Feeling pain of others

Can You Actually Feel Someone Else’s Pain?

Sympathy pain is a term that refers to feeling physical or psychological symptoms from witnessing someone else’s discomfort.

Such feelings are most often talked about during pregnancy, where a person might feel like they’re sharing the same pains as their pregnant partner. The medical term for this phenomenon is known as couvade syndrome.

While not an official health condition, couvade syndrome is, in fact, extremely common.

Recent research published in the American Journal of Men’s Health found that between 25 and 72 percent of expectant fathers worldwide experience couvade syndrome.

Sympathy pains have been widely researched and supported in relation to pregnancy. There are also anecdotal cases where individuals believe they experience pain in other situations.

This pain doesn’t pose any danger, but it’s worth considering the science to help explain this phenomenon. A mental health professional can also help you work through the feelings that may be causing your sympathy pains.

Sympathy pains are most commonly associated with couvade syndrome, which occurs when a person experiences many of the same symptoms as their pregnant partner. Such discomfort is most common during the first and third trimesters. It’s thought that feelings of stress, as well as empathy, may play a role.

However, sympathy pains aren’t always exclusive to pregnancy. This phenomenon could also occur in individuals who have deep connections with friends and family members who might be going through an unpleasant experience.

Sometimes, sympathy pains can also occur among strangers. If you see someone who is in physical pain or mental anguish, it’s possible to empathize and feel similar sensations. Other examples include feeling discomfort after seeing images or videos of others in pain.

While not a recognized health condition, there’s a great deal of scientific research to support the existence of couvade syndrome. This is especially the case with individuals whose partners are pregnant. Other instances of sympathy pain are more anecdotal.

Other instances of sympathy pain are more anecdotal.

Some studies are also investigating more medical instances of sympathy pain. One such study published in 1996 examined patients with carpal tunnel and found that some experienced similar symptoms in the opposite, unaffected hand.

The precise cause of sympathy pains is unknown. While not regarded as a mental health condition, it’s thought that couvade syndrome and other types of sympathy pains may be psychological.

Some studies indicate that couvade syndrome and other causes of sympathy pains may be more prominent in individuals who have a history of mood disorders.

Sympathy pains and pregnancy

Pregnancy can cause a variety of emotions for any couple, which is often a combination of excitement and stress. Some of these emotions may play a role in the development of your partner’s sympathy pains.

In the past, there were other psychology-based theories surrounding couvade syndrome. One was based on males experiencing jealousy over their pregnant female partners. Another unfounded theory was the fear of a possibly marginalized role through parenthood.

Another unfounded theory was the fear of a possibly marginalized role through parenthood.

Some researchers believe sociodemographic factors could play a role in the development of couvade syndrome. However, more studies need to be conducted on this front to determine whether these types of risk factors can predict whether someone might experience sympathy pains during pregnancy.

Couvade syndrome and pseudocyesis

Another pregnancy-related theory is that couvade syndrome may occur alongside pseudocyesis, or phantom pregnancy. Recognized by the new edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, phantom pregnancy is defined as experiencing pregnancy symptoms without actually being pregnant.

The experience of a phantom pregnancy is so strong that others may believe the person is pregnant and then experience couvade syndrome.

Empathetic personality

It’s thought that empathy could play a role with couvade syndrome and other instances of sympathy pain. An individual who is naturally more empathetic might be more likely to have sympathy pains in response to someone else’s discomfort.

An individual who is naturally more empathetic might be more likely to have sympathy pains in response to someone else’s discomfort.

For example, seeing someone get hurt could cause physical sensations as you empathize with their pain. You might also feel changes in your mood based on how others are feeling.

If you’re pregnant, and you suspect your partner might be experiencing couvade syndrome, they might exhibit the following symptoms:

- abdominal pain and discomfort

- aches in the back, teeth, and legs

- anxiety

- appetite changes

- bloating

- depression

- excitement

- food cravings

- heartburn

- insomnia

- leg cramps

- libido issues

- nausea

- restlessness

- urinary or genital irritation

- weight gain

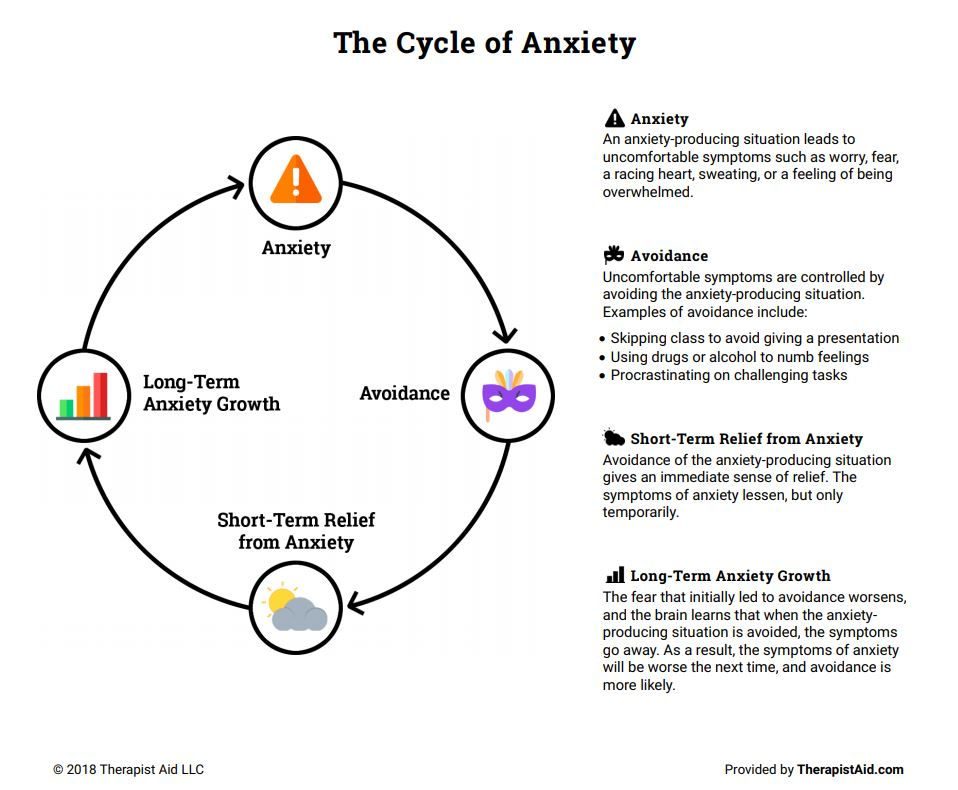

There’s no treatment available for couvade syndrome. Instead, it’s important to focus on anxiety and stress management techniques. These may include relaxation, a healthy diet, and regular exercise.

If anxiety or depression from couvade syndrome interferes with your loved one’s daily routine, encourage them to seek help from a mental health professional. Talk therapy may help your partner work through the stresses of pregnancy.

While sympathy pains are still being researched, it’s thought that the symptoms resolve once your partner’s pain and discomfort start to dissipate. For example, symptoms of couvade syndrome may resolve on their own once the baby is born.

Other types of sympathy pain may also stem from empathy and are regarded as a psychological phenomenon. If you have long-lasting sympathy pain or are experiencing long-term changes in mood, see your doctor for advice.

Study: People Literally Feel Pain of Others

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

Maybe Tonight Honey, I Have a MigraineA brain anomaly can make the saying "I know how you feel" literally true in hyper-empathetic people who actually sense that they are being touched when they witness others being touched.

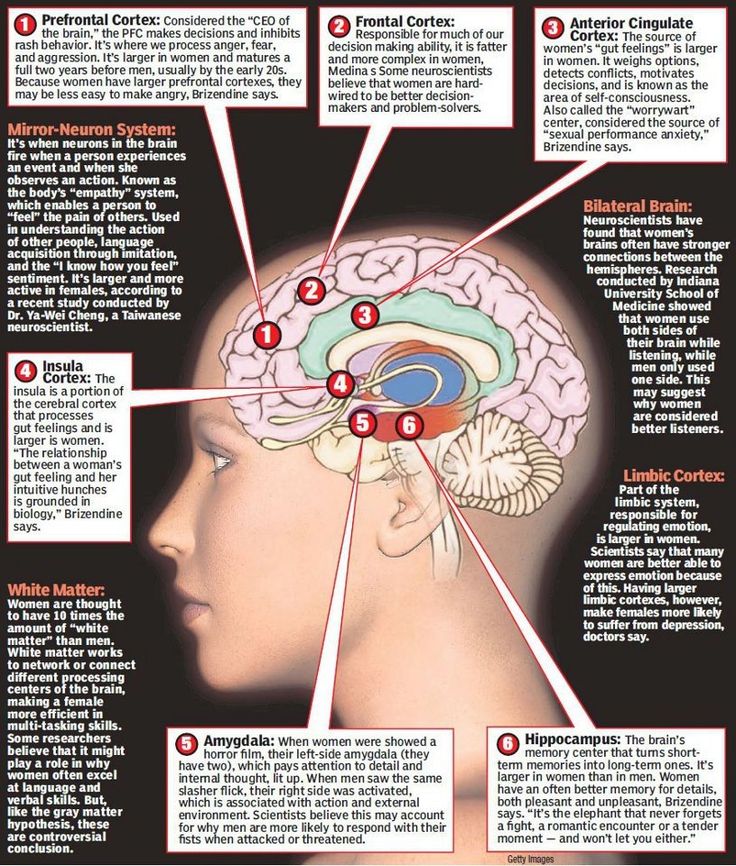

The condition, known as mirror-touch synesthesia, is related to the activity of mirror neurons, cells recently discovered to fire not only when some animals perform some behavior, such as climbing a tree, but also when they watch another animal do the behavior. For "synesthetes," it's as if their mirror neurons are on overdrive.

"We often flinch when we see someone knock their arm, and this may be a weaker version of what these synesthetes experience," University College London cognitive neuroscientist Jamie Ward said.

Now scientists find these synesthetes possess an unusually strong ability to empathize with others. Further research into this condition might shed light on the roots of empathy, which could help better understand autism, schizophrenia, psychopathy and other disorders linked with empathy.

Blended experiences

Synesthesia is a condition where sensations that normally are experienced separately get blended together. The most common form is color-grapheme synesthesia, where a person experiences colors upon hearing or reading words. Others can taste words.

Others can taste words.

In mirror-touch synesthesia, when another person gets touched, the synaesthete feels a touch on their body. University College London cognitive neuroscientist Sarah-Jayne Blakemore discovered a mirror-touch synesthete in 2003 by a stroke of good luck.

"I was giving a talk and mentioned synesthesia, and that anecdotally there were reports that some people felt touches they only observed, and there was a woman in the audience who asked, 'Doesn't everyone experience that? Isn't that completely normal?'" Blakemore recalled.

Until that point, that 39-year-old woman did not realize her mirror-touch synesthesia was unusual. "It was something she's always had," Blakemore told LiveScience. In fact, a cousin of hers also has it, suggesting it runs in families.

When the woman faced someone and saw that person get touched on the left cheek, she felt it on her right cheek. On the other hand, if she stood next to somebody and that person got touched on the right side, she felt a touch on her right side.

The pain of horror films

Now Ward and doctoral student Michael Banissy reveal 10 more mirror-touch synesthetes they discovered among University College London students, as well as among people who possess other types of synesthesia. (The woman that Blakemore has 11 relatives with color-grapheme synesthesia, and that woman had color-grapheme synesthesia herself when she was younger.)

The researchers had the mirror-touch synesthetes take a questionnaire designed to measure empathy. For instance, they were asked to agree or disagree with statements such as "I can tune into how someone feels rapidly and intuitively."

The mirror-touch synesthetes scored significantly higher than people without synesthesia, findings detailed in the July issue of the journal Nature Neuroscience.

One mirror-touch synaesthete, Alice, said "I have never been able to understand how people can enjoy looking at bloodthirsty films, or laugh at the painful misfortunes of others when I can not only not look but also feel it. " Another, Jane, said she felt her synesthesia is "a positive thing because I believe it makes me more considerate about the feelings of others."

" Another, Jane, said she felt her synesthesia is "a positive thing because I believe it makes me more considerate about the feelings of others."

Overactive mirrors

Banissy told LiveScience that "when we observe another person being touched, we all activate areas of our brain similar to those activated when we are physically touched." In mirror-touch synesthetes, this mirror system is overactive. The resulting high level of empathy they demonstrate supports the notion that people learn to empathize by putting themselves in someone else's shoes.

"It is extraordinary to think that some people experience touch on their own body when they merely watch someone else being stroked or punched. However, this may be an exaggeration of a brain mechanism that we all possess to some degree," Ward said.

UCLA neuroscientist Marco Iacoboni explained a better understanding of the mirror system could help shed light and treat autism, "which is well-known for not understanding the emotional states of others. " Blakemore added such research could also help research into psychopaths, "where empathy goes wrong and people don't feel empathy in the normal way."

" Blakemore added such research could also help research into psychopaths, "where empathy goes wrong and people don't feel empathy in the normal way."

On a fundamental level, University of Parma cognitive neuroscientist Vittorio Gallese suggested this system "might be relevant for the ability to entertain an abstract notion of touch, such as upon watching objects touch each other."

- Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind

- New Insight into People Who Taste Words

- The Most Popular Myths

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Live Science and Space.com. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica.

A person can feel someone else's pain

Society 28172

Share

"I know how you feel" - this phrase is really true. Researchers have come to the conclusion that the human brain is designed in such a way that he can actually feel what another feels.

There are people who know how to put themselves in the place of another. But now it turned out that the pain that they experience, seeing the suffering, is quite real.

The key here is the concept of synesthesia. These are phenomena when separate emotions are mixed.

An example of synesthesia is the following: a person associates the sound of a word with a certain color or feels its “taste”.

As for the feeling of someone else's pain, here we are talking about a rarer phenomenon - mirror synesthesia. This state is associated with the reaction of mirror neurons. They were first discovered in the 1990s, when a group of Italian scientists studied the features of brain activity in monkeys. Zoologists have stumbled upon special cells in the cerebral cortex. Neurons fired not only when the macaque itself performed some action, but also when it watched how the same action is performed by a person. Hence the name, mirror neurons.

New research in this area may finally shed light on the phenomenon of "empathy" in humans.

In the case of mirror synesthesia, a person feels touch when someone else is being touched before their eyes.

This phenomenon was first discovered by Dr. Sarah-Jane Blackmore of University College London in 2003.

“I was giving a lecture and I mentioned synesthesia. I also laughed at the reports that some people supposedly feel touched when no one really touches them, Blackmore recalls. - Then one of the listeners asked: “Is there anyone who does not feel this? Isn't that normal?"

Until that moment, the 39-year-old woman did not realize that she had the phenomenon of mirror synesthesia. When she saw someone being touched on the left cheek, she felt the touch on her own but on the right. If she was standing not in front of a person, but behind him or next to him, a touch on his right side was also given to her on the right.

So far, British scientists have identified several more cases of mirror synesthesia.

“I never understood how it was possible to watch bloody horror films or laugh at the painful sensations of comedy characters, while I not only see what is happening on the screen, but also feel the same as they do,” says student Ellis, who have been diagnosed with this condition.

Another student named Jane says synesthesia is a good thing because it "helps you understand other people better."

This condition is more or less characteristic of all people, the peculiarity and uniqueness of mirror synesthesia lies in the fact that mirror neurons in humans are hyperactive.

“It is unusual to think that some feel touch when they push and hit another. However, this is only a high degree of empathy, inherent in everyone and everyone, ”comments specialist Jamie Ward.

Research on mirror synesthesia will also shed light on the causes of diseases such as schizophrenia and autism.

"Autism is known as a condition where a person is unable to understand the emotions of others - continues Blackmore. “And in the case of psychopathy, empathy takes a distorted form.”

Based on Livescience.com

Subscribe

Authors:

- Natalia Stepanova

What else to read

What to read:More materials

In the regions

-

A film about the life of the Russian Crimea was shown in Paris

Photo 48893

Crimeaphoto: MK in Crimea

-

Plant an onion the Chinese way: it will grow surprisingly large and juicy

20261

Kalmykia -

Don't Eat This: Doctors Say One Part Of Apples Is Deadly

9480

Pskov -

American journalist compared Crimea with Texas

Photo Video 9412

CrimeaDenis Pronichev photo: crimea.

mk.ru

mk.ru -

Scandal in Shchelkovo: officials did not let widows and mothers of dead soldiers to the monument

Photo 8422

Moscow regionElena BEREZINA

-

Who are Ryodan PMCs and what are they doing in Karelia

5247

KareliaVladimir Pospelov

In the regions:More materials

Feel someone else's pain as your own

Know yourself A man among people

Lisa paces the hospital hall and cannot stop. Behind the wall, her daughter is undergoing her third session of chemotherapy. Liza imagines how chilling - and yet necessary for treatment - poison once again spreads through Natasha's veins. She thinks she feels nausea rising up her daughter's throat and painful cramps in her stomach. Lisa tells herself that she would give anything for the opportunity to be there instead of Natasha.

Behind the wall, her daughter is undergoing her third session of chemotherapy. Liza imagines how chilling - and yet necessary for treatment - poison once again spreads through Natasha's veins. She thinks she feels nausea rising up her daughter's throat and painful cramps in her stomach. Lisa tells herself that she would give anything for the opportunity to be there instead of Natasha.

Alexander cannot tear himself away from the TV screen: one hundred thousand refugees do not find salvation from the war. They have been walking in the desert for many days, often without food or water. A father with a sightless look carries a dead child in his arms. The camera stops at his unwound turban, his arms vainly clutching the boy to his chest.

Alexander gets up from his chair. He is a doctor. He can't calm down. He has to do something, he wants to be there with these people. A few days later he is already in Africa, in the group "Doctors Without Borders".

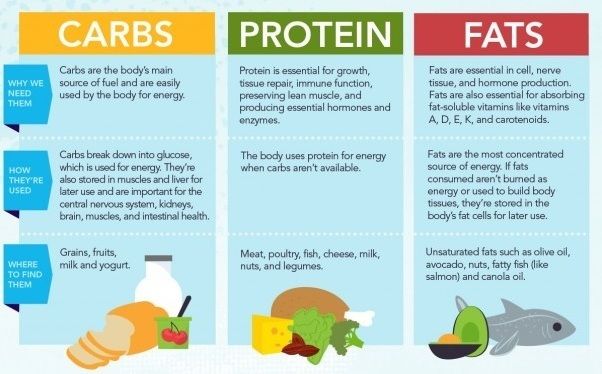

When we suffer, the body is mobilized to endure. This is a well-known reaction: fight or flight! But where does the feeling that we experience the pain of another person come from? Where does this powerful impulse come from - to relieve the suffering of another, as if it is hurting ourselves right now?

This is a well-known reaction: fight or flight! But where does the feeling that we experience the pain of another person come from? Where does this powerful impulse come from - to relieve the suffering of another, as if it is hurting ourselves right now?

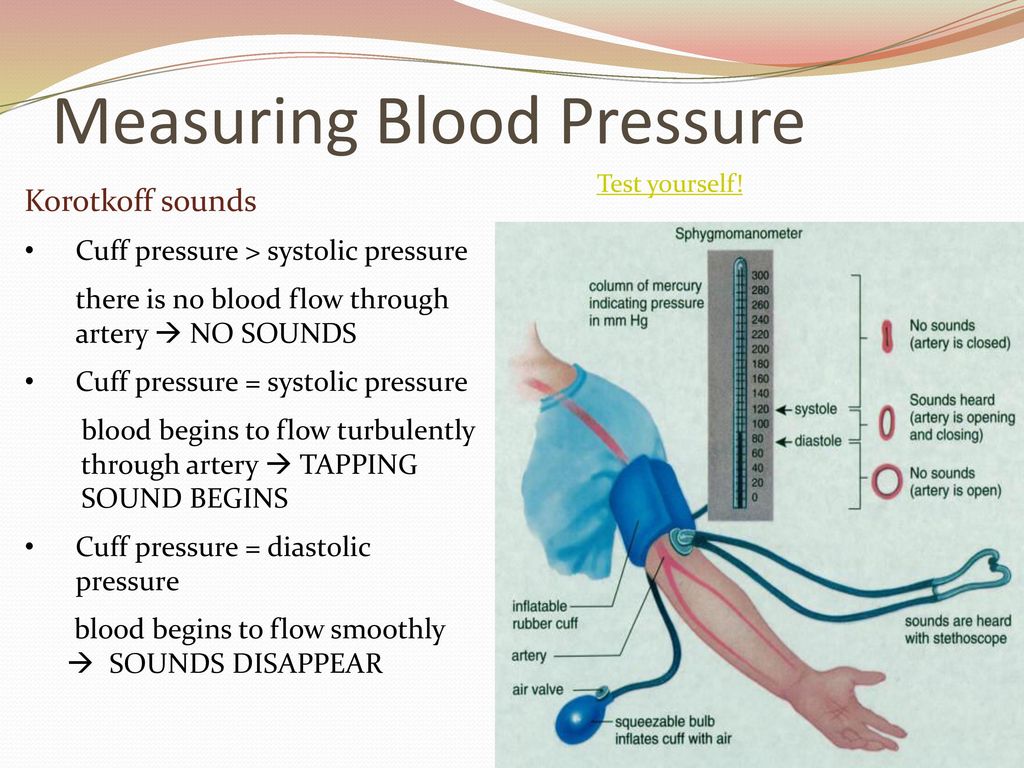

At University College London, several female participants in an experiment were asked to undergo magnetic resonance imaging of the brain while their husbands were exposed to electric current 1 . They were warned a few seconds before the electric shock. In addition, each of them could see in the mirror how her husband's hand was clenched. The faces of all the women reflected the pain that the sight of the suffering of a loved one caused them.

First of all, a group of researchers led by Tanya Singer was interested in what was going on in the brains of these women. Scanning showed that they activated the same zones of emotional reactions as people who are actually affected by electric shock.

The other person's pain has become their own. Their brain "appropriated" this pain. These women, who are connected with their husbands by love, seem to have pierced the membrane that separates the “I” from the “you”.

Their brain "appropriated" this pain. These women, who are connected with their husbands by love, seem to have pierced the membrane that separates the “I” from the “you”.

A connection is recorded in our brain that connects us with the joys and pains of others, with the world around us. In other words, "something of you entered me and lives in me." I am no longer just me, because your feelings have now become mine.According to the American philosopher Susan Langer, under the influence of love the shell of individual being becomes permeable 2 . Of course, not all people are equally capable of feeling this kind of empathy. Women are generally superior to men in this respect. This natural response of the brain underlies our ability to connect with other people, which is the essence of the human in us.

Mammals differ from other animals not only in that they feed on mother's milk, but also in the presence of areas in the brain that provide affective communication between children and parents, especially with the mother.

The anterior part of the cingulate gyrus of the cerebral cortex - this is exactly the zone that became active in women in the experiment described above - developed precisely so that the cries of the baby were completely unbearable for the mother and made it impossible for them to part. This mechanism provides constant contact with the adult, which is necessary for the growth and development of vulnerable young mammals.

In addition to attachment to loved ones, the capacity for compassion—that is, suffering with others—is at the heart of the doctor's vocation, encourages volunteers to help those in need, and explains everyone's desire for a more harmonious society.

Our brain structures have a connection that connects us to the pains and joys of other people, to the world around us. This connection is what makes us human - isolated and connected to each other. Feeling and therefore responsible.

1 T. Singer, B. Seymour. Empathy for Pain Involves the Affective But Not Sensory Components of Pain.