Dsm 5 criteria for persistent depressive disorder

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.

Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.

For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

DSM-5-TR Updates Persistent Depressive Disorder Diagnostic Criteria, Suicidal Behavior Codes

Dr Michael B. First.In this Q&A, Michael B. First, MD, professor of clinical psychiatry, Columbia University, New York City, editor & co-chair, DSM-5-TR, answers questions about his panel presented at Psych Congress Elevate 2022, entitled "DSM-5 Text Revision (DSM-5-TR): What's New and What's Different."

Dr First reviews key changes to the "Introduction" and "Use" sections, explains new diagnostic criteria for depression and suicidal behavior codes that have been incorporated, and offers insights on how the updated text will aid clinicians in their practice.

Meagan Thistle, Associate Digital Editor, Psych Congress Network: What key changes have been made to the “Introduction” and “Use of the Manual” sections of the DSM-5-TR?

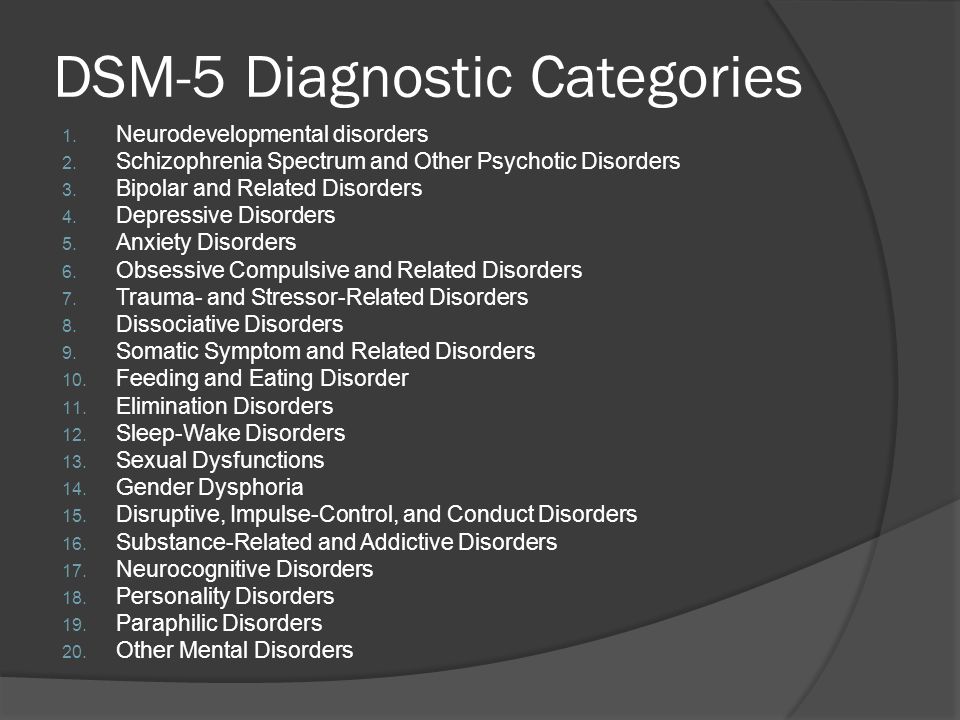

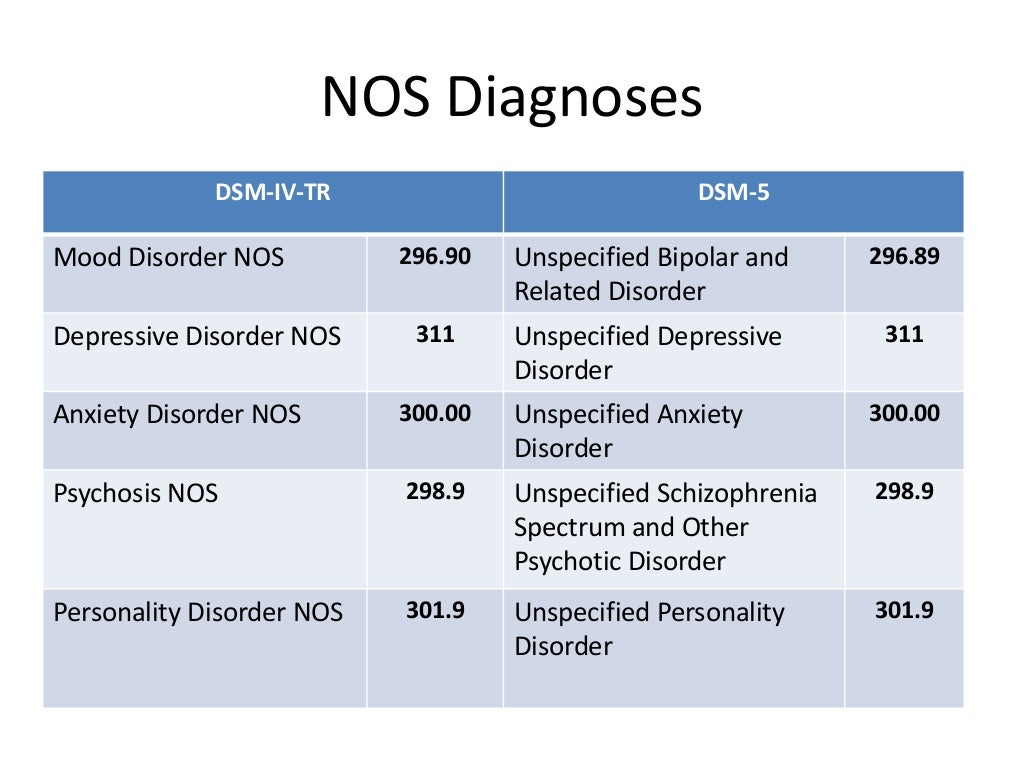

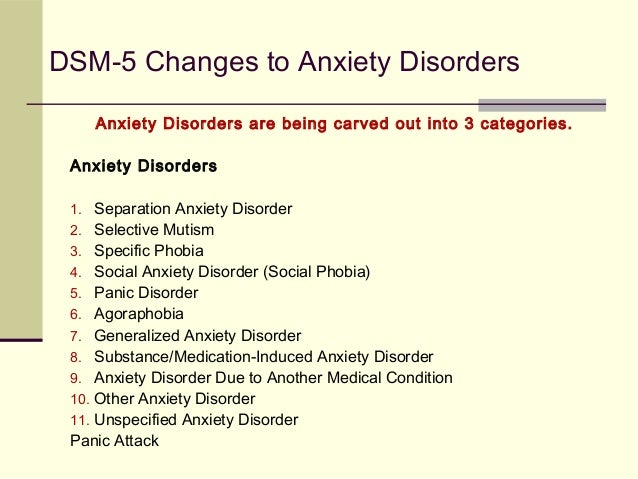

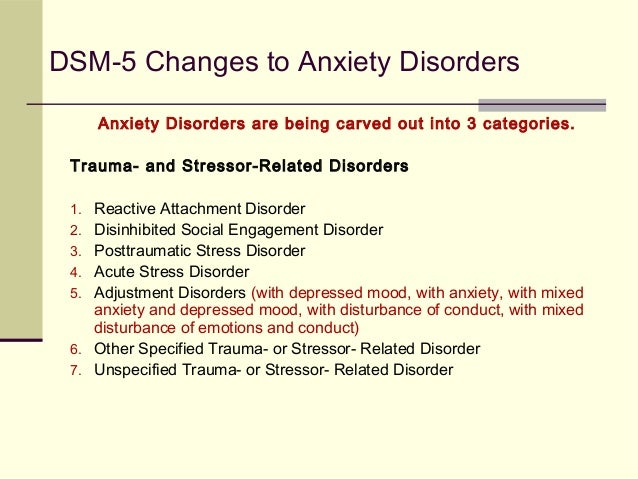

Michael B. First, MD: New sections have been added for describing the various types of information included in the DSM-5-TR text, providing explanations for potentially confusing terms such as “substance/medication-induced disorders,” “independent mental disorders,” and “other medical condition”; and the difference between the terms “other specified disorder” and “unspecified disorder.” There is also a new section discussing the impact of racism and discrimination on psychiatric diagnosis.

First, MD: New sections have been added for describing the various types of information included in the DSM-5-TR text, providing explanations for potentially confusing terms such as “substance/medication-induced disorders,” “independent mental disorders,” and “other medical condition”; and the difference between the terms “other specified disorder” and “unspecified disorder.” There is also a new section discussing the impact of racism and discrimination on psychiatric diagnosis.

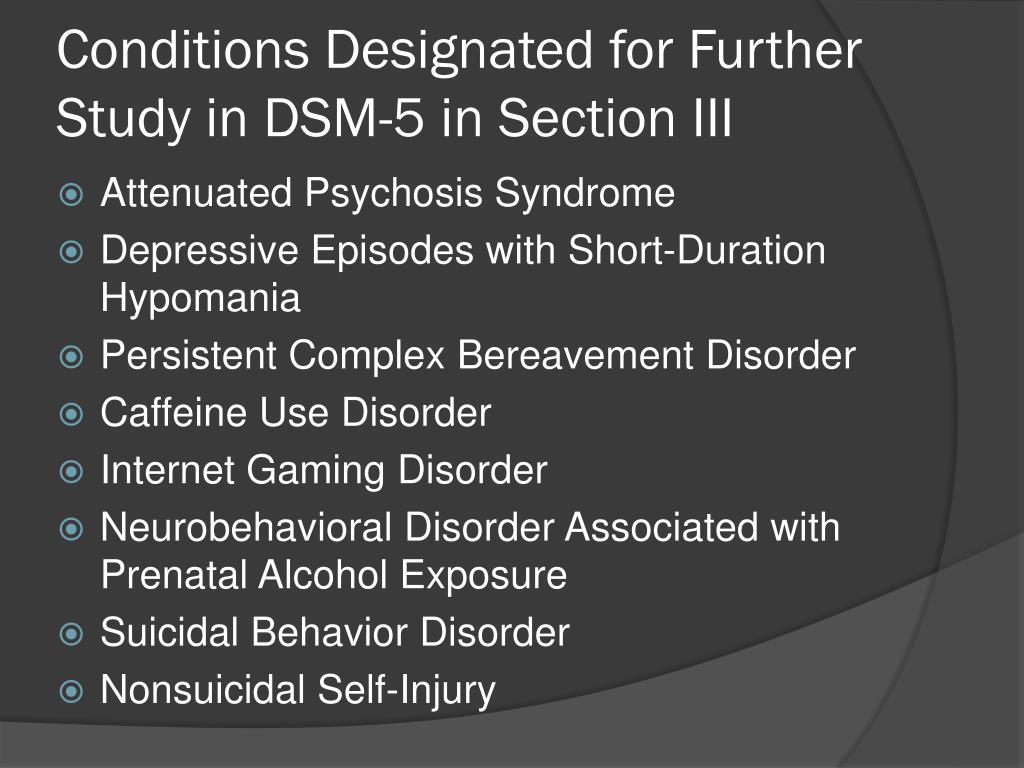

Thistle: “Prolonged grief disorder” has been added to Section II. How is it defined?

Dr First: Prolonged grief disorder is characterized by intense, prolonged grief (intense yearning for the decreased or preoccupation with thoughts of the deceased) occurring nearly every day that persists beyond 12 months post-loss that causes clinically significant distress or impairment. People suffering from this are essentially “stuck” in the grieving process and cannot move forward with their lives.

Thistle: How will the addition of this new diagnosis impact clinical practice?

Dr First: Individuals suffering from this condition are at risk for developing serious medical conditions, including cardiac disease, hypertension, cancer, and immunological deficiency, as well as having a reduced quality of life. Recognizing the presence of this condition is a necessary step towards getting the proper treatment, namely targeted psychotherapeutic interventions as well as avoiding ineffective treatments, such as antidepressant medications which have not been demonstrated to be effective except if there is comorbid depression.

Thistle: While there are modifications to the diagnostic criteria for over 70 disorders, what are some of the most important to highlight that clinicians should know about?

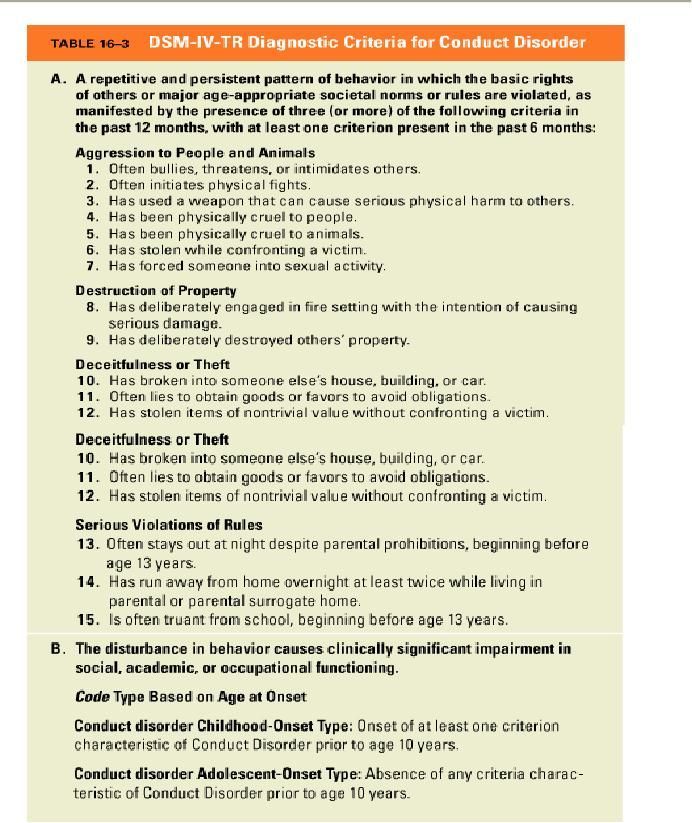

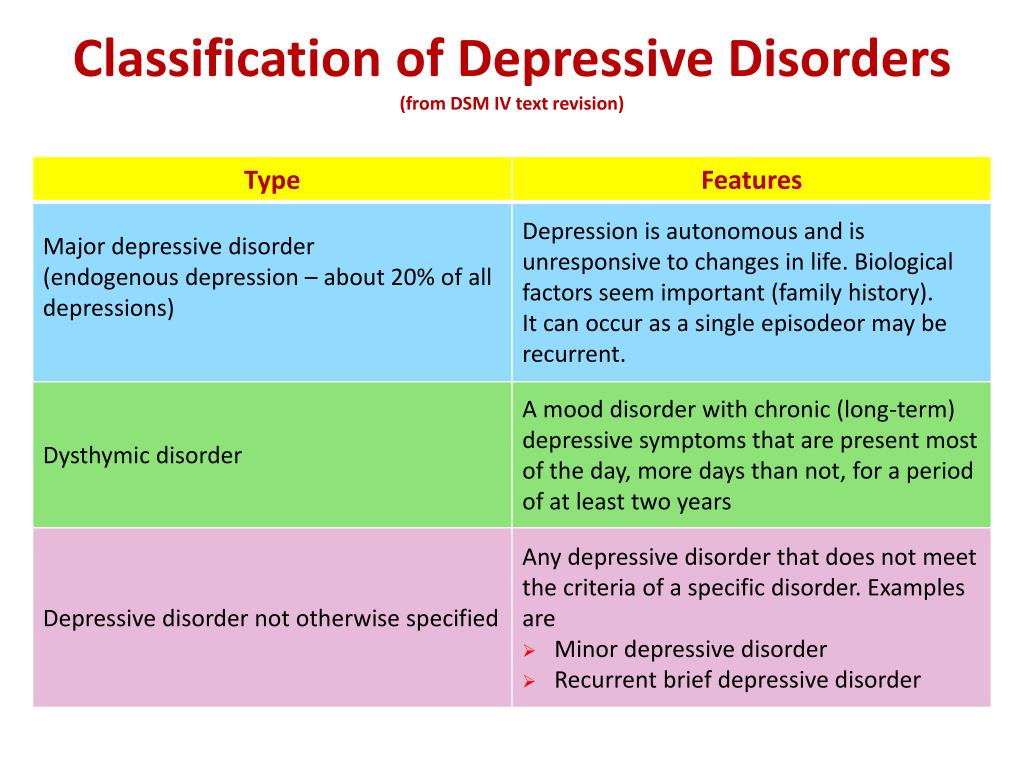

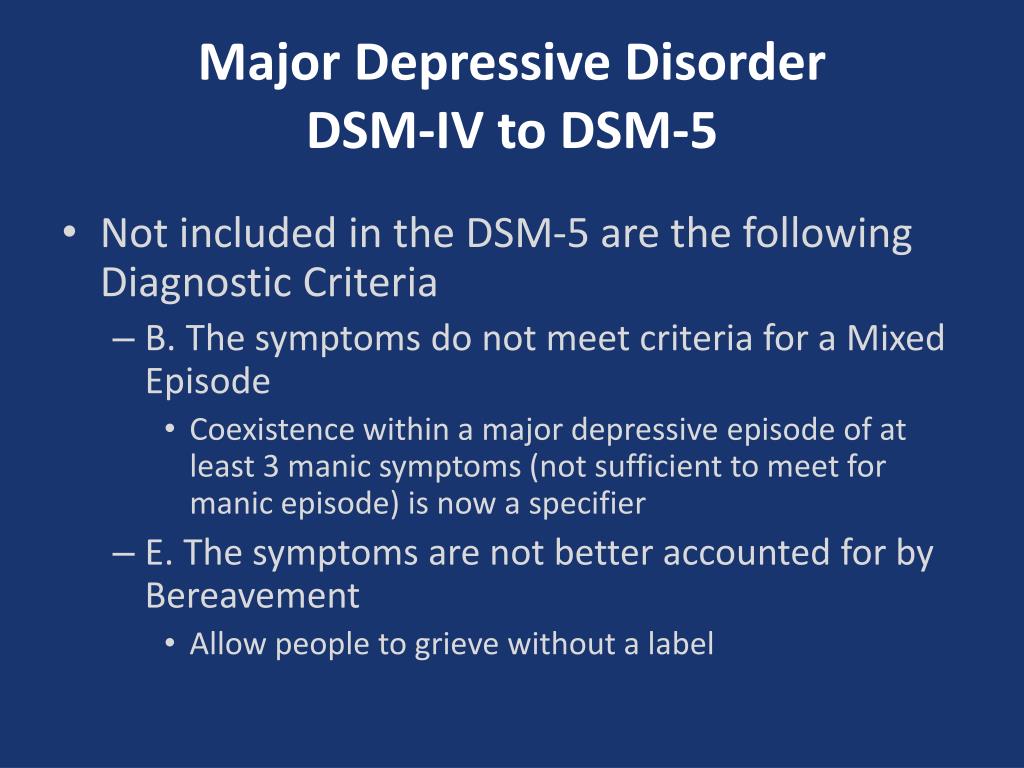

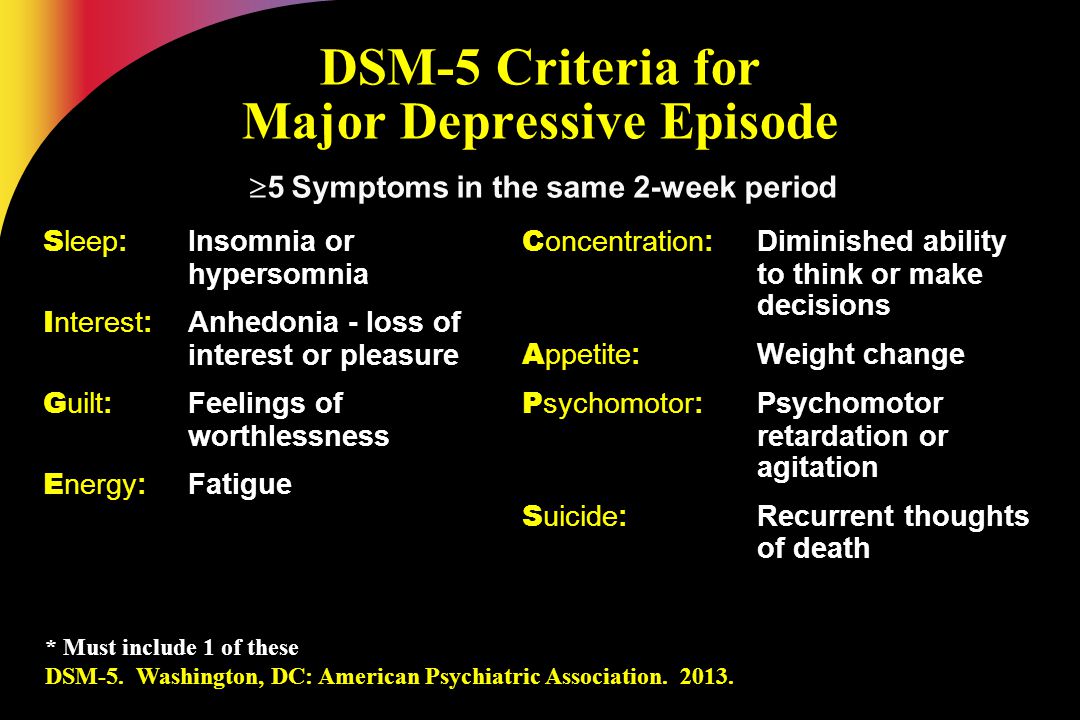

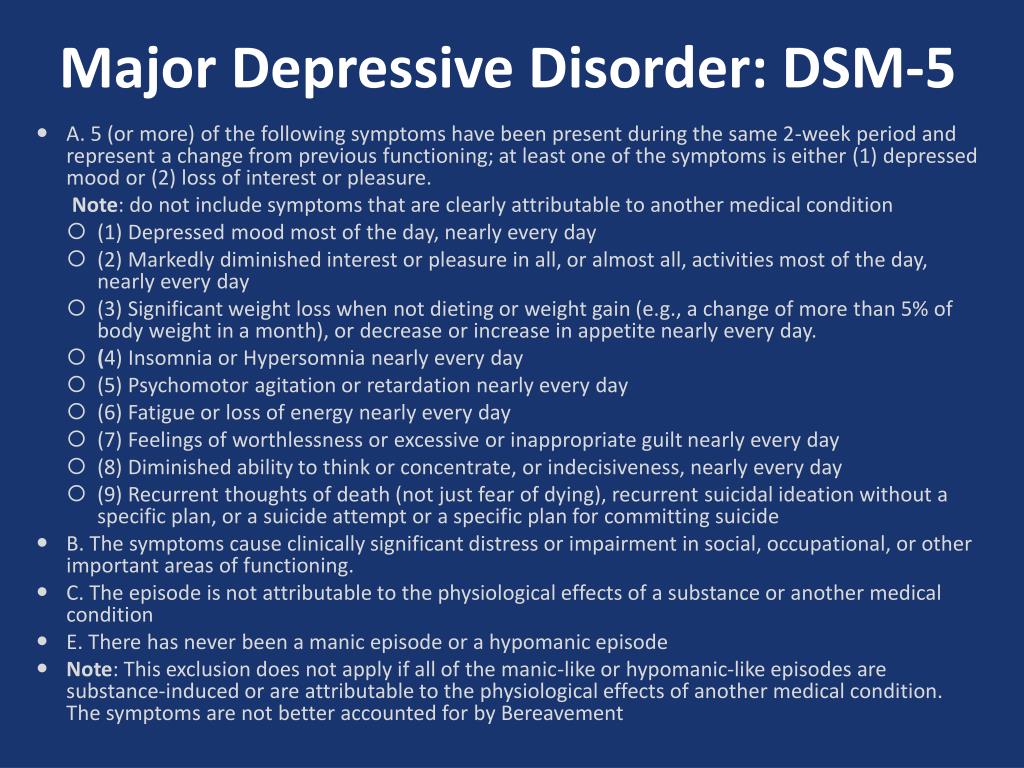

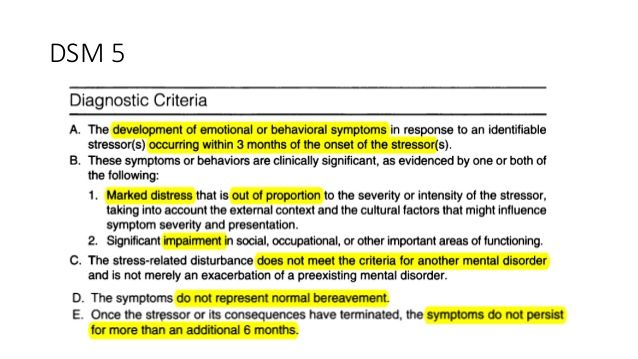

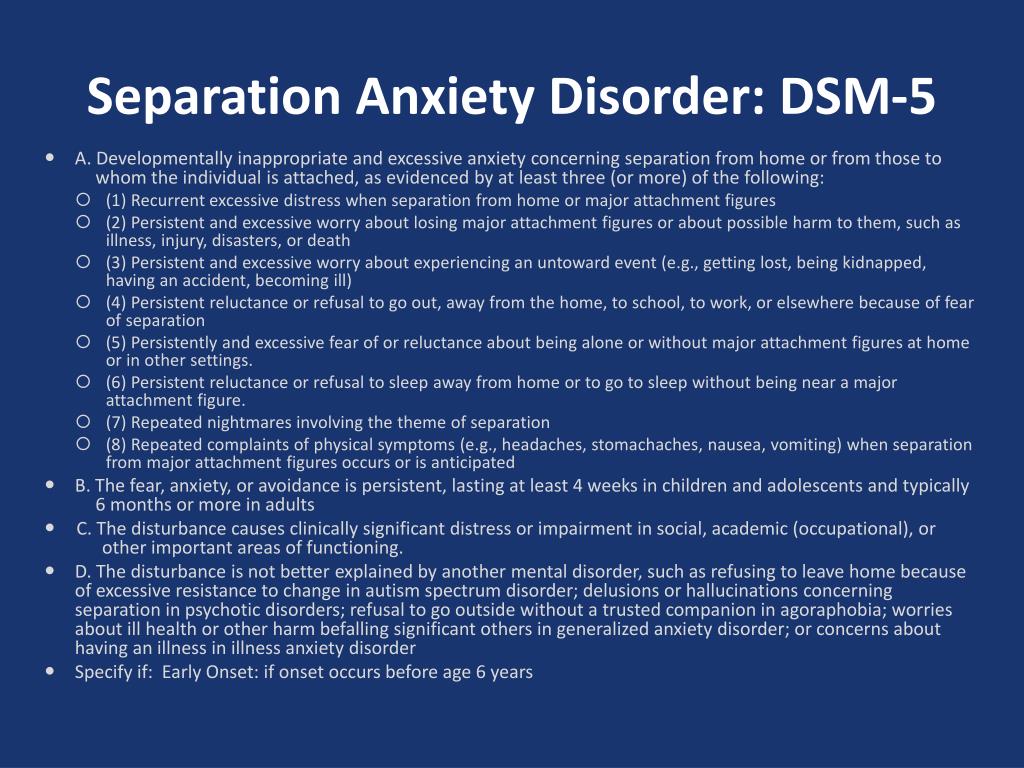

Dr First: The most important change concerns the diagnostic criteria for Persistent Depressive Disorder. The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria and text for persistent depressive disorder (depressed mood for more days than not lasting at least 2 years) gave contradictory guidance regarding how best to diagnose and code presentations with superimposed major depressive episodes (so-called “double depression”) as well as chronic episode lasting longer than 2 years: giving a single diagnosis (persistent depressive disorder) and diagnostic code (F34. 1) along with the applicable course specifier (with pure dysthymic syndrome, with persistent major depressive episode, with intermittent major depressive episodes), or whether to also give an additional diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder along with the applicable code (e.g., F33.3 Recurrent Major Depressive Disorder, with psychotic features).

1) along with the applicable course specifier (with pure dysthymic syndrome, with persistent major depressive episode, with intermittent major depressive episodes), or whether to also give an additional diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder along with the applicable code (e.g., F33.3 Recurrent Major Depressive Disorder, with psychotic features).

Giving 2 diagnoses has the clear advantage of allowing the clinician to indicate such important clinical features such as episode recurrence, the severity (mild, moderate, or severe), or presence of psychotic features of the current (or most recent) depressive episode. Consequently, the following note has been added to the diagnostic criteria for persistent depressive disorder:

Note: If criteria are sufficient for a diagnosis of a major depressive episode at any time during the 2-year period of depressed mood, then a separate diagnosis of major depression should be made in addition to the diagnosis of persistent depressive disorder along with the relevant specifier (e. g., with intermittent major depressive episodes, with current episode).

g., with intermittent major depressive episodes, with current episode).

Thistle: How can the new codes for suicidal behavior and nonsuicidal behavior be used?

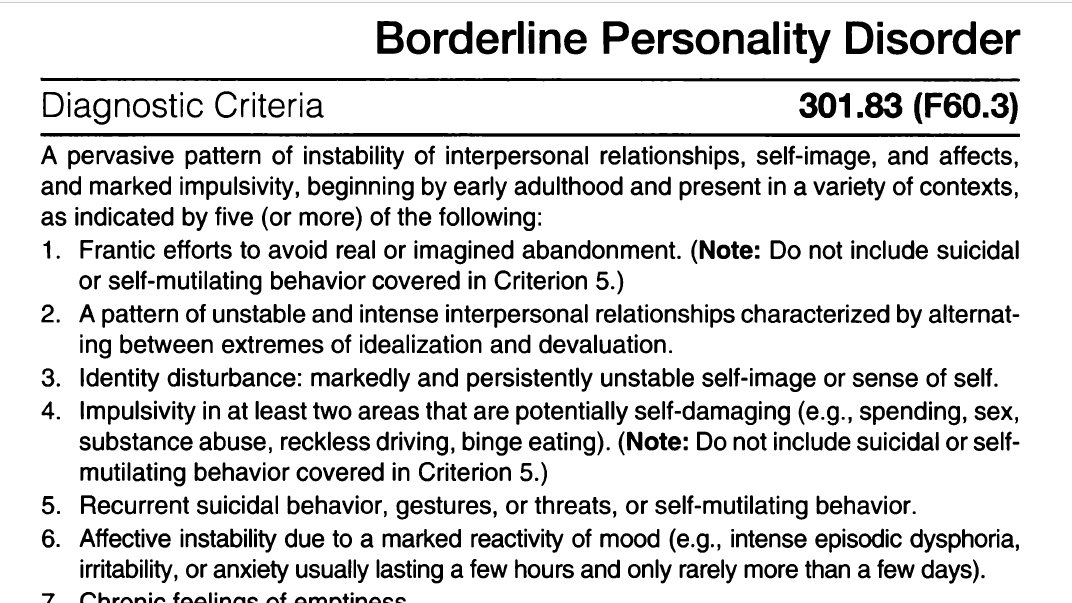

Dr First: Despite the importance of suicidal behavior in the management of patients, suicidal behavior appears in the diagnostic criteria sets for only two DSM-5 disorders—major depressive episode and borderline personality disorder—despite its common association with a wide variety of DSM disorders, such as schizophrenia and substance use disorders. DSM-5-TR now includes free-standing symptom codes to indicate current suicidal behavior as well as a history of suicidal behavior that can be given in addition to a psychiatric diagnosis (or even in the absence of a psychiatric diagnosis) to allow clinicians to highlight this important symptom. Symptoms codes for nonsuicidal self-injury have been added as well.

Thistle: Has anything notable been removed from the DSM-5-TR that would impact clinical practice?

Dr First: No.

Thistle: What else should clinicians know about the DSM-5 changes that you would like to discuss?

Dr First: Three diagnoses have been added to DSM-5-TR that are also notable. Prior editions recognized that chronic heavy use of three classes of substance (alcohol, inhalants, sedatives/hypnotics/anxiolytics) can cause persisting dementia. The replacement of the dementia category (which appeared in editions of DSM up to DSM-IV) with a dimensional neurocognitive disorder construct (i.e., mild neurocognitive disorder and major neurocognitive disorder) in DSM-5 allowed for neurocognitive disorders that were less severe that dementia to be diagnoses. Given that persistent use of stimulants such as methamphetamine and cocaine is known to cause neurocognitive impairment that can interfere with functioning to a certain degree, yet not so much so as to interfere with capacity for independence in everyday activities, stimulant-induced mild neurocognitive should have been added to DSM-5-TR.

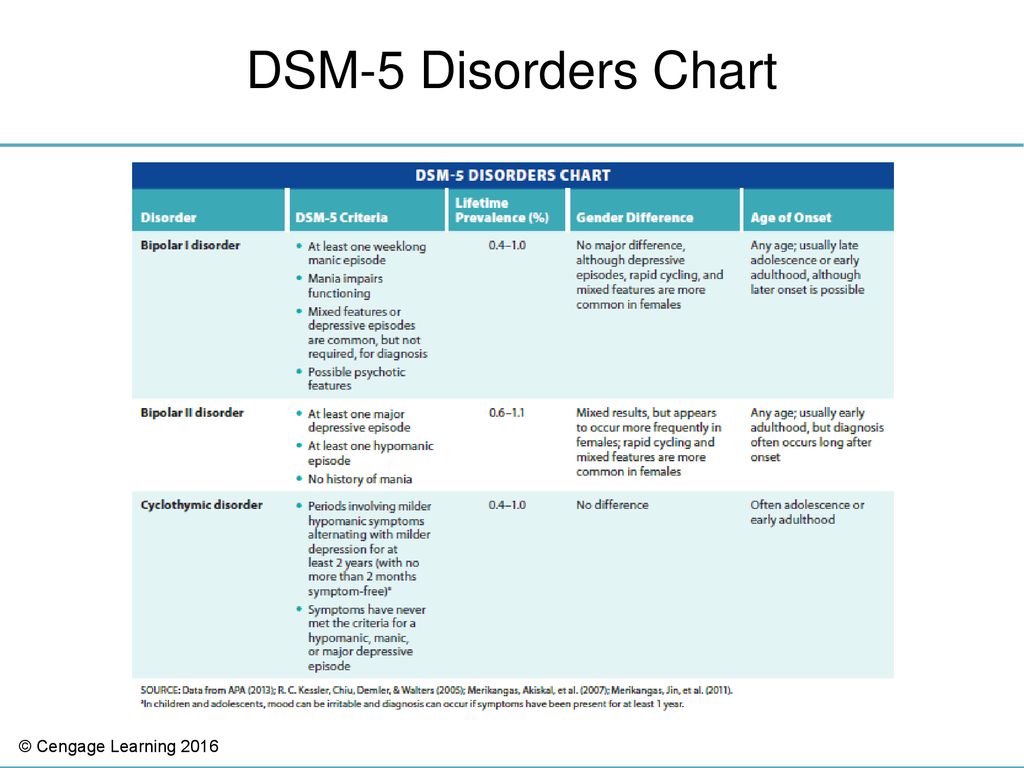

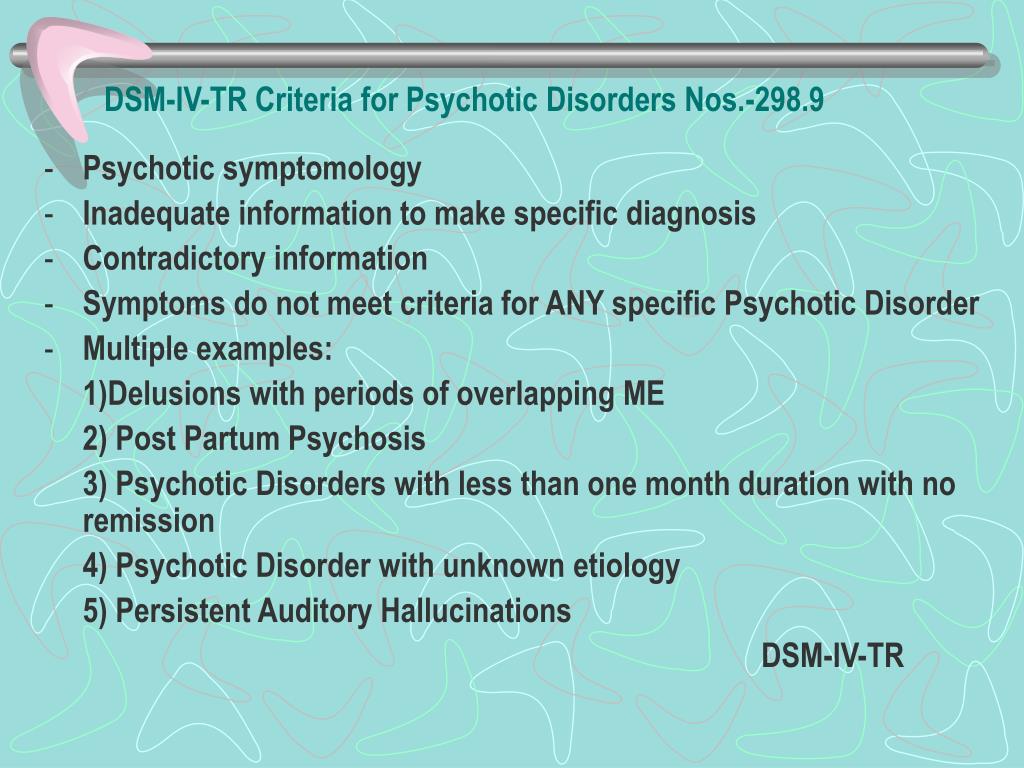

Additionally, Unspecified Mood Disorder has been added for presentations of irritability and agitation, for which there is insufficient information to make a specific diagnosis, to give clinicians an alternative to having to decide between an unspecified bipolar or unspecified depressive disorder, especially since irritability may be indicative of either.

Finally, there are circumstances in which, after a psychiatric examination, the clinician concludes that there is no mental disorder, such as in the context of a workplace evaluation for fitness for duty.

Michael B. First, MD, is Professor of Clinical Psychiatry at Columbia University, Research Psychiatrist at the Department of Behavioral Health and Policy Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute, and maintains a d psychopharmacology practice in Manhattan, Dr. First is a nationally and internationally recognized expert on psychiatric diagnosis and assessment issues and conducts expert forensic psychiatric evaluations in both criminal and civil matters.

Dr. First is Editor and Co-chair of the DSM-5-TR, Editorial and Coding Consultant for DSM-5, a member of the DSM-5 Steering Committee, the chief technical and editorial consultant on the World Health Organization’s ICD-11 revision project, for the Mental, Behaviral, and Neurodevelopmentla disorders chpater. Dr. First was the Editor of the DSM-IV-TR, the Editor of Text and Criteria for DSM-IV and the American Psychiatric Association’s Handbook on Psychiatric Measures. He has co-authored and co-edited a number of booksm including the DSM-5 Handbook for Differential Diagnosis, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5), and Learning DSM-5 by Case Example.. He has trained thousands of clinicians and researchers in diagnostic assessment and differential diagnosis.

the role of family relations //Psychological newspaper

Depression is one of the most common psychopathological affective spectrum disorders during pregnancy and after childbirth [1]. According to the literature, the prevalence of depressive disorders during pregnancy and after childbirth is 7–15%. [2; 3]. However, in most cases, these disorders, for a number of reasons, remain undiagnosed [4].

According to the literature, the prevalence of depressive disorders during pregnancy and after childbirth is 7–15%. [2; 3]. However, in most cases, these disorders, for a number of reasons, remain undiagnosed [4].

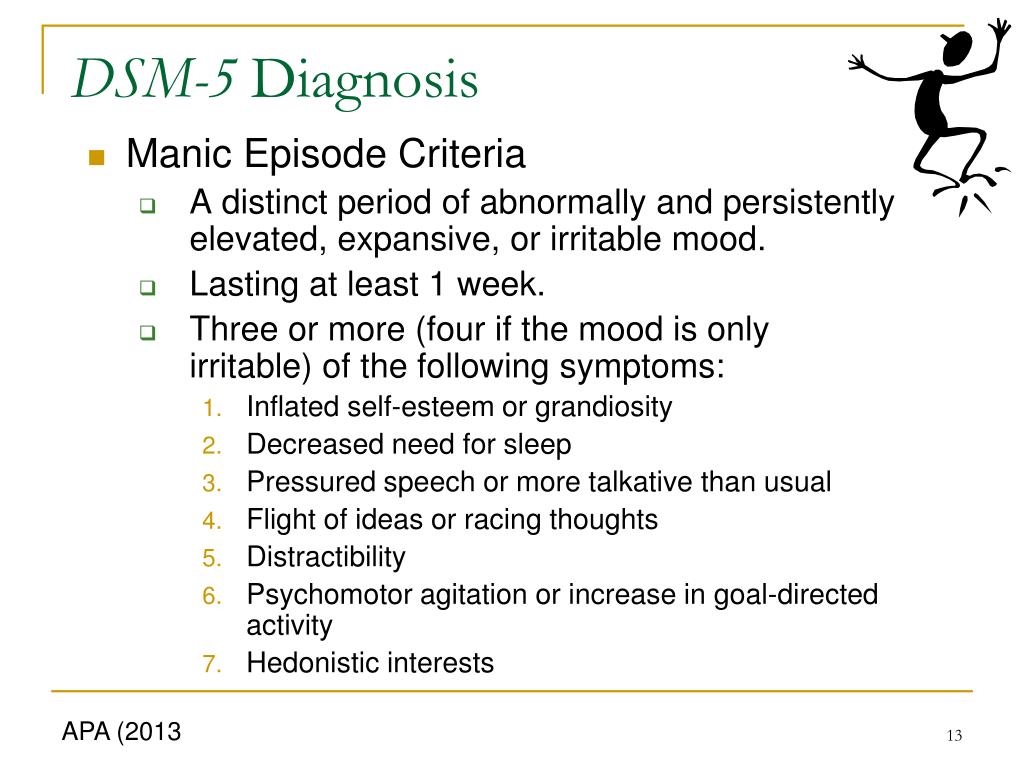

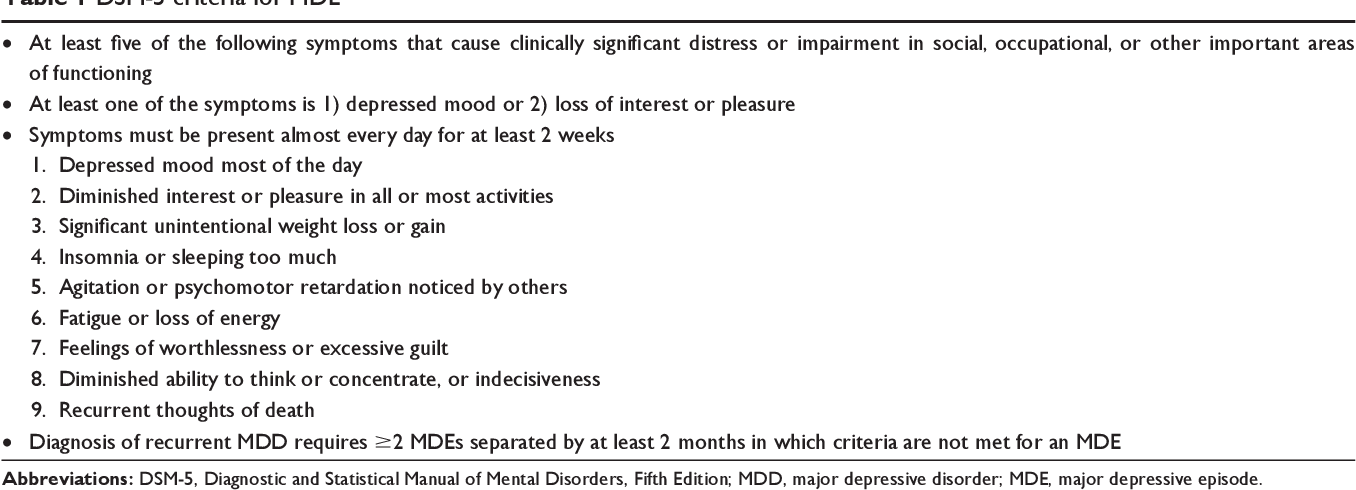

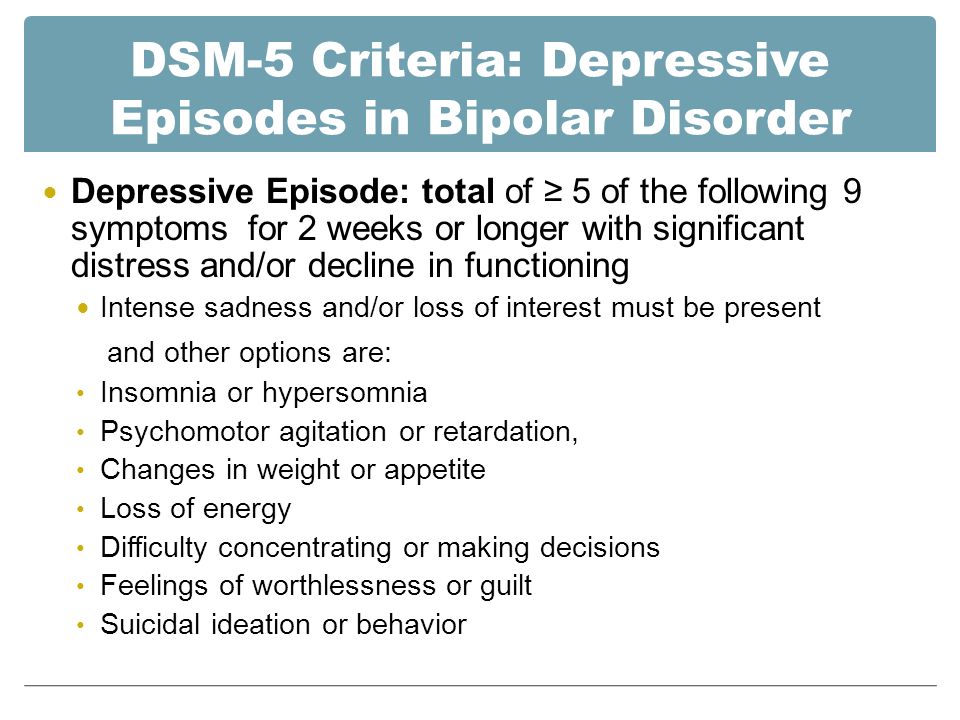

According to the DSM-5 (2013) criteria, antenatal and postnatal depression is considered to be non-psychotic depression that meets the criteria for a major depressive episode that develops during pregnancy or within the first six months after childbirth.

The leading psychopathological disorder in the clinical picture is a depressed mood, lasting more than two weeks, not reaching the degree of pronounced melancholy. Decreased mood is accompanied by a loss of self-confidence, unreasonable reproaches against oneself, and a sense of guilt. Women are often pessimistic about the future, but this attitude is not generalized, but limited only to the zone of certain events (relationship with her husband, upcoming birth, motherhood, child care, etc.). Patients, as a rule, are critical of their condition and are interested in resolving conflict situations. Depressive symptoms manifest themselves in complaints, in the statements of women, without significantly affecting their appearance and behavior. The dynamics of the state is characterized by the fact that a depressed mood does not acquire the properties of persistent depression, but is subject to significant fluctuations. It is important to note that a depressive disorder is often combined with anxiety and asthenic manifestations in the emotional sphere [5–7].

Depressive symptoms manifest themselves in complaints, in the statements of women, without significantly affecting their appearance and behavior. The dynamics of the state is characterized by the fact that a depressed mood does not acquire the properties of persistent depression, but is subject to significant fluctuations. It is important to note that a depressive disorder is often combined with anxiety and asthenic manifestations in the emotional sphere [5–7].

Currently, the point of view is accepted that a complex of biological, psychological and social factors is involved in the initiation of prenatal and postnatal depression [8; 9]. It is known that depression during pregnancy is regarded as a risk factor for the development of postpartum depression. In approximately one third of women, depression that occurs during pregnancy continues after childbirth [10; eleven]. Many studies point to the significant role of psychosocial factors [12–15]. Family relationships, as a rule, are the most important, significant for the individual, this explains their leading role in the formation of mental disorders [16; 17]. Meanwhile, even with a fairly harmonious relationship between the spouses, the family expecting the birth of a child is on the verge of serious changes, its functioning becomes unstable [18].

Meanwhile, even with a fairly harmonious relationship between the spouses, the family expecting the birth of a child is on the verge of serious changes, its functioning becomes unstable [18].

In this regard, the issue of studying family functioning in women with depressive disorders before and after childbirth is extremely relevant in order to clarify the role of the family relationship factor, namely the relationship with the spouse, in the formation of this pathology.

Purpose of study

To study the features of family functioning of women with depressive disorder during pregnancy and the postpartum period, as well as to conduct a comparative analysis of the data obtained in the two study groups.

Material and methods

On the basis of the Federal State Budgetary Institution "North-Western Federal Medical Research Center", the Department of Biological Therapy of the Mentally Ill of the Federal State Budgetary Institution "Psychoneurological Institute named after V. M. Bekhterev" and the antenatal clinic No. 8 ± 0.53) and 42 postpartum women (age 28.4 ± 0.46). Depressive disorders in women were diagnosed using the clinical and psychopathological method and psychodiagnostic methods: the Tsung scale for self-assessment of depression (T. G. Rybakova, T. I. Balashova, 1988) [1] and the Questionnaire of depressive states (I. G. Bespalko, 1995) [19]. The study of family functioning in groups was carried out using the FACES-III questionnaire “Family Adaptation and Cohesion Scale” [20].

M. Bekhterev" and the antenatal clinic No. 8 ± 0.53) and 42 postpartum women (age 28.4 ± 0.46). Depressive disorders in women were diagnosed using the clinical and psychopathological method and psychodiagnostic methods: the Tsung scale for self-assessment of depression (T. G. Rybakova, T. I. Balashova, 1988) [1] and the Questionnaire of depressive states (I. G. Bespalko, 1995) [19]. The study of family functioning in groups was carried out using the FACES-III questionnaire “Family Adaptation and Cohesion Scale” [20].

When comparing the results, social characteristics (education, work, marital status, financial situation, etc.) were taken into account, in which the groups did not differ significantly.

Statistical data processing was carried out using the program Statistica version 7.0.

Results of study

The concept of "family adaptation" reflects the ability of the family to adapt to changing conditions of life, i.e. it is a characteristic of how flexible or, conversely, stable relations in the family. The concept of "Family cohesion" defines the type of emotional closeness of family members. Family adaptation and cohesion can be organized at extreme (disjointed and linked, rigid and chaotic) and balanced levels (structural and flexible, divided and connected). Extreme levels are usually viewed as problematic, leading to dysfunction of the family system, while balanced levels determine its success (see table and figure).

The concept of "Family cohesion" defines the type of emotional closeness of family members. Family adaptation and cohesion can be organized at extreme (disjointed and linked, rigid and chaotic) and balanced levels (structural and flexible, divided and connected). Extreme levels are usually viewed as problematic, leading to dysfunction of the family system, while balanced levels determine its success (see table and figure).

In the group of women with depressive disorder during pregnancy, there were 6 types of families (out of 16 possible): linked-chaotic (48%) disconnected-rigid (15%) disconnected-structural (13%) connected-chaotic (20%) connected-rigid (2%) bonded-flexible (2%). Thus, 63% have extreme values for both levels, and belong to the extreme type of functioning; 37% have extreme values for one of the levels, and belong to the average type of functioning.

In the group of women with postpartum depression, the following 8 types of families were observed (out of 16 possible): linked-chaotic (20%), disconnected-rigid (16%), disconnected-structural (25%), disconnected-chaotic (15%), divided-chaotic (15%), connected-structural (6%), separated-structural (2%), disconnected-flexible (1%). Thus, 51% of families have extreme values for both levels and belong to the extreme type of functioning; 41% of families have extreme values for one of the levels, and belong to the average type of functioning; 8% belong to the balanced type of functioning.

Thus, 51% of families have extreme values for both levels and belong to the extreme type of functioning; 41% of families have extreme values for one of the levels, and belong to the average type of functioning; 8% belong to the balanced type of functioning.

Analysis of the results shows that the types of functioning of families in both groups do not differ significantly (p ≤ 0.01). Families of pregnant women and postpartum women with depressive disorders are characterized by the dominance of the extreme type of functioning and the absence of a balanced type.

The “family cohesion” parameter: families of pregnant women with depressive disorder 43.15 ± 0.79 are characterized by the “associated” type of family cohesion. And for the families of women with postpartum depression, the most characteristic is the “disunited” type of family cohesion 34.45 ± 2.07.

The parameter "family adaptation": the average values of the level of family adaptation in both groups belong to the "chaotic" (extreme) type (in the group of pregnant women 32. 91 ± 1.02, in the group of women after childbirth 31.5 ± 1.85).

91 ± 1.02, in the group of women after childbirth 31.5 ± 1.85).

Talk

Thus, the data obtained indicate that in the families of women with depression, both in the prenatal and postnatal periods, there is a violation of family relationships. Moreover, the parameter "family cohesion" indicates the dynamics of the deterioration of relations. This reflects the fact that the family system is not able to reorganize to a new level of functioning (to accept new roles of “mother” and “father” for family members) and at the same time maintain harmonious marital relations.

Families of pregnant women with depression, as well as families of women with postpartum depression, are characterized by:

- blurred borders;

- the absence of a clearly defined leader;

- a tendency to make impulsive decisions, subject to the prevailing circumstances at the time of the decision;

- ambiguity of the roles of family members, often passing from one family member to another;

- lack of clearly defined rules;

- the distance of relations between family members, which differ in the autonomy of each of them;

- emotional disunity, insufficient attachment to each other of family members, inconsistency in their behavior;

- a tendency to separate spending free time, a difference in interests, the absence of mutual friends;

- inability to jointly solve everyday problems, lack of desire and skills to support each other.

Doctors often explain the presence of depressive disorders in women both in the prenatal and postnatal periods as “hormonal” changes. However, not all pregnant women with hormonal dysfunctions have emotional disorders, although changes in hormone levels create a favorable background for the development of depressive disorders by increasing emotional reactivity, reducing the stability of the emotional background, mental and physical asthenia. Our observations show that biological factors are involved to a greater extent in the pathogenesis, and psychological - in the etiology of depressive disorders. This can be confirmed by the fact that family psychotherapy reduces psychopathological symptoms [21].

Our results support this assumption. In the families of pregnant women with depressive disorder and women with postpartum depression, disharmony of marital relations, violations of the family structure were revealed. This makes it possible to consider such families as dysfunctional, which is both a cause and a consequence of the development of depressive disorders in women of these families.

Attention should be paid to the extremely important mental state of the mother in the perinatal period for the development of the child. With depressive disorders, the mother is not able to establish a full and adequate interaction with the prenate and the baby. In the prenatal period, a pregnant woman can ignore the fact of pregnancy and continue to lead a former lifestyle, use psychoactive substances (alcohol, drugs, nicotine) and drugs, do not follow the recommendations of doctors or, conversely, against the background of somatization of anxiety, often visit specialists, exaggerate bodily sensations and etc. In such cases, the pregnant woman often lacks or insufficiently formed the psychological “image of the child” and “herself as a mother”, which disrupts the formation of the “mother-child” dyad in the prenatal period.

Children whose mothers experienced a depressive disorder during pregnancy or after childbirth differ from healthy children in that they cry more often, wake up, worry, they may have various psychosomatic reactions. In infancy, they have an increased level of cortisol, and cortisol continues to be produced in excess at an older age. Thus, their body is in a state of “toxic stress” [22–24].

In infancy, they have an increased level of cortisol, and cortisol continues to be produced in excess at an older age. Thus, their body is in a state of “toxic stress” [22–24].

The main methods of treatment of depressive disorders include psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. The general rule is the use of medicines only if the risk of complications for the pregnant woman (woman after childbirth) or the fetus (child) in case of refusal to use medicines exceeds the risk of their side effects. In this regard, psychotherapeutic methods for the treatment of depressive disorders in women in the perinatal period should be the methods of first choice. It is the family approach in psychotherapy that represents the best treatment option, since it is pathogenetic and allows achieving a stable therapeutic effect [25].

Conclusions

1. It is necessary to carry out psychological diagnostics (screening) in pregnant women and women after childbirth using specially directed scales to detect depressive disorders.

2. Psychosocial factors contribute to the formation of a system of "circular dependencies" and, in turn, support a depressive mood background. Psychocorrective and psychotherapeutic measures should be aimed at breaking the formed circular dependencies.

3. For the implementation of psychological prevention of depression during pregnancy and postpartum depression and when planning measures for psychological correction and psychotherapy, it is necessary to take into account not only the clinical features of the manifestation of depression, but also the context of family and social functioning of women during pregnancy and after childbirth.

4. When choosing tactics for the treatment of depression in pregnant women and in women after childbirth, psychotherapeutic methods and psychocorrective influences should be preferred. Psychopharmacotherapy should be used only for vital indications.

Literature

- Balashova T. N., Rybakova T.

G. Clinical and psychological characteristics and diagnosis of affective disorders in alcoholism: Methodological recommendations of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. L.: NIPNI im. V. M. Bekhtereva, 1988. S. 19–22.

G. Clinical and psychological characteristics and diagnosis of affective disorders in alcoholism: Methodological recommendations of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. L.: NIPNI im. V. M. Bekhtereva, 1988. S. 19–22. - Dougherty L. R. et al. Maternal psychopathology and early child temperament predict young children's salivary cortisol 3 years later // Abnorm Child. psycho. 2013. Vol. 41, No. 4. P. 531–542.

- Shulman H. B., Gilbert B. C., Lansky A. The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): current methods and evaluation of 2001 response rates // Public Health Rep. 2006 Vol. 121. R. 74–83.

- Smulevich A. B. Depression in somatic and mental diseases. M.: Medical Information Agency, 2003. 432 p.

- Kolesnikov I. A. Depressive disorders during pregnancy // Psychotherapy. 2008. No. 5. S. 8.

- Krasnov VN Disorders of the affective spectrum. M: Practical medicine, 2011. 432 p.

- Nuller Yu. L., Mikhalenko IN Affective psychoses.

L.: Medicine, 1988. 264 p.

L.: Medicine, 1988. 264 p. - Lee A. M. et al. Prevalence, course, and risk factors for antenatal anxiety and depression // Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Vol. 110, No. 5. P. 1102–1112.

- World Health Organization. Maternal mental health. 2015. URL: http://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/maternal_mental_health/en/ (Accessed 02/01/2015).

- Eidemiller EG, Yustickis V. Psychology and psychotherapy of the family. 4th ed. St. Petersburg: Piter, 2008. 672 p.

- Bennett H. A. et al. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review // Obstet. Gynecol. 2004 Vol. 103, No. 4. P. 698–709.

- Belyaeva E. N., Vasserman L. I., Mazo G. E. Clinical and psychological diagnostics and assessment of the factor of family relations in patients with postpartum depression // Sib. psychol. magazine 2011. No. 42. P. 6–13.

- Belyaeva E. N., Wasserman L. I., Zazerskaya I. E. Postpartum depression: clinical and psychological diagnosis and assessment of the role of the psychosocial factor // Bul.

FTsSKE them. V. A. Almazova. 2011. No. 6. S. 29–32.

FTsSKE them. V. A. Almazova. 2011. No. 6. S. 29–32. - Dobryakov I. V., Kolesnikov I. A. Perinatal psychotherapy of the family // Mental health. 2010. V. 8, No. 7. S. 24–27.

- Beck C. T. A meta-analysis of predictors of postpartum depression // Nurs. Res. 1996 Vol. 45, No. 5. P. 297–303.

- Wasserman L.I., Ababkov V.A., Trifonova E.A. Coping with stress: theory and psychodiagnostics: Study method. allowance. St. Petersburg: Rech, 2010. 192 p.

- Eidemiller E. G., Dobryakov I. V., Nikolskaya I. M. Family diagnosis and family psychotherapy. SPb., 2006. 352 p.

- Dobryakov I.V., Kolesnikov I.A. Depression during pregnancy // Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S. S. Korsakov. 2008. V. 108, No. 7. S. 91–97.

- Bespalko I. G. Questionnaire for the psychological diagnosis of depressive states: Method. NIPNI recommendations. V. M. Bekhtereva. SPb., 1995. 23 p.

- Shamanina M. V. Depressive states in the postpartum period: Abstract of the thesis.

dis. … cand. honey. Sciences. SPb., 2014. 24 p.

dis. … cand. honey. Sciences. SPb., 2014. 24 p. - Dobryakov IV Perinatal psychotherapy of the family // Vestn. new medical technologies. 2009. V. 16, No. 4. S. 191–192. 315

- Cooklin A. R., Rowe H. J., Fisher J. R. Employee entitlements during pregnancy and maternal psychological well-being // Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007 Vol. 47, No. 6. P. 483–490.

- Poggi D. E., Sandman C. A. Prenatal psychobiological predictors of anxiety risk in preadolescent children // Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012. Vol. 37, No. 8. P. 1224-1233.

- Shonkoff J. P., Garner A. S. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress // Pediatrics. 2012. Vol. 129, No. 1. P. 232–246.

- Kolesnikov I. A. Neurotic depressive disorders and family functioning in pregnant women: Abstract of the thesis. dis. … cand. honey. Sciences. St. Petersburg, 2010. 26 p.

Source: Kolesnikov I.A., Belyaeva E.N., Dobryakov I.V. , Zazerskaya I.E., Vasserman L.I. Depressive disorders in women during pregnancy and after childbirth: the role of family relations // Proceedings of the All-Russian scientific and practical conference with international participation "Modern problems of clinical psychology and personality psychology". - Novosibirsk: CPI NSU, 2017. - 318 p.

, Zazerskaya I.E., Vasserman L.I. Depressive disorders in women during pregnancy and after childbirth: the role of family relations // Proceedings of the All-Russian scientific and practical conference with international participation "Modern problems of clinical psychology and personality psychology". - Novosibirsk: CPI NSU, 2017. - 318 p.

What is dysthymia and how does it differ from depression

February 4 Likbez Health

Sad mood, low self-esteem, indecision and fear of the future may well be associated with this condition.

Share

0What is dysthymia

This is a chronic disorder in which mood is depressed for at least several years. And although dysthymia is similar to depression, its manifestations are not so severe that it can be diagnosed as a depressive episode or recurrent depression.

The main reference book for American psychiatrists, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), focuses on the duration of the condition. In DSM-5, dysthymia has a separate name - persistent, or permanent, depressive disorder.

In DSM-5, dysthymia has a separate name - persistent, or permanent, depressive disorder.

How does dysthymia differ from depression?

Both disorders have many similar symptoms: depressed mood, sleep problems, loss of energy, poor concentration. Dysthymia and depression are so similar that many psychiatrists believe that the disorders should be combined.

But there are differences between depression and dysthymia. Experts at Harvard Medical School list a few of the most obvious.

- With dysthymia, a person is able to enjoy life. Unlike the victim of depression, he can enjoy communicating with loved ones, get involved in hobbies.

- Dysthymia does not have pronounced psychomotor signs. For example, excessive excitement or obvious lethargy. If behavior changes quite dramatically during depression, then in the case of dysthymia, a person may appear calm, diligently go to work and go about daily activities.

- Dysthymia is sometimes felt as part of the personality.

Depressed people are able to realize that something is wrong with them. With dysthymia, a person becomes so used to a dreary state that he begins to consider depression as part of his character.

Depressed people are able to realize that something is wrong with them. With dysthymia, a person becomes so used to a dreary state that he begins to consider depression as part of his character.

How to recognize dysthymia and when to see a doctor

To draw a clearer line between disorders, psychiatrists suggest focusing primarily on mood and self-awareness, rather than on specific physical symptoms. Therefore, you should take a look at yourself.

Dysthymia is suspected when at least two of the following are present:

- weight changes;

- sleep problems;

- lack of energy;

- low self-esteem;

- difficulty concentrating and making decisions;

- feeling of hopelessness.

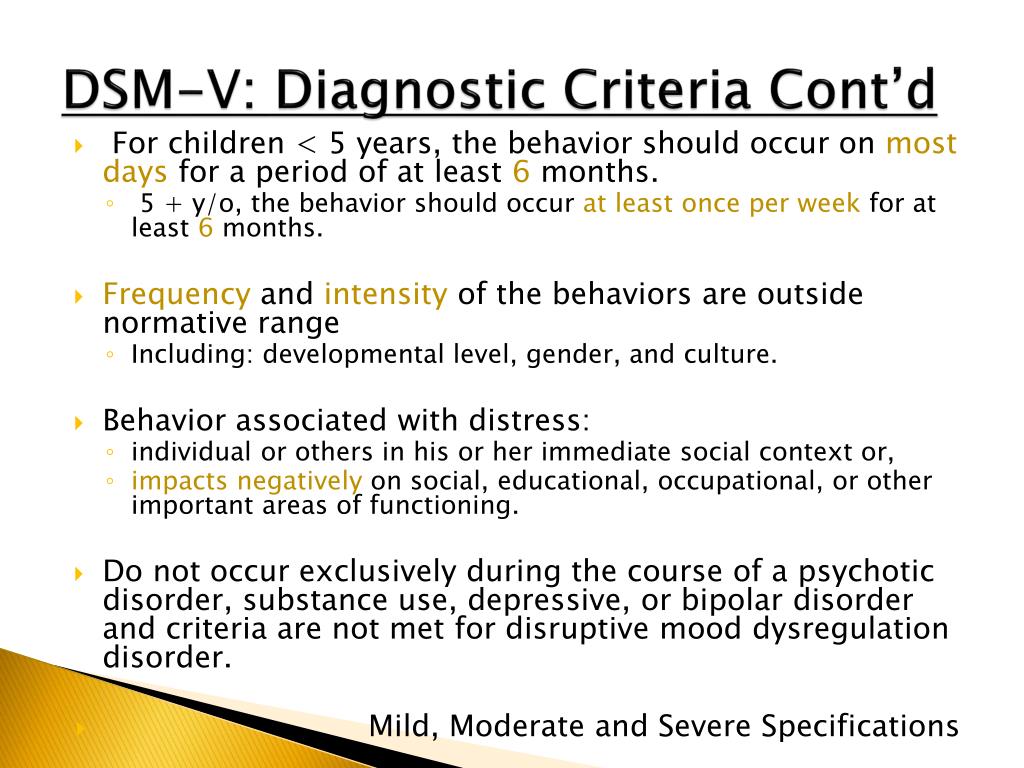

If this condition persists for more than two years (more than a year in a child), this is a serious reason to consult a doctor: a therapist or psychotherapist.

The doctor will conduct an examination, ask about the state of health, lifestyle, chronic diseases. Perhaps he will offer to take tests. This is necessary to exclude other problems that may manifest themselves as symptoms of a depressive disorder. For example, lack of energy and weight changes are often associated with hypothyroidism, an underproduction of thyroid hormones. In this case, it is necessary to correct this violation so that the symptoms go away by themselves.

Perhaps he will offer to take tests. This is necessary to exclude other problems that may manifest themselves as symptoms of a depressive disorder. For example, lack of energy and weight changes are often associated with hypothyroidism, an underproduction of thyroid hormones. In this case, it is necessary to correct this violation so that the symptoms go away by themselves.

Persistent depressive disorder is diagnosed when chronically depressed mood is not explained by physiological causes.

How dysthymia is treated

With psychotherapy and antidepressants. The latter have a lot of side effects, so doctors start treating children and adolescents, as well as people whose dysthymia is not too pronounced, without using these drugs.

Antidepressants are prescribed when the dysthymia is so severe that it can develop into a real "major" depression, or when the symptoms of the disorder are seriously making a person's life miserable.

It is important to remember that antidepressants are not a magic pill. There are many types of them, and it is far from always possible to find a really effective medicine the first time. And in order for the drugs to begin to work, you need to take them for at least a few weeks. In addition, you cannot simply stop taking antidepressants: when treatment is stopped abruptly or a few doses are missed, symptoms usually return with renewed vigor.

There are many types of them, and it is far from always possible to find a really effective medicine the first time. And in order for the drugs to begin to work, you need to take them for at least a few weeks. In addition, you cannot simply stop taking antidepressants: when treatment is stopped abruptly or a few doses are missed, symptoms usually return with renewed vigor.

How to relieve the condition at home

Experts from the American research center Mayo Clinic recommend supplementing the treatment prescribed by a doctor with self-care.

- Remember your purpose. One day you will again become a happy and active person. Necessarily.

- Make your life more manageable. Plan your day, make to-do lists, use sticky notes as reminders, try to stick to a predetermined schedule. This will give you back a sense of control over what is happening.

- Keep a diary. In it you will be able to express your emotions and thus reduce the level of stress.

- Read books on psychology. They will help you understand yourself and what is happening. If you don't know where to start, ask your doctor for advice.

- Do not withdraw into yourself. It is important to continue to meet with loved ones and do work in order to feel needed.

- Learn to control stress. For example, learn deep breathing or meditation techniques and use them in difficult moments.

- Do not make any decisions about your future during times of anguish. This approach will protect against the temptation to quit therapy if it suddenly seems that it does not work.

How to avoid dysthymia

Unfortunately, there are no reliable methods of prevention: scientists have not yet fully understood the nature of dysthymia. The disorder may develop due to genetics, inborn personality traits, or due to traumatic events - these factors are not affected.

However, there are ways to reduce the risk of developing dysthymia.