How to punish a 17 year old boy

Disciplining Older Teenagers

Beer cans in a closet, pot in a glove compartment, groundings or curfews ignored, abusive language… not necessarily all new challenges to deal with but many parents feel powerless when faced with disciplining a son inches taller than they are or a daughter who’s buying her own clothes and gas. This becomes even more challenging in the summer prior to college when the teen invokes the “I’ll be on my own soon” mantra that supposedly negates your authority.

While some aspects of discipline change as your child moves into the 16- to 18-year-old range, it is important to realize that these teens still need the security of enforced limits and that they are still dependent upon you in many ways, despite their adult-like appearance or independence. This process is made easier if you have been able to maintain a reasonable connection with your teenager. The more engaged you are in his or her life, the more likely some of these issues can actually be talked through with positive results.

A key to resolving conflicts here, in fact, is treating the teen more as an adult and asking her to reflect on the problem and come up with her own solution.

A 17-year-old daughter was supposed to pick up her younger brother from day camp. Twice she had been so late that the camp had called the mother at work. Thank goodness for cell phones. The mother was able to track down her daughter who claimed (!) to be on her way but had an excuse for being late each time. This mother, who has a history of intimate conversations with her daughter about many issues, simply said she could not get another call from the camp because it was putting her son at risk for renewing the next two-week segment. She expressed the feeling that her daughter was not being responsible here and felt that she should have some consequence for creating this mini-crisis.

Although the daughter still tried to excuse herself, she gradually acknowledged that, at the very least, she was not allowing enough time in case something did go wrong. The mother told her she was old enough to come up with a reasonable consequence for messing up here rather than have the mother simply discipline her. The daughter was able to conclude that she owed a debt to her brother for making him wait and be upset as well as to her mother for upsetting her and having to spend the extra time dealing with this. The daughter’s solution was to agree to take her brother out for a Saturday afternoon, rain or shine (which might mean missing a beach day), which would include a couple of activities of his choice. That would also give her mother some extra free time.

The mother told her she was old enough to come up with a reasonable consequence for messing up here rather than have the mother simply discipline her. The daughter was able to conclude that she owed a debt to her brother for making him wait and be upset as well as to her mother for upsetting her and having to spend the extra time dealing with this. The daughter’s solution was to agree to take her brother out for a Saturday afternoon, rain or shine (which might mean missing a beach day), which would include a couple of activities of his choice. That would also give her mother some extra free time.

Of course it often won’t be that easy. The daughter might have been belligerent, saying the mixups weren’t her fault and refusing to work out a solution with the mother. In fact, she might argue how she is doing her mother a big favor by picking up her brother and it is really very inconvenient for her to do this each day. This is where some parents feel they have few options and often back down with just a scolding or a grounding that frequently isn’t enforced.

It’s important not to stop being an authoritative parent. When the effort to work out a joint solution fails, then it requires that the parent create a consequence that she has some control over. In this case, the mother was taking the train to work to allow her daughter to have access to the car. This allowed the daughter to go to her job, pick up her brother, and still have the opportunity to spend time with friends during the day. So let’s imagine how this mother might have dealt with an uncooperative daughter.

In response to her daughter’s lack of accepting responsibility, the mother chose to take the car back for a week and make temporary alternative arrangements to have her son picked up. The daughter was shocked at losing access to the car. “How will I get to work? I’ll lose my job.” The mother said that it was up to her daughter to resolve that problem, noting that to use the car brings with it a higher expectation of acting responsibly. Many times parents won’t do something like this because they take on the responsibility of making sure their child can get to work. Once you do that, you have lost too much leverage. And it’s not how the real world works.

Once you do that, you have lost too much leverage. And it’s not how the real world works.

A 17-year-old boy, in a fit of anger, punched a hole in his bedroom wall. The parents insisted he pay for the repair and he refused. He was bound for college in the fall and was putting all his money away for personal expenses at school. He didn’t care if there was a hole in “his wall,” conveniently ignoring the fact that it was his parents’ home. They had put money aside to pay for his books. So he was told that the repair money would come from that and he would either have to get more used books or use his savings to make up the difference.

Another 17-year-old son had twice been found to have beer cans in the back of his car. He insisted he hadn’t been drinking nor had his friends been drinking in the car, both rules that had been agreed upon prior to his buying the car with his own money. Since the parents did not believe his explanation, especially in a context of increased moodiness and less responsibility about his schoolwork, they felt some firm response was required. For the next two weeks, they wanted the car’s use to be limited to just going to school and back and no friends could be in the car. “But it’s my car,” said the son, “and there isn’t anything you can do about it.”

For the next two weeks, they wanted the car’s use to be limited to just going to school and back and no friends could be in the car. “But it’s my car,” said the son, “and there isn’t anything you can do about it.”

However, as is often the case, the parents were paying for the insurance. They were very firm with him, saying that it would only take one call to their agent and the car would have to come off the road. The son didn’t think they would actually do this – usually he had been able to intimidate his parents. But with the support they were getting from a counselor, they convinced him they were serious and he accepted the limits. That also led to further discussions about the negative changes they had seen in him lately and ultimately led to his agreeing to see a therapist.

In a more extreme action, a single mother whose son worked, owned his own car, and paid for his own insurance, had grounded him for being destructive to property in the house and verbally abusive toward her. But Friday night came and he walked out the door, saying there wasn’t anything she could do about it. Using a tough love approach that was being encouraged by her therapist, the mother was able to find a locksmith willing to come to the house that evening and change the locks. Her son banged on the doors and then went to a friend’s for the night when his mother refused to let him in and threatened to call the police if he didn’t stop. He avoided her until Sunday, then came home and asked to talk to her. They discussed how he needed to accept that if he was going to live in the house and be a member of the family, then he had to live with his mother’s rules. If he had a gripe, then it had to be worked out and not acted out. He realized he loved his mother and wanted to continue to live with her, apologized, and managed to be more reasonable in his behavior.

But Friday night came and he walked out the door, saying there wasn’t anything she could do about it. Using a tough love approach that was being encouraged by her therapist, the mother was able to find a locksmith willing to come to the house that evening and change the locks. Her son banged on the doors and then went to a friend’s for the night when his mother refused to let him in and threatened to call the police if he didn’t stop. He avoided her until Sunday, then came home and asked to talk to her. They discussed how he needed to accept that if he was going to live in the house and be a member of the family, then he had to live with his mother’s rules. If he had a gripe, then it had to be worked out and not acted out. He realized he loved his mother and wanted to continue to live with her, apologized, and managed to be more reasonable in his behavior.

These are a sampling of examples of how parents can, and need to, assert themselves with older teenagers. But sometimes the relationship with one’s teenager is so frayed and volatile that negotiations just continually break down and the teen remains very defiant, possibly running away or becoming more violent. In these situations, parents need to seek outside help from family therapists and, sometimes, the courts. If you are afraid of your teenager, then you must seek help.

In these situations, parents need to seek outside help from family therapists and, sometimes, the courts. If you are afraid of your teenager, then you must seek help.

A key thread running through all this is that your children will continue to need active, involved parenting right on into their adult lives. It doesn’t stop somewhere in the middle of high school. Recognizing that gives you some leverage to enforce the rules that remain in place even as your children get older. But you must be willing to not be coerced into taking too much responsibility for protecting your child from possible consequences, even when it might impact a job, participation in a sport, or grades. It’s simply part of the never-ending process of your child learning to be responsible for his or her actions.

Disciplining Older Teenagers

Beer cans in a closet, pot in a glove compartment, groundings or curfews ignored, abusive language… not necessarily all new challenges to deal with but many parents feel powerless when faced with disciplining a son inches taller than they are or a daughter who’s buying her own clothes and gas. This becomes even more challenging in the summer prior to college when the teen invokes the “I’ll be on my own soon” mantra that supposedly negates your authority.

This becomes even more challenging in the summer prior to college when the teen invokes the “I’ll be on my own soon” mantra that supposedly negates your authority.

While some aspects of discipline change as your child moves into the 16- to 18-year-old range, it is important to realize that these teens still need the security of enforced limits and that they are still dependent upon you in many ways, despite their adult-like appearance or independence. This process is made easier if you have been able to maintain a reasonable connection with your teenager. The more engaged you are in his or her life, the more likely some of these issues can actually be talked through with positive results. A key to resolving conflicts here, in fact, is treating the teen more as an adult and asking her to reflect on the problem and come up with her own solution.

A 17-year-old daughter was supposed to pick up her younger brother from day camp. Twice she had been so late that the camp had called the mother at work. Thank goodness for cell phones. The mother was able to track down her daughter who claimed (!) to be on her way but had an excuse for being late each time. This mother, who has a history of intimate conversations with her daughter about many issues, simply said she could not get another call from the camp because it was putting her son at risk for renewing the next two-week segment. She expressed the feeling that her daughter was not being responsible here and felt that she should have some consequence for creating this mini-crisis.

Thank goodness for cell phones. The mother was able to track down her daughter who claimed (!) to be on her way but had an excuse for being late each time. This mother, who has a history of intimate conversations with her daughter about many issues, simply said she could not get another call from the camp because it was putting her son at risk for renewing the next two-week segment. She expressed the feeling that her daughter was not being responsible here and felt that she should have some consequence for creating this mini-crisis.

Although the daughter still tried to excuse herself, she gradually acknowledged that, at the very least, she was not allowing enough time in case something did go wrong. The mother told her she was old enough to come up with a reasonable consequence for messing up here rather than have the mother simply discipline her. The daughter was able to conclude that she owed a debt to her brother for making him wait and be upset as well as to her mother for upsetting her and having to spend the extra time dealing with this. The daughter’s solution was to agree to take her brother out for a Saturday afternoon, rain or shine (which might mean missing a beach day), which would include a couple of activities of his choice. That would also give her mother some extra free time.

The daughter’s solution was to agree to take her brother out for a Saturday afternoon, rain or shine (which might mean missing a beach day), which would include a couple of activities of his choice. That would also give her mother some extra free time.

Of course it often won’t be that easy. The daughter might have been belligerent, saying the mixups weren’t her fault and refusing to work out a solution with the mother. In fact, she might argue how she is doing her mother a big favor by picking up her brother and it is really very inconvenient for her to do this each day. This is where some parents feel they have few options and often back down with just a scolding or a grounding that frequently isn’t enforced.

It’s important not to stop being an authoritative parent. When the effort to work out a joint solution fails, then it requires that the parent create a consequence that she has some control over. In this case, the mother was taking the train to work to allow her daughter to have access to the car. This allowed the daughter to go to her job, pick up her brother, and still have the opportunity to spend time with friends during the day. So let’s imagine how this mother might have dealt with an uncooperative daughter.

This allowed the daughter to go to her job, pick up her brother, and still have the opportunity to spend time with friends during the day. So let’s imagine how this mother might have dealt with an uncooperative daughter.

In response to her daughter’s lack of accepting responsibility, the mother chose to take the car back for a week and make temporary alternative arrangements to have her son picked up. The daughter was shocked at losing access to the car. “How will I get to work? I’ll lose my job.” The mother said that it was up to her daughter to resolve that problem, noting that to use the car brings with it a higher expectation of acting responsibly. Many times parents won’t do something like this because they take on the responsibility of making sure their child can get to work. Once you do that, you have lost too much leverage. And it’s not how the real world works.

A 17-year-old boy, in a fit of anger, punched a hole in his bedroom wall. The parents insisted he pay for the repair and he refused. He was bound for college in the fall and was putting all his money away for personal expenses at school. He didn’t care if there was a hole in “his wall,” conveniently ignoring the fact that it was his parents’ home. They had put money aside to pay for his books. So he was told that the repair money would come from that and he would either have to get more used books or use his savings to make up the difference.

He was bound for college in the fall and was putting all his money away for personal expenses at school. He didn’t care if there was a hole in “his wall,” conveniently ignoring the fact that it was his parents’ home. They had put money aside to pay for his books. So he was told that the repair money would come from that and he would either have to get more used books or use his savings to make up the difference.

Another 17-year-old son had twice been found to have beer cans in the back of his car. He insisted he hadn’t been drinking nor had his friends been drinking in the car, both rules that had been agreed upon prior to his buying the car with his own money. Since the parents did not believe his explanation, especially in a context of increased moodiness and less responsibility about his schoolwork, they felt some firm response was required. For the next two weeks, they wanted the car’s use to be limited to just going to school and back and no friends could be in the car. “But it’s my car,” said the son, “and there isn’t anything you can do about it. ”

”

However, as is often the case, the parents were paying for the insurance. They were very firm with him, saying that it would only take one call to their agent and the car would have to come off the road. The son didn’t think they would actually do this – usually he had been able to intimidate his parents. But with the support they were getting from a counselor, they convinced him they were serious and he accepted the limits. That also led to further discussions about the negative changes they had seen in him lately and ultimately led to his agreeing to see a therapist.

In a more extreme action, a single mother whose son worked, owned his own car, and paid for his own insurance, had grounded him for being destructive to property in the house and verbally abusive toward her. But Friday night came and he walked out the door, saying there wasn’t anything she could do about it. Using a tough love approach that was being encouraged by her therapist, the mother was able to find a locksmith willing to come to the house that evening and change the locks. Her son banged on the doors and then went to a friend’s for the night when his mother refused to let him in and threatened to call the police if he didn’t stop. He avoided her until Sunday, then came home and asked to talk to her. They discussed how he needed to accept that if he was going to live in the house and be a member of the family, then he had to live with his mother’s rules. If he had a gripe, then it had to be worked out and not acted out. He realized he loved his mother and wanted to continue to live with her, apologized, and managed to be more reasonable in his behavior.

Her son banged on the doors and then went to a friend’s for the night when his mother refused to let him in and threatened to call the police if he didn’t stop. He avoided her until Sunday, then came home and asked to talk to her. They discussed how he needed to accept that if he was going to live in the house and be a member of the family, then he had to live with his mother’s rules. If he had a gripe, then it had to be worked out and not acted out. He realized he loved his mother and wanted to continue to live with her, apologized, and managed to be more reasonable in his behavior.

These are a sampling of examples of how parents can, and need to, assert themselves with older teenagers. But sometimes the relationship with one’s teenager is so frayed and volatile that negotiations just continually break down and the teen remains very defiant, possibly running away or becoming more violent. In these situations, parents need to seek outside help from family therapists and, sometimes, the courts. If you are afraid of your teenager, then you must seek help.

If you are afraid of your teenager, then you must seek help.

A key thread running through all this is that your children will continue to need active, involved parenting right on into their adult lives. It doesn’t stop somewhere in the middle of high school. Recognizing that gives you some leverage to enforce the rules that remain in place even as your children get older. But you must be willing to not be coerced into taking too much responsibility for protecting your child from possible consequences, even when it might impact a job, participation in a sport, or grades. It’s simply part of the never-ending process of your child learning to be responsible for his or her actions.

How to punish a teenager?

home

Parents

How to raise a child?

How to punish a teenager?

- Tags:

- Expert advice

- teenager

- children in the family

- family relationships

At the word “punishment”, something negative pops up in the mind: retribution, restriction, prohibitions, aggression… It may seem that the use of this concept in education is outdated, because we live in a “humanistic society”, where the cult of “personal freedom” reigns .

However, this is not entirely true. Despite the fact that many types of punishment are indeed a thing of the past or should be there (for example, physical and psychological violence, boycott, etc.), it is very difficult to do without them in the educational process due to objective reasons:

-

punishment defines the boundaries permitted: a teenager often lacks a sense of proportion - he cannot stop at the right moment, and sometimes he just needs outside intervention;

-

Punishment teaches responsibility: in the world there is not only freedom, but also responsibility - a teenager must be ready to answer for his actions;

-

Punishment disciplines: it forces one to think before acting and to calculate the probable consequences of an act.

See also

Punishment or senseless humiliation?

Punishment as a method of pedagogical process

Destructive punishment

All this refers to constructive punishment. However, there are also frankly destructive ones. Let's look at a few examples.

However, there are also frankly destructive ones. Let's look at a few examples.

Sometimes you can come across recommendations from the category of “fight with fire” - when, for example, a teenager who smokes is forced to smoke a large number of cigarettes so that he develops an aversion to them. Such a strategy is questionable, to say the least. Firstly, its effectiveness cannot be considered fully proven, and secondly, one should think about the physical and psychological health of the emerging personality.

The second example concerns the validity of punishments. One of the portals contains an appeal from a mother who complains about the disobedience of a teenager: her son spends a lot of time with friends. The author of the message writes that she needs to learn effective methods of punishment, but at the same time adds that she has no time even to punish the child, because she works all the time.

Maybe the reason for disobedience in this case lies not in the obstinate nature of the son, but in his inner feeling of loneliness? Therefore, before punishing a teenager, you need to find out whether he is really to blame for what happened.

How to punish a teenager for the benefit of a developing personality

-

Punishment should be based on the rules worked out together with the child and adopted by him. This is a kind of “contract” between parents and the child.

-

All types of violence should be absent from the forms of punishment.

-

Punishment, if possible, should immediately follow the offense. A delay is possible in case of illness of a teenager, his stay in stressful and other unfavorable emotional states.

-

One offense cannot be punished twice.

-

The punishment must be commensurate with the offense.

-

If the parent has warned about the punishment for misconduct, then you must adhere to the chosen line.

-

When punishing, show sincere emotions, but do not give the teenager a reason to think that now you have begun to love him less than you loved before the offense.

As practice shows, disobedience is most often observed in families where emotional contact between a parent and a child is broken. This is possible in families with underprotection, where a teenager feels unloved and unnecessary, left to himself, and with his inappropriate behavior he attracts the attention of significant adults.

This also includes families with overprotectiveness, where the demonstrative behavior of a teenager is a desire to escape from the yoke of excessive care.

If harmony, mutual understanding, and trust reign in the relationship between parents and children, then punishments are rarely used.

And one more thing. Before punishing a teenager, ask yourself the following questions:

-

How would I feel if I was punished in this way?

-

Does the teenager understand why he is being punished?

-

Would punishment be good for the child?

Only then make an informed decision. Keep in mind: the frequent use of punishments devalues them.

Keep in mind: the frequent use of punishments devalues them.

A teenager is no longer a child, much is clear and accessible to him, therefore the most effective punishment is an understanding of what he has done, remorse.

Margarita Logvinova

Your relationship with a teenager

The teenager does not want to communicate, you are unable to negotiate peacefully - what to do in such a situation? Take the quiz and get information about your parenting style and your teen's perspective on how you parent them.

Take the test

More on the topic

Games for the emotional growth of children

Child abuser: what to do?

Talking Daughter: Fixing the Situation

How to get your teenager to follow your rules

The point of any punishment is its effectiveness. It is important that a person not only understands that some of his actions are unacceptable, but also does not act like this in the future. Getting a teenager to follow your set of rules is quite difficult. Sometimes it is even more difficult to decide on his punishment. How exactly you need to punish your grown children and how to get obedience from them - in the material of the psychologist Tatyana Nikitina.

Getting a teenager to follow your set of rules is quite difficult. Sometimes it is even more difficult to decide on his punishment. How exactly you need to punish your grown children and how to get obedience from them - in the material of the psychologist Tatyana Nikitina.

Is it necessary to punish

It is believed that the most effective punishments are always based on the fear of experiencing unpleasant physical or moral sensations. But the times when children were beaten with rods or kneeled on peas for misconduct at the end of the week, fortunately, are in the past. Gradually, after the rods, the belt disappears, which means that one can hope that insulting slaps, and offensive slaps, and humiliating words will sink into oblivion. At least in civilized families.

However, there are still few families that have raised a child who no longer needs any punishment by adolescence and only a heart-to-heart talk is enough. There are few teenagers who do not lie (well, almost), maintain order in the room, skip school only with the consent of mom and dad, come home on time and do not make their parents go crazy because "the subscriber's phone is turned off . ..". How should one respond so that the misconduct of teenagers does not happen again?

..". How should one respond so that the misconduct of teenagers does not happen again?

Is it possible to avoid punishment? And if you punish, then how to avoid insults, psychological trauma, and simply worsening relations with a teenager?

There are families where adults apply the type of upbringing that is called "cooperation" in pedagogy. Parents strive not to patronize the child, but to support him in all areas, especially in the emotional one. The child is given enough independence, but an adult is always there, ready to come to the rescue in time, support, calm, explain. Members of such families are united by common values, traditions, they experience an emotional need for each other. When children raised in such families reach adolescence, the problem of punishment, as a rule, is not worth it. Enough conversation, clarification and awareness of one's guilt. But in most families, and especially in those where parenting styles such as authoritarianism or overprotection (or both) were used, or the child grew up under conflicting instructions received from different family members, with guilt and mutual understanding between parents and children, there is Problems. And therefore, parents can achieve the desired behavior only with the help of a system of control and restrictions - in other words, punishments.

And therefore, parents can achieve the desired behavior only with the help of a system of control and restrictions - in other words, punishments.

Of course there is a choice. If you don't want to punish, don't punish. Repeat a hundred times, do everything for the child yourself, hope that it will pass with age, explain to infinity and speak heart to heart. Is it really difficult for you to clean up the mess in his room? Not the first time? Doesn't brush his teeth? Doesn't wash his hair? Nothing, fall in love - this problem will disappear. Skipping school? His business! Can't you, after all, quit your job and accompany him everywhere? It's time to take responsibility for yourself.

This style of parenting is sometimes called "permissive", but it also has the right to exist. Yes, parents turn a blind eye to many undesirable moments in the behavior of their grown children. And they hope that with age everything will change by itself. It doesn't always end in something bad. The time comes, unorganized teenagers suddenly change, stop being late, begin to pay attention to household chores. Typically, such changes occur when a teenager actually takes responsibility for his behavior, and often coincides with the emergence of his own (and not imposed by parents) goals. Or a teenager, having “been ill” with protests, suddenly, on one basis or another, approaches his parents.

The time comes, unorganized teenagers suddenly change, stop being late, begin to pay attention to household chores. Typically, such changes occur when a teenager actually takes responsibility for his behavior, and often coincides with the emergence of his own (and not imposed by parents) goals. Or a teenager, having “been ill” with protests, suddenly, on one basis or another, approaches his parents.

But there are teenagers with whom it is dangerous to use a "permissive" parenting style. According to the classification of the famous psychologist Julia Gippenreiter, these are, first of all, children with clearly expressed traits of an unstable, intensely affective and demonstrative character. With such teenagers, one cannot do without strictness in education. That is, without clear rules, instructions and penalties for non-compliance. And then there are offenses that even the most advanced parents cannot help but respond to (for example, theft, fights, drinking alcohol, drugs).

How to punish

There is no universal recipe for the “correct punishment” that would suit a family with any value system and a child with any type of character. What works in some cases turns out to be useless in others. But still, there is one general rule that is important to follow in the context of applying any sanctions against a teenager: the system of rules and punishments should be extremely clear to the teenager. The rules and sanctions for non-compliance must be transparent, unambiguous and known in advance. Therefore, if your child’s adolescence is not easy, it seems impossible to find a common language, and you stumble upon protest behavior all the time, try creating your own intra-family system of rules.

What works in some cases turns out to be useless in others. But still, there is one general rule that is important to follow in the context of applying any sanctions against a teenager: the system of rules and punishments should be extremely clear to the teenager. The rules and sanctions for non-compliance must be transparent, unambiguous and known in advance. Therefore, if your child’s adolescence is not easy, it seems impossible to find a common language, and you stumble upon protest behavior all the time, try creating your own intra-family system of rules.

Family rules of conduct are a kind of traffic rules. The traffic rules clearly spell out what is allowed, what is prohibited and how non-compliance is punished. If there were no traffic rules, chaos would reign on the roads.

Chaos begins to reign in some families where there is a difficult teenager, conflicting instructions from the parents, but there is no set of clear and unambiguous rules of behavior. If there is not enough respect for each other in the family, and the child is not ready to take responsibility for his behavior, then it is not easy to force the child to obey the rules. Often, a teenager simply learns to bypass the system of rules, stay uncaught, dodge, and so on. Still, it makes sense to clearly define the rules.

Often, a teenager simply learns to bypass the system of rules, stay uncaught, dodge, and so on. Still, it makes sense to clearly define the rules.

The reaction of adolescents to family rules is in many ways reminiscent of the attitude of drivers to traffic rules. There are drivers who comply with traffic rules and rarely violate them and, accordingly, are rarely fined. These drivers internally agree with the rules and consider them fair enough (or are afraid of sanctions, which is also not uncommon). Other drivers do not consider all the rules fair and are not always ready to comply with them, but "accept the rules of the game" - that is, they agree to be punished if they are caught violating. And then there are drivers who do not want to accept the rules of the game, classify themselves as a select group of those who can do what others cannot. Here, all kinds of ksivas, flashing lights and other attributes of exclusivity come into play. There is something similar in the behavior of some teenagers who are capable of incredible tricks, just to behave as they see fit. But even for them, the existence of rules is some deterrent.

But even for them, the existence of rules is some deterrent.

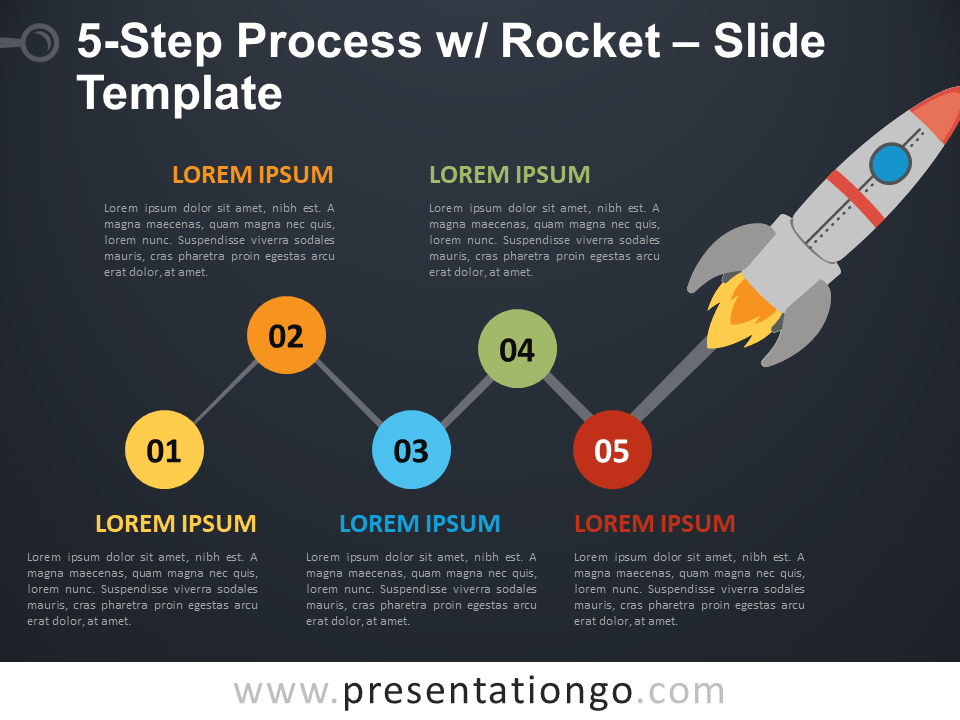

How to create a family rule system

Here is a sequence of steps that is important to use if you decide that words are not enough and your child still needs “boxes”. These steps minimize the possible negative consequences of punishment, and also allow you to negate the ignorance of the rules you set.

1. List

First make a list of the rules you would like your child to follow. Perhaps in the future you will want to supplement or make changes to them, but now outline the main ones.

2. Refinement

Specify your requirements. The child needs to be specific. For example:

Wrong : "Don't go out late."

Correct : Come home no later than 22.00.

Wrong : "Always be in touch."

Correct : “Call back every three hours. Call back after missed calls no later than 20 minutes later.

Your rules should be as clear as possible, because there are sanctions for non-compliance.

Wrong : "Don't skip school."

Correct : “Don't miss school without a good reason. Good reason agreed."

Decide what counts as absenteeism. For example, he left school because the last lesson was canceled - is this considered absenteeism? Agree on how to act in controversial situations and who has the final say. “I didn’t go to physical training because my knee hurt.” Was it necessary to call you and get consent for this pass? Or maybe you are a loyal parent and allow your grown child to miss five lessons a month without explaining the reasons. The point is to make your requirement as clear as possible.

3. Discussion

Discuss with your child each of your requirements, explain, try to find words, why it is so important to you. Be sincere about what worries you. Why do you want it to be like this and not otherwise. What other reasons are associated with this. For example, being at home after 22.00 is also a legal requirement for children under 16.

It is important that the child understands that this is not your “whim”. Although you have the right to "whim". Just like him. He wants coca and pizza on Saturdays (even though he knows it’s bad), and you want order in his room, dirty things in the laundry bin, because you feel bad when everything is a mess, and you don’t want to spend half a Saturday cleaning .

Listen to the child's opinion and be sure to make adjustments to the rules you suggested. Let it be a little, let it be in small things. But it is important for a teenager that his opinion is taken into account. There will be much more motivation to follow the established rules.

4. Sanctions

Set sanctions or penalties for breaking the rules. This item is important to compile with the child. It is better if the sanctions are differentiated (secondary violation is punished more severely). Use the “Imagine yourself in my place” technique more often: “What would you do if you were a parent? How would you behave in such a situation? What punishment did you apply?"

Stick to the agreements. For the psyche of a child, including a large one, it is very harmful when he is either punished for the same act or not.

For the psyche of a child, including a large one, it is very harmful when he is either punished for the same act or not.

5. Consent

Reread your set of rules together and get the child's agreement on each item. If it's more convenient, put plus signs at the end of each item (ideally three - both parents and a child). This is the most difficult and most important moment.

6. Rules for parents

For many parents, this step is unthinkable. And another part of the parents consider this "flirting with the child." But teenagers deserve that we reckon with their opinion, and not answer in the spirit of “this is my business”, “you don’t tell me”, “create your own family, and there you will command”. So this step is optional. But to an obstinate teenager, this approach seems more honest. Try it.

Ask the child what he strongly dislikes about your behavior. For example: entering a room without knocking, calling 10 times when he is with friends, smoking in the kitchen (or smoking at all!), promising and not fulfilling, excessive control, and so on. Include in the list the items that you yourself undertake to fulfill (with sanctions, of course).

Include in the list the items that you yourself undertake to fulfill (with sanctions, of course).

Why rules are not forever

There are tidy children who hate disorder, so they keep clean and tidy without any problems. And then there are parents who taught their children to clean up without reminders a long time ago, in the pre-adolescent period. These parents consider the lack of order to be a flaw in their negligent “colleagues”: they say, they shouldn’t have given up on education earlier, they should have worked on it every day. And now the child is not to blame for anything. This is what my friend Fyodor told me every time I complained to him about the mess in my children's rooms and complained that I couldn't force them to keep order. Fedor boasted about the order that was always in the rooms of his children when they were teenagers. And I felt guilty for the previous omissions in education, reproached myself for the weakness of character and inconsistency in the application of the promised punishments. Eh, I would return the time when, due to a cup of coffee or a pleasant chat with a friend, I was too lazy to check what was happening in the room of my son or daughter, and then I found them sleeping in the middle of chaos (and did not wake them up to get out). Yes, my husband and I are to blame.

Eh, I would return the time when, due to a cup of coffee or a pleasant chat with a friend, I was too lazy to check what was happening in the room of my son or daughter, and then I found them sleeping in the middle of chaos (and did not wake them up to get out). Yes, my husband and I are to blame.

And then one day Fyodor and I came to the apartment of his exemplary son, which he rented during an internship after graduation from the university. The son knew about dad's visit from yesterday evening. Nevertheless, the picture that appeared to our eyes impressed me, apparently in contrast to expectations: scattered clothes, chaotically arranged piles of books, magazines and papers, empty beer bottles everywhere, and in places tin cans mixed with worm socks and even ashtrays with cigarette butts! It must be said that Fedor himself is not manic, but a tidy man, and any woman would envy the order in his bachelor closet! The meeting between father and son was associated with the transfer of a spare car key and lasted 15-20 minutes. We drank coffee (for which my son had been looking for cups for a long time). The father did not ask, and the son did not even think of apologizing for "some mess." It was strange to me why he didn’t clean up at least superficially before the arrival of the pope, with whom he has a very close and trusting relationship.

We drank coffee (for which my son had been looking for cups for a long time). The father did not ask, and the son did not even think of apologizing for "some mess." It was strange to me why he didn’t clean up at least superficially before the arrival of the pope, with whom he has a very close and trusting relationship.

I confess that in my heart I was in a certain way jubilant. After all, Fedor constantly cited his children and his teaching gift as an example. To my question “why”, Fedor replied: “He probably likes it that way. He's already big, and that's his business." And I asked myself: how did Fyodor achieve order in the rooms of his children? Or did they just have great respect for their parents, so they obeyed their instructions? I did not draw any unambiguous conclusion from this story. But still, I thought that family rules, even if children follow them (as in the example described), are not always a guarantee that the behavior that parents want to achieve will take root and become part of an adult personality.