Eliza computer therapist

Chatbot ELIZA: Deconstructing Your Friendly Therapist

Chatbot History• August 11, 2017• Written by Alex Debecker

How does that make you feel?

Since my recent review of chatbot ALICE appeared to be well-received, I thought I could continue the series.

This time we are looking into ELIZA. ELIZA is another one of these chatbots pretty much everyone in our community has heard of. Although it did not win any awards, it inspired ALICE and deserves a dedicated article on our site.

Make sure you grab our chatbot history guide.

ELIZA is a stepping stone in our industry. In this article, I will give you a brief overview of its history and show you how ELIZA actually works. We will also see what we can learn from this highly successful chatbot.

Let's dive right in.

Table of contents

- Test ELIZA yourself!

- ELIZA, story and history

- First stabs at conversational

- How does it actually work?

- Lessons learned

Test ELIZA, the computer therapist

As a little treat, we've managed to get a copy to work on our site. We want to thank Michal Wallace and George Dunlop for contributing this open source version.

Use the chat window below to interact with ELIZA:

| Talk to Eliza |

|---|

Type here: |

Important: this wasn't developed by ubisend. It's a very old bot, it's somewhat dumb, and is here for education purposes only! If you want to learn about the chatbots we develop, please read our case study section.

Alright, let's see where this bot came from and how it works.

Chatbot ELIZA, story and history

ELIZA came about in 1964 at MIT. Its creator, Joseph Weizenbaum, built it to "demonstrate that the communication between man and machine was superficial". Evidently, he did not anticipate the success of its programme.

(source)

ELIZA is often described as a therapist chatbot (see this article's title!). The truth is the therapist ELIZA 'skill' was only one of many scripts built by Weizenbaum. It does remain the most well-known, though. This script, DOCTOR, follows simple Rogerian psychotherapy rules to impersonate a real-life therapist.

The truth is the therapist ELIZA 'skill' was only one of many scripts built by Weizenbaum. It does remain the most well-known, though. This script, DOCTOR, follows simple Rogerian psychotherapy rules to impersonate a real-life therapist.

To Weizenbaum's surprise, many people who got to interact with ELIZA attributed human feelings to the machine. Some even got attached to it and refused to believe it was a machine (including, comically, his own assistant).

Finally, ELIZA is regarded as one of the first computer programmes capable of passing the Turing Test -- no easy feat in the 60s!

Playing with ELIZA

UPDATE: You can now do so right from this article! Scroll back up and give it a go.

Though not necessary to carry on reading, you might want to have a bit of fun chatting with ELIZA. You can do so on various websites.

ELIZA's responses are instant. Have a play with this one if you'd like.

Many other websites offer alternative versions of ELIZA. Note that some of those have been altered or improved over time. ELIZA does not have a machine learning engine to support learning on its own but the community has had the time to bring modifications to its open source code.

Note that some of those have been altered or improved over time. ELIZA does not have a machine learning engine to support learning on its own but the community has had the time to bring modifications to its open source code.

Chatbot ELIZA's conversational approach

EIZA acts as a therapist. Not just any therapist, though: a Rogerian psychotherapist.

This is key information in this case because Rogerian psychotherapy employs a unique approach called 'person-centered'. A Rogerian psychotherapist's process is to interact with the patient with complete empathy and lack of judgement.

To do this, the psychotherapist asks person-centric questions to the patient. For instance, if a patient were to say 'I feel depressed', a Rogerian psychotherapist would try to dig further by asking 'Why do you feel down?'.

This type of therapy is a back and forth of statements from the patient and questions from the therapist. The goal is to uncover realisations by digging deeper and deeper.

Ok, this concludes our lesson on psychotherapy. Why does all of this matter?

It matters because it dictates how ELIZA actually interacts with its users. It allows ELIZA to respond to input with accuracy without ever having to really understand what the user says.

How does ELIZA actually work?

The DOCTOR script that powers ELIZA is relatively simple. It assigns a value to each word of a sentence a user inputs and uses the value to reorder the words in the form of a question. The value of the word is determined by its importance within the sentence (which is where the smart stuff happens).

Let's take an example. Taking the sentence 'I want to run away from my parents'.

ELIZA attributes a weighted value to each word of that sentence, like so.

ELIZA attributes low values to pronouns (I), slightly higher values to action verbs (want to), and the highest value to the actual action (run away from my parents). This allows the programme to know exactly how to flip the sentence around to ask a digging question.

How? Simply turn the values into a question, flip the pronoun, and switch the verb to convey meaning.

The answer, then, becomes "What would getting to run away from your parents mean to you ?"

This principle works for every user input. If you tell ELIZA you "love to fly kites", it will answer in the same fashion:

As you can see, we are met with the same kind of answer. The user's input is switched around, albeit in a different manner, and a question is asked to dig deeper into the user's underlying feelings.

What can we learn from ELIZA?

The biggest learning point to get from ELIZA is about complexity. It amazes me how simple ELIZA's script actually is, yet plenty of humans got easily tricked.

Granted, this was a long time ago. In fact, this was 30 years before smartphones even reached our pockets. This, once again, reinforces how much of an innovation ELIZA was.

Yet, this is something you can take from this old chatbot: don't over complicate things. Sure, ELIZA wasn't a smart chatbot by any means. It didn't learn or adapt. But it had one job to do and it did it well.

Sure, ELIZA wasn't a smart chatbot by any means. It didn't learn or adapt. But it had one job to do and it did it well.

The ELIZA Effect - 99% Invisible

Throughout Joseph Weizenbaum’s life, he liked to tell this story about a computer program he’d created back in the 1960s as a professor at MIT. It was a simple chatbot named ELIZA that could interact with users in a typed conversation. As he enlisted people to try it out, Weizenbaum saw similar reactions again and again — people were entranced by the program. They would reveal very intimate details about their lives. It was as if they’d just been waiting for someone (or something) to ask.

ELIZA was a simple computer program. It would look for the keyword in a user’s statement and then reflect it back in the form of a simple phrase or question. When that failed, it would fall back on a set of generic prompts like “please go on” or “tell me more.” Weizenbaum had programmed ELIZA to interact in the style of a psychotherapist, and it was fairly convincing; it gave the illusion of empathy even though it was just simple code. People would have long conversations with the bot that sounded a lot like therapy sessions.

People would have long conversations with the bot that sounded a lot like therapy sessions.

ELIZA was one of the first computer programs that could convincingly simulate human conversation, which Weizenbaum found frankly a bit disturbing. He hadn’t expected people to be so captivated. He worried that users didn’t fully understand they were talking to a bunch of circuits and pondered the broader implications of machines that could effectively mimic a sense of human understanding.

Weizenbaum started raising these big, difficult questions at a time when the field of artificial intelligence was still relatively new and mostly filled with optimism. Many researchers dreamed of creating a world where humans and technology merged in new ways. They wanted to create computers that could talk with us, and respond to our needs and desires. Weizenbaum, meanwhile, would take a different path. He’d begin to speak out against the eroding boundary between humans and machines. And he’d eventually break from the artificial intelligentsia, becoming one the first (and loudest) critics of the very technology he helped to build.

They wanted to create computers that could talk with us, and respond to our needs and desires. Weizenbaum, meanwhile, would take a different path. He’d begin to speak out against the eroding boundary between humans and machines. And he’d eventually break from the artificial intelligentsia, becoming one the first (and loudest) critics of the very technology he helped to build.

Idolizing Machines

People have long been fascinated with mechanical devices that imitate humans. Ancient Egyptians built statues of divinities from wood and stone, and consulted them for advice. Early Buddhist scholars described “precious metal-people” that would recite sacred texts. The Ancient Greeks told stories of Hephaestus, the god of blacksmithing, and his love for crafting robots. Still, it wasn’t until the 1940s and 50s that modern computers starting bringing these fantasies closer to the realm of reality. As computers grew more powerful and widespread, people began to see the potential for intelligent machines.

In 1950, British mathematician Alan Turing wrote the seminal Computing Machinery and Intelligence. Brian Christian, author of The Most Human Human, notes that this paper was published “at the very beginning of computer science … but Turing is already … seeing ahead into the 21st century and imagining” a world in which people might build a machine that could actually “think.” In the paper, Turing proposed his now-famous “Turing test” in which a person has a conversation with both a human and a robot located in different rooms, and has to figure out which is which. If the robot is convincing, it passes the test. Turing predicted this would eventually happen so consistently that we would speak of machines as being intelligent “without expecting to be contradicted.”

The Turing test raised fundamental questions about what it means to have a mind and to be conscious — questions that are not so much about technology as they are about the essence of humanity.

Computer scientists, meanwhile, were pushing forward with the practical business of programming computers to reason, plan and perceive. They created programs that could play checkers, solve word problems, and prove logical theorems. The press at the time described their work as “astonishing.” Herbert Simon, one of the most prominent AI researchers at the time, predicted that by the 1980s machines would be capable of doing any work a person could do. Much as it still does today, this idea made many people anxious. Suddenly, things that set humans apart as logical creatures were being taken over by machines.

Mirroring Language

But despite the big leaps forward, there was one realm, in particular, that proved especially challenging for computers. They struggled to master human language, which in the realm of artificial intelligence is often called “natural language. ” As computer scientist Melanie Mitchell explains, “Natural language processing is probably the hardest problem for AI, and the reason is that language is almost in some sense equivalent to thinking.” Using language brings together all of our knowledge about how the world works, including our understanding of other humans and our intuitive sense of fundamental concepts. As an example, Mitchell presents the statement “a steel ball fell on a glass table and it shattered.” Humans, she notes, immediately understand that “it” refers to the glass table. Machines, by contrast, may or may not have enough contextual knowledge programmed in about materials and physics to come to that same determination. For people, she explains, it’s commonsense.

” As computer scientist Melanie Mitchell explains, “Natural language processing is probably the hardest problem for AI, and the reason is that language is almost in some sense equivalent to thinking.” Using language brings together all of our knowledge about how the world works, including our understanding of other humans and our intuitive sense of fundamental concepts. As an example, Mitchell presents the statement “a steel ball fell on a glass table and it shattered.” Humans, she notes, immediately understand that “it” refers to the glass table. Machines, by contrast, may or may not have enough contextual knowledge programmed in about materials and physics to come to that same determination. For people, she explains, it’s commonsense.

This clumsiness with human language meant that early chatbots, built in the 1950s and 60s, were tightly constrained. They could converse about some very specific topic, like baseball. By limiting the world of possible questions and answers, researchers could build machines that passed as “intelligent. ” But talking with them was like having a conversation with Wikipedia, not a real person.

” But talking with them was like having a conversation with Wikipedia, not a real person.

Shortly after Joseph Weizenbaum arrived at MIT in the 1960s, he started to pursue a workaround to this natural language problem. He realized he could create a chatbot that didn’t really need to know anything about the world. It wouldn’t spit out facts. It would reflect back at the user, like a mirror.

Weizenbaum had long been interested in psychology and recognized that the speech patterns of a therapist might be easy to automate. The results, however, unsettled him. People seemed to have meaningful conversations with something he had never intended to be an actual therapeutic tool. To others, though, this seemed to open a whole world of possibilities.

Before coming to MIT, Weizenbaum had spent time at Stanford, where he became friends with a psychiatrist named Dr. Kenneth Colby. Colby had worked at a large state mental hospital where patients were lucky to see a therapist once a month. He saw potential in ELIZA and started promoting the idea that the program might actually be therapeutically useful. The medical community started to pay attention. They thought that perhaps this program — and others like it — could help expand access to mental healthcare. And it might even have advantages over a human therapist. It would be cheaper and people might actually speak more freely with a robot. Future-minded scientists like Carl Sagan wrote about the idea, in his case imagining a network of psychotherapeutic computer terminals in cities.

He saw potential in ELIZA and started promoting the idea that the program might actually be therapeutically useful. The medical community started to pay attention. They thought that perhaps this program — and others like it — could help expand access to mental healthcare. And it might even have advantages over a human therapist. It would be cheaper and people might actually speak more freely with a robot. Future-minded scientists like Carl Sagan wrote about the idea, in his case imagining a network of psychotherapeutic computer terminals in cities.

And while the idea of therapy terminals on every corner never materialized, people who worked in mental health would continue to experiment with how to use computers in their work. Colby went on to create a chatbot called PARRY, which simulated the conversational style of a person with paranoid schizophrenia. He later developed an interactive program called “Overcoming Depression.”

Weizenbaum, for his part, turned away from his own project’s expanding implications. He objected to the idea that something as subtle, intimate, and human as therapy could be reduced to code. He began to argue that fields requiring human compassion and understanding shouldn’t be automated. And he also worried about the same future that Alan Turing had described — one where chatbots regularly fooled people into thinking they were human. Weizenbaum would eventually write of ELIZA, “What I had not realized is that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people.”

Weizenbaum went from someone working in the heart of the AI community at MIT to someone preaching against it. Where some saw therapeutic potential, he saw a dangerous illusion of compassion that could be bent and twisted by governments and corporations.

Expert Systems

Over the next few decades, so-called “expert systems” started appearing in fields like medicine, law, and finance. Eventually, researchers began trying to create computers that were flexible enough to learn human language on their own.

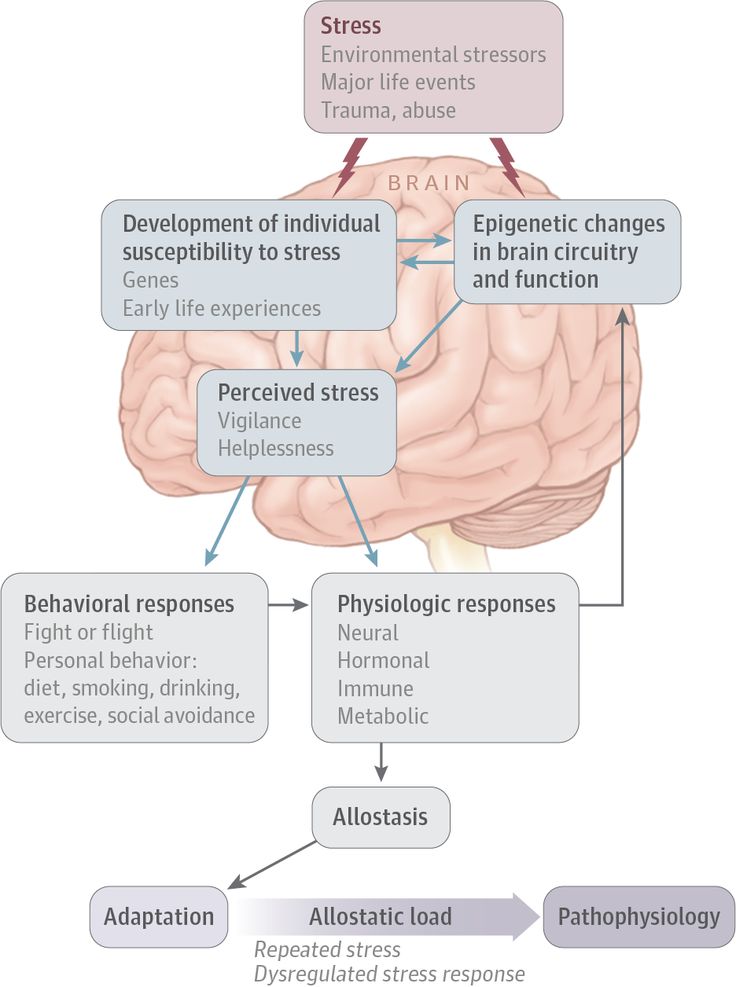

In the 1980s and 90s, there were new breakthroughs in natural language processing. Scientists began relying on statistical methods, taking documents and analyzing linguistic patterns. Then, in the 2000s and 2010s, researchers began using what are called “deep neural networks,” training computers using the huge amounts of data that only became accessible with the rise of the internet. By looking at all kinds of language out on the web, computers could learn far faster than they would simply being programmed one step at a time. These techniques have been applied to chatbots, specifically. Some researchers train their chatbots on recorded conversations. Some put their chatbots online and they learn as they interact with users directly.

Despite these advances, contemporary chatbots — and their talking cousins, like Siri and Alexa — still can’t really “understand” concepts in the way we understand them. But even if conversational AI still lack common sense, they have become a lot more reliable, personable, and convincing. There are recent examples that make it feel as though we are living firmly in the world that Alan Turing predicted — machines fool humans all the time now. In 2018, for instance, Google revealed an AI called Duplex that can make reservations on the phone — they even inserted stutters and “um”s to make it sound more convincing. To some, this was alarming — in particular, the inability of users to tell for certain whether they were talking to a human or a machine.

Casual Therapy

This issue of transparency has become central to the ethical design of these kinds of systems, especially in sensitive realms like therapy. ELIZA may have seeded the idea of a chatbot therapist, but that idea still persists today. Allison Darcy, founder and CEO of Woebot Labs, says that “transparency is the basis of trust,” and that it informs her work at Woebot, where they’ve created a product designed to address a lack of accessible and affordable mental healthcare.

Allison Darcy, founder and CEO of Woebot Labs, says that “transparency is the basis of trust,” and that it informs her work at Woebot, where they’ve created a product designed to address a lack of accessible and affordable mental healthcare.

A few years back, Darcy and her team began thinking about how to build a digital tool that would make mental healthcare radically accessible. They experimented with video games before landing on the idea of Woebot, a chatbot guide who could take users through exercises based on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, which helps people interrupt and reframe negative thought patterns. Woebot is not trying to pass the Turing test. It’s very transparently non-human. It’s represented by a robot avatar and part of its personality is that it’s curious about human feelings.

As Darcy’s team built a prototype and started learning about people’s interactions with Woebot, she says that right away they could tell something interesting was happening. As with ELIZA, people were forming emotional connections with the program, which offers high fives, sends users GIFs, and acts less like a formal therapist and more like a personal cheerleader. Darcy says her team is very conscious of the ethical questions raised by AI and she acknowledges that this kind of tech is like a surgeon’s scalpel. Used wisely, it can help people survive. Misapplied, it can be a weapon.

As with ELIZA, people were forming emotional connections with the program, which offers high fives, sends users GIFs, and acts less like a formal therapist and more like a personal cheerleader. Darcy says her team is very conscious of the ethical questions raised by AI and she acknowledges that this kind of tech is like a surgeon’s scalpel. Used wisely, it can help people survive. Misapplied, it can be a weapon.

There are legitimate concerns around these kinds of technologies, including privacy and safety but also more complicated issues, like whether such developments might reinforce the status quo. If a chatbot is seen as a viable replacement for a human therapist, it might stall efforts to expand access to comprehensive mental healthcare. Researcher Alena Buyx has co-authored a paper about AI used in a variety of mental health contexts. She says these technologies can be promising, but that there are regulatory gaps and a lack of clarity around best practices.

Researcher Alena Buyx has co-authored a paper about AI used in a variety of mental health contexts. She says these technologies can be promising, but that there are regulatory gaps and a lack of clarity around best practices.

Darcy is clear that she doesn’t see Woebot as a replacement for human therapists, and she thinks the potential for good outweighs the risks. She thought about this a lot when Woebot first launched. They’d been working in relative obscurity and then suddenly their numbers began to climb. Quickly, within the first five days, they had 50,000 users. Woebot was exchanging millions of messages with people each week. As Darcy recalls: “I remember going home after our first day and sitting down at my kitchen table and having the realization that Woebot on his first day of launch had had more conversations with people than a therapist could have in a lifetime.”

Joseph Weizenbaum eventually retired from MIT, but he continued speaking out against the dangers of AI until he died in 2008 at the age of 85. And while he was an important humanist thinker, some people felt like he went too far.

And while he was an important humanist thinker, some people felt like he went too far.

Pamela McCorduck, author of Machines Who Think, knew Weizenbaum over several decades. She says he burned a lot of bridges in the AI community and became almost a caricature of himself towards the end, endlessly railing against the rise of machines.

He also may have missed something that Darcy has thought about a lot with Woebot: the idea that humans engage in a kind of play when we interact with chatbots. We’re not necessarily being fooled, we’re just fascinated to see ourselves reflected back in these intelligent machines.

Who is a therapist and what does he treat - treatment articles

The therapist is a multidisciplinary physician. It diagnoses, treats and prevents a wide range of diseases. The specialist accepts patients from the age of 18 and, if necessary, can refer them to narrow profile doctors (gastroenterologists, endocrinologists, pulmonologists, neurologists, surgeons, etc. ). Usually it is the general practitioner who directs for comprehensive examinations, including laboratory tests and various diagnostic procedures. We will understand all aspects of the work of specialists.

). Usually it is the general practitioner who directs for comprehensive examinations, including laboratory tests and various diagnostic procedures. We will understand all aspects of the work of specialists.

Therapist

Read more

What does a therapist treat?

Usually, patients who do not know which specialist of a narrow profile to consult with their complaints turn to a therapist. The wide profile of the doctor makes it possible to make a preliminary diagnosis and referral to a specialized specialist. Therapists themselves provide treatment for a large number of diseases.

Among them:

- SARS;

- influenza;

- coronavirus infection;

- anemia;

- rotavirus.

Therapists also treat other diseases.

The main responsibilities of a general practitioner include:

- History taking. The specialist studies the patient's medical history, gets acquainted with complaints.

- Inspection. The specialist necessarily conducts a visual examination, probing the internal organs, listening to the lungs, measuring body temperature, determining blood pressure, pulse, etc.

- Issuance of referrals for appointments with narrow specialists and examinations.

- Entering all information received into the medical record.

- Carrying out various examinations (general medical, professional, etc.).

- Issuance of referrals for hospitalization.

When should I see a therapist?

Since the therapist is engaged in the prevention, treatment and diagnosis of a wide range of diseases, he is treated with complaints such as:

- shortness of breath;

- cough;

- coryza;

- nasal congestion;

- elevated body temperature;

- high or low blood pressure;

- stool disorders;

- swelling of the extremities;

- nausea and vomiting;

- dizziness;

- weakness and drowsiness;

- change in body weight without changing the mode of physical activity and nutrition.

Contact doctors and other specialists. If the patient does not know which specialist will help him, you need to sign up for a consultation with one who has the widest possible profile of work.

Consultation with a therapist should not be neglected when:

- Pregnancy planning.

- Upcoming sports activities.

- Changing the diet (including for the purpose of changing body weight).

The therapist can help in recovery after a serious illness, rehabilitation after surgery. An examination by a specialist is relevant before vaccination, therapeutic fasting, visiting various procedures (including physiotherapy), before traveling to an area with a different climate, before spa treatment.

At least once a year, for preventive purposes, it is necessary to visit a therapist for all people over 40 years old. Consultation is obligatory even in the absence of complaints.

The reception will be especially relevant for people who are at risk for the development of various chronic diseases and their complications.

These include individuals who:

- are overweight or obese;

- lead a sedentary lifestyle;

- are subject to emotional overstrain and stress, suffer from depression;

- have bad habits;

- constantly come into contact with hazardous chemicals and their compounds;

- live in regions with adverse climatic and environmental conditions;

- suffer from feeling constantly tired;

- notice shortness of breath even with little physical exertion;

- are professionally involved in sports;

- have certain chronic diseases;

- have recently been treated for severe pathologies (including cancer).

The therapist can constantly monitor the patient's condition. This will eliminate the risks of developing chronic diseases, carry out their prevention or prevent the likelihood of developing serious complications.

How is the examination?

First, the specialist listens to the patient's complaints. He specifies when the symptoms appeared and how intense they are. After that, the specialist clarifies whether the patient has chronic diseases, a aggravated family history, what lifestyle the person leads, how he eats, how often he spends time outdoors, whether he observes the regime of work and rest, whether he has children, etc. This will allow form a complete clinical picture.

He specifies when the symptoms appeared and how intense they are. After that, the specialist clarifies whether the patient has chronic diseases, a aggravated family history, what lifestyle the person leads, how he eats, how often he spends time outdoors, whether he observes the regime of work and rest, whether he has children, etc. This will allow form a complete clinical picture.

After that, the specialist:

- determines the height and weight of the patient;

- measures body temperature;

- detects pulse and blood pressure;

- listens to the heart and lungs;

- performs percussion (tapping) and palpation (palpation) of internal organs.

Often the therapist can immediately make a preliminary diagnosis. From the doctor, the patient can receive initial recommendations and prescribing drugs that will help eliminate the symptoms of the disease.

Then the therapist issues referrals to narrow specialists (if necessary) and for diagnostics.

Typically, the therapist recommends:

- blood, urine and stool tests;

- radiography of internal organs;

- computed and magnetic resonance imaging;

- ultrasound;

- ECG.

If necessary, the doctor recommends other examinations. They allow you to make an accurate diagnosis and carry out the necessary treatment (including with the involvement of narrow specialists).

We hope that you understand what the doctor treats and when to contact him.

Still have questions?

You can get detailed information by phone:

+7 (495) 775-73-60

prices, make an appointment for a paid appointment at the "SM-Clinic"

Adult physicians Children's doctors Prices Types of CT

Book online Request a call

Computed tomography is a modern diagnostic method based on X-ray layer-by-layer scanning. This method allows you to take pictures of various organs and systems of the body in a cross section. The key to the effectiveness and accuracy of the results of computed tomography are high-quality modern equipment and the qualifications of doctors, in the "SM-Clinic" there is both.

The key to the effectiveness and accuracy of the results of computed tomography are high-quality modern equipment and the qualifications of doctors, in the "SM-Clinic" there is both.

The CT scan doctor acts as an expert diagnostician and consultant who helps your doctor confirm or refute a suspected diagnosis. In addition, a CT diagnostician conducts follow-up monitoring of the results of therapy.

Abdominal CT Abdominal CT with contrast CT scan of the temporomandibular joint CT scan of the temporal bones CT scan of the eye orbits CT scan of the ankle brain CT CT scan of the brain with contrast CT scan of the larynx CT scan of the chest chest CT CT chest with contrast CT chest with contrast CT for overweight patients CT scan of the retroperitoneum CT of the retroperitoneum with contrast CT of teeth CT cavernosography CT scan of the knee CT coccyx CT of the bones of the skeleton CT scan of the lungs CT lymph nodes with contrast

CT scan of neck lymph nodes Elbow CT CT scan of the wrist Lung CT with contrast CT scan of the pelvis with contrast CT scan of the uterus CT scan of the urinary tract soft tissue CT CT scan of the adrenal glands CT scan of the adrenal glands with contrast CT scan of the pelvic organs CT scan of the sinuses Liver CT Liver CT with contrast Shoulder CT CT scan of the pancreas with contrast CT scan of the spine kidney CT CT scan of the kidneys with contrast CT scan of the lumbosacral region CT with contrast CT scan of the spleen CT scan of the spleen with contrast

CT of the heart CT of vessels CT foot CT of the joints CT scan of the hip joint jaw CT Neck CT Neck CT with contrast CT scan of the neck, chest, spine CT scan of the thyroid gland CT densitometry of the spine CT enterography (CT scan of the small intestine) MSCT angiography MSCT of the aorta MSCT of brachiocephalic arteries MSCT of the abdominal cavity MSCT of the abdominal cavity with contrast MSCT of the chest MSCT of the heart MSCT of cerebral vessels Multislice computed tomography (MSCT) PET-CT

every day about your health cares

29

KT diagnosts

among them:

2

candidate

Medical Sciences

8

doctors

of the highest category

Why SM-clinic?

1

Treatment in accordance with global clinical guidelines

2

Comprehensive assessment of the disease and treatment prognosis

3

Modern diagnostic equipment and own laboratory

4

High level of service and balanced pricing policy

Siemens SOMATOM Perspective tomograph (128 slices)

Siemens SOMATOM Perspective tomograph (64 slices)

SOMATOM Scope Power computed tomograph (16 slices)

| CT scan of the head (brain structure) | 4 160 rub |

| MSCT of coronary calcium without contrast (assessment of risk factors for myocardial infarction) | 4 800 rub |

| CT of kidneys, adrenals | 4 680 rub |

| CT scan of the pelvic organs | 4 920 rub |

| CT scan of the urinary system (kidneys, ureters, bladder) | 7 400 rub |

| MSCT angiography of the aorta (ct-panortography) without the cost of a contrast agent | 14 250 rub |

| MSCT angiography of the pulmonary artery and its branches (ct panortography) without the cost of a contrast agent | 10 350 rub |

| MSCT angiography of the heart (CT shuntography) without the cost of a contrast agent | 14 250 rub |

| MSCT angiography of the heart (CT-coronary angiography) without the cost of a contrast agent | 14 250 rub |

| MSCT angiography of the arteries of the upper extremities or lower extremities without the cost of a contrast agent | 10 350 rub |

| MSCT of the vessels of the head without the cost of a contrast agent | 11 700 rub |

| MSCT of neck vessels (brachiocephalic) without the cost of a contrast agent | 10 350 rub |

| MSCT of the vessels of the head and neck without the cost of a contrast agent | 14 250 rub |

| MSCT of the heart without the cost of a contrast agent | 10 350 RUB |

| CT scan of the abdominal cavity and retroperitoneal space | 6 600 rub |

| MSCT of the left atrium and pulmonary veins without the cost of a contrast agent | 9 100 rub |

| MSCT of the thoracic/abdominal aorta without the cost of a contrast agent | 10 350 rub |

| MSCT of renal vessels without the cost of a contrast agent | 7 800 rub |

| Computed tomography of the small intestine with double contrast / CT enterography (excluding cost of contrast agent) | 7 950 rub |

| CT scan of the liver, pancreas, spleen | 4 720 rub |

| CT of the chest (CT of the lungs) | 5 040 rub |

| CT scan of the temporomandibular joint | 3 920 rub |

| CT scan of the cervical spine | 4 800 rub |

| CT scan of the temporomandibular joint with functional tests | 5 040 rub |

| CT of each jaw | 5 040 rub |

| CT Orbit | 3 920 rub |

| CT scan of the paranasal sinuses | 4 400 rub |

| CT scan of the temporal bone | 5 040 rub |

| CT pharynx, larynx | 4 560 rub |

| CT scan of the pharynx, larynx with functional tests | 5 600 rub |

| CT scan of the thyroid gland | 3 920 rub |

| CT neck | 4 560 rub |

| CT clavicle, scapula, sternum | 3 680 rub |

| CT scan of the thoracic spine | 4 800 rub |

| CT sacroiliac joints (1 joint) | 2 760 rub |

| CT scan of the lumbosacral spine | 4 800 rub |

| CT coccyx | 4 160 rub |

| CT densitometry of the spine | 2 880 rub |

| CT scan of the pelvic bones | 4 300 rub |

| CT of tubular bones (femur, tibia and fibula, humerus, radius, ulna) (1 bone) | 3 200 rub |

| CT shoulder joint (1 joint) | 3 920 rub |

| CT of the wrist joint (1 joint) | 3 760 rub |

| CT scan of the knee joint (1 joint) | 3 920 rub |

| CT scan of the ankle joint (1 joint) | 3 760 rub |

| CT hand / foot (1 hand / foot) | 4 240 rub |

| CT of the hip joint (1 joint) | 4 280 rub |

| CT scan of the elbow joint | 4 000 rub |

| Examination (consultation) of a radiologist / CT doctor / MRI doctor, leading specialist | 2 700 rub |