How much kids

How Many Children Should You Have?

Family

Zero? Three? Six? 2.1?

By Joe PinskerC. M. Bell / Library of Congress / Katie Martin / The AtlanticBryan Caplan is an economist and a dad who has thought a lot about the joys and stresses of being a parent. When I asked him whether there is an ideal number of children to have, from the perspective of parents’ well-being, he gave a perfectly sensible response: “I’m tempted to start with the evasive economist answer of ‘Well, there’s an optimal number given your preferences.’”

When I pressed him, he was willing to play along: “If you have a typical level of American enjoyment of children and you’re willing to actually adjust your parenting to the evidence on what matters, then I’ll say the right answer is four.”

Four does happen to be the number of children Caplan himself has. But he has a rationale for why that number might apply more generally. His interpretation of the research on parenting, which he outlines in his 2011 book, Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids, is that many of the time- and money-intensive things that parents do in hopes of helping their children succeed—loading them up with extracurriculars, sending them to private school—don’t actually contribute much to their future earnings or happiness.

In other words, many parents make parenting unnecessarily dreadful, so maybe, Caplan suggests, they should revisit their child-rearing approach and then, if they can afford to, consider having more kids, because kids can be fun and fulfilling. No sophisticated math brought him to the number four. “It’s just based upon my sense of how much people intrinsically like kids compared to how much needless suffering they’re doing,” he said. Caplan even suspects that more than four would be optimal for him.

The prompt I gave to Caplan, of course, has no single correct response. There are multiple, sometimes conflicting, ways of evaluating the question of how many kids is best for one family: from the perspective of parents, of children, and of society. These various lines of inquiry warrant a tour of what’s known, and what isn’t, about how the size of a family shapes the lives of its members.

These various lines of inquiry warrant a tour of what’s known, and what isn’t, about how the size of a family shapes the lives of its members.

* * *

A handful of studies have tried to pinpoint a number of children that maximizes parents’ happiness. One study from the mid-2000s indicated that a second child or a third didn’t make parents happier. “If you want to maximize your subjective well-being, you should stop at one child,” the study’s author told Psychology Today. A more recent study, from Europe, found that two was the magic number; having more children didn’t bring parents more joy.

In the United States, nearly half of adults consider two to be the ideal number of children, according to Gallup polls, with three as the next most popular option, preferred by 26 percent. Two is the favorite across Europe, too.

Ashley Larsen Gibby, a Ph.D. student in sociology and demography at Penn State, notes that these numbers come with some disclaimers. “While a lot of [the] evidence points to two children being optimal, I would be hesitant to make that claim or generalize it past Western populations,” she wrote to me in an email. “Having the ‘normative’ number of children is likely met with more support both socially and institutionally. Therefore, perhaps two is optimal in places where two is considered the norm. However, if the norm changed, I think the answer to your question would change as well.”

“While a lot of [the] evidence points to two children being optimal, I would be hesitant to make that claim or generalize it past Western populations,” she wrote to me in an email. “Having the ‘normative’ number of children is likely met with more support both socially and institutionally. Therefore, perhaps two is optimal in places where two is considered the norm. However, if the norm changed, I think the answer to your question would change as well.”

The two-child ideal is a major departure from half a century ago: In 1957, only 20 percent of Americans said the ideal family meant two or fewer children, while 71 percent said it meant three or more. The economy seems to have played some role in this shift. Steven Mintz, a historian at the University of Texas at Austin and the author of Huck’s Raft: A History of American Childhood, says that the ideal during the Baby Boom was in the neighborhood of three, four, or five children. “That number plummeted as the cost of rearing children rose and as more women entered the workforce and felt a growing sense of frustration about being reduced to childbearing machines,” he said.

The costs of raising children are not just financial. “As a parent who prizes his own mental and physical health,” says Robert Crosnoe, a sociology professor who is also at the University of Texas at Austin, “I had to stop at two, because this new style of intensive parenting that people feel they have to follow these days really wears one out.” (He added: “I am glad, however, that my parents did not think this way, as I am the third of three.”)

At the same time, having only one kid means parents miss out on the opportunity to have at least one boy and one girl—an arrangement they have tended to prefer for half a century, if not longer. (Couples are generally more likely to stop having children once they have one of each.) Maybe this is another reason two is such a popular number—though in the long run, one researcher found that having all girls or all boys doesn’t meaningfully affect the happiness of mothers who wanted at least one of each. (This researcher didn’t look at dads’ preferences. )

)

But plenty of people want more or fewer than two kids. In general, the experts I consulted agreed that the optimal number of children is specific to each family’s desires and constraints. “When a couple feels like they have more interest in kids; more energy for kids; maybe more support, like grandparents in the area; and a decent income, then having a large family can be the best option for them,” says Brad Wilcox, the director of the University of Virginia’s National Marriage Project. “And when a couple has fewer resources, either emotional, social, or financial, then having a smaller family would be best for them.”

What happens when there’s a gap between parents’ desires and reality? Per the General Social Survey, in 2018, 40 percent of American women ages 43 to 52 had had fewer children than what they considered ideal. “Part of the story here is that women are having children later in life, compared to much of human history, and they’re getting married later in life as well,” Wilcox says. “So those two things mean that at the end of the day, a fair number of women end up having fewer kids than they would like to, or they end up having no kids when they hoped to have children.”

“So those two things mean that at the end of the day, a fair number of women end up having fewer kids than they would like to, or they end up having no kids when they hoped to have children.”

Though the root causes can differ, this mismatch between hope and actuality is seen worldwide, and appears to make women measurably less happy. So while people’s ideal family size may vary—and is highly individualized—they’ll probably be happiest if they hit their target, whatever it may be.

* * *

Perhaps the most meaningful difference isn’t a matter of going from one to two children, or two to three, but from zero to one—from nonparent to parent.

“Having just one child [makes] various aspects of adults’ lives—how time, money, emotion, and mind are used and how new social networks are formed—child-centered,” says Kei Nomaguchi, a sociologist at Bowling Green State University. “If you want to enjoy adult-centered life, love expensive leisure activities, cherish intimate relationships with your partner, and both you and your partner want to devote your time to your careers, zero kids would be the ultimate. ”

”

Mothers, of course, stand to lose more than fathers when they have kids in their household. Having children is more stressful for women than it is for men, and mothers suffer professionally after having children in a way that fathers don’t (though parents’ happiness does seem to vary based on their country’s policies about paid leave and child care). In these regards, too, zero is good.

Whether the optimal number of children is greater than zero is a question many researchers have tried to address, and the sum of their work points to a range of variables that seem to matter.

One recent paper suggested that becoming a parent does indeed make people happier, as long as they can afford it. And a 2014 review of existing research, whose authors were skeptical of “overgeneralizations that most parents are miserable or that most parents are joyful,” detected other broad patterns: Being a parent tends to be a less positive experience for mothers and people who are young, single, or have young children. And it tends to be more positive for fathers and people who are married or who became parents later in life.

And it tends to be more positive for fathers and people who are married or who became parents later in life.

What’s optimal, then, depends on age, life stage, and family makeup—in other words, things that are subject to change. While being the parent of a young child may not seem to maximize happiness, parenthood may be more enjoyable years down the line.

Indeed, Bryan Caplan believes that when people think about having children, they tend to dwell on the early years of parenting—the stress and the sleep deprivation—but undervalue what family life will be like when their children are, say, 25 or 50. His advice to those who suspect they might be unhappy without grandchildren someday: “Well, there’s something you can do right now in order to reduce the risk of that, which is just have more kids.”

* * *

Parents may decide that a certain number of children is going to maximize their happiness, but what about the happiness of the children themselves? Is there an optimal number of siblings to have?

Generally speaking, as much as brothers and sisters bicker, relationships between siblings tend to be positive ones. In fact, there’s evidence that having siblings improves young children’s social skills, and that good relationships between adult siblings in older age are tied to better health. (One study even found a correlation between having siblings and a reduced risk of getting a divorce—the idea being that growing up with siblings might give people social toolkits that they can use later in life.)

In fact, there’s evidence that having siblings improves young children’s social skills, and that good relationships between adult siblings in older age are tied to better health. (One study even found a correlation between having siblings and a reduced risk of getting a divorce—the idea being that growing up with siblings might give people social toolkits that they can use later in life.)

There is, however, at least one less salutary outcome: The more siblings one has, the less education one is likely to get. Researchers have for decades discussed whether “resource dilution” might be at play—the idea that when parents have to divvy up their resources among more children, each child gets less. Under this framework, going from having zero siblings to having one would be the most damaging, from a child’s perspective—his or her claim to the household’s resources shrinks by half.

But this theory doesn’t really hold up, not least because children with one sibling tend to go further in school than only children. “Resource dilution is attractive because it’s intuitive and parsimonious—it explains a lot with a simple explanation—but it’s probably too simple,” says Douglas Downey, a sociologist at Ohio State University. “Many parental resources are probably not finite in the way the theory describes.”

“Resource dilution is attractive because it’s intuitive and parsimonious—it explains a lot with a simple explanation—but it’s probably too simple,” says Douglas Downey, a sociologist at Ohio State University. “Many parental resources are probably not finite in the way the theory describes.”

A small example: Parents can read books to two children at once—this doesn’t “dilute” their limited time. A larger one: Instead of splitting up a fixed pile of cash, parents might start saving differently if they know they’re going to pay two kids’ college tuitions instead of one’s. “They put a bigger proportion of their money toward kids’ education and less toward new golf clubs,” Downey explains.

And if parents are enmeshed in a strong community that helps them raise their kids, they have more resources than just their own to rely on. In a 2016 study, Downey and two other researchers found that the negative correlation between “sibship size” and educational outcomes was three times as strong in Protestant families as in Mormon ones, which often take a more communal approach to raising children. “When child development is shared more broadly with nonparents, sibship size matters less,” Downey and his fellow researchers wrote.

“When child development is shared more broadly with nonparents, sibship size matters less,” Downey and his fellow researchers wrote.

The gender mix of siblings can be a factor too. “In places with strong preferences for sons over daughters, there is some evidence that girls with older sisters are the worst off in terms of parental investments (e.g. school fees, medical care, maybe even food/nutrition),” Sarah Hayford, a colleague of Downey’s at Ohio State, noted in an email.

Siblings, then, can be a mixed bag. It’s probably folly to try to game out just how many kids will give each one the best life. But Caplan has a simple theory for how to optimize children’s happiness: “The most important thing in your life is your parents deciding to have you in the first place. Each kid is another person that gets to be alive and will be very likely to be glad to be alive.”

* * *

Thinking about what’s best for any individual household is more subjective and nuanced than what number of kids would be best for the broader society. When it comes to ensuring that a given society’s population is steady in the long run, demographers don’t just have a number (an average of 2.1 births per woman, roughly) but a name for it: “replacement-level fertility.”

When it comes to ensuring that a given society’s population is steady in the long run, demographers don’t just have a number (an average of 2.1 births per woman, roughly) but a name for it: “replacement-level fertility.”

Sometimes, populations deviate from this replacement-level rate in a way that stresses out demographers. “Nothing guarantees that the number of children that is good for me is also good for the society,” said Mikko Myrskylä, the executive director of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, in Rostock, Germany.

“Very low fertility,” Myrskylä wrote in an email, “creates a situation in which over time the share of working-age population compared to the elderly population becomes small, and this may present a challenge for social arrangements such as the social security system.” Japan’s population, for instance, has been shrinking in the past decade, and its growing elderly population and low fertility rate (1.43 births per woman) have its government worried about the sustainability of its workforce and social-benefits programs.

“Very high fertility,” Myrskylä continued, “in particular when mortality is low, creates a rapidly growing population, which requires expansion in the infrastructure and consumes increasingly large amounts of resources.” In Nigeria, the government has attempted to lower its high fertility rate by increasing access to contraceptives and touting the economic advantages of smaller family units.

But families don’t base their desire for children on a society’s optimal number. In many countries in central and West Africa—such as Senegal, Mali, and Cameroon—the desired family size for many young women is four to six children, says John Casterline, a demographer at Ohio State who has conducted research in the region. This number has stayed relatively high even as people have attained higher average levels of education—a shift that, in Asia and Latin America, for instance, is usually accompanied by a shrinking of the hoped-for size of families.

It’s not entirely clear why women’s expectations in these parts of the world haven’t changed as those of women in other regions have. One guess, Casterline says, has to do with how family is conceptualized. “A lot of things in life are perceived as a collective endeavor of a large extended kin group, for the sharing of resources and labor, so that diminishes the personal cost of having a kid,” he told me. “It’s diffused among a larger group of people.” For example, maybe one child is particularly sharp, so his relatives save up to send him to college—“a sort of corporate collective effort,” as Casterline put it—and hope that he gets a high-paying urban job and can help support them.

One guess, Casterline says, has to do with how family is conceptualized. “A lot of things in life are perceived as a collective endeavor of a large extended kin group, for the sharing of resources and labor, so that diminishes the personal cost of having a kid,” he told me. “It’s diffused among a larger group of people.” For example, maybe one child is particularly sharp, so his relatives save up to send him to college—“a sort of corporate collective effort,” as Casterline put it—and hope that he gets a high-paying urban job and can help support them.

Another possibility: “There was always the issue of protecting yourself against mortality,” Casterline said, referring to the possibility that a child might not make it into adulthood. He said that child mortality rates in many parts of the world have declined a lot in the past few decades. But they’re still high, and the impulse to hedge against them might linger. “‘How many babies do I need to have now if I’d like to have three adult children in 30 years?’” says Jenny Trinitapoli of the University of Chicago, describing the thought process. “That depends on the mortality rates.”

“That depends on the mortality rates.”

But these explanations aren’t definitive. Some hard-to-quantify preferences also seem to be playing a role. Casterline remembered conducting surveys in Egypt a decade or so ago, and listening to Egyptians discuss the merits of having three children versus two. “There was some indifference, but there was a real feeling that it’s more of a family—it feels better—to have three children rather than two, because so much of their social life is family gatherings, and having aunts and uncles and cousins,” he says. “And if you have three kids, you get a lot more of that.”

But as the economy and makeup of a society changes, so do people’s preferences, and in that sense, the United States is a telling example. At the beginning of the 19th century, the typical married woman had seven to 10 children, but by the beginning of the 20th, that number had fallen to three. Why? “Children were no longer economic assets who could be put to work,” says Mintz, the historian of childhood.

And some aspects of society are designed to work best for families of a certain size—a standard car in America, for instance, comfortably fits four people. (Mintz notes that in the ‘50s and ‘60s, sedans could seat six, because they typically had bench seats and lacked a center console.) Hotels, too, come to mind: Once a family has more people than can fit in two double beds, it’s time to consider booking another room.

After accounting for what a given society is like, and what a given household within that society is like, one could very well determine the optimal number of children to have. But those considerations are less compelling and more clinical when compared with the joy people have when they see a child hold his baby sister for the first time; attend an enormous, rowdy family reunion; or plan a blissful getaway without having to worry about who will watch the children. Those are the moments that feel truly optimal.

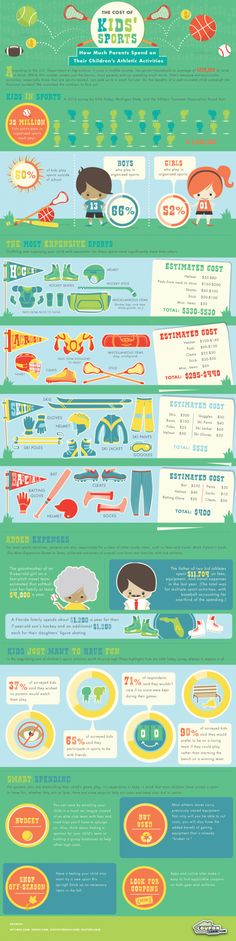

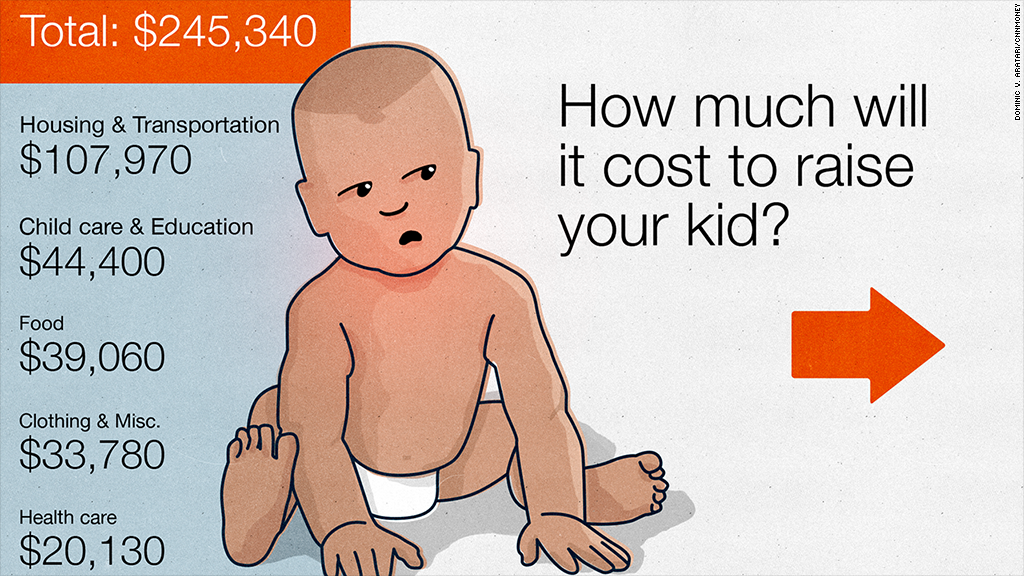

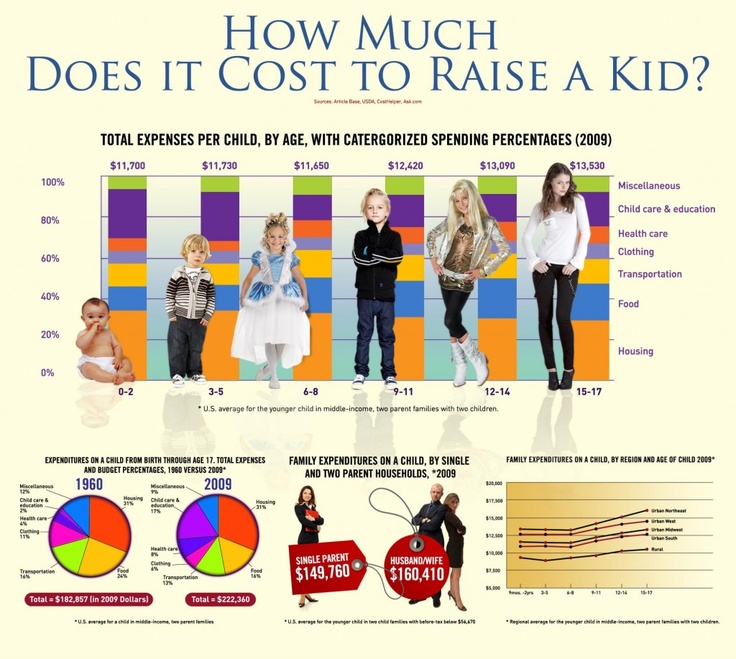

The Cost of Raising a Child

Posted by Mark Lino, Economist at the Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion in Food and Nutrition

Feb 18, 2020

Families Projected to Spend an Average of $233,610 Raising a Child Born in 2015.

USDA recently issued Expenditures on Children by Families, 2015. This report is also known as “The Cost of Raising a Child.” USDA has been tracking the cost of raising a child since 1960 and this analysis examines expenses by age of child, household income, budgetary component, and region of the country.

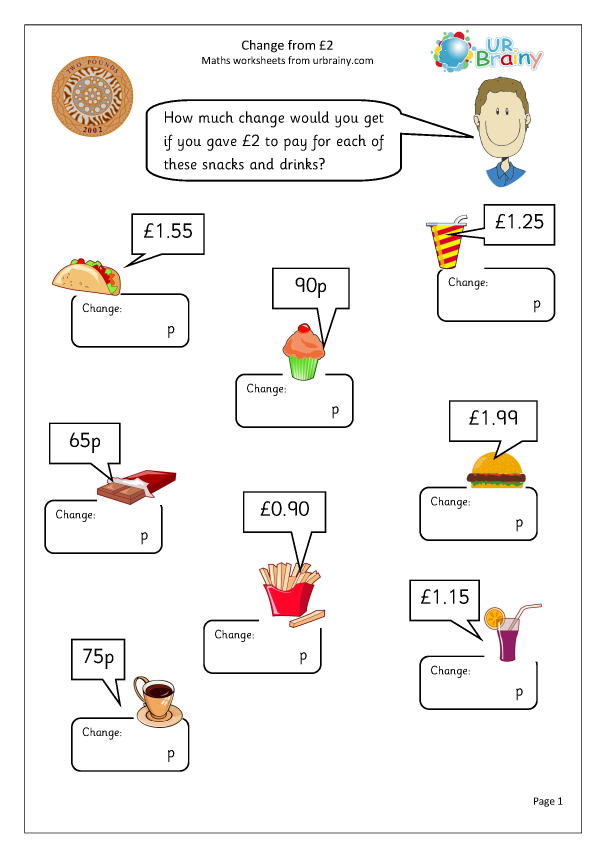

Based on the most recent data from the Consumer Expenditures Survey, in 2015, a family will spend approximately $12,980 annually per child in a middle-income ($59,200-$107,400), two-child, married-couple family. Middle-income, married-couple parents of a child born in 2015 may expect to spend $233,610 ($284,570 if projected inflation costs are factored in*) for food, shelter, and other necessities to raise a child through age 17. This does not include the cost of a college education.

Where does the money go? For a middle-income family, housing accounts for the largest share at 29% of total child-rearing costs. Food is second at 18%, and child care/education (for those with the expense) is third at 16%. Expenses vary depending on the age of the child.

Expenses vary depending on the age of the child.

We did the analysis by household income level, age of the child, and region of residence. Not surprising, the higher a family’s income the more was spent on a child, particularly for child care/education and miscellaneous expenses.

Expenses also increase as a child ages. Overall annual expenses averaged about $300 less for children from birth to 2 years old, and averaged $900 more for teenagers between 15-17 years of age. Teenagers have higher food costs as well as higher transportation costs as these are the years they start to drive so insurance is included or a maybe a second car is purchased for them.

Regional variation was also observed. Families in the urban Northeast spent the most on a child, followed by families in the urban West, urban South, and urban Midwest. Families in rural areas throughout the country spent the least on a child—child-rearing expenses were 27% lower in rural areas than the urban Northeast, primarily due to lower housing and child care/education expenses.

Child-rearing expenses are subject to economies of scale. That is, with each additional child, expenses on each declines. For married-couple families with one child, expenses averaged 27% more per child than expenses in a two-child family. For families with three or more children, per child expenses averaged 24% less on each child than on a child in a two-child family. This is sometimes referred to as the “cheaper by the dozen” effect. Each additional child costs less because children can share a bedroom; a family can buy food in larger, more economical quantities; clothing and toys can be handed down; and older children can often babysit younger ones.

Food costs have decreased over the years thanks to increased efficiency in American agriculture.This report is one of many ways that USDA works to support American families through our programs and work. It outlines typical spending by families from across the country, and is used in a number of ways to help support and education American families. Courts and state governments use this data to inform their decisions about child support guidelines and foster care payments. Financial planners use the information to provide advice to their clients, and families can access our Cost of Raising a Child calculator, which we update with every report on our website, to look at spending patterns for families similar to theirs. This Calculator is one of many tools available on MyMoney.gov, a government research and data clearinghouse related to financial education.

Courts and state governments use this data to inform their decisions about child support guidelines and foster care payments. Financial planners use the information to provide advice to their clients, and families can access our Cost of Raising a Child calculator, which we update with every report on our website, to look at spending patterns for families similar to theirs. This Calculator is one of many tools available on MyMoney.gov, a government research and data clearinghouse related to financial education.

This year we released the report at a time when families are thinking about their plans for the New Year. We’ve been focusing on nutrition-related New Year’s resolutions – or what we are referring to as Real Solutions - on our MyPlate website, ChooseMyPlate.gov. This report and the updated calculator can help families as they focus on financial health resolutions. This report will provide families with a greater awareness of the expenses they are likely to face while raising children.

In addition to the report and the calculator, we also have a dedicated section on ChooseMyPlate.gov that provides tips and tools to aid families and individuals in making healthy choices while staying on a budget. For strategies beyond food, our friends at MyMoney.gov offer a wealth of information to help Americans plan for their financial future.

For more information on the Annual Report on Expenditures on Children by Families, also known as the cost of raising a child, go to: www.fns.usda.gov/resource/expenditures-children-families-reports-all-years.

*Projected inflationary costs are estimated to average 2.2 percent per year. This estimate is calculated by averaging the rate of inflation over the past 20 years.

Editor’s Note (March 8, 2017): The comparison of rural vs. urban northeast child care and education value has been updated.

Visit the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s MyMoney.gov for more resources to ensure financial well-being this New Year’s season!Category/Topic: Food and Nutrition

Tags: children choosemyplate. gov CNPP Cost of Raising a Child economics Expenditures on Children by Families Food and Nutrition mymoney.gov MyPlate Research

gov CNPP Cost of Raising a Child economics Expenditures on Children by Families Food and Nutrition mymoney.gov MyPlate Research

Write a Response

Comments

How many children do Russians have

Artem Ivolgin

not yet a father

Author profile

Sergey Antonov

already father

Author profile

Two-thirds of Russian families with children

Moreover, in recent years this figure has remained practically unchanged: according to the 2002 census, one child was brought up in 65.2% of families with children; 2010 census - 65. 5%. The Russians themselves, judging by opinion polls, say they plan to have more than one child. We looked at the statistics and found out why desires do not always coincide with reality.

5%. The Russians themselves, judging by opinion polls, say they plan to have more than one child. We looked at the statistics and found out why desires do not always coincide with reality.

How many children do Russians want to have

Once every five years, Rosstat conducts a large-scale survey of 15,000 families. Respondents are asked how many children they would like to have and how many they actually plan.

According to this study, 70% of Russian women aged 18-44 want to have two or three children. But when answering the question "How many children do you think you will have?" the share of those who answer that there will be one child grows by one and a half times - from 17 to 25%.

Simply put, women usually want two or three children, but when it comes not to dreams, but to reality, they say that they will most likely have one or two. Maybe they are just afraid to jinx it, or maybe they are afraid that the family will not pull it off financially. We will talk about this a little lower.

/podrostok-eto-dorogo/

“Spending is flying into space”: 5 reasons why spending on children is growing with them

Source: Sample observation of the reproductive plans of the population - 2017 Source: Sample observation of the reproductive plans of the population - 2017How much children are born by Russians

Accurate data on the number of children in Russian families appear only according to the results of the population census. The last one took place in 2021, and its final results will appear at best in 2023. But if you look at the results of the 2002 and 2010 censuses, you can see that the distribution of families by the number of children practically does not change.

| 2002 Census | 2010 Census | |

|---|---|---|

| Families with one child | 65.24% | 65.5% |

| Families with two children | 28.17% | 27.53% |

| Families with at least three children | 6. 55% 55% | 6.99% |

Families with one child

Census 2002

65.24%

Census 2010

65.5%

Families with two children

2002 Census

28.17%

Census 2010

27.53 %

Families with at least three children

2002 Census

6.55%

Census 2010

6.99%

We can assume that according to the results of the 2021 census, this ratio will remain approximately the same . The absolute values don't seem to have changed much either. This is evidenced by indirect calculations. During the 2010 census, 42 million families were counted in Russia, of which almost 24 million were with children. At that time, there were 7% of large families - this is 1.7 million. In 2021, according to the State Duma Committee on Health Protection, there were 1.6 million large families in the country.

Why fewer children are born than they would like

In 2020, VCIOM asked Russians why they are postponing the birth of a child. The main reason why those who do not have children do not have children is the lack of money. This was said by 39% of the respondents.

The main reason why those who do not have children do not have children is the lack of money. This was said by 39% of the respondents.

Respondents could indicate several answers, and in the top ten most common reasons, half are related to finances in one way or another. This is the lack of their own housing, the inability to combine work and raising children, and so on.

/baby-cost/

How much does a child cost in the first year

Barriers to having children: a survey of the childless

| 💲 - financial barriers | |

|---|---|

| 💲 Financial possibilities do not allow | 39% |

| 💲 Housing difficulties | 30% |

| No partner/partner | 29% |

| Too few years to have a baby | 15% |

| 💲 No conditions for child care | 14% |

| Haven't thought about it yet | 14% |

| 💲 I don't want to leave my job | 11% |

| I want to live for myself | 10% |

| 💲 It is difficult to arrange a child in kindergarten | 5% |

| Health does not allow | 4% |

| 💲 It's hard to combine work and childcare | 4% |

| Uncertain about the strength of the marriage/partnership | 4% |

| No hope for help from relatives | 3% |

| I don't like children | 2% |

| Partner does not want a child | 1% |

| Refusal to answer | 1% |

| Other | 14% |

💲 - Financial barriers

💲 Material capabilities do not allow

39%

💲 Housing difficulties

%

Lack of partner /partner 9000% 29%

Lessings for the birth of

15 15 15 15 %

💲 No conditions for childcare

14%

Haven't thought about it yet

14%

💲 I do not want to leave work

11%

I want to live for myself

10%

💲 It is difficult to arrange a child in kindergarten

5%

does not allow health

4%

💲 It is difficult to combine work and care For a child

4%

, are not sure of marriage/partnership strength

4%

There is no hope of helping relatives

3%

I do not like children

2%

Partner/partner does not want a child

1%

Refused to answer

1%

Other

14%

According to Rosstat, the main motive for women to have a second child is so that the first one does not feel lonely. The main reason to have a third child is so that the older children learn to take care of the younger ones.

The main reason to have a third child is so that the older children learn to take care of the younger ones.

Financial incentives, such as home improvements using maternity capital or monthly payments for families with multiple children, are not even among the top five answers.

/prava/matcapital/

Rights of parents with maternity capital

Unfortunately, nothing is known about the motivation of families with more than three children.

Women's motives for having a second child

| 💲 - financial incentives | |

|---|---|

| So that an existing child does not feel alone | 63% |

| Spouse/partner's desire to have a second child | 62% |

| I wanted the older child to learn to take care of the younger ones | 51% |

| Desire to strengthen the family | 50% |

| With two children, there are more guarantees that you will not be lonely in old age | 48% |

| The first child really wanted a brother or sister | 38% |

| I wanted to have a small child in the family again | 37% |

| Parents or spouse's parents had three or more children | 37% |

| 💲 Desire to solve housing problems using state support | 36% |

| Improving the standard of living of the family | 33% |

| Two children increase the authority of a person in society | 28% |

| There should be as many children as God wills | 22% |

| Pregnant and decided not to have an abortion | 22% |

| Many friends who knew three children did not want to be left behind | 18% |

💲 - financial incentives

so that the existing child does not feel lonely

63%

The desire of the spouse to have a second child

%

wanted the older child to learn to take care of the younger

51%

The desire to strengthen the family

50%

with two children more guarantees that in old age you will not remain alone

48%

The first child really wanted a brother or sister

38%

family of a small child

37%

Parents or spouse's parents had three or more children

37%

💲 Desire to solve housing problems using state support

36%

Raising the standard of living of the family

33%

Two children increase the authority of a person in society

28%

There should be as many children as God wills

22% did not have an abortion and 903

22%

Many friends who knew three children did not want to be left behind

18%

Motives for having a third child

| 💲 — financial incentives | |

|---|---|

| For older children to learn to take care of younger ones | 54% |

| More guarantees that you will not be lonely in old age | 50% |

| Spouse/partner's desire to have a third child | 48% |

| I wanted to have a small child in the family again | 47% |

| Desire to have a child of a different sex if the first two are of the same sex | 47% |

| Desire to strengthen the family | 47% |

| 💲 Desire to solve housing problems using state support | 44% |

| 💲 Financial assistance from the state | 41% |

| 💲 Monthly payment up to the age of three | 40% |

| Three children will be able to help more around the house in the future | 40% |

| Improving the standard of living of the family | 36% |

| There should be as many children as God wills | 28% |

| Three children increase the authority of a person in society | 25% |

| Pregnant and decided not to have an abortion | 25% |

| Parents or spouse's parents had three or more children | 24% |

| Many friends who knew three children did not want to be left behind | 13% |

💲 - financial incentives

To learn to take care of the younger

54%

more guarantees, that you will not remain alone

50%

Partner's desire to have a third child

48 %

I wanted to have a small child in the family again

47%

Desire to have a child of the opposite sex, if the first two are of the same sex

47%

Desire to strengthen the family

47%

💲 Desire to solve housing problems using state support

47% Financial assistance from the state

41%

💲 Monthly payment up to the age of three

40%

Three children in the future will be able to help more around the house

40%

Improving the standard of living of the family

36%

children should be as much as God will give

28%

three children increase the authority of a person in society

25%

Pregnancy and decided not to abort

25%

in parents or from parents or from parents or in parents spouse's parents had three or more children

24%

Many friends who knew three children did not want to be left behind

13%

Source: Selective observation of the reproductive plans of the population — 2017

How maternity capital affected fertility

Nevertheless, about 45% of women say that maternity capital helped them decide to have a second or third child. The mother capital program for the second and subsequent children was introduced in 2007. From that moment, the birth rate of second children began to grow - until 2016.

The mother capital program for the second and subsequent children was introduced in 2007. From that moment, the birth rate of second children began to grow - until 2016.

Demographer Aleksey Raksha believes that the change in the situation in 2016 is also related to maternity capital: “The turn to a decrease in the birth rate took place in 2016, from September, exactly nine months after the announcement of the first extension of the maternity capital program, because in 2015 there was ambiguity with the extension of the program, and many rushed to have second children.”

It turns out that in 2007-2015, the average family was in a hurry to have a second or third child, since it was not clear how long the maternity capital program would last. The birth rate was on the rise. Then the program was extended - now it is known that it will be valid until at least 2026. But the amount of maternity capital almost stopped growing: in five years, from 2015 to 2019, the amount was indexed by only 3%, while inflation over this period was 31%. The Russians are no longer in a hurry to have children.

The Russians are no longer in a hurry to have children.

In 2020, the maternity capital program was extended to the first children. Perhaps this is due to the sharp decline in the birth rate of first-borns, which has been observed since 2017. Why this happens is unclear. How payments for the first child affected fertility is also still unknown: accurate demographic data for 2021 will not appear until the second half of 2022.

So what? 02/21/20

Maternal capital for the first child: who will receive it and how much money will be given

Sources: Consultant Plus, Russian Birth and Death Database Sources: Consultant Plus, Russian Birth and Death DatabaseHow many children should be in a family for happiness: answers

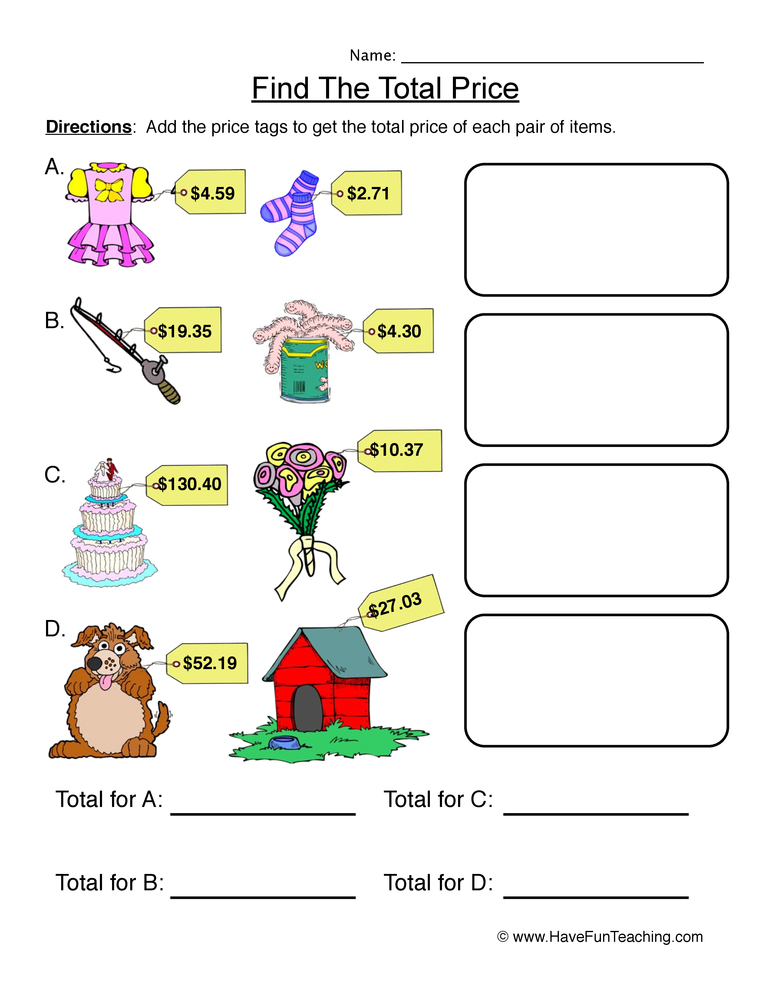

You and your loved one already have a son or daughter, and you are increasingly thinking about a second child, and the baby is already asking for a “brother or sister”. How many children should be in an ideal family?

Website editor

Tags:

A family

Children

Getty Images

How many children does it take to be happy

Do not self-medicate! In our articles, we collect the latest scientific data and the opinions of authoritative health experts. But remember: only a doctor can diagnose and prescribe treatment.

But remember: only a doctor can diagnose and prescribe treatment.

Family without children

This type of family is much more common today than before. Sometimes, of course, this may be due to medical problems, but more often this state of affairs suits the spouses, and they consciously decide not to have children. Whether this is good or bad for them is hard to say. However, it is definitely better for a child if people who do not want to have children do not do this solely out of a sense of false shame or out of a desire to be like everyone else.

Family with one child

This is the most common type of family today, especially in big cities. As a rule, parents who consciously support such a family structure say that their decision depends solely on material reasons. They believe that it is better to provide well for one baby than to give a bad base to several. Often, children who do not have siblings receive a better education, live in a separate room from the first years of life, and receive more parental attention than their peers from large families.

Often, children who do not have siblings receive a better education, live in a separate room from the first years of life, and receive more parental attention than their peers from large families.

An only child in a family is, as a rule, a child on whom too many parental expectations are imposed, a lot is required of him, he is taught a lot, he is brought up too correctly. And, as a rule, there are many adults for him alone - after all, very often for grandparents, he is the only grandson. Try not to overburden your only son or daughter. Do not forget that a child should have a childhood, and he will still have time to become a professor.

Family with two children

This type of family is quite common. As a rule, parents decide on a second child, based on a common stereotype - "there should be two children in a family - a boy and a girl." The situation when the first-born has a brother or sister can have a positive impact on the development of the child. Just do not delay with the addition: it is believed that the ideal difference between children should not exceed 5 years. It is much more logical when the kids grow up together, play and help each other, than when one of them is already an adult and independent.

Just do not delay with the addition: it is believed that the ideal difference between children should not exceed 5 years. It is much more logical when the kids grow up together, play and help each other, than when one of them is already an adult and independent.

Sometimes in a family with two children, there is a rather rigid consolidation of the roles of "younger" - "older", which remains in adulthood, influencing the specifics of building relationships. Try not to use only the older child as an example, the younger one should also feel its importance. At the same time, do not spoil the younger one. This can cause the elder to feel jealous.

Often a situation arises when two children in a family are divided into "mother's" and "dad's", which also cannot but leave a certain imprint on them. Try to avoid such mistakes in education, and then you can be sure that both your kids will grow up prosperous and happy.0003

Family with three children

The appearance of a third child in a family most often mitigates the disadvantages inherent in families with two children, therefore, from the point of view of child psychology, families with three or more babies are the most prosperous. However, in such a situation, completely different questions come to the fore. Can the family provide the proper level of education and life for children? Indeed, in the life of kids there is not only clothes and food, for which in most cases there is enough money, but also education, additional activities and hobbies (sometimes not cheap), cultural life (cinema, theaters) and other expenses. 12 things that only parents with many children will understand.

However, in such a situation, completely different questions come to the fore. Can the family provide the proper level of education and life for children? Indeed, in the life of kids there is not only clothes and food, for which in most cases there is enough money, but also education, additional activities and hobbies (sometimes not cheap), cultural life (cinema, theaters) and other expenses. 12 things that only parents with many children will understand.

If the appearance of a third child in a family seriously worsens the living conditions of the family as a whole and of the two children already growing up in it, then all psychological advantages come to naught.

Which is better?

How many children do you need to be happy? This question, like many other questions regarding family planning, does not and cannot have an unequivocal answer. We all have different living conditions, different attitudes towards children, different own childhood experiences. After all, very often people, when talking about how many children they would like to have in their family, proceed from their own childhood memories.

After all, very often people, when talking about how many children they would like to have in their family, proceed from their own childhood memories.

“I was alone, and I felt bad,” says an adult and decides that there will be several children in his family so that none of them will be bored and lonely, as he himself was. “I had a younger sister, and only she got all the attention of the parents, I don’t want this for my child” - and only one child appears in the family. “I want to do everything right, and therefore I will have three children, because it is good for them,” the third parent will say. And each of them will be right in their own way.

From the point of view of sociologists and other specialists dealing with demographic problems, in order for a nation not to die out, a family should have three children - one instead of a mother, a second instead of a father, and a third - to increase the population. But this is from the point of view of the state, and only you can decide what is best for your family.