Genito pelvic pain

Genito Pelvic Pain Penetration Disorder

There’s a new diagnostic name on the street for pelvic pain, and it’s a long one. Genito pelvic pain/penetration disorder (GPPPD) is a combination of painful sex (dyspareunia) and involuntary vaginal muscle spasms (vaginismus).

Used to describe persistent or recurrent difficulties when it comes to sexual dysfunction, it’s diagnosed by extreme pain or ongoing discomfort, usually while trying to have sex. It causes emotional distress and a (totally understandable!) loss of interest in sex and reduced sexual desire.

Everyone’s experience of genito pelvic pain and penetration disorder is unique. And it often occurs among women in early adulthood or during peri- and postmenopause.

Symptoms can come about at the first experience of vaginal intercourse, or can (annoyingly!) begin after you’ve been enjoying pain-free sexual intercourse for some time.

Like many sexual pain disorders, most people with GPPPD have complex, multifaceted symptoms and it’s often a tough challenge for professionals to assess and treat.

If you’re reading this you’re probably wondering what the systems of genito pelvic pain and penetration disorder are:

- Difficulties with vaginal penetration during sex

- Pelvic or vulva pain during sex or at other attempts to penetrate

- Apprehension about pain before, during or after sex

- Consciously or unconsciously tensing or tightening the pelvic muscles during sex

How is genito pelvic pain and penetration disorder different from other conditions like dyspareunia or vaginismus?

Many practice professionals believe there are distinct differences between dyspareunia and vaginismus and they shouldn’t be lumped together under one umbrella term as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Revision 5 (or DSM-5) now does with “genito-pelvic penetration/pain disorder”.

However, in order to be diagnosed with GPPPD, you need to have experienced persistent symptoms for six months or more.

You also need to rule out other physiological and psychological health issues like relationship problems, effects of medication and other medical conditions, including mental disorders like Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Due to this, by the time you get a diagnosis you’ve probably been suffering a while. But don’t let it get you down, there is a treatment plan out there waiting for you!

Due to this, by the time you get a diagnosis you’ve probably been suffering a while. But don’t let it get you down, there is a treatment plan out there waiting for you!

What causes it?

While experts haven’t yet worked out how genito pelvic pain penetration disorder develops, there are a few things they think are the main causes, including:

- Medical reasons, such as an infection or condition in the genito pelvic region

- Cultural or religious beliefs around sex and sexuality

- Relationship issues around sex and sexual intercourse

- A history of sexual abuse or poor body image

What can I do about it?

The manta of “No pain, no gain” does not apply to this situation and even if you can "handle it," your body remembers. It’s important to be aware that “pushing through pain” during attempted vaginal penetration may create more problems.

You don’t have to live with painful sex and you can get help. If you think something might be going janky with your pelvic floor your first step is to find an awesome pelvic health specialist who’ll help you get to the bottom of your issues (like a physiotherapist or gynecologist).

If you think something might be going janky with your pelvic floor your first step is to find an awesome pelvic health specialist who’ll help you get to the bottom of your issues (like a physiotherapist or gynecologist).

Because it’s such a complex area, many people with genito pelvic pain and penetration disorder actually find that they need a combination of treatments, from a variety of experts, to see improvement in their condition. Think of it as building a team of awesome people who have your health as their top priority. Keep asking for help until you find the right team to give you the support and treatment options you need.

What does a specialist appointment look like for genito pelvic pain and penetration disorder?

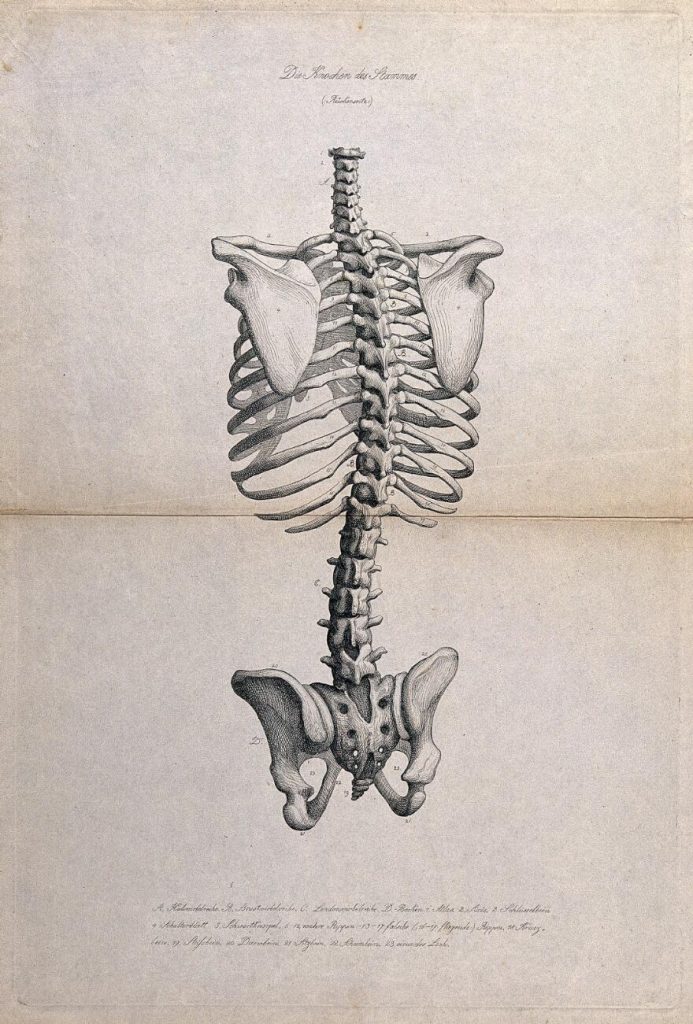

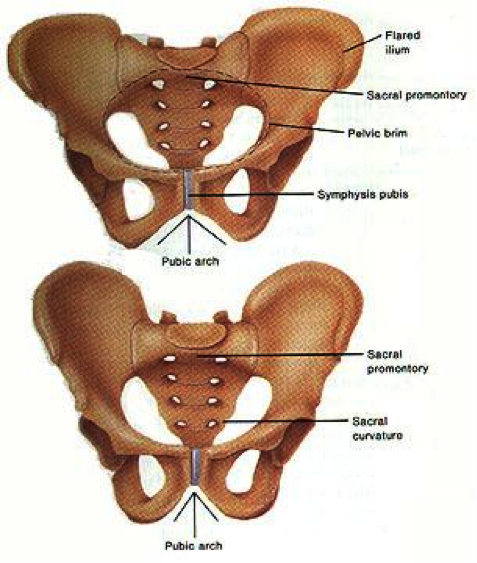

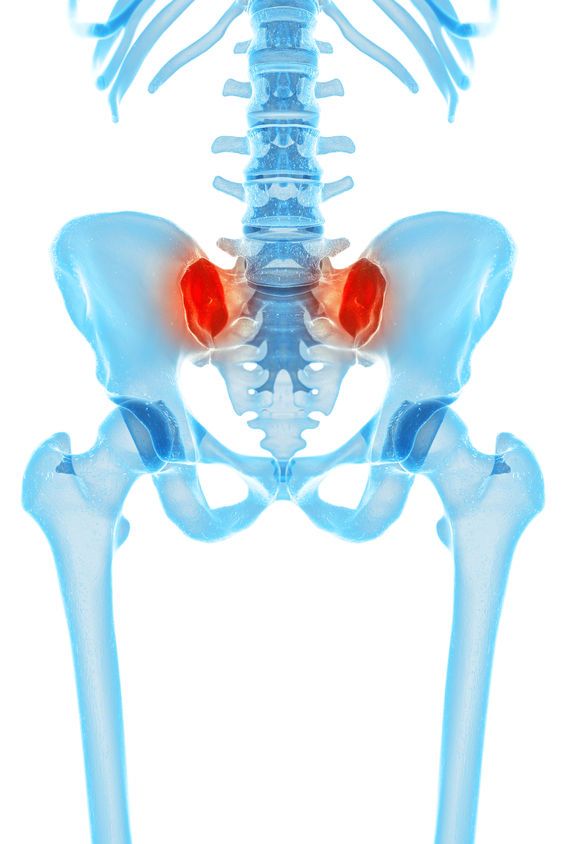

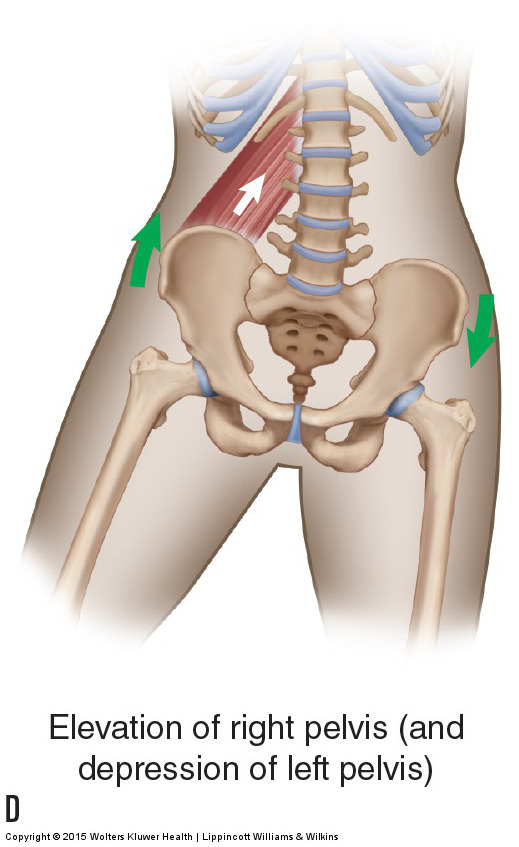

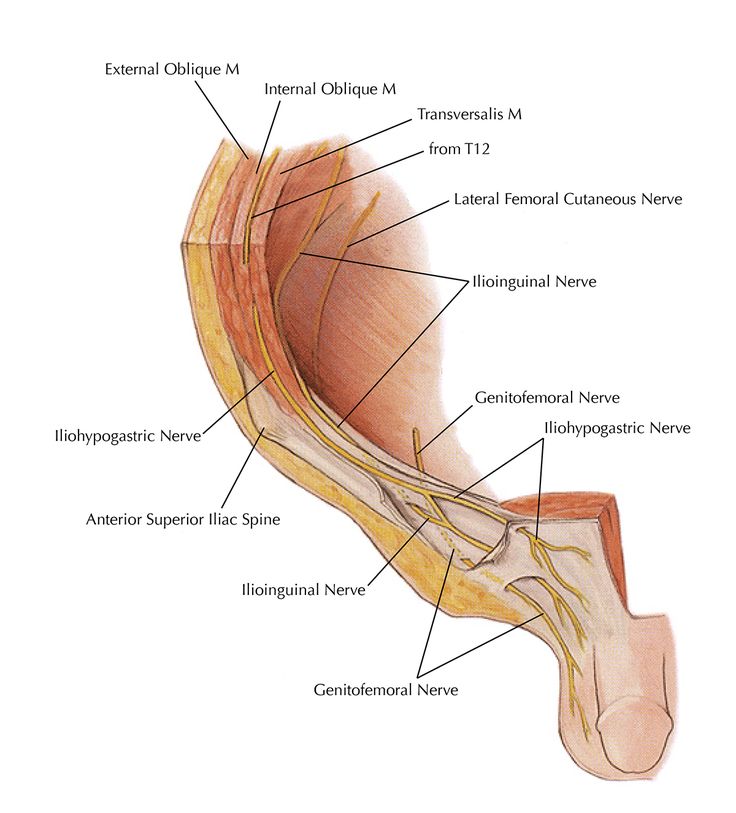

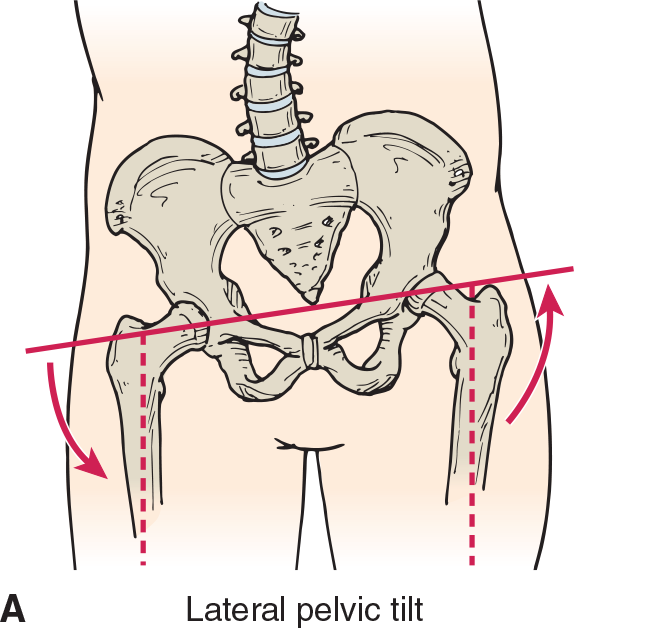

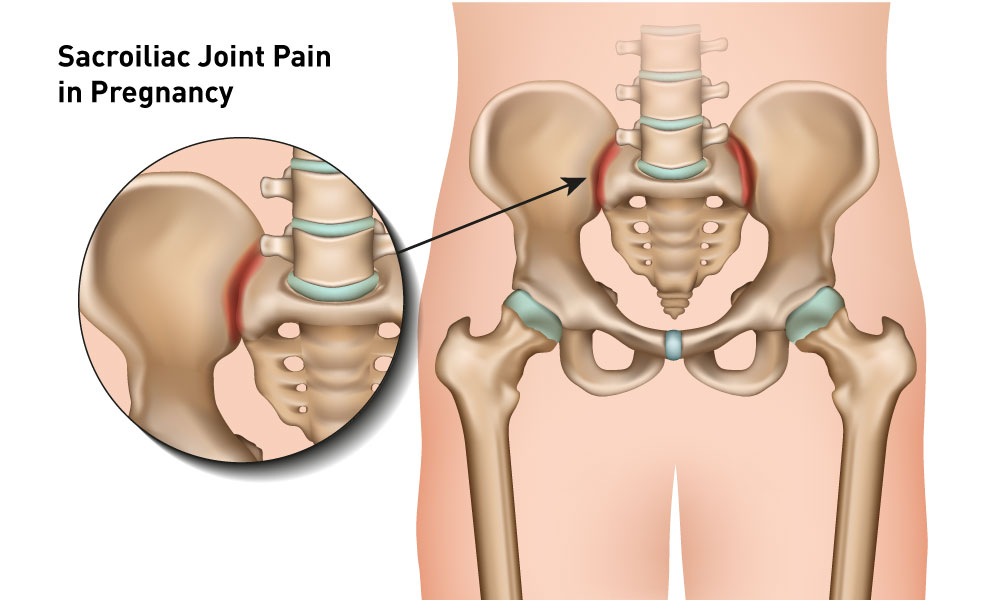

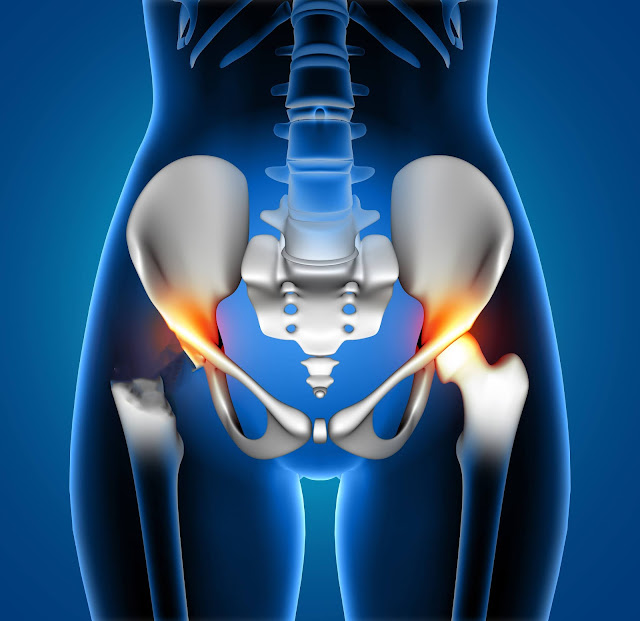

Your specialist will give you a thorough check over and assess where your body, including your pelvic floor muscles. During your assessment you’ll get an internal and external examination to check the function of your pelvic floor muscles. Your specialist will check how you contract and relax the muscles and will feel for any tight spots or trigger points. They might also check how the bones and muscles of your ribs, lower back, hips and sacroiliac joints are working, as it’s all connected.

They might also check how the bones and muscles of your ribs, lower back, hips and sacroiliac joints are working, as it’s all connected.

Have you been suggested vaginal training or dilation therapy?

Vaginal trainers help your body to relax and work to desensitize your vulvar and vaginal area. This can make it easier (and less painful) to have sex and use tampons. Dilation therapy, on the other hand, helps to gently stretch your vaginal walls and tissue to reduce sexual pain upon insertion.

We can’t rave enough about the silicone dilators from Intimate Rose for both vaginal training and dilation. After trying many (many) dilators, these are our number one choice for genito pelvic pain and penetration disorder. They’re also perfect for dyspareunia, vaginismus, menopause, post-radiation therapy and more.

Does your vagina feel dry or fragile?

One of the biggest causes of pain or discomfort during sex is not enough lubrication. Dry vaginal walls cause friction, and friction isn’t fun for anyone.

Your body produces its own natural lubrication when you’re turned on. But how wet you get isn’t just about desire. Things like medication, age, breastfeeding and hormonal fluctuations can all have an impact on the amount of natural lubrication your body produces. While extended foreplay can help (and is loads of fun) if you’re worried about how wet you are it can be a real buzz kill.

Here’s where a good lubrication can help. Not all lubricants are not created equal. We have lubricants and vaginal moisturizers from Intimate Rose, for genito pelvic pain and penetration disorder to get things feeling better again. They’re natural, nurturing and made from the highest quality ingredients to help you feel good about using a tampon, toy, your partner’s penis, or vaginal dilators.

Provide comfort to your pelvic area

Our TendHer reusable perineal cooling pads are super soft (like super soft) and perfect for cooling hypersensitive and delicate areas of a woman’s body. Comfortable, cooling and discreet. No-one will know you are wearing it— it can be our little secret. Bonus! You can also use TendHer pads warm to help relieve muscle spasms or to relax the area prior to vaginal training, dilation or trigger point therapy.

No-one will know you are wearing it— it can be our little secret. Bonus! You can also use TendHer pads warm to help relieve muscle spasms or to relax the area prior to vaginal training, dilation or trigger point therapy.

Gain control and begin to enjoy sex again

Using an intimate wearable that allows you to control the depth of penetration during sex can help you manage, or even eliminate, pain. The Ohnut is designed to feel just like skin. It’s so comfortable (like a gentle hug) you and your partner will barely notice it’s there. And because you no longer have to worry about whether penetration will hurt, the Ohnut allows both you and your partner to focus on what matters most, connection, enjoyment and fun. Want to know what it feels like for the guy? Check out the video via our shop.

While a diagnosis of genito pelvic pain penetration disorder is one that no one wants to recieve, don’t lose heart! With the right team of medical professionals and tools, you’ll be moving in the right direction towards healing, in no time!

Efficacy of Internet-Based Guided Treatment for Genito-Pelvic Pain/Penetration Disorder: Rationale, Treatment Protocol, and Design of a Randomized Controlled Trial

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed Washington: American Psychiatric Association; (2013). [Google Scholar]

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed Washington: American Psychiatric Association; (2013). [Google Scholar]

2. Carvalho J, Vieira AL, Nobre P. Latent structures of female sexual functioning. Arch Sex Behav (2012) 41:907–17. 10.1007/s10508-011-9865-7 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Lahaie MA, Amsel R, Khalifé S, Boyer S, Faaborg-Andersen M, Binik YM. Can fear, pain, and muscle tension discriminate vaginismus from dyspareunia/provoked vestibulodynia? Implications for the new DSM-5 diagnosis of genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder. Arch Sex Behav (2015) 44:1537–50. 10.1007/s10508-014-0430-z [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Hayes RD, Bennett CM, Fairley CK, Dennerstein L. What can prevalence studies tell us about female sexual difficulty and dysfunction? J Sex Med (2006) 3:589–95. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00241.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Latthe P, Latthe M, Say L, Gülmezoglu M, Khan KS. WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity. BMC Public Health (2006) 6:177. 10.1186/1471-2458-6-177 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity. BMC Public Health (2006) 6:177. 10.1186/1471-2458-6-177 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Christensen BS, Grønbaek M, Osler M, Pedersen BV, Graugaard C, Frisch M. Sexual dysfunctions and difficulties in Denmark: prevalence and associated sociodemographic factors. Arch Sex Behav (2011) 40:121–32. 10.1007/s10508-010-9599-y [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Peixoto MM, Nobre P. Prevalence and sociodemographic predictors of sexual problems in Portugal: a population-based study with women aged 18 to 79 years. J Sex Marital Ther (2015) 41:169–80. 10.1080/0092623X.2013.842195 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Smith AM, Lyons A, Ferris JA, Richters J, Pitts MK, Shelley JM, et al. Incidence and persistence/recurrence of women’s sexual difficulties: findings from the Australian longitudinal study of health and relationships. J Sex Marital Ther (2012) 38:378–93. 10.1080/00224499.2011.598247 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1080/00224499.2011.598247 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Öberg K, Fugl-Meyer A, Fugl-Meyer K. On categorization and quantification of women’s sexual dysfunctions: an epidemiological approach. Int J Impot Res (2004) 16:261–9. 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901151 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Hendrickx L, Gijs L, Enzlin P. Distress, sexual dysfunctions, and DSM: dialogue at cross purposes? J Sex Med (2013) 10:630–41. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02971.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Hayes RD, Bennett CM, Dennerstein L, Taffe JR, Fairley CK. Are aspects of study design associated with the reported prevalence of female sexual difficulties? Fertil Steril (2008) 90:497–505. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1297 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Hayes RD, Dennerstein L, Bennett CM, Fairley CK. What is the “true” prevalence of female sexual dysfunctions and does the way we assess these conditions have an impact? J Sex Med (2008) 5:777–87. 10.1111/j.1743-6109. 2007.00768.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2007.00768.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Ponte M, Klemperer E, Sahay A, Chren M-M. Effects of vulvodynia on quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol (2009) 60:70–6. 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.032 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Arnold LD, Bachmann GA, Rosen R, Kelly S, Rhoads GG. Vulvodynia: characteristics and associations with comorbidities and quality of life. Obstet Gynecol (2006) 107:617–24. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000199951.26822.27 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Iglesias-Rios L, Harlow SD, Reed BD. Depression and posttraumatic stress disorder among women with vulvodynia: evidence from the population-based woman to woman health study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) (2015) 24:557–62. 10.1089/jwh.2014.5001 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Khandker M, Brady SS, Vitonis AF, MacLehose RF, Stewart EG, Harlow BL. The influence of depression and anxiety on risk of adult onset vulvodynia. J Womens Health (Larchmt) (2011) 20:1445–51. 10.1089/jwh.2010.2661 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1089/jwh.2010.2661 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Shindel AW, Eisenberg ML, Breyer BN, Sharlip ID, Smith JF. Sexual function and depressive symptoms among female north American medical students. J Sex Med (2011) 8:391–9. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02085.x [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Cherner RA, Reissing ED. A comparative study of sexual function, behavior, and cognitions of women with lifelong vaginismus. Arch Sex Behav (2013) 42:1605–14. 10.1007/s10508-013-0111-3 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Farmer MA, Meston CM. Predictors of genital pain in young women. Arch Sex Behav (2007) 36:831–43. 10.1007/s10508-007-9199-7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Reissing ED, Binik YM, Khalif S, Cohen D, Amsel R. Etiological correlates of vaginismus: sexual and physical abuse, sexual knowledge, sexual self-schema, and relationship adjustment. J Sex Marital Ther (2003) 29:47–59. 10. 1080/00926230390154835 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

1080/00926230390154835 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Landry T, Bergeron S. How young does vulvo-vaginal pain begin? Prevalence and characteristics of dyspareunia in adolescents. J Sex Med (2009) 6:927–35. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01166.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Landry T, Bergeron S. Biopsychosocial factors associated with dyspareunia in a community sample of adolescent girls. Arch Sex Behav (2011) 40:877–89. 10.1007/s10508-010-9637-9 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Granot M, Lavee Y. Psychological factors associated with perception of experimental pain in vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. J Sex Marital Ther (2005) 31:285–302. 10.1080/00926230590950208 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Pazmany E, Bergeron S, Van Oudenhove L, Verhaeghe J, Enzlin P. Body image and genital self-image in pre-menopausal women with dyspareunia. Arch Sex Behav (2013) 42:999–1010. 10.1007/s10508-013-0102-4 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Ayling K, Ussher JM. “If sex hurts, am I still a woman?” The subjective experience of vulvodynia in hetero-sexual women. Arch Sex Behav (2008) 37:294–304. 10.1007/s10508-007-9204-1 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Ayling K, Ussher JM. “If sex hurts, am I still a woman?” The subjective experience of vulvodynia in hetero-sexual women. Arch Sex Behav (2008) 37:294–304. 10.1007/s10508-007-9204-1 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Sadownik LA, Smith KB, Hui A, Brotto LA. The impact of a woman’s dyspareunia and its treatment on her intimate partner: a qualitative analysis. J Sex Marital Ther (2017) 43:529–24. 10.1080/0092623X.2016.1208697 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Pukall CF, Goldstein AT, Bergeron S, Foster D, Stein A, Kellogg-Spadt S, et al. Vulvodynia: definition, prevalence, impact, and pathophysiological factors. J Sex Med (2016) 13:291–304. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2015.12.021 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

28. Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain (2000) 85:317–32. 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00242-0 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Brauer M, Ter Kuile MM, Janssen SA, Laan E. The effect of pain-related fear on sexual arousal in women with superficial dyspareunia. Eur J Pain (2007) 11:788–98. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.12.006 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

The effect of pain-related fear on sexual arousal in women with superficial dyspareunia. Eur J Pain (2007) 11:788–98. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.12.006 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Brauer M, Ter Kuile MM, Laan E. Effects of appraisal of sexual stimuli on sexual arousal in women with and without superficial dyspareunia. Arch Sex Behav (2009) 38:476–85. 10.1007/s10508-008-9371-8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

31. Rosen NO, Rancourt KM, Corsini-Munt S, Bergeron S. Beyond a “woman’s problem”: the role of relationship processes in female genital pain. Curr Sex Health Rep (2014) 6:1–10. 10.1007/s11930-013-0006-2 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. Rancourt KM, Rosen NO, Bergeron S, Nealis LJ. Talking about sex when sex is painful: dyadic sexual communication is associated with women’s pain, and couples’ sexual and psychological outcomes in provoked vestibulodynia. Arch Sex Behav (2016) 45:1933–44. 10.1007/s10508-015-0670-6 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

33. Lemieux AJ, Bergeron S, Steben M, Lambert B. Do romantic partners’ responses to entry dyspareunia affect women’s experience of pain? The roles of catastrophizing and self-efficacy. J Sex Med (2013) 10:2274–84. 10.1111/jsm.12252 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Lemieux AJ, Bergeron S, Steben M, Lambert B. Do romantic partners’ responses to entry dyspareunia affect women’s experience of pain? The roles of catastrophizing and self-efficacy. J Sex Med (2013) 10:2274–84. 10.1111/jsm.12252 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Dogan S, Dogan M. The frequency of sexual dysfunctions in male partners of women with vaginismus in a Turkish sample. Int J Impot Res (2008) 20:218–21. 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901615 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

35. Öberg K, Sjögren Fugl-Meyer K. On Swedish women’s distressing sexual dysfunctions: some concomitant conditions and life satisfaction. J Sex Med (2005) 2:169–80. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.20226.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

36. Bergeron S, Lord M-J. The integration of pelvi-perineal re-education and cognitive behavioural therapy in the multidisciplinary treatment of the sexual pain disorders. Sex Relat Ther (2003) 18:135–41. 10.1080/14681994.2010.496968 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Aerts L, Bergeron S, Pukall CF, Khalifé S. Provoked vestibulodynia: does pain intensity correlate with sexual dysfunction and dissatisfaction? J Sex Med (2016) 13:955–62. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.03.368 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Aerts L, Bergeron S, Pukall CF, Khalifé S. Provoked vestibulodynia: does pain intensity correlate with sexual dysfunction and dissatisfaction? J Sex Med (2016) 13:955–62. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.03.368 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Binik YM, Meana M. The future of sex therapy: specialization or marginalization? Arch Sex Behav (2009) 38:1016–27. 10.1007/s10508-009-9475-9 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Dunkley CR, Brotto LA. Psychological treatments for provoked vestibulodynia: integration of mindfulness-based and cognitive behavioral therapies. J Clin Psychol (2016) 72:637–50. 10.1002/jclp.22286 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

40. Brotto LA, Sadownik L, Thomson S. Impact of educational seminars on women with provoked vestibulodynia. J Obstet Gynaecol Can (2010) 32:132–8. 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34427-9 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

41. Bergeron S, Morin M, Lord M-J. Integrating pelvic floor rehabilitation and cognitive-behavioural therapy for sexual pain: what have we learned and were do we go from here? Sex Relat Ther (2010) 25:289–98. 10.1080/14681994.2010.486398 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1080/14681994.2010.486398 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

42. Günzler C, Berner MM. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions in men and women with sexual dysfunctions – a systematic review of controlled clinical trials. Part 2 – the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med (2012) 9:3108–25. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02970.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

43. Bergeron S, Khalife S, Dupuis M-J, McDuff P. A randomized clinical trial comparing group cognitive-behavioral therapy and a topical steroid for women with dyspareunia. J Consult Clin Psychol (2016) 84:259–68. 10.1037/ccp0000072 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

44. Lester RA, Brotto LA, Sadownik LA. Provoked vestibulodynia and the health care implications of comorbid pain conditions. J Obstet Gynaecol Can (2015) 37:995–1005. 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)30049-4 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

45. Brotto LA, Yong P, Smith KB, Sadownik LA. Impact of a multidisciplinary vulvodynia program on sexual functioning and dyspareunia. J Sex Med (2015) 12:238–47. 10.1111/jsm.12718 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J Sex Med (2015) 12:238–47. 10.1111/jsm.12718 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

46. Bond K, Mpofu E, Millington M. Treating women with genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder: influences of patient agendas on help-seeking. J Fam Med (2015) 2:1–8. [Google Scholar]

47. LePage K, Selk A. What do patients want? A needs assessment of vulvodynia patients attending a vulvar diseases clinic. J Sex Med (2016) 4:e242–8. 10.1016/j.esxm.2016.06.003 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Xie Y, Shi L, Xiong X, Wu E, Veasley C, Dade C. Economic burden and quality of life of vulvodynia in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin (2012) 28:601–8. 10.1185/03007995.2012.666963 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

49. Moreira E, Brock G, Glasser D, Nicolosi A, Laumann E, Paik A, et al. Help-seeking behaviour for sexual problems: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Int J Clin Pract (2005) 59:6–16. 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2004.00382.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

50. Bergvall L, Himelein MJ. Attitudes toward seeking help for sexual dysfunctions among US and Swedish college students. Sex Relat Ther (2014) 29:215–28. 10.1080/14681994.2013.860222 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Bergvall L, Himelein MJ. Attitudes toward seeking help for sexual dysfunctions among US and Swedish college students. Sex Relat Ther (2014) 29:215–28. 10.1080/14681994.2013.860222 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

51. Nguyen RH, Turner RM, Rydell SA, MacLehose RF, Harlow BL. Perceived stereotyping and seeking care for chronic vulvar pain. Pain Med (2013) 14:1461–7. 10.1111/pme.12151 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

52. Donaldson RL, Meana M. Early dyspareunia experience in young women: confusion, consequences, and help-seeking barriers. J Sex Med (2011) 8:814–23. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02150.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

53. Hinchliff S, Gott M. Seeking medical help for sexual concerns in mid- and later life: a review of the literature. J Sex Res (2011) 48:106–17. 10.1080/00224499.2010.548610 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

54. Reinecke A, Schöps D, Hoyer J. Sexuelle Dysfunktionen bei Patienten einer verhaltenstherapeutischen Hochschulambulanz: Häufigkeit, Erkennen, Behandlung. Verhaltenstherapie (2006) 16:166–72. 10.1159/000094747 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Verhaltenstherapie (2006) 16:166–72. 10.1159/000094747 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

55. Andersson G, Titov N. Advantages and limitations of Internet-based interventions for common mental disorders. World Psychiatry (2014) 13:4–11. 10.1002/wps.20083 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

56. Ebert DD, Cuijpers P, Muñoz RF, Baumeister H. Prevention of mental health disorders using internet and mobile-based interventions: a narrative review and recommendations for future research. Front Psychiatry (2017) 8:116. 10.3389/FPSYT.2017.00116 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

57. Andersson E, Walén C, Hallberg J, Paxling B, Dahlin M, Almlöv J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of guided Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med (2011) 8:2800–9. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02391.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

58. Hucker A, McCabe MP. Incorporating mindfulness and chat groups into an online cognitive behavioral therapy for mixed female sexual problems. J Sex Res (2015) 52:1–13. 10.1080/00224499.2014.888388 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J Sex Res (2015) 52:1–13. 10.1080/00224499.2014.888388 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

59. Jones LM, McCabe MP. The effectiveness of an Internet-based psychological treatment program for female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med (2011) 8:2781–92. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02381.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

60. Van Lankveld JJ, ter Kuile MM, de Groot HE, Melles R, Nefs J, Zandbergen M. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for women with lifelong vaginismus: a randomized waiting-list controlled trial of efficacy. J Consult Clin Psychol (2006) 74(1): 168–78. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.168 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

61. Cuijpers P, Marks IM, Van Straten A, Cavanagh K, Gega L, Andersson G. Computer-aided psychotherapy for anxiety disorders: a meta-analytic review. Cogn Behav Ther (2009) 38:66–82. 10.1080/16506070802694776 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

62. Ebert DD, Zarski A-C, Christensen H, Stikkelbroek Y, Cuijpers P, Berking M, et al. Internet and computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in youth: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled outcome trials. PLoS One (2015) 10:e0119895. 10.1371/journal.pone.0119895 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

PLoS One (2015) 10:e0119895. 10.1371/journal.pone.0119895 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

63. Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Lindefors N. Cognitive behavior therapy via the Internet: a systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res (2012) 12:745–64. 10.1586/erp.12.67 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

64. Johansson R, Andersson G. Internet-based psychological treatments for depression. Expert Rev Neurother (2012) 12:861–70. 10.1586/ern.12.63 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

65. Königbauer J, Letsch J, Doebler P, Ebert DD, Baumeister H. Internet- and mobile-based depression interventions for people with diagnosed depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord (2017) 178:131–41. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.021 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

66. Wittchen H-U, Zaudig M, Fydrich T. Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview für DSM-IV. Göttingen: Hogrefe; (1997). [Google Scholar]

67. Zarski AC, Rosenau C, Fackiner C, Berking M, Ebert DD. Internet-based guided self-help for vaginismus results of a randomised controlled proof-of-concept trial. J Sex Med (2017) 14:238–54. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.12.232 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Zarski AC, Rosenau C, Fackiner C, Berking M, Ebert DD. Internet-based guided self-help for vaginismus results of a randomised controlled proof-of-concept trial. J Sex Med (2017) 14:238–54. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.12.232 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

68. Zarski AC, Berking M, Hannig W, Ebert DD. Wenn Geschlechtsverkehr nicht möglich ist: Vorstellung eines internetbasierten Behandlungsprogramms für Genito-Pelvine Schmerz-Penetrationsstörung mit Falldarstellung. Verhaltenstherapie (2018).

69. Jacobson E. Progressive Relaxation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; (1938). [Google Scholar]

70. Albaugh JA, Kellogg-Spadt S. Sensate focus and its role in treating sexual dysfunction. Urol Nurs (2002) 22:402–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Masters W, Johnson V. Sex Therapy on Its 25th Anniversary: Why It Survives. St Louis: Masters and Johnson Institute; (1986). [Google Scholar]

72. Heber E, Lehr D, Ebert DD, Berking M, Riper H. Web-based and mobile stress management intervention for employees: A randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res (2016) 18:e21. 10.2196/jmir.5112 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J Med Internet Res (2016) 18:e21. 10.2196/jmir.5112 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

73. Ter Kuile MM, Van Lankveld JJ, De Groot E, Melles R, Neffs J, Zandbergen M. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for women with lifelong vaginismus: process and prognostic factors. Behav Res Ther (2007) 45:359–73. 10.1016/j.brat.2006.03.013 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

74. Klaassen M, Ter Kuile MM. Development and initital validation of the vaginal penetration cognition questionnaire (VPCQ) in a sample of women with vaginismus and dyspareunia. J Sex Med (2009) 6:1617–27. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01217.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

75. Berner MM, Kriston L, Zahradnik H-P, Härter M, Rohde A. Überprüfung der Gültigkeit und Zuverlässigkeit des Deutschen Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI-d). Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd (2004) 64:293–303. 10.1055/s-2004-815815 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

76. Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther (2000) 26:191–208. 10.1080/009262300278597 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther (2000) 26:191–208. 10.1080/009262300278597 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

77. Ter Kuile MM, Brauer M, Laan E. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) and the female sexual distress scale (FSDS): psychometric properties within a Dutch population. J Sex Marital Ther (2006) 32:289–304. 10.1080/00926230600666261 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

78. Attkisson CC, Zwick R. The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric porperties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval Program Plann (1982) 5:233–7. 10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-X [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

79. Boß L, Lehr D, Reis D, Vis C, Riper H, Berking M, et al. Reliability and validity of assessing user satisfaction with web-based health interventions. J Med Internet Res (2016) 18:e234. 10.2196/JMIR.5952 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

80. Ebert DD, Berking M, Thiart H, Riper H, Laferton JA, Cuijpers P, et al. Restoring depleted resources: Efficacy and mechanisms of change of an Internet-based unguided recovery training for better sleep and psychological detachment from work. Heal Psychol (2015) 34:1240–51. 10.1037/hea0000277 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Ebert DD, Berking M, Thiart H, Riper H, Laferton JA, Cuijpers P, et al. Restoring depleted resources: Efficacy and mechanisms of change of an Internet-based unguided recovery training for better sleep and psychological detachment from work. Heal Psychol (2015) 34:1240–51. 10.1037/hea0000277 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

81. Ebert DD, Heber E, Berking M, Riper H, Cuijpers P, Funk B, et al. Self-guided internet-based and mobile-based stress management for employees: Results of a randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med (2016) 73:315–23. 10.1136/oemed-2015-103269 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

82. Bech P, Gudex C, Staehr Johansen K. The WHO (ten) well-being index: validation in diabetes. Psychother Psychosom (1996) 65:183–90. 10.1159/000289073 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

83. Bech P, Olsen LR, Kjoller M, Rasmussen NK. Measuring well-being rather than the absence of distress symptoms: a comparison of the SF-36 mental health subscale and the WHO-five well-being scale. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res (2003) 12:85–91. 10.1002/mpr.145 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Int J Methods Psychiatr Res (2003) 12:85–91. 10.1002/mpr.145 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

84. Brähler E, Mühlan H, Albani C, Schmidt S. Teststatistische Prüfung und Normierung der Deutschen Versionen des EUROHIS-QOL Lebensqualität-Index und des WHO-5 Wohlbefindens-Index. Diagnostica (2007) 53:83–96. 10.1026/0012-1924.53.2.83 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

85. Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; (1965). [Google Scholar]

86. Von Collani G, Herzberg PY. Eine revidierte Fassung der deutschsprachigen Skala zum Selbstwertgefühl von Rosenberg. Z Differ Diagn Psychol (2003) 24:3–7. 10.1024//0170-1789.24.1.3 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

87. Schwarzer R, Sniehotta FF, Lippke S, Luszczynska A, Scholz U, Schüz B, et al. On the Assessment and Analysis of Variables in the Health Action Process Approach: Conducting an Investigation. Berlin: Freie Univ Berlin; (2003). p. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

88. Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. A Retrospective Self-Report: Manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace & Company; (1998). [Google Scholar]

Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. A Retrospective Self-Report: Manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace & Company; (1998). [Google Scholar]

89. Klinitzke G, Romppel M, Häuser W, Brähler E, Glaesmer H. The German version of the childhood trauma questionnaire (CTQ): psychometric characteristics in a representative sample of the general population. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol (2012) 62:47–51. 10.1055/s-0031-1295495 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

90. Bodenmann G. Dyadisches Coping Inventar: Testmanual. Bern, Switzerland: Huber; (2008). [Google Scholar]

91. Ledermann T, Bodenmann G, Gagliardi S, Charvoz L, Verardi S, Rossier J, et al. Psychometrics of the dyadic coping inventory in three language groups. Swiss J Psychol (2010) 69:201–12. 10.1024/1421-0185/a000024 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

92. Kliem S, Job A-K, Kröger C, Bodenmann G, Stöbel-Richter Y, Hahlweg K, et al. Entwicklung und Normierung einer Kurzform des Partnerschaftsfragebogens (PFB-K) an einer repräsentativen deutschen Stichprobe. Z Klin Psychol Psychother (2012) 41:81–9. 10.1026/1616-3443/a000135 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Z Klin Psychol Psychother (2012) 41:81–9. 10.1026/1616-3443/a000135 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

93. Laux L, Glanzmann P, Schaffner P, Spielberger C. Das State-Trait-Angstinventar. Theoretische Grundlagen und Handanweisung. Weinheim: Beltz Test GmbH; (1981). [Google Scholar]

94. Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene R, Vagg P, Jacobs G. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; (1983). [Google Scholar]

95. Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care (2008) 46:266–74. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

96. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Intern Med (2006) 166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

97. Ladwig I, Rief W, Nestoriuc Y. Welche Risiken und Nebenwirkungen hat Psychotherapie? Entwicklung des Inventars zur Erfassung Negativer Effekte von Psychotherapie (INEP). Verhaltenstherapie (2014) 24:252–63. 10.1159/000367928 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Welche Risiken und Nebenwirkungen hat Psychotherapie? Entwicklung des Inventars zur Erfassung Negativer Effekte von Psychotherapie (INEP). Verhaltenstherapie (2014) 24:252–63. 10.1159/000367928 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

98. Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology (1997) 49:822–30. 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00238-0 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

99. Wiltink J, Hauck E, Phädayanon M, Weidner W, Beutel M. Validation of the German version of the international index of erectile function (IIEF) in patients with erectile dysfunction, Peyronie’s disease and controls. Int J Impot Res (2003) 15:192–7. 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900997 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

100. Mayring P. Qualitative inhaltsanalyse. In: Mey G, Mruck K, editors. Handbuch Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; (2010). p. 601–13. [Google Scholar]

p. 601–13. [Google Scholar]

101. Kuckartz U, Ebert T, Rädiker S, Stefer C. Evaluation Online. Internetgestützte Befragung in der Praxis. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; (2009). [Google Scholar]

102. Altman DG. Better reporting of randomised controlled trials: the CONSORT statement. BMJ (1996) 313:570–1. 10.1136/bmj.313.7057.570 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

103. Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods (2002) 7:147–77. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

104. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale: Erlbaum Associates; (1988). [Google Scholar]

105. ter Kuile MM, Melles R, de Groot HE, Tuijnman-Raasveld CC, van Lankveld JJ. Therapist-aided exposure for women with lifelong vaginismus: a randomized waiting-list control trial of efficacy. J Consult Clin Psychol (2013) 81:1127–36. 10.1037/a0034292 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

106. Zarski A-C, Lehr D, Berking M, Riper H, Cuijpers P, Ebert DD. Adherence to internet-based mobile-supported stress management: a pooled analysis of individual participant data from three randomized controlled trials. J Med Internet Res (2016) 18:e146. 10.2196/jmir.4493 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Zarski A-C, Lehr D, Berking M, Riper H, Cuijpers P, Ebert DD. Adherence to internet-based mobile-supported stress management: a pooled analysis of individual participant data from three randomized controlled trials. J Med Internet Res (2016) 18:e146. 10.2196/jmir.4493 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

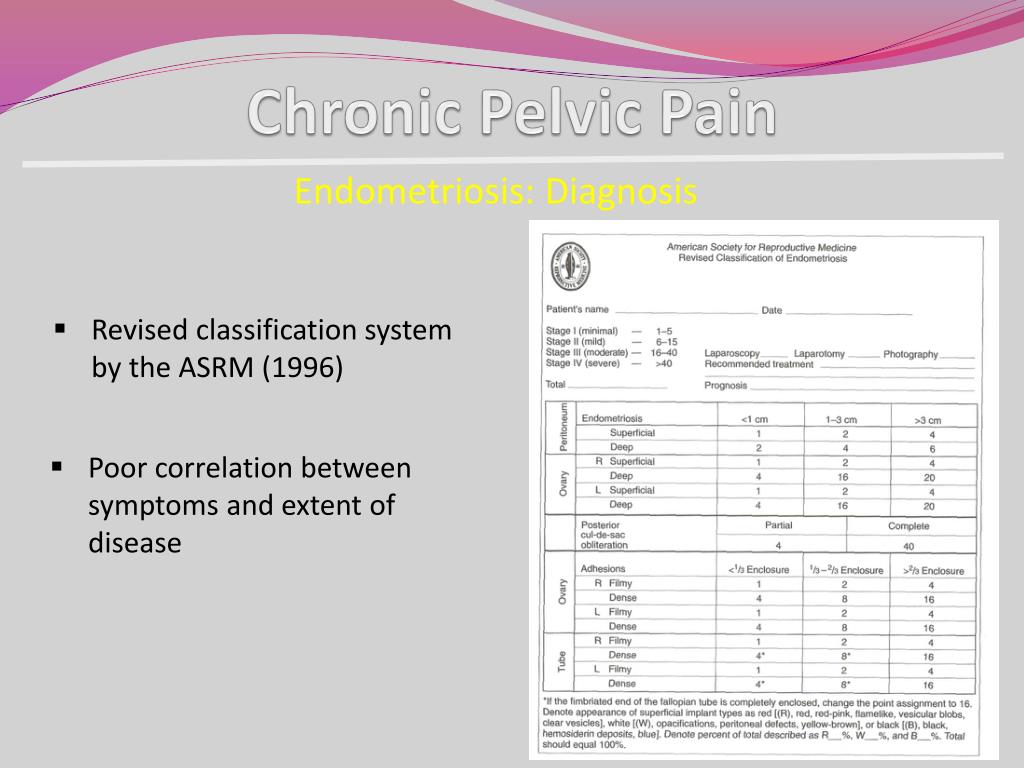

Chronic pelvic pain syndrome in obstetrics and gynecology

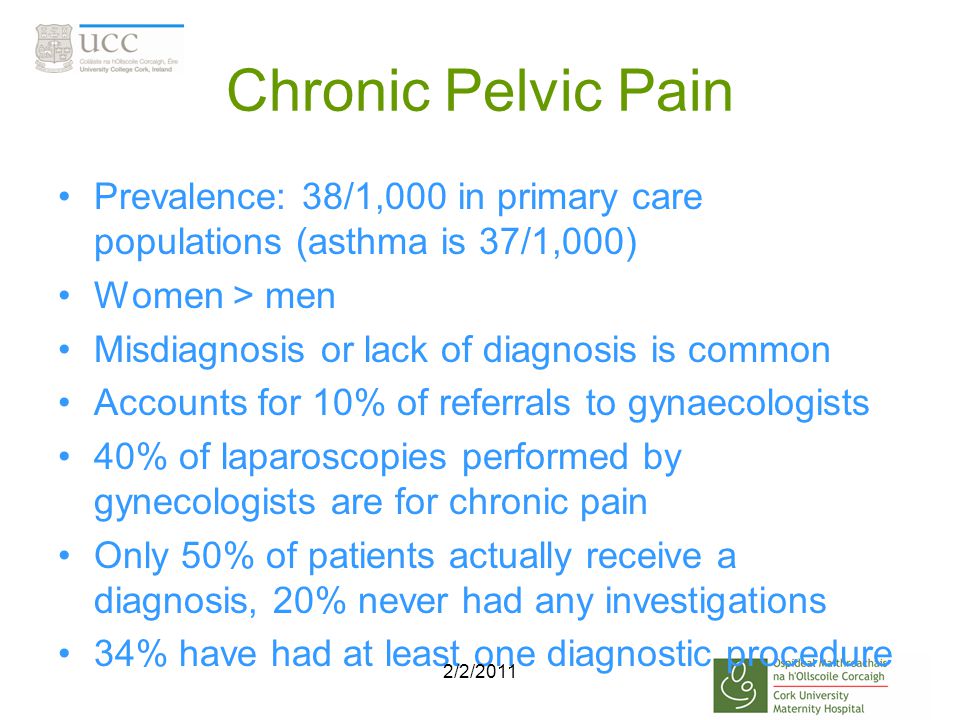

Chronic inflammatory diseases of the internal genital organs are one of the leading causes of reproductive health disorders in women, causing, in particular, the development of infertility, miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, chronic pelvic pain syndrome. The causes of chronic inflammation can be irrational antibiotic therapy, endogenous intoxication of the body, herpes virus infection, secondary immunodeficiency, disturbances in the hemostasis and microcirculation system, hypoxia and slowing down of tissue regeneration processes. The most constant and characteristic clinical manifestation of chronic inflammatory diseases of the reproductive system in women is pelvic pain.

During the III All-Ukrainian Scientific and Practical Conference "Pain Syndromes in Medical Practice", held on 18–19October 2012 in Kyiv, special attention was paid to the issues of chronic pelvic pain in obstetrics and gynecology.

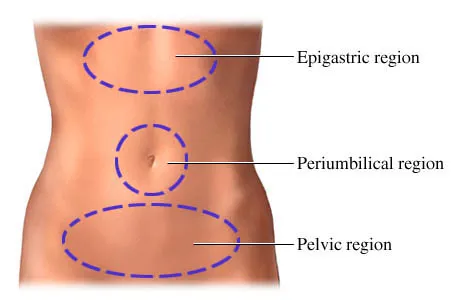

Pelvic pain is defined as a feeling of discomfort in the lower abdomen, while chronic pelvic pain syndrome refers to long-term (>6 months) existing, difficult to stop pelvic pain that disrupts the central mechanisms of regulation of the most important functions of the body, leading to changes in the psyche and human behavior and violating his social adaptation.

According to Irina Romanenko , Candidate of Medical Sciences, Head of the Regional Center for Family Planning and Human Reproduction of the Lugansk Regional Clinical Hospital, in the scientific literature, pelvic pain syndrome is also referred to as pelvic neurosis, vegetative pelvic ganglioneuritis, psychosomatic pelvic congestion. According to the World Health Organization, every 5th person in the world suffers from chronic pain caused by diseases of various organs and systems. Chronic pelvic pain is exceptionally often a symptom of gynecological pathology (> 70% of cases) and rarely has an independent nosological or syndromic significance.

Chronic pelvic pain is exceptionally often a symptom of gynecological pathology (> 70% of cases) and rarely has an independent nosological or syndromic significance.

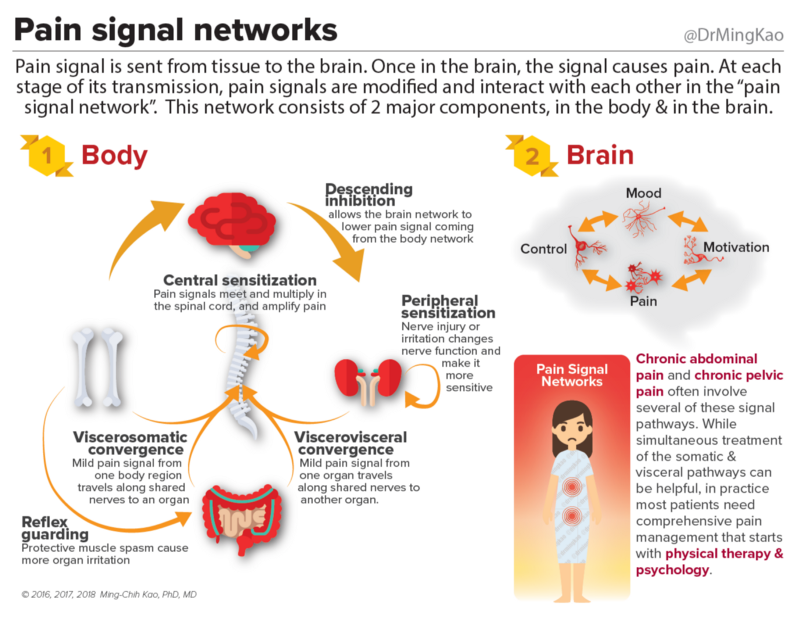

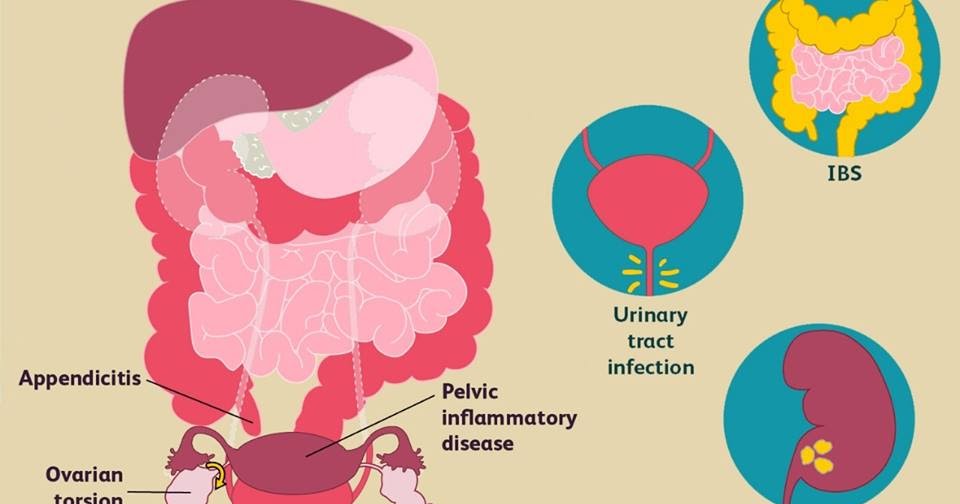

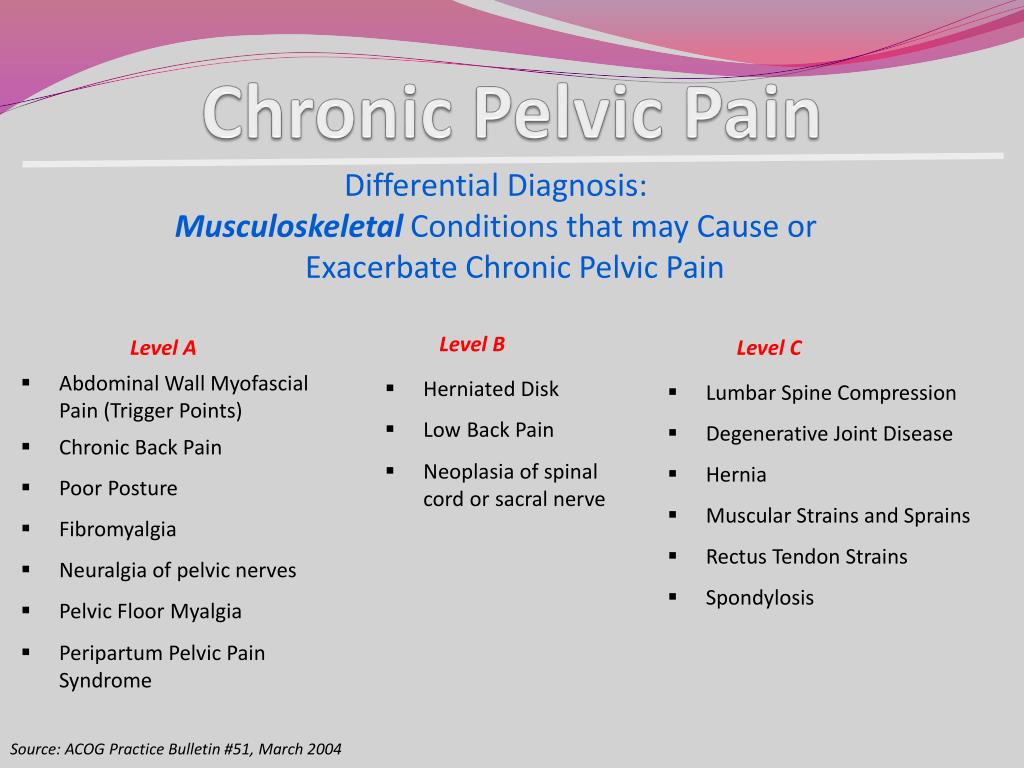

A variety of pathologies can play a role in chronic pelvic pain. On the one hand, it can be a symptom of any gynecological, urological, proctological, neurological, vascular, musculoskeletal or mental disease, on the other hand, it can have a completely independent nosological significance, being the most important component of the pelvic pain syndrome. The main reasons for its development, in particular, in gynecological diseases, include disorders of regional and intraorganic hemodynamics, impaired tissue respiration with excessive formation of cellular metabolic products, inflammatory, dystrophic and functional changes in the peripheral nervous apparatus of the internal genital organs and autonomic sympathetic ganglia.

With chronic pelvic pain syndrome of almost any genesis, women, as a rule, complain of increased irritability, sleep disturbances, decreased performance, loss of interest in the world around them (going into pain), depressed mood, up to the development of depressive and hypochondriacal reactions, which , in turn, aggravate the pathological pain reaction. There is a formation of a kind of vicious circle: pain - social maladaptation - psycho-emotional disorders - pain. Chronicization of pain, as a rule, occurs in people of a certain type: hypochondriacal, anxious, suspicious.

There is a formation of a kind of vicious circle: pain - social maladaptation - psycho-emotional disorders - pain. Chronicization of pain, as a rule, occurs in people of a certain type: hypochondriacal, anxious, suspicious.

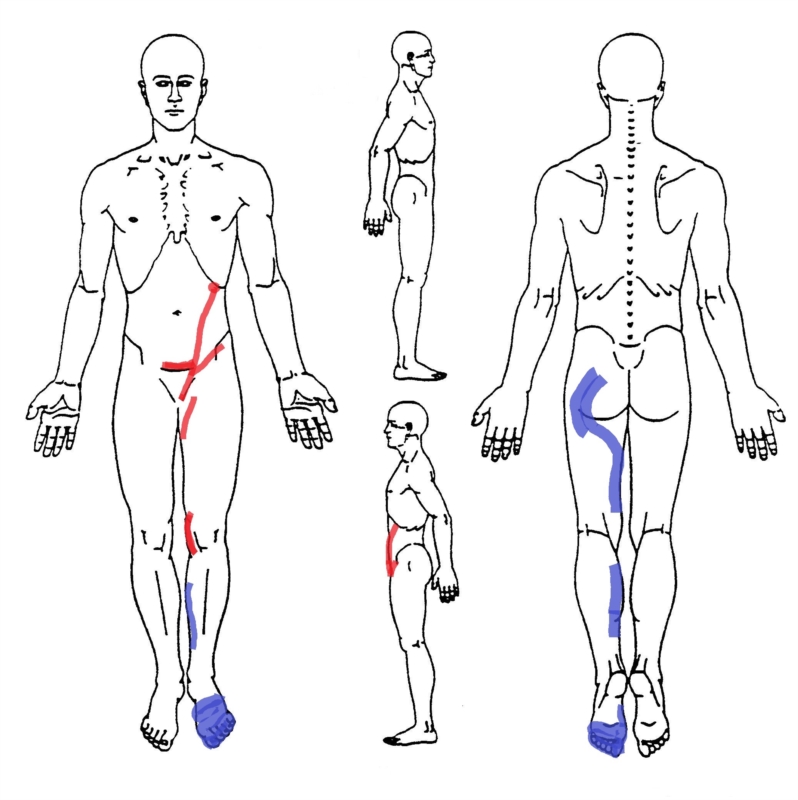

I. Romanenko emphasized that the pain syndrome does not form immediately, but some time after the onset of the action of certain damaging factors, and goes through certain stages of development. The 1st (organ) stage is characterized by the appearance of local pain in the lower abdomen, often combined with dysfunction of the genital and neighboring organs. The 2nd (supraorgan) stage is characterized by repercussion pain in the upper abdomen. At the 3rd (polysystemic) stage of the disease, trophic disorders spread with wide involvement of various parts of the nervous system in the pathological process. At this stage, the disease acquires a polysystemic character, its nosological specificity finally disappears.

A well-collected anamnesis is of key importance for clarifying or verifying the genesis of chronic pelvic pain: the history of the present disease, family and social anamnesis, detailed data on the state of the main systems of the woman's body. With special care, one should record the main complaints, which, it should be noted, are quite diverse.

With special care, one should record the main complaints, which, it should be noted, are quite diverse.

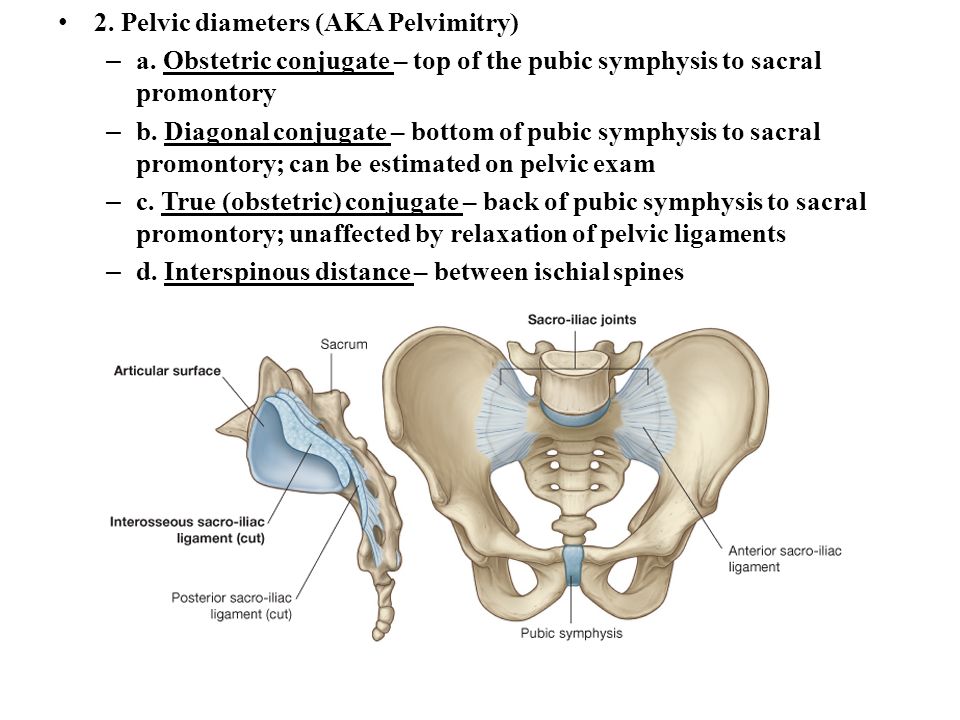

Accurate topography of pain is of great importance:

- pain localized in the midline of the abdomen slightly above the pubic symphysis is characteristic of chronic inflammatory diseases and tumors of the uterus, bladder, rectum, internal endometriosis stage II–III;

- pain in the right/left iliac regions is often a symptom of chronic inflammation of the uterine appendages, external genital endometriosis, traumatic injury to the broad ligaments of the uterus (Allen-Masters syndrome), benign and malignant tumors of the internal genital organs;

- pain projected onto the lower quadrants of the abdomen on the right or left is observed with functional or organic diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, urinary system organs, with damage to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes;

- pain with an epicenter in the lumbosacral region is most often associated with acquired skeletal diseases of traumatic, inflammatory, degenerative or tumor origin;

- Pain in the coccyx is more often the result of its traumatic injury.

When conducting a differential diagnostic search, it is necessary to take into account the factors provoking the aggravation of pain symptoms. So, the appearance or intensification of pain in the 2nd phase of the menstrual cycle, usually 3-7 days before the expected menstruation, may be a manifestation of premenstrual syndrome, genital endometriosis, varicose veins of the small pelvis. The appearance or worsening of pelvic pain during menstruation is associated with adenomyosis, primary dysmenorrhea, abnormalities in the position and development of the uterus, and chronic endometritis. An increase in pain symptoms in the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle is most characteristic of an exacerbation of chronic inflammation of the uterine appendages.

After a thorough assessment of the effectiveness of the previous treatment, the patient's vegetative and psychological status, the threshold of pain sensitivity, testing on visual analog scales that allow studying the dynamics of the pain symptom over a time interval, and, if necessary, consultations of related specialists, clinical and laboratory and instrumental examination:

- laboratory test for herpetic infection;

- ultrasound examination of the pelvic organs;

- x-ray examination of the lumbosacral spine and pelvic bones;

- absorption densitometry to rule out osteoporosis;

- x-ray (irrigoscopy) or endoscopic (sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, cystoscopy) examination of the gastrointestinal tract and bladder;

- laparoscopy (allows you to identify all the main causes of pain in the pelvis).

If the cause of pain cannot be identified (≈1.5% of cases), according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, "pain without an apparent cause" is diagnosed, which gives rise to symptomatic treatment.

Based on a holistic understanding of the multifactorial nature of chronic pelvic pain, the treatment of this category of patients requires an integrated approach. Usually, the duration of the pain history is proportional to the number of methods and methods of treatment tried, the patient's nihilism in relation to medicine in general and specific doctors in particular. It is necessary to involve specialists of various profiles in drawing up a treatment plan for the patient: a therapist, urologist, neurologist, physiotherapist and, possibly, a psychoneurologist. Collegiality reduces the likelihood of confrontation between the patient and the doctor, increasing the chances of success.

Treatment for chronic pelvic pain should be based on the following basic principles:

- elimination of the source of pain impulses;

- blockade of the propagation of a nociceptive impulse along nerve fibers;

- change in perception of nociceptive stimulus;

- increased activity of the endogenous antinociceptive system.

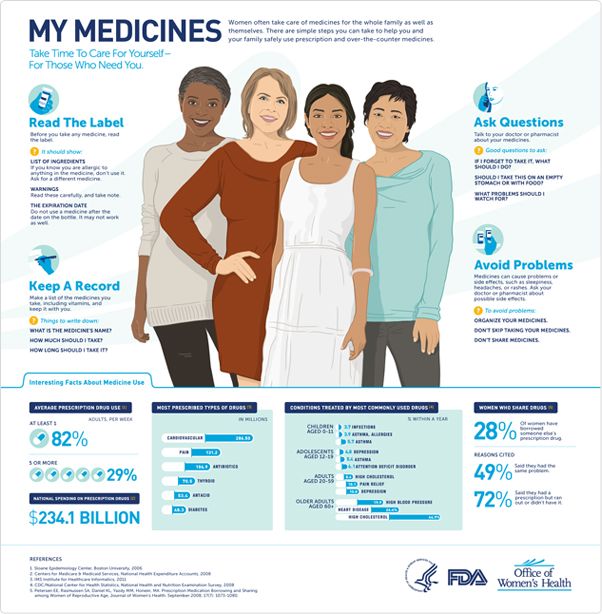

The main requirements for analgesics are:

- versatility, that is, effectiveness in the treatment of patients with acute and chronic pain caused by factors of various etiologies;

- safety of use in different categories of patients, including elderly patients, persons with functional disorders of the liver and kidneys;

- slow development of tolerance with long-term use;

- low drug potential;

- minor interaction with other drugs;

- availability of different dosage forms and routes of administration;

- For dysmenorrhea and postoperative pain, it is important that the use of analgesics does not affect the length of bleeding time.

Supplemented the topic of treatment for chronic pelvic pain Yuri Oleinik , Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 1 of the National Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education. P.L. Shupik, noting that the current issue today is the development of new therapy strategies with the use of drugs with a complex effect.

1 of the National Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education. P.L. Shupik, noting that the current issue today is the development of new therapy strategies with the use of drugs with a complex effect.

According to Yu. Oleinik, drugs used in the treatment of patients with chronic pelvic pain should have a pronounced anti-inflammatory and resolving effect, reduce the intensity of destructive and infiltrative processes in the focus of inflammation, increase the resistance of the mucous membrane to the action of damaging factors, and have a mild immunomodulatory effect , accelerate the processes of epithelialization and regeneration at the level of cellular and molecular initiation, without having a general toxic, allergenic and damaging effect.

Violation of the cytokine regulation of the immune system in women with chronic inflammatory diseases of the internal genital organs is manifested by secondary immune deficiency, the development of which can be prevented in a timely manner by the use of pathogenetically justified therapy. Timely treatment for chronic inflammatory diseases of the internal genital organs of women of reproductive age contributes to a more rapid restoration of the function of the immune system, including at the local level, normalization of the cytokine profile, prevention of early and late relapses, restoration and preservation of reproductive function.

Timely treatment for chronic inflammatory diseases of the internal genital organs of women of reproductive age contributes to a more rapid restoration of the function of the immune system, including at the local level, normalization of the cytokine profile, prevention of early and late relapses, restoration and preservation of reproductive function.

Antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal therapy is prescribed for chronic inflammatory diseases of the genital organs; with tumors of the genital organs, adhesions, external and internal endometriosis, developmental anomalies and incorrect positions of the genital organs, surgical treatment may be indicated; with varicose veins of the small pelvis - endovascular and endosurgical methods of treatment. In order to normalize local biochemical processes in the tissues surrounding the pain receptor, hormone therapy, antioxidant therapy, vitamin therapy, enzyme therapy, and physiotherapy are indicated. To normalize activating and inhibitory processes in the central nervous system, influence the antinociception system, and prevent the development of neurotic reactions, psychotherapy, suggestive therapy, the use of sedatives, drugs with a vegetative-corrective effect, acupuncture, etc. are indicated.

are indicated.

It is necessary to help the patient understand the cause of pain and, if possible, to specify the factors that lead to exacerbation. It is advisable to minimize the number of pharmacological agents used, eliminating unnecessary and ineffective ones. The treatment regimen should be simplified as much as possible, gradually reducing the doses of drugs to the level of achieving a pronounced beneficial effect with minimal side effects.

It is recommended to introduce methods of restorative therapy as early and widely as possible, aimed at correcting personal factors that impede the elimination of pain, increasing the functionality of the body and improving the quality of life.

Tatyana Kharchenko,

photo of the author

Article "Chronic pelvic pain in women"

The problem of chronic pelvic pain in women of reproductive age occupies a special place in gynecology. Almost half of the patients who turn to the specialists of the EMC Department of Gynecology and Oncogynecology have complaints of chronic pelvic pain - discomfort for a long time in the lower abdomen, in the area below the navel. Long-term, despite the fact that conventional painkillers are ineffective, pelvic pain changes the psyche, the behavior of women, reduces the ability to work and quality of life.

Long-term, despite the fact that conventional painkillers are ineffective, pelvic pain changes the psyche, the behavior of women, reduces the ability to work and quality of life.

Pain may be constant or intermittent, even paroxysmal, may be cyclical or not at all related to the menstrual cycle. Pain impulses arising in the genitals and surrounding tissues as a result of irritation of nerve endings are transmitted to the central nervous system, which in most women is accompanied by general weakness, irritability, anxiety, excitability, emotional lability, attention disorders, memory loss, sleep disturbances.

Chronic pelvic pain is characterized by:

-

persistent pain in the lower abdomen and lower back of varying intensity and character (pulling, dull, burning, etc.), prone to irradiation, lasting more than 6 months;

-

periodic exacerbations - painful crises arising from cooling, overwork, stress, etc.;

-

psycho-emotional disorders, manifested by insomnia, irritability, disability, anxiety and depression, decreased sexual function up to a complete lack of interest and sexual response;

-

no or little effect of conventional pain and antispasmodic therapy.

In some cases, it is not possible to identify its causes even with an in-depth examination - this is the so-called "inexplicable" pain. For such patients, the “triangle” route - gynecologist-urologist-neurologist - becomes familiar, and pain and fear force them to turn to an oncologist. Often, for years, these patients have been treated for "inflammation of the uterus and appendages" with large doses of antibacterial drugs, and such irrational treatment aggravates the situation even more.

Pain is one of the most common symptoms in many gynecological diseases. External genital endometriosis, adhesions in the pelvic cavity, chronic inflammatory diseases of the internal genital organs, internal endometriosis of the uterine body, Allen-Masters syndrome, genital tuberculosis, uterine fibroids, benign and malignant ovarian tumors, malignant neoplasms of the body and cervix, developmental anomalies genital organs with a violation of the outflow of menstrual blood - this is not a complete list of diseases and conditions that may be accompanied by chronic pelvic pain.

The most common misconceptions about chronic pelvic pain

Only gynecological diseases can be the causes of chronic pelvic pain in women

coccygeal articulation, primary tumors of the pelvic bones, metastases to the pelvic bones and spine, bone forms of tuberculosis, pathology of the symphysis), retroperitoneal neoplasms, diseases of the peripheral nervous system (plexitis), diseases of the gastrointestinal tract (chronic colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, nonspecific ulcerative colitis, proctitis, adhesive disease), diseases of the urinary system (chronic cystitis, urolithiasis, pelvic location of the kidney, prolapse of the kidney), vascular disease (varicose veins of the small pelvis). The causes of chronic pain syndrome can also be mental illness (abdominal epileptic seizures, depressive syndrome, schizophrenia).

Pain is usually caused by one factor, eliminating which, you can get rid of pain

In fact, in most gynecological diseases, the origin of pain is caused by several irritants at once, and it is often impossible to single out the leading factor. With uterine fibroids, pain can be caused by an increase in this organ, a violation of its blood supply and contractility of the uterine muscle, deformation of the uterine cavity by nodes, compression of the enlarged uterus or individual nodes of neighboring organs - the intestines, urinary tract, nerve plexuses, blood vessels.

With uterine fibroids, pain can be caused by an increase in this organ, a violation of its blood supply and contractility of the uterine muscle, deformation of the uterine cavity by nodes, compression of the enlarged uterus or individual nodes of neighboring organs - the intestines, urinary tract, nerve plexuses, blood vessels.

Tumors and cysts of the ovaries are subject to stretching of the tissues and ligaments of the ovaries (up to torsion), maturation of the follicles is disturbed, micro-ruptures with inflammation and the formation of adhesions are possible, compression of adjacent organs by cysts

a functioning uterus with aplasia of the cervix or vagina, a rudimentary uterine horn, a closed cavity of a bicornuate or doubled uterus) and other conditions accompanied by a violation of the outflow of menstrual blood (intrauterine synechia, stenosis of the cervical canal or cicatricial changes in the vagina). In these cases, the onset of pain is due to the expansion of closed cavities with blood and irritation of the peritoneum with almost constant hemoperitoneum, inflammation, and adhesions. Incorrect positions of the internal genital organs (bends of the uterus, prolapse, prolapse) also cause pelvic pain.

Incorrect positions of the internal genital organs (bends of the uterus, prolapse, prolapse) also cause pelvic pain.

As a rule, most patients have a combined gynecological pathology, and each of the diseases can cause pain. External endometriosis often accompanies any other gynecological disease, and uterine fibroids are combined with internal endometriosis of the uterine body. Often there is a prolapse of the uterus, affected by fibroids or adenomyosis. The presence of a combined gynecological and extragenital pathology (hernias, diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, osteochondrosis of the spine) can significantly complicate the determination of the true cause of pain.

Periodic pain in women is normal

This myth has been around since the 19th century. Doctors then explained menstrual pain by the instability and delicacy of the physiology of women and believed that pain during menstruation is the norm, which is very characteristic of the female body. Another "cause" of pain in women during menstruation is, according to some, a low pain threshold.

Another "cause" of pain in women during menstruation is, according to some, a low pain threshold.

In fact, many women and girls experience pain during their periods. However, severe pain that disrupts the habitual lifestyle and level of activity cannot be the norm, and usually they are based on some kind of disease, for example, endometriosis, a hormone-dependent disease in which the lining of the uterus (endometrium) grows in other parts of the body. This is the third most common gynecological disease after uterine fibroids and various inflammatory processes in the genitals.

Therefore, every woman with severe pain during menstruation should be fully examined to identify their cause.

Early identification of the causes of pain determines the success of treatment. To establish the possible causes of pelvic pain, we work as a team with doctors of other specialties - general surgeons, oncologists, urologists, neurologists, psychologists.

For the treatment of chronic pelvic pain, EMC gynecologists-surgeons use an approach based on reducing the invasiveness of surgery, avoiding excessive radicalism, and expectant management in certain diseases of the genital area.

Laparoscopy and hysteroscopy provide us with unique diagnostic and therapeutic opportunities, which allow us to identify and eliminate possible causes of pain that are not diagnosed by other examination methods: endometriosis of the pelvic peritoneum, adhesions, anatomical disorders - hernia, peritoneal defects (Allen-Masters syndrome).

From the patient’s point of view, laparoscopic intervention, unlike laparotomy, is not perceived as a “big and difficult” operation, and the absence of intense and prolonged postoperative pain associated with the surgical wound of the anterior abdominal wall eliminates the aggravation of the initial pain due to layering on them operating rooms. And, finally, early activation and return to physical activity, the almost absence of cosmetic defects also contribute to a quick recovery.

The volume of surgical intervention is chosen by EMC gynecologists depending on the age of the patient, her plans for childbearing, the severity of the detected pathology, the severity of pain. In young women, organ-preserving surgeries are performed, warning patients about the likelihood of recurrence of diseases such as endometriosis and uterine fibroids. Patients of older age groups with adenomyosis, multiple uterine fibroids, accompanied by severe pain, bleeding and leading to anemia, tumor growth and its significant size, dysfunction of neighboring organs, are shown radical operations in the volume of removal of the uterus, which we perform by laparoscopy or from a vaginal access .

In young women, organ-preserving surgeries are performed, warning patients about the likelihood of recurrence of diseases such as endometriosis and uterine fibroids. Patients of older age groups with adenomyosis, multiple uterine fibroids, accompanied by severe pain, bleeding and leading to anemia, tumor growth and its significant size, dysfunction of neighboring organs, are shown radical operations in the volume of removal of the uterus, which we perform by laparoscopy or from a vaginal access .

In case of prolapse and prolapse of the pelvic organs, accompanied by pelvic pain, EMC gynecologists use surgical correction technologies that are fundamentally different from each other, depending on the age of the patient, to effectively eliminate gynecological pathology and restore the disturbed pelvic anatomy. For pelvic varicose veins, we perform laparoscopic ovarian vein ligation, which is highly effective for pelvic pain due to congestion in the pelvic veins, without adversely affecting ovarian function.