Bipolar 2 symptoms checklist

DSM-5 Bipolar 2 Disorder: Criteria, Symptoms, & Treatments

Why is there a bipolar 2 and a bipolar 1? There’s no depression 2 or depression 1. There’s no anxiety 3.0. What makes bipolar disorder (formerly known as manic depression) different? The quick answer is that people with bipolar 2 have enough variation in their symptoms from type 1 bipolar to justify their own unique diagnosis. But the longer answer has to do with how we think about mental illness in general. If you or someone you love is struggling with the symptoms of bipolar 2 disorder, this guide will give you answers to your practical questions as well as some theoretical context for how mental health experts treat bipolar. Let’s get started.

What Is Bipolar 2 Disorder?

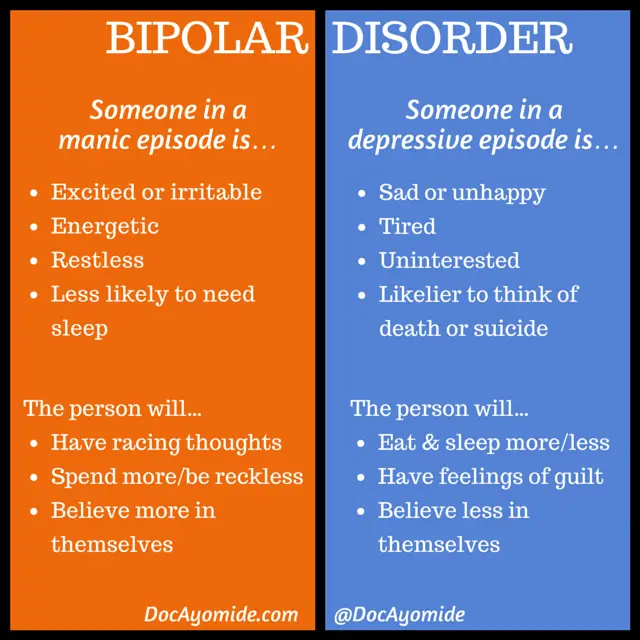

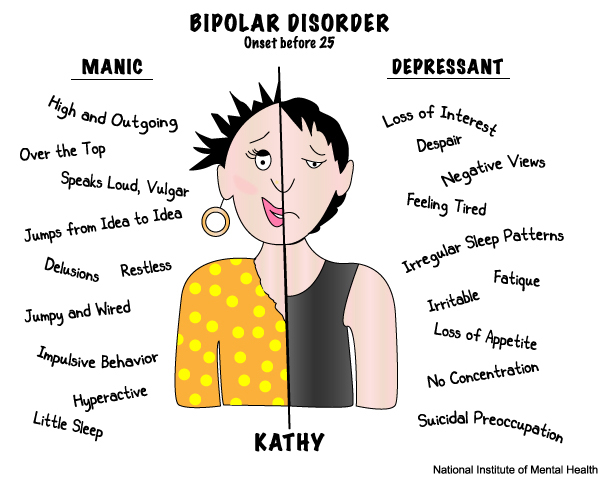

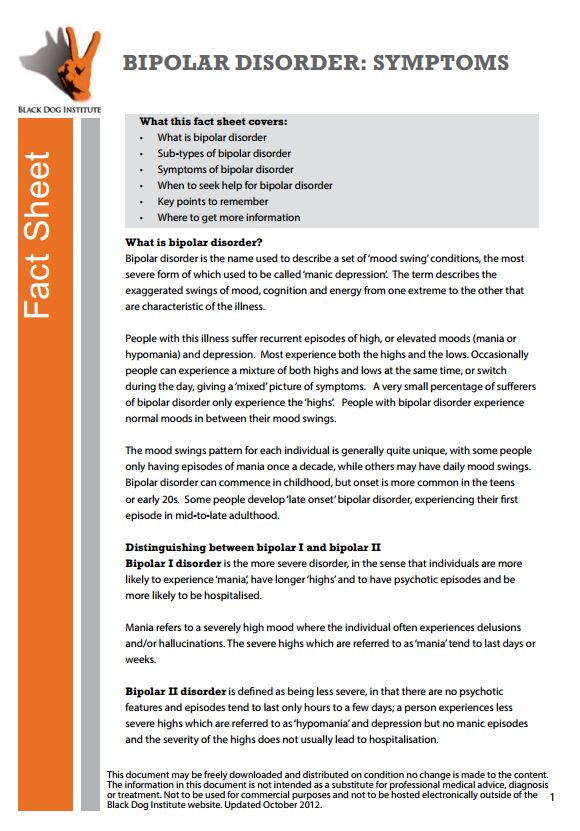

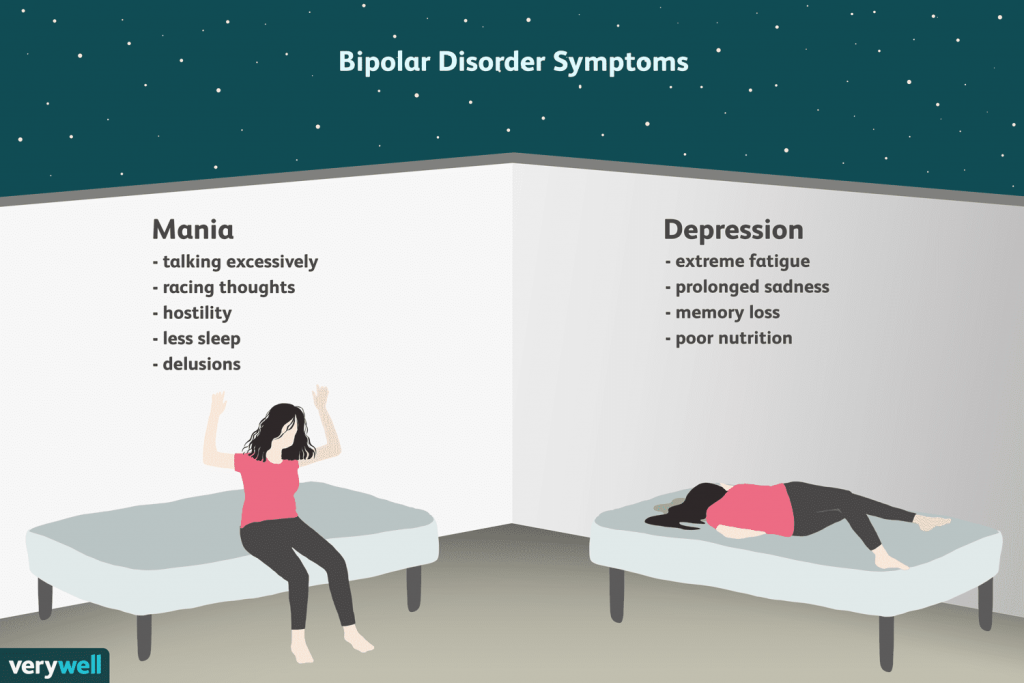

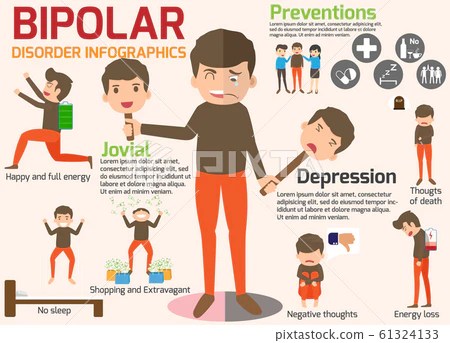

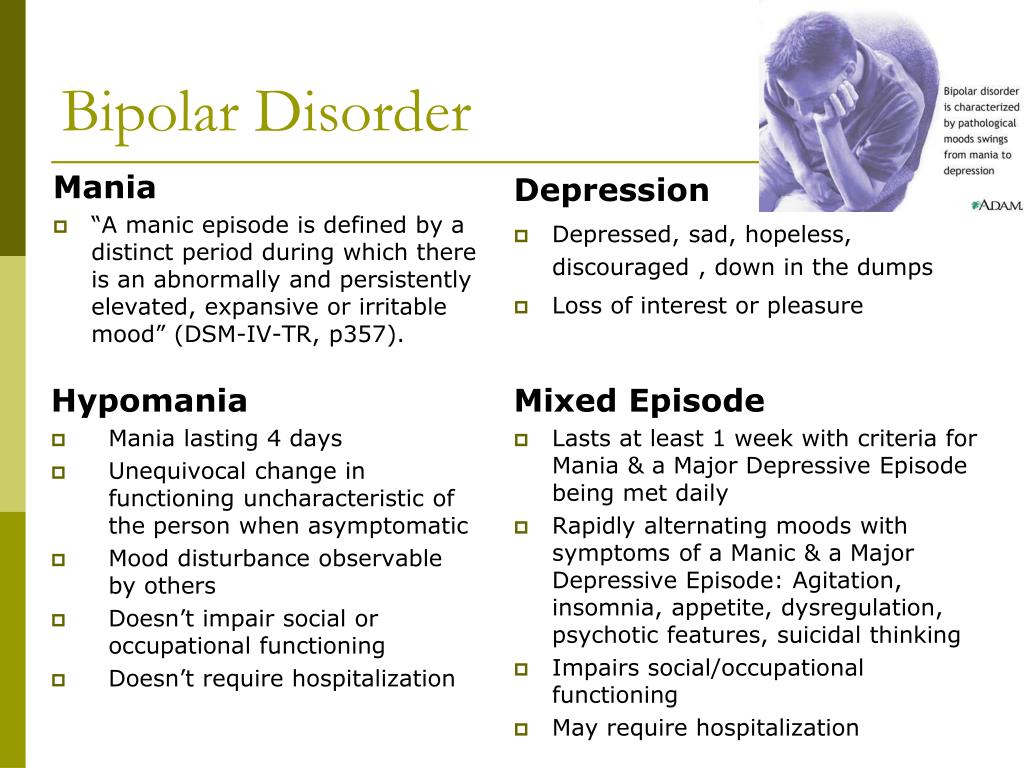

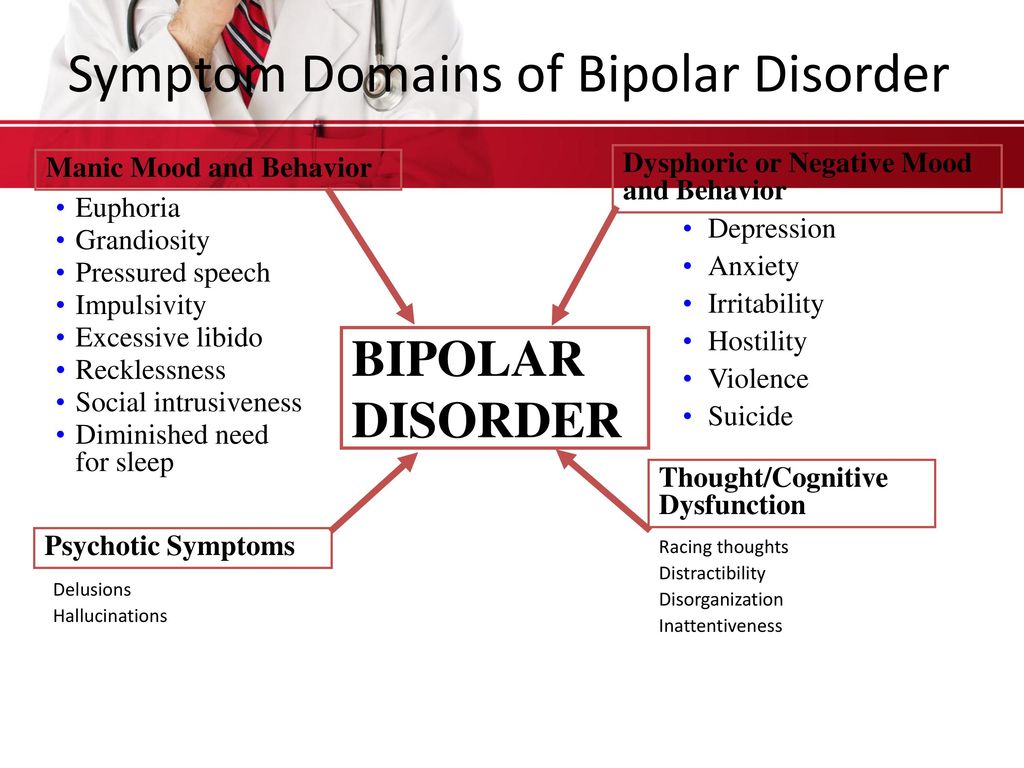

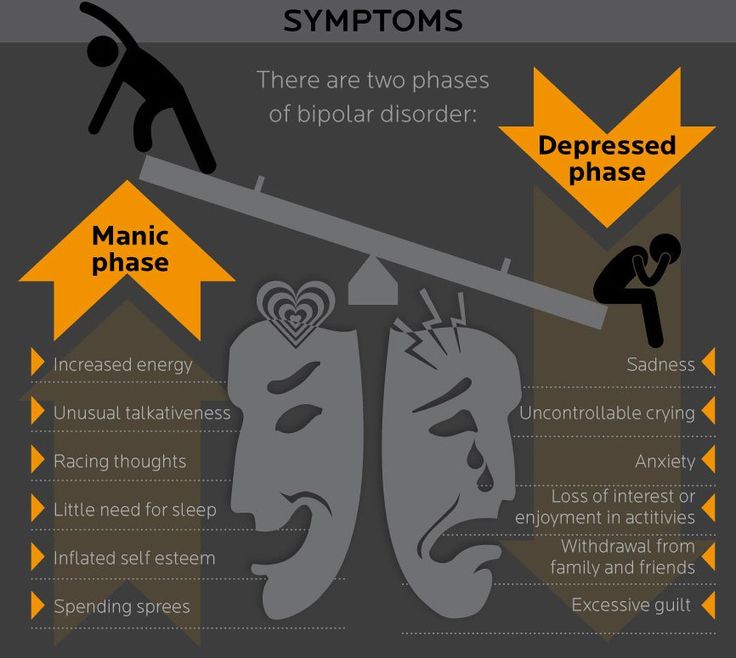

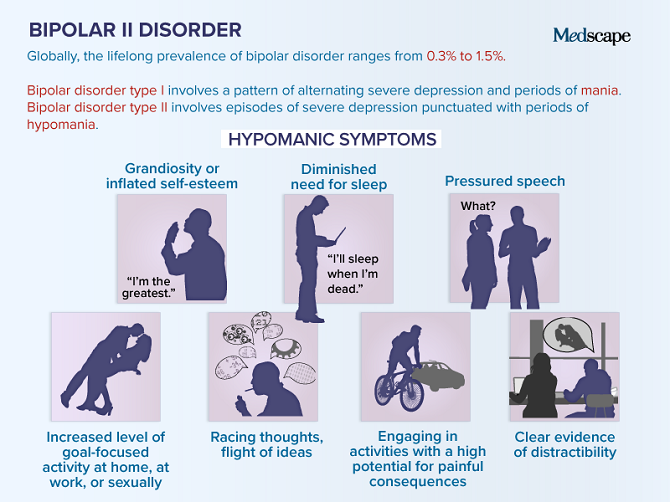

Bipolar 2 disorder is a type of bipolar disorder characterized by major depressive episodes and hypomanias, which are elevated moods that don’t meet the threshold for manias. While manic episodes are often severely debilitating, hypomanic episodes (sometimes called “baby” manic episodes) don’t impair daily living.

They might even be welcomed. But unfortunately they are just one side of a mood swing.

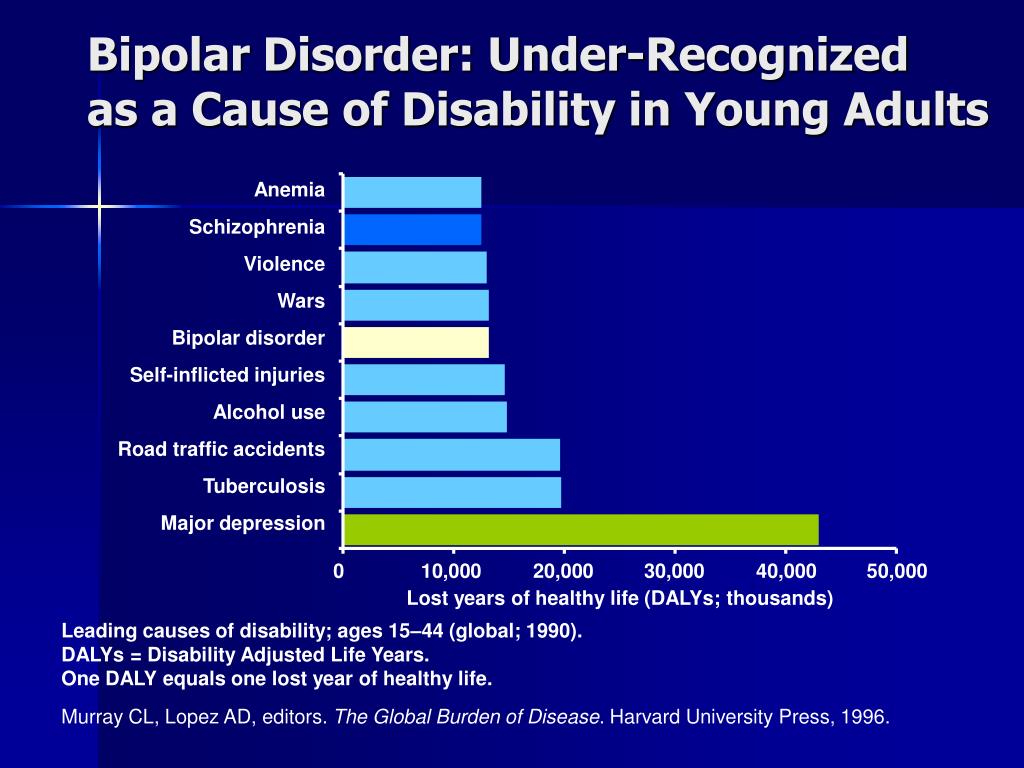

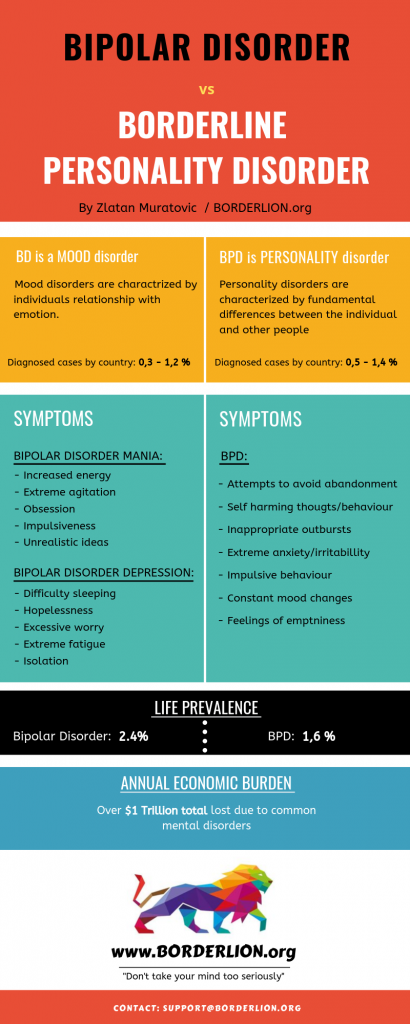

Because bipolar disorder affects emotional states, it’s commonly referred to as a mood disorder. It’s a long-term, chronic mental health condition that usually shows up by the time someone is in their mid-20s. Is bipolar type 2 serious? Yes, it’s serious because it can cause functional impairments and distress. But it can also be successfully treated and managed throughout the lifespan with medication and other interventions. It affects between 0.5 and 1% of the population.

What Is a Bipolar Disorder?

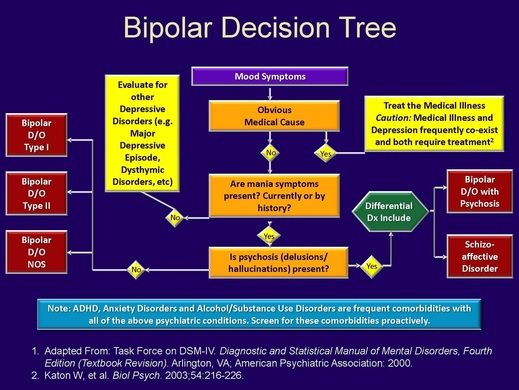

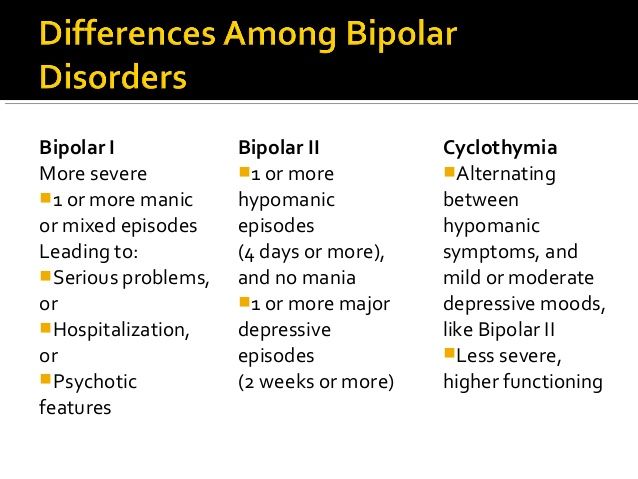

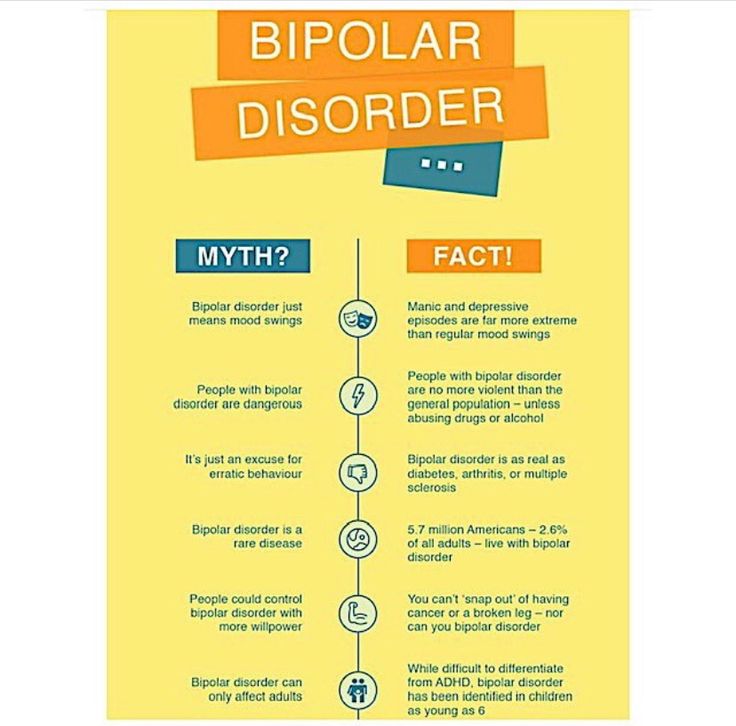

All bipolar disorders are characterized by mood swings of varying intensity. There’s some controversy about why someone can be diagnosed with bipolar 2 or bipolar 1 rather than just land somewhere on a spectrum of a single disorder. In fact, bipolar 2 wasn’t formally recognized by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) until 1994. The debate has to do with the ultimate usefulness and clinical accuracy of bipolar categories. Are bipolar 1 and 2 actually different disorders, or do their symptoms just represent different dimensions of the same disorder?

Are bipolar 1 and 2 actually different disorders, or do their symptoms just represent different dimensions of the same disorder?

Some experts advocate for thinking of bipolar disorder in terms of predominant polarity (PP) rather than different categories (see the different types of bipolar below). For example, someone may have far more depressive episodes than manic episodes, so they would be “depression predominant.” Within this diagnosis clinicians can further specify bipolar disorder by severity and duration of symptoms.

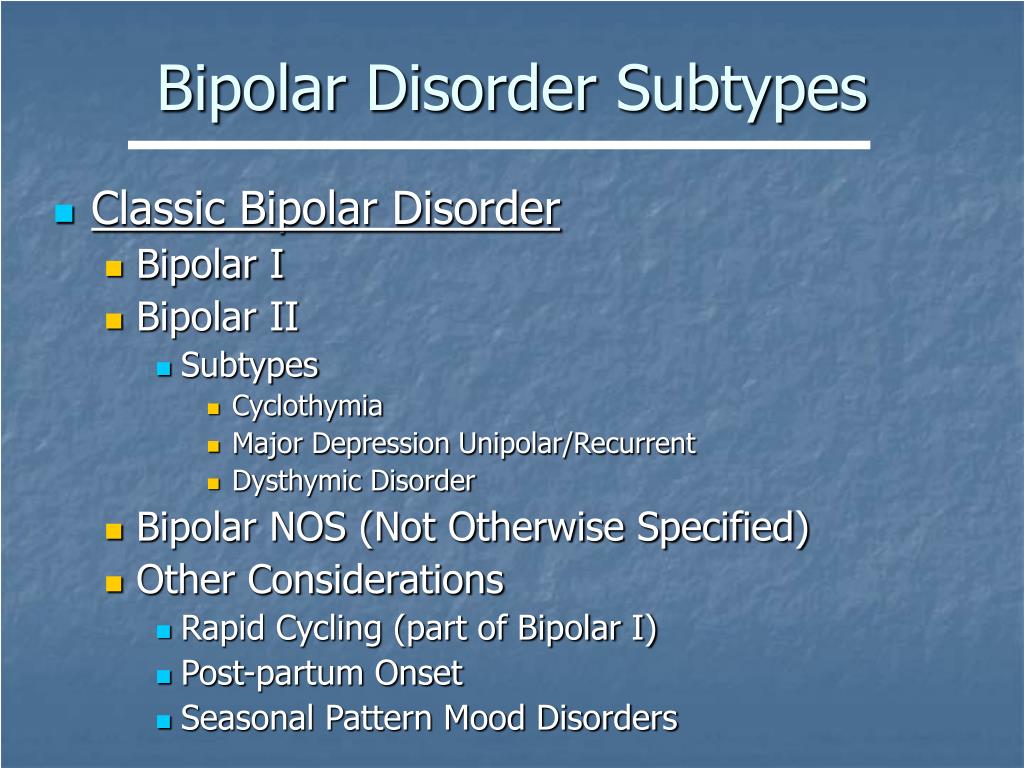

All Types of Bipolar Disorder- Bipolar 1 disorder (aka bipolar I disorder or type I bipolar)

- Bipolar 2 disorder (aka bipolar II disorder or type 2 bipolar)

- Cyclothymic disorder

- Substance/medication-induced bipolar and related disorder

- Bipolar and related disorder due to another medical condition (like thyroid disease or multiple sclerosis)

- Other specified bipolar and related disorder

- Unspecified bipolar and related disorder

DSM 5 Bipolar 2 Criteria and Bipolar 2 Symptoms

To be diagnosed with bipolar 2 according to criteria laid out in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), someone must experience A) a hypomanic episode, and B) a major depressive episode. These can occur at any point over the course of a lifetime.

These can occur at any point over the course of a lifetime.

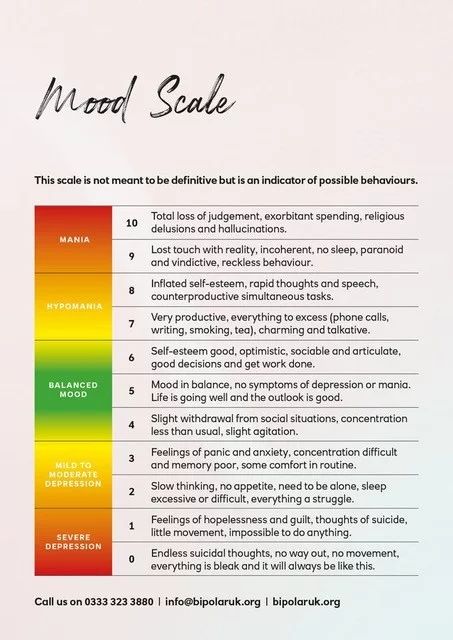

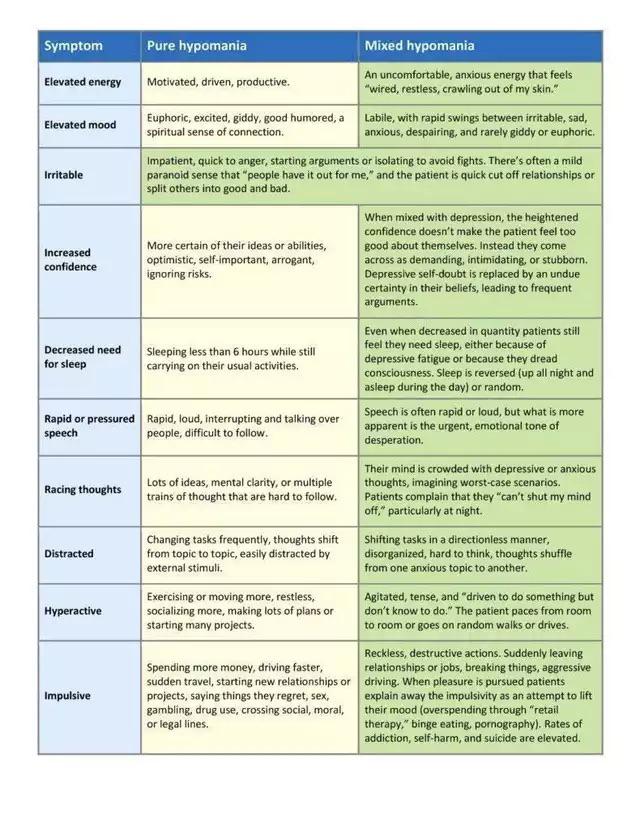

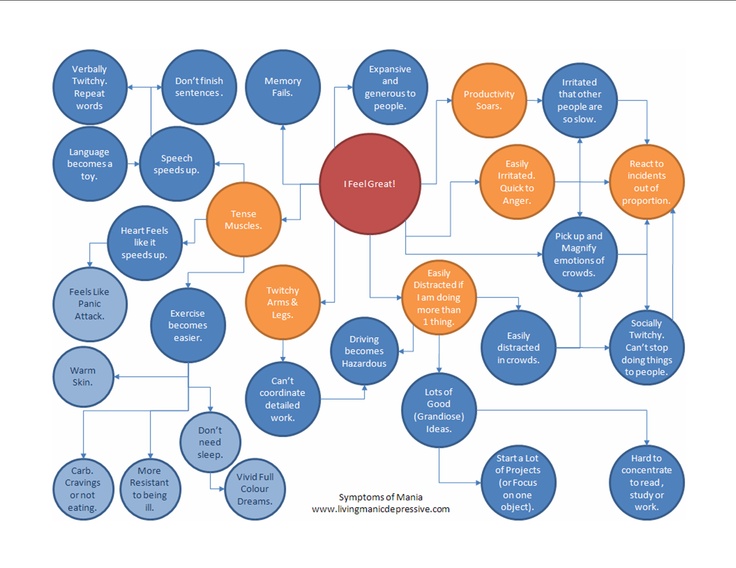

A. What qualifies as a hypomanic episode? An episode of bipolar 2 hypomania requires at least four days of elevated mood change, which might include feelings of increased energy, irritability, and expansiveness. During this time, you must have at least three of the following symptoms. If your mood has been exclusively irritable, you must have four of the following symptoms.

DSM-5 Symptoms of Hypomania- Exaggerated sense of well-being and self-confidence (euphoria), grandiosity

- Decreased need for sleep

- Unusual talkativeness

- Rushed/scattered thinking, racing thoughts

- Attention/focus issues, distractability

- Psychomotor agitation, which is an increase in purposeless physical activity (e.g., restlessness, pacing, tapping fingers or feet, abruptly starting and stopping tasks, rapidly talking, and moving items around without meaning) or increase in “activity toward goals”

- Impulsivity, poor decision-making, and risk-taking

All of these heightened, wired feelings and behaviors can’t be attributed to a substance, and they have to be so uncharacteristic that other people notice. These symptoms don’t, however, cause enough functional impairments to qualify as mania.

These symptoms don’t, however, cause enough functional impairments to qualify as mania.

B. What qualifies as a depressive episode? A major depressive episode requires at least two weeks of major depressive disorder (MDD) symptoms.

DSM-5 Symptoms of Bipolar 2 DepressionA major depressive episode involves depressive symptoms that last at least two weeks and are severe enough to cause significant emotional and occupational distress. An episode of depression must involve a depressed mood or loss of interest and pleasure (anhedonia) in addition to at least four of the following symptoms:

- Significant changes in weight and/or appetite

- Sleeping too much (hypersomnia) or too little (insomnia)

- Restlessness or sluggishness

- Loss of energy

- Feeling extreme worthlessness or guilt

- Attention difficulties, indecisiveness

- Thinking about, planning, or attempting suicide

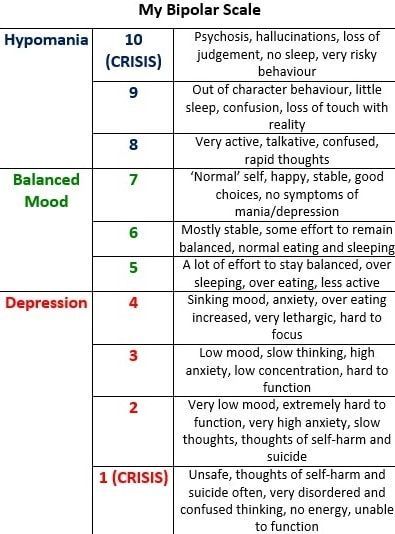

For people with bipolar 2, moods can fluctuate in different rhythms. Someone with rapid-cycling bipolar 2 will swing between moods at quicker rates (at least four episodes in a year). To qualify for a bipolar 2 diagnosis, a hypomania episode must last at least four days and a major depressive cycle must last at least 14 days. If someone’s bipolar symptoms last for two years or more and they never meet the full criteria for a hypomanic episode or a major depressive episode, they may be diagnosed with cyclothymic disorder.

Someone with rapid-cycling bipolar 2 will swing between moods at quicker rates (at least four episodes in a year). To qualify for a bipolar 2 diagnosis, a hypomania episode must last at least four days and a major depressive cycle must last at least 14 days. If someone’s bipolar symptoms last for two years or more and they never meet the full criteria for a hypomanic episode or a major depressive episode, they may be diagnosed with cyclothymic disorder.

A bipolar meltdown is the colloquial term for a period of intense emotion that might feel uncontrollable. It can sometimes manifest as rage or aggression.

Bipolar 1 vs Bipolar 2

The most significant contrast between bipolar 1 and bipolar 2 is that the former tends to gravitate toward mania while the latter tends to gravitate toward depression. If someone with bipolar 2 has a single manic episode, they can no longer be diagnosed with bipolar 2. They have another type of bipolar disorder.

Even though hypomanias are a milder form of mania, it’s not true that bipolar 2 is a milder version of bipolar 1. By definition, hypomanias don’t cause impairment, but the major depressions that characterize bipolar 2 can be brutal. These depressive episodes also tend to happen more frequently than in bipolar 1. And the persistent, unreliable mood swings of bipolar 2 can cause significant harm to someone’s life.

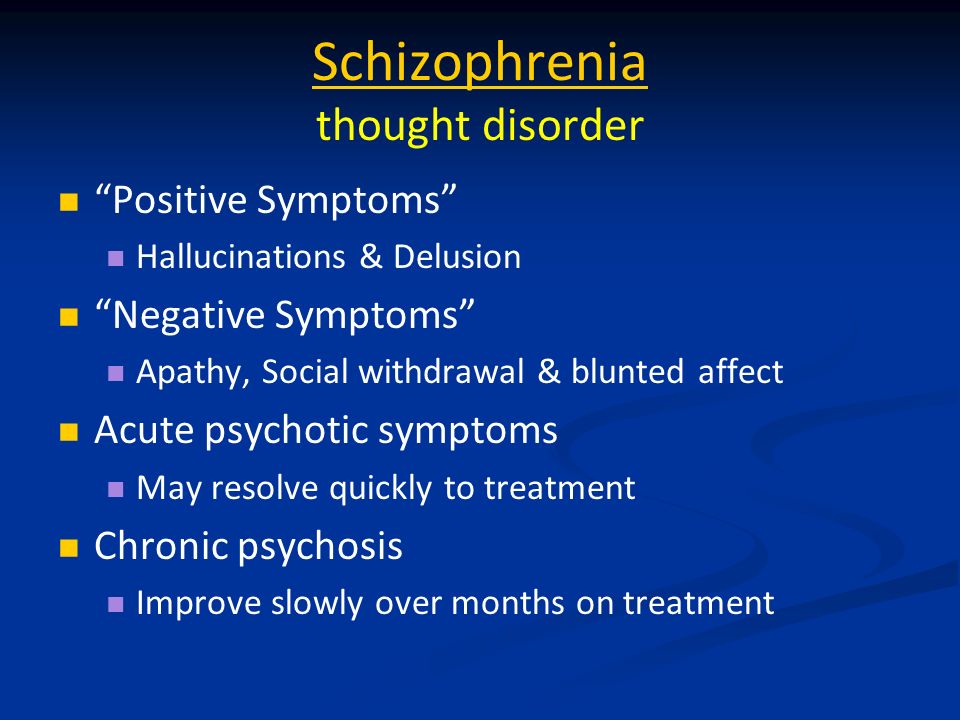

Mania vs HypomaniaMania = at least 7 days of severe functional impairment, great excitement or euphoria, dangerous decision-making, delusions, hallucinations, suicidal thoughts/actions, or even psychosis that could lead to psychiatric hospitalization

Hypomania = at least 4 days of “enhanced” emotion that doesn’t cause significant impairment or extreme personality changes. The DSM-5 also leaves room for a 2-day, “short-duration” hypomania.

What Bipolar Is Worse, 1 or 2?One type of bipolar disorder is not worse than another. They all have their ups and downs, as it were. The worst type of bipolar disorder is untreated bipolar disorder, due to its potential to inflict suffering.

They all have their ups and downs, as it were. The worst type of bipolar disorder is untreated bipolar disorder, due to its potential to inflict suffering.

What Causes Bipolar 2 Disorder?

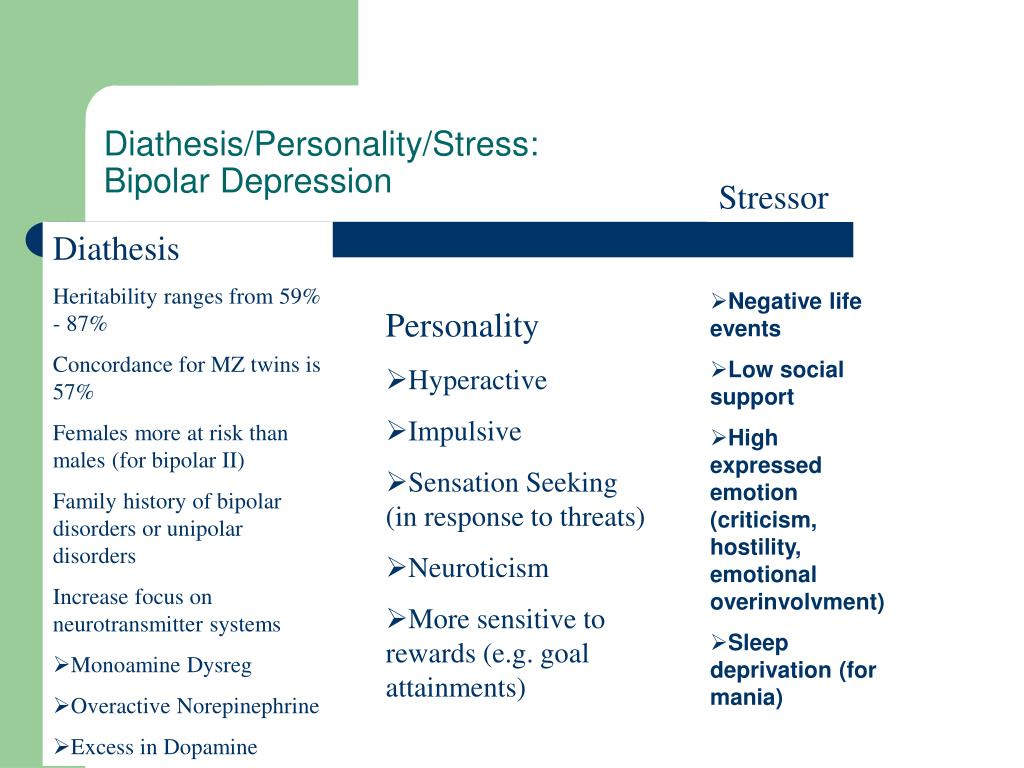

If you have a family member with bipolar 2 disorder, you have a greater risk of having the condition due to genetic factors. Its heritability might be as high as 70%. In fact, researchers recently identified 30 places (loci) on the human genome that are associated with bipolar disorder.

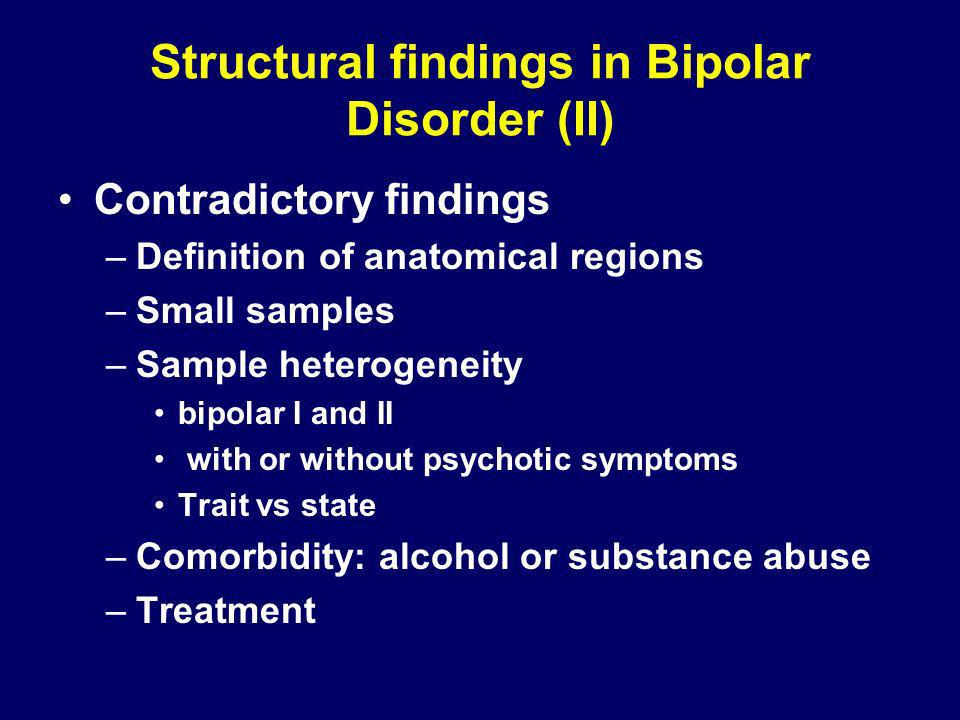

There may be physiological differences in the brains of people with bipolar disorder, but there are currently no biomarkers that can distinguish between bipolar 1 and bipolar 2.

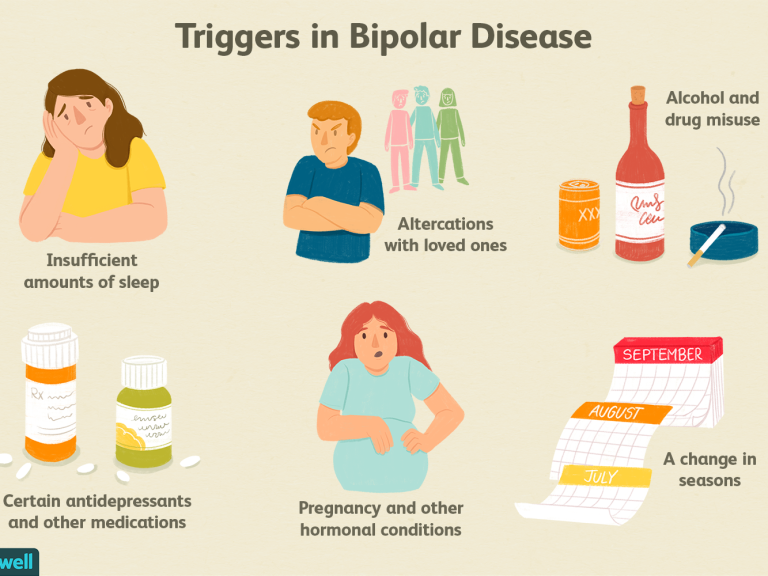

What Can Trigger Bipolar 2?As with many mental health disorders, symptoms of bipolar 2 can be triggered by stress, negative life events, changes in sleep patterns and seasonality (both associated with chronodisruption), substance use, and medications. Childbirth can also trigger hypomanic episodes.

What Is the Impact of Bipolar 2 Disorder?

Unpredictable mood swings and clinical depression can both be incredibly disruptive to someone’s life. But when bipolar 2 is managed well, people with the disorder can function normally. It’s only when the disorder is left untreated that someone’s biography might take a dark turn or suffer an obstruction. Living with bipolar 2 involves adhering to a treatment plan, recognizing your triggers, and knowing how to get back on your feet if you have a relapse. You can’t cure the disorder, but you can definitely control the impact it has on your life.

But when bipolar 2 is managed well, people with the disorder can function normally. It’s only when the disorder is left untreated that someone’s biography might take a dark turn or suffer an obstruction. Living with bipolar 2 involves adhering to a treatment plan, recognizing your triggers, and knowing how to get back on your feet if you have a relapse. You can’t cure the disorder, but you can definitely control the impact it has on your life.

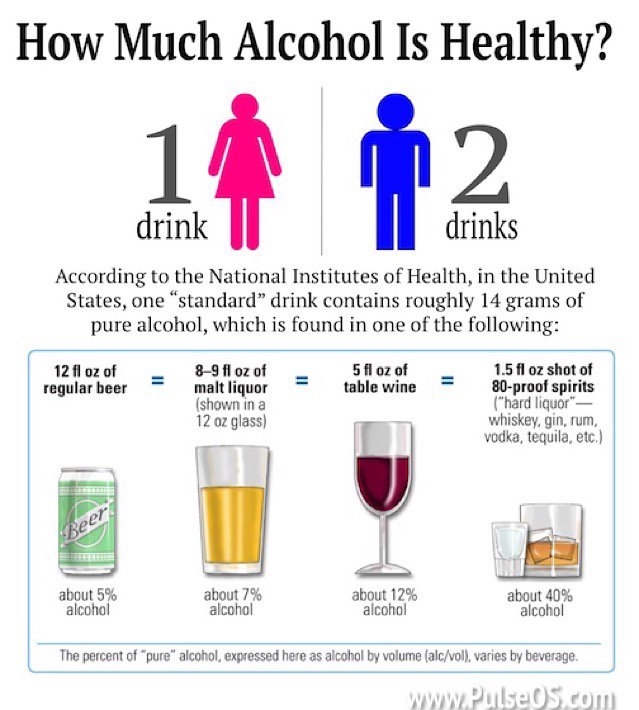

Many people with bipolar disorder find that a straighter lifestyle can also help flatten the peaks and valleys of their mood swings. This means they stick to a healthy sleep schedule, exercise regularly, eat well, avoid abusing drugs and alcohol, monitor caffeine intake, and try to minimize the stress in their lives.

If their daily habits change, they might start noticing changes in their mood. These can serve as warning signs (aka prodromal symptoms) so the person knows they need to reset their routine or or take other steps to stabilize. This kind of self-awareness and self-monitoring can also lead someone with bipolar 2 to know when they need extra support from friends and family, or from a mental health professional.

This kind of self-awareness and self-monitoring can also lead someone with bipolar 2 to know when they need extra support from friends and family, or from a mental health professional.

How Is Bipolar 2 Diagnosed?

Bipolar 2 can be diagnosed according to the DSM-5 criteria mentioned above, though different mental health professionals may have different perspectives on how to think about the disorder. Some clinicians may mark that distinct boundary between type 1 and type 2, while others may take a more dimensional approach, and think of the diagnostic boundaries as more fluid.

Bipolar 2 is often misdiagnosed as major depressive disorder (MDD). This is because a depressive episode precedes a hypomanic episode, or multiple depressive episodes occur before a hypomanic episode. In addition, people with bipolar 2 and MDD can both have irritability as a symptom. And because hypomanic episodes aren’t extreme or functionally impairing, they may go unrecognized.

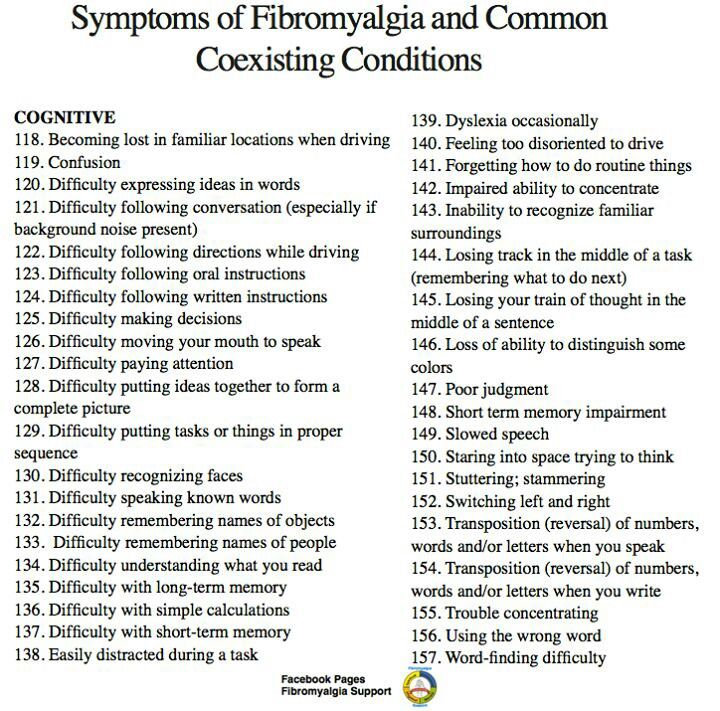

Diagnosis can also be challenging because over half of people with bipolar 2 disorder have at least three additional disorders (aka comorbid disorders), particularly anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, personality disorders, and eating disorders.

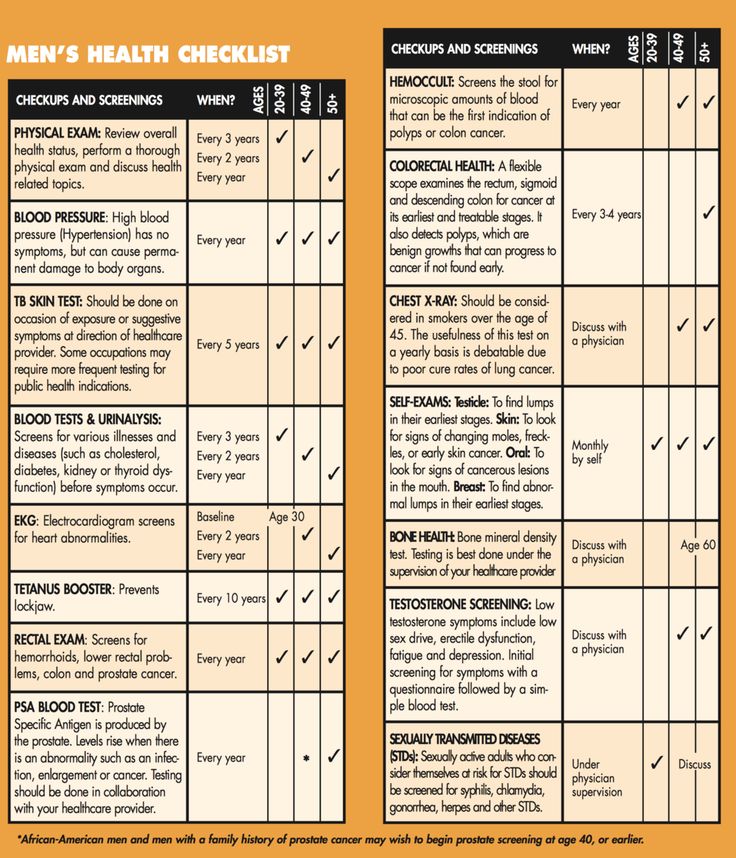

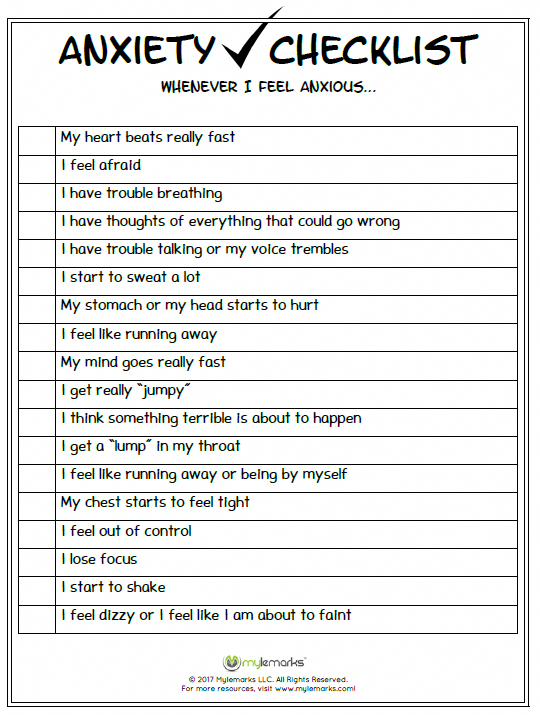

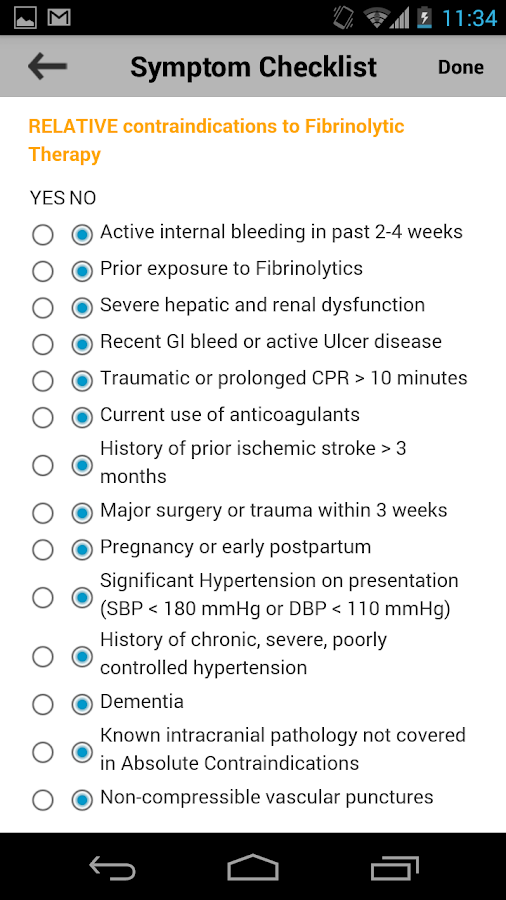

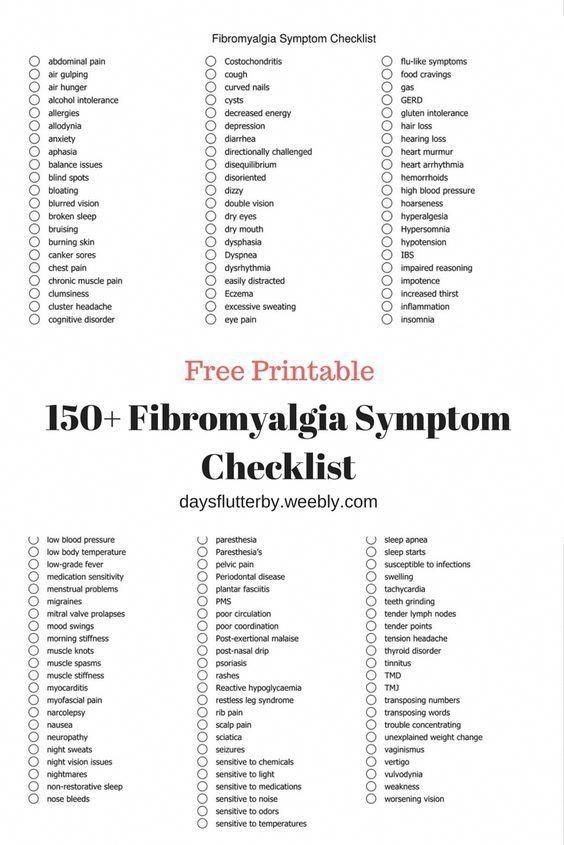

Is there a bipolar 2 test or a bipolar 2 checklist? Mental health professionals will have different ways of evaluating clients for bipolar disorder. A comprehensive test or screening often includes a physical assessment, a family history, a full psychiatric assessment, a mood disorder questionnaire (MDQ), and mood charting, which is when you keep a careful record of your daily emotions.

What Is the First-Line Treatment for Bipolar 2?

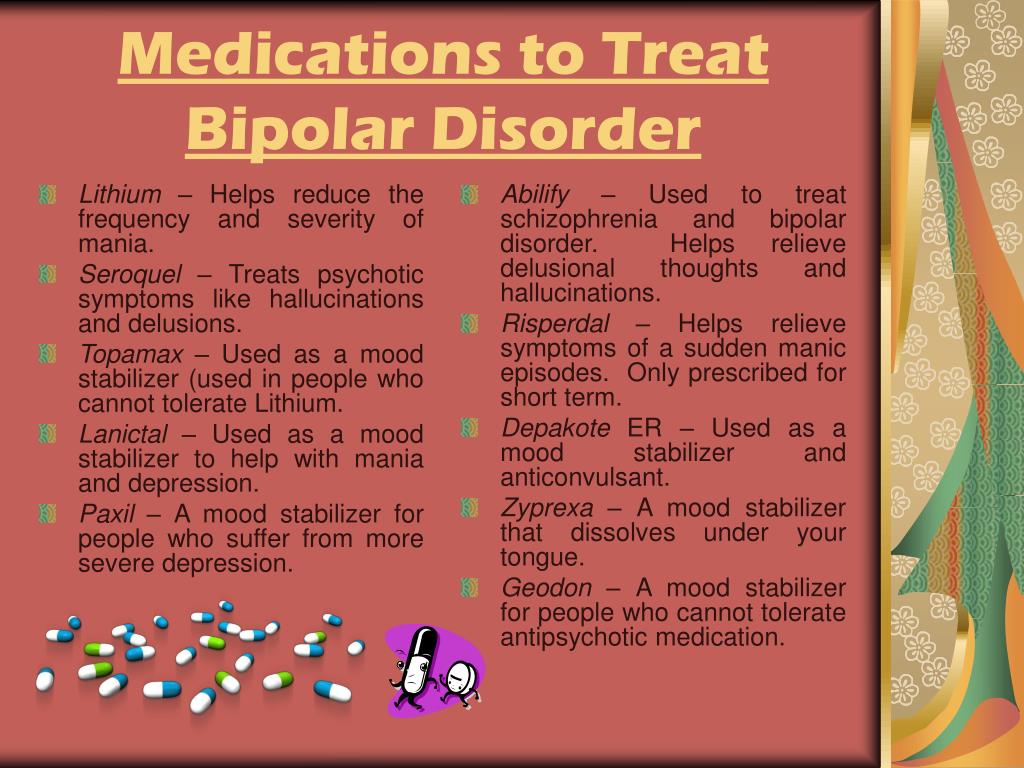

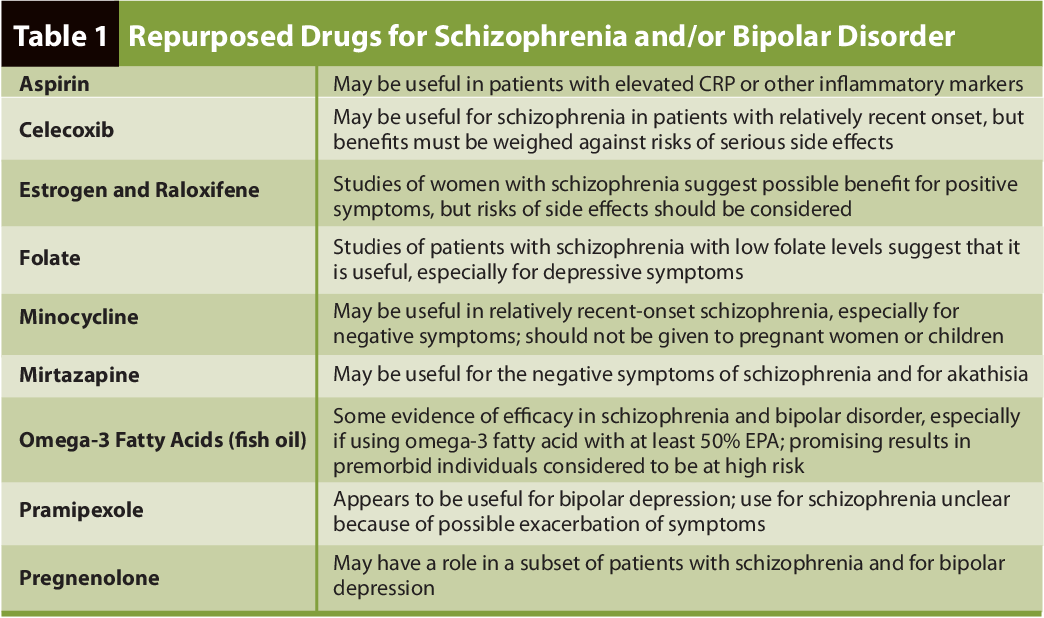

The first-line treatment for bipolar 2 is medication. More specifically, the first-line medications prescribed to manage bipolar 2 are often quetiapine (Seroquel), lithium, and lamotrigine (Lamictal). They are all monotherapies, meaning you take them exclusively. The second-line monotherapy treatments for bipolar 2 disorder are often venlafaxine (Effexor), an SNRI, and fluoxetine (Prozac), an SSRI. Anyone starting a new bipolar 2 medication should be monitored closely for side effects and adverse reactions like agitation or hypomania.

According to a comprehensive 2020 analysis, the best medication for an acute bipolar 2 depressive episode is quetiapine. This first-line treatment is followed by the second-line treatments lithium, lamotrigine, sertraline (Zoloft), venlafaxine, and, as an adjunct, buproprion (Wellbutrin). But all this medication guidance is subject to change as clinical knowledge grows. Bipolar 2 simply hasn’t been researched as extensively as bipolar 1.

The same medications that work for mania also seem to work for hypomania (when it requires treatment), namely the mood stabilizers lithium or divalproex (Depakote) and/or atypical antipsychotics.

Nonpharmacological Treatments for DSM-5 Bipolar 2 Disorder

- Psychoeducation and active monitoring

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

- Interpersonal psychotherapy

- Behavioral activation

- Family-focused therapy (FFT)

- Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies

- Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT)

- Peer interventions such as support groups

Final Thoughts on Bipolar 2

Whether you think of bipolar 2 disorder as part of a bipolar spectrum or continuum, or as its own distinct disorder, it’s a serious mental health condition that can exact a high personal cost if left untreated. But people with any bipolar disorder have an excellent chance of thriving if they embrace these three ingredients as part of their experience:

But people with any bipolar disorder have an excellent chance of thriving if they embrace these three ingredients as part of their experience:

1) Consistent, compassionate, and continuous mental health care

2) Psychoeducation, which can help them monitor their moods and prevent relapse

3) Psychopharmacology (medication)

Finally, it’s important to let go of the idea that you can achieve perfect mastery over your illness. Perfectionism, self-criticism, and shaming beliefs are all associated with bipolar symptoms. You can try to protect yourself from these maladaptive feelings by practicing self-compassion. Stigma has no place in mental health care, whether it comes from the outside, or from within.

Updated Aug 16, 2022, published Jan 27, 2022, 1 min read.

Features 9 cited research articles. 4 comments

Fact-checked Why trust Thriveworks?

Table of contents

What Is Bipolar 2 Disorder?

What Is a Bipolar Disorder?

DSM 5 Bipolar 2 Criteria and Bipolar 2 Symptoms

Bipolar 1 vs Bipolar 2

What Causes Bipolar 2 Disorder?

What Is the Impact of Bipolar 2 Disorder?

How Is Bipolar 2 Diagnosed?

Show all items

What Is the First-Line Treatment for Bipolar 2?

Nonpharmacological Treatments for DSM-5 Bipolar 2 Disorder

Final Thoughts on Bipolar 2

Recent articles

View all

Want to talk to a therapist? We have over 2,000 providers across the US ready to help you in person or online.

Book a session 855-641-1379

- Reviewer

- Author

- 9 sources

- Update history

Medically reviewed by Elizabeth Fiser, PMHNP

Elizabeth Fiser is a Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner (PMHNP) who specializes in a range of areas including alcohol use, addiction, anxiety, depression, trauma and PTSD, women’s issues, and more.

Written by Wistar Murray

Wistar Murray writes about mental health at Thriveworks. She completed her BA at the College of William & Mary and her MFA at Columbia University.

We only use authoritative, trusted, and current sources in our articles. Read our editorial policy to learn more about our efforts to deliver factual, trustworthy information.

Goodwin, G. M., Haddad, P.

M., Ferrier, I. N., Aronson, J. K., Barnes, T., Cipriani, A., Coghill, D. R., Fazel, S., Geddes, J. R., Grunze, H., Holmes, E. A., Howes, O., Hudson, S., Hunt, N., Jones, I., Macmillan, I. C., McAllister-Williams, H., Miklowitz, D. R., Morriss, R., Munafò, M., … Young, A. H. (2016). Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: Revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 30(6), 495–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881116636545

M., Ferrier, I. N., Aronson, J. K., Barnes, T., Cipriani, A., Coghill, D. R., Fazel, S., Geddes, J. R., Grunze, H., Holmes, E. A., Howes, O., Hudson, S., Hunt, N., Jones, I., Macmillan, I. C., McAllister-Williams, H., Miklowitz, D. R., Morriss, R., Munafò, M., … Young, A. H. (2016). Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: Revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 30(6), 495–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881116636545Gitlin, M., & Malhi, G. S. (2020). The existential crisis of bipolar II disorder. International journal of bipolar disorders, 8(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-019-0175-7

Carvalho, A. F., McIntyre, R. S., Dimelis, D., Gonda, X., Berk, M., Nunes-Neto, P.

R., Cha, D. S., Hyphantis, T. N., Angst, J., & Fountoulakis, K. N. (2014). Predominant polarity as a course specifier for bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Journal of affective disorders, 163, 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.035

R., Cha, D. S., Hyphantis, T. N., Angst, J., & Fountoulakis, K. N. (2014). Predominant polarity as a course specifier for bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Journal of affective disorders, 163, 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.035McGuffin, P., Rijsdijk, F., Andrew, M., Sham, P., Katz, R., & Cardno, A. (2003). The heritability of bipolar affective disorder and the genetic relationship to unipolar depression. Archives of general psychiatry, 60(5), 497–502. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.497

Stahl, E. A., Breen, G., Forstner, A. J., McQuillin, A., Ripke, S., Trubetskoy, V., Mattheisen, M., Wang, Y., Coleman, J., Gaspar, H. A., de Leeuw, C. A., Steinberg, S., Pavlides, J., Trzaskowski, M., Byrne, E. M., Pers, T. H., Holmans, P. A., Richards, A. L., Abbott, L.

, Agerbo, E., … Bipolar Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (2019). Genome-wide association study identifies 30 loci associated with bipolar disorder. Nature genetics, 51(5), 793–803. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0397-8

, Agerbo, E., … Bipolar Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (2019). Genome-wide association study identifies 30 loci associated with bipolar disorder. Nature genetics, 51(5), 793–803. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0397-8Koenders, M. A., Giltay, E. J., Spijker, A. T., Hoencamp, E., Spinhoven, P., & Elzinga, B. M. (2014). Stressful life events in bipolar I and II disorder: cause or consequence of mood symptoms?. Journal of affective disorders, 161, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.036

Jones, I., Chandra, P. S., Dazzan, P., & Howard, L. M. (2014). Bipolar disorder, affective psychosis, and schizophrenia in pregnancy and the post-partum period. Lancet (London, England), 384(9956), 1789–1799. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61278-2

Yatham, L.

N., Kennedy, S. H., Parikh, S. V., Schaffer, A., Bond, D. J., Frey, B. N., Sharma, V., Goldstein, B. I., Rej, S., Beaulieu, S., Alda, M., MacQueen, G., Milev, R. V., Ravindran, A., O’Donovan, C., McIntosh, D., Lam, R. W., Vazquez, G., Kapczinski, F., McIntyre, R. S., … Berk, M. (2018). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorders, 20(2), 97–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12609

N., Kennedy, S. H., Parikh, S. V., Schaffer, A., Bond, D. J., Frey, B. N., Sharma, V., Goldstein, B. I., Rej, S., Beaulieu, S., Alda, M., MacQueen, G., Milev, R. V., Ravindran, A., O’Donovan, C., McIntosh, D., Lam, R. W., Vazquez, G., Kapczinski, F., McIntyre, R. S., … Berk, M. (2018). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorders, 20(2), 97–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12609Steardo, L., Jr, Luciano, M., Sampogna, G., Zinno, F., Saviano, P., Staltari, F., Segura Garcia, C., De Fazio, P., & Fiorillo, A. (2020). Efficacy of the interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT) in patients with bipolar disorder: results from a real-world, controlled trial. Annals of general psychiatry, 19, 15. https://doi.org/10.

1186/s12991-020-00266-7

1186/s12991-020-00266-7

We update our content on a regular basis to ensure it reflects the most up-to-date, relevant, and valuable information. When we make a significant change, we summarize the updates and list the date on which they occurred. Read our editorial policy to learn more.

Originally published on May 25, 2017

Author: Lenora KM

Updated on January 27, 2022

Author: Lenora KM

Editor: Wistar Murray

Changes: Content added about the efficacy of medication, which is a front-line, evidence-based treatment for bipolar 2 disorder.

Updated on August 16, 2022

Author: Wistar Murray

Reviewer: Elizabeth Fiser, PMHNP

Changes: Added multiple sections and clarified relationship between bipolar 2 and bipolar 1 disorders.

Clinically/medically reviewed to confirm the accuracy and enhance value.

Clinically/medically reviewed to confirm the accuracy and enhance value.

Are you struggling?

Thriveworks can help.

Browse top-rated therapists near you, and find one who meets your needs. We accept most insurances, and offer weekend and evening sessions.

Book a session 855-641-1379

Rated 4.5 overall from 10,849 Google reviews

Popular articles

Disclaimer

The information on this page is not intended to replace assistance, diagnosis, or treatment from a clinical or medical professional. Readers are urged to seek professional help if they are struggling with a mental health condition or another health concern.

If you’re in a crisis, do not use this site. Please call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or use these resources to get immediate help.

Quick Links

How can we help you?

Bipolar disorder - Symptoms and causes

Overview

Bipolar disorder, formerly called manic depression, is a mental health condition that causes extreme mood swings that include emotional highs (mania or hypomania) and lows (depression).

When you become depressed, you may feel sad or hopeless and lose interest or pleasure in most activities. When your mood shifts to mania or hypomania (less extreme than mania), you may feel euphoric, full of energy or unusually irritable. These mood swings can affect sleep, energy, activity, judgment, behavior and the ability to think clearly.

Episodes of mood swings may occur rarely or multiple times a year. While most people will experience some emotional symptoms between episodes, some may not experience any.

Although bipolar disorder is a lifelong condition, you can manage your mood swings and other symptoms by following a treatment plan. In most cases, bipolar disorder is treated with medications and psychological counseling (psychotherapy).

Bipolar disorder care at Mayo Clinic

Products & Services

- Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Symptoms

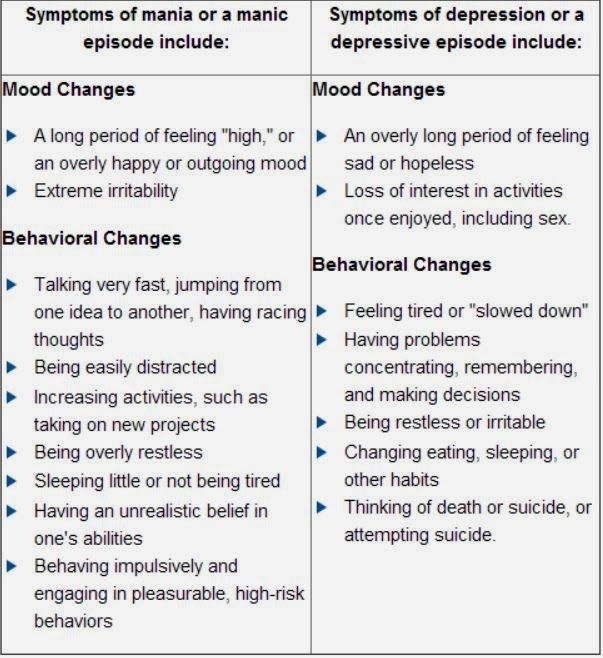

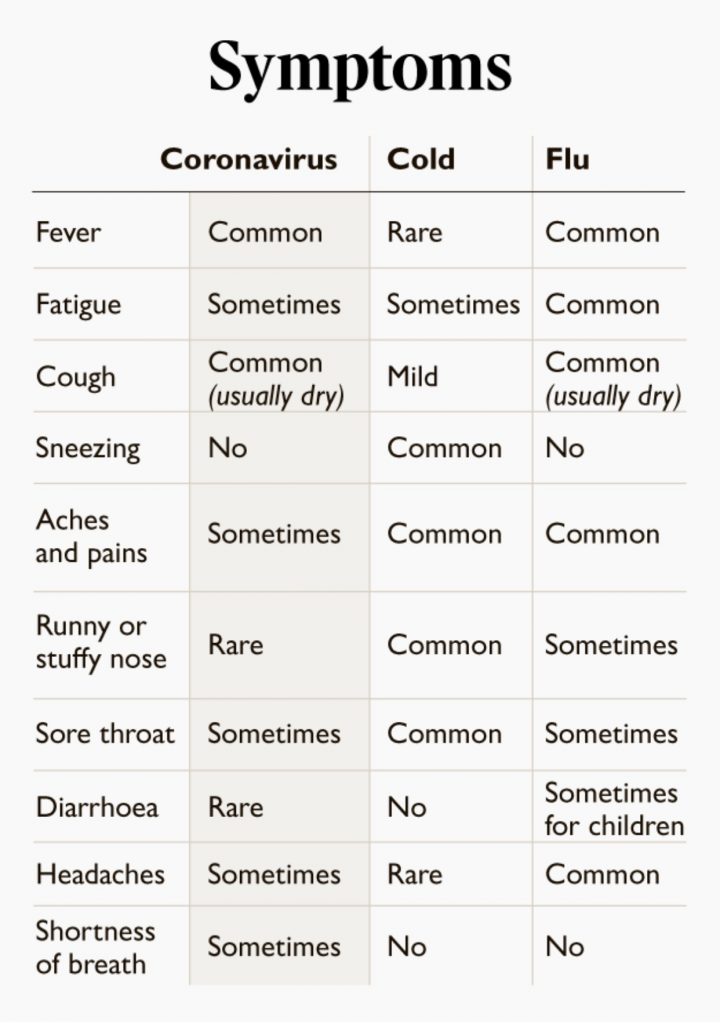

There are several types of bipolar and related disorders. They may include mania or hypomania and depression. Symptoms can cause unpredictable changes in mood and behavior, resulting in significant distress and difficulty in life.

They may include mania or hypomania and depression. Symptoms can cause unpredictable changes in mood and behavior, resulting in significant distress and difficulty in life.

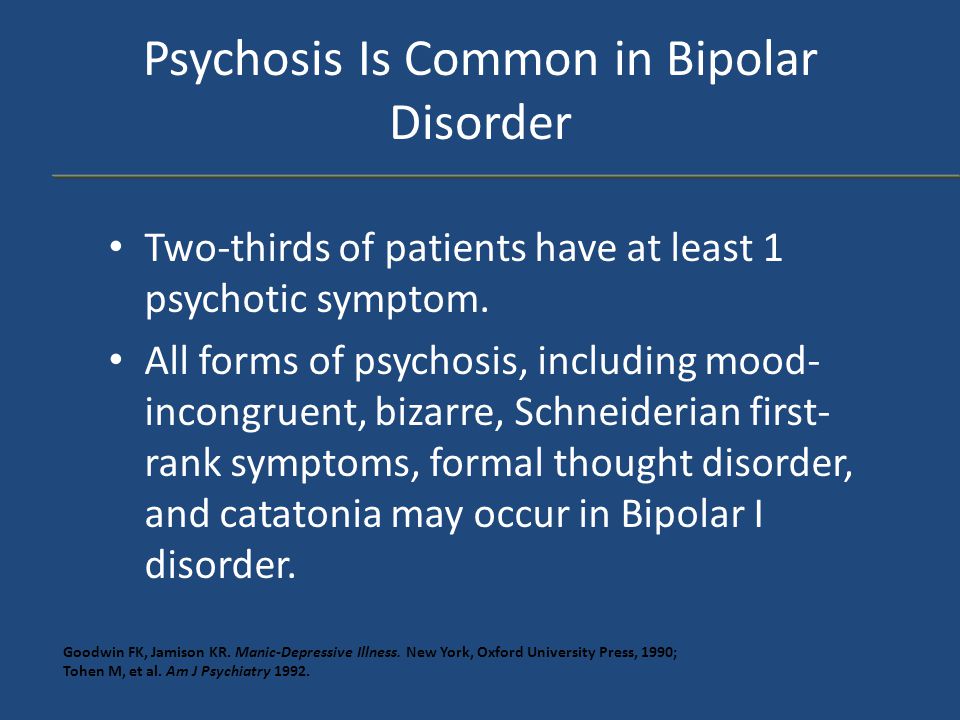

- Bipolar I disorder. You've had at least one manic episode that may be preceded or followed by hypomanic or major depressive episodes. In some cases, mania may trigger a break from reality (psychosis).

- Bipolar II disorder. You've had at least one major depressive episode and at least one hypomanic episode, but you've never had a manic episode.

- Cyclothymic disorder. You've had at least two years — or one year in children and teenagers — of many periods of hypomania symptoms and periods of depressive symptoms (though less severe than major depression).

- Other types. These include, for example, bipolar and related disorders induced by certain drugs or alcohol or due to a medical condition, such as Cushing's disease, multiple sclerosis or stroke.

Bipolar II disorder is not a milder form of bipolar I disorder, but a separate diagnosis. While the manic episodes of bipolar I disorder can be severe and dangerous, individuals with bipolar II disorder can be depressed for longer periods, which can cause significant impairment.

Although bipolar disorder can occur at any age, typically it's diagnosed in the teenage years or early 20s. Symptoms can vary from person to person, and symptoms may vary over time.

Mania and hypomania

Mania and hypomania are two distinct types of episodes, but they have the same symptoms. Mania is more severe than hypomania and causes more noticeable problems at work, school and social activities, as well as relationship difficulties. Mania may also trigger a break from reality (psychosis) and require hospitalization.

Both a manic and a hypomanic episode include three or more of these symptoms:

- Abnormally upbeat, jumpy or wired

- Increased activity, energy or agitation

- Exaggerated sense of well-being and self-confidence (euphoria)

- Decreased need for sleep

- Unusual talkativeness

- Racing thoughts

- Distractibility

- Poor decision-making — for example, going on buying sprees, taking sexual risks or making foolish investments

Major depressive episode

A major depressive episode includes symptoms that are severe enough to cause noticeable difficulty in day-to-day activities, such as work, school, social activities or relationships. An episode includes five or more of these symptoms:

An episode includes five or more of these symptoms:

- Depressed mood, such as feeling sad, empty, hopeless or tearful (in children and teens, depressed mood can appear as irritability)

- Marked loss of interest or feeling no pleasure in all — or almost all — activities

- Significant weight loss when not dieting, weight gain, or decrease or increase in appetite (in children, failure to gain weight as expected can be a sign of depression)

- Either insomnia or sleeping too much

- Either restlessness or slowed behavior

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt

- Decreased ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness

- Thinking about, planning or attempting suicide

Other features of bipolar disorder

Signs and symptoms of bipolar I and bipolar II disorders may include other features, such as anxious distress, melancholy, psychosis or others. The timing of symptoms may include diagnostic labels such as mixed or rapid cycling. In addition, bipolar symptoms may occur during pregnancy or change with the seasons.

The timing of symptoms may include diagnostic labels such as mixed or rapid cycling. In addition, bipolar symptoms may occur during pregnancy or change with the seasons.

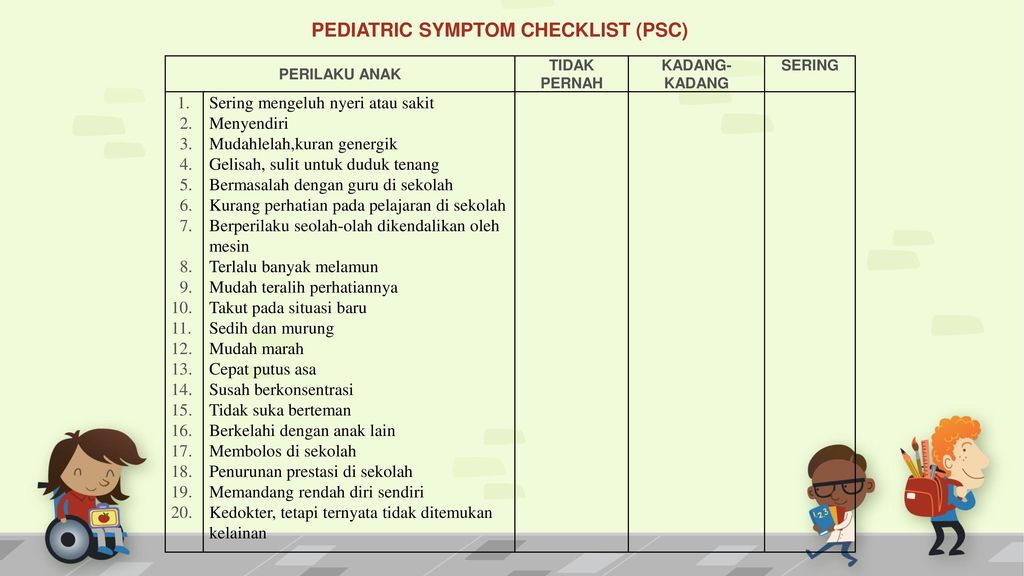

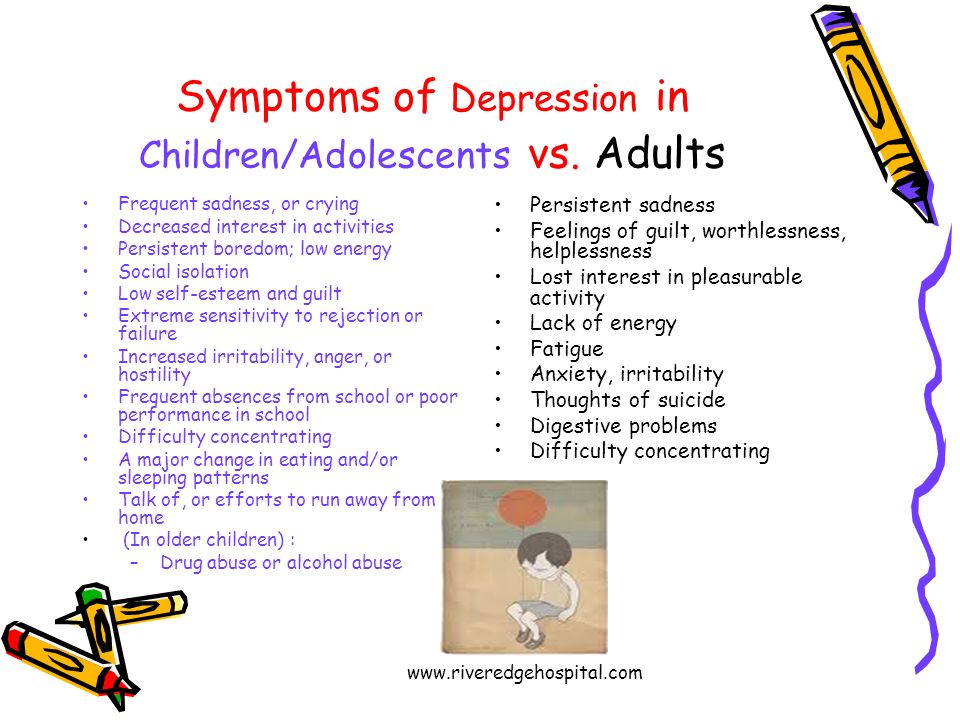

Symptoms in children and teens

Symptoms of bipolar disorder can be difficult to identify in children and teens. It's often hard to tell whether these are normal ups and downs, the results of stress or trauma, or signs of a mental health problem other than bipolar disorder.

Children and teens may have distinct major depressive or manic or hypomanic episodes, but the pattern can vary from that of adults with bipolar disorder. And moods can rapidly shift during episodes. Some children may have periods without mood symptoms between episodes.

The most prominent signs of bipolar disorder in children and teenagers may include severe mood swings that are different from their usual mood swings.

When to see a doctor

Despite the mood extremes, people with bipolar disorder often don't recognize how much their emotional instability disrupts their lives and the lives of their loved ones and don't get the treatment they need.

And if you're like some people with bipolar disorder, you may enjoy the feelings of euphoria and cycles of being more productive. However, this euphoria is always followed by an emotional crash that can leave you depressed, worn out — and perhaps in financial, legal or relationship trouble.

If you have any symptoms of depression or mania, see your doctor or mental health professional. Bipolar disorder doesn't get better on its own. Getting treatment from a mental health professional with experience in bipolar disorder can help you get your symptoms under control.

When to get emergency help

Suicidal thoughts and behavior are common among people with bipolar disorder. If you have thoughts of hurting yourself, call 911 or your local emergency number immediately, go to an emergency room, or confide in a trusted relative or friend. Or call a suicide hotline number — in the United States, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (1-800-273-8255).

If you have a loved one who is in danger of suicide or has made a suicide attempt, make sure someone stays with that person. Call 911 or your local emergency number immediately. Or, if you think you can do so safely, take the person to the nearest hospital emergency room.

Request an Appointment at Mayo Clinic

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free, and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips and current health topics, like COVID-19, plus expertise on managing health.

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which

information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with

other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could

include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected

health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health

information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of

privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on

the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on

the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Causes

The exact cause of bipolar disorder is unknown, but several factors may be involved, such as:

- Biological differences. People with bipolar disorder appear to have physical changes in their brains. The significance of these changes is still uncertain but may eventually help pinpoint causes.

- Genetics. Bipolar disorder is more common in people who have a first-degree relative, such as a sibling or parent, with the condition. Researchers are trying to find genes that may be involved in causing bipolar disorder.

Risk factors

Factors that may increase the risk of developing bipolar disorder or act as a trigger for the first episode include:

- Having a first-degree relative, such as a parent or sibling, with bipolar disorder

- Periods of high stress, such as the death of a loved one or other traumatic event

- Drug or alcohol abuse

Complications

Left untreated, bipolar disorder can result in serious problems that affect every area of your life, such as:

- Problems related to drug and alcohol use

- Suicide or suicide attempts

- Legal or financial problems

- Damaged relationships

- Poor work or school performance

Co-occurring conditions

If you have bipolar disorder, you may also have another health condition that needs to be treated along with bipolar disorder. Some conditions can worsen bipolar disorder symptoms or make treatment less successful. Examples include:

Some conditions can worsen bipolar disorder symptoms or make treatment less successful. Examples include:

- Anxiety disorders

- Eating disorders

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Alcohol or drug problems

- Physical health problems, such as heart disease, thyroid problems, headaches or obesity

More Information

- Bipolar disorder care at Mayo Clinic

- Bipolar disorder and alcoholism: Are they related?

Prevention

There's no sure way to prevent bipolar disorder. However, getting treatment at the earliest sign of a mental health disorder can help prevent bipolar disorder or other mental health conditions from worsening.

If you've been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, some strategies can help prevent minor symptoms from becoming full-blown episodes of mania or depression:

- Pay attention to warning signs. Addressing symptoms early on can prevent episodes from getting worse.

You may have identified a pattern to your bipolar episodes and what triggers them. Call your doctor if you feel you're falling into an episode of depression or mania. Involve family members or friends in watching for warning signs.

You may have identified a pattern to your bipolar episodes and what triggers them. Call your doctor if you feel you're falling into an episode of depression or mania. Involve family members or friends in watching for warning signs. - Avoid drugs and alcohol. Using alcohol or recreational drugs can worsen your symptoms and make them more likely to come back.

- Take your medications exactly as directed. You may be tempted to stop treatment — but don't. Stopping your medication or reducing your dose on your own may cause withdrawal effects or your symptoms may worsen or return.

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Related

Associated Procedures

Products & Services

Differential diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents

G.A. Carlson 1

The differential diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder (BAD) in children and adolescents is a complex problem. The diagnosis of mania in BAD type I cannot be made without long-term follow-up. This disease leads to disability, but it must be distinguished from other similar pathologies. Having a family history of bipolar disorder may increase the risk of certain symptoms and behaviors that are characteristic of the onset of the disease, but a diagnosis should not be made on the basis of the history alone. Until there are biomarkers to confirm the diagnosis and targeted treatments for the disease, it makes sense to make a diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents only temporarily, with the expectation that they will need to be re-examined in the future.

The diagnosis of mania in BAD type I cannot be made without long-term follow-up. This disease leads to disability, but it must be distinguished from other similar pathologies. Having a family history of bipolar disorder may increase the risk of certain symptoms and behaviors that are characteristic of the onset of the disease, but a diagnosis should not be made on the basis of the history alone. Until there are biomarkers to confirm the diagnosis and targeted treatments for the disease, it makes sense to make a diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents only temporarily, with the expectation that they will need to be re-examined in the future.

There are at least five challenges to the differential diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents, which are discussed below.

- How to determine the subtype of bipolar disorder (differential diagnosis between mania and depression, between type I bipolar disorder and an unspecified bipolar disorder)?

- The age of the child and the onset of the disease.

- Should only those episodes be considered a disease when mood changes and impaired functioning are clearly visible in comparison with the premorbid background, or should anger outbursts and severe irritability be considered, for example, already as a change in mood?

- Who should provide information on symptoms of illness during mania, and when should the data be collected after an attack or during the peak of the illness, when it is easier to study?

- Influence of family history on diagnosis.

By no means all children and adolescents can clearly tell about their lives, they do not always understand such abstract concepts as euphoria or a leap of ideas. Parents may underestimate or misinterpret the experiences of their children. Children spend most of their time at school, therefore, if a child is in a certain mood for most of the day every day, the teacher can notice changes in his behavior and mood, regardless of whether he / she has an idea of mania or depression and other diseases.

This article will focus mostly on mania and the differences between children and adolescents. An attempt will be made to describe a comprehensive approach to diagnosing a disease and to discuss the impact of different ways of providing information on making a diagnosis.

Post-pubertal mania

Jeffrey was 14 years old when he first came to the attention of doctors. He is a sociable, energetic, purposeful, creative young man, at the same time he has many hobbies that he does not give up halfway, he approaches all his activities diligently and responsibly. However, in recent months, the guy has problems with concentration; at night he began to swim unannounced in a neighbor's pool, tried to reach President Bush in order to advise on further tactics for the war in Iraq, became short-tempered and implacable with his parents when they tried to put him to sleep. Following this period, which lasted several weeks, Geoffrey became physically weak, exhausted, lost interest in socializing with friends, in hobbies, practically stopped eating and felt extremely depressed. Upon further questioning, it was possible to find out other symptoms indicating mania without signs of depressive episodes in history. The task of the doctor was to find out what it is: "adolescent behavior" or psychopathology. The difficulty was that two weeks before the change in behavior, Jeffrey had suffered a head injury in football training without losing consciousness, and this may have affected the development of painful symptoms. Although it is clear that Geoffrey suffered a classic symptomatic episode of mania, some questions still need to be clarified.

Upon further questioning, it was possible to find out other symptoms indicating mania without signs of depressive episodes in history. The task of the doctor was to find out what it is: "adolescent behavior" or psychopathology. The difficulty was that two weeks before the change in behavior, Jeffrey had suffered a head injury in football training without losing consciousness, and this may have affected the development of painful symptoms. Although it is clear that Geoffrey suffered a classic symptomatic episode of mania, some questions still need to be clarified.

- How big is the contribution of Jeffrey's initially hyperthymic character traits to further behavior change [2]? A person with a hyperthymic character is usually cheerful, ebullient, talkative, playful, too optimistic, relaxed, carefree, energetic, full of short-term plans, often changes his circle of interests, interferes in everything, becoming annoying. All this applied to Geoffrey. Has he crossed the line of hypomania or even a manic episode? If he had been a quiet, modest person by nature before the excitement began, the issue would have been easily resolved in a positive direction.

At the same time, such violations and subsequent depression do not fit only into the framework of character traits.

At the same time, such violations and subsequent depression do not fit only into the framework of character traits. - Did the head injury matter? There is evidence of a link between brain injury and the onset of mania [3]. There is also a condition called "personality change after traumatic brain injury", which is used to describe patients with disinhibited behavior [4]. In early versions of the DSM, this was the term "organic affective disorder".

- Is there any evidence of Jeffrey's substance abuse? In adolescents, a first episode of mood disturbance raises questions about the presence of alcohol or drug dependence [5]. So, with the abuse of marijuana, alcohol and other drugs, they may develop psychotic or affective symptoms. Although a positive test for toxic substances in the body helps to confirm the fact of drug use, a negative result does not at all indicate the absence of addiction. Moreover, manic symptoms may continue for weeks after the patient has stopped taking the substances.

Sometimes it is difficult to figure out how big the role of drug use in the occurrence of mood changes is, whether it brings the onset of the disease closer and whether it prolongs its course, because it could proceed faster, or whether this is completely insignificant [6].

Sometimes it is difficult to figure out how big the role of drug use in the occurrence of mood changes is, whether it brings the onset of the disease closer and whether it prolongs its course, because it could proceed faster, or whether this is completely insignificant [6].

11-27% of adolescents admitted to hospital for their first psychotic episode were previously diagnosed with type I bipolar disorder [7]. However, during the first episode, it is extremely difficult to accurately determine the diagnosis due to the confusion and variability of symptoms over time. Example: Dennis is 16 years old, he has not slept for three days, he has a feeling that he can rule the world; the boy wrote notes in which he argued that all objects around had their own purpose and connection with each other, including the German swastika, the Egyptian pyramids and the dove of peace. He experienced physical arousal, was verbose, paranoid thoughts grew that the psychiatrist wanted to harm him. Over the next 6 months, on antipsychotic and lithium therapy, the affective symptoms subsided, but a sense of thought transmission and related thinking disorders appeared, which were persistent. After 10 years, she was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder due to chronic thought disorder and persistent psychotic symptoms. The medication improved the patient's mood but did not affect the negative symptoms.

Over the next 6 months, on antipsychotic and lithium therapy, the affective symptoms subsided, but a sense of thought transmission and related thinking disorders appeared, which were persistent. After 10 years, she was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder due to chronic thought disorder and persistent psychotic symptoms. The medication improved the patient's mood but did not affect the negative symptoms.

Despite the fact that almost 70% of patients with a first manic psychotic episode are diagnosed with bipolar disorder (sometimes as an intermediate) within 10 years after the onset of the disease, in this case, the presence of symptoms of the first rank according to Schneider, as well as premorbid decline in social functioning [8]. Harbingers of an unfavorable prognosis are also considered to be depressive manifestations, childhood psychopathology, and early onset of the disease [9].

Mania in children

The diagnosis of mania before the age of 10 years is much more controversial than in adolescents [10]. In order to apply the criteria for bipolar disorder to children, the DSM-IV-TR has updated the list of symptoms of mania to include the most common manifestations of the disease in young children. The unresolved question remains whether these children grow up healthy until the first episodes of depression or mania (as in the case of Jeffrey: acute onset of mania, isolated episodes, no comorbid pathology), or whether these are continuous mood swings against the background of depression - close to those observed in patients enrolled in the Bipolar Disorder Systematic Care Program (STEP-BD) study [11]? Or perhaps their prognosis is completely different - patients grow up and do not experience any episodes of altered mood in the future [12]?

In order to apply the criteria for bipolar disorder to children, the DSM-IV-TR has updated the list of symptoms of mania to include the most common manifestations of the disease in young children. The unresolved question remains whether these children grow up healthy until the first episodes of depression or mania (as in the case of Jeffrey: acute onset of mania, isolated episodes, no comorbid pathology), or whether these are continuous mood swings against the background of depression - close to those observed in patients enrolled in the Bipolar Disorder Systematic Care Program (STEP-BD) study [11]? Or perhaps their prognosis is completely different - patients grow up and do not experience any episodes of altered mood in the future [12]?

The insidiousness and complexity of diagnosing early forms of bipolar disorder lies in the different interpretation of the criteria. In the "classic" cases of mania, there are practically no contradictions: the onset of the disease is clearly monitored, and manic symptoms, consistently manifesting themselves, do not allow mania to be confused with another psychopathology. In the course of the disease in a less “classical way”, much more discrepancies appear [13]. The criteria may be reliable for a certain category of patients, but do not guarantee accuracy and do not apply to other groups. According to the DSM-IV-TR, a manic episode is defined as a distinct time span of the presence of a characteristic set of symptoms. Unfortunately, there is no agreement in understanding the boundaries of this time period [14]. Therefore, the criteria for mania will be subject to some changes in the next version of the DSM-5 (see www.dsm5.org). The document states that "doctors have not been able to agree on what is still considered an episode of mania, especially a lot of controversy in the literature in the field of child psychiatry."

In the course of the disease in a less “classical way”, much more discrepancies appear [13]. The criteria may be reliable for a certain category of patients, but do not guarantee accuracy and do not apply to other groups. According to the DSM-IV-TR, a manic episode is defined as a distinct time span of the presence of a characteristic set of symptoms. Unfortunately, there is no agreement in understanding the boundaries of this time period [14]. Therefore, the criteria for mania will be subject to some changes in the next version of the DSM-5 (see www.dsm5.org). The document states that "doctors have not been able to agree on what is still considered an episode of mania, especially a lot of controversy in the literature in the field of child psychiatry."

According to the Mood Disorders Research Group, the language in the DSM-IV regarding the criteria for mania and hypomania has only led to confusion. Therefore, the goal of the DSM change proposal would be to provide more clarity to ensure more accurate, consistent diagnosis. At the same time, it is necessary to rely on the experience of previous versions of the DSM, taking into account the modern dynamic characteristics of the disease. Criterion A would be: Unusual and persistent high spirits, expansiveness, irritability, unaccustomed and persistent energy, elation, lasting at least 1 week and lasting almost daily for most of the day (duration is not important if hospitalization is necessary) for a certain period of time.

At the same time, it is necessary to rely on the experience of previous versions of the DSM, taking into account the modern dynamic characteristics of the disease. Criterion A would be: Unusual and persistent high spirits, expansiveness, irritability, unaccustomed and persistent energy, elation, lasting at least 1 week and lasting almost daily for most of the day (duration is not important if hospitalization is necessary) for a certain period of time.

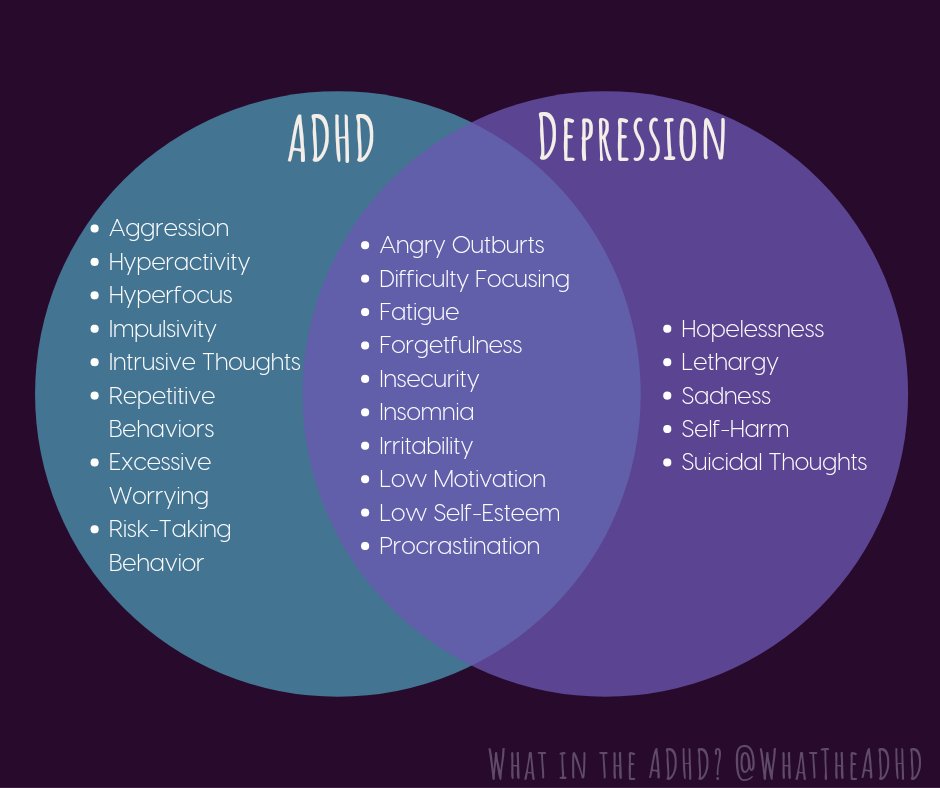

An accurate understanding of the symptoms is essential when discussing the differential diagnosis of mania. While it is recognized that depressive symptoms may occur independently of a depressive episode or clinical depression, manic symptoms have hardly been assessed in this way. Previously published results of a study in 1988 [15], as well as a number of other studies, confirmed that the symptoms of mania occur much more often than the manic episode itself, and cause serious damage to health. However, these symptoms are nonspecific and occur in various pathologies [16, 17]. Without knowing exactly whether an episode occurred or not (the time of onset and end of changes in the patient's "habitual behavior"), without data on early childhood, about what this "habitual behavior" was, it is extremely difficult to distinguish mania from other childhood illnesses that occur with irritability and agitation. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a disease that is most often confused with mania in children. A significant part of the symptoms are the same: in both conditions there are distractibility, impulsiveness, hyperactivity, accelerated and excessive speech [19]. Yet children with mania have more symptomatic symptoms than those with uncomplicated ADHD. In such children, as a rule, the violations are deeper; another pathology (comorbid conditions) is necessarily found according to the criteria [20, 21]. Curiously, when comparing children with symptoms of mania and children with ADHD, complicated in both cases by a similar comorbid pathology, all differences disappear [22, 23].

Without knowing exactly whether an episode occurred or not (the time of onset and end of changes in the patient's "habitual behavior"), without data on early childhood, about what this "habitual behavior" was, it is extremely difficult to distinguish mania from other childhood illnesses that occur with irritability and agitation. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a disease that is most often confused with mania in children. A significant part of the symptoms are the same: in both conditions there are distractibility, impulsiveness, hyperactivity, accelerated and excessive speech [19]. Yet children with mania have more symptomatic symptoms than those with uncomplicated ADHD. In such children, as a rule, the violations are deeper; another pathology (comorbid conditions) is necessarily found according to the criteria [20, 21]. Curiously, when comparing children with symptoms of mania and children with ADHD, complicated in both cases by a similar comorbid pathology, all differences disappear [22, 23]. A diagnostic question arises: either children with symptoms of mania suffer from bipolar disorder in combination with ADHD, or ADHD occurs against a background of increased emotional or protest isolation.

A diagnostic question arises: either children with symptoms of mania suffer from bipolar disorder in combination with ADHD, or ADHD occurs against a background of increased emotional or protest isolation.

Emotional/protest behavior in ADHD is considered among the "associated symptoms" in the DSM-III/IV. The DSM-IV-TR states that the emotional component of the illness includes low frustration tolerance, irritability, temper tantrums, mood swings, dysphoria, and low self-esteem. All symptoms fit within the framework of mood. The emotional component is present in both manifestations of ADHD - impaired attention and hyperactivity. The symptoms of ADHD caused by impaired attention may be initially associated with a defect in the sphere of regulation and control, while the symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity may arise from disturbances in the emotional sphere [24]. It is only obvious that in children with both bipolar disorder and ADHD complicated by emotional disorders, disorders are much more clearly manifested, which was verified by comparing them with cases of ADHD without complications in the course of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies [20, 25].

ADHD and bipolar disorder often coexist. A recently published study titled Longitudinal Mania Symptom Study explores the issue of ADHD and bipolar disorder in great detail [16, 20]. Researchers compared children aged 6 to 12 years (n = 621) whose parents tested positive for manic symptoms on the General Behavior Questionnaire with children whose parents did not score enough (n = 86) [26]. Of the total number of children (n = 707), the majority (59.5%) had ADHD, 6.4% had a bipolar disorder without ADHD, 16.5% had both, and 17.5% were healthy. The spectrum of bipolar disorders evenly consisted of cases of type I bipolar disorder and unspecified bipolar disorder, there was also a small number of type II bipolar disorder. As in previous studies [1, 15], children with symptoms of mania were not found to have bipolar spectrum disorders. Of 162 children with bipolar spectrum disorders, the majority (72.2%) also had ADHD. According to the results of a survey of parents, it turned out that in the presence of a combination of these diseases, the symptoms are richer than in the case of each of the pathologies separately. The diagnosis was made according to the children's diagnostic scale for affective disorders and schizophrenia [27]. Although the authors did not specify, some believe that the data were based more on parental responses, as teachers often disagreed with the results [20]. Yet much attention has been paid to distinguishing chronic symptoms from acute or intermittent ones. It is this approach that helps in differentiating mania and ADHD from the joint course of these diseases. In addition to taking an anamnesis, which may include episodes, a scrupulous examination of all overlapping symptoms is necessary. The symptoms of mania and ADHD, mixed together, can give the following picture:

The diagnosis was made according to the children's diagnostic scale for affective disorders and schizophrenia [27]. Although the authors did not specify, some believe that the data were based more on parental responses, as teachers often disagreed with the results [20]. Yet much attention has been paid to distinguishing chronic symptoms from acute or intermittent ones. It is this approach that helps in differentiating mania and ADHD from the joint course of these diseases. In addition to taking an anamnesis, which may include episodes, a scrupulous examination of all overlapping symptoms is necessary. The symptoms of mania and ADHD, mixed together, can give the following picture:

- goofy, disinhibited behavior in a child with ADHD trying to be funny without considering the circumstances, or is it just high spirits;

- impulsiveness or desire to enjoy without considering the consequences;

- refusal to go to bed on time or simply reduced need for sleep;

- worsening of subtle symptoms of ADHD due to increased workload in primary or secondary school, or the onset of mood disturbances;

- exacerbation of ADHD symptoms, including greater protest, irascibility, stupid behavior, as part of poor relationships within the family and school circles, among peers;

- intrusive, slurred, or bizarre speech in children with ADHD or autism spectrum disease speech problems may resemble the thought jitters or thought disturbances of mania;

- "hallucinations" in highly anxious children, or symptoms incongruent to affect in mania.

Children with RSA due to impaired emotional control can be confused with those with mania [28]. And it's not just their impulsiveness and excessive activity. Speech disorders may also look like thought disorders, especially for a clinician who is not experienced in differential diagnosis [29]. As in the case of ADHD, a good history can help distinguish which symptoms are chronic and which first appeared as part of an altered state. Interestingly, children with autism and bipolar disorder (including the most classic episodic variants of bipolar disorder) have always been considered together [30], while children with a general developmental disorder have almost always been overlooked in the studies.

Dysregulation of mood

At the age of 11, Linda was brought to the doctor by her parents due to mood swings, namely frequent outbursts of anger [13].

From early childhood she suffered from ADHD, the symptoms of which were almost continuous during treatment with stimulants. By the 5th grade, the girl became irritable, disobedient, spiteful towards her parents, ignoring their concern about her school grades. There was a feeling of grandiosity with ideas about the uselessness of study. Linda visited porn sites and stayed up late in front of the computer supposedly with online friends, lagged behind in her studies and shunned her peers. Temper at school did not manifest itself, but the symptoms of ADHD were evident. Parents during the history taking confirmed the presence of symptoms resembling mania. Linda herself complained of dysphoria, irritability, trouble concentrating, low self-esteem, and occasional suicidal thoughts. Among other things, there were serious quarrels at home, but without violence. Linda's differential diagnosis based on DSM-IV criteria would include ADHD and incipient oppositional conduct disorder, major depressive disorder, secondary adjustment disorder with impaired social, academic and home connections, and an episode of mixed mania.

By the 5th grade, the girl became irritable, disobedient, spiteful towards her parents, ignoring their concern about her school grades. There was a feeling of grandiosity with ideas about the uselessness of study. Linda visited porn sites and stayed up late in front of the computer supposedly with online friends, lagged behind in her studies and shunned her peers. Temper at school did not manifest itself, but the symptoms of ADHD were evident. Parents during the history taking confirmed the presence of symptoms resembling mania. Linda herself complained of dysphoria, irritability, trouble concentrating, low self-esteem, and occasional suicidal thoughts. Among other things, there were serious quarrels at home, but without violence. Linda's differential diagnosis based on DSM-IV criteria would include ADHD and incipient oppositional conduct disorder, major depressive disorder, secondary adjustment disorder with impaired social, academic and home connections, and an episode of mixed mania.

Mood disturbances/lability are present in many cases as an important component of a number of conditions [31]. Non-professionals often use the term "bipolar" to describe mood swings, that is, sudden changes that are inexplicable to an outsider. We are talking about the sudden onset of a bad mood as a cause of irritability. When experiencing a manic episode, both adults and children are often irritable. However, the question remains: do extremely irascible children suffer from mania, or is it a character (irritability as a trait), which casts doubt on the diagnosis of such conditions as depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, etc., in which the symptom of irritability plays a significant role [32].

Depressive and anxiety disorders

Irritability as a symptom is of course important not only in mania, but also in depression (equally in major depression and dysthymia) and anxiety disorders (including post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, avoidance and generalized anxiety disorder). As with ADHD, the question "is it depression or anxiety?" not worth it, rather a combination of both. Of particular difficulty is how to distinguish between mixed mania, or "rapid" cycles, and agitated depression. Some view agitated depression as a bipolar disorder [33]. Longitudinal pro- and retrospective trials show that the predominantly depressive course of the disease from the bipolar spectrum is more likely to become chronic and more difficult to treat than manic [9, 34, 35]. The question that arises in the course of a prospective study of a group of children is this: how many children "outgrow" mania and go into depression or even remission [12, 36]?

As with ADHD, the question "is it depression or anxiety?" not worth it, rather a combination of both. Of particular difficulty is how to distinguish between mixed mania, or "rapid" cycles, and agitated depression. Some view agitated depression as a bipolar disorder [33]. Longitudinal pro- and retrospective trials show that the predominantly depressive course of the disease from the bipolar spectrum is more likely to become chronic and more difficult to treat than manic [9, 34, 35]. The question that arises in the course of a prospective study of a group of children is this: how many children "outgrow" mania and go into depression or even remission [12, 36]?

Irritability and hyperactivity are also inherent in anxiety. In adults and adolescents, bipolar disorder is often accompanied by painful anxiety. In adults, the presence of anxiety symptoms reduces the likelihood of recovery from bipolar depression, prolongs the course of the disease, and increases the likelihood of a relapse [37].

In children, anxiety disorder often precedes the onset of mania, in which case the manic episode would be considered a comorbid disorder. If anxiety has not previously arisen, it is quite acceptable to consider it within the framework of a manic episode, not considering it as a comorbid disorder [38]. In children and adolescents, anxiety is most often associated with type II bipolar disorder. These patients often have parallel longer and more severe episodes of depression, and a richer family history of depression than children and adolescents without anxiety symptoms as a comorbid pathology [38].

Mood regulation disorder with disruptive features

Leibenluft and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Intramural Program on Mood Disorders in an attempt to better understand the similarities and differences between chronic, severe irritability and It was proposed to single out such a condition as “severe mood regulation disorder” (SMDD) as a more classic, episodic course, bipolar disorder [32]. This condition is characterized by persistent irritability with frequent outbursts of anger and is more commonly referred to as mania, schizophrenia or schizophrenia spectrum disorder, general developmental disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, organic or neurological disorder. In a sample of 146 children, 75% had ADHD and oppositional disorder as a comorbid disorder, and more than half (58%) had an episode of anxiety disorder at least once in their lives. Although prospective studies have not been conducted in children with CCHD, extrapolating data from other studies [39-41], it can be assumed that depression is the basis of such behavioral disorders. Thus, the DSM-5 Mood Disorders Study Group is using data from these studies to add HDD to the new guidelines under mood disorders. This condition has been termed Mood Disorder with Disruptive Traits (MDD) (see www.dsm5.org).

This condition is characterized by persistent irritability with frequent outbursts of anger and is more commonly referred to as mania, schizophrenia or schizophrenia spectrum disorder, general developmental disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, organic or neurological disorder. In a sample of 146 children, 75% had ADHD and oppositional disorder as a comorbid disorder, and more than half (58%) had an episode of anxiety disorder at least once in their lives. Although prospective studies have not been conducted in children with CCHD, extrapolating data from other studies [39-41], it can be assumed that depression is the basis of such behavioral disorders. Thus, the DSM-5 Mood Disorders Study Group is using data from these studies to add HDD to the new guidelines under mood disorders. This condition has been termed Mood Disorder with Disruptive Traits (MDD) (see www.dsm5.org).

In the absence of an episodic course, differentiation of RRND from mania should not be difficult. In addition, the onset of the disease most often occurs between the ages of 6 and 10, which makes it possible to protect temperamental preschoolers from making a “serious diagnosis” and at the same time regard the disorder as childish. It is the chronic course of the disease (that is, the symptoms last at least 1 year) that does not allow children to be diagnosed with RRND. These are the children who respond to acute stress and could be diagnosed with an adjustment disorder with behavioral or mood disturbances. The diagnosis of RRND, when correctly made, usually means a serious condition and loss or decrease in working capacity [31].

In addition, the onset of the disease most often occurs between the ages of 6 and 10, which makes it possible to protect temperamental preschoolers from making a “serious diagnosis” and at the same time regard the disorder as childish. It is the chronic course of the disease (that is, the symptoms last at least 1 year) that does not allow children to be diagnosed with RRND. These are the children who respond to acute stress and could be diagnosed with an adjustment disorder with behavioral or mood disturbances. The diagnosis of RRND, when correctly made, usually means a serious condition and loss or decrease in working capacity [31].

The main diagnostic difficulty in the case of RRND is the fact that irritability and irascibility are nonspecific signs [42]. Children who constantly show temper tantrums (whether chronically irritable or not) end up in emergency hospitals, psychiatric and other supervised and special educational institutions. The need for diagnosis is dictated by the need to count such patients, provide them with proper treatment and inclusion in the insurance list. Typically, these short-tempered children fall into the category of oppositional disorder or conduct disorder, and both categories are not included in the insurance list of illnesses, as they are considered within the framework of "family" or "social" problems. Due to the lack of a reliable and accurate coding for such outbursts of anger, doctors are forced to assign them the category BAD, which in turn prevents a serious understanding of the nature of these outbursts [43].

Typically, these short-tempered children fall into the category of oppositional disorder or conduct disorder, and both categories are not included in the insurance list of illnesses, as they are considered within the framework of "family" or "social" problems. Due to the lack of a reliable and accurate coding for such outbursts of anger, doctors are forced to assign them the category BAD, which in turn prevents a serious understanding of the nature of these outbursts [43].

The question arises whether temper tantrums are some kind or more severe manifestation of mood swings (tantrums) in patients of early childhood [44, 45]? Interestingly, both states are generally similar, differing only in duration (20 and 5 minutes, respectively), as well as in more rude behavior (children can kick, hit, throw, spit) and the degree of harm that a child in a tantrum state can cause, due to that these children are older (from 7 to 17 years). There are no data describing the features of outbursts of anger in various pathologies, that is, the anger that occurs during a panic attack is outwardly similar to that in a manic episode, oppositional disorder, depression, etc. [46]. Many clinicians worry that this diagnosis will be misused to the same extent as the diagnosis of bipolar disorder [43]. Mistakes can be avoided by correctly following the algorithm, for example, if you take outbursts of anger as a key and distinguishing feature for a number of conditions where they are present, just as types of catatonia allow you to distinguish between a number of pathologies. For example, the diagnosis "ADHD with outbursts of anger" - the key ones in this case, could be regarded as an independent diagnosis of "outbursts of anger", which would allow for more complete treatment.

[46]. Many clinicians worry that this diagnosis will be misused to the same extent as the diagnosis of bipolar disorder [43]. Mistakes can be avoided by correctly following the algorithm, for example, if you take outbursts of anger as a key and distinguishing feature for a number of conditions where they are present, just as types of catatonia allow you to distinguish between a number of pathologies. For example, the diagnosis "ADHD with outbursts of anger" - the key ones in this case, could be regarded as an independent diagnosis of "outbursts of anger", which would allow for more complete treatment.

Interview discrepancy

A mandatory minimum in child and adolescent psychiatry is the history taking of the parent/guardian and the child. In the case of behavioral disorders, as in ADHD, it is also important to seek the opinion of teachers. Unfortunately, it turned out that the coincidences in the survey data are very small. The measure of kappa correspondence between the words of the child and the parent in the case of mania or depressive symptoms is usually below 0. 2.

2.

At the same time, Biederman et al. found that in 62.7% of cases of mania, both parent and child admitted to having manic symptoms [47]. Data from Tillman et al. differed a little - 49.5% [48]. However, Tillman in the study showed that the highest compliance rates of the survey results are characteristic of ADHD symptoms (80% for accelerated speech, 91.4% for hyper-energy, 85.9% for motor activity), 75.8% for irritable mood, scores were significantly lower for other symptoms of mania (42.2% elevated mood, 32.5% sense of grandeur, 35.8% thought racing, 34.4% disinhibited behavior, 16.2% reduced need for sleep, 21.4% - psychotic phenomena). In addition, children were much less likely to admit to specific symptoms of mania than their parents. Hence the simple explanation for such frequent disputes over the diagnosis: mania or ADHD, since, for the most part, when assessing the mental state of a child, specialists are guided by the interpretation of parents.

In the study of bipolar disorder, researchers have never set out to determine the value of any other sources of information about the child's manic behavior, other than parents.

The correlation of data received from parents and teachers approaches r = 0.3 [49]. Carlson and Blader report that where teacher and parental indications of mania symptoms (as measured by the Childhood Mania Rating Scale) were highly consistent, logistic regression revealed a 10-fold prevalence of other diagnoses associated with exogenous disorders (ADHD). , oppositional disorder, behavioral disorder, or a combination of these diseases) [1, 50]. And in children with bipolar spectrum disorders, the degree of agreement between parents and teachers was higher. In contrast, in the spectrum of endogenous diseases (anxiety and depressive disorders), there was a 3.7 times greater discrepancy between the information received from teachers and parents using the children's mania rating scale.

This study used a more advanced system for evaluating information from parents, children, and teachers, in addition to a simple survey, often without a specific structure, in making a diagnosis. More research is needed to explain why a child's severe condition lasting weeks is noticed by parents but not by teachers.

More research is needed to explain why a child's severe condition lasting weeks is noticed by parents but not by teachers.

Family history

Obviously, bipolar disorder has a hereditary component [51]. A long-published meta-analysis of studies has shown that children of parents with bipolar disorder are 2.7 times more likely to develop a mental disorder and 4 times more likely to have a mood disorder than children of healthy parents [52]. Recent trials have confirmed these figures [53]. However, it is interesting that the risk of developing general psychopathological disorders turned out to be much higher than type I bipolar disorder. For example, Hillegers et al. found that by the age of 21, among Dutch teenagers at high risk, 3% had type I bipolar disorder, 10% had bipolar disorder, but 59% had some kind of psychopathology [54]. Although high-risk children with mood disorders are more likely than healthy children to develop bipolar disorder in adulthood, they are also at significant risk of developing a wide range of other diseases [55].

Many studies focusing on high-risk groups compare children of parents with bipolar disorder with those of a control group whose parents do not have a mental disorder, indicating a difference in risk. However, children from families with any other mental illness, such as ADHD, autism, learning disabilities, other mood disorders and schizophrenia, also come to the attention of doctors. It is believed that children whose parents responded well to lithium therapy have a milder disease course than those whose parents are resistant to lithium [56]. This could help in the selection of therapy in the case of a diagnosis of type I bipolar disorder. And yet, the presence of a diagnosis in the parents does not mean the presence of the disease in the child.

Finally, the age at risk for bipolar disorder is significantly stretched. In a Danish population study that included a group of children whose parents had at least once been hospitalized with bipolar disorder, it was found that by the age of 53, among "children" with a parent who was ill, the risk was 4. 4% compared with a 0.48% risk in those who had parents without bipolar disorder. The difference in risk among children under 20 years of age is negligible [57]. From these indicators, it follows that suspicions about bipolar disorder are increasing, but the fact of a family history cannot be taken as an absolute criterion for making such a diagnosis, especially if the child does not have other diagnostic components of the disease.

4% compared with a 0.48% risk in those who had parents without bipolar disorder. The difference in risk among children under 20 years of age is negligible [57]. From these indicators, it follows that suspicions about bipolar disorder are increasing, but the fact of a family history cannot be taken as an absolute criterion for making such a diagnosis, especially if the child does not have other diagnostic components of the disease.

Conclusions

Although type I mania/BAD often begins at an early age, it is better to delay diagnosis for more than one year. This is a serious condition that reduces the ability to work, but there are other diseases from which it should be able to distinguish. Psychosis, substance abuse, and agitated unipolar depression present great difficulties in making a differential diagnosis in adolescents. Defining executive dysfunctions in children is also challenging. A multilateral survey increases the chances of a correct diagnosis, although it is necessary to clearly understand the difference and correctly compare the answers of parents, teachers and the child himself. Having a family history of illness may increase the risk of certain symptoms and behavioral problems associated with the onset of bipolar disorder, but the diagnosis should not be made based on the history. In addition, difficult children are most often from difficult families.

Having a family history of illness may increase the risk of certain symptoms and behavioral problems associated with the onset of bipolar disorder, but the diagnosis should not be made based on the history. In addition, difficult children are most often from difficult families.

Until biomarkers are identified to accurately confirm the diagnosis and drugs that are exclusively specific for this pathology, it makes sense to diagnose bipolar disorder in children and adolescents only temporarily, with the expectation of the need for re-examination in the future [58]. The claim that a child is ill for life requires more evidence than we have.

Literature

- Carlson G.A., Blader J.C. Diagnostic implications of informant disagreement for manic symptoms // J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. - 2011. - 21. - R. 399-405.

- Akiskal H.S., Khani M.K., Scott-Strauss A. Cyclothymic temperamental disorders // Psychiatr Clin North Am. - 1979. - 2. - R. 527-554.

- Jorge R.

E., Robinson R.G., Starkstein S.E. et al. Secondary mania following traumatic brain injury // Am J Psychiatry. - 1993. - 150. - R. 916-921.

E., Robinson R.G., Starkstein S.E. et al. Secondary mania following traumatic brain injury // Am J Psychiatry. - 1993. - 150. - R. 916-921. - Max J.E., Robertson B.A., Lansing A.E. The phenomenology of personality change due to traumatic brain injury in children and adolescents // J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. - 2000. -13. - R. 161-170.

- Wilens T.E., Biederman J., Millstein R.B. et al. Risk for substance use disorders in youths with child- and adolescent-onset bipolar disorder // J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. - 1999. - 38. - R. 680-685.

- Carlson G.A., Bromet E.J., Lavelle J. Medication treatment in adolescents vs. adults with psychotic mania // J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. - 1999. - 9. - R. 221-231.

- Carlson G.A., Naz B., Bromet E.J. Phenomenology and assessment of adolescent-onset psychosis: observations from a first admission psychosis project. In: Findling R.L., Schultz S.C. (eds). Juvenile onset schizophrenia. - Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005.

- R. 1-38.