Family of mentally ill

Maintaining a Healthy Relationship | NAMI: National Alliance on Mental Illness

Relating to someone you love who has a mental illness can be difficult and frustrating, but there are strategies you can use to improve your communication with them. There may be a lot you don’t know about how your relative sees things when they’re symptomatic. These tips can help you build a stronger foundation for your relationship.

To get started on a better path in your relationship with your family member, first acknowledge that you can’t change them, only yourself. But the changes you make can improve your lives together. It’s critical to know as much as you can about their illness so you understand what they may be going through.

Don’t Buy Into Stigma

Be clear with yourself about who the person you care about really is. Even if we’re very close to someone with mental illness and advocate for his rights, we may also have our own preconceptions and false beliefs about mental illness.

We have to learn to separate the illness from the person.

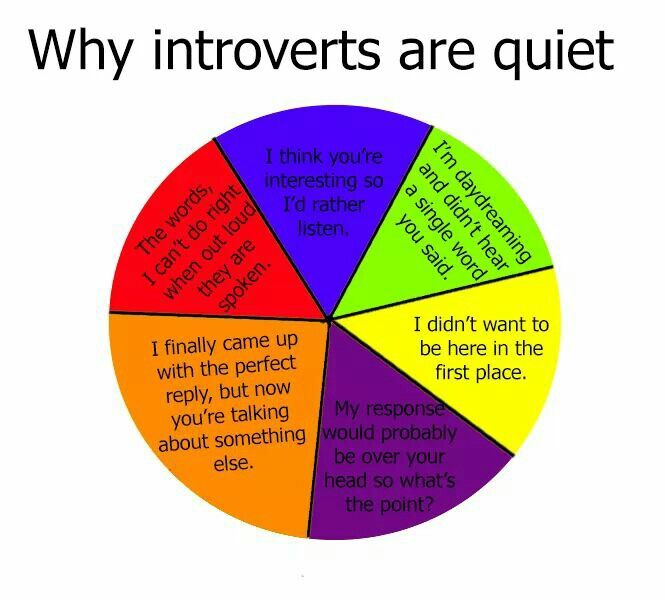

Understand Confusing Behavior

Because many of the symptoms of mental illness express themselves through social behavior, it’s natural to feel hurt by the symptoms. We tend to assume behavior is conscious and deliberate.

For example, when you invite your brother to dinner with friends and you feel embarrassed by his obsessive checking of whether he locked his car, you’re tempted to see him as someone who’s choosing to embarrass you. This may be how some friends and strangers see him, too—that’s the effect of stigma. When people around you see your relative this way, it can be hard to remember the truth: that he has an illness, and that the behavior is part of his symptoms. That doesn’t excuse cruel or violent behavior, but it’s an important reality to keep in mind.

See Opportunities for Improvement

You and your relative can still make conscious choices that improve your situation. You may agree to cooperate on communicating better, you may each work on keeping up friendships and other supportive relationships, you may each see a psychologist for talk therapy. The fact that you can control some things some of the time doesn’t negate the fact that the illness is real, not a character flaw, or anyone’s fault. Your relative’s capacity to make positive choices will depend on how severe her symptoms are at any given time.

The fact that you can control some things some of the time doesn’t negate the fact that the illness is real, not a character flaw, or anyone’s fault. Your relative’s capacity to make positive choices will depend on how severe her symptoms are at any given time.

Get Support from Other People

You know there's more to your loved one than her illness. You may value her sense of humor, her familiarity with your past, her ability to listen and her advice. When someone has a mental illness, she may feel it threatens her identity and self-respect. As with any other illness, your loved one will have periods when she's learning to cope with her illness’ challenges. During these times, she may seem self-absorbed and unable to give her usual attention and energy to others.

Both you and your relative will be better able to cope if you expand your own support network, beyond her. Strengthen your connections with other friends and family. This takes some pressure off your relative to help you as she did before she was ill. She can instead put that energy toward moving toward living well. At the same time, you may resent her less and feel strengthened by getting the social support you need.

She can instead put that energy toward moving toward living well. At the same time, you may resent her less and feel strengthened by getting the social support you need.

Expect Decent Behavior

Making adjustments to accommodate for your relative’s illness doesn’t erase the need for basic structures and expectations. Tell your relative the standards you need him to meet so you can live well together. Make sure your loved one knows that you see him as a whole person, and that you expect him to follow those standards.

Two of the most important standards to meet are that your home is a safe space and that you have a plan for what to do when safety of your loved one or the family is threatened. Prepare yourself and your family to handle crises. Tell your relative about the standards you expect for daily life. For example, that you won’t continue an interaction with your father if he starts screaming at you. Use the communication tips below to have more productive conversations with your relative.

Learn to Communicate Effectively

Developing good communication skills will improve all of your relationships, but they’re especially important when mental illness is in the mix. Effective communication is largely about building good habits. You can make choices that improve your chances of getting the results you want. Maybe you want to be able to ask your granddaughter to shower without getting into an argument, or tell your husband his smoking worries you without him giving you the cold shoulder.

A very good way to approach this is to use statements that give your perspective, rather than imposing perceived behavior. For example, try "I am concerned because you don't seem interested in what I'm saying.", instead of "You're not listening." Making thoughtful changes to how you communicate can move you closer to your goals.

See It from Their Perspective

Learn as much as you can about your relative’s illness and what they experience. Because of their symptoms, they may perceive things differently than you think. They may be feeling strong emotions like fear, have low self-esteem or be experiencing a delusion or hallucination. All this may be going on even if they don’t express it.

They may be feeling strong emotions like fear, have low self-esteem or be experiencing a delusion or hallucination. All this may be going on even if they don’t express it.

Put yourself in their shoes and try to think about how they’re feeling, rather than only what they’re saying. Adjusting your communication style with their possible experience in mind respects them, and makes it more likely that they’ll really hear and understand you.

If your friend or relative has done something that bothers you, give them the benefit of the doubt by first assuming the problem is not that they’re not motivated to change, but that they’re not yet able. It can be tempting to assume that the person is deliberately being difficult. Maybe your loved one doesn’t particularly like cleaning up, but she means well. She gets distracted in the moment and forgets to clean, even though she knows she’s supposed to. Ask her if something is making it harder for her to clean. If she simply forgets, would a sign on the kitchen door or fridge help? What does she think the sign should say? Ask her for ideas, so you’re cooperating on something.

You’ll notice that in this example, you’re still able to express the core of how you feel: you’re upset by the person’s actions, and you want them to behave differently because you’ll feel better. This method of communication is less likely to pile on the resentment—both theirs and yours—and more likely to get you both what you want.

Focus On Your Larger Goals

When you’re upset, try to remind yourself what your true, long-term goal is. It may be to live peacefully with your partner, or to encourage your child to eat more healthily. Your true goal is probably not to win an argument or to remind them of how much you put up with for their sake, but when we’re upset, we can get defensive.

Start conversations soon after something happens that upsets you, but after you’ve had a few minutes to cool down and talk calmly. You’ll be more likely to agree on recent facts, and you won’t let dissatisfactions build and worsen into resentment. Pursuing your larger goals doesn’t mean burying your feelings; it means communicating your most important feelings well.

Use Direct, Simple and Clear Language

To have a more productive conversation, start off on the right foot. Get the person’s attention first (“Can I talk to you?”). Cover one topic at a time and share small amounts of information at once (“I want to talk about tonight’s dinner”). Say exactly what you mean (“It’s been a long time since we cooked together, and I miss doing that. Would you help me make dinner tonight?”) rather than hinting at it (“You never do anything with me anymore”).

Describe What You Want and Why

State the facts of the situation, because usually that’s an area in which you can agree (“These forms are due back to your school tomorrow, and you haven’t filled them out yet.”). Say exactly what action you’re requesting the person to take, and how you’d feel if they’d do that (“Please read and sign them before we have lunch. I’d feel relieved knowing they’re done, and we can enjoy the rest of the afternoon knowing you’re ready for school”).

Describing a positive outcome can be very motivating. For example, you could say that you’d appreciate their help taking the trash out, or that if they joined you for a walk you’d be happy to be spending time together. Ask the person for suggestions on how to improve the situation; if they help create the idea, they’re more likely to give it a try.

For example, you could say that you’d appreciate their help taking the trash out, or that if they joined you for a walk you’d be happy to be spending time together. Ask the person for suggestions on how to improve the situation; if they help create the idea, they’re more likely to give it a try.

Taking Care of Yourself | NAMI: National Alliance on Mental Illness

To be able to care for the people you love, you must first take care of yourself. It’s like the advice we’re given on airplanes: put on your own oxygen mask before trying to help someone else with theirs. Taking care of yourself is a valid goal on its own, and it helps you support the people you love.

Caregivers who pay attention to their own physical and emotional health are better able to handle the challenges of supporting someone with mental illness. They adapt to changes, build strong relationships and recover from setbacks. The ups and downs in your family member’s illness can have a huge impact on you. Improving your relationship with yourself by maintaining your physical and mental health makes you more resilient, helping you weather hard times and enjoy good ones. Here are some suggestions for personalizing your self-care strategy.

Improving your relationship with yourself by maintaining your physical and mental health makes you more resilient, helping you weather hard times and enjoy good ones. Here are some suggestions for personalizing your self-care strategy.

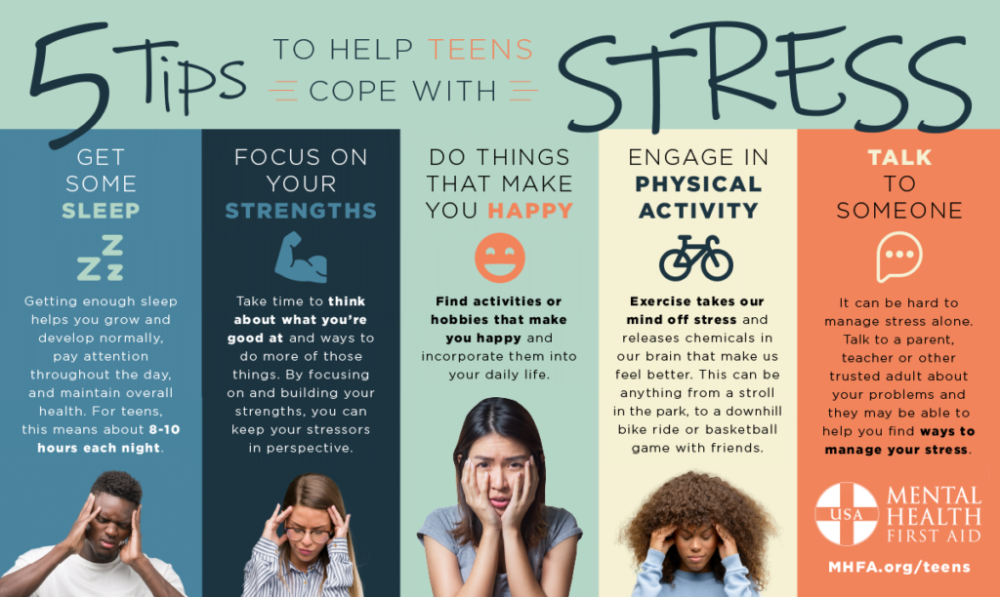

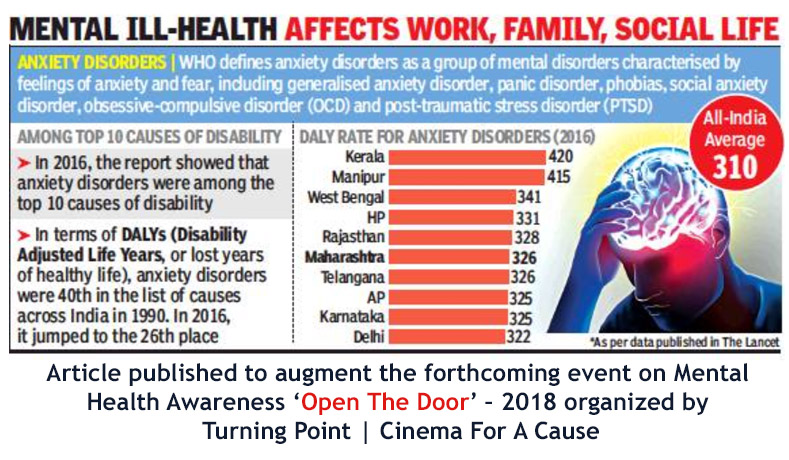

Understand How Stress Affects You

Stress affects your entire body, physically as well as mentally. Some common physical signs of stress include:

- Headaches

- Low energy

- Upset stomach, including diarrhea, constipation and nausea

- Aches, pains, and tense muscles

- Insomnia

Begin by identifying how stress feels to you. Then identify what events or situations cause you to feel that way. You may feel stressed by grocery shopping with your spouse when they’re symptomatic, or going to school events with other parents who don’t know your child’s medical history. Once you know which situations cause you stress, you’ll be prepared to avoid it and to cope with it when it happens.

Protect Your Physical Health

Improving your physical wellbeing is one of the most comprehensive ways you can support your mental health. You’ll have an easier time maintaining good mental habits when your body is a strong, resilient foundation.

You’ll have an easier time maintaining good mental habits when your body is a strong, resilient foundation.

- Exercise daily. Exercise can take many forms, such as taking the stairs whenever possible, walking up escalators, and running and biking rather than driving. Joining a class may help you commit to a schedule, if that works best for you. Daily exercise naturally produces stress-relieving hormones in your body and improves your overall health.

- Eat well. Eating mainly unprocessed foods like whole grains, vegetables and fresh fruit is key to a healthy body. Eating this way can help lower your risk for chronic diseases, and help stabilize your energy levels and mood.

- Get enough sleep. Adults generally need between seven and nine hours of sleep. A brief nap—up to 30 minutes—can help you feel alert again during the day. Even 15 minutes of daytime sleep is helpful. To make your nighttime sleep count more, practice good “sleep hygiene,” like avoiding using computers, TV and smartphones before bed.

- Avoid alcohol and drugs. They don’t actually reduce stress and often worsen it.

- Practice relaxation exercises. Deep breathing, meditation and progressive muscle relaxation are easy, quick ways to reduce stress. When conflicts come up between you and your family member, these tools can help you feel less controlled by turbulent feelings and give you the space you need to think clearly about what to do next.

Recharge Yourself

When you’re a caregiver of someone with a condition like mental illness, it can be incredibly hard to find time for yourself, and even when you do, you may feel distracted by thinking about what you “should” be doing instead. But learning to make time for yourself without feeling you’re neglecting others—the person with the illness as well as the rest of your family—is critical.

Any amount of time you take for yourself is important. Being out of “caregiver mode” for as little as five minutes in the middle of a day packed with obligations can be a meaningful reminder of who you are in a larger sense. It can help keep you from becoming consumed by your responsibilities. Start small: think about activities you enjoyed before becoming a caregiver and try to work them back into your life. If you used to enjoy days out with friends, try to schedule a standing monthly lunch with them. It becomes part of your routine and no one has to work extra to make it happen each month.

It can help keep you from becoming consumed by your responsibilities. Start small: think about activities you enjoyed before becoming a caregiver and try to work them back into your life. If you used to enjoy days out with friends, try to schedule a standing monthly lunch with them. It becomes part of your routine and no one has to work extra to make it happen each month.

The point is not what you do or how often you do it, but that you do take the time to care for yourself. It’s impossible to take good care of anyone else if you’re not taking care of yourself first.

Practice Good Mental Habits

Avoid Guilt

Try not to feel bad about experiencing negative emotions. You may resent having to remind your spouse to take his medication, then feel guilty. It’s natural to think things like “a better person wouldn’t be annoyed with their spouse,” but that kind of guilt is both untrue and unproductive. When you allow yourself to notice your feelings without judging them as good or bad, you dial down the stress and feel more in control. When you feel less stressed, you’re better able to thoughtfully choose how to act.

When you feel less stressed, you’re better able to thoughtfully choose how to act.

Notice the Positive

When you take the time to notice positive moments in your day, your experience of that day becomes better. Try writing down one thing each day or week that was good. Even if the positive thing is tiny (“It was a sunny day”), it’s real, it counts and it can start to change your experience of life.

Gather Strength from Others

NAMI support groups exist to reassure you that countless other people have faced similar challenges and understand your concerns. Talking about your experiences can help. The idea that you can, or should be able to, “solve” things by yourself is false. Often the people who seem like they know how to do everything are actually frequently asking for help; being willing to accept help is a great life skill. If you’re having trouble keeping track of your sister’s Medicaid documents and you’ve noticed your coworker is well-organized, ask them for tips about managing paperwork.

You may feel you don’t have the time to stay in touch with friends or start new friendships. Focus on the long-term. If you can meet up with a friend once a month, or go to a community event at your local library once every two months, it still helps keep you connected. It also gives you the chance to connect with people on multiple levels. Being a caregiver is an important part of your life, but it’s not the whole story.

Family and mental illness. psychological problems and ways to solve them.

Feedback form

Question about the work of the siteQuestion to a specialistQuestion to the administration of the clinic

email address

Name

Message text

Regional charitable public organization

Center for socio-psychological

and information support

Family and Mental Health

Mental Health Research Center of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences

A. I. Tsapenko, D.M. Shanaeva

I. Tsapenko, D.M. Shanaeva

FAMILY AND MENTAL ILLNESS

psychological problems

and ways to solve them

2nd edition, revised

MOSCOW - 2008

UDC 616.89-08

LBC 88.4+56.14

Ts17

Tsapenko A.I., Shanaeva D.M.

C17 Family and mental illness: psychological problems and ways to solve them / Ed. V.S. Yastrebova. - 2nd ed. revised – M.: MAKS Press, 2008. – 64 p.

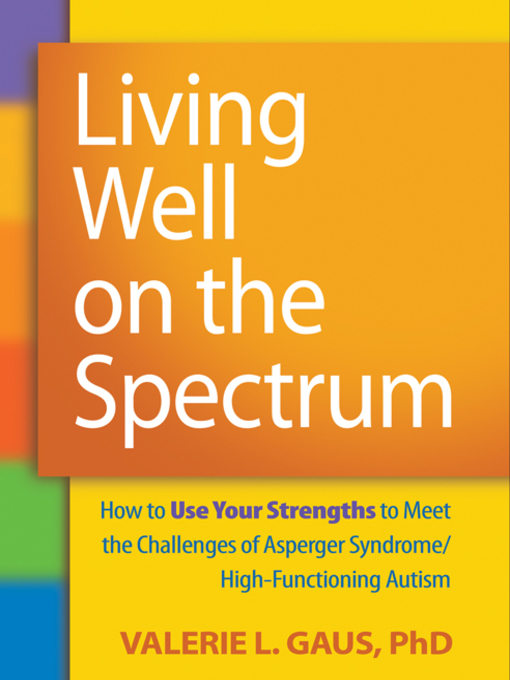

ISBN 978-5-317-02343-0

The work offered to readers is another popular manual published under the auspices of the Public Council on Mental Health. The topic of the published Handbook is timely and especially relevant for two reasons. In the Russian popular scientific literature, the issues of psychological problems that arose in the families of the mentally ill were practically not discussed before. In addition, when organizing the treatment of people with mental disorders, domestic science and practice proceeded from the priority of drug treatment methods with the subsequent involvement of these people in the range of rehabilitation measures. The patient's family, with its many psychological problems, remained outside of these activities. As foreign experience and recent domestic practice shows, today the situation has changed dramatically. The authors of the manual in an accessible form describe the range of basic psychological problems that arise in the families of the mentally ill. A distinctive feature of this work from similar publications is that its authors analyze not only the features of the relationship of family members with their sick relative, offer ways to solve problems that arise, but also give a qualified assessment of the relationship between parents and children in ordinary families, offer recommendations for the normalization of these relations. It follows from the foregoing that the allowance is intended not only for the families of the so-called help users, to which it is customary to include patients and their relatives, but also for many other families in which the establishment of harmonious relations between their members is required.

The patient's family, with its many psychological problems, remained outside of these activities. As foreign experience and recent domestic practice shows, today the situation has changed dramatically. The authors of the manual in an accessible form describe the range of basic psychological problems that arise in the families of the mentally ill. A distinctive feature of this work from similar publications is that its authors analyze not only the features of the relationship of family members with their sick relative, offer ways to solve problems that arise, but also give a qualified assessment of the relationship between parents and children in ordinary families, offer recommendations for the normalization of these relations. It follows from the foregoing that the allowance is intended not only for the families of the so-called help users, to which it is customary to include patients and their relatives, but also for many other families in which the establishment of harmonious relations between their members is required. Many provisions of the Handbook can be used in the practical activities of psychiatric workers.

Many provisions of the Handbook can be used in the practical activities of psychiatric workers.

UDC 616.89-08

LBC 88.4+56.14

The manual was published with the support of a pharmaceutical company

ELI LILLY VOSTOK S.A.

ISBN 978-5-317-02343-0 © A.I. Tsapenko, D.M. Shanaeva, 2007

© RBPA "Family and Mental Health", 2007

© A.I. Tsapenko, D.M. Shanaeva, 2008, amended

© RBPA "Family and Mental Health", 2008,

with changes

TsAPENKO Anna Igorevna

SHANAEVA Dina Muratovna

FAMILY AND MENTAL ILLNESS

psychological problems

and ways to solve them

Preparation of the original layout:

MAKS Press Publishing House

MAKS Press LLC Publishing House

License ID N 00510 dated 01.12.99

Signed for publication on 04.05.2008

Format 60x90 1/16. Conditions.print.l. 4.0. Circulation 500 copies. Order 224.

119992, GSP-2, Moscow, Leninskiye Gory, MSU. M.V. Lomonosov,

2nd educational building, 627 k.

Tel. 939-3890, 939-3891. Tel/Fax 939-3891.

Download file (PDF, ~500 Kb)

Information for families with mentally ill people

We, psychiatrists, often ask relatives of people with "our" illnesses what they most often lack in their situation. Often I hear answers: “Information”, “Understanding”.

The family has always existed in the social environment that every person needs, whether he is healthy or ill (even with a mental disorder). At the same time, he often falls out of it. And every individual (healthy or sick) in this environment has rights and obligations. The sick person has a special claim to help and a precautionary attitude, like other members of his family, who also have the same, but they cannot be left unattended for a long time, unless he (the sick person) does not want to risk the breakdown of family ties. In such a special situation, help from outside is required, and then we will talk about overcoming crises, about treatment, about rehabilitation, about the social security of the patient, or about the financial and moral hardships of relatives.

The common notion that “a person, once mentally ill, remains ill forever” is erroneous. It often happens that the disease disappears again, or at least it can be successfully overcome.

It is also encouraging that in recent decades significant progress has been made in the research and treatment of mental illness, thanks to the emergence of new drugs.

Erroneous sentences include the notion that patients with mental (mental) disorders should be equated with "mentally retarded persons" and during fascism they were exterminated by the thousands. This is also completely false. As one look at the many mentally ill and yet talented people who have made outstanding contributions to art and achieved success in other fields shows: Fyodor Dostoevsky, Hans Christian Andersen, Franz Schubert, Alfred Schnittke, Salvador Dali, Leonardo da Vinci, Nicolo Paganini, Johann Sebastian Bach, Sigmund Freud, Rudolf Diesel, Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Claude Henri Saint-Simon, Immanuel Kant, Charles Dickens, Albrecht Dürer, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Lope de Vega, Nostradamus, Jean Baptiste Molière, Francisco Goya, Honore de Balzac, Friedrich Nietzsche and others

Today, the concept of "mentally ill" is no longer used, but it is said about "mental illness" and "mentally ill" in order to clarify the change of views, knowledge. Despite the existing, fortunately, positive processes, a relatively high percentage of patients suffer from relapses or remain impaired for a long time. This means that the lives of families where there are such people proceed differently than expected, and plans and desires remain in the background, and all participants must go through painful processes of adaptation, learning, until eventually, perhaps, balance is restored.

Despite the existing, fortunately, positive processes, a relatively high percentage of patients suffer from relapses or remain impaired for a long time. This means that the lives of families where there are such people proceed differently than expected, and plans and desires remain in the background, and all participants must go through painful processes of adaptation, learning, until eventually, perhaps, balance is restored.

This is based on the experience of families with such relatives. Well, if you are a relative only recently and have come into conflict with a mental illness, then you will probably find these descriptions depressing. However, perhaps in this you will gain your own experience, and your suffering will be justified.

We, the professionals, would like to give information and evoke understanding without being delusional, and point out the possibilities for assistance that you can seek without hiding problems - sometimes out of shame, more often out of good will, in order to somehow spare the patient or cause greater understanding from the outside world. The flip side of this behavior is that problems and ailments are underestimated and not taken seriously - "it's just the psyche ...", as many say and at the same time believe: this is not so bad and if you pull yourself together, everything will work out . The consequences of such views can be completely unforeseen and are the basis for insufficient assistance, which families usually complain about.

The flip side of this behavior is that problems and ailments are underestimated and not taken seriously - "it's just the psyche ...", as many say and at the same time believe: this is not so bad and if you pull yourself together, everything will work out . The consequences of such views can be completely unforeseen and are the basis for insufficient assistance, which families usually complain about.

It is appropriate to talk about the conflicting feelings of relatives towards the mentally ill. On the one hand, they treat him with understanding and want to protect him, and on the other hand, irritation and dissatisfaction may appear if, as a result of the patient’s behavior, all family life goes haphazardly, although it is known that one must always restrain oneself in illness. Some relatives take the side of the patient and oppose the "rest of the world", others act quite the opposite: they get so upset and nervous that they contribute to the isolation of the sick person, while others hesitate between understanding and sympathy, on the one hand, and refusal, and anger , on the other hand.

Patients themselves, doctors, support staff participate in this game, and the "stumbling block" adjoins either one or the other. Everything in this complex and constantly changing situation is understandable, but this certainly does not make it easier for a solution that is acceptable to all participants.

The motto of the German Relatives Association brings this goal together in the thesis: "In order to live together with the mentally ill, one must be self-confident and in solidarity." However, there is an experience acquired by many relatives before you: "Your most important assistant is yourself!". Therefore, it is so important that you take care not only of the patient, but also of yourself.

The first step in self-help is gathering information. The one who receives more information about the disease can better manage it and overcome its consequences. Relatives can turn to doctors, read specialized literature, etc. However, when it comes to the numerous and dubious issues that arise in daily communication with the mentally ill, the "expert assessment" of other relatives is an indispensable source of help and Information.

All of the above can be summarized in ten basic rules, such a "game" is worth the candle. Thanks to her, we can all avoid stress and conflict in the family and ensure peace in our relationships with each other.

So, 10 basic rules to avoid stress and conflict in the family and ensure peace in relationships with each other:

1. Try to limit yourself to the most important things and at first close your eyes to some behavioral problems.

2. Leave the patient alone - excessive care will not do him or us any good. Do not protect him or take care of him beyond measure and give him as much independence as possible. However, it is important to let him know that you are at his disposal at any moment when he needs you.

3. Give yourself and the patient time, especially after the acute phase of the disease. Don't wait impatiently for a "quick leap forward" but promote small steps and enjoy them.

4. Match your expectations and aspirations to the situation, avoid overstimulation and do not make excessive demands.

5. If you want to do something (for example, tidy up your room), first think about how to act delicately and wait for the most favorable moment. Express your thoughts clearly and concisely. If you act with irritation or direct pressure, then the chances of achieving the intended goal decrease, and we create additional stress for ourselves.

6. Consider that the symptoms of illness are not an expression of ill will, but an attempt to cope with a disturbed lifestyle.

7. Reflect on the fact that the sick person himself is trying to protect the still healthy parts of his body from the disease and help him strengthen and develop them.

8. Take care of a quiet way of life - even if it is sometimes difficult. Work hard to minimize conflicts and strained relationships in the family. Ask yourself if a walk in the fresh air will help you get out of a difficult situation or if you need to give free rein to your own feelings.

9. Take a well-thought-out attitude towards medicines.