How culture influences perception

Culture’s Influence on Perception – On Psychology and Neuroscience

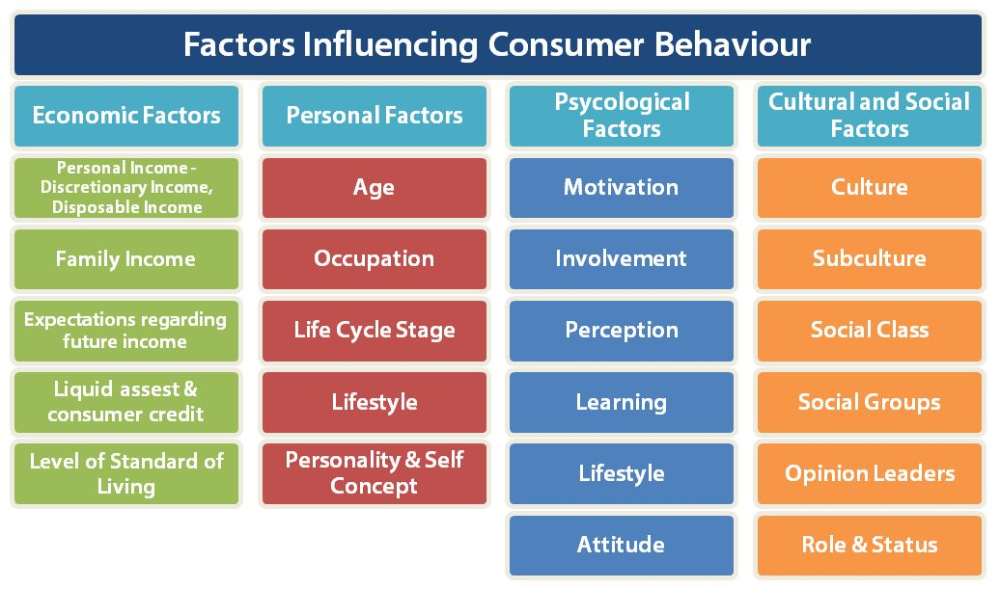

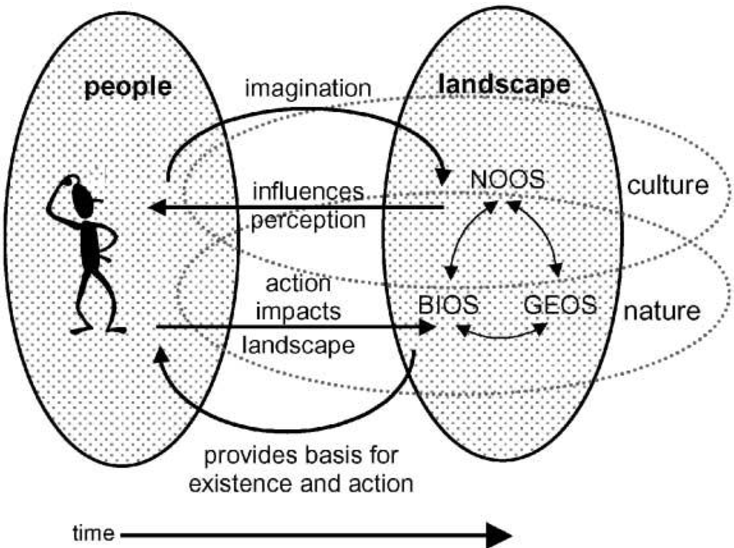

Culture plays an important role in molding us into the people we are today. It creates an environment of a shared belief, way of thinking, and method interacting among that group of people. It is dynamic and constantly changing across time. The culture you are born into will shape your eating behavior, such as what you eat, when you eat, and even how you eat. It will influence the clothes you choose to wear and the sports you play. Social norms set forth by your culture will determine how you interact with family members, friends, and strangers. Do you shake their hand when you great someone or kiss them on the cheek? It is clear that your environment shapes much of your outward behavior; but did you know that culture also influences brain function, altering the way you think about and perceive the world around you?

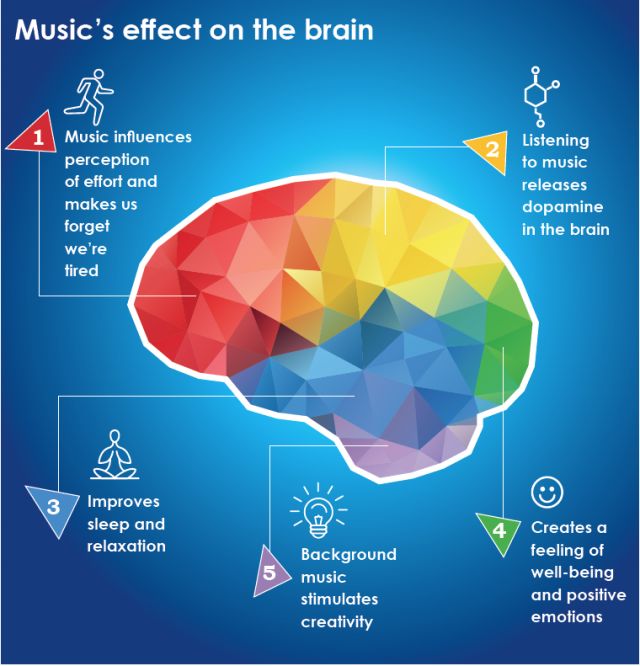

The words our culture uses is one such example of this phenomenon. The words our language provides impacts the way we are able to think. In a study done by Frank (2008) Pirahã speakers, a language spoken in small areas of the Amazon, were asked to count varying size groups of objects. However, there are no number words in the Pirahã language. Instead they describe amount do to relative size. Hói discribess a small number hoí describes a slightly larger number, and baágiso describes an even larger number. Thus if the groups were not directly next to each other and relatively the same size, Pirahã speakers could not say which group was larger. Counting is not important in day-to day lives and thus is not represented in their language. The researcher surmised that it was this lack of number language that impacted their perception of quantifies. In this way the words we use limits our cognition and thought. Have you ever been rendered speechless because you did not have the words to express your feelings? Have you ever come across a word in another language that does not exist in your own and are suddenly stunned at how you could have lived for so long without a word to describe that type of experience? In this way, words have a great impact on how we reason and perceive the world.

Furthermore language can also impact the way you think about space. The way one thinks about navigation and spatial knowledge changes depending on whether the language and culture encourages directions based on absolute frames of references (such as north and south) or relative frames of reference ( such as left and right). Kuuk Thaayorre, a small Aboriginal community on the western edge of Cape York in northern Australia, do not have navigational terms such as ‘left,’ ‘right,’ ‘backwards,’ or ‘forwards.’ Instead they describe direction in turns of north, south, east, and west. The Kuuk Thaayorre are much better at staying oriented in unfamiliar places compared to people who speak English. Their language forces them to think about space differently than English speakers, making them constantly aware of where north and south is relative to their current location.

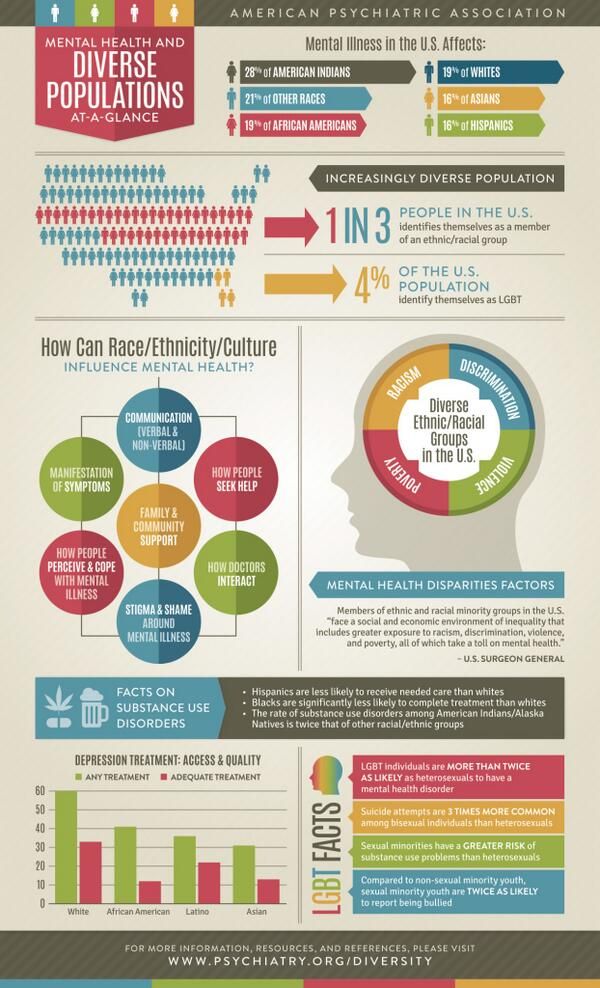

Additionally, what we pay attention to and consequently the information we process is also influenced by culture. Many studies have shown Asian and Western cultures to differ in the judgment of relative and absolute sizing of objects as well as the recollection of focal objects vs background of pictures and videos (Chioa et al., 2010). People raised in Asian cultures recall background context and relative size more accurately. On the other hand, people raised in Western culture are able to more accurately perceive the absolute size of objects and remember the focal objects of images more accurately. Goh and Park (2009) found that the brains of people from Asian and Western cultures activate different areas when performing a figure-ground recognition task.

Many studies have shown Asian and Western cultures to differ in the judgment of relative and absolute sizing of objects as well as the recollection of focal objects vs background of pictures and videos (Chioa et al., 2010). People raised in Asian cultures recall background context and relative size more accurately. On the other hand, people raised in Western culture are able to more accurately perceive the absolute size of objects and remember the focal objects of images more accurately. Goh and Park (2009) found that the brains of people from Asian and Western cultures activate different areas when performing a figure-ground recognition task.

Culture is all around us, shaping our brain and behavior. Consequently, people from various cultures will process the world differently. Furthermore subcultures exist within cultures. Religions, communities, ad regional accents and customs all work to influence your cognition and perception. As more and more research is executed, the idea of human nature dissipates and we see humanity as a group comprised of unique individuals molded by their complex and intricate culture.

Works Cited

Chiao, J. Y., Harada, T., Komeda, H., Li, Z., Mano, Y., Saito, D., … & Iidaka, T. (2010). Dynamic cultural influences on neural representations of the self. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22(1), 1-11.

Frank, M. C., Everett, D. L., Fedorenko, E., & Gibson, E. (2008). Number as a cognitive technology: Evidence from Pirahã language and cognition. Cognition, 108(3), 819-824.

Goh, J. O., & Park, D. C. (2009). Neuroplasticity and cognitive aging: the scaffolding theory of aging and cognition. Restorative neurology and neuroscience, 27(5), 391-403.

Joyner, J. (2009, June 29). Language Shapes Thought. Retrieved February 17, 2016, from http://www.outsidethebeltway.com/language_shapes_thou ght/

Like this:

Like Loading...

The Brain and Thinking Across Cultures · Frontiers for Young Minds

Abstract

People from different cultures often do things quite differently. During the last decades, there has been research about how people around the world see the world and make decisions. What are similarities and cultural differences in thinking and where do they come from? We refer to three different studies. All these studies show cross-cultural differences and how the experiences that we have growing up in a specific cultural environment can influence how we think. Even if we are not aware of it, culture influences are how we see the world and what decisions we make.

During the last decades, there has been research about how people around the world see the world and make decisions. What are similarities and cultural differences in thinking and where do they come from? We refer to three different studies. All these studies show cross-cultural differences and how the experiences that we have growing up in a specific cultural environment can influence how we think. Even if we are not aware of it, culture influences are how we see the world and what decisions we make.

In some countries, people eat roasted cockroaches, in others rabbits, in others dog meat. In some countries, adolescents fall in love and decide to spend the rest of their lives together. In other countries, the parents choose the partner whom you are supposed to marry. In some countries, when you schedule to meet someone at 2 p.m., you are actually supposed to be there at 2 p.m. In other countries, you are supposed to be there perhaps around 3 or 4 or even 5 p.m.

The knowledge people have about food preferences, partnership, and punctuality is stored in the brains of people. These cultural differences do not mean that the brains of people from different countries would actually look different, but all the knowledge, everything we learn is stored in our brain and thus the stored knowledge is different. Since the knowledge people acquire is stored in the human brain, the brain can be regarded as the center of culture.

These cultural differences do not mean that the brains of people from different countries would actually look different, but all the knowledge, everything we learn is stored in our brain and thus the stored knowledge is different. Since the knowledge people acquire is stored in the human brain, the brain can be regarded as the center of culture.

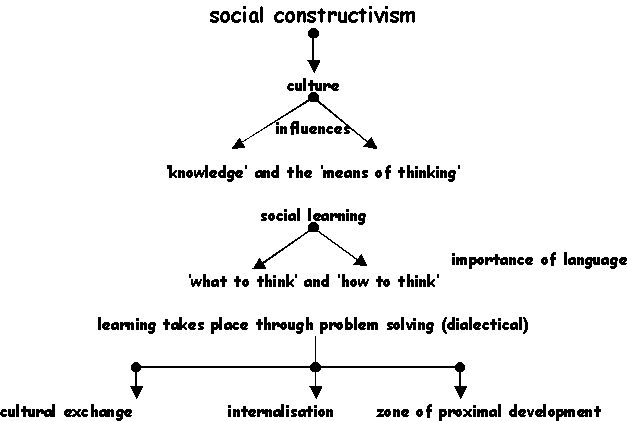

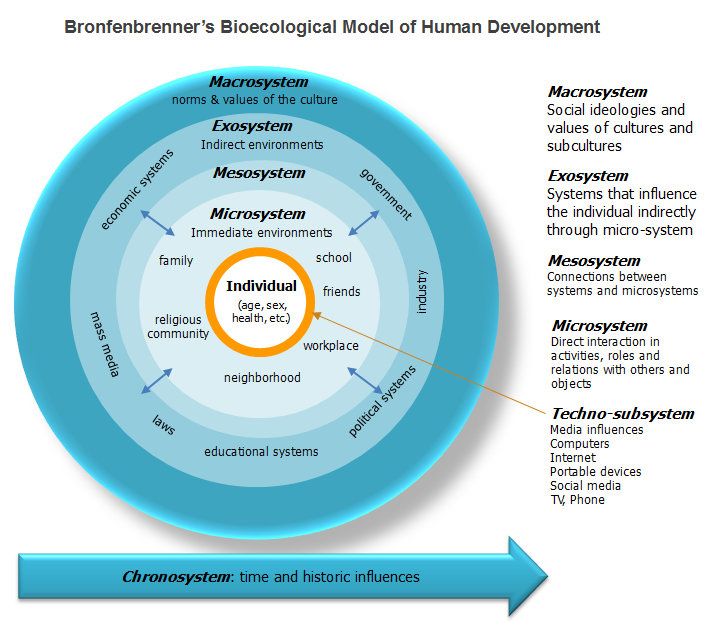

What is Culture?

Culture is knowledge used to cope with the world and each other, shared by a specific group of people, and passed on from generation to generation [1]. Cultures differ in their norms (what people are supposed to do in certain situations, e.g., greetings or what to eat) and values (what people regard as important, e.g., protecting the honor of the family or who to marry), but people from different cultures also differ in their thinking. Cross-cultural psychologists are scientists who study how people around the world are similar or different (also in terms of their thinking) and where those similarities and differences come from [2].

Cultural Differences in Perception

Perception refers to the human senses and how people see, hear, taste, and smell parts of the outside world. Even basic brain processes, such as the way people see the lines in the Müller–Lyer Figure (Figure 1), are influenced by culture. In the Müller–Lyer figure, the upper horizontal line is often seen as being shorter than the lower horizontal line even though both lines have equal length. The angled lines at the end of the horizontal lines can make some people see the horizontal lines as being different lengths.

- Figure 1 - The Müller–Lyer illusion.

- It is used to test visual illusions. Usually people see the upper horizontal line as being shorter compared to the lower horizontal line due to its inward pointing arrow heads. Both horizontal lines, however, have equal length.

People from western societies, who grow up in environments with buildings and corners, more often fell for the Müller–Lyer illusion – that is, they thought that the bottom line was longer than the top line, compared to people from cultures who live in round huts and tents or who live in the rain forest [3].

Newer studies also show cultural differences in perception of a scene, meaning which parts of their environment they focus on or see. Specifically, some people focus on the main object in front of them (foreground) and some on the surrounding objects (background). Researchers showed Americans and Japanese an animated underwater scene on the computer screen [4]. The scene showed fish (foreground) and water snails, plants, stones (as background) (Figure 2). Participants were shown this animated scene twice for 20 s. Then, participants reported what they saw. Americans talked more often about the fast moving fish. Japanese talked more often about the background. Participants from areas in Eastern Asia, like Japan, more often perceive a scene as a whole, taking in both the foreground and the background, compared to Americans, who mainly perceive the object in the foreground.

- Figure 2 - Underwater scene – still picture from the animated scene shown on the computer screen [4], reprinted with permission.

- The moving fish are regarded as the main objects, the foreground. The plants, stones, and water snails are regarded as the background.

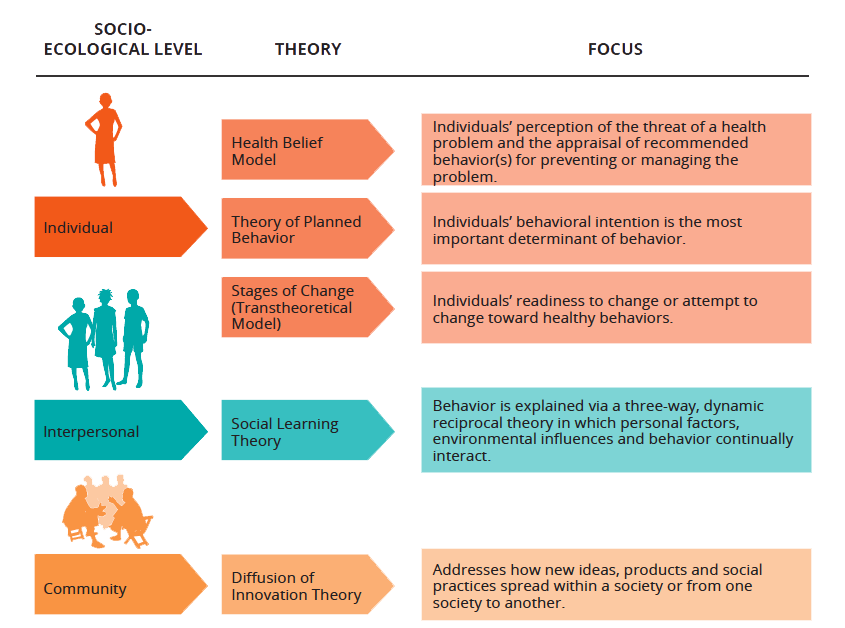

Cultural Differences in Dynamic Decision-Making and Emotions

Not only is perception influenced by culture but also more complex thought processes, such as problem solving and making dynamic decisions. A static decision is whether I buy a KitKat or a Snickers bar in a grocery. Dynamic decisions are those that are made over time in a changing environment, for example, when you think about what profession you might want to choose later in your life. This decision might change depending on who you meet, who you talk to, what you read about certain jobs, what jobs your parents have, or what your friends want to become. Another example of dynamic decision-making is what a fire-fighting commander does. The fire-fighting commander has to make many decisions to fight wild fires depending on, for example, how big or small these fires are, their location near or far from cities, the weather and wind, which can make the fire burn faster or slower, the number of fire-fighting trucks and helicopters, and how fast they can go, and the amount of water they have to extinguish the fire.

Güss and colleagues had over 500 students in Brazil, India, the Philippines (three more collectivistic countries; countries that value more the group, family, and others), Germany, and the United States (two more individualistic countries; countries that value more each person’s own goals and independence) work on two computer-simulated problem scenarios [1]. In one scenario, participants took the roles of fire-fighting commanders who had to protect cities from approaching fires (Figure 3). Everyone was seated in front of a computer screen and could give commands using the mouse during the 11 min of the simulation. They could give orders to their fire-fighting units and helicopters, for example, where they should go, which fires they should extinguish, whether they should tank water from the lakes or whether they should cut down trees to prevent fires from spreading. While participants worked on the simulation they spoke out loud everything that went through their minds, for example, “Mhh, there is no fire. Ah, no, I see one fire starting. Oh no, it is close to the city. What shall I do? Ok, I send a truck and a helicopter to extinguish the fire…” Everything they said was recorded and then written down word for word.

Ah, no, I see one fire starting. Oh no, it is close to the city. What shall I do? Ok, I send a truck and a helicopter to extinguish the fire…” Everything they said was recorded and then written down word for word.

- Figure 3 - FIRE training version with description of objects, still scene of the FIRE simulation at the start and after a few minutes when the fires start burning [5], reprinted with permission.

- The fires burnt already many trees and houses as seen on the right screen. The yellow helicopters and the red trucks can extinguish the fires.

When the researchers analyzed these thinking-aloud protocols from all participants, they first found that when people make decisions in a difficult situation, they also feel emotions, often negative emotions, such as anger or frustration, sometimes positive emotions when they succeed and are happy with their decisions. Second, the researchers found differences between people from different cultures. Indian and Filipino participants more frequently described the problem situation (e.g., “There is a fire”) and more often searched for information (e.g., “Does the truck still have enough water?”). German participants, on the other hand, talked more often about plans and goals (e.g., “First, I will send truck number 5 to the fire, and then I will send the helicopter to the city to be in a strategically good position.”) and they rarely talked about their emotions. Americans more often mentioned goals and positive emotions (“Great! I did a good job!”). Brazilians, compared to all other participants, most often expressed negative emotions (e.g., “Oh nooo. I will never be a good firefighting commander.”)

Indian and Filipino participants more frequently described the problem situation (e.g., “There is a fire”) and more often searched for information (e.g., “Does the truck still have enough water?”). German participants, on the other hand, talked more often about plans and goals (e.g., “First, I will send truck number 5 to the fire, and then I will send the helicopter to the city to be in a strategically good position.”) and they rarely talked about their emotions. Americans more often mentioned goals and positive emotions (“Great! I did a good job!”). Brazilians, compared to all other participants, most often expressed negative emotions (e.g., “Oh nooo. I will never be a good firefighting commander.”)

Where do these cultural differences come from? Why do people from some cultures mention more goals and plans, and why do others talk more about their emotions? Researchers tested and confirmed a model stating that the values we are taught by the culture we grow up in influence our problem solving and decision making styles [6]. Cultures that value the importance of each person’s own goals and independence, for example, were related to making more decisions and more detailed planning compared to cultures that value the importance of group and others.

Cultures that value the importance of each person’s own goals and independence, for example, were related to making more decisions and more detailed planning compared to cultures that value the importance of group and others.

Conclusion

The three studies described here – the Müller–Lyer Illusion, figure-ground perception, and dynamic decision-making – show that these mental (and sometimes emotional) processes are happening within a certain culture and are influenced by the experiences we have living in a specific cultural environment. So sometimes we might think we make decisions, but it is more the cultural experiences stored in our brain that make our decisions. Even if we are not aware of it, culture influences how we see the world, what decisions we make, how we approach problems, and how we solve them. Do you think whether you play soccer or basketball, or whether you choose to eat chips or strawberries, or whether you study to be a nurse or a manager could be influenced by culture?

References

[1] ↑ Güss, C. D., Tuason, M. T., and Gerhard, C. 2010. Cross-national comparisons of complex problem-solving strategies in two microworlds. Cogn. Sci. 34:489–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-6709.2009.01087

D., Tuason, M. T., and Gerhard, C. 2010. Cross-national comparisons of complex problem-solving strategies in two microworlds. Cogn. Sci. 34:489–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-6709.2009.01087

[2] ↑ Berry, J. W., Poortinga, Y. H., Breugelmans, S. M., Chasiotis, A., and Sam, D. L. 2011. Cross-Cultural Psychology: Research and Applications. 3rd ed. Cambridge, IN: Cambridge University Press.

[3] ↑ Segall, M. H., Campbell, D. T., and Herskovits, M. J. 1966. The Influence of Culture on Visual Perception. Indianapolis, IN: The Bobbs-Merrill Company.

[4] ↑ Nisbett, R. E., and Miyamoto, Y. 2005. The influence of culture: holistic versus analytic perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9:467–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.004

[5] ↑ Schaub, H. 2005–2015. Firefighting computer simulation game.

[6] ↑ Güss, C. D. 2011. Fire and ice: testing a model on cultural values and complex problem solving. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 42:1279–98. doi: 10.1177/0022022110383320

J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 42:1279–98. doi: 10.1177/0022022110383320

The influence of culture on perception - Studiopedia

Share

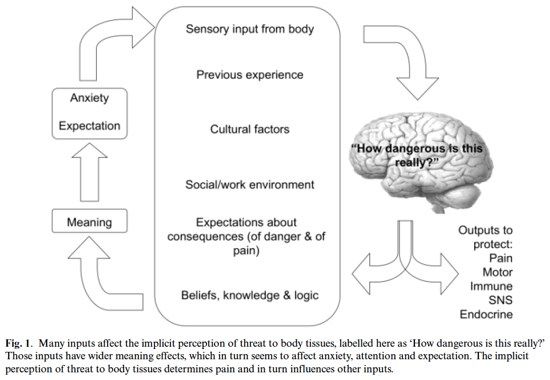

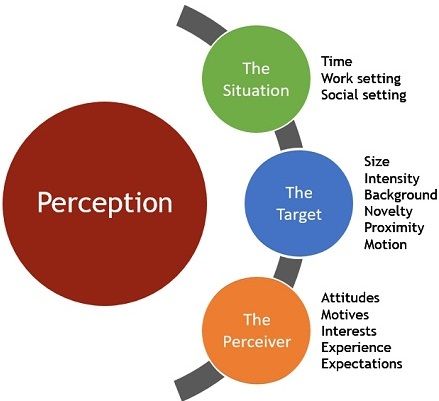

It has been experimentally proved that the mechanism of perception of each person is original and unique, but this does not mean at all that the ability to perceive the world in a certain way is given to a person from birth. Perception is formed through the active interaction of a person with his cultural and natural environment and depends on a number of factors, such as gender, experience, upbringing, education, needs, etc. But not only these characteristics have an impact on the formation of perception. The cultural and social environment in which the formation of a person takes place plays a significant role in the way he perceives the surrounding reality. The influence of the cultural component of perception can be seen especially clearly when we communicate with people belonging to other cultures. A significant number of gestures, sounds and types of behavior are interpreted by speakers of different cultures ambiguously. For example, your German friend gave you eight beautiful roses for your birthday. It is clear that eight or ten no longer matters. The only important thing is that the number of roses is even. You understand that your friend may not know what to bring to the funeral. But according to your cultural interpretation, you have an unpleasant feeling.

For example, your German friend gave you eight beautiful roses for your birthday. It is clear that eight or ten no longer matters. The only important thing is that the number of roses is even. You understand that your friend may not know what to bring to the funeral. But according to your cultural interpretation, you have an unpleasant feeling.

This simple example is a good illustration of the fact that a person's cultural identity determines his interpretation of this or that fact. That is, when a cultural component is added to the perception of any element of reality, then its objective interpretation becomes even more problematic. This is explained by the fact that culture gives us a certain direction in the perception of the world by the senses, which affects how the information received from the surrounding world is interpreted and evaluated. For example, we notice differences between people within our cultural group quite accurately, while people from other cultures are often perceived as similar to each other. The result of this perception, despite its absurdity, was the widespread expression "the face of Caucasian nationality." We can say that by exposing large groups of people to the same impact, culture generates similar values, meanings and similar behavior of its members.

The result of this perception, despite its absurdity, was the widespread expression "the face of Caucasian nationality." We can say that by exposing large groups of people to the same impact, culture generates similar values, meanings and similar behavior of its members.

Another cultural determinant that determines a person's perception of reality is the language in which he speaks and expresses his thoughts. At one time, scientists asked themselves the question: do people of one linguistic culture really see the world differently than another? As a result of observations and studies of this issue, two points of view have developed: nominalist and relativistic.

The nominalist position assumes that a person's perception of the surrounding world is carried out without the help of the language we speak. Language is simply an external "form of thought". Therefore, in the course of mental activity in the minds of all people, the same images of reality are formed, which can be expressed in different ways in different languages. In other words, any thought can be expressed in any language, despite the fact that some languages require more words to express it, while others require fewer words. Different languages do not mean that people have different perceptual worlds and different thought processes.

In other words, any thought can be expressed in any language, despite the fact that some languages require more words to express it, while others require fewer words. Different languages do not mean that people have different perceptual worlds and different thought processes.

The relativistic position assumes that the language we speak, especially the structure of this language, determines the features of thinking, perception of reality, structural patterns of culture, stereotypes of behavior, etc. This position is well represented by the already mentioned hypothesis of E. Sapir and B. Whorf, according to which any language system is not only a tool for reproducing thoughts, but also a factor shaping human thought, becomes a program and guide for the mental activity of an individual. That is, the formation of thoughts is part of a particular language and differs in different cultures, and sometimes quite significantly, as well as the grammatical structure of languages.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis was of great importance for the scientific vision of the problems of language and its impact on everyday communication. It calls into question the basic postulate of the supporters of the nominalist position that we all have the same perceptual world and the same sociocultural reality. Convincing arguments in favor of this hypothesis are also terminological variations in the perception of colors in different cultures. The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis shows that Anglophones and Navajos perceive colors differently. The Navajo Indians use one word for blue and green, two words for two shades of black, one word for red. That is, the perception of color is a culturally determined characteristic. Moreover, the difference between cultures in the perception of color takes place in two planes: firstly, cultures differ both in the number of colors that have their own names, and in the degree of accuracy of the difference in shades of the same color in a given culture.

Each culture establishes a certain spectrum, in which there are boundaries that separate one name from another. For example, blue in Russian culture corresponds to light blue in German, and so on. Secondly, the meaning given to color also varies significantly from one culture to another. In one culture, red would mean love, black would mean sadness, white would mean innocence, and so on. For representatives of another culture, the same colors are given a different interpretation. For example, red in many cultures is associated with danger or doom.

From what has been said, it follows that language is of paramount importance in relation to culture, but there is another approach, which lies in the fact that it is culture that influences the expression of concepts and categories in language, that is, it (culture) is given paramount importance. According to E. Hall, the paradox of culture lies in the fact that language is a system of concepts most often used to describe a culture that is poorly adapted to this difficult task. A person must constantly look back at the limitations that language imposes on him. In order to understand another culture and accept it at a deep level, it is necessary to experience it, grow into it, and not read or talk about it. Therefore, our interpretation of the simplest and most obvious things is necessarily culturally colored.

A person must constantly look back at the limitations that language imposes on him. In order to understand another culture and accept it at a deep level, it is necessary to experience it, grow into it, and not read or talk about it. Therefore, our interpretation of the simplest and most obvious things is necessarily culturally colored.

1.1.2. The influence of culture on perception

experimental it has been proven that the mechanism of perception everyone a person is unique and unique, however, this does not mean at all that the ability to perceive the world in a certain way way given to a person from birth. Perception formed through active human interaction with surrounding cultural and natural environment and depends on a number of factors such as like gender, experience, upbringing, education, needs, etc. But not only these characteristics provide influence on the formation of perception. The cultural and social environment in which passes the formation of man, plays a significant role in the way their perception of the surrounding reality. Influence of cultural component of perception can be seen especially clearly when we associate with people who belong to other cultures. A significant number of gestures, sounds and types of behavior interpreted by speakers of various cultures is not clear. For example, your German friend gave for your birthday eight wonderful roses. It's clear that eight or ten no longer matters. The only thing that matters is that the number of roses is even. Do you understand that your friend may not know that bring n & the funeral. But according to your cultural interpretation, you have an uncomfortable feeling.

Influence of cultural component of perception can be seen especially clearly when we associate with people who belong to other cultures. A significant number of gestures, sounds and types of behavior interpreted by speakers of various cultures is not clear. For example, your German friend gave for your birthday eight wonderful roses. It's clear that eight or ten no longer matters. The only thing that matters is that the number of roses is even. Do you understand that your friend may not know that bring n & the funeral. But according to your cultural interpretation, you have an uncomfortable feeling.

This a simple example serves as a good illustration that cultural affiliation human determines the interpretation of AND M one fact or another. That is, when perception of some

204 Section III . Social and psychological aspects \l 1

with 9as representatives other cultures are often perceived similar Each other. The result of this perception, despite its absurdity, has become a common expression "The face of the Caucasian * Kazakh nationality." It can be said that, Exposing Bolysch E groups people to the same exposure, culture generates similar meanings, meanings and similar behavior of her members.

The result of this perception, despite its absurdity, has become a common expression "The face of the Caucasian * Kazakh nationality." It can be said that, Exposing Bolysch E groups people to the same exposure, culture generates similar meanings, meanings and similar behavior of her members.

Another cultural determinant that determines human perception reality is the language in which he speaks and expresses your thoughts. At one time, scientists asked question: really Do people of the same linguistic culture see world differently, | how another? As a result of observations and research on this issue There are two points of view: nominalist and relativistic,

Nominalist item suggests what a human perception! com environment is carried out without help of the language in which We are speaking. Language is just external "form of thought". Therefore, in the course of thought activities in the minds of all people form the same images realities that can be expressed in different ways in different languages, other words, any thought can be expressed in any language despite the fact that in some languages its expression will be required more, while others have fewer words. Various languages don't mean that people have different perceptual worlds, but mental processes are different.

Various languages don't mean that people have different perceptual worlds, but mental processes are different.

Relativistic item suggests that the language we we speak, especially the structure of this language, defines features thinking, perception of reality, structural patterns of culture, stereotypes of behavior, etc. This position well represented already mentioned hypothesis of E. Sapir and B. Whorf *> according to which any language system is not only in-1 playback tool thoughts, but also a factor, form-; roaring human thought becomes a program and leadership mental activity of the individual. That is, the formation thoughts is part of this or that tongue and spill] 9uniqueness. She calls into question the basic postulate supporters nominalist position that we we all have one

th m and the same perceptual world and one and the same socio-1! cultural reality. Convincing arguments in favor of

toy hypotheses are also terminological variations in the perception of colors in different cultures. Sapir-Whorf hypothesis shows that representatives of English-speaking cultures and Navajo Indians perceive colors differently. Indians Navajo use one word for blue and green, two words for two shades black, one word for red. That there is a perception of color is culturally conditioned characteristic. Moreover, the difference cultures in the perception of color passes in two planes: first, cultures vary in number colors that have their own names, and according to the degree of accuracy of the difference in shades the same color in a given culture.

Sapir-Whorf hypothesis shows that representatives of English-speaking cultures and Navajo Indians perceive colors differently. Indians Navajo use one word for blue and green, two words for two shades black, one word for red. That there is a perception of color is culturally conditioned characteristic. Moreover, the difference cultures in the perception of color passes in two planes: first, cultures vary in number colors that have their own names, and according to the degree of accuracy of the difference in shades the same color in a given culture.

Each culture establishes a certain the spectrum in which the boundaries are located, separating one name from another. For example, blue color in Russian culture corresponds to light blue in German, etc. Secondly, the value given color, also varies significantly from one culture to another. In one culture, red will be mean love, black means sadness, white - innocence, etc. For representatives another cultures the same colors are given another interpretation. For example, red in many cultures associated with danger or death.

For example, red in many cultures associated with danger or death.

From from what has been said, it follows that the language has paramount importance in relation to culture, however, there is and another approach which is exactly what culture renders radiance on the expression of concepts and categories in language, that is, her (culture) is given paramount importance. By according to E. Hall, p aradox culture is that language is it's a withdrawal system, most commonly used to describe cultures, to °second poorly adapted to this difficult tasks. Man T°false keep an eye on the limits which imposes tongue on him. To understand other culture and p it at a deep level, it is necessary survive it, grow in

"1

206 Section III . Social and psychological aspects TSUM

in her, not to read or talk about her. Therefore, our intern* I tation the simplest and most obvious things is obligations, I culturally painted.

Therefore, our intern* I tation the simplest and most obvious things is obligations, I culturally painted.

1.2. Impact of attribution on recycling information in the process of intercultural communication

1.2.1. The concept and essence of attribution

AT process of intercultural interaction man perceive. takes another along with his actions and through actions. From adequacy understanding of actions and their causes in many ways construction depends interactions with other people and ultimate success communication with him. However, the most common reasons and processes determining the behavior of another person, remain hidden and inaccessible. Therefore, attempts form a view about other people and explain their actions without sufficient this information ends attributing motives to them behavior, "thinking out" their characteristics, that seem characteristic of one or another individual.

Naturally, that the mechanism of such understanding has become subject of scientific interest of psychologists and gradually there was a separate] direction in social psychology, which has become explore-] processes and outcomes attributing causes of behavior! Attempts explain the reasons for people's behavior scientists named attributions. B modern science attribution is considered as a process interpretation through which individual ascribes observed and experienced events or actions defined the reasons. Interpretation of the causes of behavior human is undertaken first, when it doesn't fit in representations and logical explanations, used explaining in his life. Exactly at situation* intercultural contacts existence attributions can be traced especially distinctly, because constantly have to explain "unusual" behavior. 9oD attributing to another the intention to commit some act. According to him assumptions in the behavior of each human two main components can be distinguished: diligence and skill. He sees effort as intention to take action and efforts made to implement these intentions. Skill is defined by him as the difference between abilities take action and be objective difficulties preventing performing these actions. Because the intentions, efforts and abilities belong to man, and difficulties are determined by external circumstances, then the "naive observer" attributing the main any of these factors, can conclude about why the person did the action.

B modern science attribution is considered as a process interpretation through which individual ascribes observed and experienced events or actions defined the reasons. Interpretation of the causes of behavior human is undertaken first, when it doesn't fit in representations and logical explanations, used explaining in his life. Exactly at situation* intercultural contacts existence attributions can be traced especially distinctly, because constantly have to explain "unusual" behavior. 9oD attributing to another the intention to commit some act. According to him assumptions in the behavior of each human two main components can be distinguished: diligence and skill. He sees effort as intention to take action and efforts made to implement these intentions. Skill is defined by him as the difference between abilities take action and be objective difficulties preventing performing these actions. Because the intentions, efforts and abilities belong to man, and difficulties are determined by external circumstances, then the "naive observer" attributing the main any of these factors, can conclude about why the person did the action. In accordance with the ideas Haider observer, owning only information about the content of the action, can explain behavior or personality traits acting or the influence of external environment. According to him, the construction of attributions associated with the desire to simplify environment and try to predict the behavior of other people. In this context attributions perform the most important mental function as do events and events are predictable controlled and understandable.

In accordance with the ideas Haider observer, owning only information about the content of the action, can explain behavior or personality traits acting or the influence of external environment. According to him, the construction of attributions associated with the desire to simplify environment and try to predict the behavior of other people. In this context attributions perform the most important mental function as do events and events are predictable controlled and understandable.

Other explanation of attribution, allowing you to find its cause and in person, and in the environment, suggested Harold Kelly. In his opinion, information about an action evaluated on three aspects: consistency, stability and discrimination. Consistency means degree of uniqueness in relation to accepted in society norms of behavior. At the same time, low consistency reflects the uniqueness of this behavior, and high means that this action is normal for most people in Dana situations.