Dsm iv axes of diagnosis

DSM V: No More Multiaxial System

DSM V: No More Multiaxial System | Therapist Development Center;

Search form

Search this site

Exam Prep Blog

- Home

- Blog

- DSM-5: No More Multiaxial System

The DSM-5 was published in 2013. Many social workers went to school learning the DSM-IV-TR and because of this, we still receive coaching questions about the differences between the DSM-IV-TR and the DSM-5. We know regardless of which DSM you went to school with, picking up the DSM-5 can feel daunting. The thought of learning and applying all of the DSM-5 information to LCSW exam questions can be overwhelming. But fear not: TDC’s got you covered!

How am I supposed to memorize the DSM-5?

The good news is, you aren’t! The ASWB does not expect you to have the DSM-5 memorized. One of my favorite things about Therapist Development Center’s LCSW and LMSW exam prep programs (that helped me pass both my LMSW and LCSW exams) is that they only give you what you need. While TDC gives you everything you need to pass the exam, they also give you nothing you don’t need.

A lot of programs out there give you WAY more content than you need when the actual exam is primarily made up of reasoning based scenarios. Because of this, exam prep can feel incredibly overwhelming. So rather than having you memorize tedious lists of diagnostic criteria for every diagnosis (which is NOT how the ASWB tests you), we give you the differentials for the most commonly tested diagnoses. We also include an entire LCSW practice exam dedicated to LCSW practice questions exclusively on DSM-5 diagnoses. We do this for the LMSW as well!

Because of this, exam prep can feel incredibly overwhelming. So rather than having you memorize tedious lists of diagnostic criteria for every diagnosis (which is NOT how the ASWB tests you), we give you the differentials for the most commonly tested diagnoses. We also include an entire LCSW practice exam dedicated to LCSW practice questions exclusively on DSM-5 diagnoses. We do this for the LMSW as well!

What was the multiaxial system?

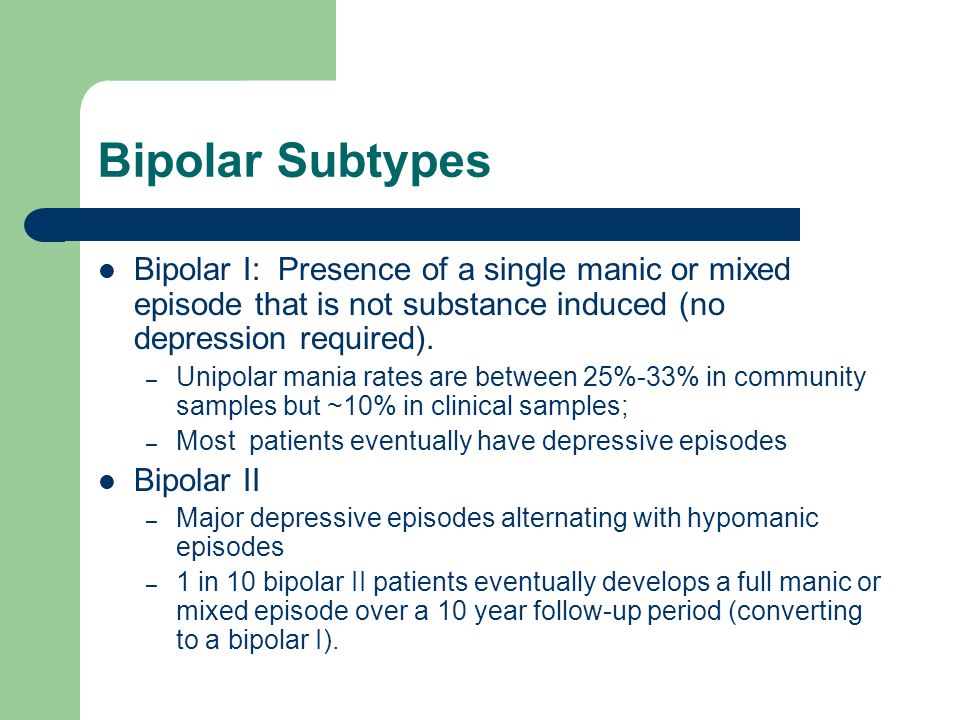

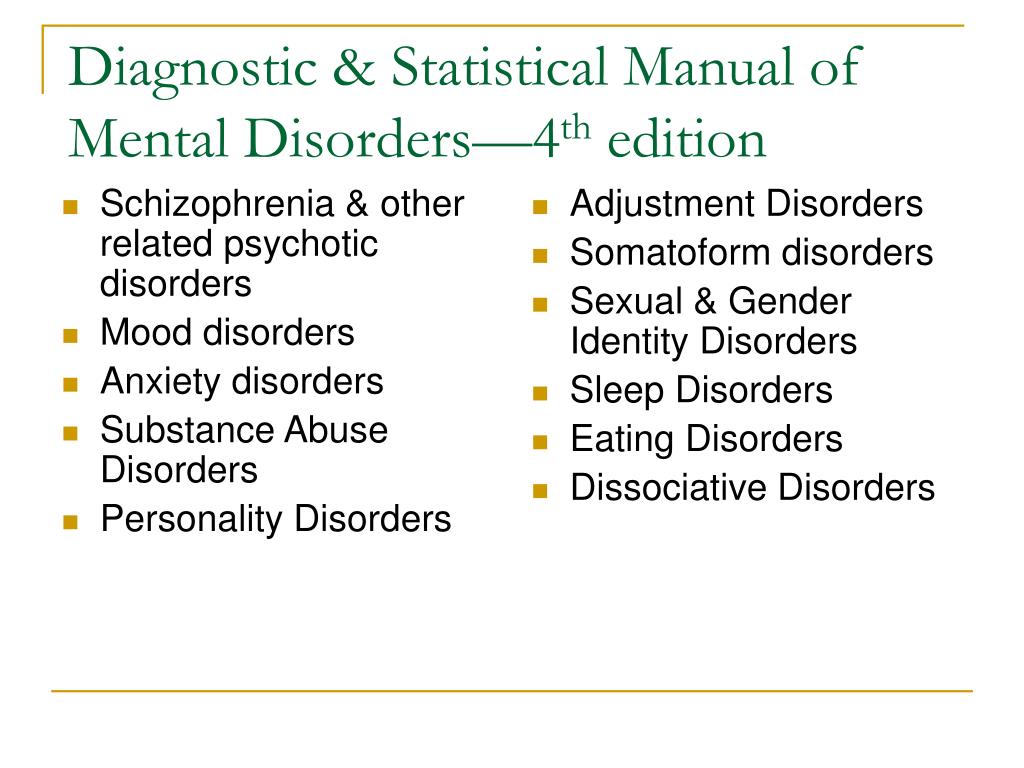

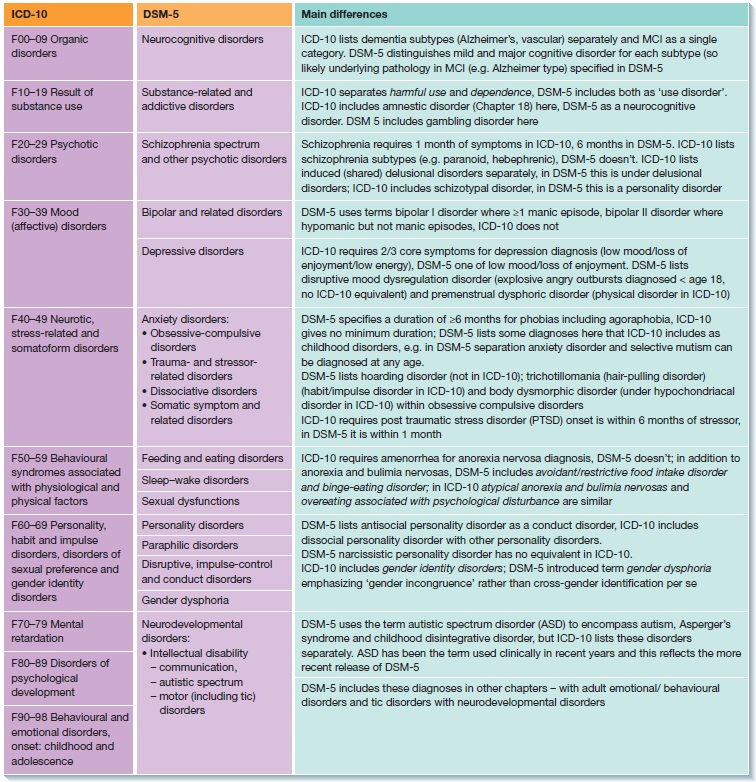

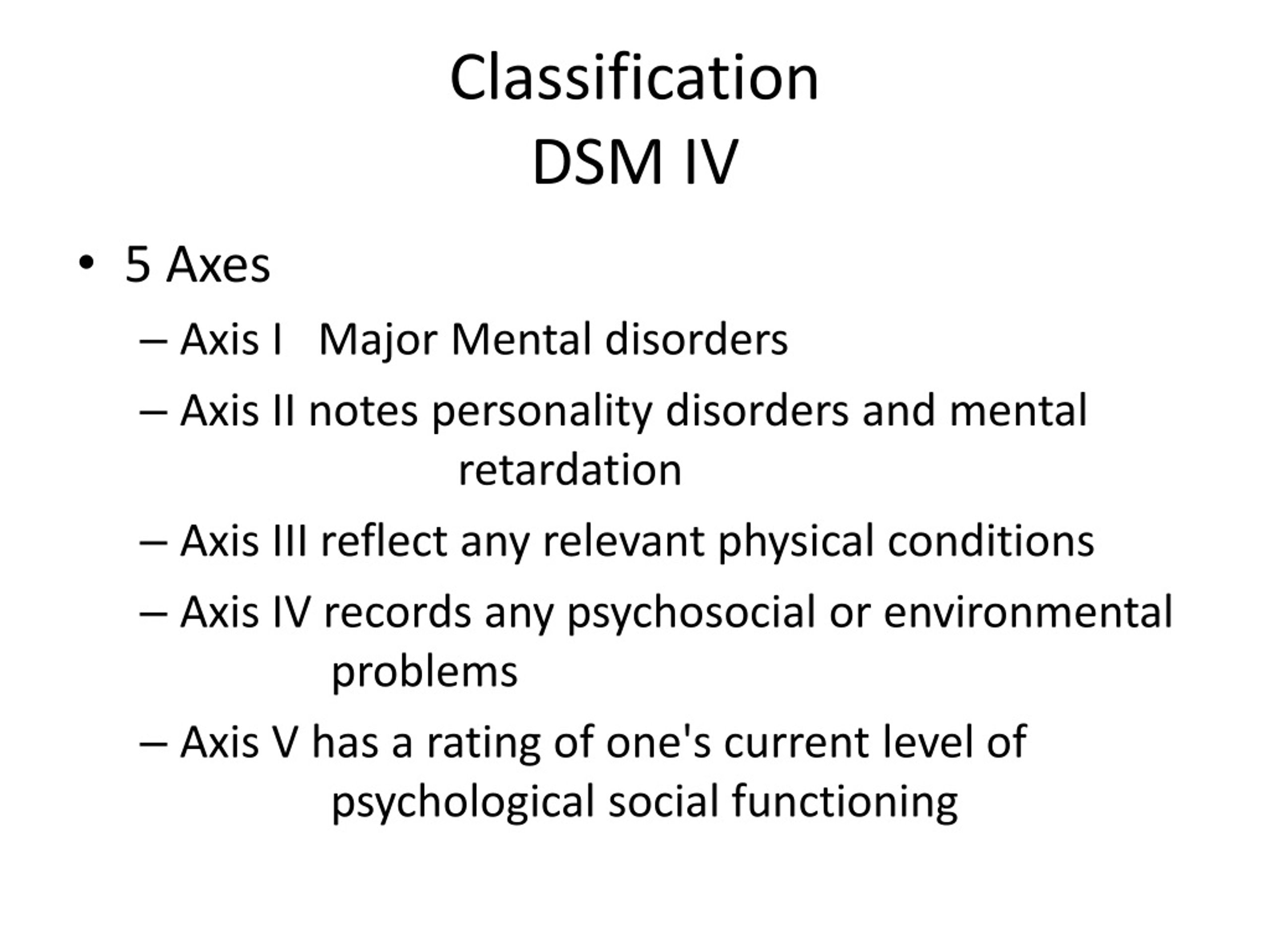

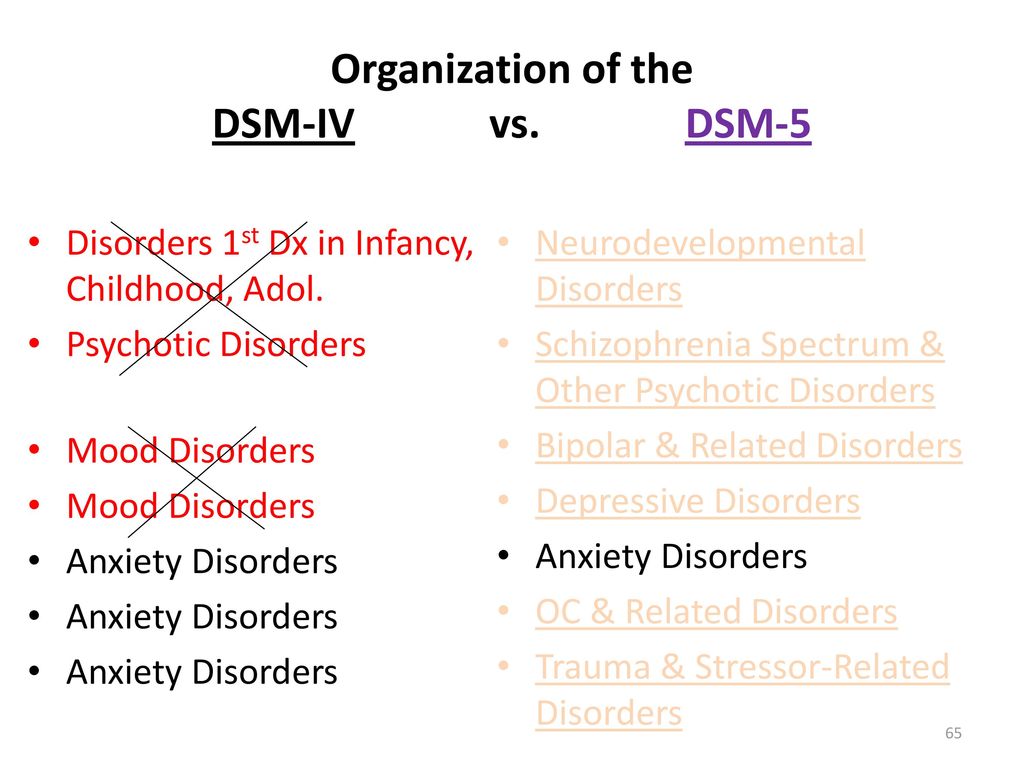

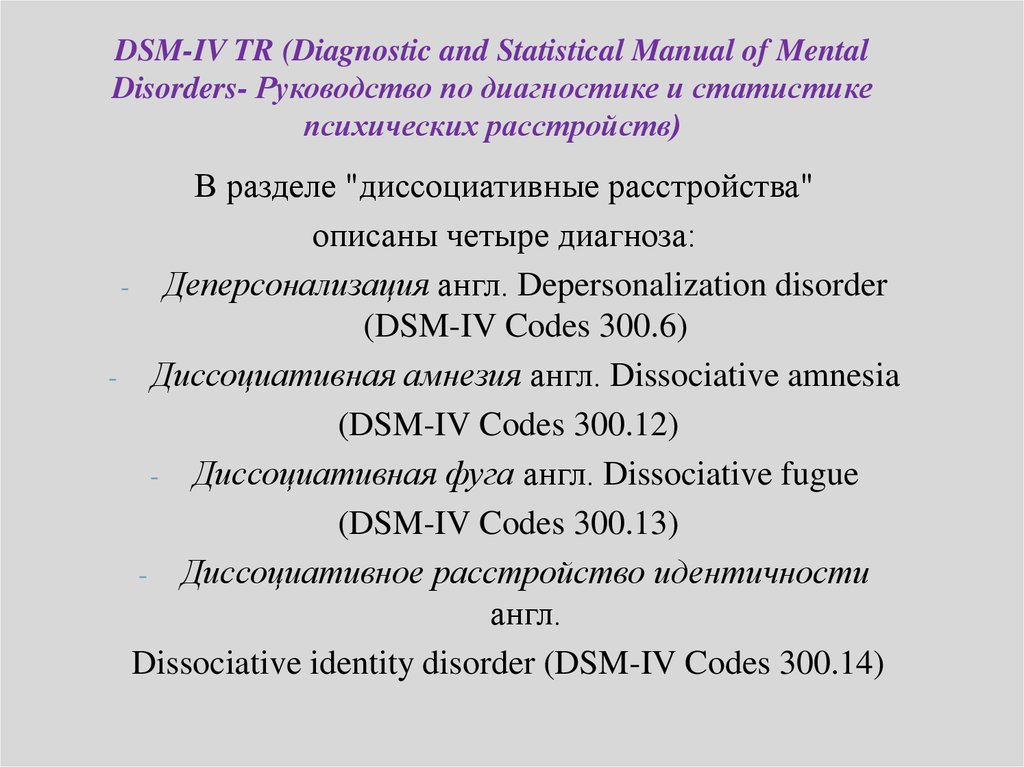

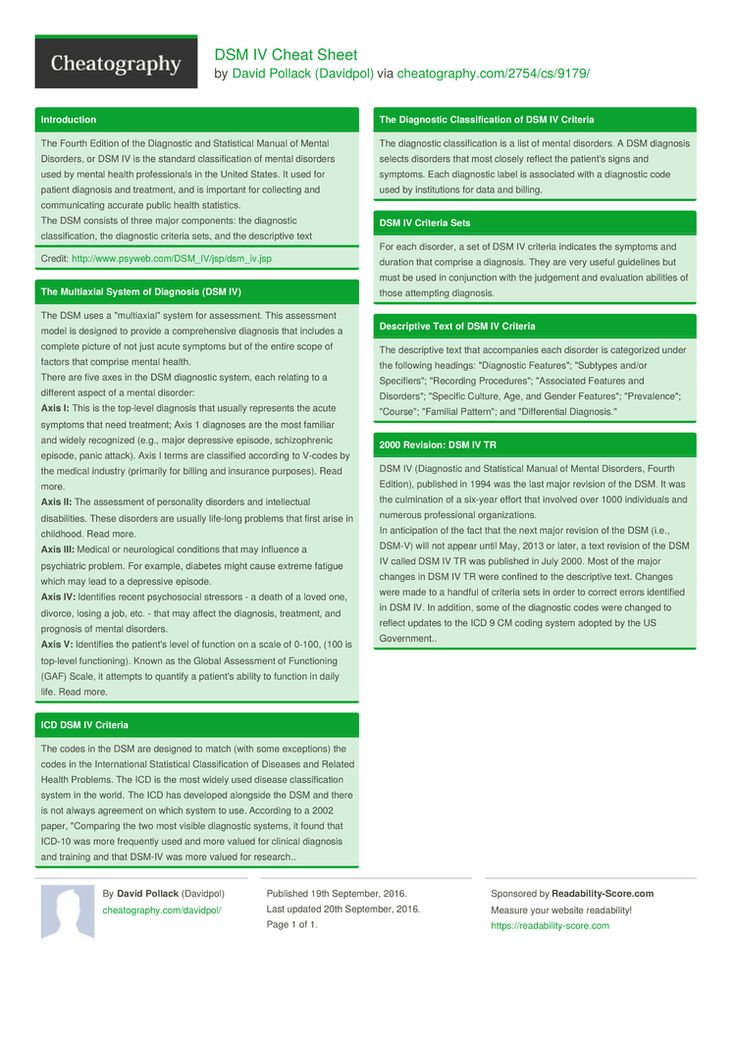

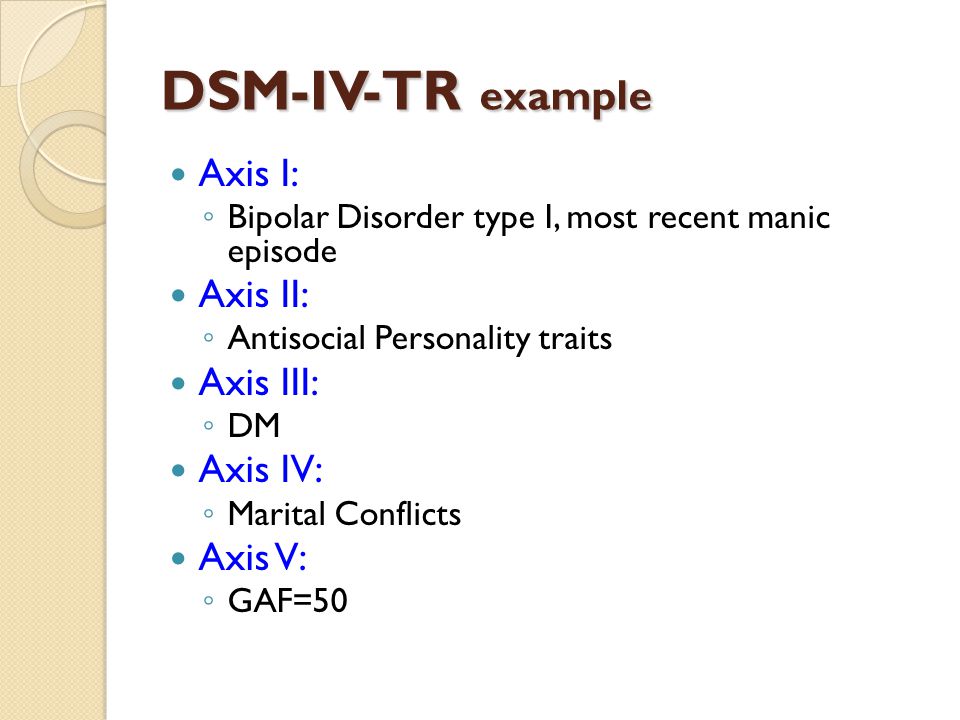

One of the biggest changes between the DSM-IV-TR and the DSM-5 is the removal of the multiaxial system. Prior to the DSM-5, the DSM-IV-TR utilized a multiaxial system of diagnosis. The DSM-III published in 1980 introduced this system, existing to ensure that psychological, biological, environmental, and psychosocial factors were all considered when making a mental health diagnosis. This system utilized diagnoses across five DSM axes to look at the different impacts and elements of disorders. The five axes included: 1. The primary diagnosis, 2. Personality disorders and/or mental retardation, 3. Medical and/or neurological problems impacting the individual’s psychological concerns, 4. The nine categories of environmental and psychosocial stressors impacting the client’s psychological functioning, (such as job loss, romantic separations, or deaths), and 5. A 0-100 rating called the Global Assessment of Functioning (or “GAF”), quantifying the person’s overall level of functioning.

Personality disorders and/or mental retardation, 3. Medical and/or neurological problems impacting the individual’s psychological concerns, 4. The nine categories of environmental and psychosocial stressors impacting the client’s psychological functioning, (such as job loss, romantic separations, or deaths), and 5. A 0-100 rating called the Global Assessment of Functioning (or “GAF”), quantifying the person’s overall level of functioning.

Why was the multiaxial system removed?

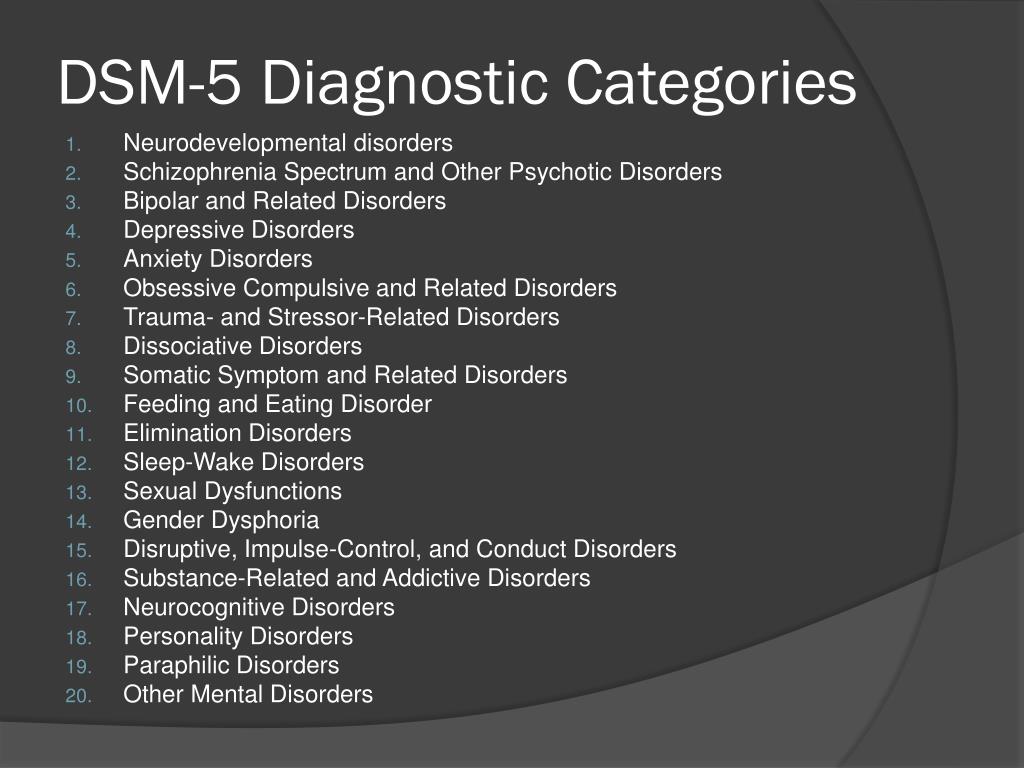

The authors of the DSM-5 streamlined and simplified the diagnostic process by developing a single axis system for assessment and diagnosis of mental disorders. Information from the first four DSM axes are still taken into consideration, but are not separated as they were in previous editions of the DSM. Namely, the DSM-5 has combined axes 1-3 into a single axis that accounts for mental and other medical diagnoses. There are no longer distinct categories for mental health diagnoses, medical diagnoses, and personality disorders.

Prior to the combined axes, experts argued there were no fundamental differences between Axis 1 and Axis 2 diagnoses. Because of this, they believed separating them could lead to confusion and lack of adequate treatment. Contributing stressors that were previously accounted for on the fourth DSM axis are now taken into account through a broadened set of V and Z codes that clinicians can use to indicate additional areas of concern that could be impacting diagnosis and treatment, or that could require further clinical attention (Kress et al., 2014). The fifth DSM axis had long been criticized for lack of reliability and consistency amongst clinicians. It was because of that lack of reliability as well as poor clinical utility that the APA chose to remove this measure from the DSM-5. Moving forward the APA recommends clinicians find alternate ways to document an individual’s distress and impaired functioning (APA, 2013).

How will this impact client work?

The long term impact of these changes is yet to be seen, but will surely reveal itself over time. What are the possible impacts these changes may have? Well, it has been noted that removing the distinction of personality disorders from their own axis may help remove some of the stigma previously associated with these diagnoses (Kress et al., 2014). Experts cite both benefits and drawbacks to combining medical and mental health diagnoses. Possible benefits include decreased stigmatization of mental health disorders, because a single axis system points towards a shared biological basis for both mental health and medical conditions. The previous distinction between mental health and medical disorders led to unequal health care coverage for mental health treatment. Removing this division could prove helpful in equal coverage being provided for mental health conditions.

What are the possible impacts these changes may have? Well, it has been noted that removing the distinction of personality disorders from their own axis may help remove some of the stigma previously associated with these diagnoses (Kress et al., 2014). Experts cite both benefits and drawbacks to combining medical and mental health diagnoses. Possible benefits include decreased stigmatization of mental health disorders, because a single axis system points towards a shared biological basis for both mental health and medical conditions. The previous distinction between mental health and medical disorders led to unequal health care coverage for mental health treatment. Removing this division could prove helpful in equal coverage being provided for mental health conditions.

In terms of drawbacks, having a view of mental health disorders being rooted in biology could suggest those with mental health disorders are flawed biologically (Ben-Zeev, Young, & Corrigan, 2010). Some argue this view could result in a lessening of the consideration of environmental factors on mental health conditions. Further, some say it could lead to an increased use of psychopharmacology to treat mental health disorders (Frances, 2013).

Further, some say it could lead to an increased use of psychopharmacology to treat mental health disorders (Frances, 2013).

Note for test-takers: Will the multiaxial system show up on my exam?

It will not! Neither our LCSW practice exam questions nor the test itself will include anything from the DSM-IV-TR, so because of this, you won’t see the multiaxial system show up. The exam only reflects material from the DSM-5.

Are you ready for the DSM-5?

Whether you went to school learning the DSM-IV, the DSM-IV-TR, or the DSM-5, TDC thoroughly prepares you so you’re ready for both the content and structure of the DSM questions on your ASWB exams. With over 700 LCSW practice questions in the clinical program and 600 LMSW practice questions in the master’s level program, you will learn everything you need to know to PASS your exam with confidence. If you’re ever struggling to understand a question or rationale, you can email your TDC coach who will get back to you with a personalized response to ensure you are ready to PASS. We’ve helped thousands of social workers pass their ASWB licensure exams with a 95% pass rate. Are you next?

We’ve helped thousands of social workers pass their ASWB licensure exams with a 95% pass rate. Are you next?

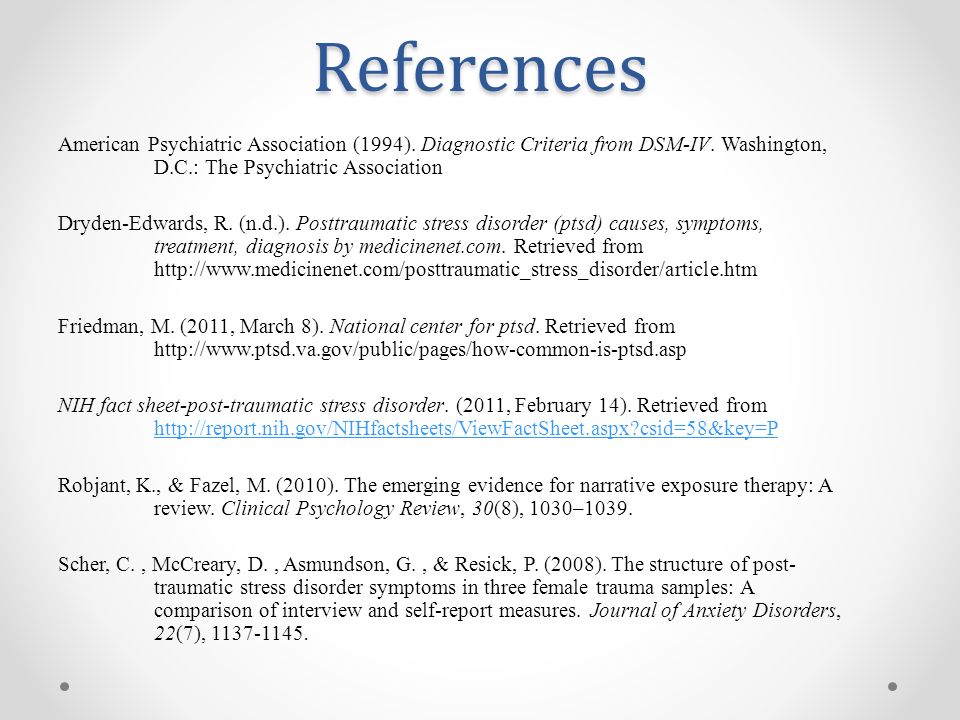

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author.

Ben-Zeev, D., Young, M. A., & Corrigan, P. W. (2010). DSM-V and the stigma of mental illness. Journal of Mental Health, 19, 318–327. doi:10.3109/09638237.2010.492484

Frances, A. (2013). Essentials of psychiatric diagnosis: Responding to the challenge of DSM-5. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Kress, V. C., Barrio Minton, C. A., Adamson, N. A., Paylo, M. J., & Pope, V. (2014). The removal of the multiaxial system in the DSM‐5: Implications and practice suggestions for counselors. The Professional Counselor, 4, 191‐201. doi: :10.15241/vek.4.3.191

Social Work Exam

Prep Programs

Leave a Reply

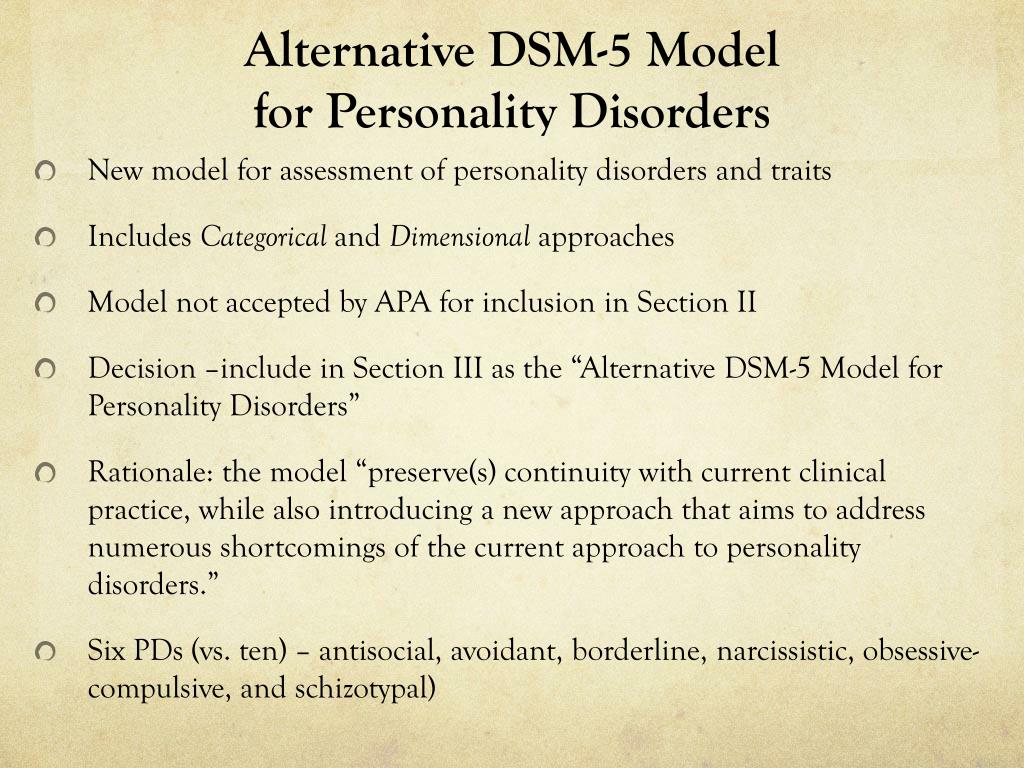

DSM-5 Changes: Personality Disorders (Axis II)

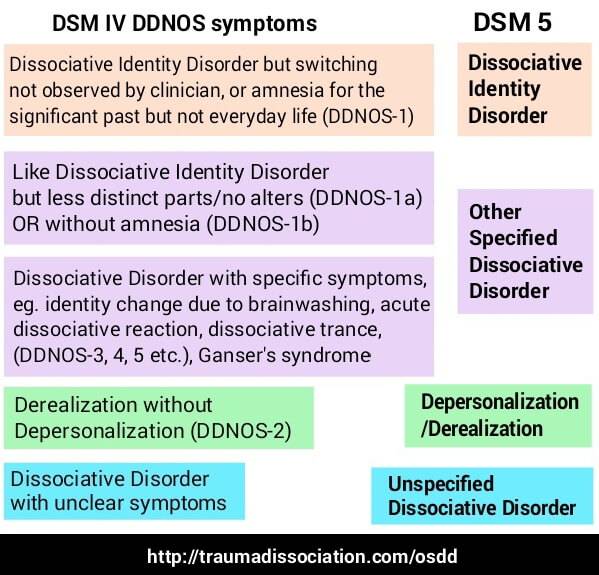

The new Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) has some changes related to personality disorders, which were coded on Axis II under the DSM-IV. This article outlines some of the major changes to these conditions.

This article outlines some of the major changes to these conditions.

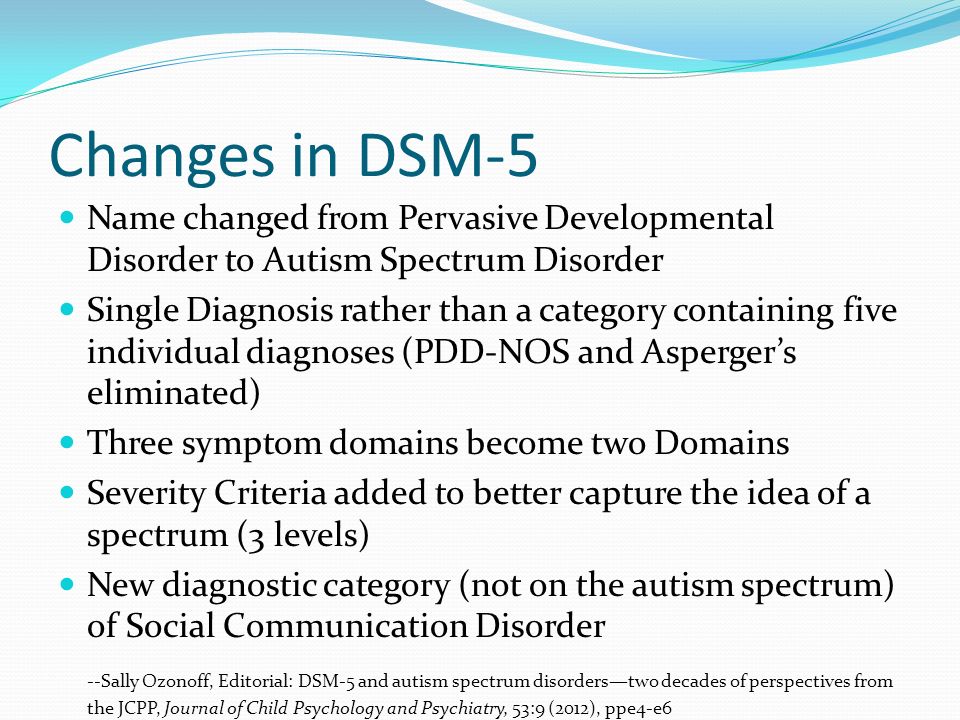

According to the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the publisher of the DSM-5, the major change with personality disorders is that they are no longer coded on Axis II in the DSM-5, because DSM-5 has done away with the duplicative and confusing nature of “axes” for diagnostic coding.

Prior to the DSM-5, mental disorders and health concerns of a person were coded in five separate areas — or axes — in the DSM. According to the APA, this multiaxial system was “introduced in part to solve a problem that no longer exists: Certain disorders, like personality disorders, received inadequate clinical and research focus. As a consequence, these disorders were designated to Axis II to ensure they received greater attention.”

Since there really was no meaningful difference in the distinction between these two different types of mental disorders, they axis system became unnecessary in the DSM-5. The new system combines the first three axes outlined in past editions of DSM into one axis with all mental and other medical diagnoses. “Doing so removes artificial distinctions among conditions,” says the APA, “benefiting both clinical practice and research use.”

“Doing so removes artificial distinctions among conditions,” says the APA, “benefiting both clinical practice and research use.”

Personality Disorders in the DSM-5

The good news is that none of the criteria for personality disorders have changed in the DSM-5. While several proposed revisions were drafted that would have significantly changed the method by which individuals with these disorders are diagnosed, the American Psychiatric Association Board of Trustees ultimately decided to retain the DSM-IV categorical approach with the same 10 personality disorders.

A new hybrid personality model was introduced in the DSM-5’s Section III (disorders requiring further study) that included evaluation of impairments in personality functioning (how an individual typically experiences himself or herself as well as others) plus five broad areas of pathological personality traits. In the new proposed model, clinicians would assess personality and diagnose a personality disorder based on an individuals particular difficulties in personality functioning and on specific patterns of those pathological traits.

The hybrid methodology retains six personality disorder types:

- Borderline Personality Disorder

- Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder

- Avoidant Personality Disorder

- Schizotypal Personality Disorder

- Antisocial Personality Disorder

- Narcissistic Personality Disorder

According to the APA, each type is defined by a specific pattern of impairments and traits. This approach also includes a diagnosis of Personality DisorderTrait Specified (PD-TS) that could be made when a Personality Disorder is considered present, but the criteria for a specific personality disorder are not fully met. For this diagnosis, the clinician would note the severity of impairment in personality functioning and the problematic personality trait(s).

This hybrid dimensional-categorical model and its components seek to address existing issues with the categorical approach to personality disorders. APA hopes that inclusion of the new methodology in Section III of DSM-5 will encourage research that might support this model in the diagnosis and care of patients, as well as contribute to greater understanding of the causes and treatments of personality disorders.

Furthermore, the APA notes:

For the general criteria for personality disorder presented in Section III, a revised personality functioning criterion (Criterion A) has been developed based on a literature review of reliable clinical measures of core impairments central to personality pathology. Furthermore, the moderate level of impairment in personality functioning required for a personality disorder diagnosis was set empirically to maximize the ability of clinicians to identify personality disorder pathology accurately and efficiently.

The diagnostic criteria for specific DSM-5 personality disorders in the alternative model are consistently defined across disorders by typical impairments in personality functioning and by characteristic pathological personality traits that have been empirically determined to be related to the personality disorders they represent.

Diagnostic thresholds for both Criterion A and Criterion B have been set empirically to minimize change in disorder prevalence and overlap with other personality disorders and to maximize relations with psychosocial impairment.

A diagnosis of personality disordertrait specified — based on moderate or greater impairment in personality functioning and the presence of pathological personality traits — replaces personality disorder not otherwise specified and provides a much more informative diagnosis for patients who are not optimally described as having a specific personality disorder. A greater emphasis on personality functioning and trait-based criteria increases the stability and empirical bases of the disorders.

Personality functioning and personality traits also can be assessed whether or not an individual has a personality disorder, providing clinically useful information about all patients. The DSM-5 Section III approach provides a clear conceptual basis for all personality disorder pathology and an efficient assessment approach with considerable clinical utility.

Annotated Index of Articles of the National Psychological Journal

How Our Word Will Respond

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.126-130

No. 3. p.126-130

Tsukerman G.A.

moreDownload PDF

230

Life with love as the meaning of being in the existential paradigm of relationships

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.119-125

Utrobina V.G.

moreDownload PDF

245

Ecopsychological interactions of young children with other subjects of the social environment

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.108-188

Lidskaya E.V. Panov V.I.

moreDownload PDF

222

Application of the method "Diagnosis of the mental development of children from birth to three years" in clinical psychology and psychiatry

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.97-107

No. 3. p.97-107

Trushkina S.V. Skoblo G.V.

moreDownload PDF

227

The Russian Museum of Childhood: On the Development of a Scientific Concept

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.89-96

Sobkin V. S. Kalashnikova E. A. Lykova T. A.

moreDownload PDF

189

From Responsiveness to Self-Organization: A Comparison of Approaches to the Child in Waldorf and Directive Pedagogy

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.77-88

Abdulaeva E.A.

moreDownload PDF

141

E.O. Smirnova on the moral education of children

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.69-76

Burlakova I.A.

moreDownload PDF

142

Modern childhood and preschool education are on the protection of the rights of the child: to the 75th anniversary of the birth of E. O. Smirnova

O. Smirnova

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.60-68

Karabanova O.A.

moreDownload PDF

128

E.O. Smirnova in the practice of education

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.52-59

Galiguzova L.N. Meshcheryakova S.Yu.

moreDownload PDF

118

Funny and scary in children's narratives: a cognitive aspect

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.44-51

Shiyan O.A.

moreDownload PDF

175

E.O. Smirnova to the evaluation of toys for children

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.35-43

Ryabkova I.A. Sheina E.G.

moreDownload PDF

177

The Artist in the Child

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.26-34

No. 3. p.26-34

Melik-Pashaev A.A.

moreDownload PDF

175

Children's play as a territory of freedom

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.13-25

Yudina E.G.

moreDownload PDF

159

The Dialectical Structure of Preschooler Play

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.4-12

Veraksa N.E.

moreDownload PDF

161

Introduction

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.3

Zinchenko Yu. P.

moreDownload PDF

168

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorders and Autism: Medical Care in the USA and Ukraine

"Child psychiatry in the United States has developed rapidly over the past ten years," says Prof. Wanda Fremont. She currently runs the Child Psychiatry Clinic and is Director of the Specialized Postgraduate Program in Child Psychiatry at SUNY Upstate New York Medical University. - The adoption of the biopsychosocial model is a major recent development in child psychiatry. Also, the development of genetics, the understanding of its influence on psychopathology and sensitivity to the treatment of many disorders, has made a very significant contribution. In the past, we often discussed the topic “nature vs. nurture”: what is decisive in the manifestation of symptoms - internal factors (constitution) or upbringing? Now, with the development of genetics, we have a much better understanding of how biological and environmental factors interact with each other and determine the clinical picture of the disorder. For example, we are well aware that stress leads to biological changes in the brain, and vice versa, a positive, benevolent upbringing environment can have a protective effect on the brain, increasing its resistance to psychic trauma.

Wanda Fremont. She currently runs the Child Psychiatry Clinic and is Director of the Specialized Postgraduate Program in Child Psychiatry at SUNY Upstate New York Medical University. - The adoption of the biopsychosocial model is a major recent development in child psychiatry. Also, the development of genetics, the understanding of its influence on psychopathology and sensitivity to the treatment of many disorders, has made a very significant contribution. In the past, we often discussed the topic “nature vs. nurture”: what is decisive in the manifestation of symptoms - internal factors (constitution) or upbringing? Now, with the development of genetics, we have a much better understanding of how biological and environmental factors interact with each other and determine the clinical picture of the disorder. For example, we are well aware that stress leads to biological changes in the brain, and vice versa, a positive, benevolent upbringing environment can have a protective effect on the brain, increasing its resistance to psychic trauma. Over the past decade, we have paid much attention to the study of protective factors that determine resistance to stress, and we have worked purposefully in the field of psychiatric prevention. For example, it has been found important for prevention to identify the strengths of families and patients and work to strengthen them. Great attention is now being paid to the development of individual treatment plans, which, along with consideration of psychopathological aspects, necessarily include measures to improve psychosocial factors. Over the past ten years, much attention has been paid to working not only with families, but also with schools, public organizations in order to provide adequate and comprehensive assistance and support to children. Great importance is attached to a multidisciplinary, team approach to the treatment of children at their place of residence. Helping children and their families directly in the community is the central focus of development in the field of child psychiatry today.

Over the past decade, we have paid much attention to the study of protective factors that determine resistance to stress, and we have worked purposefully in the field of psychiatric prevention. For example, it has been found important for prevention to identify the strengths of families and patients and work to strengthen them. Great attention is now being paid to the development of individual treatment plans, which, along with consideration of psychopathological aspects, necessarily include measures to improve psychosocial factors. Over the past ten years, much attention has been paid to working not only with families, but also with schools, public organizations in order to provide adequate and comprehensive assistance and support to children. Great importance is attached to a multidisciplinary, team approach to the treatment of children at their place of residence. Helping children and their families directly in the community is the central focus of development in the field of child psychiatry today.

Over the past ten years, no less significant progress has been made in the field of biology of mental disorders. These advances relate to discoveries in both child psychopathology and psychopharmacology. However, I believe that the success of psychopharmacology is a double-edged sword. The danger is that due to the lack of child psychiatrists in America, specialists and general practitioners are tempted to prescribe more and more drugs in order to serve as many patients as possible in as little time as possible. This leads to the fact that currently drugs are used excessively widely. We are increasingly confronted with the side effects and complications of ill-conceived drug therapy. Physicians are sometimes hasty in prescribing psychotropic drugs without further investigation of psychosocial stressors. Thus, one of the most important tasks of a child psychiatrist is to ensure a balanced approach to the treatment of a child by different specialists, to monitor and control the implementation of psychosocial interventions and biological treatment. This reduces the risk of the child receiving an excessive amount of medication.”

This reduces the risk of the child receiving an excessive amount of medication.”

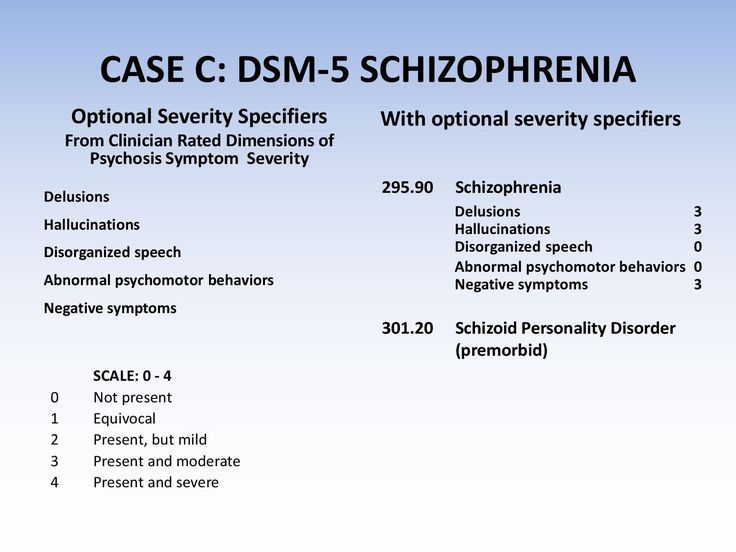

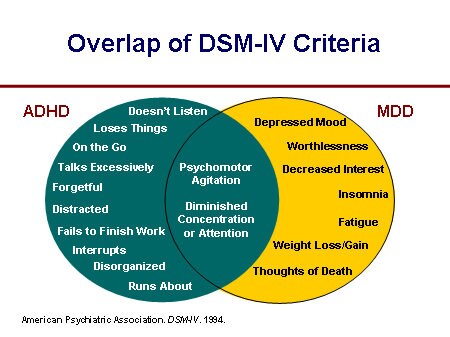

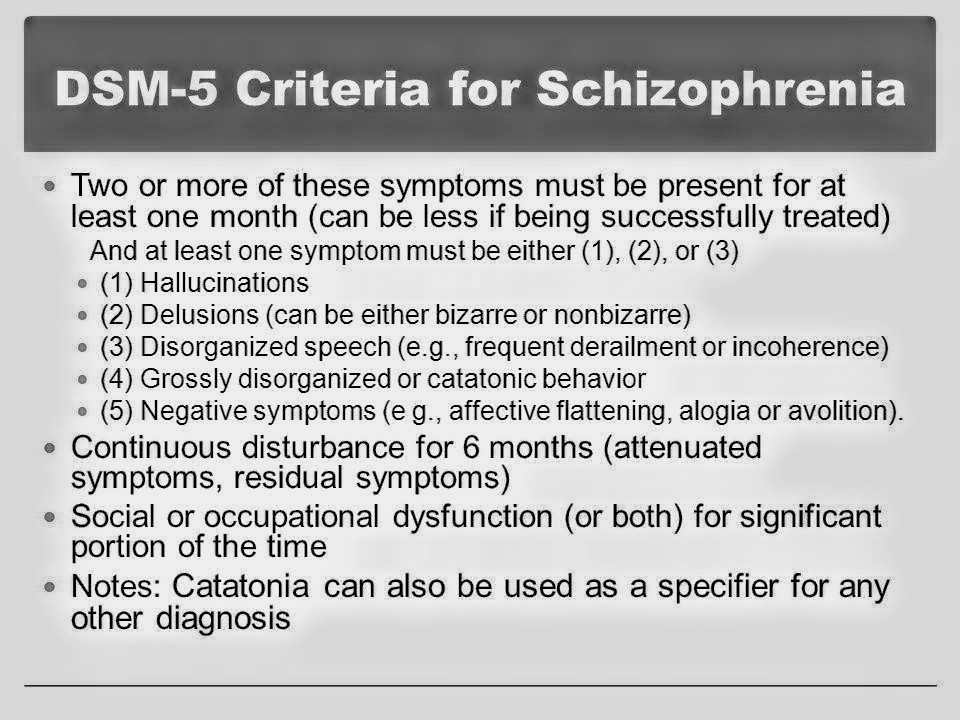

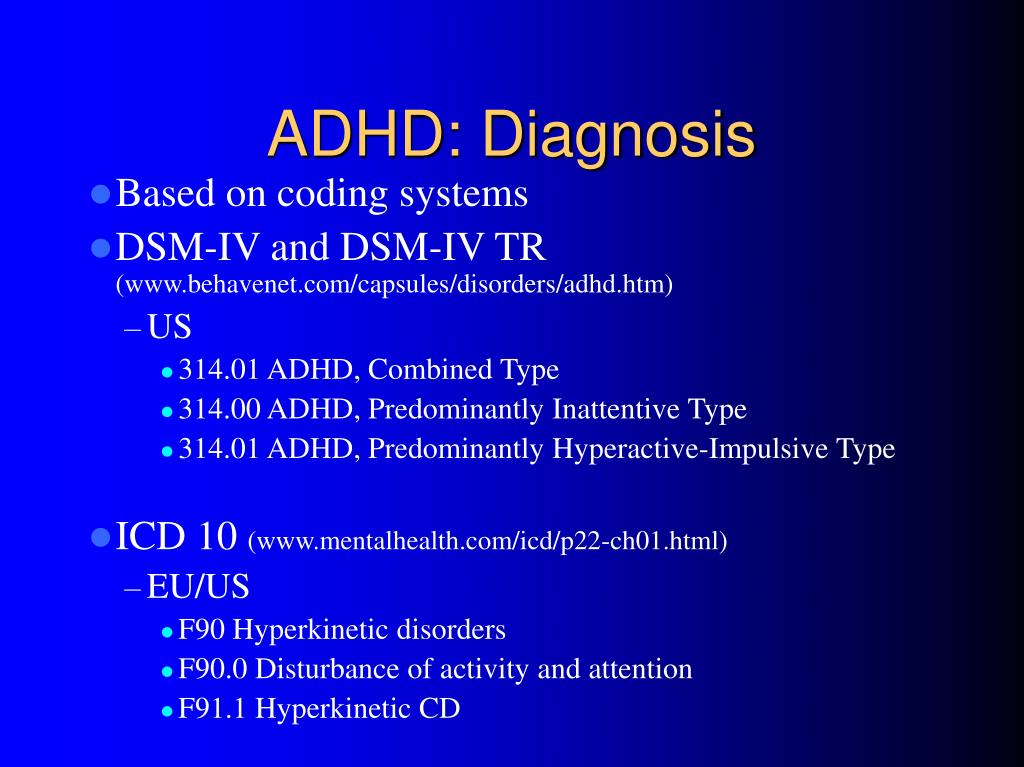

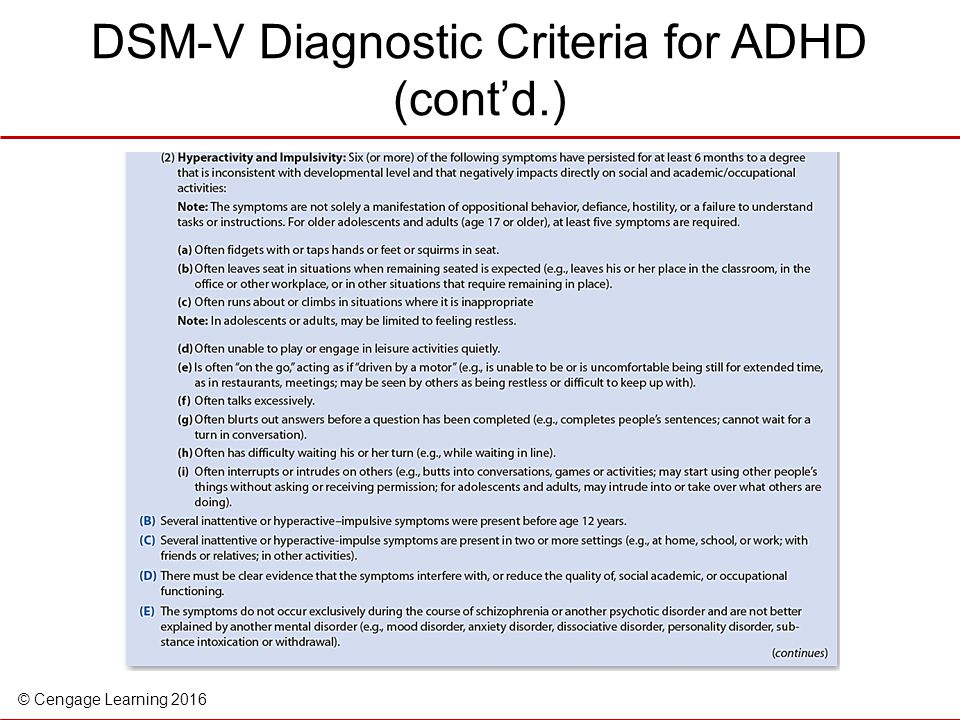

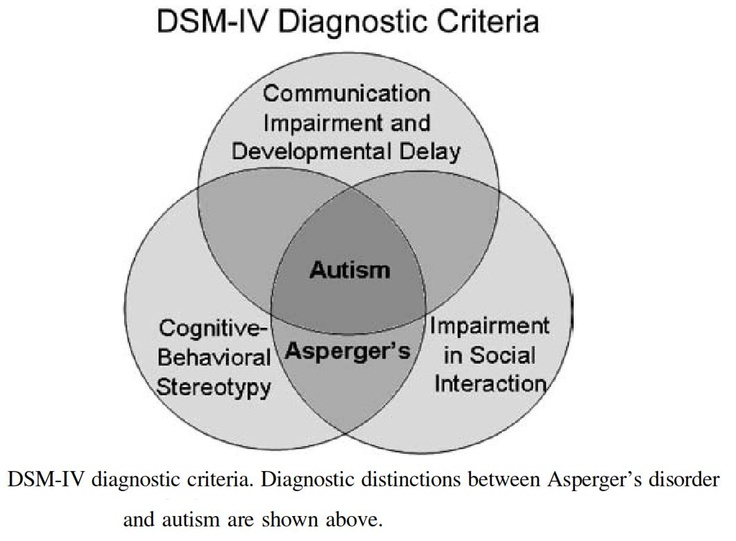

According to Dr. James Diemer, Professor of Child Psychiatry at SUNY Upstate Medical University of New York, Chief of the Children's Department of the Hutching Psychiatric Center (Syracuse, USA) , the difficulty in differential diagnosis between ADHD, autism spectrum disorders, anxiety and depressive disorders in Ukrainian child psychiatrists often arise due to the incorrect use of modern classifications (ICD-10, DSM-IV) and diagnostic criteria inextricably linked with them. In the US, children who see a child psychiatrist usually have multiple DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses. Patients with autism spectrum disorders may be diagnosed with 3–4 comorbid disorders. There are two approaches to assessing a child with ADHD using the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria: from Axis I (clinical diagnosis) to Axis V (level of social maladaptation) or vice versa, from Axis V to Axis I For the diagnosis of ADHD, firstly, it is necessary to have significant maladjustment in various social situations: not only at home, but also at school and / or in other forms of social interaction, for example, when communicating with other children at leisure. Secondly, it is necessary to determine which symptom is causing the impairment of social functioning - inattention and / or impulsivity and hyperactivity. So, when evaluating the behavior of a child in a school environment, the main attention should be paid to such symptoms as increased distractibility, the inability to maintain attention according to age, forgetfulness, the presence of difficulties in organizing one's workplace, lack of concentration when doing homework, when collecting a portfolio. When observing preschool children, it is necessary to pay attention to symptoms such as hyperactivity, restlessness, impulsivity, the severity of which will not allow children to learn the school curriculum.

Secondly, it is necessary to determine which symptom is causing the impairment of social functioning - inattention and / or impulsivity and hyperactivity. So, when evaluating the behavior of a child in a school environment, the main attention should be paid to such symptoms as increased distractibility, the inability to maintain attention according to age, forgetfulness, the presence of difficulties in organizing one's workplace, lack of concentration when doing homework, when collecting a portfolio. When observing preschool children, it is necessary to pay attention to symptoms such as hyperactivity, restlessness, impulsivity, the severity of which will not allow children to learn the school curriculum.

Pediatricians, family doctors, general practitioners also provide psychiatric care to children. They deal with both the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders, says Prof. Diemer. It is these specialists who provide medical care to most children with ADHD. The interpretation adopted in Ukraine of the norms of the Law “On Mental Health” is surprising. The law adopted to bring the rights of consumers of psychiatric care in Ukraine in line with the values of Western democracies outlaws the models of its organization operating throughout the world, primarily the provision of care at the primary stage of medical care by general practitioners. In the United States, 75% of children with ADHD receive medical care from general practitioners. The most severe of them, primarily those with multiple comorbid disorders, get to child psychiatrists. Children with mental disorders treated by pediatricians, family physicians, and general practitioners are more likely to have a single diagnosis along axis I.

The law adopted to bring the rights of consumers of psychiatric care in Ukraine in line with the values of Western democracies outlaws the models of its organization operating throughout the world, primarily the provision of care at the primary stage of medical care by general practitioners. In the United States, 75% of children with ADHD receive medical care from general practitioners. The most severe of them, primarily those with multiple comorbid disorders, get to child psychiatrists. Children with mental disorders treated by pediatricians, family physicians, and general practitioners are more likely to have a single diagnosis along axis I.

Professor Freemont, speaking about the role of pediatricians and family doctors in providing psychiatric care to children, emphasizes that without this quality psychiatric care for children cannot be organized. “My experience is that generalists are usually very open to learning about child psychiatry,” says Dr. Freemont.

It is known that 25-30% of visits to general practitioners in the United States are associated with behavioral disorders in children and emotional instability. In the future, it will be especially important for such patients to maintain cooperation with general practitioners. The relationships that have been built with general practitioners in central New York and their training have made it possible to increase the number of children receiving adequate mental health care. The goal of training primary care physicians is to acquire competency in the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of common, uncomplicated, most common disorders in child psychiatry, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety and depressive disorders. Important is the ability of general practitioners to recognize even more serious mental disorders and to refer such patients to a subspecialist, a child psychiatrist. Also important are the ability and readiness of general practitioners to accept such a patient back after stabilization of his condition by a child psychiatrist. Primary care physicians should continue qualified supervision of such a child.

In the future, it will be especially important for such patients to maintain cooperation with general practitioners. The relationships that have been built with general practitioners in central New York and their training have made it possible to increase the number of children receiving adequate mental health care. The goal of training primary care physicians is to acquire competency in the diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of common, uncomplicated, most common disorders in child psychiatry, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety and depressive disorders. Important is the ability of general practitioners to recognize even more serious mental disorders and to refer such patients to a subspecialist, a child psychiatrist. Also important are the ability and readiness of general practitioners to accept such a patient back after stabilization of his condition by a child psychiatrist. Primary care physicians should continue qualified supervision of such a child.

In the USA, there is a pilot program developed by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in addition to the FCGME. This is a three-year specialization program in child psychiatry designed for general practitioners. Currently, there are 7 such centers operating at US academic centers. The advantage of such specialization for general practitioners is the possibility of acquiring a narrow specialization in child psychiatry, bypassing training in adult psychiatric residency. However, 3 years instead of 4-5 years of study (which would be necessary to complete a full residency) is still sufficient time to receive quality training in child psychiatry.

This is a three-year specialization program in child psychiatry designed for general practitioners. Currently, there are 7 such centers operating at US academic centers. The advantage of such specialization for general practitioners is the possibility of acquiring a narrow specialization in child psychiatry, bypassing training in adult psychiatric residency. However, 3 years instead of 4-5 years of study (which would be necessary to complete a full residency) is still sufficient time to receive quality training in child psychiatry.

Some general practitioners in the United States spend an enormous amount of time acquiring additional education in child psychiatry through attending conferences and collaborating with child psychiatrists. These doctors often become very knowledgeable child psychiatrists, they understand the importance of psychological evaluation of the child, they are able to assess the limitations of general practitioners, they are aware of the importance of seeking help from a child psychiatrist in a timely manner, and they are competent in the treatment of depressive and anxiety disorders in children. They feel competent in helping children with uncomplicated cases.

They feel competent in helping children with uncomplicated cases.

In rural areas where there is no adequate child mental health service, general practitioners are forced to care for children with more complex mental disorders. This issue has not been resolved at this time. Telecommunications are widely used to assist general practitioners working in remote areas of the United States. Telepsychiatric consultations have proven themselves well. The possibilities of telemedicine are also used to train specialists. The use of telepsychiatry is constantly growing. It is used to assist general practitioners who do not have access to child psychiatrists.

According to Professor Dimer, it is not necessary to conduct psychological testing or use additional scales and tests to diagnose ADHD. As a rule, observation of the child and a carefully collected anamnesis, including family history, are sufficient. However, in some cases, in order to determine the structure of the neuropsychological deficit, the Continuous performance test can be useful, which allows you to identify the prevalence of inattention or impulsivity, the presence of problems with activation, attracting attention, or its stability (vigilance). Also in the United States, screening diagnostic scales for teachers and parents are widely used.

Also in the United States, screening diagnostic scales for teachers and parents are widely used.

Children with ADHD usually respond well to the novelty of the situation and, when examined in the doctor's office, are interested in the game and do not appear hyperactive and inattentive at all. Before drawing clinical conclusions, it is necessary to obtain information about the behavior of such a child in other social situations, at school and at home. Unlike the results of psychological testing, it is not possible to make a reasonable diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder without this information. If results from various sources indicate functional disorders that meet DSM-IV criteria, this helps both in establishing the diagnosis of ADHD and determining its clinical subtype, and in further monitoring the severity of symptoms during treatment.

Huge, often paramount attention in the diagnosis of ADHD in children should be given to the study of family history. Attention disorders in parents often have to be taken into account when planning a child's therapy. It is difficult, for example, to count on the fact that a father who has problems with self-organization will be able to properly organize the child's working day without the help of a therapist.

Attention disorders in parents often have to be taken into account when planning a child's therapy. It is difficult, for example, to count on the fact that a father who has problems with self-organization will be able to properly organize the child's working day without the help of a therapist.

When diagnosing ADHD, it must also be kept in mind that hyperactivity and inattention may be non-specific symptoms of disorders such as epilepsy, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and other anxiety disorders. Inattention and hyperactivity can be explained by a delay in the development of the child, disorders from the autism spectrum. Children who are lagging behind in speech development often misunderstand addressed speech, do not have inner speech, are unable to express themselves, phenotypically resembling children with ADHD. Children with mental retardation may also not fully understand instructions and rules and therefore be unable to adequately respond to them. In some cases, absent-mindedness and hyperactivity can be explained by comorbid anxiety disorders. All diagnostic alternatives listed should be considered, excluded or taken into account.

All diagnostic alternatives listed should be considered, excluded or taken into account.

There are features of the diagnosis of ADHD in preschool children. When inattention and hyperactivity are observed in a child aged 3–6 years, their association with adverse psychosocial factors must first be excluded. At this age, children are especially sensitive to psychosocial stress, the lack of structuring of activities and time, the constancy of the rules of behavior and the requirements placed on them. Young children need the predictability of the environment of existence and life events, the balance of parental love and care, on the one hand, and educational activities and social expectations, on the other.

Before diagnosing ADHD and prescribing medication, it is necessary to make sure that the child has received the necessary psychosocial assistance, for example, the child’s parents have completed special training courses on acquiring parenting skills, the family has been provided with the necessary support at home (behavioral training for children, training to improve management behavior of the child at home, structuring the life and time of the family and other social forms of assistance).

Medical treatment for ADHD in preschoolers in the United States typically begins with psychostimulants. Most of the neurometabolic, vascular drugs popular in Russia and Ukraine are not used, neuroleptics are rarely used, including atypical ones. Psychostimulants in the United States are considered the most effective and safe drugs in the treatment of ADHD. However, Professor Diemer emphasizes the fact that the younger the child, the more unpredictable is the response to such therapy. In the treatment of ADHD in preschool age, preference is given to fast-acting psychostimulants with a short half-life (methylphenidate or a mixture of amphetamine and dextromphetamine salts). After 48 hours, the child's response to the drug is evaluated. If the child has not responded to therapy in any way, it is possible to increase the dose. The first dose of the psychostimulant is recommended to be taken early in the morning, the second - at 11 o'clock in the afternoon. If taking the drug causes arousal of the child, leads to increased hyperactivity and / or irritability, therapy is stopped. The advantage of using a short-acting form is that when it is used, the unpredictability of the therapeutic reaction is compensated for by its short duration: if an undesirable stimulating effect is observed after the child takes the drug, it will last only 2-4 hours, and after 3-4 hours the drug is completely eliminated from the body. Thus, starting therapy with short-acting drugs ensures its safety and contributes to a certain level of comfort on the part of parents, teachers and doctors.

The advantage of using a short-acting form is that when it is used, the unpredictability of the therapeutic reaction is compensated for by its short duration: if an undesirable stimulating effect is observed after the child takes the drug, it will last only 2-4 hours, and after 3-4 hours the drug is completely eliminated from the body. Thus, starting therapy with short-acting drugs ensures its safety and contributes to a certain level of comfort on the part of parents, teachers and doctors.

In children with poor tolerance to methylphenidate, Dr. James Diemer considers monotherapy with α-agonists, drugs such as clonidine or guanfacine, as the treatment of choice. Unfortunately, most of the modern a-agonists are not registered in Ukraine.

In preschoolers, if possible, it is better to stick to monotherapy with short-acting psychostimulants. In older children, psychostimulants are often combined with a-agonists.

One way or another, when planning medical care for such children, one must proceed from the fact that 85% of patients with ADHD will give a good response to psychostimulant therapy.

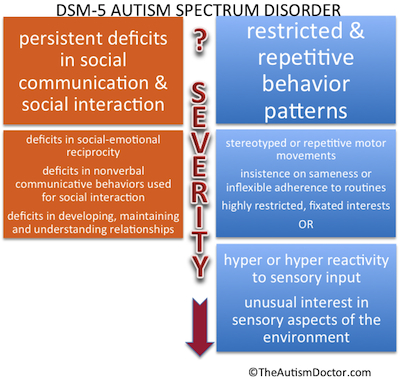

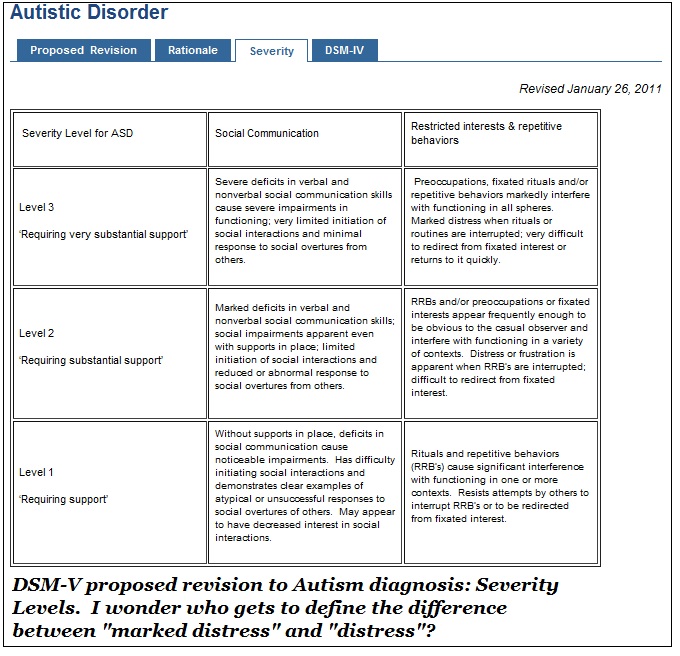

In the department where Dr. James Deemer works, many patients are diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. In the United States, the main manifestations of autism spectrum disorders are preferred to be corrected with the help of psychosocial interventions. The interventions used usually include multi-purpose training for the correction of delays in the development of fine and gross motor skills, hand-eye coordination, elimination of sensory disorders and stereotypes. Therapy may include the help of speech therapists, specialists in non-verbal communication methods. Widely used is applied behavioral analysis (ABA), an intensive behavioral program designed to shape desired behavior through reinforcement, and the so-called flurtime therapy based on play therapy techniques. The use of ABA requires specialists who have undergone special one-year training. Even in the USA there are not enough of them, therefore this program is not available for most children with pervasive developmental disorders.

Pharmacological treatment of children with autism is usually limited to treating the most severe symptoms. Drug treatment usually begins with the safest drugs that have the most favorable side effect profile. If autism is associated with symptoms of ADHD that are expressed in school and in the family, and also confirmed based on the qualification of screening results using special questionnaires for teachers and parents, child psychiatrists in the United States often prescribe small doses of psychostimulants. If there are grounds for therapy with psychostimulants, they are recommended, and not atypical antipsychotics, as is customary in Ukraine. Another advantage of psychostimulants is that within one day you can find out the reaction of the child to the drug. Their side effects are less dangerous and much less harmful than, for example, those associated with the use of atypical antipsychotics. Atypical antipsychotics in the US are used exclusively for the correction of aggressive and self-aggressive behaviors.