How long does each stage of grief last

Grief And Bereavement | How Long Is The Grieving Process?

What are grief, mourning, and bereavement?

Grief

Grief is normal, and it is a process. Expressing grief is how a person reacts to the loss of a loved one.

Many people think of grief as a single instance or as a short time of pain or sadness in response to a loss – like the tears shed at a loved one’s funeral. But grieving includes the entire emotional process of coping with a loss, and it can last a long time. The process involves many different emotions, actions, and expressions, all of which help a person come to terms with the loss of a loved one.

We may hear the time of grief being described as "normal grieving," but this simply refers to a process anyone may go through, and none of us experiences grief the same way. This is because grief doesn’t look or feel the same for everyone. And every loss is different.

Mourning

Mourning often goes along with grief. While grief is a personal experience and process, mourning is how grief and loss are shown in public. Mourning may involve religious beliefs or rituals, and may be affected by our ethnic background and cultural customs. The rituals of mourning − seeing friends and family and preparing for the funeral and burial or final physical separation − often give some structure to the grieving process. Sometimes a sense of numbness lasts through these activities, leaving the person feeling as though they are just “going through the motions” of these rituals.

Bereavement

Grief and mourning happen during a period of time called bereavement. Bereavement refers to the time when a person experiences sadness after losing a loved one.

How long does the grieving process last?

Since each person grieves differently, the length and intensity of the emotions people go through varies from person to person. Grieving is painful, and it’s important that those who have suffered a loss be allowed the time they need to express their grief.

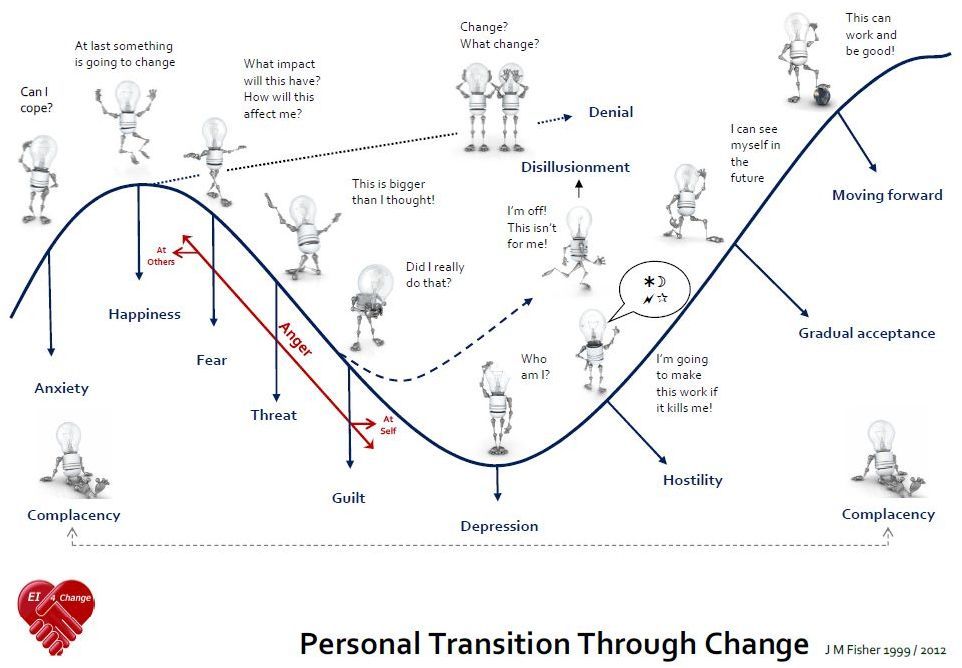

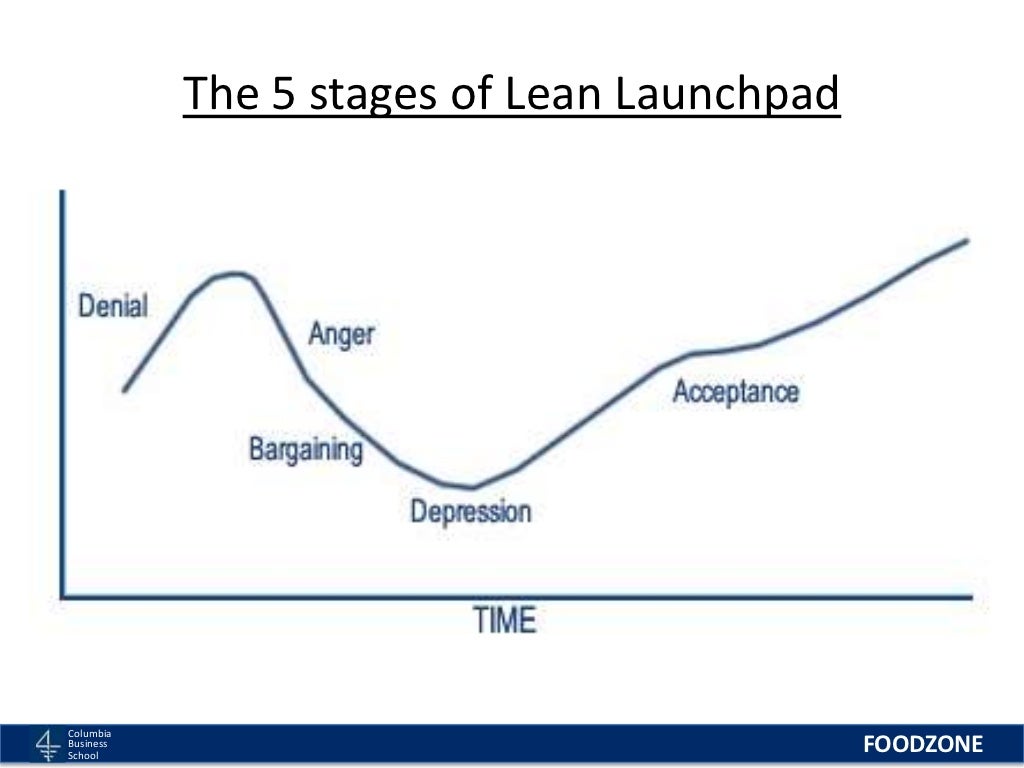

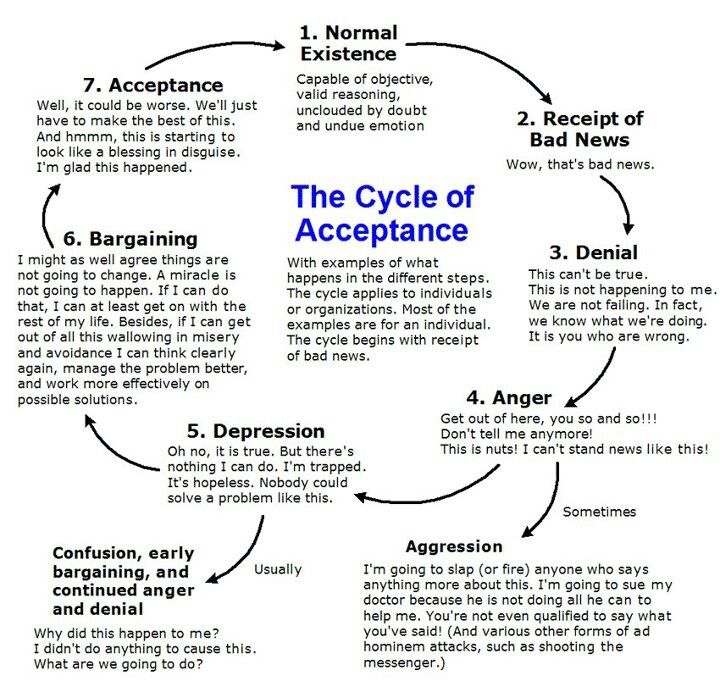

Although grief is described in phases or stages, it may feel more like a roller coaster, with ups and downs. This can make it hard for the bereaved person to feel any sense of progress in dealing with the loss. A person may feel better for a while, only to become sad again. Sometimes, people wonder how long the grieving process will last, and when they can expect some relief. There’s no answer to this question, but some of the factors that affect the intensity and length of grieving are:

- Your relationship with the person who died

- The circumstances of their death

- Your own life experiences

It’s common for the grief process to take a year or longer. A grieving person must resolve the emotional and life changes that come with the death of a loved one. The pain may become less intense, but it’s normal to feel emotionally involved with the deceased for many years. In time, the person should be able to use their emotional energy in other ways and to strengthen other relationships.

Grief can take unexpected forms

Difficult relationships with the deceased prior to death can cause unique grieving experiences for loved ones. In addition, prolonged illnesses can also cause grief to take unexpected forms.

Difficult relationships

A person who had a difficult relationship with the deceased (a parent who was abusive, estranged, or abandoned the family, for example) is often surprised by the painful emotions they have after their death. It’s not uncommon to have profound distress as the bereaved mourns the relationship they had wished for with the person who died, and lets go of any chance of achieving it.

Others might feel relief, while some may wonder why they feel nothing at all at the death of such a person. Regret and guilt are common, too. This is all a normal part of the process of adjusting and letting go.

Grief after long illness

The grief experience may be different when the loss occurs after a long illness rather than suddenly. When someone is terminally ill, family, friends, and even the patient might start to grieve in response to the expectation of death. This is a normal response called anticipatory grief. It can help people complete unfinished business and prepare loved ones for the actual loss, but it might not lessen the pain they feel when the person dies.

When someone is terminally ill, family, friends, and even the patient might start to grieve in response to the expectation of death. This is a normal response called anticipatory grief. It can help people complete unfinished business and prepare loved ones for the actual loss, but it might not lessen the pain they feel when the person dies.

Many people think they are prepared for the loss because death is expected. But when their loved one actually dies, it can still be a shock and bring about unexpected feelings of sadness and loss. For most people, the actual death starts the normal grieving process.

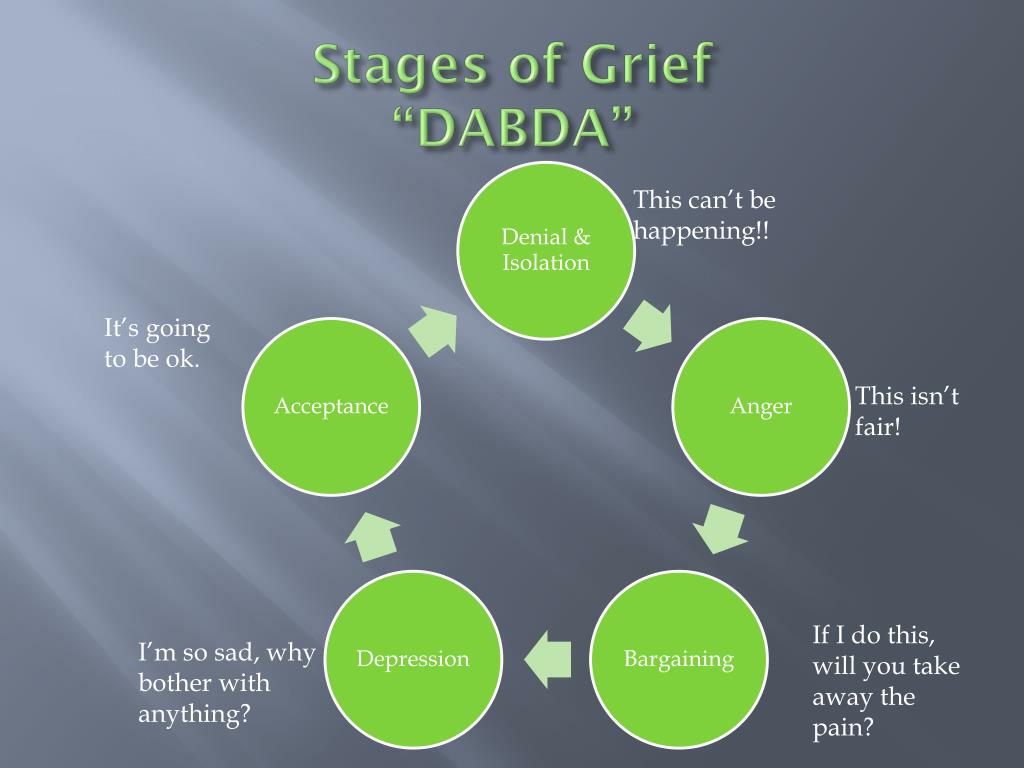

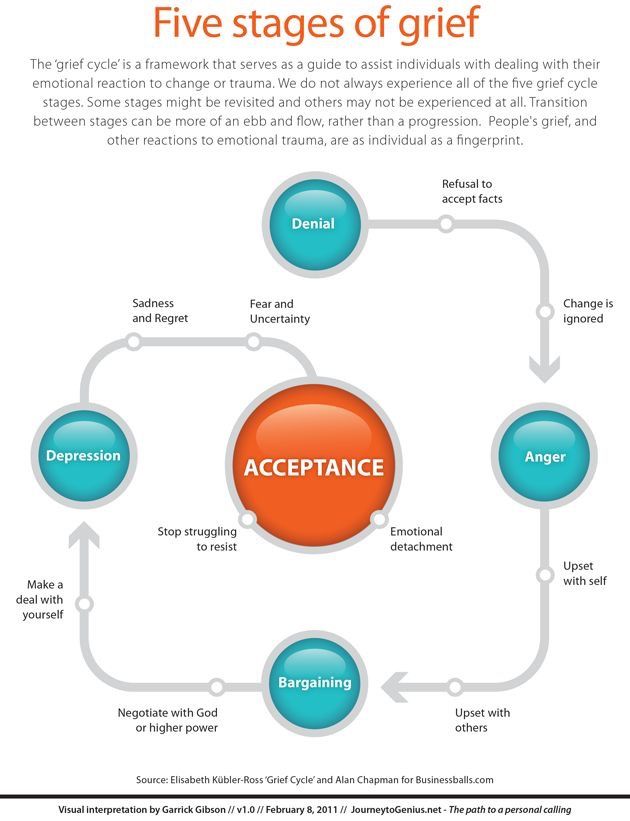

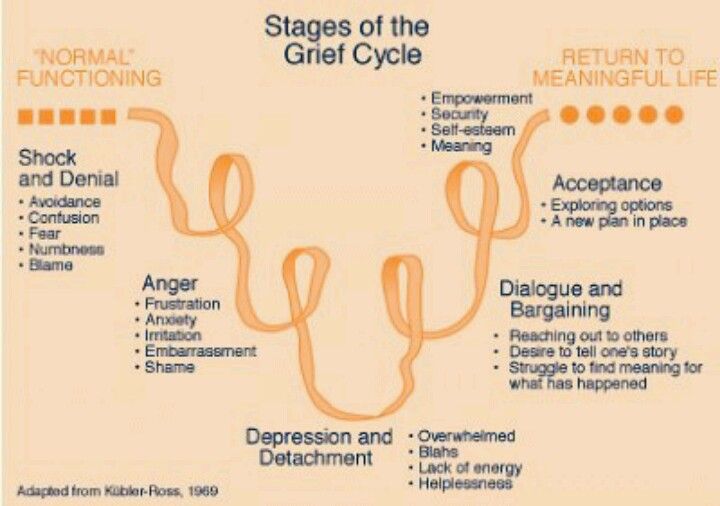

Stages of grief

People may go through many different emotional states while grieving. And in advanced cancer, the grieving process and stages often start before the loss of a loved one because of anticipatory grief.

Researchers describe grief in stages, but it's important to know that each person moves through the stages differently and at a different pace. Some may go through the stages just as they are described below, and other people may move back and forth between stages. Some people may get stuck in one stage and have trouble reaching the final stage of the grief process.

Some may go through the stages just as they are described below, and other people may move back and forth between stages. Some people may get stuck in one stage and have trouble reaching the final stage of the grief process.

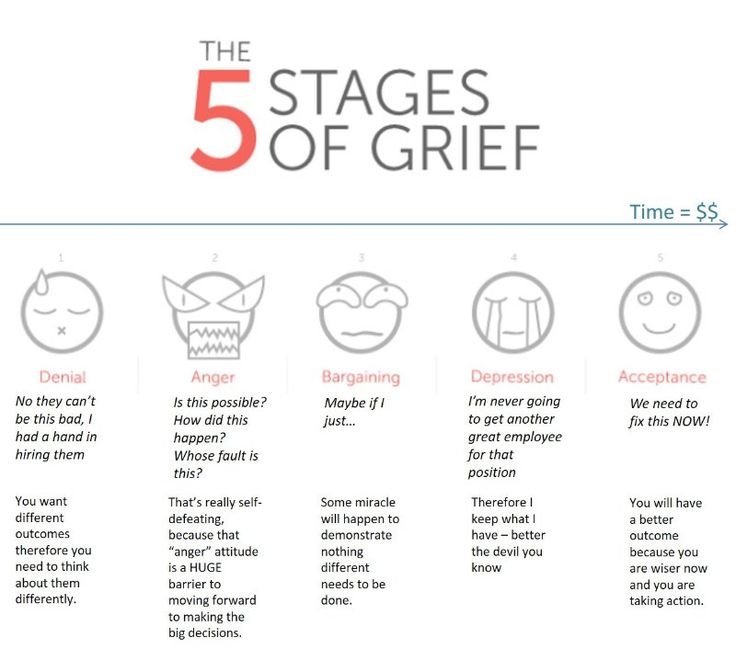

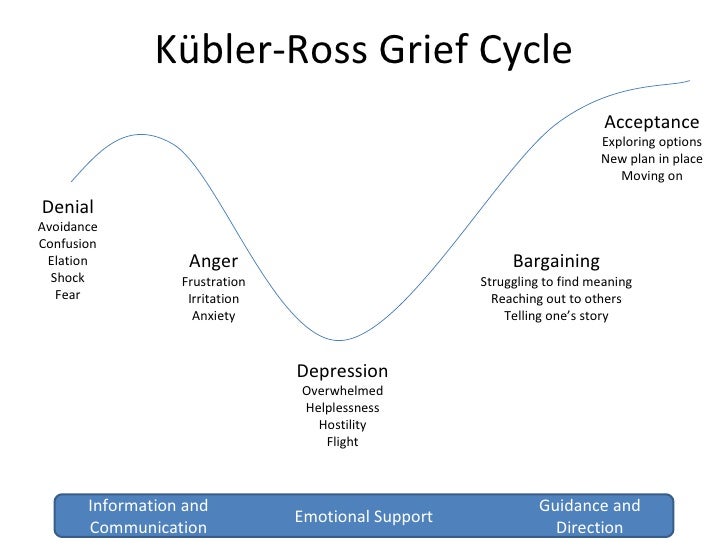

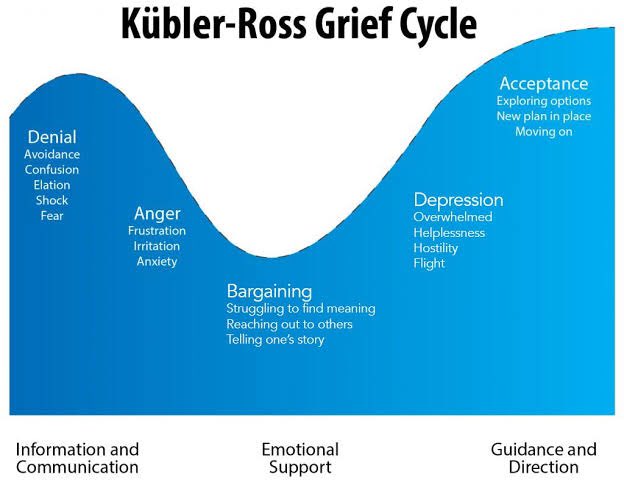

Experts describe 5 stages that are usually experienced by adults during the grief process.

- Denial and isolation - This first stage may start before the loss occurs if the death of the loved one is expected. Or it may begin immediately at the time or shortly after the loss. It can last anywhere from a few hours to days or weeks. The feelings experienced in the first stage of grief may be fear, shock, or numbness. The person may be have pangs of distress, often triggered by reminders of the deceased. During this time, the bereaved person may feel emotionally “shut off” from the world. The grieving person may avoid others or avoid talking about the loss.

- Anger - The next stage can last for days, weeks, or months.

It is when the earliest feelings are replaced by frustration and anxiety. This stage can involve anger, loneliness, or uncertainty. It may be when the feelings of loss are most intense and painful. The person may feel agitated or weak, cry, engage in aimless or disorganized activities, or be preoccupied with thoughts or images of the person they lost.

It is when the earliest feelings are replaced by frustration and anxiety. This stage can involve anger, loneliness, or uncertainty. It may be when the feelings of loss are most intense and painful. The person may feel agitated or weak, cry, engage in aimless or disorganized activities, or be preoccupied with thoughts or images of the person they lost. - Bargaining - This stage is likely to be shorter than others. It happens when a grieving person is struggling to find meaning for the loss of their loved one. They may reach out to others and tell their story. In doing so, they may begin to think more clearly about the changes brought about by the loss of their loved one.

- Depression - As life changes are realized, depression may set in. This stage is used to describe a grieving person who feels overwhelmed and helpless. They may withdraw, become hostile, or express extreme sadness. During this time, grief tends to come in waves of distress.

- Acceptance - This last phase of grief happens when people find ways to come to terms with and accept the loss. Usually, the person comes to accept the loss slowly over a few months to a year. This acceptance includes adjusting to daily life without the deceased.

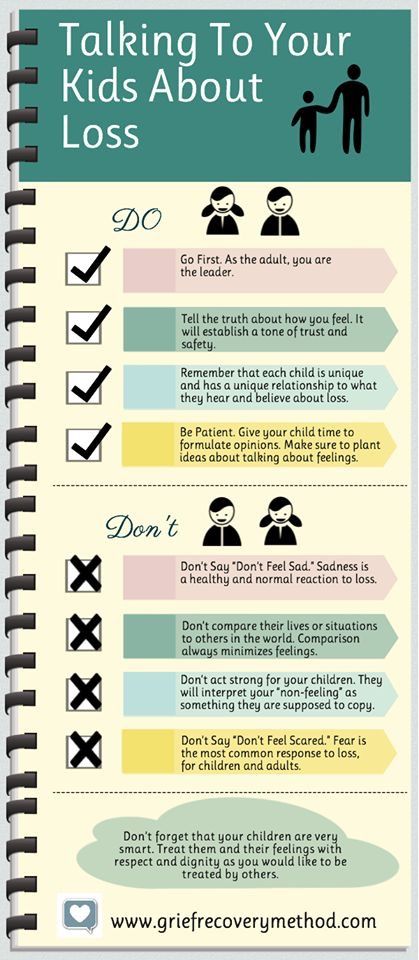

Children grieve, too, but the process may look different from adults. To learn more about this, see Helping Children When a Family Member Has Cancer.

Some or all of the following may be seen in a person who is grieving:

- Socially withdrawing

- Trouble thinking and concentrating

- Becomes restless and anxious at times

- Loss of appetite

- Looks sad

- Feels depressed

- Dreams of the deceased (or even have hallucinations or “visions” in which they briefly hear or see the deceased)

- Loses weight

- Trouble sleeping

- Feels tired or weak

- Becomes preoccupied with death or events surrounding death

- Searches for reasons for the loss (sometimes with results that make no sense to others)

- Dwells on mistakes, real or imagined, that they made with the deceased

- Feels guilty for the loss

- Feels all alone and distant from others

- Expresses anger or envy at seeing others with their loved ones

Reaching the acceptance stage and adjusting to the loss does not mean that all the pain is over. Grieving for someone who was close to you includes losing the future you expected with that person. This must also be mourned. The sense of loss can last for decades. For example, years after a parent dies, the bereaved may be reminded of the parent’s absence at an event they would have been expected to attend. This can bring back strong emotions, and require mourning yet another part of the loss.

Grieving for someone who was close to you includes losing the future you expected with that person. This must also be mourned. The sense of loss can last for decades. For example, years after a parent dies, the bereaved may be reminded of the parent’s absence at an event they would have been expected to attend. This can bring back strong emotions, and require mourning yet another part of the loss.

How to Understand Your Feelings

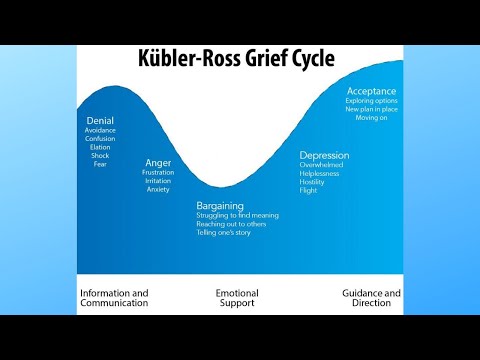

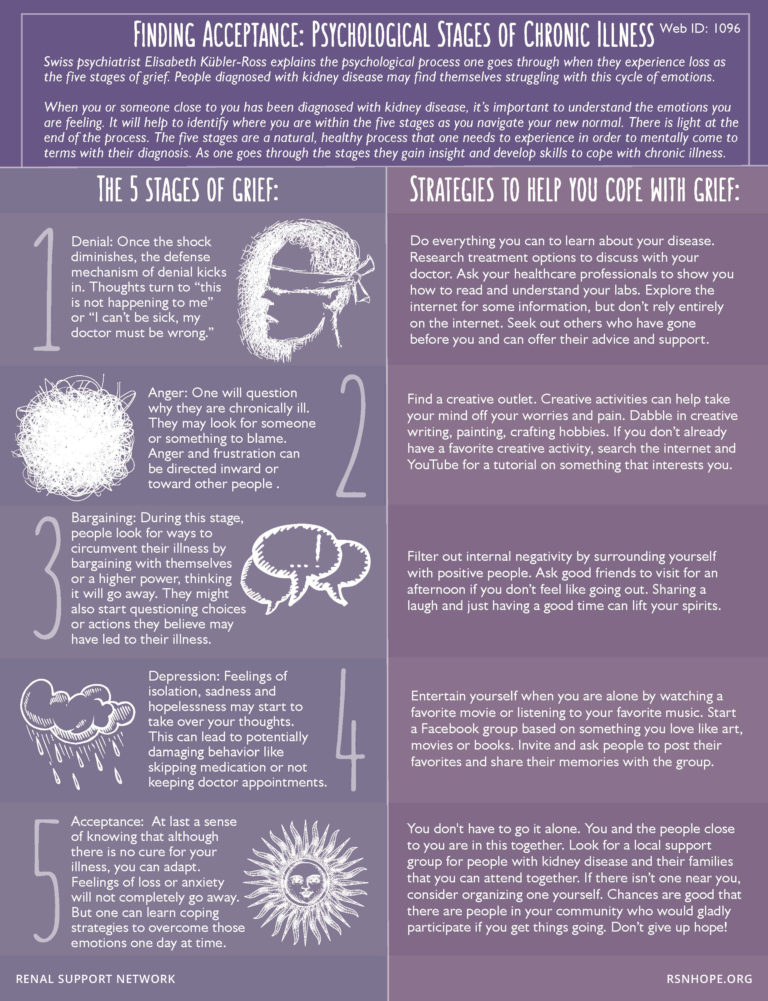

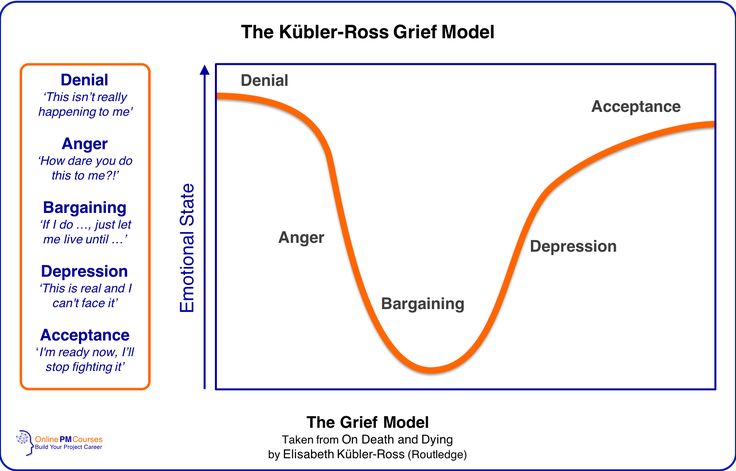

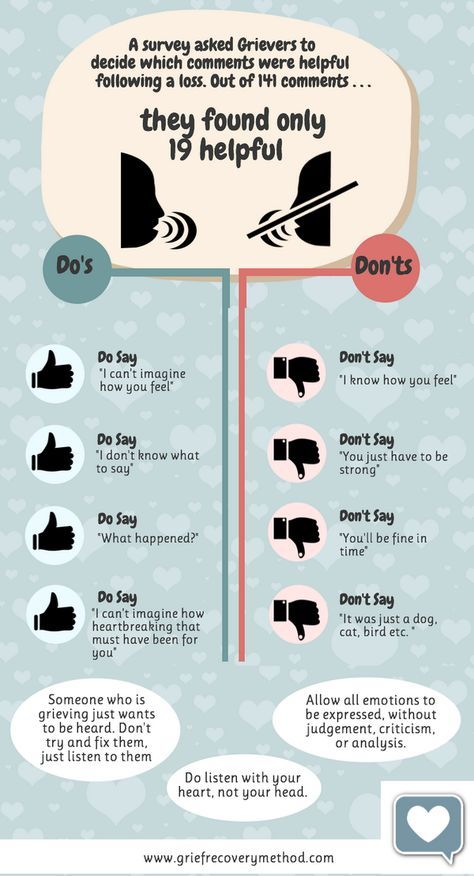

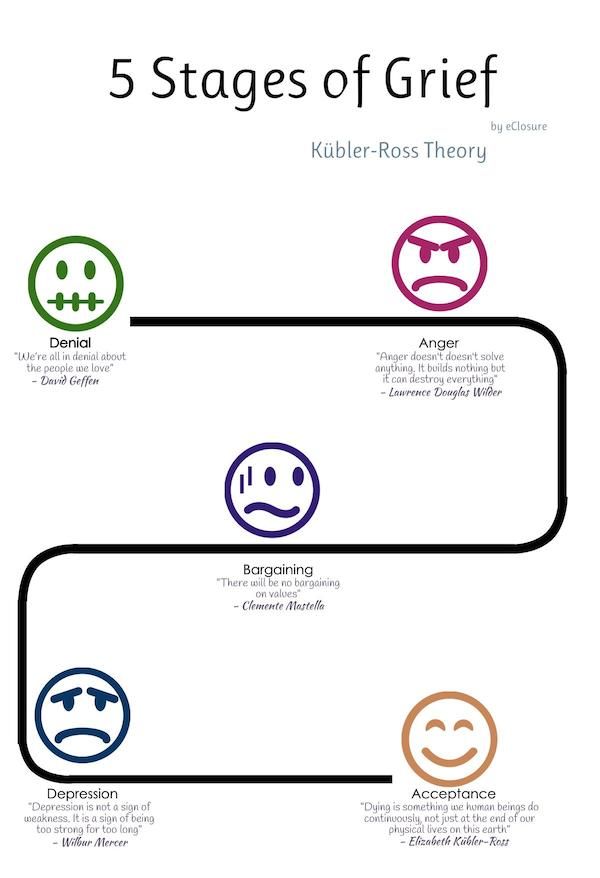

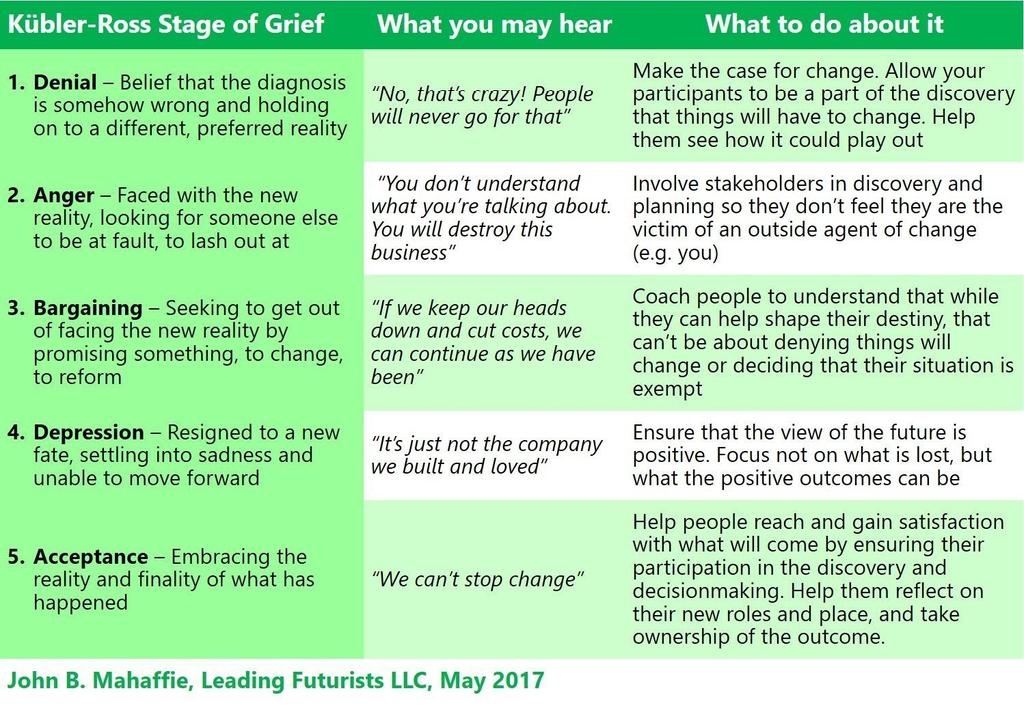

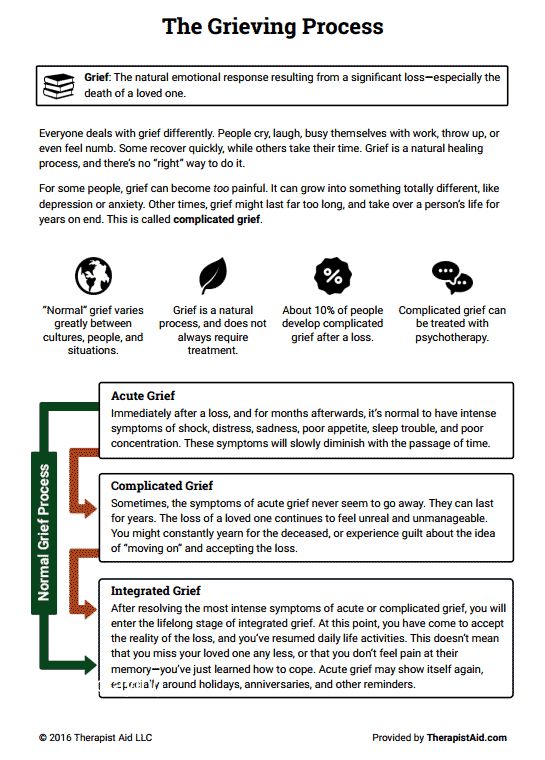

Grief is universal. At some point, everyone will have at least one encounter with grief. Elizabeth Kbler Ross wrote in her book “On Death and Dying” that grief could be divided into five stages. They were originally devised for people who were ill, but these stages have been adapted for coping with grief in general.

Grief is universal. At some point, everyone will have at least one encounter with grief. It may be from the death of a loved one, the loss of a job, the end of a relationship, or any other change that alters life as you know it.

Grief is also very personal. It’s not very neat or linear. It doesn’t follow any timelines or schedules. You may cry, become angry, withdraw, or feel empty. None of these things are unusual or wrong.

It’s not very neat or linear. It doesn’t follow any timelines or schedules. You may cry, become angry, withdraw, or feel empty. None of these things are unusual or wrong.

Everyone grieves differently, but there are some commonalities in the stages and the order of feelings experienced during grief.

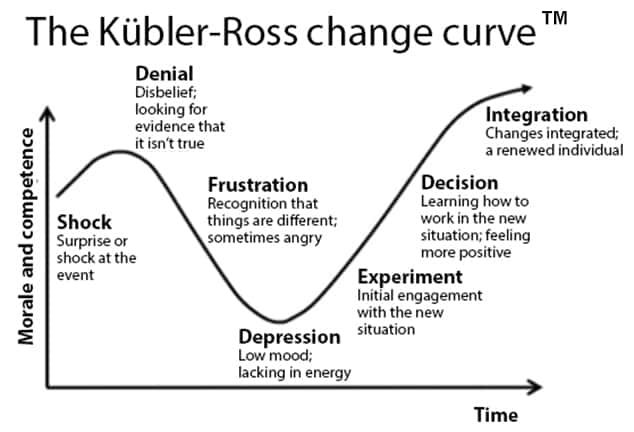

In 1969, a Swiss-American psychiatrist named Elizabeth Kübler-Ross wrote in her book “On Death and Dying” that grief could be divided into five stages. Her observations came from years of working with terminally ill individuals.

Her theory of grief became known as the Kübler-Ross model. While it was originally devised for people who were ill, these stages of grief have been adapted for other experiences with loss, too.

The five stages of grief may be the most widely known, but it’s far from the only popular stages of grief theory. Several others exist as well, including ones with seven stages and ones with just two.

According to Kübler-Ross, the five stages of grief are:

- denial

- anger

- bargaining

- depression

- acceptance

Here’s what to know about each one.

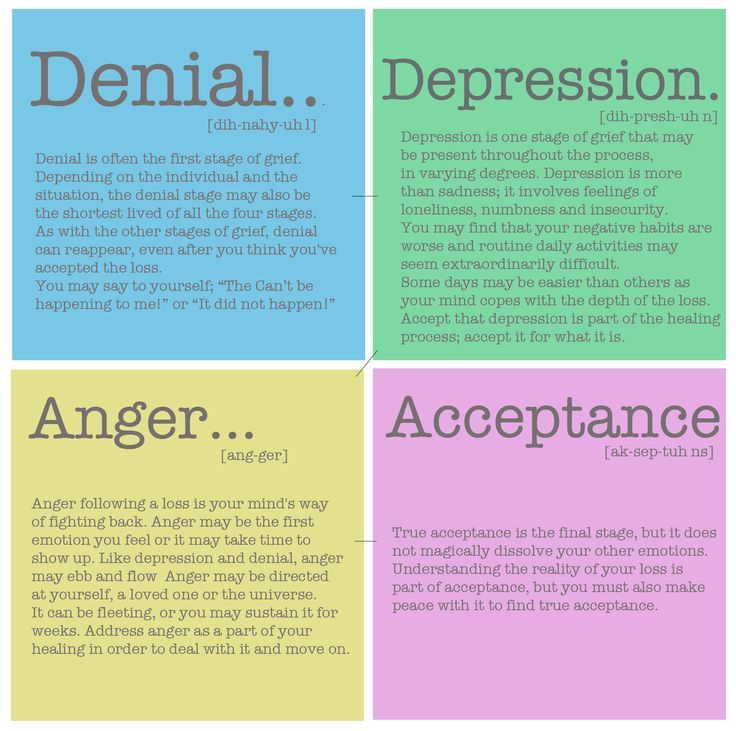

Stage 1: Denial

Grief is an overwhelming emotion. It’s not unusual to respond to the strong and often sudden feelings by pretending the loss or change isn’t happening.

Denying it gives you time to more gradually absorb the news and begin to process it. This is a common defense mechanism and helps numb you to the intensity of the situation.

As you move out of the denial stage, however, the emotions you’ve been hiding will begin to rise. You’ll be confronted with a lot of sorrow you’ve denied. That is also part of the journey of grief, but it can be difficult.

Examples of the denial stage

- Breakup or divorce: “They’re just upset. This will be over tomorrow.”

- Job loss: “They were mistaken. They’ll call tomorrow to say they need me.”

- Death of a loved one: “She’s not gone. She’ll come around the corner any second.”

- Terminal illness diagnosis: “This isn’t happening to me.

The results are wrong.”

The results are wrong.”

Stage 2: Anger

Where denial may be considered a coping mechanism, anger is a masking effect. Anger is hiding many of the emotions and pain that you carry.

This anger may be redirected at other people, such as the person who died, your ex, or your old boss. You may even aim your anger at inanimate objects. While your rational brain knows the object of your anger isn’t to blame, your feelings in that moment are too intense to act according to that.

Anger may mask itself in feelings like bitterness or resentment. It may not be clear-cut fury or rage.

Not everyone will experience this stage of grief. Others may linger here. As the anger subsides, however, you may begin to think more rationally about what’s happening and feel the emotions you’ve been pushing aside.

Examples of the anger stage

- Breakup or divorce: “I hate him! He’ll regret leaving me!”

- Job loss: “They’re terrible bosses.

I hope they fail.”

I hope they fail.” - Death of a loved one: “If she cared for herself more, this wouldn’t have happened.”

- Terminal illness diagnosis: “Where is God in this? How dare God let this happen!”

Stage 3: Bargaining

During grief, you may feel vulnerable and helpless. In those moments of intense emotions, it’s not uncommon to look for ways to regain control or to want to feel like you can affect the outcome of an event. In the bargaining stage of grief, you may find yourself creating a lot of “what if” and “if only” statements.

It’s also not uncommon for religious individuals to try to make a deal or promise to God or a higher power in return for healing or relief from the grief and pain. Bargaining is a line of defense against the emotions of grief. It helps you postpone the sadness, confusion, or hurt.

Examples of the bargaining stage

- Breakup or divorce: “If only I had spent more time with her, she would have stayed.

”

” - Job loss: “If only I worked more weekends, they would have seen how valuable I am.”

- Death of a loved one: “If only I had called her that night, she wouldn’t be gone.”

- Terminal illness diagnosis: “If only we had gone to the doctor sooner, we could have stopped this.”

Stage 4: Depression

Whereas anger and bargaining can feel very active, depression may feel like a quiet stage of grief.

In the early stages of loss, you may be running from the emotions, trying to stay a step ahead of them. By this point, however, you may be able to embrace and work through them in a more healthful manner. You may also choose to isolate yourself from others in order to fully cope with the loss.

That doesn’t mean, however, that depression is easy or well defined. Like the other stages of grief, depression can be difficult and messy. It can feel overwhelming. You may feel foggy, heavy, and confused.

Depression may feel like the inevitable landing point of any loss. However, if you feel stuck here or can’t seem to move past this stage of grief, you can talk with a mental health expert. A therapist can help you work through this period of coping.

However, if you feel stuck here or can’t seem to move past this stage of grief, you can talk with a mental health expert. A therapist can help you work through this period of coping.

Examples of the depression stage

- Breakup or divorce: “Why go on at all?”

- Job loss: “I don’t know how to go forward from here.”

- Death of a loved one: “What am I without her?”

- Terminal illness diagnosis: “My whole life comes to this terrible end.”

Stage 5: Acceptance

Acceptance is not necessarily a happy or uplifting stage of grief. It doesn’t mean you’ve moved past the grief or loss. It does, however, mean that you’ve accepted it and have come to understand what it means in your life now.

You may feel very different in this stage. That’s entirely expected. You’ve had a major change in your life, and that upends the way you feel about many things.

Look to acceptance as a way to see that there may be more good days than bad. There may still be bad — and that’s OK.

There may still be bad — and that’s OK.

Examples of the acceptance stage

- Breakup or divorce: “Ultimately, this was a healthy choice for me.”

- Job loss: “I’ll be able to find a way forward from here and can start a new path.”

- Death of a loved one: “I am so fortunate to have had so many wonderful years with him, and he will always be in my memories.”

- Terminal illness diagnosis: “I have the opportunity to tie things up and make sure I get to do what I want in these final weeks and months.”

The seven stages of grief are another popular model for explaining the many complicated experiences of loss. These seven stages include:

- Shock and denial: This is a state of disbelief and numbed feelings.

- Pain and guilt: You may feel that the loss is unbearable and that you’re making other people’s lives harder because of your feelings and needs.

- Anger and bargaining: You may lash out, telling God or a higher power that you’ll do anything they ask if they’ll only grant you relief from these feelings or this situation.

- Depression: This may be a period of isolation and loneliness during which you process and reflect on the loss.

- The upward turn: At this point, the stages of grief like anger and pain have died down, and you’re left in a more calm and relaxed state.

- Reconstruction and working through: You can begin to put pieces of your life back together and move forward.

- Acceptance and hope: This is a very gradual acceptance of the new way of life and a feeling of possibility for the future.

As an example, this may be the presentation of stages from a breakup or divorce:

- Shock and denial: “She absolutely wouldn’t do this to me. She’ll realize she’s wrong and be back here tomorrow.

”

” - Pain and guilt: “How could she do this to me? How selfish is she? How did I mess this up?”

- Anger and bargaining: “If she’ll give me another chance, I’ll be a better boyfriend. I’ll dote on her and give her everything she asks.”

- Depression: “I’ll never have another relationship. I’m doomed to fail everyone.”

- The upward turn: “The end was hard, but there could be a place in the future where I could see myself in another relationship.”

- Reconstruction and working through: “I need to evaluate that relationship and learn from my mistakes.”

- Acceptance and hope: “I have a lot to offer another person. I just have to meet them.”

There’s no one stage that’s universally considered to be the hardest to endure. Grief is a very individual experience. The toughest stage of grief varies from person to person and even from situation to situation.

Grief is different for every person. There’s no exact time frame to adhere to. You may remain in one of the stages of grief for months but skip other stages entirely.

This is typical. It takes time to go through the grieving process.

Not everyone goes through the stages of grief in a linear way. You may have ups and downs and go from one stage to another, then circle back.

Additionally, not everyone will experience all stages of grief, and you may not go through them in order. For example, you may begin coping with loss in the bargaining stage and find yourself in anger or denial next.

Avoiding, ignoring, or denying yourself the ability to express your grief may help you dissociate from the pain of the loss you’re going through. But holding it in won’t make it disappear. And you can’t avoid grief forever.

Over time, unresolved grief can turn into physical or emotional manifestations that affect your health.

In order to heal from a loss and move on, you have to address it. If you’re having trouble processing grief, consider seeking out counseling to help you through it.

If you’re having trouble processing grief, consider seeking out counseling to help you through it.

Grief is a natural emotion to experience when going through a loss.

While everyone experiences grief differently, identifying the various stages of grief can help you anticipate and comprehend some of the reactions you may experience throughout the grieving process. It can also help you understand your needs when grieving and find ways to have them met.

Understanding the grieving process can ultimately help you work toward acceptance and healing.

The key to understanding grief is realizing that no one experiences the same thing. Grief is very personal, and you may feel something different every time. You may need several weeks, or grief may be years long.

If you decide you need help coping with the feelings and changes, a mental health professional is a good resource for vetting your feelings and finding a sense of assurance in these very heavy and weighty emotions.

These resources can be useful:

- Depression Hotline

- Suicide Prevention Lifeline

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization

Five stages of grief - truth or myth?

- Claudia Hammond

- BBC Future

Denial, anger, compromise, depression and acceptance. Is it true that a person experiencing the pain of loss goes through certain stages? Let's look at the research data.

image copyrightMilan Popovic / Unsplash

"Tosca is a place we don't know until we visit it ourselves. We realize that loved ones can die, but we don't know exactly what awaits us in the first days and weeks after losses".

These are the words of the American writer Joan Didion, who described her feelings in the first year after the death of her husband in an extremely emotional confession "The Year of Magical Thinking".

The theory of five stages of grief - denial, anger, compromise, depression and acceptance - is firmly rooted in popular culture.

Articles are written about her and remembered in serials, and the artist Damien Hirst created a series of paintings, calling them the acronym "DABDA" (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance).

How long each stage lasts is not specified, but it is believed that all of them must pass in a certain sequence.

- Regular exercise saves you from depression. But not always

- How hormones, immunity, microbes, and pulse affect our character

- How parents' fights affect children's health studied the disposition of children to parents) and Colin Murray-Parks.

Researchers interviewed 22 widows and identified four stages of grief: numbness, searching and longing, depression and rethinking.

The current classification was developed by psychologist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, who worked with terminally ill patients and asked about their near-death experiences.

Kübler-Ross, by the way, radically changed the attitude towards palliative care and raised the question of the doctor's responsibility not only for the health of patients, but also for how they live their last days.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,How does a terminally ill person feel?

Skip the podkast

Podkast

Scho TS BULO

GOLOVNA TIZHNYA, Yaku explain our journalism

VIPSISKS

, as a system of system, as a systematic audit, as a systematic audit, as a systematic check, as a systematic check, as a systematic audit, as a systematic check In the early 2000s, Yale University researchers first took up this topic.

Over the course of three years, they interviewed 233 bereaved people (usually a wife or husband). The interviews were conducted approximately six, eleven and nineteen months after death.

The researchers did not look at cases of violent death of a relative or complex grief reactions.

The picture they got was more complex than the five-stage hypothesis. The researchers found that the most common emotion was acceptance, while denial was not experienced by everyone or to the same extent.

The second strong emotion was longing, and a depressed state accompanied all stages, and it was more pronounced than anger.

In addition, the emotional stages did not change each other in a clear sequence. A person in the third stage of grief could, for example, experience acceptance rather than anger.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,A popular theory is that when we experience grief, we go through five successive stages.

Longing for the deceased can last for years, but in the end, most people cope with grief.

For ethical reasons, the first interviews were conducted only a month after death, and therefore the researchers did not have an accurate picture of what a person feels in the first days and weeks after the loss.

Later, a study of people's reactions to violent death was conducted, but its participants were mainly students who lost more distant relatives than their spouse.

A strict sequence of stages was also not confirmed, although acute mental pain was more characteristic of the first stage, and acceptance - the last. However, unlike in the previous study, the scientists did not follow the reactions of one person over a long period of time.

Another study found that older people experience loss differently.

George Bonanno of Columbia University observed elderly couples before and after the death of one of their spouses. He found that 45% of people did not feel severe pain either immediately after the death of their other half, or later.

10% of widowers and widowers even felt some relief. People showed resilience and were able to cope with grief.

Bonanno's latest study in 2012 also disproved the idea of stages of grief.

However, whatever the results of the research, the theory of five stages of grief is attractive in a certain sense, because it gives people hope for gradual relief.

Ruth David Koenigsberg, author of The Truth About Grief, notes that the five-stage theory makes people feel certain things.

"It calms those who have similar emotions, but makes those who experience the death of loved ones differently feel guilty," Koenigsberg writes.

Image copyright, Unsplash

Image caption,Everyone experiences loss in their own way

"A person may think that something is wrong with him, that he does not feel what he should feel," the author adds.

However, research clearly shows that there is simply no "correct" way to mourn a loved one. Everyone experiences grief differently, and that's natural.

The feeling of loss remains, but the longing goes away with time, at least for most people.

Some "scenario" of what you will experience next can be somewhat reassuring, but, unfortunately, real experience often differs from theory.

After all, life is much more complicated.

The purpose of the article is general information. It cannot replace the medical advice of a specialist. The BBC is not responsible for any diagnosis made reader based on information from the site. The BBC is not responsible for the content of any external Internet sites linked to by the authors of the article, nor does it endorse any commercial product or service mentioned on on on any site. Always consult your doctor if you have questions related to your health.

You can read the original of this article in English on the website BBC Future .

Follow our news on Twitter and Telegram

Work of grief - Pro Palliative

Psychologist Larisa Pyzhyanova herself experienced the loss of loved ones and, working in the Ministry of Emergency Situations, hundreds of times helped people whose relatives died suddenly and tragically.

We publish an excerpt from her book “Sharing the pain. The experience of a psychologist from the Ministry of Emergency Situations, which is useful to everyone, ”which tells about what the work of grief is, what processes and why a person experiences after the death of a loved one, how long it can last, what is considered the norm, and what should alert.

We publish an excerpt from her book “Sharing the pain. The experience of a psychologist from the Ministry of Emergency Situations, which is useful to everyone, ”which tells about what the work of grief is, what processes and why a person experiences after the death of a loved one, how long it can last, what is considered the norm, and what should alert. The book can be bought on the site of the publishing house "Nikeya".

Crisis of griefIt is impossible to draw a clear framework and determine exactly whether the experience of loss is complicated or not complicated in a person. But still, it is possible to indicate when the process of natural grief goes through certain stages, each of which is characterized by its own set of physical and psychological symptoms.

The symptoms of "normal" grief in the middle of the last century were identified by the German-American psychiatrist, a specialist in social psychiatry, Erich Lindemann.

The mourning process is divided into two main stages: the grief crisis and the work of grief.

The mourning process is divided into two main stages: the grief crisis and the work of grief. A crisis of grief begins with the death of a loved one or the discovery of an imminent loss, for example, when a loved one is diagnosed with a fatal illness and his days are numbered. Human consciousness rejects the fact of loss, rushes between denial, splitting, persuasion, anxiety and guilt.

According to Lindemann, the first hours after a loss are usually characterized by the presence of periodic bouts of physical suffering, spasms in the throat, fits of suffocation with rapid breathing, a constant need to breathe - this breathing disorder is especially noticeable when a person talks about his grief. At the spiritual level, grief manifests itself as tension or acute suffering. Usually the grieving person feels the unreality of what is happening, deafness, the feeling that everything is happening as if not with him. He has the so-called "tunnel vision", a veil is growing before his eyes.

Time speeds up or, conversely, stops. The perception of the surrounding reality is dulled, sometimes in the future there will be gaps in the memories of this period.

Time speeds up or, conversely, stops. The perception of the surrounding reality is dulled, sometimes in the future there will be gaps in the memories of this period. Lindemann noted that with a deep emotional experience, changes and disorders of consciousness can be observed. He describes a typical case in which it seemed to the patient that he saw his dead daughter, who was calling him from a telephone booth. He was so captured by this scene that he stopped noticing his surroundings.

It happens that a grieving person has no manifestations of strong feelings at all. Despite the deceptive external well-being, in reality the person is in a serious condition, and one of the dangers is that at any moment this imaginary calmness can be replaced by an acute reactive state.

It is possible to identify the mechanisms that are necessary for living through a crisis of grief: denial, splitting, persuasion, anxiety and guilt. When the first shock passes and the person begins to realize the reality of what is happening, the physical reactions weaken, and often there is an acute desire to return everything as it was before the loss.

At this time, it seems to people that this is just a bad dream, you just need to wake up, and the nightmare will pass.

At this time, it seems to people that this is just a bad dream, you just need to wake up, and the nightmare will pass. The well-known Russian psychotherapist, doctor of psychological sciences, professor Fedor Efimovich Vasilyuk, in his work “Surviving grief” says that denial at this stage of mourning is not a denial of the fact that the deceased is no more, but a denial of the fact that I, “grieving”, here. But loss denial allows a person to maintain the illusion that the world remains unchanged. This softens the shock and helps to gradually accept reality, which is facilitated by the rituals of farewell to the deceased adopted in different religions. Such important actions as a funeral service in the church, a memorial meal, help to accept the death of a loved one as a fait accompli.

Farewell to the deceased Farewell in the mortuary, funeral service, funeral service - what you need to know about them

Without such contact with reality, a person can get stuck in denial of the loss.

This is well illustrated by cases of missing people. Their death is very difficult to accept for loved ones. Splitting allows one part of the mind to know about the loss when the other denies it - this is when a person understands with the mind that a loved one has died, but feels his invisible presence. This is such a common phenomenon that many experts perceive it as part of the normal process of grief - people find comfort in this, the last chance to say goodbye to a loved one.

Vasilyuk writes: “There is… ‘a sort of double being’ (“I live as if on two planes,” says the mourner), where behind the fabric of reality one constantly senses another existence implicitly going through, breaking through islands of ‘meetings’ with the dead. Hope, which constantly gives rise to faith in a miracle, coexists in a strange way with a realistic attitude that guides all the external behavior of the mourner.

Persuasion manifests itself in the resistance of consciousness to what happened in such a way that, trying to deceive fate, as it were, a person concludes an internal deal, again and again remembering the last days, hours before parting, as if wishing to change the course of events: “Oh, if only.

.. I would give everything so that ... "Grieving people constantly scroll through the events associated with the loss in their heads: they remember what they did not have time to do for the departed; they regret that they paid little attention to him, did not fulfill some requests, were not affectionate enough, did not have time to say “I love”, unfairly offended and did not have time to ask for forgiveness.

.. I would give everything so that ... "Grieving people constantly scroll through the events associated with the loss in their heads: they remember what they did not have time to do for the departed; they regret that they paid little attention to him, did not fulfill some requests, were not affectionate enough, did not have time to say “I love”, unfairly offended and did not have time to ask for forgiveness. When people experience the reality of loss, they experience anxiety and helplessness. For a person who feels very insecure without his loved one, life is full of fears. Sometimes it is, for example, the fear of sleeping in the same bed or room, living in the same house.

The heaviest feeling when experiencing grief is guilt. Sometimes it can be real, more often far-fetched, but it must always be taken with great seriousness. Death exacerbates the problems that have ever taken place in a relationship, and the “stumbling blocks” that were hardly noticeable before turn into an insurmountable obstacle after the death of a loved one.

Lindemann describes it this way: “A person who has suffered a loss tries to find in the events that preceded death evidence that he did not do what he could for the deceased. He accuses himself of inattention and exaggerates the significance of his slightest missteps. The person repeats the word "should" like a spell: "I should have done this" or "I should not have done this." There are many heavy thoughts, a feeling of emptiness and meaninglessness. Over time, a rational explanation of what happened will soften the feeling of guilt, but usually it returns until there is full acceptance of the loss.

Lindemann describes it this way: “A person who has suffered a loss tries to find in the events that preceded death evidence that he did not do what he could for the deceased. He accuses himself of inattention and exaggerates the significance of his slightest missteps. The person repeats the word "should" like a spell: "I should have done this" or "I should not have done this." There are many heavy thoughts, a feeling of emptiness and meaninglessness. Over time, a rational explanation of what happened will soften the feeling of guilt, but usually it returns until there is full acceptance of the loss. Feelings of guilt before a deceased loved one: how to deal with it? When a loved one dies, a feeling of guilt often arises: you didn’t give enough, you didn’t say it, you didn’t do it, and now you can’t fix anything. Is this guilt always just, or is there something else behind it?

Israeli director Shmuel Maoz told an episode from his life.

It was about his teenage daughter, who constantly woke up late, missed her school bus, and had to call her a taxi, which cost the family dearly. Once he told his daughter to take the bus, like all children, and if she oversleeps and is late, let this be a lesson for her. The next morning, the girl got up on time, left the house, and half an hour later, her father heard a message that there had been an explosion in this bus - a terrorist attack, dozens of people had died. He rushed to call his daughter, but could not get through. In the next hour, he experienced more than he had experienced in his entire life. And then the daughter returned home alive and unharmed - she still missed that bus. Shmuel Maoz said that later he tormented himself for a long time with the thought that he seemed to have done the right thing, logically, but how would he live if his daughter died?

It was about his teenage daughter, who constantly woke up late, missed her school bus, and had to call her a taxi, which cost the family dearly. Once he told his daughter to take the bus, like all children, and if she oversleeps and is late, let this be a lesson for her. The next morning, the girl got up on time, left the house, and half an hour later, her father heard a message that there had been an explosion in this bus - a terrorist attack, dozens of people had died. He rushed to call his daughter, but could not get through. In the next hour, he experienced more than he had experienced in his entire life. And then the daughter returned home alive and unharmed - she still missed that bus. Shmuel Maoz said that later he tormented himself for a long time with the thought that he seemed to have done the right thing, logically, but how would he live if his daughter died? Probably, this “but” always arises in front of a person when trouble happens to his loved ones. It seems that he did everything, but .

.. But he could have done more, better, could have foreseen everything, warned, averted trouble.

.. But he could have done more, better, could have foreseen everything, warned, averted trouble. The stages of living through grief come in waves, one wave of denial, splitting, persuasion, anxiety, guilt is rarely enough to accept the loss.

Over time, they qualitatively change and the impulse "I need to call my mother" is gradually replaced by a more urgent need - "I need to be able to call my mother." The weight of the loss begins to be felt. During a crisis of grief, many processes occur at the level of the unconscious; dreams indicate that serious internal work is underway to overcome the feeling of loss. They solve the main task of the crisis of grief - the recognition of the need to accept the death of a loved one.

Work of grief

The process of mourning is called the work of grief. This is a huge mental work to process tragic events, the main task of which is not to forget, to preserve the memory of a dear person, while building new relationships with a world in which this person no longer exists.

The work of grief begins when a person accepts the fact of death. Then complex processes of overcoming take place, as a result of which the lost relationships gradually become memories, which, ideally, do not completely absorb a person, but transfer grief into a state of light sadness.

It should be noted that with all the variety of Western studies, the experience of grief and loss comes down to one scheme of Sigmund Freud, given by him in Sorrow and Melancholy: "Out of sight, out of mind." “Freud's theory explains how people forget the departed, but it does not even raise the question of how they remember them. We can say that this is the theory of oblivion,” writes psychotherapist Fyodor Vasilyuk.

In the book of Metropolitan Anthony of Surozh “Life and eternity. 15 Conversations on Death and Suffering” is an important evidence of the attitude towards death of the British: “Here, in England, the attitude towards death is very surprising for a Russian person like me.

It has improved somewhat, I dare say, not much, but it has become, let's say, less terrible. And when I first met him, I was amazed. I was under the impression that it was something completely obscene for a good Briton to die, that people should not do this to their friends and relatives, and if they fell so low as to leave this world, they would be hidden in their room until the funeral home will not take them to their place of rest and will not release the family from their presence, because in relation to their relatives a person should not do such an obscene thing as dying.

It has improved somewhat, I dare say, not much, but it has become, let's say, less terrible. And when I first met him, I was amazed. I was under the impression that it was something completely obscene for a good Briton to die, that people should not do this to their friends and relatives, and if they fell so low as to leave this world, they would be hidden in their room until the funeral home will not take them to their place of rest and will not release the family from their presence, because in relation to their relatives a person should not do such an obscene thing as dying. “Grief is not just one of the feelings, it is a constitutive anthropological phenomenon: not a single most intelligent animal buries its fellows. To bury is to be human. But to bury is not to discard, but to hide and preserve. And on the psychological level, the main acts of the mystery of grief are not the separation of energy from the lost object, but the arrangement of the image of this object for storage in memory.

Human grief is not destructive (to forget, tear off, separate), but constructive, it is designed not to scatter, but to collect, not to destroy, but to create - to create memory, ”says Vasilyuk’s work“ Survive Grief.

Human grief is not destructive (to forget, tear off, separate), but constructive, it is designed not to scatter, but to collect, not to destroy, but to create - to create memory, ”says Vasilyuk’s work“ Survive Grief. There are two main components of successful grief work: re-understanding the relationship with the deceased in order to appreciate what they mean to us, and then "translate" them into the category of "memories without a future."

Surviving means realizing what happened, accepting changes in life, adapting to the changed situation and gradually replacing the feeling of suffering and pain with a calm memory.

Freud, in his work "Sadness and Melancholy", stressed that we never voluntarily give up our emotional attachments, and that we have been abandoned, rejected or left does not mean that we end relationships with those who did this . After the death of a loved one, we, one way or another, continue to respond to his emotional presence, while realizing that the person is not with us.

In order to understand what we lost with the departed and what these relationships were for us, we return to them, look through them over and over again and play them again in memory, dreams, daydreams. Warm memories cause feelings of happiness, unfinished disputes and conflicts make us experience disappointment, anger, sadness again and again. The task of the work of grief is to bring us back again and again to these situations and states until we calmly look at them and accept them as they were.

In order to understand what we lost with the departed and what these relationships were for us, we return to them, look through them over and over again and play them again in memory, dreams, daydreams. Warm memories cause feelings of happiness, unfinished disputes and conflicts make us experience disappointment, anger, sadness again and again. The task of the work of grief is to bring us back again and again to these situations and states until we calmly look at them and accept them as they were. One of the biggest obstacles to adjusting to a new life, according to Lindemann, is that many people try to avoid the intense pain associated with grief and the emotional expression required for this experience.

That is why painful manifestations are observed in the form of a delay in the reaction or in its various distortions. The ability to perform the work of grief depends on many things, including age, the degree of personal maturity. In the absence of healthy breakups in the past, the work of grief is much slower.

Before coming to terms with a new loss, a person is forced to experience the previous unfinished losses.

Before coming to terms with a new loss, a person is forced to experience the previous unfinished losses. The work of grief is exhausting. Unconsciously, a person again and again returns to the past and is under its weight. He is constantly faced with loneliness and acute longing. It takes a lot of strength. Time passes, and little by little the demands of the present begin to assert themselves. The person begins to feel the desire to move on. However, a part of him is still gripped by grief. The desire to end the mourning and only from time to time remember the deceased can be unconsciously perceived as a betrayal, cause a feeling of guilt and slow down the processes of grief.

When does grief end?When it seems that grief is over and everything is over, it can sometimes return in the form of acute experiences. In memorable places or on memorable dates. And that's okay.

Let me give you an example from my own life. Two and a half years have passed since my mother's death, and I finally decided to come to her empty apartment to sort things out and prepare the apartment for sale.

It seemed to me that I had already experienced everything and accepted everything. My son and I sorted things out, sometimes hovering over something for a long time, sometimes very quickly deciding who to give what to, where to give what. Behind every item were many of my memories. I talked about something, we laughed, joked, sometimes sad, but in general I had the feeling that everything was going well and I was so afraid in vain. And I also thought: “It’s good that my son went with me.” And on the third day, I suddenly had a very familiar and very severe headache, and I said: “How strange, such a state, as if I have been working for an emergency for the third day.” My son answered me: “And you work for emergency situations.”

It seemed to me that I had already experienced everything and accepted everything. My son and I sorted things out, sometimes hovering over something for a long time, sometimes very quickly deciding who to give what to, where to give what. Behind every item were many of my memories. I talked about something, we laughed, joked, sometimes sad, but in general I had the feeling that everything was going well and I was so afraid in vain. And I also thought: “It’s good that my son went with me.” And on the third day, I suddenly had a very familiar and very severe headache, and I said: “How strange, such a state, as if I have been working for an emergency for the third day.” My son answered me: “And you work for emergency situations.” Loss Oncopsychologist - about personal experience of loss, feelings of guilt and warm memories that illuminate the darkness

Loss can always "come alive" and cause acute pain again, it can return on anniversaries or at moments of important life milestones.

But gradually more and more memories appear, freed from pain, guilt, resentment. A person gets the opportunity to escape from the past and turns to the future - he begins to plan his life without the deceased. At this stage, life enters its own track, sleep, appetite, daily activities are restored, the deceased ceases to occupy all thoughts.

But gradually more and more memories appear, freed from pain, guilt, resentment. A person gets the opportunity to escape from the past and turns to the future - he begins to plan his life without the deceased. At this stage, life enters its own track, sleep, appetite, daily activities are restored, the deceased ceases to occupy all thoughts. The meaning and task of the work of grief is to make a person forgive himself, let go of resentment, and take responsibility for his life. The image of the deceased must take its permanent worthy place in his life, then the person himself will return.

Remembering the deceased, he will no longer experience grief, but sadness - a completely different feeling. And this sadness will forever remain in the heart. If there are tears, they must be wept. But then there comes a time when you can say to yourself: if right now you can restrain yourself and not cry, don’t cry. We must get off the path of tears. If you continue to walk along it, the path can turn into a groove, and then into a trench so deep that it will be impossible to get out of it unless a hand is extended from above.

And if you don’t want to reach out in response, then after a while not a single hand will simply be able to reach you - you will be so deep.

And if you don’t want to reach out in response, then after a while not a single hand will simply be able to reach you - you will be so deep. Heavy mourning is not synonymous with love, and to stop mourning does not mean to betray the departed. Because it will not go anywhere from the heart, because Love does not go anywhere.

Stages of grief

- Shock and numbness (from a few seconds to several days). May result in an acute reactive state.

- Suffering and disorganization - acute grief (6-7 weeks). Grief work becomes the leading activity.

- Stage of residual shocks and reorganization (up to a year). Loss gradually enters into life.

- Completion (1-1.5 years after loss). Grief is replaced by sadness.

The stage of acute grief may include:

- Denial as a natural defense mechanism to maintain the illusion that the world remains unchanged. It is not the fact of loss that is denied, but its irreversibility.