Emotion personality disorder

What is borderline personality disorder (EUPD)?

This section has information on borderline personality disorder (BPD), including symptoms, causes and treatments. This information is for people affected by BPD in England who are 18 or over. It’s also for their carers, friends and relatives and anyone interested in this subject.

Borderline personality disorder is also called emotionally unstable personality disorder (EUPD) and emotional intensity disorder (EID). In this factsheet, we call it BPD as this is still the most common term for the condition. But we appreciate that all 3 terms can be controversial.

If you would like more advice or information you can contact our Advice and Information Service by clicking here.

Download Borderline personality disorder (BPD) factsheet

- Overview

- About

- Symptoms

- Causes and treatment

- Problems and self-care

- Information for carers

- Further reading

- Useful contacts

Overview

- BPD means that you feel strong emotions that you struggle to cope with.

You may feel upset or angry a lot of the time.

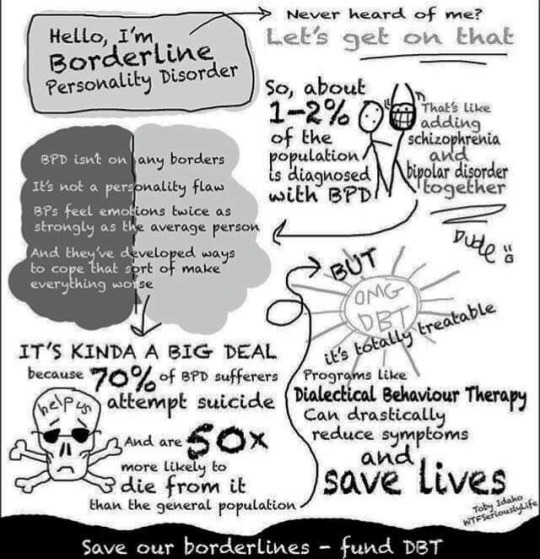

- Around 1 in 100 people live with BPD.

- There are different reasons why people get BPD. A lot of people who live with a diagnosis of BPD have had traumatic experiences in their childhood.

- If you are someone living with a diagnosis of BPD, it is more likely that you will self-harm. And have challenges with relationships, alcohol or drugs. There is help available.

- There are different ways to treat BPD. The NHS should normally offer you therapy.

Need more advice?

If you need more advice or information you can contact our Advice and Information Service.

Contact us Contact us

About

What is borderline personality disorder (BPD)?

Everyone has different ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving. It is these thoughts, feelings, and behaviours that make up our ‘personality’. These are often called our traits. They shape the way we view the world and the way we relate to others. By the time we are adults these will make us part of who we are.

It is these thoughts, feelings, and behaviours that make up our ‘personality’. These are often called our traits. They shape the way we view the world and the way we relate to others. By the time we are adults these will make us part of who we are.

You can think of your traits as sitting along a scale. For example, everyone may feel emotional, get jealous, or want to be liked at times. But it is when these traits start to cause problems that you may be diagnosed as having a personality disorder.

BPD is a type of ‘personality disorder’.

BPD can affect how you cope with life, manage relationships, and feel emotionally. You may find that your beliefs and ways of dealing with day-to-day life are different from others. You can find it difficult to change them.

You may find your emotions confusing, tiring, and hard to control. This can be distressing for you and others. Because it is distressing, you may find that you develop other mental health problems like depression or anxiety. You may also do other things such as drink heavily, use drugs, or selfharm to cope.

You may also do other things such as drink heavily, use drugs, or selfharm to cope.

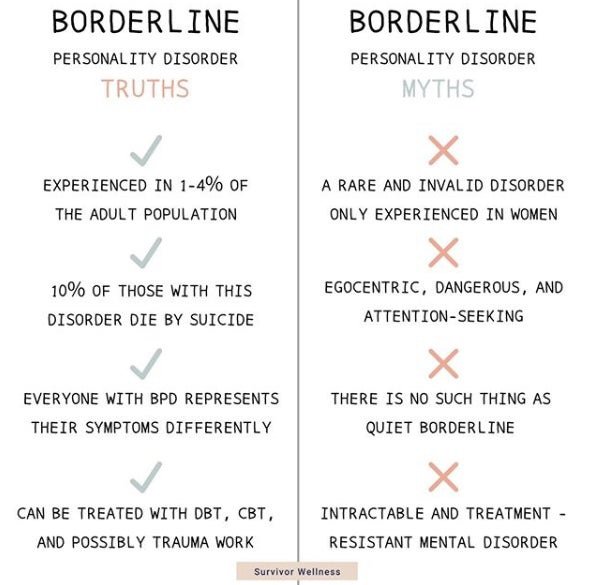

Research shows that around 1 in 100 people live with BPD. It seems to affect men and women equally, but women are more likely to have this diagnosis. This may be because men are less likely to ask for help. BPD is sometimes called emotionally unstable personality disorder (EUPD). Some people feel that this describes the illness better.

Some people who live with BPD think that the name is insulting or makes them feel labelled. Doctors don’t use this term to make you feel judged or suggest that the illness is your fault. It is meant to describe the way the illness develops. It’s important to remember this is a health condition. And not a judgement of your character or you as a person.

Symptoms

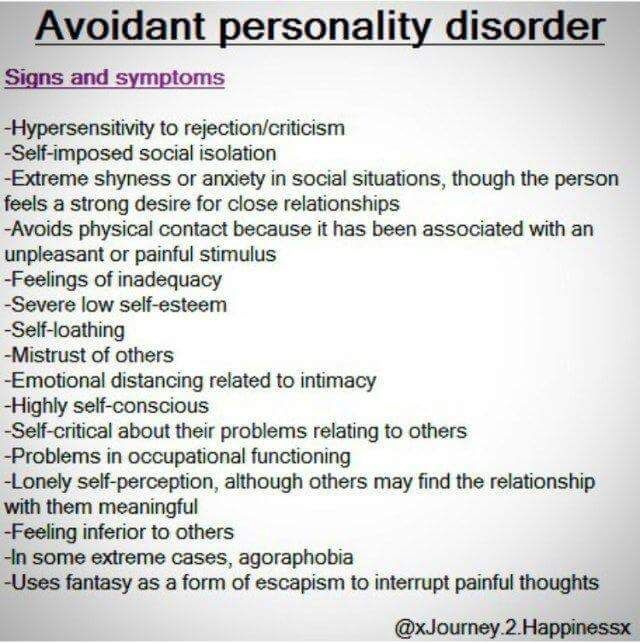

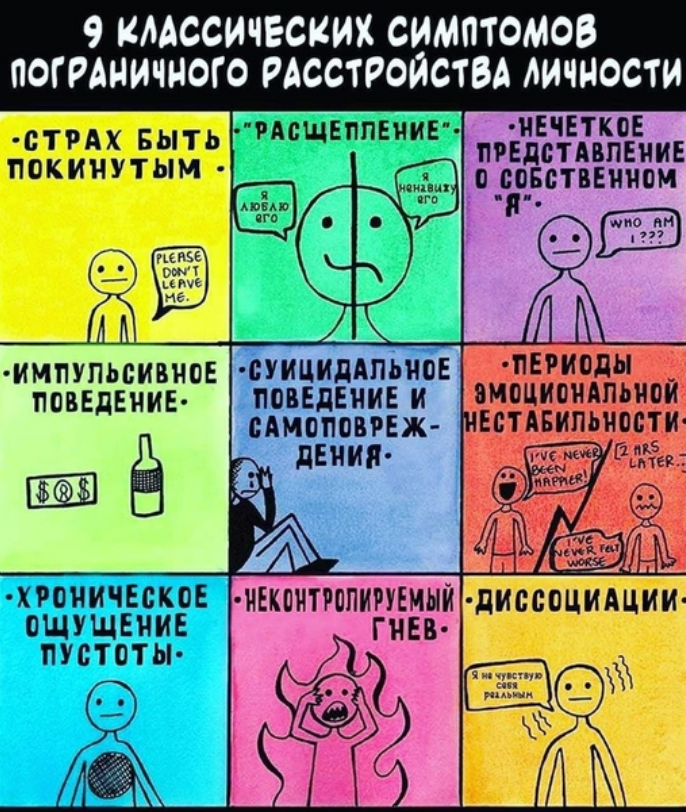

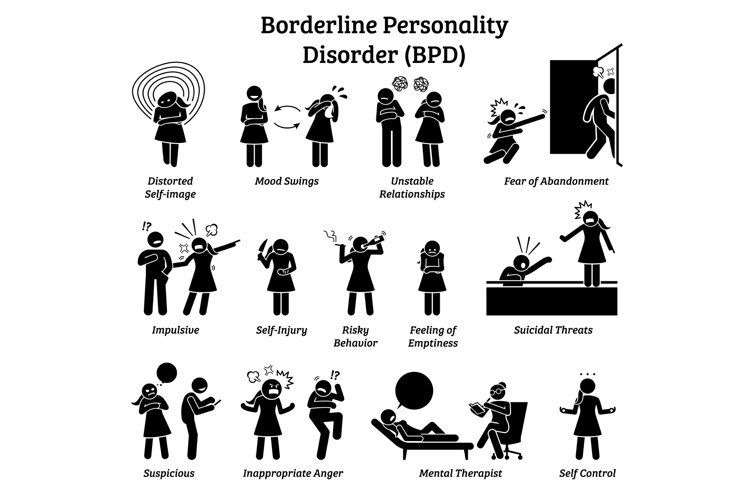

What are the symptoms of BPD?

Everyone will experience BPD differently. If you live with BPD, you may have difficulties with:

- being impulsive. This means that you like to do things on the spur of the moment,

- feeling bad about yourself,

- controlling your emotions,

- self-harming,

- suicidal thoughts and attempts to take your own life,

- feeling 'empty’,

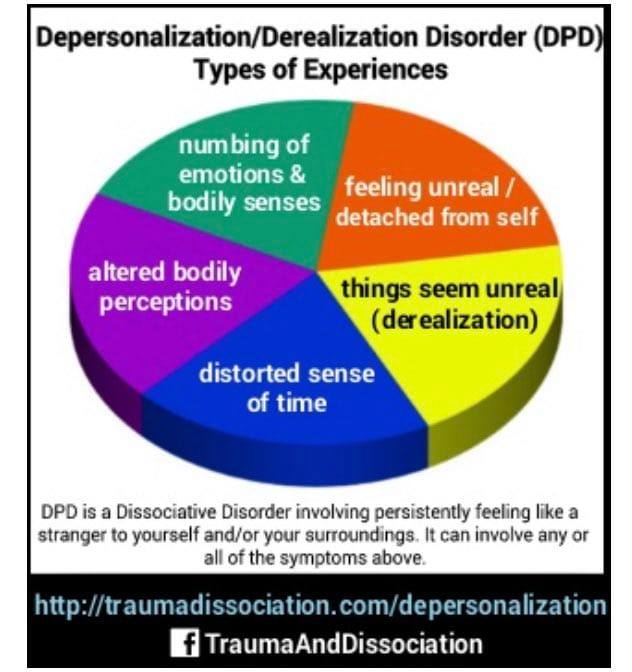

- dissociation.

This could be a feeling of being disconnected from your own body. Or feeling disconnected from the world around you.

This could be a feeling of being disconnected from your own body. Or feeling disconnected from the world around you. - identity confusion. You might not have a sense of who you are.

- feeling paranoid or depressed,

- hearing voices or noises when you are stressed, and

- intense but unstable relationships with others.

Not everyone will experience all these symptoms.

Sam's Story

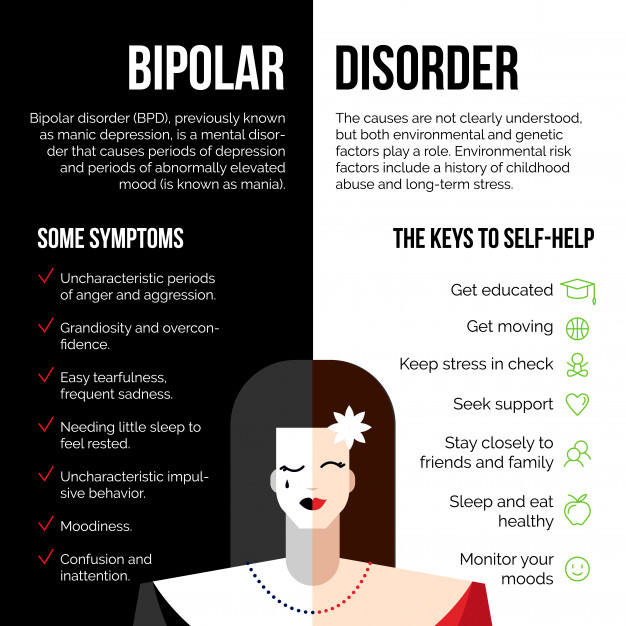

Many people who live with BPD will also experience other mental health problems. Such as depression, anxiety, eating disorders, PTSD and alcohol or drug misuse. People who live with BPD can also be diagnosed with bipolar disorder. The symptoms of bipolar disorder can often be confused with those of BPD.

You can find more information about:

- Personality disorders by clicking here.

- Dissociation and dissociative disorders by clicking here.

- Self-harm by clicking here.

- Anxiety disorders by clicking here.

- Depression by clicking here.

- PTSD by clicking here.

- Drugs, alcohol and mental health by clicking here.

- Bipolar disorder by clicking here.

Causes & treatment

What causes BPD?

There’s no single reason why some people develop borderline personality disorder (BPD). Professionals can’t use things like blood tests or brain scans to help diagnose people.

It is thought that BPD may be caused by a combination of factors:

- Genetics – you may be more vulnerable to BPD if a close family member also lives with BPD. There is no evidence though of a particular gene being responsible for BPD.

- Brain chemicals – problems with levels of your brain chemicals, particularly serotonin.

- Brain development – many people who live with BPD have smaller, or more active, parts of their brain. These parts of the brain are affected by your early upbringing.

And can affect the regulation of your emotions, behaviour and self-control. They can also affect you planning and decision making.

And can affect the regulation of your emotions, behaviour and self-control. They can also affect you planning and decision making. - Environmental factors – a number of environmental factors seem to be common with people who live with BPD. These can include:

- experiencing abuse,

- experiencing long-term fear or distress as a child,

- being neglected by 1, or both, of your care-givers as a child, and

- growing up with a family member who had a serious mental health condition. Such as bipolar disorder or a problem with alcohol or drugs.

How can I get help if I think I have BPD?

The first step to get help is to speak to your GP.

Your GP will look at different things when deciding how best to help you. So, it can help to keep a record of your symptoms. This can help you and your GP to understand what difficulties you are facing. It may help if you keep a record of:

- how distressed you feel,

- any risks to yourself or other people, and

- details of anything you have done to try and reduce your levels of anxiety and distress.

Your GP can’t diagnose BPD. Only a psychiatrist should make a formal diagnosis. A psychiatrist is part of the community mental health team (CMHT). If your GP feels that you need more support they will refer you to the CMHT.

What happens if my GP refers me to the community mental health team (CMHT)?

There may be a waiting list to see your CMHT. You can ask your GP, or contact the CMHT, about how long the waiting list is.

When you have your first appointment with the CMHT they will ask you questions to understand how your mental health is affecting you. They will talk to you about:

- how you manage your day to day life, relationships and work,

- coping strategies that you use,

- your strengths,

- areas in your life that you find difficult.

- any other mental health problems you may have,

- any other social problems that you may have,

- any social care and support needs you may have,

- any support you may need in staying in your job, or finding a job,

- any psychological treatment you may need.

This is also known as ‘talking therapy’, and

This is also known as ‘talking therapy’, and - the needs of any dependent children that you have.

How will the CMHT decide if I have BPD?

Psychiatrists use the following guidelines to decide if you have a mental disorder.

- International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), produced by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), produced by the American Psychiatric Association.

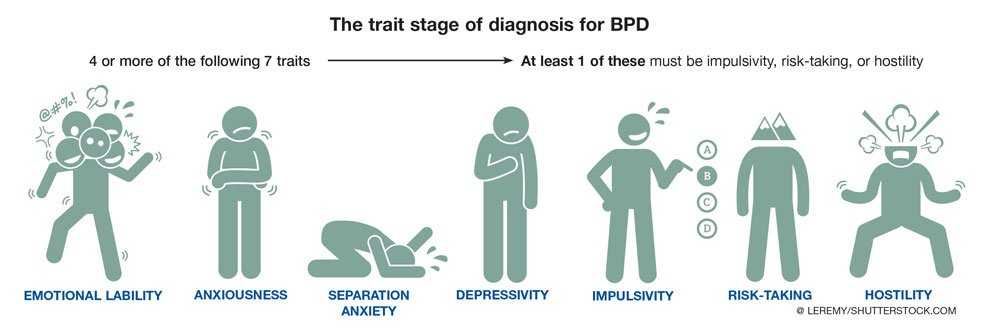

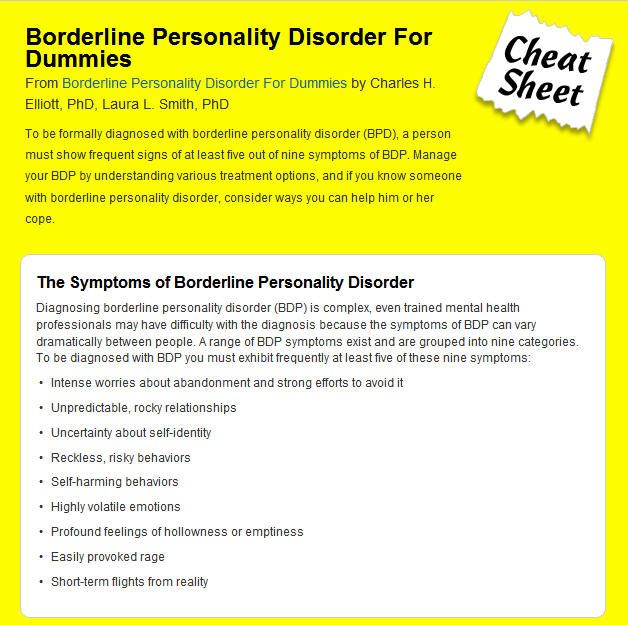

The guidelines tell your psychiatrist what to look for. They will diagnose you with BPD if you have at least five of the symptoms below.

- Extreme reactions to feeling abandoned.

- Unstable and intense relationships with others

- Confused feelings about your self-image or your sense of identity.

- Being impulsive in ways that could be damaging. For example, spending, sex, substance abuse, reckless driving, and binge eating

- Regular self-harming, suicidal threats or behaviour.

- Long lasting feelings of emptiness or being abandoned.

- Inappropriate or intense anger. And difficulty controlling your anger. For example, losing your temper or getting into fights.

- Intense, highly changeable moods.

- Paranoid thoughts, or severe dissociation, when you’re stressed. Dissociation is a feeling of being disconnected from your own body. Or feeling disconnected from the world around you

You can find more information about:

- NHS Mental Health Teams (MHTs) by clicking here.

- Dissociation and dissociative disorders by clicking here.

What treatment should the NHS offer me?

You can check what treatment and care is recommended for BPD on the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) website. NICE produce guidelines for how health professionals should treat certain conditions. You can download these from their website at:

www.nice.org.uk.

The NHS does not have to follow these recommendations. But they should have a good reason for not following them.

But they should have a good reason for not following them.

People who live with BPD have sometimes been excluded from NHS services because of their diagnosis. But the NHS should not refuse to give you specialist help because of your diagnosis. They should have services to support people with BPD.

If your local NHS doesn’t offer you appropriate treatment then there are things that you can do. For information about your options please see further down this page.

Should I be offered medication?

There is no medication to treat BPD. But your doctor may offer you medication if you also have symptoms of another mental illness like anxiety or depression.

What psychological treatment should I be offered?

Psychological therapy is also known as ‘talking therapy’. There are lots of different types of talking therapies and your doctor should talk to you about what is available, how it may help you and what type of therapy you would like.

We have included details below of some of the therapies that your doctor may use. But these are not available everywhere. And your doctor may recommend other types of talking therapy.

But these are not available everywhere. And your doctor may recommend other types of talking therapy.

Your doctor will also think about:

- how much BPD is affecting you,

- how much you are willing to engage with therapy,

- if you want to change how react to your thoughts and feelings,

- if you will be able to work effectively with a counsellor, and

- the personal and professional support that is available.

The therapy you are offered should last at least 3 months. If your doctor decides that talking therapies are not suitable, they should explain why.

Dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT)

The guidance says that the NHS should offer DBT to women with BPD if they self-harm regularly.

DBT is a type pf therapy specifically designed to treat people with BPD. The goal of BPD is to help you accept that your emotions are real and acceptable. And to challenge how you respond to those emotions by being open to ideas and opinions which are different to your own.

DBT usually involves weekly individual and group sessions. And you should be given an out-of-hours contact number to call if your symptoms get worse.

DBT is based on teamwork. You'll be expected to work with your therapist and the other people in your group sessions. In turn, the therapists work together as a team.

Mentalisation-based therapy (MBT)

Mentalisation means the ability to think about thinking. This means looking at your own thoughts and beliefs. And working out if they are helpful and realistic.

This type of therapy also helps you to recognise that other people have their own thoughts, emotions and beliefs. And that you may not always understand these. The therapy also helps you to think about how your actions might affect what other people think or feel.

A course of MBT usually lasts around 18 months. You may first be offered MBT in a hospital as an inpatient. The treatment usually consists of daily individual sessions with a therapist and group sessions with other people with BPD.

Some hospitals and specialist centres like you to remain in hospital whilst you are having MBT. But others recommend that you leave the hospital after a certain period of time but remain being treated as an outpatient. This means that you will visit the hospital regularly.

Arts therapies

There are different types of arts of creative therapies. These include:

- art therapy,

- drama therapy,

- music therapy, and

- dance movement therapy.

These therapies can be offered individually but they are often done in groups. Sessions are usually weekly. These therapies can be helpful to people who find it hard to talk about their thoughts and feelings.

Therapeutic communities

Therapeutic communities are not a treatment themselves. They are places you can go to have treatment. Most therapeutic communities are residential. They help people with long-term emotional problems, and a history of self-harming, by teaching them skills to help them have better relationships.

These communities often set strict rules on behaviour. For example, no drinking alcohol, no violence and no attempts at self-harming.

You may stay for a few weeks or months, or you may visit for just a few hours a week. You may have group therapy and self-help sessions. You would be expected to take part in other activities to improve your self-confidence and social skills. These activities may include household chores, games and preparing meals.

Therapeutic communities vary a lot because they are often run by the people who use them. And they shape them based on what they want to achieve.

What happens if the CMHT can’t successfully treat me?

You may get support from a specialist service if your symptoms are getting worse. These specialist services are also called ‘Tier 3’ or ‘Tier 4’ services.

These services are not available in all NHS Trusts. And they can be difficult to access. You can speak to your CMHT and if they can refer you to a specialist service.

You can find more information about Tier 3 and Tier 4 services in our factsheet ‘Second Opinions’ by clicking here.

What treatment should I get if I am in crisis?

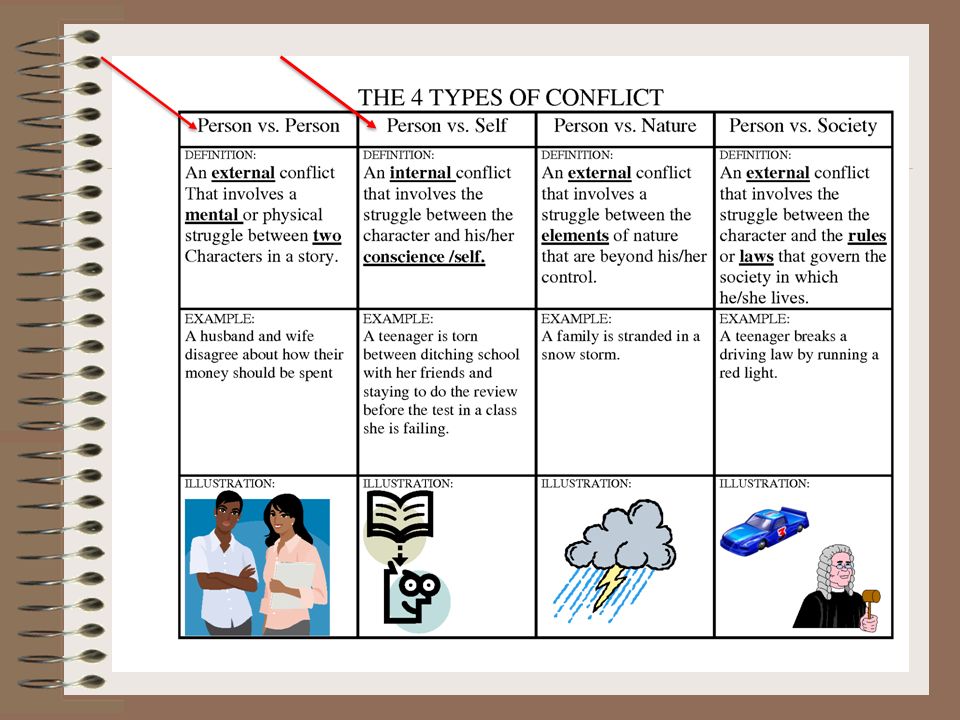

A mental health crisis is when you need urgent help. You may be feeling suicidal or wanting to self-harm. And you don’t think that you can use your normal coping strategies to stop yourself from acting on your feelings.

If you have a diagnosis of BPD but are not under the care of your local community mental health team (CMHT), then you should speak to your GP. Your GP should:

- assess the level of risk to yourself or others,

- talk to you about previous mental health crises. And what skills you have used to cope with these,

- help you to use these skills and focus on your current problems,

- help you to identify changes which you can put in place to manage your current problems, and

- offer you a follow-up appointment.

If you are already under the CMHT, or a specialist service, then you should have a care plan. The care plan should include a crisis plan that you can follow. Your crisis plan is written by you and your mental health team. It should include:

The care plan should include a crisis plan that you can follow. Your crisis plan is written by you and your mental health team. It should include:

- what triggers might lead to a mental health crisis,

- self-management skills which you have used before and find helpful,

- details of how to access help if the self-management skills aren’t helping. This should include a list of support numbers for out-of-hours teams and crisis teams.

Your doctor may think about offering you sedative medication. Sedatives can help you feel more relaxed. But your doctor should not give you sedatives for more than a week.

Some people find it helpful to contact emotional support lines during a mental health crisis. There is a list of contact numbers at the bottom of this page.

You can find more information about ‘Getting help in a crisis’ by clicking here.

Problems & self-care

What risks and complications can BPD cause?

Self-harm

It is common for people who live with BPD to self-harm. Some people find self-harming can help them to deal with painful feelings. But it can cause serious injury, scars, infections, or accidental death. A big focus of BPD treatment is to find other ways to deal with painful emotions.

Some people find self-harming can help them to deal with painful feelings. But it can cause serious injury, scars, infections, or accidental death. A big focus of BPD treatment is to find other ways to deal with painful emotions.

You can find more information about ‘Self-harm’ by clicking here.

Suicide

People who live with BPD are more at risk of suicide or of attempting suicide. Most people who live with BPD who feel suicidal will feel more positive within a few hours. So it is important to use techniques to try and distract from the strong suicidal feelings.

You can find more information about ‘Suicidal thoughts’ by clicking here.

Drugs and alcohol

People who live with BPD may:

- behave impulsively,

- drink too much alcohol,

- misuse prescription medication, or

- take illegal drugs.

You are more likely to die by suicide if you are also using alcohol. So If you are feeling suicidal you can help keep yourself safer by making sure that you don’t use alcohol.

You may be at an increased risk of becoming dependent on alcohol or drugs if you have BPD.

If you drink a lot of alcohol or use drugs, you may find it difficult to get treatment for BPD. But NICE guidelines state that you should be referred to a service that can help with your substance use. And you should be able to continue with BPD treatment where appropriate.

You can find more about ‘Drugs, alcohol and mental health’ by clicking here.

Impulsive behaviours

When people make decisions quickly without thinking about the consequences, doctors call this ‘impulsive’. This can include driving erratically or having multiple sexual partners. Or spending money on things you can't afford or don't need.

If impulsive behaviour leads you to have debt problems you can find more support and information at: www.mentalhealthandmoneyadvice.org.

What if I am not happy with my treatment?

If you are not happy with your treatment you can:

- talk to your doctor about your treatment options,

- ask for a second opinion,

- get an advocate to help you speak to your doctor,

- contact Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS) and see whether they can help, or

- make a complaint.

There is more information about these options below.

Treatment options

You should first speak to your doctor about your treatment. Explain why you are not happy with it. You could ask what other treatments you could try.

Tell your doctor if there is a type of treatment that you would like to try. Doctors should listen to your preference. If you are not given this treatment, ask your doctor to explain why it is not suitable for you.

Second opinion

A second opinion means that you would like a different doctor to give their opinion about what treatment you should have. You can also ask for a second opinion if you disagree with your diagnosis.

You don’t have a right to a second opinion. But your doctor should listen to your reason for wanting a second opinion.

Advocacy

An advocate is independent from the NHS. They are free to use. They can be useful if you find it difficult to get your views heard. There are different types of advocates available.

Community advocates can support you to get a health professional to listen to your concerns. And help you to get the treatment that you would like. This type of service doesn’t exist in all areas.

An NHS Complaints Advocate can help you if you want to complain about the NHS. This service exists in all areas.

To search for services, you can try the following.

- Use an internet search engine – use search terms like ‘advocacy Leicestershire’ or ‘mental health advocacy Devon’.

- Ask a support worker or key worker, if you have one.

- Ask your local council whether they have a list.

- Ask your local NHS Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS) whether they have a list of local advocacy services.

- Look at local service directories. You can sometimes find useful directories of mental health services online.

- Get in touch with organisations that offer advocacy such as Rethink Mental Illness, Mind, The Advocacy People, Voiceability and POhWER.

The Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS)

PALS is part of the NHS. They give information and support to patients.

You can find your local PALS’ details through this website link:

www.nhs.uk/Service-Search/Patient-advice-and-liaison-services-(PALS)/LocationSearch/363.

You can find out more about:

- Medication. Choice and managing problems by clicking here.

- Second opinions by clicking here.

- Advocacy by clicking here.

- Complaining about the NHS or social services by clicking here.

What can I do to manage my symptoms?

You can learn to manage your symptoms by looking after yourself. Selfcare is how you take care of your diet, sleep, exercise, daily routine, relationships and how you are feeling.

Lifestyle

Making small lifestyle changes can improve your wellbeing and can help your recovery.

Routine helps many people with their mental wellbeing. It will help to give a structure to your day and may give you a sense of purpose. This could be a simple routine such as eating at the same time each day, going to bed at the same time each day and buying food once per week.

This could be a simple routine such as eating at the same time each day, going to bed at the same time each day and buying food once per week.

Breathing exercises

Breathing exercises can help to calm you when you are feeling anxious. You will get the most benefit if you do them regularly, as part of your daily routine.

There is more information about breathing exercises in the further reading section at the bottom of this page.

Support groups

You could join a support group. A support group is where people come together to share information, experiences and give each other support.

You might be able to find a local group by searching online. Rethink Mental Illness have support groups in some areas. You can find out what is available in your area if you follow this link: www.rethink.org/about-us/our-support-groups. Or you can call the Rethink Mental Illness Advice Service on 0808 801 0525 for more information.

Recovery College

Recovery colleges are part of the NHS. They offer free courses about mental health to help you manage your symptoms. They can help you to take control of your life and become an expert in your own wellbeing and recovery. You can usually self-refer to a recovery college. But the college may inform your care team.

They offer free courses about mental health to help you manage your symptoms. They can help you to take control of your life and become an expert in your own wellbeing and recovery. You can usually self-refer to a recovery college. But the college may inform your care team.

Unfortunately, recovery colleges are not available in all areas. To see if there is a recovery college in your area you can use a search engine such as Google. Or contact Rethink Mental Illness Advice Service on 0808 801 0525.

You might also find some of the following things helpful.

- Make sure you speak to a doctor if you think that your relationships with others are being affected.

- Think about how you will benefit from making changes to your lifestyle.

- Don’t pay too much attention to the name of the condition. BPD is a common condition and it is not meant to label you or to suggest that your situation won’t change.

- If you’re offered group therapy or support, give it a chance.

It may seem intimidating to start with, but a lot of people find it helpful in the long-run.

It may seem intimidating to start with, but a lot of people find it helpful in the long-run. - If something annoys or upsets you, try to wait a while before responding. Think carefully about what you’re going to say and how you’re going to say it.

- Try to find ways of relaxing. Meditation, breathing techniques, listening to music and exercising may be helpful.

- Look for patterns in the ways you respond to things that upset you. This may help you to work through problems in relationships.

- If you self-harm to deal with distress, think of other ways to deal with this. Try punching a pillow or writing about how you feel.

- Use an online mental health forum. Make sure that you check with a mental health professional how trustworthy the website is for helpful information on BPD.

You can find more information about:

- Recovery by clicking here.

- Self-harm by clicking here.

- Suicidal thoughts – how to cope by clicking here.

Information for carers, friends and relatives

Information for carers, friends and relatives

As a carer, friend or family member of someone living with borderline personality disorder (BPD), you might find that you need support.

How can I get support?

You can do the following.

- Speak to your relative’s care team about a carer’s assessment.

- Ask for a carer’s assessment from your local social services.

- Join a carers service. They are free and available in most areas.

- Join a carers support group for emotional and practical support. Or set up your own.

- Speak to your GP about medication and talking therapies for yourself if your mental health is affecting your day-to-day life.

What is a carer’s assessment?

A carer’s assessment is an assessment of the support that you need so that you can continue in your caring role.

To get a carers assessment you need to contact your local authority.

How do I get support from my peers?

You can get peer support through carer support services or carers groups. You can search for local groups in your area by using a search engine such as Google. Or you can contact the Rethink Mental Illness Advice Service and we will search for you.

How can I support the person I care for?

You can do the following.

- Read information about BPD.

- Ask the person you support to tell you what their symptoms are and if they have any self-management techniques that you could help them with.

- Encourage them to see a GP if you are worried about their mental health.

- Ask to see a copy of their care plan, if they have one. They should have a care plan if they are supported by a care coordinator.

- Help them to manage their finances.

How can learning about BPD help?

Learning about BPD can help you to:

- support the person who has BPD,

- understand why they may act in certain ways, and perhaps take things less personally, and

- become more aware of what situations make them more distressed.

Craig's Story

What is a care plan?

The care plan is a written document that says what care your relative or friend will get and who is responsible for it.

A care plan should always include a crisis plan. A crisis plan will have information about who to contact if they become unwell. You can use this information to support and encourage them to stay well and get help if needed.

Can I be involved in care planning?

As a carer you can be involved in decisions about care planning. But you don’t have a legal right to this.

Your relative or friend needs to give permission for the NHS to share information about them and their care.

You can find out more about:

- Supporting someone with a mental illness by clicking here.

- Getting help in a crisis by clicking here.

- Suicidal thoughts. How to support someone by clicking here.

- Responding to unusual thoughts and behaviours by clicking here.

- Carers assessment by clicking here.

- Confidentiality and information sharing. For carers, friends and family by clicking here.

- Money matters: dealing with someone else’s money or benefits by clicking here.

- Worried about someone’s mental health by clicking here.

- Benefits for carers by clicking here.

- Stress by clicking here.

Further reading

North West Boroughs Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust

This NHS website has information dedicated to different breathing techniques. These techniques can help you when you feel anxious.

Website: www.nwbh.nhs.uk/healthandwellbeing/Pages/Breathing-Techniques-.aspx

Centre for Clinical Interventions

This website is provided by the department of Health in Western Australia. They have some useful information sheets and a workbook for people who are experiencing problems with coping with their feelings. And for people experiencing distress.

And for people experiencing distress.

Website: www.cci.health.wa.gov.au/Resources/For-Clinicians/Distress-Tolerance

You can find out more about:

- Getting help in a crisis by clicking here.

- Suicidal thoughts - How to cope by clicking here.

- Self-harm by clicking here.

- Drugs, alcohol and mental health by clicking here.

- Carers assessment - Under the Care Act 2014 by clicking here.

- Confidentiality and information sharing - For carers, friends and family by clicking here.

- Worried about someone’s mental health by clicking here.

- Stress - How to cope by clicking here.

Useful contacts

BPD World

Provides information and support to people affected by personality disorders. It has an online support forum.

Website: www.bpdworld.org

Samaritans

Can be contacted by telephone, letter, e-mail and mini-com. There's also a face-to-face service, available at their local branches. They are open 24 hours a day, every day of the year.

There's also a face-to-face service, available at their local branches. They are open 24 hours a day, every day of the year.

Telephone: 116 123

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.samaritans.org

ASSISTline

National helpline offering supportive listening service to anyone throughout the UK with thoughts of suicide or thoughts of self-harm. They are open 24/7.

Telephone: 0800 689 5652

Website: www.spbristol.org/

Sane Line

Work with anyone affected by mental illness, including families, friends and carers. They also provide a free text-based support service called Textcare and an online supportive forum community where anyone can share their experiences of mental health.

Telephone: 0300 304 7000

Textcare: www.sane.org.uk/what_we_do/support/textcare

Support Forum: www. sane.org.uk/what_we_do/support/supportforum

sane.org.uk/what_we_do/support/supportforum

Website: www.sane.org.uk

Support Line

They offer confidential emotional support to children, young adults and adults by telephone, email and post. They work with callers to develop healthy, positive coping strategies, an inner feeling of strength and increased self-esteem to encourage healing, recovery and moving forward with life. Their opening hours vary so you need to ring them for details.

Telephone: 01708 765200

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: www.supportline.org.uk

CALM (Campaign Against Living Miserably)

CALM is leading a movement against suicide. They offer accredited confidential, anonymous and free support, information and signposting to people anywhere in the UK through their helpline and webchat service.

Telephone: 0800 58 58 58

Webchat: through the website

Website: www. thecalmzone.net

thecalmzone.net

My Black Dog

Provides peer support webchat with volunteers who have experienced mental illness. Available evenings and weekends. Check the website for opening times.

Website: www.myblackdog.co

Papyrus UK

Work with people under 35 who are having suicidal feelings. And with people who are worried about someone under 35.

Telephone: 0800 068 41 41

Email: [email protected]

Text: 07786 209697

Website: www.papyrus-uk.org

Shout

If you’re experiencing a personal crisis, are unable to cope and need support, text Shout to 85258. Shout can help with urgent issues such as suicidal thoughts, abuse or assault, self-harm, bullying and relationship challenges.

Text: Text Shout to 85258

Website: www.giveusashout.org/

Need more advice?

If you need more advice or information you can contact our Advice and Information Service.

Contact us Contact us

More resources

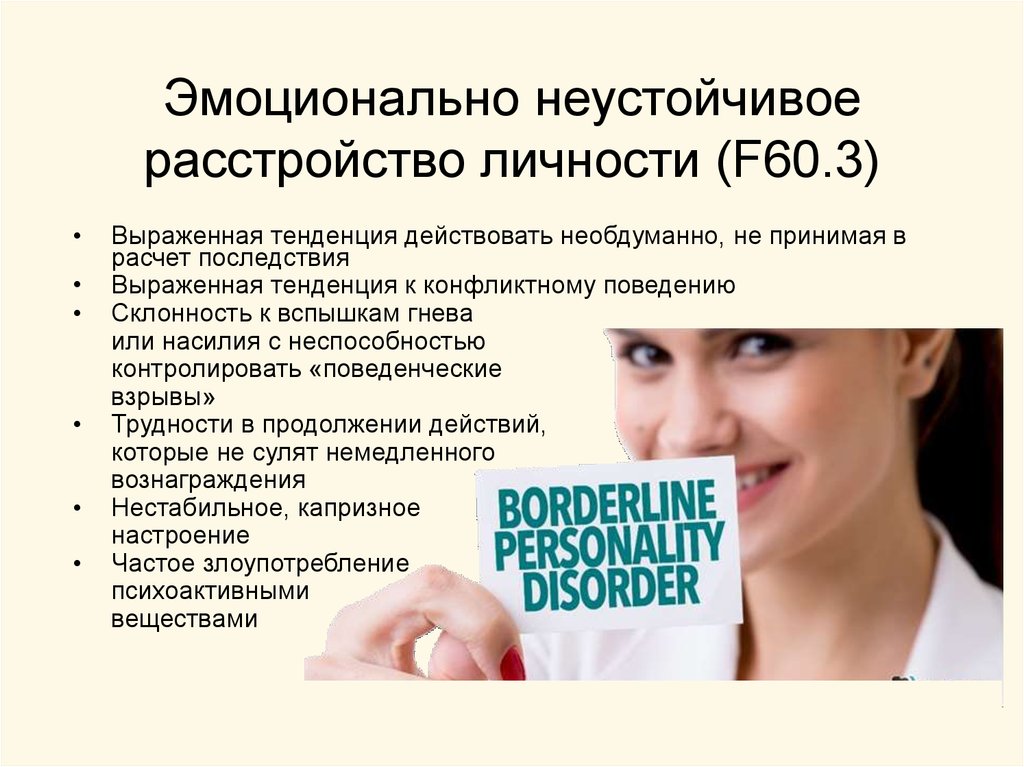

Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder (Types and Symptoms)

Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder

Types and Symptoms

In this article

- What is emotionally unstable personality disorder?

- Diagnosis

- Epidemiology

- Presentation

- Differential diagnosis

- Investigations

- Associated diseases

- Emotionally unstable personality treatment and management

- Complications

- Prognosis

- Prevention

Synonym: borderline personality disorder

What is emotionally unstable personality disorder?

[1]This article refers to the International Classification of Diseases 10th edition (ICD-10) which depicted different types of personality disorder, including emotionally unstable personality disorder. However, the recently published ICD-11 classification does not identify the different types because of overlap between them, and instead focuses on personality traits and severity[2]. See the separate article on Personality Disorders for further details.

Emotionally unstable personality disorder was one of ten personality disorders defined in the ICD-10 classification system. Emotionally unstable personality disorder is characterised by pervasive instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image and mood and impulsive behaviour.

The cause of emotionally unstable personality disorder is unknown but research suggests there is an interaction between adverse life events and genetic factors. Neurobiological research suggests that abnormalities in the frontolimbic networks are associated with many of the symptoms[3].

Emotionally unstable personality disorder causes significantly impaired functioning, including a feeling of emptiness, lack of identity, unstable mood and relationships, intense fear of abandonment and dangerous impulsive behaviour, including severe episodes of self-harm. There is a pattern of sometimes rapid fluctuation from periods of confidence to despair[4].

People with emotionally unstable personality disorder are particularly at risk of suicide[3].

Transient psychotic symptoms, including brief delusions and hallucinations, may also be present. It is also associated with substantial impairment of social, psychological and occupational functioning and quality of life.

Its course is variable and, although many people recover over time, some people may continue to experience social and interpersonal difficulties.

Diagnosis

[1]The important feature of emotionally unstable personality disorder is a pervasive pattern of unstable and intense interpersonal relationships, self-perception and moods. Impulses are poorly controlled. At times they may appear psychotic because of the intensity of their distortions.

The ICD-10 classification identified two subtypes - impulsive type and borderline type.

The criteria were as follows:

The general criteria of personality disorder (F60) must be met.

F60.30 Impulsive type

The predominant characteristics are emotional instability and lack of impulse control. Outbursts of violence or threatening behaviour are common, particularly in response to criticism by others.

F60.31 Borderline type

Several of the characteristics of emotional instability are present; in addition, the patient's own self-image, aims, and internal preferences (including sexual) are often unclear or disturbed. There are usually chronic feelings of emptiness. A liability to become involved in intense and unstable relationships may cause repeated emotional crises and may be associated with excessive efforts to avoid abandonment and a series of suicidal threats or acts of self-harm (although these may occur without obvious precipitants).

Epidemiology

[5, 6]- Epidemiological data need to be interpreted with care, as diagnostic standards vary.

- Personality disorders as a whole are common conditions. There is considerable variation in severity and in the degree of distress and dysfunction caused.

- Some studies estimate that personality disorder affects 4-11% of the UK population and between 60-70% of the prison population[7].

- The prevalence of emotionally unstable personality disorder (which the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) still refers to as 'borderline personality disorder') in the general population is 1%.

- It is less common in the elderly.

- NICE emphasises that 'borderline personality disorder' should not be diagnosed under the age of 18, although characteristic personality traits can be detected at an earlier age.

- Although overall personality disorders are distributed equally between males and females, emotionally unstable personality disorder is more common amongst females. One study reported a prevalence of 30.1% in males and 52.8% in females[8].

Presentation

[1, 4]Patients with the disorder can present with:

- Relationship difficulties.

- Recurrent self-harm.

- Threats of suicide.

- Depression.

- Bouts of anger.

- Impulsivity.

- Social difficulties.

- Transient psychotic symptoms. These were mooted to occur in 'borderline personality disorder' but were not included in the ICD-10 criteria[5, 9].

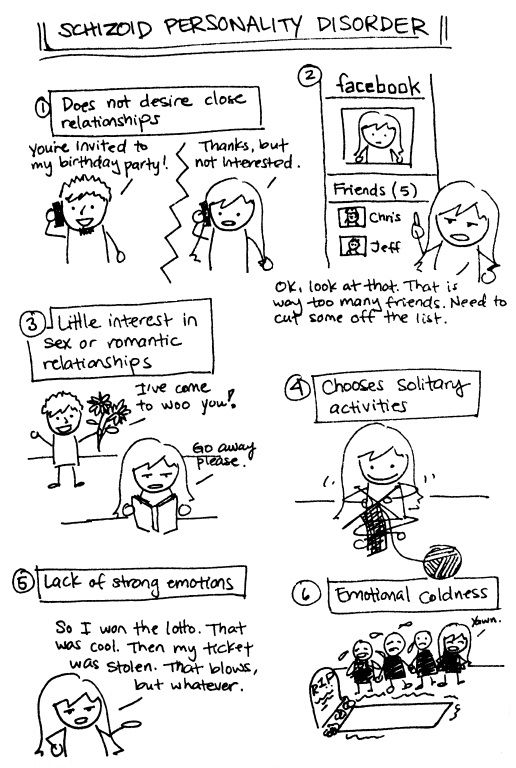

Differential diagnosis

- Alcohol dependency.

- Mental disorders secondary to medical conditions (head injuries, seizure disorders).

- Other personality disorders.

- Anxiety disorders.

- General learning disability.

- Brief psychotic disorder.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder.

- Depression.

- Schizoaffective disorder.

- Schizophrenia.

- Ganser's syndrome.

Investigations

- Toxicology screen because substance abuse is common (as with many personality disorders).

Intoxication can lead patients to present with some features of personality disorders[10].

- Screening for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections may be appropriate because of the poor impulse control and disregard of risk associated with personality disorder[11].

- Psychological testing may support or direct the clinical diagnosis. Those cited by NICE are:

- Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV).

- Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (SCID-II).

- Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV).

- International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE).

- Personality Assessment Schedule (PAS).

- Standardised Assessment of Personality (SAP).

Associated diseases

[12]- Anxiety.

- Alcohol misuse.

- Drug misuse.

- Depression.

- Recurrent self-harm.

- Eating disorders.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder.

- Physical conditions[13]:

- Arteriosclerosis

- Hypertension

- Hepatic disease

- Cardiovascular disease

- Gastrointestinal disease

- Arthritis

- Sexually transmitted infections

Emotionally unstable personality treatment and management

[5, 14]NICE guidance to inform clinical commissioning groups has been published to guide the commissioning of services for people with emotionally unstable personality disorder and dissocial disorder. This draws on prevailing guidance on a large body of resources, encompassing such issues as avoiding the integration of services, wider determinants of health and reducing the delay in the provision of care and support[6].

General considerations

Care should involve collaboration between different agencies and professionals. Teams working with people with emotionally unstable personality disorder should develop a comprehensive multidisciplinary care plan with the service user (and their family or carers, where agreed with the person). The care plan should:

- Identify clearly the roles and responsibilities of all health and social care professionals.

- Identify manageable short-term treatment aims and specify steps that the person and others might take to achieve them.

- Identify long-term goals (including employment), which the person would like to achieve. These should underpin the overall long-term treatment strategy.

- Develop a crisis plan which:

- Identifies potential triggers that could lead to a crisis.

- Specifies self-management strategies likely to be effective.

- Establishes how to access services (including support numbers for out-of-hours teams and crisis teams).

- Be shared with the GP and the service user.

Psychological treatment

Psychotherapy is a helpful mode of treatment in emotionally unstable personality disorder, although no specific type of therapy seems better than another[3]. It is important however NOT to use brief psychological interventions (of less than three months in duration) for emotionally unstable personality disorder or for the individual symptoms of the disorder outside a service that has the characteristics outlined below. Psychological treatment for people with emotionally unstable personality disorder (especially those with multiple comorbidities and severe impairment) should include:

- An explicit and integrated theoretical approach used by both the treatment team and the therapist, which is shared with the service user.

- Structured care in accordance with this guideline.

- Provision for therapist supervision.

- Twice-weekly sessions (although the frequency of psychotherapy sessions should be adapted to the person's needs).

Drug treatment

- A Cochrane review concluded that mood stabilisers and second-generation antipsychotics may be effective for treating a number of core symptoms and associated psychopathology, although the overall severity of emotionally unstable personality disorder is not affected. Drugs should therefore be targeted at specific symptoms[15].

- There is some support for clozapine in the literature, particularly in adolescents with emerging emotionally unstable personality disorder when other treatment options have been exhausted[16].

- Consider drug treatment in the overall treatment of comorbid conditions.

- Consider cautiously short-term use of sedative medication as part of the overall treatment plan for people with emotionally unstable personality disorder in a crisis. Agree the duration of treatment with them; however, it should be no longer than one week.

- Prescribing for this indication is largely off-label and idiosyncratic. Therefore, review the treatment of those who do not have a diagnosed comorbid mental or physical illness and who are currently being prescribed drugs. Aim to reduce and stop unnecessary drug treatment[17].

Management in primary care

- Recognise:

- Repeatedly self-harmed.

- Persistent risk-taking behaviour.

- Marked emotional instability.

- Refer:

- To community mental health services for assessment for emotionally unstable personality disorder.

- If the person is younger than 18 years, refer them to The Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) for assessment.

- Crisis management: consult the patient's crisis plan (a plan devised to identify trigger factors, advise on self-help strategies and identify when the individual should seek professional help):

- Assess problem and risk:

- Maintain a calm and non-threatening attitude.

- Try to understand the crisis from the person's point of view.

- Explore the person's reasons for distress.

- Use empathetic open questioning, including validating statements, to identify the onset and the course of the current problems.

- Seek to stimulate reflection about solutions.

- Avoid minimising the person's stated reasons for the crisis.

- Wait for full clarification of the problems before offering solutions.

- Explore other options before considering admission to a crisis unit, or inpatient admission.

- Offer appropriate follow-up within a timeframe agreed with the person.

- Assess risk to self or to others.

- Ask about previous episodes and effective management strategies used in the past.

- Help to manage their anxiety by enhancing coping skills and helping them to focus on the current problems.

- Encourage them to identify manageable changes that will enable them to deal with the current problems.

- Offer a follow-up appointment at an agreed time.

- Refer in crisis to community mental health services especially when:

- Levels of distress and/or the risk of harm to self or to others are increasing.

- Levels of distress and/or the risk of harm to self or to others have not subsided despite attempts to reduce anxiety and improve coping skills.

- Patients request further help from specialist services.

- Assess problem and risk:

Complications

[13]- Suicide[12]

- Substance abuse

- Accidental injury

- Depression

- Homicide

Prognosis

[3]The course of emotionally unstable personality disorder is variable and, although many people recover or improve over time, many continue to experience social and interpersonal difficulties.

Prevention

[18]There is evidence that novel indicated prevention and early intervention programmes may be useful in reducing the risk of developing emotionally unstable personality disorder. Indicated prevention involves identifying individuals who exhibit early signs of early conduct problems and/or have an increased risk for a disorder but currently do not have a diagnosable disorder. Early intervention programmes involve a system of co-ordinated services that promotes a child's age-appropriate growth and development and supports families during the critical early years. This approach is promising but requires further research.

Fariba K, Gupta V, Kass E; Personality Disorder. StatPearls, June 2021.

Kendall T, Burbeck R, Bateman A; Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: NICE guideline. Br J Psychiatry. 2010 Feb196(2):158-9.

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders; World Health Organization

International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision; World Health Organization, 2019/2021

Leichsenring F, Leibing E, Kruse J, et al; Borderline personality disorder.

Lancet. 2011 Jan 1377(9759):74-84.

Gamlin C, Varney A, Agius M; Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder in Primary Care: A Thematic Review and Novel Toolkit. Psychiatr Danub. 2019 Sep31(Suppl 3):282-289.

Borderline personality disorder: recognition and management; NICE Clinical Guideline (January 2009)

Personality disorders: borderline and antisocial; NICE Quality Standard, June 2015

Working with personality disordered offenders: A practitioners guide, 2011; Ministry of Justice - archived content

Hoye A, Jacobsen BK, Hansen V; Sex differences in mortality of admitted patients with personality disorders in North Norway--a prospective register study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013 Nov 2613:317. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-317.

Adams B, Sanders T; Experiences of psychosis in borderline personality disorder: a qualitative analysis. J Ment Health. 2011 Aug20(4):381-91.

First M et al; Clinical Guide to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Mental Disorders, 2011.

Elkington KS, Teplin LA, Mericle AA, et al; HIV/sexually transmitted infection risk behaviors in delinquent youth with psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008 Aug47(8):901-11. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179962b.

Working with offenders with personality disorders - a practitioners guide; National Offender Management Service and NHS England (September 2015)

El-Gabalawy R, Katz LY, Sareen J; Comorbidity and associated severity of borderline personality disorder and physical health conditions in a nationally representative sample. Psychosom Med. 2010 Sep72(7):641-7. Epub 2010 May 27.

Livesley WJ; A practical approach to the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2000 Mar23(1):211-32.

Lieb K, Vollm B, Rucker G, et al; Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Cochrane systematic review of randomised trials. Br J Psychiatry.

2010 Jan196(1):4-12.

Argent SE, Hill SA; The novel use of clozapine in an adolescent with borderline personality disorder. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014 Aug4(4):149-55. doi: 10.1177/2045125314532488.

Paton C, Crawford MJ, Bhatti SF, et al; The use of psychotropic medication in patients with emotionally unstable personality disorder under the care of UK mental health services. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015 Apr76(4):e512-8. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09228.

Chanen AM, McCutcheon L; Prevention and early intervention for borderline personality disorder: current status and recent evidence. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2013 Jan54:s24-9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119180.

Emotional personality disorder - treatment and rehabilitation at the Allianz Central Medical Health Center

Emotionally unstable (labile) personality disorder is hyperexcitability, impulsivity, low ability to self-control and emotional imbalance. Like other personality disorders, it is more of a character pathology ("severe character") rather than a disease. An experienced psychotherapist can help with the disorder.

Important

"Severe character", the inability to cope with one's emotions is a reason to seek help from a psychotherapist.

In another way it is called aggressive, epileptoid, excitable, explosive personality disorder. Sometimes doctors treat it as two separate disorders—impulsive personality disorder and borderline personality disorder.

A common feature of people with both variants of emotionally unstable personality disorder is that it is difficult for them to restrain themselves, obey norms and rules due to weak self-control and impulsivity. Character traits make it difficult to establish and maintain contacts with others. Treatment by a psychotherapist for such people is an opportunity to accept the peculiarities of their psyche and learn to live in harmony with others.

Symptoms of epileptoid personality disorder

If we talk about the classification of emotionally unstable personality disorder, ICD-10 divides it into two subspecies:

- Impulsive.

- Border.

An emotionally unstable personality disorder of the impulsive type is characterized by severe emotional lability (frequent unreasonable mood changes), a tendency to impulsive acts and aggressive outbursts with an inability to restrain. People with this disorder have a hard time with criticism and censure.

Epileptoids are characterized by jealousy, suspicion, manipulative tendencies, irritability and outbursts of anger.

For an emotionally unstable personality disorder of the borderline type, aggressive behavior towards others is less characteristic, but such people are prone to self-harm, up to suicidal acts. Learn more about borderline disorder.

According to ICD-10, a disorder is characterized by common features of a personality disorder and specific features. The general criteria are as follows:

- begins to appear in childhood and adolescence, persists into adulthood;

- it is difficult to distinguish clear phases of recovery/exacerbation;

- character traits make it difficult to communicate with relatives and strangers, do not allow to take place professionally;

- a person is often self-centered, incapable of empathy (sympathy for other people), constantly striving for pleasure.

Specific symptoms of the impulsive (explosive) type of emotionally unstable personality disorder:

- Impulsivity in thoughts and actions.

- Low ability to self-control.

- Outbursts of anger.

- Tendency to cruel and asocial acts.

- Intolerance to censure and criticism.

To diagnose the impulsive type of emotionally unstable personality disorder, the psychotherapist talks in detail with the client.

Differential diagnosis is carried out with other personality disorders (borderline, hysterical), as well as with epilepsy. For this, a pathopsychological study is used (performed by a clinical psychologist), EEG, Neurotest.

An integrated approach to diagnosis is necessary so that the doctor can prescribe the most effective treatment for this person.

Emotionally unstable personality disorder - treatment

People with emotionally unstable personality disorder are especially in dire need of the help of a psychotherapist. A specialist can teach them to control their emotions and prevent the negative impact of emotional outbursts on others (with impulsive disorder) and on the person himself (with borderline personality disorder).

Labile personality disorder is described as one of the most difficult diagnoses to treat. Establishing contact with a person who suffers from an emotionally unstable personality disorder is not an easy task for a psychotherapist. Inexperienced professionals avoid a strong alliance with such patients so as not to lose their own peace of mind.

But at the same time, it is important to remember that a personality disorder is not a disease, the patient does not have damage to the nervous system. Therefore, with proper treatment, it achieves serious positive results. People with borderline and aggressive personality disorders should be treated by an experienced psychotherapist.

Important

Psychotherapy is the main non-drug treatment for mental disorders. Unlike medicines that eliminate symptoms, it works with the cause - it allows you to achieve a long-term, lasting result.

The main treatment for emotional personality disorder is psychotherapy. Drug treatment is not used in all cases. Medication support may sometimes be needed if the personality disorder is co-occurring with other illnesses, such as depression.

The most effective techniques when working with people who suffer from emotionally labile personality disorder are cognitive behavioral therapy and dialectical behavioral therapy. They help patients become aware of the thoughts and feelings that influence their actions and teach them to control themselves.

Subject to all the recommendations of the doctor and, most importantly, the desire of the patient to interact with the psychotherapist, the therapy gives a lasting positive effect. At the same time, the specialist does not seek to change the patient's personality, but helps to accept oneself and learn to live in harmony with oneself and others.

Treatment of emotionally unstable personality disorder at the Allianz Central Medical Health Center

We have Skype or WhatsApp consultation available.

Emotionally unstable (explosive, excitable, epileptoid) personality disorder is a deep violation of the characterological constitution, the leading symptoms of which are extreme emotional instability combined with a tendency to impulsive actions without considering their consequences. These symptoms begin to appear from childhood, crystallize during puberty, and a detailed clinical picture appears already in early adolescence.

There are two subtypes of this disorder: impulsive and borderline.

The impulsive type has the following features:

- Emotional instability manifests itself in the form of easily occurring outbursts of anger, rage and aggression. The background of the mood is dysphoric (gloominess, irritability, hostile attitude towards others, dissatisfaction with everything and everyone).

- Along with variability, there is a pronounced viscosity of affective reactions. Such people are very vindictive, vindictive, unyielding.

- The impulsivity of actions is manifested in outbursts of verbal and non-verbal aggression spontaneously or in response to the slightest opposition from the outside; disinhibition of drives, sexual excesses.

The border type is characterized by the following differences:

- Emotional instability is a consequence of impressionability, vividness of imagination, high speed and mobility of cognitive processes. It does not carry a dysphoric component, on the contrary, people of this type are deeply involved in events, especially those relating to their sphere of interests. They are very susceptible to any obstacles in the way of realizing their goals. Their emotional reactions are extremely sharpened and hypertrophied.

- Strong variability in the cognitive sphere is manifested in a frequent change in self-esteem and self-identification, interpretation of the surrounding reality.

- People of this type tend to form dependence in relationships.

- Impulsiveness of actions in this type is manifested by frequent and sudden changes of interests, profession, place of residence, social status, etc. A person with borderline personality disorder at first passionately desires something, makes a lot of efforts to achieve the goal, while demonstrating brilliant success in the chosen field, but soon cools down sharply and switches all his attention to a new object.

Although the borderline type carries less destructive manifestations than the impulsive one, nevertheless, due to excessive excitability and lability of the emotional and behavioral spheres, people of this type experience difficulties in forming healthy strong interpersonal relationships; it is difficult for them to work in one area for a long time, which often becomes an obstacle to professional growth. Constant high mental stress leads to asthenia and symptoms of autonomic dysfunction.

The leading place in the treatment of emotionally unstable personality disorder is occupied by psychotherapy. Various forms and methods are used (individual, group, family; gestalt, cognitive behavioral therapy). Due to its characteristics, cognitive-behavioral therapy for borderline personality disorder is characterized by high efficiency in the short and long term.

Cognitive behavioral therapy: features in the treatment of personality disorder

As the result of the merging of two fundamental areas of psychotherapy and simultaneously affecting the thinking and behavior of the patient, cognitive behavioral therapy provides an integrated approach to the correction of personality disorders.

The cognitive component, during which dysfunctional thought patterns are identified and transformed, is carried out in the form of individual sessions. Behavioral, designed to help the patient replace unwanted forms of behavior with new, more constructive ones, can be carried out both in individual and in group or family form. In the latter case, the sessions are aimed not only at the patient, but also at his family members, in order to help them learn how to properly interact with a person suffering from borderline personality disorder.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has the following features:

- use only those methods, the effectiveness of which has been reliably proven experimentally;

- therapy begins with the study of specific, most relevant tasks for the patient - the rule "here and now";

- CBT implies the directive position of the psychotherapist and the active position of the patient, strictly following the instructions of the doctor. Work is carried out not only during sessions, the patient often receives "homework" in the form of specific exercises, keeping a "diary of thoughts", etc.

- , with the consent of the patient, the assistance of family members is actively used in therapy.

Due to its features, cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy has established itself as a therapeutic technique with proven high efficiency, and patients notice the first positive results after just a few sessions.

Long-term effects of therapy on borderline personality disorder

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy does not stop at correcting existing dysfunctional thought and behavior patterns. One of the goals of this method is to teach the patient to cope with new life difficulties, using the techniques and skills that he acquired during the treatment. Thanks to this, rapid rehabilitation, stable and long-term compensation of the condition with simultaneous prevention of "breakdowns" is achieved.

Thus, cognitive-behavioral therapy for borderline personality disorder allows you to solve the following tasks:

- transformation of the patient's dysfunctional personality traits: the formation of new attitudes and ways of thinking to create a positive attitude towards one's own personality and the world around;

- decrease in excitability and elimination of asthenic manifestations;

- patient education: control their behavior and emotions, new constructive skills of social interaction, use the acquired skills and knowledge to adapt to any life circumstances.