, Paraphilic Disorders, Other Mental Disorders, Medication-Induced Movement Disorders and Other Adverse Effects of Medication, and Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention.

What changes were incorporated into the DSM-5?

The DSM-5 departed from the previous version in several ways. A few of the key changes include:

• Eliminating the multi-axial diagnostic system that required clinicians to rate each client according to criteria other than their main psychological disorder.

• Replacing the diagnoses “Autistic Disorder” and “Asperger’s Disorder” with the overarching label “Autism Spectrum Disorder.”

• Establishing “Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders” as its own group of disorders rather than an anxiety disorder.

• Establishing PTSD as a “Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorder” rather than an anxiety disorder.

• Replacing the diagnoses "Alcohol Abuse" and "Alcohol Dependence" with the overarching label "Alcohol Use Disorder," characterized as mild, moderate, or severe based on the number of symptoms present. The same goes for other diagnoses related to addiction.

• Changing diagnoses with stigmatizing terminology, such as replacing the diagnosis “Mental Retardation” with “Intellectual Disability. ”

”

• Removing the exception of bereavement for the diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder.

• Adding the diagnosis “Mild Neurocognitive Impairment” to categorize cognition problems in old age.

• Reclassifying childhood disorders such as ADHD as neurodevelopmental disorders.

• Adding the diagnosis of “Binge-Eating Disorder.”

What are some criticisms of the changes made to the DSM-5?

Some psychiatrists believe that elements of the DSM-5 are deeply flawed. “Excessive ambition combined with disorganized execution led inevitably to many ill-conceived and risky proposals,” writes Allen Frances, chair of the DSM-IV Task Force and a professor emeritus at Duke, which could lead to misdiagnosis and overprescribing, especially for children.

The most concerning changes of the DSM-5, Frances believed, include incorporating grief into major depressive disorder, diagnosing typical forgetting in old age as Minor Neurocognitive Disorder, and introducing the concept of behavioral addictions.

Are there alternative diagnostic manuals to the DSM?

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD), published by the World Health Organization, is the best known and most popular alternative to the DSM. It contains diagnostic codes used for tracking incidence and prevalence rates, as well as for health insurance reimbursement, for mental and physical disease diagnoses.

Other alternatives to the DSM include the Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual (PDM), Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP), Research Domain Criteria (RDoC), and Power Threat Meaning Framework (PTMF).

What is HiTOP?

The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP)—accounts for mental illness at multiple conceptual levels. It covers specific symptoms (such as avoidance, social anxiety, and suicidality) and traits (callousness, distractibility), but also more general factors with names such as Distress and Fear. The DSM, by contrast, tends to be categorical and binary.

The DSM, by contrast, tends to be categorical and binary.

The HiTOP model is dimensional: A person can score low, high, or somewhere in between on various measures. These severity scores can apply to the more general factors of psychopathology as well as to the narrower ones. As proponents of the model note, evidence suggests that most kinds of psychopathology lie on a continuum with normality.

Essential Reads

Recent Posts

Annotated Index of Articles of the National Psychological Journal

How Our Word Will Respond

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.126-130

Tsukerman G.A.

moreDownload PDF

217

Life with love as the meaning of being in the existential paradigm of relationships

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.119-125

3. c.119-125

Utrobina V.G.

moreDownload PDF

234

Ecopsychological interactions of young children with other subjects of the social environment

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.108-188

Lidskaya E.V. Panov V.I.

moreDownload PDF

214

Application of the methodology "Diagnostics of the mental development of children from birth to three years" in clinical psychology and psychiatry

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.97-107

Trushkina S.V. Skoblo G.V.

moreDownload PDF

219

The Russian Museum of Childhood: On the Development of a Scientific Concept

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.89-96

No. 3. p.89-96

Sobkin V. S. Kalashnikova E. A. Lykova T. A.

moreDownload PDF

182

From Responsiveness to Self-Organization: A Comparison of Approaches to the Child in Waldorf and Directive Pedagogy

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.77-88

Abdulaeva E.A.

moreDownload PDF

138

E.O. Smirnova on the moral education of children

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.69-76

Burlakova I.A.

moreDownload PDF

139

Modern childhood and preschool education are on the protection of the rights of the child: to the 75th anniversary of E.O. Smirnova

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.60-68

p.60-68

Karabanova O.A.

moreDownload PDF

125

E.O. Smirnova in the practice of education

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.52-59

Galiguzova L.N. Meshcheryakova S.Yu.

moreDownload PDF

116

Funny and scary in children's narratives: a cognitive aspect

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.44-51

Shiyan O.A.

moreDownload PDF

173

E.O. Smirnova to the assessment of toys for children

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.35-43

Ryabkova I.A. Sheina E.G.

moreDownload PDF

168

The Artist in the Child

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.26-34

No. 3. p.26-34

Melik-Pashaev A.A.

moreDownload PDF

170

Children's play as a territory of freedom

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.13-25

Yudina E.G.

moreDownload PDF

156

The Dialectical Structure of Preschooler Play

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.4-12

Veraksa N.E.

moreDownload PDF

160

Introduction

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.3

Zinchenko Yu. P.

Details PDF

164

As Covid -19 affects people's mental health

The coronavirus pandemic has affected almost all areas of our daily lives. Isolation, loss of loved ones, the unknown and fear of it all became risk factors for the development of mental illness or exacerbated existing disorders: one in five patients experienced a mental disorder within three months of being diagnosed with COVID-19 1 Scientists agree that the COVID virus -19 has a negative impact on the mental health of patients with no previous history of mental disorders:

Studies show that patients with psychiatric disorders are more vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infection -19 1 Women with a newly diagnosed mental disorder are more likely to be infected than menand higher mortality rate within 30 days of hospitalization, regardless of the severity of the respiratory syndrome with COVID-19 but no mental disorder (8. US scientists identified the series factors that increase the risk of contracting COVID-19 and cause worse outcomes in people with mental disorders 2 : According to World Health Organization survey 3 (WHO), all 130 countries responding to the survey their number included Russia), reported problems in the work of services responsible for the mental health of the population. More than a third ( 35% ) report problems with emergency care, and in 30% of countries there are interruptions in access to medicines for mental, neurological and substance use disorders. The stress that people experience on a daily basis in a pandemic, as well as the worsening epidemiological situation, are forcing both specialists and relatives of patients to do their best to support those who are now facing psychological difficulties in diagnosing COVID-19. More than ever, patients with neurological and psychiatric disorders need specialized care. ### Gedeon Richter is a European independent mid-pharma company, the largest drug manufacturer in Central and Eastern Europe (manufacturing about 200 generic and original drugs in more than 400 forms). |

At the same time, people with previously diagnosed mental illness have a higher risk of infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus 1 , and deaths are almost twice as common 2

At the same time, people with previously diagnosed mental illness have a higher risk of infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus 1 , and deaths are almost twice as common 2  Moreover, the risk for their occurrence was a severe form of the course of the disease or a younger age 4

Moreover, the risk for their occurrence was a severe form of the course of the disease or a younger age 4  5% vs. 4.7% and 27.4% vs. 18.6%, respectively) 2

5% vs. 4.7% and 27.4% vs. 18.6%, respectively) 2  Care for patients with mental disorders was disrupted or suspended in 93% countries of the world. More than half of the countries ( 60% ) complained about interruptions in mental health services for the most vulnerable patients. 67% reported suspension of counseling and psychotherapy.

Care for patients with mental disorders was disrupted or suspended in 93% countries of the world. More than half of the countries ( 60% ) complained about interruptions in mental health services for the most vulnerable patients. 67% reported suspension of counseling and psychotherapy.  The company, whose mission is to improve the health and quality of life of people around the world, pays special attention to the development of medicines for diseases of the central nervous system and women's reproductive health. Gedeon Richter's assets include eight production and research centers, as well as its own plant in Russia, which was opened almost 25 years ago and became the company's first foreign production site. Sales of Gedeon Richter in Russia in 2019accounted for about 17% of total sales in the countries where the company operates. According to DSM Group, Gedeon Richter is in the TOP-20 pharmaceutical companies leading in terms of sales in Russia. Gedeon Richter is a socially responsible company, implementing projects in the field of CSR at the global and Russian levels. A striking example of the company's contribution to the growth of a culture of caring for oneself and one's reproductive health was the social project "Women's Health Week" Gedeon Richter ". To date, the company employs more than 12 thousand people in the world, about 1000 of whom work in Russia.

The company, whose mission is to improve the health and quality of life of people around the world, pays special attention to the development of medicines for diseases of the central nervous system and women's reproductive health. Gedeon Richter's assets include eight production and research centers, as well as its own plant in Russia, which was opened almost 25 years ago and became the company's first foreign production site. Sales of Gedeon Richter in Russia in 2019accounted for about 17% of total sales in the countries where the company operates. According to DSM Group, Gedeon Richter is in the TOP-20 pharmaceutical companies leading in terms of sales in Russia. Gedeon Richter is a socially responsible company, implementing projects in the field of CSR at the global and Russian levels. A striking example of the company's contribution to the growth of a culture of caring for oneself and one's reproductive health was the social project "Women's Health Week" Gedeon Richter ". To date, the company employs more than 12 thousand people in the world, about 1000 of whom work in Russia.