Highly social autism

Social Communication - Autism Tasmania

People on the autism spectrum are just as likely as their typically developing peers to enjoy engaging with others in activities that interest them. Difficulties with social communication are however a diagnostic criterion for autism and they present in a spectrum of ways. Some people on the autism spectrum may seek social opportunities and may initiate social interactions themselves, others may enjoy social situations and interactions when they are initiated effectively by others. Many have a genuine desire for friendship but may find the process of making and sustaining friendships difficult.

“…everyone wants to inherently connect with others, it’s just through a different filter.” – Chris Varney – Founder and Chief Enabling Officer of the I CAN Network

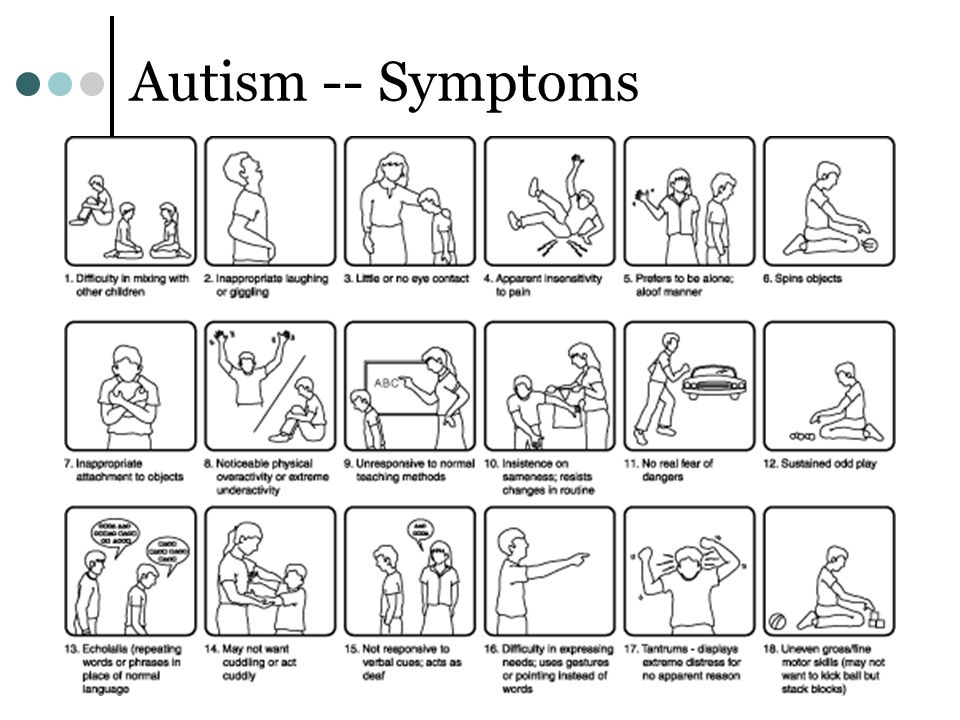

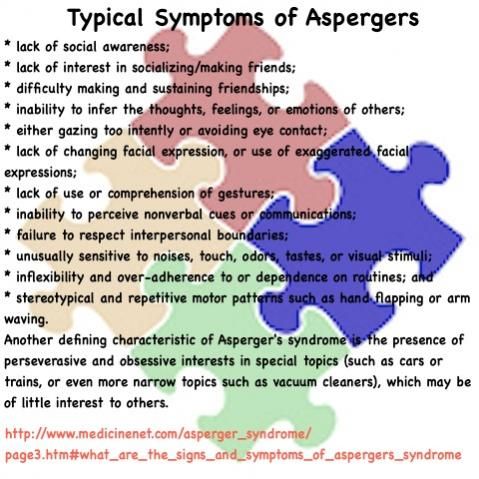

A person on the autism spectrum may display a number of social communication differences. It is important to remember that not every item on the following list applies to all. They may:

- Not respond, or may take longer to respond, to verbal communication by other people

- Find eye contact uncomfortable

- Rarely use nonverbal gestures to communicate (for example, nodding their head or gesturing with their hands)

- Not take social cues from other people’s actions (for example lining up in a queue, stop talking when the teacher enters the room). People on the autism spectrum may need these “hidden” social rules to be explicitly taught

- Echo words they hear – they may repeat patterns of words without attaching any apparent meaning to them. They may be exceptional at mimicry and use this effectively to fit in socially.

- Have difficulty effectively communicating their own wants and needs. This often leads to frustration.

- Display a reduced tendency to share their interests with others, or the sharing is unequal (for example, the person may talk excessively about their own interests without referencing to see if the other person is interested).

“Striking up conversations with strangers is something like extreme sports for Autistic people” Kamran Nazeer

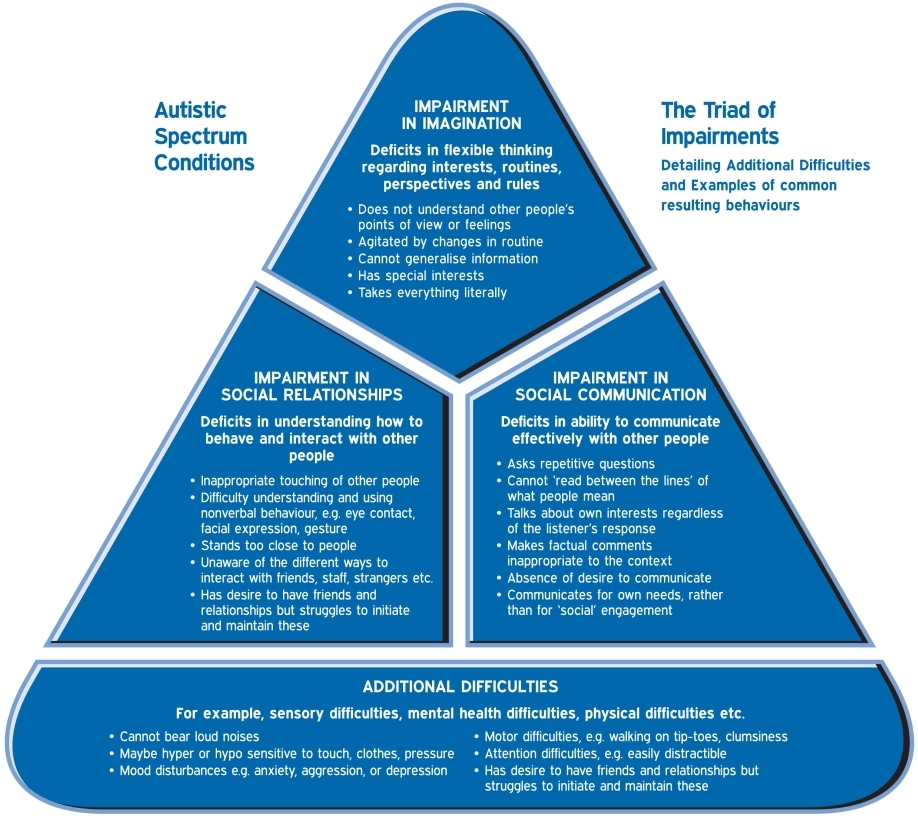

There are two particular social communication differences experienced by many people on the autism spectrum which provide insight into why social interactions are often challenging: predicting and interpreting others’ behaviour, and receptive and expressive communication differences.

Predicting and interpreting others’ behaviour

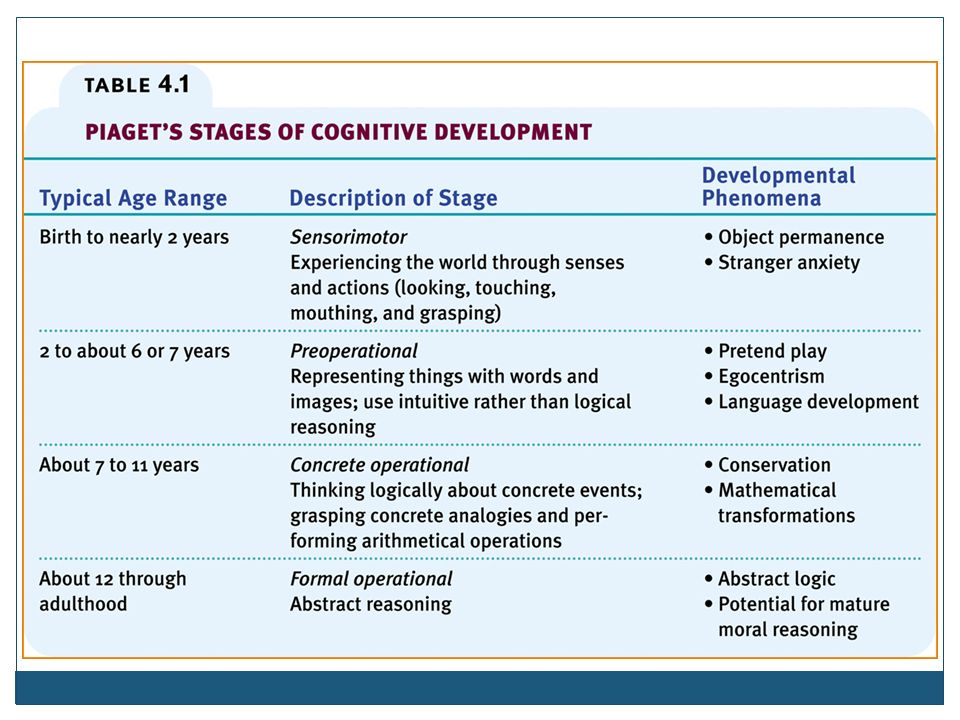

Theory of mind refers to the understanding that other people have different thoughts, desires and needs to you. It involves being able to “put yourself in someone else’s shoes”. Delayed development of theory of mind may impact on a person’s social interactions. He/she may have difficulty predicting and interpreting the behaviours of others and may also have trouble understanding the effects of their own behaviour on the people around them.

“It is an intellectual process, rather than intuitive, which is why socialising is draining”.

Alex Sina

Individuals on the autism spectrum often have difficulty recognising and understanding social cues and therefore do not instinctively learn to adjust their behaviour to suit different social contexts.

People with autism may well have the potential to learn these skills however. See subsection “Supporting social development” for more information.

Receptive and expressive communication

Communication differences in autism can be divided into two different domains: receptive communication and expressive communication

Receptive communication

Receptive communication refers to the ability to understand the communicative attempts of others. This involves the ability to make sense of spoken language, body language, facial expressions and tone of voice. People on the autism spectrum may have difficulties in this area of communication.

Individuals with autism often understand language literally and have difficulty with understanding and using the natural rhythm in conversation. This can lead to frequent misunderstandings.

This can lead to frequent misunderstandings.

It is helpful when communicating with a person on the autism spectrum to be aware of their likely tendency towards concrete thinking. They may interpret language very literally and therefore have difficulties understanding figures of speech and metaphors. For example, when discussing the changes inherent in puberty, The Raising Children’s Network notes: “If you describe your son’s voice as ‘breaking’, your child might find this worrying. Instead you could say something like, ‘Your voice is changing and will get deeper’.”

“People say that you always have to tell the truth. But they do not mean this because you are not allowed to tell old people that they are old and you are not allowed to tell people if they smell funny or if a grown-up has made a fart. And you are not allowed to say, “I don’t like you,” unless that person has been horrible to you.” – Christopher, the fictional main character with Autism in the novel Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time.

Expressive communication

People on the autism spectrum may also show differences in their expressive communication – or using language and non-verbal behaviours to communicate a message or make themselves understood. They may show a variety of expressive communication differences. Some may experience ongoing significant delays in obtaining language; others may have a well-developed vocabulary but may use language in idiosyncratic ways.

Eye contact is another component of expressive communication. Some people on the autism spectrum may find maintaining eye contact uncomfortable, even painful, and may therefore unintentionally appear disinterested or rude.

“And now I know it is perfectly natural for me not to look at someone when I talk…In fact, I don’t really understand why it’s considered normal to stare at someone’s eyeballs.” – John Elder Robinson

Spoken language development

Some people on the autism spectrum do not develop the ability to use spoken language. However, they may use other forms of purposeful communication such as vocalisation (including crying and sounds to draw another’s attention), using gestures (such as signing, eye gaze, or pointing) or augmentative and alternative communication systems (such as picture based systems or communication technology).

However, they may use other forms of purposeful communication such as vocalisation (including crying and sounds to draw another’s attention), using gestures (such as signing, eye gaze, or pointing) or augmentative and alternative communication systems (such as picture based systems or communication technology).

Speech Generating Devices (SGDs) are an example of an augmentative and alternative communication system. Specific communication apps have also been developed which may be used on an iPad or Android tablet.

The Autism Association of Western Australia has developed an online resource, Autism Apps, that offers information about:

- how to use an iPad effectively

- how to support people with autism using technology

- tips for selecting a useful app

- Information related to the National Curriculum and Evidence Based Practice for supporting individuals with autism

“I am not able to talk out of my mouth, however I have found another way to communicate by spelling on my computer.

”- Carly Fleishmann

Supporting social development

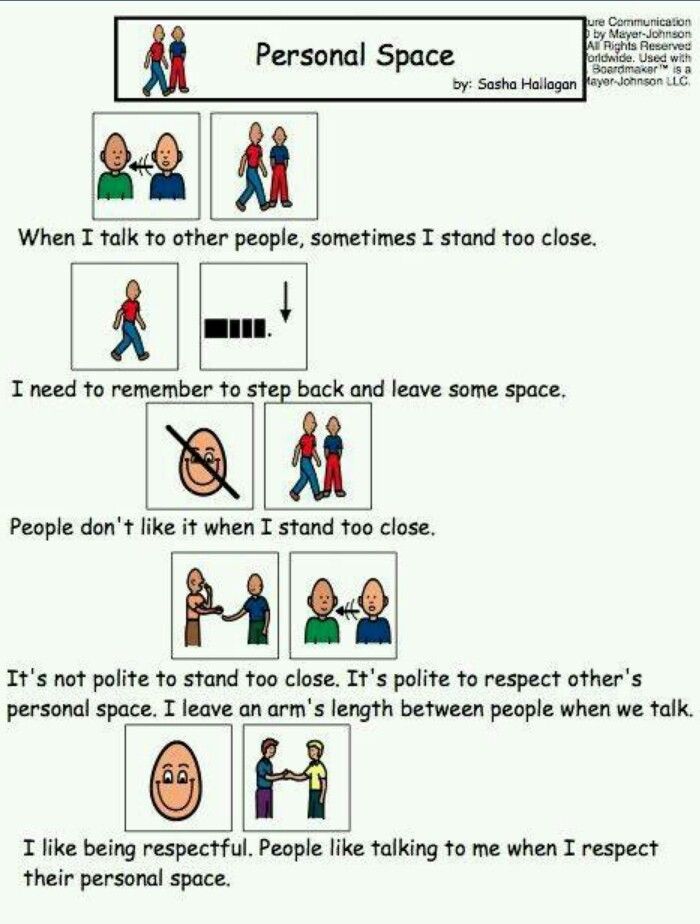

When people with autism experience social communication difficulties, their capacity and confidence to interact socially is affected. This section discusses ways in which the social development of people with autism can be supported.

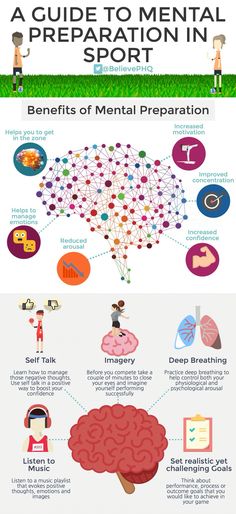

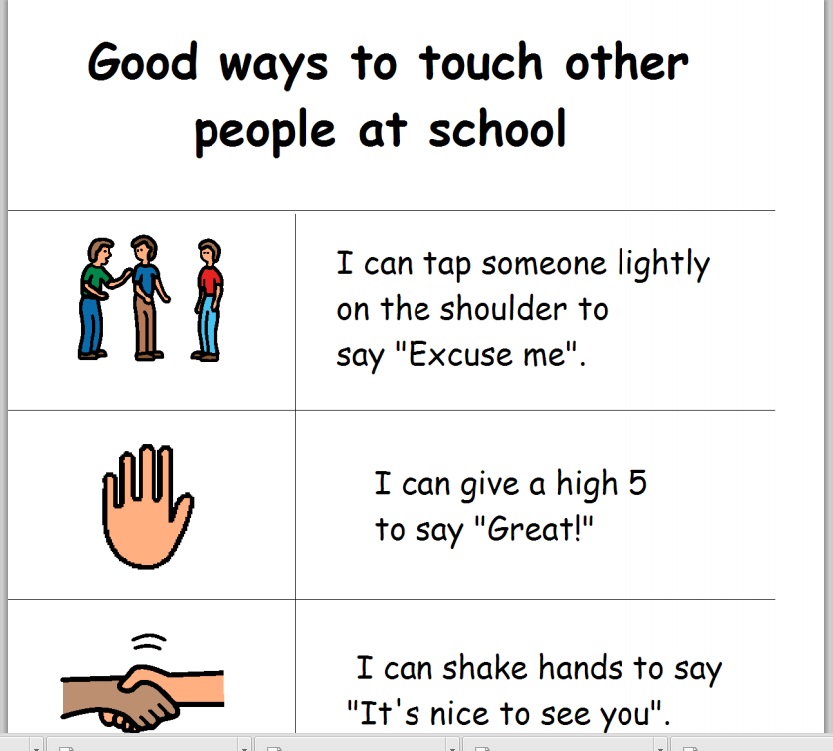

Many people on the autism spectrum can successfully improve their social interaction skills. Teaching social skills generally involves three steps:

- Social skills and expectations are broken down into manageable steps;

- These steps are explained in concrete and visual ways; and

- Opportunities to practice new skills are provided.

Teaching social skills and expectations can have a positive effect on a person’s self-confidence and mental wellbeing. Some areas in which people on the autism spectrum may need individualised support include:

Some areas in which people on the autism spectrum may need individualised support include:

- Starting and maintaining conversations

- Asking for help

- Sharing

- Reading non-verbal cues

- Recognising emotional responses

- Becoming aware of appropriate proximity and personal space

- Learning to compromise and resolve conflict

- Coping with losing

- Protective and risk reduction behaviours

- Learning to deal with peer pressure

- Learning to deal with bullying

- Developing positive friendship skills

There are several useful resources for finding out more about supporting social development:

- Raising Children’s Network website – in particular, the article ‘Social skills for teenagers with autism spectrum disorder’.

- The National Autistic Society’s articles on Communication

Specific group programs aimed at helping the person with autism to develop social skills, such as the Secret Agent Society, may also be a helpful.

Unfortunately, some people on the autism spectrum experience anxiety in regards to social interaction as a result of their sustained social efforts, self-perceived social failures and sensory hypersensitivities. This may cause the person to withdraw and avoid interaction.

If you are concerned about the mental wellbeing of a child on the autism spectrum it is wise to seek expert help. Autism Tasmania’s Autism Advisors can help you find the right health or allied health professional to assist you and your child to navigate this challenging period.

An understanding of behavioural and sensory challenges experienced by people on the autism spectrum are intertwined with understanding the challenges presented by social communication differences.

“But She’s Too Social To Be Autistic” – WRONG!

Read the latest issue of the Oaracle

“But She’s Too Social To Be Autistic” – WRONG!

September 07, 2016

By: Organization for Autism Research

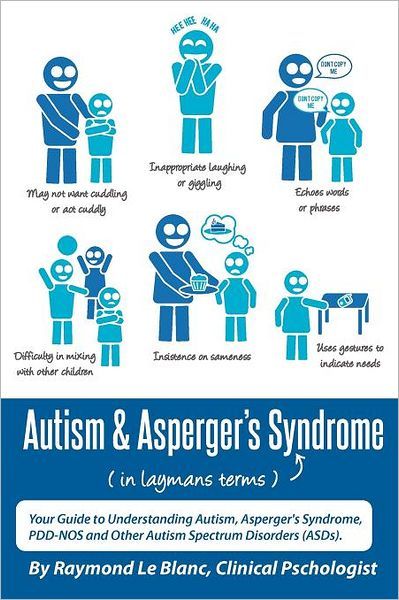

Autism looks different for each person. Although social deficits are common, there are no defining factors of autism. In a post from her blog, Girl Tribe, Jessica reflects on her experience as a parent of two girls with autism.

Although social deficits are common, there are no defining factors of autism. In a post from her blog, Girl Tribe, Jessica reflects on her experience as a parent of two girls with autism.

We have been blessed with two daughters on the autistic spectrum who have pretty opposite struggles when it comes to socialisation.

For many many years before Sno was diagnosed I got told that she was “just shy” or “very serious”. She would often struggle in large groups, noisy crowds would scare her and she has always taken a while to warm to new people. She’s definitely regarded as an introvert and isn’t really affectionate at all… but when she is, oh – it’s heart-meltingly gorgeous. Sno has always struggled with friendships and I remember her at the age of four, 2 years before she was diagnosed – coming home to me from kindergarten confused about why one of her peers wanted to hold her hand during a song they were singing. When I asked why she didn’t want to she simply told me “Well because I don’t know her. And if I don’t know her well, I don’t want her touching me.” Fair enough kid, I thought back then.

And if I don’t know her well, I don’t want her touching me.” Fair enough kid, I thought back then.

Wilding on the other hand is a completely different kettle of fish. I was told before she was diagnosed with ASD that she couldn’t be autistic because she was “too social” to have autism. She loves people, would regularly run up to random people at the library and ask them to read her stories. She is super affectionate and adores to cuddle. She makes friends easily and is loved and cherished by many simply for her embracing, warm character.

Two girls so opposite in personalities and yet they both are autistic. How is this possible? I’ll tell you how.

Being an introvert or an extrovert has nothing to do with being autistic.

It’s kinda like being right or left handed. Whilst Sno has struggles with beginnings to form friendships (a lot about the how/when/why), Wilding’s struggles are understanding appropriate social conduct and behaviour and respecting the personal space of others. In Sno’s eyes it seems there are so many grey areas of friendships which she finds very overwhelming and confusing with lots of rules to follow that she doesn’t quite grasp; but with Wilding she doesn’t understand that you can’t just rock up to a stranger and sit in their lap because you think they look nice. She also doesn’t understand that sure, that man over there may be incredibly overweight but it’s probably not the nicest thing for him to hear you commenting on how he may break the chair soon if he doesn’t get up. I’ve also had a situation where she didn’t want to be friends with someone because (and she vocalised this in front of the child) their hat was the colour of vomit. Ahem… yep.

In Sno’s eyes it seems there are so many grey areas of friendships which she finds very overwhelming and confusing with lots of rules to follow that she doesn’t quite grasp; but with Wilding she doesn’t understand that you can’t just rock up to a stranger and sit in their lap because you think they look nice. She also doesn’t understand that sure, that man over there may be incredibly overweight but it’s probably not the nicest thing for him to hear you commenting on how he may break the chair soon if he doesn’t get up. I’ve also had a situation where she didn’t want to be friends with someone because (and she vocalised this in front of the child) their hat was the colour of vomit. Ahem… yep.

There are so many situations in daily life that neurotypical people do without even thinking or putting in much of a concerted effort to achieve. Situations like understanding what to say to someone who may be feeling sad; how to comfort someone who isn’t feeling well, how to make a new friend, what to say to someone when they pay you a compliment. All these sort of situations are answered and managed without hesitation for someone who isn’t autistic but for someone who is; they can require a lot of effort and forethought and this can be pretty daunting.

All these sort of situations are answered and managed without hesitation for someone who isn’t autistic but for someone who is; they can require a lot of effort and forethought and this can be pretty daunting.

Teaching appropriate social conduct can be really tricky and requires patience. With Sno it often helps to do “Comic Strip Conversations” to break down social situations and enable her to see what others may be feeling at the same time as her during a social situation that she doesn’t understand. I have also found these books to be really helpful for Sno because they help simplify stuff and give her tools she can add to her toolbox and use when she feels the need. I know for Sno that she loves to read and also loves logic and things that make sense so books which give a series of answers can really help her feel better equipped to deal with situations she feels a bit lost in.

Things that have helped Wilding is learning about emotions and facial expressions and thinking out loud about how what we say might make someone else feel. Daniel Tiger is also fantastic because the episodes are essentially broken down social stories explaining different things ranging from eating, getting dressed, going out and feeling sad. Oh and Daniel Tiger also has a terrific App which explores feelings, too. This book helped Wilding grasp the concept of personal space, too. And hula hoops provide a great clear visual surrounding what personal space is in a tangible way. We use them a lot when we eat outside!

Daniel Tiger is also fantastic because the episodes are essentially broken down social stories explaining different things ranging from eating, getting dressed, going out and feeling sad. Oh and Daniel Tiger also has a terrific App which explores feelings, too. This book helped Wilding grasp the concept of personal space, too. And hula hoops provide a great clear visual surrounding what personal space is in a tangible way. We use them a lot when we eat outside!

Being “shy” or “outgoing” are not the defining factors of autism. People on the spectrum can be both and so many times, they’re hiding in plain sight – if only people were aware of just how wrong these myths surrounding being autistic were.

We see you, girls. Or I do, anyway. And I think you’re pretty incredible.

About the Author

Hello! I’m Jessica. I’m the passionate, honest Writer and Owner of GirlTribe. I live on the beautiful Sunshine Coast with my wonderful husband and our four spirited daughters. Two of our daughters have autism (ASD) along with my husband and two of our daughters don’t. They’re all wonderful. Together we are raising strong daughters who we encourage to question the status quo and challenge gender stereotypes. We want our girls to be bold in their rhythm and embrace difference and neuro-diversity. I really enjoy eating cornchips, fitting in yoga where I can, cooking delicious curries and getting beach therapy whenever I can. I hate coriander and general ignorance.

Two of our daughters have autism (ASD) along with my husband and two of our daughters don’t. They’re all wonderful. Together we are raising strong daughters who we encourage to question the status quo and challenge gender stereotypes. We want our girls to be bold in their rhythm and embrace difference and neuro-diversity. I really enjoy eating cornchips, fitting in yoga where I can, cooking delicious curries and getting beach therapy whenever I can. I hate coriander and general ignorance.

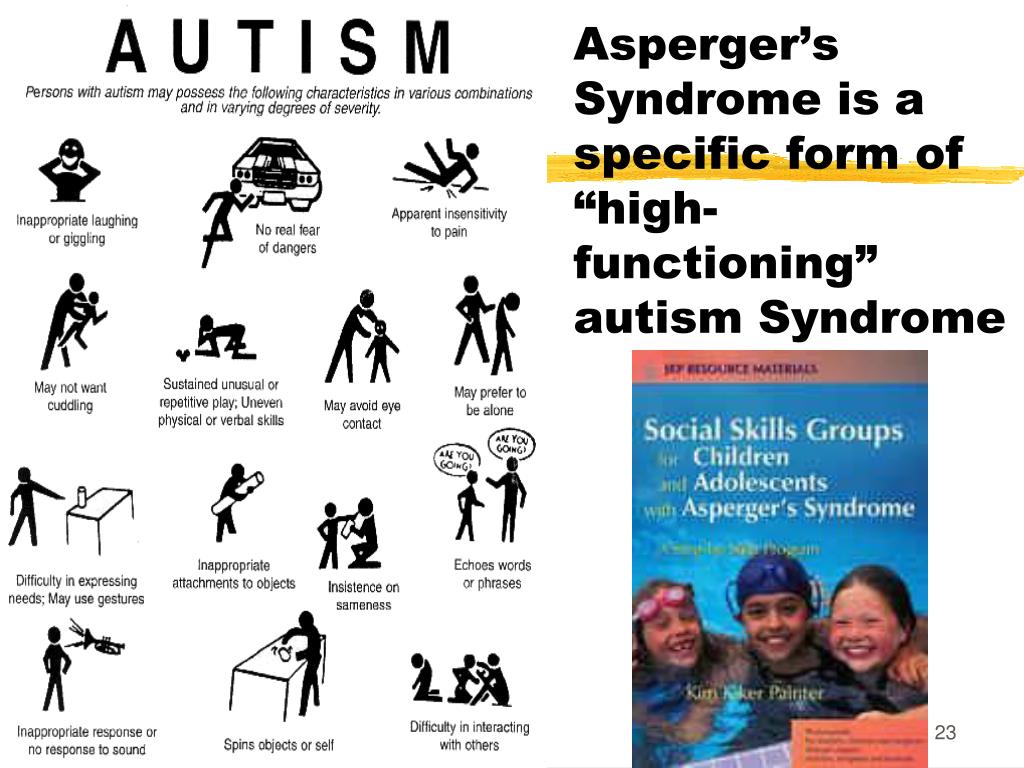

Why is it so hard to live with "high functioning" autism?

5/27/15

ASD expert on the myths and challenges of high functioning autism

Author: Lisa Jo Rudy

Source:

The spectrum of autism is very wide. If you think of it as a rainbow (or bell curve), you will notice that a significant proportion of the people on the spectrum do not belong to one side or the other - they are somewhere in the middle. Of course, at this point in history we don't have evidence that MOST people on the autism spectrum are "somewhere in between," but it's clear that the media tends to focus on only the two extremes of autism - the most severely disabled and the most highly functioning people.

Of course, at this point in history we don't have evidence that MOST people on the autism spectrum are "somewhere in between," but it's clear that the media tends to focus on only the two extremes of autism - the most severely disabled and the most highly functioning people.

If you look at autism through the eyes of journalists, high-functioning autism is a bunch of eccentric geniuses. Often mentioned are Bill Gates, Albert Einstein, as well as actors Dan Ackroyd and Daryl Hannah. In other words, we are talking about people who simply stand out from the background of others. However, in real life, the concept of "high-functioning autistic" rarely coexists with such epithets as "genius", "business tycoon" and "Hollywood star".

In fact, people with high-functioning autism may be no more intelligent than their typical peers. And they may completely lack the motivation to achieve public recognition, which at one time forced Bill Gates to look for investors, and Einstein to publish an article.

They may also experience significant difficulties in daily activities, employment or personal life, and this often leads to low self-esteem. These problems are greatly exacerbated by the fact that others constantly react to them with bewilderment or indignation. The reason is that in many situations people with high-functioning autism "pass for normal" and are not expected to behave or respond in an unusual way.

Also, people with more severe autism are not usually required to "just pull themselves together and act normal" in difficult situations for them, but people on the higher end of the spectrum are often expected to do just that.

Finally, people with high-functioning autism tend to be very aware of their own difficulties and may be very distressed by the negative reactions of others.

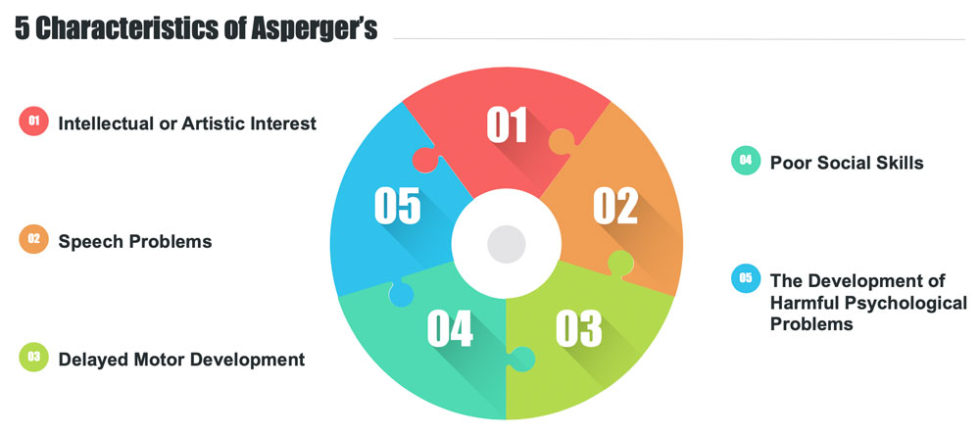

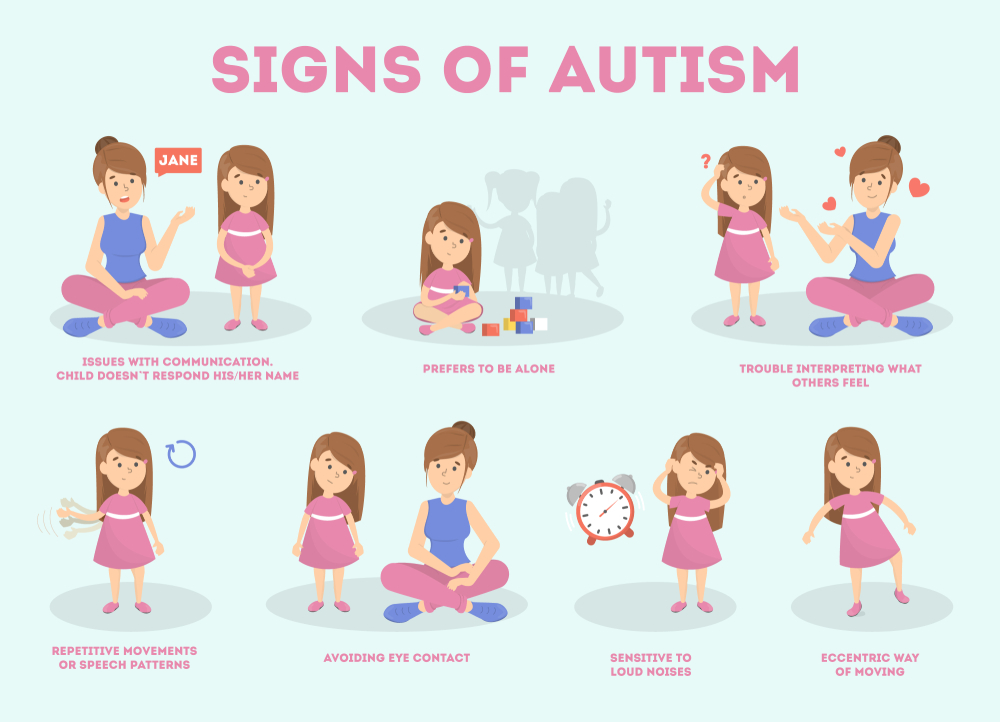

Here are just a few common problems people with high functioning autism (including those diagnosed with Asperger's syndrome) often get in the way of their success and happiness:

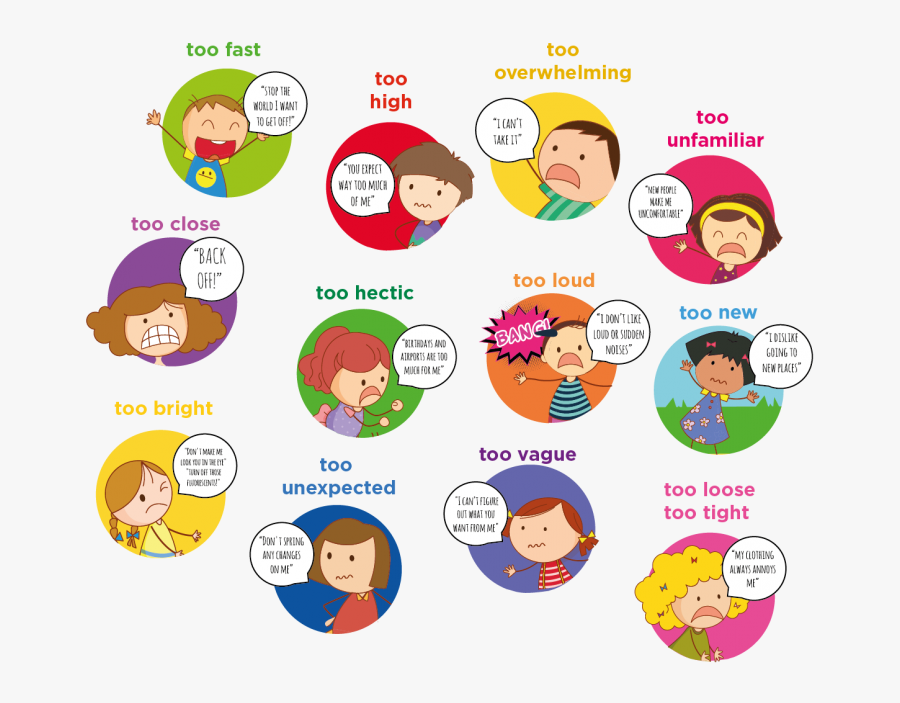

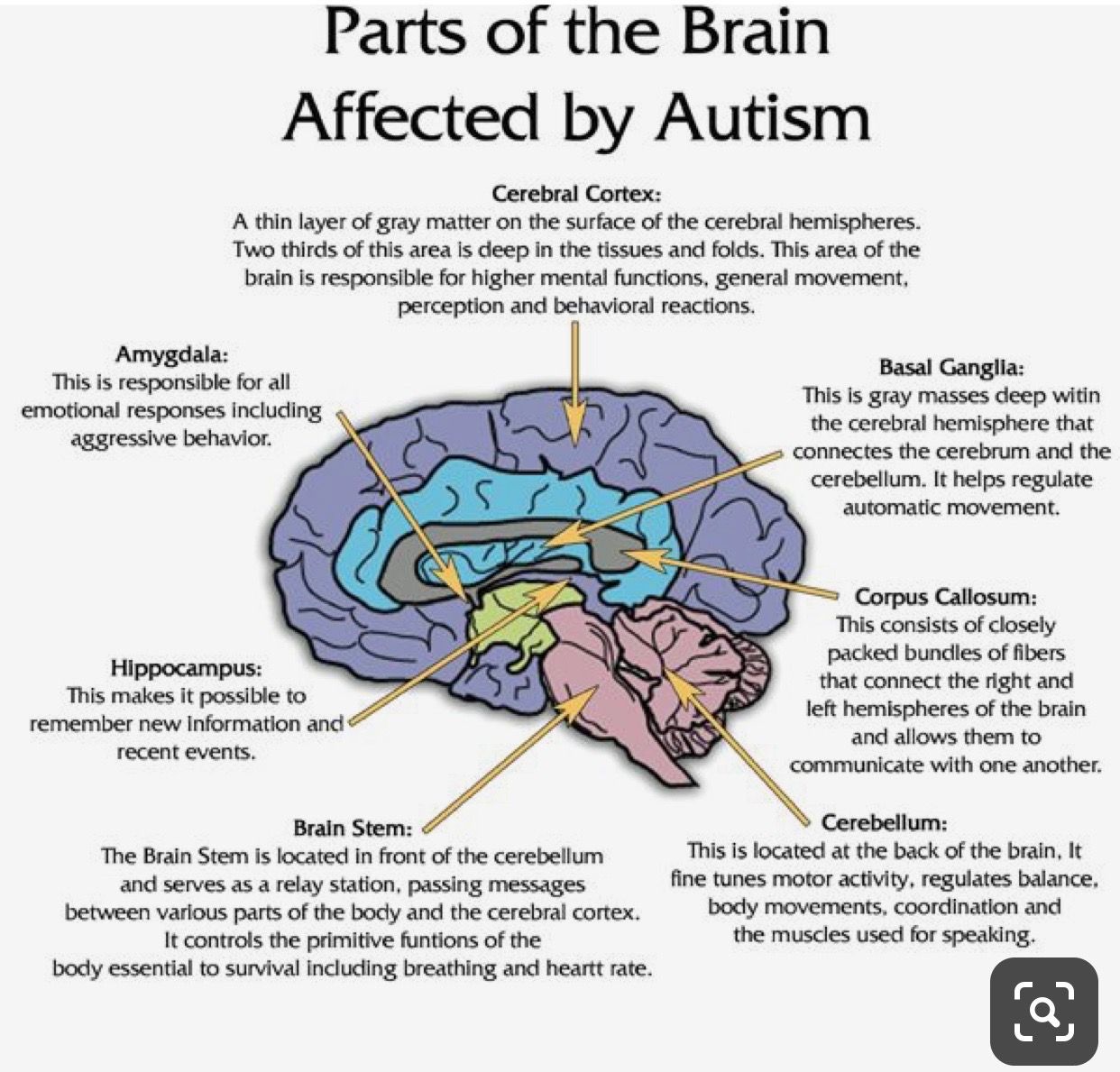

Severe sensory impairment. People with high functioning autism, like everyone on this spectrum, are susceptible to sensory processing disorders. This can include mild to severe hypersensitivity to noise, crowds, bright lights, certain tastes, strong smells, and touch. In practice, this means that even a very gifted and eloquent person may be completely unable to enter a crowded restaurant, go to a movie, or endure going to a supermarket, a stadium, or other public places.

People with high functioning autism, like everyone on this spectrum, are susceptible to sensory processing disorders. This can include mild to severe hypersensitivity to noise, crowds, bright lights, certain tastes, strong smells, and touch. In practice, this means that even a very gifted and eloquent person may be completely unable to enter a crowded restaurant, go to a movie, or endure going to a supermarket, a stadium, or other public places.

Social blindness. What is the difference between a polite greeting and a light flirt? How do you know if you're talking too loudly? When is it okay to talk about personal problems or interests, and when is it best to refrain from doing so? When is it important to stop doing what you enjoy and focus on the needs of the other person? Most people have trouble answering these questions, but if you have high-functioning autism, they can become insurmountable barriers to communication, employment, and romance.

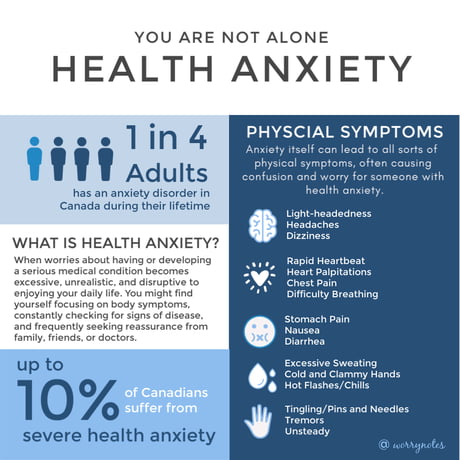

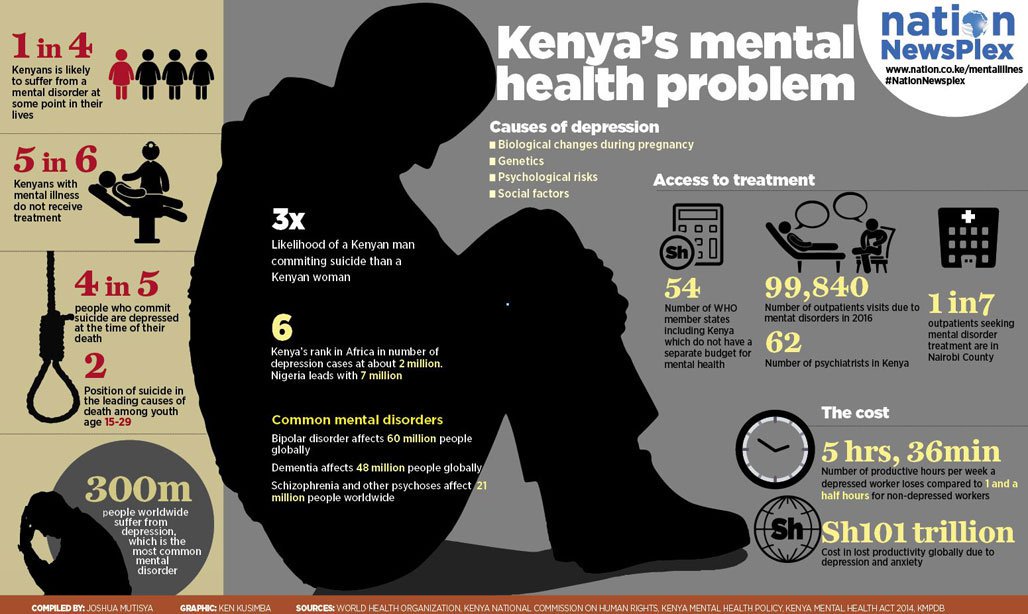

Anxiety and depression. Anxiety disorders, depression, and other emotional disturbances are much more common in people with high-functioning autism than in the general population. We don't know if autism leads to these disorders, or if it's just a natural consequence of frequent failure and social rejection. But whatever the cause, emotional disturbances can be disabling in and of themselves.

Anxiety disorders, depression, and other emotional disturbances are much more common in people with high-functioning autism than in the general population. We don't know if autism leads to these disorders, or if it's just a natural consequence of frequent failure and social rejection. But whatever the cause, emotional disturbances can be disabling in and of themselves.

Lack of skills in planning one's actions. The skills we use to organize and plan our lives are called executive functions. They allow NT adults to plan ahead for their daily routine, notice when they run out of shampoo and buy more on the way home, or plan work on a complex long-term project. Most people with high-functioning autism have very severe executive dysfunction. As a result, it is extremely difficult for them to cope with household chores, the slightest change in their usual routine can be a disaster for them, and so on.

Problems of emotional regulation. Contrary to popular belief, people with autism do not suffer from lack of emotion. Moreover, people with autism can become overly emotional in inappropriate situations. Imagine a teenager crying over a change in plans, or a grown woman having a tantrum because her car wouldn't start. These are examples of typical problems for people with high functioning autism that can be very successful, but ONLY in predictable situations without unexpected obstacles.

Moreover, people with autism can become overly emotional in inappropriate situations. Imagine a teenager crying over a change in plans, or a grown woman having a tantrum because her car wouldn't start. These are examples of typical problems for people with high functioning autism that can be very successful, but ONLY in predictable situations without unexpected obstacles.

Problems with changes and transitions. Many neurotypicals find it difficult to adapt to change, but for people with high-functioning autism, this is a problem on a completely different level. Once a familiar and comfortable routine has been established, people with autism generally want to keep that routine forever. An autistic adult can go out with friends every Wednesday for nachos without any problems, but the idea of going out on Thursdays for chicken wings instead can cause a panic attack and even anger.

Difficulties with oral speech perception. A person with high-functioning autism may be ready to do a task given to him brilliantly, but if the instructions were given to him orally, then there is a risk that he simply will not be able to follow them. For example, if a police officer says "stay in the car and hand me your papers," a person with autism might only make out "stay in the car" or only "hand over the papers." The same may apply to instruction in the classroom, in the doctor's office, or in the workplace. As you might guess, this often leads to all sorts of difficulties, ranging from problems with the police to unintentional mistakes at work.

For example, if a police officer says "stay in the car and hand me your papers," a person with autism might only make out "stay in the car" or only "hand over the papers." The same may apply to instruction in the classroom, in the doctor's office, or in the workplace. As you might guess, this often leads to all sorts of difficulties, ranging from problems with the police to unintentional mistakes at work.

As you can see, the term "highly functional" means just that. However, this does not mean that high-functioning autism is an “easy” diagnosis. It is important for loved ones, employers, teachers, or others who interact with people on the high end of the autism spectrum to remember that autism is autism.

We hope that the information on our website will be useful or interesting for you. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

Autism in Adults, Research

5 Reasons Why Symptoms of High-Functioning Autism May Not be Noticed • Autism is

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) can be diagnosed at 1-3 years of age, but often overlooked or misunderstood by professionals and parents interpret his symptoms. The more high-functioning, milder form of autism (Asperger's syndrome) is especially often overlooked. In this case, the diagnosis is usually not made until school age, and it is not uncommon for such autism to be diagnosed only in adolescence or adulthood.

The more high-functioning, milder form of autism (Asperger's syndrome) is especially often overlooked. In this case, the diagnosis is usually not made until school age, and it is not uncommon for such autism to be diagnosed only in adolescence or adulthood.

Even if the diagnosis was made late, this does not mean that the symptoms of autism appeared at this age, they were present from early childhood. Moreover, it is an official and mandatory criterion for diagnosing autism - symptoms must be present from early preschool age. Listed below are several factors that contribute to the fact that the symptoms of high-functioning autism can be ignored for a long time.

1. Camouflage, masking symptoms

People with high functioning autism (Asperger's syndrome) do not have intellectual difficulties, some of them even have unusually high intelligence. This may lead them to learn to camouflage, that is, whether consciously or not, to mask or hide the manifestations of autism.

This child may have behavioral problems and unusual features. But at the same time, his or her ability to understand academic subjects well, high IQ test scores, and a large vocabulary can lead educators and parents to start looking for other, incorrect explanations for these problems. Even doctors often miss the manifestations of autism if a child can use spoken language well.

Often these children's strengths help them cope more or less normally in kindergarten or elementary school, where they have only minor problems. But in middle school, learning tasks become more abstract, require more advanced speech skills, and social interaction becomes more and more multifaceted. At this age, the initial symptoms of autism begin to get more attention as the child has more problems as demands increase.

Also, many people with high-functioning autism develop skills in how to hide, compensate for, or temporarily suppress the manifestations of autism. If they are often told to “look in the eyes”, “don’t sway” or “don’t shake your hands”, don’t talk too much on the same topic, they may begin to hide these symptoms in the presence of strangers, and also begin to withhold information that may indicate autism.

If there are no obvious external symptoms of autism, then this makes diagnosis much more difficult.

2. Misdiagnosis in early childhood

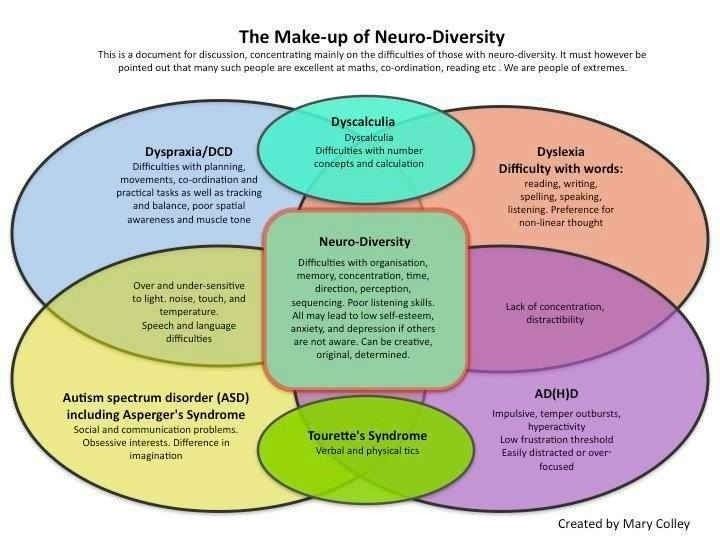

It is not uncommon for children with high-functioning autism to be misdiagnosed, or to be correctly diagnosed with a co-morbid disorder but the associated autism not noticed. As a result, all the child's problems begin to be attributed to this other diagnosis. Children with high-functioning autism are often diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), social phobia, and other developmental or mental health problems.

If a child has a different diagnosis, they may not be diagnosed with autism until adulthood.

According to one 2019 study, 10.3% of adults with autism were misdiagnosed with ADHD as children, while 12.1% of children diagnosed with ADHD were subsequently diagnosed with autism. These data are not surprising when one considers that one in three autistic children have serious attention deficits.

3. Age

For adults, the explanation may simply be that, in their childhood, diagnostic criteria did not yet include more high-functioning forms of autism.

Asperger's Syndrome only appeared in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1994, even though there were many children with symptoms of high-functioning autism prior to that year. In 2013, the fifth version of the guidelines was published, in which Asperger's syndrome disappeared as a diagnosis, and it was replaced by level 1 autism spectrum disorder.

Usually these people received other diagnoses, as autism was considered too extreme a diagnosis for a person with a normal level of intelligence and well-developed speech. Often these people did not seek diagnosis in adulthood, so now more and more autism is being diagnosed in middle-aged and even older people.

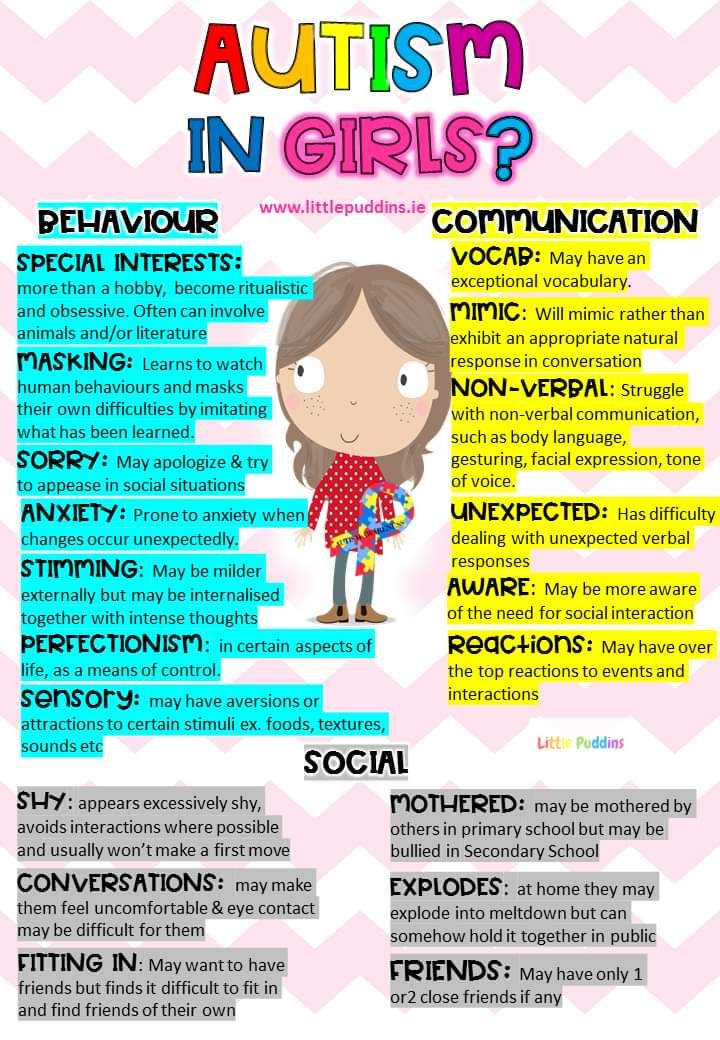

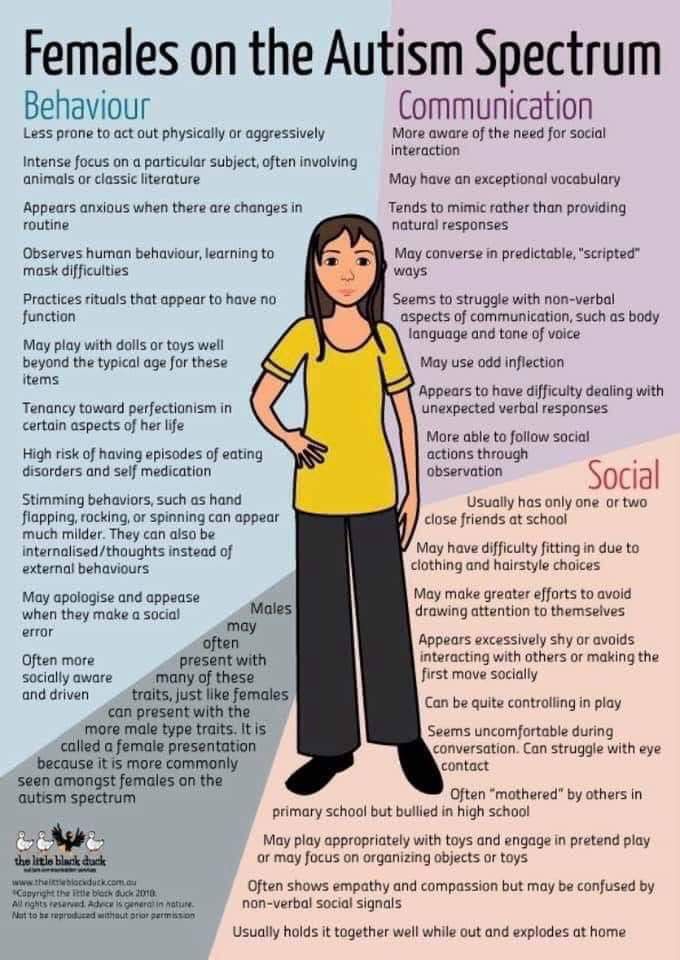

4. Female

Some studies have shown that girls and women are particularly likely to miss high-functioning autism. Overall, autism is four times more likely to be diagnosed in boys and men than in women and girls, although the reasons for this are unclear.

Overall, autism is four times more likely to be diagnosed in boys and men than in women and girls, although the reasons for this are unclear.

Are girls less likely to be autistic? There is evidence that their behavior (discomfort in social situations, problems with motor coordination, avoidance of large groups of people) can be considered feminine, and therefore less likely to be seen as a problem.

On the other hand, there is evidence that girls with high-functioning autism may behave differently than autistic boys: they are less aggressive, more likely to imitate other people, and make more efforts to fit in with their peers.

One 2015 study found that women may have more genetic immunity to some manifestations of autism (this theory is called the female protective effect). According to this theory, the symptoms of autism manifest differently in women and girls, and therefore they may have more functional social behavior than autistic boys.

While more research is needed to understand the causes, it is now clear that female gender in autism greatly reduces the likelihood of a correct diagnosis.

5. Family income and ethnicity

Statistically, children from poor families and/or ethnic minorities are much less likely to be diagnosed with autism. This is due to two main reasons.

Firstly, it is obvious that if people have little money, they do not have the opportunity to take their child to paid consultations with specialists, go to another region or city for diagnostics, or find additional classes for early help. This is especially true in cases where the child does not have severe speech delay and the most severe symptoms of autism. As a result, the lower the income of the family, the less likely it is to be correctly diagnosed and the worse the prognosis for autistic children who have been diagnosed.

The second reason is related to different cultural characteristics. For example, in some ethnic communities, behavioral manifestations of high-functioning autism are not considered particularly problematic, or, conversely, any impairment in a child is considered completely unacceptable, and parents may avoid diagnosis and hide the characteristics of the child.